Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Disclosing amyloid status to cognitively normal individuals remains controversial given our lack of understanding the test’s clinical significance and unknown psychological risk.

METHODS

We assessed the effect of amyloid status disclosure on anxiety and depression before disclosure, at disclosure, and 6-weeks and 6-months post-disclosure and test-related distress after disclosure.

RESULTS

Clinicians disclosed amyloid status to 97 cognitively normal older adults (27 had elevated cerebral amyloid). There was no difference in depressive symptoms across groups over time. There was a significant group by time interaction in anxiety, although post-hoc analyses revealed no group differences at any time point, suggesting a minimal non-sustained increase in anxiety symptoms immediately post-disclosure in the elevated group. Slight but measureable increases in test-related distress were present after disclosure and were related to greater baseline levels of anxiety and depression.

DISCUSSION

Disclosing amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal adults in the clinical research setting with pre- and post-disclosure counseling has a low risk of psychological harm.

Keywords: amyloid PET imaging, depression, anxiety, truth disclosure, diagnostic imaging, preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, biomedical ethics, safety

1 Introduction

Molecular imaging techniques allow the in vivo detection of amyloid plaques in the brain, a hallmark neuropathological feature of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1]. This technique has stimulated a new era of prevention studies focused on the 20 – 40% of cognitively normal adults who have evidence of cerebral amyloid deposition at levels similar to those observed in people with AD [2–5].

The clinical relevance of the presence of amyloid plaques in the absence of cognitive symptoms remains imprecisely defined at the individual level. Early studies are mixed [6] but suggest cerebral amyloid is associated with greater mean rates of cognitive decline [3, 7, 8] and brain atrophy [9,10] at a group level. Additionally, the odds of developing AD over time are higher for those with an elevated amyloid level compared to those with non-elevated cerebral amyloid [11]. Not all individuals with cerebral amyloid, however, progress to dementia. Currently, precise estimates of the magnitude and timeframe for future risk of dementia are not available although imaging and pathological studies suggest plaques may accumulate up to 10 to 15 years prior to the onset of clinically recognized dementia [12].

Prevention trials are increasingly leveraging this potential window of opportunity using amyloid imaging to enrich a clinical trial sample with individuals at higher risk of developing AD. Based on trial design, these studies necessitate disclosing amyloid PET results to the individuals enrolled, raising ethical and safety issues. The psychological and behavioral impact of amyloid PET disclosure is currently not well described [13]. One small study [14] of only 4 participants found no evidence of deleterious psychological effects. Other survey-based studies of individuals who had not been scanned suggested some may use the information to plan ending their life [15–16]. Thus, understanding the psychological impact of disclosing amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal adults remains important.

We examined the safety and tolerability of disclosure in an ongoing study testing the effects of exercise on cognitively normal individuals with elevated cerebral amyloid (the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Prevention through Exercise [APEX] Trial). We assessed measures of anxiety, depression, and distress at baseline, day of disclosure, and at 6-weeks and 6-months post-disclosure.

2 Methods

The APEX study is a randomized trial examining the effects of aerobic exercise on AD biomarkers (amyloid burden and MRI volumetrics) and cognitive decline in cognitively normal older adults 65 years and older (NCT02000583) conducted at the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center. Participants are screened with amyloid PET imaging and those with elevated cerebral amyloid are randomized to 52 weeks of aerobic exercise vs. a stretching/toning control intervention (2:1 ratio) conducted under supervision at community based exercise facilities. For this study, we used data collected on the first n = 101 participants who were screened with amyloid PET imaging and completed.

Participants complete a standard in-person clinical and cognitive evaluation through the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center to exclude dementia or mild cognitive impairment. A trained clinician completes a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [17–18] and a psychometrician performs a neuropsychological test battery. Clinical and cognitive data are reviewed at a consensus diagnostic conference and cognitively normal participants are defined as having a CDR 0 and no clinically significant deficits on neuropsychological testing. Participants are also required to be sedentary or underactive based on the Telephone Assessment of Physical Activity [19] (score of 4 or less) and willing to participate in a 52 week exercise intervention. Family history of dementia was ascertained by participant self-report of late-life cognitive impairment or behavior change in a first degree relative (National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set, version 2 and 3) [20]. Exclusion criteria included clinically significant depression or anxiety per clinician impression or as indicated by exceeding cut points on the Geriatric Depression Scale [21] (GDS ≥ 5) or Beck Anxiety Index [22] (BAI > 16). Participants meeting these criteria proceed to florbetapir PET scanning to screen for those with elevated amyloid who are eligible for enrollment into the one-year exercise trial. All participants provide institutionally approved informed consent prior to participating.

