LINC complexes connect the inner and outer nuclear membrane (ONM) to transduce nucleocytoskeletal force. Ding et al. identify an ONM protein, Kuduk/TMEM258, which modulates the quality of LINC complexes and regulates the nuclear envelope architecture, nuclear positioning, and the development of ovarian follicles.

Abstract

Linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton (LINC) complexes spanning the nuclear envelope (NE) contribute to nucleocytoskeletal force transduction. A few NE proteins have been found to regulate the LINC complex. In this study, we identify one, Kuduk (Kud), which can reside at the outer nuclear membrane and is required for the development of Drosophila melanogaster ovarian follicles and NE morphology of myonuclei. Kud associates with LINC complex components in an evolutionarily conserved manner. Loss of Kud increases the level but impairs functioning of the LINC complex. Overexpression of Kud suppresses NE targeting of cytoskeleton-free LINC complexes. Thus, Kud acts as a quality control mechanism for LINC-mediated nucleocytoskeletal connections. Genetic data indicate that Kud also functions independently of the LINC complex. Overexpression of the human orthologue TMEM258 in Drosophila proved functional conservation. These findings expand our understanding of the regulation of LINC complexes and NE architecture.

Introduction

The nuclear envelope (NE) consists of two lipid bilayer membranes that separate the nucleoplasm from the cytoplasm. The outer nuclear membrane (ONM) is continuous with the ER. The inner nuclear membrane (INM) has an underlying filamentous meshwork of lamin proteins called the nuclear lamina. The nuclear membranes and the lamina contain NE proteins that have important functions in regulating NE rigidity, gene expression, and chromosome organization. Dysfunctions in NE proteins impair NE architecture and cause human diseases such as rapid aging and cancers (Burke and Stewart, 2014).

The linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton (LINC) complexes, which are highly conserved throughout evolution, consist of Klarsicht (Klar)/ANC-1/SYNE homology (KASH) and Sad1/UNC-84 (SUN) domain proteins (hereafter referred to as KASH and SUN proteins; Chang et al., 2015). KASH proteins span the ONM by the KASH domain, which bears a carboxyl tail that binds to the SUN domain of INM-resident SUN proteins in the perinuclear space (PNS). This KASH–SUN interaction forms a stable structure bridging the ONM and INM (Sosa et al., 2012). Cytoplasmic extensions of KASH proteins bind to cytoskeletal filaments, and SUN proteins interact with INM proteins and with the nuclear lamina. Therefore, the LINC complex controls nucleocytoskeletal force transduction and thereby contributes to nuclear migration and cytoskeletal organization (Chang et al., 2015). Mutations of the genes encoding LINC complexes lead to nuclear dysmorphology and defective nuclear positioning in mouse skeletal muscle (Zhang et al., 2007; Lüke et al., 2008; Lei et al., 2009; Puckelwartz et al., 2009). Mutations of the human LINC complex genes cause human genetic disorders such as arthrogryposis, cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (Gros-Louis et al., 2007; Attali et al., 2009; Puckelwartz et al., 2009; Horn et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015). Aberrant expressions of KASH and SUN proteins are causative in lung and breast cancers (Lv et al., 2015; Matsumoto et al., 2015).

KASH and SUN proteins anchor at the NE through the “diffusion retention” model (Boni et al., 2015; Ungricht et al., 2015). SUN proteins retain KASH proteins through a physical interaction. Upon depletion of the Drosophila melanogaster SUN protein Klaroid (Koi), the two KASH proteins Klar and muscle-specific protein 300 (Msp300) are no longer localized at the NE (Kracklauer et al., 2007; Technau and Roth, 2008). Moreover, anchoring of SUN proteins at the INM can depend on the nuclear lamina proteins’ lamins and their associated proteins at the INM (Chang et al., 2015). In Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans carrying mutations of the lamin genes, SUN proteins are not localized at the NE (Lee et al., 2002; Kracklauer et al., 2007). It remains unknown whether proteins at the ONM regulate the LINC complex.

In this study, we identified the Drosophila protein Kuduk (Kud) at the ONM, where it associates with LINC components. Kud regulates NE architecture, nuclear positioning, and the development of ovarian follicles through LINC-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Overexpression of the human orthologue TMEM258 in Drosophila proved functional conservation. These findings improve our knowledge about the regulation of the LINC complex and the NE and might contribute to a better understanding of the pathology and treatment of the human diseases related to this complex and TMEM258.

Results

The conserved protein Kud is required for the survival and growth of ovarian follicle cells

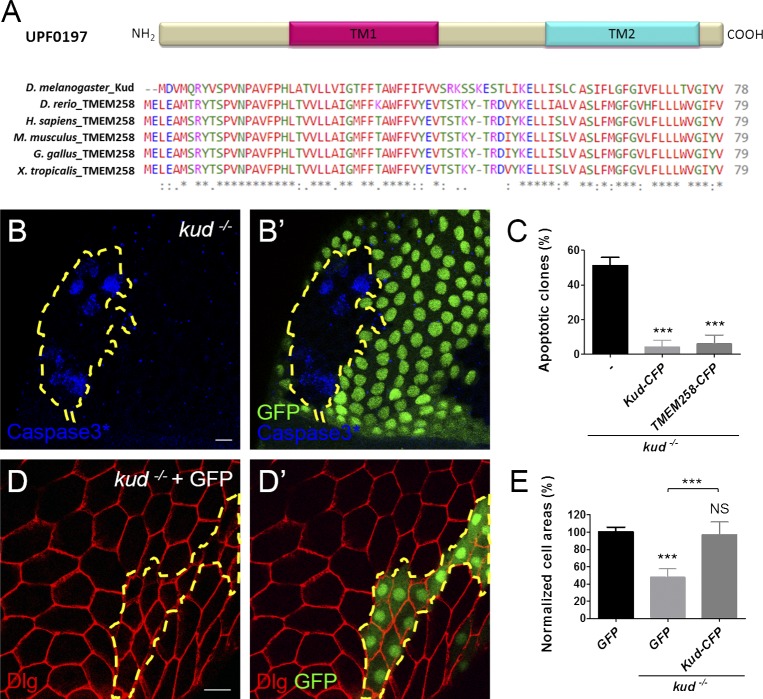

Proteins in the UPF0197 family are short proteins with 79 aa on average and are evolutionarily conserved in metazoans (Fig. 1 A). In this study, we studied the Drosophila member Kud encoded by the CG9669 gene. To determine its function, we generated gene knockout flies by homologous recombination (Fig. S1, A–C). The homozygous mutants displayed growth retardation (Fig. S1 D) and died as larvae, indicating that kud is a gene that is essential for development. We observed homozygous mutant cells in heterozygous flies by the Flippase (FLP)/FLP recombination target (FRT) technique (Xu and Rubin, 1993) and found defects in ovarian follicle cells, which enwrap the germ cell clusters in ovarioles. At 114 h after clone induction, apoptotic cells were present in more than half of the mutant clones, which were GFP negative, but not in the controls (Fig. 1, B and C). To distinguish the mutant clones more easily, we overexpressed GFP in the mutant clones using mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM; Lee and Luo, 1999). We found that loss of Kud reduced the cell size to 50% of the controls (Fig. 1, D and E). To examine whether the defects resulted from the loss of Kud, we overexpressed Kud C-terminally tagged with CFP (Kud-CFP) in the mutant cells. The production of Kud-CFP significantly rescued the phenotypes of kud mutant cells (Fig. 1, C and E). The human orthologous protein, transmembrane protein 258 (TMEM258), is 65% identical to Kud (Fig. 1 A). Overexpression of TMEM258 in kud mutant cells inhibited apoptosis (Fig. 1 C). These data indicate that kud expression is required for cellular growth and survival and that its human orthologue is conserved functionally.

Figure 1.

The evolutionarily conserved protein Kud is required for ovarian follicle development. (A) UPF0197 proteins have been conserved in evolution; TM1 and TM2 are putative TMs. The NCBI accession numbers of the UPD0197 proteins from top to bottom are Q9VVA8, Q6PBS6, P61165, P61166, Q76LT9, and Q6DDB3. Asterisks indicate conserved residues, colons indicate residues with strongly similar properties, and periods indicate residues with weakly similar properties. (B and B’) Apoptotic cells were marked with activated caspase 3 (Caspase3*), and the kud mutant cells lacking GFP expression are outlined by dashed lines. (C) Quantification of the clones containing apoptotic cells: n = 78, 153, and 78 from left to right. (D and D′) The boundaries of follicle cells were visualized by the plasma membrane protein Disc large (Dlg in red), and the kud mutant cells expressing GFP are outlined with dashed lines. Bars, 10 µm. (E) Quantification of normalized cell areas: n (number of clones) = 9, 13, and 15 from left to right. ***, P < 0.001. Error bars indicate means ± SD.

Conserved subcellular localizations at the NE and in the cytoplasm

Proteins in the UPF0197 family have two putative transmembrane domains (TMs; Fig. 1 A), suggestive of membrane localization. Indeed, cell fractionation analyses indicated that the overexpressed TMEM258-Myc was present in the membrane fraction but not in the soluble fraction of human 293T cells (Fig. 2 A), indicating that TMEM258 is membrane associated. Overexpressed TMEM258-Myc was found in the cytoplasm and at the NE, where it colocalized with the nuclear lamina marker, Lamin B1 (Fig. 2 B). Cytoplasmic but not NE localization of TMEM258 has been previously reported (Adachi et al., 2002). This disparity in protein distribution could be caused by differences in expression levels in cells or in the antibodies used.

Figure 2.

Conserved subcellular localizations at the NE and in the cytoplasm. (A) TMEM258 is membrane associated. Western blot (WB) of soluble (Sol) and membrane (Mem) fractions of TMEM258-Myc–expressing 293T cells probed with anti-GAPDH (cytoplasm), anti-Calnexin (ER and ONM), anti-Emerin (INM), and anti-Myc antibodies. (B–C′′) The overexpressed TMEM258-Myc in 293T cells (B) and the endogenous Kud in ovarian follicle cells (C) locate at the cytoplasm and colocalize with NE marker lamins (B′ and C′, arrows). Merges are shown in B′′ and C′′. Bars, 10 µm.

