Abstract

Objective

Symptoms of insomnia and heavy alcohol use tend to co-occur among military and veteran samples. The current study examined insomnia as a moderator of the association between alcohol use and related consequences among young adult veterans in an effort to extend and replicate findings observed in samples of civilian young adults.

Method

Young adult veterans (N = 622; 83% male; age M = 29.0, SD = 3.4) reporting alcohol use in the past year completed measures of insomnia severity, alcohol use, and alcohol-related consequences as part of a larger intervention trial. Participants were classified as screening ‘positive’ (n = 383, 62%) or ‘negative’ (n = 239, 38%) for insomnia using the Insomnia Severity Index. Hierarchical regression was used to examine the interaction between drinking quantity and insomnia on alcohol-related consequences. Predictor and outcome variables were measured concurrently.

Results

Both a greater number of drinks per week and a positive insomnia screen were associated with more alcohol-related consequences. Drinks per week and insomnia screen interacted to predict alcohol-related consequences, such that the effect of drinking on alcohol-related consequences was stronger in the context of a positive versus negative insomnia screen.

Conclusion

Drinking is associated with more alcohol-related consequences in the presence of clinically significant insomnia symptoms. These findings replicate those documented in civilian young adults and indicate that insomnia may be an appropriate target for alcohol prevention and intervention efforts among young adult veterans.

Keywords: alcohol, drinking, military, sleep, problems

1. Introduction

Heavy alcohol use is prevalent among military and veteran populations. Nearly half (47%) of active duty women/men report four/five or more drinks on one occasion in the past month, and approximately 20% report heavy episodic drinking every week (Bray, Brown, & Williams, 2013). These forms of heavy drinking place military personnel at risk for negative consequences ranging from general stress to suicidal ideation (Barlas, Higgins, Pflieger, & Diecker, 2013) and may be particularly problematic for those in young adulthood, which has been proposed as a critical period in the development of alcohol use disorders among military personnel (Fink et al., 2016).

Notably, two out of five U.S. Army soldiers returning from Iraq or Afghanistan report heavy drinking in the context of poor sleep health (Swinkels, Ulmer, Beckham, Buse, & Calhoun, 2013). Specifically, 71.5% report difficulty falling or staying asleep and 72.3% report fewer than seven hours of sleep per night (Swinkels et al., 2013). Such sleep disturbances have been associated with increased odds of alcohol use and related problems among military personnel and veterans (Luxton et al., 2011; Swinkels et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2015). While the precise mechanisms underlying these associations are unclear, evidence suggests that chronic sleep restriction (which is functionally similar to the sleep patterns of individuals with insomnia) leads to deficits in attention and working memory (Alhola & Polo-Kantola, 2007; Benitez & Gunstad, 2012; Fortier-Brochu & Morin, 2014), which may then lead to a greater propensity for poor decision-making and increased risk of alcohol problems. In support of this hypothesis, the combination of alcohol use and poor sleep quality has been associated with elevations in alcohol-related problems among college students who drink (Kenney, LaBrie, Hummer, & Pham, 2012; Miller, DiBello, Lust, Carey, & Carey, 2016).

The current study aimed to extend previous research by examining the interactive effects of alcohol use and insomnia symptoms among young adult veterans. Consistent with research among college students (Kenney et al., 2012; Miller, DiBello, et al., 2016), we hypothesized that insomnia would moderate the association between alcohol use and consequences, such that drinking quantity would be associated with more alcohol-related consequences in the context of insomnia. To isolate the contribution of insomnia to alcohol use outcomes, we controlled for symptoms of depression and PTSD, which have been associated with alcohol use in this population (Fuehrlein et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2015). Results of this study are expected to inform intervention efforts for young adult veterans by identifying behavioral patterns that increase risk of alcohol problems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Participants were young adults aged 18 to 34 years who were recruited using targeted Facebook ads as part of a larger randomized controlled trial (Pedersen, Parast, Marshall, Schell, & Neighbors, 2017). Eligibility criteria included (a) being a U.S. veteran currently separated from active duty, (b) being between ages 18 to 34 years, and (c) scoring 3/4+ (for women/men) on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993). Overall, 784 past-year drinkers completed the baseline survey online from remote locations and were randomized to either the online intervention (n = 388) or an attention control condition (n = 396). A total of 622 participants (79% follow-up rate) completed the one-month follow-up survey online and were included in analyses for this study. Details regarding recruitment procedures, sample characteristics, and intervention outcomes have been published elsewhere (Pedersen, Naranjo, & Marshall, 2017; Pedersen, Parast, et al., 2017). All procedures were approved by the institutional review board.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic information

Participants responded to questions regarding their age, gender, race, ethnicity, and branch of service at baseline. An 11-item scale was used to assess combat exposure and severity (Schell & Marshall, 2008). Participants responded (yes/no) if they had been exposed to combat during deployment. They then indicated (yes/no) if they had experienced each of 11 potential combat situations (e.g., “engaging in hand-to-hand combat”). Responses were summed to indicate combat severity, with possible total scores ranging from 0 to 11.

