Introduction

Internet gaming disorder (IGD), defined as “Persistent and recurrent use of the Internet to engage in games, often with other players, leading to clinically significant impairment or distress,” is a condition for further study in the most recent version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the DSM-5 (1), and research publications in gaming and internet addiction have increased rapidly in the last decade (2,3). Its precise definition continues to generate considerable controversy (4–7) and a multitude of measuring tools (8–13). Significant overlap in the neurobiology underlying both behavioral addictions and substance use disorders have been found in animal models and human brain imaging studies (14–16), starting with Gambling Disorder, which entered the DSM-III in 1980, and, as starting points for studying this phenomenon, the criteria for diagnosing IGD have been derived from different facets of Gambling Disorder, Substance Use Disorder, Impulse Control Disorders, and the developing field of Internet Addiction (17–20). Given rapid expansion of internet use and gaming technology over the past 20 years, a review of available prevalence measurements could potentially allow for detection of an epidemiological trajectory for this disorder.

Prior to IGD being listed as a Condition for Further Study in the DSM-5, the terminology for the phenomenon of excessive online gaming was not standardized, with nomenclature varying from problematic online gaming, pathological gaming, gaming addiction, excessive gaming, gaming use disorder, videogame addiction, videogame dependency to conflations with internet addiction, internet use disorder, pathological internet use, problematic internet use, technology use disorder, pathological technology use, to compulsive internet use (10,21–30). In this paper, we take an agnostic approach to the specific criteria being used to measure this phenomenon, and are interested in whether the reported prevalence of this disorder has changed with time, given the rapidly expanding access to internet games, and the exponential growth of publications in the area of psychopathology related to technology (31–34). To this end, we have undertaken a targeted review of the literature regarding the prevalence of Internet Gaming Disorder in any population, organized in a linear manner spanning the emergence of the earliest publications regarding gaming addiction in the 1990s, through the end of 2016.

Methods

The following search terms were entered in PubMed on November 4, 2016: “internet addiction” “game addiction” “gaming addiction” “pathological gaming” “internet gaming disorder” AND “prevalence.” There was no restriction on time period of the study. The inclusion criteria were: i) original study using empirically collected data; ii) paper written in English; iii) inclusion of a measure of gaming addiction or internet addiction with a subset of gaming addiction; iv) full-text availability; v) at least 200 subjects were studied; vi) a natural (e.g. non-clinical, recruited from a school or the general public) population was studied; vii) prevalence of problem gaming was reported as a percentage.

A total of 1,258 citations were identified from the search criteria, which was reduced to 379 after duplicates were removed. Abstracts were manually searched for internet gaming relevance and language accessibility. 285 articles were subsequently excluded due to non-relevance or publication in another language; many of these dealt with gambling, substance use disorder, or internet addiction more broadly without including gaming. This yielded 94 full-text articles in English which were topically relevant, though an additional 27 articles were excluded due to their being reviews, commentaries, or letters, and two were excluded due to reporting on fewer than 200 subjects. A total of 67 studies met inclusion criteria for review. Of these 67 studies, 27 did not report a direct percentage of prevalence in the population studied, and 13 sampled from specialized populations which were likely to bias the result towards higher rates of IGD (six were from online gaming forums, three were from nonspecific self-selected online populations, three were from clinics treating IGD or IA, and one was from a clinic specializing in suicide prevention). This resulted in a total of 27 studies which reported prevalence of disordered gaming as a percentage of a naturally-occurring convenience sample and were thus included in the quantitative portion of this review.

Results

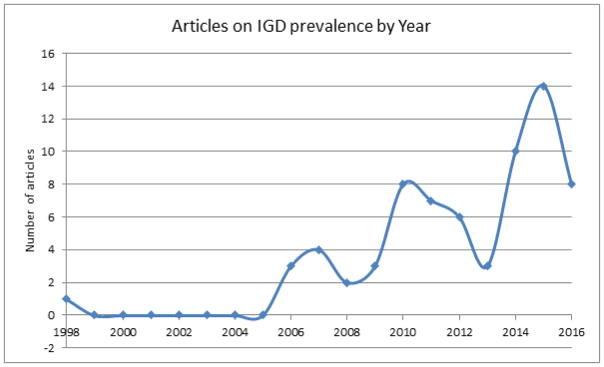

The studies of IGD ranged in publication year from 1998 – 2016, with a single paper from 1998, a large gap from 1998–2006, and exponential growth from 2006 onward (Figure 1). Of note, more papers have been published on internet addiction than internet gaming disorder (219 vs 43) (31), though the former has not been officially recognized by the DSM as a condition for further study. In the interest of maximizing the papers examined in this review, the abstracts for papers concerning internet addiction were hand-searched for relevance to gaming phenomena and included if so. The search term “internet gaming disorder” yielded articles more specific to gaming phenomena than the other search terms.

Fig. 1.

