Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to determine the biofilm formation, the extracellular enzymatic activities of 182 clinical isolates of the Candida parapsilosis complex.

Methods

Molecular identification of the C. parapsilosis species complex was performed using PCR RFLP of SADH gene and PCR sequencing of ITS region. The susceptibility of ours isolates to antifungal agents and molecular mechanisms underlying azole resistance were evaluated.

Results

63.5% of C. parapsilosis were phospholipase positive with moderate activity for the majority of strains. None of the C. metapsilosis or C. orthopsilosis isolates was able to produce phospholipase. Higher caseinase activities were detected in C. parapsilosis (Pz = 0.5 ± 0.18) and C. orthopsilosis (Pz = 0.49 ± 0.07) than in C. metapsilosis isolates (Pz = 0.72 ± 0.1). 96.5% of C. parapsilosis strains and all isolates of C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis produced gelatinase. All the strains possessed the ability to show haemolysis on blood agar. C. metapsilosis exhibited the low haemolysin production with statistical significant differences compared to C. parapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis. The biofilm forming ability of C. parapsilosis was highly strain dependent with important heterogeneity, which was less evident with both C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis.

Some C. parapsilosis isolates met the criterion for susceptible dose dependent to fluconazole (10.91%), itraconazole (16.36%) and voriconazole (7.27%). Moreover, 5.45% and 1.82% of C. parapsilosis isolates were respectively resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole. All strains of C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis were susceptible to azoles; and isolates of all three species exhibited 100% of susceptibility to caspofungin, amphotericin B and 5-flucytosine.

Conclusions

A combination of molecular mechanisms, including the overexpression of ERG11, and genes encoding efflux pumps (CDR1, MDR1, and MRR1) were involved in azole resistance in C. parapsilosis.

Keywords: Candida parapsilosis Complex, Virulence factors, Proteases, Phospholipases, Haemolysin, Biofilm production, Antifungal susceptibility, Mechanisms of resistance

Background

The Candida parapsilosis complex has emerged as an opportunistic fungal pathogen especially notable for causing nosocomial infections worldwide. It is composed of three genetically distinct species, namely C. parapsilosis sensu stricto, C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis, which are physiologically and morphologically indistinguishable [54]. Previous data have shown that these three species exhibit different prevalence rates, virulence, and in vitro antifungal susceptibility [3, 23, 56, 59].

Many virulence factors contribute to the pathogenesis of candidiasis, allowing the fungal cells to escape and/or overcome the host defenses. Among these factors proposed in the literature, adherence to host cells and/or tissues as well as to inert supports, phenotypic switching, biofilm formation and secretion of a large array of hydrolytic enzymes are included [1, 45, 47, 60]. But differences in these virulence factors among C. parapsilosis complex species have not been widely investigated. Aggravating this scenario, many contra-dictory results have been generated [64]. So, further studies are needed to better understand the characteristics, including putative virulence traits, drug resistance trends, especially of the two rarely isolated species, C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis. A better knowledge could have clinical relevance, as it may be useful in guiding therapeutic decisions [13].

The aim of our study was to investigate the distribution of five virulence factors namely: biofilm production, caseinase, gelatinase, phospholipase and haemolysin extracellular production among C. parapsilosis complex isolates. The association of these virulence factors with resistance to antifungal agents was studied and the susceptibility of ours isolates to antifungal agents was evaluated in vitro. Additional aim of this study was to assess the relative contribution of the number of copies of drug resistance genes and their overexpressions to the azole resistance of C. parapsilosis.

Methods

Fungal strains

A total number of 182 C. parapsilosis complex species isolates included in this study were recovered from clinical samples received by Department of Parasitology – Mycology-university hospital - Sfax, Tunisia, during a 14 year period (from January 2002 to January 2016). They were 172 strains of C. parapsilosis sensu stricto, 6 strains of C. metapsilosis and 4 strains of C. orthopsilosis. Isolates were identified to the species level by standard methods. Molecular identification of the C. parapsilosis species complex was performed by BanI PCR RFLP of SADH gene according to Tavanti A et al. [54], and supplemented, as needed by internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1), 5.8S, and ITS2 region rRNA sequence analysis [62]. Ten of these isolates were as reference strains, identified by ITS sequence analysis of the ribosomal DNA, and deposed in GenBank: C. parapsilosis sensu stricto (KT948326), C. metapsilosis (KU665248, KU665249, KU665250, KU665251 and KU665252) and C. orthopsilosis (KU665253, KU665254, KU665255, and KU665256).

Seven reference strains were included: C. parapsilosis (ATCC 22019), C. orthopsilosis (1,219,482, 1,343,124), C. metapsilosis (1240011), C. albicans (ATCC 3153), C. glabrata (CBS 138) and C. tropicalis (ATCC 66029).

Phospholipase activity

Phospholipase activity of Candida species was detected by egg yolk agar method [40]. The egg yolk medium consisted of 65 g Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA), 55.3 g NaCl, 5.5 g CaCl2 and 10% sterile egg yolk. Ten microliters of saline suspension prepared from a 48 h yeast culture (approximately 106 cells/ml determined through densitometer) was spot inoculated in triplicate onto the medium and incubated at 37 °C for 7 days. The diameter of the colony (a) and the diameter of the precipitation zone plus the diameter of the colony (b) were measured. Phospholipase index was designated as Pz = a/b, as described by Price et al. [40]. According to this definition, low Pz values mean high enzymatic production and, inversely, high Pz values indicate low enzymatic production. The enzymatic activity was scored into four categories: a Pz of 1.0 indicated no enzymatic activity; a Pz between 0.99 and 0.90 indicated weak enzymatic activity; Pz between 0.89 and 0.70 corresponded to moderate activity; and low Pz values ≤0.69 meant strong enzymatic activities.

Proteinase activity

For testing the proteinase activity of the Candida isolates, caseinase, and gelatinase activity tests were performed. A standard inoculum (106 cells/ml) was prepared in saline solution from a 48 h yeast culture for each isolate.

Caseinase activity

Caseinase activity was measured by single diffusion technique in SDA agar plates provided with 1% casein [41]. Three aliquots of 10 μl of standard inoculum were spotted for each strain. The plate was then incubated at 37 °C for 5 days. The zone of clearance was measured by standard procedures.

Gelatinase activity

Gelatinase assay was done on SDA agar plates prepared with 1% gelatin [41]. Single diffusion technique was applied in triplicate. The plate was then incubated for 5 days at 37 °C. The appearance of inhibition zone was clearly visualized by the addition of 0.1% mercuric chloride. The zone diameter was measured by standard procedures [2].

Haemolytic activity

Haemolysin assay for Candida strains was performed according to a previously validated protocol by Luo G et al. [31]. In brief, Sabouraud dextrose agar supplemented with 6% human blood and 3% glucose (pH = 5.6) was used to determine the hemolysin production. Suspension of yeast (106 cells/ml) was prepared in saline solution and 10 μl was spot inoculated on human blood agar plates, incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 5 days. The haemolytic activity was calculated by dividing the diameters of the colony and the translucent zone of haemolysis.

Biofilm formation

The in vitro Biofilm formation of Candida parapsilosis complex isolates was quantified by a modification of a crystal violet assay as described by Silva S et al. [50] with some modifications. Briefly, Candida isolates were first cultured at 37 °C for 24 h on SDA plates. 200 μl of standardized cell suspensions (containing 1 _ 106 cells ml −1 in yeast peptone galactose medium (YPG)) were trans-ferred to each well of 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates (Kartell. SPA, Italy) and incubated at 37 °C on a shaker at 120 rpm/min. As a negative control, test medium without cells was added to three wells of each plate. At 24 h, 50 μl of YPG medium was added. The preparations were then incubated for a further 48 h. After the adhesion stage, non-adherent cells were removed by washing the wells twice with sterile ultra-pure water. Biofilms were fixed with 250 μl of methanol, which was removed after 15 min of contact. The microtiter plates were dried at room temperature, and 250 μl of crystal violet (CV) (1% v/v) added to each well and incubated for 5 min. The wells were then gently washed with sterile, ultra-pure water and 250 μl of acetic acid added to release and dissolve the stain. The absorbance of the obtained solution was read in triplicate in a microtiter plate reader (Halo LED 96, Dynamica, EU) at 620 nm. The absorbance values for the controls (containing no cells) were subtracted from the values for the test wells to eliminate spurious results due to background interference. Data were recorded as arithmetic means of absorbance values. Experiments were repeated as part of three independent assays.

Antifungal susceptibility testing

Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed as part of routine patient care. The in vitro susceptibility to eight antifungal drugs (fluconazole, itraconazole, ketoconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole, caspofungin, amphotericin B and 5-flucytosine) was determined using Sensititre Yeast OneTM YO8 methodology (Trek Diagnostic Systems) following the manufacturer’s Instructions. minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were interpreted according to the M27-A3 and M27-S4 documents published by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (CLSI 2008, CLSI 2012) [38, 39]. The clinical breakpoints defined for Candida parapsilosis were used for the interpretation of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) data as follows: susceptible (S) ≤2 μg/ml, susceptible dose dependent (SDD) 4 μg/ml, resistant (R) ≥8 μg/ml for fluconazole; S ≤ 0.125 μg/ml, SDD 0.25–0.5 μg/ml, R ≥ 1 μg/ml for itraconazole; S ≤ 0.125 μg/ml, S-DD 0.25–0.5 μg/ml, R ≥ 1 μg/ml for voriconazole; S ≤ 2 μg/ml, intermediate (I) 4 μg/ml, R ≥ 8 μg/ml for caspofungin; and S ≤ 4 μg/ml, I 8–16 μg/ml, R ≥ 32 μg/ml for 5-flucytosine. For amphotericin B, we adopted putative breakpoints as S, ≤1 mg/l and R, >1 μg/ml [37].

