Abstract

Functional movement and stability of the limb depends on an organized and fully integrated musculoskeletal system composed of skeleton, muscle, and tendon. Much of our current understanding of musculoskeletal development is based on studies that focused on the development and differentiation of individual tissues. Likewise, research on patterning events have been largely limited to the primary skeletal elements and the mechanisms that regulate soft tissue patterning, the development of the connections between tissues, and their interdependent development are only beginning to be elucidated. This review will therefore highlight recent exciting discoveries in this field, with an emphasis on tendon and muscle patterning and their integrated development with the skeleton and skeletal attachments.

Keywords: Tendon patterning, Muscle patterning, Musculoskeletal development

Introduction

The musculoskeletal system is an exquisite assembly of different tissues whose integration during development is critical for proper function. The basic tissues comprising the system include the skeleton (which provides structure), muscles (which provide contractile forces that mobilize the skeleton), and tendons (which connect muscles to the skeleton and transmit those forces) (Standring, 2016). While significant attention has been paid to the differentiation of individual tissues (in particular, cartilage, bone, and muscles), how these tissues become integrated to form a functional unit remains poorly understood. The tetrapod limb is a useful model for studying these questions since it is easily manipulated and develops in a stereotypic fashion that is conserved across species (Gilbert, 2010). Pioneering experiments using classic embryological techniques by John Saunders and others showed that the limb forms in proximal to distal progression, to generate the three main segments of the limb: the stylopod (humerus/femur), the zeugopod (radius and ulna/tibia and fibula), and the autopod (hand/foot) (Gilbert, 2010; Maccabe et al., 1973; Saunders, 1998; Towers and Tickle, 2009). Each of these limb segments contain tendon and muscle elements that are oriented and attached precisely to enable the full range of movements specific to that segment.

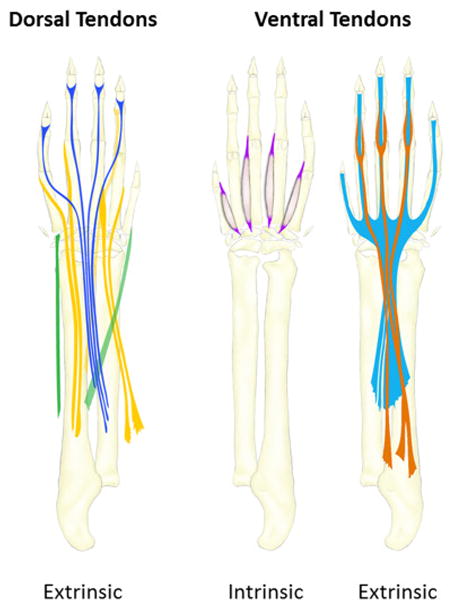

Historically, much of the interest in musculoskeletal patterning has focused on the patterning of the skeletal elements, partly because these tissues are the easiest to study and visualize. For example, the stylopod and zeugopod contain a mere one and two long bones, respectively, that are easily distinguished. In contrast, the number of individual tendons and muscles within a single segment in the limb are far higher in number (10+ muscle groups in the zeugopod alone), and a specific muscle or tendon group may include several individual units (Popesko et al., 2003; Watson et al., 2009). The anatomy of the soft tissues in the limb is also quite complex; muscles and their attachments are oriented according to the direction of the force they must provide and functionality of these units depends on proper orientation as well as the proper placement of their attachments since motion can only be generated across joints. Although many tendons are simple short or long linear structures that extend from muscle to skeleton, tendons can also be anatomically complex, fusing into a single tendon and/or splitting into multiple tendon pieces along their trajectory (Figure 1)(Watson et al., 2009). The bones, muscles, and tendons that reside within the autopod are especially numerous and complex, which allows for fine control and precise movements in the hand.

Figure 1. Anatomy of dorsal and ventral autopod tendons of the limb.

Intrinsic tendons are completely localized in the autopod along with their muscles while extrinsic tendons originate from muscles in the zeugopod.

In the last 15 years, the study of soft tissue patterning has been immensely aided by the identification of new markers as well as the generation of new genetic and imaging tools to visualize these complex tissues. Fluorescent reporters and inducible Cre lines targeting specific cell populations such as tenocytes or muscle connective tissue facilitated studies that revealed their activities during musculoskeletal development (Mathew et al., 2011; Pryce et al., 2007; Sugimoto et al., 2013b). Imaging techniques such as Optical Projection Tomography, High Resolution Episcopic Microscopy, or Contrast Enhanced MicroCT, capture the complex anatomy of these soft tissues in three dimensions to allow for detailed analysis of limbs across the stages of development (Charles et al., 2016; Sharpe et al., 2002; Weninger and Mohun, 2002). In addition to advances in imaging, the application of computational techniques allow for digital segmentation and interactive analyses of individual tissues within the limb (Wan et al., 2012). For simple phenotyping however, basic atlases using standard two-dimensional tissue sections have also been extremely useful and provide accessible guides for reproducibly identifying specific anatomic groups based on their relative positions in the limb (Watson et al., 2009). Since tissue sections can be generated by most labs inexpensively, this type of atlas can be useful for rapidly screening mutants for soft tissue patterning phenotypes. Collectively, these resources now allow identification of defects in patterning that may affect specific anatomical groups and offer insight into the development of these structures.

Since there are several excellent reviews on differentiation of the individual musculoskeletal tissues, the purpose of the current review is to provide an updated overview of limb tendon, muscle, and attachment site patterning and highlight recent exciting advances in this field. The discussion of muscle will be mostly limited to the role of the muscle connective tissue in patterning and the relationship between muscle and its adjacent tissues; the large body of work on muscle progenitor migration, differentiation, myofiber specification, will not be discussed. However, information on topics related to individual tissue differentiation can be found in several other reviews (Braun and Gautel, 2011; Buckingham et al., 2003; Gaut and Duprez, 2016; Huang et al., 2015a; Murphy and Kardon, 2011; Schweitzer et al., 2010; Zelzer et al., 2014).

Overview of the key stages of musculoskeletal tissue patterning in the limb

To understand how the musculoskeletal system becomes integrated, it is helpful to consider the development of each tissue in the context of the others and distinguish the developmental events that are tissue autonomous versus events that are nonautonomous. A significant body of work has shown that the primary structures of the limb skeleton (ie. the long bones) can be formed independently of muscle and vice versa (Hasson et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010; Swinehart et al., 2013). However, recent findings now indicate that the secondary skeletal structures (ie. the bone eminences) depend on cues from tendon and muscle; indeed the patterning of individual muscles is tightly coordinated with their attachment sites (Blitz et al., 2013; Blitz et al., 2009; Colasanto et al., 2016). Similarly, while some features of tendon development are autonomous, key stages rely on signals emanating from muscle and cartilage, consistent with the functional role of tendon in connecting muscle to skeleton (Havis et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2015b). To establish the key stages of skeletal, muscle, and tendon development in the limb, a brief overview is provided in this section, encompassing the general stages of induction, differentiation, and patterning for each tissue. Although much of the early musculoskeletal research was carried out in chick, in recent years, the mouse has emerged as the primary model to study musculoskeletal patterning due to the ability to perform genetic perturbations in mice. Therefore, to maintain consistency in staging developmental events throughout, this review will focus mostly on the mouse system.

