Pain is multi-billion-dollar public health concern and a significant cause of disability—particularly amongst older adults. Older adults with chronic health conditions such as osteoarthritis, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, sickle cell disease, and cancer are most likely to have pain. Of particular concern are Black older adults, or Americans over the age of 65 who are the descendants of US slaves primarily from Africa, as they experience great disparities in pain management and secondary health declines. Though ample research has been completed over the past ten years that links chronic pain to psychological distress and reductions in overall physical health, adequate pain control remains problematic for Black older adults. This concern sheds light on the importance of nursing engagement and persistence in effective pain management for this population. As first line health providers, nurses are in a unique position to push forward national standards for culturally appropriate services for Black elders by ensuring that quality care is not only effective, equitable, understandable, and respectful, but also that this care is responsive to the diverse cultural health beliefs, practices, and health literacy levels of the patients they care for (USDHHS, 2016). The following article provides a framework for the culturally responsive treatment of pain in older Black adults.

Pain in the Black Older Adult

Up to 78% of Black older adults experience chronic pain (Bazargan, Yazdanshenas, Gordon, & Orum, 2016; Karter et al., 2015). Unfortunately, these elders are not as likely as White, non-Latino elders, to discuss pain concerns. This may be related to the noted difficulty minorities have in effectively communicating pain needs to clinicians in ways that are clearly understood and believed (Shavers, Bakos, & Sheppard, 2010). However, when pain is reported, Black elders are more likely to describe higher levels of pain, suffering, and depressive symptoms than White elders (Booker, Pasero, & Herr, 2015; Limaye & Katz, 2006; National Center for Health Statistics, 2006). Although systemic provider and patient pain management practices account for much of this disparity (Cintron & Morrison, 2006), some of the variation may be attributable to genetic differences between Blacks and Whites.

Black Americans have a biological predisposition for lower pain tolerances and thresholds which causes them to be more sensitive to pain (Cruz-Almeida et al., 2014; Riley et al., 2014). This means that not only is pain experienced at lower intensity levels, but also, the maximum tolerable pain level is lower. Although ethnic identity is associated with lower pain tolerance and threshold for Black American and Latino groups as compared to non-Latino Whites (Rahim-Williams et al., 2007), it has been widely documented that Black Americans are more likely to receive poorer quality of care with less access to services than White Americans (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010). Additionally, minority patients are more likely to receive lower doses of pain medications than White patients and experience longer wait times to receive those medications despite consistently higher pain scores (Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2011; Shavers et al., 2010). Clearly there is a disparity in the management of pain for Black Americans—and particularly for Black older adults. The provision of culturally responsive care can help to reduce this disparity. Before considering how to improve culturally responsive care in practice, it is important to have a good understanding of the core term culture.

What is Culture?

Culture is a term frequently used in healthcare, but often misunderstood. The word commonly brings forth images of people from distant lands, foods of exotic tastes, and social practices poorly understood. However, culture may be aptly summed as the learned patterns of behavior, beliefs, and values shared by individuals of particular social groups (Robinson, 2013). Famed anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski (1944) notes that culture influences what is most important to individuals and allows them to cope with the concrete, specific problems [such as changes in health] which will arise during the life course. It is widely recognized in the literature that cultural and ethnic affiliation directly impacts health experiences as well as the identification and selection of appropriate care (Brondolo, Gallo, & Myers, 2008; Griffith, Metzl, & Gunter, 2011; Jackson, Knight, & Rafferty, 2010; Karlsen & Nazroo, 2002). Nurses are best able to aid the patients they are charged to care for by appropriately considering the unique attributes of the population they are working with and understanding the ways in which culture may affect health choices and care expectations. When nurses practice culturally congruent care, they are lifting up the values, beliefs, and lifeways of individuals, groups, and communities by supporting diversity, encouraging cultural awareness, ensuring cultural sensitivity, and requiring cultural competence (Schim, Doorenbos, Benkert, & Miller, 2007).

