Abstract

The factors affecting plant uptake of heavy metals from metalliferous soils are deeply important to the remediation of polluted areas. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), soil-dwelling fungi that engage in an intimate exchange of nutrients with plant roots, are thought to be involved in plant metal uptake as well. Here, we used a novel field-based approach to investigate the effects of AMF on plant metal uptake from soils in Palmerton, PA, USA contaminated with heavy metals from a nearby zinc smelter. Previous studies often focus on one or two plant species or metals, tend to use highly artificial growing conditions and metal applications, and rarely consider metals’ effects on plants and AMF together. In contrast, we examined both direct and AMF-mediated effects of soil concentrations on plant concentrations of 8–13 metals in five wild plant species sampled across a field site with continuous variation in Zn, Pb, Cd, and Cu contamination. Plant and soil metal concentration profiles were closely matched despite high variability in soil metal concentrations even at small spatial scales. However, we observed few effects of soil metals on AMF colonization, and no effects of AMF colonization on plant metal uptake. Manipulating soil chemistry or plant community composition directly may control landscape-level plant metal uptake more effectively than altering AMF communities. Plant species identities may serve as highly local indicators of soil chemical characteristics.

Keywords: Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, heavy metals, hyperaccumulation, Lehigh Gap Nature Center, Palmerton Zinc Superfund Site, plant-soil feedback, pollution, restoration, soil chemistry

Introduction

Heavy metal pollution is a global phenomenon with widespread effects on diverse ecosystems and people who depend on them. Plant uptake of metals from contaminated soils is a key step in a metal’s pathway from the soil to the aboveground ecosystem, from where it can be mobilized to organisms at upper trophic levels including humans (e.g. Croteau et al. 2005). Understanding the factors affecting plant metal uptake is crucial to remediating contaminated sites effectively, whether plants are used to remove pollutants (phytoextraction) or to sequester them in place (phytostabilization; Pilon-Smits 2005). Plant metal uptake also has important implications for agriculture, especially the rising urban agriculture movement, in which many social, ecological, and public health benefits rely on safely growing crops in often-polluted urban soils (Romic and Romic 2003; EPA 2011). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), obligate symbionts associated with a large majority of plant species, live at the interface between plants and soils, and may have important positive or negative effects on plant metal uptake by numerous mechanisms (reviewed by Alford et al. 2010; Miransari 2010). However, the current literature does not yet support a general understanding of how AMF may affect plant metal uptake in the field.

Heavy metals can have toxic effects on plants, adversely affecting their fitness (Lin and Aarts 2012). Mechanisms include metal ions substituting for chemically similar metals as cofactors in enzymes, generating reactive oxygen species, or interfering with the uptake of chemically similar micronutrients (Brady et al. 2005; Bothe et al. 2010). Even metals which are essential nutrients can be toxic in sufficiently large concentrations (Broadley et al. 2007). However, some plants, considered metallophytes, appear adapted to elevated soil metal concentrations. For instance, some endemic species grow only where stress associated with naturally metalliferous serpentine soils reduces competition with other species that would otherwise outcompete them (Brady et al. 2005). Plants may use several metal tolerance strategies, including hyperaccumulating or excluding metals (Baker 1981), and they have diverse cellular and molecular strategies for alleviating metal toxicity or bioavailability in the soil (Bothe et al. 2010).

Soil metals may have similar direct effects on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), although fungal nutrition is generally less well studied than plant nutrition. Some essential metals such as Zn become toxic only at elevated concentrations, and others such as Pb or Cd have no known biological function and can be toxic at any concentration (Bothe et al. 2010). Biochemical mechanisms of metal toxicity to fungi are likely similar to those in plants, although of course specific metals, enzymes, and other cellular components involved vary, as do toxicity thresholds (del Val et al. 1999a,b). Field studies investigating effects of soil metals on AMF are rare and give inconsistent results: elevated soil metals decrease AMF colonization in some field systems (Khan 2001), and increase it in others (Vogel-Mikuš et al. 2006). Like plants, fungi may tolerate metal stress by limiting uptake of nonessential metals, or by sequestering metals in cell walls or intracellular compartments where they are less likely to induce toxicity (Weiersbye et al. 1999). Fungi can also produce exudates that chelate or bind metals, affecting their mobility and availability in the soil (Bothe et al. 2010).

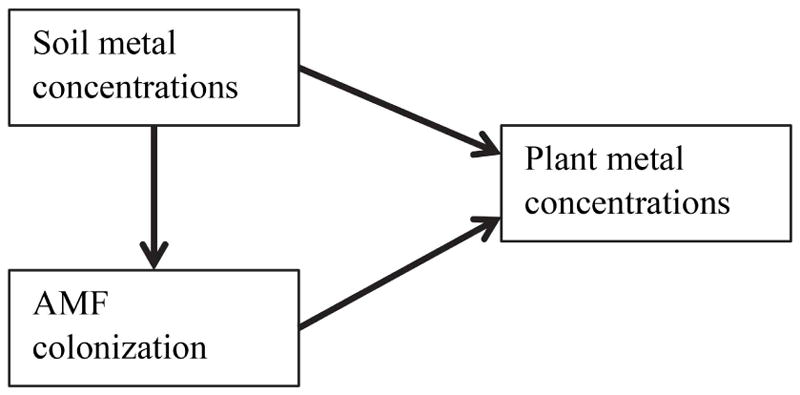

To better understand the effects of metals on plant-AMF systems, we must consider plant and fungal responses together, as soil metals may affect plants directly or via their mycorrhizae (Fig. 1). Numerous mechanisms have been proposed for how AMF may affect plant metal uptake, including reducing plant uptake by altering soil metal bioavailability or sequestering metals in their own tissues, or increasing plant uptake by actively translocating metals into plants through pathways presumably evolved for nutrient transfer (reviewed by Schützendübel and Polle 2002; Göhre and Paszkowski 2006; Miransari 2011, Ferrol et al. 2016). If AMF colonization decreases plant metal uptake, then AMF would be expected to alleviate plant metal toxicity. Alternatively, if colonization increases plant metal uptake, then AMF could exacerbate plant metal toxicity. AMF colonization effects on plant metal uptake also need not be linear (Audet and Charest 2007, Ferrol et al. 2016).

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of the relationships examined in this study. Soil metal concentrations may relate to plant metal concentrations directly, or indirectly via mycorrhizal fungal colonization.

Numerous studies have investigated the effects of AMF on plant metal uptake, however, these studies are almost invariably greenhouse experiments using just one or two plant species, AMF inocula, and metals, often in highly artificial growing conditions. This approach is difficult to generalize to field conditions, in which many different plant species, AMF species, and metals interact simultaneously. Indeed, in different systems, these greenhouse studies have found that AMF increase (Chen et al. 2005; Orłowska et al. 2013), decrease (Abdel Aziz et al. 1997; Jiang et al. 2016), have mixed effects (Weissenhorn et al. 1995; Wang et al. 2007), or have no effects (Tonin et al. 2001; Lagrange et al. 2013) on plant metal uptake. It is difficult to synthesize these disparate results across diverse plant-metal systems, and most of them do not take into account the possibility that soil metals affect plants both directly and indirectly via AMF. Thus, we still lack an understanding of general principles governing plant-AMF-metal interactions in the field.

Here, our approach takes into account that soil metal concentrations could affect plant metal concentrations either directly by root uptake, or indirectly via effects on AMF colonization (Fig. 1). Thus, at a site polluted by Zn, Cd, Pb, and Cu, and for five different plant species, we examine the following specific relationships: soil metal concentrations and plant metal concentrations, soil metal concentrations and AMF colonization, and AMF colonization and plant metal concentrations (Fig. 1). Our five plant species represent three families, including the Caryophyllaceae, which is relatively enriched in metal hyperaccumulators and non-mycorrhizal species, as well as the Asteraceae and Poaceae, which are more typical in this regard (Hildebrandt et al. 2007). We improve on the generality of other studies by (1) sampling wild plants and AMF that spent their entire lives in the field, (2) examining taxonomically diverse species under similar environmental conditions, (3) using continuous variation in soil metal concentrations and AMF colonization rather than single doses of either, and (4) analyzing soil and plant concentrations of many metals simultaneously. We aim to better understand how plants, AMF, and soil metals interact in field conditions where they are most relevant.