Mechanisms of azole resistance

A RT-qPCR assay was developed to explore mechanisms of C. parapsilosis azole resistance. The levels of mRNA and DNA of the tested genes (ERG11, CDR1, MDR1, and MRR1) and the actin reference gene (ACT1) were measured. The primers and probes were designed using Primer3 software (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/) and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The sequences of primers and probes used in RT-qPCR

| Gene | Primers and probes | |

|---|---|---|

| ACT1 | F | 5′- CGAACGTGGTTACGGTTTCT- 3’ |

| R | 5′- TGACCATCTGGCAATTCGTA - 3’ | |

| Probe | TET-TGCAAACCTCATCACAATCA-MGB | |

| CDR1 | F | 5′- GCTGTTGATCAAAGGGGTGT - 3’ |

| R | 5′- ATCCAAAATCCAGGCAACTG - 3’ | |

| Probe | FAM- CTGATAATGCCGCCAATCTT-MGB | |

| ERG11 | F | 5′- TGTTGCATTTGGCTGAGAAG - 3’ |

| R | 5′- TCTGAGGGTTTCCTTGATGG - 3’ | |

| Probe | FAM-GGTAAAGGTGGCAACTTGGA-MGB | |

| MDR1 | F | 5′- TCCCCATTGCTATTGTTGGT - 3’ |

| R | 5′- TGCGCCCATATAATTGAACA - 3’ | |

| Probe | FAM- TTGGTCGGCAACGACATATA-MGB | |

| MRR1 | F | 5′- CAGCTGCAACAACCACAACT - 3’ |

| R | 5′- TATCATCTAGGCCGCCATTC - 3’ | |

| Probe | FAM- GCAACCACAGCCTATAGGGA-MGB |

Cellular lysates were prepared from cells grown in culture to mid-log phase using proteinase K (Qiagen®). RNA was extracted from cellular lysates using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen®, Germany) according to the manufacturer s’ instructions, and treated with DNase (Promega). For cDNA synthesis, 2.5 μl of total RNA was used as a template and subsequent reverse transcription was performed using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Perfect Real Time) from TaKaRa (Shiga, Japan), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

The reaction mixture (20 μl) for TaqMan assay contained 10 μl TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, UK), 20 pmol of forward and reverse primers, 7 pmol of hydrolysis probe and 1 μl of of template (extracted DNA or cDNA). The thermal conditions were as follows: initial holding stage at 50 °C for 2 min and 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 50 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and a final step at 54 °C for 1 min. All reactions were performed in triplicate in 48-well reaction plates using a StepOne™ Real Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems).

The software StepOne™ version 2.1 (Applied Biosystems) was used to collect Cq data and to calculate the relative quantification (RQ). Fold changes in target gene expression were then normalized to reference gene via the published comparative 2–∆∆Cq method according to the formula: RQ = 2–(Cq target – Cq reference) tested – (Cq target–Cq reference) control. A change of 2.5 times was considered as gene overexpression or an increase in gene copy number [26, 63].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software (version 20.0; IBM SPSS Inc., New York, USA). Categorical variables were compared using the ×2 or Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables by the ANOVA test. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test were used to evaluate the level of statistical significance of clustering. A P value of 0.05 was considered significant. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was calculated to measure correlation between different virulence factors. Where the value r = 1, means a perfect positive correlation, the value r = 0, means no correlation and the value r = −1, means a perfect negative correlation.

Results

In our study, we evaluated the in vitro capacities of 172 C. parapsilosis isolates, 6 C. metapsilosis isolates, 4 C. orthopsilosis isolates and 32 C. albicans isolates to produce phospholipase, hemolysin and proteases (caseinase and gelatinase enzyme). Enzymatic activities of tested isolates were expressed as mean ± SD (Table 2), and activity distributions were summarized in Table 2. All the fungal strains were able to produce at least two types of hydrolytic enzymes. Table 3 presented the data from the variance analyses of the different clinical samples from which the strains were isolated and the levels of the different virulence factors.

Table 2.

Level of phospholipase, caseinase, gelatinase and hemolysin production by C. parapsilosis complex species and C. albicans

| Phospholipase activity (number of isolates /rate of isolates) |

Caseinase activity (number of isolates /rate of isolates) |

Gelatinase activity (number of isolates /rate of isolates) |

Hemolysin activity (number of isolates /rate of isolates) |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (Pz) ± SD |

Strong n (%) |

Moderate n (%) |

Weak n (%) |

Nul n (%) |

Mean (Pz) ± SD |

Strong n (%) |

Moderate n (%) |

Weak n (%) |

Nul n (%) |

Mean (Pz) ± SD |

Strong | Moderate | Weak | nul | Mean (Pz) ± SD |

Strong | Moderate | Weak | nul | |

| C.parapsilosis Complex (n = 182) | 0.86 ±0.13 |

16 (8.8) |

92 (50.5) |

3 (1.6) |

71 (39) |

0.51 ±0.18 |

156 (85.7) |

10 (5.5) |

1 (0.5) |

15 (8.2) |

0.71 ±0.09 |

85 (46.7) |

91 (50) |

0 (0) |

6 (3.3) |

0.62 ±0.1 |

141 (77.5) |

41 (22.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| C.parapsilosis (n = 172) | 0.85 ±0.12 |

16 (9.3) |

92 (53.5) |

3 (1.7) |

61 (35.5) |

0.5 ±0.18 |

150 (87.2) |

6 (3.5) |

1 (0.6) |

15 (8.7) |

0.71 ±0.09 |

81 (47.1) |

85 (49.4) |

0 (0) |

6 (3.5) |

0.61 ±0.09 |

137 (79.7) |

35 (20.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| C.metapsilosis (n = 6) | 1 ±0 |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

6 (100) |

0.72 ±0.1 |

2 (33.3) |

4 (66.7) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.72 ±0.11 |

3 (50) |

3 (50) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.81 ±0.08 |

1 (16.7) |

5 (83.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| C.orthopsilosis (n = 4) | 1 ±0 |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

4 (100) |

0.49 ±0.07 |

4 (100) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.71 ±0.04 |

1 (25) |

3 (75) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.63 ±0.09 |

3 (25) |

1 (75) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| C.albicans (n = 32) | 0.62 ±0.16 |

26 (81.3) |

2 (6.3) |

0 (0) |

4 (12.5) |

0.69 ±0.12 |

19 (59.4) |

9 (28.1) |

4 (12.5) |

0 (0) |

0.72 ±0.04 |

7 (21.9) |

25 (78.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.7 ±0.11 |

15 (46.9) |

16 (50) |

1 (3.1) |

0 (0) |

N: number of tested isolates

n: number of isolates with positive activity for the corresponding hydrolytic enzyme

SD: standard deviation

Table 3.

Distribution of enzymatic activities from C. parapsilosis complex species isolated from different clinical sites

| Phospholipase activity Mean (Pz) ± SD |

Caseinase activity Mean (Pz) ± SD |

Gelatinase activity Mean (Pz) ± SD |

Hemolysin activity Mean (Pz) ± SD |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C.parapsilosis

(n/N) |

C.metapsilosis

(n/N) |

C.orthopsilosis

(n/N) |

C.parapsilosis

(n/N) |

C.metapsilosis

(n/N) |

C.orthopsilosis

(n/N) |

C.parapsilosis

(n/N) |

C.metapsilosis

(n/N) |

C.orthopsilosis

(n/N) |

C.parapsilosis

(n/N) |

C.metapsilosis

(n/N) |

C.orthopsilosis

(n/N) |

|

| Blood (N = 64) | 0.82 ± 0.12 (46/62) |

1 (0/1) |

1 (0/1) |

0.46 ± 0.13 (60/62) |

0.71 (1/1) |

0.49 (1/1) |

0.7 ± 0.07 (61/62) |

0.65 (1/1) |

0.65 (1/1) |

0.6 ± 0.09 (62/62) |

0.87 (1/1) |

0.73 (1/1) |

| Urine (N = 31) | 0.89 ± 0.12 (16/29) |

1 (0/1) |

1 (0/1) |

0.52 ± 0.21 (25/29) |

0.67 (1/1) |

0.46 (1/1) |

0.71 ± 0.11 (27/29) |

0.8 (1/1) |

0.73 (1/1) |

0.62 ± 0.1 (29/29) |

0.86 (1/1) |

0.65 (1/1) |

| Auricular sample (N = 43) | 0.88 ± 0.12 (22/39) |

1 ± 0 (0/3) |

1 (0/1) |

0.59 ± 0.22 (31/39) |

0.73 ± 0.15 (3/3) |

0.59 (1/1) |

0.71 ± 0.08 (38/39) |

0.74 ± 0.14 (3/3) |

0.75 (1/1) |

0.62 ± 0.08 (39/39) |

0.75 ± 0.09 (3/3) |

0.51 (1/1) |

| Respiratory tract (N = 4) | 0.88 ± 0.15 (2/4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.45 ± 0.05 (4/4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.67 ± 0.04 (4/4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.62 ± 0.08 (4/4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Catheter (N = 9) | 0.88 ± 0.12 (5/9) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.39 ± 0.03 (9/9) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.68 ± 0.02 (9/9) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.61 ± 0.1 (9/9) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Skin (N = 8) | 0.82 ± 0.14 (5/7) |

