Significance

In the midst of rapid globalization, the peaceful coexistence of cultures requires a deeper understanding of the forces that compel prosocial behavior and thwart xenophobia. Yet, the conditions promoting such outgroup-directed altruism have not been determined. Here we report the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled experiment showing that enhanced activity of the oxytocin system paired with charitable social cues can help counter the effects of xenophobia by fostering altruism toward refugees. These findings suggest that the combination of oxytocin and peer-derived altruistic norms reduces outgroup rejection even in the most selfish and xenophobic individuals, and thereby would be expected to increase the ease by which people adapt to rapidly changing social ecosystems.

Keywords: altruism, ingroup, outgroup, oxytocin, refugees

Abstract

Never before have individuals had to adapt to social environments defined by such magnitudes of ethnic diversity and cultural differentiation. However, neurobiological evidence informing about strategies to reduce xenophobic sentiment and foster altruistic cooperation with outsiders is scarce. In a series of experiments settled in the context of the current refugee crisis, we tested the propensity of 183 Caucasian participants to make donations to people in need, half of whom were refugees (outgroup) and half of whom were natives (ingroup). Participants scoring low on xenophobic attitudes exhibited an altruistic preference for the outgroup, which further increased after nasal delivery of the neuropeptide oxytocin. In contrast, participants with higher levels of xenophobia generally failed to exhibit enhanced altruism toward the outgroup. This tendency was only countered by pairing oxytocin with peer-derived altruistic norms, resulting in a 74% increase in refugee-directed donations. Collectively, these findings reveal the underlying sociobiological conditions associated with outgroup-directed altruism by showing that charitable social cues co-occurring with enhanced activity of the oxytocin system reduce the effects of xenophobia by facilitating prosocial behavior toward refugees.

At this time, we are witnessing one of the largest movements of refugees since the end of World War II (1, 2). Ongoing conflicts, persecution, and poverty in the Middle East and Africa have continued forced displacement of more than 65 million people since 2015 (2). Accommodating the large influx of migrants not only challenges the humanitarian capacities of European countries but also requires their native populations to adjust to rapid growths in ethnic diversity, religious pluralism, and cultural differentiation. However, the impetus to adapt to changing social ecosystems is susceptible to considerable interindividual heterogeneity (3). Resistance to this transition often goes along with xenophobic sentiment (4), and as a consequence, recent elections in Europe have favored populist candidates who have openly expressed xenophobic attitudes toward refugees (5). However, at the same time, volunteer work for migrants in the hosting countries has reached all-time highs and is estimated to exceed 1.6 million hours per month in Germany alone (6). In the face of growing tensions over differences in ethnicity, religion, and culture (3), there is an urgent need for devising strategies for helping foster the social integration of refugees into Caucasian societies.

As a result of evolutionary selective processes, humans possess a genuine propensity to contrast ingroup members (“us”) from outgroup members (“them”) (3). This dichotomy is adaptive, as ingroup members could not have survived and reproduced without altruistic cooperation [i.e., the goodwill and reciprocity of other ingroup members (7, 8)]. Only recently has neuroscience begun to dissect the biological components of altruistic cooperation and identified oxytocin (OXT), an evolutionarily conserved peptide signaling pathway originating in the mammalian hypothalamus (9), to be a key modulator (10). These insights could be gained because intranasally administered OXT (OXTIN) penetrates the brain (11–13) and alters measures of neural and behavioral response (14). Specifically, OXTIN has been revealed to enhance social cooperation (15), generosity (16), and empathy (17, 18); to induce an altruistic response bias away from nonsocial toward social priorities (19); and to reinforce parochial preferences for outgroup hostility and ingroup centricity (20, 21). Consistent with the latter are findings from field studies of wild chimpanzees showing that heightened endogenous release of OXT correlates with greater ingroup cohesion during intergroup conflict (22). Furthermore, OXTIN facilitates social norm conformity (23–25). Social norms, and personally costly sanctions against defectors of these norms, an inclination defined as altruistic punishment, may have evolved to protect ingroup biases from erosion through selfish motives (26–29).

The biblical parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–16:17) describes an ethical maxim of helping strangers who have fallen in need. As such, it not only captures the essence of altruistic behavior by emphasizing the personal costs of selflessness toward others but also represents a formidable example that norm-enforced altruistic cooperation is by no means limited to the ingroup, but can even extend to outgroup members in ways neither precisely understood nor systematically researched. Here, we hypothesize that normative incentives co-occurring with enhanced activity of the OXT system exert a motivational force for inducing altruism toward strangers even in the most selfish and xenophobic individuals. To specifically test this hypothesis, the present study was devised to examine social norms, administered in the presence vs. absence of a norm-enforcing treatment with OXTIN, for their efficacy to promote altruistic responses in subjects scoring high on a xenophobia inventory (Xi).

