Summary

Increasing evidence supports a major role for the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) in energy balance physiology. The RAS exists as a circulating system but also as a local paracrine/autocrine signaling mechanism in target tissues including the gastrointestinal tract, the brain, the kidney, and distinct adipose beds. Through activation of various receptors in these target tissues, the RAS contributes to the control of food intake behavior, digestive efficiency, spontaneous physical activity, and aerobic and anaerobic resting metabolism. Although the array of methodologies available to assess the many aspects of energy balance can be daunting for an investigator new to this area, a relatively straightforward array of entry-level and advanced methodologies can be employed to comprehensively and quantitatively dissect the effects of experimental manipulations on energy homeostasis. Such methodologies and a simple initial workflow for the use of these methods are described in this chapter, including the use of metabolic caging systems, bomb calorimetry, body composition analyzers, respirometry systems, and direct calorimetry systems. Finally, a brief discussion of the statistical analyses of metabolic data is included.

Keywords: Energy Balance, Caloric Balance, Obesity, Calorimetry, Metabolism, Digestive Efficiency, Energy Efficiency, Resting Metabolic Rate, Aerobic, Anaerobic

1. Introduction

Genetic, dietary, behavioral and pharmacological manipulations often result in changes in energy balance. Such changes are primarily mediated through altered food intake behavior, digestive efficiency, spontaneous physical activity, and aerobic or anaerobic resting metabolism (Table 1). As we recently reviewed, the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) has been implicated in the physiological / pathophysiological control of each of these endpoints [1]. Intriguingly, the RAS can simultaneously activate opposing effects (depending upon the tissue site of action, receptors activated, and endpoint of interest) which can be reflected in large and opposing changes in individual phenotypes (e.g. food intake and resting metabolic rate) that ultimately result in no net change in body mass. Thus, investigators studying the effects of various manipulations of the RAS upon metabolic physiology may benefit from a simple rubric for dissecting the relative effects of the RAS upon individual mechanisms that contribute to energy balance in addition to the simple, integrated endpoint of total body mass.

Table 1.

The four major mechanisms of energy flux, and common methodologies to assess these components.

| Energy Intake Mechanisms | Energy Output Mechanisms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Intake | Digestive Efficiency | Physical Activity | Resting Metabolism | |

| Type of mechanism | Behavior | Biology | Behavior | Biology |

| Contribution to energy balance | Maximally sets the amount of calories to be balanced by energy expenditure | Scales calories actually absorbed from 0–100% of those consumed | Typically contributes 0–40% of total energy expenditure | Typically contributes 60–100% of total energy expenditure |

| Common methods | Food weights (quantitative), Consumption patterning (qualitative) | Bomb calorimetry (quantitative), Fecal acid steatocrit or Metabolomics (qualitative) | Photoelectric beam break, Wheel rotations, Radiotelemetric implant (all qualitative) | Direct calorimetry (for total metabolic rate), Respirometry (aerobic metabolism) (all quantitative) |

It is important to recognize that at the population level, human obesity is the result of very small net imbalances of caloric intake versus output spread over long periods of time. One highly publicized estimate suggests that roughly 7.2 kcal/day imbalance between input and output can explain the obesity epidemic in the United States [2]. Compared to a normal 2,000 kcal/day diet, 7.2 kcal/day reflects a 0.35% imbalance. While the exact accuracy of this estimate has been contested by various groups, there is essentially universal agreement that obesity is the result of very small differences between caloric input and output. By extension, any physiological or behavioral mechanisms that contribute to energy balance must be very tightly controlled. Therefore, all mechanisms contributing to energy balance represent potential therapeutic targets for obesity and stopping one’s investigation of the effects of any manipulation (of the RAS or any system) after only measuring body mass and food intake behaviors is inadequate and inappropriate. At minimum, investigators should consider calculating the fraction of an observed change in body mass that can be attributed to a specific endpoint such as altered food intake behavior.

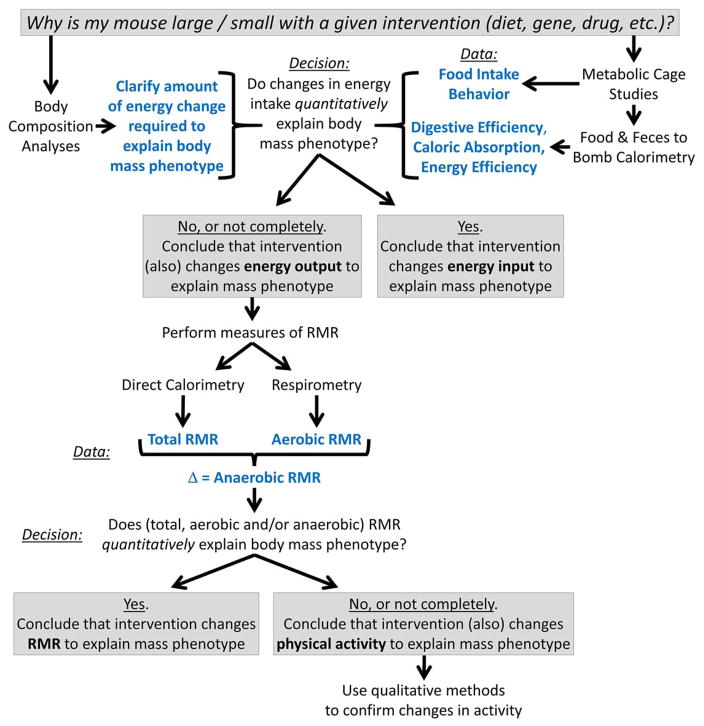

In this chapter, we outline a simple workflow (Figure 1) which uses a combination of classic and emerging technologies to allow for straightforward, comprehensive and quantitative assessments of energy balance in laboratory mice. Similar workflows could be adapted for any species of interest, but equipment descriptions herein are tailored for use with mice.

Figure 1. Proposed workflow to assess energy balance in laboratory mice.

To comprehensively identify the mechanism(s) that contribute to an observed body mass phenotype, a quantitative approach is required. One simple workflow is to use body composition analysis to clarify the total amount of energy change that is required to produce an observed metabolic phenotype, then sequentially – and quantitatively – determine the relative contributions of the four major mechanisms of energy balance to this total. Herein we propose that the use of metabolic caging systems and bomb calorimetry can quantify the contributions of food intake behavior and digestive efficiency (and in combination, caloric intake); if these mechanisms account for essentially all of the total change in energy flux, then the investigator can conclude that caloric intake changes explain the overall phenotype. If these mechanisms do not quantitatively account for the total energy change, then subsequent studies to explore resting metabolic rate (RMR) are required. Only after an investigator exhausts methods to assess RMR can changes in physical activity be quantitatively determined. Qualitative methods to assess physical activity are then recommended to complement the preceding quantitative methods.

2. Materials

Metabolic caging systems

One common type of metabolic caging system for use with mice is the Nalgene-style single-mouse sized metabolic cage. These cages are designed to be used with a single mouse per cage, and are treated with special coatings to maximize urine collection efficiency. Great care must be taken when washing the cages to prevent loss of the coatings by using specific soaps as recommended by the manufacturer.

