Abstract

Motor abnormalities are frequently observed in schizophrenia and structural alterations of the motor system have been reported. The association of aberrant motor network function, however, has not been tested. We hypothesized that abnormal functional connectivity would be related to the degree of motor abnormalities in schizophrenia. In 90 subjects (46 patients) we obtained resting stated functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) for 8 minutes 40 seconds at 3T. Participants further completed a motor battery on the scanning day. Regions of interest (ROI) were cortical motor areas, basal ganglia, thalamus and motor cerebellum. We computed ROI-to-ROI functional connectivity. Principal component analyses of motor behavioral data produced 4 factors (primary motor, catatonia and dyskinesia, coordination, and spontaneous motor activity). Motor factors were correlated with connectivity values. Schizophrenia was characterized by hyperconnectivity in 3 main areas: motor cortices to thalamus, motor cortices to cerebellum, and prefrontal cortex to the subthalamic nucleus. In patients, thalamocortical hyperconnectivity was linked to catatonia and dyskinesia, whereas aberrant connectivity between rostral anterior cingulate and caudate was linked to the primary motor factor. Likewise, connectivity between motor cortex and cerebellum correlated with spontaneous motor activity. Therefore, altered functional connectivity suggests a specific intrinsic and tonic neural abnormality in the motor system in schizophrenia. Furthermore, altered neural activity at rest was linked to motor abnormalities on the behavioral level. Thus, aberrant resting state connectivity may indicate a system out of balance, which produces characteristic behavioral alterations.

Keywords: STN, cerebellum, basal ganglia, dysconnectivity

Introduction

Schizophrenia is characterized by several distinct symptom dimensions, including abnormal psychomotor behavior. Motor symptoms are frequent in schizophrenia, observed in unmedicated first episode patients as well as in chronic and medicated patients.1 Motor abnormalities are also intimately linked to the risk of psychosis, as evidenced by findings in unaffected first-degree relatives or subjects at high clinical risk for psychosis.2–4 Furthermore, some motor abnormalities have predictive value indicating poor outcome in schizophrenia.5,6

Motor abnormalities include a variety of clinical signs and syndromes, such as parkinsonism, catatonia, abnormal involuntary movements (ie, dyskinesia), altered spontaneous motor activity and neurological soft signs (ie, problems in movement sequencing and coordination).1 Studies assessing more than one motor abnormality reported 3 or more symptom clusters in schizophrenia patients depending on the methods applied. Still, most reports found hypokinesia (eg, parkinsonism, catatonia, and psychomotor slowing), hyperkinesia (eg, dyskinesia), and coordination.7–10 Even though these motor abnormalities are referred to as distinct phenomena, there is considerable conceptual overlap between signs.1

Structural and functional brain alterations are thought to underlie schizophrenia and some of these alterations are located in the motor system.11 For example, studies in schizophrenia patients reported reduced volumes of the primary and secondary motor cortices12 or basal ganglia,13 aberrant white matter organization in motor tracts such as the corticospinal tract or the internal capsule,12,14,15 altered cerebral blood flow (CBF) in basal ganglia and thalamus,16–21 and altered functional activation of basal ganglia and cerebellum.22,23 Indeed, motor abnormalities have been associated with structural and functional alterations of the cerebral motor system including white matter properties,24–28 cortical thickness or cortical volume,29,30 basal ganglia volumes,31,32 resting state perfusion17,33 or reduced activation in BOLD functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).34,35 Together, these findings suggest that motor abnormalities are linked to structural and functional brain alterations in key parts of the motor system. Most of the previous findings focused on structural alterations within the motor system. But little is known on functional alterations, due to difficulties of eliciting reliable and relevant task-based brain activity in this population. Given, that the motor system was dysfunctional in schizophrenia, functional alterations may not only be elucidated by fMRI tasks but also be present at rest. In fact, we linked resting state brain perfusion within the cortical premotor areas with spontaneous motor activity or the catatonic syndrome.17,33 Previous work however, has not investigated the associations of functional alterations with motor abnormalities from a network perspective.

Functional connectivity at rest is altered across the brain in schizophrenia, with studies reporting reduced thalamocortical connectivity to the prefrontal cortex and at the same time increased thalamocortical connectivity to the motor cortex.36–38 Thalamocortical and cerebello-cortical dysconnectivity are already present in subjects at clinical high risk for psychosis.39,40 In addition, massive reduction of functional connectivity within sensorimotor networks was observed in schizophrenia.41,42 In sum, evidence suggests pronounced alterations of functional connectivity in schizophrenia include parts of the cerebral motor system. However, previous studies of functional connectivity never focused on the cerebral motor system as a network and none of the reports investigated whether altered functional connectivity was linked to aberrant motor behavior in schizophrenia. Here, we aimed at elucidating this issue by investigating both motor abnormalities at the behavioral level and resting state functional connectivity within the cerebral motor system. We applied ROI-to-ROI analysis of connectivity in a set of 24 ROIs of the motor system. We hypothesized aberrant resting state connectivity in schizophrenia, particularly increased connectivity in thalamocortical connections, but also increased connectivity between cerebellum and motor cortices. Furthermore, we expected that domains of motor abnormalities would have distinct correlations with resting state dysconnectivity within the motor system in schizophrenia. For example, we expected that hypokinesia would be associated with increased connectivity from premotor cortex to thalamus and coordination with reduced connectivity between cerebellum and motor cortex or basal ganglia.34

Methods

Participants

In this study we included 46 patients and 44 healthy controls matched for age, gender, and education. Participants were recruited either at the inpatient and outpatient departments of the University Hospital of Psychiatry, Bern, Switzerland, or among staff and via advertisement. All subjects were right handed as determined by the Edinburgh handedness inventory.43 Exclusion criteria were substance abuse or dependence other than nicotine; past or current medical condition impairing movements, such as dystonia, multiple sclerosis, idiopathic parkinsonism, or stroke; history of head trauma with concurrent loss of consciousness; and history of electroconvulsive treatment. Exclusion criteria for controls were a history of any psychiatric disorder as well as any first-degree relatives with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

All participants were interviewed with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview,44 patients also with the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History.45 Diagnoses were given according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition criteria (n = 41 schizophrenia, n = 1 schizoaffective disorder, and n = 4 schizophreniform disorder). The test of nonverbal intelligence (TONI)46 was applied in all participants. All but 4 patients received antipsychotic pharmacotherapy (87% second generation antipsychotics). Clinical and demographic data are given in table 1. All participants provided written informed consent. The protocol was approved by the local ethics committee.

