Abstract

The von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene plays a prominent role in the development of hemangioblastomas (HBs) within specific regions of the human’ central nervous system (CNS). Alterations in VHL gene are rarely observed in the more common features of human VHL-related tumors in animal models, and VHL heterozygous knockout (VHL+/−) mice do not develop HBs. We tested whether VHL heterozygous knockout mice exhibited genetic predisposition to the development of HBs and conferred a selective advantage involving growth of blood vessels to its carrier. No differences were observed between wild-type and VHL+/− mice in development ad reproduction. The heterozygous VHL+/− mice did not develop higher genetic susceptibility to CNS-HBs over their lifetime. Furthermore, this recessive VHL gene heterozygosity is relatively stable. Interestingly, we found these heterozygous VHL+/− mice gained an advantage conferring to angiogenic ability in a particular environment, compared with wild type mice. The heterozygous VHL+/− mice obviously enhanced hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF)-dependent and Twist1 angiogenic mechanism in response to acute cerebral ischemia, resulting in decreased cerebral tissue damage and neuroprotective response through neovascularization. Our findings provide evidence of partial loss function of VHL as a novel precise therapeutic target in acute cerebral ischemia.

Keywords: von Hippel-Lindau gene (VHL), Hemangioblastoma, Cerebral ischaemia, Neuroprotection, Gene therapy

Introduction

The VHL tumor suppressor gene was determined based on positional cloning in 1993 [1], and loss-of-function of the VHL gene was identified as the root cause of VHL disease, including hemangioblastomas (HBs) in the central nervous system (CNS). The two-hit hypothesis, based on statistical analysis of clinical data (correlation), serves as a unifying model for current understanding of how mutations in the VHL gene drive CNS-HBs [2]. However, there lacks a direct proof of this hypothesis due to the inability to recapitulate the more common features of human VHL disease [3–5]. Thus, an animal model for the development of CNS-HBs is needed to illustrate the underlying causal mechanism.

Indeed, mutation in the VHL gene is highly frequent in CNS-HBs, and can be found in nearly 100% of familiar HBs and in 4–25% of sporadic HBs (VHL somatic mutations). In those with VHL-defect (heterozygous flaw of the VHL gene), up to 60–80% of them will develop HBs in their lifetime [6–9]. However, most previous correlative genetic analysis considered only heterozygote (not homozygote) of the VHL gene. Furthermore, HB occurs by two accumulating mutation in a recessive single VHL gene, either an inherited mutation copy in one allele followed by a randomly acquired mutation in another allele (familiar HB), or two sequential randomly induced mutation---- one in each allele of the VHL gene (sporadic HB). The “first hit” (first mutation) has been investigated in great detail; however, little is known about the nature of the second hit [10]. In fact, this process, despite catering to the fact that sporadic HBs on average occur later than familial HBs, is speculative and remains unclear. It seems that the large discrepancy of the mutation rate in the two alleles within the same cell cannot be simply explained by random mutation. For example, the predicted mutation rate of two times (alleles) is 1:4.4*10−6 versus 1:0.6–0.8, respectively, in familial HBs (the ratio of two allele mutation rate is 1:2.64~3.52*106) [11–13], with a similar rate in sporadic HBs [14]. It is possible that a random mutation in one allele of the VHL gene could contribute to the next mutation in another allele. In this regard, it is important to take into account the heterozygosity of the VHL gene in the VHL-defect carriers [4]. Moreover, a homozygous VHL defect animal by acute genetic engineering in fact overlooks the predisposition process caused by the heterozygous VHL deficiency, implying that a background of the underlying molecular conditions has been changed, or that some latent functions of the initiative accumulations of VHL-related tumors have lost. For example, the VHL−/− mice could not be available, as a result of embryonic lethality owing to severe defective vascular phenotypes during embryonic phase [15–18]; and no development of HBs was observed in a homozygous VHL−/− zebrafish model [2]. Nevertheless, undoubtedly the model systems will continue to have a critical role in elucidating underlying mechanisms contributing to the development of these lesions, and the causal relationship between VHL genetic alterations and VHL-related tumor could be examined [4 16].

Our previous study demonstrated that human endothelial cells, by partly inactivation of the VHL gene’s silencing function, drive angiogenesis in vitro. Although VHL heterozygous mice do not develop spontaneous CNS-HBs in a relatively short period of time (<6 months) [3–5 17], the genetic susceptibility of these animals to carcinogen-induced CNS-HBs and preclinical changes, particularly the growth of blood vessels, have not been investigated. In this study, we examined the heterozygous process of the VHL gene in a mouse model, focusing on the subsequent genetic alterations of VHL gene in another allele (the predisposition process of the second hit) and the response to growth of blood vessels (VHL Alliance concerns).

Materials and methods

Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) Construction

A pair of TALENs targeting Exon 1 of VHL gene was created and were designed using the first version of TALEN Targeter [19 20]. The forward and reverse TALEN bind to 50 bp and 52 bp of DNA, respectively, and the two binding sites are separated by a 16-bp spacer region. TALENs were assembled using the TALE Toolkit (Addgene, catalog # 1000000019) according to published protocols [21]. The plasmid pEF1a-sp6 was used to construct the VHL targeting vector. TALEN plasmids were linearized with BamH I and Pst I and used as templates for in vitro transcription using a mMessage mMachine T7 Ultra Kit (Ambion), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mRNA products were purified using the MEGAclear kit (Ambion), and then precipitated, washed, and resuspended at 1 μg/μL in DEPC-treated H2o. TALEN mRNAs were subsequently diluted in 0.1× TE buffer at a final concentration of 10 ng/μL, dispensed into aliquots, and stored at −80 °C until being used for embryo injection.