Skeletal Development

The mouse forelimb bud initiates from the lateral plate mesoderm at E9.0 (with the hindlimb bud initiating about half a day later). Identification of limb segments was initially based on the skeletal segments, and this remains a simple and effective method for distinguishing the different segments of the limb (Martin, 1990; Wanek et al., 1989). The limb segments are specified rapidly, with distinct stylopod (E10.0), zeugopod (E11.0), and autopod (E11.5) segments observed within days of limb bud initiation. Although the metacarpal rays of the autopod are already distinct at E12.5, more distal structures of the autopod components (such as the digits) are not induced until later stages and full patterning of all skeletal structures is not complete until E16.5 (Martin, 1990; Wanek et al., 1989). The cartilage progenitors of the limb skeleton are progressively induced in each of the forming segments from the limb mesenchyme, in parallel with limb outgrowth. Sox9, a transcription factor required for cartilage formation and an early marker of prechondrogenic progenitors, is detected in the limb bud as early as E10.0 (Akiyama et al., 2002; Akiyama et al., 2005; Bi et al., 1999; Bi et al., 2001). Long bone formation is initiated by condensation of mesenchymal cells that subsequently undergo chondrogenesis and deposit cartilage matrix molecules, including aggrecan and type II collagen. Proliferation, longitudinal growth of the cartilage structure, and eventual replacement of cartilage by bone is fueled by the establishment of an ordered growth plate that regulates the chondrocyte growth and maturation from proliferative to hypertrophic stages (Kronenberg, 2003). Osteogenesis begins with the expression of the osteoblast transcription factor Runx2 at E13.5 followed by the first appearance of ossified tissue at E14.5 in the proximal segments (Akiyama et al., 2005). The bone eminences that decorate the long bones (for example, the tuberosity or the trochanter) are induced a day or so after induction of the long bones and are derived from a separate progenitor population. Development of the secondary skeletal structures will be discussed in detail in a later section.

Muscle Development

Limb muscles on the other hand originate from Pax3-expressing progenitors that delaminate and migrate from the dermomyotome of adjacent somites into the forming limb bud; migration is largely complete by E10.5 in the forelimb (Murphy and Kardon, 2011). Upon entering the limb, the progenitors move around the chondrogenic centers, to occupy dorsal and ventral positions within the limb. Progenitors are initially bipotent and can form either muscle or endothelium (Kardon et al., 2002). Once in the limb, progenitors that adopt the myogenic fate will proliferate, fuse and differentiate to form muscle masses, followed by cleavage into distinct muscles. Muscle differentiation requires the expression of four key transcription factors (collectively termed the myogenic regulatory factors or MRF). The MRFs consist of Myf5, MyoD, Mrf4, and Myogenin (Buckingham et al., 2003). At E10.5 in the limb, Myf5 and MyoD are the first to be expressed by muscle progenitors undergoing differentiation, followed by Myogenin at E11.5 and finally Mrf4 at E13.5 (Murphy and Kardon, 2011). The basic muscle pattern is established as early as E12.5, although distinct, individuated muscles are not observed until E13.5. Full patterning of muscle throughout the limb is complete by the end of the embryonic phase of myogenesis at E14.5. Muscle development continues past E14.5 to birth (a stage termed fetal myogenesis) and this phase is characterized by continued growth and maturation of myofibers (Mathew et al., 2011).

Tendon Development

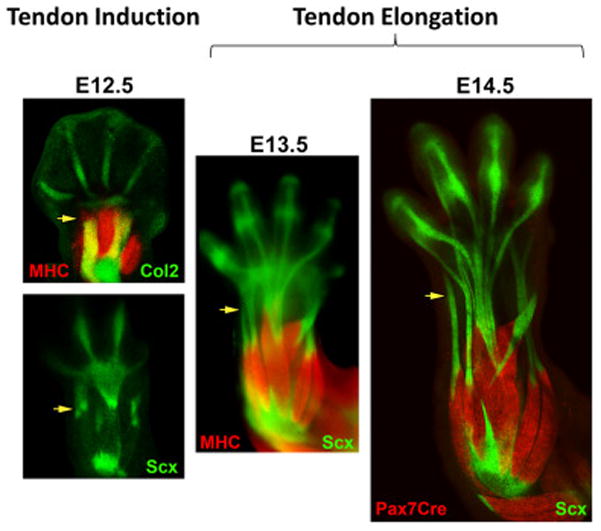

Like cartilage, tendon progenitors also originate from the limb mesenchyme and tendon induction occurs progressively in a proximal to distal direction (Schweitzer et al., 2001). The transcription factor Scx is the earliest known marker of tendon progenitors and Scx expression is first detected in limb buds at E10.5 (Huang et al., 2015b; Schweitzer et al., 2001). The initial induction of tendon progenitors occurs subectodermally in dorsal and ventral domains separate from the more centrally located cartilage condensations. Although Scx and Pax3 muscle progenitors occupy similar regions at E10.5 and E11.5 (Schweitzer et al., 2001), these progenitor populations are completely distinct (Bonnin et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2013). Despite early detection of Scx progenitors, it is still not entirely clear whether the progenitor population induced at E10.5 are the source of cells for later tendons or whether these cells adopt connective tissue fates other than tendon (for example fascia or muscle connective tissues). In the limb, a distinctive tendon pattern is not apparent until E12.5 when loosely organized tendon progenitors align between the differentiating cartilage and muscle tissues (Murchison et al., 2007). At E13.5, tendon progenitors condense to form tendon structures, concurrent with expression of tendon differentiation markers including Tnmd, Mkx, Egr1, Egr2, and Col1a1 (Ito et al., 2010; Lejard et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2010; Murchison et al., 2007; Shukunami et al., 2001; Shukunami et al., 2006). While tendon patterning is largely complete by E14.5, subsequent patterning events such as the splitting of certain tendon groups is not complete until E16.5 (Huang et al., 2015b; Watson et al., 2009).

Generally, the stages of cartilage and muscle differentiation precede that of tendon, beginning at E10.5/11.5 (for cartilage and muscle) vs E13.5 (for tendon). While the basic pattern for all tissues is established by E12.5, the stages between E12.5–14.5 continue to be critical for tendon patterning, which is not complete until E14.5. These stages are also important for muscle and skeletal patterning events such as muscle cleavage, the continued development of the autopod skeleton, and the induction and differentiation of secondary skeletal structures (Hasson, 2011; Zelzer et al., 2014). One exception to general musculoskeletal development is the superficial flexor muscles and tendons, which follow a unique developmental program. Since this review will focus on general limb tendon and muscle patterning, the superficial flexors will not be discussed, but a detailed description can be found elsewhere (Huang et al., 2013).

Conceptual model of tendon induction and elongation: modularity and the role of muscle

Early studies of tendon formation using the chick limb concluded that limb tendons and muscles form autonomously (Brand et al., 1985; Chevallier et al., 1977; Shellswell and Wolpert, 1977). This was later contradicted by a key study, also in chick, which showed that while initial aspects of tendon progenitor induction can be uncoupled from muscle, the presence of muscle is required for later differentiation and maintenance of tendon (Kardon, 1998). Interestingly, the requirement for muscle varies depending on the position within the limb (distal autopod vs proximal zeugopod/stylopod segments). Although the induction of limb tendon progenitors does not depend on muscle, there is an early loss of tendons when muscles are absent, but only in proximal segments (Kardon, 1998). Remarkably, tendon differentiation in the autopod is not disturbed, although the distal tendons later degenerate in the absence of muscle. This work was the first to show that the autopod and zeugopod/stylopod tendons are separately regulated. Subsequent studies extended some of these findings to mouse and delineated muscle-independent and muscle-dependent phases regulating the progenitor (E12.5) and differentiation (E13.5) phases of limb tendon development, respectively (Bonnin et al., 2005; Havis et al., 2016).

