Abstract

Dysregulation of the MAPK pathway correlates with progression of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) progression. IQ motif containing GTPase-activating protein 1 (IQGAP1) is a MAPK scaffold that directly regulates the activation of RAF, MEK, and ERK. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP1), a key enzyme in gluconeogenesis, is transcriptionally downregulated in various cancers, including PDAC. Here, we demonstrate that FBP1 acts as a negative modulator of the IQGAP1–MAPK signaling axis in PDAC cells. FBP1 binding to the WW domain of IQGAP1 impeded IQGAP1-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation (pERK1/2) in a manner independent of FBP1 enzymatic activity. Conversely, decreased FBP1 expression induced pERK1/2 levels in PDAC cell lines and correlated with increased pERK1/2 levels in patient specimens. Treatment with gemcitabine caused undesirable activation of ERK1/2 in PDAC cells, but cotreatment with the FBP1-derived small peptide inhibitor FBP1 E4 overcame gemcitabine-induced ERK activation, thereby increasing the anticancer efficacy of gemcitabine in PDAC. These findings identify a primary mechanism of resistance of PDAC to standard therapy and suggest that the FBP1–IQGAP1–ERK1/2 signaling axis can be targeted for effective treatment of PDAC.

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the leading causes of cancer-related death worldwide (1). It is estimated that more than 330,000 people are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer annually (2). Despite its relatively low epidemiologic ranking, PDAC is notorious for its ability to evade early diagnosis and high capability to invade and metastasize. The prognosis of PDAC remains poor, and the occurrence and death rate of this disease remain largely unchanged after decades of studies (3). Although many therapeutic agents, such as gemcitabine and nabpaclitaxel, have been developed for pancreatic cancer treatment, PDAC is generally insensitive to both chemo- and radiotherapy. Therefore, there is an urgent medical need to develop novel therapeutics for pancreatic cancer treatment.

Activation mutations in RAS are very common, with the frequency as high as 90% in PDAC (4). Dysregulation of MAPK pathway correlates with progression of PDAC. Increased ERK phosphorylation has been frequently detected in PDAC (5). The scaffold protein IQ-domain GTPase-activating protein 1 (IQGAP1) contains multiple protein-interacting domains and participates in multiple cellular functions, such as cell polarization and directional migration, adhesion, growth, and transformation. IQGAP1 overexpression is highly correlated with pancreatic cancer cell metastasis. Particularly, IQGAP1 functions as a key scaffold for the MAPK pathway by directly binding to and modulating the activities of RAF, MEK, and ERK (6, 7). Importantly, it has been shown previously that IQGAP1 is required in RAS-driven tumorigenesis in mouse and human tissues. ERK1/2 bind to the WW domain of IQGAP. A peptide derived from the WW domain disrupts the interaction of IQGAP1–ERK1/2 and inhibits pancreas tumorigenesis (8). The scaffold–kinase interaction represents a promising therapeutic target to treat pancreatic cancer.

Expression of FBP1 is downregulated in various types of cancer, including breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, renal carcinoma, lung cancer, among others (9–13). FBP1 acts as a tumor suppressor, and downregulation of FBP1 is associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic carcinoma. It has been reported that FBP1 suppresses tumor progression mainly by inhibition of the Warburg effect (10). Further studies show that it also suppresses renal carcinoma cell growth by inhibiting the function of transcription factor HIF1α (12). In the current study, we identified a novel role of FBP1 in inhibition of tumor progression. We demonstrated that FBP1 inhibits the activity of ERK1/2 in a manner independent of its enzymatic activity. We further showed that binding to the WW domain of IQGAP1 enables FBP1 to inhibit the IQGAP1–ERK1/2 interaction, IQGAP1-dependent activation of ERK1/2, and growth and chemoresistance of PDAC cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines, cell culture, and transfection

The pancreatic cancer cell lines PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 were obtained from Dr. D.D. Billadeau at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN) in 2015 and authenticated via STR profiling in 2017 (IDEXX BioResearch). These cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were cultured at 37°C supplied with 5% CO2. Mycoplasma contamination was regularly examined using Lookout Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Plasmocin (InvivoGen) was routinely added to the cell culture medium to prevent or eliminate mycoplasma contamination. Transfections were performed by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Approximately 75% to 95% transfection efficiencies were routinely achieved.

Tandem affinity purification

293T cells were transfected with SFB-tagged FBP1 or empty vector. Twenty-four hours post transfection, cells were lysed by NETN buffer (20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 50 mmol/L β-glycerophosphate, 10 mmol/L NaF, and 1 μg/mL pepstatin A) at 4°C for 3 hours. The supernatant was collected for incubation with streptavidin sepharose beads (GE Healthcare Sciences) at 4°C overnight. The next day, the beads were washed with NETN buffer for five times and then eluted by 2 mmol/L biotin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour at 4°C twice. The elution products were incubated with S-protein agarose beads (Novagen) at 4°C overnight, and after washing three times, the products bound to S-protein agarose beads were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by silver staining and mass spectrometry.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Cells were harvested and lysed by IP buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 1% protease inhibitor cocktails) on ice for more than 15 minutes. Cell lysate was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 13,000 rpm at 4°C, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube. The supernatant was incubated with primary antibodies and protein A/G agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with gentle rocking at 4°C overnight. The next day, the pellet was washed six times with 1× IP buffer on ice and then subjected to Western blotting.

Glutathione S-transferase pull-down assay

Cells were lysed with cell lysis buffer [20 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P40, 1 mmol/L DTT (dithiothreitol), 10% glycerol, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 2.5 mmol/L MgCl2, and 1 μg/mL leupeptin] for 30 minutes at 4°C. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins were immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). After washing with lysis buffer, the beads were incubated with cell lysates for 4 hours. The beads were then washed four times with binding buffer and resuspended in sample buffer. The bound proteins were subjected to SDS/PAGE and Western blotting.

Western blotting

Cells were harvested and lysed by cell lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 1% protease inhibitor cocktails) on ice for more than 15 minutes. Cell lysate was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 13,000 rpm at 4°C, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube for BCA protein quantification assay. Equal amounts of protein sample were added into 4× sample buffer and boiled for 5 minutes. The sample was subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked by 5% milk for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The membrane was washed six times with 1× TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. The protein was visualized by SuperSignal West Pico Stable Peroxide Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

RNAi

Lentivirus-based control and gene-specific small hairpin RNAs (shRNA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Lipofectamine2000 was used to transfect 293T cells with shRNA plasmid and viral packaging plasmids (pVSV-G and pEXQV). Twenty-four hours posttransfection, medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS with 1:100 of sodium pyruvate. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, virus culture medium was collected and added to PANC-1 or MIA PaCa-2 cells treated with 12 μg/mL of polybrene. PANC-1 or MIA PaCa-2 cells were harvested 48 hours after virus infection and puromycin selection. shRNA sequence information is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Cell infection with lentiviral expression vectors

The pTsin lentiviral expression vector was used to generate lentiviral plasmids for pTsin-SFB-FFBP1 wild type (WT), pTsin-SFB-FBP1 G260R, and pTsin-SFB-FBP1 E4. shRNA-resistant expression vector for pTsin-SFB-FBP1 WT or mutants were generated using the KOD-Plus Mutagenesis Kit (Toyobo). Lipofectamine 2000 was used to transfect 293T cells with pTsin expression plasmid and viral packaging plasmids (pHR’ CMV δ 9.8 and pVSV-G). Twenty-four hours after transfection, medium in 293T cells was replaced with fresh DMEM containing 10% serum plus 1:100 sodium pyruvate. Twenty-four hours after sodium pyruvate treatment, cell culture medium was collected and added to PANC-1 or MIA PaCa-2 cells, followed by treatment with 12 μg/mL of polybrene. Stable cell lines were selected using puromycin.