2.1 Disclosure Process

Florbetapir PET scanning and disclosure involves three in-person visits (pre-scan counseling visit, amyloid PET scanning visit, and disclosure visit) and 6-week and 6-month follow up surveys by email or phone.

2.1.1 Pre-Scan Counseling

Participants are provided a detailed Participant Guide (see supplementary material) for review at home prior to their pre-scan counseling session. The guide provides information on AD, amyloid, amyloid imaging and the possible results of amyloid imaging. An in-person counseling visit is conducted to discuss the amyloid PET scan, possible results (elevated vs. non-elevated), limitations of the scan (it is not a diagnostic test), and to ensure the participant remains interested in obtaining the scan and learning the result. A clinician meets with the participant, reviews the Participant Guide, and answers questions. We developed general talking points (see supplementary material) which provide the clinician with an outline for guiding the discussion. First, the clinician discusses known AD risk factors of age, family history, and modifiable AD-related risk factors (i.e., cardiovascular-related risk factors) and introduces the concept of amyloid PET scanning as a risk factor for developing AD. Next, amyloid is explained as something present in those with AD and about 1/3 of those age 65 and older without evidence of cognitive decline. The two possible results (elevated vs. non-elevated) are next explained. An elevated result is explained to mean an individual is at higher risk of developing AD, stressing that this does not mean an individual will develop AD or has AD currently. A result of non-elevated indicates a lower risk, but not without risk, of developing AD. Additionally, we stress this is a new technique and that false positives and false negatives are possible. Scan results are not shared with the participant’s physicians or entered into the medical record.

2.1.2 Amyloid Imaging and Scan Interpretation

PET images are obtained on a GE Discovery ST-16 PET/CT scanner after administration of intravenous florbetapir F-18 (370 MBq). Two PET brain frames of five minutes in duration were acquired continuously, approximately 50 minutes post-injection of the florbetapir. Frames were then summed and attenuation corrected prior to interpretation. MIMneuro software (MiM Software Inc, Cleveland, OH) quantitatively normalized the amyloid-β PET image to the entire cerebellum to calculate the Standard Uptake Value Ratio (SUVR) for six regions of interest (ROIs): anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate, precuneus, inferior medial frontal, lateral temporal, and superior parietal cortex. Three trained raters reviewed the visual images, the quantitative SUVR ROI data, and MIMneuro-generated cortical projections of amyloid burden (z-scores comparing the SUVRs to an SUVR map of 74 individuals (48 males, 26 females) between the ages of 18 – 50) to assess the scans as “elevated” or “non-elevated”, incorporating both visual and quantitative information into their assessment. The final determination of elevated or non-elevated is determined by majority (i.e., ≥ 2 raters in agreement).

2.1.3 Disclosure Visit

Participants return for an in-person disclosure session with attempts to maintain continuity with the same clinician who performed pre-scan counseling. This visit is structured similar to the pre-scan counseling visit. We review the purpose of the scan to detect amyloid and the potential results using the same general talking points, fully describing the meaning of both an elevated and non-elevated scan, regardless of the result. After answering any questions, the result is disclosed followed by another thorough explanation of the meaning of that result using similar language and talking points.

2.2 Outcomes

We obtained outcome measures of depression and anxiety at pre-scan counseling visit, disclosure visit, and 6-weeks and 6 months post-disclosure using the Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression Scale [23] (CES-D) and the BAI. This approach was modeled on that used by the REVEAL study [24]. We also assessed the psychological impact of disclosure at 6-weeks and 6-months using a modified version of the distress subscale (12 items) from the Impact of Genetic Testing for Alzheimer’s Disease (IGT-AD) [25]. We modified the test response options for the IGT-AD from the original (0, 1, 3, and 5) to include the full range (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) to create a more broad response approach across the various surveys given during the same session. At in-person visits, participants completed these evaluations on a computer after being provided with instructions from a coordinator who was also available if questions arose. At 6-weeks and 6-months, participants were emailed a link to complete identical computerized forms at home. If a clinically-relevant increase in depressive and anxiety symptoms was observed by the clinician or scores increased on the CESD more than 10 points or on the BAI more than 15 points a licensed psychologist was available for follow up as needed.

