This report provides new evidence that different levels of exogenous thiosulfate dynamically change discrete sulfide biochemical metabolite bioavailability in endothelial cells under normoxia or hypoxia, acting in a slow manner to modulate sulfide metabolites. Moreover, our findings also reveal that thiosulfate surprisingly inhibits VEGF-dependent endothelial cell proliferation associated with a reduction in cystathionine-γ-lyase protein levels.

Keywords: thiosulfate, sulfide, antiangiogenesis, glutathione, donor, endothelial cell, vascular endothelial growth factor

Abstract

Recent reports have revealed that hydrogen sulfide (H2S) exerts critical actions to promote cardiovascular homeostasis and health. Thiosulfate is one of the products formed during oxidative H2S metabolism, and thiosulfate has been used extensively and safely to treat calcific uremic arteriopathy in dialysis patients. Yet despite its significance, fundamental questions regarding how thiosulfate and H2S interact during redox signaling remain unanswered. In the present study, we examined the effect of exogenous thiosulfate on hypoxia-induced H2S metabolite bioavailability in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Under hypoxic conditions, we observed a decrease of GSH and GSSG levels in HUVECs at 0.5 and 4 h as well as decreased free H2S and acid-labile sulfide and increased bound sulfide at all time points. Treatment with exogenous thiosulfate significantly decreased the ratio of GSH/GSSG to total sulfide of HUVECs under 0.5 h of hypoxia but significantly increased this ratio in HUVECs under 4 h of hypoxia. These responses reveal that thiosulfate has different effects at low and high doses and under different O2 tensions. In addition, treatment with thiosulfate also diminished VEGF-induced cystathionine-γ-lyase expression and reduced VEGF-induced HUVEC proliferation under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. These results indicate that thiosulfate can modulate H2S metabolites and signaling under various culture conditions that impact angiogenic activity. Thus, thiosulfate may serve as a unique sulfide donor to modulate endothelial responses under pathophysiological conditions involving angiogenesis.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This report provides new evidence that different levels of exogenous thiosulfate dynamically change discrete sulfide biochemical metabolite bioavailability in endothelial cells under normoxia or hypoxia, acting in a slow manner to modulate sulfide metabolites. Moreover, our findings also reveal that thiosulfate surprisingly inhibits VEGF-dependent endothelial cell proliferation associated with a reduction in cystathionine-γ-lyase protein levels.

in mammals, hydrogen sulfide (H2S), like nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO), is a physiological gaseous signal transmitter (7, 9, 12, 25, 28). Endogenous H2S is predominantly produced by tissue-specific enzymes, including cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE), and 3-mercaptosulfurtransferase (3-MST). Accumulating evidence strongly shows that H2S has an important role in the vascular system including vasorelaxation (4, 14, 20, 33), neurotransmission (1, 2, 16, 31, 32), and inflammation (9, 11, 15).

In the biological research of H2S, inorganic sulfide salts (Na2S and NaHS), garlic extracts [diallyl sulfide, diallyl disulfide, and diallyl trisulfide (DATS)], Lawesson’s reagents, and analogs (GYY4137) have been widely used as H2S sources. However, these sources have certain disadvantages for studying the physiological function of H2S. NaHS has been implemented at a concentration of 640 μM as a neuromodulator in brain lysate, and DATS has been used at a concentration of 60 μM for antiangiogenesis in breast cancer cells (24). GYY4137 is a slow-releasing sulfide donor that has been used at a 400 μM concentration in the leukemia cell line HL-60 (21). This concentration is still too high for therapeutic purposes, because H2S concentrations in tissues range from high nanomolar to low micromolar concentrations (19). In addition, these sulfide donors have variable stability and need to be administered in high doses to achieve various effects (21). Therefore, to benefit from the vasodilatory ability of H2S in human or animal studies, there is a need for a low-dose, slow-releasing sulfide donor.

Thiosulfate () has been used extensively and safely in human clinical trials for vascular calcification studies. It increases the solubility of calcium by up to 100,000-fold and can be used to treat calcific uremic arteriopathy in dialysis patients. In addition, sodium thiosulfate is an Food and Drug Administration-approved medication for the treatment of cyanide poisoning.

Thiosulfate can produce H2S through a nonenzymatic pathway or by an enzymatic pathway via a glutathione-dependent reduction (shown below in Eq. 1). Koj et al. (18) reported that glutathione disulfide (GSSG), H2S, and labeled sulfite were produced when rat mitochondria were incubated with oxygen, glutathione (GSH), and [S35]thiosulfate. Production of H2S can be directly compared with the glutathione pathway because high concentrations of H2S reflect a high rate of consumption (30). Interestingly, Curtis and colleagues (3, 10, 18) reported that when S35 was perfused through isolated rat tissue, it was oxidized to thiosulfate. These findings suggest that thiosulfate can involve H2S metabolism through the glutathione pathway, as follows:

| (1) |

H2S can exist in various forms, including free sulfide, acid-labile sulfide, and bound sulfane sulfur. Free sulfides include S2−, HS−, and H2S. Acid-labile sulfides are usually bound to iron in the form of iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters but may also include persulfides. Bound sulfides include bound sulfane sulfur, polysulfides, thiosulfate, polythionates, thiosulfonates, bisorganyl-polysulfanes, and elemental sulfur. We have previously developed precise analytical methods to measure sulfide bioavailability in cells and tissues using monobromobimane (MBB) (6, 25). This MBB method for measuring sulfide by reverse-phase (RP)-HPLC with fluorescence detection is a useful and sensitive quantitative method to measure sulfide metabolism in biological samples.

