Abstract

This study examined experiences and explanations of depression amongst Xhosa-speaking pregnant women, mothers, and health workers in an urban township in Cape Town, South Africa. The study was conducted as part of formative research for a randomised controlled trial to develop and evaluate a task-sharing counselling intervention for maternal depression in this setting. We conducted qualitative semistructured interviews with 12 depressed and 9 nondepressed pregnant women and mothers of young babies, and 13 health care providers. We employed an in-depth framework analysis approach to explore the idioms, descriptions, and perceived causes of depression particular to these women, and compared these with the ICD-10 and DSM-5 criteria for major depression. We found that symptoms of major depression are similar in this township to those described in international criteria (withdrawal, sadness, and poor concentration), but that local descriptions of these symptoms vary. In addition, all the symptoms described by participants were directly related to stressors occurring in the women’s lives. These stressors included poverty, unemployment, lack of support from partners, abuse, and death of loved ones, and were exacerbated by unwanted or unplanned pregnancies and the discovery of HIV positive status at antenatal appointments. The study calls attention to the need for specifically designed counselling interventions for perinatal depression that are responsive to the lived experiences of these women and grounded in the broader context of poor socioeconomic conditions and living environments in South Africa, all of which have a direct impact on mental health.

Keywords: global mental health, idioms of distress, maternal depression, risk factors, social determinants, South Africa

Background and rationale

There is substantial debate regarding the experience of depression in diverse cultural contexts globally. While there is an urgent need to focus on the rapidly rising mental health burdens on the public health systems, through task-sharing to address the treatment gap, many interventions developed in Western countries may not be sufficiently culturally sensitive, or adequately consider the impact of social determinants on mental health, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs; Kirmayer & Pedersen, 2014; Patel, Inas, Cohen, & Prince, 2014; Summerfield, 2012; Swartz, 2012).

The impact of social determinants on mental health is especially pertinent for women in LMICs, where risk factors for depression are particularly high (Desjarlais, Eisenberg, Good, & Kleinman, 1995; Lund, Stansfeld, & DeSilva, 2014; O’Hara & Swain, 1996; Patel et al., 2010; Rahman et al., 2013). These include low socioeconomic status, poverty, financial stress, social and economic inequalities (Aneshensel, 2009; Flisher et al., 2007; Lund, Breen, et al., 2010; Lund et al., 2011; Patel et al., 2011; Patel & Kleinman, 2003), low education levels (Patel, Araya, Lima, Ludermir, & Todd, 1999; Saxena, Thornicroft, Knapp, & Whiteford, 2007), pregnancy (Cooper et al., 1999; Hartley et al., 2011), HIV status (Berger-Greenstein et al., 2007; Kagee & Martin, 2010), food insecurity (Lund et al., 2011; Lund, Kleintjes, Kakuma, & Flisher, 2010), noncommunicable diseases (Collins, Insel, Chockalingam, Daar, & Maddox, 2013; World Health Organisation [WHO], 2008) substance abuse, and exposure to violence and abuse (WHO, 2012).

Theoretical models for understanding the relationships between these risk factors have drawn attention to the notion of “life stressors” or “severe events” (defined as exposure to chronic and persistent stressors) being associated with risk for depression and poor health outcomes (Broadhead & Abas, 1998; Muhwezi, Agren, Neema, Maganda, & Musisi, 2008; Patel et al., 2010). For example, in the late 1990s, Broadhead and Abas found that the onset of depression in Harare, Zimbabwe was most frequently preceded by a “severe event” (Broadhead & Abas, 1998). This links with the work of Aneshensel (2009), who used the “stress process model” developed by Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman, and Mullan (1981) to advance theories on the effects of social inequalities, social stress, income, social status, and support, on depression. The model demonstrates how disadvantaged people experience more traumatic events than those from advantaged backgrounds, but have fewer resources to cope with these events (Aneshensel, 2009; Pearlin et al., 1981). Broadhead and Abas’s work demonstrates this theory through the presence of severe events and major difficulties in the women’s social worlds, which puts them at an elevated risk for depression.

In low-resource settings in South Africa, high rates of antenatal and postnatal depression have been reported. For example, in a peri-urban settlement in Cape Town, the prevalence of antenatal depression was found to be 39% (Hartley et al., 2011), and postnatal depression, 34.7% (Cooper et al., 1999). In rural KwaZulu Natal, a 41% prevalence of antenatal depression was found in 2006 (Rochat et al., 2006), and 47% in 2013 (Rochat, Tomlinson, Newell, & Stein, 2013). These rates are high compared to the rest of Africa, where prevalence rates of antenatal depression are between 4.3% and 17.4% (Sawyer, Ayers, & Smith, 2010), and LMICs worldwide, where antenatal depression is estimated at 15.6%, and postnatal depression at 19.8% (Fisher et al., 2012). In South Africa, typical pregnancy-related stressors include low and irregular income levels, lack of partner and family support, partner violence, and unplanned pregnancies (Hartley et al., 2011; Rochat et al., 2006).

Maternal mental health is recognised as a key factor in determining infant and child development (Surkan, Kennedy, Hurley, & Black, 2011). Both antenatal and postnatal depression have been shown to have negative impacts on child health and growth outcomes (Patel, DeSouza, & Rodrigues, 2003; Rahman, Harrington, & Bunn, 2002; Rahman, Iqbal, Bunn, Lovel, & Harrington, 2004; Surkan et al., 2011). Behaviour traits associated with depression in pregnant mothers affecting the unborn baby include: neglecting antenatal care and check-ups, inappropriate diet and poor weight gain, the use of harmful substances, and elevated risk of self-harm and suicide (Stewart, 2011; Wachs, Black, & Engle, 2009). Postnatal depression also predicts poor mother–infant relationships, child growth, temperament, and behavioural and cognitive development (Cooper et al., 2009, 1999; Field, Diego, & Hernandez-Reif, 2006; Grote et al., 2009; Patel et al., 2003; Rahman et al., 2004; Tsai & Tomlinson, 2012). Postnatal depression may also delay mothers in caring for their children’s illnesses (WHO, 2008). It is thus important for both mothers and their children that maternal mental health be improved through addressing perinatal depression.

Given the high prevalence of perinatal depression, its particular relationship with maternal and child health, and its elevated occurrence in LMICs, effective intervention strategies need to be researched and developed. Within the global discourse, it is important to develop localised understandings of depression in order to provide context-specific, acceptable, and effective interventions. Campbell and Burgess (2012) emphasise the importance of dialogue between communities, researchers, and service providers regarding how best to integrate ‘local’ and ‘global’ perspectives in optimising opportunities for well-being (Campbell & Burgess, 2012). They write that the research base needs to take into account local understandings and responses to mental illnesses in order to encourage agency among people who suffer from such conditions, and improve the acceptability and uptake of interventions. Mental health interventions thus need to resonate with communities’ own understandings, worldviews, and needs, in order to build their own internal capacities (Summerfield, 2012). Interventions should also be “driven by local knowledge” and “such knowledge should flow in both directions between the global south and the global north” (Patel, 2012 as cited in Bemme & D’Souza, 2012, p. 2).