Table 1.

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

| Controls | Patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 44 | n = 46 | X 2 | df | P | |||

| Gender (% male) | 59.1% | 63.0% | 0.148 | 1 | .829 | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | df | P | |

| Age (y) | 38.8 | 13.6 | 38.0 | 11.5 | −0.276 | 88 | .783 |

| Education (y) | 14.1 | 2.7 | 13.5 | 3.1 | −1.096 | 88 | .276 |

| TONI index score | 110.6 | 10.1 | 97.2 | 11.3 | −5.914 | 87 | <.001 |

| BFCRS | 0 | 0 | 1.8 | 3.6 | |||

| NES total | 3.7 | 3.7 | 14.2 | 11.3 | 5.938 | 55.2 | <.001 |

| UPDRS III | 0 | 0 | 4.9 | 5.0 | |||

| MRS total | 0 | 0 | 3.1 | 5.3 | |||

| AIMS total | 0.2 | .8 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 3.651 | 49.3 | .001 |

| AL (counts/h) | 21511.2 | 7579.6 | 15118.4 | 8310.9 | −3.481 | 73 | .001 |

| FT right | 40.7 | 7.8 | 34.6 | 9.0 | −3.388 | 86 | .001 |

| CPZ (mg) | 444.6 | 337.0 | |||||

| CPZ 5 years (mg) | 241.4 | 281.9 | |||||

| PANSS p | 18.1 | 6.5 | |||||

| PANSS n | 18.4 | 5.1 | |||||

| PANSS tot | 72.7 | 17.3 | |||||

| DOI (y) | 12.1 | 12.4 | |||||

| DOT (y) | 11.2 | 12.1 | |||||

Note: AIMS, abnormal involuntary movement scale; AL, activity level; BFCRS, Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale; CPZ, chlorpromazine equivalents of the current treatment; CPZ 5 years, mean daily CPZ over the past 5 years; DOI, duration of illness; DOT, duration of antipsychotic treatment; FT, finger tapping (score of 10 s); MRS, modified Rogers Scale; NES, neurological evaluation scale; PANSS, positive and negative syndrome scale; TONI, test of nonverbal intelligence; UPDRS III, motor part of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

Procedures

Participants underwent neuroimaging acquisition. On the same day a comprehensive motor battery was assessed including motor rating scales on catatonia (Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale [BFCRS]47 and Modified Rogers Scale [MRS]48), parkinsonism (Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale [UPDRS] motor part49 and MRS), abnormal involuntary movements (Abnormal involuntary movement scale [AIMS]50), and neurological soft signs (Neurological evaluation scale [NES]51). All ratings were performed by one rater (K.S.) who had been trained to achieve κ > 0.8 with the principal investigator (S.W.). The assessments were conducted according to the original description of the instruments within one examination session.

Furthermore, the motor battery included finger tapping with thumb and index finger of the right hand at maximum speed for 10 seconds recorded on video (3 runs, the average number of taps was used for analyses) and continuous recording of spontaneous motor activity using wrist actigraphy (Actiwatch, Cambridge Neurotechnology, Inc., on the nondominant arm, data storage at 2 s rate). Participants wore the actigraph for 24 hours. The activity level (movement counts/h) was calculated for all non-sleep periods.26,52

Neuroimaging

Imaging was performed on a 3T MRI scanner (Siemens Magnetom Trio; Siemens Medical Solutions) with a 12-channel radio frequency headcoil for signal reception. Subjects lay horizontal in the MR scanner and their arms rested beside their trunk. Head motion was reduced by foam pads around the participants’ head. 3D-T1-weighted (Modified Driven Equilibrium Fourier Transform Pulse Sequence; MDEFT) images for each subject have been obtained,53 providing 176 sagittal slices with 256 × 256 matrix points with a non-cubic field of view (FOV) of 256 mm, yielding a nominal isotopic resolution of 1 mm3 (ie, 1 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm). Further scan parameters for the anatomical data were 7.92 ms repetition time (TR), 2.48 ms echo time (TE), 900 ms inversion time (Ti) and a flip angle of 16° (FA).

Resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) data were acquired after the structural scans, approximately 20 minutes after the MRI procedures started. An 8-minute 40-second resting state blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) scan was acquired with a T2*-weighted echo-planar sequence (matrix size = 64 × 64; 3.6 × 3.6 × 3.0 mm3 voxels; 38 slices; FOV = 230 mm number of volumes = 256; TR = 2000 ms; TE = 30 ms; FA = 90°). During the acquisition of rs-fMRI participants were asked to relax with their eyes closed without falling asleep. None of the participants reported to have fallen asleep during the resting state acquisition in the post-scan interview.

Functional Connectivity Analyses.

Resting state functional connectivity analysis was performed with the Functional Connectivity Toolbox (CONN, version 17.c)54 for MATLAB (R2015; MathWorks). Prior to starting CONN we performed movement quality checks that revealed for both groups less than 0.5 mm of translation and less than 0.005° of rotation. Therefore, no subjects were excluded as they fulfilled the standard criterion of less than 3 mm of translation and 2° of rotation.55 For the first level analysis we did follow the standard pre-processing pipeline which included several steps: functional realignment and unwarping, centering of the functional and structural image to (0,0,0) coordinates, slice-timing correction, structural segmentation, structural and functional normalization to MNI space and spatial smoothing with a Gaussian filter Kernel of FWHM = 8 mm. Next, the temporal confounding factors, such as subject- and session specific time series (eg, movement parameters) and BOLD signals obtained from subject-specific noise ROIs (white matter and CSF masks) were processed and regressed out from the data. The last preprocessing step included the band-pass filtering of the fMRI data (0.01–0.1 Hz) (see54 for detailed preprocessing steps).