Hypoxia is an effective stimulus of human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) activation responses (22). Importantly, these responses to hypoxia can be acute or chronic. Hypoxia activates hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs) that induce the expression of VEGF (6). Thus, hypoxia can regulate the proliferation and remodeling of endothelial cells. However, little is known about how varying O2 tensions modulate thiosulfate bioavailability and actions in endothelial cells. Here, we address this topic by the study of thiosulfate on sulfide bioavailability and redox balance in HUVECs under normoxia and hypoxia. Finally, we also investigated the effects of thiosulfate on VEGF-induced proliferation of HUVECs to ascertain its possible role in angiogenic responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

MBB, Tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), sulfosalicylic acid (SSA), 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (DNFB), and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). VEGF164 was purchased from Lifeline Cell Technology. Rabbit β-actin polyclonal antibody and rabbit CSE polyclonal antibodies were obtained from Proteintech. The ECL Western Blotting system was acquired from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Vacutainer tubes, 3.5-in. 25-gauge spinal needles, and 0.5-in. 30-gauge needles were purchased from BD Medical Technology. All other reagents were purchased at the analytical grade.

Cell culture and treatment.

HUVECs were purchased from Lifeline Cell Technology (catalog no. FC-0044) and cultured in VascuLife Basal Medium (catalog no. LM-0002) supplemented with the appropriate LifeFactors Kit (catalog no. LL-0003). All cells were grown in tissue culture flasks under normoxic conditions at 5% CO2-21% O2 at 37°C. Media were changed every 2–3 days. HUVECs were starved 16 h postconfluence in endothelial based media (EBM) supplemented with 0.5% FBS, nonessential amino acids, penicillin-streptomycin, and l-glutamine. HUVECs were the incubated in the hypoxic chamber (5% CO2-1% O2 at 37°C) for 0.5 or 4 h.

Sulfide and thiosulfate measurements.

Bioavailable sulfide and thiosulfate levels were measured as we have previously reported (6, 25, 29). Levels of free sulfide and thiosulfate in HUVECs were measured by HPLC after derivatization with excess MBB as stable products sulfide-dibimane (SDB) and thiosulfate bimane (TSB), respectively. Briefly, HUVECs were homogenized in Tris·HCl buffer [100 mM Tris·HCl (pH 9.5) and 0.1 mM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA)]. Cell lysates were derivatized with MBB and then measured by Shimadzu Prominence 20A equipment with RF-10AXL (excitation wavelength: 390 mm and emission wavelength: 475 mm) and an Eclipse XDB-C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 µm). Typical retention times of SDB and TSB were around 16.5 and 9.5 min, respectively. Free H2S levels were calculated according to standard SDB (25). Thiosulfate stock solution was diluted to the desired concentrations in Tris·HCl buffer and derivatized with MBB to make TSB standard solutions. Acid-labile sulfide was released by an acidic solution [100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 2.6) and 0.1 mM DTPA] and then trapped in 100 mM Tris·HCl buffer (pH 9.5, 0.1 mM DTPA). The bound sulfane sulfur was measured by incubating the samples with 1 mM TCEP in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 2.6, 0.1 mM DTPA), and sulfide measurements were performed in a manner analogous to that described above. Acid-labile sulfide was determined by subtracting the free H2S value from the value obtained by the acid-liberation protocol. The bound sulfane sulfur measurement was determined by subtracting the H2S measurement from the acid-liberation protocol alone from that of the TCEP plus acidic conditions.

Determination of reduced and oxidized glutathione levels by RP-HPLC.

Concentrations of GSH and GSSG in HUVECs were measured by HPLC equipped with a ultraviolet detector as previously described (13). In brief, after homogenates of HUVECs were treated with 100 mM NEM, the mixtures were diluted with an equal volume of trichloroacetic acid (10%) and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min. The excess of NEM in the supernatant was extracted by 5 volumes of dichloromethane. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was alkalinized by 1 M Tris·HCl (pH 10) and then reacted with an equal volume of DNFB solution (1.5% in ethanol) for 3 h at room temperature in the dark. After acidification with 37% HCl, the samples were loaded onto RP-HPLC with a NH2 column and an ultraviolet detector at 355 nm. Elution solvents were 80% methanol (solvent A) and 0.5 M acetate buffer (pH 4.6) (solvent B). Samples were eluted for 0–10 min with an acetate gradient, 70% solvent A and 30% solvent B, followed by a linear gradient, 40−95% solvent B, for 10–35 min. The flow rate was 1 ml/min. The retention times of GSH and GSSG were 7.1 and 23.8 min, respectively.

Cell proliferation measurement and Western blot analysis.

HUVECs were seeded in EBM supplemented with 5% FBS, nonessential amino acids, 1× penicillin-streptomycin, and l-glutamine. After cells had settled and attached, the media were replaced with EBM starvation media as described above. After starvation, the bromodeoxyuridine label (Calbiochem) was added, and the assay was completed according to the manufacturer’s protocol in the presence or absence 50 ng/ml VEGF. Each treatment was incubated for 4 h in either normoxia or hypoxia. For Western blot analysis, cells were lysed in 4 × SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Protein samples were then loaded on a 10% SDS gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Nonspecific proteins were blocked with 5% nonfat milk. Anti-CSE antibody and anti-β-actin antibody were used to detect the CSE expression changes in these HUVECs.

Statistical analysis.

