Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are essential small RNA molecules that regulate the expression of target mRNAs in plants and animals. Here, we aimed to identify miRNAs and their putative targets in Hibiscus syriacus, the national flower of South Korea. We employed high-throughput sequencing of small RNAs obtained from four different tissues (i.e., leaf, root, flower, and ovary) and identified 33 conserved and 30 novel miRNA families, many of which showed differential tissue-specific expressions. In addition, we computationally predicted novel targets of miRNAs and validated some of them using 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends analysis. One of the validated novel targets of miR477 was a terpene synthase, the primary gene involved in the formation of disease-resistant terpene metabolites such as sterols and phytoalexins. In addition, a predicted target of conserved miRNAs, miR396, is SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE, which is involved in flower initiation and is duplicated in H. syriacus. Collectively, this study provides the first reliable draft of the H. syriacus miRNA transcriptome that should constitute a basis for understanding the biological roles of miRNAs in H. syriacus.

Keywords: development, flowering initiation, Hibiscus syriacus, microRNA, small RNA, terpene synthesis

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression by posttranscriptional silencing mechanisms in plants and animals and control development, disease resistance, and stress responses in plants (Casadevall et al., 2013; Li et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2006; Zhu and Helliwell, 2011). Plant miRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II as primary miRNAs that are processed to precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) via Dicer-like 1 (DCL1) in the nucleus. Pre-miRNAs are exported to the cytoplasm where DCL1 cleaves the pre-miRNAs near its stem-loop, giving rise to the characteristic 21–23 nucleotide (nt) long double-strand RNAs with two nucleotides 3′ overhangs. These miRNA duplexes are incorporated into the Argonaute (AGO) protein to form the effector complex, which is referred to as the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The two strands of the miRNA duplex are then separated in AGO, with one strand removed and the other one retained in RISC for target recognition and silencing. In plants, most miRNAs exhibit near-perfect complementarity to their targets, often resulting in mRNA cleavage (Rogers and Chen, 2013). Because of the small size, low abundance, and tissue- or developmental stage-specific expression patterns of miRNAs, coupled with stress-induced dynamic changes in their expression, experimentally validating miRNAs has been challenging. Since the advent of next-generation sequencing, high-throughput sequencing data have become available, and computational approaches of processing large-scale data have led to the discovery of a large number of miRNA sequences (Hwang et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2012).

Hibiscus syriacus, also known as the rose of Sharon, is the national flower of South Korea and belongs to the member of the Malvaceae family such as cotton and cacao. H. syriacus has significance in gardening, medicine, and cultural perspective in Korea. Meanwhile, Mugunghwa, which means “flowering forever” and is its Korean name, is derived from its unique characteristic that it blooms and falls away in several months. A recent study provided the draft genome of H. syriacus and suggested that the flowering-related phenotype might be associated with polyploidization (Kim et al., 2017). Despite its interesting features, the miRNA transcriptome of H. syriacus remains unknown. Therefore, identifying miRNAs and their targets in H. syriacus could help to understand their biological functions.

Taking advantage of the recent genome sequencing in H. syriacus (Kim et al., 2017), we employed high-throughput sequencing to identify conserved and novel miRNAs in H. syriacus via a computational approach. We successfully identified 93 conserved and 36 novel miRNAs from four different tissues. We also predicted their corresponding target genes and further validated several targets using the 5′ RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RLM-RACE) analysis. One of the predicted targets of conserved miRNAs, miR396, is SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE (SVP), which is involved in flower initiation and is duplicated in H. syriacus (Kim et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2015). In addition, we showed that miR477 directs the cleavage of terpene synthase, which has functions in isoprenoid synthesis. Altogether, our study lays the foundation for understanding the functions of miRNAs in H. syriacus and provides the beneficial data regarding molecular breeding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of small RNA library

Total RNAs were extracted from H. syriacus tissue samples (leaf, root, flower, and ovary) using TRI Reagent solution (MRC), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Both the flower and ovary were pretreated with CTAB buffer [2% CTAB, 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone K 30, 100 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 25 mM EDTA, 2 M NaCl, and 2% β-mercaptoethanol] followed by TRI Reagent extraction, as previously described (Peng et al., 2014). A small RNA sequencing library was constructed using the Small RNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. As previously described (Hwang et al., 2013), 10 μg of total RNAs was resolved using 15% urea-PAGE, and size fractions of small RNAs between 18 and 30 nt were prepared. The prepared small RNAs were ligated to the 3′ and 5′ adapter, and cDNA was synthesized using RT-PCR. cDNAs were amplified using PCR and submitted for Illumina/Solexa sequencing. The GEO accession number for our series is GSE99329.

Identification of miRNA and target prediction

The pipeline of miRNA identification was written in Python language, and the details of the pipeline are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. Poor-quality small RNA reads and adapter sequences were eliminated using the FASTX toolkit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/index.html), and the reads whose length was between 18 and 26 nt were selected for further analysis. High-quality small RNAs (reads of ≥ 50) were mapped to the reference genome of H. syriacus (Kim et al., 2017) using Bowtie-1.1.2 (Langmead et al., 2009), and the perfectly mapped sequences were selected (≤ 42 times). The filtered reads were analyzed to identify the putative miRNAs in the modified algorithm (Hwang et al., 2013; Meyers et al., 2008). After identification, the miRNA candidates were classified to either the conserved miRNAs or novel miRNAs through a BLASTN search (Camacho et al., 2009) with miRBase release 21.0 (http://www.mirbase.org/) (Kozomara and Griffiths-Jones, 2014) and filtered with several criteria (Supplementary Fig. S1) (Hwang et al., 2013; Trotta, 2014). The reads of miRNAs from each library were normalized to read per 10 million (RP10M). The potential target genes of miRNAs were predicted using psRNAtarget with a penalty score of ≤ 5 (Dai and Zhao, 2011).

miRNA target validation assays

For miRNA target validation, gene-specific 5′ RLM-RACE was performed as previously described (Hwang et al., 2013). In brief, 5 μg of pooled total RNA obtained from leaf, root, flower, and ovary tissues were ligated to 5′ the GeneRacer RNA adapter (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription producing cDNAs were synthesized with both Oligo (dT) primers and random hexamers. Primary PCR was performed with the GeneRacer 5′ primer and 3′ reverse primers containing each respective gene-specific sequence (Supplementary Table S1). Before cloning into a TA cloning vector (RBC) for sequencing, nested PCR was performed using the GeneRacer 5′ nested primer and each respective gene-specific nested reverse primer (Supplementary Table S1).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Small RNA analysis of H. syriacus