Embryo manipulation

All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of our hospital, and were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Wild-type C57/BL6 mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 AM). Female embryo donors were superovulated with 25 IU of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (Sigma #G4877) between 11:00 AM and 12:00 noon, followed by 25 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (Sigma #CG5-1VL) 24 hours later, and were subsequently individually caged with a male stud rat. The following morning, donors were sacrificed and embryos collected from the oviducts. Embryos were cultured in M16 (Millipore) at 37 °C in 5% CO2/95% air. Fertilized one-cell embryos were transferred to M2 medium (Millipore) for microinjection. TALEN mRNAs were injected into the cytoplasm using glass injection pipettes. Embryos that survived the injection procedure were surgically transferred to the oviduct of day 0.5 postcoitum psuedopregnant recipient females that successfully mated vasectomized males.

Mutation analysis

Offspring from injected embryos were screened for mutations in the VHL locus using the Surveyor Mutation Detection Kit for Standard Gel Electrophoresis (Transgenomic Inc., Omaha, NE, USA). Briefly, DNA was prepared from mice tail (~0.5 cm) using QuickExtract DNA Extraction Solution (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI, USA). Tails were lysed in 150 μL QuickExtract Solution by heating to 68 °C for 20 min and 95 °C for 8 min. The VHL locus that overlaps the TALEN spacer region was amplified by PCR using wild-type VHL exon 1 primers. Amplification primers were forward: 5′-CGAGCCCTCTCAGGTCATCT-3′ and reverse 5′-CGGTGCCCGGTGGTAAGATC-3′. PCR reactions were performed using Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). The PCR condition was programmed as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 amplification cycles of 95 °C for 30 sec, 60 °C for 30 sec, and 72 °C for 90 sec, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products (20 μL) were sequenced using three primers on the VHL targeting vector:

305: 5′-CTCCCCTTCAGCTGGACAC-3′;

s248: 5′-CCACTACCTGCTCAGGCGTGAG-3′;

s211: 5′-GGACTTCTTCTCCTCCAGCTCG-3′.

Middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion (MCAO/R) model

Wild-type C57/BL6 and VHL heterozygous (+/−) mice were kept in standard housing conditions. MCAO model was established in mice as described previously, with minor modifications [22]. Briefly, after fasting for 12 h, anesthesia was performed in all animals using intraperitoneally injected sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg), followed by a ventral midline neck incision. The left external carotid and pterygopalatine arteries were isolated and ligated with 5-0 silk thread. The internal carotid artery (ICA) was occluded by a small clip at the peripheral site of the bifurcation of the ICA and the pterygopalatine artery. The common carotid artery (CCA) was ligated with 5-0 silk thread. A lysine-coated nylon monofilament (Beijing Sunbio Biotech Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) with a heat-blunted tip (diameter 0.32 ± 0.02 mm) was inserted into the external carotid artery (ECA). After removal of the clip at the ICA, the nylon monofilament was advanced to reach the origin of the middle cerebral artery until light resistance was felt. To confirm proper occlusion, a laser Doppler flowmetry (PeriFlux System 5000, Perimed Inc, Stockholm, Sweden) was fixed on the skull (1 mm posterior to the bregma and 6 mm from the midline on the right side) to monitor the regional cortical blood flow. An occlusion was confirmed when cerebral blood flow falls to less than 30% of baseline. After 1 h of MCAO, the nylon monofilament and common carotid artery ligature was removed to restore blood flow (reperfusion). After incision closure, the mice were placed into cages with free access to food and water. Sham-operated mice received identical surgery with the exception of filament insertion.

Behavioral testing

Modified neurological severity score (mNSS) was examined in wide type and VHL heterozygous (+/−) knockout mice (each n = 12) before and at 1, 3, 5, 7 days after MCAO in a blinded manner. mNSS is a comprehensive test for evaluating motor, sensory, reflex and balance abilities. Neurological deficits were graded on a scale of 0 to 18, and score points were awarded when mice were unable to perform the tests or lacked tested reflexes. Therefore, a higher score represents a more severe injury [23].

Limb placing score was initially used for assessing lateralized sensorimotor dysfunction of experimental stroke mice, and has also been translated to the mouse MCAO model recently [20]. Briefly, mice were brought laterally towards the benchtops, allowing for spontaneous placement of the forelimbs. Mice were then gently pulled down, forcing the limbs away from the bench top edge. Forelimb retrieval and placement were observed and graded as follows: 0 = immediate and complete placement; 1 = delayed or incomplete placement (> 2 seconds); and 2 = no placement.

Elevated body swing test was used to evaluate asymmetrical motor behavior [24]. Mice were held by tails, and the direction of the body swing, defined as an upper body turn of > 10 degrees to either side, was recorded for 30 trials each time. The numbers of left and right turns were counted, and final results were presented as the percentages of turns to the ischemia-impaired side (left side) out of 30 total trials.

Quantification of infarct volume

At 7 days after MCAO, mice were decapitated and their brains were rapidly removed and frozen, and cut into 2-mm-thick coronal sections. Infarct volume was measured according to the procedure described previously [25]. Slices were stained with 1.2% 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min at 37°C. After overnight immersion with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, slices were photographed. The unstained (white) areas indicated infracted tissue and the stained (red) areas indicated normal tissue. The infracted tissue areas were analyzed by digital image analysis software (SigmaScan Pro, Jandel, San Rafael, CA) and data were integrated from all slices.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

qRT-PCR was used to analyze the mRNA expression of VHL in wide type (+/+) and heterozygous (+/−) mice, and to analyze mRNA expressions of HIF-1α, erythropoietin (EPO), vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) and Twist1. Total RNA was extracted from the cerebral cortex of wide type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), or from ischemic boundary zone (IBZ) tissues of decapitated mice on the 7th days after MCAO using Trizol® reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After treatment with DNase (Life Technologies), total RNA (2 μg) was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the Superscript III enzyme (Life Technologies). The resulting cDNA was used as a template for qRT-PCR assay using specificβ-actin primer and SYBR Green reagent (TaKaRa, Japan) in the StepOne Plus Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The PCR condition was programmed as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 amplification cycles at 95°C for 5 sec and annealing at 60°C for 30 sec. Housekeeping gene β-actin served as an internal control and the expression of VHL, HIF-1α, EPO, VEGF and Twist1 mRNA was calculated by 2−ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences used in our study were as follows: VHL: forward: 5′-GGTTGGCAGCCAGTGGAGAG-3′,

reverse: 5′-GGTAAGATCGGGTAGGGCTG-3′;