1 (0/1) |

0 (0) |

0.38 ± 0.04 (7/7) |

0.72 (1/1) |

0 (0) |

0.71 ± 0.14 (6/7) |

0.67 (1/1) |

0 (0) |

0.6 ± 0.11 (7/7) |

0.84 (1/1) |

0 (0) |

| Nails (N = 2) | 1 ± 0 (0/2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.44 ± 0.02 (2/2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.78 ± 0.01 (2/2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.5 ± 0.01 (2/2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Oral cavity (N = 3) | 0.84 ± 0.07 (3/3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.49 ± 0.13 (3/3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.7 ± 0.03 (3/3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.57 ± 0.07 (3/3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Vagina (N = 1) | 0.89 (1/1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.35 (1/1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.67 (1/1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.64 (1/1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Peritoneal fluid (N = 1) | 0.74 (1/1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.47 (1/1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.8 (1/1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.57 (1/1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Hand carriage (N = 16) | 0.82 ± 0.13 (10/15) |

0 (0) |

1 (0/1) |

0.56 ± 0.2 (14/15) |

0 (0) |

0.44 (1/1) |

0.76 ± 0.09 (14/15) |

0 (0) |

0.71 (1/1) |

0.65 ± 0.11 (15/15) |

0 (0) |

0.63 (1/1) |

N: number of tested isolates

n: number of isolates with positive activity for the corresponding hydrolytic enzyme

SD: standard deviation

Phospholipase activity

Of the 172 isolates of C. parapsilosis, 111 (63.5%) were phospholipase positive. 92 (53.5.0%) had moderate activity. The mean Pz value for positive C. parapsilosis isolates was 0.85 ± 0.12. None of the C. metapsilosis or C. orthopsilosis isolates was able to produce phospholipase (Table 2). A significant difference in phospholipase activity was detected between C. parapsilosis and C. metapsilosis isolates (P = 0.028).

The phospholipase activity of C. albicans was statistically significantly higher than that of the C. parapsilosis complex species (P = 0.0001).

The strains isolated from blood culture, skin, and hand carriage of health workers showed similar Pz average values with no statistically significant differences observed among them (P > 0.668).

Caseinase activity

A total of 157 (92.3%) isolates of C. parapsilosis were caseinase producers, most of which (87.2%) showed strong enzymatic activity. For C. metapsilosis, all isolates were proteinase positive, 2 (33.3%) of which were shown to be strong producers. For C. orthopsilosis, the four isolates (100%) were strong producers.

Higher caseinase activities were detected in C. parapsilosis (0.5 ± 0.18) and C. orthopsilosis (0.49 ± 0.07) than in C. metapsilosis isolates (0.72 ± 0.1) with a statistical significant difference (P = 0.012).

Most caseinase-producing C. albicans strains had strong (59.4%) or moderate (28.1%) enzymatic activity. Statistical significant difference was observed between the mean caseinase indices of C. albicans and C. parapsilosis complex species (P = 0.0001).

It was noted that a higher percentage of C. parapsilosis isolates recovered from blood (96.8%), skin (100%) and catheter (100%) were positive for caseinase activity (Table 3). No statistical significant difference was observed between the mean caseinase indices and the clinical site of isolation (P > 0.356).

Gelatinase activity

The majority of tested fungal isolates showed gelatinase activity except for 6 among 172 C. parapsilopsis strains. 47.1% of C. parapsilosis and 50% of C. metapsilosis isolates exhibited low Pz values, which indicate high enzymatic production; whereas the majority of C. albicans isolates (78.1%) and C. orthopsilosis isolates (75%) displayed moderate Pz values.

No statistical significant difference was observed between the mean gelatinase Pz values of C. albicans and C. parapsilosis complex species (P = 0.698).

Gelatinase production was high in C. parapsilosis isolated from vaginal sample and respiratory tract (Pz =0.67). For C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis, strains isolated from blood culture exhibited stronger activities with lowest average Pz values (Table 3).

Haemolytic activity

All of the C. albicans, C. parapsilopsis, C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis isolates had haemolytic activity on human blood SDA. The majority (79.7%) of C. parapsilosis isolates showed a strong activity. But, the majority of C. metapsilosis (83.3%) and C. orthopsilosis (75%) isolates showed moderate activities. Moreover, C. metapsilosis exhibited the low hemolysin production with statistical significant differences compared to C. parapsilosis (P = 0.0001) and C. orthopsilosis (P = 0.026).

The haemolytic activity of C. albicans was statistically significantly lower than that of the C. parapsilosis isolates (P = 0.0001).

But, no statistical significant difference was observed between the mean hemolysin production and the clinical site of isolation (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

Biofilm formation

Table 4 presented the results of biofilm quantification using CV staining. Importantly, it was noticed that generally C. parapsilosis biofilms had more total biomass (average Abs620 = 0.475) compared with C. orthopsilosis (average Abs620 = 0.301) and C. metapsilosis (average Abs620 = 0.075).

Table 4.

Biofilm production from C. parapsilosis complex species isolated from different clinical sites

| C. parapsilosis | C. metapsilosis | C. orthopsilosis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean Abs ± SD | Range | N | Mean Abs ± SD | Range | N | Mean Abs ± SD |

Range | |

| Blood (N = 64) | 62 | 0.415 ± 0.625 | 0.009–3.093 | 1 | 0.055 | 0.055–0.055 | 1 | 0.304 | 0.304–0.304 |

| Urine (N = 31) | 29 | 0.770 ± 0.949 | 0.016–3.903 | 1 | 0.094 | 0.094–0.094 | 1 | 0.564 | 0.564–0.564 |

| Auricular sample (N = 43) | 39 | 0.347 ± 0.347 | 0.003–1.559 | 3 | 0.080 ± 0.056 | 0.031–0.142 | 1 | 0.191 | 0.191–0.191 |

| Respiratory tract (N = 4) | 4 | 0.804 ± 0.615 | 0.172–1.612 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Catheter (N = 9) | 9 | 0.611 ± 0.562 | 0.080–1.776 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin (N = 8) | 7 | 0.334 ± 0.372 | 0.044–1.070 | 1 | 0.061 | 0.061–0.061 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nails (N = 2) | 2 | 0.953 ± 1.303 | 0.032–1.875 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oral cavity (N = 3) | 3 | 1113 ± 0,718 | 0.283–1.547 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vagina (N = 1) | 1 | 0.824 | 0.824–0.824 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Peritoneal fluid (N = 1) | 1 | 0.263 | 0.263–0.263 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hand carriage (N = 16) | 15 | 0.182 ± 0.174 | 0.021–0.482 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.145 | 0.145–0.145 |

| Total (N = 182) | 172 | 0.475 ± 0.633 | 0.003–3.903 | 6 | 0.075 ± 0.038 | 0.031–0.142 | 4 | 0.301 ± 0.187 | 0.145–0.564 |

N: number of tested isolates

n: number of isolates with positive activity for the corresponding hydrolytic enzyme

SD: standard deviation

In contrast, C. parapsilosis strains were heterogeneous in terms of the level of biofilm formation with a range of 0.003–3.903 and a 1301-fold difference between the highest and lowest biofilm-producing strains. C. metapsilosis strains exhibited a more homogeneous behavior with all strains being low biofilm formers. But, no significant difference in biofilm-forming ability was detected between C. parapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis isolates (P = 0.384).

The mean Abs620 value for the C. albicans strains was 0.421 (±0.504, SD) with a range of 0.075–2.033. No statistical significant difference was observed between biofilm formation of this species and C. parapsilosis complex species (P = 0.967).

There was no statistically significant association between biofilm-forming ability and the clinical origin of the isolates (P > 0.05).

Correlation analysis results with Pearson’s coefficient revealed a positive correlation between secretion of caseinase and hemolysin (r = 0.219, P ≤ 0.01). Moreover, biofilm production was correlated to secretion of gelatinase (r = 0.148, P ≤ 0.05). But, a negative correlation (r = −0.234, P ≤ 0.01) between, biofilm production and phospholipase production was detected.

Antifungal susceptibility testing

The profiles of the in vitro susceptibility of C. parapsilosis complex species to to eight antifungal drugs are summarized in Table 5. According to the interpretative criteria for resistance used for the antifungal drugs described in the material and methods, we found that few isolates were resistant to azoles. Some C. parapsilosis isolates met the criterion for S-DD to fluconazole (10.91%), itraconazole (16.36%) and voriconazole (7.27%). Moreover, 5.45% and 1.82% of C. parapsilosis isolates were respectively resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole. All strains of C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis were susceptible to azoles; and isolates of all three species exhibited 100% of susceptibility to caspofungin, amphotericin B and 5-flucytosine.