2.2.2. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) screen

Participants completed the 20-item PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013) at baseline and one-month follow-up, indicating the extent to which they had been bothered by symptoms such as “trouble remembering important parts” of a stressful experience in the past month. Response options ranged from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely), with possible total scores ranging from 0 to 80. Participants scoring ≥33 (Bovin et al., 2015) were classified as screening positive for PTSD. The PCL-5 has demonstrated good reliability and convergent and divergent validity in samples of veterans (Bovin et al., 2016), and reliability in this sample was high (α = .98).

2.2.3. Depression screen

Participants self-reported symptoms of depression on the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8; Kroenke et al., 2009) at baseline and one-month follow-up. Specifically, they indicated how frequently in the past two weeks they had been bothered by symptoms such as “poor appetite or overeating.” Response options ranged from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), with possible total scores ranging from 0 to 24. Participants scoring ≥10 (Kroenke et al., 2009) were classified as screening positive for depression. Internal consistency of items in this sample was high (α = .93).

2.2.4. Drinks per week

Participants reported their drinking quantity in a typical week at baseline and follow-up using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). On a seven-day grid, they indicated how many drinks they had consumed on each day of a typical week in the past month. Responses were summed to calculate drinks per week.

2.2.5. Insomnia screen

Participants reported symptoms of insomnia only at one-month follow-up. The Insomnia Severity Index (Morin, Belleville, Belanger, & Ivers, 2011) was used to assess insomnia severity in the past two weeks. Seven items assessed difficulty falling or staying asleep, satisfaction with current sleep pattern, interference with daily functioning, the extent to which others notice their sleep problems, and worry/distress related to sleep problems. Response options ranged from 0 (e.g., not at all worried) to 4 (e.g., very much worried), with possible total scores ranging from 0 to 28. Participants scoring ≥10 were classified as screening positive for insomnia (Morin et al., 2011). Reliability of items in this sample was high (α = .93).

2.2.6. Alcohol-related consequences

The 24-item Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (Kahler, Hustad, Barnett, Strong, & Borsari, 2008; Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005) was used to estimate the number of alcohol-related consequences participants had experienced in the past 30 days both at baseline and follow-up. Participants indicated (yes/no) if they had experienced consequences such as saying/doing embarrassing things, taking foolish risks, drinking on nights they had planned not to drink, and passing out from drinking in the past month. Possible total scores ranged from 0 to 24. This measure has been used widely in studies of young adult drinking behavior, in college student (Merrill, Read, & Barnett, 2013), non-student (Lau-Barraco, Braitman, Stamates, & Linden-Carmichael, 2016), and military samples (Miller, Brett, et al., 2016; Pedersen, Parast, et al., 2017). Internal consistency in this sample was high (α = .94).

2.3. Data Screening and Analysis

All measures and data collected for the present analyses utilized cross-sectional data from the one-month follow-up survey. Data were screened for missing values, normality, and baseline differences between intervention and control conditions prior to analysis. Two participants were missing one-month data on drinks per week and insomnia variables; thus, these individuals were dropped from analyses. Skewness and kurtosis estimates for predictor and outcome variables were within the acceptable range (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). At baseline, there were no significant differences between groups in age, gender, drinks per week, or alcohol-related consequences. Because participants in the intervention condition reported significantly greater decreases in alcohol use outcomes than those in the control condition (Pedersen, Parast, et al., 2017), intervention condition was included as a covariate in all analyses. Analyses also controlled for gender, age, combat severity, PTSD, and depression, all of which have been associated with alcohol use in military and veteran samples (Bray, 2013; Fuehrlein et al., 2014; Scott et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2015). Primary outcome analyses were conducted using hierarchical regression. Specifically, covariates, drinks per week, and insomnia severity were modeled as predictors of alcohol-related consequences in Step 1. The two-way interaction evaluating insomnia screen as a moderator of the association between drinks per week and alcohol-related consequences (drinks per week × insomnia screen) was added in Step 2. For graphing purposes, all participant drinks per week data were plotted one standard deviation above (+13.5) and one standard deviation below (−13.5) the mean. Follow-up tests of simple slopes were then conducted to determine the significance of the association between drinks per week and alcohol-related consequences at high and low levels of the moderator (Aiken & West, 1991; Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). High and low values of insomnia were specified as a positive versus negative insomnia screen, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Participants in this study were primarily men (82.6%) with a mean age of 29.0 years (SD = 3.4) who reported drinking in the past year (N = 622). The majority of participants were White (84.6%), followed by bi/multiracial (6.1%), African American (4.2%), American Indian or Alaskan Native (2.1%), Asian (1.3%), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (0.5%), and other (1.1%). They were affiliated with four branches of service: Army (58.4%), Marines (21.5%), Air Force (10.8%), and Navy (9.3%). On average, participants reported 4.0 (SD = 3.1) combat experiences. Approximately one in three participants screened positive for PTSD (31.4%) and depression (34.6%), and more than half screened positive for insomnia (61.6%). They reported consuming 11.5 (SD = 13.5) standard drinks in a typical week and experiencing 4.5 (SD = 6.0) alcohol-related consequences in the past month.