These findings were both intriguing yet puzzling, especially when one considers the unique anatomy of several tendons that occupy the autopod/zeugopod segments. While the autopod and zeugopod both contain ‘intrinsic’ tendons and muscles that primarily reside within their segments, there are also several long tendons that originate from ‘extrinsic’ muscles residing in the zeugopod, cross the wrist/ankle joint and insert into various digit elements within the autopod (Figure 1). These autopod tendons are continuous structures yet the development of their zeugopod and autopod components seemed to be independent of each other. How then is the continuous structure formed? Are the tendons formed by pathfinding, where tendons grow from one attachment site to the other? And why would these components be regulated independently?

To address these questions, a new conceptual model for understanding the modular basis for autopod and zeugopod tendon development was recently proposed based on analysis of wild type limbs and a series of genetic experiments (Huang et al., 2015b). Analysis of E12.5 limbs showed that the zeugopod skeleton is surprisingly very short with muscles spanning the full length of the skeleton. The musculoskeletal system is already integrated at this stage as muscles are connected on either end to short tendon segments located at the elbow and wrist. These short range wrist tendon progenitors themselves connect to either the skeleton or to their forming autopod tendon components. Between E12.5 and E14.5, there is rapid elongation of the zeugopod tendon components in parallel with rapid longitudinal growth of the zeugopod skeleton. Thus, the model proposes a two stage process for zeugopod tendon development: (1) induction of short range tendon progenitors attached to muscle and either the skeleton or its autopod tendon component followed by (2) elongation of tendon progenitors to form a differentiated linear tendon (Figure 2) (Huang et al., 2015b). For the autopod tendons, the short range tendon anlagen at the wrist therefore acts to integrate the forming autopod and zeugopod tendon components of the limb at E12.5.

Figure 2. Conceptual model for tendon modularity and development in the limb.

Wrist tendon progenitors are induced at E12.5 integrating muscle to the skeleton or autopod tendon components. Induction is followed by elongation of the wrist tendon element in parallel with skeletal growth (E13.5–14.5).

This conceptual model provides a helpful framework to understand the role of muscle and the basis of tendon modularity. In the complete absence of muscle progenitors, the pattern of tendon progenitors in the autopod and zeugopod is normal at E12.5, consistent with previous studies which showed normal tendon induction in the absence of muscle. However, zeugopod tendon progenitors subsequently disappear by E13.5 while the autopod components of those tendons condense and differentiate to form distinct tendon structures (although much reduced in size) (Huang et al., 2015b). Unlike what was previously shown for chick, these autopod tendons do not degenerate in the mouse, but persist through development. In the Hox11 mutant, zeugopod muscles and tendons are dramatically mispatterned, with loss of several muscles. Although some tendons are also lost, each mutant muscle is still associated with a tendon. Consistent with the model, induction of tendon progenitors is normal in the mutant and loss of some tendons is observed after elongation at E14.5 (Huang et al., 2015b; Swinehart et al., 2013). Thus, the ability to form the long tendons in the Hox11 mutant zeugopod is successful only for the tendons that had attached to muscle. Analysis of paralyzed embryos that lack coordinated muscle contraction revealed mostly normal tendons in the zeugopod and autopod, although tendons are slightly thinner and several tendons that normally separate remain fused at E16.5 (Huang et al., 2015b). Therefore, induction of the wrist tendon progenitors is independent of muscle, but subsequent elongation and differentiation of zeugopod tendon components depends on the attachment to muscle, consistent with previous chick results. Although the requirement for muscle is independent of its contractile ability, splitting of certain tendons and lateral growth of all tendons do require active muscle forces.

The role of cartilage in limb tendon development

The studies carried out to date suggest that autopod-specific signals regulate tendon development in that segment, but the nature of those signals is unknown. Signaling molecules such as Wnt, BMP, and TGFβ may regulate domains of Scx expression, however it is still not clear how tendons are formed or patterned in the autopod (Pryce et al., 2009; Schweitzer et al., 2001; Yamamoto-Shiraishi and Kuroiwa, 2013). While removal of the ectoderm at early stages results in loss of tendon progenitor induction, experiments in chick also suggested that cartilage may play a role in tendon induction (Ganan et al., 1993; Schweitzer et al., 2001; Yamamoto-Shiraishi and Kuroiwa, 2013). This was supported by studies in axial tendon development, which showed that tendon and cartilage may be derived from a common pool of bipotent progenitors whose differentiation is interdependent, since inhibition of cartilage differentiation drives expansion of Scx-expressing progenitors (Brent et al., 2003; Brent et al., 2005). Consistent with these studies, deletion of Smad4 in limb mesenchyme results in broadened expression of Scx expression by E11.5, in parallel with progressive loss of Sox9 expression (Benazet et al., 2012). Broad Scx expression is maintained through the limb at E12.5, however Scx progenitors fail to organize or align into any recognizable tendon pattern and distinct, differentiated tendons are never formed. Chondrogenic progenitors also do not differentiate into cartilage and autopod development is arrested early. Interestingly, the expansion of tendon progenitors is not due to loss of Sox9 function or loss of cartilage as conditional deletion of Sox9 in limb mesenchyme does not result in a similar expansion of tendon progenitors (Sox9 mutants are ‘skeletal-less’ in that pre-chondrogenic cartilage progenitors do not condense or differentiate) (Huang et al., 2015b). Instead, the pattern of Scx induction appears completely normal up to E12.5. At E12.5, autopod tendon progenitors are induced in wild type limbs along the metacarpal rays, but are missing in the conditional Sox9 mutant. In contrast to Smad4 mutants, Scx expression is never induced in Sox9 mutant autopods. The expansion of Scx expression in Smad4 mutants is therefore likely due to loss of BMP signaling (which was shown to inhibit Scx expression) (Benazet et al., 2012; Schweitzer et al., 2001). However, in the absence of additional activating signals, progenitors fail to adopt a tendon-specific cell fate. More recently, lineage tracing experiments showed that while there are bipotent tendo-chondro progenitors in the limb, these cells are specific to the tendon-bone insertion sites and the main bodies of tendons are not necessarily derived from these cells (Blitz et al., 2013; Sugimoto et al., 2013a).

Despite the severe phenotype in the autopod, Scx expression in the proximal limb segments of Sox9 ‘skeletal-less’ mutants is not affected and distinct tendons and muscles can be identified at E13.5 in the zeugopod, demonstrating again the modularity of distal and proximal tendon development (Huang et al., 2015b). Surprisingly, despite the absence of skeleton, tendon elongation in the zeugopod is not impaired, indicating that tendons can still anchor to some unknown structure. Additional experiments in other mutants with disrupted autopod cartilage development (such as arrest in autopod development, loss of specific digits, or added digits) confirmed that loss of tendon induction is associated with loss of autopod cartilage. In addition, loss (or addition) of specific digits results in concurrent loss (or addition) of tendons only for those digits (Huang et al., 2015b). Thus, autopod cartilage and tendon development are tightly associated. The effect of cartilage in tendon induction is independent of cartilage differentiation however, since Sox5−/−;Sox6−/− double mutants in which pre-chondrogenic condensations are formed but fail to differentiate have mostly normal tendons throughout all limb segments, contrary to what was observed for axial tendons in chick (Brent et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2015b).