Table 5.

In vitro susceptibility of C. parapsilosis complex species to eight antifungal drugs

| C. parapsilosis (N = 55) | C. metapsilosis (N = 6) | C. orthopsilosis (N = 4) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range μg/ml |

Mean μg/ml |

S % | SDD % | R % | Range μg/ml |

Mean μg/ml |

S % | SDD % | R % | Range μg/ml |

Mean μg/m |

S % | SDD % | R % | |

| Fluconazole | 0.25–32 | 2.427 | 83.64 | 10.91 | 5.45 | 0.5–1 | 0.833 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.25–0.5 | 0.437 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Itraconazole | 0.008–0.5 | 0.096 | 83.64 | 16.36 | 0 | 0.016–0.125 | 0.078 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.016–0.064 | 0.052 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Ketoconazole | 0.008–16 | 0.321 | ND | ND | ND | 0.008–0.016 | 0.013 | ND | ND | ND | 0.008–0.016 | 0.010 | ND | ND | ND |

| Posaconazole | 0.008–1 | 0.106 | ND | ND | ND | 0.016–0.08 | 0.040 | ND | ND | ND | 0.032–0.08 | 0.052 | ND | ND | ND |

| Voriconazole | 0.008–8 | 0.190 | 90.91 | 7.27 | 1.82 | 0.008–0.032 | 0.018 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.008–0.016 | 0.010 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Caspofungin | 0.032–1.5 | 0.426 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.064–0.25 | 0.136 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.064–0.25 | 0.126 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.016–1 | 0.293 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.064–0.5 | 0.240 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.064–0.25 | 0.172 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 5-Flucytosine | 0.03–2 | 0.110 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.03–0.03 | 0.030 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0.03–0.064 | 0.055 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

ND Not determined due to lack of validated clinical breakpoints, S susceptible, SDD dose-dependent susceptible, R resistant

Mechanisms of azole resistance

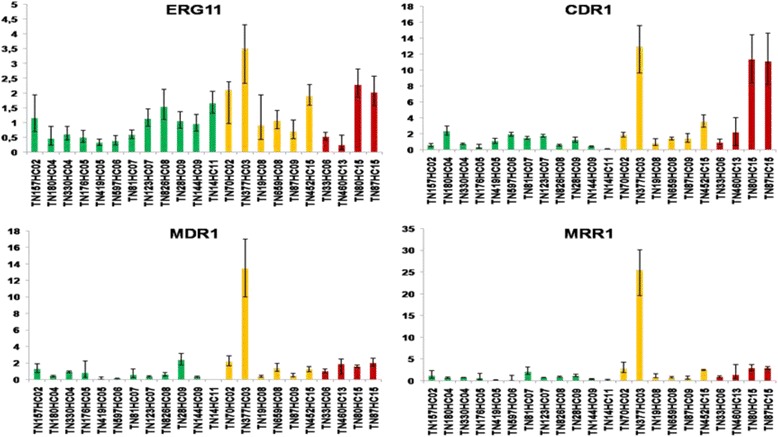

We were also interested in elucidating the molecular mechanisms associated with the resistance of clinical strains of C. parapsilosis to azoles. For this we analyzed by RT-qPCR the quantitative expression and copy number of four genes (CDR1, MDR1 and MRR1) responsible for the efflux of the azoles and the ERG11 gene (target of the azoles) of four resistant strains, six dose- dependent susceptible strains and twelve susceptible strains isolated from blood culture, comparing to the ACT1 gene and the susceptible strain TN106HC05 (GenBank Accession number KX421285). The overexpression of one or more genes was observed in five (50%) of the 10 clinical isolates of dose-dependent susceptible and resistant C. parapsilosis isolates (Fig. 1). None of these genes was overexpressed in the strains susceptibles to the different azoles (Table 6). An overexpression of the CDR1 and MRR1 genes was noted in 2 out of 4 resistant strains and 2 out of 6 dose-dependent susceptible strains. In susceptible strains, the level of expression of CDR1, MRR1 and MDR1 varied respectively from 0.077 to 2.296, 0.052 to 2.108 and 0 to 2.352. The level of expression of CDR1 varied from 0.88 to 12.99 folds and the level of MRR1 varied from 0.558 to 25.498 in resistant and dose-dependent susceptible strains. The overexpression of the CDR1 and MRR1 genes was significantly associated with the resistant and dose-dependent susceptible phenotype (P = 0.015). The overproduction of the MDR1 gene was observed in a single dose-dependent susceptible strain with a level of expression equal to 13.401. Overexpression of the MRR1 gene was correlated with overexpression of the MDR1 gene only for a single strain (TN377HC03) among the four strains over-expressing the transcription factor MRR1. For the ERG11 gene, overproduction was observed also in the single isolate (TN377HC03) with a dose-dependent susceptible phenotype and it was expressed 3.518 folds. No upregulation of ERG11 was noted in susceptible strains. The overexpression of the CDR1, MDR1 and ERG11 genes was not associated with an increased copy number of gene in our strains of C. parapsilosis. However, the presence of MRR1 transcription factor in multiple copies at the genome has been associated with overexpression in two dose-dependent susceptible strains of C. parapsilosis (Table 6).

Fig. 1.

Study of the level of expression of ERG11, CDR1, MDR1 and MRR1 genes by relative quantification with RT-qPCR in Candida parapsilosis: 12 susceptible strains (green bars), 6 dose-dependent susceptible strains (yellow bars) and 4 resistant strains (red bars). Error bars represent the relative maximum (RQ max) and minimum (RQ min) quantifications with one standard deviation

Table 6.

Antifungal susceptibility to the azoles and relative quantification of gene expression and gene copy number of ERG11, CDR1, MDR1 and MRR1 genes in Candida parapsilosis

| Strain | Posaconazole | Fluconazole | Itraconazole | Ketoconazole | Voriconazole | RNA relative quantification | DNA relative quantification | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | I | MIC | I | MIC | I | MIC | I | MIC | I | ERG11 | CDR1 | MDR1 | MRR1 | ERG11 | CDR1 | MDR1 | MRR1 | |

| TN157HC02 | 0,016 | ND | 0,5 | S | 0,064 | S | 0,008 | ND | 0,008 | S | 1153 | 0,527 | 1259 | 1169 | 1367 | 2042 | 1087 | 3437 |

| TN180HC04 | 0,032 | ND | 0,25 | S | 0,125 | S | 0,008 | ND | 0,008 | S | 0,445 | 2296 | 0,379 | 0,696 | 0,317 | 12,977 | 0,203 | 0,227 |

| TN330HC04 | 0,032 | ND | 0,5 | S | 0,016 | S | 0,008 | ND | 0,008 | S | 0,595 | 0,693 | 0,901 | 0,733 | 6578 | 9570 | 6364 | 7141 |

| TN176HC05 | 0,064 | ND | 1 | S | 0,064 | S | 0,016 | ND | 0,016 | S | 0,489 | 0,309 | 0,781 | 0,589 | 0,296 | 0,217 | 0,019 | 0,034 |

| TN419HC05 | 0,016 | ND | 0,5 | S | 0,008 | S | 0,008 | ND | 0,008 | S | 0,314 | 1045 | 0,053 | 0,117 | 0,357 | 0,461 | 0,105 | 0,958 |

| TN597HC06 | 0,032 | ND | 1 | S | 0,064 | S | 0,016 | ND | 0,016 | S | 0,367 | 1890 | 0,074 | 0,081 | 0,773 | 1613 | 0,247 | 3938 |

| TN81HC07 | 0,032 | ND | 0,25 | S | 0,032 | S | 0,008 | ND | 0,008 | S | 0,579 | 1457 | 0,524 | 2108 | 1961 | 1597 | 3665 | 0,895 |

| TN123HC07 | 0,032 | ND | 0,5 | S | 0,032 | S | 0,016 | ND | 0,032 | S | 1123 | 1729 | 0,327 | 0,731 | 0,973 | 0,766 | 1061 | 1971 |

| TN826HC08 | 0,016 | ND | 1 | S | 0,064 | S | 0,008 | ND | 0,016 | S | 1525 | 0,538 | 0,584 | 0,909 | 1421 | 1220 | 1257 | 0,979 |

| TN28HC09 | 0,08 | ND | 1 | S | 0,064 | S | 0,008 | ND | 0,016 | S | 1046 | 1196 | 2352 | 1166 | 0,929 | 1005 | 0,866 | 0,562 |

| TN144HC09 | 0,125 | ND | 2 | S | 0,032 | S | 0,016 | ND | 0,016 | S | 0,948 | 0,378 | 0,312 | 0,364 | 0,502 | 1006 | 0,343 | 2949 |

| TN14HC11 | 0,032 | ND | 0,25 | S | 0,064 | S | 0,008 | ND | 0,008 | S | 1644 | 0,077 | 0,000 | 0,052 | 0,261 | 1877 | 0,495 | 1913 |

