Abstract

Purpose

Transcriptome analysis by next generation sequencing allows qualitative and quantitative profiling of expression patterns associated with development and disease. However, most transcribed sequences do not encode proteins, and little is known about the functional relevance of noncoding (nc) transcriptome in neuronal subtypes. The goal of this study was to perform a comprehensive analysis of long noncoding (lncRNAs) and antisense (asRNAs) RNAs expressed in mouse retinal photoreceptors.

Methods

Transcriptomic profiles were generated at six developmental time points from flow-sorted Nrlp-GFP (rods) and Nrlp-GFP;Nrl−/− (S-cone like) mouse photoreceptors. Bioinformatic analysis was performed to identify novel noncoding transcripts and assess their regulation by rod differentiation factor neural retina leucine zipper (NRL). In situ hybridization (ISH) was used for validation and cellular localization.

Results

NcRNA profiles demonstrated dynamic yet specific expression signature and coexpression clusters during rod development. In addition to currently annotated 586 lncRNAs and 454 asRNAs, we identified 1037 lncRNAs and 243 asRNAs by de novo assembly. Of these, 119 lncRNAs showed altered expression in the absence of NRL and included NRL binding sites in their promoter/enhancer regions. ISH studies validated the expression of 24 lncRNAs (including 12 previously unannotated) and 4 asRNAs in photoreceptors. Coexpression analysis demonstrated 63 functional modules and 209 significant antisense-gene correlations, allowing us to predict possible role of these lncRNAs in rods.

Conclusions

Our studies reveal coregulation of coding and noncoding transcripts in rod photoreceptors by NRL and establish the framework for deciphering the function of ncRNAs during retinal development.

Keywords: lncRNA, gene regulation, RNA profiling, photoreceptor development

Eukaryotic genomes include a complete blueprint for generating diverse cellular morphologies and functional attributes to produce complex architecture of distinct tissues. Each tissue, and cell type within, possesses a characteristic gene expression pattern that establishes its unique identity at a given time during its lifecycle. The transcriptome is dynamic and responds to intrinsic genetic programs and microenvironment. Over 75% of the genome is transcribed, yet only 2% is devoted to protein translation.1–3 The noncoding transcriptome, previously regarded as being transcriptional noise or “junk,”4,5 has come into sharp focus recently with an unprecedented increase in the discovery of small (<200 base pairs [bp]) and long (>200 bp) noncoding transcripts that exhibit developmental and cell-type specificity and influence wide-ranging physiologic functions.6,7

The term long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) originally was coined for transcripts of longer than 200 bp (to distinguish these from small ncRNAs, such as t-RNAs and miRNAs) that do not have an apparent protein-coding potential; however, numerous exceptions exist.8 Despite remarkable similarity in genomic structure and processing, several unique features including biogenesis, secondary structure, and subcellular localization, distinguish lncRNAs from protein-coding transcripts.8,9 As many as 50,000 lncRNA genes have been annotated in the human genome.10 Of these, almost 40% are predominantly expressed in the brain,11 leading to tremendous interest in studying their function during development and in disease pathology.12 LncRNAs have been associated with diverse biological processes, including pluripotency and cell division,13 synaptogenesis,14–16 response to injury,17–19 and transcriptional,20 and epigenetic regulation.21,22 Anti-sense RNAs (asRNAs) constitute a less-studied subclass of lncRNAs that originate from the opposite strand of 20% to 40% of protein-coding genes23 and appear to modulate in cis the function of cognate coding transcript. To avoid confusion, we used the term lncRNA for long intergenic noncoding RNA (>200 bp) mapping to an intergenic region and not containing an open reading frame of longer than 50 residues, whereas asRNAs refers to a transcript overlapping with an annotated gene structure.