For instance, Black Americans are a common cultural group in the United States who share a history of enslavement, acculturation (a modification of culture made by adapting to or borrowing traits from another culture), and racial oppression—which distinguishes this cultural group from others and influences their behavior, values, lifestyles, and creative expressions (Scott, 2005). According to the most recent census reports, Black Americans represent nearly 14% (42 million) of the US population and 8% (about 3.2 million) of all older adults (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). A history of racial inequalities in the delivery of healthcare services and significant disparities in health outcomes has led to substantial provider mistrust and a long history of unmet health needs, such as unrelieved chronic pain (Arnett, Thorpe, Bowie, and LaVeist, 2016; Cuevas, O’Brien, and Saha, 2016; Hammond, 2010; Moseley, Freed, Bullard, and Goold, 2007.).

Black American distrust of the medical system dates long before the Tuskegee syphilis experiments to slavery era times when medical experimentation, such as pain studies, smallpox vaccine development, and experimental surgeries (sans anesthesia), were tested on involuntary subjects (Palanker, 2008). Despite radical changes in science and healthcare, Black Americans remained excluded from mainstream health institutions for the first 65 years of the 20th century until the passage of the Medicare Act in 1965. This Act required hospitals to desegregate in order to receive federal funding. Although the Medicare Act caused almost immediate hospital integration, Black Americans receiving benefits under Medicare, Medicaid, or the Veterans Administration fund continued to receive poorer quality of care as compared to White Americans (Palanker, 2008).

Black adults aged 65 and older were born prior 1951 during times of severe racial tension and government mandated segregation. As a result, most Black elders have experienced racism and significant disparities in healthcare during their lifetime. This inferior care has led to poor health outcomes for many (Mays, Cochran, and Barnes, 2007). For instance, studies have found that older Black men who have experienced various types of social discrimination have higher bodily pain intensity levels (Burgess et al., 2009; Edwards, 2008) and increased blood pressure (David R. Williams, 2003; David R Williams & Neighbors, 2001) which can exacerbate other health conditions. Tripp-Reimer and Fox (1990) question if nurses should consider “whether the objectification of African-American culture has created greater limitations or greater access to patients” (p. 545). The historical treatment of Black Americans as objects insensitive to pain may explain some of the significant disparities in access to care and inferior pain assessment and treatment (Ezenwa & Fleming, 2012; Washington, 2006).

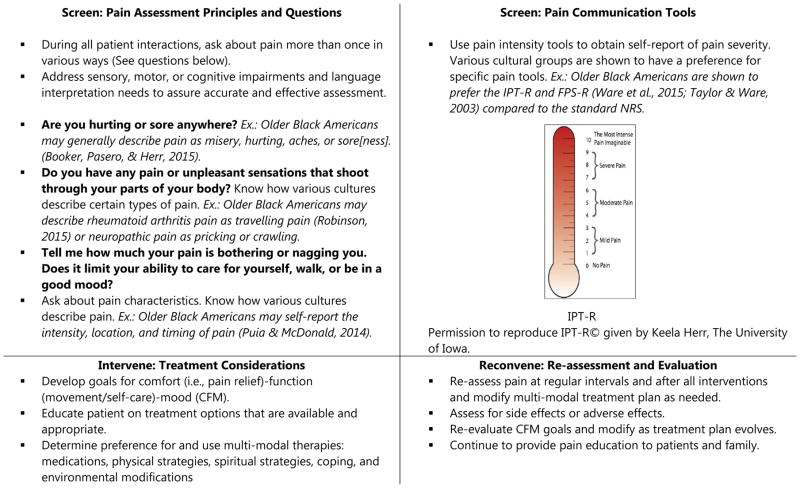

As evidenced, culture plays a significant role in the pain experience, particularly how to communicate pain, how much pain is tolerable, to whom to report pain, and the types of pain that should be reported. Cultural frameworks inform nurses and healthcare providers how to interact with older Black Americans and how to approach and explain pain management to these patients. The screen, intervene, and reconvene (SIR) model of pain management is one culturally-sensitive method to systematically assess, treat and manage, and re-assess/evaluate pain and goal-based pain management plans in older Black Americans. T his model is described in more detail elsewhere (S. S. Booker & Herr, 2015). Cultural responsiveness, or the recognition and integration of important social, ethnic, religious, and community values into care is an important means of addressing health disparities, such as disparities in the treatment and management of pain, and provision of effective, equitable, and respectful, quality care and services (USDHHS, 2016).

