SUMMARY

Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica includes several serovars infecting both humans and other animals and leading to typhoid fever or gastroenteritis. The high prevalence of associated morbidity and mortality, together with an increased emergence of multidrug-resistant strains, is a current global health issue that has prompted the development of vaccination strategies that confer protection against most serovars. Currently available systemic vaccine approaches have major limitations, including a reduced effectiveness in young children and a lack of cross-protection among different strains. Having studied host-pathogen interactions, microbiologists and immunologists argue in favor of topical gastrointestinal administration for improvement in vaccine efficacy. Here, recent advances in this field are summarized, including mechanisms of bacterial uptake at the intestinal epithelium, the assessment of protective host immunity, and improved animal models that closely mimic infection in humans. The pros and cons of existing vaccines are presented, along with recent progress made with novel formulations. Finally, new candidate antigens and their relevance in the refined design of anti-Salmonella vaccines are discussed, along with antigen vectorization strategies such as nanoparticles or secretory immunoglobulins, with a focus on potentiating mucosal vaccine efficacy.

KEYWORDS: Salmonella, immunity, vaccination, gastrointestinal mucosa

INTRODUCTION

Salmonella enterica is a facultative intracellular Gram-negative bacterium which comprises 6 subspecies (S. enterica subsp. arizonae, S. enterica subsp. diarizonae, S. enterica subsp. enterica, S. enterica subsp. houtenae, S. enterica subsp. indica, and S. enterica subsp. salamae). Among them, S. enterica subsp. enterica includes 1,531 serovars as of 2007, themselves divided in serogroups based on the antigenic variability of the O antigen in the outer membrane lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Several serovars are well known for their implication in food-related diarrhea-inducing diseases acquired via the fecal-oral route (1–3). The typhoidal Salmonella (TS) serovars S. enterica subsp. enterica Typhi (S. Typhi) (O:9) and S. enterica subsp. enterica Paratyphi A (S. Paratyphi) (O:2) exclusively infect humans and cause enteric fever, also referred to as typhoid fever. It is characterized by a systemic infection causing fever, respiratory distress, and hepatic, spleen, and neurological damage. TS-mediated infection strikes up to 21.7 million people in Africa, South and Central America, and Asia; the highest prevalence is reported in Southeast Asia (4), with a death rate of about 1%. Overall, this results in more than 200,000 deaths per year in countries with limited incomes (5). The nontyphoidal Salmonella (NTS) serovars S. enterica subsp. enterica Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) (O:4) and S. enterica subsp. enterica Enteritidis (S. Enteritidis) (O:9) infect both humans and animals and are among the major causal agents of self-limiting gastroenteritis, a local infection that causes diarrhea (6). The areas where NTS disease is prevalent are located mostly in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as in south Asian countries, because of poor health care systems, malnutrition, and possible zoonotic transmission (7–9). Through food contamination, episodic outbreaks are also reported in developed countries, which may be caused by other serogroups, including O:7 and O:8 (10–13). In 2010, the estimated burden of NTS infection accounted for 93.8 million cases and 155,000 casualties (14). Infection by specific strains of S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis may ultimately lead to systemic dissemination, referred to as invasive NTS. This results in high case fatality rates, especially for children below 3 years of age and for immunodeficient HIV- or malaria-infected individuals (7, 15), and adds 3.4 million cases and 681,316 deaths to the global NTS toll (16). The difference in disease symptoms resulting from TS and NTS can be explained by either mutation-induced loss of function or the deletion of around 11% of coding sequences between S. Typhimurium and S. Typhi, which may be partly due to the host-specific adaptation of each particular serovar (17). Genome modifications include, for example, the expression of different virulence genes, such as the Vi capsular polysaccharide gene, which is expressed by particular Salmonella serovars, including, for example, S. Typhi, S. Paratyphi B, and S. Dublin (18–20). All the genetic, phenotypic, and pathogenesis differences indicate that TS and NTS have to be separately studied.

Currently, patients presenting either an acute invasive NTS- or TS-induced infection undergo antimicrobial treatment (21), often composed of fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ampicillin, or cephalosporins with a large spectrum of action. In spite of a good efficacy, these protocols are deemed to be increasingly limited in their use because of the appearance of multidrug resistance (MDR) for S. Typhimurium (22, 23), S. Enteritidis (24), S. Typhi (25–27), and S. Paratyphi (28). Several factors contribute to reduce the efficiency of a targeted antimicrobial treatment, such as, subpopulations of Salmonella showing increased survival after exposure to antibiotics (29), the presence in the host of more than one strain with different antibiotic sensitivity (30), and the possibility of transferring the resistance between bacteria (27, 31, 32).

The high morbidity and mortality and the inevitably increased exposure to MDR strains underscore the rationale fear of new epidemics (33). In this respect, vaccination remains a valid and needed approach for humans but also in the veterinary field, as NTS also affects livestock and farm poultry (34). As efforts toward the development of efficacious vaccines will inherently result in unexpected difficulties, the knowledge acquired in both Salmonella physiopathology and the host's mechanisms of defense is an essential asset to overcome them (35). The identification of relevant Salmonella antigens (Ags) and improved Ag delivery systems to be integrated within vaccine preparations will help to promote the activation of the host adaptive immune system. The gastrointestinal (GI) tropism of Salmonella enterica suggests that mucosal application of vaccines might be favored, with the aims of targeting specialized sampling sites such as Peyer's patches (PPs) (36) within the epithelium and of mobilizing a robust local T cell and antibody response in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). However, even if the GALT is the primary site where pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are detected to trigger local responses (36), invading Salmonella will eventually have to be recognized by the systemic immune system as well. This emphasizes the likely need to include more than one Ag in vaccine formulations to prime multiple specific arms of the immune system at various stages of infection (37).

This review compiles the current knowledge acquired from past and present studies that have helped to define key parameters instrumental in the design of an efficient anti-Salmonella vaccine. Mechanisms of Salmonella-host interaction resulting in bacterial uptake, as well as the innate and adaptive anti-Salmonella protective immunity, are discussed first. Currently available vaccines and how to possibly overcome their limits are presented next. We finish by considering the potential of novel candidate Salmonella-derived Ags and their possible combination with recently developed mucosal delivery systems.

SAMPLING OF AND IMMUNE RESPONSES TO SALMONELLA IN THE HOST GUT

Interaction with and Uptake by the Host

After overcoming physicochemical obstacles protecting the epithelium (38), Salmonella (S. Typhimurium for most experimental investigations) penetrates the gut epithelium barrier by three routes, i.e., crossing via microfold (M) cells in PPs, intracellular invasion of epithelial cells, or through breaches in the epithelial lining.

M cells interspersed among the enterocytes covering the follicle-associated epithelium of the PPs and isolated lymphoid follicles are specialized cells that selectively sample intact microorganisms and/or soluble Ags and deliver the latter to the underlying lamina propria. Entry of non-self molecules is supported by the absence of MUC2 (a gel-forming mucin that is part of mucus) on the surface of M cells. Elsewhere along the gut, this main component of mucus physically decreases the attachment of bacteria on epithelial cells and contains antimicrobial defensins secreted by Paneth cells to chemically kill bacteria (39, 40). Following passage across M cells, the Ag is captured by Ag-presenting cells (APCs), including dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages residing in the M cell pocket or located in the subepithelial dome region of PPs. Macrophages play a role in the elimination of engulfed bacteria and local production of cytokines, whereas DCs are key initiators of protective adaptive immune responses following migration to the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs). In the case of Salmonella, entry in M cells induces their rapid apoptosis and results in subsequent invasion of macrophages and gut epithelial cells via Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) located at the basolateral surface. Direct luminal engulfment of Salmonella by intestinal epithelial cells also occurs via disturbance of cellular actin polymerization and cytoskeleton organization (41) mediated by injection of effector proteins through the type III secretion system (T3SS). This triggers characteristic membrane ruffling, a prominent cellular change accompanied by induced cell death (42). The sum of these processes causes an increase of epithelium permeability leading to massive invasion and dissemination.

More direct sampling of bacteria occurs through luminal uptake as well: at steady state and following infection, lamina propria C-X-3-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1)-expressing DCs displaying transepithelial dendrites capture Salmonella directly from the lumen (43). In another mechanism, intestinal CD103+ DCs in the mouse lamina propria are recruited in the intestinal epithelium upon gut challenge with S. Typhimurium, inducing transepithelial protrusion of their dendrites to capture luminal bacteria (44). Mechanistically, it has been observed that transepithelial dendrite extension is induced via engagement by Salmonella of TLRs expressed by epithelial cells (45). It is noteworthy that whatever the DC subtype analyzed, these extensions appear without compromising the integrity of the epithelial barrier, most likely as a consequence of the formation of tight-junction-like structure linking the dendrites and the contiguous epithelial cells.

