Abstract

Background

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) are comorbid and associated with similar neural disruptions during emotion regulation (Blair et al., 2012). In contrast, the lack of optimism examined here may occur specifically in GAD and could prove an important biomarker for that disorder.

Methods

Un-medicated individuals with GAD (n=18) and age, IQ and gender-matched SAD (n=18) and healthy (n=18) comparison individuals were scanned while contemplating likelihoods of high and low impact negative (e.g., having heart attack; getting heartburn) or positive (e.g., winning the lottery; getting a hug) events occurring to themselves in the future.

Results

In line with previous work, healthy subjects showed significant optimistic bias (OB); they considered themselves significantly less likely to experience future negative but significantly more likely to experience future positive events relative to others. This was also seen in SAD. However, GAD patients showed no OB for positive events and at the neural level showed significantly reduced modulation relative to the two other groups of regions including medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and caudate to these events. The GAD group further differed from the other groups by showing increased neural responses to low impact events in regions including rostral mPFC.

Conclusions

The form of neural dysfunction identified here may represent a unique feature associated with reduced optimism and increased worry about everyday events that occurs in GAD. Consistent with this possibility, patients with SAD did not show such dysfunction. Future studies should consider if this dysfunction represents an important biomarker for GAD.

Keywords: fMRI, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, optimism, worry, medial prefrontal cortex

INTRODUCTION

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) are two frequently comorbid conditions (Craske et al., 2009). GAD involves excessive worry, whereas SAD involves anxiety to social situations. Some work finds similar neural correlates in the two disorders (e.g., Martin et al., 2010) including similarly reduced capacity for engaging emotion regulation networks (Blair et al., 2012). Moreover, other studies fail to distinguish the two disorders, combining them into one mixed anxiety group (Britton et al., 2013, Campbell-Sills et al., 2011, Krain et al., 2008). However, different clinical presentations and possible disorder-specific treatments suggest the need to further evaluate possible disorder-specific neural underpinnings. Pathological worry is the defining feature of GAD. Thus, in this paper we consider whether neural disruptions during worry-related processing may be specific to GAD, and not SAD.

Few studies map the neuro-cognitive correlates of worry, complicating attempts to delineate the specific neural dysfunctions in GAD. However, work has mapped the neuro-computational correlates of processes that might arguably be viewed as the counterpoint to worry: optimism and optimistic bias (OB) (Blair et al., 2013, Sharot et al., 2011, Sharot et al., 2007). OB is the belief that negative events are less likely, and positive events more likely, to happen to oneself than to others (Weinstein, 1980). Healthy adults typically exhibit this bias, but it is reduced in patients with depression (Strunk et al., 2006) and anxiety (Helweg-Larsen and Shepperd, 2001). Nevertheless, no prior study contrasts OB in different types of anxiety. Given that enhanced worry and reduced OB both relate to perturbed processing of future events, it seems plausible that GAD involves a reduced OB relative to healthy individuals and individuals with SAD.

Studies of the neural systems mediating OB reveal three important components, each of which might be dysfunctional in GAD (Blair et al., 2013, Sharot et al., 2012, Sharot et al., 2011, Sharot et al., 2007). First, rostral medial prefrontal cortex (rmPFC) tracks the perceived positive difference between the probability of the event occurring to the self versus others (Blair et al., 2013, Sharot et al., 2011). Second, the inferior frontal cortex (IFC)/insula tracks perceived negative difference between the probability of the event occurring to the self versus others (Blair et al., 2013, Sharot et al., 2012, Sharot et al., 2011). Third, ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) represents the subjective value of the future event; the more positive an event’s subjective value, the greater the activity in this region (Blair et al., 2013, Sharot et al., 2007). Previous work has implicated these areas in GAD, with mPFC dysfunction shown during processes related to attention (Blair et al., 2012, Etkin et al., 2010), worry (Paulesu et al., 2010), and anticipation (Nitschke et al., 2009, Whalen et al., 2008). Similarly, heightened responses in IFC/insula manifest in response to emotional stimuli in pediatric anxiety-disorder patients, relative to healthy peers (McClure et al., 2007, Monk et al., 2006). Finally, vmPFC dysfunction is observed in GAD in the context of emotional conflict adaptation (Etkin et al., 2010, Etkin and Schatzberg, 2011) and passive avoidance learning (White et al., under revision).