Our approach also afforded us the opportunity to explore the spatial distribution of soil metal contamination more thoroughly than has yet been done in our study site. Previous researchers working on larger geographic scales have suggested that contamination in the region follows a gradient decreasing away from the source, a pair of zinc smelters (Buchauer 1973; Johnson and Richter 2010; Glassman and Casper 2012). However, the spatial distribution of contamination in the site has not yet been characterized at smaller (sub-kilometer) scales despite its relevance to local remediation, plant community composition, and our understanding of the behavior of metals in the environment. We sought to test the existence of this contamination gradient, and to compare the extent to which physical proximity and plant species identity account for variation in soil chemistry.

Methods

Study site

We collected samples on the north facing slope of Blue Mountain just west of Lehigh Gap in Carbon County, PA, USA, on lands owned and managed by the Lehigh Gap Nature Center (LGNC) and the National Park Service (NPS). This area constitutes the western portion of the Palmerton Zinc Superfund Site, a >2000 acre area of mountainside severely contaminated and devegetated due to airborne Zn, Cd, Pb, Cu, and SOx emissions from two zinc smelters operating upwind between 1898–1980 (Buchauer 1973; EPA 2007). Deposition of smelting emissions is thought to have produced a gradient of soil heavy metal contamination, with concentrations in our sampling area predicted to increase northward and eastward toward the smelters (Buchauer 1973; Johnson and Richter 2010; Glassman and Casper 2012). However, the distribution of soil metal contamination within the site has not yet been characterized.

Study species

Remediation efforts began in 2003 with the seeding of a suite of C4 grasses, which now dominate much of the site. However, to extend the generality of our study to contaminated sites regardless of management strategy, we chose to focus on species that were not planted. Thus, we sampled 15–30 individuals each of three forbs: Minuartia patula (Caryophyllaceae), Ageratina altissima (Asteraceae), Eupatorium serotinum (Asteraceae), and two C3 grasses, Agrostis perennans (Poaceae) and Deschampsia flexuosa (Poaceae) (Rhoads and Block 2007). All are abundant and distributed widely across the expected contamination gradient. Of these, M. patula, A. perennans, and D. flexuosa were documented in the site well before remediation began (Pretz 1954; Jordan 1975). We have found no records of A. altissima or E. serotinum in the site before remediation, so we do not know when they arrived on the mountain.

We collected samples along two hiking trails, the North Trail and the LNE Trail, which served as approximately east-west transects across the upper and lower slopes of the mountain, respectively. Along both trails, we established sampling locations at least 50 m apart and at least 5 m from the trail where we found at least two target species growing within 10 m of each other; we recorded the GPS coordinates of each location. When possible, we sampled more than two species, and up to two individuals per species, at each sampling location, in order to document both fine-scale and large-scale variation in soil characteristics. In one sampling location where D. flexuosa was especially abundant, we made an exception and collected five individuals of that species. For each individual plant sampled, we collected aboveground tissue and rooting soil for elemental analysis, and roots for AMF colonization. Soil and roots were collected from the top 15 cm of soil. Trowels used to collect soil and roots were washed thoroughly between samples to prevent cross-contamination. All samples were stored at 4 °C upon returning to lab until they could be processed further.

AMF colonization

In the lab, roots were separated from soil, cleaned in tap water, placed in plastic cassettes and stored in water at 4 °C until staining. Roots were then cleared in hot 10% KOH (6 min), bleached in room temperature 1:10 household ammonia: household H2O2 (2 min), acidified in room temperature 5% HCl (10–20 min), and stained in hot 0.1% trypan blue in 1:1:1 water: lactic acid: glycerol (5 min). At least 10 1-cm long root segments were mounted on a microscope slide, fixed with polyvinyl lactic acid glycerol, and cured at 60 °C for at least 48 h (INVAM 2014). Percent colonization was measured by recording the presence or absence of AMF structures at intersections spaced 1 mm apart on each root segment (McGonigle et al. 1990). We considered blue-staining hyphae without septa, as well as any associated vesicles and arbuscules, to be AMF structures. While the goal was to record presence or absence of AMF at 100 intersections per slide, we were frequently unable to do so, most commonly because of missing root cortex, dark background staining, or abundant non-mycorrhizal structures obscuring our view. In our analyses, we included data only from samples with more than 30 intersections.

Plant and soil metal concentrations and integrative soil variables

We measured metal concentrations of plant aboveground tissue and both total extractible and exchangeable metal concentrations of soils. Total extractible soil metal concentrations, measured after US EPA method 3050B, are close to the samples’ total metal concentrations (Brümmer 1986). Exchangeable soil metal concentrations, measured after ISO method 23470, are less than total extractible concentrations and represent amounts a plant may encounter on shorter time scales from the soil solution or via cation exchange (Brümmer 1986). Because total extractible and exchangeable soil metal concentrations may behave very differently (Remon et al. 2013), we analyzed both to better understand the soil chemical factors affecting AMF colonization and plant metal uptake.

Plant aboveground tissue used for elemental analysis was washed thoroughly with tap water, oven-dried at 60 °C for at least 48 h until constant weight, and ground using mortar and pestle with liquid nitrogen before digestion. Soils were sieved to 2 mm, air-dried for at least one week, and stored in sealed plastic bags before digestion.

Plant metal concentrations and total extractible soil metal concentrations were measured as follows. Samples were weighed into ceramic crucibles, covered, ashed at 475 °C for at least 4 h, allowed to cool, and weighed again to estimate organic matter content by loss on ignition (LOI). Ashed samples were digested in 2 mL concentrated HCl at 90–100 °C for 10 min, diluted to 25 mL with deionized water, and stored at 4 °C until their metal concentrations could be measured. In each batch of samples we digested, we included a reagent blank as well as two standard reference materials, peach leaves (NIST 1547) and either olive leaves (BCR 062) or citrus leaves (NIST 1572), to check the quality of the digest. From these digest solutions, we measured plant and total extractible soil metal concentrations of the contaminants Zn, Pb, Cd, and Cu, the macronutrients Ca, Mg, and K, and the micronutrients Ni and Mn with a Spectro Genesis inductively coupled plasma optical emissions spectrometer (ICP-OES) (Spectro Analytical Instruments GmbH, Kleve, Germany). In each ICP-OES run, digested experimental samples and standard reference materials were interspersed with standard solutions containing known concentrations of each element to ensure the quality of the run.

For the subset of samples for which we had sufficient soil remaining after measuring total extractible metal concentrations, we also measured exchangeable soil metal concentrations and the integrative soil variables pH, cation exchange capacity (CEC), and base saturation. We measured soil pH in a 1:5 soil: water ratio (ISO 2005). We used cobaltihexammine extraction (ISO 2007) to determine CEC at soil pH, and to determine the exchangeable concentrations of soil Ca, K, Mg, Na, Al, Fe, Mn, Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Zn by ICP-OES.

Statistical analysis

Plant and soil element concentrations were log10-transformed before analysis to improve normality. We removed total extractible soil Mn from relevant analyses including D. flexuosa because of insufficient usable measurements, and we removed exchangeable soil Cu, Ni, Fe, and Cr from all analyses because they were consistently below the detection limit of the ICP-OES. After measuring total extractible metal concentrations, we did not consistently have enough soil from under D. flexuosa to measure exchangeable metal concentrations and integrative soil variables, so we removed this species from all analyses including the latter variables.