Cultural Responsiveness

Culturally responsive care emphasizes the capacity to respond to patient’s cultural beliefs and behavior systems by engaging patients in care, integrating cultural values into the plan of care, and adapting care to align with their culture (Carteret, 2011). In the context of pain, this entails understanding the reasons why older Black Americans may not have the ability, or willingness, to self-report pain and to positively counter this with respect, rapport building, dispelling misconceptions about pain reporting, and using culturally-sensitive communication and culturally-valid and preferred pain intensity tools (Booker, Pasero, & Herr, 2015). For example, as was noted previously, despite intense pain, older Black adults are hesitant to report or openly talk about pain. This may be related to the common cultural perception that talking about pain or “claiming pain” (acknowledging/declaring pain/putting it in the atmosphere) is spiritual taboo, in that talking about pain increases its intensity and power in one’s life (Staja Q. Booker, 2015).

For example, when one Black elder was asked why he chose not to talk about his pain he said, “I don’t talk about it a lot because I believe that words have a lot of power and you have to be careful what you speak out into existence.” (Robinson, 2015). This comment, and the related behavior, is consistent with research which shows that Black Americans minimize pain (Jones et al., 2008) and may serve as a cultural-specific coping phenomenon.

With this knowledge, the culturally responsive nurse will be proactive in asking older Black adults about their pain concerns in ways that convey respect and use relatable language. Nurses can establish rapport and engage in culturally-sensitive communication with all patients by considering the words they choose to use and how they address elders in relaying information. Special attention should be paid to tone of voice, body language, use of formal names—unless directed otherwise by the patient—and use of language that is reflective of the language the patient is using to describe a health concern. For example, rather than simply saying to a familiar patient, “Hi Mary, are you having any pain this morning?” or “Would you like a pain pill?” the culturally responsive nurse might begin with, “Hi Mrs. Smith, how are you feeling today?” as a means to engage with the patient and build rapport. Then, after allowing time for the patient to respond, the nurse might follow-up with “Are you feeling sore or uncomfortable anywhere (can substitute other words such as ‘aching’ or ‘paining’; Booker, Pasero, & Herr, 2015)?” Appropriate reassessment would then follow as necessary. If the Black older adult appears hesitant to report pain, it may be necessary to examine other dynamics of the patient-nurse relationship. For example, research indicates that Black and Hispanic long-term care residents have a greater sense of comfort reporting pain to female providers rather male providers (i.e., nurses, nursing assistants) (Dobbs, Baker, Carrion, Vongxaiburana, & Hyer, 2014). These types of actions, and other similar culturally adaptive interventions, support cultural congruency and promote cultural humility.

Cultural Congruency

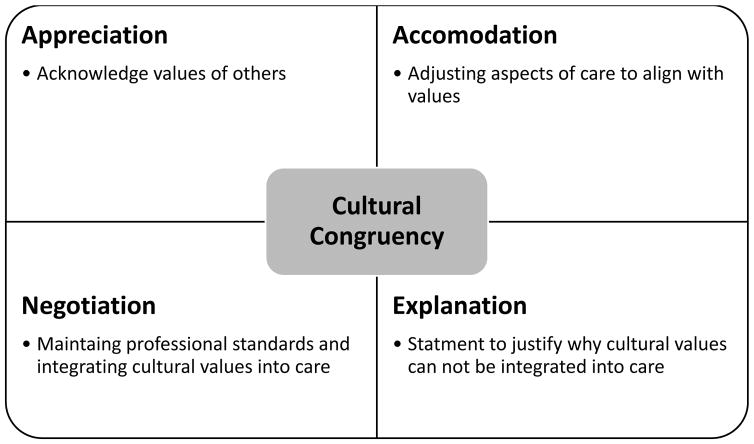

Culturally congruent care is the process by which clinicians and patients are able to effectively communicate despite differences in values, beliefs, perceptions, and expectations about care. Cultural congruency is achieved by creating positive care environments based upon knowledge of the social communities from which the patients come. Schim and Doorenbos (2010) recommend a four-stepped approach that includes appreciation, accommodation, negotiation, and explanation, to achieve this desirable care environment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Core Concepts of Cultural Congruency