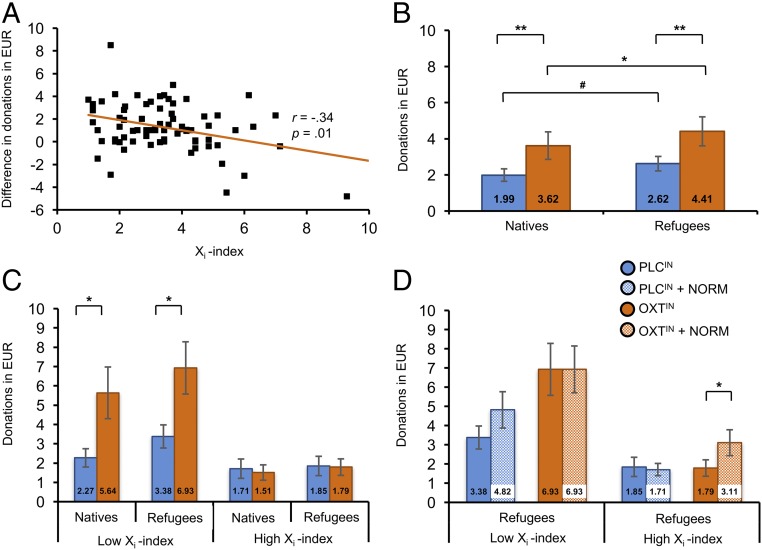

Experiment 1

To this end, the rationale of Experiment 1 was to generate normative cues for altruistic responding toward refugees, on the basis of an incentivized donation task framed in the context of Europe’s refugee crisis (Materials and Methods). This paradigm was composed of 50 authentic case vignettes briefly describing the personal needs of poor people, half of which were portrayed as refugees (outgroup) and half as natives (ingroup), respectively. The personal needs comprised those elements the United Nations has defined as minimum standards for leading a safe and dignified life (30); that is, access to food, adequate housing, or participation in social and cultural life (31, 32). Assignment of cases to ingroup vs. outgroup frames was balanced across participants to rule out systematic bias. Subjects were endowed with EUR 50 and could donate a maximum of EUR 1 to each case, leaving them the rest (EUR 0–50) as personal payoff. Before testing, subjects’ prejudicial attitudes toward refugees was assessed by measuring their individual Xi index (33) (Materials and Methods). In Experiment 1, a total of 76 healthy female (n = 53) and male (n = 23) undergraduate students (mean age ± SD, 21.2 ± 3.0 y) completed the donation task. For the purpose of generating an altruistic norm, subjects were assembled in a lecture hall, enabling reputation pressures to prompt potential donors to respond more generously. Indeed, results show that participants contributed more than 30% of their endowment. Interestingly, the donations devoted to refugees were 19% higher (EUR 8.03 ± 6.74) than those to natives [EUR 6.71 ± 6.86; t(75) = 5.35; P < 0.01; d = 0.19]. This bias indicates an altruistic preference for the outgroup and was lowest in Xi high scorers (r = −0.34; P < 0.01) (Fig. 1A). An additional analysis including gender as a between-subject variable showed that neither the donations to natives and refugees nor the outgroup bias (donations to refugees minus donations to natives) was influenced by gender (all P ≥ 0.86).

Fig. 1.

The sociobiological conditions that reduce the effects of xenophobia by facilitating prosocial behavior toward refugees. (A) In Experiment 1 (n = 76), altruistic donations for the outgroup were lowest in those scoring high on the Xi index (scores ranging from 1 = low to 10 = high). (B) In Experiment 2, an independent sample of 107 male participants received OXTIN (n = 51) or placebo (n = 56) before the donation task. OXTIN promoted a 68% (outgroup) and an 81% (ingroup) increase in the donated sums. (C) Based on the subjects’ Xi scores from the 7-item scale of the realistic threat inventory, the sample was median-dichotomized (n = 54 Xi low scorers; n = 53 Xi high scorers). Xi low scorers who received OXTIN (n = 26) more than doubled their donations to both groups, whereas the peptide did not induce generosity in Xi high scorers (n = 25). (D) Pairing OXTIN with peer-derived norms in Experiment 3 prompted Xi high scorers to increase their outgroup-related donations by 74%. OXTIN + Norm, intranasal oxytocin paired with a peer-derived norm; PLCIN + Norm, intranasal placebo paired with a peer-derived norm. Error bars indicate the SEM. #P = 0.056; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Experiments 2 and 3