2.3 Statistics

Group differences (amyloid elevated vs. non-elevated) in demographic and descriptive variables were examined using t-tests and chi-square tests of independence. Independent-samples t-tests were used to test for group differences in age, education, Mini-Mental State Exam, anxiety, depression, and total distress by amyloid status. Repeated measures ANOVA were used to assess for group differences in how levels of anxiety symptoms (BAI) or depression (CES-D) changed over time. Significant interaction terms were explored with post-hoc group comparisons at each timepoint. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated at each timepoint for BAI and CES-D. Mann-Whitney U tests were used to test for group differences for the summary and individual items on the IGT-AD distress scale. Finally, we assessed the relationship of baseline depression and anxiety to post-disclosure distress using Spearman rank correlation in the overall group combined. All analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 24).

3 Results

3.1 Demographics

We examined data from 101 consecutive participants. One participant was excluded at screening for exceeding our upper limit on depressive symptoms (GDS score greater than 5). Three participants withdrew from the study after pre-scan counseling with the clinician that suggested they had increased anxiety and concern about learning their test results. The remaining 97 individuals had amyloid PET scans and were included in analyses (Table 1). Of these, 27 participants (28%) had elevated amyloid. The sample was well-educated and predominately Caucasian. There were no significant differences for age, education, sex, race, or family history of dementia by amyloid status.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Amyloid Elevated (N = 27) | Amyloid Non-Elevated (N = 70) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 73.1 (4.8) | 71.2 (5.7) |

| Education, years | 16.2 (3.0) | 16.8 (2.4) |

| Female, N (%) | 14 (51.9%) | 45 (64.3%) |

| Caucasian, N (%) | 27 (100%) | 67 (95.7) |

| Hispanic, N (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.4%) |

| Family History, N (%) | 3 (11.1%) | 11 (15.7%) |

| MMSE | 29.2 (0.9) | 29.1 (1.2) |

| STAI | 33.9 (5.5) | 33.8 (5.3) |

| BAI Pre-Scan | 3.7 (3.1) | 3.7 (4.0) |

| BAI Disclosure | 4.3 (4.6) | 3.7 (3.6) |

| BAI 6 Weeks | 2.6 (2.9) | 3.5 (4.1) |

| BAI 6 Months | 2.6 (3.0) | 3.6 (4.2) |

| CES-D Pre-Scan | 3.7 (4.5) | 3.4 (4.1) |

| CES-D Disclosure | 4.0 (5.4) | 4.0 (4.2) |

| CES-D 6 Weeks | 2.5 (2.1) | 3.9 (5.2) |

| CES-D 6 Months | 3.7 (4.3) | 4.2 (4.4) |

All values are means (SD) unless otherwise noted. Family history reported by participant includes any cognitive or behavioral change in biological parents, full siblings and biological children. No differences were observed across groups (all p values > 0.05). MMSE = Mini-mental State Exam; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; CES-D = Centers of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