Recently identified mechanisms have shed additional light on the subtle complexity of the interaction between Salmonella and the host epithelium. In neonate mice, Salmonella invasion and proliferation are more pronounced than in older animals (46), arguing that epithelial maturation and a lower turnover of epithelial cells contribute to limit bacterial aggressiveness. This refinement in the sensing of the bacterium by the host may account for the large number of different proteins expressed by Salmonella that bind to the extracellular matrix on epithelial cells. In addition, Salmonella may also be recognized by plasma membrane receptors. Among the several receptors present on the M cell surface recognizing PAMPs (47), glycoprotein 2 (GP2) associates with Salmonella via the FimH pilus component; the absence of GP2 in knockout mice leads to a drop of the Salmonella burden in PPs, resulting in a concomitant reduction of antibody production against the bacterium (48). Annexin A5, a protein expressed on the apical side of M cells, has been identified as a receptor for the lipid A domain of the LPS moiety found on Gram-negative bacteria (49). Salmonella flagellin was defined as a key actor in promoting M cell differentiation through its capacity to trigger secretion of C-C motif chemokine ligand 20 (CCL20) by epithelial cells, a chemokine-inducing recruitment of DCs involved in the conversion of epithelial cells into M cells (50). Along the same line, the Salmonella-secreted SopB protein contributes to increase host invasion by converting epithelial cells in the follicle-associated epithelium into M cells (51). It remains to be determined whether this process is beneficial for Salmonella finding its entryway or whether this may be seen as a means for the host to increase Ag sampling and thus to reinforce the intensity of the local immune response. Of note, while S. Typhimurium remains the preferential serovar for studying infection, the path of epithelial entry of S. Typhi is less well known. S. Typhi can be taken up by M cells, but more comprehensive mechanical investigations are needed to resolve similarities and differences between the two serovars in view of designing an optimal vaccine that displays the highest spectrum of action. Altogether, based on the numerous strategies used by the host to sense Salmonella at the level of the epithelial barrier, targeting these pathways in order to elicit a strong mucosal response appears to be a promising approach.

GALT Features Important for Vaccine Design

The GALT is characterized by a complex network of cellular and molecular players which confer the capacity to differentiate harmless Ags such as nutrients or commensal bacteria from PAMPs carried by pathogens. The tolerogenic environment of the intestinal tract thus has to be seen as an additional challenge to overcome when it comes to defining vaccine formulation for oral administration. In this respect, understanding the nature of the immune responses during Salmonella infection is crucial for several reasons: (i) to engineer a vaccine which will elicit protective responses close as those induced by the invading bacterium, (ii) to select for the best Ag(s) to efficiently protect at the mucosal and systemic levels, (iii) to trigger specific and prolonged (memory) activation of the immune system, and (iv) to avoid immune tolerance or adverse effects associated with a defect in homeostasis. Nowadays, a relatively clear picture of the most important immune actors involved in fighting Salmonella infection has been established (Fig. 1).

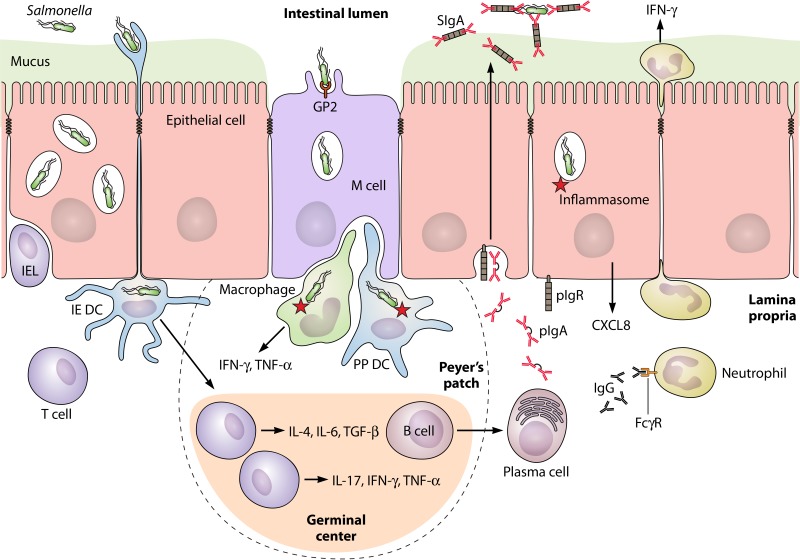

FIG 1.

Schematic overview of the mucosal immune response against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. In the follicle-associated epithelium, bacterial sampling occurs via the GP2 receptor on M cells and to a lesser extent by direct lumenal capture through dendritic cells (DCs) extending their dendrites across the epithelium (intraepithelial [IE] DCs). Uptake by macrophages in the Peyer's patch (PP) induces the onset of intracellular reactions mediated by the inflammasome network of proteins, resulting in the local production of numerous proinflammatory mediators. DCs in the subepithelial dome of PPs process M cell-transported Salmonella for presentation to T cells residing in the interfollicular region of the germinal center. This results in their differentiation into effectors with profiles reinforcing the inflammatory Th1/Th17 responses or favoring production of a Th pattern prone to prime B cells to switch to polymeric IgA (pIgA) production. T and plasma cells ensure local responses and dissemination to distant effector sites after migration to the mesenteric lymph nodes and circulation (not shown). Polymeric IgA is transcytosed from the lamina propria to intestinal secretions by the epithelial polymeric Ig receptor (pIgR); the resulting complex, called secretory IgA (SIgA), specifically recognizes Salmonella and prevents its attachment to the epithelium, a function referred to as immune exclusion. Natural IgM can similarly be transported by the pIgR and ensures a similar neutralizing function (not shown). Intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) participate in protection through their cytotoxic function and cytokine production. Upon epithelial sensing of Salmonella, released CXCL8 attracts neutrophils which participate in protection by locally secreting IFN-γ. Mucosal exudation of Salmonella-specific IgG from the circulation contributes to bacterial neutralization and activation of neutrophils via Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) in the lamina propria. The figure is not drawn to scale.

Contribution of innate immunity.

Cellular and molecular partners involved in innate mechanisms of protection against Salmonella have been extensively studied and have been discussed in detail in recent reviews (52–54). In the face of this extensive literature, we have chosen to deliberately deal with this aspect in the frame of Salmonella vaccination more succinctly.

In the absence of any contribution by Ag-specific T and B cells, innate immunity in the mouse depends on membrane-bound TLRs (55) and cytosolic nucleotide binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs) (56) recognizing bacterial PAMPs. Subsequent activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) mediates induction of proinflammatory cytokines, including interferon gamma (IFN-γ) (57, 58) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (59). In turn, this stimulates cellular effector mechanisms (35, 60) that compromise intracellular and extracellular Salmonella survival and proliferation. The relevance of these innate pathways is shown in humans suffering from rare primary immunodeficiencies, who exhibit severe systemic invasion by Salmonella. In human patients presenting a deficiency in interleukin-12 (IL-12) or IFN-γ and in mice with either gene knocked out, increased susceptibility to infection by Salmonella has been reported (61). A mode of action of IFN-γ relies on the decrease of the intracellular tryptophan level and control of S. Typhi growth, as observed in infected volunteers (62). In comparison with wild-type (WT) animals, macrophage migration inhibitory factor-deficient mice orally infected with S. Typhimurium produce less IFN-γ and TNF-α, show increased bacterial loads in spleen and liver, and exhibit poor survival (63). Production of IFN-γ by either NK cells (64) or neutrophils (57) contributes to ensure protection, suggesting some degrees of redundancy in the source of these two essential protective cytokines.

Simultaneous deletion of TLR2, -4, and -5 in mice infected with S. Typhimurium leads to an absence of TNF-α and CCL2 production and results in poor survival rates in comparison with WT mice (55). Simultaneous deletion of TLR2 and TLR4 in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) decreases secretion of nitric oxide (NO) and TNF-α in response to S. Typhimurium (65). TLR2-mediated recognition of curli amyloid fibrils contributes to the production of proinflammatory IL-17A and IL-22 after Salmonella entry in the intestinal mucosa (66). Consistent with this, epithelium-targeted deletion of the gene for the TLR adaptor molecule myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) in mice results in massive tissue damage and impaired goblet cell function after infection with S. Typhimurium (67). The deletion of MyD88 in mice also induces a decrease of IFN-γ production and subsequent increase of systemic IL-10 (an anti-inflammatory cytokine) (68, 69). Thus, targeting the TLR/MyD88 pathway via a specific “adjuvant” ligand may serve as an interesting strategy to strengthen the innate arm of the immune response against Salmonella.

