Abstract

Giant cell tumor (GCT) is a benign bone tumor with aggressive characteristics. They are more prevalent in the third decade of life and demonstrate a preference for locating in the epiphyseal region of long bones. They have a high local recurrence rate, which depends on the type of treatment and initial tumor presentation. The risk of lung metastases is around 3%.

Between October 2010 and August 2014, nine patients diagnosed with locally advanced GCT or with pathological fracture to the knee level underwent surgical treatment. The aim of this study was to evaluate the results of the treatment, particularly with regard to relapse, and to conduct a literature review.

There was a predominance of males (77.7%). The most common location was the distal femur. Four patients (44%) developed local recurrence in the first year after surgery, three in distal femur and one in proximal tibia. Of the two patients with pathologic fracture at diagnosis, one of them presented recurrence after five months.

The treatment of GCT is still a challenge. The authors believe that the best treatment method is wide resection and reconstruction of bone defects with non-conventional endoprostheses. Patients should be aware and well informed about the possible complications and functional losses that may occur as a result of the surgical treatment chosen and the need for further surgery in the medium and long term.

Keywords: Giant cell tumors, Bone neoplasms, Knee joint

Resumo

O tumor de células gigantes (TCG) é um tumor ósseo benigno com características agressivas. São mais prevalentes na terceira e quarta décadas de vida e localizam-se preferencialmente na região epifisária dos ossos longos. Apresentam altas taxas de recorrência local, a qual depende do tipo de tratamento e da apresentação inicial do tumor. O risco de disseminação sistêmica (metástases pulmonares) gira em torno de 3%.

Entre outubro de 2010 e agosto de 2014, nove pacientes com diagnóstico de TCG localmente avançados ou com fratura patológica ao nível do joelho foram submetidos a tratamento cirúrgico. O objetivo deste estudo foi avaliar os resultados decorrentes do tratamento, especialmente com relação à recidiva, e fazer uma revisão da literatura.

Houve predominância do sexo masculino (77,7%). A localização mais comum foi o fêmur distal. Quatro pacientes (44%) apresentaram recidiva local no primeiro ano de pós-operatório, três do fêmur distal e um na tíbia proximal. Dos três pacientes que apresentaram fratura patológica no momento do diagnóstico, um deles apresentou recidiva cinco meses após a cirurgia. O tratamento ainda é um grande desafio. Acreditamos que o melhor método de tratamento é a ressecção ampla com reconstrução da falha óssea com endoprótese não convencional. Os pacientes devem estar cientes e bem orientados quanto às possíveis complicações e prejuízos funcionais que podem ocorrer em decorrência do tratamento escolhido e quanto à necessidade de novas intervenções cirúrgicas em médio e longo prazo.

Palavras-chave: Tumores de células gigantes, Neoplasias ósseas, Articulação do joelho

Introduction

Giant cell tumor (GCT) is a benign bone tumor with aggressive characteristics. It represents approximately 5% of primary bone tumors and about 15% of benign bone tumors.1

It consists of giant osteoclast-like cells interspersed with a hypercellular and vascularized stroma, which differentiates it from other tumor or pseudotumoral lesions, such as chondroblastoma, brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism, and aneurysmal bone cyst.2

It is more prevalent within the third and fourth decades of life, and is most commonly located in the epiphyseal region of the long bones. The most affected areas are the distal femur, proximal tibia, and distal radius.

