Abstract

The aim of this study is to emphasise the importance of preserving the anterior facial skeleton in angiofibroma surgery and to introduce a new approach by which tumors with far lateral extensions can be operated upon successfully without disruption of the anterior facial skeleton. This is a prospective study conducted at a tertiary referral academic centre. Two patients with extensive juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma with far lateral extensions were recruited and they underwent surgery between July and August 2016. Both patients were not embolised prior to surgery. Complete tumor removal was achieved in both cases without any evidence of recurrence of disease. The facial contour was well maintained. They are under regular follow-up at our centre, having completed their third 3 monthly follow-up. The main outcome measures are preservation of the anterior facial skeleton and complete tumor removal. The Four-Port Bradoo Technique allows for maximum access to the angiofibroma whilst maintaining the anterior facial skeleton, thus ensuring complete removal with minimal morbidity to the patient.

Keywords: Four-Port, Bradoo Technique, Angiofibroma, Modified Endoscopic Denker’s approach, Infratemporal fossa, Parapharyngeal spread, Morbidity

Introduction

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma has always been a surgically difficult tumor to treat. Its vascularity, propensity to grow intracranially through various fissures and foramina in the base skull and its ability to burrow into the marrow spaces in diploic bone without destroying the surrounding compact bone makes it a challenge to operate upon successfully. There have been many approaches described for excising these tumors - the traditional open approaches, the endoscopic approach [1], the combined or endoscopic assisted approach [2, 3], the Push–Pull approach [4] the endoscopic Modified Denker’s approach [5] and more recently the multiport approaches through both the nasal and oral cavities [6, 7]. We propose a technique whereby large, lateral extensions of the tumors can be accessed and removed without violating the anterior facial skeleton, thereby preventing facial deformity in the future.

Methods

Two patients of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma with large lateral extensions in the infratemporal fossa and the parapharyngeal space were chosen for this approach.

After decongestion of the nose, the septum was infiltrated and a posterior septectomy was performed by removing parts of the vomer and the perpendicular part of the ethmoid bone. Care was taken not to destabilise the quadrangular cartilage. The two nostrils thus became port A and port B.

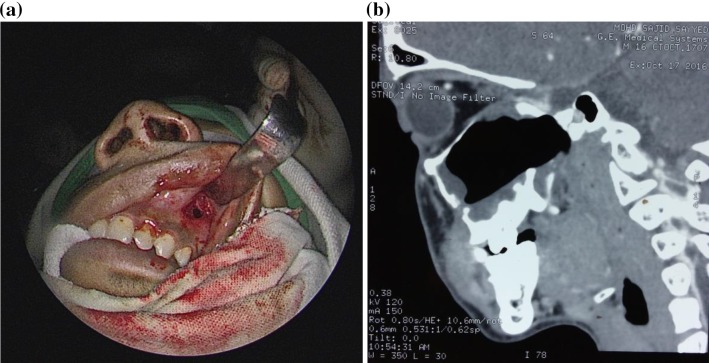

The buccogingival sulcus in the region of the canine fossa was infiltrated with 2% xylocaine adrenaline solution. An incision of approximately 2.5 cm was taken to expose the anterior wall of the maxilla. An antral window was created by removing enough bone to allow free access for a scope and an instrument, approximately 2 × 2 cm. Care was taken not to damage the frontonasal process of the maxilla or the infra-orbital nerve. This became port C (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

a Intra-operative photograph, b post-operative CT scan showing the antral window (port C)

A fourth port of access was then created. After infiltrating with 2% xylocaine adrenaline, a second incision of 2.5 cm was made in the buccogingival sulcus at the level of the last molar. This became port D (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Figure depicting the buccogingival incision at the last molar (port D)

Thus, the angiofibroma could be accessed anteriorly through any one of these 4 ports (Fig. 3).

-

(A)

The contralateral nostril.

-

(B)

The ipsilateral nostril after doing a posterior septectomy.

-

(C)

An antral window in the canine fossa.

-

(D)

An incision of one inch in the buccogingival sulcus adjacent to the last molar. This has been previously described by the author in the Push–Pull approach [4].