In addition, nonconventional T cells, often classified as cells with innate-like properties, such as major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-related protein 1 (MR1)-restricted mucosal associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, CD1d-restricted NKT cells, and γ/δ T cells, can play a role in protection against Salmonella infection (70). Recent data show that MAIT cells bind an S. Typhimurium Ag ligand presented in the MR1 context with high affinity (71, 72). Increased local recruitment of MAIT cells secreting principally IL-17A and to a lesser extent IFN-γ and TNF-α after S. Typhimurium infection in mice has also been recently reported (73). In vitro and in vivo experiments have shown an IL-12-dependent IFN-γ production by CD1d-restricted NKT cells following S. Typhimurium recognition (74, 75). Depletion of γ/δ T cells through treatment with T cell receptor (TCR)-specific monoclonal antibodies in mice decreases by 300-fold the 50% lethal dose of S. Enteritidis administered orally (76). In a mouse model allowing tracking of intraepithelial γ/δ T cells, deficient migration in the intestinal epithelium increases S. Typhimurium translocation and leads to salmonellosis of greater severity (77). Whether the activation status of these cells is a marker to be studied postvaccination and whether they might be targeted by vaccine formulations remain open at this stage.

Involvement of innate immunity is clearly instrumental as indicated by the many manners it contributes to Salmonella clearance. Along the same line, the TLR signaling circuit of the inflammasome pathway (78, 79) and several nonconventional T cell subsets may act in addition to or in synergy with adaptive mechanisms induced by vaccination, yet such a cross talk is in need of investigation. Targeting one or combining several innate immune pathways with PAMP-derived adjuvants integrated in vaccine formulations can be seen as a valuable exploratory process to convert a slightly protective vaccine to a highly efficient one. This would also contribute to addressing the challenge of identifying potent orally active and safe adjuvants for vaccination in humans.

Role of adaptive immunity.

Innate immunity is an efficient first line of defense against pathogen infection; however, the establishment of a full specific and long-lasting protection relies on the induction of both humoral and cellular immunity. Understanding the mechanisms leading to efficient adaptive immune responses against Salmonella infection is hence crucial to design optimized vaccine candidates.

To elicit mucosal immunity, intestinal DCs acting as professional APCs must take up Ags and deliver them to draining MLNs (80). DCs in both the subepithelial dome region of PPs and the lamina propria require expression of C-C motif chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7) to migrate to MLNs, where the inflammatory context primed by enteropathogens favors the induction of effector T cells imprinted for gut homing (81, 82). Specifically, upon challenge with Salmonella, intestinal CD11c+ CD11b+ CD103+ DCs are apparently the only subtype equipped with a battery of functions to independently complete the processes of uptake, transportation, and presentation of bacterial Ags (44). However, these results have been challenged in a recent study showing that the decrease of this DC population in interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4)-depleted mice did not change the local and systemic burden of S. Typhimurium after infection, either the proportion of specific IFN-γ-secreting T cells or the serum levels of Salmonella-specific IgM and IgG (83). Under conditions of antibiotic-induced dysbiosis, CD103− CX3CR1hi mononuclear phagocytes expressing CCR7 have been shown to traffic S. Typhimurium to the MLNs and elicit T cell responses and IgA production (84). This suggests that both the presence of the microbiota and the gut inflammatory condition determine the type of APC subsets that migrate to MLNs and eventually modulate the outcome of the intestinal immune response.

(i) T lymphocytes.

Both IFN-γ-producing CD4+ Th1 cells (85–87) and cytotoxic granzyme/perforin-expressing CD8+ T cells (88) are important contributors of adaptive immunity via the production of antimicrobial cytokines (86), the killing of infected cells, or the generation of memory B cells (85). Interestingly, the TLR signaling adaptor MyD88 has been shown to be crucial for T cell proliferation and Th1 differentiation (69). Suppression of CD4+ T cells by irradiation induces reactivation of latent Salmonella, suggesting the importance of such cells in the control of persistent infection (89). Spatial fine-tuning of specific CD4+ T cell responses in mice orally infected with Salmonella has been reported to occur as a function of the temporal expression of bacterial Ags. A long-lasting systemic CD4+ Th1 cell response to the SseJ Ag of the T3SS persists until bacterial clearance is achieved. In contrast, mucosal flagellin-derived FliC Ag-specific CD4+ T cells with a Th1 and Th17 bias expand and contract concomitantly with the expression of the Ag by Salmonella (37). This suggests that a combination of early transient and late accumulating T cells of different antigenic specificity should ideally be induced to permit optimal vaccine coverage. At the functional level, IL-17A would permit recruitment of neutrophils, but its presence leads to only mild reduction of bacterial loads in the livers and spleens of mice infected with S. Enteritidis (90). Th17 cells have also been shown to trigger the production of antimicrobial peptides (60). In conclusion, a Th1 response is unambiguously protective and must be elicited by the process of vaccination. A secondary role of Th17 or CD8+ T cell subsets in participating in the immune response against Salmonella is required as well. With regard to the design of future vaccines, the functionality of such T cells may serve as a valuable marker to judge the appropriate modulation operating at the level of the immune system, in particular when a protective T cell memory response has to be induced. For example, mixing cinobufagin with formalin-inactivated S. Typhimurium vaccine boosts the Th1 type of responses and enhances the protective efficacy of the vaccine in challenged mice (91).

(ii) B lymphocytes.

Induction of B cell responses after recognition of Salmonella Ags can take place either by a T cell-independent detection of, e.g., polysaccharides or, in the case of polypeptide-specific responses, by interaction of B cells with activated CD40L+ T cells (92). Activation of the T cell-dependent pathway presents the advantage that antibody class switch, affinity maturation, and memory responses are induced. B cell-deficient mice vaccinated with an attenuated strain of S. Typhimurium (SL3261) and then infected with the virulent strain SL1344 display a reduced survival rate compared to WT animals (93). In mice, immunization with Vi polysaccharide from S. Typhi induces protective Ag-specific B1b cells in the peritoneal cavity (94). Along the same line, after infection with S. Typhimurium, protective B1b cells specific for outer membrane protein (Omp) porins OmpC, OmpD, and OmpF are generated (92), suggesting that this B cell subtype can recognize both proteinaceous and nonproteinaceous entities in a T cell-independent manner. Furthermore, transfer of B1b cells from OmpD-immunized mice to B cell-deficient mice results in the production of a sufficient amount of IgM to limit infection following intraperitoneal (i.p.) Salmonella injection (92). B cells also can be directly activated by microbial products through TLRs and MyD88, highlighting the role of adjuvants in vaccination against Salmonella. After immunization with an attenuated S. Typhimurium strain, chimeric mice with MyD88-deficient B cells present a marked decrease in antigen-specific IgG2c, while other isotypes are not or are much less affected (68). In these animals, the absence of the Salmonella-specific B cell receptor (BCR) impedes the activation of Th1 memory cells (95).

Following activation, B cells differentiate into plasma cells, which produce Ag-specific antibodies. In addition to secretory IgA (SIgA) and IgG isotypes, IgM has been demonstrated in areas of endemicity to mediate protection against Salmonella as well (96). Vaccination of volunteers with Ty21a induces secretion of anti-LPS or anti-Omp IgA/IgG by B memory cells (CD27+ IgD−) expressing the α4β7 gut homing integrin (97). Differences in frequency and activation marker expression of memory B cell subsets in volunteers challenged with oral S. Typhi result in various clinical outcomes, arguing further for the importance of B cells in recovery (98). In addition to antibody production, Salmonella-infected B cells can also serve as APCs to activate cytotoxic IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells (99).

Because infection by Salmonella occurs in the intestine before disseminating to systemic compartments, induction of more global humoral immunity is expected as well. It is important to recall that most of the humoral immune response at mucosal surfaces is ensured by SIgA (100). The antibody is essential for the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis, as it fulfills multiple functions, including immune exclusion (101, 102) and homeostatic control of microbiota (103). Further, SIgA quenches inflammatory circuits locally and potentiates the regulatory properties of mucosal DCs and T cells. Prevention or reduction of penetration of the epithelial barrier by enteropathogens via specific SIgA has proven to be a crucial mechanism for efficient protection and maintenance of homeostasis (104, 105). SIgA is produced in response to S. Typhimurium invasion across M cells in PPs via the local B2 cell subtype (106). Specifically, Salmonella LPS-specific IgA Sal4 has been shown to impede Salmonella adhesion and invasion of intestinal enterocytes in vitro when incubated with Salmonella (107, 108). In mice grafted with the hybridoma producing IgA Sal4, the release of SIgA into the GI tract ensures protection against oral bacterial challenge (109). Moreover, IgA recovered from the blood of Salmonella-immunized mice lacking the polymeric Ig receptor (pIgR), ensuring transport of IgA into secretion, reduces invasion of epithelial cells by S. Typhimurium in vitro (110). WT mice orally infected with S. Typhimurium also display a much higher survival rate than their counterparts lacking pIgR. In addition to neutralizing pathogens and preventing their interactions with the epithelium, SIgA antibodies also affect bacterial metabolism. IgA Sal4 recognizes an epitope in the O Ag of Salmonella, inducing alteration in integrity of the outer membrane and assembly of the T3SS (111). The observation that SIgA as such or in complex with bacteria is anchored in the mucus layer overlying the epithelium further reinforces the notion that the antibody is crucial to neutralize Salmonella within the intestinal lumen. This is consistent with the observation that absence of MUC2 increased mouse sensitivity to S. Typhimurium compared to that in WT animals (112).