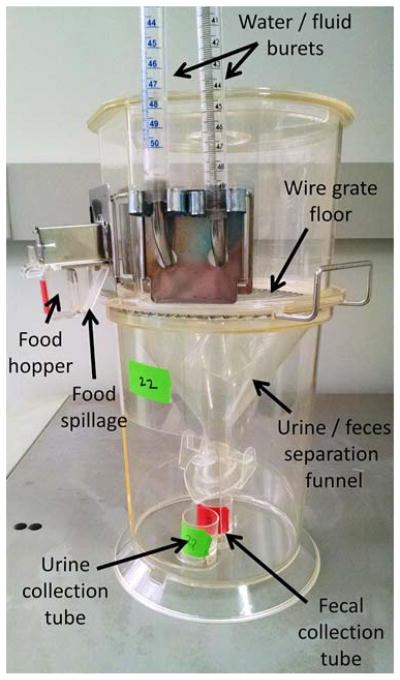

Our group has frequently utilized Techniplast USA model 3600M021 to study the effect of manipulations of the RAS upon metabolic and fluid balance physiology [3–8] (Figure 2). These cages have been modified to replace the standard water bottle with two 50 mL burets, to allow for two-bottle choice testing.

Figure 2. Illustration of one type of mouse-sized metabolic cage.

A single mouse-sized metabolic cage (Techniplast USA model 3600M021 shown) typically includes a detachable food hopper, water bottle, urine and fecal collection tubes. Cages can be modified (as shown) to provide multiple drink tubes, to permit 2-bottle choice tests.

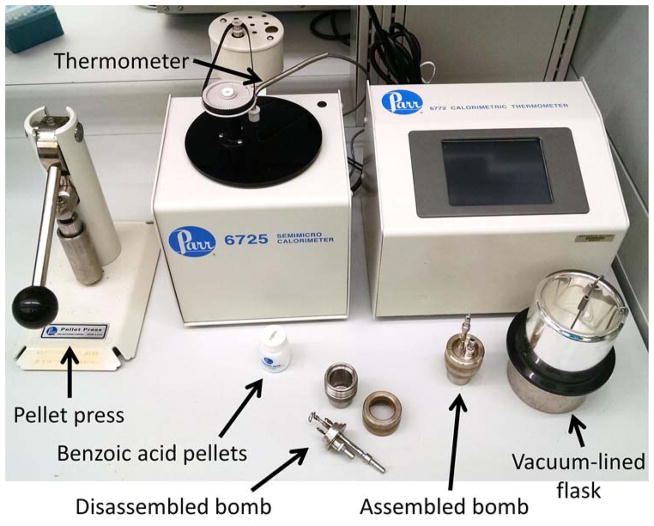

Bomb calorimeter

A bomb calorimeter of appropriate size must be selected. One commonly used design is a 25–200 milligram bomb (e.g. – Parr Instrument Company, model 6725). Importantly the investigator will need a pellet press to uniformly prepare samples for use in the bomb (e.g. – Parr Instrument Company, model 2817). We have used these models of equipment to examine digestive efficiency and energy efficiency in animals with manipulations of mitochondrial function and the gut microbiome [9,10] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Illustration of a semi-micro bomb calorimetry system.

A 25–200 milligram bomb calorimeter system (Parr model 6725 shown) consists of a bomb that is loaded with the sample pellets (prepared by a press as shown), which is then submerged in a specific volume of water within a vacuum-lined flask. The flask is then placed into the mixing chamber that includes a high-resolution thermometer in the water bath. Systems such as the Parr model 6725 perform scripted analysis runs (roughly 20 minutes per sample) and also log and analyze data for the user.

Body composition analyzer

Body composition analyzers are typically far beyond the budget of an individual laboratory, and are more typically offered through an institutional core facility. It is important to know what equipment is available in the facility, however, as occasionally the resolution of a given scanner (e.g. – a rat-sized scanner) is insufficient to accurately assess body composition of smaller species (e.g. – mice). We have used NMR and MRI scanners within core facilities at the University of Iowa in a wide array of studies of energy balance [3,11,12,8,10]. Protocols for using such equipment will be provided by core facility staff and are beyond the scope of this chapter. These analyzers typically provide bodily composition of fat mass, lean mass, and water.

Respirometry equipment

Gas analyzer equipment is available from a long list of manufacturers, including AEI Technologies, Sable Systems, and Columbus Instruments. It is again important to evaluate the specifications of the equipment under comparison based on the resolution of the analyzers for the species of animal that will be studied. Equipment to correct air flow rates to standard temperature and pressure is available from many commercial sources as well. Some manufacturers offer equipment to record data, while others require that you interface these systems with third-party chart recorder equipment (e.g. – ADInstruments). Finally, housing chambers can be obtained from some manufacturers, or custom-built. Investigators who wish to be able to expose animals to a range of ambient temperatures may consider the use of custom-modified water-jacketed chambers coupled to circulating heating/cooling water baths to provide such options.

