Abstract

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) are environmental carcinogens implicated as causes of cancer in certain industrial settings and in cigarette smokers. PAH require metabolic activation to exert their carcinogenic effects. One widely accepted pathway of metabolic activation proceeds through formation of “bay region” diol epoxides which are highly reactive with DNA and can cause mutations. Phenanthrene (Phe) is the simplest PAH with a bay region and an excellent model for the study of PAH metabolism. In previous studies in which [D10]Phe was administered to smokers, we observed higher levels of [D10]Phe-tetraols derived from [D10]Phe-diol epoxides in subjects who were null for the glutathione-S-transferase M1 (GSTM1) gene. We hypothesized that Phe-epoxides, the primary metabolites of Phe, were detoxified by glutathione conjugate formation, which would result ultimately in the excretion of the corresponding mercapturic acids in urine. We synthesized the four stereoisomeric mercapturic acids that would result from attack of glutathione on Phe-epoxides followed by normal processing of the conjugates. We also synthesized the corresponding dehydrated metabolites and sulfoxides. These 12 standards were used in liquid chromatography-nanoelectrospray ionization-high resolution tandem mass spectrometry analysis of urine samples from smokers and creosote workers, the latter exposed to unusually high levels of PAH. Only the sulfoxide derivatives were consistently detected in the urine of creosote workers; none of the compounds was detected in the urine of smokers. These results demonstrate a new pathway of PAH-mercapturic acid formation, but do not provide an explanation for the role of GSTM1 null status on Phe-tetraol formation.

Keywords: phenanthrene metabolism, mercapturic acids, human urine

1. Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) are ubiquitous environmental pollutants formed during the incomplete combustion of organic matter. Multiple epidemiologic studies have investigated the relationship between exposure to PAH in occupational settings and the incidence of cancer [1]. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded that there is sufficient evidence for the carcinogenicity to humans of occupational exposures which occur during coal gasification, coke production, coal-tar distillation, chimney sweeping, paving and roofing with coal-tar pitch, aluminum production, and carbon electrode manufacturing, all of which can entail considerable exposure to PAH [1]. Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP), the prototypic powerful PAH carcinogen, is also considered carcinogenic to humans by IARC [1]. Cigarette smoke is another significant source of PAH exposure, and these compounds are considered to be among the principal causes in smokers of lung cancer, a disease which kills 1.42 million people per year in the world [2–4].

PAH require metabolism to exert their carcinogenic effects [5–8]. Three general mechanisms of PAH metabolic activation have been studied in great detail: activation through the formation of bay region diol epoxides [5–7], through radical cation intermediates [9], or through redox cycling [10]. The study described here focuses on the bay region diol epoxide mechanism. Phenanthrene (Phe, 1, Scheme 1) is the simplest PAH with a bay region. Although not carcinogenic, its structural features are ideal for investigating the role of bay region diol epoxides which are readily formed during its metabolism, as shown in Scheme 1 [11–14]. Thus, convincing evidence indicates that P450s stereoselectively catalyze the oxidation of the angular ring of Phe to Phe-1,2-epoxide (2) and Phe-3,4-epoxide (12), which are stereoselectively hydrated with catalysis by epoxide hydrolase (EH) to give Phe-(1R,2R)-diol (3) and Phe-(3R,4R)-diol (19), established metabolites of Phe [15]. Further stereoselective oxidation of 3 and 19 by P450s produces the bay region diol epoxide Phe-(1R,2S)-diol-(3S,4R)-epoxide (4) and the “reverse diol epoxide” Phe-(3S,4R)-diol-(1R,2S)-epoxide (20), which upon hydrolysis give tetraols 5 and 21, respectively. Alternatively, the simple epoxides 2 and 12 could be detoxified by reaction with glutathione ultimately producing sets of mercapturic acids such as 6, 9, 13, 16 and 7, 10, 14, 17 as well as their further oxidation products 8, 11, 15, 18. For the reasons described below, the possible metabolic formation of these three sets of mercapturic acid products is the focus of this study.

Scheme 1.

Metabolism of phenanthrene (Phe) to intermediates and products discussed in the text. Stereoselectivity in the formation of Phe epoxides and subsequent metabolites has been established based on previous studies (see for example [14], [15] and [16]). Compounds 6, 9, 13, 16; 7, 10, 14, 17; and 8, 11, 15, 18 synthesized here were racemic mixtures.

Only 11% of female and 24% of male lifetime cigarette smokers will get lung cancer by age 85 or greater, and this relatively small percentage is not due to competing causes of death from smoking [17]. A major goal of our research is to identify these susceptible smokers who could then be targeted for surveillance and early detection of lung cancer. We hypothesize that smokers who extensively metabolically activate PAH by the diol epoxide pathway will be at higher risk for lung cancer, all other factors considered equal. As a test of this hypothesis, we are administering [D10]phenanthrene ([D10]Phe, a single dose of 1 – 10 μg) to smokers and analyzing the amounts of [D10]Phe-tetraols 5 and 21 excreted in 6h urine, a protocol which has been previously validated [18–20]. The use of [D10]Phe allows us to focus only on the metabolic activation process, setting aside exposure variables such as diet and polluted air which contain Phe and would complicate the interpretation of levels of unlabeled Phe-tetraols 5 and 21 excreted by smokers.

In one study of subjects to whom [D10]Phe was administered, we found that individuals who were null for the GSTM1 gene, among 12 genetic polymorphisms tested, had a significantly higher approximately doubled level of [D10]Phe-tetraols 5 and 21 than did those who were GSTM1 competent [18]. The simplest explanation for this phenomenon would be that GSTM1 catalyzes the detoxification of Phe-diol epoxides 4 and 20, competing with tetraol formation; therefore the null individuals would have higher levels of [D10]Phe-tetraols 5 and 21. However, we have previously analyzed smokers’ urine for the mercapturic acids which would be formed by GST-catalyzed detoxification of 4 and 20, and found that formation of these mercapturic acids was only a minor pathway, with levels less than 14% of the amounts of Phe-tetraols 5 and 21 [19;21]. These results indicated that interception of Phe-diol epoxides 4 and 20 by GSTs was not the reason for the higher Phe-tetraol levels in the GSTM1-null individuals. Therefore, in the study reported here, we have investigated the role of GSTs in the detoxification of Phe-1,2-epoxide (2) and Phe-3,4-epoxide (12), as interception of these simple Phe-epoxides at an earlier point in the metabolic process leading to Phe-tetraols 5 and 21 could also explain the observation that GSTM1-null individuals had higher [D10]Phe-tetraol levels in their urine. We synthesized the anticipated mercapturic acid products 6, 9, 13, and 16 which would arise from GST-catalyzed detoxification of Phe-epoxides 2 and 12, as well as the corresponding dehydrated mercapturic acids 7, 10, 14, and 17, and sulfoxides 8, 11, 15, and 18. We then analyzed urine samples for these metabolites using liquid chromatography-nanoelectrospray-high resolution tandem mass spectrometry (LC-NSI-HRMS/MS).