Interestingly, recent studies suggest that the role of SIgA extends beyond blocking of Salmonella adhesion to the intestinal epithelium. In the mouse model, and as confirmed in the rabbit and in human resections, SIgA has the ability to bind selectively to M cells (113) and to be taken up by reverse transcytosis in a dectin-1-dependent manner (114). Thus, an alternative function of SIgA would be to drive the associated Ag into PPs for presentation under moderately inflammatory conditions (115). Delivery of SIgA-based immune complexes thus guarantees appropriate sampling by M cells in PPs, stabilization of the Ag, and elicitation of immune responses to ensure subsequent protection in the absence of massive epithelial damage.

The knowledge acquired on how to mobilize both innate and adaptive immunity represents an asset for generation of an environment able to trigger appropriate immune responses by vaccination. In the case of Salmonella infection, the adjuvant(s) and delivery system(s) have to be selected based on their ability to induce IgA, IgG, and IgM, as well as Th1 and Th17, responses.

TOWARD NOVEL STRATEGIES FOR VACCINATION AGAINST TS AND NTS

Vaccines against TS: Ty21a and Vi Capsular Polysaccharide

Two licensed vaccines against S. Typhi are currently available, in the forms of the orally administered live attenuated vaccine Ty21a (Vivotif) and the injectable Vi capsular polysaccharide (Vi CPS) vaccine (Typherix or Typhim Vi). The Ty21a vaccine was obtained by nonspecific chemical mutagenesis of the S. Typhi Ty2 strain, resulting in a galE mutant that lacks the enzyme UDP-galactose-4-epimerase (116). This mutation induces bacterial lysis due to the accumulation of galactose derivatives during growth in the host, yet it preserves LPS synthesis. Surprisingly, the mutant no longer expresses the Vi capsule, indicating that the 3-year cumulative efficacy after injection of 3 vaccine doses (51% in adults and children over 5 years [117]) cannot be attributed to this Ag. Vaccination with Ty21a shows cross-protection against both S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi B (118), while another recent study measured cross-reactive multifunctional memory CD8+ T cell-mediated immune responses against S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi A and B in immunized adults (119). At the mechanistic level, this vaccine promotes expression of the mucosal homing receptor α4β7 (120) on lymphocytes, thus ensuring proper local immunity at the site of pathogen entry. The Ty21a strain has proven to be genetically stable (121); however, its fitness in the gut may not be guaranteed. Because of the high dose of vaccine required to achieve immunogenicity and its formulation as large capsules, Ty21a can be prescribed only to children over 5 years of age (122, 123). In immunocompromised individuals infected with HIV or those suffering from malaria (124, 125), vaccination with a live attenuated bacterium also represents an issue.

The Vi CPS vaccine is composed of purified Vi polysaccharide from S. Typhi. A single vaccination dose is sufficient to induce a 3-year cumulative protection in 55% of the vaccinated population. However, troublesome limitations preclude the general applicability of Vi CPS in the at-risk population: (i) the polysaccharide nature of Vi CPS induces only a T cell-independent antibody production, affecting both class switch and affinity maturation; (ii) although a recent study showed antibody responses in infants 30 days after Vi CPS immunization (126), a lack of immunogenicity in the most affected population, i.e., infants under 2 years of age, was reported previously (127); (iii) the Vi CPS vaccine does not protect against the other main pathogenic serovars responsible for either NTS or TS disease; (iv) the parenteral injection of Vi CPS only triggers surface expression of the systemic homing L-selectin on plasma cells; and (v) as Vi CPS is derived from a purified bacterial Ag, it contains traces of typhoidal LPS, which may bias our understanding of its intrinsic immunogenicity (120). Another drawback is that TNF-α secretion in spleen and MLNs is inhibited by the Vi capsule in vivo (128). Other studies have underscored the inhibition of neutrophil recruitment via the Vi CPS, which impedes the secretion of the neutrophil chemoattractant C5a, a component of complement pathway (129). The Vi capsule has also been shown to limit adaptive immunity by suppression of T cell activation and effector function through impairment of early activation signaling pathways (130).

The mechanism of action of the available vaccines remains unclear; indeed, clues as to this aspect are based on empirical observations due to insufficient knowledge of host immunity at the time of their release. The protective efficacy of the two vaccines administered in combination has never been systematically evaluated. One could imagine a three-dose injection of Ty21a with a Vi CPS boost in order to induce broader protection. In support of this, the inactivated whole-cell vaccine targeting S. Typhi has proven to be the most effective in the U.S. and British armed forces, with a 3-year cumulative efficacy of 73%. However, its demonstrated high reactogenicity hindered its use outside military staff. Overall, the various degrees of immunogenicity and protection demonstrated by the above-mentioned anti-Salmonella vaccines, together with troublesome safety issues, preclude their administration to at-risk populations in areas of endemicity (131).

Animal Models To Address Design of Vaccines against Human TS

In the context of vaccine design, a pertinent animal model mimicking as optimally as possible human responses is essential to draw valuable conclusions as to immunogenicity and efficacy. Vaccines have been initially evaluated in a murine model based on infection with the serovars S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis. The model recapitulates human systemic infection by S. Typhi but does not cause symptoms of human typhoid fever (132). Recent progress that has been made toward the development of more relevant infectious animal models is presented below (133) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Animal models to evaluate vaccination protocols against Salmonella infection

| Disease | Animal | Particular features | Bacterium | Route of administration | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typhoid fever | Mouse | Nramp1−/− susceptible strains (acute infection) | S. Typhimurium, low to very low doses | Orogastric, parenteral | 35, 238 |

| Nramp1+/+ resistant strains (persistent infection) | S. Typhimurium, medium or high doses | Orogastric, parenteral | 35, 238 | ||

| Rag2−/− γ chain−/− + hematopoietic stem cells | S. Typhi, other serovars | i.p. | 135, 136, 239 | ||

| NOD-scid IL2R−/− + hematopoietic stem cells | S. Typhi, other serovars | i.p. | 135, 136, 239 | ||

| Rabbit | S. Paratyphi A, very high doses | Orogastric | 240 | ||

| Invasive NTS | Rabbit | S. Enteritidis | i.p. | 241 | |

| Gastroenteritis | Mouse | Streptomycin treatment, knockout mice | S. Typhimurium, other serovars | Orogastric | 177, 242, 243 |

| Calf | S. Typhimurium, S. Dublin, S. Newport | Orogastric | 244, 245, 246 | ||

| Rhesus macaques | S. Typhimurium | Orogastric | 247 |

Classically, mouse strains deficient in Nramp1 (iron transporter in endosomes), such as BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice, have been used as a model for typhoid fever. Indeed, infection with S. Typhimurium via the orogastric route leads to a systemic infection and is ultimately lethal in several days or up to 2 weeks, depending on the dose (134). New models rely on immunodeficient (severe combined immunodeficiency [SCID]) mice engrafted with human hematopoietic stem cells (hHSC). Depending on genetic modifications (Rag2−/− γc−/− or nonobese diabetic [NOD]-scid IL2Rγnull [NSG]), mice develop, respectively, either nonacute typhoid fever (135) or a human-like enteric fever after infection by S. Typhi (136). Persisting drawbacks of these reconstructed animal models reside in chronic perturbation of lymph node development (137), while the loss of function of the IL-2 receptor decreases the amount of human T cells in the mouse intestine (138). Further improvements will be required to reduce murine immune responses in favor of human immune responses after engraftment of hHSC (139). This has been accomplished by expression of human signal regulatory protein α in mice or the use of neutrophil cytosolic factor 1 mutant mice (140). A broader distribution of human immune cells in mouse tissues occurs following administration of human IL-3 and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). Along this line, a recent model of transgenic NSG mice expressing human stem cell factor, GM-CSF, and IL-3 allows generation of higher levels of antigen-specific IgM and IgG than in parent NSG mice (141).