In order to involve local perspectives in this debate, the concepts of the ‘everyday rhetoric’ and ‘idioms of distress’ for mental illness are used as a theoretical framework from which to explore the data. Everyday rhetoric includes ways of talking about depression in response to specific circumstances (Shotter, 1993; Symon, 2000). ‘Idioms of distress’ are defined as “socially and culturally resonant means of experiencing and expressing distress in local worlds” (Nichter, 2010, p. 405). These are brought about through the presence of past or present stressors, including experiences of anger, social insecurity, anxiety, and loss (Nichter, 2010). De Jong and Reis (2010) argue that particular idioms invite action within their context of local meaning, and will continue to be present until their aetiology, such as systemic or particular problems within the social, political, or economic environment, is exposed. In this way they differ from the ‘symptoms’ of an illness, which are used to more directly describe the features or indicators of an illness. Symptoms report on a condition; idioms often include “symbols, behaviors, language, or meanings” (Hollan, 2004, p. 63) that are used to express distress or suffering.

This paper therefore seeks to develop deep and localised understandings of the idioms of distress, symptoms, and perceived causes of perinatal depression in a community in Cape Town, South Africa, so that these may be used to inform a localised and culturally relevant intervention for perinatal depression in this area (Collins et al., 2013), and to inform health care providers of the idioms used to understand this common but often unidentified illness.

While investigating these understandings of depression, we also seek to conduct research that is relevant for global mental health; this is achieved by examining the relation between local idioms and symptoms, and the international criteria for depression. We thereby combine the local and global viewpoints in order to develop an understanding of a worldwide illness, which has similar symptoms across different contexts but is described using differing “indigenous idioms” of distress (Patel, Simunyu, & Gwanzura, 1995).

Methods

The study was conducted in the peri-urban township of Khayelitsha on the outskirts of Cape Town, South Africa. The settlement comprises approximately 400,000 residents, most of whom live in overcrowded and poor living conditions, with high levels of unemployment, poverty and crime, and low levels of education (Statistics SA, 2011). Many houses or shacks are without electricity, running water, or an indoor sewerage system. Many residents have moved to Cape Town from rural areas across South Africa, and the predominant language is Xhosa.

The study used a qualitative exploratory design. Participants were recruited from a Community Health Centre (CHC) Midwife Obstetric Unit (MOU) in Khayelitsha. An average of 15 women attend their first antenatal appointments at the MOU every day, and these women were approached and asked to participate in the screening on the designated study days. Likewise, mothers attending the baby clinic (with babies up to 1 year old) were also approached and asked to participate in the study. Only women who were 18 years or older, could speak English or Xhosa, lived in the area, and had the capacity to consent were asked to participate.

In total, 84 women agreed to participate, and were screened by a field worker with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screen (EPDS; Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987), which has been validated for use in South Africa (de Bruin, Swartz, Tomlinson, Cooper, & Molteno, 2004). This tool screened for depression, and if the women scored 13 or higher, they were further assessed and diagnosed using the Major Depression Module of the Mini Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) version 6.0 (Sheehan et al., 1998). The women who were diagnosed with a major episode of depression on the MINI were then interviewed about their descriptions and experiences of depression. Along with the depressed women, nine women who had EPDS scores under 10 were also interviewed in order to obtain views and experiences of depression from women who did not meet diagnostic criteria for depression. This was purposefully done in order to avoid a possible circular argument contending that women who had been screened with these screening tools tended to describe symptoms identified in those screening tools.

Along with these women, 13 health care providers were recruited for interviews using purposive sampling. They included six registered nurse midwives and three HIV counsellors who worked at the MOU, and four community health workers (CHWs) who service the area. The rationale for including health care providers was to gain a broader description of the perception of depression within the community, including those who care for and are expected to help women with depression.

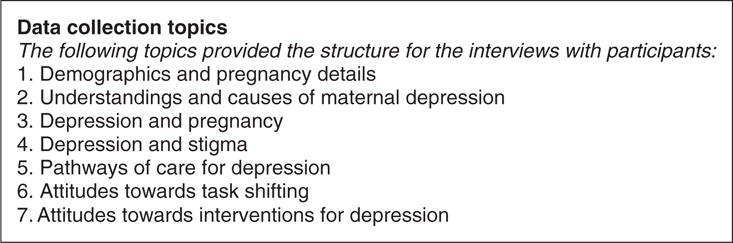

Data were collected using semistructured interviews to elicit descriptions of the participants’ indigenous idioms and explanations of maternal depression. The interviews covered a range of factors relating to maternal mental health, service utilization, and service need in the study area. Interview schedules were reviewed by research partners, translated into Xhosa and then back-translated to check for accuracy. The interviews with participants were audio recorded and then transcribed and translated into English by the transcriber. Figure 1 summarises topics covered in the interviews. The interviews were part of the formative research for the South African section of the Africa Focus on Intervention Research for Mental health (AFFIRM) study. This is an individual-level randomised controlled trial (RCT) to determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a task-sharing counselling intervention for perinatal depression in a low resource context in Cape Town (Lund, Schneider, et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

Data collection topics.

A framework analysis was employed for the data analysis. This approach is particularly useful in applied policy related research (Lacey & Luff, 2001; Ritchie & Spencer, 1994). The data were indexed and initial codes were guided to a certain degree by the semistructured interview topics, following the framework analysis approach. The analysis focused specifically on discovering themes related to symptoms and causes of depression. Further themes not captured by the initial coding were identified through extensive reading of the transcripts. Transcripts and data were managed using NVivo 8 qualitative data analysis software (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2014). Given the similarities between antenatal and postnatal women’s descriptions noted during the data collection phase, we decided to analyse these data together as one group.

The local symptoms were then compared with the published diagnostic criteria for an episode of major depression in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) diagnostic system (WHO, 2010) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) system (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The symptoms reported by participants were identified in the framework analysis prior and without reference to the diagnostic criteria from the DSM-5 and ICD-10.

Ethical approval was received from the University of Cape Town Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC Reference no. 226/2011). All participants received and signed informed consent forms for the study and were assured of confidentiality. Every participant screened by the fieldworker (positive or negative) was given a pamphlet with information on maternal depression and the available mental health services in the area (after their interviews if they were interviewed). The researchers referred a number of women with high EPDS scores to counselling and support NGOs in the area or to the psychiatric nurses at the CHC when participants demonstrated suicidal ideation.

In this small study of 84 consenting women, 29 screened positive for depression with the EPDS, and 12 were diagnosed with a current or past episode of major depression on the MINI 6.0. These 12 depressed women were interviewed, and nine nondepressed women were also interviewed. Of the 21 women in total, 15 were pregnant, and six were mothers of young babies. Their ages ranged between 21 and 41 years, and all women chose to be interviewed in Xhosa. Among women included in the study, EPDS scores ranged between 2 and 21. The midwives, HIV counsellors, and CHWs were all Xhosa speaking women and worked in and around the study site.