1. Materials and Methods

1.1. Chemicals

All reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

1.2. General Synthetic Methods

Racemic phenanthrene-1,2-epoxide (2) and phenanthrene-3,4-epoxide (12) were prepared as previously described [22]. Compounds 6, 9, 13, and 16 (each as a mixture of unseparable diastereomers) were synthesized by reaction of the epoxides 2 and 12 with N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC). Briefly, 150 mg of the epoxide was dissolved in 200 μL THF and added to a solution of 32 mg of KOH and 59 mg of NAC in 200 μL of MeOH kept at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred for 1 h at 0 °C and then was brought to room temperature and stirred overnight. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, the residue was dissolved in 1 mL H2O and extracted with 1 mL ethyl acetate 3 times. The products were purified by HPLC, and the concentrations of 9, 13, and 16 were quantified by NMR essentially as described previously [23]. Compound 6 was quantified by MS/MS, by comparison to compound 9.

Compounds 7, 10, 14, and 17 were prepared by dehydrating compounds 6, 9, 13, and 16, respectively, by treatment with formic acid. Briefly, 500 μg of the starting material was dissolved in 1 mL H2O and 100 μL HCOOH was added at 50 °C. The mixture was stirred for 1 h, and then the pH was adjusted to 7 with NH4OH. The mixture was purified by HPLC to obtain the desired products. The identities of the resulting products were confirmed by LC-NSI-HRMS/MS.

Compounds 8, 11, 15 and 18 were synthesized by dissolving the mercapturic acids 7, 10, 14, and 17 (0.158 mg) in glacial acetic acid (1 mL) and adding a 30% solution of H2O2 (1 μL) at 4 °C. The mixture was stirred for 1 h. The progress of the reaction was monitored by HPLC. After stirring overnight, all the starting material was converted to the corresponding sulfoxide. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was redissolved in 15 mM NH4OAc. The crude mixture was purified by HPLC to give the corresponding products. The identity of the compounds was confirmed by NMR and/or LC-NSI-HRMS/MS.

Purification of the mercapturic acids

Purification of 6, 7, 9, 10, 13, 14, 16, and 17 via HPLC was carried out using an Agilent 1100 capillary flow instrument with a diode array UV detector operated at 254 nm (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). A 250 × 10 mm, 5 μm, C18 Luna column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) was eluted with 75% 15 mM NH4OAc and 25% CH3CN at a flow rate of 1 mL/min.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) characterization of the mercapturic acids

The synthesized compounds were analyzed using a Finnigan TSQ Quantum Discovery instrument (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA) coupled to an Agilent 1100 Capillary HPLC system. The MS was operated in the negative ion ESI mode. A 250 × 10 mm, 5 μm, C18 Luna column and a Krudkatcher disposable precolumn filter (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) were used. The column was eluted at 10 μL/min with a linear gradient of CH3CN in 15 mM NH4OAc. CH3CN was brought from 15% to 75% in 30 min, then the organic solvent was held at 75% for 5 min followed by a 14 min reequilibration at 15% CH3CN. The ESI source was set in the negative ion mode as follows: voltage 5 kV; current 50 μA; heated ion transfer tube 330 °C. The metabolites were measured by MS/MS using selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mode. The collision energy for all transitions was 15 eV, and the Ar collision gas pressure was 1.0 mTorr. The MS settings of the ion source were optimized using standard solutions of compounds 6 and 9, 7 and 10, and 8 and 11 to produce maximum MS/MS signals at m/z 356 → m/z 209, m/z 338 → 209 and m/z 354 → 225, respectively.

LC-NSI-HRMS/MS

The identity of the compounds was confirmed using a Nano LC-Ultra 2D HPLC (Eksigent, Dublin, CA) system equipped with a 5 μL injection loop, coupled with a LTQ Orbitrap Velos (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Separation was performed with a capillary column (75 μm ID, 10 cm length, 15 μm orifice) created by hand-packing a commercially available fused-silica emitter (New Objective, Woburn MA) with 5 μm Luna C18 bonded separation media (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). The column was eluted at 1 μL/min with 15% CH3CN in 5 mM NH4OAc for the first 5 min, then the flow was changed to 300 nL/min with a 15 min linear gradient from 15% to 45% CH3CN followed by a 2 min hold at 90% CH3CN to wash the column before returning to initial conditions. An injection volume of 2 μL per sample was used for the analysis.

The NSI source voltage was set at 2.3 kV, the capillary temperature was 350 °C, and the metabolites were quantified by HRMS/MS-selected reaction monitoring. Compounds 6, 9, 13 and 16 were analyzed in negative mode monitoring for the transition 356 m/z → 209.0430 m/z. The dehydrated compounds 7, 10, 14, and 17 and the sulfoxide derivatives 8, 11, 15, and 18, were analyzed in positive mode monitoring for the transitions m/z 340 → m/z 209.0419 and m/z 356 → m/z 209.0419 respectively. The analysis was performed with accurate mass monitoring of fragment ions at 5 ppm tolerance utilizing the Orbitrap detector. These two parallel reaction monitoring events were performed using the HCD collision cell with 1 amu isolation width, collision energy of 50 and resolution set at 30,000 (at 400 amu) with an actual resolution of 55,000 (at 340 amu and 356 amu). A full scan event was also performed over a 100 – 500 amu range at a resolution setting of 30,000 to monitor for the accurate mass at 5 ppm of the protonated precursor ion of the analyte m/z 340.1002 and m/z 356.0951 to confirm analyte identity.