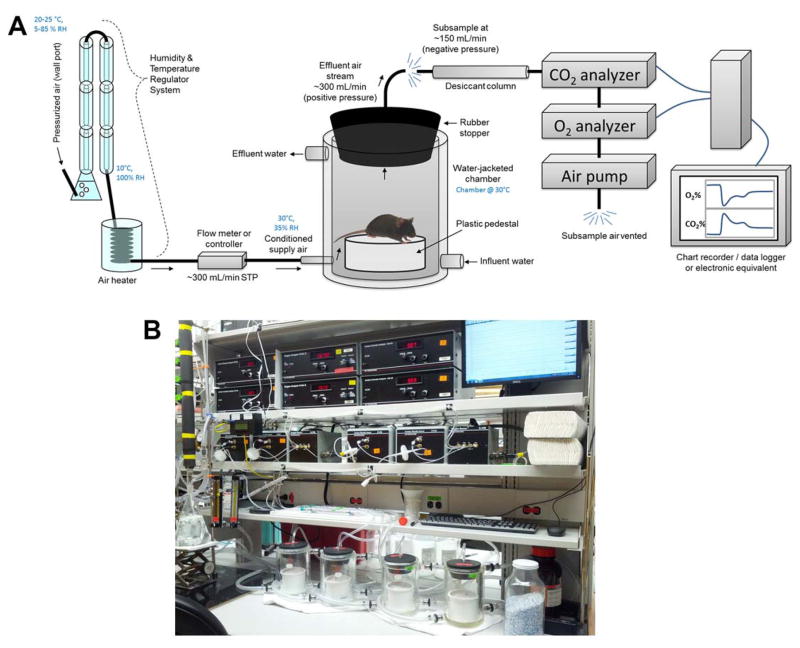

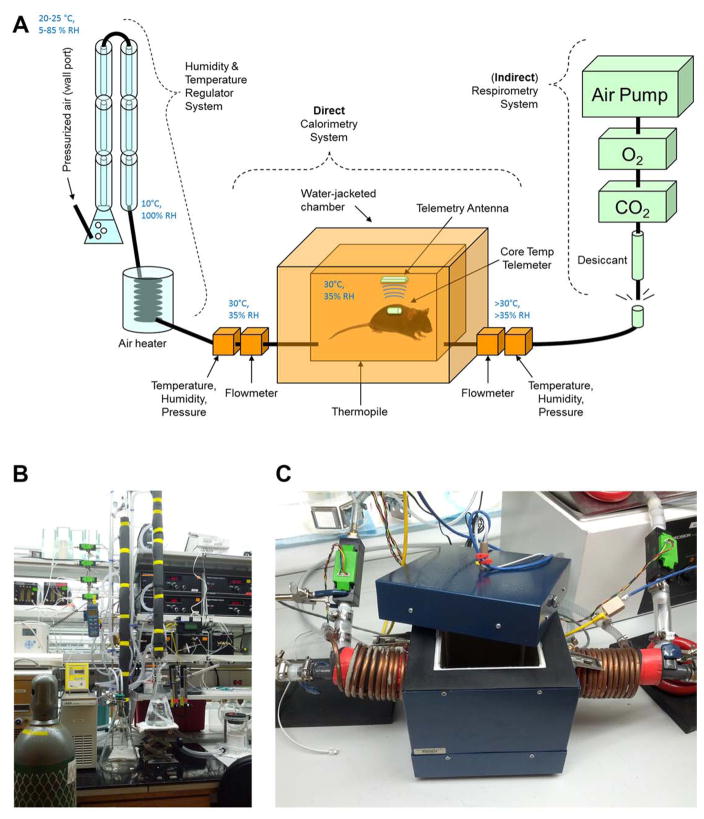

We have described a push-pull respirometry array using AEI gas analyzers and custom thermally-controlled chambers (ACE Glass, Vineyard, NJ) in multiple recent publications [3,5,13,14,7,8] (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Illustration of a simple respirometry system.

(A) A custom-fabricated push-pull continuous respirometry system such as currently in use in our laboratory is illustrated. Pressurized air from a standard laboratory supply line is passed through a humidity and temperature regulator system (explained more fully in Figure 5), and conditioned air is then passed at ~300 mL/min STP into a water-jacketed animal chamber. The animal chamber (a 2-liter custom-modified chamber from ACE Glass, Vineland, NJ) is maintained at 30°C by constant water jacket perfusion via a heated circulating water bath (not shown). Animals are placed into the chamber atop a plastic pedestal (to negate behavioral consequences of placing the animal’s thermally-sensitive paws upon the heated glass). Air exits the chamber via a port drilled through a tight-fitting rubber stopper that is seated in the mouth of the beaker. Effluent air is then subsampled by a respirometry system, including a desiccant column (anhydrous calcium sulfate / Drierite), a CO2 analyzer, O2 analyzer, and finally the air pump that pulls subsampled air through the system. Data from the analyzers is then logged on a chart recorder. (B) A photograph of a 4-chamber continuous respirometry system current in use in our laboratory.

Comprehensive phenotyping systems

Several companies offer “comprehensive” phenotyping equipment (e.g. “OxyMax/CLAMS” from Columbus Instruments, “Promethion” from Sable Systems, “PhenoMaster” from TSE). These combinatorial systems allow simultaneous assessment of food intake, respiratory gas exchange, physical activity by beam break, and core temperature via implanted telemeters. Such systems offer repeated, longitudinal assessments of various phenotypes throughout the circadian cycle but generally fail to include mechanisms to assess all aspects of energy balance by ignoring digestive efficiency and anaerobic metabolism. Using an OxyMax/CLAMS system available through core facilities at the University of Iowa, we have published studies using this system to investigate the effects of dietary sodium and the RAS upon energy balance [8].

Direct calorimetry equipment

There are currently no commercial sources of direct calorimetry equipment for use with rodents for biomedical research. Various groups have described the custom fabrication of direct calorimetry chambers and coupling these chambers to respirometry equipment to generate “total” or “combined” calorimeter equipment [15–18,11,19,12]. While the adoption of such equipment by the field is very strongly recommended, the fabrication, optimization, validation and use of such equipment is well beyond the current article. Any laboratory planning to develop such equipment is strongly advised to employ a professional electrical and biomedical engineer.

The combined calorimeter system currently operational in our laboratory (Figure 5), which was custom fabricated by Colin M.L. Burnett, MD, MS, is thoroughly described in several recent publications [11,12,8,10]. Briefly, conditioned air (Note 1) is analyzed for flow, temperature, humidity, and pressure to calculate the enthalpy of air entering the chamber. Heat dissipated by the subject passes through thermopiles that line the interior walls of a water-jacketed chamber, which generates a proportional voltage that is recorded. Flow, temperature, humidity, and pressure are then again measured in effluent air to determine its enthalpy. In addition, core body temperature is recorded using surgically implanted telemeters and a custom miniaturized receiver antenna inside the chamber (Data Sciences International). Effluent air is then sub-sampled (i.e. flow is less than through the chamber) by a standard respirometry system as above.

Figure 5. Illustration of a combined / total calorimeter.

(A) A custom-fabricated combined calorimeter system is illustrated. First, pressurized air (of uncontrolled humidity and temperature) from a standard laboratory supply line is passed through a humidity & temperature regulator system to supply a constant stream of 30°C / ~35% RH / 300 mL/min STP air to the chamber (see Note 1). Enthalpy of the influent and effluent air streams is calculated by measuring flow, temperature, humidity, and pressure. Heat radiated into the walls of the chamber is determined from the voltage generated by thermopiles that line the interior walls of the water-jacketed chamber. Core body temperature is recorded continuously by radiotelemetric probe. Effluent air is then passed to a respirometry system, as above. (B) A photograph of the humidity and temperature regulator system current in use in our laboratory. (C) A photograph of the gradient-layer direct calorimetry chamber currently in use in our laboratory.

3. Methods

Method 1: Metabolic caging systems

When an experimental manipulation results in a change in body mass, one simple and superior method to investigate energy balance is to use metabolic caging systems to quantitatively assess food intake. While some investigators prefer to examine food intake behavior in home cages to minimize behavioral interruptions due to neophobia, it is virtually impossible to quantify food intake with high resolution in this setting due to the loss of spilled food dust into bedding materials. Subsequently, food intake in home cages is often reported at higher rates than in metabolic caging systems, but the relative contribution of neophobia-induced anorexia versus food spillage to this difference is impossible to distinguish. Further, mice often consume bedding materials and therefore the caloric content of this additional ‘food’ source is impossible to quantify. (Also, regardless of the caloric value of the bedding material, consumption of that material may also have unexpected consequences on the gut microbiome and thereby energy balance control.) Therefore, we prefer to consistently use metabolic caging systems, but acknowledge the need for explicit training of the animals to minimize the influence of neophobia upon food intake behavior.

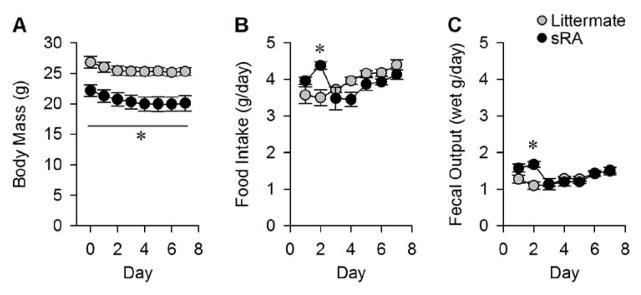

Metabolic caging systems (whether commercial or custom-fabricated) typically include a food hopper and fluid delivery system that minimizes spillage of food and drink solutions, and a wire mesh or metal grate floor which allows for efficient and quantitative collection of both urine and fecal samples. Animals should be placed into caging systems for several days to acclimate (see Note 2) before measurements are performed. Following acclimation, the investigator can measure food intake (mass change of food hopper) and fecal output (mass change of fecal collection tube) daily for several consecutive days. In our laboratory, we typically use at least 48–72 hours of acclimation as our previous studies have demonstrated the instability of body mass, food intake, and feces production when animals are acclimated for shorter periods (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Example empirical determination of required acclimation time for metabolic caging systems.