Results and discussion

Local idioms of distress

In order to discover local idioms of distress, the following question was asked:

The [EPDS] questions we just asked you mentioned things like blaming yourself, being anxious or worried or stressed, feeling scared, having difficulty sleeping, being sad, or feeling like harming yourself. [Depending on the symptoms the participant had identified.] What word or words would you use to describe the feelings I have just mentioned?

Health workers were asked, “What word or words would you use to describe depression?”

Some idioms of distress were similar to the symptoms identified by the participants (see following section), but others were distinct. The most common idioms correlated with the most common descriptions of symptoms, particularly in the sample of depressed women, including stress (i-stress/unxungu phalo), thinking too much (ucingakakhulu), being sad or unhappy (ukudakumba), and being scared (ukoyika). This may relate to the fact that there is no specific word in Xhosa for ‘depression,’ and thus identification of the illness may be linked more directly with the symptoms experienced.

In the interviews, i-stress was both a word used to describe the illness (e.g., “You end up with stress and sickness,” Pregnant Woman (PW) 15), and a nonpathological reaction to socioeconomic factors that may have induced the “stress/depression,” such as economic and social insecurity, particularly related to an unwanted pregnancy and a lack of support.

Being sad or unhappy and thinking too much were also direct descriptions of the impact/effect of depression. Thus, when asked to name the word(s) one would use for depression, the most accessible word (idiom) in this context might be one describing or expressing the feelings or meanings related to the unnamed illness or distress.

Along with these direct answers to the above questions, other idioms were also identified. Two women used the depiction of the sun setting on them when describing their depression: “It is bad; you feel the sun has set even though it’s morning. You don’t feel like yourself even when you are walking” (Mother [M] 3). Another said, “It is bad; even the sun you will see it has set. I don’t know how I would compare it. When I had these thoughts, they’d tell me the sun has set. I would just not sleep” (PW 8). These descriptions are a localised means of expressing distress (Nichter, 2010), emphasising that this illness, represented as darkness, is constantly present for these women: the sun has set and it is dark, “even though it is morning.”

A nondepressed woman (ND) brought many idioms into her description of depression, saying: “It’s when your brain is, is cramped … It’s not focused on who I’m talking to, the brain is busy, it’s under suffocation, and everything can just blow up right now” (ND 3).

Other less commonly mentioned idioms included suppression of the brain, the brain is tired, heart palpitations, mental disturbance, having pain, and you are like the weather. These all demonstrate a ‘reaching out’ for meaning amongst the women through developing an ‘everyday rhetoric,’ using symbols or language (Hollan, 2004) that may not directly identify the illness but do indicate the suffering involved.

On the whole, idioms and symptoms identified by depressed and nondepressed women and health workers were similar, but some differences should be noted. The depressed women specifically identified idioms of thinking too much, being unhappy/sad, the brain being tired, being scared, and having pain, while only the health workers mentioned (once for each example): fatigue/burnout, mental disturbance, and being crazy/possessed by witchcraft. These differences may demonstrate the distinction between the presentation and appearance of depression to the health workers, combined with a possible lack of understanding of the illness, and the actual ‘feeling’ and experience of it among the depressed women. This underscores the importance of understanding the idioms experienced by the depressed women in order to include them in interventions and inform health workers of these experiences. In the case of this research, the idioms have been included in the development of the counselling intervention manual for the RCT through various means such as: the use of the words identified by the women to describe depression; the use of experiences described by the women as vignettes for examples of problem solving; and the inclusion of a response to the needs identified by the women using theoretical approaches such as ‘problem solving’ and cognitive restructuring or ‘healthy thinking’ (Rahman, 2007). The idioms were also included in a local adaptation and validation of the primary outcome measure for the RCT, the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Hamilton, 1960).

Symptoms of depression

The analysis identified 14 categories of symptoms and descriptions of depression from the participants’ interviews. These are summarised in Table 1. In order to provide a global comparison, Table 1 also displays all of the key DSM-5 and ICD-10 symptoms required for classification of an episode of major depression. All nine DSM-5 requirements (labelled 1–9) and all 10 ICD-10 requirements (labelled 1–3 and a–g) were mentioned by the women, through differing descriptions.

Table 1.

Symptoms of depression listed by frequency of mention, compared to DSM-5 and ICD-10 symptoms

| Symptoms of depression described | Depressed women | Health workers | Nondepressed Women | Total | DSM-5 symptom* | ICD-10 symptom* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Withdrawal & not wanting to talk | 9 | 7 | 5 | 21 | (2) Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities. (6) Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day. |

(2) Loss of interest and enjoyment. (3) Reduced energy, increased fatiguability, and diminished activity. |

| Crying or sadness | 7 | 3 | 3 | 13 | (1) Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day (e.g., feels sad, empty, hopeless). | (1) Depressed mood. (2) Loss of interest and enjoyment. |

| Poor concentration | 6 | 3 | 4 | 13 | (8) Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day. (5) Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day. |

(a) Reduced concentration and attention. |

| Thinking too much | 6 | 1 | 2 | 9 | (7) Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick). [The sense of worthlessness or guilt associated with a major depressive episode may include unrealistic negative evaluations of one’s worth or guilty preoccupations or ruminations over minor past failings.] | |

| Fear & anxiety** | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Stress** | 4 | 3 | 4 | 11 | ||

| Sleep problems | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | (4) Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day. | (f) Disturbed sleep. |

| Headaches & body pain** | 4 | 0 | 2 | 6 | ||

| Don’t care | 3 | 4 | 0 | 7 | (2) Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day. | (2) Loss of interest and enjoyment. |

| Suicidal thoughts | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | (9) Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide. | (e) Ideas or acts of self-harm or suicide. |

| Loss of appetite | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | (3) Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain. | (g) Diminished appetite. |

| Anger** | 2 | 6 | 2 | 10 | ||

| Hopelessness | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | (1) Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day (e.g., feels sad, empty, hopeless). (7) Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick). |

(1) Depressed mood. (c) Ideas of guilt and unworthiness. (d) Bleak and pessimistic views of the future. (b) Reduced self-esteem and self-confidence. |

| Self-blame/guilt | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | (7) Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick). | (c) Ideas of guilt and unworthiness. |

Number/letter on the DSM-5 or ICD-10 scales in parentheses.

Symptoms not listed as key identifiers on the DSM-5 or ICD-10 scales. (However, they are included in the DSM-5 “Associated Features Supporting Diagnosis”: “Individuals frequently present with tearfulness, irritability, brooding, obsessive rumination, anxiety, phobias, excessive worry over physical health, and complaints of pain [e.g., headaches; joint, abdominal, or other pains]. … And MDE with anxious distress: Anxious distress is defined as the presence of at least two of the following symptoms during the majority of days of a major depressive episode or persistent depressive disorder [dysthymia]: 1. Feeling keyed up or tense. 2. Feeling unusually restless. 3. Difficulty concentrating because of worry. 4. Fear that something awful may happen” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, Section II, p. 27).