Although cartilage is necessary for autopod tendon induction (stages prior to E14.5), the cues that regulate subsequent tendon patterning and growth may not depend on skeleton. This was indicated by an experiment which showed that loss of Lmx1b (a key regulator of dorsal patterning in the limb) in Sox9 cartilage progenitors results in full mirroring of the digit skeleton while tendons remain unchanged (Li et al., 2010). In contrast, early Lmx1b deletion in all limb mesenchyme via Prx1Cre imparts a ventral identity to all mesenchyme-derived dorsal tissues, including tendon. While this and other studies strongly suggest that skeletal development is uncoupled from soft tissue development, exciting work in recent years identified a specific component of the skeleton whose development depends on molecular and mechanical signals from the soft tissues. The following section will therefore address development and patterning of bone eminences and the tendon-bone attachment site.

Development and patterning of secondary structures of the skeleton and the tendon-bone insertion

Function of the musculoskeletal system depends on the correct development and positioning of specialized tissue attachments between muscle-tendon and tendon-skeleton. To date, there is still very little known about how the muscle-tendon attachment (myotendinous junction, MTJ) is formed or how these tissues find each other in the limb, especially since limb muscles do not induce tendon progenitors (Charvet et al., 2012). Although there has been some progress defining the role of the extracellular matrix in general MTJ development, much of this work was carried out in tissues other than limb (Goody et al., 2015; Kraft-Sheleg et al., 2016). This section will therefore focus on the development of the tendon-bone insertion with emphasis on recent data that have dramatically improved our understanding of this tissue.

Bone eminences

The direct point of connection between tendon and skeleton is called the enthesis, and this specialized tissue is composed of a transitional tissue gradient composed of tendon, fibrocartilage, mineralized cartilage, and bone. From a mechanical perspective, this gradient acts to dissipate local stresses at the tendon-bone interface to maintain integrity and stability of the attachment during movement (Genin and Birman, 2009; Genin et al., 2009; Liu et al.; Liu et al., 2012). Positioning of entheses is typically found at bone eminences, which are projections that protrude from the surfaces of long bones (Standring, 2016). These secondary structures of the skeleton are named according to their shapes and position on the bone. It was long assumed that these structures likely grow out from the main body of the skeleton, but recent studies now suggest this is not the case. Using carefully timed inducible labeling of Sox9- and Col2-expressing cells (targeting pre-chondrogenic and chondrogenic cells), these experiments showed that the cells forming the secondary structures are not derived from the main skeletal structures (Blitz et al., 2013). Instead, these cells represent a unique pool of progenitors that are induced independently. While the main skeletal structures arise from a Sox9-only population, the secondary structures are derived from bipotent Scx+/Sox9+ progenitor cells that are induced at E11.5/E12.5 by TGFβ signaling (Blitz et al., 2013; Sugimoto et al., 2013a). Interestingly, loss of TGFβ signaling also leads to total loss of tendon-specific (Scx-only) progenitors at E12.5, but does not affect Scx expression at E10.5 and E11.5, further suggesting that the early Scx+ progenitors at E10.5–E11.5 may be distinct from tendon progenitors (Pryce et al., 2009).

Like the main skeletal structures, bone eminences undergo endochondral ossification (Blitz et al., 2009). During eminence differentiation, progenitors are allocated to form either cartilage or tendon, resulting in downregulation of one transcription factor and maintenance of the other (Scx for tendon and Sox9 for cartilage). Targeted deletion of Sox9 in Scx-expressing eminence progenitor cells results in missing secondary structures as early as E13.5, however, tendons are still able to form and the tendon pattern appears largely normal (Blitz et al., 2013). This surprising finding suggests that in the absence of eminences, tendons can still form rudimentary attachments. Loss of Scx function in limb mesenchyme also results in loss of eminences. In this context, Scx is not required for induction of eminence progenitors at E12.5, but is required for BMP4 expression which drives the differentiation of eminence progenitors toward cartilage (Blitz et al., 2013; Blitz et al., 2009). BMP signaling has also been shown to inhibit Scx expression, so its activation in the allocated cartilage cells may function in negative feedback to turn off Scx (Schweitzer et al., 2001). Not all eminences are lost in the absence of BMP4 however, suggesting that there may be some redundancy with other BMP ligands or a requirement for other signaling pathways (Zelzer et al., 2014). Subsequent maintenance and growth of the eminences requires muscle loading as loss of muscle or muscle contraction results in loss of the structure by E18.5 due to reduced chondrocyte proliferation (Blitz et al., 2009). However, initiation of eminence progenitors and cartilage differentiation are not affected in muscle mutants since eminence patterning is normal at E14.5 (Blitz et al., 2009). Thus, while the main skeletal structures can form independently of muscle, formation of the secondary structures depends on muscle.

Entheses

Unlike the bone eminence, the enthesis is present during embryonic stages but differentiation and maturation occurs postnatally. At birth, the transition zone of the enthesis is not yet formed and the tendon-bone attachment site consists of only tendon followed by a sharp transition to bone (Galatz et al., 2007; Thomopoulos et al.; Thomopoulos et al., 2007; Zelzer et al., 2014). Development of fibrocartilage initiates within the first two weeks after birth, followed by continued growth and mineralization by three weeks. Proper formation of the transitional tissue depends on muscle loading after birth. Experiments inducing muscle paralysis via injection of botulinum toxin showed that the initiation of enthesis fibrocartilage is normal (no phenotype at two weeks), however continued growth and maintenance of fibrocartilage and mineralization is severely reduced in paralyzed limbs (detectable by three weeks) (Thomopoulos et al., 2007). Recent studies showed that enthesis fibrocartilage cells are specified during embryonic stages, beginning at E14.5–15.5. The fibrocartilage transitional zone of the enthesis emerges from a specialized subpopulation of cells (likely derived from the Scx/Sox9 pool) that can be detected based on their hedgehog signaling activity (Gli1+) (Dyment et al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 2015). Gli1+ cells specified during embryonic stages ultimately give rise to the entire mature enthesis. Postnatal ablation of Gli1+ cells or loss of hedgehog signaling results in loss or disruption of mineralized fibrocartilage (Breidenbach et al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 2015). Other molecular regulators of enthesis development have yet to be identified, however a possible role for Scx in postnatal development was recently shown. As discussed earlier, deletion of Scx results in loss of bone eminences, but the basic ability of tendon to attach to skeleton is not impaired. At postnatal stages however, organization and mineralization of the enthesis is subsequently disrupted in Scx mutants (Killian and Thomopoulos, 2016). It is still not completely clear whether these defects are due directly to Scx function in enthesis cells, since tendons are also drastically impaired in Scx mutants and postnatal pups show limited mobility, which could therefore affect mechanical loading of the enthesis.

Despite significant progress in identifying the key events that regulate tendon-bone insertion development, the cues that regulate patterning and positioning of the attachments on the skeleton are still almost completely undiscovered. New insight into this process comes from a recent study, which identified a role for the T-box transcription factor Tbx3 in the patterning of two muscles in the forelimb, along with their skeletal attachment sites (Colasanto et al., 2016). Deletion of Tbx3 in limb mesenchyme by Prx1Cre results in loss of all three bone eminences. But more remarkably, the development of the muscles appears to be tightly coupled to development of their eminences, suggesting that the same signaling cues may regulate both the patterning of muscles and their attachment sites.