All data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA for independent samples with Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). The Dunnett posttest method was used to determine statistical significance from the control. A 95% confidence interval (P < 0.05) was considered significant.

RESULTS

Sulfide bioavailability of HUVECs under hypoxia.

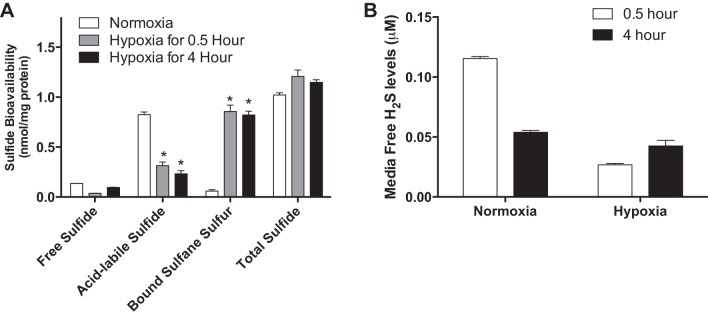

We have previously reported that exogenous H2S donor treatment augments endothelial cell ischemic proliferation and survival under hypoxia involving complex interactions with other gasotransmitters (6). However, little to no information exists regarding the effect of O2 tension on endothelial sulfide metabolite levels. Thus, we first examined whether hypoxia influenced sulfide bioavailability of endothelial cells by evaluating the free sulfide, acid-labile sulfide, and bound sulfane sulfur levels of HUVECs under normoxia or hypoxia at different time points. As shown as Fig. 1A, sulfide bioavailability of HUVECs was significantly altered between normoxia and hypoxia (1% O2) at different time points. Compared with normoxia, acid-labile sulfide levels of HUVECs under hypoxia were markedly decreased. Conversely, bound sulfane sulfur levels of HUVECs under hypoxia were significantly increased compared with normoxic cells. Finally, no significant changes in total sulfide were observed between the various conditions. Figure 1B shows tissue culture media-free H2S levels under normoxia or hypoxia at different time points, revealing that 4 h of hypoxia significantly increased media-free sulfide levels. Together, the effect of hypoxia on sulfide bioavailability is clearly influenced by O2 tension, as it has been noted that O2 can be considered a sulfide antagonist (8). However, the significant changes in acid-labile and bound sulfane sulfur forms of sulfide metabolites highlight the dynamic nature of sulfide species bioavailability.

Fig. 1.

Sulfide bioavailability of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) under normoxia and hypoxia. HUVECs were incubated under normoxia (21% O2-5% CO2 at 37°C) or hypoxia (1.0% O2-5% CO2 at 37°C) conditions for 0.5 or 4 h. A: cell lysates were collected under hypoxic conditions and used to measure free, acid-labile sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur by HPLC. *P < 0.05 vs. normoxia; n = 8. B: free sulfide levels were measured in endothelial cell conditioned tissue culture media at different time points under normoxia or hypoxia conditions.

Effects of thiosulfate on sulfide bioavailability.