MTS assay

Cell viability was measured using the MTS assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates with 100 μL of culture medium. Each well was added with 20 μL of CellTiter 96R AQueous One Solution Reagent (Promega), and absorbance was measured in a microplate reader at 490 nm.

Glucose consumption and lactate production measurement assay

Cells were plated in 6-well plates and cultured in DMEM medium without phenol red (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Twenty-four hours after plasmid transfection or 48 hours after lentivirus infection, the spent medium was collected. Glucose concentration of the spent medium was measured using a Glucose (GO) Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich). Glucose consumption was the difference of glucose concentration between the spent medium and unused medium. Lactate levels were measured using a Lactate Assay Kit (Eton Bioscience). The glucose consumption and lactate generation were normalized to cell numbers.

Detection of apoptosis using Annexin V assay and flow cytometry

Cells were washed twice with PBS and resuspended in 1× Binding Buffer. Cells (1 × 105) were stained with PE Annexin V and 7-amino-actinomycin following the manufacturer’s instructions of PE Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences). Cells were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature and analyzed on a flow cytometer. Data were analyzed with FlowJo analysis software.

Pancreatic cancer patient specimens, tissue microarray, IHC, and staining scoring

Pancreatic cancer tissue microarrays (TMA) were purchased from US Biomax, Inc. (cat. # HPan-Ade150CS-01). TMA specimens were immunostained with FBP1 and pERK1/2 antibodies as described previously (14, 15). Staining intensity was graded/scored in a blinded fashion: 1 = weak staining at ×100 magnification but little or no staining at ×40 magnification; 2 = medium staining at ×40 magnification; 3 = strong staining at ×40 magnification. A final staining index was calculated using the formula: staining intensity × percentage.

Generation of pancreatic cancer xenografts in mice

Six-week-old NOD/SCID IL2-receptor gamma null (NSG) mice were generated in-house and used for animal experiments. The animal study was approved by the IACUC at Mayo Clinic. All mice were housed in standard conditions with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and access to food and water ad libitum. MIA PaCa-2 cells (5 × 106) infected with lentivirus [in 100 μL 1× PBS plus 100 μL Matrigel (BD Biosciences)] were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of mice. The volume of xenografts was measured every other day for 21 days and calculated using the formula L × W2 × 0.5. Upon the completion of measurement, tumor grafts were harvested.

Statistical analysis

All values were expressed as means ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed with Student t test unless otherwise indicated. P values <0.05 are considered statistically significant. Pearson product–moment correlation was used to calculate the correlation between FBP1 and pERK1/2 staining index in PDAC TMAs.

Additional methods

Other detailed methods are described in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Results

FBP1 binds to the scaffold protein IQGAP1

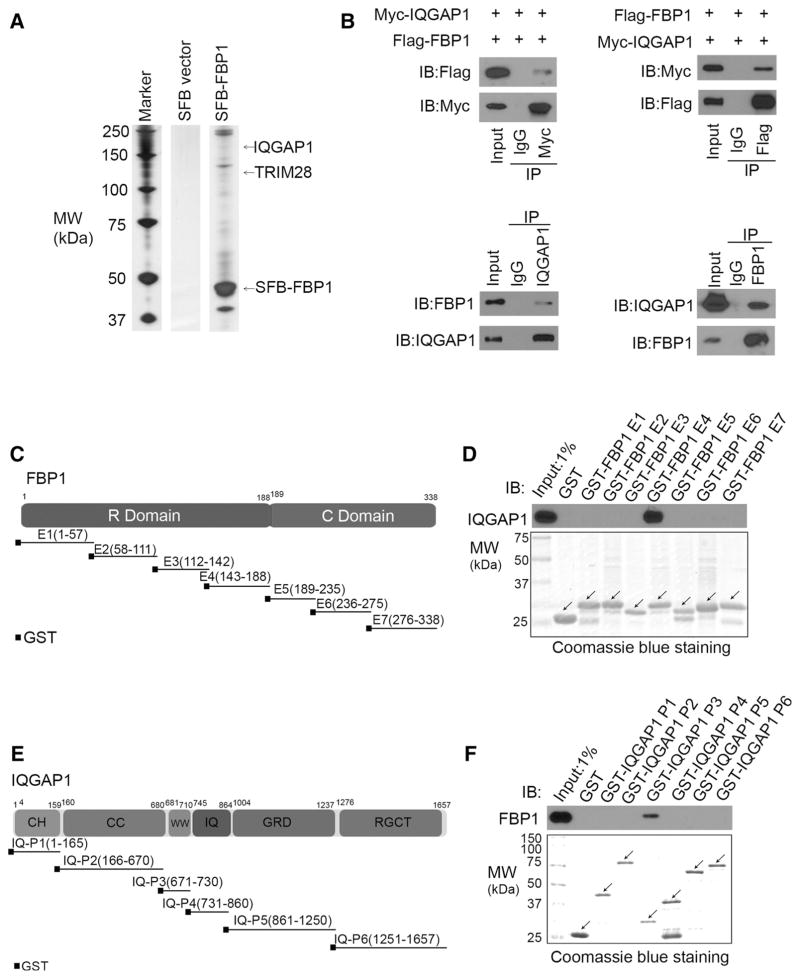

To search for novel functions of FBP1, we constructed a FBP1 mammalian expression vector (SFB-FBP1), which contains S, Flag, and Biotin-binding-protein-(streptavidin)-binding-peptide tags. This plasmid and the backbone vector were individually transfected into 293T cells, and cell extracts were prepared for tandem affinity protein purification and mass spectrometry. A number of binding partners of FBP1, including IQGAP1, were identified (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Table S2; ref. 16). Given that IQGAP1 is a scaffold protein that plays an important role in activation of the RAF–MEK–ERK pathway and tumorigenesis in PDAC (8, 17), we were interested in exploring the molecular basis and biological impact of the interaction between FBP1 and IQGAP1 in PDAC.

Figure 1.

FBP1 binds to the scaffold protein IQGAP1. A, SDS-PAGE and silver staining of proteins purified by tandem affinity protein purification in 293T cells transiently transfected with SFB control vector or SFB-tagged FBP1. B, Western blot analysis of ectopically expressed Flag-FBP1 and Myc-IQGAP1 reciprocally immunoprecipitated by anti-Myc and anti-Flag in 293T cells, and endogenous FBP1 and IQGAP1 proteins reciprocally immunoprecipitated by anti-IQGAP1 and anti-FBP1 in PANC-1 cells. Immunoblots (IB) are representative of results from two independent experiments (n = 2). C, Schematic diagram depicting a set of GST-FBP1 recombinant protein constructs. D, Western blot analysis of IQGAP1 proteins in PANC-1 whole cell lysate pulled down by GST or GST-FBP1 recombinant proteins. Immunoblots are representative of results from two independent experiments (n = 2). Arrows, expected molecular weight. E, Schematic diagram depicting a set of GST-IQGAP1 recombinant protein constructs. F, Western blot analysis of FBP1 proteins in PANC-1 whole cell lysate pulled down by GST or GST-IQGAP1 recombinant proteins. Immunoblots are representative of results from two independent experiments (n = 2). Arrows, expected molecular weight.