Recent Developments in Human Vaccination

Studies on several engineered derivatives of existing vaccines have been carried out to improve the effectiveness and spectrum of action on one hand and to limit deleterious adverse effects, including bacterial reversion, toxicity, and reactogenicity, on the other hand (142). Advances in molecular biology have allowed the design of attenuated mutants preserving adequate immunogenicity while preventing persistent infection. In order to limit undesired reactogenicity, targeted attenuation can be performed with both virulent and metabolic genes (143, 144), resulting in mutations affecting functionality or through complete gene disruption. This has led to the development of several candidate vaccines orally administered and currently tested in phase 2 clinical trials, such as, for example, M01ZH09 (Ty2; aroC ssaV mutants), CVD909 (aroC aroD htrA mutants), and Ty800 (phoP phoQ mutants) (145, 146). All mutants are based on the parent Ty2 strain, with the CVD909 engineered in such a way that it constitutively expresses the Vi capsule, whose expression is otherwise lost in most live attenuated Salmonella mutants. CVD909 was shown to promote bacterial opsonophagocytosis thanks to IgG antibodies specific for S. Typhi O Ag in LPS (147). Furthermore, increases of IFN-γ-secreting CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells are found after oral administration of the attenuated CVD909 S. Typhi vaccine in humans (148).

Given the increasing prevalence of S. Paratyphi A-dependent illness, efforts have been dedicated to the development of the so-called SPADD01 (aroC yncD mutants) vaccine against this serovar (149, 150). After intranasal immunization, strong protection of mice against S. Paratyphi A, but not against control S. Typhi, is observed. The selected examples above argue for a real potential of live attenuated vaccines, as they provide both attenuation and biological containment in vivo but with a residual risk of reversion.

Due to its intrinsic nature, the existing pure polysaccharide Vi CPS vaccine triggers only T cell-independent immune responses and low-affinity antibodies. To overcome this limitation, several studies have been performed with a conjugate that combines the sugar unit with a carrier protein in order to ensure conversion of the Ag into a trigger for T cell-dependent immune reactivity. This has led to the identification of tetanus toxin (TT), diphtheria toxin (DT), the nontoxic recombinant form of DT (CRM197), the recombinant carrier protein exoprotein A (rEPA) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and the Streptococcus pneumoniae surface protein A (PspA) as valuable carriers. Successful clinical trials with the Vi rEPA vaccine, notably in young children (90% of patients were protected against S. Typhi), has resulted in its licensing in China (151). Similarly, Vi TT is already licensed in India. More recently, a phase 2 trial conducted on infants (6 to 8 weeks), children (<59 months), and adults with Vi CRM197 has shown much higher immunogenicity than Vi CPS, and Vi CRM197 appears to be safe (152). In addition to enabling a T cell response, conjugation of PspA with the Vi capsule has been reported to provide protection against both Salmonella and Streptococcus (153).

In conclusion, novel vaccine candidates based on evolution/engineering from existing vaccines are emerging thanks to the refined dissection of the mechanisms involved in bacterial pathogenesis and immunity to infection. Due to good efficacy, two recently developed vaccine formulations, namely, Vi rEPA and Vi TT, are already licensed, with many others still under evaluation in preclinical trials (146, 154). Of note, although most of the TS vaccines that are licensed or under development are based on the Vi capsule, only S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi B display this Ag. However, the fact that although S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi A differ in their overall genome, they carry 172 common genes leaves the door open to the identification of protective Ags covering a less restricted spectrum of serovars.

Vaccines Against NTS: Difficulties and Ongoing Efforts

Because of the lack of similarity between TS and NTS strains, the design of vaccines targeting NTS has not benefited from the knowledge acquired during the development of TS vaccines. In a seminal study, the auxotrophic aroA S. Typhimurium attenuated mutant was shown to protect mice against virulent S. Typhimurium (155) and S. Enteritidis (156). This mutant, by maintaining immunostimulation, has been shown in addition to serve as a powerful live vaccine carrier (157–159). However, the observation that administration of the aroA mutant to immunocompromised mice makes them severely sick has called into question its appropriateness and safety for human application (86, 160). This has made mandatory the de novo development of specific NTS multivalent vaccines, such as, for example, by evaluating alternative attenuated mutants from S. Typhimurium strains (161). Incorporation of phosphatase genes in the genome of S. Typhimurium reduces phosphorylation of lipid A, results in attenuation in mice, and increases sensitivity to bile (162), yet it preserves their capacity to induce adaptive immunity to Salmonella Ags after oral administration. Such mutants synthesizing the nonphosphorylated lipid A may be useful to develop Salmonella subunit vaccines, such as those based on Omps, outer membrane vesicles (Omvs), and heterologous polysaccharides (162). Moreover, a method relying on the arabinose-dependent PBAD promoter has been developed to progressively suppress genes involved in S. Typhimurium-induced disease symptoms (163). This results in decreased reactogenicity after administration of live Salmonella. For vaccine design, strains with this deficiency in essential virulence factors retain the same ability as WT Salmonella to colonize lymphoid tissues, a feature required to elicit efficient immune responses. Other attenuated strains, such as CVD1921 (S. Typhimurium guaBA clpP mutants) and CVD1941 (S. Enteritidis guaBA clpP mutants) have been tested in mice and show promising results, as exemplified by functional antibody responses protecting against challenge by virulent strains (164). Along the same line, immunization with the attenuated S. Enteritidis strain ΔXII, which is not able to synthesize the secondary messenger bis-(3-5)-cyclic dimeric GMP, induces antibody production and cytokine-secreting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells associated with protection against virulent S. Typhimurium (165). However, one of the drawbacks of attenuated mutants is that they do not trigger the same qualitative and quantitative immune response profile as the parent strain, requiring detailed evaluation of each vaccine candidate (166).

As mentioned above, the serovars differ from each other through the combination of the two H (flagellar) and O (somatic) Ags they display at the bacterial surface. Thus, a second approach would consist of designing vaccines based on such Ags in order to specifically protect against a particular serovar. Immunization with attenuated S. Typhimurium BRD509 simultaneously expressing FliC and FljB H Ags enhances NF-κB-dependent activation of cytokine production and confers protection against a lethal challenge with virulent strain SL1344 in mice (167). However, differential expression of FljB and FliC (flagellar phase variation) occurs during Salmonella infection, further complicating the recognition of H Ags by the immune system (168). In contrast, the O Ag continuously present on LPS makes it a candidate for inclusion in a vaccine. As discussed above, because the O Ag generates only a T cell-independent antibody response, coupling to a carrier protein is required to provide optimal protection against S. Typhimurium (169). Mouse immunization with the S. Typhimurium O Ag-CRM197 glycoconjugate vaccine induces O:4-specific antibodies (IgG, IgA isotypes) exerting protective functions in in vitro and in vivo assays (170). Fusion of H Ags with O Ags of S. Enteritidis induces a IgG response and protection against S. Enteritidis (171, 172). Polysaccharide O:2 Ag from S. Paratyphi A coupled with the CRM197 protein yielded immunogenic conjugates with strong serum bactericidal activity (173). However, the high diversity of these proteins between Salmonella strains, as reflected by the fact that they are used in the strain-related classification of the bacteria (42), remains a drawback for the design of a multivalent vaccine. Thus, even though such Ags trigger an adaptive immune response when coupled with other proteins, their low degree of conservation between the different serovars decreases their relevance as potent vaccine candidates.

Vaccination against NTS is focused mainly on S. Typhimurium, and even if some studies yield promising results, no vaccine is in a late trial phase to date (146). However, other strains, such as S. Enteritidis or strains from the serogroups O:6,7,8 (the major gastroenteritis-causing group in the United States), would deserve more attention for human vaccine development (11). Another parameter to integrate, the nature of the adjuvant in a vaccine formulation, is almost as important as the Ag. In this respect, mice infected with the S. Typhimurium MC1 virulent strain expressing the S. Typhi typhoid toxin unexpectedly exhibit better survival and reduced inflammatory intestinal responses, resulting in long-term persistence in asymptomatic carriers compared to mice infected with the parent WT strain (174). This suggests that adjuvantization of NTS vaccines with the typhoid toxin produced by S. Typhi may be considered in vaccine formulations targeting different serovars of Salmonella (175).

Animal Models To Address Vaccine Design against Human NTS

Even though a broad range of species can be infected by NTS strains, only a few can serve as relevant animal models for human gastroenteritis (133) (Table 1). The streptomycin-pretreated mouse model serving as a surrogate of Salmonella-induced colitis in humans, when tested with S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis serovars, proved to be a valuable tool for evaluating virulence factors involved in enteropathogenesis (176). The model was also valid to assess S. Typhimurium attenuated mutant strains as potential live vaccines (177). In the search for new animal models recapitulating infection in human, cattle are also considered a pertinent counterpart for nontyphoidal salmonellosis (178), as the same symptoms as for foodborne gastroenteritis in patients are induced (179).

