Combustible and smokeless tobacco use causes adverse health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease and multiple types of cancer (1,2). Standard approaches for measuring tobacco use include self-reported surveys of use and consumption estimates based on tobacco excise tax data (3,4). To provide the most recently available tobacco consumption estimates in the United States, CDC used federal excise tax data to estimate total and per capita consumption during 2000–2015 for combustible tobacco (cigarettes, roll-your-own tobacco, pipe tobacco, small cigars, and large cigars) and smokeless tobacco (chewing tobacco and dry snuff). During this period, total combustible tobacco consumption decreased 33.5%, or 43.7% per capita. Although total cigarette consumption decreased 38.7%, cigarettes remained the most commonly used combustible tobacco product. Total noncigarette combustible tobacco (i.e., cigars, roll-your-own, and pipe tobacco) consumption increased 117.1%, or 83.8% per capita during 2000–2015. Total consumption of smokeless tobacco increased 23.1%, or 4.2% per capita. Notably, total cigarette consumption was 267.0 billion cigarettes in 2015 compared with 262.7 billion in 2014. These findings indicate that although cigarette smoking declined overall during 2000–2015, and each year from 2000 to 2014, the number of cigarettes consumed in 2015 was higher than in 2014, and the first time annual cigarette consumption was higher than the previous year since 1973. Moreover, the consumption of other combustible and smokeless tobacco products remains substantial. Implementation of proven tobacco prevention interventions (5) is warranted to further reduce tobacco use in the United States.

Publicly available federal excise tax data from the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau were analyzed for 2000–2015; these data included information on products taxed domestically and imported into the United States (6). Using monthly tax data, per unit (e.g., per cigarette or per cigar) consumption for each combustible product was assessed. To enable comparisons between cigarettes, cigars (small and large), and loose tobacco (roll-your-own and pipe tobacco), data were converted from pounds of tobacco to a per cigarette equivalent using established methods (4).* Smokeless tobacco (i.e., chew and dry snuff) data were reported in pounds. Adult per capita tobacco consumption was estimated by dividing total consumption by the number of U.S. persons aged ≥18 years using Census Bureau data.† Relative percent change was calculated across years. Joinpoint regression was performed to determine statistically significant trends during 2000–2015.

During 2000–2015, total consumption of all combustible tobacco products decreased 33.5% from 450.7 to 299.9 billion cigarette equivalents (p<0.05), a per capita decrease of 43.7% from 2,148 to 1,211 cigarette equivalents (p<0.05) (Table). The proportion of total combustible tobacco consumption composed of loose tobacco and cigars increased from 3.4% to 11.0% (p<0.05).

TABLE.

Total and per capita* consumption of cigarettes, all combustible tobacco, noncigarette combustible tobacco, and smokeless tobacco products — United States, 2000–2015

| Year | Cigarettes

|

All combustible tobacco (cigarettes, cigars, and loose tobacco [cigarette equivalents])

|

Noncigarette combustible tobacco (cigars and loose tobacco [cigarette equivalents])

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (millions) | % change | Per capita | % change | Total (millions) | % change | Per capita | % change | Total (millions) | % change | Per capita | % change | |

| 2000 | 435,570 | — | 2,076 | — | 450,725 | — | 2,148 | — | 15,155 | — | 72 | — |

| 2001 | 426,720 | −2.0 | 2,010 | −3.2 | 440,693 | −2.2 | 2,075 | −3.4 | 13,973 | −7.8 | 66 | −8.9 |

| 2002 | 415,724 | −2.6 | 1,936 | −3.7 | 430,763 | −2.3 | 2,006 | −3.4 | 15,040 | 7.6 | 70 | 6.4 |

| 2003 | 400,327 | −3.7 | 1,844 | −4.7 | 415,930 | −3.4 | 1,916 | −4.5 | 15,603 | 3.8 | 72 | 2.6 |

| 2004 | 397,655 | −0.7 | 1,811 | −1.8 | 414,421 | −0.4 | 1,888 | −1.5 | 16,766 | 7.5 | 76 | 6.2 |

| 2005 | 381,098 | −4.2 | 1,717 | −5.2 | 401,187 | −3.2 | 1,807 | −4.3 | 20,089 | 19.8 | 90 | 18.5 |

