Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is a rare cause of acute coronary syndrome and sudden cardiac death. The diagnosis of SCAD is based only on angiography in most of the studies (1-3) and the angiographic type 1 pattern is considered pathognomonic of an SCAD.

A 74-year-old man with history of smoking, hypertension and dyslipidemia was admitted at our center due to a minimum effort angina of recent onset, with neither ST changes in basal electrocardiogram nor troponin elevation. An echocardiogram showed preserved ejection fraction without regional wall motion abnormalities. His coronary angiography showed a 90% stenosis in the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) (Figure 1A,B, Figures S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Data) and the presence of a thin longitudinal radiolucent line along the LAD with extension to first diagonal branch suggesting a spontaneous coronary dissection (SCAD). Due to the Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) Score 3 flow and the absence of chest pain or ST segment changes at that moment, a conservative management was decided according to our SCAD protocol.

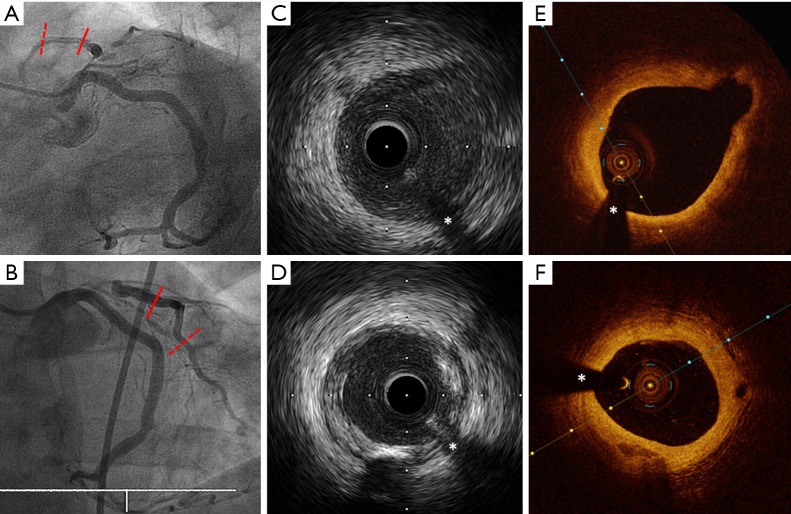

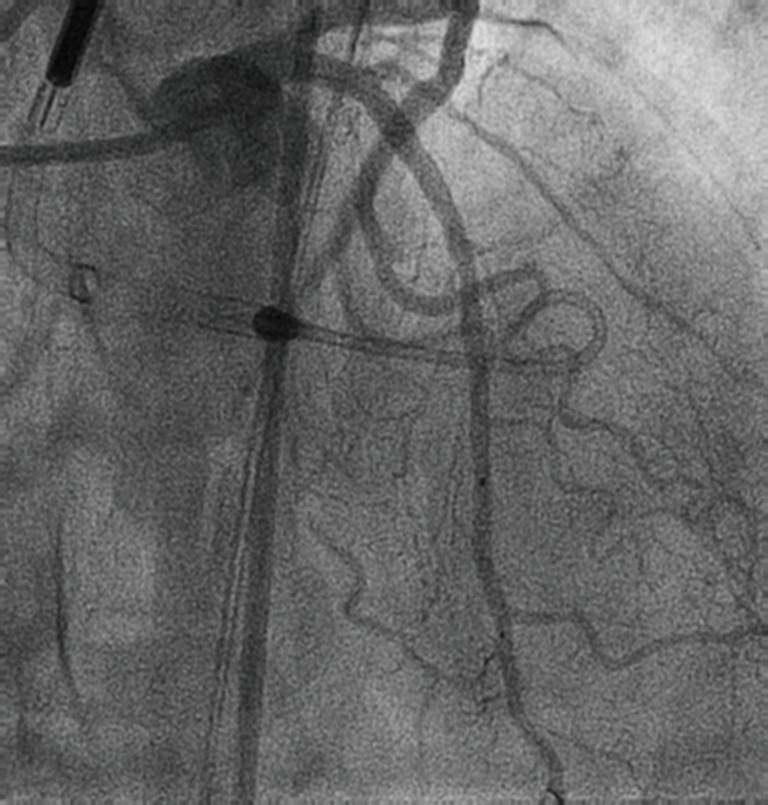

Figure 1.