The interaction between ectopically expressed Flag-FBP1 and Myc-IQGAP1 in 293T cells and endogenous FBP1 and IQGAP1 in PANC-1 PDAC cells was confirmed by reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays (Fig. 1B). To define which region(s) in FBP1 mediate its interaction with IQGAP1, we constructed seven GST-FBP1 recombinant proteins corresponding to seven exons of FBP1 as reported previously (Fig. 1C; ref. 12). GST pull-down assays demonstrated that GST-FBP1 E4 (amino acids 143–188), but not GST or other GST-FBP1 recombinant proteins, interacted with IQGAP1 (Fig. 1D). To determine which domain(s) of IQGAP1 are involved in FBP1 binding, we generated six GST-IQGAP1 recombinant proteins corresponding to six well-characterized functional domains of IQGAP1 (Fig. 1E). GST pull-down assays revealed that the WW domain of IQGAP1 specifically interacted with FBP1 proteins expressed in PANC-1 cells (Fig. 1F). Thus, as demonstrated by in vitro assays and in cultured PDAC cells, FBP1 interacts with the scaffold protein IQGAP1.

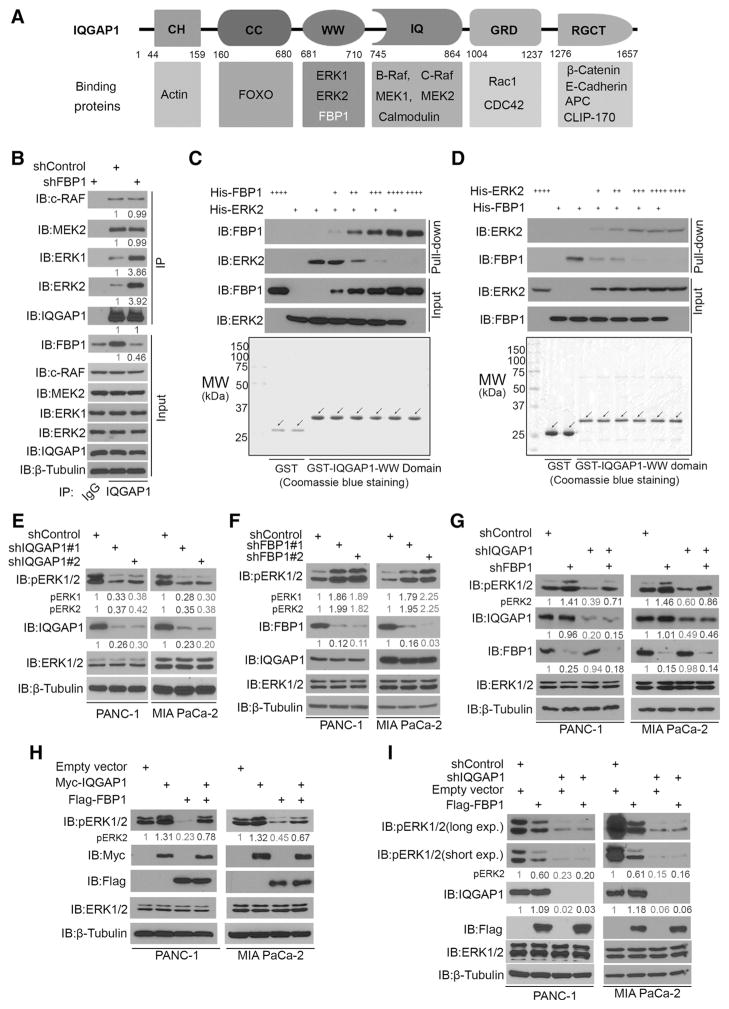

FBP1 competes with ERK1/2 to bind to the WW domain of IQGAP1 and inhibits ERK1/2 phosphorylation

It is known that IQGAP1 interacts with c-RAF, MEK2, and ERK2 and other proteins in mammalian cells (Fig. 2A; refs. 6–8, 18, 19). Similar to these findings, we demonstrated that IQGAP1 interacted with components of the MAPK pathway in PANC-1 cells (Fig. 2B). Importantly, we found that knockdown of FBP1 increased IQGAP1 interaction with both ERK1 and ERK2, but had no overt effect on IQGAP1 interaction with c-RAF and MEK2 (Fig. 2B). ERK2 was known to bind to the WW domain of IQGAP1 (8). Our data also showed that FBP1 bound to the WW domain of IQGAP1 (Figs. 1F and 2A). To determine the impact of FBP1 on the interaction between IQGAP1 and ERK2, we generated His-FBP1 and His-ERK2 constructs, purified these proteins from bacteria, and performed GST pull-down assays with GST or GST-IQGAP1 P3 (WW domain only). We demonstrated that FBP1 competed with ERK2 to bind to the WW domain of IQGAP1 in vitro (Fig. 2C and D).

Figure 2.

FBP1 binds to the WW domain of IQGAP1 and inhibits ERK1/2 phosphorylation. A, Schematic diagram depicting the domain structure of IQGAP1 and previously defined proteins bound by each domain. B, Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate and co-IP samples in PANC-1 cells 48 hours after being infected with lentivirus expressing control shRNA or FBP1-specific shRNAs. MAPK pathway proteins (c-RAF, MEK2, ERK2, or ERK1) coimmunoprecipitated by IQGAP1 were quantified by ImageJ software and normalized to the quantified value of immunoprecipitated IQGAP1. The normalized values were further normalized to the value in cells infected with shControl. Immunoblots (IB) are representative of results from two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. C, His-FBP1 and His-ERK2 were purified from bacteria. His-ERK2 were incubated with different concentrations of His-FBP1 and subjected to GST pull-down using GST or GST-IQGAP1 P3 (FBP1-binding region in IQGAP1) and Western blot analysis using indicated antibodies. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2). Arrows, expected molecular weight. D, His-FBP1 were incubated with different concentrations of His-ERK2 and subjected to GST pull-down using GST or GST-IQGAP1 P3 and Western blot analysis using indicated antibodies. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2). Arrows, expected molecular weight. E, Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate of PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells 48 hours after being infected with lentivirus expressing control shRNA or IQGAP1-specific shRNA. pERK1, pERK2, and IQGAP1 proteins were quantified by ImageJ software and normalized to the quantified value of β-tubulin. The normalized values were further normalized to the value in cells infected with shControl. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. F, Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate of PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells 48 hours after being infected with lentivirus expressing control shRNA or IQGAP1-specific shRNA. pERK1, pERK2, and FBP1 proteins were quantified as in E. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. G, Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate of PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells 48 hours after being infected with lentivirus expressing control shRNA, FBP1-specific, IQGAP1-specific shRNA, or both shRNA. pERK2, FBP1, and IQGAP1 proteins were quantified as in E. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. H, Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate of PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells 24 hours after being transfected with indicated plasmids. pERK2 proteins were quantified as in E. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments n(= 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. I, PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells were infected with control and IQGAP1-specific shRNAs. After 24 hours, PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells were transfected with indicated constructs for another 24 hours, followed by Western blot analysis. Exp., exposure. pERK2 and IQGAP1 proteins were quantified as in E. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments.