| 2006 | 380,594 | −0.1 | 1,695 | −1.3 | 401,241 | 0.01 | 1,787 | −1.1 | 20,648 | 2.8 | 92 | 1.6 |

| 2007 | 361,590 | −5.0 | 1,591 | −6.1 | 384,087 | −4.3 | 1,690 | −5.4 | 22,497 | 9.0 | 99 | 7.7 |

| 2008 | 346,419 | −4.2 | 1,507 | −5.3 | 371,264 | −3.3 | 1,615 | −4.5 | 24,845 | 10.4 | 108 | 9.1 |

| 2009 | 317,736 | −8.3 | 1,367 | −9.3 | 342,124 | −7.9 | 1,472 | −8.9 | 24,388 | −1.8 | 105 | −2.9 |

| 2010 | 300,451 | −5.4 | 1,278 | −6.5 | 329,239 | −3.8 | 1,400 | −4.9 | 28,788 | 18.0 | 122 | 16.7 |

| 2011 | 292,769 | −2.6 | 1,232 | −3.6 | 326,577 | −0.8 | 1,374 | −1.9 | 33,808 | 17.4 | 142 | 16.2 |

| 2012 | 287,187 | −1.9 | 1,196 | −2.9 | 322,396 | −1.3 | 1,342 | −2.3 | 35,209 | 4.1 | 147 | 3.0 |

| 2013 | 273,785 | −4.7 | 1,129 | −5.6 | 309,641 | −4 | 1,277 | −4.9 | 35,856 | 1.8 | 148 | 0.8 |

| 2014 | 262,681 | −4.1 | 1,071 | −5.1 | 298,196 | −3.7 | 1,216 | −4.8 | 35,515 | −1.0 | 145 | −2.1 |

| 2015 | 267,043 | 1.7 | 1,078 | 0.6 | 299,938 | 0.6 | 1,211 | −0.4 | 32,894 | −7.4 | 133 | −8.3 |

| % change, 2000–2015 | — | −38.7† | — | −48.1† | — | −33.5† | — | −43.7† | — | 117.1† | — | 83.8† |

| Year | Total cigars (small cigars and large cigars [cigarette equivalents]) | Small cigars (cigarette equivalents) | Large cigars (cigarette equivalents) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total (millions) | % change | Per capita | % change | Total (millions) | % change | Per capita | % change | Total (millions) | % change | Per capita | % change | |

| 2000 | 6,161 | — | 29 | — | 2,279 | — | 11 | — | 3,882 | — | 19 | — |

| 2001 | 6,344 | 3.0 | 30 | 1.7 | 2,239 | −1.8 | 11 | −2.9 | 4,105 | 5.7 | 19 | 4.5 |

| 2002 | 6,546 | 3.2 | 31 | 3.8 | 2,343 | 4.6 | 11 | 3.5 | 4,203 | 2.4 | 20 | 1.3 |

| 2003 | 7,007 | 7.0 | 32 | 4.1 | 2,474 | 5.6 | 11 | 4.50 | 4,533 | 7.9 | 21 | 6.7 |

| 2004 | 7,852 | 12.1 | 36 | 10.8 | 2,917 | 17.9 | 13 | 16.6 | 4,935 | 8.9 | 22 | 7.6 |

| 2005 | 9,052 | 15.3 | 41 | 14.0 | 3,968 | 36.0 | 18 | 34.5 | 5,084 | 3.0 | 23 | 1.9 |

| 2006 | 9,733 | 7.5 | 43 | 6.3 | 4,434 | 11.7 | 20 | 10.4 | 5,299 | 4.2 | 24 | 3.0 |

| 2007 | 10,708 | 10.0 | 47 | 8.7 | 5,161 | 16.4 | 23 | 15.0 | 5,548 | 4.7 | 24 | 3.5 |

| 2008 | 11,538 | 7.7 | 50 | 6.5 | 5,881 | 14.0 | 26 | 12.6 | 5,657 | 2.0 | 25 | 0.8 |

| 2009 | 12,127 | 5.1 | 52 | 4.0 | 2,343 | −60.2 | 10 | −60.6 | 9,784 | 73.0 | 42 | 71.1 |