3.2. Primary outcomes

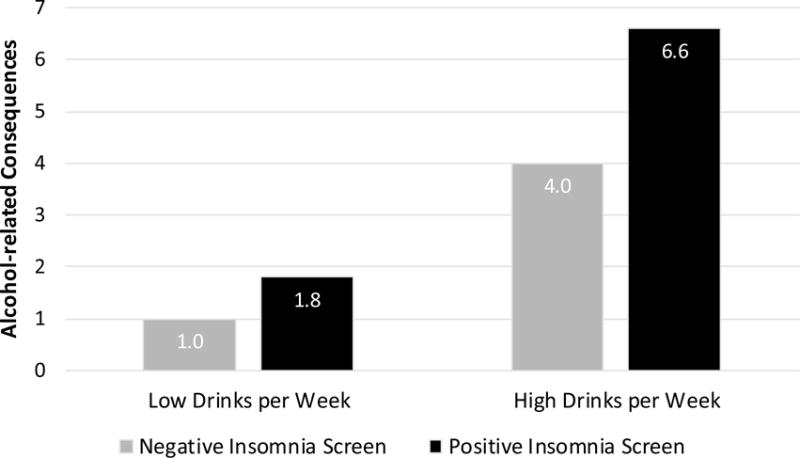

Drinks per week and a positive insomnia screen were concurrent predictors of alcohol-related consequences (see Table 1). Specifically, a one-unit increase in drinks per week was associated with .45 more alcohol-related consequences (p < .001), and a positive insomnia screen was associated with .13 more alcohol-related consequences (p < .001). Consistent with hypotheses, the interaction between drinks per week and insomnia was a significant predictor of alcohol-related consequences. Tests of simple slopes indicated that a positive (β = 0.50, SE = 0.02, p < .001) versus negative (β = 0.35, SE = 0.03, p < .001) insomnia screen strengthened the positive association between drinking quantity and alcohol-related consequences (see Figure 1).

Table 1.

Main effects and interaction term in prediction of alcohol-related consequences (N = 622).

| b | SE | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Step 1: Main Effects | |||||

| Intercept | 2.05 | .61 | – | 3.36 | – |

| Intervention condition | 0.59 | .39 | 0.05 | 1.51 | .13 |

| Male gender | 0.07 | .53 | 0.005 | 0.14 | .89 |

| Age | −0.13 | .06 | −0.07 | −2.15 | .03 |

| Combat severity | 0.004 | .07 | 0.002 | 0.06 | .95 |

| Positive PTSD screen | 1.41 | .55 | 0.11 | 2.56 | .01 |

| Positive depression screen | 1.84 | .54 | 0.15 | 3.42 | <.001 |

| Drinks per week | 0.20 | .01 | 0.45 | 13.29 | <.001 |

| Positive insomnia screen | 1.65 | .46 | 0.13 | 3.58 | <.001 |

| Step 2: Interaction | |||||

| Drinks per week × insomnia screen | 0.07 | .03 | 0.13 | 2.00 | .046 |

Figure 1.

Group differences in the insomnia by drinks per week interaction on alcohol-related consequences.