Appreciation

Appreciation is simply the acknowledgement by the clinician of the varying personal beliefs, values, and life patterns patients may have. Appreciation can be achieved by working diligently to understand differences by making observations and asking open-ended, related questions. For example, religious beliefs and spirituality is highest amongst Black Americans as compared to other cultural groups (Boyd-Franklin, 2010) and prayer is a common pain management technique used by Black elders (Booker, 2015; Jones et al., 2008; Park, Lavin, & Couturier, 2014; Robinson, 2015). One research participant, Adam, who uses prayer to manage his pain, explained why it was important to also pray with others in pain, he said, “Pray with them and let them know that when they are in that pain to never be forgetful that Jesus promised us healing. And by his stripes we are the healed,” (Robinson, 2015). A nurse that goes to visit a patient in pain might find them with their eyes closed and quietly talking to themselves. After notifying the patient of their presence and waiting a few moments to be acknowledged, the nurse might say, “I’m sorry were you praying?” Then, if answered affirmatively, they might respond, “I didn’t mean to interrupt your prayers. It seems like you aren’t very comfortable right now and I would like to get you some medication that will work along with your prayers to relieve your pain.” Although, many older Black Americans find prayer to be a helpful and important part of their care and recovery, it is important to communicate with them, in a respectful way, that prayer alone may not sufficiently control high levels of pain. In fact, engagement in more prayer has been associated with lower pain tolerance in Black Americans (Meints & Hirsh, 2015). Despite the noted contrast in the cultural belief and the expected clinical outcome, showing appreciation means recognizing the importance of this practice for many and making reasonable accommodation to integrate it into care.

Accommodation

Accommodation is frequently described as a convenient arrangement, a settlement, or a compromise. When providing culturally congruent care, nurses accommodate the patients they are charged to care for by changing aspects of care as necessary so that the care is in alignment with the patients’ beliefs, values, and preferences. Not only does this create a person-centered care environment, but the patients, families, and communities that are participating in care truly become care partners with individualized plans of care that more likely to be followed, and goals that are more likely to beachieved.

Black elders may have some initial distrust of the medical system and have difficulty relaying pain concerns in ways that are understood and recognized by healthcare providers. Knowing this, the culturally responsive nurse will accommodate the patient as needed, by adjusting the words that they choose to use when communicating about pain, by listening for and using familiar pain terminology. For instance, after conveying respect at the start of a conversation by making sure to address the older adult by their surname, unless asked to do otherwise by the elder, pain assessment questions should begin by asking patients if they are “hurting” or “aching.” Black older adults typically reserve the word “pain” to indicate only severe pain and use words like “hurt,” “sore,” or “discomfort” to describe less-intense pain (Curtiss, 2010). In fact, Black Americans ranked the word ‘pain’ with the highest intensity, followed by the descriptors ‘hurt’ and ‘ache’ (Gaston-Johansson, Albert, Fagan, & Zimmerman, 1990). An emerging assessment area is determining how bothersome and tolerable pain is (S. Booker, Bartoszczyk, & Herr, 2016; S. Q. Booker & Haedtke, 2016) and corresponding treatment threshold (i.e., need for analgesia). To describe bothersome pain, older Black Americans may use descriptors such as nagging, exhausting, miserable, or other pain descriptors (Booker et al., 2015).

In addition, older Black adults may not associate certain sensations with pain, such as chest tightness or neuropathic sensations of “pricking,” “burning,” or “tingling.” Older adults with chronic dull aching pain may answer “no” to questions about pain, because they do not perceive it in a way that they believe pain is “supposed to” present itself (Feldt, 2007). Although, the International Association for the Study of Pain (2011) suggests that “experiences which resemble pain but are not unpleasant, e.g., pricking, should not be called pain”; for some older adults, words like “pricking” may be a preferred means of describing pain.

Using culturally -sensitive communication may initially be uncomfortable to the nurse, and may even feel unnatural. However, by paying careful attention to word choice and being mindful of nonverbal communication, such as how body language and tone of voice is used to relay messages, nurses may develop increased levels of relatability to the persons they are caring for. Any uncertainties the nurse might have should be clarified with the patient or family at the start of care. Unfortunately, despite one’s best efforts, at times, mistakes will still occur. When they do, the misunderstanding should be corrected as soon as possible to maintain patient/provider relationships and facilitate trust. Furthermore, nurses should consider what level of communication is desired by the patient.