As the aim of the study was to investigate resting state functional connectivity within the motor system, we applied a hypothesis driven approach with functional connectivity analyses between a predefined set of regions of interest (ROI) and computed ROI-to-ROI analyses.

We chose 12 bilateral ROIs using the grey matter Brodmann Area (BA) masks and the automated anatomical labeling (AAL) atlas of the WFU-Pick Atlas software56 running in the Statistic Parametric Mapping (SPM) 12 (The Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). The ROIs included 3 prefrontal cortex ROIs, ie, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), rostral anterior cingulate cortex (rACC) and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), 4 premotor and motor ROIs, ie, supplementary motor area (SMA), pre-SMA, and primary motor cortex (M1), 5 basal ganglia ROIs, ie, caudate (caud), putamen (put), pallidum (pall), and subthalamic nucleus (STN), the thalamus and the motor part of the cerebellum. The prefrontal ROIs are thought to subserve goal and action selection, as well as executive control.11,57,58 Premotor and motor cortical ROIs are engaged in action preparation and movement control. The cerebellar ROI includes the motor areas V, VI, and VIII as we were interested in motor and somatosensory representations.59,60 The DLPFC ROI corresponds to BA 9 and 46; M1 to BA 4 and the cerebellum-ROI includes the lobules V, VI, and VIII. These ROIs were chosen from the BA masks. From the AAL we further defined the basal ganglia and thalamus, as well as ACC and SMA. Both ACC and SMA were split in 2 areas: the ACC was divided in the dorsal ACC (dACC) and rostral (rACC); the SMA in the preSMA and SMA proper. The rACC comprises the parts of the BA 24 that are rostral of a vertical section through the genu.61,62 SMA and preSMA are primarly located at the rostral and caudal parts of the medial premotor cortex (BA6) and are split through the vertical anterior commissure.63

Statistical Analyses

Group differences of clinical and behavioral data were tested with t tests and chi-squared tests where appropriate. All analyses were performed in SPSS 24 (IBM).

Factor Analysis of Motor Assessments.

The motor rating scales and motor tests were subject to principal component analysis (PCA), which extracted components with an eigenvalue > 1 and subsequent varimax rotation. The 4 components explain 81% of the variance: (1) Primary motor (31%, including UPDRS motor part, BFCRS, NES subscales sensory integration, coordination, sequencing and other), (2) Catatonia and Dyskinesia (24%, including AIMS, MRS, BFCRS), (3) Coordination (14%, including NES coordination and finger tapping performance), and (4) Spontaneous motor activity (12%, activity level). The PCA details are given in the supplementary tables S1–S2. The PCA was computed only in patients because schizophrenia motor abnormalities were the focus of the study. Later, factor loadings were derived for all participants allowing between group comparisons and correlations.

rs-fMRI Connectivity.

Group differences were tested and corrected at analysis-level applying false-discovery rate (FDR) correction as implemented in CONN using a threshold of P ≤ .05. In addition, we applied permutation tests in CONN at the analysis level to provide a family-wise-error (FWE) correction of the connectivity intensity using a threshold of P ≤ .05. Finally, for each group separately we calculated exploratory correlations (Pearson) between the 4 motor factor scores with the extracted z-transformed connectivity values from connections with significant group differences.

Results

Motor Behavioral and Clinical Data

The demographic and clinical data are given in table 1. Patients were slower during fingertapping, less active as indicated by lower AL, had more involuntary movements and neurological soft signs. Catatonia and parkinsonism were exclusively observed in patients.

Resting State Functional Connectivity in the Motor System

rs-fMRI Connectivity Within Groups.

The main effect of connectivity across both groups is given in the supplementary table S5. The ROI-to-ROI connectivity for each group is given in supplementary figures S1 and S2. As expected, we detected a functional segregation in controls. Prefrontal cortex ROIs were connected to other prefrontal cortex ROIs. Likewise, premotor and motor cortex ROIs were connected to each other, while preSMA was also connected with the prefrontal ROIs. Basal ganglia ROIs were also connected within their group. Finally, cerebellar ROIs were connected with basal ganglia and thalamus. The situation in patients appeared quite similar with 3 exceptions: We detected connectivity between cerebellum and premotor/motor cortices, between prefrontal cortical areas and SMA/M1 and much more cortical areas were connected to STN.

rs-fMRI Connectivity Between Groups.

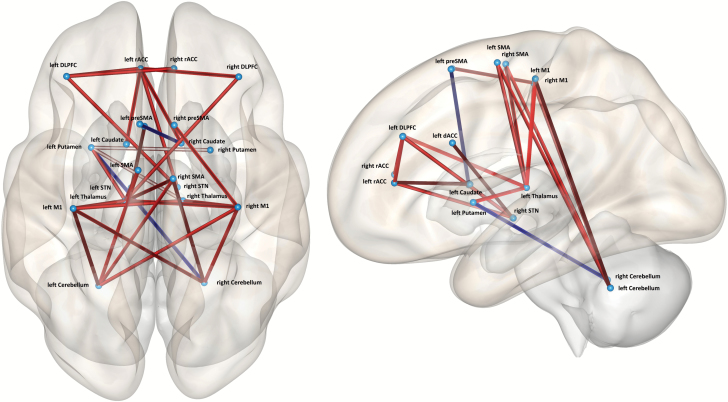

In 18 connections we found group differences, mostly increased connectivity in patients (see table 2, supplementary table S7, and figure 1). Increased functional connectivity in patients was particularly evident in the connections from both M1 and SMA to bilateral cerebellum, from bilateral M1 to left Thalamus and from prefrontal seeds to the bilateral STN. Connections included both ipsilateral and contralateral directions. In 2 connections of the motor system patients had reduced functional connectivity: left preSMA-right caudate and left putamen-right cerebellum. The group contrast of the seed-to-voxel connectivity for patients ≥ controls is given in the supplementary table S6.

Table 2.