It is necessary for investigators to empirically determine the requisite acclimation phase for animals in metabolic cages, as acclimation needs can wildly vary based on an array of environmental and animal-specific factors. In this example, double-transgenic “sRA” mice, which exhibit brain-specific hyperactivity of the RAS [3,6,34] and their phenotypically normal single- and non-transgenic littermates, were placed into Nalgene-style single-mouse metabolic cages for seven consecutive days and allowed ad libitum access to Teklad 7013 chow and water. *P<0.05 vs control at indicated timepoint by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple-comparisons procedure.

On a daily basis the investigator should record the animal’s body mass, the end masses/volumes for food, water, urine and feces. Then after resetting the cage, tare masses/volumes for food, water, urine and feces should again be recorded. Date, time of cage servicing, room temperature and humidity, and operator are also critical information to record for future reference (see Table 2 for an example data recording sheet; notably on day 0 there will be no “end” masses/volumes, and on the last day of study there will be no “tare” values). Seasonal variations in ambient temperature and humidity can have major effects on fluid intake behavior and urine production in addition to the rates of evaporation of urine from the collection tube. Evaporation rates can either be determined by daily recordings of the mass of water lost from a water-filled tube kept in the animal room, or controlled by placing a small amount of oil in the urine collection tube to ‘trap’ the aqueous urine layer and prevent its evaporation.

Table 2.

Example daily log sheet for metabolic cage studies.

| Date: __________ | Technician: ___________________ | Room Temperature:_______________ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time: __________ | Room Humidity:_______________ | |||||||||

| Cage # | Animal | Body (g) | End Food (g) | End Water (g or mL) | End Urine (g) | End Feces (g) | Tare Food (g) | Tare Water (g or mL) | Tare Urine (g) | Tare Feces (g) |

Using metabolic caging systems or home cage systems, the investigator can immediately calculate food intake behavior from these data. Using the caloric density of the food (which can be found on the dietary information specifications supplied by the manufacturer), the investigator can then easily calculate the total calories consumed daily by the animal per day (Equation 1):

| Equation 1 |

Using bomb calorimetry methods detailed below, we have determined that the batch-to-batch variability of caloric density of standard chow and high fat diets from various manufacturers is appreciable. Thus, while the use of a published caloric density is a good starting point, we recommend the routine analysis of the caloric density of individual batches of food for quantitative studies of energy balance using bomb calorimetric methods.

Method 2: Bomb calorimetry

By carefully and analytically collecting the feces produced by an animal per unit time, the investigator can then perform a series of tests to qualitatively or quantitatively assess digestive efficiency and caloric absorption. Various methods including fecal acid steatocrit (see Note 3) or other metabolomics methods can be employed to qualitatively determine whether animals are exhibiting changes in the absorbance rates of fatty acids or other metabolites. To quantitatively assess digestive efficiency and caloric absorption, however, bomb calorimetry is the gold standard. Its less-than-universal use in animal physiology laboratories may stem from the perceived complexity of this physical / analytical chemistry method, or simply from unpalatable but necessary handling and use of feces.

Bomb calorimetry is a methodology that is easily adaptable for use in physiological studies. In essence, this method allows for the determination of the caloric density of a sample material (please see Note 4). After an investigator quantitatively collects feces from study animals via metabolic caging systems (this is extremely difficult to do if the investigator uses home cages), the fecal samples are desiccated. It is critical to calculate the “wet” mass of the feces before desiccation and the “dry” mass after drying. This allows the investigator to calculate the water content of the feces, which may be an endpoint of interest in its own right. Further, it is necessary to know the contribution of “dry” mass to “wet” mass to ultimately calculate digestive efficiency. Desiccated fecal samples are then pressed into pellets, and the pellet mass is carefully determined. It is important to use high-resolution balances for all steps, as significant digit and error propagation issues can become unwieldy after sequential mathematical calculations. Further, the use of an appropriately-sized bomb calorimeter is required (see Note 5).

Fecal samples are then burned to completion in the bomb calorimeter according to the protocol of the individual calorimeter. Typically, the sample is loaded into the bomb along with fuse wire, the bomb is pressurized with pure oxygen, and the bomb is submerged into a known volume of water within a well-insulated container. A very high-resolution thermometer is placed into the water bath, and some kind of water circulating system (such as a paddle wheel or turbine) is submerged and activated. After a suitable thermal stabilization phase, which is subject to ambient conditions and the material composition of various equipment components involved, an electrical current is passed through the bomb’s fuse wire and the fecal sample is rapidly combusted to completion. The energy from the combustion is transferred into the water bath, and the resulting temperature change in the water is noted by the thermometer. Having previously calibrated the thermometer system by combusting known masses of pure fuels (e.g. benzoic acid) according to bomb manufacturer’s protocol, the user can then calculate the caloric release from the feces. Using that value and the known mass of the fecal pellet that was burned, the investigator can determine the caloric density of the desiccated fecal sample (Equation 2):

| Equation 2 |

Once the investigator has determined the caloric density of a desiccated fecal sample, he or she can then calculate the caloric density of the original fecal sample (Equation 3):

| Equation 3 |

Once the caloric density of the original sample has been determined, it is simple to calculate the total daily caloric loss to feces (Equation 4):

| Equation 4 |

Next, the investigator can then calculate total daily caloric absorption using the total calories consumed daily (Equation 1) and the total daily caloric loss to feces (Equation 4) by simple subtraction (Equation 5):

| Equation 5 |

Total daily caloric absorption is an important value to consider by itself, and the investigator should consider this value as more important to total energy balance than the calories consumed, as ultimately the net energy balance is subject to the balance between calories absorbed versus expended.

In addition to total caloric absorption, bomb calorimetry data can be used to calculate digestive efficiency. Digestive efficiency is subject to many different biological mechanisms (mechanics of the gastrointestinal tract, hepatic and pancreatic function, disease states, etc.), but from an energetics perspective these individual mechanisms are only of interest if there is a change in net absorption efficiency. Digestive efficiency simply reflects the fraction of calories absorbed from total calories consumed (Equation 6):

| Equation 6 |

Finally, the results of bomb calorimetry can also be used to estimate the relative importance of changes in energy intake versus output in observed changes in body mass. Energy efficiency is a term for the amount of weight gain exhibited by an animal per calorie absorbed over a given period of time (Equation 7):

| Equation 7 |

Energy efficiency is typically calculated for each of several treatment groups that were matched under baseline conditions (such as before initiation of an experimental diet). For example, after treating two groups of mice with chow or a 45% high fat diet for 28 days, bomb calorimetry is used to calculate the daily caloric absorption of each animal. For each mouse, energy efficiency is calculated as the weight gained over the 28 days, divided by the total calories absorbed over the 28 days (i.e. – the daily absorption x 28 days). A positive deflection is expected in the mice fed the high fat diet, which would be interpreted as an increase in weight gained for any individual calorie that was absorbed. If the two groups of animals exhibited similar total daily caloric absorption but differences in energy efficiency (e.g. – increased with high fat feeding), then the investigator can conclude that the increased weight gain is due primarily to a reduction in energy expenditure. While the conclusion may seem obvious (e.g. – the same calories were absorbed, but one group got larger), the use of this methodology can quantify the effect over multiple time points, which can be used to illustrate the effect of serial treatments or compensatory changes in the animal groups. Further, this methodology allows the investigator to mathematically describe the relationship.