Experiments 2 and 3 were carried out within the same randomized controlled trial and involved an independent sample of 107 male participants (mean age ± SD, 24.1 ± 3.2 y). Before testing, their prejudicial attitudes toward refugees were measured by the Xi index (33). Subjects self-administered a 24-IU dose of OXTIN or placebo (PLCIN), which was instructed and supervised by a blinded experimenter in accordance with the latest standardization guidelines (34). Subsequently, subjects were placed alone in separate test cubicles and tested on the donation task established in Experiment 1 (Fig. S1). Based on the subjects’ Xi index, the sample was median-dichotomized, resulting in n = 53 Xi high scorers and n = 54 Xi low scorers. A repeated-measures analysis of variance with the between-subjects factors treatment (OXTIN, PLCIN) and Xi index (low, high), the within-subjects variable “frame” (ingroup, outgroup) and the donated sums as a dependent variable yielded main effects of treatment [F(1,103) = 4.64; P = 0.03; η2 = 0.04], Xi index [F(1,103) = 13.51; P < 0.01; η2 = 0.12], and frame [F(1,103) = 24.70; P < 0.01; η2 = 0.19]. Specifically, OXTIN promoted generosity toward both the outgroup [OXTIN, EUR 4.41 ± 5.73; PLCIN, EUR 2.62 ± 3.00; t(73.90) = 2.00; P = 0.05; d = 0.40] and the ingroup [OXTIN, EUR 3.62 ± 5.44; PLCIN, EUR 1.99 ± 2.58; t(69.88) = 1.94; P = 0.06; d = 0.39], evident in a 68% (outgroup) and an 81% (ingroup) increase in the donated sums (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, we detected an interaction of frame and Xi index [F(1,103) = 12.15; P < 0.01; η2 = 0.11]; that is, irrespective of OXTIN treatment, Xi low scorers’ contributions were 31% larger for the outgroup than for the ingroup [t(53) = 4.99; P < 0.01; d = 0.22], which replicates the outgroup favoritism observed in Experiment 1. As expected, this outgroup bias was absent in Xi high scorers, whose donations were not significantly different between the two frames [ingroup, outgroup; t(52) = 1.43; P = 0.16; d = 0.09]. An additional interaction of treatment and Xi index [F(1,103) = 5.43; P = 0.02; η2 = 0.05] reflects the inefficacy of OXTIN treatment alone to induce generosity in Xi high scorers (all P values > 0.75), whereas the peptide more than doubled the contributions of Xi low scorers to both the outgroup [t(34.52) = 2.40; P = 0.02; d = 0.68] and the ingroup [t(31.20) = 2.37; P = 0.02; d = 0.68; Fig. 1C].

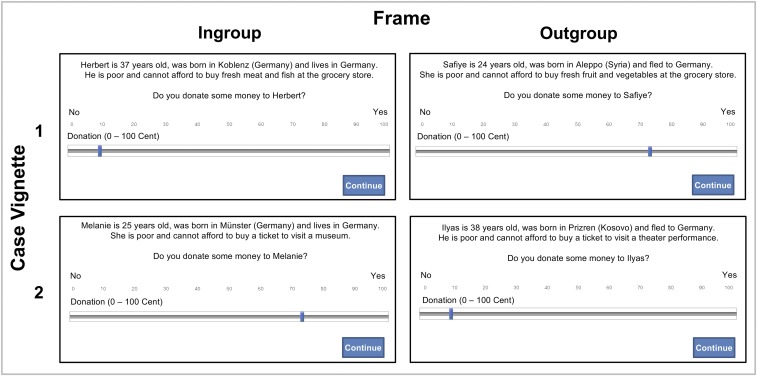

Fig. S1.

Task design of Experiment 2. Given are corresponding examples of ingroup and outgroup case vignettes presented in Experiment 2. In total, the task consisted of 50 such vignettes briefly describing the personal needs of poor people, half of whom were framed as refugees (outgroup) and half of whom were framed as natives (ingroup), respectively.

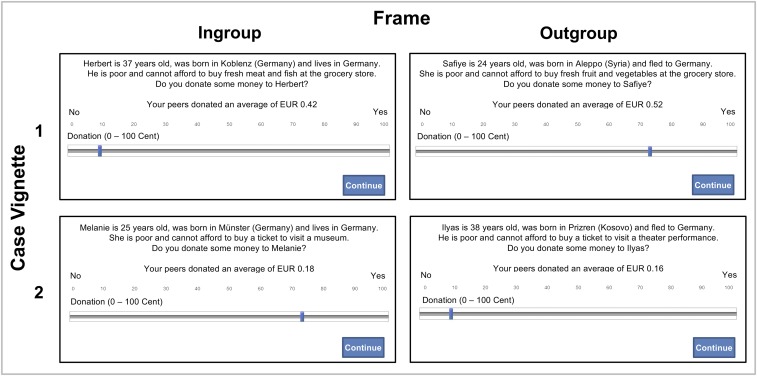

To address the question of whether administration of a peer-derived altruistic norm in addition to OXTIN could augment altruistic responses in Xi high scorers, the task was reiterated in Experiment 3, with the exception that this time, each case presentation also included information about the average contribution choices of all their male and female peers enrolled in Experiment 1 (Fig. S2). A repeated-measures ANOVA with “norm” (present, absent) as an additional within-subject variable revealed a three-way interaction among treatment, Xi index, and norm [F(1,103) = 5.51; P = 0.02; η2 = 0.05]. Not surprisingly, deviation from the norm was relatively low for Xi low scorers due to their distinct altruistic tendency displayed in Experiment 2, which is consistent with a trend-to-significant effect of norm administration in PLCIN-treated subjects [outgroup, t(27) = 1.73 (P = 0.095; d = 0.34); ingroup, t(27) = 1.87 (P = 0.07; d = 0.35)] and no effect at all in OXTIN-treated subjects (all P values > 0.40). Intriguingly, application of OXTIN in conjunction with the altruistic norm prompted Xi high scorers, who had been resistant to either of these interventions alone (all P values > 0.64), to increase their outgroup-related donations by 74% [EUR 3.11 ± 3.37 with norm vs. EUR 1.79 ± 2.14 without norm; t(24) = 2.61; P = 0.02; d = 0.47; Fig. 1D]. This effect was weaker for the ingroup [EUR 2.46 ± 2.93 with vs. EUR 1.51 ± 2.00 without norm; t(24) = 1.81; P = 0.08; d = 0.38]. The facilitation of altruism observed in Xi high scorers becomes even more obvious when relativizing the donated sums to those obtained in Experiment 1; relative to this 100% benchmark, donations in Xi high scorers climbed from 23% to 38% as a consequence of pairing OXTIN treatment with the peer-derived altruistic norm.