To visualize endogenous Kud in Drosophila, we raised a polyclonal antibody against its aa 1–18. We initially tested the antibody specificity by immunoblotting. Western blotting using larval lysates revealed that the antibody recognized a band ∼12 kD in the WT larva. The band was absent in kud homozygous mutants and was reduced in kud knockdown flies (Fig. S1 E). In addition, Western blotting using S2 cells overexpressing Kud-GFP revealed that the antibody recognized both the endogenous Kud and Kud-GFP (Fig. S1 F). When we used S2 cells overexpressing KudNGA-GFP, where the N terminus 18 aa was replaced with glycine and alanine, the antibody recognized only the endogenous Kud but not KudNGA-GFP (Fig. S1 F). These experiments showed that the antibody is specific for Kud. The antibody is also suitable for detecting native proteins because immunostaining revealed that Kud signals were highly reduced in kud mutant cells (Fig. S1 G). Kud in WT follicle cells were present in the cytoplasm and colocalized with LaminDm0 (LamDm0), the B-type lamin (Fig. 2 C). Double staining using the antibody and organelle markers revealed that the cytoplasmic Kud partially colocalized with the ER membrane protein Calnexin 99A (Cnx99A) but not markers of ER lumen, Golgi, or mitochondria (Fig. S2). These data indicate that the cytoplasmic Kud can localize at the ER membrane. Collectively, our data indicate that the subcellular localizations of Kud are conserved at the NE and in the cytoplasm.

Kud spans the ONM

To determine the topology of TMEM258 at the NE, we performed protease protection assays in 293T cell. However, proteinase K treatments did not alter the molecular weights of the bands recognized by antibodies of the N terminus and C terminus of TMEM258 (Fig. S3, A and B). This resistance to proteinase K digestion might result from the structure of TMEM258, which was not determined in this study. Thus, biochemical subcellular fractionation experiments might not be useful to determine the topology of TMEM258 at the NE.

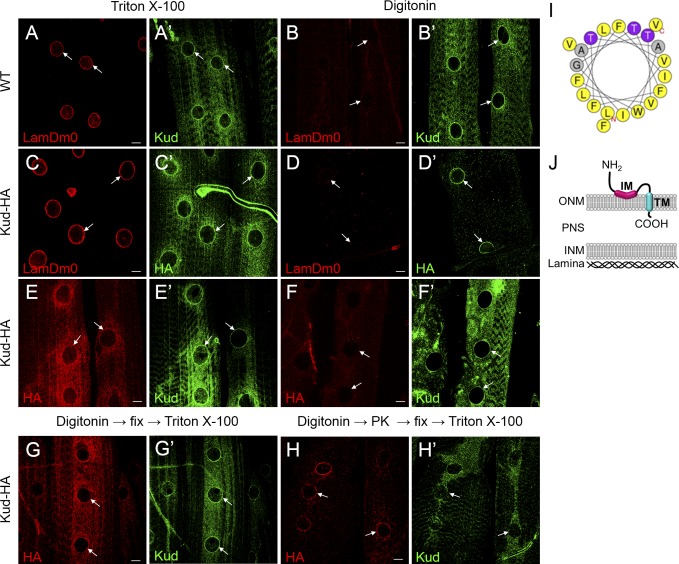

However, to determine the topology of Kud at the NE, we compared the signals of NE proteins in larval body muscles permeabilized using either Triton X-100 or digitonin. Digitonin permeabilizes membranes by binding to cholesterol, but the NE contains less cholesterol than the plasma membrane. Thus, low levels of digitonin can permeabilize only the plasma membrane but not the NE, and higher levels of digitonin can permeabilize the ONM or even both nuclear membranes. We found that in body muscles treated with digitonin, the permeability of nuclear membranes of individual nuclei were unequal, possibly because of the different depths of nuclei in the tissues. Therefore, we used LamDm0 as an indicator of a permeable INM. Upon treatment with Triton X-100, the N and C termini of Kud colocalized with LamDm0 in WT tissues and in muscle overexpressing C-terminally HA-tagged Kud (Kud-HA), respectively (Fig. 3, A and C). However, upon treatment with digitonin, both termini could be detected when the INM was intact, indicated by lack of immunoactivity of LamDm0 (Fig. 3, B and D), suggesting that they are not exposed to the nucleoplasm. Interestingly, we found some nuclei with the N terminus signal but without the C terminus HA signal after treatment with digitonin (Fig. 3, E and F). These data suggest that the two termini do not reside at the same side of a given membrane and that the N and C termini are exposed to the cytoplasm and to the PNS, respectively.

Figure 3.

Kud spans the ONM. (A–F′) Larval muscles of indicated genotypes were permeabilized with Triton X-100 or digitonin as indicated. The muscles were stained with antibodies against LamDm0 (A, B, C, and D), Kud (A′, B′, E′, and F′), or HA (C′, D′, E, and F). Bars, 10 µm. (G–H) Proteinase K protection assays of intact nuclei were performed. Kud-HA–expressing larval muscles were permeabilized with digitonin and were treated in the absence (G) or presence of proteinase K (PK; H). The tissues were then immunostained with anti-HA and anti-Kud antibodies in the presence of Triton X-100. The N terminus anti-Kud signals were highly reduced, whereas the HA signal of the C terminus remained (white arrows). Arrows indicate nuclei. (I) Helical projection of aa 19–39 of Kud. Color code for residues: gray, alanine and glycine; purple, threonine; yellow, hydrophobic. The polar residues defined by HeliQuest (http://heliquest.ipmc.cnrs.fr) include threonine and glycine. (J) A schematic diagram of the possible topology of Kud.

Next, we combined the digitonin permeabilization experiment with protease protection assay in larval muscles to examine the predicted topology. If the NE is intact when tissues are treated with digitonin, proteinase K should digest Kud’s cytoplasmic N terminus but not the PNS-localized C terminus. As expected, after proteinase K treatment in muscle overexpressing Kud-HA, signals of the N terminus were highly reduced, whereas the HA signal of the C terminus remained (Fig. 3, G and H). Furthermore, we analyzed the sequences of TMs using HeliQuest software (Gautier et al., 2008) and found that the hydrophobic and polar residues of predicted TM1 (aa 19–39) potentially segregate to two opposite faces (Fig. 3 I). This implies that the segment is amphipathic and does not cross the ONM. Thus, the segment is considered to be an intramembrane (IM) domain. Collectively, these data suggest that the N terminus of Kud is exposed to the cytoplasm, the IM resides at the cytoplasmic surface and orients in a parallel way to the ONM, the TM (aa 54–74) spans the ONM, and the C terminus resides in the PNS (Fig. 3 J).

Kud associates with LINC complex components in an evolutionarily conserved manner

In a two hybrid–based protein interaction mapping experiment, Kud was found to interact physically with the ONM protein Klar (Giot et al., 2003). Consistently, we found colocalization of Kud and Klar at the NE (Fig. 4 A). We then performed coimmunoprecipitation (coIP) experiments to examine the association of Kud and Klar. Kud and its orthologues are short; thus, they are unable to extend far from the ONM. We reasoned that if the interaction between Kud orthologues and KASH proteins had been conserved evolutionarily, the interacting parts of KASH proteins should be conserved and near to the NE. The best candidates are the conserved KASH domains, which consist of a TM spanning the ONM and a ∼30-aa C terminus in the PNS (Sosa et al., 2013). Indeed, we found that the KASH domains of Klar and of the other KASH protein, Msp300, respectively associated with Kud-His in S2 cells (Fig. 4 B). These results suggest that the KASH domain is sufficient for the interaction with Kud.

Figure 4.

Kud associates with LINC complex components in an evolutionarily conserved manner. (A) Kud colocalizes with Klar (A′ and A′′) at the NE (arrow) of larval muscles. Bar, 10 µm. (B–D) CoIP experiments were performed with the transfected S2 cell lysates (B) and with the transfected 293T cell lysates (C and D). (B) Kud was associated with the KASH domains of Msp300 and Klar, respectively. The interactions were specific because the coIP experiments did not detect the NPC protein Nup62 or the ER marker Cnx99A. (C) Nesprin 1 and Nesprin 2 associated with TMEM258, but deletion of the KASH domain abolished this interaction. (D) Association between TMEM258, SUN1, and the KASH domain. The association is specific because the coIP experiments did not detect the INM marker Emerin, the ER marker STIM1, or the chromatin-binding protein barrier to autointegration factor (BAF). IgG was used as negative control. Each coIP experiment was repeated three times. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot.

To examine whether the human orthologous protein TMEM258 would associate with human KASH proteins, we overexpressed proteins in 293T cells and found that the KASH proteins Nesprin 1 and Nesprin 2 both coimmunoprecipitated with TMEM258. The associations were lost after deletion of the KASH domain (Fig. 4 C). Moreover, the KASH domain alone also interacted with TMEM258 (Fig. 4 D), suggesting that the KASH domain is sufficient for this interaction. We also found an association between TMEM258 and the SUN protein SUN1 (Fig. 4 D), suggesting that TMEM258 associates with the LINC complex. These data indicate that Kud interacts with the LINC complex in an evolutionarily conserved manner.