Fig. 3.

Figure depicting the Four-Port Bradoo Technique

These ports significantly improved lateral access to the tumor and its feeding vessel—the maxillary artery—without removal of the frontonasal process or the nasolacrimal duct. The scope and various instruments could be passed interchangeably through two or more of these ports, at various stages of the surgery to ensure maximum visualization as well as reach of the instruments.

After creating these ports the nasal portion of the tumor was first excised using port A and B to create space in the nasal cavity.

Port D was used primarily by an assistant surgeon to insert a finger into the infratemporal fossa, although it could also be used to pass instruments as well. The assistant did not dissect with his finger as the maxillary artery would have then been at a risk of being torn. He simply stabilized the tumor so that it did not keep falling back laterally as the primary surgeon worked endoscopically through the nostrils to deliver it (Fig. 2).

The maxillary artery was ligated. The infra-orbital nerve was separated. This was done primarily using ports B and C. Once the tumor was separated from all its adhesions, it was pushed medially into the nasal cavity and delivered out. The access to the intraorbital and the intracranial parts of the tumor thus became easier.

Results

Post-operative CT scans done prior to discharge showed complete tumor removal in both cases (Fig. 4). The first patient (M.S.) was transfused 4 units of blood and the second patient (V.P.) was transfused 2 units. At 9 months follow-up in both cases, there is no evidence of recurrence of tumor and the facial contour is well maintained.

Fig. 4.

Pre and post-op CT scan (coronal and axial views) showing preservation of the anterior facial skeleton with complete removal of the tumor

Discussion

Endoscopic excision of angiofibroma is now a well-accepted method of treating these tumors [8]. With increasing expertise, it is possible to excise intraorbital and intracranial extensions endoscopically [9]. This requires removal of the various components of the skull base such as the lateral wall of the sphenoid, the pterygoid base, the pterygoid plates, the greater wing of the sphenoid, medial and inferior walls of the orbit. Inspite of such extensive bone removal, there is no significant morbidity in terms of appearance of the patient. However, this is not the case with lateral extensions of the tumor such as in the infratemporal fossa, temporal fossa, parapharyngeal space. Access to these areas is impeded by certain ‘pillars’ of the anterior facial skeleton.

Removal of these pillars may not cause an immediate change in the facial contour but can cause facial deformity in the long term (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Figure showing ports of access and the three pillars. Access: A contralateral nostril, B ipsilateral nostril, C antral window, D incision in buccogingival sulcus next to last molar. Pillars: P 1 septum, P 2 frontonasal process of maxilla, P 3 lateral edge of the maxilla

The septum forms the first ‘pillar’. The second ‘pillar’ is the pyriform aperture which is formed by the frontonasal process of the maxilla within which lies the nasolacrimal duct and lacrimal sac. The third ‘pillar’ is the far lateral edge of the maxilla with its zygomatic process.

The endoscopic modified Denker’s approach has gained popularity in the recent years as it enables the surgeon to access the lateral extensions of the tumor in the infratemporal and parapharyngeal regions. This approach involves removal of the frontonasal process of the maxilla to widen the pyriform aperture and removal of the nasolacrimal duct and at times the lacrimal sac. It is being especially practiced in those centres where the facilities of embolization are unavailable as it helps create access to clamp the maxillary artery at the beginning of the surgery itself.

While this approach is relatively simpler surgically and provides a wide access, it has significant disadvantages and post-operative morbidity. There is a change in the facial contour and ablation of the nasolacrimal system. Facial deformity with ectropion of the eye is even more pronounced in those patients where part of the floor and medial wall of the orbit have been removed to access intraorbital and intracranial extensions of the tumor even if the inferior orbital rim is maintained. The deformity worsens with time as the fibrosis in the operated field increases. The growth patterns of the midface are also disturbed, and these need to be studied in more detail. Disturbance in lacrimation leads first to disturbing epiphora, and as the ectropion becomes more evident, to a persistently congested, dry eye (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Post-operative pictures comparing the long-term outcome after a removing the ‘pillars’ and b preserving the ‘pillars’

This outcome is particularly unfortunate following angiofibroma surgery as the tumor never involves or is adherent to the anterior facial skeleton or lacrimal apparatus (unlike the inverted papilloma [10, 11]). Also, these patients are young boys in whom facial deformity and disruption of growth centres have significant life-long implications. The above disadvantages have necessitated the need to develop a technique whereby a similar exposure can be obtained but the subsequent disadvantage of disfiguring the facial contour can be avoided.