While most Black elders want to know the source of their pain, others may fear knowing the cause of pain. They may fear expensive or potentially painful tests and generally want to avoid “probing” or “looking for something.” There may also be a fear that pain is the result of cancer or other serious conditions. Nurses and healthcare providers can establish rapport and engage in culturally-sensitive communication by first addressing any fears Black elders may have regarding their pain and encourage self-report by informing them that “if you feel something, say something.” Nurses should make it explicit that reporting pain is not complaining of pain, nor is it an inconvenience for the nurse, but rather, it is important information to be related that aids in the reduction of discomfort and suffering. This is necessary as complaining is often viewed as a negative attribute in Black culture (S. S. Booker et al., 2015; Robinson, 2015). Although nurses can easily accommodate their patients by adjusting the ways in which they communicate, other aspects of pain management, particularly the use assessment tools are not so easily changed within institutions. This requires negotiation.

Negotiation

Negotiation, or the act of reaching an agreement in culturally congruent care, means finding a common ground where the professional standard of care may be maintained while cultural behaviors are recognized and accommodated as much as possible. Therefore, negotiation might mean that the nurse accommodates the patient by using culturally sensitive communication but maintains the use of pain intensity tools that have been validated across populations. Research has determined that scales such as the Faces Pain Scale-revised (FPS-r), verbal descriptor scale (VDS), and Iowa Pain Thermometer-revised (IPT-r) are valid, reliable, and preferred amongst older Black Americans with and without cognitive impairment (Ware et al., 2015). Scales (e.g., IPT-r), or a combination of scales (e.g., FPS-r and VDS or VDS and Numeric Rating Scale), that target both the affective (unpleasantness) and sensory (intensity/quality) domains of pain is recommended (S. S. Booker et al., 2015). To measure pain intensity, patients should be asked to quantify (0–10 scale) and qualify (mild, moderate, severe) pain intensity by using pain self-report scales.

Negotiation also means effectively managing chronic pain by using recommended stepped, multi-modal approaches that integrate both preferred complementary and alternative strategies along with effective and proven prescription medications (Arnstein & Herr, 2013). Table 2 provides an overview of considerations for various medication classes used to treat mild, moderate, and severe pain in Black older adults. When treating severe pain in particular, nurses should be mindful that Black Americans report significantly greater cancer pain (P<.001), are less likely than Whites to have a prescription for a long acting opioids (P<.001), and are more likely to have a negative pain management index (score of how well pain is managed) (P<.001) (Meghani, Thompson, Chittams, Bruner, & Riegel, 2015). Furthermore, when Black elders do use a prescription opioid, they are more likely to take less than the prescribed amount. In one study, on sub-analysis, analgesic adherence rates for Black Americans ranged from 34% (for weak opioids) to 63% (for long acting opioids) (Meghani et al., 2015). A primary reason for decreased opioid compliance amongst Black older adults is concern about side effects.

Side effects are a commonly reported barrier to medication utilization and adherence in older Blacks adults (Staja Q. Booker, 2015; Meghani et al., 2015; Robinson, 2015). Not unlike other older adults, Black elders often have several comorbidities (i.e., 3 or more) with each requiring separate treatments and medications. The cumulative effect of multiple medications and subsequent side effects often discourages these elders from using prescribed opioid pain medications. Instead, they may attempt to reduce the number of medications, and severity of side effects, by foregoing pain treatment with medications, and opting to use more non-pharmacological strategies such as prayer, creams/salves, physical activity, or rest (Park et al., 2014; Robinson, 2015). Moreover, pain may not be their priority concern as compared to other health conditions, and this perception then also limits their use of pain medications.

An additional side effect related concern that may further limit the use of pain medications amongst Black elders, is that the inactive ingredients used in some medications may not be tolerated by the gastrointestinal systems of these patients (Campinha-Bacote, 2007). For example, lactose is used as a filler in some medications, but 70–90% of Blacks are lactose intolerant (National Medical Association, 2009). When practicing culturally responsive care, the nurse understands the hesitancy of some Black elders to take opioid analgesics and then uses negotiation as a means of identifying and integrating into care the most acceptable medications and treatments—which for many are a combination of herbal remedies, prescription medications, and topical analgesics (Cherniack et al., 2008; Robinson, 2015).