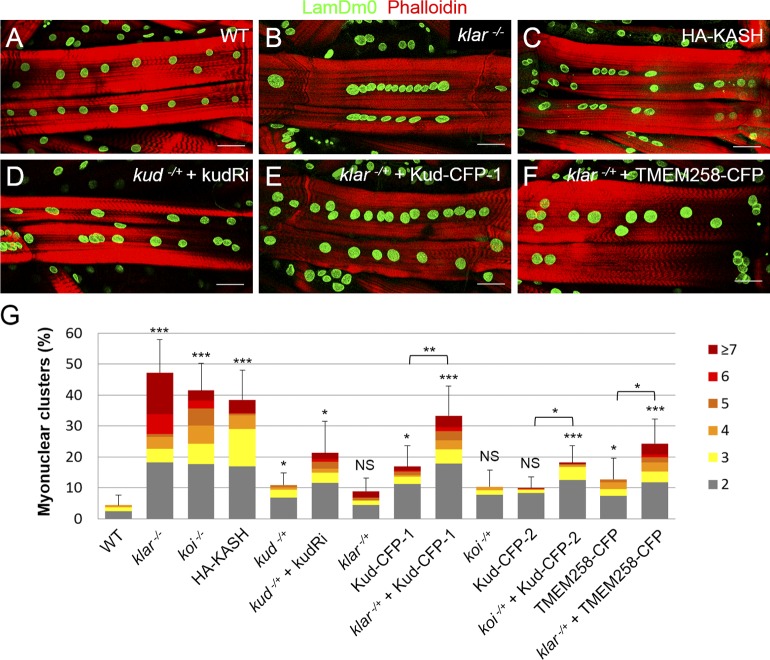

Kud regulates myonuclear positioning through the LINC complex

The association between Kud and the LINC complex prompted us to examine whether Kud is involved in muscle development, where Klar and Msp300 cooperatively regulate myonuclear positioning (Elhanany-Tamir et al., 2012). First, we used loss-of-function phenotypes of the LINC complex as positive controls. Complete loss of Klar or Koi caused severe nuclear clustering (Fig. 5, A, B, and G). Overexpression of the KASH domain, which lacks the cytoplasmic residues of the KASH proteins and is cytoskeleton free, caused dominant-negative effects (Starr and Han, 2002; Wilhelmsen et al., 2006; Starr, 2009). Consistent with the effect of the KASH domain, overexpression of the KASH domain of Klar caused significant defects in myonuclear spacing (Fig. 5, C and G). Next, we found that reduction of Kud, either from kud heterozygosity or RNAi expression in the heterozygote mutant, resulted in myonuclear clustering (Fig. 5, D and G), indicating that Kud is similar to the LINC complex in regulating myonuclear positioning.

Figure 5.

Kud regulates myonuclear positioning through the LINC complex. (A–F) Positions of myonuclei were marked with LamDm0, and muscle fibers were marked with phalloidin. Bars, 50 µm. (G) Quantification of nuclear clustering: n = 19, 17, 18, 20, 20, 31, 9, 26, 29, 18, 26, 29, 38, and 29 from left to right. Corresponding numbers of myonuclei in any cluster are indicated by different colors (right). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Error bars indicate means ± SD.

Overexpression of Kud in muscle caused minor or no defects in nuclear spacing, depending on the different transgenic lines (Fig. 5 G). However, the defects were enhanced synergistically by heterozygosity of klar and koi, respectively, although the heterozygosity alone caused no defect (Fig. 5, E and G). Overexpression of TMEM258 in the klar heterozygote caused similar effects, suggestive of functional conservation (Fig. 5, F and G). These data indicate that increases in Kud levels affect LINC-dependent nuclear positioning. Together with the physical interaction between Kud and the LINC complex, these genetic interactions strongly suggest that Kud regulates myonuclear positioning through the LINC complex.

Depletion of Kud increases LINC complex components to impair the cells

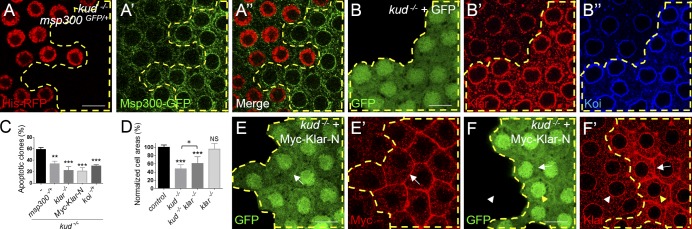

Because of the physical and genetic interactions between Kud and the LINC complex, we examined whether they would affect each other. We found that the LINC complex was not required to retain Kud at the NE because Kud was normally present at the NE in klar mutants and in koi mutants as in the control follicle cells and muscles (Fig. S4, A–F). Interestingly, we found that Kud affected the LINC complex. Msp300 was observed by using the Msp300-GFP-trap, in which the endogenous Msp300 is fused with GFP (Nagarkar-Jaiswal et al., 2015). GFP signals in kud mutant cells (62%, n = 112) were stronger than those in adjacent control cells (2%, n = 87; Fig. 6 A). Furthermore, 70% of kud mutant cells exhibited an increase in Klar (n = 101) when compared with the control cells (4%, n = 86; Fig. 6 B). Additionally, we observed the expression of Koi because it determines the NE localization of KASH proteins (Kracklauer et al., 2007; Technau and Roth, 2008). We found that Koi was also increased in the kud mutant cells (80%, n = 84) when compared with the control cells (5%, n = 62; Fig. 6 B). These data indicate that Kud depletion increases levels of LINC complex components.

Figure 6.

Depletion of Kud increases LINC complexes to impair the cells. (A and A′) kud mutant cells lacking the nuclear marker His-RFP (A) are outlined by dashed lines. The expression level of Msp300 was visualized by msp300–GFP-trap (A′). (A′′) Merged image. (B–B′′) The expression levels of Klar (B′) and Koi (B′′) were increased in kud mutant cells, which are outlined by dashed lines (GFP positive). (C) Quantification of the clones containing apoptotic cells: n = 53, 72, 86, 104, and 117 from left to right. (D) Quantification of normalized cell areas: n (number of clones) = 9, 13, 16, and 10 from left to right. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Error bars indicate means ± SD. (E–F′) The kud mutant cells coexpressing Myc-tagged Klar-N and GFP are outlined by dashed lines. The Klar antibody recognizes a C-terminal region of Klar that Klar-N lacks. The overexpressed Klar-N (E’) and endogenous Klar (F′) localized at plasma membrane are indicated (arrows). The NE distributions of endogenous Klar are indistinguishable in control (white arrowheads) and in kud mutant cells (yellow arrowheads; F and F′). Bars, 10 µm.

The increase in LINC complexes in the kud mutant cells raised the possibility that this might be a cause for the kud loss-of-function phenotypes. If so, reduction of LINC components in kud mutants should rescue the phenotypes. Confirming this, heterozygosity of msp300 reduced the apoptosis level (Fig. 6 C). In the double mutant clones of kud klar, in which Klar was removed completely from the kud mutant cells, apoptosis and cell size reductions were rescued significantly (Fig. 6, C and D). Interestingly, in the kud mutant clones, overexpression of the cytoplasmic domain of Klar (Klar-N; Fischer et al., 2004) significantly rescued apoptosis (Fig. 6 C). Because there was an accumulation of endogenous Klar at the plasma membrane where Klar-N was localized (Fig. 6, E and F) and mutant cells with an increase of Klar at the NE were reduced to 25.4% (n = 111), Klar-N seemed to rescue these abnormalities by trapping the endogenous Klar and thereby reducing its NE targeting. Furthermore, removing one copy of koi—thus theoretically halving the KASH protein content at the NE—was sufficient to rescue apoptosis in the kud mutant follicle cells (Fig. 6 C), suggesting that the increased LINC complex components at the NE were responsible for the phenotype.

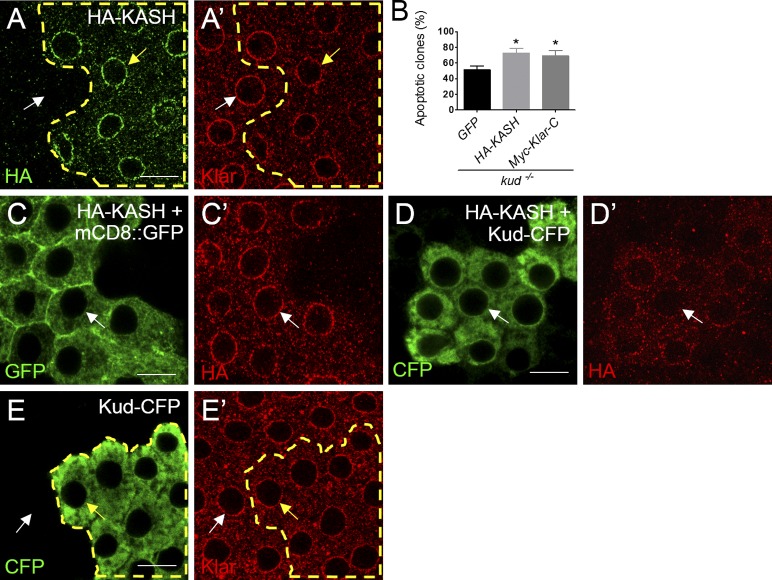

Kud might suppress anchorage of the cytoskeleton-free KASH isoforms at the NE to maintain LINC functions

We wondered how LINC complexes could increase but become harmful for kud mutant cells because overexpression of Klar or Koi in the WT did not result in any defects as seen in the kud mutant follicles (not depicted). Endogenous KASH proteins exhibit various isoforms including those bearing the KASH domain but lacking the cytoskeleton-binding domain (Rajgor and Shanahan, 2013). Theoretically, these cytoskeleton-free KASH isoforms can compete with the KASH-binding sites at the NE to disrupt the LINC complex and thereby reduce nucleocytoskeletal connections. Consistently, in C. elegans and mice, overexpression of the KASH domain causes dominant-negative effects because it disrupts LINC complexes and displaces the endogenous KASH proteins from the NE (Starr and Han, 2002; Wilhelmsen et al., 2006; Starr, 2009). Similarly, we found that overexpression of the KASH domain disrupted myonuclear spacing (Fig. 5 G). Furthermore, we generated clones overexpressing KASH domains in WT follicle cells using a flip-out system (Struhl and Basler, 1993). This overexpression also displaced the endogenous Klar in 38% of follicle cells (n = 105; Fig. 7 A), although such overexpression did not cause any obvious defects (not depicted). This confirmed that increases in cytoskeleton-free KASH isoforms impair LINC function. We found that overexpression of the KASH domain of Klar significantly enhanced apoptosis in the kud mutant cells (Fig. 7 B). A previously described construct of this KASH domain (Klar-C; Guo et al., 2005) showed similar results (Fig. 7 B). These data indicate that defective LINC function leads to apoptosis upon loss of Kud, and that Kud prevents the apoptotic effect of the dominant-negative KASH domain. These results prompted us to examine whether Kud would affect the anchorage of the KASH domain at the NE. When clonally overexpressed in follicles, the KASH domain of Klar was localized at the NE of 82% of the cells (n = 233; Fig. 7 C). Interestingly, overexpression of Kud significantly reduced the NE distribution of the KASH domain: only 8% of the cells (n = 336) retained the NE localization (Fig. 7 D). This treatment did not affect anchorage of endogenous Klar at the NE (Fig. 7 E). These data indicate that Kud can suppress the anchorage of the cytoskeleton-free KASH domain at the NE to maintain LINC functions.