HIF-1α: forward: 5′-GAAACGACCACTGCTAAGGCA-3′,

reverse: 5′-GGCAGACAGCTTAAGGCTCCT-3′;

EPO: forward: 5′-CATCTGCGACAGTCGAGTTCTG-3′,

reverse: 5′-CACAACCCATCGTGACATTTTC-3′;

VEGF: forward: 5′-TACCTCCACCATGCCAAGTG-3′,

reverse: 5′-TGGGACTTCTGCTCTCCTTCTG-3′;

Twist1: forward: 5′-AGAAGTCTGCGGGCTGTGGCG-3′,

reverse: 5′-GAGGGCAGCGTGGGGATGATC-3′;

β-actin: forward: 5′-CGTTGACATCCGTAAAGAC-3′;

reverse: 5′-TAGGAGCCAGGGCAGTA -3′.

All reactions were performed in triplicate. The relative mRNA expression of VHL of the three groups were all normalized to wild type mice, and relative HIF-1α, EPO, VEGF and Twist1 mRNA/protein expressions of the three groups were all normalized to the sham group.

Western blot analysis

Western blot was performed to examine the inhibitory effects of VHL heterozygous knockout on protein expressions of VHL, and HIF-1α, Twist1, as well as β-action following MCAO. The cortical and striatal tissues from IBZ were harvested at 7 days after MCAO (n = 8 for each group). RIPA lysis buffer was used to homogenize tissue and whole protein was extracted. Protein concentrations were detected using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein concentration assay kit (Beijing Biosea Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China). Denatured protein extracts (50 μg) were electrophoresed on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (SDS-PAGE) and then electrophoretically transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk and probed with primary antibodies rabbit anti-VHL antibody (1:300)( Sigma), HIF-1α (1:1000), antibody Twist 1 (1:1000), p-AKT (1:1000), p-GSK-3β (1:1000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and β-action (1:2000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at 4°C overnight. The membranes were washed three times with Tris-buffer saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) buffer, and were probed with secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit IgG) coupled with horseradish peroxidase (HPR) (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). β-actin served as a loading control. The protein bands were quantified using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), and the relative protein expressions were expressed as the ratios of HIF-1α and Twist 1 normalized to β-actin.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) assay

On day 7 after MCAO, the anesthetized mice were sacrificed by decapitation (n = 8 for each group). The brains were rapidly removed and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 48 h. Samples were incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies against Caspase-3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Beverly, MA, USA) at the concentrations of 1:100. As secondary antibody, immunoglobulin G conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Promega Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used at 37°C for 30 min. Before dehydration and mounting, slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. The marker-specific cells throughout the entire section (three sections per antibody staining) were counted and then the total counts in these sections were converted into cell densities for quantification.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Unpaired student t-test (two tailed) was applied to analyze the difference between two groups, and one-way ANOVA was applied to analyze the difference between more than two groups. All statistical analyses were performed using commercially available software (SPSS version 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Generation of VHL knockout mice

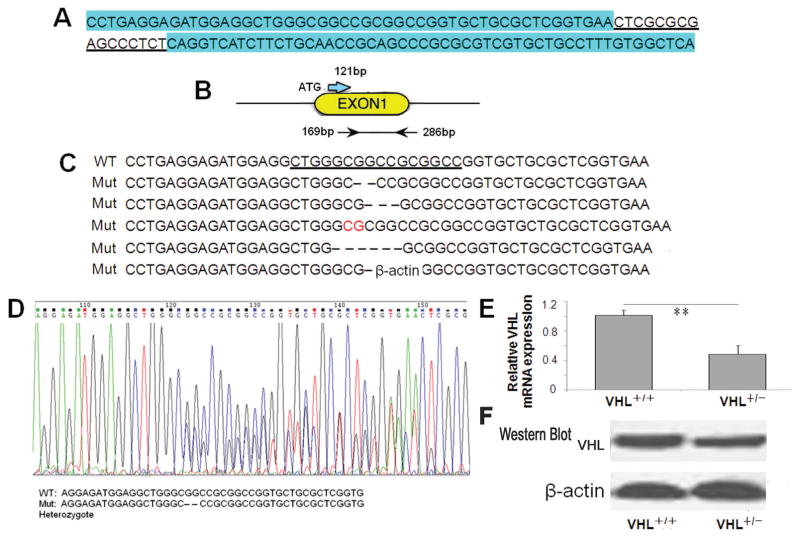

TALEN constructs were created that targeted the DNA sequence of the mouse VHL gene (Fig. 1A). The TALEN binding sites were located on VHL Exon 1 (Fig. 1B). TALEN mRNAs were transcribed in vitro and then injected into the cytoplasm of one-cell mouse embryos. Following transfer of injected embryos to pseudopregnant recipients, 18 live-born offspring were produced (F0). Offspring were screened for targeted disruption of VHL Exon 1 by PCR amplification and DNA sequence analysis. Of the 18 live-born mice produced at the first batch of mice, there were 5 founder mice that showed mutations in the VHL gene, including GG deletion, GCC deletion, CG insertion, GCGGCC deletion and GCC deletion (Fig. 1C).. At the second batch of mice (F1), 40 live-born mice were produced. There were 22 mice that inherited the above mutations in the VHL gene. But we failed to produce VHL homozygous mice. All heterozygous VHL mice appeared phenotypically as normal as wild type mice and lived beyond 36 months. 12 VHL heterozygous mice carrying the above mutations (F1) were selected for subsequent investigation, and the remaining heterozygous mice were observed until natural death. HB or similar tumor was not found and new mutations of VHL gene were not detected in CNS (cerebellar tissue).