This supports three specific hypotheses for GAD on our task indexing OB-related processing. Data from two comparison groups was collected: healthy individuals and patients with SAD. Patients with SAD were chosen as a high level comparison because although they show high levels of (social) anxiety, there are no clear indications that they show a reduced OB or increased worry. Moreover, they show comparable levels of depression symptomatology to patients with GAD. As such the inclusion of this population serves to either support, or refute, claims of specificity in any observed dysfunction. Relative to these groups, healthy individuals and patients with SAD, patients with GAD were hypothesized to show: (i) decreased modulation of rmPFC as a function of OB to positive events; (ii) decreased modulation of insula/IFG as a function of decreased OB to negative events; and (iii) reduced responses within vmPFC to positive future events. In addition, it is hypothesized that relative to the comparison groups, patients with GAD could show a particularly increased response to events considered to have low (e.g., getting sunburn) relative to high (e.g., having a heart attack) impact given the preoccupation with everyday worries in that population. The current study tests these predictions.

METHODS AND MATRIALS

Subjects

Three different patient groups participated: patients with GAD only (n=18), patients with generalized SAD only (n=18) and healthy comparison (HC) individuals (n=18). Data from this last group were a subset of subjects included in another study (Blair et al., 2013). Subjects were matched group-wise on age, gender and IQ (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics: S.D. in Brackets ().

| GAD(BR/)N = 18 | SAD(BR/)N = 18 | HC(BR/)N = 18 | P< | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE | 31.0 (7.78) | 32.4 (9.48) | 31.9 (7.78) | NS |

| GENDER | 8 F/10 M | 13 F/5 M | 10 F/8 M | NS |

| IQ | 117.5 (12.59) | 112.9 (11.73) | 114.8 (12.59) | NS |

| LSAS-SR | 41.1 (19.07) | 70.3 (27.33) | 20.8 (13.80) | 0.001 |

| BAI | 12.7 (7.32) | 5.4 (4.24) | 2.1 (2.38) | 0.001 |

| STAI-T | 47.3 (6.53) | 42.7 (10.18) | – | NS |

| PSWQ | 65.6 (6.72) | 42.6 (12.58) | – | 0.001 |

| IDS | 17.9 (6.79) | 14.1 (8.34) | – | NS |

Key to Table 1: M = Male; F = Female; LSAS = Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale-Self Rated; BAI = Beck’s Anxiety Inventory; STAI-T = The Spielberger Trait-State Inventory – Part Trait; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; IDS = Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology

We explicitly recruited subjects who suffered from two specific types of anxiety to facilitate direct comparisons among groups. Accordingly, patients with GAD could only meet criteria for GAD, and patients with SAD could only met criteria for SAD, based on the Structural Clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID) (First et al., 1997) and a confirmatory clinical interview by a board certified psychiatrist (DSP). All were medication-free for at least six months. Given the association with depression and both GAD and OB, patients with current MDD were excluded from the study. HCs had no psychiatric illness. All subjects were in good physical health.

Optimistic Bias (OB) Task (Blair et al., 2013)

The stimuli consisted of 160 possible future events involving different levels (high vs. low) of impact on an individual’s life. Events consisted of 40 high impact negative (e.g., having a heart attack), 40 low impact negative (e.g., getting sunburn), 40 high impact positive (e.g., winning the lottery) and 40 low impact positive (e.g., getting a hug) events. The stimuli were selected from a larger set of stimuli rated according to pleasantness/unpleasantness by a different group of 35 healthy adults. The high impact negative and positive events and low impact negative and positive events were matched according to their relative valence. In addition, the four different event types were matched on number of letters and words.

Subjects read different possible future events and rated the likely probability of the event happening to them across their lifetime, compared to other people of same gender and age. They rated their likelihood according to a 4 point scale where 1=much below average; 2=below average; 3=above average; or 4=much above average, using the second and third digit of both hands. Each event was presented for 5500ms following a 500ms fixation point. In addition, for each experimental run, 48 3000ms fixation points were presented (8 at beginning and end of the run and 40 presented randomly throughout to be used as an implicit baseline). The fMRI scan acquisition followed an event-related design, and consisted of four runs with 40 trials per run.

MRI parameters and imaging data preprocessing

Whole-brain blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) fMRI data were acquired using a 1.5 Tesla GE MRI scanner. Following sagittal localization, functional T2* weighted images were acquired using an echo-planar single-shot gradient echo pulse sequence (matrix=64×64mm3, repetition time (TR)=3000ms, echo time (TE)=30ms, field-of-view (FOV)=240mm3 (3.75×3.75×4 mm3 voxels). Images were acquired in 31 contiguous 4mm axial slices per brain volume, with each run lasting 6 minutes 24 seconds. In the same session, a high-resolution T1-weighed anatomical image was acquired to aid with spatial normalization (three-dimensional Spoiled GRASS; TR=8.1ms; TE=3.2ms, flip angle=20°; FOV=240mm3, 124 axial slices, thickness=1.0 mm; 256×256 acquisition matrix).