Figure 7.

Kud suppresses the anchorage of cytoskeleton-free KASH proteins at the NE. (A and A′) HA-KASH–expressing cells are outlined by dashed lines. The NE distribution of Klar was lower in these cells (yellow arrows) than that in control cells (white arrows). (B) Quantification of the clones containing apoptotic cells: n = 78, 43, and 84 from left to right. *, P < 0.05. Error bars indicate means ± SD. (C–D′) HA-KASH was coexpressed with mCD8::GFP (C) and Kud-CFP (D), respectively. The KASH domain was found at the NE in control cells (C′) but was dispersed from the NE in Kud-CFP–overexpressing cells (D′). Arrows indicate the NE. (E and E′) The NE distribution of Klar (E′) is indistinguishable in Kud-CFP–overexpressing cells (outlined by dashed lines; yellow arrows) and in adjacent control cells (white arrows). Bars, 10 µm.

Kud might down-regulate the level of LINC complex components through autophagy

How does Kud regulate the level of LINC complex? Because the B-type lamin LamDm0 determines the NE targeting of the LINC complex (Kracklauer et al., 2007), we tested whether the level of LamDm0 would be affected by depletion of Kud. However, the level of LamDm0 in kud mutant cells was similar to the control (Fig. S4 G), indicating that Kud does not affect the LINC complex via LamDm0. The protein but not the mRNA level of Klar was significantly increased in kud mutant larvae (Fig. 8, A and B), indicating that Kud negatively regulates the level of KASH proteins and that this regulation occurs in tissues other than follicles. We further examined whether LINC complexes would be regulated by autophagy or proteasome-mediated degradation. Proteasomes mediate the degradation of SUN proteins (Chen et al., 2012). However, blocking such proteasome degradation by knockdown of Rpn6, a subunit of 26S proteasome, did not increase the level of LINC complex components (cells with increased Klar: 2.9%, n = 104; increased Koi: 1%, n = 104). These data suggest that proteasome-dependent degradation might not participate. In contrast, we found that autophagy is involved. Activation of autophagy by overexpression of Atg1 reduced the level of Klar in 63% of cells (n = 104; Fig. 8 C), indicating that Klar can be degraded via autophagy. This treatment also reduced the level of Koi in 9% of cells (n = 122; Fig. 8 D), suggesting that autophagy might also play a role for degrading SUN proteins. In addition, autophagy is activated in late-stage follicle cells (Barth et al., 2011), which could be observed using LysoTracker, a lysosome and autolysosome marker. Interestingly, LysoTracker signals were highly reduced in kud mutant follicle cells (Fig. 8, E and F), and the level of the autophagosome marker Atg8a was increased in kud mutant larvae (Fig. 8 G). These data suggest that loss of Kud might block the autophagic flux. Altogether, our data suggest that Kud might down-regulate LINC complex components through positively regulating autophagy.

Figure 8.

Kud might down-regulate the level of LINC complex components. (A, B, and G) RT-PCR (A) and Western blotting (WB; B and G) were performed with larval muscle or whole larval lysates. Numbers shown are means ± SD. The normalized mRNA level of klar in third and second instar larvae of WT and in kud mutants was equivalent (A). The normalized protein levels of Klar in WT, kud, and transheterozygote mutants over the deficient condition are shown in B. IP, immunoprecipitation. (C–D′) Atg1 and GFP were coexpressed in follicles (outlined by dashed lines; C and D). In control cells (white arrows), Klar (C′) and Koi (D′) were present at the NE, and the expression was reduced by Atg1 overexpression (yellow arrows). (E and E′) The kud mutant cells (GFP positive) are outlined with dashed lines. The lysosomes and autolysosomes in cytoplasm were marked using LysoTracker (Ltr). (F) Quantification of LysoTracker-positive dots per cell. n = 29 and 41. Error bars indicate means ± SD. (G) The normalized protein levels of Atg8a are shown. Bars, 10 µm. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

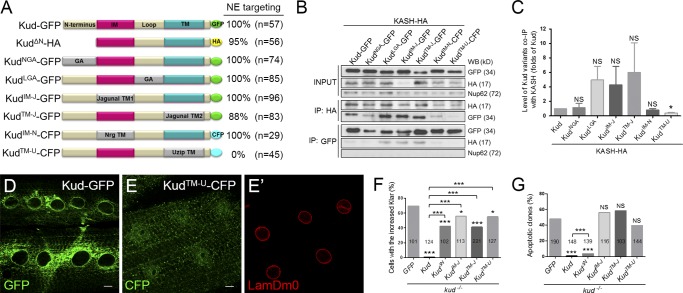

Domain studies for Kud–KASH association and the function of Kud

To ascertain which part of Kud is important for associating with KASH proteins, we generated Kud variants with alterations in each domain (Fig. 9 A). CoIP analyses were performed by coexpressing the Kud variants and the KASH domain of Klar in S2 cells. Substitutions of the N terminus and the loop region with peptides containing glycine or alanine (KudNGA or KudLGA) did not affect the Kud–KASH association (Fig. 9, B and C). Furthermore, to evaluate the importance of Kud IM and TM domains, we replaced the domains with TMs of the ER protein jagunal to generate KudIM-J and KudTM-J as well as TMs of the plasma membrane proteins Neuroglian (Nrg) and Unzipped (Uzip) to generate KudIM-N and KudTM-U. Only KudTM-U exhibited reduced Kud–KASH association, but other TM substitution variants retained a similar strength of association compared with the WT form (Fig. 9, B and C). Interestingly, the strength of the association seemed to correlate with NE targeting, because except for KudTM-U, all Kud variants could target to the NE in muscles (Fig. 9, A, D, and E). Because KudTM-J can localize at the NE, we reason that the reduction in NE targeting of KudTM-U might result from replacement of the TM rather than from its loss and that the TM of Uzip in KudTM-U might promote localization in downstream compartments in the secretory pathway. Together with our findings that the depletion of klar or koi did not affect the NE targeting of Kud (Fig. S4, A–F), these data suggest that NE targeting of Kud is required for Kud–KASH association. In addition, each domain could not work singly but via a compensatory relationship to contribute to NE targeting and the association, because altering single domains did not affect NE targeting of Kud and the Kud–KASH association.

Figure 9.

Domain studies for the Kud–KASH association and the function of Kud. (A) Schematic diagram showing Kud variants. GA, glycine and alanine; NrgTM, the TM domain of Nrg; UzipTM, the TM domain of Uzip. (B and C) CoIP of Klar’s KASH domain and Kud variants expressed in S2 cells. The interactions were specific because the coIP did not detect the NPC protein Nup62 (B). The efficiency with which Kud variants were coimmunoprecipitated with the KASH domain was quantified by three independent experiments (C). Data shown are means ± SEM. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot. (D–E′) Subcellular localization of Kud and KudTM-U. Ring-shaped structures, suggestive of the NE, appeared in larval muscle expressing Kud (D) but not in KudTM-U-expressing muscle (E). LamDm0 marked the NE (E′). Bars, 10 µm. (F) Percentages of cells with the increased Klar. (G) Percentages of clones containing apoptotic cells. The numbers in the bars are cells (F) and clones (G) scored. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

To examine the importance of domains for the functions of Kud, we overexpressed Kud variants in kud mutant follicle cells. We found that overexpression of KudTM-U could not rescue the level of Klar as Kud did and could not suppress the apoptosis of mutant cells (Fig. 9, F and G). To avoid the problem of losing NE localization of KudTM-U, we used KudΔN, KudIM-J, and KudTM-J, which can localize at the NE. The variants partially rescued the level of Klar but did not achieve the rescue efficiency of Kud (Fig. 9, F and G). These data suggest that each domain of Kud participates in regulating the level of Klar. Furthermore, Kud and KudΔN, but not KudIM-J or KudTM-J, significantly suppressed the apoptosis (Fig. 9, F and G), suggesting that IM and TM domains of Kud are critical for Kud functions. Because KudIM-J and KudTM-J can associate with the KASH protein, these data suggest that in addition to the association with KASH protein, other mechanisms dependent on IM and TM domains are required for functions of Kud.

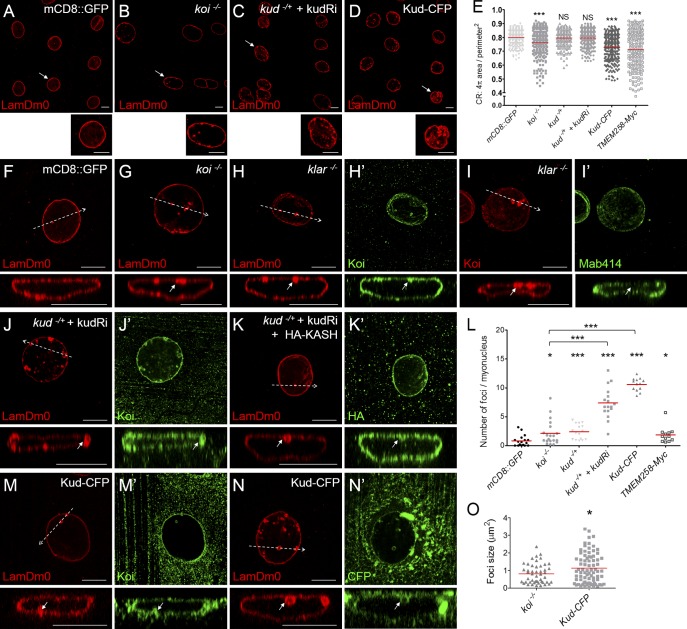

Kud regulates myonuclear morphology and has LINC-independent functions

Knockdown of genes encoding Nesprins alters nuclear shape (Zhang et al., 2007; Lüke et al., 2008). We examined whether Kud and the LINC complex would affect myonuclear morphology in Drosophila. Myonuclei of larval body walls were marked using LamDm0. Nuclear roundness was determined by calculating the nuclear contour ratio (CR), which for a circle is 1, and this number decreases in misshapen nuclei (Goldman et al., 2004). Complete loss of Koi or Klar altered nuclear roundness (Fig. 10, A, B, and E) and caused ectopic nuclear LamDm0 foci (Fig. 10, F–H and L). The LamDm0 foci were attached to the NE and were positive for the INM marker but negative for the nuclear pore complex (NPC) marker Mab414 (Fig. 10, H and I). These observations suggest that the foci are of type I nucleoplasmic reticulum (NR), where the INM but not the ONM invaginates into the nucleoplasm, identical to those found upon knockdown of Nesprin-encoding genes (Zhang et al., 2007). These data confirm that the LINC complex affects myonuclear morphology in Drosophila.