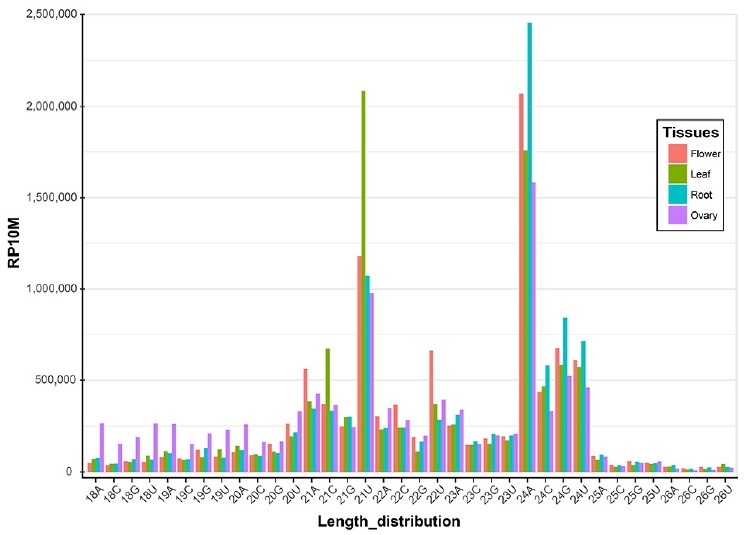

Small RNA libraries from leaf, root, flower and ovary were constructed and processed using a computation pipeline, as described in Supplementary Fig. S1. From this, 20–27 million raw reads were obtained from each library (Table 1). After filtering low-quality reads and those with no adapter sequences, 16–25 million reads remained, representing 10–14 million unique sequences (Table 1). These small RNA reads were mapped to the H. syriacus genome for small RNA identification. Small RNA sequences of 21 and 24 nt in length were dominant in all four libraries (Fig. 1), which is mostly consistent with those previously reported on other plant species (Hwang et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2012; Pantaleo et al., 2010). For the 21-nt reads, the 5′-end U was dominant in all four libraries, followed by A. In contrast, the 5′-end A was the major form in 24-nt reads, followed by U, representing the canonical small RNA distribution (Fig. 1). For example, Arabidopsis thaliana miRNAs are processed by DCL1 and loaded into AGO1; a strong bias toward a 5′-terminal U is observed. The 24-nt small RNAs are processed by DCL3 and preferred by AGO4 and have sequences with 5′-terminal A (Voinnet, 2009).

Table 1.

Overview of small RNA data processing

| Flower | Leaf | Root | Ovary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total raw reads | 25,135,674 | 27,905,172 | 26,480,747 | 20,293,996 |

| Filtering low-quality reads | 23,117,590 | 25,759,516 | 24,378,687 | 18,538,908 |

| Clipping adapter sequence | 22,683,220 | 25,047,715 | 23,831,785 | 16,615,864 |

| Total unique reads | 12,429,111 | 14,031,342 | 15,607,150 | 10,141,963 |

| Genome mapped unique reads (≤42 times) | 4,840,092 | 5,465,149 | 5,927,141 | 3,762,707 |

Fig. 1.

The length distribution and the first nucleotide of the 5′ end of small RNAs are shown for four different libraries prepared from flower, leaf, root and ovary tissues in H. syriacus.

The reads are normalized to RP10M (y-axis). Two major peaks of 21U and 24A are attributed to miRNAs and siRNAs, respectively.

Identification of miRNAs in H. syriacus

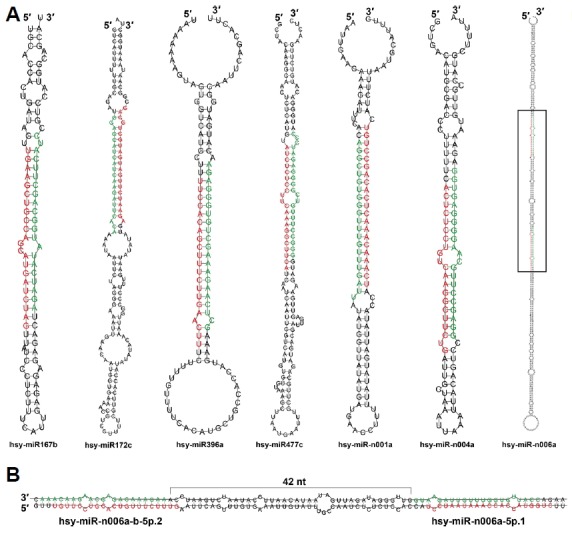

Aligned small RNA sequences were analyzed to identify candidate miRNAs on the basis of the strict criteria for annotation of plant miRNA (Meyers et al., 2008). To classify conserved and novel miRNAs in H. syriacus, the candidates were BLASTN searched against the reference miRNAs in miRBase (release 21.0), allowing two or less mismatches within mature miRNA sequences. Those sequences that were not matched were manually checked with precursor similarity to assess whether they were truly novel miRNAs or belonged to conserved families. Representative and total miRNAs are listed in Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2, respectively. Overall, 93 conserved miRNAs belonging to 33 families and 36 novel miRNAs from 30 families were annotated. The representative structures of miRNA precursors are shown in Fig. 2A. Although most miRNA precursors encode a single mature miRNA, a few encodes two different mature miRNAs such as hsy-miR-n006a-b-5p.2 and hsy-miR-n006a-5p.1, both of which are located 42-nt apart (Fig. 2B). This phenomenon has been reported in several other plants, including A. thaliana, Oryza sativa, Medicago truncatula (Zhang et al., 2010), possibly because of the sequential processing of Dicer-like proteins.

Table 2.