| 2010 | 13,269 | 9.4 | 56 | 8.2 | 983 | −58.1 | 4 | −58.5 | 12,287 | 25.6 | 52 | 24.1 |

| 2011 | 13,727 | 3.5 | 58 | 2.4 | 798 | −18.8 | 3 | −19.6 | 12,929 | 5.2 | 54 | 4.1 |

| 2012 | 13,787 | 0.4 | 57 | −0.6 | 762 | −4.5 | 3 | −5.5 | 13,025 | 0.7 | 54 | −0.3 |

| 2013 | 13,159 | −4.6 | 54 | −5.5 | 659 | −13.5 | 3 | −14.3 | 12,499 | −4.0 | 52 | −5.0 |

| 2014 | 13,695 | 4.1 | 56 | 2.9 | 564 | −14.4 | 2 | −15.4 | 13,131 | 5.1 | 54 | 3.9 |

| 2015 | 11,411 | −16.7 | 46 | −17.5 | 556 | −1.3 | 2 | −2.3 | 10,855 | −17.3 | 44 | −18.2 |

| % change, 2000–2015 | — | 85.2† | — | 56.8† | — | −75.6† | — | −79.3† | — | 179.6† | — | 136.8† |

| Year | Total loose tobacco (roll-your-own, and pipe [cigarette equivalents])

|

Roll-your-own loose tobacco (cigarette equivalents)

|

Pipe tobacco (cigarette equivalents)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (millions) | % change | Per capita | % change | Total (millions) | % change | Per capita | % change | Total (millions) | % change | Per capita | % change | |

| 2000 | 8,994 | — | 43 | — | 5,995 | — | 29 | 2,999 | — | 14 | — | |

| 2001 | 7,629 | −15.2 | 36 | −16.2 | 4,714 | −21.4 | 22 | −22.3 | 2,915 | −2.8 | 14 | −4.0 |

| 2002 | 8,494 | 11.3 | 40 | 10.1 | 5,737 | 21.7 | 27 | 20.3 | 2,757 | −5.4 | 13 | −6.5 |

| 2003 | 8,596 | 1.2 | 40 | 0.1 | 6,207 | 8.2 | 29 | 7.0 | 2,389 | −13.3 | 11 | −14.3 |

| 2004 | 8,914 | 3.7 | 41 | 2.5 | 6,600 | 6.40 | 30 | 5.1 | 2,314 | −3.2 | 11 | −4.3 |

| 2005 | 11,037 | 23.8 | 50 | 22.4 | 8,614 | 30.5 | 39 | 29.1 | 2,423 | 4.7 | 11 | 3.6 |

| 2006 | 10,915 | −1.1 | 49 | −2.2 | 8,594 | −0.2 | 38 | −1.4 | 2,322 | −4.2 | 10 | −5.3 |

| 2007 | 11,788 | 8.0 | 52 | 6.7 | 9,326 | 8.5 | 41 | 7.3 | 2,463 | 6.1 | 11 | 4.8 |

| 2008 | 13,307 | 12.9 | 58 | 11.6 | 10,721 | 15.0 | 47 | 13.6 | 2,586 | 5.0 | 11 | 3.8 |

| 2009 | 12,261 | −7.9 | 53 | −8.9 | 6,006 | −44.0 | 26 | −44.6 | 6,256 | 142.0 | 27 | 139.3 |

| 2010 | 15,519 | 26.6 | 66 | 25.1 | 3,168 | −47.3 | 13 | −47.9 | 12,351 | 97.4 | 53 | 95.2 |

| 2011 | 20,081 | 29.4 | 85 | 28.8 | 2,622 | −17.2 | 11 | −18.1 | 17,459 | 41.4 | 73 | 39.9 |

| 2012 | 21,422 | 6.7 | 89 | 4.9 | 2,240 | −14.6 | 9 | −15.5 | 19,183 | 9.9 | 80 | 8.7 |

| 2013 | 22,697 | 5.9 | 94 | 4.9 | 1,898 | −15.3 | 8 | −16.1 | 20,799 | 8.4 | 86 | 7.4 |

| 2014 | 21,820 | −3.9 | 89 | −4.9 | 1,594 | −16.0 | 6 | −16.9 | 20,226 | −2.8 | 82 | −3.8 |