4. Discussion

This study contributes uniquely to the literature by documenting interactive effects between insomnia and drinking quantity in the concurrent prediction of alcohol-related consequences among young adult veterans. Consistent with cross-sectional and longitudinal findings in college students (Kenney et al., 2012; Miller, DiBello, et al., 2016), drinking quantity was associated with more alcohol-related consequences in the context of clinically significant symptoms of insomnia. Moreover, this moderation effect was observed independent of other established predictors of alcohol consequences, such as age, PTSD, and depression. Nearly two-thirds of this sample of past-year drinkers screened positive for insomnia. Thus, symptoms of insomnia are not only common among young adult veterans who drink but may also increase the likelihood that they experience alcohol-related problems.

While the association between sleep parameters and hazardous alcohol use has now been well-established in young adult samples (Kenney et al., 2012; Luxton et al., 2011; Miller, DiBello, et al., 2016; Swinkels et al., 2013), the mechanism(s) underlying this association are unclear. Poor sleep health has been linked to impairments in executive functioning (Alhola & Polo-Kantola, 2007; Benitez & Gunstad, 2012) and negative mood (Harvey, 2011). In turn, both executive functioning (Czapla et al., 2015; Lechner, Day, Metrik, Leventhal, & Kahler, 2016; Peeters et al., 2015) and negative mood (Birrell, Newton, Teesson, & Slade, 2016; Witkiewitz, Bowen, & Donovan, 2011) have been associated with subsequent alcohol use. Thus, insomnia symptoms may impact alcohol use in part as a result of poor cognitive or emotional control. The causal nature of these hypothesized mechanisms should be confirmed to determine the extent to which improvements in sleep may decrease risk of heavy drinking and alcohol-related consequences within this population.

Data for this study were collected from a large sample of high-risk young adults. However, we acknowledge several study limitations. First, data utilized in the current study were collected concurrently; therefore, future studies are needed to determine the extent to which the interactive effect between drinking and insomnia endures over time. Second, our models examining the impact of insomnia on alcohol-related consequences are confounded by the fact that alcohol use may also impact sleep parameters (Van Reen et al., 2016; Van Reen, Rupp, Acebo, Seifer, & Carskadon, 2013). Given the bidirectional associations between alcohol use and insomnia symptoms, additional research documenting the nature and directionality of these effects is needed. Third, although the measures used in this study are standard in research and clinical settings and have been validated for use in community samples (Morin et al., 2011; Simons, Wills, Emery, & Marks, 2015), data regarding alcohol use and symptoms of insomnia were collected using self-report. Finally, participants in this trial were primarily men of European descent; thus, findings should be replicated in more diverse samples.

These results suggest that insomnia compounds risk for alcohol-related consequences among young adults who drink. Specifically, the effect of drinking on alcohol-related consequences is stronger in the presence of a positive versus negative screen for insomnia. Research is needed to determine the mechanism(s) by which insomnia impacts risk for alcohol-related consequences among young adults and the extent to which improvements in insomnia may mediate changes in alcohol-related problems. Given the prevalence and consequences of insomnia among young adult veterans, research examining the extent to which insomnia treatment improves alcohol-related outcomes within this population is also warranted.

Highlights.

Approximately two out of three participants screened positive for insomnia.

Insomnia was associated with increased risk of alcohol problems.

Drinking was associated with more problems for those with positive insomnia screens.

Insomnia may be an appropriate target for alcohol prevention and intervention.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