Angiographic images (A,B): a thin longitudinal radiolucent line along the LAD with extension to first diagonal branch can be seen after a severe stenosis in the proximal LAD suggesting a spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD). This entity was discarded by both IVUS and OCT (C-F). Panels C and E (corresponding to the continuous red lines in the angiography pictures) show IVUS (C) and OCT (E) images of the LAD 10 mm distal to the severe LAD stenosis. Panels D and F (corresponding to the discontinuous red lines in the angiography pictures) show IVUS (D) and OCT (F) images of the mid-distal LAD. LAD, left anterior descending artery; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

Figure S1.

Left anterior oblique (LAO)/caudal view displaying a severe stenosis in the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) and the presence of a thin longitudinal radiolucent line along the LAD with extension to first diagonal branch suggesting a spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) (10). Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1629

Figure S2.

Right anterior oblique (RAO)/cranial view displaying a double-lumen appearance across the proximal LAD artery with preserved blood flow in distal segments, and the advancement of a wire across the proximal LAD stenosis (11). Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1630

A second coronariography performed five days later, showed the same angiographic image with neither coronary stenosis improvement nor the healing of the SCAD. We decided then to perform percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to the LAD with the support of an Impella 2.5 (Abiomed, Danvers, MA, USA), considering the risk of proximal migration of the dissection to the left main/ circumflex artery while stenting. After several attempts, two PCI wires were placed in the distal LAD and the diagonal branch. An intravascular ultrasound (IVUS Opticross, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) was performed before predilatation, and surprisingly, no coronary dissection was seen (Figure 1C,D). After predilatation with a 2.0/20 mm balloon, an optical coherence tomography (OCT Dragonfly OPTIS Imaging, St Jude Medical, St Paul, MN, USA) was performed, confirming also the absence of a SCAD (Figure 1E,F). A complicated atherosclerotic plaque was evidenced instead (Figure 2A,B). The procedure was successfully concluded with the implantation of a 3.5/18 mm Xcience Expedition everolimus eluting stent (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The longitudinal radiolucent line along the LAD disappeared after the stent implantation (Figure 3).

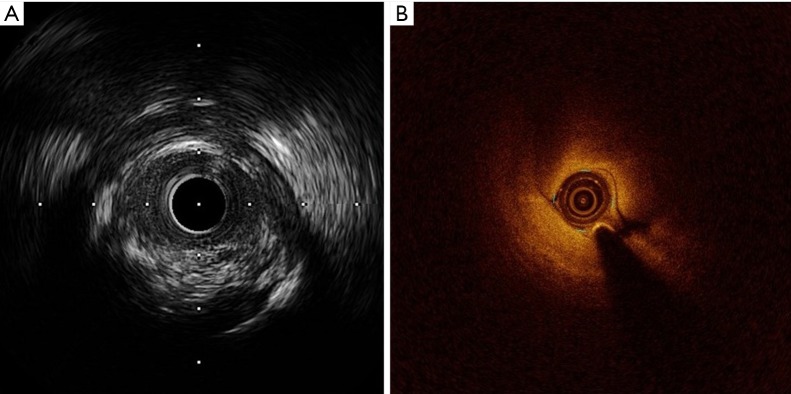

Figure 2.

IVUS (A) and OCT (B) images of proximal LAD stenosis. A fibrocalcific plaque causing severe stenosis was probed with both techniques. No evidence of intimal flap suggesting spontaneous coronary dissection was seen. IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; OCT, optical coherence tomography; LAD, left anterior descending artery.

Figure 3.

Final angiographic image after LAD angioplasty. The longitudinal radiolucent line along the LAD disappeared after stent implantation. LAD, left anterior descending artery.