| 2015 | 21,483 | −1.5 | 87 | −2.5 | 1,797 | 12.7 | 7 | 11.6 | 19,687 | −2.7 | 79 | −3.6 |

| % change, 2000–2015 | — | 138.9† | — | 102.2† | — | −70.0† | — | −74.6† | — | 556.4† | — | 455.7† |

| Year | Total smokeless (chewing tobacco and snuff [lbs])

|

Chewing tobacco (lbs)

|

Snuff (lbs)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (millions) | % change | Per capita | % change | Total (millions) | % change | Per capita | % change | Total (millions) | % change | Per capita | % change | |

| 2000 | 111,746 | — | 0.533 | — | 45,594 | — | 0.217 | — | 66,152 | — | 0.315 | — |

| 2001 | 119,316 | 6.8 | 0.562 | 5.5 | 49,500 | 8.6 | 0.233 | 7.3 | 69,816 | 5.5 | 0.329 | 4.3 |

| 2002 | 118,564 | −0.6 | 0.552 | −1.7 | 47,311 | −4.4 | 0.220 | −5.5 | 71,253 | 2.1 | 0.332 | 0.9 |

| 2003 | 120,790 | 1.9 | 0.556 | 0.8 | 46,080 | −2.6 | 0.212 | −3.6 | 74,709 | 4.9 | 0.344 | 3.7 |

| 2004 | 121,149 | 0.3 | 0.552 | −0.8 | 43,149 | −6.4 | 0.197 | −7.4 | 78,000 | 4.4 | 0.355 | 3.2 |

| 2005 | 119,452 | −1.4 | 0.538 | −2.5 | 39,199 | −9.2 | 0.177 | −10.2 | 80,253 | 2.9 | 0.361 | 1.8 |

| 2006 | 125,738 | 5.3 | 0.560 | 4.1 | 39,098 | −0.3 | 0.174 | −1.4 | 86,640 | 8.0 | 0.386 | 6.7 |

| 2007 | 123,672 | −1.6 | 0.544 | −2.8 | 35,304 | −9.7 | 0.155 | −10.8 | 88,368 | 2.0 | 0.389 | 0.8 |

| 2008 | 128,265 | 3.7 | 0.558 | 2.5 | 33,446 | −5.3 | 0.145 | −6.4 | 94,819 | 7.3 | 0.412 | 6.0 |

| 2009 | 125,479 | −2.2 | 0.540 | −3.2 | 30,425 | −9.0 | 0.131 | −10.0 | 95,054 | 0.2 | 0.409 | −0.8 |

| 2010 | 127,527 | 1.6 | 0.542 | 0.5 | 27,615 | −9.2 | 0.117 | −10.3 | 99,912 | 5.1 | 0.425 | 3.9 |

| 2011 | 128,363 | 0.7 | 0.540 | −0.4 | 24,801 | −10.2 | 0.104 | −11.1 | 103,562 | 3.7 | 0.436 | 2.6 |

| 2012 | 132,351 | 3.1 | 0.551 | 2.0 | 24,146 | −2.6 | 0.101 | −3.7 | 108,205 | 4.5 | 0.451 | 3.4 |

| 2013 | 135,440 | 2.3 | 0.558 | 1.3 | 22,434 | −7.1 | 0.092 | −8.0 | 113,007 | 4.4 | 0.466 | 3.4 |

| 2014 | 136,333 | 0.7 | 0.556 | −0.5 | 21,965 | −2.1 | 0.090 | −3.2 | 114,368 | 1.2 | 0.466 | 0.1 |

| 2015 | 137,581 | 0.9 | 0.555 | −0.1 | 20,156 | −8.2 | 0.081 | −9.2 | 117,425 | 2.7 | 0.473 | 1.6 |

| % change, 2000–2015 | — | 23.1† | — | 4.2 | — | −55.8† | — | −62.6† | — | 77.5† | — | 50.3† |

Adults aged ≥18 years as reported annually by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Statistically significant (p<0.05) based on Joinpoint analysis.