Figure 1. Production of VHL heterozygous knockout mice by TALEN-mediated gene targeting.

(A) Double-stranded DNA sequence of the VHL locus that was targeted with TALENs. The TALEN binding sites are highlighted in blue and the spacer region is underlined. (B) Diagram of VHL Exon 1 (yellow oval) showing the start of translation (ATG) and the TALEN binding sites (arrows, starting at 169 bp and ending at 286 bp). (C) DNA sequence of the wild type (WT) VHL with TALEN binding sites. The underlined sequence indicates high sensitive region for mutation. Immediately beneath the wild type sequence is the sequence derived from cloned PCR products from founder (F0) mice (Mut), which demonstrates GG deletion, GCC deletion, CG insertion (highlight in red), GCGGCC deletion and GCC deletion. (D) DNA sequence chromatograms of F1 RT-PCR products demonstrating the GG deletion in the VHL+/− sample. (E, F) Relative VHL mRNA/protein level by qRT-PCR or Westernblot from cerebral cortex of wild type (+/+) and heterozygous (VHL+/−) mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared to the wild type mice.

The heterozygous VHL mice of this study appeared normal in development and reproduction, and could be used to establish cerebral ischemia model. Of the 12 VHL heterozygous mice (F1) for cerebral ischemia, DNA sequence analysis showed that the wild type sequence was identical to that in the mouse genome database (ACCESSION number: NC_000072). In contrast, sequences from the VHL heterozygous knockout samples revealed deletion (GG) and overlapping peaks in chromatograms (Fig. 1D). qRT-PCR and Westernblot were performed to analyze VHL expression in cerebellar cortex, which showed significantly lower VHL mRNA and protein expression in heterozygous (+/−) mice, compared to wild type (+/+) mice (P<0.01, Fig. 1E and F).

VHL deletion decreased the severity of cerebral ischemia in MCAO mice

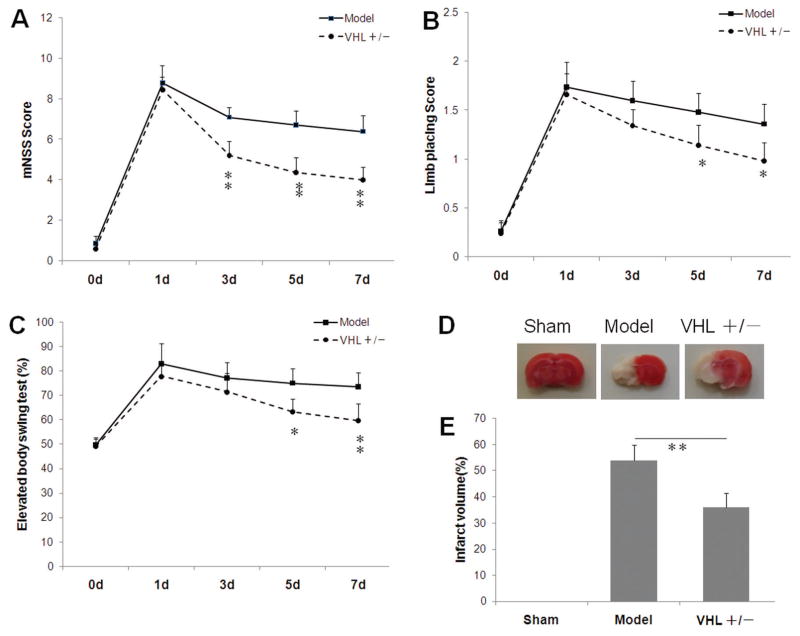

To evaluate whether VHL heterozygous knockout affects functional recovery from MCAO, mNSS, limb placing score and elevated body swing test were used to estimate neurological deficit at different time points following MCAO. mNSS score was significantly decreased in the VHL heterozygous (+/−) knockout mice, compared with the wild type mice 3 days, 5 days and 7 days after MCAO (P<0.01, Fig. 2A). Limb placing score was significantly decreased in the VHL heterozygous (+/−) knockout mice, compared with wild type mice 5 days and 7 days after MCAO (P<0.05, Fig. 2B). Elevated body swing test score was significantly decreased in the VHL heterozygous (+/−) knockout mice, compared with wild type mice 5 days and 7 days after MCAO (P<0.05, Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. VHL deletion shows decreased severity of cerebral ischemia in mice.

Compared to the wild type mice, VHL heterozygous (+/−) knockout mice showed significantly lower modified neurological severity scores (mNSS) (A), lower limb placing score (B) and lower elevated body swing test (C) following MCAO (n = 12 per group). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared to the wide type mice. (D) At day 7 after MCAO, brain slices were stained with 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC), and representative photographs were shown. The healthy tissue was stained with red and the infracted tissue was unstained and showed white. (E) Compared to the wild type mice, VHL heterozygous (+/−) knockout mice show significantly reduced infarct volume at 7 days after MCAO. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. d: days. MCAO: Middle cerebral artery occlusion.