| TN70HC02 | 0,5 | ND | 4 | SDD | 0,5 | SDD | 0,064 | ND | 0,125 | S | 2115 | 1841 | 2192 | 2812 | 4434 | 7221 | 3060 | 13,487 |

| TN377HC03 | 0,5 | ND | 4 | SDD | 0,25 | SDD | 0,125 | ND | 0,125 | S | 3518 | 12,990 | 13,401 | 25,498 | 0,506 | 2129 | 0,327 | 2977 |

| TN19HC08 | 0,5 | ND | 4 | SDD | 0,25 | SDD | 0,064 | ND | 0,5 | SDD | 0,906 | 0,819 | 0,375 | 0,761 | 0,469 | 0,881 | 0,636 | 1659 |

| TN659HC08 | 0,032 | ND | 4 | SDD | 0,5 | SDD | 0,125 | ND | 0,32 | SDD | 1055 | 1363 | 1381 | 0,725 | 1486 | 2482 | 0,878 | 0,907 |

| TN87HC09 | 0,125 | ND | 4 | SDD | 0,032 | S | 0,016 | ND | 0,016 | S | 0,697 | 1365 | 0,472 | 0,558 | 0,503 | 0,617 | 0,303 | 2681 |

| TN452HC15 | 0,032 | ND | 0,5 | S | 0,25 | SDD | 0,125 | ND | 0,125 | S | 1899 | 3504 | 1213 | 2489 | 0,411 | 1066 | 0,649 | 2711 |

| TN33HC06 | 1 | ND | 16 | R | 0,5 | SDD | 0,25 | ND | 0,25 | SDD | 0,518 | 0,880 | 0,971 | 0,874 | 1792 | 7426 | 1342 | 10,307 |

| TN460HC13 | 0,016 | ND | 0,5 | S | 0,016 | S | 16 | ND | 8 | R | 0,238 | 2184 | 1845 | 1313 | 0,568 | 1319 | 0,392 | 3028 |

| TN80HC15 | 0,5 | ND | 32 | R | 0,25 | SDD | 0,032 | ND | 0,008 | S | 2277 | 11,320 | 1563 | 2886 | 3320 | 0,490 | 2572 | 1425 |

| TN87HC15 | 0,5 | ND | 32 | R | 0,25 | SDD | 0,032 | ND | 0,008 | S | 2013 | 11,097 | 2016 | 2845 | 3472 | 0,444 | 2604 | 1262 |

I interpretation, ND Not determined due to lack of validated clinical breakpoints, S susceptible, SDD dose-dependent susceptible, R resistant, MIC in μg/ml

In addition, correlation analysis results with Pearson’s coefficient revealed that there was no statistically significant association between all virulence factors (biofilm-forming ability, gelatinase, caseinase, hemolysin, phospholipase) and the expression of the four genes (CDR1, MDR1 and MRR1) responsible for the efflux of the azoles and the ERG11 gene (P > 0.05).

Discussion

Multiple virulence factors such as extracellular secreted hydrolytic and biofilm development have been developed by Candida species to assist in their ability to colonize host tissues, cause disease, and overcome host defenses. Since the report that C. parapsilosis was a cryptic complex of three species, many epidemiological studies have been reported worldwide. However, a less number of studies focused on biochemical/metabolic properties, antifungal susceptibilities, virulence factors’ expression and pathogenesis of the three specie [1, 13, 36, 64]. Moreover, some discrepancies were observed in findings among studies from different geographical regions. So, we conducted this study to compare the pathogenic potential of Candida parapsilosis complex species isolated from various clinical samples based on the examination of the following features: hydrolytic enzyme production, biofilm formation, and antifungal susceptibilities.

Extracellular hydrolytic enzymes seem to play an important role in candidal overgrowth, as these enzymes facilitate adherence and tissue penetration and hence invasion of the host [47]. Phospholipases facilitate the invasion of host mucosal epithelia by hydrolysing one/more ester linkages in glycerophospholipids, which are believed to be involved in disrupting the host cell membranes [45]. In our study, among the 172 isolates of C. parapsilosis 63.5% were phospholipase positive with moderate activity for the majority of strains. Similarly, Treviño-Rangel Rde J et al. reported that 63% of the C. parapsilosis sensu stricto isolates exhibited phospholipase activity, and 53% were strong producers [59]. Others studies founded low or undetectable phospholipase activity among C. parapsilosis isolates [1, 13, 36, 64]. Though, the majority of phospholipase- negative C. parapsilosis isolates was able to produce another lypolytic enzyme such esterase [1].

None of the C. metapsilosis or C. orthopsilosis isolates was able to produce phospholipase as it was reported by others studies [13]. However, Treviño-Rangel Rde J et al. described that almost all of the C. orthopsilosis (97%) and C. metapsilosis (80%) isolates showed phospholipase activity [59]. Moreover, Ge YP et al. showed that 90.5% of C. parapsilosis and 91.7% of C. metapsilosis isolates were phospholipase producers with high proportion of strong production [23].

This wide variation in phospholipase activity of C. parapsilosis complex species is of interest. It was attributed to the use of different media for enzymatic test, small sample size, and/or inherent biological variations among isolates… [1, 13, 23].

Additionally, contrasting findings were also reported in studies comparing systemic and superficial isolates. Some investigators found positive activity only in blood isolates [59] while others identified a higher level of activity among superficial isolates [23]. In our study, we don’t found an interesting statistical association between the clinical origin of the isolates, particularly those recovered from blood and phospholipase production. But, it was interesting to note that the strains isolated from blood culture, skin, and hand carriage of health workers showed similar activity. Therefore, phospholipase production can become a parameter to distinguish virulent invasive strains from non-invasive colonizers [12, 45].

Proteinases exhibit broad substrate specificity and are capable of degrading host epithelial and mucosal barrier proteins such as albumin, collagen, keratin, and mucin. They also aid Candida to resist cellular and humoral immunity by degrading antibodies, complement, and cytokines [7]. Most of the studies on exoenzymes produced by C. parapsilosis complex species are focused on secreted aspartyl proteinases (SAP) which are secreted in vitro when the organism is cultured in the presence of exogenous protein (usually bovine serum albumin) as the nitrogen source. However, variable protease activity (ranged from 17% to 100%) has been found by different authors among C. parapsilosis sensu stricto isolates [1, 13, 34, 56, 59]. In this study, we opted to use casein and gelatin as substrates for evaluation of proteinase activity. 92.3% of C. parapsilosis isolates were caseinase producers, most of which (87.2%) showed strong enzymatic activity. Limited phenotypic data pertaining to the caseinolytic activities of C. parapsilosis complex species are available. The only previous study of caseinolytic activity among C. parapsilosis complex displayed that only 5O% of C. parapsilosis sensu stricto produced it [64].

Moreover, previous studies reported variable proteinase activity among the two others species of the cryptic complex. Some authors reported that none of the C. metapsilosis or C. orthopsilosis isolates exhibited proteinase activity [13, 56]. Sabino R et al. showed that C. orthopsilosis were SAP producers, whereas C. metapsilosis were not [44]. Others recent reports found also a high proportion of isolates of both C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis exhibiting protease activity [23, 34, 59]. Using casein as substrate, all ours isolates of C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis were proteinase positive. Higher caseinase activities were detected in C. parapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis than in C. metapsilosis isolates with a statistical significant difference. Ziccardi M et al. reported that none of C. orthopsilosis isolates was caseinase producer [64].

Interestingly, we showed that 96.5% of C. parapsilosis strains and all isolates of C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis produced gelatinase. But, none of C. albicans, C. glabrata and C. krusei isolates possessed the ability to hydrolyze gelatin in another study [41]. In the present data, statistical significant difference was observed between the mean indices of C. albicans and C. parapsilosis complex species for caseinase but not for gelatinase.

The ability to express proteinase enzymes not only varies among different species of Candida but also differs among the strains of same species isolated from different body sites [16, 42]. Corroborating these findings, De Bernardis F et al. identified positive proteolytic activity in all skin isolates of C. parapsilosis but none in blood ones [14]. Cassone A et al. also detected a higher proteolytic activity in vaginal C. parapsilosis isolates when compared with blood isolates [9]. Tosun I et al. described that urine-derived isolates have higher SAP activities [56]. However, we showed that no statistical significant association between anatomical origin and production of this virulence factor [55].

Haemolytic activity is another virulence factor exhibited by pathogenic microorganisms which permits growth in the host using as a source of iron the hemoglobin an iron-binding protein [30]. In this study, all the strains possessed the ability to show haemolysis on blood agar as it was reported by others investigations [1, 20]. Moreover, C. metapsilosis exhibited the low hemolysin production with statistical significant differences compared to C. parapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis. Treviño-Rangel Rde J et al. described that hemolysin activity was significantly more abundant in C. orthopsilosis (87%) than C. parapsilosis sensu stricto (67%) and C. metapsilosis (80%) [59]. Interestingly, we noted that the haemolytic activity of C. albicans was statistically significantly lower than that of the C. parapsilosis isolates, which contrasted with the finding of previous studies [12, 36].