The retina is a specialized sensory part of the central nervous system, designed to capture and transmit visual information to the brain. Expression profiling of the mammalian retina has provided insights into distinct cell types and circuits, permitted identification of disease genes and led to discovery of novel therapeutic paradigms.24 While the function of several miRNAs in the retina is becoming increasingly clear,25–27 only few studies have focused on lncRNAs. For example, the knockdown of TUG1 lncRNA, which is expressed in the developing retina and brain, resulted in malformed or nonexistent outer segments of transfected photoreceptors.28 Another lncRNA, RNCR2, seems to be associated with retinal cell fate acquisition as its loss resulted in an increase of amacrine cells and Müller glia.29 RNCR4 may work with miR-183/96/182 locus to control retinal architecture.30 A number of asRNAs have been identified at eye transcription factor (TF) loci and their functions in modulating gene expression are being explored.31–33 Global profiling of retinal noncoding transcriptome has not been accomplished except for one report on RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis that identified 18 evolutionarily conserved retinal lncRNAs.34

Photoreceptors initiate the visual process by capturing photons and represent 75% to 80% of neuronal cells in the mammalian retina.35 Cone photoreceptors mediate high acuity daylight and color vision, whereas rods are highly sensitive and associated with low-resolution night vision. Multiple TFs control the differentiation of photoreceptors from retinal progenitors.36–38 Rod cell fate is dependent critically on the Maf-family leucine zipper protein NRL.36 The absence of Nrl (Nrl−/− mouse) results in the retina with S-cone–like photoreceptors,39 and developing cones can be transformed into rods by Nrl expression.40 Acquisition of rod-specific expression of NRL is proposed to be a key event in the evolution of rod-dominant retina in early mammals.41 NRL interacts with cone-rod homeobox (CRX) and other transcription factors to control gene expression in rod photoreceptors.36,42–44 Transcriptome analysis has revealed an NRL-regulated network of protein-coding genes and a sharp transition in expression patterns from postnatal days 6 and 10 in concordance with rod morphogenesis and functional maturation.45

Given the rapidly emerging functions of lncRNAs, a global understanding of rod photoreceptor specific noncoding transcriptome is crucial for constructing gene regulatory networks (GRNs) that underlie retinal development and disease. We report a comprehensive profile of lncRNAs and asRNAs in developing rod photoreceptors, along with the identification of known and unannotated ncRNAs that exhibit rod-specific expression mediated by NRL. Consistent with the coding transcriptome,45 we discovered a major shift in rod expression profile of ncRNAs from P6 to P10 during development, further validating their involvement in key biological processes. Our studies suggest potential functions of lncRNAs based on coexpression cluster analysis and provide a framework for elucidating integrated GRNs that guide rod development.

Materials and Methods

RNA Profiling of Mouse Rod Photoreceptors

All procedures involving the use of mice were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Eye Institute (NEI). The retinas of Nrlp-GFP and Nrlp-GFP;Nrl−/− transgenic mice46 that were back-crossed more than 10 times to C57BL/6 were collected at six postnatal developmental stages in Hank's balanced salt solution (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) and dissociated by Accutase digestion (Life Technologies). After removing clumps, the cells were subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate GFP-positive cells. A stringent precision setting was set on FACS Aria II (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA, USA) to maximize the purity of the sorted cells. Samples were included in downstream processing if they showed purity of above 96% after re-sorting. RNA was isolated from sorted cells by the TRIzol LS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) method, following manufacturer's instructions.

Strand-Specific RNA-Seq

Bioanalyzer RNA 6000 Pico assay (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to assess RNA quality; only samples with RNA integration number of >7 were used to generate sequencing libraries. TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit-v2 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to make strand-specific libraries from 20 ng of total RNA with slight modifications.47 Libraries were sequenced on the Genome Analyzer IIx platform (Illumina). In concordance with ENCODE consortium guidelines (available in the public domain at https://www.encodeproject.org/about/experiment-guidelines/, updated January 2017) and to reduce technical variability in RNA-seq data, we used at least two biological replicates for each developmental stage of WT rod and S-cone–like Nrl−/− photoreceptor cells. In total, 30 transcriptome sequencing libraries were studied in the bioinformatics analysis steps of the study.