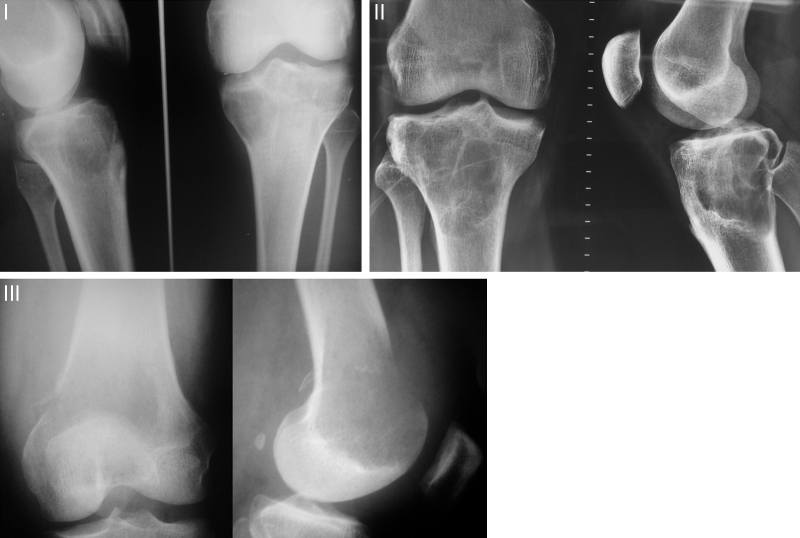

Campanacci et al.3 classified GCTs into three types according to their biological behavior, radiographic appearance, and degree of bone destruction (Fig. 1). Type I are considered latent and are represented by small, intraosseous lesions. Type II are active and radiographically larger, but with intact periosteum. Type III are aggressive, extending throughout the periosteum and surrounding tissues.3, 4, 5

Fig. 1.

Campanacci classification.

I, quiescent, intraosseous lesions; II, active, with intact periosteum; III, aggressive, with invasion of soft tissues.

Surgical treatment is usually necessary. Surgery aims for complete tumor resection, preserving bone architecture and joint function, correction of the defect created with techniques such as autograft, homograft, arthrodesis, non-conventional endoprostheses, and filling with bone cement.6

Intralesional resection is usually the treatment of choice for Campanacci I and II tumors.1 This should be accompanied by one or more local adjuvant methods (electrocautery, phenol, liquid nitrogen, argon plasma coagulation, etc.) in an attempt to decrease the chance of recurrence.2 Campanacci III tumors, due to their size and local aggressiveness, are usually best addressed through wide resection with defect correction.1, 6

They present high rates of local recurrence, which depends on the type of treatment and initial presentation of the tumor. The risk of systemic dissemination (lung metastasis) is approximately 3%.1

This study assessed nine patients diagnosed with locally advanced GCT at the knee level and the outcome one year after surgery. The tumors classified as Campanacci III were included in this study, as well as cases of pathological fracture.

This study aimed to evaluate the results of the treatment of these patients, especially in relation to relapse, and to review the literature on the treatment of locally advanced GCT at the knee.

Methods

Between October 2010 and August 2014, nine patients diagnosed with locally advanced GCT at the knee (distal femur and proximal tibia) underwent surgical treatment. The diagnosis of the lesions without fracture was confirmed by percutaneous biopsy using a Jamshidi needle. In cases with pathological fracture, after local staging and surgery, the diagnosis was confirmed by histologic study.

The inclusion criteria were: patients diagnosed with Campanacci III GCT at the knee or who presented pathological fracture as a diagnosis. Predominant location was the distal femur, observed in 87.5% (seven patients), and the proximal tibia, in 13.5% (two patients).

Patients were divided according to sex, age, tumor location, presence of pathological fracture, and type of treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data of the patients selected for the study.

| Sex | Age | Location | Fracture | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Male | 36 | Distal femur | No | Curettage + cement |