Group Differences in rs-fMRI Contrast Patients > Controls

| Seed | F(18) | P-FDR | Target | T(88) | P-FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left DLPFC | 2.27 | .0162 | Right STN | 3.38 | .0212 |

| Right rACC | 3.10 | .0408 | |||

| Right DLPFC | 2.02 | .0308 | Left rACC | 3.44 | .0206 |

| Left rACC | 4.34 | .0001 | Right STN | 3.28 | .0255 |

| Right Caudate | 3.09 | .0408 | |||

| Left dACC | 1.80 | .0571 | Left STN | 3.41 | .0207 |

| Left preSMA | 1.84 | .0522 | Right Caudate | −3.32 | .0241 |

| Left SMA | 3.24 | .0008 | Left Cerebellum | 4.41 | .0016 |

| Right SMA | 3.28 | .0008 | Left Cerebellum | 4.66 | .0010 |

| Right Cerebellum | 3.66 | .0108 | |||

| Left M1 | 3.74 | .0004 | Left Cerebellum | 5.18 | .0004 |

| Left Thalamus | 4.97 | .0005 | |||

| Right Cerebellum | 3.85 | .0088 | |||

| Right M1 | 3.58 | .0005 | right Cerebellum | 4.45 | .0016 |

| Left Thalamus | 4.26 | .0024 | |||

| Left Cerebellum | 3.66 | .0108 | |||

| Left Thalamus | 3.49 | .0005 | Left putamen | 3.73 | .0103 |

| Left Putamen | 2.36 | .0148 | Right Cerebellum | −3.74 | .0103 |

Note: rs-fMRI, resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; rACC, rostral anterior cingulate cortex; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; SMA, supplementary motor area; M1, primary motor cortex; STN, subthalamic nucleus; FDR, false-discovery rate. Connections are only presented in one direction for the sake of clarity. P-values are FDR-corrected at analysis level (omnibus test across all connections). Additional information regarding the connectivity intensities can be found in the supplementary table S7.

Fig. 1.

ROI-to-ROI connectivity differences (patients > controls). Red indicates increased connectivity, blue reduced connectivity compared to controls. P(FDR) < .05 at analyses level corrected.

Association of Functional Connectivity With Motor Abnormalities.

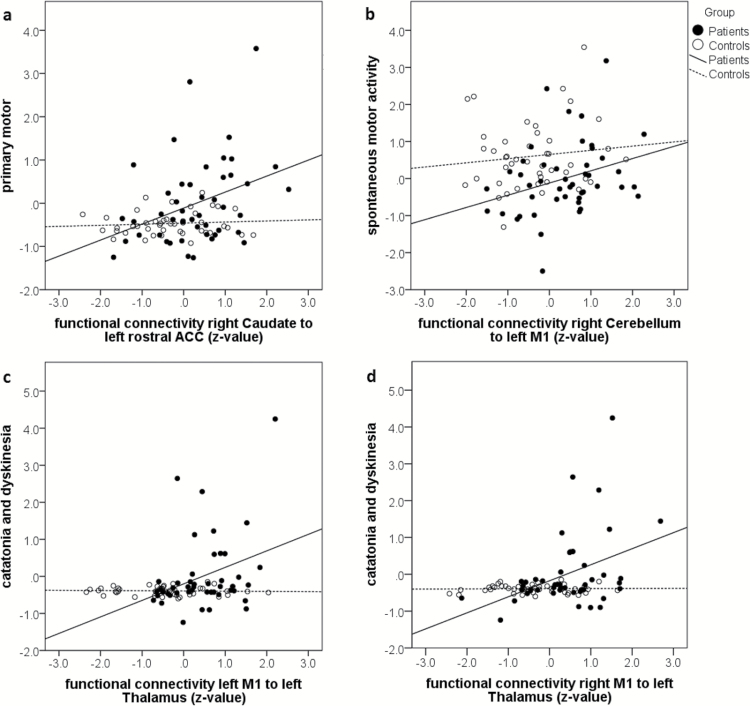

For the 18 connections with between-group differences, we explored whether connectivity values correlated with the 4 motor factors for each group separately (table 3). The primary motor factor correlated in healthy controls with connectivity between left DLPFC and right STN, as well as inversely between right M1 and right cerebellum. Thus, increased connectivity was found in subjects with low scores. In patients the primary motor factor correlated with connectivity between left rostral ACC and right caudate (figure 2). The factor catatonia and dyskinesia correlated positively in controls with connectivity between right M1 and left cerebellum, in patients with thalamocortical connectivity from bilateral M1 to left thalamus (figure 2). The coordination factor only correlated in healthy controls with ipsilateral connectivity between left SMA and left cerebellum. Finally, spontaneous motor activity correlated in controls with connectivity between left rostral ACC and right STN and in patients with connectivity between left M1 and right cerebellum. The associations in patients were similar when testing the 4 motor rating scales (supplementary table S4), most correlations were found for the connection between left rACC and right caudate. Controlling the correlations for the mean CPZ of the past 5 years in patients confirmed most results (supplementary table S3).

Table 3.

Exploratory Correlations of Motor Behavior Factors and Functional Connectivity

| Primary Motor | Catatonia and Dyskinesia | Coordination | Spontaneous Motor Activity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | SZ | HC | SZ | HC | SZ | HC | SZ | |