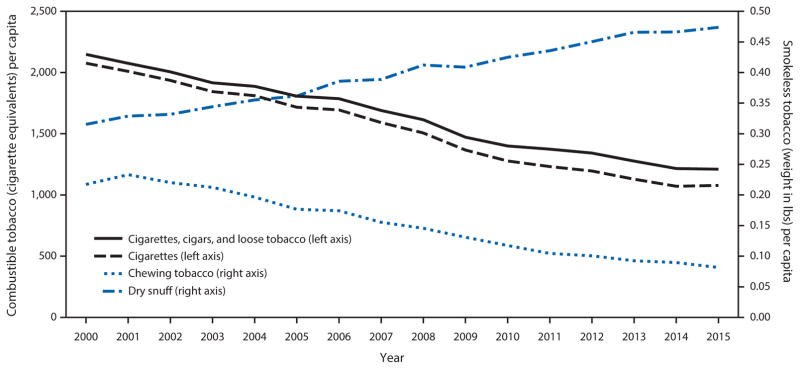

During 2000–2015, total cigarette consumption decreased 38.7% from 435.6 billion to 267.0 billion cigarettes (p<0.05) (Table), a per capita decrease of 48.1% from 2,076 to 1,078 cigarettes (p<0.05) (Figure 1). Total cigarette consumption was 267.0 billion cigarettes in 2015 compared with 262.7 billion in 2014, or seven more cigarettes per capita. In 2015, cigarettes accounted for 89% of total combustible tobacco consumption.

FIGURE 1. Consumption of combustible* and smokeless tobacco† — United States, 2000–2015.

*Combustible tobacco includes cigarettes, cigars, and loose roll-your-own and pipe tobacco, and is measured as cigarette equivalents per capita.

†Smokeless tobacco includes chewing tobacco and dry snuff, and is measured as weight (lbs) per capita.

During 2000–2015, total roll-your-own tobacco consumption decreased 70.0% (p<0.05), whereas total pipe tobacco consumption increased 556.4% (p<0.05) (Table). The largest changes occurred during 2008–2011, when roll-your-own consumption decreased from 10.7 billion to 2.6 billion cigarette equivalents (75.7% decrease, p<0.05), while pipe tobacco consumption increased from 2.6 billion to 17.5 billion cigarette equivalents (573.1% increase; p<0.05).

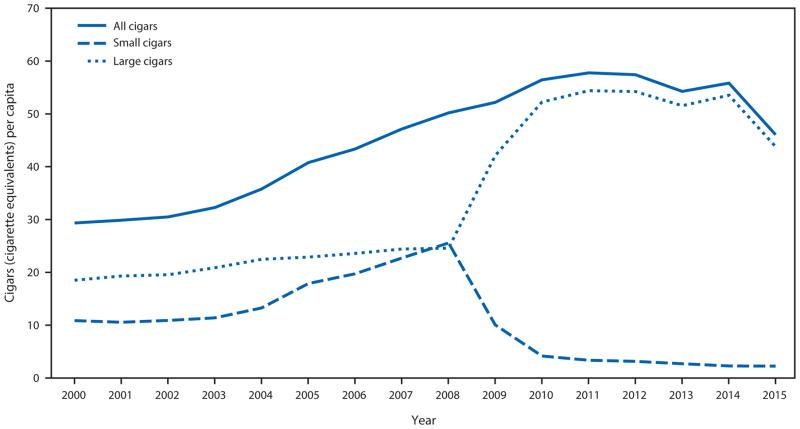

During 2000–2015, total small cigar§ consumption decreased 75.6% (p<0.05), or 79.3% per capita (p<0.05). However, large cigar consumption increased 179.6% (p<0.05), or 136.8% per capita (p<0.05) (Table) (Figure 2). Large and small cigar consumption diverged in 2008; large cigar consumption increased during 2008–2011 (p<0.05), whereas small cigar consumption decreased during 2008–2015 (p<0.05).

FIGURE 2. Consumption of cigars* — United States, 2000–2015.

*Cigars are measured as cigarette equivalents per capita. Small cigars are defined as cigars that weigh ≤3 lbs (1.36 kg) per 1,000 cigars, and large cigars are defined as cigars that weigh >3 lbs per 1,000 cigars.