3.2 Depression and Anxiety

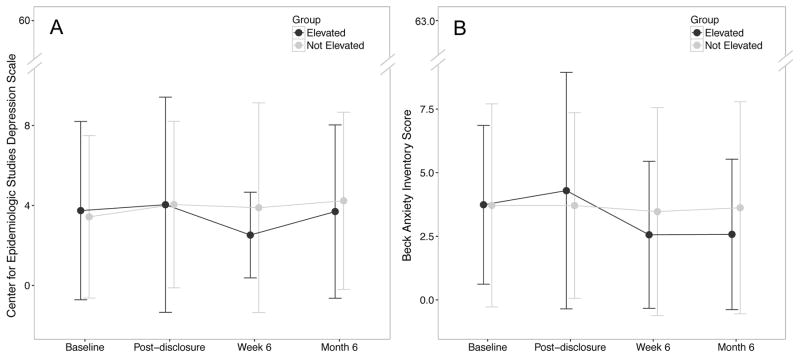

Means and standard deviations for the BAI and CES-D for each study visit are presented in Table 1 and illustrated in the Figure. Depressive symptoms were stable across visits and not different between groups (F (3, 270) = 0.97, p = 0.40). Analyses of anxiety indexed by BAI suggest a slight but significant group difference in change in anxiety symptoms over time (F (3, 270) = 3.14, p = 0.03) that visually appeared to peak at disclosure for elevated individuals. However, post-hoc analyses revealed no group differences at any time point (p > 0.2) suggesting minimal differences in anxiety due to disclosure of elevated or non-elevated status (Cohen’s d range from 0 to 0.15). The mean BAI at disclosure for the amyloid elevated group was 4.3 points, within the minimal anxiety range for the BAI [22]. Three individuals had increases in depressive symptoms (change in CES-D > 10) triggering contact, per protocol, from the study’s clinical psychologist. Two of these individuals had non-elevated cerebral amyloid and were without a family history of dementia. One individual had elevated amyloid and a family history of dementia. In all three cases, the rise in reported psychological symptoms was related to personal affairs unrelated to disclosure (e.g. death or serious illness in friends or family). One of these individuals was referred to clinical psychologist for behavioral support and grief counseling.

Figure 1. Anxiety and Depression Symptoms Before and After Disclosure.

Data at baseline, immediately post-disclosure (day of disclosure), and 6-weeks and 6 months post disclosure on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (Panel A) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Panel B). There was no difference in depressive symptoms across groups over time. A minimal increase in anxiety symptoms was apparent immediately post-disclosure in the amyloid elevated group but was not sustained over time.

3.3 Disclosure-Related Distress

Individuals with elevated amyloid had higher total levels of test-related distress as measured by the IGT-AD scale (Table 2) compared to the non-elevated amyloid group at 6-weeks (U=422.5, p < 0.001) and 6-months (U=564.5, p < 0.015) after disclosure. Small differences were observed across groups for the majority of the individual items of the scale although item level differences were small with mean values for elevated amyloid participants generally below 1.0 (corresponding to “very rarely” endorsing these symptoms). At 6 months, 84.6% (n = 22 of 26 with complete data) reported “never” regretting obtaining their test result with n = 2 reporting “very rarely” and n = 2 “infrequently” reporting “regret”; no one reported “sometimes” or more often regretting obtaining their test result. Across the 12 IGT-AD items at 6 months, 95.2% of all responses from amyloid elevated participants suggested “infrequent” or less concern for test-related distress symptoms (compared to 97.6% of the amyloid non-elevated group). Only 2 amyloid-elevated participants reported “frequent” concerns on any item: n = 1 for item 6 “worry about risk of AD” and n = 1 for item 9 “frustration about lack of AD prevention guidelines”. Item-wise IGT-AD scores for all participants can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 2.

IGT-AD Distress Subscale Statistics

| Item | 6 Weeks | 6 Months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Elevated | Elevated | Non-Elevated | Elevated | |

| Upset about my test results | 0.10 (0.60) | 0.60 (1.04)† | 0.09 (0.41) | 0.31 (0.62)* |

| Sad about my test result | 0.07 (0.40) | 0.64 (1.04) † | 0.06 (0.38) | 0.42 (0.64) † |

| Anxious about test result | 0.06 (0.38) | 0.56 (0.96) † | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.35 (0.56) † |

| Perceived loss of control | 0.22 (0.68) | 0.24 (0.52) | 0.29 (0.79) | 0.31 (0.68) |

| Problems enjoying life because of test result | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.12 (0.44)* | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.08 (0.27)* |

| Worry about risk of AD | 0.35 (0.66) | 1.24 (1.13) † | 0.43 (0.78) | 1.00 (1.20)* |

| Uncertain about what test means for my AD risk | 0.26 (0.63) | 1.00 (1.38) † | 0.26 (0.78) | 0.69 (1.01) † |

| Uncertain about what test means for children/family’s AD risk | 0.28 (0.70) | 0.88 (1.01) † | 0.23 (0.69) | 0.77 (1.07) † |

| Frustration due to lack of AD prevention guidelines | 0.35 (0.78) | 0.88 (1.13)* | 0.39 (0.93) | 0.92 (1.20) † |

| Concern regarding how test result will affect insurance status | 0.07 (0.40) | 0.20 (0.58) | 0.09 (0.33) | 0.04 (0.20) |

| Perceived difficulty talking about test result with family | 0.01 (0.12) | 0.30 (0.76) † | 0.04 (0.21) | 0.17 (0.38) |

| Regret about getting test results | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.28 (0.68) † | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.23 (0.59) † |

| IGT Distress Total | 1.77 (3.73) | 7.17 (8.54) | 1.91 (3.65) | 5.29 (6.08)* |

Items scored on a 0 – 5 scale with 0= Never, 1 = very rarely, 2 = infrequently, 3 = sometimes, 4 = frequently, and 5 = very often. Mann-Whitney U Tests used for individual items. Independent-samples t-test used for IGT-Distress Total Score.