| Patient 2 | Male | 39 | Distal femur | No | Curettage + cement |

| Patient 3 | Male | 29 | Distal femur | Yes | Curettage + cement |

| Patient 4 | Male | 32 | Distal femur | Yes | Curettage + cement |

| Patient 5 | Male | 35 | Distal femur | No | Resection + endoprosthesis |

| Patient 6 | Male | 26 | Proximal tibia | No | Curettage + cement |

| Patient 7 | Female | 41 | Distal femur | No | Curettage + cement |

| Patient 8 | Male | 34 | Distal femur | No | Curettage + cement |

| Patient 9 | Female | 32 | Proximal tibia | Yes | Resection + endoprosthesis |

The most commonly used treatment method was curettage of the lesion, followed by an adjuvant method with electrocauterization and bone cement, in seven patients. Two patients underwent en bloc resection of the lesion and joint replacement using non-conventional endoprosthesis. For these patients, significant bone destruction with tumor extension to the neighboring soft tissues was observed, which made any other more conservative method unfeasible. In cases of pathological fracture of the distal femur, the authors chose to approach the tumor, performing curettage of the lesion with electrocauterization of the tumor core, reduction of the deviated fragments with anatomical reduction of the articular surface, fixation with a special plate with locking screws, and lesion cementation. For patients with pathological fracture of the proximal tibia, extensive resection was performed with endoprosthesis replacement.

Evaluation of bone destruction through radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography was paramount to define surgical strategy. In patients whose lesion did not allow anatomical bone reconstruction, resection and replacement with endoprosthesis were chosen, regardless of the presence of a pathological fracture.

Patients were evaluated every 15 days in the first month, with monthly follow-up appointments up to the third month, and follow-up appointments every three months until one year of surgery. Patients who did not present relapse in the first two years after surgery were considered cured. However, follow-up is annual for an indefinite period.

Results

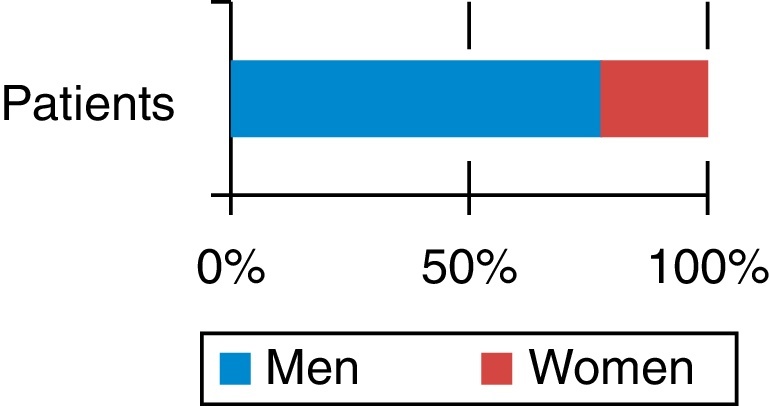

A predominance of males was observed. Out of nine patients evaluated, seven were male (77.7%) and two female (22.2%; Fig. 2). Patient age ranged from 26 to 41 years.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of patients according to gender.