1.3. Spectral Data

1-(N-acetylcysteinyl)-2-hydroxy-1,2-dihydrophenanthrene (6). HRMS (NSI−) m/z calc’d 356.0962 [M – H]−, 338.0856 [M – H – H2O]−, 227.0536 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3]−, 209.0430 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3– H2O]−, and 162.0230 [M – C14H11O]−; found m/z (relative intensity, %) 356.0963 (precursor ion), 338.0858 (5%), 227.0538 (20%), 209.0434 (100%), and 162.0233 (10%).

2-(N-acetylcysteinyl)-1-hydroxy-1,2-dihydrophenanthrene (9). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 8.27 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1 H, C8-H), 7.90 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1 H, C5-H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1 H, C9-H), 7.48–7.57 (m, 3 H, C10-H, C6-H, and C7-H), 7.37 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1 H, C4-H), 6.66 (br. s., 1 H, N-H), 6.20 (dd, J = 10.2, 5.0 Hz, 1 H, C3-H), 5.84 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1 H, C1-OH), 4.77 (m, 1 H, C1-H), 3.94 (m, 1 H, -CH-COO), 3.72–3.76 (m, 1 H, C2-H), 3.04 (dd, J = 12.7, 5.0 Hz, 1 H, -S-CH2), 2.81 (dd, J = 12.7, 6.0 Hz, 1 H, -S-CH2′), 1.83 (s, 3 H, -CO-CH3). COSY and HSQC spectra were consistent with these assignments. HRMS (NSI−) m/z calc’d 356.0962 [M – H]−, 338.0856 [M – H – H2O]−, 227.0536 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3]−, 209.0430 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3 – H2O]−, and 162.0230 [M – C14H11O]−; found m/z (relative intensity, %) 356.0961 (precursor ion), 338.0859 (4%), 227.0538 (21%), 209.0431 (100%), and 162.0234 (11%).

3-(N-acetylcysteinyl)-4-hydroxy-3,4-dihydrophenanthrene (13). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 8.21 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1 H, C8-H), 7.88 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1 H, C5-H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1 H, C9-H), 7.56 (m, 1 H, C7-H), 7.47 (m, 1 H, C6-H), 7.35 (m, 1 H, C10-H), 6.62 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1 H, C1-H), 6.30 (br. s., 1 H, N-H), 6.13 (dd, J = 9.2, 5.8 Hz, 1 H, C2-H), 5.42 (s, 1 H, C4-H), 3.91 (m, 1 H, -CH-COO), 3.85 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 1 H, C3-H), 2.99 (dd, J = 12.4, 4.4 Hz, 1 H, -S-CH2), 2.90 (dd, J = 12.5, 5.8 Hz, 1 H, -S-CH2′), 1.80 (s, 3 H, -CO-CH3). COSY and HSQC spectra were consistent with these assignments. HRMS (NSI−) m/z calc’d 356.0962 [M – H]−, 338.0856 [M – H – H2O]−, 227.0536 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3]−, 209.0430 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3 – H2O]−, and 162.0230 [M – C14H11O]−; found m/z (relative intensity, %) 356.0961 (precursor ion), 338.0858 (4%), 227.0538 (23%), 209.0433 (100%), and 162.0235 (11%).

4-(N-acetylcysteinyl)-3-hydroxy-3,4-dihydrophenanthrene (16). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 8.40 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1 H, C8-H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1 H, C5-H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1 H, C9-H), 7.55–7.60 (m, 1 H, C7-H), 7.43–7.50 (m, 1 H, C6-H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1 H, C10-H), 6.85 (br. s., 1 H, N-H), 6.67 (d, J = 9.5 Hz, 1 H, C1-H), 6.15 (dd, J = 9.5, 5.2 Hz, 1 H, C2-H), 5.08 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H, C3-OH), 4.87 (s, 1 H, C4-H), 4.40–4.44 (m, 1 H, C3-H), 3.88–3.95 (m, 1 H, -CH-COO), 3.19 (dd, J = 12.8, 4.9 Hz, 1 H, -S-CH2), 3.02 (dd, J = 13.1, 4.6 Hz, 1 H, -S-CH2′), 1.84 (s, 3 H, -CO-CH3). COSY and HSQC spectra were consistent with these assignments. HRMS (NSI−) m/z calc’d 356.0962 [M – H]−, 338.0856 [M – H – H2O]−, 227.0536 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3]−, 209.0430 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3 – H2O]−, and 162.0230 [M – C14H11O]−; found m/z (relative intensity, %) 356.0961 (precursor ion), 338.0857 (4%), 227.0537 (18%), 209.0432 (100%), and 162.0235 (10%).

1-(N-acetylcysteinyl)phenanthrene (7). HRMS (NSI+) m/z calc’d 340.1002 [M + H]+, 235.0576 [M – COOH – NH2COCH3]+, 209.0419 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3]+, 162.0219 [M – C14H9]+, and 130.0499 [M – C14H9S]+; found m/z (relative intensity, %) 340.1000 (precursor ion), 235.0576 (45%), 209.0420 (100%), 162.0220 (8%), and 130.0498 (6%).

2-(N-acetylcysteinyl)phenanthrene (10). HRMS (NSI+) m/z calc’d 340.1002 [M + H]+, 235.0576 [M – COOH – NH2COCH3]+, 209.0419 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3]+, 162.0219 [M – C14H9]+, and 130.0499 [M – C14H9S]+; found m/z (relative intensity, %) 340.1002 (precursor ion), 235.0576 (53%), 209.0417 (100%), 162.0220 (7%), and 130.0498 (6%).

3-(N-acetylcysteinyl)phenanthrene (14). HRMS (NSI+) m/z calc’d 340.1002 [M + H]+, 235.0576 [M – COOH – NH2COCH3]+, 209.0419 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3]+, 162.0219 [M – C14H9]+, and 130.0499 [M – C14H9S]+; found m/z (relative intensity, %) 340.1001 (precursor ion), 235.0571 (42%), 209.0415 (100%), 162.0216 (8%), and 130.0496 (5%).