Biofilm formation is considered a virulence factor due to the ability to confer resistance to antifungal therapy and protect the fungal cells from host immune responses [60]. It besides possibly being in Candida a key factor for the survival of these species, and may also be responsible for them being particularly well adapted to colonization of tissues and indwelling devices [50]. However, this issue is not completely clear, once the literature reports many controversial data about the biofilm-forming capacity of the three species of the C. parapsilosis complex [43]. In our study, these three species were able to form biofilm. This finding agrees with the results of previous studies [32, 43]. The species with the highest biofilm production was C. parapsilosis, followed by C. orthopsilosis and further by C. metapsilosis [32, 43]. Though, Lattif AA et al. reported that clinical isolates of C. parapsilosis, C. metapsilosis, and C. orthopsilosis were able to form biofilm with similar surface topography and architecture on abiotic surface (silicone disks) [28]. Some authors have reported that C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis isolates are not able to produce biofilms in vitro [15, 51, 56].

In the present work, it was noted also that the biofilm forming ability of C. parapsilosis was highly strain dependent with important heterogeneity, which was less evident with both C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis. Silva S et al. demonstrated that biofilm forming ability, structure and matrix composition are highly species dependent with additional strain variability occurring with C. parapsilosis [50]. Such findings undoubtedly reflect inherent physiological differences between strains and could have significance with respect to pathogenic potential [50]. So, investigations of biochemical and genetic mechanisms in biofilms are needed.

Interestingly, there was no statistically significant association between biofilm-forming ability and the clinical origin of ours isolates [13, 15, 50]. Others reports have demonstrated that blood biofilm production was linked to anatomical origin of isolates [55]. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that several of these mentioned studies are not directly comparable because they differ in important aspects, such as the biofilm formation process, the methods to evaluate biofilm production (i.e., crystal violet staining, XTT reduction assays, or measured transmittance or absorbance without staining), and the criteria for considering an isolate as a biofilm producer [13].

Interestingly, we found a statistically significant inverse correlation between phospholipase activity and the ability to form biofilm. This suggests that phospholipids are directly implicated in biofilm composition and stability, for C. parapsilosis complex species. According to Lattif AA et al., candida biofilms contained significantly higher levels of phospholipid and sphingolipids than planktonic cells and lipid rafts are critical to the ability of Candida to form biofilm [27].

Overall, our findings demonstrate that C. metapsilosis was the least virulent species of the psilosis group except for gelatinase activity, which was supported by the literature. In fact, according to the studies conducted in vitro or in vivo, C. metapsilosis has been reported as a less virulent member of the C. parapsilosis complex in an epithelial and epidermal tissue models [21], in an in vitro infection model using microglial cells [35], in a murine model of vaginal candidiasis [5] and also in an in vivo model system using Galleria mellonella larvae [34].

There is a growing concern related to antifungal susceptibility profiles of C. parapsilosis complex species. In this investigation, all C. parapsilosis isolates were susceptible to amphotericin B, and 5-flucytosine. Nevertheless, Some C. parapsilosis isolates met the criterion for S-DD to fluconazole (10.91%), itraconazole (16.36%) and voriconazole (7.27%). 5.45% and 1.82% of C. parapsilosis isolates were respectively resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole with some strains displayed a multiazole resistant phenotype [43, 49, 58]. These results are discordant with several studies demonstrating the greater efficacy of these new triazoles (i.e., voriconazole) against C. parapsilosis complex isolates [3].

According to the recently revised CBPs, none of our isolates were resistant to echinocandins [6, 55, 57]. Our data are inadequate to others surveys who described a reduced susceptibility to echinocandins probably due to a naturally occurring Proline to Alanine amino acid change (P660A) in the glucan synthase enzyme Fks1p [3, 22, 58]. Moreover, all C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis were sensitive to the others tested drugs. In contrast, some reports have shown that these two species exhibited low susceptibilities to amphotericin B [17, 43], to fluconazole [11, 13, 24, 53] and to itraconazole [3, 43]. However, because of the small number of isolates belonging to the newly identified species, our study may not provide an entirely accurate picture of the antifungal susceptibility patterns of C. parapsilosis complex species. So, testing more isolates is required for determination of virtual rates of resistance among the strains of the two former species.

Despite the potentially rising incidence of C. parapsilosis and the threat that fluconazole resistance could pose in a clonally expanding population, previous studies have provided limited information concerning molecular mechanisms of azole resistance in C. parapsilosis [25, 48, 52, 63]. Quantification of drug resistance gene expression in Candida isolates with reduced azole susceptibility is a valuable tool for understanding the molecular mechanism(s) of azole resistance and monitoring for the emergence of resistance [29]. To our knowledge, this is the first assessment at molecular level of azole resistance mechanisms in C. parapsilosis isolates from Tunisia. We assessed the quantitative expression of the ABC transporter CDR1, the MFS transporters MDR1, the zinc cluster transcription factor MRR1, and also ERG11.

In our study, we confirmed the involvement of drug transporters CDR1 and MDR1 in the phenomenon of azole resistance in strains. Our findings showed an increase in CDR1 expression in 50% of the resistant strains and 33.3% of the dose-dependent susceptible strains, suggesting that this transporter contributes to the azole resistance. According to Berkow EL et al. (2015), sixteen strains of C. parapsilosis resistant isolates (45.7%) showed an increased CDR1 expression with a minimum of 2-fold [4]. In contrast, all resistant isolates of C. parapsilosis expressed increased levels of CDR1 (3.3–9.2 fold) in the presence of fluconazole during the study of Souza AC et al. (2015); but with a varied expression of the two drug transporters genes. More isolates showed CDR1 overexpression than MDR1overexpression [52]. In addition, overexpression of CDR1 and CDR2 has been shown to lead to cross-resistance of the same isolate to multiple azole antifungals, whereas overexpression of MDR1 has been associated with fluconazole resistance only [19, 61]. It has also been reported that CDR1 is more closely associated with azole resistance than CDR2 in C. glabrata [46] and in C. albicans [10].

Berkow EL et al. (2015) have suggested that the overexpression of the putative drug transporters CDR1 was due to activating mutations in the genes encoding their transcriptional regulators. In fact, among 16 CDR1-overexpressing isolates, mutations G650E and L978 W leading to amino acid substitutions were detected in TAC1 in respectively 2 isolates and 1 isolate. None of these SNPs corresponded to a documented activating mutation in CaTAC1 of C. albicans [4]. Silva AP et al. (2011) suggested an overexpression of CDR1 in fluconazole induced resistant C. parapsilosis strains, since they observed upregulation of the transcription factor NDT80 which, in C. albicans, modulates azole tolerance by controlling the expression of the CDR1 gene [48].

For C. parapsilosis, Berkow EL et al. (2015) observed a marked overexpression of the major facilitator efflux pump MDR1 in only three (out of 35) resistant isolates with a minimum 25-fold increase [4]. The same was found to be true for the isolates of C. parapsilosis examined in the present study which showed an overexpression of MDR1 for only one strain. In addition, in the study realized by Souza AC et al. (2015), 2 of 9 isolates showed increased mRNA expression of MDR1 in the presence of fluconazole [52]. However, MDR1 expression was upregulated by 19.43 and 40.22 folds in the resistant strains obtained after exposure to fluconazole and to voriconazole [48]. As for C. albicans, overexpression of MDR in C. parapsilosis is also correlated with increased expression of aldo-keto reductases and other genes associated with the oxidative stress response, which may protect cells from damage caused by toxic molecules produced in the presence of azoles and also contribute to antifungal drug resistance. The expression of these genes is also regulated by MRR1 transcription factor [48].

The present study showed that the expression of MRR1 was also upregulated in C. parapsilosis. Silva AP et al. (2011) also correlated the overexpression of MDR1 and mutations within MRR1 with fluconazole resistance in resistant isolates of C. parapsilosis [48]. More recently, a surveillance study of a collection of clinical isolates of C. parapsilosis has again implicated MDR1 and MRR1 in resistance to fluconazole in this species [4]. As reported for C. albicans, upregulation of MRR1 may be caused by single gain-of-function mutations [18, 33]. Two mutations (G1747A and A2619C) were identified in the MRR1 coding sequence of azole-resistant C. parapsilosis isolates that resulted in an amino acid exchange (G583R and K873 N) [8, 48]. According to Zhang L et al. (2015), overexpression of MDR1 genes were detected in the two resistant isolates, and this was associated with a homozygous mutation in MRR1 genes (T2957C /T2957C), with the amino acid exchange L986P [63]. According to Grossman NT et al. (2015), polymorphisms in MRR1 are common, and only some are associated with overexpression of MDR1. They suggest that there is a hot spot for gain-of-function mutations in MRR1, in the region coding from amino acids 852 to 875.They identified one clinical isolate with a polymorphism in this region, corresponding to L779F (G2337 T), which has 73-fold upregulation of MDR1 [25].

The upregulation of the ERG11 gene was noted only in one dose-dependent susceptible isolate from this collection. However, in the study of Berkow EL et al. (2015), ERG11 was found to be overexpressed in many of the azole-resistant clinical C. parapsilosis isolates, as has been observed in C. albicans. Eight isolates (22.8%) exhibited a minimum increase in ERG11 expression from 2-fold to 11-fold in C. parapsilosis [4]. Silva AP et al. (2011) founded that expression of ERG11 was reduced in the resistant strains of C. parapsilosis [48]. This observation might be related to the fact that the ERG11 overexpression was assessed in the absence of exposure to azoles, likewise in our study [52]. Overexpression of ERG genes is correlated with increased expression of the transcription factors UPC2 and NDT80. In fact, a resistant strain obtained after exposure to posaconazole showed upregulation of these two transcription factors (UPC2 and NDT80) and increased expression of 13 genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis [48].