Often older Black adults serve as vessels of wisdom regarding knowledge of various folk remedies and many in the community seek their advice about how to treat pain and other health conditions. Nurses can convey respect, build rapport, and create a caring environment by inquiring with the patient and family about the ways in which home remedies, such as alcohol rubs, Epsom salt soaks, heating pads and other treatments are typically used at home and then working to integrate some of these care practices into the patient’s plan of care as feasible and desired. An older Black adult might be particularly appreciative of, and more receptive to, an effective oral analgesic when it is accompanied by a quick massage with a topical analgesic they are familiar with. When the nurse is not able to meet the patient’s care expectations through appreciation, accommodation, or negotiation, an explanation is required (Schim & Doorenbos, 2010).

Explanation

Explanation or statements to make actions more clear and justified, is the final component of culturally congruent care. Explanation is required when the culturally responsive nurse is unable to accommodate patient and family wishes regarding care. More often than not, explanation is likely to occur when the patient desires a particular treatment or practice that would be considered unsafe in some way. For example, isopropyl alcohol with various additives such as menthol or capsaicin may be used by Black elders (Robinson, 2015). Although a patient may be accustomed to using this preparation in a home setting, nursing home and acute care regulations may prevent the use of this treatment considering it to be both ineffective and a safety hazard. The culturally responsive nurse would provide explanation to the patient and family and return to negotiation to find an acceptable middle ground. In this instance, it might be integrating the use of an approved commercial topical rub that has the cooling effect of isopropyl alcohol, the scent of menthol, or the heat from capsaicin.

Integrating into Clinical Care

Ultimately, there are many ways in which the culturally responsive nurse can facilitate effective and appropriate care that is most likely to meet the holistic needs of diverse patients such as Black older adults with pain. Integrating the SIR Pain Card (Figure 2) into clinical care is one way to facilitate culturally responsive care. While national guidelines outlined by the US Department of Health and Human Services (2016) describe the ways in which organizations can become more culturally competent in the delivery of healthcare services, individual clinician actions play a central role in the health outcomes of diverse populations. By recognizing the unique attributes of the patients they care for, particularly their values and important health beliefs, nurses are able to more fully engage patients in health promotion and optimization, and reduce suffering. Black older adults in particular have a long history of dealing with racism, chronic environmental stressors, and receiving less than optimal care from the health care system. Providing culturally responsive care for this population means taking extra effort to relay appreciation of cultural strengths and values by asking open ended questions about care goals and health beliefs and practices. Accommodations can then be made that allow for the integration of these important health beliefs and practices into care. It is understood that negotiation may have to take place at times to provide person-centered care and remain compliant within regulatory frameworks. Finally, explanations are provided in respectful and relatable ways when care expectations can not be met.

Figure 2.