We used a combination of principal components analysis (PCA) and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to investigate the effects of soil metal concentrations on AMF colonization, and of soil metal concentrations and AMF colonization on plant aboveground metal concentrations. We used MANOVA rather than univariate ANOVAs to take advantage of the correlation structure of both the plant and soil metal concentration datasets, and to test for effects of predictor variables on plant concentrations of all metals measured simultaneously.

We used separate MANOVA models to examine the effects of total extractible and exchangeable soil metal concentrations on AMF colonization separately and with maximal sample size (Table 1). First, we considered exchangeable metal concentrations, the integrative soil variables pH, CEC, and base saturation, and plant species identity as predictor variables, and AMF colonization as the response variable. To allow the testing of interactions between predictors, we used PCA to reduce the dimensionality of exchangeable metal concentrations and integrative soil variables, and then tested the effects of the first two PCA axes, plant species identity, and their interactions on AMF colonization (Table 1A, first row). Because no interactions of soil parameter PCA axes with plant species identity were significant, we then performed a second MANOVA to identify which soil parameters were driving significant effects. In this model, we tested the main effects of plant species and all individual soil exchangeable metal concentrations and integrative soil variables on AMF colonization, but omitted all interactions because of the large number of predictor variables (Table 1A, second row). We used a similar approach to test the interactive effects of total extractible metal concentrations and plant species identity on AMF colonization (Table 1A, third and fourth rows).

Table 1.

MANOVA model formulation and significant predictors of (A) AMF colonization and (B) plant metal uptake. Models are specified as “Response ~ Predictor 1 * Predictor 2 * …” or “Response ~ Predictor 1 + Predictor 2 + …”, where * indicates the testing of both main effects and interactions and + indicates the testing of main effects only. Model terms are abbreviated as follows: Plant, plant metal concentration profiles; AMF, percent root colonization by AMF; Tot, total extractible soil metal concentrations; Exch, exchangeable soil metal concentrations; Int, integrative soil variables (pH, CEC, and base saturation); Species, plant species identity; PCexch1 and PCexch2, first and second axes of a PCA of exchangeable soil metal concentrations and integrative soil variables; PCtot1 and PCtot2, first and second axes of a PCA of total extractible soil metal concentrations. Significant soil metal concentrations are notated either XX.tot or XX.exch, where XX is the chemical symbol of the relevant element. Significant interactions are notated with colons.

| A | |

|---|---|

| Model | Significant terms |

| AMF ~ PCexch1 *PCexch2 *Species | PCexch1 * |

| AMF ~ Exch + Int + Species | Zn.exch * |

| AMF ~ PCtot1 *PCtot2 *Species | Species ** |

| AMF ~ Tot + Species | Cu.tot * |

| B | |

|---|---|

| Model | Significant terms |

| Plant ~ PCexch1 *PCexch2 *Species *AMF | PCexch1 ***, PCexch2 *, Species *** |

| Plant ~ Exch + Int + Species + AMF | Mg.exch ***, Zn.exch **, Species *** |

| Plant ~ PCtot1 *PCtot2 *Species *AMF | PCtot1 ***, PCtot2 ***, Species ***, PCtot1:PCtot2 * |

| Plant ~ Tot + Species + AMF | K.tot *, Pb.tot **, Zn.tot ***, Species *** |

Significance codes:

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

We used the same approach to investigate the effects of soil metal concentrations, plant species identity, and AMF colonization on plant metal concentration profiles. We first modeled multivariate plant metal uptake profiles as a function of plant species identity, AMF colonization, the first two axes of a PCA of exchangeable soil metals and integrative soil variables, and their interactions (Table 1B, first row). Again, there were no significant interactions between soil parameter PCA axes and plant species identity or AMF colonization, so we tested the main effects of all individual soil exchangeable metal concentrations and integrative soil variables, plant species, and AMF colonization, but no interactions, on plant metal uptake profiles (Table 1B, second row) to see which predictors were driving significant results. We repeated this analysis with total extractible soil metals in place of exchangeable soil metals and integrative soil variables (Table 1B, third and fourth rows). Finally, to better understand the consistent effects of plant species identity on AMF colonization and plant metal uptake, we tested for associations between plant species identity and each total extractible and exchangeable metal concentration, integrative soil variable, and AMF colonization using one-way ANOVAs, with the Dunn–Šidák correction for multiple comparisons.

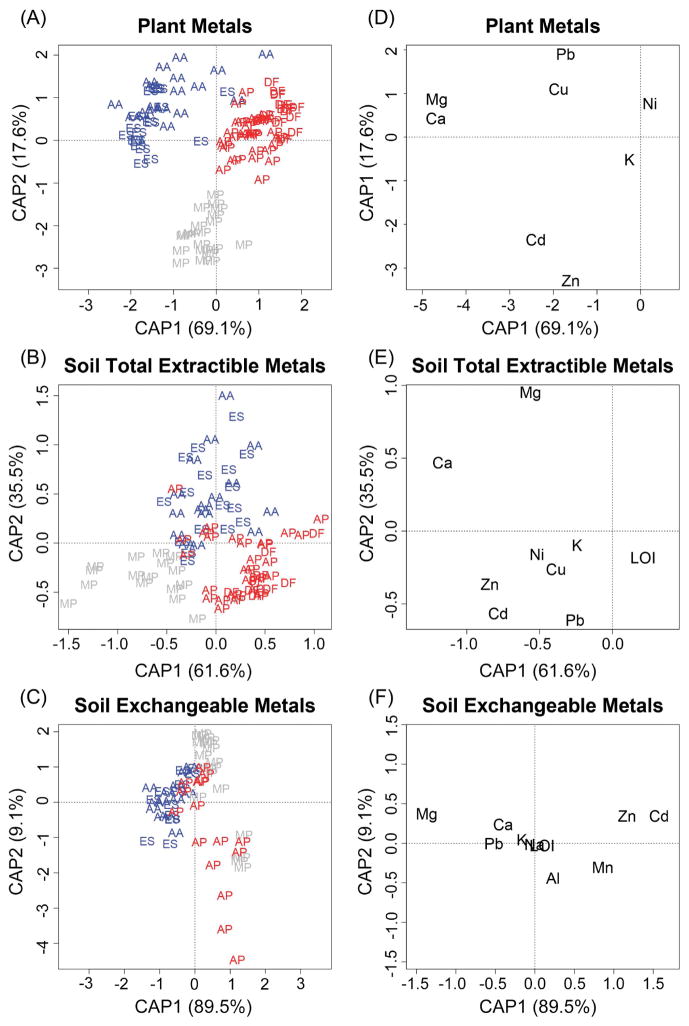

We used constrained analysis of proximities (CAP), a constrained ordination technique (Anderson and Willis 2003), to visualize the relationships between plant species identity and plant and soil chemical characteristics. We used the capscale command in the vegan package in R (Oksanen et al. 2013) to construct CAP models using plant species identity as a predictor of plant metal uptake profiles, soil total extractible chemical profiles, and soil exchangeable chemical profiles, respectively. We used the permutation-based anova.cca method to test the significance of species as a predictor of plant and soil chemistry, and the plot.cca method to visualize the results.