Fig. S2.

Task design of Experiment 3. Given are corresponding examples of ingroup and outgroup case vignettes presented in Experiment 3. In contrast to Experiment 2, the vignettes contained normative incentives (i.e., participants were additionally informed about the average sums their peers had donated in Experiment 1 for each case).

Discussion

As mentioned earlier, the parable of the Good Samaritan describes a highly influential ethical maxim of helping outgroup members who have fallen in need, and has attained paramount political significance in the African-American civil rights movement (35). However, as yet, the social and biological conditions promoting such outgroup-directed altruism have not been determined. Here, we show that enhanced activity of the OXT system paired with charitable social cues can help counter the effects of xenophobia by fostering altruism toward refugees. These results are especially important in the light of evidence that even a minority of selfish noncooperators (Fig. 1C) may suffice to force the majority of altruists to defect, resulting in a rapid decay of altruistic cooperation within a population (7). Therefore, selfish motives impose an impending threat to altruistic cooperation (27). Here, we demonstrate that normative incentives co-occurring with elevated activity of the OXT system exert a motivational force for inducing altruistic cooperation with outsiders, even in those individuals who refuse to do so in the absence of such exogenous triggers. Since their selfless behavior only emerged as a result of OXT-enhanced social norm compliance, it is extrinsically motivated. However, even intrinsically motivated (i.e., self-generated) forms of altruism may build on internalized social (e.g., parental) norms and engage endogenous OXT signaling. Consistent with previous observations that OXTIN increases generosity per se (16, 36), we found a generalized increase in donations toward both the outgroup and the ingroup (Fig. 1B). However, this effect was mainly driven by the higher donations of the Xi low scorers (Fig. 1C), and therefore is in line with evidence emphasizing a sensitivity of OXTIN effects to person- and context-dependent factors (19, 37, 38). Whereas previous studies have focused either on the efficacy of ingroup norms as a potential means of stabilizing altruistic cooperation (28) or on the facilitating effects of OXT signaling on social conformity (23, 24), none have combined both interventions to enhance social norm adherence. Here, we provide evidence that a xenophobic rejection of refugees can be reversed by coupling enhanced activity of the OXT system to a normative incentive for cooperation with peers; neither intervention alone was sufficient to alter selfish responses in Xi high scorers, illustrating the relative resistance of outgroup rejection to exogenous modification.

Unfortunately, open and latent xenophobia continue to be a major challenge for European democracies. Since foraging societies were afflicted by intergroup conflict at all times, a strong inclination to categorically differentiate between ingroup (“us”) and outgroup (“them”) members may have conferred evolutionary advantages (39). Warfare may even have catalyzed cultural selection, as the dominant groups have forced their social preferences and norms on the defeated groups (7, 27). Our results raise the question of whether higher levels of xenophobia could be associated with a reduced sensitivity to others’ distress, irrespective of their group membership. This may explain why the Xi high scorers in our sample did not exhibit an altruism bias to either group. It should be emphasized, though, that the measured Xi scores represent relatively typical levels of xenophobia within the general population. Based on the heterogeneity of xenophobic attitudes within certain groups and regions (40, 41), future research with a focus on the extreme ends of xenophobia is needed to provide a more nuanced understanding of the effects of OXTIN on outgroup-directed altruism. Furthermore, given that OXTIN can produce sexual-dimorphic effects (42, 43), we cannot extrapolate our findings to women. Clearly, future studies are warranted to explore the relationship between the effects of OXTIN on outgroup-directed altruism and a wider array of person- and context-dependent factors, including sex, age, and self-report measures of xenophobia.