Transcription factor regulation of muscle patterning by muscle connective tissue

Skeletal muscle is composed of multinucleated myofibers formed by myogenic differentiation and fusion of myocytes. Surrounding the individual muscle fibers and ensheathing the entire muscle is type I collagen-rich connective tissue, which is formed by fibroblasts derived from the limb lateral plate mesoderm (Chevallier et al., 1977; Wachtler et al., 1981). A potential role for muscle connective tissue (MCT) in regulating muscle development was initially conceived based on early experiments using classical embryological experiments in chick. These studies showed that MCT patterning is independent of muscle, indicating that it could be the source of patterning information for myogenic cells (Chevallier and Kieny, 1982; Chevallier et al., 1977). An elegant experiment using retroviral labeling to follow the lineage of myogenic cells subsequently proved that migrating muscle progenitors are not innately programmed to any particular limb position, anatomical muscle, or myofiber type, but that local signals in the limb mesenchyme regulate these important fate decisions (Kardon et al., 2002). The study of MCT in muscle development was then greatly facilitated by the discovery of Tcf4 as a marker for MCT fibroblasts, leading to the generation of key genetic tools that allowed targeting and visualization of these important cells (Kardon et al., 2003; Mathew et al., 2011).

Tcf4

Tcf4 is a member of the Tcf/Lef family of transcription factors, which act downstream of the canonical Wnt-β-catenin signaling pathway (Hurlstone and Clevers, 2002). In the mouse limb, Tcf4 is expressed early in lateral plate mesoderm, at ~E9.5 (Colasanto et al., 2016). By E12.5, Tcf4+ MCT cells are closely associated with but distinct from Pax7+ and MyoD+ myogenic cells (Mathew et al., 2011). Tcf4 continues to label MCT cells surrounding myofibers throughout embryogenesis, birth, and adulthood. In addition to the MCT, the aponeurosis (the tendon tissue at the muscle origin) as well as bone eminences are also derived from Tcf4-lineage cells (Colasanto et al., 2016; Mathew et al., 2011). Although it is not yet clear whether Tcf4 labels the progenitors for all eminences or only a subset of progenitors, the expression of Tcf4 at these sites points to a potential cell population that may integrate muscle, tendon, and attachment patterning during limb development.

In addition to its utility as a marker of MCT, Tcf4 also has a functional role in MCT regulation of muscle patterning. Analysis of Tcf4 null mutants showed abnormal splitting or truncation of several limb muscles, as well as altered origin and insertion sites of muscles across joints (Mathew et al., 2011). This is consistent with work in chick showing that disrupted Tcf4 results in muscle truncation and missing muscles, but only when limb mesenchyme is targeted; disruption of Tcf4 expression in myogenic cells does not result in patterning defects (Kardon et al., 2003).

Limb segment specific transcription factors

Several other transcription factors have also been implicated in limb muscle patterning, including Shox2, Hox11, Tbx3, Tbx4, and Tbx5. Interestingly, these transcription factors were originally identified based on their roles in regulating limb segment or fore/hindlimb identity. For example Shox2 and Hox11 are required for skeletal development in the stylopod and zeugopod, respectively, while Tbx5 and Tbx4 are required for forelimb and hindlimb bud initiation, respectively (Ahn et al., 2002; Cobb et al., 2006; Minguillon et al., 2005; Wellik and Capecchi, 2003). It is only beginning to be appreciated however, that these transcription factors also drive soft tissue patterning. In the Shox2 mutant, the position of myogenic cells is disrupted as early as E11.5 in the forming stylopod (Vickerman et al., 2011). Misorientation of muscle fibers is detectable by E12.5 as mutant fiber alignment is shifted 90 degrees from normal. In addition to improper orientation, muscles are also missing at E13.5, suggesting there may be subsequent defects in muscle cleavage or loss of muscle masses. Similarly, in the Hox11 mutant, zeugopod muscles and tendons are dramatically mispatterned, with loss of several muscles and their tendons (Swinehart et al., 2013). As discussed previously, patterning defects emerge after the tendon induction/integration phase at E12.5 and are only apparent at E14.5.

Tbx transcription factors

Tbx5 and Tbx4 are T-box transcription factors that regulate fore- and hind-limb initiation, respectively. This section will focus on Tbx5 since the stages of limb development discussed so far in this review are based on the forelimb, however Tbx4 appears to play a similar role in the hindlimb. Inducible deletion of Tbx5 in limb mesenchyme (past the stage of limb bud initiation) revealed abnormal muscle patterning for all of the muscles in the limb, as well as abnormal attachments to skeleton (Hasson et al., 2010). Although the main skeletal structures are largely unaffected, the deltoid tuberosity is lost, suggesting that Tbx5 may also regulate development of the bone eminences (Hasson et al., 2007). Since bone eminences were not evaluated in detail, it is unclear whether other eminences are also perturbed in Tbx5 mutants, although mispatterning of numerous skeletal attachments suggests that it is very likely. The requirement for Tbx5 in soft tissue and tuberosity patterning is restricted to a narrow window of time; soft tissue phenotypes are observed only when tamoxifen is delivered at E9.5 and 10.5 while loss of the deltoid tuberosity is observed when tamoxifen is delivered at E8.5 and E9.5 (Hasson et al., 2007; Hasson et al., 2010).

Analysis of another T-box transcription factor, Tbx3, offered greater insight into the relationship between muscle and bone eminence patterning. While Tbx5 deletion disrupts patterning for all forelimb muscles, loss of Tbx3 is restricted to only two muscles (lateral triceps and brachialis) and three bone eminences (olecranon, deltoid tuberosity, and the greater tubercle), which considerably simplifies phenotypic analysis and interpretation (Colasanto et al., 2016). Similar to what was shown for Tbx5 and Tbx4, the timing of Tbx3 deletion is also very important. The loss of Tbx3 at E9.0 results in the total loss of the ulna bone, posterior digits and the thumb (even though these segments are not apparent until much later stages). Slightly later deletion of Tbx3 at E9.25 results in a largely normal skeletal phenotype but loss of all three bone eminences, while E9.5 deletion leads to loss of only two eminences. The timing of phenotypes is consistent with the fact that patterning and differentiation of the main skeletal structures precedes that of bone eminences. Remarkably, the muscle phenotype is highly correlated with development of their eminences. If both the origin and insertion eminences are lost, the muscles are completely missing. On the other hand, if only one is present, the muscle is present but truncated and not attached (Colasanto et al., 2016). Truncated muscles are not associated with a distinct tendon on the truncated side but end in a disorganized mass of connective tissue. In some cases, loss of an eminence results in shifting of the attachment to another location on the skeleton, consistent with the ability of tendon to still form an attachment in the absence of eminences. How this is regulated, and why some muscles fail to attach remain open questions.

Conclusion

This review has tried to highlight new findings in tendon, muscle, and skeletal attachment patterning of the limb, with emphasis on their integrated development and interdependency (Figure 3). As the field moves forward, it is clear that analysis and study of tissue patterning must be carried out with full appreciation of these considerations. More research will be required to address basic questions, a few of which include: what are the signals that guide integration of muscles to their tendon progenitors, how are tendons able to attach in the absence of eminences or cartilage, what are the signals that regulate anatomic muscle identity, how are muscles formed in the absence of tendons, how are tendons patterned in the autopod, and what is the relationship between cartilage and tendon patterning?