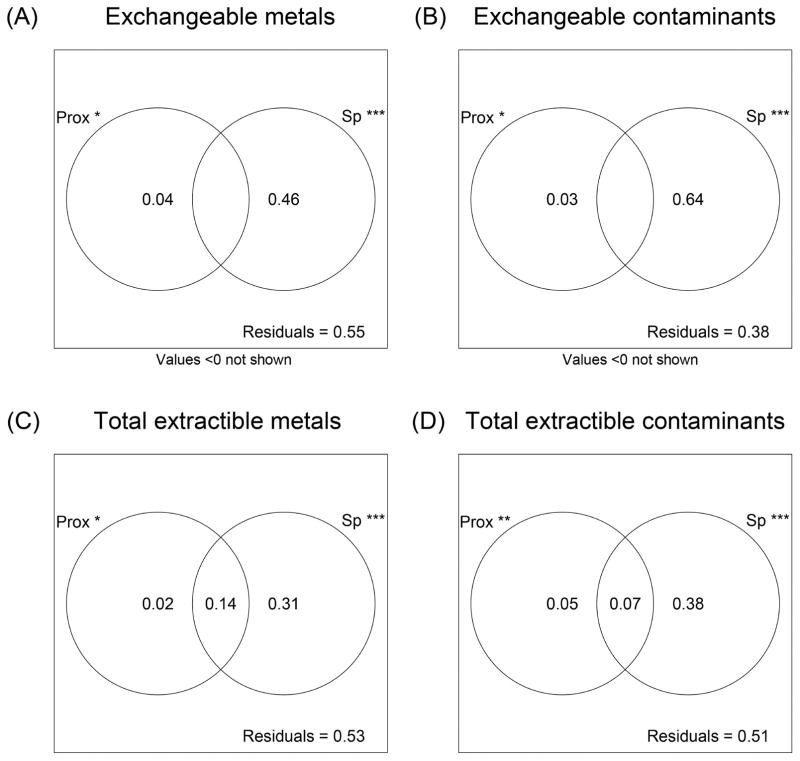

Spatial analysis

We then evaluated the concurrent effects of species identity and location on the mountain on soil metal concentrations. We used redundancy analysis (RDA) in the vegan package in R (Oksanen et al. 2013) to partition observed variance in soil metal concentrations between plant species identity and geographic location of samples, and to test the significance of these two predictors of soil metal concentrations. Because total extractible and exchangeable soil metal concentrations may behave differently, and because metals released by the smelters may be distributed on the mountain differently from metals derived from soil weathering, we performed this analysis using total extractible or exchangeable concentrations of all metals measured, or only the known contaminants Zn, Cd, Pb, and Cu.

Results

Site conditions

Soil and plant chemistry in the Palmerton site was widely variable. Total extractible and exchangeable metal concentrations varied over 1–3 orders of magnitude per element, and plant metal concentrations varied over 1–2 orders of magnitude per element (Fig. 2; Appendix S1: Figs. S1, S2). Root colonization by AMF reached 40% but was below 10% for most samples, and near zero for M. patula (Fig. 3). The integrative soil variables fell between 4.0–7.2 for pH, 1.8–41.6 cmol+/kg for CEC, and 25–104% for base saturation (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Interspecific differences in plant (A–C), soil total extractible (D–F), and soil exchangeable (G–I) concentrations of the primary pollutants Zn (A, D, G), Cd (B, E, H), and Pb (C, F, I). Note that the vertical axes are different for each panel. Species are abbreviated as follows: AA, Ageratina altissima (Asteraceae); AP, Agrostis perennans (Poaceae); DF, Deschampsia flexuosa (Poaceae); ES, Eupatorium serotinum (Asteraceae); MP, Minuartia patula (Caryophyllaceae). Families are color-coded as follows: Asteraceae, blue; Poaceae, red; Caryophyllaceae, gray.

Figure 3.

Interspecific differences in plant root colonization by AMF (A) and in the integrative soil variables pH (B), CEC (C), and base saturation (D). Species and families are abbreviated and color-coded as in Fig. 2.

Soil metal concentrations and AMF colonization

The first axis of our PCA of exchangeable soil metal concentrations and integrative soil variables together accounted for 47.0% of the variation in these parameters. This axis was positively correlated with the contaminants Zn and Cd as well as Mn and Al, and negatively correlated with the base cations Ca, Mg, and K, as well as K, CEC, pH, and base saturation. The second axis accounted for 18.1% of the variation, and was most positively correlated with LOI, weakly positively correlated with all metals measured, and weakly negatively related to base saturation and pH (Appendix S1: Fig. S3A). In the model where these PCA axes, plant species identity, and their interactions were used to predict AMF colonization, the first PCA axis was significantly negatively related to AMF colonization (Table 1A, first row). Analyzing the main effects on AMF colonization of plant species and all of these soil parameters individually on AMF colonization yielded a significant negative effect of soil Zn (Table 1A, second row).

The first axis of our PCA of total extractible soil metal concentrations accounted for 50.9% of the variation in these parameters, and was negatively correlated with all metals measured, most strongly Zn, Cd, and Cu, as well as Ni. The second PCA axis accounted for 22.6% of the variation and was positively related to LOI and Pb, and negatively related to Mg and Ca (Appendix S1: Fig. S3B). In the model where these PCA axes, plant species identity, and all interactions were used to predict AMF colonization, only plant species identity was significant (Table 1A, third row). Analyzing the main effects on AMF colonization of plant species and all soil total extractible metal concentrations individually yielded a significant negative effect of soil Cu (Table 1A, fourth row).

Indeed, when we examined the univariate relationships between soil element concentrations and AMF colonization for each element and plant species separately, significant relationships were few and weak. Only E. serotinum samples had any significant relationships between total extractible soil metals and AMF colonization (negative relationships with Cu, Mn, Ni, and Pb, and positive relationship with Mg). For exchangeable metals and integrative soil variables, AMF colonization was in A. ageratina positively related to base saturation, in E. serotinum negatively related to exchangeable Zn, and in M. patula negatively related to exchangeable Mn. However, among all of these relationships, only two had R2 > 0.4 (E. serotinum colonization and total extractible soil Ni, R2 = 0.43, and A. altissima colonization and soil base saturation, R2 = 0.55), and none of them remained significant following the Dunn–Šidák correction for multiple comparisons.

Effects of soil metal concentrations and AMF colonization on plant metal concentrations

Our MANOVA models consistently showed significant effects of soil chemistry and plant species identity on plant metal profiles, but AMF colonization never affected plant metal profiles in any model (Table 1B). Both axes of both respective soil parameter PCAs were significant predictors of plant metal profiles in the models in which they were included, and their interaction was also significant in the case of the total extractible metal PCA. In the models in which we included individual soil metal concentrations rather than representing them by PCA axes, we found soil exchangeable and total extractible Zn, exchangeable Mg, and total extractible K and Pb to be significant predictors of plant metal profiles (Table 1B). Univariate regressions showed total extractible and exchangeable soil Zn to have positive relationships with plant Zn. Total extractible soil Pb, though, had a negative relationship with plant Pb, which appears to be largely driven by interspecific variation (Fig. 2). Soil exchangeable Mg and total extractible K were also positively related to plant Mg and K, respectively.

Species effects

Plant species identity was a highly significant predictor of plant metal concentration profiles, soil total extractible metal profiles, and soil exchangeable metal profiles (CAP; P < 0.001 for each; Fig. 4). Furthermore, when examined by individual ANOVAs, all plant metal concentrations, soil metal concentrations, integrative soil variables, and AMF colonization differed significantly with plant species except for exchangeable soil Na and plant Ni, even after the Dunn–Šidák correction for multiple comparisons (P < 0.00165). As a general rule, soils under M. patula had the highest total extractible and exchangeable concentrations of heavy metals, except that they had relatively low exchangeable Pb. Compared with the other plant species analyzed, M. patula had higher aboveground tissue concentrations of Zn and Cd, but lower concentrations of Pb, Cu, and Ni. The two aster species, A. altissima and E. serotinum, had the greatest leaf Ca, Mg, Cu, and Pb concentrations. These higher concentrations appeared to follow soil concentrations for Ca and Mg but not for Cu. Plant Pb concentrations followed a similar pattern to exchangeable soil Pb but opposite to total extractible soil Pb. The two grasses, A. perennans and D. flexuosa, consistently had the lowest leaf metal concentrations of the species examined, and their soils had the lowest Ca and Mg concentrations and the greatest LOI (Figs. 2, 3; Appendix S1: Figs. S1, S2).

Figure 4.