Number of Articles Published on IGD Prevalence Over Time (N=67; 27 studies in Natural Populations). The number of articles meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria for this review are plotted by year of publication.

The studies in the quantitative review were conducted with samples in a wide range of countries, mostly in Europe (N=14 studies), and East Asia (N=8), with two studies in North America, one in Australia, one in Iran, and one which encompassed both North America and three countries in Europe. Since consensus has not been reached on the definition of IGD, all studies meeting inclusion criteria which reported prevalence rate were analyzed, again in the interest of examining all available studies in the literature on this topic. Overall, 23 different scales were used, with some minor variations (Table 2). Participants for all of the included studies were recruited in-person, except for one study which recruited by mail, and two which used online surveys. These two online studies were included because they were conducted using reputable marketing research firms who outreach to the general public, in countries with 70–90% internet access rates at the time the studies were conducted. Therefore in these studies, the online survey method was deemed fairly unlikely to have been biased towards individuals who already use games excessively or have underlying mental health disorders (35,36). Additionally, while one study drew from army bases, since military conscription is mandatory and universal among males in that country, it was believed that this sample would not be enriched for IGD beyond males from that age group (37).

Table 2.

Overview of scales used to measure IGD

| Name of scale | Number of Items | Item type | Threshold to meet IGD “diagnosis” | Reference # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-item scale based on Minnesota Impulse Disorder Inventory | 3 | dichotomous | ≥3/3 | 23 |

| 4-item scale based on self-perceived negative consequences | 4 | dichotomous | ≥3 | 24 |

|

AICA-S Scale for the Assessment of Internet and Computer game Addiction |

14 | 5-point and dichotomous | >13 points | 5 |

|

AICA-S – Gaming Module Based on DSM-5 |

13 | 5-point and dichotomous | >13.5 points | 11 |

| Brief indicators checklist (DSM-5) | 9 | dichotomous | ≥5/9 +report of suffering significant distress due to gaming | 1 |

|

CIAS Chen Internet Addiction Scale |

26 | 4-point Likert scale | ≥ 64/104 points | 26 |

|

CIUS Compulsive Internet Use Scale |

14 | 5-point | ≥2.8/5 approximate average score based on latent class analysis | 21 |

|

CSAS/VGDS “Computerspielabhängigkeitsskala” Video Game Dependency Scale Based on DSM-5 |

18 | 4-point Likert | ≥5/9 criteria scoring ≥ 4/4 on ≥ ½ items | 9 |

|

DRM 52 Adapted from Young IAT |

52 | 5-point | >163/260 Approximate score based on latent class analysis | 17 |

| DSM-4 criteria for “dependence” | 7 | dichotomous | ≥3/7 | 12 |

| DSM-4 criteria for pathological gambling - 11 item scale | 11 | 3-point | ≥6/11 | 25 |

| DSM-4 criteria for pathological gambling (Gentile) | 10 | 3-point | ≥5/10 | 20 |

| DSM-4 criteria for pathological gambling (Lemmens) | 7 | 5-point | ≥3/7 | 22 |

| DSM-5 - 9 criteria | 9 | 5-point Likert | ≥5/9 items scoring ≥3/5 | 2 |

|

GAS Gaming Addiction Scale – short form |

7 | 5-point | ≥4/7 items scoring ≥3/5 | 6 (French, German), 7 (Finnish) |

|

GAS - Chinese Gaming Addiction Scale – short form |

7 | 5-point | ≥3/7 items scoring ≥4/5 | 13 (Chinese) |

|

IGDS9-SF Internet Gaming Disorder Scale – 9 Short-Form |

9 | 5-point | ≥5/9 items scoring ≥5/5 | 4 |

| Korean internet addiction test | 40 | 4-point | ≥top 5% of sample based on t-test | 27 |