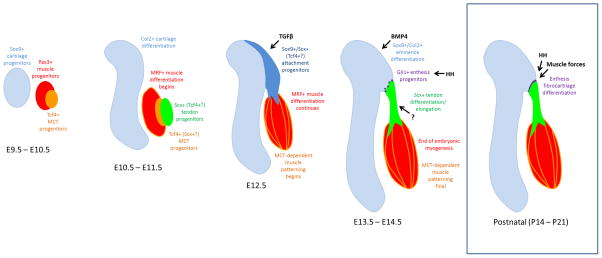

Figure 3. Coordinated development of musculoskeletal tissues.

The early stages of cartilage and muscle development are largely tissue autonomous (E9.5–E11.5). Integration begins at E12.5 with induction of attachment progenitors that mediate connection of muscle to the primary skeleton structure; cells of the attachment are then allocated to form the bone eminence and the tendon. While BMP4 is required for bone eminence differentiation, the molecular signals that regulate tendon differentiation and elongation are still unknown. Muscle differentiation is regulated by expression of MRFs in myogenic cells, but subsequent patterning depends on cells of the MCT. Enthesis progenitors are specified later in embryogenesis (and are likely derived from the initial attachment progenitor pool) and can be identified based on HH signaling. However, differentiation of the fibrocartilage enthesis occurs in postnatal stages, and depends on both HH signaling and active muscle forces. MRF: muscle regulatory factors; MCT: muscle connective tissue; HH: hedgehog.

In addition to these questions, one intriguing feature that has emerged from recent discoveries is the modular basis of musculoskeletal development. These include modularity of autopod and zeugopod tendon development, modular formation of bone eminences relative to the main skeletal structure, and the modular development of specific muscles and their attachments. This modularity, by decoupling development of different components of the musculoskeletal system, may have been important for enabling evolutionary changes to the system. Unlike the skeleton, the evolution of soft tissues is challenging to study due to the paucity of significant fossil records. However, comparative anatomy studies across species show a considerable degree of variation in the number of limb muscles and tendons and their pattern, suggesting that adaptability of musculoskeletal units may confer some functional benefits (Abdala et al., 2015; Diogo et al., 2009; Diogo et al., 2015). Clinical observations in humans also demonstrate a wide range in normal variation; for example, the palmaris longus muscle of the forelimb is missing in up to a quarter of the population and the fourth superficial flexor tendon in the digits is missing in over 10% of humans studied (Martinoli et al., 2010; Townley et al., 2010). While these small anomalies are rarely symptomatic, in the case of congenital diseases such as Ulnar-mammary syndrome or heart-hand syndrome, musculoskeletal impairments due to mispatterning are far more severe and provide insight into the molecular regulation of these tissues during development (Bamshad et al., 1997; Colasanto et al., 2016; Hasson et al., 2010; Newbury-Ecob et al., 1996). Future research will no doubt advance our understanding of tissue modularity in the context of patterning and identify additional molecules that regulate specific musculoskeletal units.

Highlights.

Limb musculoskeletal tissue development is interdependent.

Integration of the musculoskeletal system occurs at E12.5.

Modularity is a developmental feature for several musculoskeletal tissues.