Moreover, as natural NTS infection induces illness in rearing animals, these animals can be considered not only as research models but also as vaccination targets in order to increase yields of production and to indirectly impede human contamination. For similar reasons, pigs are also an interesting species for the development of a vaccine against Salmonella (180). For example, parenteral administration of the attenuated S. Typhimurium strain ΔznuABC protects pigs (181). The close relationship between the intestinal immune systems in pigs and humans suggests that results obtained in either organism can be transferred to the other. In poultry, a vaccine composed of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium SPI-1 mutants cross-protects against the two strains (182) and when a low-dose challenge is administered after oral immunization (183). The S. Enteritidis-based attenuated vaccine JOL919 provides protection early in development by preventing egg contamination (184) via the presence of higher antibody and T cell responses in orally infected chickens.

SALMONELLA ANTIGENS AND THEIR USE IN VACCINE FORMULATIONS

In order to mediate neutralization or elimination of pathogens by opsonization or via the classical complement pathway, targeted Ags must be specifically recognized by antibodies. This is a valid approach when dealing with extracellular pathogens. However, in the case of intracellular pathogens, such as Salmonella, this strategy will be partially impaired by the presence of the bacteria mostly within host cells during infection. The microorganism should be recognized by antibodies, e.g., in the gut lumen, to prevent pathogen entry and should be presented by infected cells to promote T cell-mediated elimination. Although precise criteria for the selection of candidate Ags to be included in anti-Salmonella vaccines have to be carefully defined, some key parameters have emerged experimentally (185). Among the many Ags expressed in infected host tissues, surface-associated or secreted ones displaying high levels of expression should be favored. In addition, in order to broaden the vaccine coverage, focusing on Ags conserved between serovars would be an asset. However, one has to keep in mind that the context-dependent expression of different Salmonella Ags during infection is an additional crucial issue to consider. As mentioned above, the FljB and FliC flagellar components are only transiently expressed early during infection (168, 186). Possibly, the presence of the Vi capsule in S. Typhi may also impair the proper recognition of some Ags by covering the cell surface of the bacterium. Temporal mutations observed in the genome of a particular serovar and intrinsic differences between serovars may further complicate the development of a multivalent vaccine (187, 188).

Some Ags may have intrinsic adverse effects on immunity which impede their use as a vaccine. Salmonella has been shown to alter immunity through multiple processes: (i) the SptP protein blocks Syk activation in mast cells, leading to suppressed degranulation of local mast cells and resulting in poor neutrophil recruitment at the site of infection (189); (ii) SseI inhibits migration of DCs and thus decreases Ag presentation at sites of immune induction (190); (iii) l-asparaginase II (191) and Vi capsule (130) suppress T cell early activation signaling pathways and effector functions; (iv) TviA protein decreases flagellin expression (192) and therefore specific recognition by CD4+ T cells; and (v) overexpression of the inhibitory molecule PD-1 interferes with the elimination of infected APCs by cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (193). Moreover, Salmonella effector proteins expressed by SPI-2 can alter both T cell and B cell responses (194).

In order to induce robust protective immune responses as this occurs during a natural infection, and in particular when an antibody-mediated effect is required, it makes sense to hypothesize that antigenic structures displayed on the surface of pathogens are the most appropriate candidates for vaccine engineering. In a recently published study, as many as 37 Salmonella Ags have been examined in a mouse typhoid fever model for their intrinsic capacity to trigger specific immune responses and provide protection. Remarkably, all immunogenic and protective Ags turned out to be surface exposed (195). Along the same line, screening of S. Typhimurium Ags able to be presented by mouse DCs suggests additional candidates for a vaccine (196). Specific recognition of several Salmonella-derived recombinant proteins by IgG from infected patients has allowed the identification of a panel of relevant surface Ags (197, 198). Many of them demonstrate some degree of protection in a mouse model of infection (185). Such a feature suggests that interspecies validation for Ag identification represents a plausible approach that should not be overlooked (Table 2). Further investigation may identify one or more secreted Ags capable of inducing a different or more efficient protective immune response. To support this point, subcutaneous (s.c.) immunization of mice with supernatant isolated from S. Typhimurium adjuvanted with TiterMax Gold adjuvant increases survival after Salmonella infection in comparison with that for phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-immunized mice (199). This is associated with a decrease of the bacterial load in spleen and liver and a Salmonella-specific IgA/IgG response. Deciphering the nature of other unknown proteins in culture supernatant is another valid way to increase the number and the diversity of efficient Salmonella Ags.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Salmonella antigens used in vaccination studies

| Ag | Type of molecule (mass, kDa) | Function | Administration | Protection | Immune response(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SseB | Protein from EspA superfamily (21.5), encoded by Salmonella pathogenic island 2 and weakly bound to the bacterial cell surface | Constituent of T3SS | Footpad injection of rSseB or SseB peptides + TiterMax Gold adjuvant (HLA-DR transgenic murine model) | Not tested | CD4+ T cell-dependent IFN-γ response for SseB and peptides | 203 |

| Culture of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy donors or exposed donors with 104 CFU of S. Typhi (human ex vivo model) | Not tested | CD4+ T cell-dependent IFN-γ response for SseB | 203 | |||

| i.v. injection of rSseB and LPS with or without alum and oral Salmonella challenge (murine model) | Decrease of bacterial burden in spleen and liver and increase of survival | IgG and IgM secretion | 198 | |||

| s.c. injection of rSseB in complete Freund's adjuvant and oral Salmonella challenge (murine model) | Increase of mouse survival | SseB-specific IgG secretion | 195 | |||

| SseI | Effector protein (36.8), also called SrfH, translocated by T3SS in host cytoplasm | Inhibits migration of primary macrophages/DCs | s.c. injection of peptide SseI268–280 with complete Freund's adjuvant (murine model) | Decrease of bacterial burden in spleen and liver and increase of survival | No IgM or IgG secretion; Th1 response (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2) | 87, 190 |

| OmpA | Outer membrane protein (35.5) | Constituent of porin | Culture of murine DCs with rOmpA and coculture or not with CD4+ T cells (in vitro model) | Not tested | DC activation (IL-12) by TLR; polarization toward Th1 response (IFN-γ) | 248 |

| OmpC | Outer membrane protein (39.2) | Constituent of porin | i.p. injection of protein purified from WT S. Typhi (murine model) | Bactericidal complement-mediated effect | Long-term persistence of IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b and IgG3 antibodies | 249 |

| i.p. injection of protein purified from WT S. Typhi (murine model); s.c. vaccinated with porins (humans) | Not tested | Sustained IgG and IgM antibodies, CD4+ T cell (IFN-γ) responses in mice; long-lasting IgM response in humans | 85 | |||

| i.p. injection of protein purified from WT S. Typhi (murine model) | Not tested | B cell/DC activation. IgG1, IgG2b/c, IgG3, and IgM secretion | 250 | |||

| OmpD | Outer membrane protein (37.6) | Constituent of porin | i.p. injection of porins purified from WT S. Typhimurium or S. Typhi (murine model) | Decrease of burden in blood, spleen, and liver | Specific IgM responses against porins and OmpD; B1b cell activation | 92 |

| OmpF | Outer membrane protein (37.8) | Constituent of porin | i.p. injection of protein purified from WT S. Typhi (murine model) | Bactericidal complement-mediated effect | Long-term persistence of IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 antibodies | 249 |

| i.p. injection of protein purified from WT S. Typhi (murine model); s.c. vaccinated with porins (humans) | Not tested | Sustained IgG and IgM antibodies, CD4+ T cell (IFN-γ) responses in mice; long-lasting IgM response in humans | 85 | |||

| i.p. injection of protein purified from WT S. Typhi (murine model) | Not tested | B cell/DC activation; IgG1, IgG2b/c, IgG3, and IgM secretion | 250 | |||

| OmpL | Outer membrane protein (25) | Constituent of porin | i.p. injection of recombinant OmpL with complete Freund's adjuvant (murine model) | Decrease of bacterial burden in spleen and liver and increase of mouse survival; bactericidal effect against S. Typhimurium, S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi | Serum TNF-α and specific IgG and IgA secretion | 251 |

| SopB | Effector protein (62), translocated by T3SS into host cytoplasm | Differentiation of epithelial cells into M cells to promote Salmonella invasion | i.p. injection of attenuated S. Typhimurium followed by recombinant truncated SopB coupled with nanoparticle (murine model) | Decrease of bacterial burden in MLNs, liver, and spleen | CD4+ T cell proliferation and secretion of IFN-γ and IL-2 | 51, 252 |

Specifically, SseB and different Omp family members have been described as potential vaccine candidates in mice (200–202). SseB is also immunogenic in humans; indeed, SseB-specific CD4+ T cells producing IFN-γ are detected in the circulation of asymptomatic individuals or people previously exposed to S. Typhi (203). Interestingly, Omps and SseB are highly conserved among strains and could be used in vaccines covering a large array of Salmonella infections. S. Typhimurium-derived Omvs containing LPS and Omps known to serve as adjuvant are able to induce cross-protection against S. Choleraesuis and S. Enteritidis challenge (204, 205). In the search of a multiprotective Ag, nasal immunization of mice with the enterobactin (a siderophore involved in iron acquisition by the bacteria and fungi) of Salmonella coupled with the immunogenic carrier protein cholera toxin subunit B induced a decrease of systemic invasion together with an increase of specific IgA (206).