p < .05

p < .01

3.4 Baseline Anxiety and Depression as Predictors of Distress

We also examined whether anxiety and depression at baseline (before disclosure) were related to total distress as measured by the IGT at 6-weeks and 6 months in the overall group combined. Baseline anxiety predicted total distress at 6 weeks (r = 0.28, p = 0.008) and 6 months (r = 0.356, p < 0.001). Baseline depression symptoms were marginally associated with distress at 6 weeks (r = 0.201, p = 0.055) and moderately correlated at 6 months (r = 0.312, p = 0.002).

4 Discussion

Disclosing amyloid PET results to cognitively normal older adults in the clinical research setting appears to be safe and well-tolerated. We observed no effects of disclosure on depressive symptoms while anxiety symptoms peaked at a low level on the day of disclosure but were not sustained at 6-weeks or 6 months. Measures of test-related distress was slightly higher in those with elevated amyloid compared to amyloid non-elevated participants but these effects were small with 95.2% of all responses for the amyloid elevated group at a level of infrequent, rare, or never occurring. No amyloid elevated participants regretted obtaining their amyloid PET imaging result at a level of sometimes or more. Thus, disclosing amyloid status to cognitively normal older adults provokes minor increases in anxiety and test-related distress that are mild and well-tolerated over 6 months.

Our data demonstrates that our process for disclosing amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal older adults in a clinical research setting is generally safe. Our process is similar to other disclosure methods for individuals with mild cognitive impairment [26] and the large, multi-site Anti-Amyloid Treatment for Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease (A4) trial, though it should be noted that our methods and the language in our Participant Guide were provided to the A4 study team as they developed their methods [27]. Key elements of the process include providing participants with written materials prior to enrollment followed by pre-scan counseling and day of disclosure counseling. We pay careful attention to the language used in our written materials and during counseling to frame and conceptualize the results for participants. We developed talking points (see supplementary material) that are used to guide three largely redundant discussions that occur at 1) pre-scan counseling, 2) just prior to disclosure, and 3) again immediately after disclosure. These talking points conceptually frame the imaging results as a risk factor for an elevated risk of developing AD over time rather than as a diagnostic test. We repetitiously stress key points such as an elevated test result does not mean one has AD nor will someone with elevated amyloid definitively develop AD. Additionally, we are careful to refer to the two possible results throughout our written and spoken language using the terms “elevated” or “non-elevated” rather than as “positive” or “negative” given potential for confusion in interpreting “positive” as beneficial and “negative” as unfavorable.

Our data suggest that personality features such as baseline levels of anxiety (BAI) and depression (CES-D) may play a role in how individuals interpret and react to complex health information. We found that higher levels of anxiety and depression at baseline were modestly predictive of higher levels of test-related distress at follow-up. Although this initial report is focused on safety and tolerability, we are currently assessing how well amyloid imaging information is understood and retained, an especially important issue as a prior survey-based study suggests that up to 32.6% of individuals failed to understand basic information regarding the meaning of biomarker tests [15].

Our methods also include screening for anxiety and depression prior to enrollment using both clinician judgment and formal assessments of depression (CES-D) and anxiety (BAI). Four individuals who were enrolled into the study withdrew after discussions with the clinician (n = 3) or were excluded based on exceeding the cut point for depressive symptoms (n = 1). The three participants who withdrew scored within the acceptable range on the CES-D and BAI but their interaction with the clinician uncovered anxiety and concern about learning their test results, underscoring the importance of the clinical interaction and clinician judgment, which cannot be replaced by survey-based instruments. Though we did not formally collect data on study partners or require their presence during counseling sessions, we believe it is important to encourage their inclusion in the disclosure process. We had at least one potential participant who declined screening due to the views of his wife “not wanting to know.” Thus, attention to the views of family members and their understanding of the meaning of the test should not be overlooked.