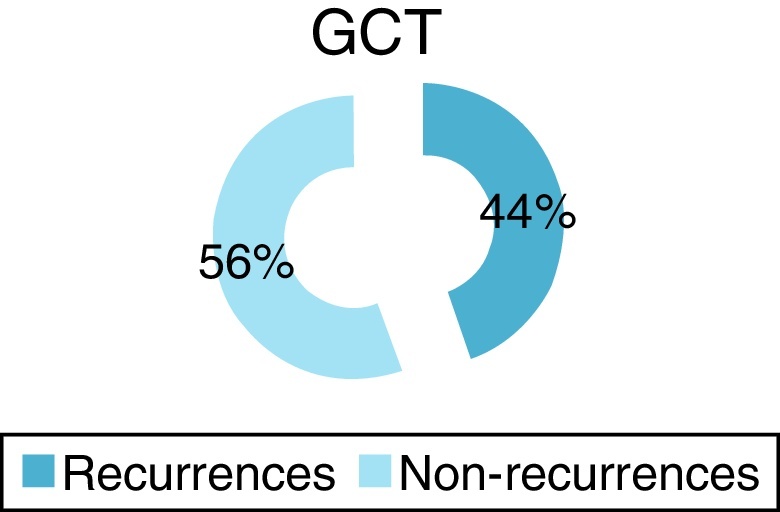

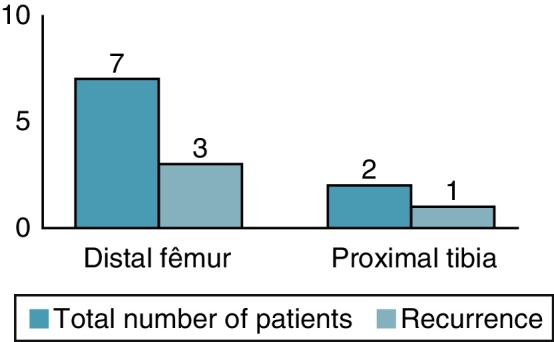

Four patients (44%) developed local recurrence (Fig. 3) within first postoperative year, three in the distal femur and one in the proximal tibia (Fig. 4). Of the two patients who presented a pathological fracture of the distal femur at the time of diagnosis, one presented recurrence five months after surgery. Fig. 5 shows patient 1, who underwent curettage of lesion associated with bone cement in the distal femur, combined with plate fixation. After 11 months, patient presented a bone defect in the posterior cortex due to tumor growth.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of recurrences found in the study after one year.

Fig. 4.

Location of the tumor and number of recurrences.

Fig. 5.

Patient 1 in the immediate post-operative period and in the relapse at 11 months.

In cases of recurrence, patients’ main complaint was reappearance of pain. A new staging with imaging tests was performed to confirm relapse. In one of the patients (patient 3), a new curettage and cementation were performed, with good outcome. For the other three patients, en bloc resection and replacement with endoprothesis was performed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Data of patients who presented recurrence.

| Location | Age | Sex | Months until relapse | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Distal femur | 36 | Male | 11 | Endoprosthesis |

| Patient 2 | Distal femur | 39 | Male | 9 | Endoprosthesis |

| Patient 3 | Distal femur | 29 | Male | 6 | New curettage |

| Patient 4 | Proximal tibia | 26 | Male | 8 | Endoprosthesis |

Discussion

GCT is considered to be a benign lesion, despite its potential for local aggression, recurrence, and occasional lung metastases.7 The frequency of these is approximately 1%–3%, which can be higher in cases with local recurrence, especially when located in the soft tissue.8

This tumor does not remain latent. A small lesion tends to evolve and lead to the progressive destruction of the affected bone.9 Therefore, surgical treatment should be indicated and performed as early as possible.

Curettage associated with an adjuvant method has been defined as the preferred treatment for most cases of GCT.1, 10, 11 This option presents a better functional outcome, but is associated with a higher chance of relapse, as evidenced in some studies.6, 7, 12 Wide resection has the advantage of lower chance of relapse, as it removes the tumor entirely. It is usually reserved for cases of extensive bone destruction, in which joint reconstruction is not feasible.1, 13 Several studies have advocated the use of this technique in Campanacci III tumors, aiming to reduce the risk of recurrence and biomechanical failure.5, 6 Complete bone resection can also be performed in some cases without marked functional impairment, such as in the ulna, fibula, and small bones of the hand and foot.1, 2, 9

However, patients affected by this type of tumor are usually young, and therefore there is a concern to preserve the joint surface and avoid possible early arthroplasty. Joint replacement by non-conventional endoprosthesis brings some disadvantages, such as the need for revision and the risk of successive revisions. Thus, some studies indicate a preference for more conservative reconstruction methods in the treatment of these lesions, in the hope that primary procedure will be definitive. The use of bone cement is a well-established method that presents good long-term oncological and functional results. Regarding the possibility of arthrosis secondary to the use of bone cement, Baptista et al.4 published a retrospective study of 46 cases of GCT undergoing curettage and cementation, concluding that the distance from cement to subchondral bone has a prognostic relationship to the development of osteoarthritis, but not to final functional outcome of the patient.