During 2000–2015, total smokeless tobacco consumption increased 23.1% (p<0.05), or 4.2% per capita (Table) (Figure 1). However, chewing tobacco and snuff consumption patterns diverged; total chewing tobacco consumption decreased 55.8% from 45.6 to 20.2 billion pounds (from 20.7 to 9.2 billion kilograms) (p<0.05), whereas total snuff consumption increased 77.5% from 66.2 to 117.4 billion pounds (from 30.0 to 53.3 billion kilograms) (p<0.05).

Discussion

During 2000–2015, combustible tobacco consumption declined overall, and total and per capita cigarette consumption declined each year during 2000–2014. However, during 2015, the number of cigarettes consumed was higher than during 2014, the first time annual cigarette consumption was higher than the previous year since 1973. Because cigarettes remained the most commonly used combustible tobacco product, this offset decreases in pipe tobacco and cigar consumption, slightly increasing total combustible tobacco consumption in 2015 relative to 2014. Furthermore, total smokeless tobacco consumption increased during 2000–2015, in part because of the steady increase in snuff consumption. Sustained implementation of proven tobacco prevention and control strategies is critical to reduce the use of tobacco product consumption in the United States.

The reason for higher cigarette consumption in 2015 compared with 2014 is uncertain. It might be attributable, in part, to changing U.S. economic conditions; increased electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use; or dual use of conventional cigarettes and e-cigarettes, which could contribute to continued consumption among smokers who do not quit smoking completely (1,7). Continued monitoring is needed to evaluate the presence of a long-term trend. Research is warranted to assess how gross domestic product, unemployment, and other economic indicators might affect cigarette consumption, cessation, and initiation. Further research on the affect of e-cigarette use on patterns of conventional cigarette smoking, including consumption and dual use, could also help inform public health policy, planning, and practice.

Smokeless tobacco consumption has modestly increased during 2000–2015. These data provide insight into the diverging pattern of smokeless tobacco product consumption; during 2000–2015, the decline in chewing tobacco consumption was offset by a steady increase in snuff consumption. This increase might be attributable to advertising and promotion of these products. In 2013, tobacco companies spent $410.9 million promoting moist snuff, compared with $11.8 million for loose leaf chewing tobacco, $234,000 for plug/twist chewing tobacco, $485,000 for scotch/dry snuff, and $51.2 million for snus.¶ These findings underscore the importance of sustained efforts to monitor and reduce all forms of smokeless tobacco product use in the United States.

Recent changes in consumption patterns, particularly in large cigar and pipe tobacco use, have continued through 2015. Previous studies show that the tobacco industry adapted the marketing of roll-your-own products and designed cigars to minimize the burden of the federal excise tax, and thus, reduced these tobacco products’ cost to the consumer (8–10). Because of these changes, roll-your-own tobacco was labeled and sold as lower-taxed pipe tobacco, and cigarette-like cigars were classified as lower-taxed large cigars (8,10). However, although consumption of pipe tobacco and cigars increased dramatically during 2009–2011, those product categories declined in recent years. There have been federal and state efforts to address product-switching tax avoidance activities (9,10). For example, a federal law** requires retailers to register as cigarette manufacturers if they offer consumers use of cigarette rolling machines (10). States have also taken steps to classify such retailers as manufacturers (9). Further evaluation and monitoring of these and other tax avoidance strategies could be beneficial at the state and national level, including monitoring any changes in consumption patterns that might emerge as tobacco product regulatory actions are implemented at the federal level.††

The findings in this report are subject to at least four limitations. First, the measure for cigarette and combustible tobacco consumption does not account for illicit cigarette sales, such as those smuggled into or out of the country, or for untaxed cigarettes that are produced or sold on American Indian sovereign lands. Currently, no method exists for measuring or estimating illicit or untaxed tobacco trade in the United States. Second, it was not possible to assess consumption of other tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, hookah, or dissolvable tobacco, because federal taxes are not reported for those products. Third, sales data do not provide information on consumer demographics (e.g., age). Finally, sales data might not reflect actual consumption, because all purchased products might not be used by the consumer because of loss, damage, or tobacco cessation.