Identified representative miRNAs and their expression patterns in H. syriacus

| ID | Sequence | Flower* | Leaf* | Root* | Ovary* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsy-miR156a-g-5p | UUGACAGAAGAUAGAGAGCAC | 3437.3 | 144491.9 | 160330.7 | 21097.3 |

| hsy-miR159a-f-3p | UUUGGAUUGAAGGGAGCUCUA | 73086.3 | 705828.0 | 128364.6 | 69978.8 |

| hsy-miR160a-i-5p | UGCCUGGCUCCCUGUAUGCCA | 2219.3 | 1696.4 | 2712.1 | 234.6 |

| hsy-miR164a-n-5p | UGGAGAAGCAGGGCACGUGCA | 3146.3 | 3404.2 | 9193.0 | 1723.5 |

| hsy-miR166a-ag-3p | UCGGACCAGGCUUCAUUCCCC | 115672.5 | 147905.1 | 165733.5 | 117964.7 |

| hsy-miR167a-e-5p | UGAAGCUGCCAGCAUGAUCUAG | 5928.4 | 65750.5 | 2522.2 | 2661.9 |

| hsy-miR171a-ad-3p | UGAUUGAGCCGUGCCAAUAUC | 66336.0 | 3424.6 | 14169.2 | 117303.9 |

| hsy-miR172a-h-3p | AGAAUCUUGAUGAUGCUGCAG | 34125.3 | 36.7 | 147.0 | 13599.2 |

| hsy-miR172i-w-3p | AGAAUCUUGAUGAUGCUGCAU | 5416.6 | 25253.7 | 249.3 | 1050.3 |

| hsy-miR319a-j-3p | UUGGACUGAAGGGAGCUCCC | 56882.1 | 3618.6 | 5617.1 | 88849.6 |

| hsy-miR390a-o-5p | AAGCUCAGGAGGGAUAGCGCC | 160828.4 | 1896.9 | 24151.0 | 7968.8 |

| hsy-miR393a-n-5p | UCCAAAGGGAUCGCAUUGAUC | 109150.5 | 5871.8 | 3223.4 | 21535.8 |

| hsy-miR394a-g-5p | UUGGCAUUCUGUCCACCUCC | 15828.2 | 3599.1 | 10783.2 | 17168.9 |

| hsy-miR396a-i-5p | UUCCACAGCUUUCUUGAACUU | 10204.6 | 84749.3 | 7706.9 | 4273.4 |

| hsy-miR477c-e-5p | AUCUCUCCUUCAAAGGCUUCA | 1785.0 | 3647.1 | 2101.5 | 276.0 |

| hsy-miR482a-3p | UCUUUCCUAGUCCUCCCAUACC | 3714.4 | 3482.5 | 1947.7 | 2950.2 |

| hsy-miR482f-h-3p | UUUUGCCUACACCGCCCAUUCC | 4381.3 | 3243.6 | 3313.9 | 4446.7 |

| hsy-miR482i-j-3p | UCUUUCCUACUCCUCCCAUUCC | 1582.2 | 2598.8 | 1507.5 | 2468.7 |

| hsy-miR535a-5p | UGACAAUGAGAGAGAGCACGC | 5995.3 | 16604.5 | 11901.2 | 5512.4 |

| hsy-miR535b-c-5p | UGACAACGAGAGAGAGCACGC | 237.9 | 14589.4 | 5733.9 | 1122.4 |

| hsy-miR827a-3p | UUAGAUGACCAUCAACAAACG | 1123.5 | 4653.9 | 228.9 | 387.9 |

| hsy-miR-n001a-b-3p | UCAAACAAACUCACAGCCUGU | 25735.4 | 92531.1 | 32381.8 | 14674.1 |

| hsy-miR-n002a-5p | UUUUCCAAGCUGCCCUUUUGCA | 1368.7 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 104.3 |

| hsy-miR-n003a-e-3p | UUUGUCACUAACUUUGUCACU | 28242.5 | 20884.3 | 9905.8 | 5604.4 |

| hsy-miR-n005a-5p | UUCAUAAGAUUGUGCUGAGUU | 15709.3 | 8239.9 | 6067.9 | 5204.2 |

| hsy-miR-n006a-5p.1 | UCCUAAUAAACCACCAUGGUC | 5046.0 | 14205.4 | 4484.5 | 7341.7 |

| hsy-miR-n006b-5p.1 | UCCUAACGAACCACCAUGGUC | 2508.1 | 14222.6 | 2948.8 | 4087.9 |

| hsy-miR-n006a-b-5p.2 | UGUUCCUGCACUGUUUCUUUG | 3983.1 | 12694.9 | 4098.9 | 2324.5 |

| hsy-miR-n007a-5p | UUAAACAACUGUAGGUGACAA | 3120.8 | 16730.1 | 5937.5 | 962.9 |

| hsy-miR-n008a-3p | UGCCUUUUCUUUUAGCUUCUG | 5132.0 | 12214.8 | 4131.0 | 1876.8 |

| hsy-miR-n010a-5p | AUGAAUCUAGUUUCUCUCUUCGU | 252.7 | 10982.2 | 3031.5 | 736.0 |

| hsy-miR-n011a-b-3p | GAAGCCUUUGAGAGGGAGUGG | 5393.2 | 823.3 | 4203.1 | 4978.8 |

| hsy-miR-n013a-5p | UCCUUCACAAAUGUCACAAUA | 1163.8 | 3044.7 | 517.1 | 463.1 |

| hsy-miR-n016a-b-5p | UCUCAUGACUUCAUCGCUUCC | 575.5 | 2312.7 | 673.9 | 835.7 |

| hsy-miR-n017a-5p | UCGUCCAUGCGCGACACGUAC | 1573.7 | 88.9 | 801.5 | 3279.8 |

| hsy-miR-n018a-5p | UUGUCUCCUUUGAAGGCCGCA | 1212.7 | 1575.8 | 984.5 | 532.1 |

| hsy-miR-n020a-5p | UUCCGGCGUCUAUAUAAGAGUC | 1827.5 | 850.2 | 18.5 | 1209.8 |

| hsy-miR-n021a-3p | UCUUCCCAACACCUCCUAUACC | 676.4 | 795.6 | 1310.8 | 723.7 |

indicates normalized reads (RP10M)

Fig. 2.

The representative hairpin structures of the conserved and novel miRNA precursors.

Mature miRNAs and star miRNAs are colored in red and green, respectively. Some examples of the hairpin structures of the conserved and novel miRNAs are shown (A). Enlarged black box region is shown in (B). Note that the precursor of hsy-miR-n006a encodes two mature miRNAs.