Data were analyzed within the framework of the general linear model using Analysis of Functional Neuroimages (AFNI) (Cox, 1996). Both individual and group-level analyses were conducted. The first four volumes in each scan series, collected before equilibrium magnetization was reached, were discarded. Motion correction was performed by registering all volumes in the EPI dataset to a volume collected close to acquisition of the high-resolution anatomical dataset.

The EPI datasets for each subject were spatially smoothed (isotropic 6mm3 kernel) to reduce variability among individuals and generate group maps. Next, the time series data were normalized by dividing the signal intensity of a voxel at each time point by the mean signal intensity of that voxel for each run and multiplying the result by 100, producing regression coefficients representing percent-signal change.

Two sets of regressors were then generated. Set one involved indicator functions for high impact negative, low impact negative, high impact positive, and low impact positive events multiplied by the subject’s rating of each event likelihood. These regressors were created by convolving the train of stimulus events with a gamma-variate hemodynamic response function to account for the slow hemodynamic response. Set two involved indicator functions for high impact negative, low impact negative, high impact positive and low impact positive events. In other terms, the first set regressors modeled the deviation from the average response explained by the subject’s rating of event likelihood (modulated), and the second set modeled (un-modulated) average response to each of the four categories. Linear regression modeling was performed using the 8 regressors described above plus 6 head motion regressors. This produced an un-modulated and modulated b coefficient and associated t statistic for each voxel and regressor. There was no significant collinearity between the regressors as detected by AFNI. Voxel-wise group analyses involved transforming single subject beta coefficients into standard coordinate space (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988).

fMRI and behavioral data analysis

Following Blair et al. (Blair et al., 2013) three analyses were performed on the regression coefficients from the individual subject analyses. The first and second analyses used the subject-specific modulated regressors for positive and negative events, respectively. Thus, the first analysis examined group differences in the averaged response to positive future events modulated by the subject’s estimate of each individual event’s likelihood and involved a 3(Group: GAD, SAD, HC) ANOVA. Conversely, the second analysis examined group differences in the averaged response to negative future events modulated by the subject’s estimate of each individual event’s likelihood and involved a 3 (Group: GAD, SAD, HC) ANOVA.

The third analysis examined BOLD responses to the un-modulated regressors and involved a 3(Group: GAD, SAD, HC) by 2(Emotion: Negative, Positive) by 2(Impact: High, Low) ANOVA. This same model was also used to analyse the behavioural data. The aim of this third analysis was to determine whether patients with GAD would show reduced responses to positive events, irrespective of the subject’s ratings of probability of these events, within the vmPFC. A secondary goal was to determine whether the different levels of impact might differentially modulate the groups’ neural responses.

Statistical maps were created for each analysis by thresholding at a single-voxel p value of p<0.005. To correct for multiple comparisons, we performed a spatial clustering operation using ClustSim with 1,000 Monte Carlo simulations taking into account the EPI matrix covering the entire brain. This procedure yielded a minimum cluster size of 952 mm3 (16.92 voxels) with a map-wise false-positive probability of p<0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons.

After observing hypothesized group differences, post-hoc analyses were performed to determine the source of significant interactions. For these analyses, average percent signal change was taken from all voxels within each ROI generated from the functional mask, and appropriate t-tests carried out within SPSS to pinpoint the nature of interaction effects.