(A) Plant metal concentration profiles, (B) soil total extractible metal concentration profiles, and (C) soil exchangeable metal concentration profiles each clearly segregate plant species in CAP ordination space (P < 0.001 for each). Species and families are abbreviated and color-coded as in Fig. 2. (D–F) Contributions of individual metal concentrations, LOI, and AMF colonization (D only) to the ordination spaces in (A–C), respectively. Percentages on axis labels show the amount of constrained variation accounted for by individual CAP axes. Species DF does not appear in (C) because of insufficient sample size.

AMF colonization, soil pH, CEC, and base saturation were highest in samples from the asters A. altissima and E. serotinum. AMF colonization was lowest in M. patula and A. perennans. Soil pH and base saturation were lowest under D. flexuosa, with intermediate values associated with A. perennans and M. patula. Soil CEC was lowest under the two grasses (Fig. 3).

Spatial analysis

Of the total extractible and exchangeable soil concentrations of the contaminants Zn, Cd, Pb, and Cu, only total extractible Zn and Cd significantly decreased with distance from the smelter (Fig. 5). However, both of these relationships had R2 < 0.25, indicating that the majority of the variance in soil Zn and Cd concentrations is explained by other factors. RDA showed that plant species identity consistently accounted for far more variation (0.31–0.64) than spatial proximity (0.02–0.05; Fig. 6) even though both factors were significant. The proportion of variance for all parameters not explained by these two factors (i.e. residuals) varied from 0.38 to 0.55 (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Total extractible soil Zn (A) and Cd (B) concentrations decrease significantly with distance to the nearer zinc smelter (Zn: P < 0.001, R2 = 0.249; Cd: P < 0.01, R2 = 0.076), but total extractible Pb and Cu, and exchangeable Zn, Cd, and Pb concentrations do not change with distance to the smelter. Exchangeable Cu was not included in this analysis because most measurements were below the detection limit of the ICP-OES. Points represent individual soil samples, and lines are best-fit lines.

Figure 6.

Proportion of variation in (A) exchangeable metal concentrations, (B) exchangeable contaminant concentrations, (C) total extractible metal concentrations, and (D) total extractible contaminant concentrations accounted for by spatial proximity of soil samples (“Prox”), plant species identity (“Sp”), both, or neither. Variance components within a graph may not sum to 1 due to rounding error or production of small negative variance estimates in the overlap region of the Venn diagram. Negative values here are artifacts of subtraction and do not indicate major problems with the model (Oksanen et al. 2013).

Discussion

Plants and soils in the Palmerton site reflect the site’s history of soil metal contamination and acidification. Compared to the interquartile range of topsoil metal concentrations in the United States (Smith et al. 2013), soils in the Palmerton site are low in Ca and K, similar in Mg and Ni, and high in Zn, Cd, Pb, and Cu. Plant metal concentrations are comparable to metal concentrations of our standard reference materials and the standard reference plant described by van der Ent et al. (2013), except for Zn and Cd for which our samples average 1–3 orders of magnitude higher (Fig. 2; Appendix S1: Figs. S1, S2).

Contrary to our expectations, AMF do not appear to play a major role in the relationships between plant and soil metal concentrations at this site. While a few soil metals appear to affect AMF colonization rate, the relationship may be driven in part by differences among plant species in both AMF colonization and the metal content of their rhizosphere soils. We similarly find no evidence for an effect of AMF colonization rate on plant metal concentrations. Instead, we find that plant metal concentrations are strongly related to plant species identity and soil metal concentrations, which are highly variable even at small spatial scales.

AMF colonization of our study plants responded to only two of the four major contaminants in the site. While soil concentrations of Zn and Cu had the expected negative effect on AMF colonization in one model each, Pb and Cd never significantly affected AMF colonization. We had expected Pb and Cd to be more toxic to AMF than Cu because they occur at similar or greater concentrations than the essential micronutrient Cu (Ding et al. 2014), but have no known biological function in most organisms. However, longtime use of Cu as an agricultural fungicide (Winston et al. 1923) and recent work showing high Cu sensitivity of soil fungi (Klimek and Niklińska 2007) could help explain why Cu is one of the dominant toxins to fungi in the Palmerton site.

Our results from the field contrast with other studies showing relationships between soil metals, AMF, and plant metals. Other studies, largely in greenhouses, have typically found that metals decrease AMF colonization and/or diversity (del Val et al. 1999a,b; Khan 2001; Chen et al. 2005), although Diaz et al. (1996) and Tan et al. (2015) found no effect of applied Zn, Pb, or Cd solutions on AMF colonization of three host plants, and Vogel-Mikus et al. (2006) found that increasing soil Cd and Pb by mixing contaminated and uncontaminated soils in different ratios increased AMF colonization of the hyperaccumulator Thlaspi praecox. Reported effects of AMF colonization on plant metal uptake are similarly inconsistent (e.g. Diaz et al. 1996; Turnau and Mesjasz-Przybylowicz 2003; Chen et al. 2005; Jiang et al. 2016).

Greenhouse experiments with AMF and metals are effective ways to test specific hypotheses, but they fail to produce generalizable principles affecting plant growth in the field. In particular, they bypass germination, which has been shown to be especially sensitive to soil metal concentrations (Bae et al. 2016 and sources therein). They also expose plants to soil metal concentrations and growth environments that may be unrepresentative of field conditions, potentially changing their growth and metal uptake substantially (e.g. Lehmann and Rillig 2014, 2015). A few studies have examined the effects of AMF on plant metal uptake outdoors (Li et al. 2005, Jankong et al. 2007, Cabral et al. 2015 and sources therein), but these studies still bypassed germination and altered growing conditions significantly from what a wild plant would experience. In contrast, our study plants were exposed to soil metals and AMF for their entire lives. Our plants also likely experienced a wider range of environmental conditions, such as temperature and water availability, than most previous studies have allowed. We suggest that one or more components of these more variable, natural conditions may overwhelm the effects of AMF on leaf metal concentrations seen in some greenhouse studies.

It is possible that conditions at our research site serve as an ecological filter favoring species with low AMF reliance or response. Smelting pollution at the site is thought to have reduced the diversity, abundance, and activity of soil dwelling microbes, likely including AMF (Jordan and Lechevalier 1975, Strojan 1978; Latham et al. 2007), so that plants colonizing the site soon after the disturbance may have benefited from low reliance on AMF. This is consistent with our observed AMF colonization rates, which were nonzero but notably reduced from previously recorded values in all of our study species except M. patula, for which the near-zero colonization rates we observed match the literature (Table 2). We also consider the possibility that AMF play important roles in plant-soil metal dynamics in the field, but that root colonization rates do not consistently reflect the strength or function of mycorrhizal symbioses (Smith et al. 2004; Smith and Read 2008). Supporting this idea, Liu et al. (2009) found similar effects of AMF on As uptake by Pteris vittata whether all or just half of the plant’s root system was exposed to AMF.

Table 2.