There are many miRNA copies in the H. syriacus genome compared with those in other plant species. For instance, miR166 is a well-conserved miRNA in various plant species (Cuperus et al., 2011). While there are seven copies in the A. thaliana genome, H. syriacus has 50 copies (Supplementary Table S3). This is much greater than that of Glycine max (21 copies), which is known to have many copy numbers of miRNAs (Nozawa et al., 2012). miR171 is another highly conserved miRNA with three copies in A. thaliana, 48 copies in H. syriacus, and 21 copies in G. max genome (Supplementary Table S3). Although the depth for different libraries and pipelines for identification are slightly different, the copy numbers of several miRNAs in H. syriacus are likely greater than those in other species. In contrast, with respect to miR156, there are eight copies in A. thaliana, 27 copies in H. syriacus, but 28 copies in G. max (Supplementary Table S3). A possible reason for this could be whole-genome duplication (WGD) events. After the last speciation, the H. syriacus genome underwent two WGD and diploidization events. Subsequently, the dosage of the individual gene family was differently regulated. Therefore, the H. syriacus species has more gene loci than other Malvaceae plants or Arabidopsis (Kim et al., 2017). Likewise, WGD and diploidization might cause miRNA copy number variations in H. syriacus. Conversely, almost all of the novel miRNAs are present in one or two copies in the genome. The novel miRNA genes might have been generated after speciation, and thus, may experience less WGD events than conserved miRNAs, possibly explaining the reason for the numbers of novel miRNAs being less than those of conserved miRNAs.

miRNA expression patterns of H. syriacus

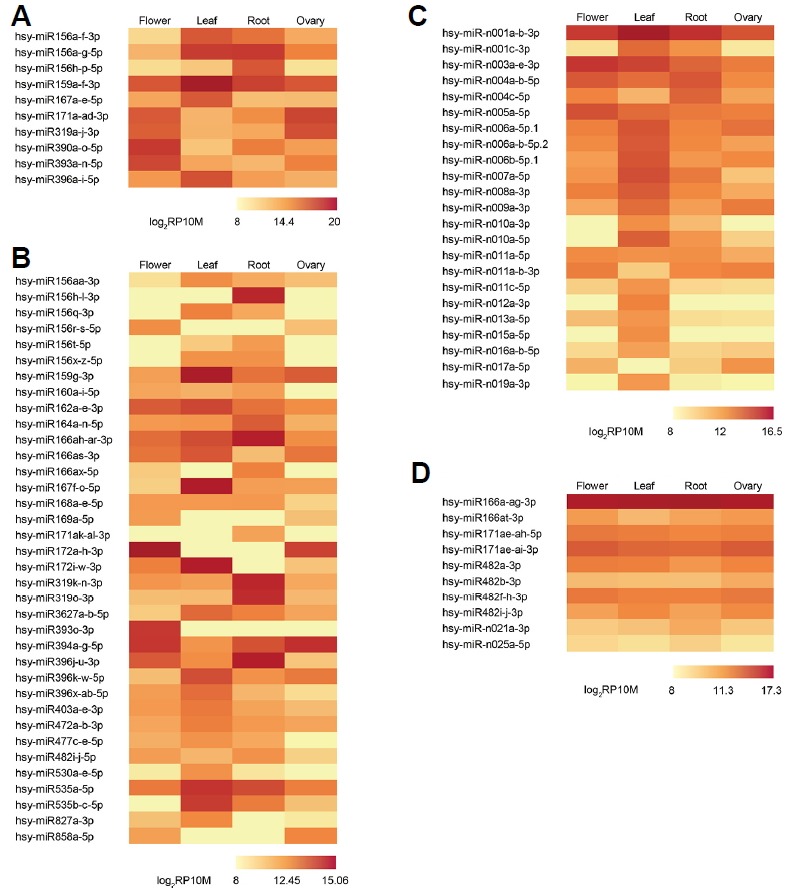

As normalized to RP10M, expression patterns of conserved and novel miRNAs from four tissues are shown in Fig. 3. First, Figs. 3A and 3B both represent conserved miRNAs with at least two-fold differences between their respective minimum and maximum expressions. Second, the top 10 most highly expressed miRNAs are shown in Fig. 3A, and the others are shown in Fig. 3B. Third, novel miRNAs are shown in Fig. 3C. Finally, some miRNAs that are consistently expressed throughout all four tissues are shown in Fig. 3D. Overall, many conserved miRNAs are expressed higher than novel miRNAs with miR156a-f-3p, miR319a-j-3p, miR390a-o-5p, miR393a-n-5p, and miR396a-i-5p being the most highly expressed (Table 2). The only highly expressed novel miRNA was miR-n001a-b-3p with 92531 reads in leaf tissues. These results indicate that conserved miRNAs are expected to play more significant roles than novel miRNAs in regulatory pathways and have a much wider range of dynamic expression for various regulations.

Fig. 3.

Expression patterns of the conserved and novel miRNAs.

The miRNAs were excluded whose maximum expression is less than 2048 RP10M. The miRNAs with fold change two or more between minimum and maximum expression (A-C). Conserved miRNAs ranked in the top 10 with the highest expression (A), the other conserved miRNAs (B), and novel miRNAs (C). Consistently expressed miRNAs throughout all tissues (D).

Many conserved miRNAs show tissue-specific expression patterns. For example, miR156a-g-5p expression was distinctively higher in the leaf and root than in the flower and ovary (Fig. 3A). Another member of miR156, miR156h-p-5p, was not highly expressed in the leaf, but it was highly expressed in the root (Fig. 3A). The differential expression of these may indicate that their biological roles are slightly different, even within the same family members. In contrast, miR172a-h-3p was exclusively expressed in the flower and ovary. Previous studies showed that miR156 is an upstream regulator of miR172 and acts by repressing miR172 through its target, SQUAMOSA PROMOTER-BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE 9 (SPL9) in A. thaliana. This in turn activates miR172 transcription (Wu et al., 2009). In the juvenile phase, miR156 represses SPL, which is necessary for leaf growth (Wu et al., 2009) and lateral root development (Yu et al., 2015). SPL9 consequently activates miR172, which promotes an adult phase transition by repressing its targets, TOE1 and TOE2 (Wu et al., 2009). The expression patterns of these miRNAs (Fig. 3A–3B) are consistent with previous studies (Wu et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2015), indicating that miR156 and miR172 may function similarly in H. syriacus.

miR396a-i-5p expression in the leaf was much higher than that in other tissues (Fig. 3A). miR396 regulates the GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR (GRF) families to control cell proliferation in the A. thaliana leaf (Rodriguez et al., 2010). In leaf tissues, miR396 expression levels steadily increase during leaf maturation, attenuating cell proliferation (Rodriguez et al., 2010). This is in line with our results that miR396 expression was the highest in the leaf, suggesting that its functional role is conserved in H. syriacus. Moreover, another study showed that when A. thaliana is exposed to UV-B radiation, miR396 is expressed to inhibit leaf growth by GRFs repressions (Casadevall et al., 2013). Because our samples were collected from the open field, miR396 might be highly expressed highly in the leaf.