Given that FBP1 inhibits IQGAP1–ERK interaction, we sought to determine whether FBP1 regulates phosphorylation and activation of ERK1/2. We performed knockdown experiments in PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 PDAC cell lines. Knockdown of IQGAP1 by two independent gene-specific shRNAs markedly decreased ERK1/2 phosphorylation (pERK1/2; Fig. 2E). Knocking down FBP1 alone increased pERK1/2 (Fig. 2F). The effect of FBP1 knockdown on ERK1/2 phosphorylation was completely reversed by IQGAP1 knockdown (Fig. 2G). Conversely, overexpression of IQGAP1 increased pERK1/2 in both PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines, and this effect was largely diminished in cells cotransfected with FBP1 (Fig. 2H). Next, we generated IQGAP1-depleted PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells (Fig. 2I; Supplementary Fig. S1A). Although pERK1 was hardly detectable and pERK2 was very low in IQGAP1-depleted cells, overexpression of FBP1 failed to affect pERK1/2 in both cell lines (Fig. 2I). These data suggest that the effect of FBP1 on pERK1/2 is mediated primarily through IQGAP1. Taken together, our results indicate that FBP1 competes with ERK1/2 to bind to the WW domain of IQGAP1 and inhibits ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

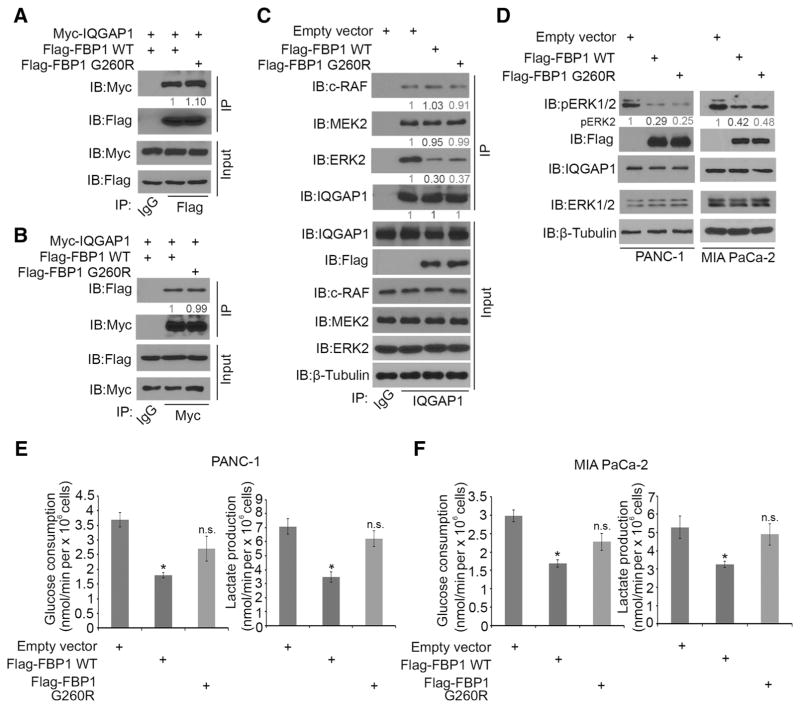

FBP1 inhibits ERK1/2 phosphorylation independent of its enzymatic activity

To rule out the possibility that the enzymatic activity of FBP1 is required to inhibit ERK1/2 phosphorylation, we constructed a catalytically inactive mutant G260R of FBP1 as described previously (20, 21). Reciprocal co-IP assays demonstrated that the G260R mutation did not affect the IQGAP1–FBP1 interaction in 293T cells (Fig. 3A and B). Ectopic expression of FBP1-WT and FBP1-G260R mutant both decreased IQGAP1 interaction with ERK2, but not c-RAF and MEK2 (Fig. 3C). We transfected FBP1-WT and G260R mutant into PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells and demonstrated that ectopic expression of FBP1-WT and FBP1-G260R mutant resulted in similar inhibitory effect on pERK1/2 in both cell lines (Fig. 3D). As expected, forced expression of FBP1-WT but not FBP1-G260R mutant inhibited glucose consumption and lactate production in these cells (Fig. 3E and F). Our data indicate that FBP1 binds to IQGAP1 and inhibits ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a manner independent of its enzymatic activity.

Figure 3.

FBP1 inhibits ERK1/2 phosphorylation independent of its enzymatic activity. A and B, Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate and co-IP samples from PANC-1 cells 24 hours after being transfected with indicated plasmids. Myc-IQGAP1 in A were quantified and normalized to the quantified value of immunoprecipitated Flag-FBP1. Flag-FBP1 in B were quantified and normalized to the quantified value of immunoprecipitated Myc-IQGAP1. The normalized values were further normalized to the value in the cells transfected with Flag-FBP1 WT group. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. C, Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate and co-IP samples in PANC-1 cells 24 hours after transfected with indicated plasmids. MAPK pathway proteins (c-RAF, MEK2, and ERK2) immunoprecipitated by IQGAP1 were quantified as in A. Western blots shown are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. D, Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate of PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells 24 hours after being transfected with indicated plasmids. pERK2 proteins were quantified and normalized to the quantified value of β-tubulin. The normalized values were further normalized to the shControl group. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. E and F, Measurement of glucose consumption and L-lactate production in the spent medium of PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells 48 hours after being transfected with indicated constructs. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). E.V., empty vector; n.s., not significant; *, P < 0.01.

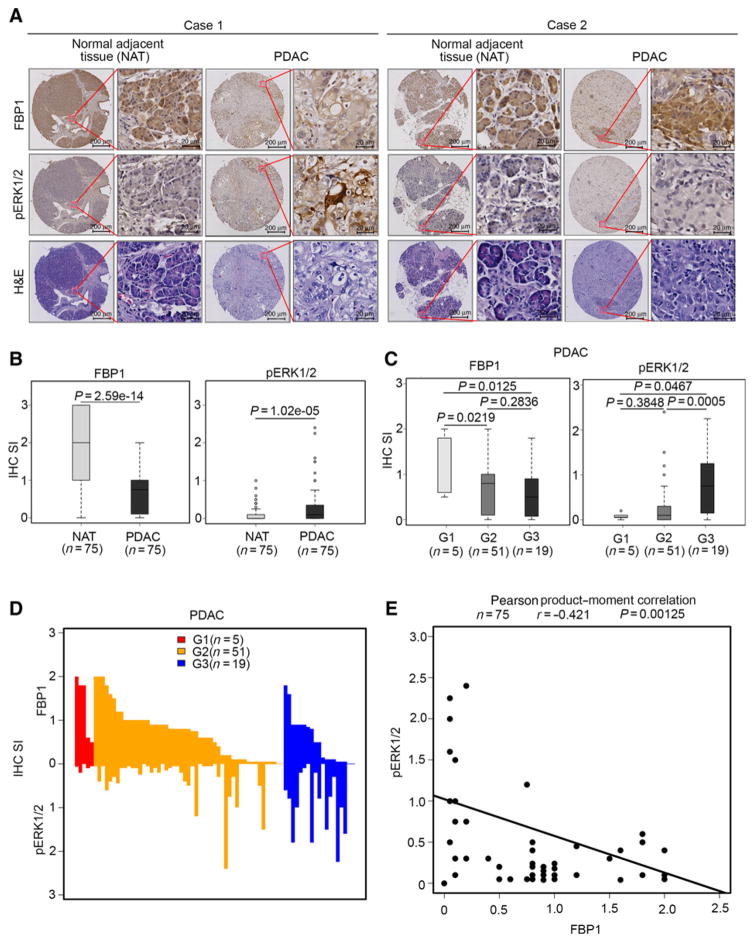

Decreased FBP1 expression correlates with increased pERK1/2 level in PDAC patient specimens

It has been reported previously that FBP1 is downregulated in human PDAC cell lines and patient samples. To explore clinical relevance of FBP1 inhibition of IQGAP1-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation, we sought to determine whether expression of FBP1 and pERK1/2 correlates in human PDAC specimens. We examined the expression of these two proteins by performing IHC on a TMA containing a cohort of pancreatic cancer samples (n = 75 normal-tumor paired TMA specimens) obtained from 75 patients. IHC staining was evaluated by measuring both percentage of positive cells and staining intensity. Representative images of low/no and high staining of FBP1 and pERK1/2 and corresponding hematoxylin and eosin staining are shown in Fig. 4A. PDAC tissues had lower expression of FBP1 (P = 2.59e–14) but higher pERK1/2 levels (P = 1.02e–05) compared with the adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 4B). Our analysis also showed that activation of pERK1/2 was mainly detected in higher tumor grade (G2 and G3), and its expression positively correlated with tumor grades (Pearson product–moment correlation coefficiency r = 0.4043565, P = 0.0003207). In contrast, FBP1 expression inversely correlated with tumor grades (Pearson product–moment correlation r = −0.2674027, P = 0.02038; Fig. 4C and D). Further analysis indicated that decreased expression of FBP1 correlated with increased levels of pERK1/2 in PDAC tissues of this cohort (Pearson product–moment correlation coefficiency r = −0.421, P = 0.0125; Fig. 4E). These data indicate that loss of or reduced expression of FBP1 correlates with increased pERK1/2 levels, at least in a subset of PDAC patients, and deregulation of these proteins associates with disease progression.