Figure 10.

Kud regulates myonuclear morphology. (A–D, F–K′, and M–N′) Nuclei were marked with LamDm0. (A–D) The indicated myonuclei are magnified below each image. (E) Quantification of the nuclear roundness, represented by the CR (see the Quantification section in Materials and methods). n > 200 nuclei for each genotype. (F–K′ and M–N′) Confocal microscopy cross sections of the regions indicated by dashed arrows are shown below each image. The bubble-shaped nuclear foci were attached to the NE (arrows). (H–I′) In klar mutant myonuclei, the INM marker Koi (H′) but not the NPC proteins (I′) were found at LamDm0 foci. (J–K′) In Kud-depleted myonuclei, Koi (J′) and the ONM marker KASH domain (K′) were found at the LamDm0 foci. (L) Quantification of nuclear foci. (M–N′) In Kud-overexpressing myonuclei, Koi (M′) and the ONM marker Kud-CFP (N′) were found at the LamDm0 foci. Bars, 10 µm. (O) Quantification of nuclear foci size. Red lines in the scatter dot plots show the mean values. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

As Kud regulates LINC complexes, its dysfunctions might phenocopy the mutants of the LINC components in myonuclear morphology. In support of this, misshapen nuclei were observed upon reduction and overexpression of Kud, although only the latter case caused significant reduction in the CR (Fig. 10, C–E). These alterations in Kud levels also produced ectopic LamDm0 foci (Fig. 10, J–N). Overexpression of the human Kud orthologous protein TMEM258 resulted in misshapen nuclei and ectopic LamDm0 foci, confirming functional conservation of these proteins (Fig. 10, E and L). These data suggest that both Kud and the LINC complex are required for maintaining myonuclear morphology in Drosophila. Based on the physical and genetic interactions found in our study, Kud might regulate myonuclear morphology through a LINC-dependent mechanism. However, upon reduction or overexpression of Kud, the LamDm0 foci were positive for INM and ONM markers (Fig. 10, J, K, M, and N). These data indicate that the foci are invaginations of both nuclear membranes, a characteristic of the type II NR, and thus distinct from those seen in mutant forms of the LINC complex. Additionally, the number of LamDm0 foci upon reduction or overexpression of Kud was more than that in koi mutants (Fig. 10 L), and the foci in Kud-overexpressing cells were larger than those in koi mutants (Fig. 10 O). These differences imply that Kud might act through a LINC-independent mechanism. Consistent with this, homozygosity for the kud but not koi mutation impairs follicle development and causes death. Collectively, these data demonstrate that Kud modulates NE architecture and also functions in a LINC-independent manner.

Discussion

Kud is a newly identified regulator for the LINC complex and NE architecture

In J.R.R. Tolkien’s novel, The Lord of the Rings, the Hobbits, who call themselves “Kuduk,” are short and protect the One Ring of Power. Thus, we named the protein Kud because of its short length and importance for the ring-shaped NE. To our knowledge, Kud is a newly described ONM protein and the first LINC regulator found at the ONM. Our data support the idea that Kud modulates NE architecture via LINC-dependent and -independent mechanisms. The findings add to our understanding of regulation in the LINC complex and the NE architecture.

Kud-mediated quality control of the LINC complex

Our data suggest that Kud is a KASH-interacting protein regulating the LINC complex. As to the lack of evidence of direct interactions between Kud and KASH proteins, we do not exclude the possibility that the interaction is indirect. In addition, the association between TMEM258 and SUN1 suggests that Kud might interact with the KASH proteins of LINC complexes. As KASH proteins can interconnect via the cytoplasmic domains (Lu et al., 2012; Taranum et al., 2012), Kud might interact with the KASH proteins of LINC complexes through associating with other KASH proteins that do not participate in LINC complexes. Further studies should examine how Kud interacts with KASH proteins. Based on our finding, we speculate that Kud might regulate the LINC complex in several ways. First, partners of KASH proteins have been suggested to keep the three KASH proteins interacting with a SUN trimer apart (Sosa et al., 2012). Such Kud–KASH association might allow Kud to regulate the organization of KASH proteins. Second, because of the alternative initiation of transcription and splicing, mammalian Nesprins have KASH isoforms, which contain the KASH domain, without or with cytoskeleton-interacting domains of different lengths (Rajgor and Shanahan, 2013). Switching KASH isoforms might alter cytoskeletal connections of the LINC complex to regulate muscle development and embryonic stem cell differentiation (Randles et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2011). Our data support the idea that Kud suppresses the NE anchorage of cytoskeleton-free KASH proteins to ensure that the LINC complexes are linked to the cytoskeleton. Therefore, Kud might act as a quality control for the cytoskeletal connections of LINC complexes. Third, LINC complexes can align linearly along dorsal actin cables to form higher-ordered assemblies, the transmembrane actin-associated nuclear (TAN) lines. Formation of the TAN lines depends on the cytoskeletal connections of KASH proteins (Luxton et al., 2010). Thus, Kud might also benefit the formation of the higher-ordered LINC assemblies. Collectively, it appears that Kud regulates the quality of the LINC complex, thus modulating nucleocytoskeletal connections during development.

Kud might promote autophagic degradation of the LINC complex

Components of the NE can be degraded by nuclear autophagy, which is evolutionarily conserved (Luo et al., 2016). However, the substrates and regulatory mechanisms are largely unknown. Our data support the idea that LINC complexes might be substrates of nuclear autophagy and that Kud could suppress the level of KASH proteins by positively regulating autophagy. We speculate that the cytoskeleton-free KASH proteins are prone to be excluded from the TAN line and that the association with Kud might allow Kud-mediated autophagy to eliminate cytoskeleton-free KASH proteins selectively. Besides this, our data indicate that Kud-mediated autophagy might play a minor role for regulating the level of Koi. Further studies should identify which mechanisms downstream of Kud are responsible for regulating the level of Koi.

Kud might regulate nuclear morphology and autophagy to affect global cellular functions

Given that Kud regulates NE architecture and the LINC complex and that NE targeting is required for the Kud–KASH association, we suggest that NE-localized Kud plays a crucial role. It is still worthy to examine the subcellular localization and functions of cytoplasmic Kud. Besides, our data suggest that in addition to the Kud–KASH association, Kud might participate in other mechanisms dependent on IM and TM domains. TMs can dimerize through the (small)xxx(small) motif, in which “small” means small amino acids such as glycine and serine (Russ and Engelman, 2000; Schneider and Engelman, 2004). Interestingly, the TM of Kud has a conserved tandem repeat of the dimerization motif SLCASIFLG (Fig. 1 A). This observation along with the dimerization of bacterially expressed Kud (Fig. S3 C) suggest a homophilic interaction. Oligomerization of membrane proteins and insertion of wedgelike amphipathic helices can regulate membrane curvature (McMahon and Gallop, 2005; Drin and Antonny, 2010). It would be interesting to examine whether the homophilic interaction of Kud and the presumptively amphipathic IM might play a role in regulating nuclear morphology. Finally, nuclear morphology can control gene expression and DNA repair (Walters et al., 2012), and nuclear autophagy can degrade NE, NE proteins, and chromatin (Luo et al., 2016). Therefore, we reason that Kud controls the homeostasis of the LINC complex and global factors through regulation of nuclear morphology and autophagy, thus including LINC-independent cellular functions.

TMEM258 is associated with human diseases

We show in this study that Kud is required for the development of Drosophila ovarian follicles and muscles. However, depletion of Kud did not impair the nuclear migration of photoreceptors (Fig. S5), which depends on klar and msp300 (Mosley-Bishop et al., 1999; Patterson et al., 2004; Technau and Roth, 2008). These data indicate that Kud functions in a tissue-specific manner, as with the LINC complex and other NE proteins (Worman and Schirmer, 2015). Our data show that the human orthologous protein TMEM258 exhibits conserved functions, suggesting that dysregulation of this protein might affect LINC functions and the NE to cause defects in specific tissues. In addition, we have demonstrated that overexpression of Kud and TMEM258 can result in cellular defects, suggesting that an increase in TMEM258 might cause diseases. Interestingly, in the dominantly inherited disorder spinocerebellar ataxia type 20, the chromosomal region containing TMEM258 is duplicated, and the expression level of this gene is increased (Knight et al., 2008). In addition, misshapen nuclei and NR are characteristics of cancer cells (Malhas and Vaux, 2014). The large noncoding RNA ANRIL (antisense noncoding RNA in the INK4 locus), which is associated with cancers and metastasis, positively regulates the expression of TMEM258 (Bochenek et al., 2013; Qiu et al., 2015). Graham et al. (2016) recently reported that increased TMEM258 expression is associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Further studies should examine whether the pathology of TMEM258-associated diseases involves alterations of the LINC complex and NE architecture.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks and incubation

The stocks we used were as follows: klarΔ1–18 (Elhanany-Tamir et al., 2012), msp300compl (Technau and Roth, 2008), koiHRKO80.w (Kracklauer et al., 2007), 24B-GAL4 (Brand and Perrimon, 1993), UAS-Atg1 (Chen et al., 2008), UAS-6×myc–Klar-N (Fischer et al., 2004), UAS-6×myc–Klar-C (Fischer et al., 2004), UAS-mCD8-GFP (Gao et al., 1999), and UAS-Atg1 (Chen et al., 2008). The stock w1118 was used as a WT control. The following stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center: Mef2-GAL4 (BL50742), 6934-Hid (BL6934), GAL4477[w–]; TM2/TM6 (BL26258), Df(3L)Exel9002 (BL7935), Msp300GFP (BL59757), and sqh-EYFP-Mito (BL7194). UAS-Rpn6 Ri (VDRC18021) was obtained from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center. The following stocks were used to generate flies bearing mutant or overexpression clones: hs-FLP (BL26902), ubi-GFP.nls FRT2A (BL5825), tub-GAL80 FRT2A (BL5190), act-GAL4, UAS-GFP, Act>CD2>Gal4 (BL4779), and Act>CD2>Gal4; UAS-GFP (BL39760). The transgenic flies we generated were: UAS-Kud-CFP, UAS-Kud-GFP, UAS-Kud-HA, UAS-KudΔN-HA, UAS-KudNGA-GFP, UAS-KudLGA-GFP, UAS-KudIM-J-GFP, UAS-KudTM-J-GFP, UAS-KudIM-N-CFP, UAS-KudTM-U-CFP, UAS-kud Ri, UAS-TMEM258-CFP, and UAS-HA-KASH. All flies were incubated at 25°C for observing follicle cells and at 29°C for higher-level expressions of transgenes in larval muscles.