Measured AMF colonization of our target species at Palmerton is low compared to previously reported colonization data for these species and their close relatives, except for M. patula, which was expected to have near-zero colonization. For method, “magnified intersections” follows McGonigle et al. (1990) and “gridline intersect” follows Giovannetti and Mosse (1980).

| Species | Colonization (%) | Method | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ageratina altissima | 9.1±1.5 | Magnified intersections | Present study |

| Ageratina espinosarum | 0–10 | Unclear | Camargo-Ricalde et al. (2003) |

| Agrostis perennans | 2.4±0.71 | Magnified intersections | Present study |

| Agrostis scabra | 25.7 | Gridline intersect | Titus and Tsuyuzaki (2002) |

| Agrostis scabra | 2.2–55 | Magnified intersections | Bunn et al. (2009) |

| Agrostis stolonifera | 50.0 | Gridline intersect | Pawlowska et al. (1996) |

| Agrostis stolonifera | 32.8 | Gridline intersect | Wilson and Hartnett (1998) |

| Deschampsia flexuosa | 6.0±2.1 | Magnified intersections | Present study |

| Deschampsia flexuosa | 13–30 | Magnified intersections | Alaoja (2013) |

| Deschampsia flexuosa | 23–93 | Gridline intersect | Vosatka and Dodd (1998) |

| Deschampsia flexuosa | 60.9–80.4 | Magnified intersections | Ruotsalainen et al. (2007) |

| Deschampsia flexuosa | 27–58 | Gridline intersect | Malcová et al. (1999) |

| Deschampsia flexuosa | 38 | Unclear | Read and Haselwandter (1981) |

| Eupatorium serotinum | 13.4±2.5 | Magnified intersections | Present study |

| Eupatorium serotinum | 24 | Magnified intersections | Turner et al. (2000) |

| Eupatorium serotinum | “quite abundant” | Unclear | McDougall and Glasgow (1929) |

| Eupatorium coelestinum | 0 | Unclear | McDougall and Glasgow (1929) |

| Eupatorium purpureum | “present but scarce” | Unclear | McDougall and Glasgow (1929) |

| Eupatorium urticaefolium | “present. Arbuscules observed” | Unclear | McDougall and Glasgow (1929) |

| Minuartia patula | 1.1±0.53 | Magnified intersections | Present study |

| Minuartia sp. | 0–5 | Unclear | Harley and Harley (1987) |

Our most striking result is a strong relationship between plant species identity and leaf and soil metal concentrations. We observed some evidence of total extractible contaminant concentrations decreasing with distance from the smelters, as expected (Buchauer 1973; Johnson and Richter 2010; Glassman and Casper 2012). However, plant species identity accounted for far more variation in soil metal concentrations than proximity of soil samples. This result suggests that plant species preferentially establish in soils with specific chemical profiles, or that plants exhibit species-specific effects on soil trace element chemistry, or both. These possibilities deserve further investigation to disentangle the effects of varying soil chemistry on plant establishment and competition (e.g. McCormick and Gibble 2014), and the effects of plants on the trace element chemistry of the soils in which they grow (e.g. Waring et al. 2015). Either could be a mechanism for locally positive intraspecific plant-soil feedback that could help maintain high environmental heterogeneity, with potential but complex implications for biodiversity (van der Putten et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2015). This idea is consistent with the high variability of soil physical and chemical characteristics we observed even among soils collected less than 10 m apart.

Our findings also provide empirical support for M. patula being a nonmycorrhizal, or nearly so, Zn hyperaccumulator (van der Ent et al. 2013) and tolerating some of the highest levels of soil contamination in the site. Land managers have long noticed that despite the nearby presence of taller plants that would be expected to outcompete it, M. patula forms near-monocultures on characteristic dark, powdery soils in the site. We hypothesize that these soils, which we found to have higher total extractible concentrations of all major contaminants, and higher exchangeable concentrations of Zn and Cd, are too toxic to support most of the other plant species. The small-statured M. patula, then, may remain dominant in these areas by tolerating soil metal concentrations toxic to its larger neighbors, which could also explain its failure to disperse out of the contaminated region despite living there for over 60 years (Pretz 1954). This species is still found nowhere else in Pennsylvania (Rhoads and Klein 1993; Latham et al. 2007; Rhoads and Block 2007).

At a larger taxonomic scale, many metal hyperaccumulating plant species, like M. patula, belong to predominantly nonmycorrhizal plant families and are themselves nonmycorrhizal (Leyval et al. 1997). It remains to be seen how closely (non)-association with mycorrhizal fungi is related to metal hyperaccumulation across the plant kingdom (Alford et al. 2010). It has been has suggested that there may be a trade-off between hyperaccumulation and mycorrhization because both require substantial carbon investment on the part of the plant (Audet 2013). However, numerous mycorrhizal hyperaccumulators have now been documented (e.g. Turnau and Mesjasz-Przybylowicz 2003; Vogel-Mikuš et al. 2005), leading others to wonder where there is a meaningful relationship between hyperaccumulation and mycorrhization at all (Alford et al. 2010).

Among the other species we examined, soil chemistry appears to separate plant taxa at the family level. The two Asteraceae, A. altissima and E. serotinum, seem to favor soils with higher pH and base cation concentrations and lower contaminant concentrations than the other species. In contrast, our study grasses, A. perennans and D. flexuosa, grew in soils with lowest pH and base cation concentrations, intermediate contaminant concentrations, and highest organic matter.

Conclusions

We suggest that AMF colonization has little if any effect on plant metal uptake in this metal contaminated field site. Therefore, manipulating AMF colonization is not likely to affect plant metal uptake under field conditions. Land managers seeking to modulate a plant community’s metal uptake may be better served by seeding desired plant species or using soil amendments such as compost, fertilizer, or lime, to alter soil chemistry and/or plant community composition (Dietterich and Casper 2016). We also highlight that, in light of the high local variability of soil chemistry and its close association with plant species identity, the particular plant species growing in a patch of soil could provide significant information about the chemical composition of that soil. Thus, plant community composition may be able to help us understand soil chemical characteristics as a first approximation. This insight could be useful to restoration, agriculture, mining, and other settings where it is important to understand fine-scale variation in soil chemistry.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Lehigh Gap Nature Center (LGNC), in particular D. Kunkle (LGNC), D. Husic (Moravian College), J. Lansing (Arcadis), and C. Root (EPA), as well as J. von Haden of the US National Park Service, for allowing us to collect samples on their land and sharing their wealth of knowledge about the site and its natural history and restoration. We are grateful to D. Vann for his generous help and guidance with ICP-OES measurements. We appreciate abundant help in the lab from B. Ejimole, S. McGeehan, E. Crouch, E. Bronder, E. Kim, A. Li, and especially J. Wei, who measured AMF colonization of all of the root samples. L.H.D. was supported by fellowships from the University of Pennsylvania while conducting this study, and C.G. was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number P42 ES023720 Penn Superfund Research Program Center Grant. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Data Availability

Data available from Figshare: https://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4910081

Author Contributions

LHD and BBC designed the project and conducted field work; LHD and CG collected data; LHD analyzed data and led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/eap.xxxx/suppinfo

Literature Cited

- Abdel Aziz RA, Radwan S, Dahdoh MS. Reducing the heavy metals toxicity in sludge amended soil using VA mycorrhizae. Egyptian Journal of Microbiology. 1997;32:217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Al Agely A, Sylvia DM, Ma LQ. Mycorrhizae increase arsenic uptake by the hyperaccumulator Chinese brake fern (L.) Journal of Environment Quality. 2005;34(6):2181–2186. doi: 10.2134/jeq2004.0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaoja V. Master’s Thesis. University of Jyväskylä; Finland: 2013. The role of symbiotic arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomeromycota) in roots of the host plant Deschampsia flexuosa in vegetation succession of inland sand dunes in Finnish Lapland. [Google Scholar]

- Alford ÉR, Pilon-Smits EAH, Paschke MW. Metallophytes—a view from the rhizosphere. Plant and Soil. 2010;337(1–2):33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MJ, Willis TJ. Canonical analysis of principal coordinates: a useful method of constrained ordination for ecology. Ecology. 2003;84(2):511–525. [Google Scholar]

- Audet P. Examining the ecological paradox of the “mycorrhizal-metal-hyperaccumulators”. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science. 2013;59(4):549–558. [Google Scholar]

- Audet P, Charest C. Dynamics of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in heavy metal phytoremediation: meta-analytical and conceptual perspectives. Environmental Pollution. 2007;147:609–614. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae J, Benoit DL, Watson AK. Effect of heavy metals on seed germination and seedling growth of common ragweed and roadside ground cover legumes. Environmental Pollution. 2016;213(C):112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker A. Accumulators and excluders-strategies in the response of plants to heavy metals. Journal of Plant Nutrition. 1981;3(1–4):643–654. [Google Scholar]

- Bothe H, Regvar M, Turnau K. Arbuscular mycorrhiza, heavy metal, and salt tolerance. In: Sherameti I, Varma A, editors. Soil Heavy Metals. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brady KU, Kruckeberg AR, Bradshaw HD., Jr Evolutionary ecology of plant adaptation to serpentine soils. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 2005;36(1):243–266. [Google Scholar]