|

PTU Pathological Technology Use checklist |

10 | dichotomous | ≥ 5/10 “yes” | 15 |

|

POGQ-SF Problematic Online Gaming Questionnaire-Short Form |

12 | 5-point | ≥32/60 | 16 |

| Yes/no self-report | 1 | dichotomous | ≥1 | 10 |

|

YDQ short 8-item Young’s Diagnostic Questionnaire |

8 | dichotomous | ≥5/8 | 3,8, 14, 18 |

|

Young’s IAT Young’s internet addiction test |

20 | 5-point | ≥70/100 | 19 |

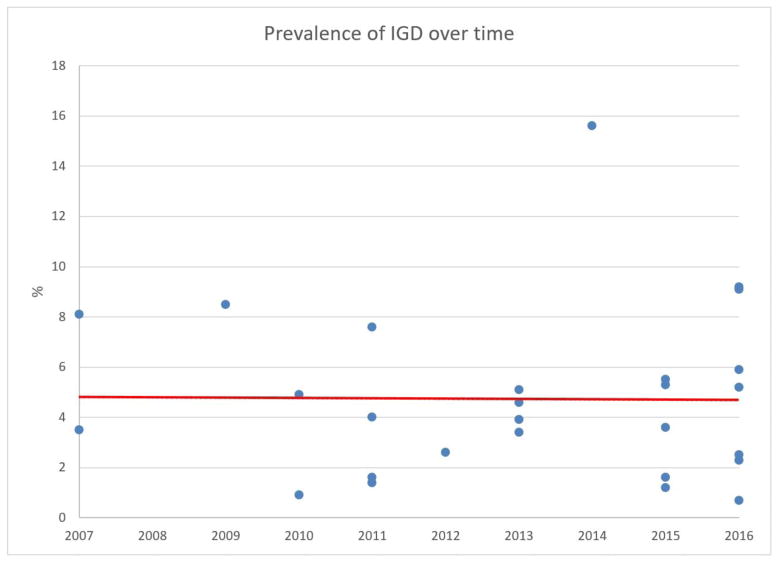

Overall prevalence of IGD ranged from 0.7–15.6% in studies of naturalistic populations (not enriched for clinical or online communities) (Figure 2). For studies with longitudinal data, the most recent prevalence percentage was included, since it would be closest to the publication year (25,38,39), while nine studies required minor calculations to arrive at an overall prevalence figure. The average percentage was 4.7% across all years, and a linear trendline of the data yielded slope m = −0.0137. No region or country appeared to have a remarkably different prevalence of IGD, though the highest rate was found in one study of high school students in Hong Kong (40) which used a less stringent cut-off score for determining IGD than other studies using that scale (. The majority of the studies were school-based. The age range studied was primarily from mid-teens to twenties given the school population surveyed, though studies of clinical, geographic, or online populations tended to be older, with a mean age in the late 30s–40s. The samples had mostly even numbers of male and female participants with the exception of the surveys in Switzerland, Singapore, and Korea who had significantly more men than women participating.

Fig. 2.

IGD Prevalence Over Time (N=27 studies in Natural Populations). Prevalence data were extracted from publications with quantitative data on prevalence rates, in natural populations (e.g. study of all students in a particular grade in school, or representative sample of the general population), graphed by publication year. The average percentage was 4.7% across all years, and a linear trendline of the data yielded slope m = −0.0137.

Discussion

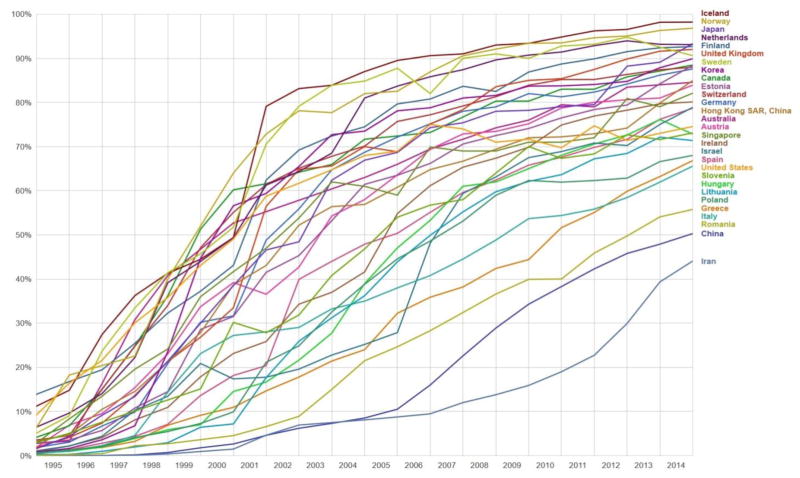

The most striking finding of this review of IGD prevalence over time was how little the measured prevalence has changed, despite 15 years of technological advancement, increased internet penetration around the world, and ever more sophisticated games available (Figure 3). It might be presumed that increases in Internet access would allow for progressively greater exposure to internet gaming (42,43); yet disordered gaming does not appear to have increased as exponentially as has exposure. Conclusions were limited by the variable measurements and quality of the studies which met inclusion criteria. It is questionable whether prevalence for a disorder which is still seeking a unified definition (4,6,41) is measurable at this point; and the few studies from each year which were of sufficient size and precision to meet inclusion criteria drew from a wide variety of populations and measurement tools. The majority of the studies were also drawn from school populations as this phenomenon is being studied more closely in adolescents; however, this limits generalizability to the wider population which would be needed in a study specifically examining prevalence.

Fig 3.

Internet users as a percentage of the population. Percentage with access to the internet per 100 inhabitants of the 29 countries surveyed, from 1995–2015. Data from the World Bank.

Multiple studies have found availability of gambling outlets to lead to increased gambling addiction (44–46). Since a hallmark of addiction is continued use despite negative consequences, the lack of subsequently impaired function is one way to distinguish between healthy and unhealthy use. Longitudinal studies of behavioral addictions including gaming and problematic internet use have found low persistence of the disorder after one year (47,48), while others have found these disorders to persist (38,49). Other studies find that prevalence varies with age (36,50,51), quality of educational setting (10) and region (43,52,53).