Similar to miR172, miR319a-j-3p expression was much higher in the flower and ovary than in the leaf and root (Fig. 3A), whereas miR319k-n-3p expression (Fig. 3B) was higher in the root than in any other tissues. Previous studies showed that the loss-of-function miR319 mutants of A. thaliana exhibit defects in petal and stamen development, with narrower and shorter petals and impaired anther formation (Nag et al., 2009; Rubio-Somoza and Weigel, 2013). In addition, each member of the miR319 family is expressed in different tissues. In A. thaliana, miR319a is highly expressed in the petals and stamens during early flower development but not in the leaves, whereas miR319c is expressed in young leaf primordia (Nag et al., 2009). High miR319a-j 3p expression levels in the flower and ovary may indicate a conserved or similar control mechanism that also exists in the flower development of H. syriacus. Furthermore, a recent study showed that transgenic Agrostis stolonifera that overexpressed Osa-miR319a had less root biomass and better salt and drought tolerance than mock controls (Zhou et al., 2013). Another member of the miR319 family, miR319k-n-3p is highly expressed in the root, which might be associated with this phenomenon.

Some miRNAs were consistently expressed in all four tissues (Fig. 3D). For instance, miR166a-ag-3p showed quite high expression patterns in every tissue. Mutation studies demonstrated that miR166 overexpression affected several class III homeodomain-leucine zipper family genes, possibly causing defects in the shoot meristem, leaves, gynoecia, and vascular tissues of A. thaliana (Kim et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2005). In addition, miR166 controls root and nodule development in M. truncatula (Boualem et al., 2008). These results indicated that miR166 is possibly associated with the development of several tissues, which is in accordance with the fact that miR166 is expressed consistently in all tissues.

Novel miRNAs generally showed lower and less dynamic expression than those of conserved miRNAs (Figs. 3A–3C), suggesting their species-specific roles in particular circumstances. However, a few novel miRNAs exhibited dynamic expression patterns; for example, miR-n001a-b-3p and miR-n006 family genes were highly expressed in leaf, whereas miR-n003a-e-3p displayed the highest expression in flower. These results may indicate tissue-specific roles of some novel miRNA families.

miRNA target analysis of H. syriacus

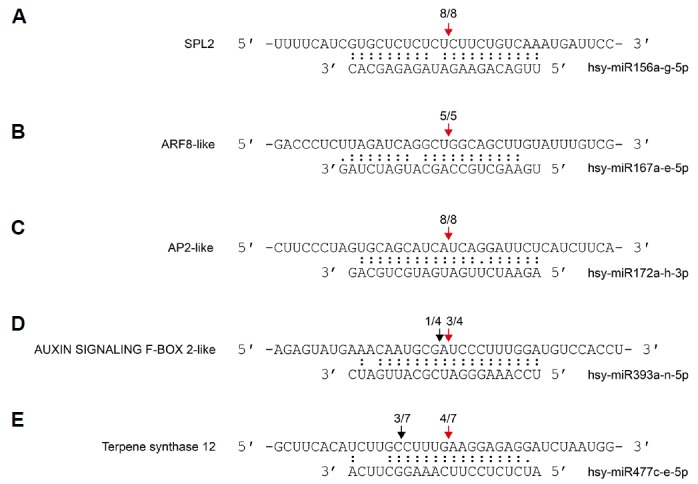

To investigate the potential regulatory roles of miRNAs in H. Syriacus, we predicted the putative target genes (Supplementary Table S4) using psRNAtarget with penalty scores of five or less (Dai and Zhao, 2011). The representative targets of 17 conserved and 28 novel miRNA families are shown (Table 3). Five targets of some conserved miRNAs were validated by 5′ RLM-RACE analysis (Fig. 4) (Park and Shin, 2014).

Table 3.

Representative target genes of miRNAs

| miRNA | Gene ID | Score* | Predicted targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| hsy-miR156a-g-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold4580G00040;1 | 1.5 | Squamosa promoter-binding-like protein (SPL2) |

| hsy-miR159a-f-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold2654G00160;1 | 2.5 | GAMYB-like |

| hsy-miR160a-i-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold340G00010;1 | 0 | Auxin response factor 18-like |

| hsy-miR164a-n-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold860G00270;1 | 1 | NAC domain-containing protein 21/22-like |

| hsy-miR166a-ag-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold2040G00100;1 | 1 | Homeobox-leucine zipper protein ATHB-15 |

| hsy-miR167a-e-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold3445G00010;1 | 3.5 | Auxin response factor 8-like |

| hsy-miR168a-e-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold5081G00010;1 | 2.5 | Argonaute 1-like |

| hsy-miR171a-ad-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold11370G00010;1 | 1.5 | scarecrow-like protein 15 |

| hsy-miR172a-h-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold4855G00090;1 | 1.5 | APETALA 2-like |

| hsy-miR319a-j-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold2654G00160;1 | 1.5 | GAMYB-like |

| hsy-miR319k-n-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold9331G00030;1 | 3 | Trancsription factor TCP2-like |

| hsy-miR390a-o-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold2389G00050;1 | 1 | DEAD-box ATP-dependent RNA helicase 21 |

| hsy-miR393a-n-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold13061G00020;1 | 1 | AUXIN SIGNALING F-BOX 2-like |

| hsy-miR394a-g-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold4580G00050;1 | 0 | F-box only protein 6-like |

| hsy-miR396a-i-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold4058G00060;1 | 3 | Growth-regulating factor 8 |

| hsy-miR396a-i-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold12526G00010;1 | 3.5 | SVP |

| hsy-miR477c-e-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold12096G00030;1 | 4.5 | Terpene synthase 12 |

| hsy-miR482f-h-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold5993G00050;1 | 2.5 | TMV resistance protein N-like |

| hsy-miR-n001a-b-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold5429G00090;1 | 2.5 | pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein |

| hsy-miR-n002a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold848G00030;1 | 0 | serine/threonine-protein kinase NAK |

| hsy-miR-n003a-e-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold8246G00050;1 | 1.5 | Dihydroxy-acid/6-phosphogluconate dehydratase |