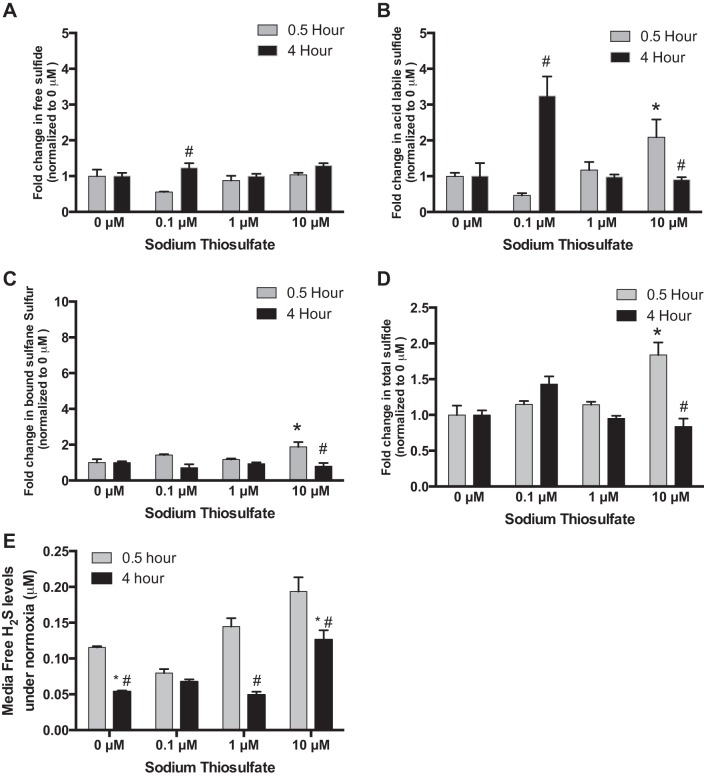

We next studied the effects of thiosulfate on sulfide bioavailability of endothelial cells under normoxia or hypoxia. HUVECs were treated for 0.5 or 4 h with 0, 0.1, 1, or 10 µM thiosulfate. Changes in sulfide metabolite forms were normalized to basal levels of each respective metabolite at 0 μM. Under normoxia, treatment with 0.1 µM thiosulfate significantly increased free and acid-labile sulfide levels of HUVECs at 4 h (Fig. 2, A and B), and treatment with 10 µM thiosulfate significantly increased acid-labile sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur levels of HUVECs at 0.5 h (Fig. 2, B and D). However, tissue culture media-free sulfide levels were significantly reduced by thiosulfate treatment at 4 h under normoxia (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Effects of thiosulfate on sulfide bioavailability of HUVECs under normoxia. Under normoxia (21% O2-5% CO2 at 37°C), HUVECs were treated with 0, 0.1, 1.0, or 10 µM thiosulfate for 0.5 or 4 h, respectively. All data are normalized to respective metabolite levels without thiosulfate treatment (0 μM). A: change in free sulfide levels with varying thiosulfate levels at different time points. B: changes in acid-labile sulfide levels with varying thiosulfate levels at different time points. C: changes in bound sulfane sulfur levels with different thiosulfate doses at different time points. D: changes in total sulfide levels in response to different thiosulfate treatments at different time points. E: endothelial cell conditioned media free H2S levels with various thiosulfate treatments over time. *P < 0.05 vs. treatment with 0 µM of thiosulfate; #P < 0.05 vs. treatment with the same dose of thiosulfate; n = 8.

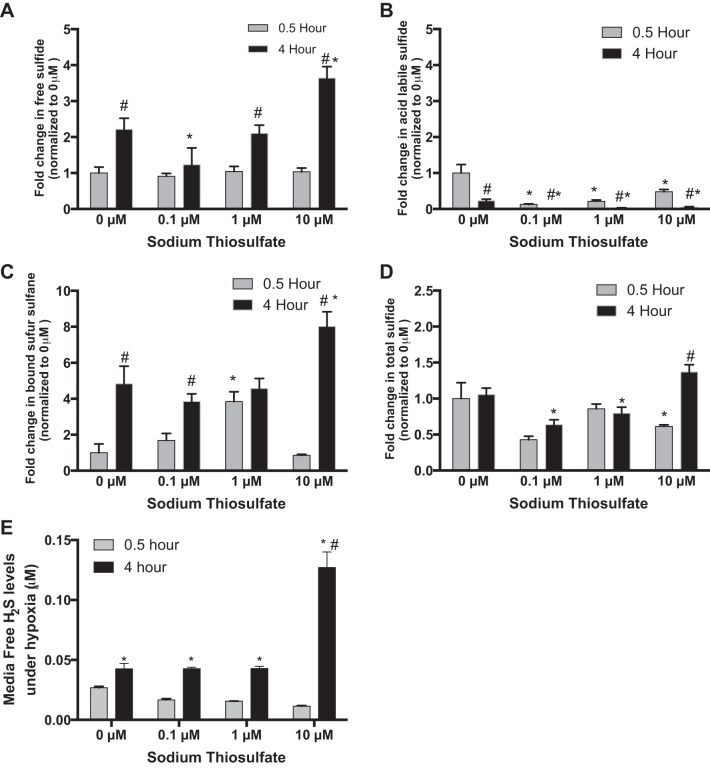

Under hypoxia, free sulfide, acid-labile sulfide, and bound sulfane sulfur levels of HUVECs were significantly changed by treatment with thiosulfate at 4 h (Fig. 3, A–C). Interestingly, acid-labile sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur levels of HUVECs were significantly reduced and elevated respectively by thiosulfate treatment at both time points (Fig. 3, B and C). While total intracellular sulfide levels did significantly fluctuate, the overall changes were less dramatic compared with changes in biochemical forms (Fig. 3D). Finally, thiosulfate treatment at various doses increased free sulfide levels in the media of hypoxic HUVEC at only the 4-h time point (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Effects of thiosulfate on sulfide bioavailability of HUVECs under hypoxia. Under hypoxia (1.0% O2-5% CO2 at 37°C), HUVECs were treated with 0, 0.1, 1.0, or 10 µM thiosulfate for 0.5 or 4 h, respectively. All data are normalized to respective metabolite levels without thiosulfate treatment (0 μM). A: change in free sulfide levels with varying thiosulfate levels at different time points. B: changes in acid-labile sulfide levels with varying thiosulfate levels at different time points C: changes in bound sulfane sulfur levels with different thiosulfate doses at different time points. D: changes in total sulfide levels in response to different thiosulfate treatments at different time points. E: endothelial cell conditioned media free H2S levels with various thiosulfate treatments over time. *P < 0.05 vs. treatment with 0 µM of thiosulfate; #P < 0.05 vs. treatment with the same dose of thiosulfate; n = 8.

Effects of thiosulfate on redox balance.