4-(N-acetylcysteinyl)phenanthrene (17). HRMS (NSI+) m/z calc’d 340.1002 [M + H]+, 235.0576 [M – COOH – NH2COCH3]+, 209.0419 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3]+, 162.0219 [M – C14H9]+, and 130.0499 [M – C14H9S]+; found m/z (relative intensity, %) 340.1002 (precursor ion), 235.0570 (39%), 209.0414 (100%), 162.0215 (7%), and 130.0495 (5%).

1-(N-acetylcysteinyl)phenanthrene sulfoxide (8). HRMS (NSI+) m/z calc’d 356.0951 [M + H]+, 235.0576 [M – COOH – NH2COCH3– O]+, 225.0369 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3], 209.0419 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3– O]+, and 130.0499 [M – C14H9SO]+; found m/z (relative intensity, %) 356.0954 (precursor ion), 235.0571 (13%), 225.0363 (14%), 209.0414 (70%), and 130.0494 (100%).

2-(N-acetylcysteinyl)phenanthrene sulfoxide (11). HRMS (NSI+) m/z calc’d 356.0951 [M + H]+, 235.0576 [M – COOH – NH2COCH3– O]+, 225.0369 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3]+, 209.0419 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3– O]+, and 130.0499 [M – C14H9SO]+; found m/z (relative intensity, %) 356.0951 (precursor ion), 235.0572 (14%), 225.0365 (13%), 209.0416 (62%), and 130.0496 (100%).

3-(N-acetylcysteinyl)phenanthrene sulfoxide (15). Two diastereomers of 15 with respect to the sulfoxide chiral center were formed in equal quantities. Signals assigned to the corresponding diastereomeric protons are presented as δ/δ or as a range of the overlapping signals: 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 9.08/9.26 (s/s, 1 H, C4-H), 8.85/8.89 (d/d, J = 8.6 Hz/J = 8.5 Hz, 1 H, C5-H), 8.20/8.22 (d/d, J = 8.2 Hz/J = 8.2 Hz, 1 H, C1-H), 8.05–8.08 (m, 1 H, C8-H), 7.95–7.99 (m, 2 H, C9-H and C10-H), 7.92/8.02 (d/d, J = 8.5 Hz/J = 8.2 Hz, 1 H, C2-H), 7.75–7.80 (m, 1 H, C6-H), 7.69–7.75 (m, 1 H, C7-H), 6.68/7.28 (br. s./br. s., 1 H, -NH), 4.00/4.19 (m/m, 1 H, -CH-COO), 3.05–3.40 (m, 2 H, -S-CH2), 1.77/1.78 (s/s, 3 H, -CO-CH3). COSY spectra were consistent with the above assignments. HRMS (ESI−) m/z calc’d 354.0806 [M – H]− and 225.0380 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3]−; found 354.0809 (precursor ion) and 225.0382 (100%). HRMS (NSI+) m/z calc’d 356.0951 [M + H]+, 235.0576 [M – COOH – NH2COCH3– O]+, 225.0369 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3]+, 209.0419 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3– O]+, and 130.0499 [M – C14H9SO]+; found m/z (relative intensity, %) 356.0951 (precursor ion), 235.0573 (17%), 225.0366 (9%), 209.0417 (37%), and 130.0496 (100%).

4-(N-acetylcysteinyl)phenanthrene sulfoxide (18). HRMS (NSI+) m/z calc’d 356.0951 [M + H]+, 235.0576 [M – COOH – NH2COCH3– O]+, 225.0369 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3]+, 209.0419 [M – CH2CH(COOH)NHCOCH3– O]+, and 130.0499 [M – C14H9SO]+; found m/z (relative intensity, %) 356.0950 (precursor ion), 235.0573 (12%), 225.0365 (13%), 209.0416 (65%), and 130.0496 (100%).

Analyses of mercapturic acid conjugates and their sulfoxides in human urine

Urine samples

A pooled smokers’ urine sample was prepared by combining urine from 8 subjects, each of whom smoked about 20 cigarettes per day, and contributed between 150 and 320 mL from a 24 h urine collection. The smokers participated in ongoing studies at the University of Minnesota Tobacco Research Programs, approved by the Institutional Review Board. Urine samples from creosote workers were kindly provided by Dr. Mary Wolff (Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York). All samples were stored at −20 °C until analysis.

Analysis of urine

The pooled smokers’ urine sample was used as a positive control for method optimization. The sample (1 mL) was neutralized to pH 7 with NH4OH and loaded onto an Oasis MAX cartridge (1 mL, 30 mg, Waters) previously equilibrated using 1 mL MeOH, and 1 mL 2% aqueous NH4OH. The cartridge was then washed with the following solutions (% in H2O): 1 mL of 2% NH4OH, 1 mL MeOH, 1 mL 2% HCOOH, 1 mL 30% MeOH and 2% HCOOH, 1 mL 50% MeOH and 2% HCOOH. The cartridge was then eluted with four 1 mL aliquots of 90% MeOH and 2% HCOOH to collect the analytes. The four 1 mL fractions were combined and evaporated to dryness in a silanized vial on a Speedvac. The residue was dissolved in 20 μL of 15 mM NH4OAc, and 1–2 μL were analyzed by LC-NSI-HRMS/MS-negative mode for compounds 6, 9, 13, and 16, and positive mode for compounds 7, 10, 14 and 17, and 8, 11, 15, and 18. When purifying the samples for the analysis of compounds 7, 10, 14 and 17, the urine samples were added to 100 μL HCOOH and heated at 50 °C for 1 h, before following the protocol described above.

2. Results

We investigated the presence in human urine of twelve potential metabolites of Phe (1, Scheme 1) which could result from detoxification of Phe epoxides 2 and 12 by the mercapturic acid pathway: epoxide ring opening products 6, 9, 13, and 16; their dehydrated analogues 7, 10, 14, and 17; and the corresponding sulfoxides 8, 11, 15, and 18 (Scheme 1). Racemic Phe epoxides 2 and 12 were prepared as described [22]. Reaction of each epoxide with N-acetylcysteine produced the ring opened products 6, 9, 13, and 16 (each as a mixture of unseparable diastereomers). Treatment of these products with formic acid yielded the dehydrated compounds 7, 10, 14, and 17. Oxidation of these compounds with H2O2 in acetic acid provided the sulfoxides 8, 11, 15, and 18. Each standard was purified by HPLC and their structures were confirmed by 1H-NMR and/or HRMS/MS.