Method 3: Body composition

Many laboratories now have access to core facilities that are equipped with sophisticated body composition analyzers. These analyzers come in multiple forms, including dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and each type of technology sports relative benefits and trade-offs. DEXA scanners use x-ray technology to assess lean, fat, and bone masses, and can be used with animals that have metal implants such as implanted minipumps for drug delivery. NMR equipment provides rapid and highly quantitative assessments of lean, fat, and fluid masses, though animals instrumented with metal implants cannot be analyzed in these systems. MRI equipment uses essentially the same methodology as NMR equipment, but is more commonly used for providing images to illustrate body composition rather than simply quantifying body composition. Regardless of method, animals must be either anesthetized or restrained to prevent movement during scanning.

Use of these various methods can provide substantial insight into the effects of treatments upon the subject, as serial, longitudinal measures within an individual can be performed (i.e. baseline and post-treatment values within subject can be easily captured and compared). In addition, data from these types of analyses can be used in conjunction with bomb calorimetry methods to further estimate the contribution of various energy-balance mechanisms to weight gain. For example, lean tissue is generally estimated to have a caloric value of approximately 4 kcal/g, while fat tissue is estimated to have a caloric value of 9 kcal/g. If an animal gains 1 gram each of fat and lean tissues, then the investigator is left to account for 13 kcal of increased energy intake/absorption or reduced energy expenditure. If the animal absorbed an additional 10 kcal during the experimental period, then the investigator can roughly estimate that 77% of the extra weight gain was a result of increased caloric absorption (i.e. 10 kcal absorbed, divided by 13 kcal total). By extension, 23% of the extra weight gain (3 of the 13 kcal) likely resulted from reduced energy expenditure.

Method 4: Physical activity methods

One of the mechanisms of energy expenditure available to any animal is spontaneous physical activity, though physical activity for a typical human accounts for only 0–40% of total daily energy expenditure. Various methods have been developed to estimate physical activity in rodents, including systems which quantify distance travelled by photoelectric beam interruption (“beam breaks”), running wheel revolutions, and systems that track proximity between radiotelemetric transmitter implants and stationary receiver antennas.

It is critical to appreciate that all methods used to assess the caloric value of physical activity are qualitative. This is due to the wide array of variables that contribute to the energy equivalency of any given physical motion. As a result, the relationship between recorded motion by an animal and the caloric expenditure is of a multivariate form. For example, if a human weighing 70 kg walks up two flights of stairs and a 140 kg human walks up one flight of stairs, it is essentially impossible to calculate how much energy was spent by each subject, and which subject spent more energy. Body composition, exercise conditioning and capacity, muscle efficiency, blood chemistry, feeding status, disease state, height, altitude, ambient temperature, relative humidity, etc. all contribute to the final energy expenditure required by each subject to perform a given motion. Thus, while the above systems can provide critical qualitative insights into circadian rhythms of activity or gross changes in total activity between treatment groups, it remains impossible to calculate energetic equivalents of these motions. Instead, caloric equivalents of any given amount of physical activity are instead typically calculated as the remaining balance between total calories expended (calculated by bomb calorimetry) and calories expended via resting metabolism (Figure 1).

Method 5: Aerobic resting metabolism method – respirometry

Resting metabolic rate (RMR) refers to the energy expended by a body when resting. Typically this refers to an animal that is stationary, awake, and calm but not sleeping, though it is difficult to dissociate “resting” from “sleeping” bouts in rodent species. RMR typically accounts for 60–100% of total energy expenditure, and it is often assessed using respirometric methods due to the availability high-quality “turn-key” commercial systems [20–22].

Respirometry is one form of “indirect calorimetry,” which is a catch-all term describing a collection of methods that estimate metabolic rate by measuring some simple surrogate. For example, “indirect calorimetry” methods also include methods such as isotope dilution. In the case of respirometry, metabolic rate is estimated by measuring respiratory gas exchange. As early as 1928, Lusk published a table of coefficients that related the amount of heat generated per volume oxygen consumed by a combustion reaction of mixtures of fats and carbohydrates [23]. (Popularized by Lusk, this table represented a corrected version of such a table published by Zuntz and Schumburgin [24].) Relatively simple algebraic regressions of these interpolated data lead to an equation to relate rates of oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) to heat production [20,21], which are calculated from the changes in air O2 and CO2 content as it passes a live animal (with flow rates measured and corrected for standard temperature and pressure, STP), and many investigators and commercial equipment use this equation to estimate metabolic rate (Equations 8–10):

| Equation 8 |

| Equation 9 |

| Equation 10 |

This equation and other similar equations are used by virtually every commercial respirometry-based system, be it a standalone system or part of a comprehensive monitoring system. Respirometry systems can be in many forms [20] (see Note 6), but many investigators utilize “push-pull” design systems, where air of known composition is “pushed” through an air-tight testing chamber, and effluent air is “pulled” into a subsampling system including a desiccant system to dry the air, then through oxygen and carbon dioxide analyzers. Testing chambers can be maintained at any desired temperature, though assessments of resting metabolism are typically performed at thermoneutral temperatures (e.g. ~30°C for mice [25]) both to promote “resting” behavior and also to minimize adaptive thermogenic mechanism (e.g. sweating, licking, shivering) activation. Various publications have demonstrated that the thermoneutral zone for wildtype C57BL/6 mice is between 26–34°C [25], and therefore most investigators use an ambient/chamber temperature of 30°C for measurements of RMR. Although perhaps not immediately obvious, it is also important that air flow through such systems must be corrected to standard temperature and pressure (STP) for calculations of metabolic rate, and any custom-fabricated systems must be designed to make this correction. This is necessary because an air flow of, say, 100 mL per hour will not be the same mass of air if it were at a different temperature or pressure.