In contrast to previous studies, which have used OXTIN to illustrate a contribution of OXT signaling in parochial altruism, especially under circumstances of intergroup conflict (20, 21), we demonstrate that enhanced activity of the OXT system facilitates social norm compliance, thus inducing altruism toward outgroup members even in the most selfish and xenophobic individuals. Given evidence indicating that social group activities with peers, such as singing in a choir (44), are associated with elevated endogenous OXT release (45), our findings suggest that greater focus should be placed on enabling positive social encounters among citizens of hosting countries that communicate a prosocial norm; that is, by affirming and emphasizing the benefits of ethnic diversity, religious pluralism, and cultural differentiation. This may include the promotion of balanced and informed media reporting, the integration of refugee themes to the curricula of schools and universities, or the organization of events that involve the general public and bring communities together by promoting sustained experience- and information-sharing on the situation of refugees (46). The effect of solutions combining selective enhancement of OXT signaling and peer influence would be expected to diminish selfish motives, and thereby increase the ease by which people adapt to rapidly changing social ecosystems. More generally, our results imply that an OXT-enforced social norm adherence could be instrumental in motivating a more generalized acceptance toward ethnic diversity, religious plurality, and cultural differentiation resulting from migration by proposing that interventions to increase altruism are most effective when charitable social cues instill the notion that one’s ingroup shows strong affection for an outgroup. Furthermore, UNESCO has emphasized the importance of developing neurobiologically informed strategies for reducing xenophobic, hostile, and discriminatory attitudes (47). Thus, considering OXT-enforced normative incentives in developing future interventions and policy programs intended to reduce outgroup rejection may be an important step toward making the principle of social inclusion a daily reality in our societies.

Materials and Methods

Our study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Bonn, and was carried out in compliance with the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written, informed consent.

Experimental Design.

The altruistic donation task, which was framed in the context of Europe’s refugee crisis, included 50 authentic case vignettes in total. Each of the 25 ingroup case vignettes had a corresponding outgroup counterpart (Fig. S1). The descriptions presented in the vignettes were composed in a standardized manner to keep them identical regarding formal criteria such as style, word count, and format. Each individual was introduced by his/her name, age, place of birth, country of origin, and personal need. The selection of home countries for the outgroup frame was based on reports published in 2015 by the European Commission, documenting conflicts, persecution, and poverty in the Middle East and Eastern Europe as the major drivers of forced migration to the European Union (48, 49). Personal needs comprised those essential elements the United Nations has defined as minimum standards for leading a safe and dignified life (30); that is, access to food, adequate housing, or participation in social and cultural life (31, 32). All 50 case scenarios were balanced in terms of age and sex of the needy persons and were presented in random order. The participants read and completed the donation task at their own pace. Subjects were endowed with EUR 50 and could donate a maximum of EUR 1 to each case, leaving them the rest (EUR 0–50) as personal payoff, if the lottery ticket, which they drew on completion of the donation task, had a number on the inside (chance of winning: 10%). Furthermore, subjects were informed that all their donations were subtracted from this endowment of EUR 50.

Procedure and Participants.

Experiment 1.

In Experiment 1, a total of 76 healthy female (n = 53) and male (n = 23) undergraduate students (mean age ± SD, 21.2 ± 3.0 y; Table 1) completed the donation task. The rationale of Experiment 1 was to generate normative cues for altruistic responding toward refugees. For this purpose, subjects were assembled in a lecture hall. Using a paper–pencil version of the altruistic donation task, the participants were instructed to indicate the exact amount of their donation for each case vignette on the forms, which were later collected by the experimenter. By design, this experimental setting enabled reputation pressures due to social interactions among peers, such that the sums donated in Experiment 1 were higher than those from Experiments 2 and 3, in which we eliminated social interaction.

Table 1.

Demographics, personality traits, and attitudes (Experiment 1, n = 76)

| Mean | SD | |

| Age, y | 21.13 | 2.98 |

| Education, y | 13.40 | 1.75 |

| Donation, EUR/y | 33.20 | 59.53 |

| Interpersonal Reactivity Index | 45.76 | 5.53 |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | 37.67 | 7.86 |

| Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale | 30.91 | 19.79 |

| Realistic threat | 3.39 | 1.61 |

| Symbolic threat | 5.35 | 1.36 |

| Social Value Orientation: Prosociality | 5.55 | 3.65 |

| Social Value Orientation: Individualism | 2.97 | 3.36 |

| Social Value Orientation: Competition | 0.47 | 1.51 |

| Sex, male/female | 23/53 |

Experiments 2 and 3.

For Experiments 2 and 3, a new group of participants was invited to sign up for the experiment via the online database hroot (50) of the BonnEconLab. A total of 127 healthy male volunteers enrolled in the double-blind, randomized, parallel-group trial design and self-administered a dose of 24 IU (three puffs per nostril, each with 4 IU; Novartis) of OXTIN or PLCIN 40–45 min before the start of the donation task. The placebo solution contained the identical ingredients except the peptide itself. The study comprised a screening session in the morning and an experimental session in the afternoon. Screening entailed the exclusion of current or past physical or psychiatric illness (including drug and alcohol abuse), as assessed by medical history and the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (51). To control for possible pretreatment differences, we assessed anxiety traits with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (52), depressive symptoms with the Beck Depression Inventory (53), early social adversity with the Childhood-Trauma-Questionnaire (54), and autistic-like traits with the Autism-Spectrum-Quotient (55). Furthermore, we assessed cooperative and altruistic attitudes based on the subjects’ social value orientation (56), as well as empathy with the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (57) and their susceptibility to external (dis)approval with the Social Desirability Scale (58). In addition, the subjects were asked to indicate their personal income and donation behavior during the last year. There were no a priori differences between the OXTIN and PLCIN groups for Xi low and high scorers (Tables 2 and 3). Moreover, subjects were naive to prescription-strength psychoactive medication and had not taken any over-the-counter psychoactive medication in the preceding 4 wk. Participants were asked to maintain their regular sleep and waking times and to abstain from caffeine and alcohol intake on the day of the test session. During testing, a total of 20 participants (OXTIN: n = 10; PLCIN: n = 10) could not complete the donation task due to technical issues. Thus, the final analyses were performed on data from 107 participants (mean age ± SD, 24.16 ± 3.2 y).