- Broadley MR, White PJ, Hammond JP, Zelko I, Lux A. Zinc in plants. New Phytologist. 2007;173(4):677–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.01996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brümmer GW. Heavy metal species, mobility and availability in soils. Z Pflanzenernaehr Bodenk. 1986;149:382–398. [Google Scholar]

- Buchauer MJ. Contamination of soil and vegetation near a zinc smelter by zinc, cadmium, copper, and lead. Environmental Science and Technology. 1973;7(2):131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bunn R, Lekberg Y, Zabinski C. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi ameliorate temperature stress in thermophilic plants. Ecology. 2009;90(5):1378–1388. doi: 10.1890/07-2080.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral L, Soares CRFS, Giachini AJ, Siqueira JO. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in phytoremediation of contaminated areas by trace elements: mechanisms and major benefits of their applications. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2015;31:1655–1664. doi: 10.1007/s11274-015-1918-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo-Ricalde S, Dhillion SS, Jiménez-González C. Mycorrhizal perennials of the “matorral xerófilo” and the “selva baja caducifolia” communities in the semiarid Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley, Mexico. Mycorrhiza. 2003;13(2):77–83. doi: 10.1007/s00572-002-0203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wu C, Tang J, Hu S. Arbuscular mycorrhizae enhance metal lead uptake and growth of host plants under a sand culture experiment. Chemosphere. 2005;60(5):665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croteau MN, Luoma SN, Stewart AR. Trophic transfer of metals along freshwater food webs: evidence of cadmium biomagnification in nature. Limnology and Oceanography. 2005;50(5):1511–1519. [Google Scholar]

- del Val C, Barea JM, Azcon-Aguilar C. Assessing the tolerance to heavy metals of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi isolated from sewage sludge-contaminated soils. Applied Soil Ecology. 1999a;11:261–269. [Google Scholar]

- del Val C, Barea JM, Azcon-Aguilar C. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus populations in heavy-metal-contaminated soils. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1999b;65(2):718–723. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.718-723.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz G, Azcon-Aguilar C, Honrubia M. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizae on heavy metal (Zn and Pb) uptake and growth of Lygeum spartum and Anthyllis cytisoides. Plant and Soil. 1996;180(2):241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Dietterich LH, Casper BB. Initial soil amendments still affect plant community composition after nine years in succession on a heavy metal contaminated mountainside. Restoration Ecology. 2016 doi: 10.1111/rec.12423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding C, Festa RA, Sun TS, Wang ZY. Iron and copper as virulence modulators in human fungal pathogens. Molecular Microbiology. 2014;93(1):10–23. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Third five-year review report for Palmerton Zinc Pile Superfund Site. Palmerton, Carbon County, PA: 2007. Sep, pp. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. US EPA OSWER Office of Brownfields and Land. Brownfields and urban agriculture: Interim guidelines for safe gardening practices. 2011. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrol N, Tamayo E, Vargas P. The heavy metal paradox in arbuscular mycorrhizas: from mechanisms to biotechnological applications. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2016 doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannetti M, Mosse B. An evaluation of techniques for measuring vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal infection in roots. New Phytologist. 1980;84(3):489–500. [Google Scholar]

- Glassman SI, Casper BB. Biotic contexts alter metal sequestration and AMF effects on plant growth in soils polluted with heavy metals. Ecology. 2012;93(7):1550–1559. doi: 10.1890/10-2135.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göhre V, Paszkowski U. Contribution of the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis to heavy metal phytoremediation. Planta. 2006;223(6):1115–1122. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley JL, Harley EL. A check-list of mycorrhiza in the British flora. New Phytologist. 1987;105(2):1–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans RJ, Williams E, Vennes C. [Date of access 10 February 2017];Package “geosphere.” R package version 1.5-5. Last modified 14 June 2016. 2016 ftp://cran.r-project.org/pub/R/web/packages/geosphere/geosphere.pdf.

- Hildebrandt U, Regvar M, Bothe H. Arbuscular mycorrhiza and heavy metal tolerance. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Culture Collection of (Vesicular) Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (INVAM) [Date of access 13 September 2016];Staining of mycorrhizal roots. 2014 Last modified 10 August 2014. http://invam.wvu.edu/methods/mycorrhizae/staining-roots.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) [Date of access 10 February 2017];ISO 10390: Soil quality – Determination of pH. 2005 Last modified 2015. http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=40879.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) [Date of access 10 February 2017];ISO 23470: Soil quality – Determination of effective cation exchange capacity (CEC) and exchangeable cations using a hexamminecobalt trichloride solution. 2007 Last modified 2011. http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=36879.

- Jankong P, Visoottiviseth P, Khokiattiwong S. Enhanced phytoremediation of arsenic contaminated land. Chemosphere. 2007;68(10):1906–1912. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q-Y, Zhuo F, Long S-H, Zhao H-D, Yang D-J, Ye Z-H, Li S-S, Jing Y-X. Can arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi reduce Cd uptake and alleviate Cd toxicity of Lonicera japonica grown in Cd-added soils? Scientific Reports. 2016;6:21805. doi: 10.1038/srep21805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AH, Richter SL. Organic-horizon lead, copper, and zinc contents of Mid-Atlantic forest soils, 1978–2004. Soil Science Society of America Journal. 2010;74(3):1001–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan MJ. Effects of zinc smelter emissions and fire on a chestnut-oak woodland. Ecology. 1975;56(1):78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan MJ, Lechevalier MP. Effects of zinc-smelter emissions on forest soil microflora. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 1975;21:1855–1865. doi: 10.1139/m75-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AG. Relationships between chromium biomagnification ratio, accumulation factor, and mycorrhizae in plants growing on tannery effluent-polluted soil. Environment International. 2001;26(5–6):417–423. doi: 10.1016/s0160-4120(01)00022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimek B, Niklińska M. Zinc and copper toxicity to soil bacteria and fungi from zinc polluted and unpolluted soils: a comparative study with different types of Biolog plates. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2007;78(2):112–117. doi: 10.1007/s00128-007-9045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagrange A, L’Huillier L, Amir H. Mycorrhizal status of Cyperaceae from New Caledonian ultramafic soils: effects of phosphorus availability on arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization of Costularia comosa under field conditions. Mycorrhiza. 2013;23(8):655–661. doi: 10.1007/s00572-013-0503-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham RE, Steckel DB, Harper HM, Steckel C, Boatright M. Lehigh Gap Wildlife Refuge Ecological Assessment. Natural Lands Trust, Media PA, Continental Conservation; Rose Valley PA, Botanical Inventory, Allentown PA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A, Rillig MC. Arbuscular mycorrhizal contribution to copper, manganese and iron nutrient concentrations in crops - a meta-analysis. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2015;81:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A, Veresoglou SD, Leifheit EF, Rillig MC. Arbuscular mycorrhizal influence on zinc nutrition in crop plants - A meta-analysis. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2014;69:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Leyval C, Turnau K, Hasfelwandter K. Effect of heavy metal pollution on mycorrhizal colonization and function: physiological, ecological and applied aspects. Mycorrhiza. 1997;7(3):139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Liu RJ, Christie P, Li XL. Influence of three arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and phosphorus on growth and nutrient status of taro. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis. 2005;36(17–18):2383–2396. [Google Scholar]

- Lin YF, Aarts MGM. The molecular mechanism of zinc and cadmium stress response in plants. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2012;69(19):3187–3206. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1089-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Christie P, Zhang J, Li X. Growth and arsenic uptake by Chinese brake fern inoculated with an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2009;66(3):435–441. [Google Scholar]