RESULTS

Behavioral Results

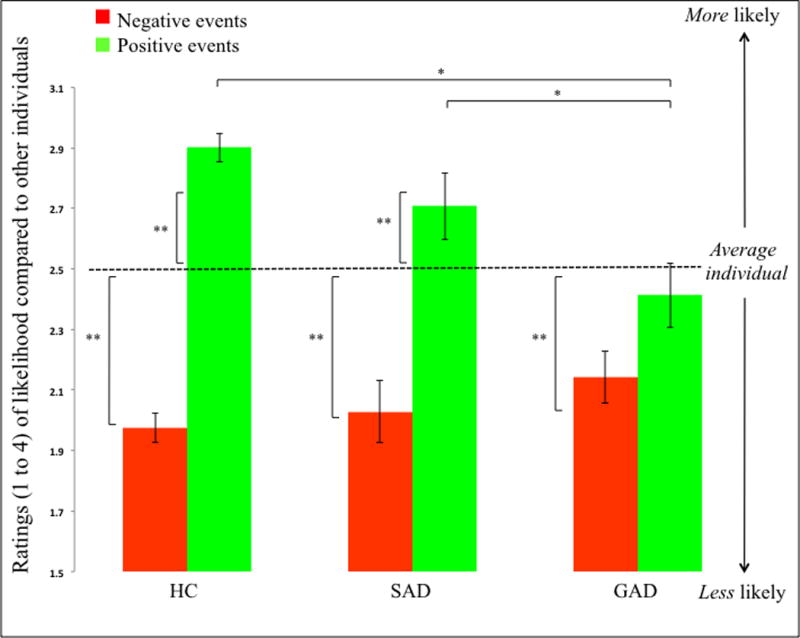

The results from the 3(Group: GAD, SAD, HC) by 2(Emotion: Negative, Positive) by 2(Impact: High, Low) ANOVA revealed a significant group-by-emotion interaction (F=7.69; p<0.001); Figure 1. The three groups rated their likelihood of experiencing negative events similarly low (F=1.07; ns). However, they differed significantly in their ratings of the likelihood of positive events happening in the future (F=7.11; p<0.005) with the GAD group rating their likelihood of experiencing positive events significantly lower than both the HC and SAD groups (GAD vs. HC, GAD vs. SAD; F=3.75 & 2.26; p<0.001 & 0.05 respectively) who did not differ significantly (SAD vs. HC; F=1.49; ns). In line with this, follow-up t-test using the 2.5 midpoint on our 4-point likelihood rating scale as reference point, showed that all three groups showed OB for negative events (HC: t[17]=10.91; p<0.001; SAD: t[17]=4.59; p<0.001;GAD: t[17]=4.11; p<0.001). However, only HCs and patients with SAD (albeit at trend levels) showed an OB for positive events (HC: t[17]=8.66; p<0.001; SAD: t[17]=1.89; p<0.10; GAD: (t[17]=0.82; n.s.).

Figure 1. Behavioral ratings.

All patients groups showed significant OB for negative events, however, only the SAD and HC groups showed significant OB for positive events. S.E. shown in graph. * signifies a significant group difference. ** signifies a significant difference in rating relative to the 2.5 rating of the average individual.

The multi-factorial ANOVA also showed main effects of emotion and impact (F=79.48 & 152.42; p<0.001); subjects thought they were more likely to experience positive and low impact, relative to negative and high impact, events. No other interactions were significant.

The RT data showed no significant main effect of group or significant interactions. There was however a significant main effect of emotion; subjects took longer rating likelihoods of negative, relative to positive events (F=33.40; p<0.001).

fMRI Results

Modulated Data (BOLD Responses Modulated by OB)

The initial analyses identified brain regions where there were group differences in the variation of activity as a function of subjects’ event-probability estimates for specific events. In other words, these were regions specifically showing group differences in neural regions supporting individual variability in OB. Following Blair et al. (Blair et al., 2013), for this purpose, in two sets of analyses, we considered the modulated regressors for the positive and negative events, respectively, each considered against baseline. Our goals in these analyses were to determine whether the GAD group would show, relative to the HC and SAD comparison groups: (i) reduced rmPFC recruitment as a function of OB for potential future positive events; and/or (ii) decreased IFC/insula recruitment as a function of OB for potential future negative events.

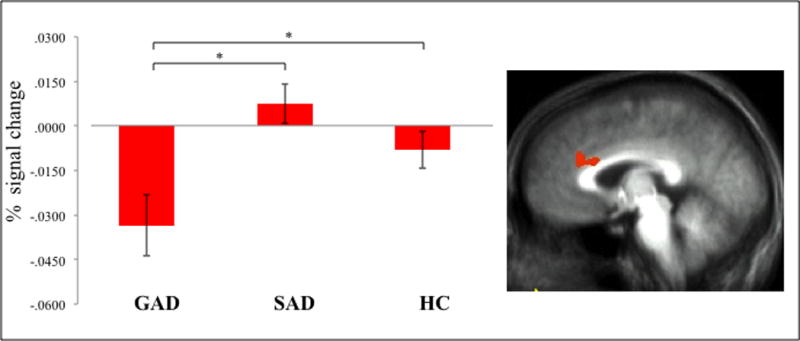

As can be seen in Table 2, there were significant group differences in the correlation of activity within several regions including anterior and more posterior regions of medial frontal cortex and bilateral caudate and subjects’ estimates of the likelihood estimates for positive events. In all regions and shown for mPFC in Figure 2, the GAD group showed significantly greater inverse modulation by their probability estimates for positive events than both the HC (F range=3.49 to 11.46; p<0.01 to 0.001) and SAD (F range=17.26 to 34.71; p<0.001) groups. In other words, in patients with GAD, activity in these regions increased the less likely that they thought the event would occur to themselves relative to other individuals. No area survived correction for multiple comparisons in the analysis involving negative events.