Table 2.

Demographics, personality traits, and attitudes in the OXT and placebo group for Xi low scorers (Experiments 2 and 3)

| OXTIN group (n = 26), Mean (SD) | PLCIN group (n = 28), Mean (SD) | t | P | |

| Age, y | 23.65 (2.59) | 23.82 (2.99) | −0.22 | 0.83 |

| Education, y | 15.62 (3.83) | 15.78 (2.41) | −0.19 | 0.85 |

| Donations in 2015, EUR/y | 41.60 (51.84) | 26.50 (39.72) | 0.78 | 0.44 |

| Interpersonal Reactivity Index | 41.35 (6.50) | 42.75 (5.36) | −0.86 | 0.39 |

| Childhood-Trauma Quotient | 30.65 (4.48) | 30.36 (5.20) | 0.22 | 0.82 |

| Autism-Spectrum Quotient | 14.92 (5.36) | 16.00 (3.87) | −0.84 | 0.41 |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | 47.58 (2.14) | 47.25 (2.08) | 0.57 | 0.57 |

| Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale | 26.30 (17.31) | 25.35 (14.10) | 0.22 | 0.82 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 3.76 (4.07) | 4.03 (4.31) | −0.23 | 0.82 |

| Realistic threat | 1.80 (0.60) | 1.85 (0.59) | 0.31 | 0.76 |

| Symbolic threat | 4.82 (0.90) | 4.65 (1.05) | 0.60 | 0.51 |

| Social Value Orientation: Prosociality | 5.50 (4.05) | 4.39 (4.44) | −0.96 | 0.34 |

| Social Value Orientation: Individualism | 3.15 (3.94) | 4.57 (4.47) | −1.24 | 0.22 |

| Social Value Orientation: Competition | 0.35 (1.77) | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.93 | 0.36 |

| Social Desirability Scale | 8.61 (1.32) | 9.14 (1.40) | 1.41 | 0.16 |

Table 3.

Demographics, personality traits, and attitudes in the OXT and placebo group for Xi high-scorers (Experiments 2 and 3)

| OXTIN group (n = 25), Mean (SD) | PLCIN group (n = 28), Mean (SD) | t | P | |

| Age, y | 24.48 (2.96) | 24.71 (4.23) | −0.23 | 0.82 |

| Education, y | 16.92 (2.53) | 15.41 (4.55) | 1.46 | 0.14 |

| Donations in 2015, EUR | 35.45 (45.85) | 72.22 (98.71) | −1.10 | 0.28 |

| Interpersonal Reactivity Index | 38.92 (5.51) | 38.60 (5.05) | 0.21 | 0.83 |

| Childhood-Trauma Quotient | 30.48 (4.55) | 32.37 (7.06) | −1.13 | 0.26 |

| Autism-Spectrum Quotient | 14.72 (5.53) | 16.71 (3.99) | −1.51 | 0.13 |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | 47.60 (3.26) | 47.25 (3.18) | 0.39 | 0.69 |

| Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale | 25.04 (21.96) | 29.25 (17.30) | −0.78 | 0.44 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 3.96 (4.07) | 4.71 (4.58) | −0.63 | 0.53 |

| Realistic threat | 4.52 (1.51) | 4.27 (1.29) | −0.63 | 0.53 |

| Symbolic threat | 5.93 (1.21) | 5.54 (1.22) | 1.16 | 0.25 |

| Social Value Orientation: Prosociality | 2.20 (3.39) | 3.50 (4.02) | −1.27 | 0.21 |

| Social Value Orientation: Individualism | 6.44 (3.61) | 5.46 (4.03) | 0.92 | 0.36 |

| Social Value Orientation: Competition | 0.36 (1.80) | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.89 | 0.38 |

| Social Desirability Scale | 8.72 (1.74) | 8.39 (1.61) | −0.71 | 0.16 |

During Experiments 2 and 3, each participant was seated alone in front of a computer screen in a separate test cubicle that was closed off with curtains, while being exposed to the same donation task and instructional primes as established in Experiment 1. This experimental setting eliminated any interactions with peers or the experimenter. To exclude potential confounding influences of sex differences, we compared OXT effects between male participants, rather than between men and women. Participants performed two runs of the donation task. In Experiment 2, participants had no further information than that they could donate some, none, or all of their money with a maximum of EUR 1 for each case vignette (Fig. S1). In Experiment 3, the same sample of participants was additionally informed about the higher average donations made by their peers in each scenario (e.g., “Your peers previously donated EUR 0.50”) (Fig. S2). The scenarios of the donation task were presented with the software Qualtrics. Participants were asked to indicate their donation by moving a slider placed under each scenario. By varying the starting positions of the slider, each choice required a similar effort.