| hsy-miR-n004a-b-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold9877G00010;1 | 2.5 | Villin headpiece |

| hsy-miR-n005a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold278G00060;1 | 3.5 | Protein kinase, ATP binding site |

| hsy-miR-n006a-5p.1 | MGA0.9.scaffold3312G00010;1 | 2.5 | receptor-like protein 12 |

| hsy-miR-n007a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold6516G00020;1 | 3.5 | pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein |

| hsy-miR-n008a-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold1030G00160;1 | 3.5 | AP2/ERF domain |

| hsy-miR-n009a-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold728G00190;1 | 3.5 | P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase |

| hsy-miR-n010a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold11364G00020;1 | 2.5 | Formin-like protein 1 |

| hsy-miR-n011a-b-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold7812G00030;1 | 3.5 | ABC transporter B family member 19-like |

| hsy-miR-n012a-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold4383G00050;1 | 1 | GHMP kinase, C-terminal domain |

| hsy-miR-n013a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold7316G00030;1 | 2.5 | disulfide-isomerase-like |

| hsy-miR-n014a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold320G00110;1 | 1.5 | hAT-like transposase, RNase-H fold |

| hsy-miR-n016a-b-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold1040G00050;1 | 2.5 | B3 DNA binding domain |

| hsy-miR-n017a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold6114G00010;1 | 1.5 | Transcription factor MYC2-like |

| hsy-miR-n018a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold3769G00020;1 | 3.5 | Agglutinin |

| hsy-miR-n019a-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold4560G00040;1 | 3.5 | Telomeric single stranded DNA binding POT1/Cdc13 |

| hsy-miR-n020a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold8817G00010;1 | 1 | GDSL-like Lipase/Acylhydrolase superfamily protein |

| hsy-miR-n021a-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold2246G00010;1 | 3.5 | CBL-interacting protein kinase 32-like |

| hsy-miR-n022a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold3098G00030;1 | 1.5 | Agglutinin |

| hsy-miR-n023a-b-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold2125G00040;1 | 0 | Zinc finger, C2H2 |

| hsy-miR-n024a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold1771G00350;1 | 3 | Zinc finger, FYVE/PHD-type |

| hsy-miR-n025a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold524G00320;1 | 3.5 | Sodium/calcium exchanger membrane region |

| hsy-miR-n026a-b-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold8747G00010;1 | 3 | Clathrin, heavy chain/VPS, 7-fold repeat |

| hsy-miR-n027a-b-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold12867G00020;1 | 2.5 | Myc-type, basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) domain |

| hsy-miR-n028a-3p | MGA0.9.scaffold3563G00070;1 | 3.5 | Putative polysaccharide biosynthesis protein |

| hsy-miR-n029a-5p | MGA0.9.scaffold2300G00100;1 | 4.5 | Six-hairpin glycosidase |

indicates expectation (penalty score) of predicted targets (Dai and Zhao, 2011)

Fig. 4.

Validation of the miRNA-directed target mRNA cleavages in H. syriacus.

Fractions refer to the number of cloned 5′ RLM-RACE products whose 5′ end terminated at the indicated position (numerator) over the total number of sequenced clones (denominator). Red arrows indicate the canonical cleavage sites, whereas black arrows indicate micro-heterogeneity of the cleavage.

Noticeable targets of conserved miRNAs include many transcription factors such as SPL, no apical meristem domain-containing proteins, auxin response factors (ARFs), GRFs, and MYBs. Moreover, there are other conserved targets, including auxin signaling F-Box (AFB) and nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NB-LRR). These results indicate that miRNAs in H. syriacus are likely to have conserved roles in the regulation of growth, development, and disease resistance. For example, SPLs are the major targets of miR156, as an intermediate of the miR156-SPL-miR172 pathway that controls the developmental timing via feedback regulations (Wu et al., 2009). The APETALA2 (AP2)-like are regulated by miR172 via translation inhibition, thereby controlling the flowering time and floral organ identity (Aukerman and Sakai, 2003). ARFs are the targets of miR160 and miR167 and regulate sexual reproduction (Wu et al., 2006) and adventitious rooting (Gutierrez et al., 2009). Other auxin-associated genes, AFBs, under the control of miR393, regulate leaf development via secondary siRNAs (Si-Ammour et al., 2011) and the root system architecture under nitrate treatment (Vidal et al., 2010) in A. thaliana. In another case, TEOSINTE BRANCHED1, CYCLOIDEA, and PCF (TCP) is mainly regulated by miR319, an important player of the morphological integrity of the plant, including shoot lateral organs (Koyama et al., 2007). In addition, miR319 and its target, TCPs, are related to flower and reproductive tissues development (Nag et al., 2009; Rubio-Somoza and Weigel, 2013). NB-LRRs, which are targeted by miR482, recognize pathogen-encoded effectors and initiate an effector-triggered immunity. The NB-LRR domain represents a general character of disease resistance proteins in plants acquired from co-evolutionary arms race between pathogens and their host plants (Park and Shin, 2015).

In this study, we first discovered a novel target of the conserved miRNA, miR477. miR477c-e-5p was predicted to regulate the terpene synthase gene, which was validated by 5′ RLM-RACE analysis (Fig. 4E). Terpene synthase is an enzyme for synthesizing terpene, which is associated with the plant innate immunity (Wang et al., 2012). Thus, we expect these results to provide a foundation for further studies regarding the control of terpene synthesis. The recent genome study of H. syriacus suggested that flowering-related genes were specifically expanded in H. syriacus (Kim et al., 2017). One of the expanded genes is SVP that controls flowering time by repressing FLOWERING LOCUS T expression (Lee et al., 2007). A recent study showed that miR396 triggers mRNA decay of SVP, when the phyllody symptoms 1 effector is treated to Catharanthus roseus, which causes a leafy or abnormal flower phenotype (Yang et al., 2015). These studies suggest the SVP represses flowering and miR396 is an upstream regulator of SVP. We found that expanded SVPs are predicted targets of miR396 in H. syriacus (Table 3), which raises an intriguing possibility that SVPs are associated with a specific flowering pattern of H. syriacus.