Figure 4.

Expressions of FBP1 and pERK1/2 inversely correlate in PDAC patient specimens. A, Representative images of IHC of anti-FBP1 and anti-pERK1/2 antibodies and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of TMA (n = 75) tissue sections. Scale bars are shown as indicated. B, Box plots of FBP1 and pERK1/2 expression as indicated by the staining index (SI) in paired normal-tumor tissues from PDAC patients (n = 75). The P values are also shown. C, Box plots of FBP1 and pERK1/2 expression determined as indicated by the staining index at different tumor grades. G1, G2, and G3 represent well-differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated tumors, respectively. The P values are also shown. D, Waterfall diagram showing staining index of FBP1 and pERK1/2 in TMA and association with tumor grades. E, Correlation analysis of the staining index for expression of FBP1 and pERK1/2 proteins in PDAC patient specimens (n = 75). Pearson product-moment correlation coefficiency and the P values are also shown.

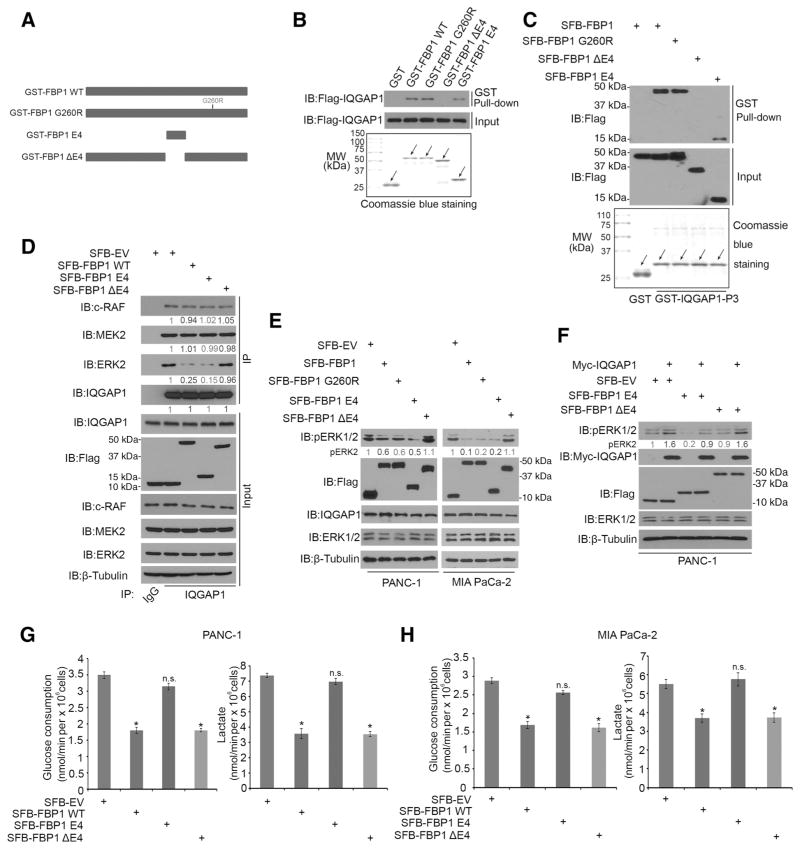

A small FBP1-derived peptide inhibits IQGAP1 binding to and phosphorylation of ERK1/2

GST pull-down assays indicated that GST-FBP1 E4 (143–188) interacted with IQGAP1 (Fig. 1D). We thus generated a GST-tagged bacterial expression vector for an FBP1 mutant in which the E4 domain is deleted (FBP1ΔE4; Fig. 5A). In vitro protein binding studies demonstrated that GST-FBP1-WT, GST-FBP1-G260R mutant, or GST-FBP1 E4 (143–188), but not GST or GST-FBP1ΔE4 recombinant proteins, interacted with IQGAP1 (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, GST-IQGAP1 P3 (WW domain) was able to pull down SFB-FBP1-WT, SFB-FBP1-G260R mutant and SFB-FBP1 E4, but not SFB-FBP1ΔE4 (Fig. 5C). These data revealed that the E4 fragment of FBP1 is required for its interaction with the WW domain of IQGAP1 in vitro.

Figure 5.

A small FBP1-derived peptide inhibits IQGAP1 binding to ERK proteins and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. A, Schematic diagram depicting a set of GST-FBP1 recombinant protein constructs. B, Western blot analysis of IQGAP1 proteins in PANC-1 whole cell lysate pulled down by GST or GST-FBP1 recombinant proteins. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2). C, Western blot analysis of SFB-tagged recombinant proteins in PANC-1 whole cell lysate pulled down by GST or GST-IQGAP1-P3 recombinant proteins. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2). D, Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate and co-IP samples from PANC-1 cells 24 hours after being transfected with indicated plasmids. MAPK pathway proteins (c-RAF, MEK2, and ERK2) coimmunoprecipitated by IQGAP1 were quantified and normalized to the quantified value of immunoprecipitated IQGAP1. The normalized values were further normalized to the value in cells transfected with SFB-EV. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. E, Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate of PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells 24 hours transfected with indicated plasmids. pERK2 proteins were quantified as in D. Western blots are representative of results from two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. F, Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate of PANC-1 cells 24 hours after being transfected with indicated plasmids. pERK2 was quantified as in D. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. G and H, Measurement of glucose consumption and L-lactate production in the spent medium of PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells 48 hours after transfection with indicated constructs. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). n.s., not significant; *, P < 0.01.

Next, we sought to determine whether FBP1 E4 alone is able to inhibit IQGAP1–ERK protein interaction and regulates pERK1/2. We demonstrated that ectopic expression of SFB-FBP1 E4 but not SFB-FBP1ΔE4 decreased IQGAP1 interaction with ERK2, but not c-RAF and MEK2 (Fig. 5D). The SFB empty vector (SFB-EV) and SFB-FBP1-WT were included as a negative and positive control, respectively. We also demonstrated that expression of SFB-FBP1 E4 but not SFB-FBP1ΔE4 inhibited pERK1/2 in both PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines (Fig. 5E). We further showed that IQGAP1-enhanced pERK1/2 was attenuated by forced expression of SFB-FBP1 E4 but not SFB-FBP1ΔE4 in PANC-1 cells (Fig. 5F). Moreover, in agreement with the fact that FBP1 E4 did not contain the enzymatic domain of FBP1, it is not surprising that FBP1 E4 had no effect on glucose metabolism in both PDAC cell lines examined (Fig. 5G and H). These findings further imply that FBP1 inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation is not only exerted in a fashion independent of its enzymatic activity, but also uncoupled from glucose consumption and lactate production. Taken together, these data indicate that a small FBP1-derived peptide (FBP1 E4) is able to inhibit IQGAP1 binding to ERK proteins and ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