| lDLPFC-rSTN | .32* | .13 | −.03 | .03 | −.01 | −.06 | .11 | .19 |

| lDLPFC-rrACC | .19 | .13 | −.07 | .11 | .09 | .09 | .16 | .17 |

| rDLPFC-lrACC | .05 | .10 | −.03 | .22 | .11 | −.03 | .09 | .21 |

| lrACC-rSTN | .16 | .09 | −.06 | .10 | −.01 | −.06 | .33* | .16 |

| lrACC-rCaud | .09 | .35* | −.07 | .11 | .12 | .14 | .06 | .07 |

| ldACC-lSTN | −.17 | .01 | −.01 | .12 | .19 | −.04 | −.18 | .19 |

| lpreSMA-rCaud | .01 | −.26 | −.01 | .26 | .08 | −.10 | .01 | .18 |

| lSMA-lCerebell | −.15 | .05 | −.20 | −.05 | .31* | −.05 | −.26 | .11 |

| rSMA-lCerebell- | −.14 | .10 | .03 | .02 | .16 | .22 | −.16 | .17 |

| rSMA-rCerebell | −.26 | .06 | .02 | −.05 | .17 | .09 | −.17 | .14 |

| lM1-lCerebell | −.17 | −.01 | .08 | .17 | .07 | −.17 | .02 | .11 |

| lM1-lThal | −.13 | −.10 | −.06 | .33* | .13 | −.11 | .04 | −.02 |

| lM1-rCerebell | −.29 | −.04 | .22 | .20 | −.13 | −.23 | .12 | .30* |

| rM1-rCerebell | −.32* | .07 | .22 | .10 | −.03 | −.28 | .09 | .28 |

| rM1-lThal | −.10 | −.01 | .03 | .39** | .13 | −.07 | .04 | −.01 |

| rM1-lCerebell | −.15 | .03 | .34* | .15 | −.21 | −.24 | .11 | .26 |

| lThal-lPut | −.01 | .11 | −.06 | −.02 | .03 | .01 | −.07 | −.05 |

| lPut-rCerebell | .11 | −.27 | −.07 | .18 | −.11 | −.22 | .08 | .21 |

Note: DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; rACC, rostral anterior cingulate cortex; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; SMA, supplementary motor area; M1, primary motor cortex; caud, caudate; put, putamen; STN, subthalamic nucleus; SZ, schizophrenia; HC, healthy controls.

*P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .001.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between motor factors and connectivity.

Discussion

In order to investigate whether motor abnormalities in schizophrenia spectrum disorders were linked to aberrant function of the cerebral motor system, we tested resting state functional connectivity between patients and matched healthy controls. In line with our hypotheses, 2 main findings emerged: First, the analysis of resting state functional connectivity within the motor system identified a number of connections, in which patients differed from controls mainly with increased functional connectivity. This was particularly evident in associations between M1 or SMA with thalamus and cerebellum. Furthermore, prefrontal ROIs were strongly connected to the bilateral STN. Second, some of the connections with altered functional connectivity were associated with distinct domains of motor abnormalities. For example, the catatonia and dyskinesia factor was correlated with thalamocortical connectivity in patients. Together, these findings suggest that a dysregulated motor network in schizophrenia as evidenced by altered resting state functional connectivity was clearly associated with motor abnormalities at the behavioral level.

The PCA of the motor behavior battery in patients indicated 4 separate factors collectively explaining 81% of the variance. As in previous studies, a factor combining different hypokinetic motor abnormalities such as parkinsonism, catatonia, and neurological soft signs explained a considerable proportion of variance.7–10 The other 3 factors were dyskinesia and catatonia, coordination, and spontaneous motor activity. The latter factor exclusively consisted of the objective instrumental measure activity level, which was not part of the other 3 factors. Thus, spontaneous motor activity appears to be a separate measure distinct from classical clinical rating scales, which struggle with conceptual overlap.1 Given, that the motor behavior domain would be included in the RDoC initiative,64 such instrumental measures of spontaneous motor activity could become one of the objective assessment methods. However, until valid instrumentation is available for all aspects of motor behavior, the use of classical rating scales is still advocated despite issues such as interrater reliability and conceptual overlap.

Our resting state fMRI findings are in line with previous reports demonstrating increased functional connectivity between motor cortices and thalamus in schizophrenia36–38,65 and in subjects at clinical high risk for psychosis.39 Our findings also parallel those who reported aberrant resting state functional connectivity between motor areas of the cerebellum and frontal cortex.40,66 Furthermore, cerebellar hyperconnectivity to the motor cortex may even predict future deterioration of positive symptoms in subjects at high risk for psychosis.67 The connections between cerebellum and premotor/prefrontal cortex are suggested to contribute to movement inhibition.68 Indeed, the cerebellum selectively exerts inhibitory activity on both basal ganglia and M1, enabling targeted movement control.69

However, this is the first study demonstrating abnormal functional connectivity to the STN, which is a major relay for inhibitory control in the basal ganglia circuitry.70 STN via internal pallidum exerts inhibitory control over thalamo-cortical projections. In addition to the inputs from the external pallidum, the STN receives cortical input from premotor and prefrontal cortices via the so-called hyperdirect pathway.71–73 STN pathology is central in Parkinson’s Disease and stronger coupling within the hyperdirect pathway is associated with increased symptom severity, eg, rigor and bradykinesia.72–74 Finally, deep brain stimulation to the STN reduces functional connectivity in all STN projections but at the same time increases thalamocortical and putamen-thalamus connectivity, which then ameliorates parkinsonian motor signs.72

STN is not only inhibitory, but also important for action selection in situations of conflicts.75 The STN has topographical subdivisions but at the same time considerable overlap between motor, associative and limbic circuits has been noted.76 We found increased functional connectivity in schizophrenia between STN and DLPFC, rACC and dACC, paralleling findings in Parkinson’s Disease. This would argue for net increased inhibitory action in psychosis. Together, our findings support a strong influence of altered STN connections on the schizophrenia motor system. Whether these inputs reflect solely increased tonic inhibitory activity or particular problems in action selection,77 remains to be determined.

The results of the current study extend previous work by demonstrating that aberrant functional connectivity in the motor system could be linked to motor abnormalities in schizophrenia. We correlated functional connectivity with motor factor scores, which were derived from a PCA in the patients’ motor behavior data. The correlations remain exploratory and would not survive rigorous correction for multiple comparisons. But these associations are still very informative. Furthermore, correlations are still valid when correcting for average CPZ of the past 5 years (supplementary table S3). For instance, the catatonia factor was correlated with functional connectivity between left thalamus and bilateral M1. Thus, higher connectivity indicated more severe catatonic symptoms. The connection between thalamus and M1 is one of the most critical associations within the motor system as it constitutes the output of the basal ganglia loop to the motor cortex. Connections between thalamus and M1 are thought to have facilitatory effects on motor output.78 Converging evidence suggests that this critical connection is altered in schizophrenia. For instance, a diffusion tensor imaging study (DTI) indicated increased structural connectivity of the thalamus-M1 connection in schizophrenia.25 But while structural connectivity was increased in patients, it was not associated with motor behavior. Likewise, resting state perfusion of the anterior thalamus correlated with spontaneous motor behavior in controls, but not in patients.17 The connection between thalamus and M1 combines various information including cortical input to the thalamic nuclei and thalamic efferents to the cortex, which may either contain information sent from the cerebellum or information from the basal ganglia output.79 Likewise, we cannot infer the direction of information flow or the consequences on motor output (facilitation or inhibition) from the analysis of resting state connectivity data. However, the correlations with motor behavior suggest that increased functional connectivity at rest was associated with motor inhibition.