Table 2.

Significant areas of activation from the analyses involving the modulated BOLD responses according to the individual subject probability estimates for positive events, and the un-modulated BOLD responses

| REGION | BA | Mm3 | X | Y | Z | F-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modulated BOLD response: Group main effect† | ||||||

| R mPFC | 24 | 1103 | 12 | 4 | 30 | 14.44 |

| L caudate/lentiform nucleus | 1673 | −15 | 7 | 7 | 18.04 | |

| R caudate* | 140 | 17 | 14 | 12 | 14.34 | |

| R middle frontal gyrus | 6 | 2882 | 38 | 2 | 53 | 22.44 |

| L thalamus | 6805 | −6 | −12 | 7 | 15.89 | |

| R superior temporal gyrus | 41 | 3313 | 41 | −33 | 15 | 19.99 |

| Un-modulated BOLD response: Group-by-impact interaction†† | ||||||

| R rmMPFC | 32/9 | 3144 | 15 | 33 | 28 | 10.82 |

| R IFG/insula | 46 | 1206 | 37 | 32 | 6 | 8.212 |

| L middle frontal gyrus | 1867 | −31 | 15 | 25 | 13.62 | |

| R superior frontal gyrus | 8/32 | 1222 | 22 | 28 | 48 | 10.62 |

| R lentiform nucleus/putamen | 2866 | 24 | −7 | 12 | 17.02 | |

| R superior temporal gyrus | 39 | 1492 | 39 | −53 | 24 | 12.04 |

| L supramarginal gyrus | 40 | 1076 | −50 | −54 | 29 | 11.50 |

Activations are effects observed in whole brain analyses significant at

p<0.001 and

significant at 0.005, corrected for multiple comparisons (significant at p<0.05).

Significant at 0.05, corrected for small volume

Figure 2. Modulated BOLD response.

Reduced modulation by OB in the patients with GAD for potential future positive events in right mPFC (12, 4, 30). * signifies a significant group difference.

Un-modulated Data

Following this initial analysis on the modulated BOLD responses, a whole-brain 3(Group: GAD, SAD, HC) by 2(Emotion: Negative, Positive) by 2(Impact: High, Low) ANOVA was conducted on the subjects’ BOLD responses to the events (un-modulated by their probability estimates). The purpose of this analysis was to determine whether patients with GAD would show reduced responses to positive events within vmPFC. However, there was no significant group-by-emotion (or group-by-emotion-by-impact) interaction within vmPFC. In contrast, there was a highly significant main effect of emotion: all three groups showed greater responses to positive relative to negative events within vmPFC and posterior cingulate cortex.

Several regions including the rmPFC showed significant group-by-impact interactions however; Table 2 and Figure 3. In all regions, the GAD group showed significantly increased activation when processing low relative to high impact events compared to the HC (F range=13.98 to 29.07; p<0.001 for all) and SAD (F range=5.01 to 27.44; p range=0.05 to 0.001) groups. Moreover, within right rmPFC and IFG (Fig. 3), the GAD group showed significantly reduced responses to high impact events relative to the SAD and HC groups (t=2.35 to 2.07; p<0.05).

Figure 3. Un-modulated group-by-impact interaction.

Increased BOLD responses to low impact events in patients with GAD in (a) right rmPFC (15, 33, 28) and (b) right IFG (37, 32, 6). * signifies a significant group difference.

DISCUSSION

The goal of the current study was to determine whether patients with GAD show reduced OB, and if so, identify the associated neural correlates. There were three main findings, as well as a number of other, less-notable results. First, behaviorally, patients with GAD failed to show OB to positive events, although they showed OB to negative events. Second, for modulated data, there were significant, selective group differences in response to future positive events. Specifically, patients with GAD showed reduced modulation of mPFC activity as a function of perceived probability of future positive events occurring to them, but there was no significant group difference in the modulated response to future negative events. Third, for un-modulated data, the GAD group also showed significantly reduced activity relative to the HC and SAD groups when processing high impact events within rmPFC.

Previous work has reported reduced OB in patients with depression (Strunk et al., 2006) and in healthy individuals with raised anxiety (Helweg-Larsen and Shepperd, 2001). Here, while all three groups showed comparable OB for negative events, the patients with GAD showed a significantly reduced OB for positive events relative to the SAD and HC groups. Critically, this is the first study to directly examine the neural basis of OB in patients with GAD and SAD. On the basis of previous work involving optimism/OB (Blair et al., 2013, Sharot et al., 2012, Sharot et al., 2011, Sharot et al., 2007), we hypothesized that up to three potential computational processes might be disrupted in patients with GAD.