Acknowledgments

Supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01AR069537) to AHH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdala V, Grizante MB, Diogo R, Molnar J, Kohlsdorf T. Musculoskeletal anatomical changes that accompany limb reduction in lizards. J Morphol. 2015;276:1290–1310. doi: 10.1002/jmor.20419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn DG, Kourakis MJ, Rohde LA, Silver LM, Ho RK. T-box gene tbx5 is essential for formation of the pectoral limb bud. Nature. 2002;417:754–758. doi: 10.1038/nature00814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, Chaboissier MC, Martin JF, Schedl A, de Crombrugghe B. The transcription factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2813–2828. doi: 10.1101/gad.1017802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, Kim JE, Nakashima K, Balmes G, Iwai N, Deng JM, Zhang Z, Martin JF, Behringer RR, Nakamura T, de Crombrugghe B. Osteo-chondroprogenitor cells are derived from Sox9 expressing precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14665–14670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504750102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamshad M, Lin RC, Law DJ, Watkins WC, Krakowiak PA, Moore ME, Franceschini P, Lala R, Holmes LB, Gebuhr TC, Bruneau BG, Schinzel A, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Jorde LB. Mutations in human TBX3 alter limb, apocrine and genital development in ulnar-mammary syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;16:311–315. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benazet JD, Pignatti E, Nugent A, Unal E, Laurent F, Zeller R. Smad4 is required to induce digit ray primordia and to initiate the aggregation and differentiation of chondrogenic progenitors in mouse limb buds. Development. 2012;139:4250–4260. doi: 10.1242/dev.084822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi W, Deng JM, Zhang Z, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B. Sox9 is required for cartilage formation. Nat Genet. 1999;22:85–89. doi: 10.1038/8792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi W, Huang W, Whitworth DJ, Deng JM, Zhang Z, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B. Haploinsufficiency of Sox9 results in defective cartilage primordia and premature skeletal mineralization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6698–6703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111092198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitz E, Sharir A, Akiyama H, Zelzer E. Tendon-bone attachment unit is formed modularly by a distinct pool of Scx- and Sox9-positive progenitors. Development. 2013;140:2680–2690. doi: 10.1242/dev.093906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitz E, Viukov S, Sharir A, Shwartz Y, Galloway J, Pryce B, Johnson R, Tabin C, Schweitzer R, Zelzer E. Bone ridge patterning during musculoskeletal assembly is mediated through SCX regulation of Bmp4 at the tendon-skeleton junction. Developmental cell. 2009;17:861–873. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnin MA, Laclef C, Blaise R, Eloy-Trinquet S, Relaix F, Maire P, Duprez D. Six1 is not involved in limb tendon development, but is expressed in limb connective tissue under Shh regulation. Mechanisms of development. 2005;122:573–585. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand B, Christ B, Jacob HJ. An experimental analysis of the developmental capacities of distal parts of avian leg buds. Am J Anat. 1985;173:321–340. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001730408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T, Gautel M. Transcriptional mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle differentiation, growth and homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nrm3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breidenbach AP, Aschbacher-Smith L, Lu Y, Dyment NA, Liu CF, Liu H, Wylie C, Rao M, Shearn JT, Rowe DW, Kadler KE, Jiang R, Butler DL. Ablating hedgehog signaling in tenocytes during development impairs biomechanics and matrix organization of the adult murine patellar tendon enthesis. J Orthop Res. 2015;33:1142–1151. doi: 10.1002/jor.22899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent A, Schweitzer R, Tabin C. A somitic compartment of tendon progenitors. Cell. 2003;113:235–248. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent AE, Braun T, Tabin CJ. Genetic analysis of interactions between the somitic muscle, cartilage and tendon cell lineages during mouse development. Development. 2005;132:515–528. doi: 10.1242/dev.01605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M, Bajard L, Chang T, Daubas P, Hadchouel J, Meilhac S, Montarras D, Rocancourt D, Relaix F. The formation of skeletal muscle: from somite to limb. J Anat. 2003;202:59–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles JP, Cappellari O, Spence AJ, Hutchinson JR, Wells DJ. Musculoskeletal Geometry, Muscle Architecture and Functional Specialisations of the Mouse Hindlimb. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charvet B, Ruggiero F, Le Guellec D. The development of the myotendinous junction. A review. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012;2:53–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier A, Kieny M. On the role of the connective tissue in the patterning of the chick limb musculature. Wilhelm Roux Arch. 1982;191:277–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00848416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier A, Kieny M, Mauger A. Limb-somite relationship: origin of the limb musculature. Journal of embryology and experimental morphology. 1977;41:245–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb J, Dierich A, Huss-Garcia Y, Duboule D. A mouse model for human short-stature syndromes identifies Shox2 as an upstream regulator of Runx2 during long-bone development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4511–4515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510544103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasanto MP, Eyal S, Mohassel P, Bamshad M, Bonnemann CG, Zelzer E, Moon AM, Kardon G. Development of a subset of forelimb muscles and their attachment sites requires the ulnar-mammary syndrome gene Tbx3. Disease models & mechanisms. 2016;9:1257–1269. doi: 10.1242/dmm.025874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diogo R, Abdala V, Aziz MA, Lonergan N, Wood BA. From fish to modern humans--comparative anatomy, homologies and evolution of the pectoral and forelimb musculature. J Anat. 2009;214:694–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diogo R, Ziermann JM, Linde-Medina M. Specialize or risk disappearance - empirical evidence of anisomerism based on comparative and developmental studies of gnathostome head and limb musculature. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2015;90:964–978. doi: 10.1111/brv.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyment NA, Breidenbach AP, Schwartz AG, Russell RP, Aschbacher-Smith L, Liu H, Hagiwara Y, Jiang R, Thomopoulos S, Butler DL, Rowe DW. Gdf5 progenitors give rise to fibrocartilage cells that mineralize via hedgehog signaling to form the zonal enthesis. Dev Biol. 2015;405:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galatz L, Rothermich S, VanderPloeg K, Petersen B, Sandell L, Thomopoulos S. Development of the supraspinatus tendon-to-bone insertion: localized expression of extracellular matrix and growth factor genes. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:1621–1628. doi: 10.1002/jor.20441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganan Y, Macias D, Garcia-Martinez V, Hurle JM. In vivo experimental induction of interdigital tissue chondrogenesis in the avian limb bud results in the formation of extradigits. Effects of local microinjection of staurosporine, zinc chloride and growth factors. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1993;383A:127–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaut L, Duprez D. Tendon development and diseases. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2016;5:5–23. doi: 10.1002/wdev.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genin GM, Birman V. Micromechanics and Structural Response of Functionally Graded, Particulate-Matrix, Fiber-Reinforced Composites. Int J Solids Struct. 2009;46:2136–2150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genin GM, Kent A, Birman V, Wopenka B, Pasteris JD, Marquez PJ, Thomopoulos S. Functional grading of mineral and collagen in the attachment of tendon to bone. Biophys J. 2009;97:976–985. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert SF. Developmental biology. 9. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, Mass: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goody MF, Sher RB, Henry CA. Hanging on for the ride: adhesion to the extracellular matrix mediates cellular responses in skeletal muscle morphogenesis and disease. Dev Biol. 2015;401:75–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson P. “Soft” tissue patterning: muscles and tendons of the limb take their form. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:1100–1107. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson P, Del Buono J, Logan MP. Tbx5 is dispensable for forelimb outgrowth. Development. 2007;134:85–92. doi: 10.1242/dev.02622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson P, DeLaurier A, Bennett M, Grigorieva E, Naiche LA, Papaioannou VE, Mohun TJ, Logan MP. Tbx4 and tbx5 acting in connective tissue are required for limb muscle and tendon patterning. Dev Cell. 2010;18:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havis E, Bonnin MA, de Lima JE, Charvet B, Milet C, Duprez D. TGFbeta and FGF promote tendon progenitor fate and act downstream of muscle contraction to regulate tendon differentiation during chick limb development. Development. 2016 doi: 10.1242/dev.136242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang A, Riordan T, Wang L, Eyal S, Zelzer E, Brigande J, Schweitzer R. Repositioning forelimb superficialis muscles: tendon attachment and muscle activity enable active relocation of functional myofibers. Developmental cell. 2013;26:544–551. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang AH, Lu HH, Schweitzer R. Molecular regulation of tendon cell fate during development. J Orthop Res. 2015a doi: 10.1002/jor.22834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang AH, Riordan TJ, Pryce B, Weibel JL, Watson SS, Long F, Lefebvre V, Harfe BD, Stadler HS, Akiyama H, Tufa SF, Keene DR, Schweitzer R. Musculoskeletal integration at the wrist underlies the modular development of limb tendons. Development. 2015b;142:2431–2441. doi: 10.1242/dev.122374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlstone A, Clevers H. T-cell factors: turn-ons and turn-offs. EMBO J. 2002;21:2303–2311. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.10.2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Toriuchi N, Yoshitaka T, Ueno-Kudoh H, Sato T, Yokoyama S, Nishida K, Akimoto T, Takahashi M, Miyaki S, Asahara H. The Mohawk homeobox gene is a critical regulator of tendon differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10538–10542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000525107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardon G. Muscle and tendon morphogenesis in the avian hind limb. Development. 1998;125:4019–4032. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardon G, Campbell JK, Tabin CJ. Local extrinsic signals determine muscle and endothelial cell fate and patterning in the vertebrate limb. Dev Cell. 2002;3:533–545. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardon G, Harfe BD, Tabin CJ. A Tcf4-positive mesodermal population provides a prepattern for vertebrate limb muscle patterning. Dev Cell. 2003;5:937–944. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killian ML, Thomopoulos S. Scleraxis is required for the development of a functional tendon enthesis. FASEB J. 2016;30:301–311. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-258236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft-Sheleg O, Zaffryar-Eilot S, Genin O, Yaseen W, Soueid-Baumgarten S, Kessler O, Smolkin T, Akiri G, Neufeld G, Cinnamon Y, Hasson P. Localized LoxL3-Dependent Fibronectin Oxidation Regulates Myofiber Stretch and Integrin-Mediated Adhesion. Dev Cell. 2016;36:550–561. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg HM. Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature. 2003;423:332–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejard V, Blais F, Guerquin MJ, Bonnet A, Bonnin MA, Havis E, Malbouyres M, Bidaud C, Maro G, Gilardi-Hebenstreit P, Rossert J, Ruggiero F, Duprez D. EGR1 and EGR2 involvement in vertebrate tendon differentiation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:5855–5867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.153106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Qiu Q, Watson SS, Schweitzer R, Johnson RL. Uncoupling skeletal and connective tissue patterning: conditional deletion in cartilage progenitors reveals cell-autonomous requirements for Lmx1b in dorsal-ventral limb patterning. Development. 2010;137:1181–1188. doi: 10.1242/dev.045237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Watson S, Lan Y, Keene D, Ovitt C, Liu H, Schweitzer R, Jiang R. The atypical homeodomain transcription factor Mohawk controls tendon morphogenesis. Molecular and cellular biology. 2010;30:4797–4807. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00207-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Birman V, Chen C, Thomopoulos S, Genin GM. Mechanisms of Bimaterial Attachment at the Interface of Tendon to Bone. J Eng Mater Technol. :133. doi: 10.1115/1.4002641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YX, Thomopoulos S, Birman V, Li JS, Genin GM. Bi-material attachment through a compliant interfacial system at the tendon-to-bone insertion site. Mech Mater. 2012:44. doi: 10.1016/j.mechmat.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccabe AB, Gasseling MT, Saunders JW., Jr Spatiotemporal distribution of mechanisms that control outgrowth and anteroposterior polarization of the limb bud in the chick embryo. Mech Ageing Dev. 1973;2:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(73)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P. Tissue patterning in the developing mouse limb. Int J Dev Biol. 1990;34:323–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinoli C, Perez MM, Padua L, Valle M, Capaccio E, Altafini L, Michaud J, Tagliafico A. Muscle variants of the upper and lower limb (with anatomical correlation) Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2010;14:106–121. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1253155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew SJ, Hansen JM, Merrell AJ, Murphy MM, Lawson JA, Hutcheson DA, Hansen MS, Angus-Hill M, Kardon G. Connective tissue fibroblasts and Tcf4 regulate myogenesis. Development. 2011;138:371–384. doi: 10.1242/dev.057463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minguillon C, Del Buono J, Logan MP. Tbx5 and Tbx4 are not sufficient to determine limb-specific morphologies but have common roles in initiating limb outgrowth. Dev Cell. 2005;8:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchison N, Price B, Conner D, Keene D, Olson E, Tabin C, Schweitzer R. Regulation of tendon differentiation by scleraxis distinguishes force-transmitting tendons from muscle-anchoring tendons. Development (Cambridge, England) 2007;134:2697–2708. doi: 10.1242/dev.001933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M, Kardon G. Origin of vertebrate limb muscle: the role of progenitor and myoblast populations. Current topics in developmental biology. 2011;96:1–32. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385940-2.00001-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbury-Ecob RA, Leanage R, Raeburn JA, Young ID. Holt-Oram syndrome: a clinical genetic study. J Med Genet. 1996;33:300–307. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.4.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popesko P, Rajtova V, Horak J. Color Atlas of Anatomy of Small Laboratory Animals: Rat and Mouse. Saunders Ltd; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pryce B, Brent A, Murchison N, Tabin C, Schweitzer R. Generation of transgenic tendon reporters, ScxGFP and ScxAP, using regulatory elements of the scleraxis gene. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2007;236:1677–1682. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryce B, Watson S, Murchison N, Staverosky J, Dünker N, Schweitzer R. Recruitment and maintenance of tendon progenitors by TGFbeta signaling are essential for tendon formation. Development (Cambridge, England) 2009;136:1351–1361. doi: 10.1242/dev.027342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JW., Jr The proximo-distal sequence of origin of the parts of the chick wing and the role of the ectoderm. 1948. J Exp Zool. 1998;282:628–668. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-010x(19981215)282:6<628::aid-jez2>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AG, Long F, Thomopoulos S. Enthesis fibrocartilage cells originate from a population of Hedgehog-responsive cells modulated by the loading environment. Development. 2015;142:196–206. doi: 10.1242/dev.112714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R, Chyung JH, Murtaugh LC, Brent AE, Rosen V, Olson EN, Lassar A, Tabin CJ. Analysis of the tendon cell fate using Scleraxis, a specific marker for tendons and ligaments. Development. 2001;128:3855–3866. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.19.3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R, Zelzer E, Volk T. Connecting muscles to tendons: tendons and musculoskeletal development in flies and vertebrates. Development (Cambridge, England) 2010;137:2807–2817. doi: 10.1242/dev.047498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe J, Ahlgren U, Perry P, Hill B, Ross A, Hecksher-Sorensen J, Baldock R, Davidson D. Optical projection tomography as a tool for 3D microscopy and gene expression studies. Science. 2002;296:541–545. doi: 10.1126/science.1068206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shellswell GB, Wolpert L. The pattern of muscle and tendon development in the chick wing. In: Ede DA, Hinchliffe JR, Balls M, editors. Vertebrate Limb and Somite Morphogenesis. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1977. pp. 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Shukunami C, Oshima Y, Hiraki Y. Molecular cloning of tenomodulin, a novel chondromodulin-I related gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:1323–1327. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukunami C, Takimoto A, Oro M, Hiraki Y. Scleraxis positively regulates the expression of tenomodulin, a differentiation marker of tenocytes. Dev Biol. 2006;298:234–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standring S. Gray’s anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice, Gray’s Anatomy. 41. 2016. p. 1. online resource. [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y, Takimoto A, Akiyama H, Kist R, Scherer G, Nakamura T, Hiraki Y, Shukunami C. Scx+/Sox9+ progenitors contribute to the establishment of the junction between cartilage and tendon/ligament. Development (Cambridge, England) 2013a;140:2280–2288. doi: 10.1242/dev.096354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y, Takimoto A, Hiraki Y, Shukunami C. Generation and characterization of ScxCre transgenic mice. Genesis (New York, NY: 2000) 2013b;51:275–283. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinehart IT, Schlientz AJ, Quintanilla CA, Mortlock DP, Wellik DM. Hox11 genes are required for regional patterning and integration of muscle, tendon and bone. Development. 2013;140:4574–4582. doi: 10.1242/dev.096693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomopoulos S, Genin GM, Galatz LM. The development and morphogenesis of the tendon-to-bone insertion - what development can teach us about healing. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 10:35–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomopoulos S, Kim HM, Rothermich SY, Biederstadt C, Das R, Galatz LM. Decreased muscle loading delays maturation of the tendon enthesis during postnatal development. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:1154–1163. doi: 10.1002/jor.20418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towers M, Tickle C. Generation of pattern and form in the developing limb. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:805–812. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072499mt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townley WA, Swan MC, Dunn RL. Congenital absence of flexor digitorum superficialis: implications for assessment of little finger lacerations. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2010;35:417–418. doi: 10.1177/1753193409358523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickerman L, Neufeld S, Cobb J. Shox2 function couples neural, muscular and skeletal development in the proximal forelimb. Dev Biol. 2011;350:323–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachtler F, Christ B, Jacob HJ. On the determination of mesodermal tissues in the avian embryonic wing bud. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1981;161:283–289. doi: 10.1007/BF00301826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y, Lewis AK, Colasanto M, van Langeveld M, Kardon G, Hansen C. A practical workflow for making anatomical atlases for biological research. IEEE Comput Graph Appl. 2012;32:70–80. doi: 10.1109/mcg.2012.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanek N, Muneoka K, Holler-Dinsmore G, Burton R, Bryant SV. A staging system for mouse limb development. J Exp Zool. 1989;249:41–49. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402490109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson S, Riordan T, Pryce B, Schweitzer R. Tendons and muscles of the mouse forelimb during embryonic development. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2009;238:693–700. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellik DM, Capecchi MR. Hox10 and Hox11 genes are required to globally pattern the mammalian skeleton. Science. 2003;301:363–367. doi: 10.1126/science.1085672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weninger WJ, Mohun T. Phenotyping transgenic embryos: a rapid 3-D screening method based on episcopic fluorescence image capturing. Nat Genet. 2002;30:59–65. doi: 10.1038/ng785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto-Shiraishi Y-i, Kuroiwa A. Wnt and BMP signaling cooperate with Hox in the control of Six2 expression in limb tendon precursor. Developmental biology. 2013;377:363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelzer E, Blitz E, Killian ML, Thomopoulos S. Tendon-to-bone attachment: from development to maturity. Birth defects research Part C, Embryo today: reviews. 2014;102:101–112. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]