To investigate whether VHL heterozygous knockout affects acute infarct damage from MCAO, we compared infarct volume between wide type and VHL heterozygous knockout mice. At day 7 after MCAO, a series of sections showed extensive infarction by TTC staining in the cerebral cortical and subcortical areas (Fig. 2D). In MCAO model, infarct volume accounted for more than half of the whole hemisphere. VHL heterozygous mice had significantly smaller infarct volume than wide type mice (P<0.01, Fig. 2E).

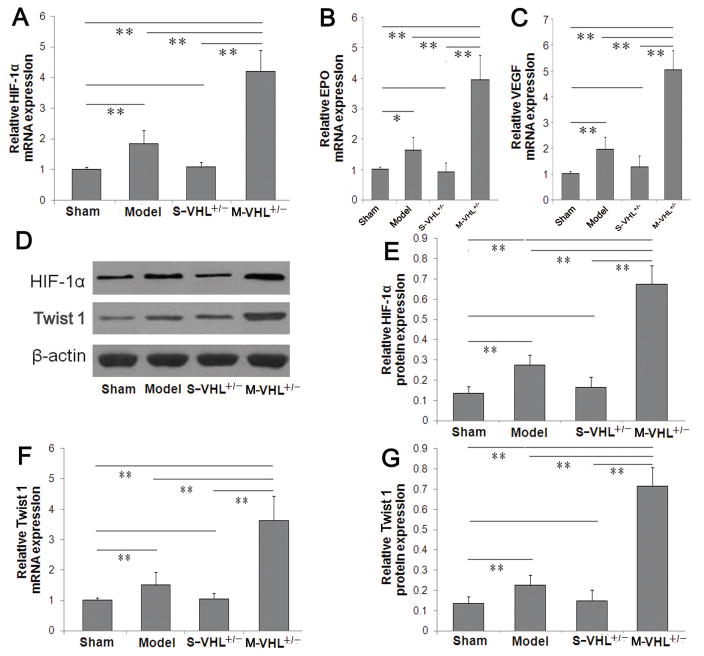

VHL deletion increased the expression of HIF-1α and its downstream genes, and Twist 1 in the ischemic brain

To test whether VHL deletion could affect the cerebral HIF-1α gene expression, qRT-PCR assay and western blot analysis were performed to measure HIF-1α mRNA and protein expressions in ischemic boundary zone. We found that the MCAO model group had significantly increased HIF-1α mRNA and protein levels, compared with the sham group (P<0.01, Fig. 3A, 3D, 3E). Moreover, VHL deletion significantly increased HIF-1α mRNA and protein levels in the ischemic boundary zone 7 days after MCAO (P<0.01). We further measured mRNA expressions of EPO and VEGF, two downstream genes of HIF-1α. Compared to wild type mice, VHL heterozygous mice showed significantly increased EPO and VEGF mRNA levels 7 days after MCAO (P<0.01, Fig. 3B, 3C). Meanwhile, we also detected Twist 1 expression, a HIF-independent angiogenic gene. qRT-PCR assay and western blot analysis showed that the expressions of Twist 1 mRNA and protein in ischemic boundary zone increased significantly in VHL heterozygous mice group, compared with the wild mice group after MCAO (P<0.01, Fig. 3D, 3F, 3G).

Figure 3. VHL heterozygous deletion increases the expression of HIF-1α and its downstream genes, and Twist 1 gene at 7 days after MCAO.

(A) Compared to the wild type mice with MCAO, VHL heterozygous (+/−) knockout mice showed unregulated HIF-1α mRNA level, and upregulated expression in its downstream genes EPO (B) and VEGF (C) by qRT-PCR. (D) Representative images of western blot in HIF-1α and Twist 1 protein. (E) Quantitative data of western blot demonstrated increased HIF-1α protein (n = 8 per group). Quantitative analysis also showed increased Twist 1 mRNA level (F) and level (G) in heterozygous (+/−) knockout mice, compared with the wild type mice after MCAO. Data were expressed as mean values ± standard deviation (SD). *P<0.05, **P<0.01. MCAO: Middle cerebral artery occlusion. There are no difference between the sham-WT group and the sham-VHL+/− group.

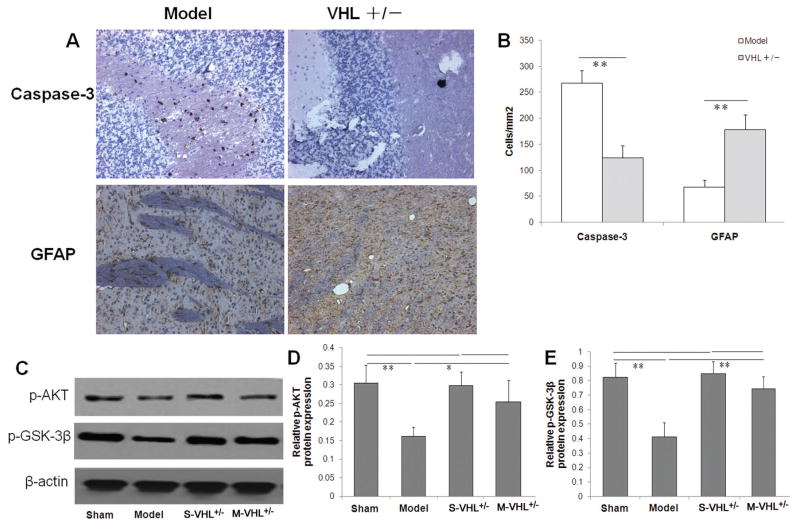

VHL deletion showed neuroprotective effects in MCAO mice

In order to explore the neuroprotective effects of VHL deletion, immunohistochemical assay was performed to measure the protein expressions of Caspase-3 and GFAP. Compared with wild type mice, VHL heterozygous mice showed less Caspase-3+ cells and more GFAP+ cells in ischemic boundary zone at 7 days after MCAO (Fig. 4A). Quantitative analysis revealed that VHL heterozygous mice exhibited a significantly lower number of Caspase-3+ and a higher number of GFAP+ cells (Caspase-3+: 123.6±23.9 cells/mm2; GFAP+: 178.2±28.7 cells/mm2) than wild type mice (Caspase-3+: 267.6±24.4 cells/mm2; GFAP+: 67.6±13.1 cells/mm2) (P<0.01, Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. VHL heterozygous deletion showed neuroprotective effects in mice with cerebral ischemia.