The study is limited by a select research sample of older adults willing and able to participate in a one-year exercise trial. This significantly limits the generalizability of the study results. As a result, although our data support the position that disclosing amyloid PET results is safe in a clinical research setting, we do not believe our data extend to a broad clinical setting for cognitively normal older adults interested in risk assessments, consistent with our prior recommendations [28]. Additionally, Appropriate Use Criteria [29] recommend amyloid imaging for individuals with mild cognitive impairment or dementia of unclear etiology or atypical course. Until effective prevention strategies are proven and widely available, we believe disclosure of amyloid PET results in cognitively normal older adults should remain confined to the clinical research population. An additional limitation that affects the generalizability of these results is that the majority (24 of 27) of amyloid elevated participants were enrolled in a one-year exercise trial after receiving their amyloid PET results. Anxiety symptoms appear to drop somewhat at 6 weeks and 6 months compared to symptoms observed on the day of disclosure. It is possible that enrolling into a one-year exercise trial may provide some relief to participants as they take action against their apparently increased risk. Further studies of whether having elevated amyloid provides motivation to change healthy behaviors is ongoing in our study. Our study is also limited by a lack of information on suicidal ideation, which is a potential negative outcome reported in other survey based studies of risk disclosure [15]. Lastly, our sample size of those with a family history of dementia was small and precluded in-depth analyses of the role family history may play in driving psychological response to disclosure.

Our knowledge of the clinical relevance of amyloid PET will evolve quickly and lead to more precise risk estimates for individuals. As these changes occur, the research field should continue to assess the ethical and behavioral implications of research disclosure and work to carefully manage how this risk information is presented safely and effectively. This will be especially important until effective prevention strategies are developed and proven to impact an individual’s long-term risk. Currently, our data suggest that amyloid imaging results can be conveyed safely to individuals participating in clinical research studies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Disclosing amyloid PET results to cognitively normal older adults in the clinical research setting appears to be safe and well-tolerated.

Anxiety may transiently increase immediately upon disclosure of amyloid status but is not sustained.

Disclosure rarely resulted in clinically significant changes in anxiety or depression.

Post-disclosure distress is related to baseline levels of depression and anxiety symptoms.

Research in Context.

Systematic review: Literature was reviewed using PubMed and revealed few studies examining the psychological impact of disclosing amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal older adults.

Interpretation: We examined the psychological impact of disclosing amyloid imaging results using self-reported measures of depression, anxiety, and distress. Results showed no effect on depressive symptoms and a small peak in anxiety symptoms on the day of disclosure that was not sustained 6-weeks and 6-months later. Small elevations in test-related distress were present at 6-weeks and 6-months and were predicted by higher baseline depression and anxiety symptoms. This study supports the safety and tolerability of disclosing amyloid imaging results in the setting of clinical research.