Hitherto poorly explored avenues deserve consideration for future developments: (i) precise determination of the immune signature induced by an Ag is a key step in vaccine formulation, as exemplified by the observation that among two promising candidates such as SseI and FliC, only SseI induced a Th1-dependent protection in mice after s.c. immunization (87); (ii) because it is rather uncommon that a comprehensive coverage of the panel of immune responses (inflammatory cytokines, antibodies, and T cells) is provided in work dealing with the protective effect of vaccine formulations, efforts at homogenizing readouts will be warranted; and (iii) studies that examine candidate Ags in different models and under different experimental conditions (schedule, doses, adjuvants, and Salmonella strains) (85, 92) preclude comparison of efficacy between vaccination protocols (Table 2). In addition to the drawbacks described above, the potential toxicity of bacterial Ag proteins prevents their use as such and requires that they are prepared as recombinant truncated derivatives possibly lacking crucial epitopes. Moreover, systemic immunization, performed in the vast majority of protocols, may not be the best route for assessing the mucosal contribution of a vaccine candidate supposed to target Salmonella infecting along the oral route.

Given the complex nature of the immune response that needs to be elicited to clear Salmonella infection, the challenging issue is to select the most adapted Ag, or a combination thereof, for incorporation in the vaccine formulation. Immunogenicity (i.e., breadth and persistence of induced immunity) has to be boosted to achieve the induction of the most relevant immune response profile and at the same time to reduce excessive reactogenicity. In this context, a combination of the most appropriate Ags (195, 198) and vaccine vectors must be thoroughly evaluated. The strategy for vaccine design must ideally include the selective delivery to sites of induction ensuring local immune responses, i.e., GALT in the case of enteropathogen-triggered infection.

DELIVERY VEHICLES FOR MUCOSAL VACCINATION

In addition to being relatively easy to administer, mucosal vaccines allow the elicitation, in most instances, of both a local mucosal and a more disseminated systemic immune response via a mechanism referred to as the common mucosal immune system (207–209). This is of interest for Salmonella since the bacterium initially infects the intestinal mucosa and, when not restrained, propagates and persists in the systemic environment. This implies that a vaccine stimulating the protective mechanisms of the mucosal compartment would be highly relevant, as it is expected to block the infectious agent at its site of entry (210). Moreover, through the extensive knowledge acquired on the cellular and molecular players involved in GI immunity, evaluation of the adequacy of the induced immune response is facilitated. However, to prove efficacious, oral vaccination requires that several hurdles are overcome, including (i) intrinsic weak Ag stability in the protease-rich gut environment, (ii) dilution and dispersal along the large surface area of the gut, (iii) the need for an appropriate dose of Ag to induce protective immune responses and not tolerance, (iv) crossing of the mucus layer, and (v) the possible cytotoxicity of the Ag. While these constraining features have favored the development of formulations for systemic administration, recent studies provide strong arguments to envisage the design of more efficient delivery solutions to facilitate the development of improved mucosal vaccines for infectious enteric diseases. Examples of Ag delivery strategies currently under development are depicted in Fig. 2.

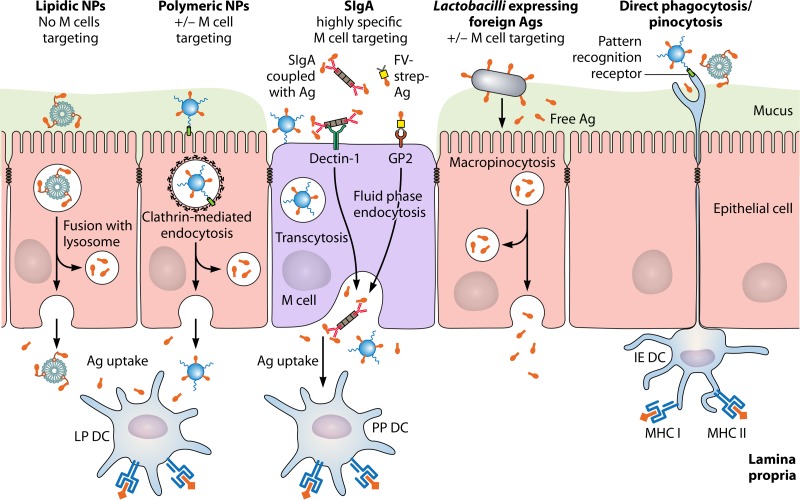

FIG 2.

Vaccine delivery systems for oral administration of antigens in the gut. Carriers are able to target epithelial cells, microfold (M) cells, and intraepithelial dendritic cells (DCs) specialized in sampling of particulate formulations. The underlying uptake mechanisms include phagocytosis, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, fluid-phase endocytosis, and macropinocytosis. Transport of the intact or partially degraded formulations across the epithelial layer via M cells or enterocytes results in capture and processing by DCs in the mucosal environment. Depending on the delivery system, the antigen may be released in the lamina propria as a free species or in association with the vector. Information regarding maturation of Ag-presenting cells, T cell activation, systemic and mucosal antibody production, and cytokine secretion, as well as additional examples (not shown to avoid encumbering the figure), are provided in the text. Abbreviations: IE DC, intraepithelial dendritic cell; LP DC, DC located in the lamina propria; PP DC, DC located in the subepithelial dome region of Peyer's patches; Ag, antigen; NP, nanoparticles; MHC I and II, major histocompatibility complex molecules I and II. The figure is not drawn to scale.

A major site for eliciting gut immune responses directed against Salmonella is PPs in the small intestine. However, the presence of digestive enzymes and acidic conditions in the GI tract may affect the integrity of the Ag and prevent optimal detection by the immune system. Stability issues can be overcome by preparing derivatives via Ag glycosylation (211) or lipidation of immunogenic peptides (212). Limited degradation of the cholera toxin B subunit expressed in rice seeds ensures its proper uptake by M cells and the onset of specific systemic IgG and mucosal IgA antibodies (213). Spores of Lycopodium clavatum using a “natural” Ag-containing envelope have been shown to maintain ovalbumin integrity and to trigger a specific mucosal immune response characterized by secretion of both IgG and IgA (214). Successful engineering of spherical nanoparticles (NPs) able to transport and compartmentalize the encapsulated Ag at different sites in the small and large intestine has also been reported (215). Intranasal immunization of mice with SseB linked to gas-filled lipid microbubbles induces specific mucosal and systemic antibody and T cell responses associated with reduced infection upon oral challenge by S. Typhimurium (216). As only small doses of the SseB Ag are given along the nasal route, it is expected that oral administration will be operational as well. Oral administration of an antimicrobial peptide encapsulated in NPs also increases both bacterial killing in the liver and the intestine and mouse survival after S. Typhimurium infection, compared to the peptide given alone (217). In light of the identification of protective Ags, one can anticipate that similar stabilization and efficacious delivery systems are worth testing as novel vaccine tools targeting Salmonella.