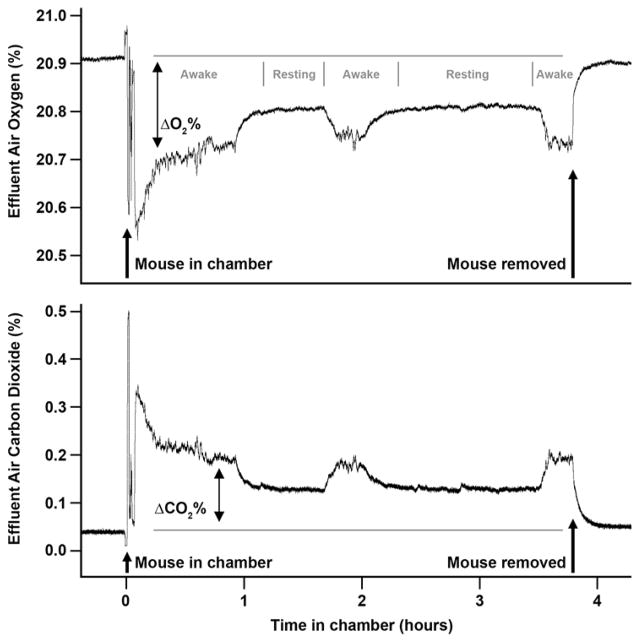

RMR measures must be taken while animals are “resting.” Investigators can ensure that animals are resting via visual inspection (either in person or via video camera so as to not disturb the resting animal), or more simply by tracking oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production rates in real-time. Whereas awake and moving animals exhibit highly variable second-to-second rates, resting/sleeping animals will achieve a low, steady plateau of rates that are easily noted in strip charts or electronic equivalents (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Example real-time tracing of oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production by a mouse.

A typical recording session of a mouse placed into a push-pull respirometer system, with chamber temperature maintained at 30°C and with air flowing through the chamber at ~300 mL/min STP. The oxygen consumption rate (ΔO2%; reflected in a downward deflection in effluent O2 content) and carbon dioxide production rate (ΔCO2%; reflected in an upward deflection in effluent CO2 content) can be determined both during bouts of wakefulness (Awake) and during periods of rest (Resting). Periods of rest are easily identified in tracings of effluent air composition as periods of steady, minimum-value plateaus in both ΔO2% and ΔCO2% endpoints. Aerobic metabolic rate is then calculated using equations 8–10, and aerobic RMR simply reflects the output of these calculations when inputting ΔO2% and ΔCO2% values recorded during periods of rest.

Method 6: Total resting metabolism method – direct calorimetry

It is very important to note that by definition, respirometry is limited to assessments of oxygen-dependent (i.e. aerobic) metabolism. In fact, the use of respirometry relies upon several untested / untestable assumptions which most users ignore [22]. Growing evidence now supports the conclusion that the tacit assumption that anaerobic processes are both negligible and constant is simply wrong. Our group and others have demonstrated that anaerobic processes appear to contribute large, variable fractions of total RMR in various species using “combined calorimetry” or “total calorimetry” methods, which are described below. Walsberg and Hoffman [17,18] demonstrated that anaerobic processes contribute 0–40% of total RMR in snakes, birds, and kangaroo rats. Pittet et al. [15,16] demonstrated that in lean humans, anaerobic processes contribute nearly 10% of total RMR, while they contribute essentially 0% in obese humans. Van Breukelen’s group has also started investigating these processes in desert and aquatic species and in the context of torpor [26,19,27–29]. Our group has determined that in laboratory mice, anaerobic RMR contributes around 10% of total RMR, and that this contribution can be suppressed or stimulated by various genetic (e.g. disruption of the angiotensin AT2 receptor), pharmacological (anesthesia), dietary (high fat diet), and microbial (risperidone) interventions [11,12,8,10]. Thus, there is a major need for the field to adopt methods that can measure the entire range of processes (aerobic and anaerobic) contributing to RMR [22,30].

At the chemical level, metabolic rate is the rate of heat production. In steady-state, the rate of heat production by an animal is equivalent to the rate of heat release from the body. Thus, “direct” calorimetry describes methods that measure heat dissipation to calculate metabolic rate. There are currently no commercial sources for direct calorimetry systems for rodents, though several groups have described simplified [19] and more elaborate [11,22] systems with a range of capabilities and resolutions which can be used for rodents of various sizes. Critically, the investigator must insert/implant a core temperature probe within the animal to either ensure that measurements are performed while the animal is at steady state (indicated by a stable core temperature) or to correct direct calorimeter data for the rate of core temperature change, using complicated equations that depend upon knowledge of the subject’s exact body composition [31].

As air must be fluxed through the calorimeter chamber of a direct calorimeter for the animal, it is straightforward to simply subsample effluent air from a direct calorimeter and perform respirometric measurements to simultaneously measure aerobic metabolic rate. Using such a “combined calorimetry” or “total calorimetry” setup, the investigator can measure total metabolic rate (via direct calorimetry) and aerobic metabolic rate (via respirometry). The difference between these methods, therefore, reflects the anaerobic metabolic rate.

Use of a combined calorimeter is essentially identical to the use of a respirometer system. The testing chamber is maintained at an experimentally-dictated temperature (typically thermoneutrality), and the heat production / release within the box and the composition and flow rate of the air fluxing through the box are determined while the animal is in the box and at rest, compared to when the animal is not in the box.

Method 7: Putting it all together

As described in the above sections, quantitative evaluations of energy flux in a mouse (or any animal subject) can be efficiently performed using metabolic caging systems and a bomb calorimeter. Additional dissection of the contribution of resting metabolic processes versus physical activity requires far more sophisticated methodologies that are not as commonly (or inexpensively) available. By multiplexing these various methods, however, it is possible to comprehensively evaluate all aspects of energy balance in the animal, and to specifically attribute the relative importance of individual mechanisms to the net changes in body mass (Figure 1).

Metabolic caging and bomb calorimetry allows the investigator to evaluate caloric intake, absorption, digestive efficiency, and energy efficiency. These methods directly address the contributions of food intake and gastrointestinal function to energy balance. By additionally utilizing body composition analysis methods, investigators can illustrate the relative importance of observed processes to weight gain/loss, compared to what is expected based on changes in body composition. By using quantitative measures of resting metabolism (both aerobic and anaerobic), investigators can then determine the contributions of these processes to total energy balance, and finally by simple subtraction, remaining calories are most easily ascribed to physical activity. Such designations can be complemented / confirmed by qualitative methods of assessing physical activity behavior.

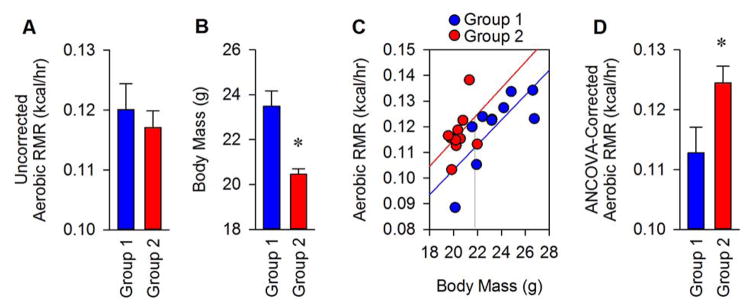

Method 8: Statistical considerations

Substantial discussion has raged in the literature over the last decade with regard to the most appropriate way to compare metabolic phenotyping data across subjects of differing body size / body mass / body composition. Of course a larger animal would be expected to eat more food, but documenting a larger food intake in a larger animal does not necessarily indicate that the greater food intake preceded or caused the additional weight gain. As explained in other recent review articles, investigators often normalize data by simply dividing food intake or RMR data by body mass, but from both mathematical and biological perspectives this approach is untenable. Instead, more reasonable solutions to this problem have been proposed to include either simply reporting all of the data (such that the reader is left to draw their own conclusions), or to account for differences in subject body mass using the ANCOVA statistical correction method [32].