The synthesized compounds were used to optimize the conditions for analysis of these mercapturic acids in urine. A mixed-mode reversed-phase anion exchange (MAX) cartridge was used to desalt and enrich the mercapturic acid-containing fraction.

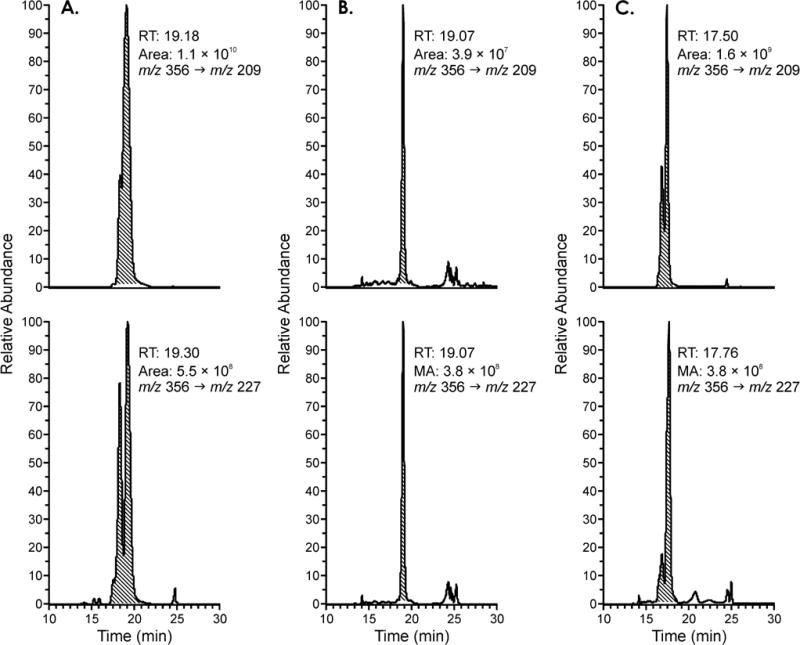

Standard solutions of compounds 13 and 16 in H2O (50 fmol/mL) were analyzed by LC-MS/MS in the negative ion mode. The following transitions were monitored: m/z 356 → m/z 209 and m/z 356 → m/z 227. These transitions correspond to loss of the mercapturate moiety, with or without dehydration of the resulting hydroxyphenanthrene fragment. The areas of the corresponding peaks, with retention times of 19.3 min, were measured and their ratio was 20:1, with the dehydration transition (m/z 356 → m/z 209) being strongly favored. This ratio of fragment ions was consistent across each of our standards 6, 9, 13, and 16. The presence of these compounds was investigated in the pooled smokers’ urine sample (4 mL). Peaks with the same retention time and MS transitions were observed, and the peaks co-eluted with the standards when co-injected, however the areas of the peaks corresponding to the two transitions monitored had a ratio of 1:10, as shown in Figure 1, indicating that these peaks were not mainly comprised of compounds 6, 9, 13, and 16. Further analysis of the same samples using LC-NSI-HRMS/MS in the negative ion mode which did not show any peak corresponding to the accurate mass of compounds 6, 9, 13 or 16 in the pooled smokers’ urine sample.

Figure 1.

Chromatograms obtained upon analysis of the pooled smokers’ urine sample for compounds 13 and 16 via LC-MS/MS in negative mode with monitoring for the transitions m/z 356 → m/z 209 (top channel) and m/z 356 → m/z 227 (bottom channel). Panel A) standard 13 and 16. The area ratio of the two peaks is of 20:1. Panel B) pooled smokers’ urine sample. The area ratio of the two peaks is 1:10. Panel C) co-injection of the pooled smokers’ urine sample and the standard.

We next investigated the possible presence in the pooled smokers’ urine sample of the dehydrated mercapturic acids 7, 10, 14, and 17. The urine was treated with HCOOH to cause dehydration of any 6, 9, 13, or 16 that might have been present, and analyzed using LC-NSI-HRMS/MS in positive ion mode. We could not confirm the presence of any peak corresponding to the accurate mass of the analyte. The same analysis was repeated following a more thorough purification of the pooled smokers’ urine sample using HPLC with the gradient which we used to purify the standards. Fractions were collected starting at 5 min, and 5 fractions of 5 min each were collected. The collected fractions were analyzed for the mercapturic acids 6, 9, 13, and 16 as well as their dehydrated analogues 7, 10, 14, and 17 using LC-NSI-HRMS/MS, but no corresponding trace was detected.

Creosote workers are exposed to far greater amounts of Phe than smokers. Therefore, to further investigate the existence of the mercapturic acid detoxification pathway of Phe epoxides in humans, we analyzed urine samples from six creosote workers for the dehydrated metabolites 7, 10, 14, and 17. Six samples (1 mL) were treated with acid and purified following the method optimized for analysis of 7, 10, 14 and 17 in smokers’ urine, followed by LC-NSI-HRMS/MS analysis in the positive ion mode.

This analysis of the transition for the expected mercapturic acids (compounds 7, 10, 14, and 17) revealed the presence of 14 in some samples, but not any other peak. However the transition for the corresponding sulfoxides 8, 11, 15, and 18, m/z 356.0951 → 209.04194 (positive ion mode), showed a clear signal in all samples. Recovery and detection limits for the sulfoxides were investigated. One mL aliquots of the pooled smokers’ urine sample were spiked with the sulfoxide standards 15 and 18 in increasing amounts: 50 fmol, 100 fmol, 250 fmol, 500 fmol, and 1000 fmol. The same amounts were also spiked into 1 mL H2O. The spiked samples were purified and enriched following the protocol optimized for the urine analysis, and analyzed by LC-NSI-HRMS/MS in the positive ion mode. The detection limit was 100 fmol of 15 or 18 per mL in urine, the on-column detection limit was approximately 10 fmol of each, and the overall recovery was 50% (in H2O) and 5% (in urine).