Xenophobia index.

In a separate screening session, we evaluated xenophobia by measuring the attitudes toward refugees based on an adapted assessment instrument developed by Schweitzer and colleagues (33). Adaptions encompassed the wording; for example, “Australian refugee” was replaced by “German refugee.” The assessment instrument contained two inventories, in which participants indicated how strongly they associate refugees with realistic and symbolic threats. In our analyses, we focused on the realistic threat inventory, which includes seven items and has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.83). This decision was based on previous evidence indicating that realistic threats (e.g., perceived threats to economic interest, social status, or health), rather than symbolic threats (e.g., perceived threats to morals, values, or beliefs), more robustly predict perceptions of xenophobia (40, 41, 59). The realistic threat scale items encompass different threat perceptions; for example: “Refugees are not displacing German workers from their jobs” or “Refugees have increased the tax burden on Germans.” Responses were coded on a 10-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“I strongly disagree”) to 10 (“I strongly agree”). All items were recoded such that higher values reflected greater feelings of perceived realistic threats. The term Xi index, which we used for subsequent analyses, refers to a subject’s mean score achieved on the realistic threat inventory.

Statistical Analysis.

Demographic, neuropsychological, and behavioral data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24. Quantitative behavioral data were compared using mixed analysis of variance and post hoc t-tests. Pearson’s product-moment correlation was used for correlation analysis. Eta-squared and Cohen’s d were calculated as measures of effect size. For qualitative variables, Pearson’s χ2 tests were used. All reported P values are two-tailed if not otherwise stated, and P values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

All relevant data are stored on a server of the Division of Medical Psychology at the University of Bonn Medical Center and are available for research purposes on request by contacting R.H.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank two anonymous referees for their generous comments. This research was supported by a grant from the German Science Foundation (to R.H. and D.S.; HU 1202/4-1 and BE 5465/2-1).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1705853114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.DePillis L, Saluja K, Lu D. December 21, 2015 A visual guide to 75 years of major refugee crises around the world. Washington Post. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/world/historical-migrant-crisis/. Accessed May 20, 2017.

- 2.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 2016 Global trends: Forced displacement in 2015. Available at www.unhcr.org/576408cd7.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2017.

- 3.Crisp RJ, Meleady R. Adapting to a multicultural future. Science. 2012;336:853–855. doi: 10.1126/science.1219009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 2016 Learning to live together. Available at www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/international-migration/glossary/xenophobia/. Accessed March 13, 2017.

- 5.Aisch G, Pearce A, Rousseau B. 2016 How far is Europe Swinging to the right? NY Times. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/05/22/world/europe/europe-right-wing-austria-hungary.html?_r=0. Accessed March 12, 2017.

- 6.Quadbeck E. 2016 Freiwillige Flüchtlingshelfer leisten Millionen Stunden. Rheinische Post. Available at www.rp-online.de/panorama/deutschland/freiwillige-fluechtlingshelfer-leisten-millionen-stunden-aid-1.5789308. Accessed March 12, 2017.

- 7.Fehr E, Fischbacher U. The nature of human altruism. Nature. 2003;425:785–791. doi: 10.1038/nature02043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature. 2005;437:1291–1298. doi: 10.1038/nature04131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donaldson ZR, Young LJ. Oxytocin, vasopressin, and the neurogenetics of sociality. Science. 2008;322:900–904. doi: 10.1126/science.1158668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurlemann R, Marsh N. [New insights into the neuroscience of human altruism] Nervenarzt. 2016;87:1131–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00115-016-0229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Born J, et al. Sniffing neuropeptides: A transnasal approach to the human brain. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:514–516. doi: 10.1038/nn849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee MR, et al. Oxytocin by intranasal and intravenous routes reaches the cerebrospinal fluid in rhesus macaques: Determination using a novel oxytocin assay. Mol Psychiatry. March 14, 2017 doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Striepens N, et al. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid and blood concentrations of oxytocin following its intranasal administration in humans. Sci Rep. 2013;3:3440. doi: 10.1038/srep03440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer-Lindenberg A, Domes G, Kirsch P, Heinrichs M. Oxytocin and vasopressin in the human brain: Social neuropeptides for translational medicine. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:524–538. doi: 10.1038/nrn3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature. 2005;435:673–676. doi: 10.1038/nature03701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zak PJA, Stanton AA, Ahmadi S. Oxytocin increases generosity in humans. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domes G, Heinrichs M, Michel A, Berger C, Herpertz SC. Oxytocin improves “mind-reading” in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:731–733. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurlemann R, et al. Oxytocin enhances amygdala-dependent, socially reinforced learning and emotional empathy in humans. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4999–5007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5538-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marsh N, et al. The neuropeptide oxytocin induces a social altruism bias. J Neurosci. 2015;35:15696–15701. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3199-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Dreu CK, et al. The neuropeptide oxytocin regulates parochial altruism in intergroup conflict among humans. Science. 2010;328:1408–1411. doi: 10.1126/science.1189047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Dreu CK, Greer LL, Van Kleef GA, Shalvi S, Handgraaf MJ. Oxytocin promotes human ethnocentrism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1262–1266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015316108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samuni L, et al. Oxytocin reactivity during intergroup conflict in wild chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:268–273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616812114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stallen M, De Dreu CK, Shalvi S, Smidts A, Sanfey AG. The herding hormone: Oxytocin stimulates in-group conformity. Psychol Sci. 2012;23:1288–1292. doi: 10.1177/0956797612446026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y, Kendrick KM, Zheng H, Yu R. Oxytocin enhances implicit social conformity to both in-group and out-group opinions. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;60:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edelson MG, et al. Opposing effects of oxytocin on overt compliance and lasting changes to memory. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:966–973. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fehr E, Gächter S. Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature. 2002;415:137–140. doi: 10.1038/415137a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fehr E, Rockenbach B. Detrimental effects of sanctions on human altruism. Nature. 2003;422:137–140. doi: 10.1038/nature01474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fehr E, Fischbacher U. Social norms and human cooperation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernhard H, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Parochial altruism in humans. Nature. 2006;442:912–915. doi: 10.1038/nature04981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The World Commission on Enviornment and Development . Our Common Future. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sterkl M. 2017 Es reicht kaum zum Essen. Die ZEIT. Available at www.zeit.de/2017/19/armut-wien-familie-sparen-lebensmittel. Accessed May 20, 2017.