As an oversimplification, ANCOVA analyses involve performing linear regressions of metabolic rate (or food intake, etc.) versus body mass data pairs. One assumes (and tests) that the slopes of the lines which best describe data from each treatment group are indistinguishable, and then a comparison of the two groups at a single average value for body mass is made (Figure 8). Statistical packages are available commercially which can perform one-way ANCOVA, or various online calculators for free (see Note 7). Univariate regression modeling must be used if more than one variable is considered.

Figure 8. Illustration of an ANCOVA analysis.

(A) A simple comparison between two different groups indicates no difference in mean aerobic RMR between groups. (B) Comparison of body masses between groups uncovers a difference between groups, necessitating the reanalysis of RMR data to account for body size. (C) Metabolic rate values are plotted against the body mass of individual animals within each group, and linear regressions are performed for each group. Tests of homogeneity of regression are performed to confirm that the slope of lines through each group are indistinguishable. (In this case the lines are indistinguishable, p=0.96, so we can proceed with ANCOVA analyses). (D) The interpolated average RMR value (intercept) at the average body mass value for all animals in the study (21.97g) is then reported as the “ANCOVA-corrected” RMR value.

Acknowledgments

The Grobe laboratory is supported by grants from the NIH (HL084207), the American Diabetes Association (1-14-BS-079), the American Heart Association (15SFRN23730000), the University of Iowa Office of the Vice President for Research and Economic Development, and the Fraternal Order of Eagles’ Diabetes Research Center. Some of the equipment illustrated was purchased with support from the Roy J. Carver Trust. Connie C. Grobe, PhD, Jeremy A. Sandgren, John R. Kirby, PhD and Colin M.L. Burnett, MD, MS provided critical revisions of the chapter text.

Footnotes

Air conditioning system. To control ambient air temperature and humidity for subject animals in calorimeter systems throughout various seasons, a simple system that controls the dew point of the air stream can be used. Water is bubbled through room-temperature water to saturate the air (i.e. 100% relative humidity). This air is then passed through condenser columns maintained by a chilled circulating water bath thereby “setting” the dew point of the air stream. Warming this air maintains the quantity of water vapor and reduces the relative humidity For example, setting the chilled water to 10°C and warming to 30°C results in a relative humidity of about 35%. Air flow through this conditioner system can be controlled by modulating the pressure supplied to the system.

Acclimation to metabolic caging systems. Because of the neophobia exhibited by rodents, animals will often exhibit abnormal behaviors (and by extension, energy balance) for between one and seven days when placed into metabolic caging systems. Users should empirically determine the acclimation period required for animals in their laboratory, as acclimation needs can differ depending upon the animal strain and the complexity of the caging system. For example, in our laboratory we have repeatedly determined that food and water intake, urine and fecal production all drop over the first 24–96 hours that C57BL/6J mice and transgenic mice on this background are placed into Nalgene-style single-mouse sized metabolic cages when housed at 22–25°C with 30–70% relative humidity, but that intake and output behaviors rebound and achieve a steady plateau after 72–96 hours (Figure 5). In contrast, other laboratories insist upon (based on various levels and types of evidence) waiting up to 7 days of acclimation. We advocate empirical determinations in each laboratory to gain confidence in one’s own data.

Fecal Acid Steatocrit method. Fatty acid content of feces can be assessed using a very simple biochemical method [33,8]. Briefly, a known mass of desiccated feces (e.g. – 50 mg) is reconstituted in freshly prepared perchloric acid (200 microliters of 1 N). After reconstitution, a small amount of oil-red-O stain (100 microliters of 0.5%) is then added to the slurry. The slurry is then loaded in a capillary tube and centrifuged. The layer stained with oil-red-O is then compared (as a percentage) against the entire column in a very similar method to determining the hematocrit of blood. Relative increases or decreases in the contribution of this layer to the total column height reflect decreases or increases, respectively, in fatty acid absorption efficiency. That is, an increase in steatocrit means a decrease in absorption. This qualitative method provides some insight into digestive efficiency, but because it is impossible to determine the caloric value of the fatty acid species present and the value of the other, non-fat components in the feces, this method often serves as only a screening tool or qualitative complement to bomb calorimetric methods. Notably, we have found that when animals are maintained on a chow diet the fatty acid content of the stool is very low and it is difficult to discern changes by this method. In contrast, when animals are maintained on high fat diets (45 or 60%), changes in fatty acid absorption are easy to detect by this method.

Analyses of caloric density. It is worth noting that analyses of caloric density using a bomb calorimeter ignore the bioavailability of calories in a sample. For example, a chow-based diet typically contains some amount of undigestible fiber, yet combustion of that food sample in a bomb calorimeter will yield a caloric density including calories from both the digestible and undigestible components. Ultimately if calculations are performed correctly this will not matter as the same undigestible materials are represented in feces, and the same constant value is present in both the consumed and fecal masses. Subtraction of fecal calories from consumed calories (Equation 5) therefore yields the same value for total daily caloric absorption as this constant is subtracted from itself.

Choosing an appropriately-sized bomb calorimeter. A single mouse can be expected to reliably produce ~100 mg of desiccated fecal sample per day, so use of an appropriately-sized bomb is necessary. For example, use of a bomb which requires 1 gram of sample would necessitate combining fecal samples from 10 individual mice or serially collecting fecal samples from a single mouse for 10 consecutive days. In contrast, a bomb which requires 25–200 mg of sample is suitable to analyze samples from single-day collections from individual mice.

Continuous versus discontinuous sampling respirometers. Many multi-chamber metabolic monitoring systems are available commercially through an array of companies including Columbus Instruments, Sable Systems, TSE, etc. Some of these systems make use of continuous-recording respirometer arrays in which each cage has a dedicated pair of oxygen and carbon dioxide analyzers continuously analyzing effluent air; such systems are analogous to the system described herein. In contrast, some systems keep costs down by using an automated sampling manifold such that one single analyzer pair is used for a number of chambers. This second, discontinuous-type system samples effluent air from each of several cages for a few seconds every few minutes to provide a survey of metabolic rate values across time. As a result, the addition of more chambers to such a discontinuous system reduces the sampling frequency. As sampling time points are separated, it becomes increasingly difficult to interpret bouts of rest. Therefore for assessments specifically of RMR (as opposed to simply metabolic rate in general), we have had much greater success using a continuous-sampling system as illustrated in Figure 5.

Online calculator for ANCOVA. One free source for one-way ANCOVA analyses can be found at: http://vassarstats.net/. It is important to note that if more than one independent variable is in play, that univariate regression methods must be used instead of the simple ANCOVA method.