- Malcová R, Vosátka M, Albrechtová J. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and simulated acid rain on the growth and coexistence of the grasses Calamagrostis villosa and Deschampsia flexuosa. Plant and Soil. 1999;207(1):45–57. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick PV, Gibble RE. Effects of soil chemistry on plant germination and growth in a northern Everglades peatland. Wetlands. 2014;34(5):979–988. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall WB, Glasgow OE. Mycorhizas of the Compositae. American Journal of Botany. 1929;16(4):225–228. [Google Scholar]

- McGonigle TP, Miller MH, Evans DG, Fairchild GL, Swan JA. A new method which gives an objective measure of colonization of roots by vesicular—arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytologist. 1990;115(3):495–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1990.tb00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miransari M. Contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis to plant growth under different types of soil stress. Plant Biology. 2010;12(4):563–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2009.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miransari M. Hyperaccumulators, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and stress of heavy metals. Biotechnology Advances. 2011;29(6):645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Stevens MHH, Wagner H. [Date of access 10 February 2017];vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.0-7. 2013 Last modified 19 March 2013. http://cran.r-project.org, http://vegan.r-forge.r-project.org/

- Orłowska E, Przybylowicz W, Orlowski D, Mongwaketsi NP, Turnau K, Mesjasz-Przybylowicz J. Mycorrhizal colonization affects the elemental distribution in roots of Ni-hyperaccumulator Berkheya coddii Roessler. Environmental Pollution. 2013;175(C):100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowska TE, Błaszkowski J, Rühling Å. The mycorrhizal status of plants colonizing a calamine spoil mound in southern Poland. Mycorrhiza. 1996;6(6):499–505. [Google Scholar]

- Pilon-Smits E. Phytoremediation. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2005;56(1):15–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretz HW. Arenaria patula in Pennsylvania. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 1954;81(5):455–456. [Google Scholar]

- Read DJ, Haselwandter K. Observations on the mycorrhizal status of some alpine plant communities. New Phytologist. 1981;88(2):341–352. [Google Scholar]

- Remon E, Bouchardon JL, Le Guédard M, Bessoule JJ, Conord C, Faure O. Are plants useful as accumulation indicators of metal bioavailability? Environmental Pollution. 2013;175:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads AF, Block TA. The Plants of Pennsylvania: An Illustrated Manual. 2. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads AF, Klein WMJ. The Vascular Flora of Pennsylvania: Annotated Checklist and Atlas. Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Romic M, Romic D. Heavy metals distribution in agricultural topsoils in urban area. Environmental Geology. 2003;43:795–805. [Google Scholar]

- Ruotsalainen AL, Markkola A, Kozlov MV. Root fungal colonisation in Deschampsia flexuosa: Effects of pollution and neighbouring trees. Environmental Pollution. 2007;147(3):723–728. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schützendübel A, Polle A. Plant responses to abiotic stresses: heavy metal-induced oxidative stress and protection by mycorrhization. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2002;53(372):1351–1365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DB, Cannon WF, Soodruff LG, Solano F, Kilburn JE, Fey DL. Geochemical and mineralogical data for soils of the conterminous United States: US Geological Survey Data Series 801. [Date of access 10 February 2017];US Geological Survey Data Series 801. 2013 Last modified 2013. http://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/801/

- Smith SE, Read D. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. 3. New York, NY: Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SE, Smith FA, Jakobsen I. Functional diversity in arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbioses: the contribution of the mycorrhizal P uptake pathway is not correlated with mycorrhizal responses in growth or total P uptake. New Phytologist. 2004;162(2):511–524. [Google Scholar]

- Strojan CL. The impact of zinc smelter emissions on forest litter arthropods. Oikos. 1978;31:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tan SY, Jiang QY, Zhuo F, Liu H, Want YT, Li SS, Ye ZH, Jing YX. Effect of inoculation with Glomus versiforme on cadmium accumulation, antioxidant activities and phytochelatins of Solanum photeinocarpum. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0132347–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus J, Tsuyuzaki S. Arbuscular mycorrhizal distribution in relation to microsites on recent volcanic substrates of Mt. Koma, Hokkaido, Japan. Mycorrhiza. 2002;12(6):271–275. doi: 10.1007/s00572-002-0182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonin C, Vandenkoornhuyse P, Joner EJ, Straczek J, Leyval C. Assessment of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi diversity in the rhizosphere of Viola calaminaria and effect of these fungi on heavy metal uptake by clover. Mycorrhiza. 2001;10(4):161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Turnau K, Mesjasz-Przybylowicz J. Arbuscular mycorrhiza of Berkheya coddii and other Ni-hyperaccumulating members of Asteraceae from ultramafic soils in South Africa. Mycorrhiza. 2003;13(4):185–190. doi: 10.1007/s00572-002-0213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SD, Amon JP, Schneble RM, Friese CF. Mycorrhizal fungi associated with plants in ground-water fed wetlands. Wetlands. 2000;20(1):200–204. [Google Scholar]

- van der Ent A, Baker AJM, Reeves RD, Pollard AJ, Schat H. Hyperaccumulators of metal and metalloid trace elements: facts and fiction. Plant and Soil. 2013;362(1–2):319–334. [Google Scholar]

- van der Putten WH, Bardgett RD, Bever JD, Bezemer TM, Casper BB, Fukami T, Kardol P, Klironomos JN, Kulmatiski A, Schweitzer JA, Suding KN, Van de Voorde TFJ, Wardle DA. Plant-soil feedbacks: the past, the present and future challenges. Journal of Ecology. 2013;101:265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel-Mikuš K, Pongrac P, Kump P, Necemer M, Regvar M. Colonisation of a Zn, Cd and Pb hyperaccumulator Thlaspi praecox Wulfen with indigenous arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal mixture induces changes in heavy metal and nutrient uptake. Environmental Pollution. 2006;139(2):362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel-Mikuš K, Drobne D, Regvar M. Zn, Cd and Pb accumulation and arbuscular mycorrhizal colonisation of pennycress Thlaspi praecox Wulf. (Brassicaceae) from the vicinity of a lead mine and smelter in Slovenia. Environmental Pollution. 2005;133(2):233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosátka M, Dodd JC. The role of different arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the growth of Calamagrostis villosa and Deschampsia flexuosa, in experiments with simulated acid rain. Plant and Soil. 1998;200(2):251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Shi J, Wang H, Lin Q, Chen X, Chen Y. The influence of soil heavy metals pollution on soil microbial biomass, enzyme activity, and community composition near a copper smelter. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2007;67(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring BG, Álvarez-Cansino L, Barry KE, Becklund KK, Dale S, Gei MG, Keller AB, Lopez OR, Markesteijn L, Mangan S, Riggs CE, Rodríguiez-Ronderos ME, Segnitz RM, Schnitzer SA, Powers JS. Pervasive and strong effects of plants on soil chemistry: a meta-analysis of individual plant “Zinke” effects. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2015;282(1812):20151001–8. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiersbye IM, Straker CJ, Przybylowicz WJ. Micro-PIXE mapping of elemental distribution in arbuscular mycorrhizal roots of the grass, Cynodon dactylon, from gold and uranium mine tailings. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B. 1999;158(1–4):335–343. [Google Scholar]

- Weissenhorn I, Leyval C, Belgy G, Berthelin J. Arbuscular mycorrhizal contribution to heavy metal uptake by maize (Zea mays L.) in pot culture with contaminated soil. Mycorrhiza. 1995;5(4):245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GW, Hartnett DC. Interspecific variation in plant responses to mycorrhizal colonization in tallgrass prairie. American Journal of Botany. 1998;85(12):1732–1738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston JR, Bowman JJ, Yothers WW. United States Department of Agriculture Department Bulletin No. 1178. 1923. Bordeaux-oil emulsion; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Yang X, Zhang W, Wei Y, Ge G, Lu W, Sun J, Liu N, Kan H, Shen Y, Zhang Y. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi affect plant community structure under various nutrient conditions and stabilize the community productivity. Oikos. 2015;125(4):576–585. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.