The incidence of GCT recurrence varies in the literature. Dahlin et al.14 published a study with 60% of local recurrence in GCT patients who underwent curettage and grafting, and recommended a more aggressive resection for local control. The use of methylmethacrylate associated with cauterization of the cavity as local adjuvants in the treatment of GCT significantly decreased the rate of recurrence.5 In a literature review, Zhen et al.15 showed varying recurrence rates, from 12% to 54% within seven years of follow-up (Table 3). Klenke et al.13 observed recurrence rates ranging from 0% to 65%, depending on surgical method. In the present study, 44% of recurrences occurred in the first postoperative year, a period in which the frequency of relapse is greater. However, unlike other studies, only locally aggressive Campanacci III tumors were included in the present study.

Table 3.

Percentage of recurrence in the studies analyzed by Zehn.

| Author | Number of patients | Recurrence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Dahlin, Crupps, and Johnson | 37 | 41 |

| Goldenberg, Campbell, and Bonfiglio | 136 | 54 |

| Larsson, Lorentzon, and Boquist | 30 | 47 |

| Marcove et al. | 52 | 23 |

| Sung et al. | 34 | 41 |

| McDonald et al. | 85 | 34 |

| Jacobs and Clemency | 12 | 17 |

| Campanacci et al. | 151 | 27 |

| Waldram and Sneath | 19 | 37 |

| O’Donnell et al. | 60 | 25 |

| Blackley et al. | 59 | 12 |

Baptista11 indicated that in the presence of fractures with significant deviation, marked deformity, or significant impairment of three cortical areas, the safest procedure is segment resection, from both the oncological standpoint and to reduce morbidity. That author concluded that the approximate volume of tumor, presence of cortical involvement, percentage of the epiphysis width affected, and distance between the lesion border and the articular surface were statistically significant radiographic parameters for the indication and/or prognosis of the treatment with curettage associated with electrocauterization of the lesion wall and filling with bone graft, a technique assessed in his study. Tumor prognosis is directly related to quality of the technique of curettage and/or resection used, and not only to the method of reconstruction or filling.5, 6, 9

Presence of pathological fracture and tumor extension to soft tissues is a controversial subject in the literature.1, 6 McDonald et al.16 concluded that pathological fracture does not increase the likelihood of tumor recurrence, but the association was not statistically significant. O’Donnell et al.12 reported that three (50%) out of six patients with pathologic fractures evolved with recurrence of the tumor. They concluded that there is a correlation between the occurrence of pathological fractures and tumor recurrence. Jesus-Garcia et al.6 indicated that pathological fracture may be an important factor in the association with recurrence, since in its presence, the difficulty in performing effective curettage is greater. In their study, of the eight patients who presented recurrence, 50% had a pathological fracture.

In the present study, conclusion whether the chance of tumor recurrence was directly related to the presence of pathological fracture was not possible. However, the authors believe that contamination of the soft tissue by the tumor, as is the case in Campanacci III and pathologic fracture, is a risk factor for tumor recurrence.6

The use of denosumab has shown good results for the treatment of GCT. This drug inhibits the action of the RANK ligand, therefore decreasing the osteoclastic activity of the tumor.17 Studies indicate a clinical and radiological improvement of the tumor after treatment with subcutaneous denosumab at a dose of 120 mg monthly, with additional doses on the 8th and 15th day of treatment,17, 18 thus opening a new horizon in the treatment of this tumor. The possibility of controlling the disease after the use of this medication would allow more conservative surgeries, with less chances of recurrence.

Limitations of the present study include the small number of patients. GCT is a rare condition; accounting for an average of 5% of all primary benign tumors of the bone.15 The study only included patients with Campanacci III GCT and those with pathological fracture diagnosis, which further limited the selection of cases. However, few multicentric studies with large numbers of patients were retrieved in the literature. Treatment methods and statistical analyses are different and there is a lack of randomized prospective studies.