Screen, Intervene, & Reconvene (SIR©) Pain Card

The prudent nurse works diligently to provide culturally congruent care and is cognizant of their own values and biases that have the potential to negatively affect the care they provide. As nurses begin to recognize their own cultural identities and remain open to engaging in lifelong learning about cultures that vary from their own, they begin to practice in a space that is other-oriented—one of cultural humility. When nurses begin to practice cultural humility, not only do they improve the health of Black older adults—they ultimately improve the health of the nation.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32 NR011147. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Healthcare Disparities Report. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. (11-0005) Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr10/nhdr10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett MJ, Thorpe RJ, Jr, Gaskin DJ, Bowie JV, LaVeist TA. Race, medical mistrust, and segregation in primary care as usual source of care: Findings from the exploring health disparities in integrated communities study. Journal of Urban Health. 2016;93(3):456–467. doi: 10.1007/s11524-016-0054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein P, Herr K. Risk evaluation and mitigation strategies for older adults with persistent pain. J Gerontol Nurs. 2013;39(4):56–65. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20130221-01. quiz 66–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazargan M, Yazdanshenas H, Gordon D, Orum G. Pain in Community-Dwelling Elderly African Americans. J Aging Health. 2016;28(3):403–425. doi: 10.1177/0898264315592600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker S, Bartoszczyk D, Herr K. Managing Pain in Frail Elders. American Nurse Today. 2016;11(4) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker S, Pasero C, Herr KA. Practice recommendations for pain assessment by self-report with African American older adults. Geriatric Nursing. 2015;36(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2014.08.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker SQ. Older African Americans’ Beliefs about Pain, Biomedicine, and Spiritual Medicine. Journal of Christian Nursing. 2015;32(3):148–155. doi: 10.1097/cnj.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker SQ, Haedtke C. Evaluating pain management in older adults. Nursing. 2016;46(6):66–69. doi: 10.1097/01.nurse.0000482868.40461.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker SS, Herr KA. Pain Management for Older African Americans in the Perianesthesia Setting: The “Eight I’s”. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing. 2015;30(3):181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Incorporating spirituality and religion in the treatment of African American Clients. The Counseling Psychologist. 2010;38(7):976–1000. doi: 10.1177/0011000010374881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Gallo LC, Myers HF. Race, racism and health: disparities, mechanisms, and interventions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;32(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DJ, Grill J, Noorbaloochi S, Griffin JM, Ricards J, van Ryn M, Partin MR. The effect of perceived racial discrimination on bodily pain among older African American men. Pain Med. 2009;10(8):1341–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campinha-Bacote J. Becoming culturally competent in ethnic psychopharmacology. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2007;45(9):27–33. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20070901-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carteret M. Culturally Responsive Care. Key Concepts in Cross-Cultural Communications. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.dimensionsofculture.com/2010/10/576/

- Cherniack EP, Ceron-Fuentes J, Florez H, Sandals L, Rodriguez O, Palacios JC. Influence of race and ethnicity on alternative medicine as a self-treatment preference for common medical conditions in a population of multi-ethnic urban elderly. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14(2):116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintron A, Morrison RS. Pain and ethnicity in the United States: A systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(6):1454–1473. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Almeida Y, Sibille KT, Goodin BR, Ruiter M, Bartley EJ, Riley JL, … Fillingim RB. Racial and ethnic differences in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(7):1800–1810. doi: 10.1002/art.38620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas AG, O’Brien K, Saha S. African Americans experiences in healthcare: “I always feel like I’m getting skipped over. Health Psychology. 2016;35(9):987–995. doi: 10.1037/hea0000368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtiss CP. Challenges in pain assessment in cognitively intact and cognitively impaired older adults with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2010 Sep;37:7. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.S1.7-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D, Baker T, Carrion IV, Vongxaiburana E, Hyer K. Certified nursing assistants’ perspectives of nursing home residents’ pain experience: Communication patterns, cultural context, and the role of empathy. Pain Management Nursing. 2014;15(1):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR. The association of perceived discrimination with low back pain. J Behav Med. 2008;31(5):379–389. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwa MO, Fleming MF. Racial Disparities in Pain Management in Primary Care. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2012;5(3):12–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldt K. Pain measurement: present concerns and future directions. Pain Med. 2007;8(7):541–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston-Johansson F, Albert M, Fagan E, Zimmerman L. Similarities in pain descriptions of four different ethnic-culture groups. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1990;5(2):94–100. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(05)80022-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(05)80022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Metzl JM, Gunter K. Considering intersections of race and gender in interventions that address US men’s health disparities. Public Health. 2011;125(7):417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.04.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP. Psychosocial correlates of medical mistrust among African American men. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;54(1):87–106. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9280-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IASP Task Force on Taxonomy. IASP Pain Terminology. Part III: Pain Terms, A Current List with Definitions and Notes on Usage. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.iasp-pain.org/Content/NavigationMenu/GeneralResourceLinks/PainDefinitions/default.htm.