As described above, we proposed that WGD might affect the expansion of some miRNA families and protein-coding genes in H. syriacus (Kim et al., 2017). Therefore, we investigated whether isoforms of the expanded miRNA families regulate the same target or other target genes to deepen our comprehension of the impact of WGD on H. syriacus. In the case of miR156 family, miR156a-g-5p showed higher expression in vegetative tissues than that in reproductive tissues and miR156h-p-5p was highly expressed in root, respectively (Fig. 3A). While there are two nucleotide differences between these miRNA isoforms (Supplementary Table S2), their predicted target repertoires are almost overlapped with each other (Supplementary Table S4). Although the repertoires are nearly identical, details are quite different in terms of target affinity. For example, one of the predicted targets (MGA0.9.scaffold2887G00090;1) belonging to SPL family has different penalty scores against each miRNA isoform. The penalty scores are 2.5 against miR156a-g-5p and 1 against miR156h-p-5p, respectively. Likewise, there are many other genes, such as MGA0.9. scaffold4486G00120;1 and MGA0.9.scaffold2429G00200;1 (Supplementary Table S4). Collecting the differences in expression and target affinity of the miRNA isoforms, it indicates the possibility that miRNA target genes are differently regulated by miRNA isoforms in different tissues. Another case supports this possibility. miR319-a-j-3p expression was higher in reproductive tissues (Fig. 3A), whereas miR319k-n-3p expression was higher in root. Similarly, there are two nucleotide differences between these miRNA isoforms (Supplementary Table S2), but their target repertoires are identical and target affinities are different (Supplementary Table S4). MGA0.9.scaffold21723G00010;1 is GAMYB-like gene and it prefer miR-319a-j-3p (penalty score: 1.5) to miR319-k-n-3p (penalty score: 4.5) as a regulator. Consequently, the target gene might be strongly repressed in reproductive tissues and weakly repressed in root. In conclusion, WGD might provide more complicated layer of control of genes in H. syriacus compared with other species.

Novel miRNA targets include pentatricopeptide repeat-containing (PPR) proteins, serine/threonine-protein kinase, receptor-like protein (RLP) and transcription factor MYC2-like. Most novel miRNAs exhibited weaker expressions than conserved miRNAs. The only exception was miR-n001a-b-3p, which is expressed as much as conserved miRNAs (Table 3), indicating that miR-n001a-b-3p may have an important biological role in H. syriacus. A predicted target of miR-n001a-b-3p is the PPR. The PPR family is one of the largest protein families in land plants and plays a role in plant development and growth (Barkan and Small, 2014). The PPR protein typically influences organelle biogenesis and function, including that for chloroplasts or mitochondria (Barkan and Small, 2014). miR-n001a-b-3p is predicted to target many PPRs, unlike other novel miRNAs (Supplementary Table S4). In addition, miR-n001a-b-3p is highly expressed in the leaf compared to that in any other tissues (Fig. 3). Thus, miR-n001a-b-3p might be involved in leaf development or photosynthesis. Furthermore, miR-n007a-5p is expected to target PPRs (Table 3), and its expression pattern was similar to that of miR-n001a-b-3p. Therefore, its function probably resembles the function of miR-n001ab-3p. RLP is another target of novel miRNAs and is a subcategory of receptor-like protein kinase; it recognizes pathogens to trigger plant defense mechanisms or control development (Afzal et al., 2008). In our prediction, miRn006a-5p.1 and miR-n006b-5p.1 target RLPs. Therefore, they might be involved in the immunity of H. syriacus with miR482.

In contrast to conserved miRNAs, we were unable to validate some targets of novel miRNAs via the 5′ RLM-RACE analysis (data not shown). It is in agreement with earlier studies that the targets of novel miRNAs are generally not identifiable (Hwang et al., 2013; Moxon et al., 2008). There are possible reasons as follows: (1) the abundance of most novel miRNAs were not high enough to direct the cleavage of mRNA targets, (2) target mRNAs and miRNAs were not colocalized or coexpressed (Cuperus et al., 2011), (3) the mode of novel miRNA action is repression at the protein level (Aukerman and Sakai, 2003), (4) the gene annotation of H. syriacus was not complete, and (5) most targets of novel miRNAs had higher penalty scores than those of conserved miRNAs (i.e., a relatively poor sequence complementarity) (Hwang et al., 2013).

In this study, we discovered 93 conserved and 36 novel miRNA sequences from a small RNA library of the novel species H. syriacus by implementing and applying an end-to-end pipeline for the analysis. In addition, we identified miRNA targets of H. syriacus in silico. Targets of many conserved miRNAs and several novel miRNAs are consistent with previous studies, showing that H. syriacus shares a lot of biological properties and pathways with model plants. Some miRNAs and their targets showed potential of species-specific regulations, including flower development, terpene synthesis, and disease resistance. Differential expression profiles revealed a tissue specificity of many miRNA sequences, implying the importance of each sequence for orchestrating gene expression at different sites and scales. Future work will entail experimental validation of miRNA sequences and their target cleavage. Finally, functional analysis of the target genes described in this study could provide a deeper interpretation of miRNA-mediated regulation in H. syriacus.

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Dong-Hoon Jeong in Hallym University for helpful discussion. We also thank the members of Shin laboratory for their critical comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (No. PJ01115601), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Molecules and Cells website (www.molcells.org).