(A) Immunohistochemical staining for Caspase-3 and GFAP in IBZ on 7 days following MCAO. (B) Quantitative data of Caspase-3 and GFAP levels by immunohistochemical staining. Compared to the wild type mice with MCAO, VHL heterozygous (+/−) knockout mice showed significantly lower Caspase-3 and higher GFAP levels. (C) Quantitative data of p-AKT and p-GSK-3β proteins by western blot (n = 8 per group). Compared to the wild type mice with MCAO, VHL heterozygous (+/−) knockout mice show significantly increased p-AKT (D) and p-GSK-3β proteins (E) 7 days following MCAO. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. MCAO: Middle cerebral artery occlusion. There are no difference between the sham-WT group and the sham-VHL+/− group.

We further performed western blot analysis to explore whether VHL deletion could regulate portion expression of p-AKT and p-GSK-3β, two survival molecules associated with HIF-1α. We found that the protein expressions of p-AKT and p-GSK-3β in the ischemic boundary zone were significantly lower 7 days after MCAO, compared with the sham group. However, VHL heterozygous mice showed significantly higher p-AKT (P<0.05) and p-GSK-3β (P<0.01) levels compared to wild type mice (Fig. 4C, 4D, 4E). Collectively, these results indicated that VHL deletion can demonstrate neuroprotective effects by inhibition of HIF-1α and elevation of p-AKT and p-GSK-3β in the ischemic boundary zone.

Discussion

In this study, we generated VHL heterozygous knockout mice by TALENs, and demonstrated that VHL heterozygous mice did not show predisposition to the development of HBs and that a loss of one allele of the VHL gene did not induce new mutation of another alleles in CNS over the lifetime. Interestingly, we found that these VHL+/− mice exhibited smaller infarct volume by enhanced angiogenic ability, and showed significantly improved neurological function in response to acute cerebral ischemia. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing that the functional status via VHL heterozygous gene knockout is related to the growth of blood vessels in vivo under normal conditions and in severe brain ischemia. We also found that partly inactivation of the VHL function will offer a novel attacking approach for the therapy of acute cerebral ischemia.

The underlying mechanism linking VHL inactivation with the pathogenesis of CNS-HBs remains to be uncovered. In the present study, the offspring of VHL knockout mice carried VHL heterozygous or wild type, with inheritance of all produced specific mutations of the VHL gene to the next generation. However, homozygous VHL −/− mice were not available in this study, consistent with previous reports that homozygous VHL −/− mice possibly died in utero due to defective placental vasculogenesis [15 26]. All heterozygous VHL +/− mice appeared phenotypically normal without the susceptibility to the development of HBs [17]. Moreover, we did not detect new mutations of another allele of the VHL gene in their cerebellar tissues. In addition to the different species and the inadequate time-dependent penetrance (limitation to the mouse lifespan), this result indicates that VHL homozygous gene under normal conditions was stable, and does not contribute to the mutation in another allele of the VHL gene. This is consistent with the observation that some individuals of familiar VHL-defect carriers showed no occurrence of HBs in their lifetime. Since the first mutation rate of VHL gene is much higher than that of human gene (the average random rate is 1~2*10−8 per nucleotide per generation [27]), this stability of the recessive VHL gene heterozygosity indicates a possibility that a mutation becomes frequent under appropriate conditions if it confers a selective advantage to its carrier, and the selective mechanism that individuals gains an advantage conferring to survive in a particular environment [28–30]. Our results also suggested a much bigger difference of between the two mutation rates in each allele of VHL gene within HBs, which could not be explained by random mutation, need to explore the underlying mechanism either other genetic affection or/and environmental insult [31–33].

All inherited VHL-defect carriers are in a sub-clinical status that requires effective management [34 35]. These individuals with VHL heterozygous gene are also of particular concern of the VHL Alliance, especially in the growth of blood vessels. In this study, we detected response to acute cerebral ischemia. We found that heterozygous VHL mice demonstrated improved neurological function and smaller infarct volume, compared with wild type mice, implying a potential novel precise therapeutic target in cerebral ischemia. We further found that heterozygous VHL deletion could increase mRNA and protein expressions of HIF-1α in ischemic boundary zone of MCAO mice, indicating that this inhibitory effect of HIF-1α by VHL [36] exists in our heterozygous MCAO model despite their normal phenotype. The effects of this enhanced HIF-1α expression on ischemic brain are complex [37]. On the one hand, HIF-1α demonstrates neuroprotective effect on ischemic brain by upregulating the transcription of EPO and VEGF. EPO induces several pathways associated with neuroprotection, and VEGF can promote neovascularization in hypoxic-ischemic brain areas [38]. On the other hand, HIF-1α also demonstrates neurotoxic effect by increasing permeability of blood-brain barrier (BBB) and aggravation of brain edema and neuronal death [39]. Our study showed significantly higher mRNA levels of EPO and VEGF in ischemic brain tissues of heterozygous MCAO mice, and indicated the existence of enhanced HIF-1α activity in heterozygous mice. The enhanced expression of VEGF suggested that neovascularization may be associated with reduced hypoxic-ischemic damage in heterozygous VHL mice [18]. Furthermore, we also found that Twist 1 expression, a novel HIF/VEGF-independent angiogenic signaling driven by partial loss function of VHL, increased in ischemic boundary zone of MCAO mice, compared with wild type mice. This result indicated that HIF-independent angiogenesis mediated by Twist 1 signaling increased neovascularization in the ischemic area after partial inactivation of VHL. In addition, in heterozygous VHL +/− mice moderately increased levels of VEGF did not cause hemorrhages and appeared phenotypically normal. Taken together, the VHL+/− mice obviously had enhanced HIF-dependent and Twist1 angiogenesis in response to acute cerebral ischemia, which resulted in decreased cerebral tissue damage through neovascularization.