The overall decline in cigarette consumption is a pattern that has persisted in the United States since the 1960s (1). However, notable shifts have occurred in the tobacco product landscape in recent years, including an upward trend in consumption during 2014–2015. Smokeless tobacco consumption also increased steadily during 2000–2015. These changes in overall tobacco consumption demonstrate the importance of sustained tobacco prevention and control interventions, including price increases, comprehensive smoke-free policies, aggressive media campaigns, and increased access to cessation services (5). To further reduce tobacco product appeal and access, emerging strategies, such as prohibiting the sale of flavored tobacco products or increasing the legal age of tobacco purchase to 21 years, might also be beneficial.§§ The implementation of evidence-based strategies addressing the diversity of tobacco products consumed in the United States can reduce tobacco-related disease and death.

Summary.

What is already known about this topic?

Combustible and smokeless tobacco use causes adverse health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease and multiple types of cancer. Cigarette consumption in the United States has declined overall since the 1960s, but consumption of other tobacco products has not.

What is added by this report?

During 2000–2015, total combustible tobacco consumption decreased 33.5%. Although total cigarette consumption decreased 38.7%, cigarettes remained the most commonly used combustible tobacco product. Notably, total cigarette consumption was 267.0 billion cigarettes in 2015 compared with 262.7 billion in 2014, or seven more cigarettes per capita. Consumption of noncigarette combustible tobacco (cigars, roll-your-own, pipe tobacco) increased 117.1%, or 83.8% per capita, during 2000–2015. For smokeless tobacco, total consumption increased 23.1%, or 4.2% per capita.

What are the implications for public health practice?

These changes in tobacco consumption demonstrate the importance of sustained tobacco prevention and control interventions, including price increases, comprehensive smoke-free policies, aggressive media campaigns, and increased access to cessation services. The implementation of evidence-based strategies addressing the diversity of tobacco products consumed in the United States can reduce tobacco-related disease and death.

Footnotes

0.0325 oz (0.9 g) = one cigarette. The conversion of 0.0325 oz (0.9 g) = one cigarette was cited in the 1998 Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement (http://ag.ca.gov/tobacco/pdf/1msa.pdf).

In 26 USC 5701, small cigars are defined as cigars that weigh ≥3 pounds (1.36 kg) per 1,000 cigars, and large cigars are defined as cigars that weigh >3 pounds per 1,000.

Federal Trade Commission Smokeless Tobacco Report for 2013. https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-smokeless-tobacco-report-2013/2013tobaccorpt.pdf.

Congress. Pub. L. No. 112-141, 2012. Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act of 2012 (MAP-21). http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-112hr4348enr/pdf/BILLS-112hr4348enr.pdf.

On May 5, 2016, the Food and Drug Administration finalized a rule extending its authority to all tobacco products, including cigars and pipe tobacco. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/05/10/2016-10685/deeming-tobacco-products-to-be-subject-to-the-federal-food-drug-and-cosmetic-act-as-amended-by-the.

Some communities, including New York City, New York, Chicago, Illinois, and Providence, Rhode Island, have prohibited the sale of flavored tobacco products. Furthermore, California, Hawaii and at least 200 communities have raised the legal age for purchasing tobacco to 21 years. More information can be found at Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/content/what_we_do/state_local_issues/sales_21/states_localities_MLSA_21.pdf.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2014. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/full-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Volume 89: smokeless tobacco and some tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol89/mono89.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatziandreu EJ, Pierce JP, Fiore MC, Grise V, Novotny TE, Davis RM. The reliability of self-reported cigarette consumption in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1020–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.8.1020. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.79.8.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. Consumption of cigarettes and combustible tobacco—United States, 2000–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:565–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs—2014. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best_practices/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. Tobacco statistics. Washington, DC: US Department of Treasury, Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau; 2016. http://www.ttb.gov/tobacco/tobacco-stats.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 7.King BA, Patel R, Nguyen KH, Dube SR. Trends in awareness and use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010–2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:219–27. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntu191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Government Accountability Office. Tobacco taxes: large disparities in rates for smoking products trigger significant market shifts to avoid higher taxes. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office; 2012. http://www.gao.gov/products/gao-12-475. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris DS, Tynan MA. Fiscal and policy implications of selling pipe tobacco for roll-your-own cigarettes in the United States. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036487. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tynan MA, Morris D, Weston T. Continued implications of taxing roll-your-own tobacco as pipe tobacco in the USA. Tob Control. 2015;24:e125–7. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]