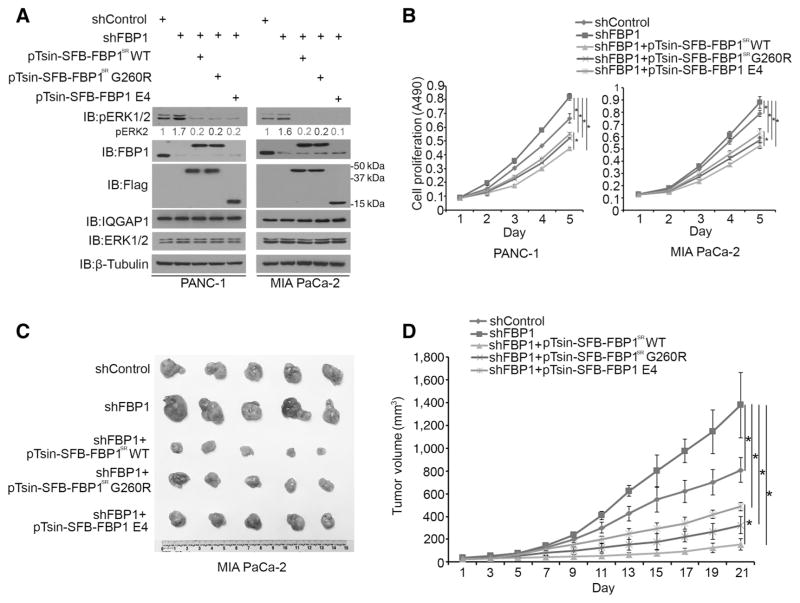

A small FBP1-derived peptide inhibitor suppresses PDAC cell growth in culture and in mice

Previous studies report that the RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK signaling pathway promotes pancreatic cancer proliferation and progression (22–24). We sought to investigate the role of FBP1 in pancreatic cancer cell proliferation. PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells were infected with control shRNA or FBP1-specific shRNA. Cells infected with FBP1-specific shRNAs were further transfected with empty lentiviral expression vector (pTsin) or shRNA-resistant WT FBP1 (pTsin-SFB-FBP1SR) or two mutants (pTsin-SFB-FBP1-G260RSR or pTsin-SFB FBP1 E4). These cells were used for Western blot analysis, MTS assay, and animal studies. As demonstrated in Fig. 6A, both FBP1 knockdown and SFB-FBP1, SFB-FBP1 G260R, SFB-FBP1 E4 overexpression were effective in both PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells. The corresponding changes of pERK1/2 were also detected in cells infected with different vectors (Fig. 6A). MTS assay indicated that knockdown of FBP1 alone increased cell proliferation compared with the control group (Fig. 6B). Notably, restored expression of shRNA-resistant FBP1-WT, FBP1-G260R, or FBP1 E4 invariably inhibited cell proliferation. It is not surprising that the growth-inhibitory ability of FBP1-G260R or FBP1 E4 was not as potent as FBP1-WT (Fig. 6B) because the enzymatic activity in FBP1-WT may also contribute to growth inhibition. Similar to the results in MIA PaCa-2 cells in culture, knockdown of FBP1 alone promoted growth of MIA PaCa-2 xenografts in mice (Fig. 6C and D). However, this effect was reversed by restored expression of shRNA-resistant FBP1-WT, FBP1-G260R, or FBP1 E4 (Fig. 6C and D). These data suggest that FBP1 and a small FBP1-derived peptide (FBP1 E4) are able to suppress PDAC cell growth in culture and in mice.

Figure 6.

A small FBP1-derived peptide inhibitor suppresses pancreatic cancer growth in culture and in mice. A and B, PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells were infected with lentivirus expressing control shRNA or FBP1-specific shRNA. Twenty-four hours after infection, control shRNA and FBP1 shRNA-infected cells were further infected with lentiviral vectors as indicated. Forty-eight hours after puromycin selection, cells were harvested for Western blots (A) and MTS assay (B). pERK2 proteins were quantified and normalized to the quantified value of β-tubulin. The normalized values were further normalized to the control group as shown in the panel. Western blots in A are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. Data shown in B are mean values ± SD from six replicates (n = 6). *, P < 0.01. C and D, MIA PaCa-2 cells were infected with lentivirus as in A, and 72 hours after infection and puromycin selection, cells were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of NSG mice and tumor growth was measured for 21 days. Tumors in each group at day 21 were harvested, photographed, and are shown in C. Data in D are shown as means ± SD (n = 5). *, P < 0.01 comparing size of tumors in different groups at day 21.

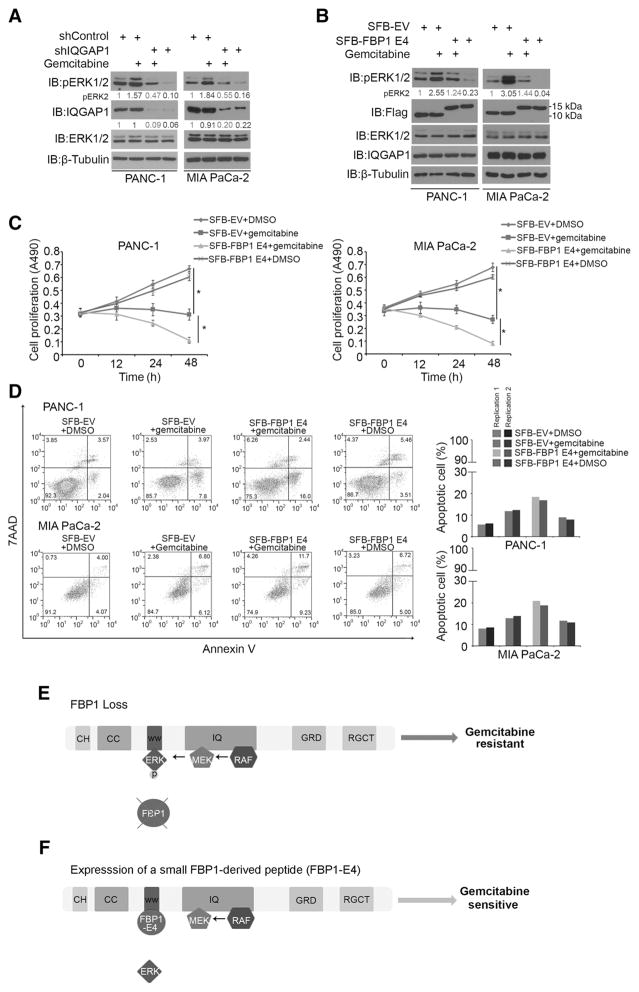

The FBP1-derived peptide impedes gemcitabine-induced ERK activation and chemoresistance

The nucleoside analogue gemcitabine is a leading therapeutic agent for pancreatic cancer (25). However, it fails to significantly improve the outcome of pancreatic carcinoma patients due to acquisition of chemoresistance in most tumor cells (26). It is well documented that gemcitabine treatment results in activation of the RAS–RAF–MAPK pathway (27). However, the mechanism underlying gemcitabine-induced MAPK activation remains poorly understood. Moreover, gemcitabine sensitivity can be increased through combination with a pERK-reducing agent (28). We sought to determine whether FBP1 E4 can restore gemcitabine sensitivity in PDAC cells through inhibition of pERK1/2. In agreement with the findings in the BXPC-3 PDAC cell line (27) and RAS mutation–induced mouse PDAC tumors (29), we found that the mean value of pERK1/2 staining was relatively higher in gemcitabine-treated PDAC patient specimens compared with that in untreated counterparts (Supplementary Fig. S1B and S1C). It is worth noting that the difference in pERK1/2 staining between these two groups was not statistically significant, which could be due to the very small number of gemcitabine-treated PDAC patient samples (Supplementary Fig. S1C).