Future Directions: As knowledge of the clinical relevance of amyloid PET evolves, the research field should continue to assess the ethical and behavioral implications of disclosure to manage how this information is presented safely and effectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01 AG043962; P30 AG035982; and a gift from Frank and Evangeline Thompson. Lilly Pharmaceuticals provided a grant to support F18-AV45 doses and partial scan costs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, Wang Y, Blomqvist G, Holt DP, Bergström M, Savitcheva I, Huang GF, Estrada S, Ausén B, Debnath ML, Barletta J, Price JC, Sandell J, Lopresti BJ, Wall A, Koivisto P, Antoni G, Mathis CA, Långström B. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):306–19. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleisher AS, Chen K, Liu X, Roontiva A, Thiyyagura P, Ayutyanont N, Joshi AD, Clark CM, Mintun MA, Pontecorvo MJ, Doraiswamy PM, Johnson KA, Skovronsky DM, Reiman EM. Using positron emission tomography and florbetapir F18 to image cortical amyloid in patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia due to Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(11):1404–11. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Storandt M, Mintun MA, Head D, Morris JC. Cognitive decline and brain volume loss as signatures of cerebral amyloid-beta peptide deposition identified with Pittsburgh compound B: cognitive decline associated with Abeta deposition. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1476–81. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, Dence CS, Lee SY, Mach RH, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, DeKosky ST, Morris JC. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(3):446–52. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aizenstein HJ, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, Price JC, Mathis CA, Tsopelas ND, Ziolko SK, James JA, Snitz BE, Houck PR, Bi W, Cohen AD, Lopresti BJ, DeKosky ST, Halligan EM, Klunk WE. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(11):1509–17. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewers M, Insel P, Jagust WJ, Shaw L, Trojanowski JQ, Aisen P, Petersen RC, Schuff N, Weiner MW Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) CSF biomarker and PIB-PET-derived beta-amyloid signature predicts metabolic, gray matter, and cognitive changes in nondemented subjects. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22(9):1993–2004. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stomrud E, Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Minthon L, Londos E. Correlation of longitudinal cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers with cognitive decline in healthy older adults. Arch Neurol. 67:217–23. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Resnick SM, Sojkova J, Zhou Y, An Y, Ye W, Holt DP, Dannals RF, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Ferrucci L, Kraut MA, Wong DF. Longitudinal cognitive decline is associated with fibrillar amyloid-beta measured by [11C]PiB. Neurology. 2010;74(10):807–15. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d3e3e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jack CR, Jr, Lowe VJ, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Senjem ML, Knopman DS, Shiung MM, Gunter JL, Boeve BF, Kemp BJ, Weiner M, Petersen RC Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Serial PIB and MRI in normal, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: implications for sequence of pathological events in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 5):1355–65. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Archer HA, Edison P, Brooks DJ, Barnes J, Frost C, Yeatman T, Fox NC, Rossor MN. Amyloid load and cerebral atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease: an 11C-PIB positron emission tomography study. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(1):145–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.20889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JC, Roe CM, Grant EA, Head D, Storandt M, Goate AM, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA. Pittsburgh compound B imaging and prediction of progression from cognitive normality to symptomatic Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(12):1469–75. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR, Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bemelmans SA, Tromp K, Bunnik EM, Milne RJ, Badger S, Brayne C, Schermer MH, Richard E. Psychological, behavioral and social effects of disclosing Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers to research participants: a systematic review. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0212-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim YY, Maruff P, Getter C, Snyder PJ. Disclosure of positron emission tomography amyloid imaging results: A preliminary study of safety and tolerability. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:454–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caselli RJ, Marchant GE, Hunt KS, Henslin BR, Kosiorek HE, Langbaum J, Robert JS, Dueck AC. Predictive testing for Alzheimer’s disease: suicidal ideation in healthy participants. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015;29(3):252–4. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ott BR, Pelosi MA, Tremont G, Snyder PJ. A Survey of Knowledge and Views Concerning Genetic and Amyloid PET Status Disclosure. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;2:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412b–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatr. 1982;140:566–72. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayer CJ, Steinman L, Williams B, Topolski TD, LoGerfo J. Developing a Telephone Assessment of Physical Activity (TAPA) questionnaire for older adults. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, Cummings J, Decarli C, Ferris S, Foster NL, Galasko D, Graff-Radford N, Peskind ER, Beekly D, Ramos EM, Kukull WA. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(4):210–6. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213865.09806.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982–1983;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. App Psychol Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green RC, Roberts JS, Cupples LA, Relkin NR, Whitehouse PJ, Brown T, Eckert SL, Butson M, Sadovnick AD, Quaid KA, Chen C, Cook-Deegan R, Farrer LA REVEAL Study Group. Disclosure of APOE genotype for risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(3):245–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung WW, Chen CA, Cupples LA, Roberts JS, Hiraki SC, Nair AK, Green RC, Stern RA. A new scale measuring psychologic impact of genetic susceptibility testing for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(1):50–6. doi: 10.1097/wad.0b013e318188429e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lingler JH, Butters MA, Gentry AL, Hu L, Hunsaker AE, Klunk WE, Mattos MK, Parker LA, Roberts JS, Schulz R. Development of a Standardized Approach to Disclosing Amyloid Imaging Research Results in Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52(1):17–24. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harkins K, Sankar P, Sperling R, Grill JD, Green RC, Johnson KA, Healy M, Karlawish J. Development of a process to disclose amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal older adult research participants. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0112-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grill JD, Johnson DK, Burns JM. Should we disclose amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal individuals? Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2013;3(1):43–51. doi: 10.2217/nmt.12.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, Donohoe KJ, Foster NL, Herscovitch P, Karlawish JH, Rowe CC, Carrillo MC, Hartley DM, Hedrick S, Pappas V, Thies WH Alzheimer’s Association; Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging; Amyloid Imaging Taskforce. Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: a report ofthe Amyloid Imaging Task Force, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):e-1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.