GALT immune responses are elicited with the aim to discriminate between harmless and noxious Ags, triggering either tolerance or protective immunity. As a function of its nature, it happens that oral administration of a pathogen-derived Ag as such can induce a tolerogenic response only. To compensate for this drawback in a vaccination process, the solution consists of adding an adjuvant-linked danger signal to the vaccine formulation. Incorporation of killed/inactivated whole cells, proteins, peptides, or DNA has been successfully accomplished, yet features such as loading efficiency, pH sensitivity, and cell targeting are in need of improvement. A number of systems, including micro- and nanoparticles, lipid-based strategies, and enteric capsules, have significant potential either alone or in advanced combined formulations to enhance intestinal immune responses (218). For example, mucosal delivery of charge-switching synthetic NPs containing encapsulated monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA) and coated with inactivated Chlamydia trachomatis leads to a specific protective and long-lasting Th1 response in mice (219). Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and poly(lactic-coglycolic acid) (PLGA) particles are NPs which can be engineered to either display the Ag at the surface of the polymer or encapsulate the Ag and the adjuvant in the inside of the matrix (220). Encapsulation of NOD-1 and NOD-2 ligands, followed by adsorption of the HIV-1 p24 gag protein in PLA NPs, yields a vaccine formulation able to induce human monocyte-derived DC activation and T cell proliferation in vitro and a p24-specific mucosal and systemic IgA and IgG secretion after oral mouse immunization (221). In the context of S. Typhi Omps, encapsulation in PLGA beads increases specific B cell responses in PPs and MLNs of orally immunized mice compared to Omps alone, suggesting the versatility of this delivery system (222). Outside chemically based delivery systems, viral and bacterial Ags expressed in safe natural carriers such as probiotic strains generate specific local and systemic protective immunity observed in case of S. Typhimurium infection in mice when fed orally (223–226). Another manner to contribute to the good delivery of Ags in the intestinal mucosa would consist of orally coadministering the vaccine formulation with the protease inhibitor U-Omp19 from Brucella, which has been shown both to increase the half-life of Ags delivered along the GI tract and to activate APCs (227). Recently, NPs have been formulated to overcome the challenging environment encountered along the oral route of administration; such a formulation called single multiple pill (SmPill) combines whole-cell killed Escherichia coli overexpressing the colonization factor Ag I in a dispersed phase, α-galactosylceramide as an adjuvant, and a polymer coating preventing gastric degradation (228). Specific mucosal IgA and systemic IgG responses are obtained, yet protection against E. coli was not assessed. It is important to note that even if NPs display many features of valuable carriers, side effects, including dysbiosis or allergies (229), have been occasionally observed after delivery in the gut environment.

As mentioned above, targeting of PPs is essential both to induce an efficient mucosal immune response and to decrease the amount of Ag to be delivered. In this respect, investigation of M cells via recently identified specific receptors is of high interest, as the vaccine vector can be designed to combine properties of a potent ligand and a shield for the antigenic structure. For example, mouse oral immunization with Salmonella-derived proteins hooked to an anti-GP2 monoclonal antibody (230) induced specific fecal SIgA secretion and associated protection against Salmonella without the need for an adjuvant. The high stability of SIgA molecules in the gut, their propensity to reverse transcytosis across M cells via the dectin-1 receptor (114), and the a priori nonrequirement of adjuvantization to mount immune responses against the bound Ag (231) mark the antibody as a potentially valuable protein carrier in the mucosal context. In a similar approach, a preparation of HIV p24gag covalently bound to SIgA, when administered orally together or not with heat-labile enterotoxin, exhibited p24-specific mucosal and systemic immune responses resulting in mouse protection after rectal challenge with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the gag protein (232). The same vaccine formulation used for mouse nasal immunization allowed similar induction of protective immunity against mucosal challenge by the p24-expressing vaccinia virus (233). Because intestinal specific IgA responses appear to decrease with the age of an individual, yet this does not occur in nasopharyngeally associated lymphoid tissue (234), both routes of mucosal administration deserve to be evaluated as a function of the foreseen sustained protection. Although not systematically implementable in humans, but remaining of high value in the veterinary field, novel mucosa-targeting immunization methods deserve further attention. For example, pretreatment of mice with RANKL (receptor activator of NF-κB ligand), which has been shown to increase the proportion of GP2+ M cells in PPs and thus transcytosis of microparticulated Ags, increases both serum Ag-specific IgG and fecal Ag-specific IgA in comparison with those in naive animals (235).

Thus, oral (and more generally mucosal) vaccination remains a current challenge, which is in need of further developments based on numerous promising results, most obtained in animal studies and thus requiring further evaluation in humans. In addition to resolving important safety issues, the strategy of targeting mucosal surfaces represents the most optimal approach to fulfill the essential requirement that both mucosal and systemic immune protection can be achieved and thus to ensure that invasive bacteria are neutralized at their site of entry and later on if they have breached the mucosal barrier (218). Once essential aspects, including the stability of the Ag, the adjuvantization, and mucosal targeting, are guaranteed, it is not exaggerating to envisage that the oral route of administration will offer results at least similar to, if not better than, those of the systemic mode of administration for vaccine preparations targeting enteropathogens. The various novel and promising approaches described above all deserve to be addressed in the context of Salmonella vaccination studies to eventually permit delivery of a vaccine to the at-risk population, i.e., young infants.

CONCLUSION

The main strains of Salmonella infect a broad range of animal hosts, inducing a high morbidity and mortality, especially in young human children after ingestion of contaminated food. The emergence of MDR strains requires definition of a vaccine strategy against the broader possible range of Salmonella strains. However, this species is a complex intracellular pathogen exquisitely adapted to its host, in particular to the intestinal epithelium. It is well established that Salmonella successfully crosses the mucosal barrier through M cells and uses the GALT immune pathway to infect the host. Although a relatively efficient immune response is triggered after Salmonella recognition, the organisms spread and persist in the host via multiple escape mechanisms. The understanding of immune responses against Salmonella species will allow the selection of appropriate Ags and adjuvants, with the aim to induce protective Th1 T cell responses and to promote specific B cell activation in both the mucosal and systemic compartments. The establishment of a memory T and B cell immune response is another requirement to validate the relevance of any vaccine candidate. However, in addition to the unsolved issue that neither animal models nor administration methods are standardized, a vaccine targeting the main serovars remains a technical challenge, mostly because multiple antigenic structures/subunits will likely have to be assembled within the same formulation. In this context, we propose that engineering a mucosal vaccine combining functional cargo carriers (SIgA or micro- or nanoparticles) and Salmonella Ags identified as protective in animal models and immunogenic after infection in humans represents a sound development for the future. Such a strategy will permit production of a vaccine with adequate stability in the aggressive environment of the intestinal tract and the ability to bind M cells to favor induction of the most effective immune responses. The combination with other treatments, including passive delivery of specific monoclonal antibodies (236), DNA vaccination (237) or recombinant probiotic delivery, may turn out to eventually define the optimal system to fight the still-devastating consequences of Salmonella infection worldwide.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The laboratory of B. Corthésy is supported by grant no. 3100-156806 from the Swiss Science Research Foundation. The laboratory of S. Paul is supported by grants from Pfizer, the French National Research Agency, the Jean Monnet University and the Rhône-Alpes region.

Owing to the extent of the topic, the contributions of many colleagues in the field are not, or are only partially, covered; we are aware of this and apologize to colleagues to whom credit could not be given through this review.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patrick ADG, Rimont F-XW. 2007. Antigenic formulae of the Salmonella serovars, 9th ed WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella, Institut Pasteur Paris, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaffga NH, Barton Behravesh C, Ettestad PJ, Smelser CB, Rhorer AR, Cronquist AB, Comstock NA, Bidol SA, Patel NJ, Gerner-Smidt P, Keene WE, Gomez TM, Hopkins BA, Sotir MJ, Angulo FJ. 2012. Outbreak of salmonellosis linked to live poultry from a mail-order hatchery. N Engl J Med 366:2065–2073. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavallaro E, Date K, Medus C, Meyer S, Miller B, Kim C, Nowicki S, Cosgrove S, Sweat D, Phan Q, Flint J, Daly ER, Adams J, Hyytia-Trees E, Gerner-Smidt P, Hoekstra RM, Schwensohn C, Langer A, Sodha SV, Rogers MC, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Williams IT, Behravesh CB, Salmonella Typhimurium Outbreak Investigation Team. 2011. Salmonella Typhimurium infections associated with peanut products. N Engl J Med 365:601–610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darton TC, Blohmke CJ, Pollard AJ. 2014. Typhoid epidemiology, diagnostics and the human challenge model. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 30:7–17. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mogasale V, Maskery B, Ochiai RL, Lee JS, Mogasale VV, Ramani E, Kim YE, Park JK, Wierzba TF. 2014. Burden of typhoid fever in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic, literature-based update with risk-factor adjustment. Lancet Glob Health 2:e570–e580. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70301-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phu Huong Lan N, Le Thi Phuong T, Nguyen Huu H, Thuy L, Mather AE, Park SE, Marks F, Thwaites GE, Van Vinh Chau N, Thompson CN, Baker S. 2016. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in Asia: clinical observations, disease outcome and dominant serovars from an infectious disease hospital in Vietnam. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10:e0004857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morpeth SC, Ramadhani HO, Crump JA. 2009. Invasive non-Typhi Salmonella disease in Africa. Clin Infect Dis 49:606–611. doi: 10.1086/603553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, Heyderman RS, Gordon MA. 2012. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet 379:2489–2499. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]