Similar to the previous reports (30, 31), we found that MIA PaCa-2 cells are gemcitabine sensitive and PANC-1 cells are gemcitabine resistant (Supplementary Fig. S2A). In agreement with these findings, we demonstrated that gemcitabine-sensitive MIA PaCa-2 cells have much higher FBP1 expression and much lower pERK1/2 compared with gemcitabine-resistant PANC-1 cells (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Moreover, we demonstrated that gemcitabine treatment increased pERK1/2 levels in both PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines (Fig. 7A and B), which is consistent with the effects of gemcitabine in PDAC tumors in mice and patients (Supplementary Fig. S1B and S1C; ref. 29). We further showed that gemcitabine-induced elevation of pERK1/2 was unlikely due to the effect of gemcitabine on IQGAP1 interaction with ERK1 and ERK2 (Supplementary Fig. S2C) and the cell-cycle effects of gemcitabine (Supplementary Fig. S2D–S2F). Notably, knockdown of IQGAP1 abolished gemcitabine-induced pERK1/2 in both cell lines (Fig. 7A). We transfected PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines with control or FBP1 E4 expression vectors and treated cells with DMSO or gemcitabine. FBP1 E4 expression impeded gemcitabine-induced ERK activation in both cell lines (Fig. 7B). MTS assays demonstrated that gemcitabine treatment combined with FBP1 E4 expression resulted in greater reduction of cell proliferation than gemcitabine alone (Fig. 7C). Moreover, cotreatment of cells with gemcitabine and FBP1 E4 induced higher cell death than gemcitabine alone (Fig. 7D). Collectively, these data suggest that the FBP1-derived small peptide impedes gemcitabine-induced ERK activation and overcomes chemoresistance in PDAC cells.

Figure 7.

FBP1 E4 peptide impedes gemcitabine-induced ERK activation and chemoresistance. A, Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate of PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells 48 hours after infection with lentivirus expressing indicated shRNAs. PANC-1 cells were treated with or without gemcitabine (10 μmol/L) and MIA PaCa-2 cells with or without gemcitabine (5 μmol/L) for 24 hours prior to harvest. pERK2 proteins were quantified and normalized to the quantified value of β-tubulin. The normalized values were further normalized to the shControl group. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. B–D, PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cells were transfected with indicated plasmids. Twenty-four hours after transfection, PANC-1 cells were treated with or without gemcitabine (10 μmol/L) and MIA PaCa-2 cells with or without gemcitabine (1 μmol/L). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested for Western blot (B), MTS assay (C), and Annexin V assay and flow cytometry analysis (D). pERK2 in B was quantified as in A. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments (n = 2), and the quantified value shown was the average of the normalized values for each protein band from the two independent experiments. For panel C, data shown are mean values ± SD from six replicates (n = 6). *, P < 0.01 for comparison at 48 hours. Original data of FACS analysis (left) and quantified results from two biological replicates (right) are shown in D. E and F, Models depicting that FBP1 inhibits ERK activation and gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer by blocking IQGAP1–MAPK kinase interaction. In pancreatic cancer cells, IQGAP1 functions as a scaffold for activation of RAF, MEK, and ERK. Loss of FBP1 promotes aberrant ERK activation and gemcitabine resistance (E). A small FBP1-derived peptide competes with ERK to bind to the WW domain of IQGAP1 and inhibits ERK1/2 phosphorylation, thereby resensitizing pancreatic cancer cells to the treatment of gemcitabine (F).

Discussion

IQGAP proteins are an evolutionarily conserved multistructural domain protein family, which participate in cell adhesion, migration, signaling, division, and many other biological processes (32, 33). The IQGAP family is comprised of three members in humans. IQGAP1, which is the most characterized, is upregulated in several tumor types, including pancreatic carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma. IQGAP1 can bind to Cdc42 and Rac1, E-cadherin, β-catenin, calmodulin, and components of the MAPK pathway through protein–protein interaction and plays an important role in tumorigenesis (17). IQGAP1 is a MAPK scaffold essential for effective propagation of the MAPK signaling cascade (6). Our data demonstrate that the tumor suppressor protein FBP1 inhibits PDAC cell growth by binding with IQGAP1 and impeding IQGAP1-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation and activation. Therefore, in tumors where IQGAP1 is overexpressed (34–36), overexpression of IQGAP1 may represent an alternative to promote cancer progression by overcoming the inhibitory effect of FBP1 expression on ERK1/2 activity.

The MAPK pathway is important for cancer cell proliferation, migration, survival, and resistance to cancer therapy (37). A variety of MAPK blockers, including MEK inhibitors and ERK inhibitors, has been developed (38). These agents are relatively ineffective in many clinical trials (39). Combinations of MAPK blockers with cytotoxic chemotherapy and/or other targeted agents are being examined to expand the efficacy of cancer therapies. Also, scaffold–kinase interaction blockade, a novel mechanism different from direct kinase inhibition, represents a promising strategy to improve the efficacy of cancer treatments (8). Aberrant activation of the RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK1/2 pathway occurs in more than 90% of human pancreatic cancers. Our present study demonstrates that ERK activation can be abolished by genetic depletion of IQGAP1 or treating cells with a small FBP1-derived peptide inhibitor. Thus, FBP1-mediated suppression of the IQGAP1–MAPK interaction may be a new target of pancreatic cancer therapy.

Gemcitabine has emerged as the leading chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of PDAC. However, gemcitabine fails to significantly improve the outcome of pancreatic carcinoma patients due to development of chemoresistance in patients. Gemcitabine treatment often induces ERK activation (28), which has been recognized as a cause of drug resistance to pancreatic cancer therapies. Our findings show that increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by gemcitabine treatment can be inhibited by cotreatment of cells with IQGAP1 knockdown or a small FBP1-derived peptide inhibitor. Thus, the IQGAP1–MAPK interaction may represent a key mechanism responsible for ERK activation and gemcitabine resistance in PDAC.

FBP1 is a rate-limiting enzyme in gluconeogenesis and functions as a tumor suppressor in numerous cancer types, including pancreatic cancer. Decreased expression of FBP1 associates with advanced tumor stage and poor overall survival in PDAC patients (11). Ectopic expression of FBP1 inhibits tumor growth in renal carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma (10, 12). It has been documented that FBP1 suppresses tumor progression mainly through reducing aerobic glycolysis to inhibit the Warburg effect (10), or by inhibiting nuclear HIF function in renal carcinoma (12). Our data show that FBP1 inhibits tumor growth in PDAC. Mechanistically, we further show that FBP1 binds to the WW domain of IQGAP1 and disrupts the interaction of IQGAP1–ERK1/2 in a manner independent of FBP1 enzymatic activity, representing a previously uncharacterized role of FBP1 in inhibition of tumor growth and progression.

In summary, we demonstrate that FBP1 acts as a negative modular of the IQGAP1–MAPK signaling axis by binding to the WW domain of IQGAP1 and impeding IQGAP1-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation, independent of its enzymatic activity, in PDAC cells. We further show that ERK activation is abolished by genetic depletion of IQGAP1 or treating cells with a small FBP1-derived peptide inhibitor. Most importantly, we define a bioactive FBP1-derived peptide inhibitor, which inhibits gemcitabine-induced ERK activation and enhances the efficacy of gemcitabine in PDAC (Fig. 7E and F). These findings highlight that inhibition of the IQGAP1–ERK1/2 signaling axis by FBP1 can be harnessed for effective treatment of PDAC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank W.R. Bamlet and J.J. Brooks at Mayo Clinic for acquisition of pERK1/2 staining data from gemcitabine-treated and untreated PDAC patient samples.