Generation of mutant and overexpression clones in ovarian follicle cells

Female adults were heat shocked at 37°C for 1 h and then were mated and cultured in vials containing fresh yeast-supplemented food. Ovaries were dissected at 96–114 h after clone inductions for immunostaining. Female genotypes and the abbreviations for generating mutant clones are listed as follows: (a) kud–/– (using FRT/FLP technique): hs-FLP/+; kud FRT2A/ubi-GFP.nls FRT2A; (b) kud–/– (using the mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker technique): hs-FLP/+; act>GFP/+; kud FRT2A/tub-GAL80 FRT2A; (c) kud–/– klar–/–: hs-FLP/+; klar kud FRT2A/ubi-GFP.nls FRT2A; (d) kud–/– msp300–/+: hs-FLP/+; msp300/+; kud FRT2A/ubi-GFP.nls FRT2A; (e) kud–/– koi–/+: hs-FLP/+; koi/+; kud FRT2A/ubi-GFP.nls FRT2A; (f) kud–/– msp300GFP/+: hs-FLP/+; msp300GFP/+; kud FRT2A/ubi-GFP.nls FRT2A; (g) kud–/– + HA-KASH: hs-FLP/+; act> HA-KASH /+; kud FRT2A/tub-GAL80 FRT2A; and (h) kud–/– + Myc-Klar-N (or Myc-Klar-C): hs-FLP/+; act> Myc-Klar-N (or Myc-Klar-C)/+; kud FRT2A/tub-GAL80 FRT2A. Female genotypes for generating overexpression clones are listed as follows: (a) Act>CD2>Gal4−/+; hs-FLP/UAS-X (and UAS-Y); The X and Y mean one of the overexpressed proteins: HA-KASH, Kud-CFP, or mCD8GFP; and (b) Atg1 + GFP: Act>CD2>Gal4; UAS-GFP/UAS-Atg1; hs-FLP/+.

Preparation of ovarian follicles and larval muscles and immunostaining

Adult female flies were put on ice for 10 min. Ovaries were dissected and teased apart from the abdomen in PBS on Sylgard plates and then shaken in a fixation solution (volume ratio of 4% formaldehyde and 1% NP-40 in PBS: heptane = 1:3) for 20 min. The egg chambers were dispersed by pipetting the ovaries vigorously. Stage 10–12 egg chambers were collected and washed in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBST). Stage 12 egg chambers were used for observing apoptosis, cell areas, and the subcellular localization of Kud and LysoTracker. Stage 10 egg chambers were used for observing other proteins.

Third instar larvae were put on ice for 10 min and pinned on Sylgard plates. Larvae were slit open, cleaned of fat bodies and organs, and fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min, and then they were washed with PBST and blocked in 5% normal donkey serum in PBST for immunostaining. For digitonin experiments, the larval muscles were treated with 20 µg/ml digitonin on ice for 5 min for permeabilization, and PBS was substituted for PBST for subsequent immunostaining procedures. For protease protection assays, the digitonin-permeabilized larval muscles were washed with PBS and then treated with or without 50 µg/ml proteinase K on ice for 5 min. The muscles were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 20 min and then were blocked in 5% normal donkey serum in PBST for immunostaining.

The first antibodies used in immunostaining included mouse anti-Dlg (4F3; 1:50), mouse anti-GFP (GFP-G1; 1:100), mouse anti-LamDm0 (ADL84.12; 1:100), mouse anti–Klar-C (9C10; 1:30), mouse anti-Cnx99A (6-2-1; 1:100), and rat anti-Elav (7E8A10; 1:200) were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank. The antibody for Drosophila Kud was generated in rabbits against the peptide sequence of aa 1–18 (1:600; MDVMQRYVSPVNPAVFPH; LTK BioLaboratories). The antibody for Drosophila Koi was generated in rabbits against the peptide sequence of amino acids 79–96 (1:2,000; DYSSDDMTPDAKRKQNSI; LTK BioLaboratories). The other commercial antibodies used were rabbit anti-GFP–conjugated Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific), rabbit anti–activated caspase 3 (1:250; Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-Myc (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-HA (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti–NPC proteins (Mab414; 1:200; Abcam), mouse anti-KDEL (10C3; 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti–Golgi p120 (7H6D7C2; 1:100; EMD Millipore), rabbit anti-HA (1:400; Cell Signaling Technology), goat anti–human lamin B1 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and rhodamine-phalloidin (1:200; Invitrogen). Secondary antibodies including goat anti–mouse Alexa Fluor 488, anti–rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, and donkey anti–goat Alexa Fluor 546 were obtained from Invitrogen. Goat anti–mouse Cy3, anti–rabbit Cy3, and anti–rabbit Cy5 were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.

For labeling with LysoTracker DND-99 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), ovaries were dissected in Schneider’s Drosophila Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific), washed briefly, and incubated for 5 min in 25 µM LysoTracker. Then, they were washed three times in PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, washed three times in PBST, and then mounted and imaged immediately.

Confocal microscopy

After immunostaining, muscles and egg chambers were mounted in PBST for imaging using Plan-Apochromat 20× 0.6 NA or 63× 1.4 NA oil immersion objectives and 100× 1.4 NA oil immersion lenses with a confocal microscope (LSM 510; ZEISS). The fluorescence images were processed using Photoshop CS5 (Adobe).

Cell culture, fractionation, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting

Drosophila S2 cells were cultured as described in the Drosophila Expression System (Invitrogen) and were transfected using commercial Calcium Phosphate Transfection kits (Invitrogen) or TransIT-Insect Transfection Reagent (Mirus). Human 293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and transfected as described in the procedure manual for the TurboFect Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For subcellular fractionation, 293T cells were processed following the manufacturer’s instructions of the Cell Membrane Protein Extraction kit (Biokit Biotechnology).

For immunoprecipitation, lysates of equal numbers of cells were incubated with protein A beads (Protein A Sepharose CL-4B; GE Healthcare) coupled, respectively, with mouse antipolyhistidine (His; 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-HA (1:40; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-Myc (1:40; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-GFP[9F9.F9] (1:120; Abcam), mouse IgG (1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-FLAG (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich), and rabbit IgG (1:250; Abcam) antibodies overnight at 4°C. After incubation, beads were washed once with a low-stringency wash buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% NP-40) and twice with a high-stringency buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, and 0.1% NP-40), and then they were boiled with 1× SDS loading buffer to elute the proteins. Proteins were resolved by 8% or 12% SDS–PAGE and subjected to standard Western blotting techniques.

The primary and secondary antibodies for Western blotting were rabbit anti-Kud (1:1,000), mouse anti-HA (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-His (1:2,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-Myc (1:300; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti-Nup62 [Mab414] (1:500; Abcam), mouse anti-Cnx99A (6-2-1; 1:500; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), mouse anti-GAPDH (1:5,000; Novus Biologicals), mouse anti-Emerin[8A1] (1:600; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), rabbit anti-Calnexin (1:600; Novus Biologicals), mouse anti–Klar-C (9C10; 1:30, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), rabbit anti-HA (1:1,500; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-Atg8a (1:2,500; provided by G.-C. Chen, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan), rabbit anti-FLAG (1:2,000; Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-GFP (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), goat anti-TMEM258 (1:300; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), goat anti–mouse HRP (1:5,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.), goat anti–rabbit HRP (1:5,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.), and donkey anti–goat HRP (1:5,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was purified from WT and kud mutant larvae with TRIzol and then the RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA with SuperScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Invitrogen). 300 ng cDNA was amplified by primers specific for Klar and GAPDH with Tag polymerase (Promega). The mRNA level of Klar was normalized to the level of GAPDH.

Quantification

The normalized cell area of follicles was calculated from the areas of five mutant cells based on that of control cells in one egg chamber. Images of myonuclear foci (>5 µm2) were acquired from larval muscles 6 and 7 of abdominal segments 2 and 3. The numbers of foci per myonucleus were the means of the total numbers of myonuclear foci in one segment. For CR calculations, the area and perimeter of each nucleus were measured using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). The CR was calculated for each nucleus using the formula 4π area/perimeter2. For foci size calculations, the area of each was measured. Myonuclear positions were observed in larval muscles 6 and 7 of abdominal segments 5 and 6. In quantification of myonuclei clusters, a group of myonuclei was defined as having a distance between any two of less than half of their diameter. Statistical significance was calculated from the percentages of clusters containing more than two myonuclei. RT-PCR and Western blotting results were quantified using ImageJ, and the intensity was normalized to WT. Statistical analysis was performed with Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software). Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test unless otherwise noted. Asterisks in graphs indicate the significance of P values comparing indicated group with controls unless specifically indicated (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Generation of kud knockout flies

The kud knockout lines were generated by homologous recombination as described previously (Huang et al., 2008). In brief, the crossing strategies were divided into three steps: targeting, screening, and mapping crosses. In targeting crosses, virgin females of a transgenic line bearing the donor DNA (“P {kud}”) were crossed with 6934-hid males (yw/Y, hs-hid; hs-FLP, hs-I-SceI/CyO, hs-hid) for egg laying over 24 h. The vials were then heat-shocked twice at 38°C for 1.5 h during 2 d. The linear donor DNA fragments (P[kud]Rpr+) were generated extrachromosomally by FLP and I-SceI enzymes and inserted into the targeted chromosome. In screening crosses, virgin females (yw; hs-FLP,hs-I-SceI/P[kud]Rpr+) from the targeting crosses were mated with balancer males expressing GAL4477 (yw/Y; GAL4477w-]; TM2/TM6B) to eliminate any failed positive candidates. In mapping crosses, the candidates of kud knockout lines with red eyes (yw/Y; hs-FLP, hs-I-SceI/GAL4477w-]; kudKO/TM6B or TM2) were selected and crossed with balancer flies (Dr/TM6B) individually to maintain them.