There is disagreement on whether one can be addicted to the internet itself, or addicted to separate behaviors (e.g., gaming, shopping, sex, social media) which are facilitated by the online interface (5,32,54–56). If one thinks of the underlying psychological or social needs driving those distinct behaviors, however, these separate behaviors are all related. Many of these activities are normal behaviors and can even enhance relationships. As research in the area of “internet addiction” proceeds, it may be prudent to collect subjects’ self-report of which online activities are causing the most negative consequences due to excess use (57,58).

There are some strengths of the literature and progress in the field to highlight. Large-scale cohort projects are underway, which can assess change in the phenomenon in the given population over time (37,49). Also, the term “internet gaming disorder” proposed in DSM-5 provides a more specific search term for gaming disorder, and accounts for lengthy use (e.g. symptoms lasting at least 12 months) which is likely to indicate enduring and more clinically significant pathology.

There are several limitations of the current study, namely: 1) A variety of scales were used to assess IGD, leading to imprecision within this study (Table 2). 2) Publication year was used to approximate when the study was conducted, since many of the studies did not report a specific time frame for data collection. Since studies which did report time frame for data collection used data from within a few years of publication, the publication year seemed to be the best approximation. 3) Calculable prevalence data from naturalistic populations were only available from 27 out of 67 articles mentioning prevalence.. 4) The measures of IGD prevalence had a 15%, range calling into question whether the stated prevalence estimates may actually reflect the given phenomenon. 5) Additional articles which were not found by the search terms are likely to be present in the literature, particularly because the results were limited to articles published in English found in PubMed. It is noteworthy that despite spanning 29 countries across North America, Europe, East and Central Asia, the Middle East and Australia, our review found no studies in Latin America or the Caribbean, South Asia, or Africa at this time.

Based on this review, we have five recommendations to improve research on the prevalence of IGD: 1) Consistent methodology in measuring IGD, including distinguishing between IA and IGD, to build a theoretically sound model (5,6,54) and strive for specificity (59). 2) Study populations with comparable demographics and recruitment (mixed/single gender, urban/rural, similar ages, cultures) and studying the disorder across age groups/cultures (60,61). 3) Clear data regarding comorbid diagnoses and personality ratings to ascertain to what extent IGD occurs independently of ADHD, depression, anxiety, etc. (50,62,63). 4) Longitudinal studies, which can help clarify which criteria are enduring and thus more clinically applicable (11,21,38). 5) Cultural and social environment factors which may cause the disorder to be expressed differently in different cultural groups, regions, ages, genders. This complexity will confound prevalence estimates, but accounting for these factors during the measurement process will yield greater insight into the pathophysiology of the disorder later on. (32,52,64,65).

Conclusion

Internet gaming disorder, interpreted broadly as excessive use of online games despite negative consequences, affects a small subset of the population exposed to online games, and does not appear to have increased in prevalence to the extent that internet usage has increased. Findings call for deeper research with longitudinal designs and directly comparable definitions of IGD, to understand how this disorder may function as an independent clinical problem to inform diagnostic and treatment efforts.

Table 1.

Articles on Internet Gaming Disorder Prevalence

| Year | Prevalence | S ample size | Country | % Male in sample | Mean Age or Range (S D) | Measure | Reference and sample details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 0.7%* | N=18932 | USA, UK, Canada, Germany | 48.3% | 18–65 (n.r.) | Brief indicators checklist | 1: Przybylski AK, et al. 2016 Online Online recruitment using general marketing services Google Surveys and YouGov using joint distributions of age, gender, geographic location |

| 2016 | 5.9% | N=2024 | Korea | 50.6% | 14.5 (0.5) | DSM-5–9 criteria | 2: Yu H, Cho J. 2016 School Grade 8–9 Nationwide survey in 3 or more randomly-selected schools from all 15 regions (7 major metropolitan cities, 8 regional provinces) |

| 2016 | 9.2%* | N=1806 | Lithuania | 50.2% | 15.8 (0.9) | YDQ | 3: Ustinavi ien R, et al. 2016 School Grade 9–11 Nationally representative sample, randomly selected 20 of 56 schools in Kaunas County |

| 2016 | 2.5% | N=1071 | Slovenia | 50.2% | 13.4 (0.6) | IGDS9-SF | 4: Pontes HM, et al. 2016 School Grade 8 Random probability sample stratified by population density and the 12 statistical regions of Slovenia |

| 2016 | 5.2% | N=3967 | Germany | 54.5% | 15.5 (1.6) | AICA-S | 5: Dreier M, et al. 2016 School Grade 9–12 41 randomly selected secondary schools from state of Rhineland-Palatinate |