Furthermore, we found that spontaneous motor activity correlated with connectivity between M1 and cerebellum in patients, with stronger connectivity indicating more movement. This is in line with the notion of inefficient basal ganglia output in schizophrenia, which was associated with lower motor activity.17,25 In times of increased inhibitory tone on the motor output via basal ganglia, the cerebellar contribution may be relevant to overcome motor inhibition. Indeed, cerebellum and basal ganglia are interconnected in 2 ways: via thalamic nuclei and directly via STN.80 A recent task based functional connectivity study indicated that with increasing speed of hand movements connectivity increases between the ipsilateral cerebellum and contralateral M1.81 Likewise, selective inhibition of cortical representations of surround muscles from the cerebellum may facilitate movement in the target muscle.69 Thus, our result of increased functional connectivity between right cerebellum and left M1 in patients with higher spontaneous motor activity fits quite well to these data. Relatedly, our findings are also in line with a study in subjects at risk for psychosis, in which reduced cerebellar-cortical connectivity at rest was associated with poor motor coordination, ie, increased postural sway.40

The correlations between functional connectivity and motor behavior critically depend on the severity of motor abnormalities in schizophrenia. The range of motor abnormalities and activity levels corresponds well to previous reports in schizophrenia.8,26,82,83 It is also important to note that previous studies in catatonia suggest prefrontal hypoactivation and reduced task-based connectivity between ventromedial prefrontal cortex and motor cortices.84,85 These associations were not tested in the current approach exclusively focusing on connectivity within the motor system. However, seed-to-voxel analyses found increased connectivity from motor system seeds to various non-motor brain regions including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (supplementary table S6).

Our results further support the notion that motor abnormalities are a key feature of schizophrenia.1,64 In addition, the current study provides further evidence for neural dysconnectivity, particularly within the cerebral motor system.11,36,38 Finally, exploratory correlations suggest that altered resting state connectivity within the motor system may be associated with behavioral motor abnormalities in schizophrenia. Longitudinal studies are required to test (1) whether alterations within the motor system are subject to change along with improvement of other symptoms and (2) whether functional alterations within the motor system in subjects at psychosis risk would predict later occurrence of motor abnormalities. Given that altered resting state connectivity would indicate a motor network dysfunction, we may speculate that dysconnectivity would not only be limited to the resting state but also impair network output during experimental tasks or real world function. As some of the key cortical motor areas are located just underneath the cranium, they might serve as entry nodes of noninvasive brain modulation; thus, the dysfunctional motor network in schizophrenia could be tackled with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS).

Limitations

The study of functional connectivity at rest remains descriptive. However, it may serve as an index of altered function within brain systems in neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia. Here, we chose predefined ROIs of the cerebral motor system. With this selection we may have missed other contributing brain areas, because we exclusively focused on ROI-to-ROI connectivity. However, the hypothesis driven approach of our study required some selection. When we performed an additional seed-to-voxel connectivity analysis (supplementary table S6), our results were clearly in line with previous reports, particularly in terms of thalamo-cortical or cerebellar-cortical connectivity.36,38,40 We applied a validated neuroanatomical atlas to identify the ROIs, however, some of the smaller ROIs are hard to locate at 3T field strength introducing a small risk of bias. Furthermore, as the majority of patients were currently treated with second generation antipsychotics for an average of 11 years, we cannot rule out possible effects of medication on the findings of altered functional connectivity. Still, the limited evidence available argues for an attenuation of dysconnectivity by antipsychotic drugs.86–88 Likewise, acute administration of 1 mg/kg haloperidol in rats decreased functional connectivity to the motor cortex.89 Antipsychotic drugs may also impact motor abnormalities resulting in deterioration or amelioration of preexisting signs or also induce motor side effects.90 The correlations between motor factor scores and functional connectivity in our study remained the same after correction for 5-year CPZ values (supplementary table S3). Finally, the correlation between motor factor scores and functional connectivity must be interpreted with caution. These exploratory analyses would not survive rigorous correction for multiple comparisons. Still, the results fit to previous reports with other neuroimaging techniques, such as diffusion tensor imaging and arterial spin labeling.17,26,33

Conclusions

Resting state functional connectivity indicated aberrant tonic activity in the motor system of schizophrenia patients. Hyperconnectivity was noted in 3 groups of connections with predominantly inhibitory activity. Particularly thalamocortical hyperconnectivity was associated with motor abnormalities in patients. Together, our findings suggest that the observed alterations at rest may drive the reduced motor behavior typically observed in schizophrenia.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at Schizophrenia Bulletin online.