The presence of these compounds in 1 mL urine samples from 6 creosote workers, 2 nonsmokers, and the pooled smokers’ urine sample was investigated. Chromatograms from the analysis of a standard solution of sulfoxides 15 and 18 and from the analysis of a creosote workers’ urine sample are illustrated in Figure 2A, B. Sulfoxides 8 and 11 also coeluted with 15 and 18. A clear peak corresponding to the accurate mass of the analyte, matching the retention time of sulfoxide standards 8, 11, 15 and 18 was observed in all samples of creosote workers’ urine. Our standard solution of compound 15 showed two peaks, which suggests that the sulfoxide diastereomers were separated by HPLC. HPLC analysis of compound 18 also showed two peaks, and these were very similar in retention time to the diastereomers of 15. For this reason, it is unclear whether the two peaks in Figure 2B from the analysis of creosote workers’ urine correspond to 8, 11, 15, or 18, or a combination of these compounds, and quantitative analysis was not performed. These sulfoxides were not detected in the pooled smokers’ urine sample or in urine from non-smokers.

Figure 2.

Extracted ion chromatograms from LC-NSI-HRMS/MS analyses of sulfoxides and MS/MS fragmentation spectra. A) Analysis for sulfoxides 8, 11, 15, and 18 in creosote worker’s urine. B) Synthetic standard of sulfoxide 15. Proposed structures for the observed fragment ions are presented to the right.

3. Discussion

The results of this study do not support our hypothesis that GSTM1-null smokers would be less able to detoxify Phe-epoxides 2 and 12 than GSTM1-competent subjects, therefore leading to the observed higher levels of Phe-tetraols 5 and 21 previously observed in GSTM1-null smokers. We found no evidence for the existence of a GST detoxification pathway of Phe-epoxides 2 and 12 in smokers, with a detection limit of approximately 0.1 pmol/ml, which would correspond to less than 3% of the amounts of Phe-tetraols 5 and 21 typically found in smokers’ urine. We did however find convincing evidence for further oxidation of the anticipated mercapturic acids 7, 10, 14, and 17 in analyses of urine from creosote workers exposed to high levels of PAH, by detection of sulfoxides typified by 8, 11, 15, and 18, although these were also non-detectable in the urine of smokers. Taking these results together with our previous studies, neither GST detoxification of simple Phe-epoxides 2 and 12 nor of Phe-diol epoxides 4 and 20 can account for the observed higher levels of Phe-tetraols in GSTM1-null individuals.

It is possible of course that our previous observations regarding the effects of GSTM1 null status on levels of [D10]Phe-tetraols 5 and 21 after administration of [D10]Phe were due to chance [18]. The study involved only 25 subjects who received 10 μg [D10]Phe either orally or by smoking cigarettes to which [D10]Phe had been added so that the cigarettes delivered approximately the same dose of [D10]Phe as in the oral administration arm [19]. Nevertheless, we observed significantly higher levels of [D10]Phe-tetraols 5 and 21 in both plasma and urine of the 12 GSTM1 null subjects in that study, independent of the method of dosing, which adds considerable strength to the observation. In another study of Phe metabolism in 346 smokers who were genotyped for 11 polymorphisms in genes involved in PAH metabolism, including GSTM1, we found that the combination of CYP1A1I462V and GSTM1 null resulted in significantly higher levels of the ratio of Phe-tetraols to 3-hydroxy-Phe, an indicator of metabolic activation capacity [13]. We also observed that GSTM1 null status in that study resulted in a nearly significant (P = 0.07) increase in the Phe-tetraols to 3-hydroxy-Phe ratio. Collectively, these data strongly suggest that there is a genuine effect of GSTM1 null status on the metabolism of Phe to Phe-tetraols via the pathways illustrated in Scheme 1.

In the absence of convincing evidence for significant levels of detoxification of either the simple Phe-epoxides 2 and 12 or the diol epoxides 4 and 20 by the GST pathway, how can we account for the effect of GSTM1 null status on levels of Phe-tetraols 5 and 21? One possibility, not examined in this study, is further oxidation of the phenanthrene ring of the mercapturic acids 6, 9, 13, and 16 or 7, 10, 14, and 17. There is precedent for the existence of such products. For example, N-acetyl-S-(phenacyl)cysteine has been identified as a minor metabolite of styrene in both human and rat urine [24]. It is also possible that GSTM1 null status is in some way linked to other major pathways of Phe-epoxide or diol epoxide detoxification which were not thoroughly examined in this study.

Sulfoxides have been previously observed as human urinary metabolites of a number of compounds including acrylamide [25], furan [26], and the anti-cancer agent bendamustine [27]. These observations encouraged us to analyze for sulfoxides 8, 11, 15, and 18 in this study. We obtained convincing evidence for the presence of these metabolites in the urine of creosote workers, but quantitation is uncertain. The average amount of Phe-tetraols 5 plus 21 in 26 urine samples from creosote workers analyzed in a previous study was 837 ± 692 pmol/mL urine, whereas levels of Phe-tetraols 5 plus 21 in smokers’ urine averaged 4.60 pmol/mL [16]. Based on this ratio, we might expect only about 1/200th the amount of the sulfoxide metabolites in smokers’ urine as in creosote workers’ urine which may explain our inability to detect them in smokers’ urine.

The workers exposed to creosote in this study were dock workers who employed creosote, a distillate of coal tar, as a wood preservative. Creosote is comprised mainly of PAH, particularly the lower molecular weight compounds such as naphthalene and phenanthrene [1]. The major exposure to these compounds in the dock workers appears to have been through their skin [28–30]. The high exposure to PAH in creosote workers has been confirmed in multiple previous studies, mainly by analysis of 1-hydroxypyrene in urine [1]. Some studies have shown higher risks of skin cancer and lung cancer in creosote workers but the data are not consistent. The International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded that there is limited evidence in humans for the carcinogenicity of creosotes [1].

While extensive studies have investigated the detoxification of PAH diol epoxides by GSTs in various in vitro systems [31–35], there are to our knowledge only two reports, both from our laboratory, that have characterized human urinary mercapturic acids derived from PAH diol epoxides [19;21]. These reports quantified the mercapturic acid 22 derived from Phe-diol epoxide 20. The corresponding mercapturic acid from Phe-diol epoxide 4 was not detected. As mentioned earlier, the levels of 22 in smokers’ urine were quite low compared to the amounts of Phe-tetraols 5 and 21 [19;21]. We also characterized the mercapturic acid derived from Phe-9,10-epoxide in smokers’ urine (mean 0.058 pmol/mL urine), and its formation was related to GSTM1 status, being lower in the GSTM1-null individuals [36].