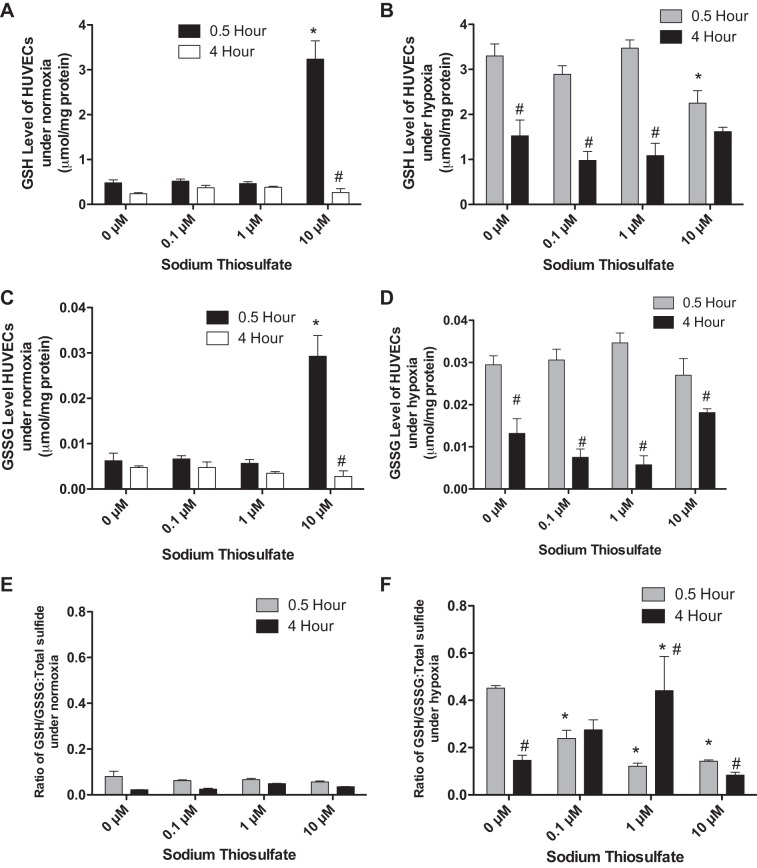

Due to the complexity of time-dependent redox imbalance effects, we only investigated the changes of GSH and GSSG in HUVECs treated with 0.1, 1, and 10 µM thiosulfate for 0.5 or 4 h. Under normoxia, GSH and GSSG levels were only significantly increased in HUVECs treated with 10 µM thiosulfate for 0.5 h (Fig. 4, A and C, respectively). There was no difference in the ratio of GSH/GSSG to total sulfide of HUVECs treated with 0, 0.1, 1, or 10 µM thiosulfate for 0.5 or 4 h (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Effects of thiosulfate on reduced and oxidized glutathione levels of HUVEC cells under normoxia and hypoxia. HUVECs were incubated under normoxia (21% O2-5% CO2 at 37°C) or hypoxia (1.0% O2-5% CO2 at 37°C) for 0.5 or 4 h along with treatment of 0, 0.1, 1.0, or 10 µM thiosulfate. A: reduced GSH levels of HUVECs treated with sodium thiosulfate under normoxia. B: HUVECs reduced GSH levels with sodium thiosulfate treatment under hypoxia. C and D: oxidized GSSG levels in HUVECs with various amounts of sodium thiosulfate under normoxia and hypoxia, respectively. E and F: ratio of GSH/GSSG to total sulfide levels under normoxia and hypoxia, respectively. *P < 0.05 vs. treatment with 0 µM thiosulfate; #P < 0.05 vs. treatment with the same dose of thiosulfate; n = 8.

Under hypoxia, GSH and GSSG levels were not significantly changed except with 10 µM thiosulfate treatment at 0.5 and 4 h but were higher than that of HUVECs under normoxia (Fig. 4, B and D). From the 0.5- to 4-h time point, GSH and GSSG levels were significantly decreased in HUVECs treated with 0, 0.1, 1, or 10 µM thiosulfate. Under normoxia, there were only significant decreases of the ratio of GSH/GSS to total sulfide in HUVECs treated for 4 h with the same dose of thiosulfate. Under hypoxia, thiosulfate treatment resulted in a significant decrease of the ratio of GSH/GSSG to total sulfide in HUVECs treated for 0.5 h. Interestingly, long-time (4 h) thiosulfate treatment resulted in a significantly different change in the ratio of GSH/GSSG to total sulfide in HUVECs (Fig. 4F). These data indicate that thiosulfate preferentially decreased the ratio of GSH/GSSG to total sulfide at lower concentrations of thiosulfate but was increased at higher concentrations at 4 h of hypoxic conditions.

Effects of thiosulfate on VEGF-dependent endothelial proliferation.