Generation of constructs and transgenic flies

The whole coding region of Kud was amplified from the S2 cell cDNA library and cloned into pGEM–T-Easy vector to generate pGEM–T-Kud (Promega). 3HA DNA was subcloned into pGEM–T-Kud, and C-terminally tagged Kud-3HA was subcloned into pUAST. KudΔN, KudIM-N, and KudTM-U was amplified by multiple-step PCR from the templates possessing Kud-3HA, Nrg TM, and Uzip TM DNA, respectively (Ding et al., 2011) and cloned into pGEM–T-Easy vector. The DNA segments were subcloned into pUAST-CFP vector to generate the C-terminally tagged Kud variants (Drosophila Genomics Resource Center), and KudΔN-3HA was subcloned into pUAST. KudLGA, KudNGA, KudIM-J, and KudTM-J DNA were synthesized by Quantum Biotechnology. The synthesized DNA segments were cloned into pMX vectors. To generate the C-terminally tagged Kud variants, these DNA segments were subcloned into pUAST-GFP vectors whose GFP was amplified from genomic DNA of UAS-Syt1-GFP fly. sym-pUAST-kud was generated by subcloning the full-length Kud into sym-pUAST (Giordano et al., 2002), which can produce double-stranded RNA in vivo.

C-terminally tagged KASH(Klar)-3HA and KASH(Msp300)-3HA were amplified by three-step PCR from the S2 cell cDNA library and pGEMT-Kud-3HA and were cloned into pGEM–T-Easy vector. N-terminally tagged 3HA-KASH(Klar) was amplified by three-step PCR from pMT/V5-KASH(Klar)-3HA. The amplified cDNAs were cloned into pGEM–T-Easy vector and was subcloned into pMT/V5 or pUAST. pMT/V5-Kud-His was generated by replacing the full-length Kud into pMT/V5-Uzip-His (Ding et al., 2011). TMEM258 was amplified by PCR from cDNA of 293T cells. KASH(Syne1)-3HA was amplified by three-step PCR from the cDNA library of 293T cell and pGEMT-Kud-3HA. The amplified cDNAs were cloned into pGEM–T-Easy vector and were subcloned into pcDNA3.1/myc-His vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific). pcDNA3-hSUN1-dHA, pcDNA3-dFLAG-hSYNE1, pcDNA3-dFLAG-hSYNE1 (1–922; KASH deletion), pcDNA3-dFLAG-hSYNE2, pcDNA3-dFLAG-hSYNE2 (1–498; KASH deletion), pcDNA3-dFLAG-BAF (Chi et al., 2007), and pcDNA3-dFLAG-STIM1 were provided by Y.-H. Chi (National Health Research Institutes, Zhunan, Taiwan). Full-length Syne1 v3 (983 aa) was cloned from cDNA of KIAA0796, and full-length Syne2 v4 (556 aa) was cloned from RT-PCR.

pUAST clones were microinjected into w1118 early stage embryos, which carried transposase Δ2–3 for generating UAS transgenic flies. Constructs of pMT/V5, pUAST, and pWA-GAL4 were used to express proteins in S2 cells. pcDNA3 constructs were used to express proteins in human 293T cells.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 illustrates the generation of kud knockout mutants. Fig. S2 indicates that cytoplasmic Kud can localize at the ER membrane but not the ER lumen, Golgi, or mitochondria. Fig. S3 illustrates a proteinase K protection assay of the topology of TMEM258 and dimerization of Kud. Fig. S4 shows that loss of LINC components does not affect the NE targeting of Kud, and loss of Kud does not affect the level of LamDm0. Fig. S5 shows that mutation in kud does not impair the nuclear migration of photoreceptors in Drosophila eyes.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Elhanany-Tamir for klar mutant, M. Technau for msp300 mutant, M. P. Kracklauer for koi mutant, M.-D. Lin for KDEL antibody, G.-C. Chen for UAS-Atg1 fly and Atg8a antibody, the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for public fly strains, the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies, FlyCore in Taiwan for assistance, H.-H. Lee of National Taiwan University for the fly for homologous recombination, L.-C. Chi and Y.-C. Liu for assistance in experiments, and C.-T. Chien of Academia Sinica for discussion and comments.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan grant 103-2311-B-194-001-MY3.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: Z.-Y. Ding and Y.-H. Wang performed most of the experiments. Y.-C. Huang generated some plasmids and initially observed phenotypes. M.-C. Lee generated kud knockout flies. M.-J. Tseng helped with human cell culture system. Y.-H. Chi provided several plasmids used in human cell experiments and commented on the manuscript. Z.-Y. Ding, Y.-H. Wang, and M.-L. Huang designed and interpreted the experiments and wrote the paper. M.-L. Huang supervised the project.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- coIP