| 2016 | 2.3% | N=5983 | Switzerland | 100% | 20.3 (1.3) | GAS | 6: Khazaal Y, et al. 2016 Military C-SURF (Cohort Study on Substance Use Risk Factors), from 3 of 6 national army recruitment centers |

| 2016 | 9.1% | N=293 | Finland | 51% | 18.7 (3.4) | GAS | 7: Männikkö N, et al. 2015 Geographic Randomly selected from Finland National Registry, stratified and balanced for age (13–24) and gender |

| 2015 | 3.6% | N=8807 | Europe (Estonia, Germany, Italy, Romania, Spain) | 44.5% | 15 (1.3) | YDQ | 8: Strittmatter E, et al. 2015 School WE-STAY (Working in Europe to Stop Truancy Among Youth) project: 132 Randomly selected secondary schools from several countries |

| 2015 | 1.2% | N=11003 | Germany | 51.1% | 14.9 (0.7) | DSM-5 IGD criteria CSAS 18-item |

9: Rehbein F, et al. 2015 School Grade 9 Random selection from each tier of lower, middle, and higher levels of academic achievement in state of Lower Saxony |

| 2015 | 5.5% | N=5003 | Japan | n.r. | 20–89 (n.r.) | Yes/no self-report | 10: Shiue I. 2015 Geographic JGSS (Japanese General Social Survey): National survey, two-stage stratified random sampling by household interview |

| 2015 | 1.6% | N=12938 | Europe (Germany, Greece, Iceland, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain) | 47.1% | 14–17 (n.r.) | AICA-S | 11: Müller KW, et al. 2015 School Grade 10 Random probability sample with stratification based on region and population density |

| 2014 | 5.3% | N=1020 | Iran | 50% | n.r. (n.r.) | DSM4, in-person interview | 12: Ahmadi J, et al. 2014 School Grade 9–11 Random selection by area and cluster sampling from high schools in Shiraz |

| 2014 | 15.6% | N=503 | Hong Kong | 49.5% | 14.6 (1.4) | GAS Chinese | 13: Wang CW, et al. 2014 School Grade 8–11 Two randomly selected schools from Central District and Kowloon East districts |

| 2014 | 3.4%* | N=24103 | China | 53.3 | 12.8 (1.8) | YDQ | 14: Li Y, et al. 2014 School Grades 4–9 NCSC (National Children’s Study of China): 100 counties stratified sampling from all 31 provinces |

| 2013 | 5.1%* | N=1287 | Australia | 49.6% | 14.8 (1.5) | PTU scale | 15. King DL, et al. 2013 School Random selection of 50 secondary schools in outer metropolitan region of Adelaide |

| 2013 | 4.6% | N=2804 | Hungary | 51% | 16.4 (0.9) | POGQ-SF | 16: Pápay O, et al. 2013 School Grade 8–10 ESPAD (European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs): internationally homogenous stratified sampling based on region, grade, class type |

| 2013 | 3.9%* | N=5122 | China | 49.6% | 15.9 (n.r.) | DRM 52 scale | 17: Xu J, et al. 2012 School Grade 7–11 Stratified cluster random sampling of 16 schools from 19 administrative districts of Shanghai |

| 2012 | 2.6%* | N=11956 | Europe (Austria, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden) | 43.7% | 14.9 (n.r.) | YDQ | 18: Durkee T, et al. 2012 School SEYLE (Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe): 178 randomly selected schools within 11 study sites |

| 2011 | 1.4% | N=866 | Greece | 46.7% | 14.7 (n.r.) | IAT | 19: Kormas G, et al. 2011 School Grade 9–10 Random cluster sample of 20 schools, stratified by locality and population density in Athens |

| 2011 | 7.6%L | N=3034 | Singapore | 72.7% male (T1) | n.r. (n.r.) | 10-item scale | 20: Gentile DA, et al. 2011 School Grade 3–8 12 schools widely distributed across East, West, South, North regions in Singapore |

| 2011 | 1.6% L | N=1572 (T1), 1476 (T2) | Netherlands | 49% (T1), 52% (T2) | 14.4 (1.2) (T1), 14.3 (1.0) (T2) | CIUS | 21: Van Rooij AJ, et al. 2011 School Dutch “Monitor Study Internet and Youth”: stratified sample of 12 schools based on region, urbanization, and education level |

| 2011 | 4% L | N=1024 (T1), 941 (T2) | Netherlands | 51% | 13.9 (1.4) T1, 14.3 (1.4) T2 | 7-item scale | 22: Lemmens JS, et al. 2011 School 4 schools in urban and suburban districts in the Netherlands |

| 2010 | 4.9% | N=4028 | USA | 45.8% | 14–18 (n.r.) | 3-item scale | 23: Desai RA, et al. 2010 School 10 high schools self-selected and targeted to all representative geographic regions of the state of Connecticut |

| 2010 | 0.9%* | N=3405 | Norway | 51.1% | n.r. (n.r.) | 4-item scale | 24: Wenzel HG, et al. 2009 Geographic National population database random sample stratified by gender, age, and country |