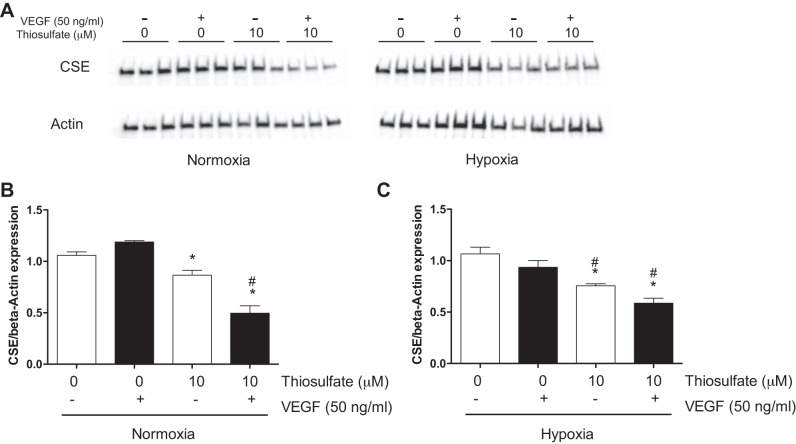

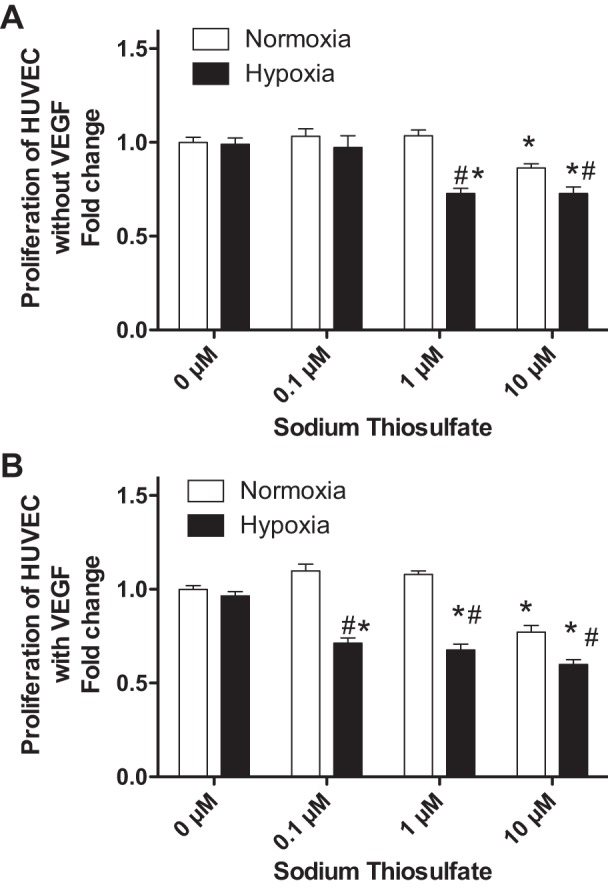

To determine the role of thiosulfate in angiogenic response, we next investigated the effect of thiosulfate on endothelial proliferation by bromodeoxyuridine assay. As shown in Fig. 5A, compared with HUVECs treated with 0 µM thiosulfate, HUVEC proliferation was significantly decreased in HUVECs with treatment of 10 µM sodium thiosulfate under normoxia (0.8639 ± 0.0222, P < 0.001) and significantly decreased in HUVECs with treatment of 1.0 or 10 µM sodium thiosulfate under hypoxia (0.7255 ± 0.0284, P < 0.001, and 0.7255 ± 0.0358, P < 0.001, respectively). In the VEGF induced-proliferation assay (Fig. 5B), compared with HUVECs treated with 0 µM thiosulfate, HUVEC proliferation was only significantly decreased in HUVECs treated with 10 µM thiosulfate under normoxia (0.7715 ± 0.0357, P < 0.001) and significantly decreased in HUVECs with treatment of 0.1, 1.0, or 10 µM sodium thiosulfate under hypoxia (0.7126 ± 0.0276, P < 0.001; 0.6765 ± 0.0306, P < 0.001; and 0.5994 ± 0.0247, P < 0.001, respectively). In addition, we examined the CSE expression in HUVECs treated with VEGF or 10 µM thiosulfate under normoxia and hypoxia. As shown in Fig. 6, thiosulfate treatment significantly decreased VEGF-regulated CSE expression in HUVECs under either hypoxia or normoxia.

Fig. 5.

Effects of thiosulfate on proliferation of endothelial cells. A: the effect of thiosulfate treatments on HUVEC proliferation under normoxia or hypoxia without VEGF treatment. B: effect of thiosulfate treatment on HUVEC proliferation with VEGF treatment under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. *P < 0.05 vs. treatment with 0 µM thiosulfate; #P < 0.05 vs. treatment with the same dose of thiosulfate; n = 8.

Fig. 6.

Effects of hypoxia/thiosulfate treatment on cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) expression in HUVECs. A: effect of thiosulfate treatments on HUVEC CSE expression under normoxia or hypoxia without VEGF treatment. The expression levels of CSE in HUVECs were examined by Western blot analysis (β-actin was used as an internal control). B and C: blots were quantified by densitometry and plotted as the ratio of CSE to β-actin. *P < 0.05 vs. treatment with 0 µM thiosulfate; #P < 0.05 vs. treatment with the same dose of thiosulfate; n = 3.

DISCUSSION

Endogenous H2S is generated in mammalian cells via enzymatic and nonenzymatic pathways. It is well known that CSE, CBS, and 3-MST are key enzymes in the enzymatic pathway of H2S production. CBS is found predominantly in the brain and nervous system, where H2S is released in the reaction of cysteine and homocysteine to cystathionine. CSE is responsible for H2S generation in the vascular tissue through a reaction of l-cysteine and cystathionine. 3-MST is mainly localized to the mitochondria. The expression of these enzymes may occur in a preferential tissue manner where they can convert cysteine or cysteine derivatives to H2S, which contributes to H2S homeostasis.

However, nonenzymatic processes of H2S generation are less well understood, including the reaction of glucose and cysteine, direct reduction of glutathione and elemental sulfur, and organic polysulfides (5, 17). Thiosulfate is a metabolite of H2S and also generates H2S through a reductive reaction involving pyruvate, which acts as a hydrogen donor (19). In this manner, thiosulfate could serve as a useful recycling pathway to augment or maintain H2S bioavailability under certain conditions. Use of thiosulfate as a selective H2S donor for specific disease conditions could be a potent and effective therapeutic modality. Recent work by Ichinose and colleagues (23, 27) has revealed that sodium thiosulfate can indeed confer protection against acute lung injury via LPS or cecal ligation and puncture and against neuronal ischemia. However, it remains unclear how thiosulfate-based therapies alter specific cellular sulfide metabolite levels (e.g., acid-labile and bound sulfane) under hypoxic conditions.