- coimmunoprecipitation

- CR

- contour ratio

- FRT

- flippase recombination target

- IM

- intramembrane

- INM

- inner nuclear membrane

- KASH

- Klarsicht/ANC-1/SYNE homology

- LINC

- linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton

- NE

- nuclear envelope

- NPC

- nuclear pore complex

- NR

- nucleoplasmic reticulum

- ONM

- outer nuclear membrane

- PNS

- perinuclear space

- SUN

- Sad1/UNC-84

- TAN

- transmembrane actin-associated nuclear

- TM

- transmembrane domain

References

- Adachi, N., Karanjawala Z.E., Matsuzaki Y., Koyama H., and Lieber M.R.. 2002. Two overlapping divergent transcription units in the human genome: The FEN1/C11orf10 locus. OMICS. 6:273–279. 10.1089/15362310260256927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attali, R., Warwar N., Israel A., Gurt I., McNally E., Puckelwartz M., Glick B., Nevo Y., Ben-Neriah Z., and Melki J.. 2009. Mutation of SYNE-1, encoding an essential component of the nuclear lamina, is responsible for autosomal recessive arthrogryposis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18:3462–3469. 10.1093/hmg/ddp290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth, J.M., Szabad J., Hafen E., and Köhler K.. 2011. Autophagy in Drosophila ovaries is induced by starvation and is required for oogenesis. Cell Death Differ. 18:915–924. 10.1038/cdd.2010.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochenek, G., Häsler R., El Mokhtari N.E., König I.R., Loos B.G., Jepsen S., Rosenstiel P., Schreiber S., and Schaefer A.S.. 2013. The large non-coding RNA ANRIL, which is associated with atherosclerosis, periodontitis and several forms of cancer, regulates ADIPOR1, VAMP3 and C11ORF10. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22:4516–4527. 10.1093/hmg/ddt299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boni, A., Politi A.Z., Strnad P., Xiang W., Hossain M.J., and Ellenberg J.. 2015. Live imaging and modeling of inner nuclear membrane targeting reveals its molecular requirements in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 209:705–720. 10.1083/jcb.201409133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand, A.H., and Perrimon N.. 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 118:401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, B., and Stewart C.L.. 2014. Functional architecture of the cell’s nucleus in development, aging, and disease. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 109:1–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W., Worman H.J., and Gundersen G.G.. 2015. Accessorizing and anchoring the LINC complex for multifunctionality. J. Cell Biol. 208:11–22. 10.1083/jcb.201409047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.Y., Chi Y.H., Mutalif R.A., Starost M.F., Myers T.G., Anderson S.A., Stewart C.L., and Jeang K.T.. 2012. Accumulation of the inner nuclear envelope protein Sun1 is pathogenic in progeric and dystrophic laminopathies. Cell. 149:565–577. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.C., Lee J.Y., Tang H.W., Debnath J., Thomas S.M., and Settleman J.. 2008. Genetic interactions between Drosophila melanogaster Atg1 and paxillin reveal a role for paxillin in autophagosome formation. Autophagy. 4:37–45. 10.4161/auto.5141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi, Y.H., Haller K., Peloponese J.M. Jr., and Jeang K.T.. 2007. Histone acetyltransferase hALP and nuclear membrane protein hsSUN1 function in de-condensation of mitotic chromosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 282:27447–27458. 10.1074/jbc.M703098200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.Y., Wang Y.H., Luo Z.K., Lee H.F., Hwang J., Chien C.T., and Huang M.L.. 2011. Glial cell adhesive molecule unzipped mediates axon guidance in Drosophila. Dev. Dyn. 240:122–134. 10.1002/dvdy.22508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drin, G., and Antonny B.. 2010. Amphipathic helices and membrane curvature. FEBS Lett. 584:1840–1847. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhanany-Tamir, H., Yu Y.V., Shnayder M., Jain A., Welte M., and Volk T.. 2012. Organelle positioning in muscles requires cooperation between two KASH proteins and microtubules. J. Cell Biol. 198:833–846. 10.1083/jcb.201204102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, J.A., Acosta S., Kenny A., Cater C., Robinson C., and Hook J.. 2004. Drosophila klarsicht has distinct subcellular localization domains for nuclear envelope and microtubule localization in the eye. Genetics. 168:1385–1393. 10.1534/genetics.104.028662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.B., Brenman J.E., Jan L.Y., and Jan Y.N.. 1999. Genes regulating dendritic outgrowth, branching, and routing in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 13:2549–2561. 10.1101/gad.13.19.2549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier, R., Douguet D., Antonny B., and Drin G.. 2008. HELIQUEST: a web server to screen sequences with specific α-helical properties. Bioinformatics. 24:2101–2102. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, E., Rendina R., Peluso I., and Furia M.. 2002. RNAi triggered by symmetrically transcribed transgenes in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 160:637–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giot, L., Bader J.S., Brouwer C., Chaudhuri A., Kuang B., Li Y., Hao Y.L., Ooi C.E., Godwin B., Vitols E., et al. 2003. A protein interaction map of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 302:1727–1736. 10.1126/science.1090289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, R.D., Shumaker D.K., Erdos M.R., Eriksson M., Goldman A.E., Gordon L.B., Gruenbaum Y., Khuon S., Mendez M., Varga R., and Collins F.S.. 2004. Accumulation of mutant lamin A causes progressive changes in nuclear architecture in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:8963–8968. 10.1073/pnas.0402943101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, D.B., Lefkovith A., Deelen P., de Klein N., Varma M., Boroughs A., Desch A.N., Ng A.C., Guzman G., Schenone M., et al. 2016. TMEM258 is a component of the oligosaccharyltransferase complex controlling ER stress and intestinal inflammation. Cell Reports. 17:2955–2965. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros-Louis, F., Dupré N., Dion P., Fox M.A., Laurent S., Verreault S., Sanes J.R., Bouchard J.P., and Rouleau G.A.. 2007. Mutations in SYNE1 lead to a newly discovered form of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia. Nat. Genet. 39:80–85. 10.1038/ng1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y., Jangi S., and Welte M.A.. 2005. Organelle-specific control of intracellular transport: Distinctly targeted isoforms of the regulator Klar. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:1406–1416. 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn, H.F., Brownstein Z., Lenz D.R., Shivatzki S., Dror A.A., Dagan-Rosenfeld O., Friedman L.M., Roux K.J., Kozlov S., Jeang K.T., et al. 2013. The LINC complex is essential for hearing. J. Clin. Invest. 123:740–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J., Zhou W., Watson A.M., Jan Y.N., and Hong Y.. 2008. Efficient ends-out gene targeting in Drosophila. Genetics. 180:703–707. 10.1534/genetics.108.090563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight, M.A., Hernandez D., Diede S.J., Dauwerse H.G., Rafferty I., van de Leemput J., Forrest S.M., Gardner R.J., Storey E., van Ommen G.J., et al. 2008. A duplication at chromosome 11q12.2–11q12.3 is associated with spinocerebellar ataxia type 20. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17:3847–3853. 10.1093/hmg/ddn283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kracklauer, M.P., Banks S.M., Xie X., Wu Y., and Fischer J.A.. 2007. Drosophila klaroid encodes a SUN domain protein required for Klarsicht localization to the nuclear envelope and nuclear migration in the eye. Fly (Austin). 1:75–85. 10.4161/fly.4254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T., and Luo L.. 1999. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 22:451–461. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80701-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.K., Starr D., Cohen M., Liu J., Han M., Wilson K.L., and Gruenbaum Y.. 2002. Lamin-dependent localization of UNC-84, a protein required for nuclear migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13:892–901. 10.1091/mbc.01-06-0294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei, K., Zhang X., Ding X., Guo X., Chen M., Zhu B., Xu T., Zhuang Y., Xu R., and Han M.. 2009. SUN1 and SUN2 play critical but partially redundant roles in anchoring nuclei in skeletal muscle cells in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:10207–10212. 10.1073/pnas.0812037106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W., Schneider M., Neumann S., Jaeger V.M., Taranum S., Munck M., Cartwright S., Richardson C., Carthew J., Noh K., et al. 2012. Nesprin interchain associations control nuclear size. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69:3493–3509. 10.1007/s00018-012-1034-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüke, Y., Zaim H., Karakesisoglou I., Jaeger V.M., Sellin L., Lu W., Schneider M., Neumann S., Beijer A., Munck M., et al. 2008. Nesprin-2 Giant (NUANCE) maintains nuclear envelope architecture and composition in skin. J. Cell Sci. 121:1887–1898. 10.1242/jcs.019075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, M., Zhao X., Song Y., Cheng H., and Zhou R.. 2016. Nuclear autophagy: An evolutionarily conserved mechanism of nuclear degradation in the cytoplasm. Autophagy. 12:1973–1983. 10.1080/15548627.2016.1217381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luxton, G.W., Gomes E.R., Folker E.S., Vintinner E., and Gundersen G.G.. 2010. Linear arrays of nuclear envelope proteins harness retrograde actin flow for nuclear movement. Science. 329:956–959. 10.1126/science.1189072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv, X.B., Liu L., Cheng C., Yu B., Xiong L., Hu K., Tang J., Zeng L., and Sang Y.. 2015. SUN2 exerts tumor suppressor functions by suppressing the Warburg effect in lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 5:17940. 10.1038/srep17940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhas, A.N., and Vaux D.J.. 2014. Nuclear envelope invaginations and cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 773:523–535. 10.1007/978-1-4899-8032-8_24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, A., Hieda M., Yokoyama Y., Nishioka Y., Yoshidome K., Tsujimoto M., and Matsuura N.. 2015. Global loss of a nuclear lamina component, lamin A/C, and LINC complex components SUN1, SUN2, and nesprin-2 in breast cancer. Cancer Med. 4:1547–1557. 10.1002/cam4.495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, H.T., and Gallop J.L.. 2005. Membrane curvature and mechanisms of dynamic cell membrane remodelling. Nature. 438:590–596. 10.1038/nature04396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosley-Bishop, K.L., Li Q., Patterson L., and Fischer J.A.. 1999. Molecular analysis of the klarsicht gene and its role in nuclear migration within differentiating cells of the Drosophila eye. Curr. Biol. 9:1211–1220. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80501-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarkar-Jaiswal, S., Lee P.T., Campbell M.E., Chen K., Anguiano-Zarate S., Gutierrez M.C., Busby T., Lin W.W., He Y., Schulze K.L., et al. 2015. A library of MiMICs allows tagging of genes and reversible, spatial and temporal knockdown of proteins in Drosophila. eLife. 4:e05338. 10.7554/eLife.05338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, K., Molofsky A.B., Robinson C., Acosta S., Cater C., and Fischer J.A.. 2004. The functions of Klarsicht and nuclear lamin in developmentally regulated nuclear migrations of photoreceptor cells in the Drosophila eye. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:600–610. 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckelwartz, M.J., Kessler E., Zhang Y., Hodzic D., Randles K.N., Morris G., Earley J.U., Hadhazy M., Holaska J.M., Mewborn S.K., et al. 2009. Disruption of nesprin-1 produces an Emery Dreifuss muscular dystrophy-like phenotype in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18:607–620. 10.1093/hmg/ddn386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.J., Lin Y.Y., Ding J.X., Feng W.W., Jin H.Y., and Hua K.Q.. 2015. Long non-coding RNA ANRIL predicts poor prognosis and promotes invasion/metastasis in serous ovarian cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 46:2497–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajgor, D., and Shanahan C.M.. 2013. Nesprins: from the nuclear envelope and beyond. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 15:e5. 10.1017/erm.2013.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randles, K.N., Lam T., Sewry C.A., Puckelwartz M., Furling D., Wehnert M., McNally E.M., and Morris G.E.. 2010. Nesprins, but not sun proteins, switch isoforms at the nuclear envelope during muscle development. Dev. Dyn. 239:998–1009. 10.1002/dvdy.22229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ, W.P., and Engelman D.M.. 2000. The GxxxG motif: A framework for transmembrane helix-helix association. J. Mol. Biol. 296:911–919. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, D., and Engelman D.M.. 2004. Motifs of two small residues can assist but are not sufficient to mediate transmembrane helix interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 343:799–804. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E.R., Zhang X.Y., Capo-Chichi C.D., Chen X., and Xu X.X.. 2011. Increased expression of Syne1/nesprin-1 facilitates nuclear envelope structure changes in embryonic stem cell differentiation. Dev. Dyn. 240:2245–2255. 10.1002/dvdy.22717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosa, B.A., Rothballer A., Kutay U., and Schwartz T.U.. 2012. LINC complexes form by binding of three KASH peptides to domain interfaces of trimeric SUN proteins. Cell. 149:1035–1047. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosa, B.A., Kutay U., and Schwartz T.U.. 2013. Structural insights into LINC complexes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 23:285–291. 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr, D.A. 2009. A nuclear-envelope bridge positions nuclei and moves chromosomes. J. Cell Sci. 122:577–586. 10.1242/jcs.037622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr, D.A., and Han M.. 2002. Role of ANC-1 in tethering nuclei to the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 298:406–409. 10.1126/science.1075119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl, G., and Basler K.. 1993. Organizing activity of wingless protein in Drosophila. Cell. 72:527–540. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90072-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taranum, S., Sur I., Müller R., Lu W., Rashmi R.N., Munck M., Neumann S., Karakesisoglou I., and Noegel A.A.. 2012. Cytoskeletal interactions at the nuclear envelope mediated by nesprins. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012:736524. 10.1155/2012/736524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Technau, M., and Roth S.. 2008. The Drosophila KASH domain proteins Msp-300 and Klarsicht and the SUN domain protein Klaroid have no essential function during oogenesis. Fly (Austin). 2:82–91. 10.4161/fly.6288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungricht, R., Klann M., Horvath P., and Kutay U.. 2015. Diffusion and retention are major determinants of protein targeting to the inner nuclear membrane. J. Cell Biol. 209:687–703. 10.1083/jcb.201409127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters, A.D., Bommakanti A., and Cohen-Fix O.. 2012. Shaping the nucleus: Factors and forces. J. Cell. Biochem. 113:2813–2821. 10.1002/jcb.24178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.Y., Yu I.S., Huang C.C., Chen C.Y., Wang W.P., Lin S.W., Jeang K.T., and Chi Y.H.. 2015. Sun1 deficiency leads to cerebellar ataxia in mice. Dis. Model. Mech. 8:957–967. 10.1242/dmm.019240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsen, K., Ketema M., Truong H., and Sonnenberg A.. 2006. KASH-domain proteins in nuclear migration, anchorage and other processes. J. Cell Sci. 119:5021–5029. 10.1242/jcs.03295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worman, H.J., and Schirmer E.C.. 2015. Nuclear membrane diversity: underlying tissue-specific pathologies in disease? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 34:101–112. 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T., and Rubin G.M.. 1993. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 117:1223–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q., Bethmann C., Worth N.F., Davies J.D., Wasner C., Feuer A., Ragnauth C.D., Yi Q., Mellad J.A., Warren D.T., et al. 2007. Nesprin-1 and -2 are involved in the pathogenesis of Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy and are critical for nuclear envelope integrity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16:2816–2833. 10.1093/hmg/ddm238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]