Subsequently, we further detected enhanced expression of p-AKT and p-GSK-3β in heterozygous VHL mice after MCAO. p-AKT and p-GSK-3β protein expressions could be upregulated by EPO [40 41], and could provide neuroprotection [42], both of them also are associated with reduced apoptosis in cortical neurons [43]. This was supported by our study that the number of Caspase-3+ neural cells was decreased in the ischemic boundary zone of heterozygous VHL mice after MCAO. Moreover, the survival effect of VHL deletion was also confirmed in mice with spinal cord injury, in which VHL was co-localized with caspase-3 in neurons, and neuronal apoptosis was significantly reduced by VHL depletion through short interfering RNA [44]. We also found increased GFAP+ neural cells in heterozygous VHL mice. The enhanced GFAP+ cells were found to activate astrocytes, reduce neuronal death following brain ischemia [45], and were associated with neuroprotective agent 2-oxoglutarate and Ilexonin A [46 47], indicating that neuronal regeneration might be enhanced in heterozygous VHL mice.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that mice with a loss of one allele of the VHL gene exhibited normal phenotypes without evidence of predisposition to the development of CNS-HBs. Heterozygous VHL +/− mice exhibited the neuroprotective response to acute cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury due to enhanced angiogenesis by HIF-dependent regulation and HIF-independent Twist 1 signaling. Increased expressions of p-AKT and p-GSK-3β indicated reduced neuronal apoptosis, as evidenced by elevated Caspase-3+ and GFAP+ cells in the ischemic boundary zone. Our findings provide evidence of loss function of VHL as a precise therapeutic target in acute cerebral ischemia. Further investigations are needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of heterozygous VHL knockout in the neuroprotection of cerebral ischemia based on the risk-to-benefit ratio.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (15411951800, 15410723200). Dr. Jingyun Yang’s research was supported by NIH/NIA R01AG036042 and the Illinois Department of Public Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No conflicting relationship exists for any author.