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. 2011 Retrieved from http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=13172&page=R1. [PubMed]

- Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA. Race and Unhealthy Behaviors: Chronic Stress, the HPA Axis, and Physical and Mental Health Disparities Over the Life Course. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(5):933–939. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AC, Kwoh CK, Groeneveld PW, Mor M, Geng M, Ibrahim SA. Investigating Racial Differences in Coping with Chronic Osteoarthritis Pain. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2008;23(4):339–347. doi: 10.1007/s10823-008-9071-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen S, Nazroo JY. Agency and structure: the impact of ethnic identity and racism on the health of ethnic minority people. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2002;24(1):1–20. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.00001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karter AJ, Laiteerapong N, Chin MH, Moffet HH, Parker MM, Sudore R, … Huang ES. Ethnic Differences in Geriatric Conditions and Diabetes Complications Among Older, Insured Adults With Diabetes: The Diabetes and Aging Study. J Aging Health. 2015;27(5):894–918. doi: 10.1177/0898264315569455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limaye SS, Katz P. Challenges of Pain Assessment and Management in the Minority Elderly Population. Annals of Long Term Care. 2006;14(11):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski B. A Scientific Theory of Culture and Other Essays. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:201–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghani SH, Thompson AM, Chittams J, Bruner DW, Riegel B. Adherence to Analgesics for Cancer Pain: A Comparative Study of African Americans and Whites Using an Electronic Monitoring Device. J Pain. 2015;16(9):825–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meints SM, Hirsh AT. In Vivo Praying and Catastrophizing Mediate the Race Differences in Experimental Pain Sensitivity. The Journal of Pain. 2015;16(5):491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.02.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosleley KL, Freed GL, Bullard CM, Goold SD. Measuring African-American parents’ bultural mistrust whil in a healthcare setting: a pilot study. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007;99(1):15–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2006: With Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Medical Association. Lactose intolerance and African Americans: implications for the consumption of appropriate intake levels of key nutrients. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(10 Suppl):5s–23s. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanker D. Enslaved by Pain: How the U.S. Public Health System Adds to Disparities in Pain Treatment for African Americans. The Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy. 2008;XV(3):847–877. [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Lavin R, Couturier B. Choice of nonpharmacological pain therapies by ethnically diverse older adults. Pain Management. 2014;4(6):389–406. doi: 10.2217/pmt.14.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahim-Williams FB, Riley JL, Herrera D, Campbell C, Hastie BA, Fillingim RB. Ethnic Identity Predicts Experimental Pain Sensitivity In African Americans and Hispanics. Pain. 2007;129(1–2):177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JL, 3rd, Cruz-Almeida Y, Glover TL, King CD, Goodin BR, Sibille KT, … Fillingim RB. Age and race effects on pain sensitivity and modulation among middle-aged and older adults. J Pain. 2014;15(3):272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SG. The unique work of nursing. Nursing. 2013;43(3):42–43. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000426623.60917.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SG. The Experiences of Black American Older Adults Managing Pain: A Nursing Ethnograpy. Wayne State University Dissertations, (1350); Detroit, MI: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schim SM, Doorenbos A, Benkert R, Miller J. Culturally congruent care: putting the puzzle together. J Transcult Nurs. 2007;18(2):103–110. doi: 10.1177/1043659606298613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schim SM, Doorenbos AZ. A three-dimensional model of cultural congruence: framework for intervention. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2010;6(3–4):256–270. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2010.529023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott HJ. The African American Culture. View Point: Commentaries on the Quest to Improve the Life Chances and the Educational Lot of African Americans. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.pace.edu/emplibrary/VP-THEAFRICANAMERICANCULTURE_Hugh_J_Scott.pdf.

- Shavers VL, Bakos A, Sheppard VB. Race, Ethnicity, and Pain among the U.S. Adult Population. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2010;21(1):177–220. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripp-Reimer T, Fox S. Beyond the concept of culture, or how knowing the cultural formula does not predict clinical success. In: Dochterman JM, Grace HK, editors. Current Issues in Nursing. Mosby: 1990. pp. 542–546. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) The National CLAS Standards. 2016 Jun 17; Retrieved from http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=53.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Selected Population Profile in the United States: 2010 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. American Fact Finder. 2010 Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_10_1YR_S0201&prodType=table.

- Ware LJ, Herr KA, Booker SS, Dotson K, Key J, Poindexter N, … Packard A. Psychometric Evaluation of the Revised Iowa Pain Thermometer (IPT-R) in a Sample of Diverse Cognitively Intact and Impaired Older Adults: A Pilot Study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(4):475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington HA. Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present. Doubleday Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. The Health of Men: Structured Inequalities and Opportunities. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(5):724–731. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors H. Racism, discrimination and hypertension: evidence and needed research. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(4):800–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]