One consideration relating to this descriptive study is that the depressed women were diagnosed using an international diagnostic system, meaning that the symptoms they described had already been identified by the scale. However, the top four symptoms the non-depressed women used to describe depression also align with the principle requirements for the ICD10 and DSM-5 scales to diagnose depression. All other symptoms mentioned by the depressed women were also mentioned by nondepressed women and health workers, and one additional symptom, self blame or guilt, was only mentioned by nondepressed women. This demonstrates, with respect to this particular sample, that both women diagnosed and those not diagnosed using the scales identified symptoms that align with the international scales for depression.

Symptoms were retrieved from quotations such as the following, which typify experiences of depressed women like this mother, and demonstrate the complex nature and symptomology of depression:

They are angry, and when they talk about their problems they cry. Some lose weight when they are stressed. Some gain weight; you will find that they are not happy but they still gain weight. Some lose appetite. When they are with people they are always thinking. (M 60)

The most common symptom identified by the women was withdrawal from social and familial activities, including looking after babies and children. Health workers similarly spoke of depressed women not wanting to talk.

One midwife described her experience of the withdrawal of a depressed woman as follows:

After delivery, the patient wasn’t talking to anybody … just quiet and staring, as if she is just looking at you—not turning the eyes. Just open her eyes like this. So that is when someone is depressed. (Midwife [MW] 3)

Likewise, women illustrated symptoms of withdrawal in the following examples:

I like being alone … I don’t want to interact with other people. I have this thing, like always wanting to be alone [and] not being happy … You feel alone you don’t care about anything, anything because you are not at it, there’s nothing you can do … I would say it changes you how you see yourself like a nobody in front of other people. You don’t care about much. You keep thinking about this thing … If there is something that is being done, I am not in a mood to do that thing and be places with children or people. (PW 4)

I just see when it’s dark … I don’t even go out; I stay at home all day in bed. When people call me I don’t feel like giving them attention. When they knock I don’t answer … I tell my children to lock me inside. (PW 6)

I can say for example it’s someone who is always sitting alone, like someone who doesn’t like to sit with people … But the things she is doing it’s … it’s like she is a child that grew up without parents. (Nondepressed woman [ND] 4)

These quotations demonstrate that the women are aware that their behaviour is different when they have these feelings; it is not healthy or ‘normal’ to withdraw, ignore children’s needs, or feel worthless or hopeless in this community. Withdrawal as a result of their feelings has a major impact on their immediate day-to-day interactions. This extends to caring for children’s healthy development, as well as job-seeking behaviour, which has implications for them and their children’s educational, social, and economic development.

Crying or sadness was the other most common symptom mentioned by the participants. This was identified through statements such as: “I feel sad and down, I am not who I used to be” (M 57), “I am thinking and crying” (PW 15), and “I was sad, all the time crying” (PW 8). A nondepressed mother said that her friend who had depression “was always crying, and I would say ‘friend, don’t cry … I understand that your heart is hurting … It is hurting a lot by small things that are not supposed to make you cry’” (ND 3). These examples too demonstrate the identifiable abnormal patterns of behaviour such as being affected by small things and not being who you used to be.

Rochat and colleagues found in their study of women in rural KwaZulu-Natal that feelings of “sadness” were also the most frequently reported symptoms when describing depression (Rochat et al., 2011). These women also presented with disturbance of mood, loss of interest, suicidal ideation, and concentration difficulties (Rochat et al., 2011), as in the current study.

The word stress, as a symptom, was examined carefully for its meaning in the different transcripts. It appears that this is used as a word to denote worry, generally about concrete life stressors that the women are facing, but it also represents an affective state, indicating anxiety or discomfort. Thus stress is simultaneously a reflection of the hardships and adversities in the women’s lives and a symptom of depression.

The symptom thinking too much was usually mentioned concurrently with stress by participants. These two phrases were also the most frequent idioms used by the women for depression and were identified as causes, thus forming the core rhetoric of the illness. Thinking too much/excessive rumination about the problem causing depression naturally leads to stress as a symptom of depression, which then encourages further rumination, forming a self-perpetuating cycle. This can be seen in the following examples:

I would say depression is a stress more than others or bigger, maybe thinking too much, it’s made by something you have, or problems, then you think about that thing … I could have it in the stress that I have with problems. I am sitting thinking about them. (PW 4)

Here, the stress is about specific problems in the woman’s life. However, this stress encourages thinking too much, which in turn induces more stress/depression.

Another woman said:

It’s someone who is stressed to the point that the stress is too much. Thinking too much, and when she is thinking, it’s like she is going to go mad, and lose control. For example, when she thinks, she can even scream thinking about committing suicide. (M 60)

Here thinking too much and stress are mentioned so closely together that they combine to form the same rhetoric in describing depression. They are also related to an anxiety around the problems the woman has. The two in combination become so severe that they might drive her to suicide.

Lastly, one woman explained:

I would say it’s someone who thinks and does not have anyone to talk to and ends up doing things they are not supposed to and ends up with stress and sickness because of thinking because of that thing you can’t talk about. (PW 15)

In this description, stress and sickness are the idioms used for depression, brought about by ‘thinking,’ and having no one to talk to, about the “thing you can’t talk about.” This also highlights the largely unrecognised and stigmatised nature of mental illness in this area, and the related lack of care for those with the illness.

Interestingly, the phrase thinking too much (“kufungisisa”) was also identified as both a cause and a symptom of depression by the Shona people in Zimbabwe (Abas & Broadhead, 1997; Patel et al., 1995). Similar descriptions have been documented of “were ironu” in Nigeria (Odejide, Olatawura, Sanda, & Oyenye, 1977) and “nervios” in Mexico (Salgado de Snyder, de Jesus Diaz-Perez, & Ojeda, 2000). The English description for thinking too much is ‘rumination,’ which is commonly included in assessments of depression or anxiety (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000).

One mother said that she knew she was depressed because she thinks until her “brain is tired” (M 75). This links with the other most commonly mentioned theme in the women’s narratives of depression: poor concentration or confusion. Participants described this as follows: “[Depressed women] don’t talk straight or whatever they talk about they forget it” (ND 2), “There are times I even forget—I don’t know what is happening” (PW 20), and,

[Depression is] when the brain is tired … They send you to do something but you are unable to do that thing because you are thinking and forgetful, and then after 10 to 15 minutes you realize what you were sent to do. (PW 30)

A nondepressed woman stated that she doesn’t “have the disease of forgetting” (ND 3). Here the stigma of the ‘disease’ and the ramifications of forgetfulness and poor concentration on daily life functioning and child care are clear.

Another local feature of depression was that of not caring, which links to the symptom of withdrawal from activities. Lack of motivation to take care of oneself affects the mother and her whole household, as expressed through these comments: “It’s difficult to wash, even to clean the house. It’s difficult to do anything” (M 75), and “You don’t look after yourself, you don’t care about yourself” (PW 22).