Collectively, our results indicate that mercapturic acid metabolites of phenanthrene, as well as the corresponding sulfoxides, are at most minor urinary metabolites in cigarette smokers. These results are surprising in view of the well-established activity of this pathway based on in vitro studies and the ease of detection of urinary mercapturic acids of other xenobiotics such as acrolein, acrylonitrile, and benzene [37]. One possible explanation for the low levels of these phenanthrene metabolites in human urine is that they are excreted mainly in feces, which were not collected or analyzed in this study.

The relationship between GST polymorphisms and PAH metabolism may be more complex than previously recognized. For example, in one recent study, we analyzed Phe tetraols 5 plus 21 in the urine of 2,097 cigarette smokers and found a highly significant relationship between number of GSTT1 copies and levels of these metabolites (P = 3.4 × 10−16). However, the relationship was in a different direction than might have been expected – the levels of 5 plus 21 were lowest in the nulls and increased with increasing copies of GSTT1, which is opposite to our observations with GSTM1 [38].

The synthesis of standards for this study was not trivial. Although the syntheses of the starting materials Phe-epoxides 2 and 12 have been previously reported [22], we note that these are multi-step methods resulting in relatively low overall yields. These syntheses start with tetrahydrophenanthrenones which must be prepared and separated to isolate the appropriate tetrahydrophenanthrenone precursor from linear byproducts. This is followed by reduction of the tetrahydrophenanthrenones to the corresponding alcohols, dehydration to dihydrophenanthrenes, bromination, hydrolysis of the resulting dibromide to provide bromohydrin precursors, conversion of these to trifluoroacetates which are then brominated to provide dibromo esters, the immediate precursors to the labile Phe-epoxides 2 and 12. Thus, considerable effort was invested in the preparation of the characterized standards 6, 9, 13, 16, 7, 10, 14, 17, 8, 11, 15, and 18 for this project.

In summary, we have carried out a thorough investigation of potential mercapturic acid formation from Phe-epoxides 2 and 12, using urine samples from cigarette smokers and creosote workers, the latter being exposed to unusually high levels of Phe and other PAH. Our results clearly demonstrate the existence of a new mercapturic acid pathway for PAH, illustrated by detection of sulfoxide metabolites. However, in most samples we were unable to detect the simple mercapturic acids hypothesized to be formed from Phe-epoxides 2 and 12, which might have helped to explain the influence of GSTM1 null status on levels of Phe-tetraols 5 and 21 in cigarette smokers.

Highlights.

Human urine was analyzed for mercapturic acids from phenanthrene epoxides.

The standards were synthesized from phenanthrene epoxides and N-acetylcysteine.

The corresponding sulfoxide metabolites were also prepared.

The sulfoxides were detected in the urine of highly exposed creosote workers.

None of the metabolites were detected in the urine of cigarette smokers.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

This study was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute [Grant CA-92025]. Mass spectrometry was carried out in the Analytical Biochemistry Shared Resource of the Masonic Cancer Center, supported in part by the U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute [Cancer Center Support Grant CA-77598].

Nonstandard abbreviations

- PAH

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- GSTM1

glutathione-S-transferase M1

- NAC

N-acetyl-L-cysteine

- LC-NSI-HRMS/MS

liquid chromatography-nanoelectrospray-high resolution tandem mass spectrometry

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatograpy-tandem mass spectrometry

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Vol. 92. IARC; Lyon, FR: 2010. Some Non-Heterocyclic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Some Related Exposures; pp. 35–818. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Vol. 83. IARC; Lyon, FR: 2004. Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart BW, Wild CP. World Cancer Report 2014. IARC; Lyon, FR: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexandrov LB, Ju YS, Haase K, Van Loo P, Martincorena I, Nik-Zainal S, Totoki Y, Fujimoto A, Nakagawa H, Shibata T, Campbell PJ, Vineis P, Phillips DH, Stratton MR. Mutational signatures associated with tobacco smoking in human cancer. Science. 2016;354:618–622. doi: 10.1126/science.aag0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dipple A, Moschel RC, Bigger CAH. Polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons. In: Searle CE, editor. Chemical Carcinogens. Second. American Chemical Society; Washington, D.C.: 1984. pp. 41–163. (ACS Monograph 182). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conney AH. Induction of microsomal enzymes by foreign chemicals and carcinogenesis by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: G.H.A. Clowes Memorial Lecture. Cancer Res. 1982;42:4875–4917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper CS, Grover PL, Sims P. The metabolism and activation of benzo[a]pyrene, Prog. Drug Metab. 1983;7:295–396. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luch A, Baird WM. Metabolic activation and detoxification of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. In: Luch A, editor. The carcinogenic effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Imperial College Press; London: 2005. pp. 19–96. [Google Scholar]