Final considerations

GCT treatment (especially cases of Campanacci III) is still very challenging. The authors believe that, from the oncological standpoint, the best treatment method for locally advanced knee GCT is extensive resection with reconstruction of the bone defect using non-conventional endoprosthesis. Despite the improvement in intralesional resection techniques associated with intraoperative adjuvant methods, the risk of relapse remains high. Due to the complexity of the treatment and its consequences, patient should be aware and well informed about the possible complications and functional losses that may occur as a result of the treatment chosen, as well as the need for new surgical interventions in the medium and long term.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Hospital do Servidor Público Estadual de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

References

- 1.Klenke F.M., Wenger D.E., Inwards C.Y., Rose P.S., Sim F.H. Giant cell tumor of bone: risk factors for recurrence. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(2):591–599. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1501-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mello G.P., Sonehara H.A., Neto M.A. Endoprótese não cimentada no tratamento de tumor de células gigantes de tíbia, 18 anos de evolução. Rev Bras Ortop. 2010;45(6):612–617. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campanacci M., Giunti A., Olmi R. Giant-cell tumours of bone: a study of 209 cases with long term follow up in 130. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1975;1:249–277. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baptista A.M., Camargo A.F.F., Caiero M.T., Rebolledo D.C.S., Correia L.F.M., Camargo O.P. TCG: o que aconteceu após 10 anos de curetagem e cimentação? Estudo restrospectivo de 46 casos. Acta Ortop Bras. 2014;22(6):308–311. doi: 10.1590/1413-78522014220600973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camargo O.P.O. Estado da arte no diagnóstico e tratamento do tumor de células gigantes. Rev Bras Ortop. 2002;37(10):424–429. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jesus-Garcia R., Wajchenberg M., Justino M.A.F., Korukian M., Yshihara H.I., da Ponte F.M. Tumor de células gigantes, análise da invasão articular, fratura patológica, recidiva local e metástase para o pulmão. Rev Bras Ortop. 1997;32(11):849–856. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jesus Garcia R. 2ª ed. Elsevier; Rio de Janeiro: 2013. Diagnóstico e tratamento de tumores ósseos. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lackman R.D., Crawford E.A., King J.J., Ogilvie C.M. Conservative treatment of Campanacci grade III proximal humerus giant cell tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(5):1355–1359. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0583-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szendröi M. Giant-cell tumour of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(1):5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker W.T., Dohle J., Bernd L., Braun A., Cserhati M., Enderle A. Local recurrence of giant cell tumor of bone after intralesional treatment with and without adjuvant therapy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(5):1060–1067. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baptista P.P.R. Tratamento do tumor de células gigantes por curetagem, cauterização pela eletrotermia, regularização com broca e enxerto ósseo autólogo. Rev Bras Ortop. 1995;30(11/12):819–827. [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Donnell R.J., Springfield D.S., Motwani H.K., Ready J.E., Gebhardt M.C., Mankin H.J. Recurrence of giant-cell tumors of the long bones after curettage and packing with cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76(12):1827–1833. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199412000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klenke F.M., Wenger D.E., Inwards C.Y., Rose P.S., Sim F.H. Recurrent giant cell tumor of long bones: analysis of surgical management. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1181–1187. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1560-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahlin D.C., Cupps R.E., Johnson E.W., Jr. Giant-cell tumor: a study of 195 cases. Cancer. 1970;25(5):1061–1070. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197005)25:5<1061::aid-cncr2820250509>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhen W., Yaotian H., Songjian L., Ge L., Qingliang W. Giant-cell tumour of bone. The long-term results of treatment by curettage and bone graft. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(2):212–216. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b2.14362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald D.J., Sim F.H., McLeod R.A., Dahlin D.C. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(2):235–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas D., Henshaw R., Skubitz K., Chawla S., Staddon A., Blay J.Y. Denosumab in patients with giant-cell tumour of bone: an open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(3):275–280. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Branstetter D.G., Nelson S.D., Manivel J.C., Blay J.Y., Chawla S., Thomas D.M. Denosumab induces tumor reduction and bone formation in patients with giant-cell tumor of bone. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(16):4415–4424. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]