The implications of not caring and withdrawal on the baby’s health and well-being were demonstrated by a mother who had struggled to accept her baby initially, but had become more “interested in him” and loved him more by the time of the interview:

In the beginning it [being stressed] was affecting me. I had days that I was tired of him, and had a feeling of giving him up for adoption. But I did not have the courage to do it. If something comes up I can’t go, I am stuck, I don’t have money to go there. Had to stay with the baby, so having regrets about him. I didn’t care about him, getting annoyed with him. If he cried I ignore him, it still happens but I don’t want to make that a habit. I continue with what I am doing and finish it, and then I will give him my attention … I did not want him really. (M 60)

A pregnant woman also spoke of her feelings:

You feel alone [and] you don’t care about anything … I won’t have time for the baby or take care of it or support it, I am always thinking, even what I am thinking, I think because I am going to have a baby, the baby is not the first thing in my life … I don’t want to interact with other people … You don’t care about much. (PW 4)

This quotation also brings to our attention the relevance of and need for specifically designed counselling interventions that focus on the symptoms identified by the women themselves. This woman identified many problems in her statement: the need for support (“you feel alone”), her lack of preparation and desire for a baby, her state of “thinking too much,” her dissociation from others, as well as her lack of care for herself and her baby. An intervention that therefore focuses on the identified needs of this woman is very important in her particular situation.

All the symptoms the women experience have consequences for their daily functioning and attention to infant growth, nutrition, and emotional development. Withdrawal, poor concentration, stress, and ‘not caring’ all have the potential to negatively affect the care of infants, and in turn may affect emotional bonding, psychological development, and physical health of the infant, as illustrated by several studies from LMICs (Cooper et al., 2009; Patel et al., 2003; Rahman et al., 2004).

The above symptoms and experiences were compared with the international diagnostic criteria of the DSM-5 and ICD-10 scales. The comparison revealed that the principle requirements for a diagnosis of depression in both nosological systems were met by the descriptions and idioms of the women. These requirements on both scales are: depressed mood, loss of interest and enjoyment/pleasure, and reduced energy leading to increased fatiguability and diminished activity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; WHO, 2010).

The results suggest that in this township, amongst Xhosa women, experiences or symptoms of depression are similar to those listed in the DSM-5 and ICD-10 scales, but that women use different words or idioms to describe these symptoms. These findings corroborate those Patel et al., 1995, Broadhead and Abas (1998), who found similarities in the manifestation and expression of depression in Zimbabwe when compared to international criteria. Rochat and colleagues also found that Zulu women in KwaZulu-Natal used “psychological language” to describe symptoms of depression, and they concluded that the standardised diagnostic tools they used were culturally sensitive (Rochat et al., 2011).

Of the 14 symptoms identified by the participants, four are not listed in the main identifying criteria on the DSM-5 or ICD-10 scales. These were: fear and anxiety, stress, headaches and body pain, and anger. However, fear and anxiety and headaches and body pain are mentioned in the “coding procedures” and “associated features” of major depression in the DSM-5 scale (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and anger is included in other scales commonly used to diagnose depression, such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Hamilton, 1960). The above experiences or symptoms have also been frequently shown to have high levels of comorbidity with depression in other international studies (Gorman, 1996), and are associated with a range of other polymorphous expressions of distress and social dysfunction.

Perceived causes of maternal depression

Study participants attributed depression to a number of causes in their community. The most frequent of these were: lack of support, unwanted pregnancy, death of a loved one, poverty and unemployment, thinking too much, coping with a new baby, and stress. It is notable that when women described the causes of depression they were more likely to provide external or tangible explanations for depression as opposed to ‘internalised’ ones, such as biological or genetic aetiologies. The causes identified by the participants are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Perceived causes of depression

| Cause of depression | Depressed women | Health workers | Nondepressed women | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of support or partner desertion | 8 | 8 | 2 | 18 |

| Unwanted pregnancy | 6 | 6 | 2 | 14 |

| Death of a loved one | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Poverty and unemployment | 4 | 8 | 2 | 14 |

| Thinking too much | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| Coping with a new baby | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| Stress | 2 | 6 | 1 | 9 |

| Abuse or rape | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| HIV status | 1 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| Witchcraft or beliefs | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| The situation they are in | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

It is clear that there is a great need for support—both emotionally and financially—amongst pregnant women and mothers in this township, many of whom cite lack of support and/or desertion by a partner as the primary cause of their depression. One pregnant woman said that the cause of her depression was “not having someone to tell me what to do so I can get help” (PW 8). This type of explanation was not unexpected, as Fisher et al. (2012) also found difficulties in the intimate partner relationship to be closely associated with perinatal mental health in LMICs (Fisher et al., 2012).

An earlier study in the same township found similar evidence that the strongest predictors of depressed mood in pregnancy were lack of emotional support from women’s partners, relationship violence, a household income below R2,000 (approximately US$200) per month, and young age (Hartley et al., 2011). These findings also corroborate with what Petersen and colleagues found in KwaZulu-Natal, where lack of support was identified as a cause of depression amongst women with HIV (Petersen, Hancock, Bhana, Govender, & PRIME, 2013).

The pregnant women interviewed were recruited at their first antenatal appointment. Many of them had only recently discovered that they were pregnant, and there was a lot of attribution of depression to the cause unwanted or unintended pregnancy. The women’s anxieties around these unwanted pregnancies were related to being unemployed and thus having no money to care for the baby, partners discovering the pregnancy and deserting them, family members rejecting them, and the added burden for some of being HIV positive and having a child to look after. This is consistent with evidence from other resource-constrained countries (Fisher, Cabral de Mello, Izutsu, & Tran, 2011). One woman said her depression was “only caused because I am pregnant” (PW 22). Another mother described the effects of an unwanted pregnancy as an added financial stress and having an impact on caring for other children:

Sometimes I feel like not having the baby. There is nothing I can do. It’s already here. If the baby was not here, there would not be so much stress. But now the problem is this: I have to think about the baby, then my life, what am I going to do. So again I had that dumb brain to let myself get pregnant again … For example, I have my first born [but] he is not as important when I have this baby. Most of the time, I am spending my money on the baby. The [first born] in the Eastern Cape, I am not taking care of him ever. Since I gave birth I haven’t sent money at all. (M 40)

The results contrast with the finding by Hartley and colleagues that depressed mood was not associated with unplanned pregnancy (Hartley et al., 2011). This difference may be attributed to the small sample size of the current study or the presence of multiple risk factors for these women.

Pain related to the death of a loved one compounded the lack of support for women, especially in the perinatal period when this was more urgently needed than at other times. Two quotations demonstrate the effect of this loss on the women:

[My friend’s] sister died … So [she] was not working and had kids. She was helped by her sister. Her children were fed by her sister, but then her sister died. While she used to be the bread winner. She was never right afterwards. (M 75)

It was not nice and then my brother had died. Then everything was upside down. Nothing was going right … It was the first thing to disturb my life. Then my mother died last year December. (PW 8)

This cause, predominantly identified by depressed women and not by health care providers, was identified by women who were already vulnerable and feeling unable to cope with everyday stress as capably as other women might. The added pain of the loss compounded this vulnerability. This shows again why it is important to hear from the depressed women themselves about what they think are the causes of their own depression, in order to improve our understanding of depression in this area.