- 9.RamaKrishna NVS, Padmavathi NS, Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG, Cerny RL, Gross ML. Synthesis and structure determinaton of the adducts formed by electrochemical oxidation of the potent carcinogen dibenzo[a,l[pyrene in the presence of nucleosides. Chem Res Toxicol. 1993;6:554–560. doi: 10.1021/tx00034a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu D, Harvey RG, Blair IA, Penning TM. Quantitation of benzo[a]pyrene metabolic profiles in human bronchoalveolar (H358) cells by stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization mass spectrometry. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:1905–1914. doi: 10.1021/tx2002614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hecht SS, Chen M, Yagi H, Jerina DM, Carmella SG. r-1,t-2,3,c-4-Tetrahydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrophenanthrene in human urine: a potential biomarker for assessing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolic activation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:1501–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hecht SS, Chen M, Yoder A, Jensen J, Hatsukami D, Le C, Carmella SG. Longitudinal study of urinary phenanthrene metabolite ratios: effect of smoking on the diol epoxide pathway, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2969–2974. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hecht SS, Carmella SG, Yoder A, Chen M, Li Z, Le C, Jensen J, Hatsukami DK. Comparison of polymorphisms in genes involved in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolism with urinary phenanthrene metabolite ratios in smokers, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1805–1811. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hecht SS, Carmella SG, Villalta PW, Hochalter JB. Analysis of phenanthrene and benzo[a]pyrene tetraol enantiomers in human urine: relevance to the bay region diol epoxide hypothesis of benzo[a]pyrene carcinogenesis and to biomarker studies. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:900–908. doi: 10.1021/tx9004538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shou M, Korzekwa KR, Krausz KW, Crespi CL, Gonzalez FJ, Gelboin HV. Regio- and stereo-selective metabolism of phenanthrene by twelve cDNA-expressed human, rodent, and rabbit cytochromes P-450. Cancer Lett. 1994;83:305–313. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochalter JB, Zhong Y, Han S, Carmella SG, Hecht SS. Quantitation of a minor enantiomer of phenanthrene tetraol in human urine: correlations with levels of overall phenanthrene tetraol, benzo[a]pyrene tetraol, and 1-hydroxypyrene. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:262–268. doi: 10.1021/tx100391z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. IARC; Lyon, FR: 2004. Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking; pp. 174–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Zhong Y, Carmella SG, Hochalter JB, Rauch D, Oliver A, Jensen J, Hatsukami DK, Upadhyaya P, Hecht SS, Zimmerman CL. Phenanthrene metabolism in smokers: use of a two-step diagnostic plot approach to identify subjects with extensive metabolic activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;342:750–760. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.194118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong Y, Wang J, Carmella SG, Hochalter JB, Rauch D, Oliver A, Jensen J, Hatsukami D, Upadhyaya P, Zimmerman C, Hecht SS. Metabolism of [D10]phenanthrene to tetraols in smokers for potential lung cancer susceptibility assessment: Comparison of oral and inhalation routes of administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:353–361. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.181719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hecht SS, Hochalter JB, Carmella SG, Zhang Y, Rauch DM, Fujioka N, Jensen J, Hatsukami DK. Longitudinal study of [D10]phenanthrene metabolism by the diol epoxide pathway in smokers. Biomarkers. 2013;18:144–150. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2012.753553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hecht SS, Villalta PW, Hochalter JB. Analysis of phenanthrene diol epoxide mercapturic acid detoxification products in human urine: relevance to molecular epidemiology studies of glutathione-S-transferase polymorphisms. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:937–943. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yagi H, Jerina DM. A general synthetic method for non-K-region arene oxides. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:3185–3192. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frank O, Kreissl JK, Daschner A, Hofmann T. Accurate determination of reference materials and natural isolates by means of quantitative (1)h NMR spectroscopy. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:2506–2515. doi: 10.1021/jf405529b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manini P, Andreoli R, Poli D, De Palma G, Mutti A, Niessen WM. Liquid chromatography/electrospray tandem mass spectrometry characterization of styrene metabolism in man and in rat. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2002;16:2239–2248. doi: 10.1002/rcm.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fennell TR, Sumner SC, Snyder RW, Burgess J, Spicer R, Bridson WE, Friedman MA. Metabolism and hemoglobin adduct formation of acrylamide in humans. Toxicol Sci. 2005;85:447–459. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grill AE, Schmitt T, Gates LA, Lu D, Bandyopadhyay D, Yuan JM, Murphy SE, Peterson LA. Abundant rodent furan-derived urinary metabolites are associated with tobacco smoke exposure in humans. Chem Res Toxicol. 2015;28:1508–1516. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teichert J, Sohr R, Hennig L, Baumann F, Schoppmeyer K, Patzak U, Preiss R. Identification and quantitation of the N-acetyl-L-cysteine S-conjugates of bendamustine and its sulfoxides in human bile after administration of bendamustine hydrochloride. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:292–301. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.022855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Rooij JG, van Lieshout EM, Bodelier-Bade MM, Jongeneelen FJ. Effect of the reduction of skin contamination on the internal dose of creosote workers exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Scand J Work, Environ Health. 1993;19:200–207. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elovaara E, Heikkila P, Pyy L, Mutanen P, Riihimaki V. Significance of dermal and respiratory uptake in creosote workers: exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and urinary excretion of 1-hydroxypyrene. Occup Environ Med. 1995;52:196–203. doi: 10.1136/oem.52.3.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heikkila P, Luotamo M, Pyy L, Riihimaki V. Urinary 1-naphthol and 1-pyrenol as indicators of exposure to coal tar products. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1995;67:211–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00626355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sundberg K, Dreij K, Seidel A, Jernström B. Glutathione conjugation and DNA adduct formation of dibenzo[a,l]pyrene and benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxides in V79 cells stably expressing different human glutathione transferases. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:170–179. doi: 10.1021/tx015546t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dreij K, Sundberg K, Johansson AS, Nordling E, Seidel A, Persson B, Mannervik B, Jernstrom B. Catalytic activities of human alpha class glutathione transferases toward carcinogenic dibenzo[a,l]pyrene diol epoxides. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:825–831. doi: 10.1021/tx025519i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sundberg K, Dreij K, Berntsen S, Seidel A, Jernström B. Expression of human glutathione transferases in V79 cells and the effect on DNA adduct-formation of diol epoxides derived from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2001 Feb 28;133(1–3 Sp Iss):91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sundberg K, Johansson AS, Stenberg G, Widersten M, Seidel A, Mannervik B, Jernström B. Differences in the catalytic efficiencies of allelic variants of glutathione transferase P1-1 towards carcinogenic diol epoxides of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:433–436. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sundberg K, Widersten M, Seidel A, Mannervik B, Jernström B. Glutathione conjugation of bay- and fjord-region diol epoxides of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by glutathione transferase M1-1 and P1-1. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:1221–1227. doi: 10.1021/tx970099w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Upadhyaya P, Rao P, Hochalter JB, Li ZZ, Villalta PW, Hecht SS. Quantitation of N-acetyl-S-(9,10-dihydro-9-hydroxy-10-phenanthryl)-L-cysteine in human urine: comparison with glutathione-S-transferase genotypes in smokers. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:1234–1240. doi: 10.1021/tx060096w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathias PI, B’Hymer C. A survey of liquid chromatographic-mass spectrometric analysis of mercapturic acid biomarkers in occupational and environmental exposure monitoring. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2014;964:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2014.02.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel YM, Park SL, Carmella SG, Paiano V, Olvera N, Stram DO, Haiman CA, Le Marchand L, Hecht SS. Metabolites of the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon phenanthrene in the urine of cigarette smokers from five ethnic groups with differing risks for lung cancer. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]