Our goal in the present study was to better understand the impact of exogenous sodium thiosulfate treatment on endothelial sulfide metabolites bioavailability and its subsequent impact on glutathione metabolites in normoxic and hypoxic situations. Importantly, hypoxia alone decreased acid-labile sulfide levels but increased bound sulfane sulfur levels in HUVECs. After treatment with thiosulfate, sulfide bioavailability of HUVECs changed in a temporal manner under both normoxia and hypoxia. Specifically, no significant changes were seen in free, acid-labile, and bound sulfane sulfur levels of HUVECs treated with 0.1 µM sodium thiosulfate for 0.5 h under normoxia; however, all of the levels were increased after 4 h of incubation. This observation may likely involve cellular transportation effects of thiosulfate as it has recently been shown that SCL13A4 serves as a thiosulfate transporter (23). However, the impact of thiosulfate on specific sulfide metabolites was different under hypoxic conditions. A higher amount (10 µM) of thiosulfate was required to significantly increase free sulfide, bound sulfane sulfur, and total sulfide levels. This likely reflects the fact that hypoxia substantially augments sulfide metabolite formation and stability but could also involve changes in thiosulfate transport activity that remain unknown. Together, our findings reveal that thiosulfate is a slow, effective sulfide donor at low concentrations under normoxic conditions, which may provide some insights into its pharmacological behavior for various disease conditions.

In the H2S field, sulfide donors, including H2S gas, inorganic sulfide salts (Na2S and NaHS), garlic and related sulfur compounds (DADS and DATS), Lawesson’s reagent, and analogs (GYY4137), have become important (yet sometimes contentious) research tools to study biological functions and mechanisms of H2S therapy. All of these donors release H2S through diverse mechanisms and at the same time can form various metabolic byproducts. This likely contributes to the fact that donors often appear to have inconsistent functions potentially due to byproduct interference also showing biological effects. However, the reaction of thiosulfate to produce sulfide (2GSH + → GSSG + + H2S) represents an endogenous metabolic pathway whose end products and their effects are well known. Our results extend this insight revealing the impact of both thiosulfate levels and cellular O2 tension on endothelial glutathione metabolism, which is useful in understanding how thiosulfate metabolism occurs under relevant cellular pathology conditions.

It is well known that endothelial dysfunction is associated with various cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases. Numerous studies have shown that H2S has anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, and antioxidant effects (19, 26). In addition, H2S may prime endothelial cells toward angiogenesis. Hence, H2S is important in restoring endothelial function. We have previously reported that exogenous sodium sulfide therapy increases VEGF expression in ischemic tissue but not nonischemic tissue (6). Therefore, we examined the effect of thiosulfate on VEGF-induced proliferation of HUVECs under normoxia or hypoxia. To our surprise, it was observed that low concentrations of thiosulfate blunted VEGF-induced proliferation of HUVECs under hypoxia and thiosulfate diminished VEGF-dependent CSE expression. Further investigation is certainly needed to determine how thiosulfate antagonizes VEGF-dependent endothelial proliferation under hypoxia and whether such a response occurs similarly in vivo.

In summary, we report the effects of thiosulfate on sulfide bioavailability in endothelial cells under normoxia and hypoxia. It is clear that exogenous thiosulfate treatment influences sulfide metabolite levels in a dose- and condition-specific manner that impacts endothelial glutathione metabolism. These findings are useful in considering future studies aimed toward the use of thiosulfate as a sulfide donor or investigations targeted toward understanding endogenous recycling of the metabolite.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-113303 (to C. G. Kevil).