There are multiple examples of the effect of poverty and unemployment on mood state in the interviews. One woman said that depression is caused “because a person can need money, or need work, or even food to eat” (ND 5), and another said:

It is caused by not respecting other people and poverty. Having too much load on my shoulders … If I could get a job I’d be fine. [It is] the one thing that is discouraging me the most. I am sitting, I don’t have money. (M 60)

Another mother said her depression was caused by “unemployment; not working and always being at that house” (M 52). Thus a woman sitting alone in her shack, desperate for help and demobilised by her condition, without the stimulus of employment or the reward of receiving money from a job, becomes overwhelmed by ‘stress’; and she has all day and all night to ‘think too much’ about how she will feed, clothe, and care for herself and her baby. Patel et al. (2010) speak of this link, where poverty, unemployment, and poor social relationships are both risk factors for mental illness and outcomes of the illness. This qualitative research also demonstrates the interlinked and cyclical nature of the poverty-depression relationship, however further research is needed to more specifically test these causal pathways.

Thinking too much, an idiom for depression, was also identified as a cause of depression. Stress, another idiom in turn, was also identified as a cause of depression. This demonstrates the cyclical connection between the descriptions, symptoms, and causes of depression. The participants identified external stressors as the cause of the stress/worry/depression, which brought about the internal stress of thinking too much/depression.

Notably, it was mostly the health workers who attributed depression to stress. This may be related to the fact that they were not experiencing the stress themselves, but were rather interpreting the cause through the multitude of factors that they witnessed women having to cope with on a daily basis. The health workers said that depression “is caused by stress” (CHW 2), “when a person has too much going on” (HIV Counsellor 1), and that depression “is an illness … from too much stress. For example around pregnancy, and with regarding being a mother, and worrying about money, and miscarriages etcetera. So stress causes depression” (HIV Counsellor 2). A midwife also related stress and depression thus: “You are stressed and then you think too much and then you get depression and then you don’t see the way things are; you are confused. At that time you are not orientated” (MW 5).

As shown in this discussion, stress (and thinking too much) can be brought about by the presence of extreme stress and daily ‘life stressors’ for these women. Traumatic situations, multiple risk factors, and a lack of support for the pregnant mothers in this township greatly increase the likelihood of depression amongst these women. Causes of depression (or stress) in this respect can be explored using Aneshensel’s ‘Structural origins of mental health disparities’ (Aneshensel, 2009). These origins involve:

Differential exposure to stressors: This is identified in the interviews and literature through poor and crowded living conditions (housing and sanitation), unemployment, poor education, gender-based violence, and high HIV rates.

Differential access to psychosocial resources: This comes out strongly in the interviews through the women’s comments on lack of support from partners and families, joblessness (and therefore poor financial support), and stress relating to insecure tenure of homes.

Differential effectiveness of psychosocial resources, or moderation: This was identified by the researcher at the site, through the poor system of referral pathways for depression, including no systems for identification, no clear referral pathways, and poor follow-up of referrals. There is also minimal communication between midwives at the MOU and the psychiatric nurses at the clinic, with a very low number of psychologists in the area.

The risk factors that the women face in this community in South Africa are consistent with many of those identified in international studies, such as low income levels, poverty, partner abuse, low education levels, poor housing and living conditions, poor health care, unwanted pregnancies, and HIV positive status (Brandt, 2009; Coast, Leone, Hirose, & Jones, 2012; Dunkle et al., 2004; Lund, Breen, et al., 2010; Patel et al., 2010; Rochat et al., 2011). The current study provides further evidence to corroborate already documented associations between depression and stressful life events (Aneshensel, 2009; Patel et al., 2010).

In summary, the local descriptions and causes of depression in this township setting appear to be highly interconnected, and they draw attention to the impact of multiple risk factors and social determinants on the mental health of women in the study. The risk factors identified are correspondingly highly conducive to stress, which is the most commonly used phrase to explain depression in the study. A task-shared basic counselling intervention could provide these women with a platform for talking about and reflecting on these feelings. The understanding gained from the analysis of women’s descriptions and experiences of depression provides a clear framework for both psychotherapeutic techniques and terminology to be included in such an intervention to meet local needs.

Limitations of the study

The depressed women who were interviewed were diagnosed using the MINI 6.0 and the EPDS, and thus were likely to have the symptoms of depression identified by the scales. However, we attempted to control for this bias by interviewing women who were not diagnosed as depressed on the same scales, as well as by getting perspectives from health care providers in the area. In addition, the terminology used in the descriptions of symptoms was not the same as that used in the assessment tools, suggesting that the women were describing their own thoughts and feelings and not just repeating the terms in the EPDS or MINI.

The analysis focused specifically on discovering themes related to symptoms and causes of depression, and a distinction was not made between antenatal and postnatal women’s descriptions, or between unintended and unwanted pregnancies. Also, because our focus was on depression, other “persecutory” symptoms that the women may have experienced, may not have been reported, for example, paranoia, phobia, panic states, and anger.

Conclusion

Through examining local idioms, descriptions and perceived causes of perinatal depression in an urban township in Cape Town, this study has found that descriptions are particular to the local setting, but that symptoms are similar to those identified by international diagnostic systems. Comparison with the ICD-10 and DSM-5 criteria shows that these diagnostic systems are relevant for identification of depression in this context, provided that they are translated correctly and interviewers are thoroughly trained.

There is thus value in both local and global perspectives on depression. International diagnostic systems may not capture all the specific aspects of women’s experience of distress, but they are useful (albeit crude) markers of needs for care and support. At the same time it is vital that psychosocial interventions draw on the local idioms of distress and experiences of women, in both their design and delivery. The sharing of these experiences is important for drawing attention to what is local and what is global in the mental health of mothers.

Additionally, most of the symptoms the women experienced were attributed to external ‘life stressors’ or risk factors that they faced in their everyday lives, the most notable of these being poverty, unwanted pregnancies, death of loved ones, and lack of social and economic support. The ‘stressors’ identified by these women corroborate reports from studies in other LMICs, which validates the concept of a ‘vicious cycle’ between the effect of poor socioeconomic conditions and depression (Patel & Kleinman, 2003).

The study also highlights the effect of the larger social system that the participants are involved in. The risk factors they face, most of them far out of their control, are all too often a consequence of decades of discriminatory politics and policies that favour the wealthy in South Africa. This underlines the importance of the integration of mental health research into policy development and local development initiatives.