First, we hypothesized that patients with GAD might show decreased modulation of rmPFC as a function of OB to positive events. Partly consistent with predictions there were significant group differences in a rostral region of dorsal medial frontal cortex (dmPFC). Previous studies involving GAD have reported impaired functioning within mPFC (Blair et al., 2012, Etkin et al., 2010, Paulesu et al., 2010) and that poorer responsiveness there predicts a poorer treatment response (Nitschke et al., 2009, Whalen et al., 2008). In previous work with the current task, involving many of the healthy individuals reported here, a proximal region of rmPFC showed increased activity as perceived likelihood increased (Blair et al., 2013). Indeed, within the region identified in this earlier study, patients with SAD, but not patients with GAD, also showed significantly increased activity when thinking the event was more likely to occur to themselves than to others (data not shown here). However, it is worth noting that: (i) there were group differences in modulation as a function of OB in regions other than mPFC including bilateral caudate and thalamus; (ii) in all regions, including mPFC, the group differences were driven by the GAD patients showing increasing activity as perceived likelihood decreased (i.e., decreasing activity as they thought that positive events were more likely to occur to themselves than others); (iii) in all regions, apart from temporal cortex, healthy individuals showed no significant modulation. These findings were unpredicted. We had anticipated that the GAD group would show a weaker modulated response than the HC and SAD groups. As such, they are difficult to interpret though it does appear that patients with GAD process the likelihood that positive events will occur to themselves in the future fundamentally differently from comparison individuals.

Second, we hypothesized that patients with GAD might show reduced optimism for negative events (i.e., a reduced bias to consider negative events as less likely to occur to the self than others) relating to atypical responding when judging future negative events within IFC/insula. This region and, to a certain extent dmPFC, is consistently implicated in the anticipatory response to impending negative events (Knutson and Greer, 2008, Knutson et al., 2007), and choosing actions to avoid negative consequences (Budhani et al., 2007, Kuhnen and Knutson, 2005, Liu et al., 2007). However, the patients with GAD showed no impairment in this regard. IFC/insula and dmPFC respond similarly to estimates of increasing likelihood that a negative event will happen to the self relative to others, in patients with GAD, healthy comparison individuals and patients with SAD.

Third, we hypothesized that patients with GAD might show reduced differentiation of positive relative to negative events within vmPFC. However, the current study did not find evidence of such impairment. Prior research implicates this region in the representation of subjective value of stimuli (e.g., Ballard and Knutson, 2009, Blair et al., 2006, Levy and Glimcher, 2011), with increasing responses within this region for positive relative to negative stimuli. Given this past work and the current findings on vmPFC function, data may suggest preserved vmPFC function in GAD, at least for representing subjective value for the types of events examined in the current study.

We also hypothesized that relative to the comparison groups, the GAD group could show a particularly increased response to events considered to have low (e.g., getting sunburn) relative to high (e.g., having a heart attack) impact given the preoccupation with everyday worries in that population. Partly in line with predictions, there were group-by-impact interactions within bilateral rmPFC, right IFG/anterior insula cortex, bilateral lateral frontal cortex and a large region of basal ganglia. In all these regions, patients with GAD were showing significantly greater increase in activity for low relative to high positive and negative impact events than the comparison groups. In short, the current study revealed not only notably different responding in patients with GAD relative to comparison groups relating to estimates of the difference between the subject’s probability estimate for a positive event occurring to the self relative to another individual in mPFC but also notably different responding of a proximal region of rmPFC in response to low impact future events. Previous studies have also reported pathophysiology within this region in patients with GAD (Blair et al., 2012, Etkin et al., 2010, Nitschke et al., 2009, Paulesu et al., 2010, Whalen et al., 2008). From a functional perspective, mPFC has been implicated in responding to conflict (e.g., Kerns et al., 2004) and increased choice availability (Alexander and Brown, 2011). There are also suggestions that progressively more rostral regions become involved in these processes as the stimuli generating choice became increasingly abstract (Kim et al., 2011). In addition, rmPFC has been implicated in self-referential processing (Blair et al., 2010, Blair et al., 2011). As such, it can be speculated that the increased activity in rmPFC might represent the greater relevance of low impact items to these individuals given their presentation of preoccupation with everyday worries. While the computational specifics of the observed dysfunction remain unclear, it does appear that patients with GAD process low relative to high impact items fundamentally differently from comparison individuals.