REFERENCES

- Afzal AJ, Wood AJ, Lightfoot DA. Plant receptor-like serine threonine kinases: roles in signaling and plant defense. Mol Plant-Microbe Int. 2008;21:507–517. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-5-0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aukerman MJ, Sakai H. Regulation of flowering time and floral organ identity by a microRNA and its APETALA2-like target genes. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2730–2741. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkan A, Small I. Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2014;65:415–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boualem A, Laporte P, Jovanovic M, Laffont C, Plet J, Combier J-P, Niebel A, Crespi M, Frugier F. MicroRNA166 controls root and nodule development in Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 2008;54:876–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421–421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall R, Rodriguez RE, Debernardi JM, Palatnik JF, Casati P. Repression of growth regulating factors by the MicroRNA396 inhibits cell proliferation by UV-B radiation in arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell. 2013;25:3570–3583. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.117473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuperus JT, Fahlgren N, Carrington JC. Evolution and functional diversification of MIRNA cenes. Plant Cell. 2011;23:431–442. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.082784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Zhao PX. psRNATarget: a plant small RNA target analysis server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W155–W159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez L, Bussell JD, Păcurar DI, Schwambach J, Păcurar M, Bellini C. Phenotypic plasticity of adventitious rooting in arabidopsis is controlled by complex regulation of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR transcripts and microRNA abundance. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3119–3132. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang D-G, Park JH, Lim JY, Kim D, Choi Y, Kim S, Reeves G, Yeom S-I, Lee J-S, Park M, et al. The Hot Pepper (Capsicum annuum) MicroRNA Transcriptome reveals novel and conserved targets: a foundation for understanding microRNA functional roles in hot pepper. Plos One. 2013;8:e64238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Jung J-H, Reyes JL, Kim Y-S, Kim S-Y, Chung K-S, Kim JA, Lee M, Lee Y, Narry Kim V, et al. microRNA-directed cleavage of ATHB15 mRNA regulates vascular development in Arabidopsis inflorescence stems. Plant J. 2005;42:84–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Park JH, Lim CJ, Lim JY, Ryu J-Y, Lee B-W, Choi J-P, Kim WB, Lee HY, Choi Y, et al. Small RNA and transcriptome deep sequencing proffers insight into floral gene regulation in Rosa cultivars. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:657. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y-M, Kim S, Koo N, Shin A-Y, Yeom S-I, Seo E, Park S-J, Kang W-H, Kim M-S, Park J, et al. Genome analysis of Hibiscus syriacus provides insights of polyploidization and indeterminate flowering in woody plants. DNA Res. 2017;24:71–80. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsw049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T, Furutani M, Tasaka M, Ohme-Takagi M. TCP transcription factors control the morphology of shoot lateral organs via negative regulation of the expression of boundary-specific genes in arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:473–484. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D68–D73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Yoo SJ, Park SH, Hwang I, Lee JS, Ahn JH. Role of SVP in the control of flowering time by ambient temperature in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:397–402. doi: 10.1101/gad.1518407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhang Q, Zhang J, Wu L, Qi Y, Zhou J-M. Identification of microRNAs involved in pathogen-associated molecular pattern-triggered plant innate immunity. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:2222–2231. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.151803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers BC, Axtell MJ, Bartel B, Bartel DP, Baulcombe D, Bowman JL, Cao X, Carrington JC, Chen X, Green PJ. Criteria for annotation of plant MicroRNAs. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3186–3190. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moxon S, Jing R, Szittya G, Schwach F, Rusholme Pilcher RL, Moulton V, Dalmay T. Deep sequencing of tomato short RNAs identifies microRNAs targeting genes involved in fruit ripening. Genome Res. 2008;18:1602–1609. doi: 10.1101/gr.080127.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag A, King S, Jack T. miR319a targeting of TCP4 is critical for petal growth and development in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:22534–22539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908718106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa M, Miura S, Nei M. Origins and evolution of microRNA genes in plant species. Genome Biol Evol. 2012;4:230–239. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantaleo V, Szittya G, Moxon S, Miozzi L, Moulton V, Dalmay T, Burgyan J. Identification of grapevine microRNAs and their targets using high-throughput sequencing and degradome analysis. Plant J. 2010;62:960–976. doi: 10.1111/j.0960-7412.2010.04208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Shin C. MicroRNA-directed cleavage of targets: mechanism and experimental approaches. BMB Rep. 2014;47:417–423. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2014.47.8.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Shin C. The role of plant small RNAs in NB-LRR regulation. Brief Func Genomics. 2015;14:268–274. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elv006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Xia Z, Chen L, Shi M, Pu J, Guo J, Fan Z. Rapid and Efficient Isolation of High-Quality Small RNAs from Recalcitrant Plant Species Rich in Polyphenols and Polysaccharides. Plos One. 2014;9:e95687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez RE, Mecchia MA, Debernardi JM, Schommer C, Weigel D, Palatnik JF. Control of cell proliferation in Arabidopsis thaliana by microRNA miR396. Development. 2010;137:103–112. doi: 10.1242/dev.043067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K, Chen X. Biogenesis, Turnover, and mode of action of plant microRNAs. Plant Cell Online. 2013 doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.113159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Somoza I, Weigel D. Coordination of flower maturation by a regulatory circuit of three microRNAs. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si-Ammour A, Windels D, Arn-Bouldoires E, Kutter C, Ailhas J, Meins F, Vazquez F. miR393 and secondary siRNAs regulate expression of the TIR1/AFB2 auxin receptor clade and auxin-related development of Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:683–691. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.180083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotta E. On the normalization of the minimum free energy of RNAs by sequence length. Plos One. 2014;9:e113380. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal EA, Araus V, Lu C, Parry G, Green PJ, Coruzzi GM, Gutiérrez RA. Nitrate-responsive miR393/AFB3 regulatory module controls root system architecture in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4477–4482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909571107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet O. Origin, biogenesis, and activity of plant microRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:669–687. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Senthil-Kumar M, Ryu C-M, Kang L, Mysore KS. Phytosterols play a key role in plant innate immunity against bacterial pathogens by regulating nutrient efflux into the apoplast. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:1789–1802. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.189217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L, Grigg SP, Xie M, Christensen S, Fletcher JC. Regulation of Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem and lateral organ formation by microRNA miR166g and its AtHD-ZIP target genes. Development. 2005;132:3657–3668. doi: 10.1242/dev.01942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Park MY, Conway SR, Wang J-W, Weigel D, Poethig RS. The sequential action of miR156 and miR172 regulates developmental timing in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2009;138:750–759. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M-F, Tian Q, Reed JW. Arabidopsis microRNA167 controls patterns of ARF6 and ARF8 expression, and regulates both female and male reproduction. Development. 2006;133:4211–4218. doi: 10.1242/dev.02602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C-Y, Huang Y-H, Lin C-P, Lin Y-Y, Hsu H-C, Wang C-N, Liu L-YD, Shen B-N, Lin S-S. MicroRNA396-targeted SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE is required to repress flowering and is related to the development of abnormal flower symptoms by the phyllody symptoms1 effector. Plant Physiol. 2015;168:1702–1716. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N, Niu Q-W, Ng K-H, Chua N-H. The role of miR156/SPLs modules in Arabidopsis lateral root development. Plant J. 2015;83:673–685. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Gao S, Zhou X, Xia J, Chellappan P, Zhou X, Zhang X, Jin H. Multiple distinct small RNAs originate from the same microRNA precursors. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R81–R81. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Li D, Li Z, Hu Q, Yang C, Zhu L, Luo H. Constitutive expression of a miR319 gene alters plant development and enhances salt and drought tolerance in transgenic creeping bentgrass. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:1375–1391. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.208702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q-H, Helliwell CA. Regulation of flowering time and floral patterning by miR172. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:487–495. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.