Also notable in this study is the role of pregnancy in women’s mental health. This is a period of vulnerability to depression and stress, and all participants identified or agreed with the need for counselling to help them during this time. Assistance at this vulnerable time could have positive impacts on both mothers and infant development (Rahman et al., 2013). Local counselling interventions specifically designed for the lived experiences of women in these vulnerable situations are sorely required. The findings of this study have helped to inform the intervention arm of the RCT, through the inclusion of these idioms, narratives, and understandings in the counselling intervention manual, and represent a contribution to the local adaptation and validation of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. This in turn will be fed back to the local primary health care facilities, nongovernmental organisations and Department of Health, as part of the dissemination of findings from the RCT.

Finally, the study contributes to an evidence base at a local level, through exploring idioms and descriptions of depression. This provides information for health providers and policy makers to create context-specific and relevant assessments and interventions for maternal depression in this area. It also informs practitioners from different cultural backgrounds to be sensitive to the meanings of the particular idioms and symptoms in this setting. Understanding the social aetiology of depression subsequently encourages opportunities for interventions at a population level (Lund et al., 2011). It is also hoped that this will contribute to further efforts in the field, such as similar qualitative exploratory research in other cultural settings, the development of international instruments and nosological systems informed by local cultural idioms and symptoms, and the design and evaluation of appropriate psychosocial interventions for maternal depression.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants for sharing their time and experiences, and the field workers for their dedication to the study and empathy with the participants.

Funding

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was conducted as part of the Africa Focus on Intervention Research for Mental Health (AFFIRM). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number U19MH095699. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This work is also based on research supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (UID 85402). The grant holder acknowledges that opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in any publication generated by the NRF supported research are those of the authors, and that the NRF accepts no liability whatsoever in this regard.

Biographies

Thandi Davies, BA Hons (Psych), MPhil (Sociology), is a research officer in the South African site of the Africa Focus on Intervention Research for Mental health (AFFIRM) U19 NIMH Collaborative Hub. This is based at the Alan J. Flisher Centre for Public Mental Health, in the Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, University of Cape Town. She is currently writing her PhD using data collected in the AFFIRM-SA project, examining localised definitions, diagnoses, risk and resilience factors surrounding perinatal mental health in Khayelitsha. Broadly, her research interests lie in the links between poverty and other risk factors and perinatal mental health in low- and middle-income countries.

Memory Nyatsanza, MSocSci (Clinical Social Work), is a clinical social worker working as a mental health counsellor on the Africa Focus on Intervention Research in Mental Health (AFFIRM) project, which is a randomised controlled trial examining the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of task sharing for maternal depression in Khayelitsha. Memory trains and supervises community health workers who counsel depressed pregnant women. Memory is currently doing her PhD at the University of Cape Town (UCT), the title of which is: “Filling the Gap: Development and Qualitative Process Evaluation of a Task-Sharing Psycho-Social Counselling Intervention for Perinatal Depression in Khayelitsha.”

Marguerite Schneider, PhD, is the project manager for the Africa Focus on Intervention Research for Mental Health at the Alan J. Flisher Centre for Public Mental Health, University of Cape Town. Dr Schneider researches task-sharing interventions for common mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries and developing appropriate population measures of disability and mental disorders. Her published works focus on mental health services research, conceptual and methodological issues in measurement of disability and mental health disorders, and disability integration into social protection programmes.

Crick Lund, BA (Hons), MA, MSocSci (Clinical Psychology), PhD, is Professor and Director of the Alan J. Flisher Centre for Public Mental Health, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, University of Cape Town. He is currently CEO of the Programme for Improving Mental Health Care (PRIME), a Department for International Development (DFID) funded research consortium focusing on the integration of mental health into primary care in low resource settings in Ethiopia, India, Nepal, South Africa, and Uganda; and Principal Investigator of the Africa Focus on Intervention Research for Mental Health (AFFIRM) U19 NIMH Collaborative Hub. His research interests lie in mental health policy, service planning, and the relationship between poverty and mental health in low- and middle-income countries.

References

- Abas M, Broadhead J. Depression and anxiety among women in an urban setting in Zimbabwe. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:59–71. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS. Toward explaining mental health disparities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50(377):377–394. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bemme D, D’Souza N. Global mental health and its discontents (Report from the Advanced Study Institute [ASI] and Conference, hosted by McGill Division of Social & Transcultural Psychiatry) 2012 Retrieved from http://somatosphere.net/2012/07/global-mental-health-and-its-discontents.html.

- Berger-Greenstein J, Cuevas C, Brady S, Trezza G, Richardson M, Keane T. Major depression in patients with HIV/AIDS and substance abuse. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21(12):942–945. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R. Putting mental health on the agenda for HIV+ women: A review of evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Women and Health. 2009;49(2–3):215–228. doi: 10.1080/03630240902915044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead J, Abas M. Life events, difficulties and depression among women in an urban setting in Zimbabwe. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:29–38. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Burgess R. The role of communities in advancing the goals of the Movement for Global Mental Health. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2012;49(3–4):379–395. doi: 10.1177/1363461512454643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coast E, Leone T, Hirose A, Jones E. Poverty and postnatal depression: A systematic mapping of the evidence from low and lower middle income countries. Health & Place. 2012;18(5):1188–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P, Insel T, Chockalingam A, Daar A, Maddox Y. Grand challenges in global mental health: Integration in research, policy, and practice. PLoS Medicine. 2013;10(4):1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper P, Tomlinson M, Swartz L, Landman M, Molteno C, Stein A, Murray L. Improving quality of mother–infant relationship and infant attachment in socioeconomically deprived community in South Africa: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;338:b974. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper P, Tomlinson M, Swartz L, Woolgar M, Murray L, Molteno C. Post-partum depression and the mother–infant relationship in a South African peri-urban settlement. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;175(6):554–558. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.6.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin G, Swartz L, Tomlinson M, Cooper PJ, Molteno C. The factor structure of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in a South African periurban settlement. South African Journal of Psychology. 2004;34(1):113–121. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong JT, Reis R. Kiyang-yang, a West-African postwar idiom of distress. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2010;34(2):301–321. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9178-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjarlais R, Eisenberg L, Good B, Kleinman A, editors. World mental health: Problems and priorities in low-income countries. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle K, Jewkes R, Brown H, Gray G, McIntryre J, Harlow S. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363(9419):1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M. Prenatal depression effects on the fetus and newborn: A review. Infant Behavior Development. 2006;29(3):445–455. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JR, Cabral de Mello M, Izutsu T, Tran T. The Ha Noi Expert Statement: Recognition of maternal mental health in resource-constrained settings is essential for achieving the Millennium Development Goals. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2011;5(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, Holmes W. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2012;90(2):139–149. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.091850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flisher A, Lund C, Funk M, Banda M, Bhana A, Doku V, Green A. Mental health policy development and implementation in four African countries. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12(3):505–516. doi: 10.1177/1359105307076237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman JM. Comorbid depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 1996;4(4):160–168. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1996)4:4<160::AID-DA2>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote N, Swartz H, Geibel S, Zuckoff A, Houck P, Frank E. A randomized controlled trial of culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(3):313–321. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley M, Tomlinson M, Greco E, Comulada WS, Stewart J, Roux I, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Depressed mood in pregnancy: Prevalence and correlates in two Cape Town peri-urban settlements. Reproductive Health. 2011;8(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollan D. Self systems, cultural idioms of distress, and the psycho-bodily consequences of childhood suffering. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2004;41(1):62–79. doi: 10.1177/1363461504041354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagee A, Martin L. Symptoms of depression and anxiety among a sample of South African patients living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2010;22(2):159–165. doi: 10.1080/09540120903111445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Pedersen D. Toward a new architecture for global mental health. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2014;51:759–776. doi: 10.1177/1363461514557202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey A, Luff D. Trent focus for research and development in primary health care: An introduction to qualitative data analysis. 2001 Retrieved from http://research.familymed.ubc.ca/files/2012/03/Trent_Universtiy_Qualitative_Analysis7800.pdf.