- 32.United Nations 1995 Eradication of poverty. Available at www.un.org/esa/socdev/wssd/text-version/agreements/poach2.htm. Accessed May 20, 2017.

- 33.Schweitzer R, Perkoulidis S, Krome S, Ludlow C, Ryan M. Attitudes towards refugees: The dark side of prejudice in Australia. Aust J Psychol. 2005;57:170–179. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guastella AJ, et al. Recommendations for the standardisation of oxytocin nasal administration and guidelines for its reporting in human research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:612–625. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King ML. 1968 The parable of the Good Samaritan [audio recording]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=geX-a5PqxaY. Accessed March 25, 2017.

- 36.Barraza JA, McCullough ME, Ahmadi S, Zak PJ. Oxytocin infusion increases charitable donations regardless of monetary resources. Horm Behav. 2011;60:148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurlemann R. Oxytocin-augmented psychotherapy: Beware of context. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:377. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartz JA, Zaki J, Bolger N, Ochsner KN. Social effects of oxytocin in humans: Context and person matter. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Efferson C, Lalive R, Fehr E. The coevolution of cultural groups and ingroup favoritism. Science. 2008;321:1844–1849. doi: 10.1126/science.1155805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray KE, Marx DM. Attitudes toward unauthorized immigrants, authorized immigrants, and refugees. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2013;19:332–341. doi: 10.1037/a0030812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayda AM. Who is against immigration? A cross-country investigation of individual attitudes toward immigrants. Rev Econ Stat. 2006;88:510–530. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fischer-Shofty M, Levkovitz Y, Shamay-Tsoory SG. Oxytocin facilitates accurate perception of competition in men and kinship in women. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013;8:313–317. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheele D, et al. Opposing effects of oxytocin on moral judgment in males and females. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35:6067–6076. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keeler JR, et al. The neurochemistry and social flow of singing: Bonding and oxytocin. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:518. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kis A, Kemerle K, Hernádi A, Topál J. Oxytocin and social pretreatment have similar effects on processing of negative emotional faces in healthy adult males. Front Psychol. 2013;4:532. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 2002 Strengthening protection capacities in host countries. Available at www.unhcr.org/3b95d78e4.pdf.Accessed March 26, 2017.

- 47.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 2001 World Conference against Racism. Available at www.un.org/WCAR/statements/unescoE.htm. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- 48.Eurostat 2016 Asylum in the EU Member States. Record number of over 1.2 million first time asylum seekers registered in 2015. Available at ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7203832/3-04032016-AP-EN.pdf/. Accessed May 29, 2017.

- 49.News BBC. 2016 Migrant crisis: Migration to Europe explained in seven charts. Available at www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34131911. Accessed May 29, 2017.

- 50.Stephan WG, Ybarra O, Bachman G. Prejudice toward immigrants. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1999;29:2221–2237. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheehan DV, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spielberger CD. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: A Comprehensive Bibliography. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1984. p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A Retrospective Self-report. Harcourt Brace & Co.; San Antonio, TX: 1998. p. viii. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31:5–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1005653411471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Lange PAM, Otten W, De Bruin EMN, Joireman JA. Development of prosocial, individualistic, and competitive orientations: Theory and preliminary evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73:733–746. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davis MH. Measuring individual-differences in empathy - evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44:113–126. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stöber J. The Social Desirability Scale-17 (SDS-17) Eur J Psychol Assess. 2001;17:222–232. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bock O, Baetge I, Nicklisch A. hroot: Hamburg Registration and Organization Online Tool. Eur Econ Rev. 2014;71:117–120. [Google Scholar]