Five caveats should be noted in relation to the current study. First, while comparable to many other studies involving GAD and in line with our power analysis, our sample sizes (N=18 per group) were only moderate. Second, the 4-point scale used in the current study did not allow for a rating of “average”. Rather the subjects had to rate the likelihood of an event happening either ”below” (slightly or much) or “above” (slightly or much) average. This manipulation was purposeful, attempting to minimize the potential for disengagement through overuse of neutral “average” answers, however, it likely sometimes forced a “below” or “above” decision where the likelihood truly was believed to be “average’. Third, patients were excluded if, in addition to their disorder, they presented with common comorbidities, including other anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, or depression. Our goal was to determine the pathophysiology of GAD and the comparison anxiety disorder SAD, in a dataset where results could not be attributed to the presence of comorbid conditions. However, this means that the patients studied were atypical to many anxiety patients presenting clinically and future research may want to determine the extent to which the current findings apply to patients with significant co-morbidity. Fourth, it could be argued that the SAD patients were less anxious than the GAD patients. They did report less anxiety on the Beck’s Anxiety Inventory and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. However, they reported significant more anxiety on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale and there were no group differences on either the Spielberger Trait-State Inventory or the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology. As such, we would argue that they were not less anxious but, consistent with diagnosis, differentially anxious. Moreover, importantly, the lack of significant group differences on the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology indicates that the results reported here could not primarily relate to differences in depression level. Fifth, it is worth noting that the current stimuli set were developed to examine OB generally rather than with respect to specific concerns for specific patient groups. It is possible that the behavioral effects might have been stronger if they had been more directly related to symptom domains.

In conclusion, the current study identifies two atypical neural responses in patients with GAD when: (i) representing the likelihood of a positive event occurring to the self relative to others (implicating mPFC, bilateral caudate and thalamus); and (ii) responding to low relative to high impact events (implicating bilateral rmPFC, right IFG/anterior insula cortex, bilateral lateral frontal cortex and a large region of basal ganglia). In contrast, two neural responses that were not atypical concerned: (i) representing the subjective value of positive relative to negative events (implicating vmPFC); and (ii) representing the likelihood of a negative event occurring to the self relative to others (implicating dmPFC and IFC/insula). Notably, these findings were specific for GAD. Patients with SAD showed no significant differences in behavioral or neural responses relative to healthy adults. As such, the current data indicate at least some disorder-specificity for the rmPFC dysfunction shown by patients with GAD during the contemplation of potential future events.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Mental Health. The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report. Further, the authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Footnotes