References

- 1.Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J, et al. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science. 1993;260(5112):1317–20. doi: 10.1126/science.8493574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Rooijen E, Voest EE, Logister I, et al. von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor mutants faithfully model pathological hypoxia-driven angiogenesis and vascular retinopathies in zebrafish. Disease models & mechanisms. 2010;3(5–6):343–53. doi: 10.1242/dmm.004036. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park S, Chan CC. Von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL): a need for a murine model with retinal hemangioblastoma. Histology and histopathology. 2012;27(8):975–84. doi: 10.14670/hh-27.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu T. Complex cellular functions of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene: insights from model organisms. Oncogene. 2012;31(18):2247–57. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.442. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haase VH. The VHL tumor suppressor in development and disease: functional studies in mice by conditional gene targeting. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2005;16(4–5):564–74. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.03.006. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maher ER, Yates JR, Harries R, et al. Clinical features and natural history of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Q J Med. 1990;77(283):1151–63. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/77.2.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richard S, David P, Marsot-Dupuch K, et al. Central nervous system hemangioblastomas, endolymphatic sac tumors, and von Hippel-Lindau disease. Neurosurg Rev. 2000;23(1):1–22. doi: 10.1007/s101430050024. discussion 23–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wanebo JE, Lonser RR, Glenn GM, et al. The natural history of hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(1):82–94. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.1.0082. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shehata BM, Stockwell CA, Castellano-Sanchez AA, et al. Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease: an update on the clinico-pathologic and genetic aspects. Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15(3):165–71. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31816f852e. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glasker S, Sohn TS, Okamoto H, et al. Second hit deletion size in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Annals of neurology. 2006;59(1):105–10. doi: 10.1002/ana.20704. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards FM, Payne SJ, Zbar B, et al. Molecular analysis of de novo germline mutations in the von Hippel-Lindau disease gene. Human molecular genetics. 1995;4(11):2139–43. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshida M, Ashida S, Kondo K, et al. Germ-line mutation analysis in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease in Japan: an extended study of 77 families. Japanese journal of cancer research: Gann. 2000;91(2):204–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb00933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sgambati MT, Stolle C, Choyke PL, et al. Mosaicism in von Hippel-Lindau disease: lessons from kindreds with germline mutations identified in offspring with mosaic parents. American journal of human genetics. 2000;66(1):84–91. doi: 10.1086/302726. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JY, Dong SM, Park WS, et al. Loss of heterozygosity and somatic mutations of the VHL tumor suppressor gene in sporadic cerebellar hemangioblastomas. Cancer research. 1998;58(3):504–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gnarra JR, Ward JM, Porter FD, et al. Defective placental vasculogenesis causes embryonic lethality in VHL-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(17):9102–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haase VH, Glickman JN, Socolovsky M, et al. Vascular tumors in livers with targeted inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(4):1583–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1583. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleymenova E, Everitt JI, Pluta L, et al. Susceptibility to vascular neoplasms but no increased susceptibility to renal carcinogenesis in Vhl knockout mice. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(3):309–15. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh017. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Wang Y, Gao Z, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation from adipose protein 2-cre mediated knockout of von Hippel-Lindau gene leads to embryonic lethality. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology. 2012;39(2):145–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05656.x. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cermak T, Doyle EL, Christian M, et al. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39(12):e82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr218. published Online First: Epub Date. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin K, Wang X, Xie L, et al. Transgenic ablation of doublecortin-expressing cells suppresses adult neurogenesis and worsens stroke outcome in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(17):7993–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000154107. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanjana NE, Cong L, Zhou Y, et al. A transcription activator-like effector toolbox for genome engineering. Nature protocols. 2012;7(1):171–92. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.431. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishikawa M, Cooper D, Arumugam TV, et al. Platelet-leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions after middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2004;24(8):907–15. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000132690.96836.7F. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Chopp M, Zhang RL, et al. Erythropoietin amplifies stroke-induced oligodendrogenesis in the rat. PloS one. 2010;5(6):e11016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011016. published Online First: Epub Date. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Q, van Hoecke M, Tang XN, et al. Pyruvate protects against experimental stroke via an anti-inflammatory mechanism. Neurobiology of disease. 2009;36(1):223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.018. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitano H, Young JM, Cheng J, et al. Gender-specific response to isoflurane preconditioning in focal cerebral ischemia. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2007;27(7):1377–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600444. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pascal LE, Ai J, Rigatti LH, et al. EAF2 loss enhances angiogenic effects of Von Hippel-Lindau heterozygosity on the murine liver and prostate. Angiogenesis. 2011;14(3):331–43. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9217-1. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crow JF. Spontaneous mutation as a risk factor. Experimental and clinical immunogenetics. 1995;12(3):121–8. doi: 10.1159/000424865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zlotogora J. Selection for carriers of recessive diseases: a common phenomenon? American journal of medical genetics. 1998;80(3):266–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19981116)80:3<266::aid-ajmg17>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zlotogora J. High frequencies of human genetic diseases: founder effect with genetic drift or selection? American journal of medical genetics. 1994;49(1):10–3. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320490104. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zlotogora J. Multiple mutations responsible for frequent genetic diseases in isolated populations. European journal of human genetics: EJHG. 2007;15(3):272–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201760. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nordstrom-O’Brien M, van der Luijt RB, van Rooijen E, et al. Genetic analysis of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(5):521–37. doi: 10.1002/humu.21219. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma D, Zhang M, Chen L, et al. Hemangioblastomas might derive from neoplastic transformation of neural stem cells/progenitors in the specific niche. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(1):102–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq214. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sims KB. Von Hippel-Lindau disease: gene to bedside. Curr Opin Neurol. 2001;14(6):695–703. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pochon S, Graber P, Yeager M, et al. Demonstration of a second ligand for the low affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E (CD23) using recombinant CD23 reconstituted into fluorescent liposomes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1992;176(2):389–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beitner MM, Winship I, Drummond KJ. Neurosurgical considerations in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18(2):171–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.04.054. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krieg M, Haas R, Brauch H, et al. Up-regulation of hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha under normoxic conditions in renal carcinoma cells by von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene loss of function. Oncogene. 2000;19(48):5435–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203938. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergeron M, Yu AY, Solway KE, et al. Induction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) and its target genes following focal ischaemia in rat brain. The European journal of neuroscience. 1999;11(12):4159–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan X, Heijnen CJ, van der Kooij MA, et al. The role and regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha expression in brain development and neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Brain research reviews. 2009;62(1):99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.09.006. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen W, Jadhav V, Tang J, et al. HIF-1alpha inhibition ameliorates neonatal brain injury in a rat pup hypoxic-ischemic model. Neurobiology of disease. 2008;31(3):433–41. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.05.020. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40.Jia Y, Mo SJ, Feng QQ, et al. EPO-dependent activation of PI3K/Akt/FoxO3a signalling mediates neuroprotection in in vitro and in vivo models of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of molecular neuroscience: MN. 2014;53(1):117–24. doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-0208-0. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishihara M, Miura T, Miki T, et al. Erythropoietin affords additional cardioprotection to preconditioned hearts by enhanced phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2006;291(2):H748–55. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00837.2005. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qi ZF, Luo YM, Liu XR, et al. AKT/GSK3beta-dependent autophagy contributes to the neuroprotection of limb remote ischemic postconditioning in the transient cerebral ischemic rat model. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics. 2012;18(12):965–73. doi: 10.1111/cns.12016. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shang Y, Wu Y, Yao S, et al. Protective effect of erythropoietin against ketamine-induced apoptosis in cultured rat cortical neurons: involvement of PI3K/Akt and GSK-3 beta pathway. Apoptosis: an international journal on programmed cell death. 2007;12(12):2187–95. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0141-1. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hao J, Chen X, Fu T, et al. The Expression of VHL (Von Hippel-Lindau) After Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury and Its Role in Neuronal Apoptosis. Neurochemical research. 2016;41(9):2391–400. doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-1952-7. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshikawa A, Kamide T, Hashida K, et al. Deletion of Atf6alpha impairs astroglial activation and enhances neuronal death following brain ischemia in mice. Journal of neurochemistry. 2015;132(3):342–53. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12981. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kovalenko TN, Ushakova GA, Osadchenko I, et al. The neuroprotective effect of 2-oxoglutarate in the experimental ischemia of hippocampus. Journal of physiology and pharmacology: an official journal of the Polish Physiological Society. 2011;62(2):239–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu AL, Zheng GY, Wang ZJ, et al. Neuroprotective effects of Ilexonin A following transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Molecular medicine reports. 2016;13(4):2957–66. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.4921. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]