Funding

Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation (to S.W.); Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF grant 152619 to S.W., A.F., and S.B.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Walther S, Strik W. Motor symptoms and schizophrenia. Neuropsychobiology. 2012;66:77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koning JP, Tenback DE, van Os J, Aleman A, Kahn RS, van Harten PN. Dyskinesia and parkinsonism in antipsychotic-naive patients with schizophrenia, first-degree relatives and healthy controls: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:723–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kindler J, Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C et al. Abnormal involuntary movements are linked to psychosis-risk in children and adolescents: results of a population-based study. Schizophr Res. 2016;174:58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mittal VA, Orr JM, Turner JA et al. Striatal abnormalities and spontaneous dyskinesias in non-clinical psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2013;151:141–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bachmann S, Bottmer C, Schroder J. Neurological soft signs in first-episode schizophrenia: a follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:2337–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cuesta MJ, Sanchez-Torres AM, de Jalon EG et al. Spontaneous parkinsonism is associated with cognitive impairment in antipsychotic-naive patients with first-episode psychosis: a 6-month follow-up study. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:1164–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McKenna PJ, Lund CE, Mortimer AM, Biggins CA. Motor, volitional and behavioural disorders in schizophrenia. 2: The ‘conflict of paradigms’ hypothesis. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peralta V, Campos MS, De Jalon EG, Cuesta MJ. Motor behavior abnormalities in drug-naive patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Mov Disord. 2010;25:1068–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. Motor features in psychotic disorders. I. Factor structure and clinical correlates. Schizophr Res. 2001;47:107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Docx L, Morrens M, Bervoets C et al. Parsing the components of the psychomotor syndrome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126:256–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Walther S. Psychomotor symptoms of schizophrenia map on the cerebral motor circuit. Psychiatry Res. 2015;233:293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Douaud G, Smith S, Jenkinson M et al. Anatomically related grey and white matter abnormalities in adolescent-onset schizophrenia. Brain. 2007;130:2375–2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haijma SV, Van Haren N, Cahn W, Koolschijn PC, Hulshoff Pol HE, Kahn RS. Brain volumes in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis in over 18 000 subjects. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:1129–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schneiderman JS, Hazlett EA, Chu KW et al. Brodmann area analysis of white matter anisotropy and age in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;130:57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ellison-Wright I, Nathan PJ, Bullmore ET et al. Distribution of tract deficits in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu J, Qiu M, Constable RT, Wexler BE. Does baseline cerebral blood flow affect task-related blood oxygenation level dependent response in schizophrenia? Schizophr Res. 2012;140:143–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walther S, Federspiel A, Horn H et al. Resting state cerebral blood flow and objective motor activity reveal basal ganglia dysfunction in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2011;192:117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pinkham A, Loughead J, Ruparel K et al. Resting quantitative cerebral blood flow in schizophrenia measured by pulsed arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI. Psychiatry Res. 2011;194:64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pinkham AE, Liu P, Lu H, Kriegsman M, Simpson C, Tamminga C. Amygdala hyperactivity at rest in paranoid individuals with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:784–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kindler J, Schultze-Lutter F, Hauf M et al. Increased striatal and reduced prefrontal cerebral blood flow in clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Bull. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stegmayer K, Strik W, Federspiel A, Wiest R, Bohlhalter S, Walther S. Specific cerebral perfusion patterns in three schizophrenia symptom dimensions [published online ahead of print March 17, 2017]. Schizophr Res. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bernard JA, Mittal VA. Dysfunctional activation of the cerebellum in schizophrenia: a functional neuroimaging meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Sci. 2015;3:545–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bernard JA, Russell CE, Newberry RE, Goen JR, Mittal VA. Patients with schizophrenia show aberrant patterns of basal ganglia activation: evidence from ALE meta-analysis. NeuroImage Clinical. 2017;14:450–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Viher PV, Stegmayer K, Giezendanner S et al. Cerebral white matter structure is associated with DSM-5 schizophrenia symptom dimensions. NeuroImage Clinical. 2016;12:93–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bracht T, Schnell S, Federspiel A et al. Altered cortico-basal ganglia motor pathways reflect reduced volitional motor activity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2013;143:269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walther S, Federspiel A, Horn H et al. Alterations of white matter integrity related to motor activity in schizophrenia. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42:276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bai YM, Chou KH, Lin CP et al. White matter abnormalities in schizophrenia patients with tardive dyskinesia: a diffusion tensor image study. Schizophr Res. 2009;109:167–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Docx L, Emsell L, Van Hecke W et al. White matter microstructure and volitional motor activity in schizophrenia: a diffusion kurtosis imaging study. Psychiatry Res 2016;260:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hirjak D, Wolf RC, Stieltjes B et al. Cortical signature of neurological soft signs in recent onset schizophrenia. Brain Topography. 2014;27:296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stegmayer K, Horn H, Federspiel A et al. Supplementary motor area (SMA) volume is associated with psychotic aberrant motor behaviour of patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2014;223:49–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dazzan P, Morgan KD, Orr KG et al. The structural brain correlates of neurological soft signs in AESOP first-episode psychoses study. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 1):143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hirjak D, Wolf RC, Stieltjes B, Seidl U, Schroder J, Thomann PA. Neurological soft signs and subcortical brain morphology in recent onset schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 2012;46:533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Walther S, Schappi L, Federspiel A et al. Resting-state hyperperfusion of the supplementary motor area in catatonia. Schizophr Bull. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao Q, Li Z, Huang J et al. Neurological soft signs are not “soft” in brain structure and functional networks: evidence from ALE meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:626–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scheuerecker J, Ufer S, Kapernick M et al. Cerebral network deficits in post-acute catatonic schizophrenic patients measured by fMRI. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Anticevic A, Cole MW, Repovs G et al. Characterizing thalamo-cortical disturbances in schizophrenia and bipolar illness. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24:3116–3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klingner CM, Langbein K, Dietzek M et al. Thalamocortical connectivity during resting state in schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264:111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Woodward ND, Karbasforoushan H, Heckers S. Thalamocortical dysconnectivity in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1092–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Anticevic A, Haut K, Murray JD et al. Association of thalamic dysconnectivity and conversion to psychosis in youth and young adults at elevated clinical risk. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:882–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bernard JA, Dean DJ, Kent JS et al. Cerebellar networks in individuals at ultra high-risk of psychosis: impact on postural sway and symptom severity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35:4064–4078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kaufmann T, Skatun KC, Alnaes D et al. Disintegration of sensorimotor brain networks in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:1326–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Berman RA, Gotts SJ, McAdams HM et al. Disrupted sensorimotor and social-cognitive networks underlie symptoms in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 1):276–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–33;quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Arndt S. The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH). An instrument for assessing diagnosis and psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:615–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brown L, Sherbenou RJ, Johnsen SK.. Test of Nonverbal Intelligence. Austin, TX: PRO-ED; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, Dowling F, Francis A. Catatonia. I. Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lund CE, Mortimer AM, Rogers D, McKenna PJ. Motor, volitional and behavioural disorders in schizophrenia. 1: Assessment using the Modified Rogers Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1991;158:323–327, 333-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fahn S, Elton RL, Members UP. Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. In: Fahn S, Marsden CD, Goldstein M, Calne DB, eds. Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease. Vol 2 Florham Park, NJ: Macmillan Healthcare Information; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education and Welfare; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Buchanan RW, Heinrichs DW. The Neurological Evaluation Scale (NES): a structured instrument for the assessment of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1989;27:335–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Walther S, Koschorke P, Horn H, Strik W. Objectively measured motor activity in schizophrenia challenges the validity of expert ratings. Psychiatry Res. 2009;169:187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Deichmann R, Schwarzbauer C, Turner R. Optimisation of the 3D MDEFT sequence for anatomical brain imaging: technical implications at 1.5 and 3 T. Neuroimage. 2004;21:757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Nieto-Castanon A. Conn: a functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect. 2012;2:125–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage. 2012;59:2142–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Haber SN, Behrens TE. The neural network underlying incentive-based learning: implications for interpreting circuit disruptions in psychiatric disorders. Neuron. 2014;83:1019–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Haber SN. Corticostriatal circuitry. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016;18:7–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stoodley CJ, Schmahmann JD. Functional topography in the human cerebellum: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage. 2009;44:489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. O’Reilly JX, Beckmann CF, Tomassini V, Ramnani N, Johansen-Berg H. Distinct and overlapping functional zones in the cerebellum defined by resting state functional connectivity. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:953–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nieuwenhuys R, Voogd J, van Huijzen C. The Human Central Nervous System. 4th ed. Heidelberg, Germany: Steinkopff; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vogt BA. Regions and subregions of the cingulate cortex. In: Vogt BA, ed. Cingulate Neurobiology and Disease. Vol 1 New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Habas C. Functional connectivity of the human rostral and caudal cingulate motor areas in the brain resting state at 3T. Neuroradiology. 2010;52:47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bernard JA, Mittal VA. Updating the research domain criteria: the utility of a motor dimension. Psychol Med. 2015;45:2685–2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cheng W, Palaniyappan L, Li M et al. Voxel-based, brain-wide association study of aberrant functional connectivity in schizophrenia implicates thalamocortical circuitry. NPJ Schizophr. 2015;1:15016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Chen YL, Tu PC, Lee YC, Chen YS, Li CT, Su TP. Resting-state fMRI mapping of cerebellar functional dysconnections involving multiple large-scale networks in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2013;149:26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bernard JA, Orr JM, Mittal VA. Cerebello-thalamo-cortical networks predict positive symptom progression in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis. NeuroImage Clinical. 2017;14:622–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Picazio S, Koch G. Is motor inhibition mediated by cerebello-cortical interactions? Cerebellum. 2015;14:47–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Panyakaew P, Cho HJ, Srivanitchapoom P, Popa T, Wu T, Hallett M. Cerebellar brain inhibition in the target and surround muscles during voluntary tonic activation. Eur J Neurosci. 2016;43:1075–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zavala B, Zaghloul K, Brown P. The subthalamic nucleus, oscillations, and conflict. Mov Disord. 2015;30:328–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hamani C, Saint-Cyr JA, Fraser J, Kaplitt M, Lozano AM. The subthalamic nucleus in the context of movement disorders. Brain. 2004;127:4–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kahan J, Urner M, Moran R et al. Resting state functional MRI in Parkinson’s disease: the impact of deep brain stimulation on ‘effective’ connectivity. Brain 2014;137:1130–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kurani AS, Seidler RD, Burciu RG et al. Subthalamic nucleus--sensorimotor cortex functional connectivity in de novo and moderate Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Baudrexel S, Witte T, Seifried C et al. Resting state fMRI reveals increased subthalamic nucleus-motor cortex connectivity in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroimage. 2011;55:1728–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Herz DM, Christensen MS, Bruggemann N et al. Motivational tuning of fronto-subthalamic connectivity facilitates control of action impulses. J Neurosci. 2014;34:3210–3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Alkemade A, Schnitzler A, Forstmann BU. Topographic organization of the human and non-human primate subthalamic nucleus. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220:3075–3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Barbalat G, Chambon V, Domenech PJ et al. Impaired hierarchical control within the lateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Groenewegen HJ. The basal ganglia and motor control. Neural Plast. 2003;10:107–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Oguri T, Sawamoto N, Tabu H et al. Overlapping connections within the motor cortico-basal ganglia circuit: fMRI-tractography analysis. Neuroimage. 2013;78:353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bostan AC, Dum RP, Strick PL. The basal ganglia communicate with the cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8452–8456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Pool EM, Rehme AK, Fink GR, Eickhoff SB, Grefkes C. Network dynamics engaged in the modulation of motor behavior in healthy subjects. Neuroimage. 2013;82:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Docx L, Sabbe B, Provinciael P, Merckx N, Morrens M. Quantitative psychomotor dysfunction in schizophrenia: a loss of drive, impaired movement execution or both? Neuropsychobiology. 2013;68:221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wilson JE, Niu K, Nicolson SE, Levine SZ, Heckers S. The diagnostic criteria and structure of catatonia. Schizophr Res. 2015;164:256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Northoff G, Kotter R, Baumgart F et al. Orbitofrontal cortical dysfunction in akinetic catatonia: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study during negative emotional stimulation. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:405–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Northoff G, Steinke R, Nagel DC et al. Right lower prefronto-parietal cortical dysfunction in akinetic catatonia: a combined study of neuropsychology and regional cerebral blood flow. Psychol Med. 2000;30:583–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kraguljac NV, White DM, Hadley JA et al. Abnormalities in large scale functional networks in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia and effects of risperidone. NeuroImage Clinical. 2016;10:146–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Sarpal DK, Robinson DG, Lencz T et al. Antipsychotic treatment and functional connectivity of the striatum in first-episode schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hutcheson NL, Sreenivasan KR, Deshpande G et al. Effective connectivity during episodic memory retrieval in schizophrenia participants before and after antipsychotic medication. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:1442–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Gass N, Schwarz AJ, Sartorius A et al. Haloperidol modulates midbrain-prefrontal functional connectivity in the rat brain. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:1310–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. The effect of antipsychotic medication on neuromotor abnormalities in neuroleptic-naive nonaffective psychotic patients: a naturalistic study with haloperidol, risperidone, or olanzapine. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12. doi:10.4088/PCC.09m00799gry [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.