References

- 1.Littlejohn NK, Grobe JL. Opposing tissue-specific roles of angiotensin in the pathogenesis of obesity, and implications for obesity-related hypertension. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2015;309(12):R1463–1473. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00224.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall KD, Sacks G, Chandramohan D, Chow CC, Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA. Quantification of the effect of energy imbalance on bodyweight. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):826–837. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60812-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grobe JL, Grobe CL, Beltz TG, Westphal SG, Morgan DA, Xu D, de Lange WJ, Li H, Sakai K, Thedens DR, Cassis LA, Rahmouni K, Mark AL, Johnson AK, Sigmund CD. The brain Renin-angiotensin system controls divergent efferent mechanisms to regulate fluid and energy balance. Cell metabolism. 2010;12(5):431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grobe JL, Dickson ME, Park S, Davis DR, Born EJ, Sigmund CD. Cardiovascular consequences of genetic variation at -6/235 in human angiotensinogen using “humanized” gene-targeted mice. Hypertension. 2010;56(5):981–987. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.110.157354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grobe JL, Buehrer BA, Hilzendeger AM, Liu X, Davis DR, Xu D, Sigmund CD. Angiotensinergic signaling in the brain mediates metabolic effects of deoxycorticosterone (DOCA)-salt in C57 mice. Hypertension. 2011;57(3):600–607. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.110.165829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Littlejohn NK, Siel RB, Jr, Ketsawatsomkron P, Pelham CJ, Pearson NA, Hilzendeger AM, Buehrer BA, Weidemann BJ, Li H, Davis DR, Thompson AP, Liu X, Cassell MD, Sigmund CD, Grobe JL. Hypertension in mice with transgenic activation of the brain renin-angiotensin system is vasopressin dependent. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2013;304(10):R818–828. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00082.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grobe JL, Rahmouni K, Liu X, Sigmund CD. Metabolic rate regulation by the renin-angiotensin system: brain vs. body. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology. 2013;465(1):167–175. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1096-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weidemann BJ, Voong S, Morales-Santiago FI, Kahn MZ, Ni J, Littlejohn NK, Claflin KE, Burnett CM, Pearson NA, Lutter ML, Grobe JL. Dietary Sodium Suppresses Digestive Efficiency via the Renin-Angiotensin System. Scientific reports. 2015;5:11123. doi: 10.1038/srep11123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fink BD, Herlein JA, Guo DF, Kulkarni C, Weidemann BJ, Yu L, Grobe JL, Rahmouni K, Kerns RJ, Sivitz WI. A mitochondrial-targeted coenzyme q analog prevents weight gain and ameliorates hepatic dysfunction in high-fat-fed mice. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2014;351(3):699–708. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.219329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahr SM, Weidemann BJ, Castro AN, Walsh JW, deLeon O, Burnett CM, Pearson NA, Murry DJ, Grobe JL, Kirby JR. Risperidone-induced weight gain is mediated through shifts in the gut microbiome and suppression of energy expenditure. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(11):1725–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnett CM, Grobe JL. Direct calorimetry identifies deficiencies in respirometry for the determination of resting metabolic rate in C57Bl/6 and FVB mice. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;305(7):E916–924. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00387.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnett CM, Grobe JL. Dietary effects on resting metabolic rate in C57BL/6 mice are differentially detected by indirect (O2/CO2 respirometry) and direct calorimetry. Molecular metabolism. 2014;3(4):460–464. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu D, Borges GR, Davis DR, Agassandian K, Sequeira Lopez ML, Gomez RA, Cassell MD, Grobe JL, Sigmund CD. Neuron- or glial-specific ablation of secreted renin does not affect renal renin, baseline arterial pressure, or metabolism. Physiological genomics. 2011;43(6):286–294. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00208.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilzendeger AM, Cassell MD, Davis DR, Stauss HM, Mark AL, Grobe JL, Sigmund CD. Angiotensin type 1a receptors in the subfornical organ are required for deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;61(3):716–722. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.111.00356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pittet P, Gygax PH, Jequier E. Thermic effect of glucose and amino acids in man studied by direct and indirect calorimetry. The British journal of nutrition. 1974;31(3):343–349. doi: 10.1079/bjn19740042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pittet P, Chappuis P, Acheson K, De Techtermann F, Jequier E. Thermic effect of glucose in obese subjects studied by direct and indirect calorimetry. The British journal of nutrition. 1976;35(2):281–292. doi: 10.1079/bjn19760033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsberg GE, Hoffman TC. Direct calorimetry reveals large errors in respirometric estimates of energy expenditure. The Journal of experimental biology. 2005;208(Pt 6):1035–1043. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsberg GE, Hoffman TC. Using direct calorimetry to test the accuracy of indirect calorimetry in an ectotherm. Physiological and biochemical zoology : PBZ. 2006;79(4):830–835. doi: 10.1086/505514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burger M, van Breukelen F. Construction of a low cost and highly sensitive direct heat calorimeter suitable for estimating metabolic rate in small animals. Journal of Thermal Biology. 2013;38(8):508–512. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2013.09.002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lighton JRB. Measuring Metabolic Rates : A Manual for Scientists: A Manual for Scientists. Oxford University Press; USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLean JA, Tobin G. Animal and Human Calorimetry. Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaiyala KJ, Ramsay DS. Direct animal calorimetry, the underused gold standard for quantifying the fire of life. Comparative biochemistry and physiology Part A, Molecular & integrative physiology. 2011;158(3):252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lusk G. The elements of the science of nutrition. 4. W.B. Saunders Company; Philadelphia, PA: 1928. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuntz N, Schumburg . Studien zu einer Physiologie des Marsches. Berlin: 1901. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maloney SK, Fuller A, Mitchell D, Gordon C, Overton JM. Translating animal model research: does it matter that our rodents are cold? Physiology (Bethesda) 2014;29(6):413–420. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00029.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Utz JC, Velickovska V, Shmereva A, van Breukelen F. Temporal and temperature effects on the maximum rate of rewarming from hibernation. Journal of Thermal Biology. 2007;32(5):276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2007.02.002. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Utz JC, van Breukelen F. Prematurely induced arousal from hibernation alters key aspects of warming in golden-mantled ground squirrels, Callospermophilus lateralis. Journal of Thermal Biology. 2013;38(8):570–575. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2013.10.001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heuton M, Ayala L, Burg C, Dayton K, McKenna K, Morante A, Puentedura G, Urbina N, Hillyard S, Steinberg S, van Breukelen F. Paradoxical anaerobism in desert pupfish. The Journal of experimental biology. 2015;218(Pt 23):3739–3745. doi: 10.1242/jeb.130633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Breukelen F, Martin SL. The Hibernation Continuum: Physiological and Molecular Aspects of Metabolic Plasticity in Mammals. Physiology (Bethesda, Md) 2015;30(4):273–281. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00010.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaiyala KJ. What does indirect calorimetry really tell us? Molecular metabolism. 2014;3(4):340–341. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blaxter K. Energy Metabolism in Animals and Man. Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tschop MH, Speakman JR, Arch JR, Auwerx J, Bruning JC, Chan L, Eckel RH, Farese RV, Jr, Galgani JE, Hambly C, Herman MA, Horvath TL, Kahn BB, Kozma SC, Maratos-Flier E, Muller TD, Munzberg H, Pfluger PT, Plum L, Reitman ML, Rahmouni K, Shulman GI, Thomas G, Kahn CR, Ravussin E. A guide to analysis of mouse energy metabolism. Nature methods. 2012;9(1):57–63. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi N, Li F, Hua K, Deng J, Wang CH, Bowers RR, Bartness TJ, Kim HS, Harp JB. Increased energy expenditure, dietary fat wasting, and resistance to diet-induced obesity in mice lacking renin. Cell metabolism. 2007;6(6):506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakai K, Agassandian K, Morimoto S, Sinnayah P, Cassell MD, Davisson RL, Sigmund CD. Local production of angiotensin II in the subfornical organ causes elevated drinking. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117(4):1088–1095. doi: 10.1172/jci31242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]