DISCLOSURES

C. G. Kevil has intellectual property regarding H2S measurement and equity in Innolyzer, LLC. X. Shen has intellectual property regarding H2S measurement and is a consultant for Innolyzer, LLC.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.L., C.G.K., and X.S. conceived and designed research; A.L., S.P., and X.S. performed experiments; A.L., S.P., J.D.G., C.G.K., and X.S. analyzed data; A.L., C.G.K., and X.S. interpreted results of experiments; A.L., S.P., J.D.G., and C.G.K. prepared figures; A.L., J.D.G., and X.S. drafted manuscript; J.D.G., C.G.K., and X.S. edited and revised manuscript; C.G.K. and X.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe K, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J Neurosci 16: 1066–1071, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austgen JR, Hermann GE, Dantzler HA, Rogers RC, Kline DD. Hydrogen sulfide augments synaptic neurotransmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J Neurophysiol 106: 1822–1832, 2011. doi: 10.1152/jn.00463.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartholomew TC, Powell GM, Dodgson KS, Curtis CG. Oxidation of sodium sulphide by rat liver, lungs and kidney. Biochem Pharmacol 29: 2431–2437, 1980. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(80)90346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bełtowski J, Jamroz-Wiśniewska A. Hydrogen sulfide and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Molecules 19: 21183–21199, 2014. doi: 10.3390/molecules191221183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benavides GA, Squadrito GL, Mills RW, Patel HD, Isbell TS, Patel RP, Darley-Usmar VM, Doeller JE, Kraus DW. Hydrogen sulfide mediates the vasoactivity of garlic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 17977–17982, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705710104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bir SC, Kolluru GK, McCarthy P, Shen X, Pardue S, Pattillo CB, Kevil CG. Hydrogen sulfide stimulates ischemic vascular remodeling through nitric oxide synthase and nitrite reduction activity regulating hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent angiogenesis. J Am Heart Assoc 1: e004093, 2012. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.004093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung NS, Peng ZF, Chen MJ, Moore PK, Whiteman M. Hydrogen sulfide induced neuronal death occurs via glutamate receptor and is associated with calpain activation and lysosomal rupture in mouse primary cortical neurons. Neuropharmacology 53: 505–514, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung HS, Wang SB, Venkatraman V, Murray CI, Van Eyk JE. Cysteine oxidative posttranslational modifications: emerging regulation in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res 112: 382–392, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunha TM, Dal-Secco D, Verri WA Jr, Guerrero AT, Souza GR, Vieira SM, Lotufo CM, Neto AF, Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ. Dual role of hydrogen sulfide in mechanical inflammatory hypernociception. Eur J Pharmacol 590: 127–135, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis CG, Bartholomew TC, Rose FA, Dodgson KS. Detoxication of sodium 35 S-sulphide in the rat. Biochem Pharmacol 21: 2313–2321, 1972. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(72)90382-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gemici B, Elsheikh W, Feitosa KB, Costa SK, Muscara MN, Wallace JL. H2S-releasing drugs: anti-inflammatory, cytoprotective and chemopreventative potential. Nitric Oxide 46: 25–31, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geng B, Yang J, Qi Y, Zhao J, Pang Y, Du J, Tang C. H2S generated by heart in rat and its effects on cardiac function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 313: 362–368, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giustarini D, Dalle-Donne I, Colombo R, Milzani A, Rossi R. An improved HPLC measurement for GSH and GSSG in human blood. Free Radic Biol Med 35: 1365–1372, 2003. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holwerda KM, Karumanchi SA, Lely AT. Hydrogen sulfide: role in vascular physiology and pathology. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 24: 170–176, 2015. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter JP, Hosgood SA, Patel M, Furness P, Sayers RD, Nicholson ML. Hydrogen sulfide reduces inflammation following abdominal aortic occlusion in rats. Ann Vasc Surg 29: 353–360, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide and polysulfides as signaling molecules. Proc Jpn Acad, Ser B, Phys Biol Sci 91: 131–159, 2015. doi: 10.2183/pjab.91.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimura H. Production and physiological effects of hydrogen sulfide. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 783–793, 2014. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koj A, Frendo J, Janik Z. [35S]thiosulphate oxidation by rat liver mitochondria in the presence of glutathione. Biochem J 103: 791–795, 1967. doi: 10.1042/bj1030791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolluru GK, Shen X, Bir SC, Kevil CG. Hydrogen sulfide chemical biology: pathophysiological roles and detection. Nitric Oxide 35: 5–20, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laggner H, Hermann M, Esterbauer H, Muellner MK, Exner M, Gmeiner BM, Kapiotis S. The novel gaseous vasorelaxant hydrogen sulfide inhibits angiotensin-converting enzyme activity of endothelial cells. J Hypertens 25: 2100–2104, 2007. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32829b8fd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee ZW, Zhou J, Chen CS, Zhao Y, Tan CH, Li L, Moore PK, Deng LW. The slow-releasing hydrogen sulfide donor, GYY4137, exhibits novel anti-cancer effects in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 6: e21077, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim To WK, Kumar P, Marshall JM. Hypoxia is an effective stimulus for vesicular release of ATP from human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Placenta 36: 759–766, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marutani E, Yamada M, Ida T, Tokuda K, Ikeda K, Kai S, Shirozu K, Hayashida K, Kosugi S, Hanaoka K, Kaneki M, Akaike T, Ichinose F. Thiosulfate mediates cytoprotective effects of hydrogen sulfide against neuronal ischemia. J Am Heart Assoc 4: e002125, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nkrumah-Elie YM, Reuben JS, Hudson A, Taka E, Badisa R, Ardley T, Israel B, Sadrud-Din SY, Oriaku E, Darling-Reed SF. Diallyl trisulfide as an inhibitor of benzo(a)pyrene-induced precancerous carcinogenesis in MCF-10A cells. Food Chem Toxicol 50: 2524–2530, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pattillo CB, Bir SC, Branch BG, Greber E, Shen X, Pardue S, Patel RP, Kevil CG. Dipyridamole reverses peripheral ischemia and induces angiogenesis in the Db/Db diabetic mouse hind-limb model by decreasing oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 50: 262–269, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Predmore BL, Lefer DJ, Gojon G. Hydrogen sulfide in biochemistry and medicine. Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 119–140, 2012. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakaguchi M, Marutani E, Shin HS, Chen W, Hanaoka K, Xian M, Ichinose F. Sodium thiosulfate attenuates acute lung injury in mice. Anesthesiology 121: 1248–1257, 2014. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schicho R, Krueger D, Zeller F, Von Weyhern CW, Frieling T, Kimura H, Ishii I, De Giorgio R, Campi B, Schemann M. Hydrogen sulfide is a novel prosecretory neuromodulator in the guinea-pig and human colon. Gastroenterology 131: 1542–1552, 2006. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tokuda K, Kida K, Marutani E, Crimi E, Bougaki M, Khatri A, Kimura H, Ichinose F. Inhaled hydrogen sulfide prevents endotoxin-induced systemic inflammation and improves survival by altering sulfide metabolism in mice. Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 11–21, 2012. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vitvitsky V, Kabil O, Banerjee R. High turnover rates for hydrogen sulfide allow for rapid regulation of its tissue concentrations. Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 22–31, 2012. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace JL, Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide-based therapeutics: exploiting a unique but ubiquitous gasotransmitter. Nat Rev Drug Discov 14: 329–345, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nrd4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White BJ, Smith PA, Dunn WR. Hydrogen sulphide-mediated vasodilatation involves the release of neurotransmitters from sensory nerves in pressurized mesenteric small arteries isolated from rats. Br J Pharmacol 168: 785–793, 2013. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu D, Hu Q, Ma F, Zhu YZ. Vasorelaxant effect of a new hydrogen sulfide-nitric oxide conjugated donor in isolated rat aortic rings through cGMP pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016: 7075682, 2016. doi: 10.1155/2016/7075682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]