This research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant numbers R34-AA022400, PI Pedersen; T32-AA007459, PI Monti). NIH had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Author ERP designed the study, wrote the protocol, and implemented the research plan. Author MBM generated the research question, with input from AMD, KBC, and ERP. Author AMD conducted the statistical analysis. Author MBM wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alhola P, Polo-Kantola P. Sleep deprivation: Impact on cognitive performance. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2007;3:553–567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlas FM, Higgins WB, Pflieger JC, Diecker K. 2011 Health Related Behaviors Survey of Active Duty Military Personnel. Fairfax, VA: 2013. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Benitez A, Gunstad J. Poor sleep quality diminishes cognitive functioning independent of depression and anxiety in healthy young adults. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2012;26:214–223. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2012.658439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell L, Newton NC, Teesson M, Slade T. Early onset mood disorders and first alcohol use in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;200:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in Veterans. Psychological Assessment. 2015 doi: 10.1037/pas0000254. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in Veterans. Psychological Assessment. 2016;28:1379–1391. doi: 10.1037/pas0000254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM. Substance use in the US active duty military. In: Moore BA, Barnett JE, Moore BA, Barnett JE, editors. Military psychologists’ desk reference. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Brown JM, Williams J. Trends in binge and heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems, and combat exposure in the U.S. military. Substance Use & Misuse. 2013;48:799–810. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.796990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czapla M, Simon JJ, Friederich H, Herpertz SC, Zimmermann P, Loeber S. Is binge drinking in young adults associated with an alcohol-specific impairment in response inhibition? European Addiction Research. 2015;21:105–113. doi: 10.1159/000367939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink DS, Gallaway MS, Tamburrino MB, Liberzon I, Chan P, Cohen GH, Galea S. Onset of alcohol use disorders and comorbid psychiatric disorders in a military cohort: Are there critical periods for prevention of alcohol use disorders? Prevention Science. 2016;17:347. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0624-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier-Brochu E, Morin CM. Cognitive impairment in individuals with insomnia: Clinical significance and correlates. Sleep. 2014;37:1787–1798. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuehrlein B, Ralevski E, O’Brien E, Jane JS, Arias AJ, Petrakis IL. Characteristics and drinking patterns of veterans with alcohol dependence with and without post-traumatic stress disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG. Sleep and circadian functioning: Critical mechanisms in the mood disorders? Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2011;7:297–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Hustad J, Barnett NP, Strong DR, Borsari B. Validation of the 30-day version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire for use in longitudinal studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:611–615. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward Efficient and Comprehensive Measurement of the Alcohol Problems Continuum in College Students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Pham AT. Global sleep quality as a moderator of alcohol consumption and consequences in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;114:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau-Barraco C, Braitman AL, Stamates AL, Linden-Carmichael AN. A latent profile analysis of drinking patterns among nonstudent emerging adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;62:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner WV, Day AM, Metrik J, Leventhal AM, Kahler CW. Effects of alcohol-induced working memory decline on alcohol consumption and adverse consequences of use. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233:83–88. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luxton DD, Greenburg D, Ryan J, Niven A, Wheeler G, Mysliwiec V. Prevalence and impact of short sleep duration in redeployed OIF soldiers. Sleep: Journal of Sleep and Sleep Disorders Research. 2011;34:1189–1195. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP, Barnett NP. The way one things affects the way one drinks: Subjective evaluations of alcohol consequences predict subsequent change in drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:42–51. doi: 10.1037/a0029898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Brett EI, Leavens EL, Meier E, Borsari B, Leffingwell TR. Informing alcohol interventions for student service members/Veterans: Normative perceptions and coping strategies. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;57:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, DiBello AM, Lust SA, Carey MP, Carey KB. Adequate sleep moderates the prospective association between alcohol use and consequences. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;63:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep: Journal of Sleep and Sleep Disorders Research. 2011;34:601–608. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Naranjo D, Marshall GN. Recruitment and retention of young adult veteran drinkers using Facebook. PLOS One. 2017;12:e0172972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Parast L, Marshall GN, Schell TL, Neighbors C. A randomized controlled trial of a web-based, personalized normative feedback alcohol intervention for young-adult veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2017;85:459–470. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters M, Janssen T, Monshouwer K, Boendermaker W, Pronk T, Wiers RW, Vollebergh WAM. Weaknesses in executive functioning predict the initiating of adolescents’ alcohol use. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2015;16:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell TL, Marshall GN. Survey of individuals previously deployed for OEF/OIF. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scott JC, Pietrzak RH, Mattocks K, Southwick SM, Brandt C, Haskell S. Gender differences in the correlates of hazardous drinking among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;127:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Wills TA, Emery NN, Marks RM. Quantifying alcohol consumption: Self-report, transdermal assessment, and prediction of dependence symptoms. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;50:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels CM, Ulmer CS, Beckham JC, Buse N, Calhoun PS. The association of sleep duration, mental health, and health risk behaviors among U.S. Afghanistan/Iraq Era veterans. Sleep: Journal of Sleep and Sleep Disorders Research. 2013;36:1019–1025. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th. New York, NY: Haper and Row; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van Reen E, Roane BM, Barker DH, McGeary JE, Borsari B, Carskadon MA. Current alcohol use is associated with sleep patterns in first-year college students. Sleep. 2016;39:1321–1326. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Reen E, Rupp TL, Acebo C, Seifer R, Carskadon MA. Biphasic effects of alcohol as a function of circadian phase. Sleep. 2013;36:137–145. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) Boston, MA: National Center for PTSD; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Williams EC, Frasco MA, Jacobson IG, Maynard C, Littman AJ, Seelig AD, Boyko EJ. Risk factors for relapse to problem drinking among current and former US military personnel: A prospective study of the Millennium Cohort. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;148:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Bowen S, Donovan DM. Moderating effects of a craving intervention on the relation between negative mood and heavy drinking following treatment for alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:54–63. doi: 10.1037/a0022282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]