Supplemental information: No

References

- Alexander WH, Brown JW. Medial prefrontal cortex as an action-outcome predictor. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1338–44. doi: 10.1038/nn.2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard K, Knutson B. Dissociable neural representations of future reward magnitude and delay during temporal discounting. Neuroimage. 2009;45:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KS, Geraci M, Hollon N, Otero M, DeVido J, Majestic C, Jacobs M, Blair RJ, Pine DS. Social norm processing in adult social phobia: atypically increased ventromedial frontal cortex responsiveness to unintentional (embarrassing) transgressions. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1526–32. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KS, Geraci M, Otero M, Majestic C, Odenheimer S, Jacobs M, Blair RJ, Pine DS. Atypical modulation of medial prefrontal cortex to self-referential comments in generalized social phobia. Psychiatry Res. 2011;193:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KS, Geraci M, Smith BW, Hollon N, Devido J, Otero M, Blair JR, Pine DS. Reduced dorsal anterior cingulate cortical activity during emotional regulation and top-down attentional control in generalized social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and comorbid generalized social phobia/generalized anxiety disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:476–82. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KS, Marsh AA, Morton J, Vythilingham M, Jones M, Mondillo K, Pine DS, Drevets WC, Blair RJR. Choosing the lesser of two evils, the better of two goods: Specifying the roles of ventromedial prefrontal cortex and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex in object choice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:11379–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1640-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KS, Otero M, Teng C, Jacobs M, Odenheimer S, Pine DS, Blair RJ. Dissociable Roles of Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex (vmPFC) and Rostral Anterior Cingulate Cortex (rACC) in Value Representation and Optimistic Bias. Neuroimage. 2013;78:103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JC, Grillon C, Lissek S, Norcross MA, Szuhayny KL, Chen G, Ernst M, Nelson EE, Leibenluft MD, Shechner T, Pine DS. Response to Learned Threat: An fMRI Study in Adolescent and Adult Anxiety. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170:1195–1204. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12050651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budhani S, Marsh AA, Pine DS, Blair RJR. Neural correlates of response reversal: Considering acquisition. Neuroimage. 2007;34:1754–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Simmons AN, Lovero KL, Rochlin AA, Paulus MP, Stein MB. Functioning of neural systems supporting emotion regulation in anxiety-prone individuals. Neuroimage. 2011;54:689–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and Biomedical Research. 1996;29:162–73. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Rauch SL, Ursano R, Prenoveau J, Pine DS, Zinbarg RE. What is an anxiety disorder? Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:1066–85. doi: 10.1002/da.20633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Prater KE, Hoeft F, Menon V, Schatzberg AF. Failure of anterior cingulate activation and connectivity with the amygdala during implicit regulation of emotional processing in generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:545–54. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09070931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Schatzberg AF. Common abnormalities and disorder-specific compensation during implicit regulation of emotional processing in generalized anxiety and major depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:968–78. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10091290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Helweg-Larsen M, Shepperd JA. Do moderators of the optimistic bias affect personal or target risk estimates? A review of the literature. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2001;5:74–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns JG, Cohen JD, MacDonald AW, Cho RY, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Anterior cingulate confict monitoring and adjustments in control. Science. 2004;303:1023–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1089910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Johnson NF, Cilles SE, Gold BT. Common and distinct mechanisms of cognitive flexibility in prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4771–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5923-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Greer SM. Anticipatory affect: neural correlates and consequences for choice. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;353:3771–3786. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Rick S, Wimmer GE, Prelec D, Loewenstein G. Neural predictors of purchases. Neuron. 2007;53:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krain A, Gotimer K, Hefton S, Ernst M, Castellanos FX, Pine DS, Milham MP. A functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation of uncertainty in adolescents with anxiety disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:563–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnen CM, Knutson B. The neural basis of financial risk-taking. Neuron. 2005;47:763–770. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DJ, Glimcher PW. Comparing apples and oranges: using reward-specific and reward-general subjective value representation in the brain. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14693–707. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2218-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Powell DK, Wang H, Gold BT, Corbly CR, Joseph JE. Functional dissociation in frontal and striatal areas for processing of positive and negative reward information. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4587–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5227-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin EI, Ressler KJ, Binder E, Nemeroff CB. The neurobiology of anxiety disorders: brain imaging, genetics, and psychoneuroendocrinology. Clin Lab Med. 2010;30:865–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EB, Monk CS, Nelson EE, Parrish JM, Adler A, Blair RJ, Fromm S, Charney DS, Leibenluft E, Ernst M, Pine DS. Abnormal attention modulation of fear circuit function in pediatric generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:97–106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Nelson EE, McClure EB, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Leibenluft E, Blair RJ, Chen G, Charney DS, Ernst M, Pine DS. Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation and attentional bias in response to angry faces in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1091–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke JB, Sarinopoulos I, Oathes DJ, Johnstone T, Whalen PJ, Davidson RJ, Kalin NH. Anticipatory activation in the amygdala and anterior cingulate in generalized anxiety disorder and prediction of treatment response. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:302–10. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07101682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulesu E, Sambugaro E, Torti T, Danelli L, Ferri F, Scialfa G, Sberna M, Ruggiero GM, Bottini G, Sassaroli S. Neural correlates of worry in generalized anxiety disorder and in normal controls: a functional MRI study. Psychol Med. 2010;40:117–24. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharot T, Kanai R, Marston D, Korn CW, Rees G, Dolan RJ. Selectively altering belief formation in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:17058–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205828109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharot T, Korn CW, Dolan RJ. How unrealistic optimism is maintained in the face of reality. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14:1475–1479. doi: 10.1038/nn.2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharot T, Riccardi AM, Raio CM, Phelps EA. Neural mechanisms mediating optimism bias. Nature. 2007;450:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature06280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunk DR, Lopez H, DeRubeis RJ. Depressive symptoms are associated with unrealistic negative predictions of future life events. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2006;44:861–882. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain. Thieme; Stuttgart: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein ND. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39:806–820. [Google Scholar]

- Whalen PJ, Johnstone T, Somerville LH, Nitschke JB, Polis S, Alexander AL, Davidson RJ, Kalin NH. A functional magnetic resonance imaging predictor of treatment response to venlafaxine in generalized anxiety disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:858–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SF, Geraci M, Lewis E, Leshin J, Teng C, Averbeck B, Meffert H, Ernst M, Blair RJ, Grillon C, Blair KS. Prediction Error Representation in Patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder During Passive Avoidance. The American Journal of Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15111410. under revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]