This technique, which we propose to name as the ‘Four-Port Bradoo Technique’ follows the principle of preserving the ‘pillars’ of support of the facial skeleton without compromising access for complete excision of the tumor. The four ports can be used interchangeably whilst excising the tumor. The impediment caused by the first ‘pillar’ i.e. the septum is overcome by doing a posterior septectomy for a binostril approach which uses the port A and B. Since the quadrangular cartilage of the septum is maintained, there is no significant increase in morbidity. The ports B and C together help circumvent the second pillar i.e. the frontonasal process of the maxilla. Similarly, the third pillar i.e. lateral edge of the maxilla and its zygomatic process can be circumvented by using port C and port D together.

Conclusion

The basic tenet of any endoscopic surgery is to gain maximum access with a minimally invasive approach. The Four-Port Bradoo Technique allows for maximum access to the angiofibroma, thus ensuring complete removal with minimal morbidity to the patient.

Key Messages

The nasal septum, the frontonasal process of the maxilla and the far lateral edge of the maxilla with its zygomatic process form 3 pillars of the anterior facial skeleton.

Removing these pillars for access in angiofibroma surgery can result in change of the facial contour. This deformity worsens with time due to fibrosis.

Using four different ports i.e. the two nostrils, an antral window and a sublabial incision adjacent to the last molar, allows maximum access to the tumour without damaging these pillars and without compromising complete tumour removal.

This technique ensures that the facial contour is maintained even after removal of angiofibromas with far lateral extensions.

References

- 1.Ardehali MM, Ardestani SHS, Yazdani N, Goodarzi H, Bastaninejad S. Endoscopic approach for excision of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: complications and outcomes. Am J Otolaryngol Head Neck Med Surg. 2010;31(5):343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall AH, Bradley PJ. Management dilemmas in the treatment and follow-up of advanced juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Orl. 2006;68(5):273–278. doi: 10.1159/000093218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prosser JD, Figueroa R, Carrau RI, Ong YK, Solares CA. Quantitative analysis of endoscopic endonasal approaches to the infratemporal fossa. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(8):1601–1605. doi: 10.1002/lary.21863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradoo RA, Joshi AA, Pathan FA, Kalel KP. The push–pull technique in the management of giant JNAs. Bombay Hosp J. 2008;50(2):220. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D, Wang J, Yu H, Pasic TR, Kern RC. Endoscopic modified endonasal Denker operation for management of tumor in pterygopalatine and infratemporal fossae. Skull Base. 2009;19(S 02):A091. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dallan I, Castelnuovo P, Montevecchi F. Combined transoral transnasal robotic-assisted nasopharyngectomy: a cadaveric feasibility study. Eur Arch. 2012;269(1):235–239. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1550-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janakiram TN, Sharma SB, Gattani VN. Multiport combined endoscopic approach to nonembolized Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma with parapharyngeal extension: an emerging concept. Int J Otolaryngol. 2016;2016:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2016/4203160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Midilli R, Karci B, Akyildiz S. Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: analysis of 42 cases and important aspects of endoscopic approach. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(3):401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godoy MDCL, Bezerra TFP, de Rezende Pinna F, Voegels RL. Complications in the endoscopic and endoscopic-assisted treatment of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma with intracranial extension. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;80(2):120–125. doi: 10.5935/1808-8694.20140026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanderson RJ, Knegt P. Management of inverted papilloma via Denker’s approach. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1999;24(1):69–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1999.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chai CK, Tang IP, Prepageran N. A review of inverted papilloma at a tertiary centre: a six-year experience. Int J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;2:156–159. doi: 10.4236/ijohns.2013.25034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]