SCAD is an infrequent cause of acute coronary syndrome. It is caused by a non-traumatic and non-iatrogenic separation of the coronary arterial layers, creating a false lumen. The diagnosis of SCAD is based only on angiography in most of the studies (1-3). Angiographic type 1 pattern is considered pathognomonic of an SCAD. It is characterized by a contrast dye staining of the arterial wall with multiple radiolucent lumens (4).

We present a case with a pathognomonic image of a type 1 SCAD where contrary to what is currently thought, was not due to an SCAD as demonstrated by both IVUS and OCT. The similar false image was seen during both, basal and 5 days control angiography. We believe that the severe stenosis produced by the atheroma plaque in the proximal LAD, induced the creation of distal laminar flows in the artery that simulated the presence of a false SCAD. Another possibility, such as a laminar thrombus, would be unlikely according to the accepted angiographic classification for coronary thrombi (5).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case showing that the so far considered pathognomonic pattern of SCAD, may not be due solely to a SCAD but also due to an atherosclerotic plaque causing severe stenosis.

Because coronary atherosclerotic plaques have different treatment and prognosis compared to SCAD (6,7), we should consider using intracoronary imaging techniques, such as intravascular ultrasound or mainly optical coherence tomography, in all SCAD suspicion in order to obtain a precise SCAD diagnosis. This has been advocated by other authors (2-4,8,9), but mainly restricted when the diagnosis of a SCAD by angiography is unclear (such as type 2 and 3 patterns of SCAD). In addition, IVUS and OCT provides further useful information, especially when angioplasty in planned. Both allow to determine the full longitudinal and circumferential extent of the SCAD, which is useful to select the stent size and length, and the involvement of the related side-branches. They are also useful to confirm the adequate guide-wire position within the true lumen during the PCI, and to detect residual intramural hematoma or distal dissections after stenting (9).

Finally, our finding may imply than some SCAD cases included in other studies could have been atheroma plaques instead of SCAD, which might explain the controversial prognostic data available in SCAD studies, and it highlights the capital role of the intracoronary imaging techniques in this entity.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Vrints CJ. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Heart 2010;96:801-8. 10.1136/hrt.2008.162073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Pitta SR, et al. Clinical features, and prognosis of spontaneous coronary management, artery dissection. Circulation 2012;126:579-88. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.105718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saw J, Ricci D, Starovoytov A, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: prevalence of predisposing conditions including fibromuscular dysplasia in a tertiary center cohort. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2013;6:44-52. 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saw J. Coronary angiogram classification of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2014;84:1115-22. 10.1002/ccd.25293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson CM, De Lemos JA, Murphy SA, et al. Combination therapy with abciximab reduces angiographically evident thrombus in acute myocardial infarction: a TIMI 14 substudy. Circulation 2001;103:2550-4. 10.1161/01.CIR.103.21.2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tweet MS, Eleid MF, Best PJ, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection revascularization versus conservative therapy. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7:777-86. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alfonso F, Paulo M, Lennie V, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: long-term follow-up of a large series of patients prospectively managed with a"conservative" therapeutic strategy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:1062-70. 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maehara A, Mintz GS, Castagna MT, et al. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Am J Cardiol 2002;89:466-8. 10.1016/S0002-9149(01)02272-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alfonso F, Paulo M, Gonzalo N, et al. Diagnosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection by optical coherence tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:1073-9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodríguez-González E, Goirigolzarri-Artaza J, Restrepo-Córdoba MA, et al. Left anterior oblique (LAO)/caudal view displaying a severe stenosis in the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) and the presence of a thin longitudinal radiolucent line along the LAD with extension to first diagonal branch suggesting a spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD). Asvide 2017;4:317. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1629

- 11.Rodríguez-González E, Goirigolzarri-Artaza J, Restrepo-Córdoba MA, et al. Right anterior oblique (RAO)/cranial view displaying a double-lumen appearance across the proximal LAD artery with preserved blood flow in distal segments, and the advancement of a wire across the proximal LAD stenosis. Asvide 2017;4:318. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1630