Other resistance mechanisms apart from those already described, such as mutations in the target enzymes, might be implicated [8, 48]. Grossman NT et al. (2015) also examined the sequences of ERG11 for the presence of amino acid substitutions. They identified the Y132F substitution as well and in fact observed it in 56.7% of their fluconazole- resistant isolates. They concluded that this mutation is perhaps largely responsible for most of the fluconazole resistance observed within this species [25].

Contrary to what was expected, the upregulation of the CDR1, MDR1 and ERG11 genes was also not associated with an increased copy number of gene in our strains of C. parapsilosis. Thus, the presence of genes that encode membrane transporters in multiple copies at the genome of C. parapsilosis was not responsible for an increase in transcription levels in our isolates. Thus, in these strains the upregulation of these genes is controlled by another molecular mechanism.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this investigation provides more information about the frequency of the production of the major enzymes considered to be virulence factors of C. parapsilosis complex species and reinforce the heterogeneity of this fungal complex. But, it still remains unclear what virulence factors may play a role in the final outcome. Moreover, the fact that phenotypic properties were found to significantly differ in strains isolated from various geographical regions suggests that other mechanisms such as epigenetic modifications may be used by this yeast to adapt to environmental changes [55]. Further in vivo studies are necessary and the molecular mechanisms of pathogenicity should be more explored, to better understand the pathogenesis of the infections caused by the C. parapsilosis species complex. Finally, we have demonstrated that a combination of molecular mechanisms, including the overexpression of ERG11, and genes encoding efflux pumps are involved in azole resistance in C. parapsilosis. However, it is likely that the presence of point mutations in the ERG11 gene or additional mutations in transcription factors, or other mechanisms still unknown, probably exist in ours strains of C. parapsilosis.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research.

Funding

NA.

Availability of data and materials

All data are available.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: SN, IH. Performed the experiments: SN, IH. Analyzed the data: SN, IH, HT. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: SA, HS, FM & AA. Wrote the paper: SN, IH, HT. Involved in clinical management and provided clinical details: SN, HT, FC, HS, FM & AA. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

NA.

Consent for publication

NA.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sourour Neji, Email: nejisourour@yahoo.fr.

Ines Hadrich, Phone: +216 74 247 130, Email: ineshadrich@yahoo.fr.

Houaida Trabelsi, Email: thouaida@yahoo.fr.

Salma Abbes, Email: sel_salma@yahoo.fr.

Fatma Cheikhrouhou, Email: fatima_cheikhrouhou@yahoo.fr.

Hayet Sellami, Email: hayetsellami1@gmail.com.

Fattouma Makni, Email: famakni@gmail.com.

Ali Ayadi, Email: ali.ayadi@rns.tn.

References

- 1.Abi-Chacra EA, Souza LO, Cruz LP, Braga-Silva LA, Goncalves DS, Sodre CL, Ribeiro MD, Seabra SH, Figueiredo-Carvalho MH, Barbedo LS, Zancope-Oliveira RM, Ziccardi M, Santos AL. Phenotypical properties associated with virulence from clinical isolates belonging to the Candida parapsilosis Complex. FEMS Yeast Res. 2013;13(8):831–848. doi: 10.1111/1567-1364.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aneeja K. Experiments in microbiology, plant pathology, tissue culture and mushroom cultivation, ed II edn New Age international Publishers, Delhi 1996.