Grant Support

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (CA134514, CA130908, and CA193239 to H. Huang and CA140550 to A.H. Tang), the Pancreatic Cancer SPORE grant (P50 CA102701 to D.D. Billadeau), and Scientific Research Training Program for Young Talents of Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. Research supported by the 2010 Pancreatic Cancer Action Network-AACR Innovative Grant, Grant Number 10-60-25-TANG (A.H. Tang).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

A patent application (CN 105734031 A) has been submitted by Xin Jin and Haojie Huang based on the results reported in this study. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design: X. Jin, H. Huang

Acquisition of data (provided animals, acquired and managed patients, provided facilities, etc.): L. Zhang, A.H. Tang, H. Wu

Analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis): X. Jin, L. Wang, T. Ma, L. Zhang

Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: X. Jin, H. Wu, H. Huang

Administrative, technical, or material support (i.e., reporting or organizing data, constructing databases): X. Jin, A.H. Tang, D.D. Billadeau

Study supervision: H. Wu, H. Huang

Other (technical support): Y. Pan

References

- 1.Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0901557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Lancet O. Pancreatic cancer in the spotlight. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:241. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70097-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bos JL. ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4682–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayes TK, Neel NF, Hu C, Gautam P, Chenard M, Long B, et al. Long-term ERK inhibition in KRAS-mutant pancreatic cancer is associated with MYC degradation and senescence-like growth suppression. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:75–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy M, Li Z, Sacks DB. IQGAP1 is a scaffold for mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7940–52. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.7940-7952.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roy M, Li Z, Sacks DB. IQGAP1 binds ERK2 and modulates its activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17329–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jameson KL, Mazur PK, Zehnder AM, Zhang J, Zarnegar B, Sage J, et al. IQGAP1 scaffold-kinase interaction blockade selectively targets RAS-MAP kinase-driven tumors. Nat Med. 2013;19:626–30. doi: 10.1038/nm.3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong C, Yuan T, Wu Y, Wang Y, Fan TW, Miriyala S, et al. Loss of FBP1 by Snail-mediated repression provides metabolic advantages in basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:316–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirata H, Sugimachi K, Komatsu H, Ueda M, Masuda T, Uchi R, et al. Decreased expression of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase associates with glucose metabolism and tumor progression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3265–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu Y, Shi M, Chen H, Gu J, Zhang J, Shen B, et al. NPM1 activates metabolic changes by inhibiting FBP1 while promoting the tumorigenicity of pancreatic cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:21443–51. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li B, Qiu B, Lee DS, Walton ZE, Ochocki JD, Mathew LK, et al. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase opposes renal carcinoma progression. Nature. 2014;513:251–5. doi: 10.1038/nature13557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Wang J, Xing H, Li Q, Zhao Q, Li J. Down-regulation of FBP1 by ZEB1-mediated repression confers to growth and invasion in lung cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;411:331–40. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2595-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Pan Y, Zheng L, Choe C, Lindgren B, Jensen ED, et al. FOXO1 inhibits Runx2 transcriptional activity and prostate cancer cell migration and invasion. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3257–67. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang H, Cheville JC, Pan Y, Roche PC, Schmidt LJ, Tindall DJ. PTEN induces chemosensitivity in PTEN-mutated prostate cancer cells by suppression of Bcl-2 expression. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38830–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103632200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin X, Pan Y, Wang L, Zhang L, Ravichandran R, Potts PR, et al. MAGE-TRIM28 complex promotes the Warburg effect and hepatocellular carcinoma progression by targeting FBP1 for degradation. Oncogenesis. 2017;6:e312. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2017.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White CD, Brown MD, Sacks DB. IQGAPs in cancer: a family of scaffold proteins underlying tumorigenesis. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1817–24. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan CW, Jin X, Zhao Y, Pan Y, Yang J, Karnes RJ, et al. AKT-phosphorylated FOXO1 suppresses ERK activation and chemoresistance by disrupting IQGAP1-MAPK interaction. EMBO J. 2017;36:995–1010. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren JG, Li Z, Sacks DB. IQGAP1 modulates activation of B-Raf. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10465–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611308104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asberg C, Hjalmarson O, Alm J, Martinsson T, Waldenstrom J, Hellerud C. Fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase deficiency: enzyme and mutation analysis performed on calcitriol-stimulated monocytes with a note on long-term prognosis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33(Suppl 3):S113–21. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-9034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choe JY, Fromm HJ, Honzatko RB. Crystal structures of fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase: mechanism of catalysis and allosteric inhibition revealed in product complexes. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8565–74. doi: 10.1021/bi000574g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neuzillet C, Hammel P, Tijeras-Raballand A, Couvelard A, Raymond E. Targeting the Ras-ERK pathway in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013;32:147–62. doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9396-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collisson EA, Trejo CL, Silva JM, Gu S, Korkola JE, Heiser LM, et al. A central role for RAF→MEK→ERK signaling in the genesis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:685–93. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burris HA, III, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arlt A, Gehrz A, Muerkoster S, Vorndamm J, Kruse ML, Folsch UR, et al. Role of NF-kappaB and Akt/PI3K in the resistance of pancreatic carcinoma cell lines against gemcitabine-induced cell death. Oncogene. 2003;22:3243–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang M, Lu X, Dong X, Hao F, Liu Z, Ni G, et al. pERK1/2 silencing sensitizes pancreatic cancer BXPC-3 cell to gemcitabine-induced apoptosis via regulating Bax and Bcl-2 expression. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:66. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0451-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fryer RA, Barlett B, Galustian C, Dalgleish AG. Mechanisms underlying gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer and sensitisation by the iMiD lenalidomide. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:3747–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyabayashi K, Ijichi H, Mohri D, Tada M, Yamamoto K, Asaoka Y, et al. Erlotinib prolongs survival in pancreatic cancer by blocking gemcitabine-induced MAPK signals. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2221–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Awasthi N, Zhang C, Schwarz AM, Hinz S, Wang C, Williams NS, et al. Comparative benefits of Nab-paclitaxel over gemcitabine or polysorbate-based docetaxel in experimental pancreatic cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:2361–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rathos MJ, Joshi K, Khanwalkar H, Manohar SM, Joshi KS. Molecular evidence for increased antitumor activity of gemcitabine in combination with a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, P276-00 in pancreatic cancers. J Transl Med. 2012;10:161. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe T, Wang S, Kaibuchi K. IQGAPs as key regulators of actin-cytoskeleton dynamics. Cell Struct Funct. 2015;40:69–77. doi: 10.1247/csf.15003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hedman AC, Smith JM, Sacks DB. The biology of IQGAP proteins: beyond the cytoskeleton. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:427–46. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang XX, Li XZ, Zhai LQ, Liu ZR, Chen XJ, Pei Y. Overexpression of IQGAP1 in human pancreatic cancer. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013;12:540–5. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(13)60085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zoheir KM, Abd-Rabou AA, Harisa GI, Ashour AE, Ahmad SF, Attia SM, et al. Gene expression of IQGAPs and Ras families in an experimental mouse model for hepatocellular carcinoma: a mechanistic study of cancer progression. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:8821–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayashi H, Nabeshima K, Aoki M, Hamasaki M, Enatsu S, Yamauchi Y, et al. Overexpression of IQGAP1 in advanced colorectal cancer correlates with poor prognosis-critical role in tumor invasion. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:2563–74. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burotto M, Chiou VL, Lee JM, Kohn EC. The MAPK pathway across different malignancies: a new perspective. Cancer. 2014;120:3446–56. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao Y, Adjei AA. The clinical development of MEK inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:385–400. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitai H, Ebi H. Key roles of EMT for adaptive resistance to MEK inhibitor in KRAS mutant lung cancer. Small GTPases. 2016 Jul 8; doi: 10.1080/21541248.2016.1210369. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.