| 2009 | 8.5%* | N=1178 | USA | 49.9% | n.r. (n.r.) | 11-item scale | 25: Gentile D. 2009 Online Stratified random sample recruited through password-protected mail invitations from Harris Polls; found to be regionally and ethnically nationally representative |

| 2007 | 8.1%L | N=517 | Taiwan | 51.6% | 13.6 (0.9) | CIAS | 26: Ko CH, et al. 2007 School Grade 7–8 Randomly selected by cluster sampling from 3 schools in southern Taiwan |

| 2007 | 3.5%* | N=627 | Korea | 77.8% | 15.9 (0.9) | Korean IAT 40-items | 27: Lee M S, et al. 2007 School One high school and two middle schools in southeast Seoul |

Small calculations (averaging, simple arithmetic) were used to arrive at a percentage value.

For longitudinal studies, the most recent percentage was used to reflect the value closest to publication year.

n.r. = not reported

Highlights.

Prevalence data related to internet gaming disorder were reviewed

The availability of internet and gaming technologies increased from 1998–2016

From available data, average prevalence of disordered gaming did not increase

This result has implications for the characterization of this emerging disorder

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Elias Aboujaoude for his comments during the revision process.

Footnotes

Disclosures

- The research meets all applicable standards with regard to the ethics of experimentation and research integrity, and the following is being certified/declared true.

- As a scientific professional and along with co-authors of the mental health field, the paper has been submitted with full responsibility, following due ethical procedure, and there is no duplicate publication, fraud, plagiarism, or concerns about animal or human experimentation.

- None of the authors of this paper has a financial or personal relationship with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper.

Declaration of interest:

The preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by a career development award from NIDA (K23DA032578; PI, D. Ramo). None of the funding agencies had any role in the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication. None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Conditions for Further Study. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington VA: 2013. pp. 795–798. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carbonell X, Guardiola E, Beranuy M, Bellés A. A bibliometric analysis of the scientific literature on Internet, video games, and cell phone addiction. J Med Libr Assoc. 2009 Apr;97(2):102–7. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.97.2.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Internet Gaming Addiction: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2011 Mar 16;10(2):278–96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffiths MD, van Rooij AJ, Kardefelt-Winther D, Starcevic V, Király O, Pallesen S, et al. Working towards an international consensus on criteria for assessing internet gaming disorder: a critical commentary on Petry et al. (2014) Addiction. 2016 Jan;111(1):167–75. doi: 10.1111/add.13057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kardefelt-Winther D. Conceptualizing Internet use disorders: Addiction or coping process? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci [Internet] 2016 Jun 9; doi: 10.1111/pcn.12413. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12413. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Pontes HM. Chaos and confusion in DSM-5 diagnosis of Internet Gaming Disorder: Issues, concerns, and recommendations for clarity in the field. J Behav Addict. 2016 Sep;7:1–7. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petry NM, Rehbein F, Gentile DA, Lemmens JS, Rumpf H-J, Mößle T, et al. Griffiths et al.’s comments on the international consensus statement of internet gaming disorder: furthering consensus or hindering progress? Addiction. 2016 Jan;111(1):175–8. doi: 10.1111/add.13189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearcy BTD, Roberts LD, McEvoy PM. Psychometric Testing of the Personal Internet Gaming Disorder Evaluation-9: A New Measure Designed to Assess Internet Gaming Disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2016 May;19(5):335–41. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders JL, Williams RJ. Reliability and Validity of the Behavioral Addiction Measure for Video Gaming. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2016 Jan;19(1):43–8. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rehbein F, Kliem S, Baier D, Mößle T, Petry NM. Prevalence of Internet gaming disorder in German adolescents: diagnostic contribution of the nine DSM-5 criteria in a state-wide representative sample. Addiction. 2015 May;110(5):842–51. doi: 10.1111/add.12849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffiths MD, King DL, Demetrovics Z. DSM-5 internet gaming disorder needs a unified approach to assessment. Neuropsychiatry. 2014;4(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai C-M, Mak K-K, Watanabe H, Ang RP, Pang JS, Ho RCM. Psychometric properties of the internet addiction test in Chinese adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(7):794–807. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King DL, Haagsma MC, Delfabbro PH, Gradisar M, Griffiths MD. Toward a consensus definition of pathological video-gaming: a systematic review of psychometric assessment tools. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013 Apr;33(3):331–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park B, Han DH, Roh S. Neurobiological findings related to Internet use disorders. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci [Internet] 2016 Jul 23; doi: 10.1111/pcn.12422. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12422. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Han DH, Kim SM, Bae S, Renshaw PF, Anderson JS. Brain connectivity and psychiatric comorbidity in adolescents with Internet gaming disorder. Addict Biol [Internet] 2015 Dec 22; doi: 10.1111/adb.12347. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/adb.12347. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Parvaz MA, Alia-Klein N, Woicik PA, Volkow ND, Goldstein RZ. Neuroimaging for drug addiction and related behaviors. Rev Neurosci. 2011 Nov 25;22(6):609–24. doi: 10.1515/RNS.2011.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Internet and gaming addiction: a systematic literature review of neuroimaging studies. Brain Sci. 2012 Sep 5;2(3):347–74. doi: 10.3390/brainsci2030347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):363–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1511480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desai RA, Krishnan-Sarin S, Cavallo D, Potenza MN. Video-gaming among high school students: health correlates, gender differences, and problematic gaming. Pediatrics. 2010 Dec;126(6):e1414–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strittmatter E, Kaess M, Parzer P, Fischer G, Carli V, Hoven CW, et al. Pathological Internet use among adolescents: Comparing gamers and non-gamers. Psychiatry Res. 2015 Jul 30;228(1):128–35. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choo H, Gentile DA, Sim T, Li D, Khoo A, Liau AK. Pathological video-gaming among Singaporean youth. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010 Nov;39(11):822–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grüsser SM, Thalemann R, Griffiths MD. Excessive computer game playing: evidence for addiction and aggression? Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007 Apr;10(2):290–2. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffiths MD, Meredith A. Videogame Addiction and its Treatment. J Contemp Psychother. 2009 May 12;39(4):247–53. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Rooij AJ, Schoenmakers TM, van de Eijnden RJJM, van de Mheen D. Compulsive Internet Use: The Role of Online Gaming and Other Internet Applications. J Adolesc Health Care. 2010 Jul 1;47(1):51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ko C-H, Yen J-Y, Yen C-F, Lin H-C, Yang M-J. Factors predictive for incidence and remission of internet addiction in young adolescents: a prospective study. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007 Aug;10(4):545–51. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.9992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young KS. Internet Addiction: The Emergence of a New Clinical Disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998;1(3):237–44. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM, Gentile DA. The Internet Gaming Disorder Scale. Psychol Assess. 2015 Jun;27(2):567–82. doi: 10.1037/pas0000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sim T, Gentile DA, Bricolo F, Serpelloni G, Gulamoydeen F. A Conceptual Review of Research on the Pathological Use of Computers, Video Games, and the Internet. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2012 Oct 1;10(5):748–69. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Männikkö N, Billieux J, Kääriäinen M. Problematic digital gaming behavior and its relation to the psychological, social and physical health of Finnish adolescents and young adults. J Behav Addict. 2015 Dec;4(4):281–8. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pápay O, Urbán R, Griffiths MD, Nagygyörgy K, Farkas J, Kökönyei G, et al. Psychometric properties of the problematic online gaming questionnaire short-form and prevalence of problematic online gaming in a national sample of adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013 May;16(5):340–8. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carbonell X, Guardiola E, Fuster H, Gil F, Panova T. Trends in Scientific Literature on Addiction to the Internet, Video Games, and Cell Phones from 2006 to 2010. Int J Prev Med. 2016 Apr 1;7:63. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.179511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Billieux J, Pontes HM. The evolution of Internet addiction: A global perspective. Addict Behav. 2016 Feb;53:193–5. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Karila L, Billieux J. Internet Addiction: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Research for the Last Decade. MUD: Social gaming from text to video Games and Culture. 2006;1(4):397–413. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuss DJ, Lopez-Fernandez O. Internet addiction and problematic Internet use: A systematic review of clinical research. World J Psychiatry. 2016 Mar 22;6(1):143–76. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Przybylski AK, Weinstein N, Murayama K. Internet Gaming Disorder: Investigating the Clinical Relevance of a New Phenomenon. Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Nov 4; doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16020224. appiajp201616020224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gentile D. Pathological video-game use among youth ages 8 to 18: a national study. Psychol Sci. 2009 May;20(5):594–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khazaal Y, Chatton A, Rothen S, Achab S, Thorens G, Zullino D, et al. Psychometric properties of the 7-item game addiction scale among french and German speaking adults. BMC Psychiatry. 2016 May 10;16:132. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0836-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gentile DA, Choo H, Liau A, Sim T, Li D, Fung D, et al. Pathological video game use among youths: a two-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2011 Feb;127(2):e319–29. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM, Peter J. The effects of pathological gaming on aggressive behavior. J Youth Adolesc. 2011 Jan;40(1):38–47. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9558-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang C-W, Chan CLW, Mak K-K, Ho S-Y, Wong PWC, Ho RTH. Prevalence and correlates of video and internet gaming addiction among Hong Kong adolescents: a pilot study. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014 Jun 16;2014:874648. doi: 10.1155/2014/874648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petry NM, O’Brien CP. Internet gaming disorder and the DSM-5. Addiction. 2013 Jul;108(7):1186–7. doi: 10.1111/add.12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yen C-F, Yen J-Y, Ko C-H. Internet addiction: ongoing research in Asia. World Psychiatry. 2010 Jun;9(2):97. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Durkee T, Kaess M, Carli V, Parzer P, Wasserman C, Floderus B, et al. Prevalence of pathological internet use among adolescents in Europe: demographic and social factors. Addiction. 2012 Dec;107(12):2210–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Welte JW, Wieczorek WF, Barnes GM, Tidwell M-C, Hoffman JH. The relationship of ecological and geographic factors to gambling behavior and pathology. J Gambl Stud. 2004 Winter;20(4):405–23. doi: 10.1007/s10899-004-4582-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vasiliadis SD, Jackson AC, Christensen D, Francis K. Physical accessibility of gaming opportunity and its relationship to gaming involvement and problem gambling: A systematic review. Journal of Gambling Issues. 2013:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slutske WS, Deutsch AR, Statham DJ, Martin NG. Local area disadvantage and gambling involvement and disorder: Evidence for gene-environment correlation and interaction. J Abnorm Psychol. 2015 Aug;124(3):606–22. doi: 10.1037/abn0000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Konkolÿ Thege B, Woodin EM, Hodgins DC, Williams RJ. Natural course of behavioral addictions: a 5-year longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry. 2015 Jan 22;15:4. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0383-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strittmatter E, Parzer P, Brunner R, Fischer G, Durkee T, Carli V, et al. A 2-year longitudinal study of prospective predictors of pathological Internet use in adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet] 2015 Nov 2; doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0779-0. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00787-015-0779-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Van Rooij AJ, Schoenmakers TM, Vermulst AA, Van den Eijnden RJJM, Van de Mheen D. Online video game addiction: identification of addicted adolescent gamers. Addiction. 2011 Jan;106(1):205–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schou Andreassen C, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z, Mazzoni E, et al. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016 Mar;30(2):252–62. doi: 10.1037/adb0000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu J, Shen L-X, Yan C-H, Hu H, Yang F, Wang L, et al. Personal characteristics related to the risk of adolescent internet addiction: a survey in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health. 2012 Dec 22;12:1106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jerald J, Block MD. Issues for DSM-V: Internet Addiction. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):306–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu K-W, Chan WSC, Wong PWC, Yip PSF. Internet addiction: prevalence, discriminant validity and correlates among adolescents in Hong Kong. Br J Psychiatry. 2010 Jun;196(6):486–92. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Starcevic V, Aboujaoude E. Internet addiction: reappraisal of an increasingly inadequate concept. CNS Spectr. 2016 Feb;1:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S1092852915000863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young KS. The evolution of Internet addiction. Addict Behav. 2017 Jan;64:229–30. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aboujaoude E. Problematic Internet use: an overview. World Psychiatry. 2010 Jun;9(2):85–90. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baggio S, Dupuis M, Studer J, Spilka S, Daeppen J-B, Simon O, et al. Reframing video gaming and internet use addiction: empirical cross-national comparison of heavy use over time and addiction scales among young users. Addiction. 2016 Mar;111(3):513–22. doi: 10.1111/add.13192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Charlton JP, Danforth IDW. Distinguishing addiction and high engagement in the context of online game playing. Comput Human Behav. 2007;23(3):1531–48. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Billieux J, Schimmenti A, Khazaal Y, Maurage P, Heeren A. Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. J Behav Addict. 2015 Sep;4(3):119–23. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wittek CT, Finserås TR, Pallesen S, Mentzoni RA, Hanss D, Griffiths MD, et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Video Game Addiction: A Study Based on a National Representative Sample of Gamers. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2016;14(5):672–86. doi: 10.1007/s11469-015-9592-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Petry NM, Rehbein F, Gentile DA, Lemmens JS, Rumpf H-J, Mößle T, et al. Internet gaming and addiction: a reply to King & Delfabbro. Addiction. 2014 Sep 1;109(9):1567–8. doi: 10.1111/add.12549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Park JH, Han DH, Kim B-N, Cheong JH, Lee Y-S. Correlations among Social Anxiety, Self-Esteem, Impulsivity, and Game Genre in Patients with Problematic Online Game Playing. Psychiatry Investig. 2016 May;13(3):297–304. doi: 10.4306/pi.2016.13.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferguson CJ, Coulson M, Barnett J. A meta-analysis of pathological gaming prevalence and comorbidity with mental health, academic and social problems. J Psychiatr Res. 2011 Dec;45(12):1573–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koob GF, Buck CL, Cohen A, Edwards S, Park PE, Schlosburg JE, et al. Addiction as a stress surfeit disorder. Neuropharmacology. 2014 Jan;76(Pt B):370–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petry NM, Rehbein F, Gentile DA, Lemmens JS, Rumpf H-J, Mößle T, et al. An international consensus for assessing internet gaming disorder using the new DSM-5 approach. Addiction. 2014 Sep;109(9):1399–406. doi: 10.1111/add.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]