- 3.Ataides FS, Costa CR, Souza LK, Fernandes O, Jesuino RS, Silva Mdo R. Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility profiles of Candida parapsilosis Complex species isolated from culture collection of clinical samples. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48(4):454–459. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0120-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkow EL, Manigaba K, Parker JE, Barker KS, Kelly SL, Rogers PD. Multidrug transporters and alterations in sterol biosynthesis contribute to azole antifungal resistance in Candida parapsilosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(10):5942–5950. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01358-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertini A, De Bernardis F, Hensgens LA, Sandini S, Senesi S, Tavanti A. Comparison of Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis adhesive properties and pathogenicity. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303(2):98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borghi E, Sciota R, Iatta R, Biassoni C, Montagna MT, Morace G. Characterization of Candida parapsilosis Complex strains isolated from invasive fungal infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30(11):1437–1441. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borst A, Fluit AC. High levels of hydrolytic enzymes secreted by Candida albicans isolates involved in respiratory infections. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52(Pt 11):971–974. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Branco J, Silva AP, Silva RM, Silva-Dias A, Pina-Vaz C, Butler G, Rodrigues AG, Miranda IM. Fluconazole and Voriconazole resistance in Candida parapsilosis is conferred by gain-of-function mutations in MRR1 transcription factor gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(10):6629–6633. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00842-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassone A, De Bernardis F, Pontieri E, Carruba G, Girmenia C, Martino P, Fernandez-Rodriguez M, Quindos G, Ponton J. Biotype diversity of Candida parapsilosis and its relationship to the clinical source and experimental pathogenicity. J Infect Dis. 1995;171(4):967–975. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen LM, Xu YH, Zhou CL, Zhao J, Li CY, Wang R. Overexpression of CDR1 and CDR2 genes plays an important role in fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans with G487T and T916C mutations. J Int Med Res. 2010;38(2):536–545. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen YC, Lin YH, Chen KW, Lii J, Teng HJ, Li SY. Molecular epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility of Candida parapsilosis Sensu stricto, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis in Taiwan. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;68(3):284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chin VK, Foong KJ, Maha A, Rusliza B, Norhafizah M, Ng KP, Chong P. P. candida albicans isolates from a Malaysian hospital exhibit more potent phospholipase and haemolysin activities than non-albicans Candida isolates. Trop Biomed. 2013;30(4):654–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.da Silva BV, Silva LB, de Oliveira DB, da Silva PR, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva LE, Silva-Vergara ML, Andrade AA. Species distribution, virulence factors, and antifungal susceptibility among Candida parapsilosis complex isolates recovered from clinical specimens. Mycopathologia. 2015;180(5–6):333–343. doi: 10.1007/s11046-015-9916-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Bernardis F, Mondello F, San Millan R, Ponton J, Cassone A. Biotyping and virulence properties of skin isolates of Candida parapsilosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(11):3481–3486. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3481-3486.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Toro M, Torres MJ, Maite R, Aznar J. Characterization of Candida parapsilosis Complex isolates. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(3):418–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deorukhkar SC, Saini S. Virulence factors attributed to pathogenicity of non albicans Candida species isolated from human immunodeficiency virus infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. Annals of pathology and Lab Med. 2015;2(2):62–66. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diekema DJ, Messer SA, Boyken LB, Hollis RJ, Kroeger J, Tendolkar S, Pfaller MA. In vitro activity of seven systemically active antifungal agents against a large global collection of rare Candida species as determined by CLSI broth microdilution methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3170–3177. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00942-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunkel N, Blass J, Rogers PD, Morschhauser J. Mutations in the multi-drug resistance regulator MRR1, followed by loss of heterozygosity, are the main cause of MDR1 overexpression in fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69(4):827–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frade JP, Warnock DW, Arthington-Skaggs BA. Rapid quantification of drug resistance gene expression in Candida albicans by reverse transcriptase LightCycler PCR and fluorescent probe hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(5):2085–2093. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.2085-2093.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franca EJ, Furlaneto-Maia L, Quesada RM, Favero D, Oliveira MT, Furlaneto MC. Haemolytic and proteinase activities in clinical isolates of Candida parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis with reference to the isolation anatomic site. Mycoses. 2011;54(4):e44–e51. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gacser A, Schafer W, Nosanchuk JS, Salomon S, Nosanchuk JD. Virulence of Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis in reconstituted human tissue models. Fungal Genet Biol. 2007;44(12):1336–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Effron G, Katiyar SK, Park S, Edlind TD, Perlin DSA. Naturally occurring proline-to-alanine amino acid change in Fks1p in Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis accounts for reduced echinocandin susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(7):2305–2312. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00262-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ge YP, Lu GX, Shen YN, Liu WD. In vitro evaluation of phospholipase, proteinase, and esterase activities of and Candida metapsilosis. Mycopathologia. 2011;172(6):429–438. doi: 10.1007/s11046-011-9440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomez-Lopez A, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Rodriguez D, Almirante B, Pahissa A, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Cuenca-Estrella M. Prevalence and susceptibility profile of Candida metapsilosis and Candida orthopsilosis: results from population-based surveillance of candidemia in Spain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(4):1506–1509. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01595-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grossman NT, Pham CD, Cleveland AA, Lockhart SR. Molecular mechanisms of fluconazole resistance in Candida parapsilosis isolates from a U.S. surveillance system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(2):1030–1037. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04613-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang C, Dong D, Yu B, Cai G, Wang X, Ji Y, Peng Y. Mechanisms of azole resistance in 52 clinical isolates of Candida tropicalis in China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(4):778–785. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lattif AA, Mukherjee PK, Chandra J, Roth MR, Welti R, Rouabhia M, Ghannoum MA. Lipidomics of Candida albicans biofilms reveals phase-dependent production of phospholipid molecular classes and role for lipid rafts in biofilm formation. Microbiology. 2011;157(Pt 11):3232–3242. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.051086-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lattif AA, Mukherjee PK, Chandra J, Swindell K, Lockhart SR, Diekema DJ, Pfaller MA, Ghannoum MA. Characterization of biofilms formed by Candida parapsilosis, C. metapsilosis, and C. orthopsilosis. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300(4):265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li QQ, Skinner J, Bennett JE. Evaluation of reference genes for real-time quantitative PCR studies in Candida glabrata following azole treatment. BMC Mol Biol. 2012;13:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-13-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linares CE, de Loreto ES, Silveira CP, Pozzatti P, Scheid LA, Santurio JM, Alves SH. Enzymatic and hemolytic activities of Candida dubliniensis strains. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2007;49(4):203–206. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652007000400001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo G, Samaranayake LP, Yau JY. Candida species exhibit differential in vitro hemolytic activities. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(8):2971–2974. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.8.2971-2974.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melo AS, Bizerra FC, Freymuller E, Arthington-Skaggs BA, Colombo AL. Biofilm production and evaluation of antifungal susceptibility amongst clinical Candida spp. isolates, including strains of the Candida Parapsilosis Complex. Med Mycol. 2011;49(3):253–262. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.530032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morschhauser J, Barker KS, Liu TT, Bla BWJ, Homayouni R, Rogers PD. The transcription factor Mrr1p controls expression of the MDR1 efflux pump and mediates multidrug resistance in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(11):e164. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nemeth T, Toth A, Szenzenstein J, Horvath P, Nosanchuk JD, Grozer Z, Toth R, Papp C, Hamari Z, Vagvolgyi C, Gacser A. Characterization of virulence properties in the C. parapsilosis Sensu Lato species. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orsi CF, Colombari B, Blasi E. Candida metapsilosis as the least virulent member of the 'C. parapsilosis' complex. Med Mycol. 2010;48(8):1024–1033. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.489233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pakshir K, Zomorodian K, Karamitalab M, Jafari M, Taraz H, Ebrahimi H. Phospholipase, esterase and hemolytic activities of Candida spp. isolated from onychomycosis and oral lichen planus lesions. J Mycol Med. 2013;23(2):113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park BJ, Arthington-Skaggs BA, Hajjeh RA, Iqbal N, Ciblak MA, Lee-Yang W, Hairston MD, Phelan M, Plikaytis BD, Sofair AN, Harrison LH, Fridkin SK, Warnock DW. Evaluation of amphotericin B interpretive breakpoints for Candida bloodstream isolates by correlation with therapeutic outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(4):1287–1292. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1287-1292.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfaller MA, Chaturvedi V, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, Holliday NM, Killian SB, Knapp CC, Messer SA, Miskou A, Ramani R. Comparison of the Sensititre YeastOne colorimetric antifungal panel with CLSI microdilution for antifungal susceptibility testing of the echinocandins against Candida spp., using new clinical breakpoints and epidemiological cutoff values. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;73(4):365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfaller MA, Chaturvedi V, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, Holliday NM, Killian SB, Knapp CC, Messer SA, Miskov A, Ramani R. Clinical evaluation of the Sensititre YeastOne colorimetric antifungal panel for antifungal susceptibility testing of the echinocandins anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(7):2155–2159. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00493-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price MF, Wilkinson ID, Gentry LO. Plate method for detection of phospholipase activity in Candida albicans. Sabouraudia. 1982;20(1):7–14. doi: 10.1080/00362178285380031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramesh N, Priyadharsini M, Sumathi CS, Balasubramanian V, Hemapriya J, Kannan R. Virulence factors and anti fungal sensitivity pattern of Candida Sp. isolated from HIV and TB patients. Indian J Microbiol. 2011;51(3):273–278. doi: 10.1007/s12088-011-0177-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramos Lde S, Barbedo LS, Braga-Silva LA. Dos Santos a.L., pinto M.R. And Sgarbi D.B. Protease and phospholipase activities of Candida spp. isolated from cutaneous candidiasis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2015;32(2):122–125. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruiz LS, Khouri S, Hahn RC, da Silva EG, de Oliveira VK, Gandra RF, Paula CR. Candidemia by species of the Candida parapsilosis Complex in children's hospital: prevalence, biofilm production and antifungal susceptibility. Mycopathologia. 2013;175(3–4):231–239. doi: 10.1007/s11046-013-9616-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sabino R, Sampaio P, Carneiro C, Rosado L, Pais C. Isolates from hospital environments are the most virulent of the Candida parapsilosis Complex. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sachin CD, Ruchi K, Santosh S. In vitro evaluation of proteinase, phospholipase and haemolysin activities of Candida species isolated from clinical specimens. Int J Med Biomed Res. 2012;1(2):153–157. doi: 10.14194/ijmbr.1211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B, Fiori B, Ranno S, Torelli R, Fadda G. Mechanisms of azole resistance in clinical isolates of Candida glabrata collected during a hospital survey of antifungal resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(2):668–679. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.668-679.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schaller M, Borelli C, Korting HC, Hube B. Hydrolytic enzymes as virulence factors of Candida albicans. Mycoses. 2005;48(6):365–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2005.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silva AP, Miranda IM, Guida A, Synnott J, Rocha R, Silva R, Amorim A, Pina-Vaz C, Butler G, Rodrigues AG. Transcriptional profiling of azole-resistant Candida parapsilosis strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(7):3546–3556. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01127-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silva AP, Miranda IM, Lisboa C, Pina-Vaz C, Rodrigues AG. Prevalence, distribution, and antifungal susceptibility profiles of Candida parapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, and C. metapsilosis in a tertiary care hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(8):2392–2397. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02379-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silva S, Henriques M, Martins A, Oliveira R, Williams D, Azeredo J. Biofilms of non-Candida albicans Candida species: quantification, structure and matrix composition. Med Mycol. 2009;47(7):681–689. doi: 10.3109/13693780802549594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song JW, Shin JH, Shint DH, Jung SI, Cho D, Kee SJ, Shin MG, Suh SP, Ryang DW. Differences in biofilm production by three genotypes of Candida parapsilosis from clinical sources. Med Mycol. 2005;43(7):657–661. doi: 10.1080/13693780500294915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Souza AC, Fuchs BB, Pinhati HM, Siqueira RA, Hagen F, Meis JF, Mylonakis E, Colombo A. L. candida parapsilosis resistance to fluconazole: molecular mechanisms and in vivo impact in infected galleria mellonella larvae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(10):6581–6587. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01177-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szabo Z, Szilagyi J, Tavanti A, Kardos G, Rozgonyi F, Bayegan S, Majoros L. In vitro efficacy of 5 antifungal agents against , Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis as determined by time-kill methodology. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;64(3):283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tavanti A, Davidson AD, Gow NA, Maiden MC, Odds F. C. candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis spp. nov. to replace Candida Parapsilosis groups II and III. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(1):284–292. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.284-292.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tavanti A, Hensgens LA, Mogavero S, Majoros L, Senesi S, Campa M. Genotypic and phenotypic properties of Candida parapsilosis Sensu strictu strains isolated from different geographic regions and body sites. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:203. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tosun I, Akyuz Z, Guler NC, Gulmez D, Bayramoglu G, Kaklikkaya N, Arikan-Akdagli S, Aydin F. Distribution, virulence attributes and antifungal susceptibility patterns of Candida parapsilosis Complex strains isolated from clinical samples. Med Mycol. 2013;51(5):483–492. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.745953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trabasso P, Matsuzawa T, Fagnani R, Muraosa Y, Tominaga K, Resende MR, Kamei K, Mikami Y, Schreiber AZ, Moretti ML. Isolation and drug susceptibility of Candida parapsilosis Sensu Lato and other species of C. parapsilosis Complex from patients with blood stream infections and proposal of a novel LAMP identification method for the species. Mycopathologia. 2015;179(1–2):53–62. doi: 10.1007/s11046-014-9830-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trevino-Rangel Rde J, Garza-Gonzalez E, Gonzalez JG, Bocanegra-Garcia V, Llaca JM, Gonzalez GM. Molecular characterization and antifungal susceptibility of the Candida parapsilosis species complex of clinical isolates from Monterrey, Mexico. Med Mycol. 2012;50(7):781–784. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.675526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trevino-Rangel Rde J, Gonzalez JG, Gonzalez GM. Aspartyl proteinase, phospholipase, esterase and hemolysin activities of clinical isolates of the Candida parapsilosis species complex. Med Mycol. 2013;51(3):331–335. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.712724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tumbarello M, Posteraro B, Trecarichi EM, Fiori B, Rossi M, Porta R, de Gaetano Donati K, La Sorda M, Spanu T, Fadda G, Cauda R, Sanguinetti M. Biofilm production by Candida species and inadequate antifungal therapy as predictors of mortality for patients with candidemia. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(6):1843–1850. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00131-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]