- Lund C, Breen A, Flisher AJ, Kakuma R, Corrigall J, Joska JA, Patel V. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(3):517–528. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, De Silva M, Plagerson S, Cooper S, Chisholm D, Das J, Patel V. Poverty and mental disorders: Breaking the cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1502–1514. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60754-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Kleintjes S, Kakuma R, Flisher A. Public sector mental health systems in South Africa: Inter-provincial comparisons and policy implications. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2010;45(3):393–404. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Schneider M, Davies T, Nyatsanza M, Honikman S, Bhana A, Myer L. Task sharing of a psychological intervention for maternal depression in Khayelitsha, South Africa: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15(457):457–468. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Stansfeld S, DeSilva M. Social determinants of mental health. In: Patel V, Minas H, Cohen A, Prince M, editors. Global mental health: Principles and practice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 116–136. [Google Scholar]

- Muhwezi W, Agren H, Neema S, Maganda K, Musisi S. Life events associated with major depression in Ugandan primary healthcare (PHC) patients: Issues of cultural specificity. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2008;54(2):144–163. doi: 10.1177/0020764007083878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichter M. Idioms of distress revisited. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2010;34(2):401–416. doi: 10.1007/s11013-010-9179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychologybnormal Psychology. 2000;109(3):504–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odejide A, Olatawura M, Sanda A, Oyenye A. Traditional healers and mental illness in the city of Ibadan. Journal of Black Studies. 1977;9(2):195–205. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara M, Swain A. Rates and risk of postpartum depression: A meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry. 1996;8:37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Araya R, Lima M, Ludermir A, Todd C. Women, poverty and common mental disorders in four restructuring societies. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;49:1461–1471. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Collins P, Copeland J, Kakuma R, Katontoka S, Lamichhane J, Skeen S. The movement for global mental health. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;198(2):88–90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, DeSouza N, Rodrigues M. Postnatal depression and infant growth and development in low income countries: A cohort study from Goa, India. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2003;88(1):34–37. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Inas H, Cohen A, Prince M. Global mental health: Principles and practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Kleinman A. Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2003;81(8):609–615. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Lund C, Hatherill S, Plagerson S, Corrigall J, Funk M, Flisher A. Mental disorders: Equity and social determinants. In: Blas E, Kurup A, editors. Equity, social determinants and public health programmes. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010. pp. 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Simunyu E, Gwanzura F. Kufungisisa (thinking too much): A Shona idiom for non-psychotic mental illness. Central African Journal of Medicine. 1995;41(7):209–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L, Menaghan E, Lieberman M, Mullan J. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen I, Hancock JH, Bhana A, Govender K, members of the Programme for Improving Mental Health Care (PRIME) Closing the treatment gap for depression co-morbid with HIV in South Africa: Voices of afflicted women. Health. 2013;05(03):557–566. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo 8 [Computer software] Doncaster, Australia: Author; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A. Challenges and opportunities in developing a psychological intervention for perinatal depression in rural Pakistan – A multi-method study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2007;10(5):211–219. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0193-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Fisher J, Bower P, Luchters S, Tran T, Yasamy M, Waheed W. Interventions for common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2013;91(8):593–601. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.109819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Harrington R, Bunn J. Can maternal depression increase infant risk of illness and growth impairment in developing countries? Child: Care, Health and Development. 2002;28(1):51–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Bunn J, Lovel H, Harrington R. Impact of maternal depression on infant nutritional status and illness: A cohort study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):946–952. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, editors. Analysing qualitative data. London, UK: Routledge; 1994. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Rochat T, Richter L, Doll H, Buthelezi N, Tomkins A, Stein A. Depression among pregnant rural South African women undergoing HIV testing. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295(12):1376–1378. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat T, Tomlinson M, Bärnighausen T, Newell M, Stein A, Jean T. The prevalence and clinical presentation of antenatal depression in rural South Africa. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;135(1–3):362–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat TJ, Tomlinson M, Newell ML, Stein A. Detection of antenatal depression in rural HIV-affected populations with short and ultrashort versions of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2013;16(5):401–410. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0353-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado de Snyder V, de Jesus Diaz-Perez M, Ojeda V. The prevalence of nervios and associated symptomatology among inhabitants of Mexican rural communities. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2000;24:453–470. doi: 10.1023/a:1005655331794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H. Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in Africa: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;123(1–3):17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):878–889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan K, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Dunbar G. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(20):22–33. S34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shotter J. Conversational realities: Constructing life through language. London, UK: SAGE; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics SA. City of Cape Town – 2011 census – Cape Town. Strategic Development Information and GIS Department (SDI&GIS); 2011. Retrieved from https://www.capetown.gov.za/en/stats/Documents/2011Census/2011_Census_Cape_Town_Profile.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DE. Depression during pregnancy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:1605–1611. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1102730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield D. Afterword: Against “global mental health”. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2012;49(3–4):519–30. doi: 10.1177/1363461512454701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surkan P, Kennedy C, Hurley K, Black M. Maternal depression and early childhood growth in developing countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2011;11 doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.088187. Retrieved from http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?pidS0042-96862011000800013&scriptsci_arttext. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz L. ¼An unruly coming of age: The benefits ¼ of discomfort for global mental health. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2012;49(3–4):531–538. doi: 10.1177/1363461512454810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symon G. Everyday rhetoric: Argument and persuasion in everyday life. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. 2000;9(4):477–488. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Tomlinson M. Mental health spillovers and the Millennium Development Goals: The case of perinatal depression in Khayelitsha, South Africa. Journal of Global Health. 2012;2(1):010302. doi: 10.7189/jogh.02.010302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachs T, Black M, Engle P. Maternal depression: A global threat to children’s health, development, and behavior and to human rights. Child Development Perspectives. 2009;3(1):51–59. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. MhGAP Mental Health Gap Action Programme: Scaling up care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International classification of diseases (ICD) Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global burden of mental disorders and the need for a comprehensive, coordinated response from health and social sectors at the country level. Notes from a plenary meeting at the Sixty-Fifth World Health Assembly. 2012 May; Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB130/B130_R8-en.pdf.