Reference Genome-Guided De Novo Transcriptome Assembly

To generate a comprehensive catalog of previously unannotated noncoding transcripts from WT rod and S-cone–like Nrl−/− photoreceptor RNA-seq libraries, we performed genome guided de novo transcriptome assembly for each sample individually. Short reads in each library were first aligned to Mus musculus reference genome (GRCm38.p3) through splice-aware aligner, TopHat2 v2.0.1148 (Supplementary Table S1). Then, de novo assembly was performed using Cufflinks v2.2.1.49 Transcript features identified through transcriptome assembly were queried against Ensembl v78 database, and previously unannotated transcripts were determined (see GEO submission GSE 74660 for the GTF file of all unannotated transcripts). Among all putative transcripts, we determined lncRNA and asRNA sequences as follows: (1) we selected only intergenic and antisense transcripts with ≥2 exons, (2) transcripts < 200 nucleotides in length were filtered out, (3) coding potential of each transcript was tested by TransDecoder v1 (available in the public domain at http://transdecoder.github.io/), and transcripts having open reading frame ≥ 50 were not included in further analysis steps, (4) the remaining transcripts queried against Pfam-A and Pfam-B50 databases v27.0 with HMMER3 v3.1b1 (available in the public domain at http://hmmer.janelia.org) to check whether they had any functional protein domain. In this step, E-value threshold was set to 0.05 and transcripts above this threshold were considered as noncoding sequences. To validate our de novo pipe line, we performed quantitative (q) RT-PCR on 10 previously unannotated lncRNA (Supplementary Fig. S5), and were able to detect all of them in RNA isolated from whole retina. qRTPCR reactions were performed in triplicates, and normalized to endogenous control, Hprt. The results were analyzed by QuantStudio design and analysis software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Transcript Level Quantification and Statistical Analysis

The abundance estimation of known and previously unannotated transcripts was performed by streaming Bowtie2 v2.1.051 aligned reads to eXpress v1.3.1. To exclude genes that were not expressed consistently across all replicates of individual time points, we implemented a filter that checks for ≥1 FPKM in all replicates at any one-time point. This filtering prunes a majority of genes that are not expressed or show low-level highly variable expression patterns. For data sets downloaded from ENCODE, transcripts that were expressed >1 FPKM in all samples of any tissue were considered for further downstream analysis. Differential expression analysis was performed using limma v3.20.952 to compare Nrl−/− data to WT samples at each time point. Effective counts from eXpress output of transcripts passing FPKM filter were TMM normalized using edgeR.53,54 A generalized linear model was set up with time and genotype as factors, dispersion estimation performed using the voom function, and appropriate contrast statistics employed using eBayes function.

Gene Level Quantification

The tximport R package55 was used to generate gene level counts from transcript level counts. A list object in R containing estimated counts, effective length, and FPKM values was imported into the summarizeToGene function along with Ensembl gene and transcript IDs. The gene level counts then were normalized using edgeR package and subsequently used to compute gene level CPMs.

Coexpression Network and GRN Analysis

Coexpression analysis of noncoding RNAs and protein-coding transcripts was performed with WGCNA package in R scientific computing environment v3.1.1 (available in the public domain at http://www.R-project.org/).56 Log2 normalized FPKM values of transcripts were used as input for WGCNA, and two separate unsigned weighted correlation networks were built by calculating correlation coefficients between all gene pairs across WT rod and S-cone like Nrl−/− photoreceptor samples, respectively. Afterwards, adjacency matrices were constructed by setting the soft threshold value of each correlation matrix at 10. Transcripts with a highly similar expression pattern then were grouped together by using the average linkage hierarchical clustering method. In the module identification step, we used dynamic tree cut algorithm and the merge cut height and minimum module size were set to 0.2 and 10, respectively. Then, each module including at least one transcript annotated as lncRNA in Ensembl v78 database was determined for functional GO enrichment analysis. Statistically significant GO terms in Biological Process domain for the selected modules were identified with the database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery (DAVID) online tool.57 In the enrichment procedure, we only included the transcripts having “protein-coding” annotation. False discovery rate (FDR) calculated with the Benjamini-Hochberg method, was used to measure the significance level of the GO terms, and the significance threshold was selected as 0.05.

A rank combined–based approach58 was implemented to infer targets of NRL. Adjusted P value from differential expression analysis and quantified ChIP-seq score59 metrics were used to compute ranked scores of all transcripts. The average rank score60 was calculated for every transcript.

In Situ Hybridization

The expression of noncoding transcripts was assessed in mouse retina sections using RNAscope technology (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Hayward, CA, USA) as described recently.45

Results

Noncoding Transcriptome of Developing Rod Photoreceptors

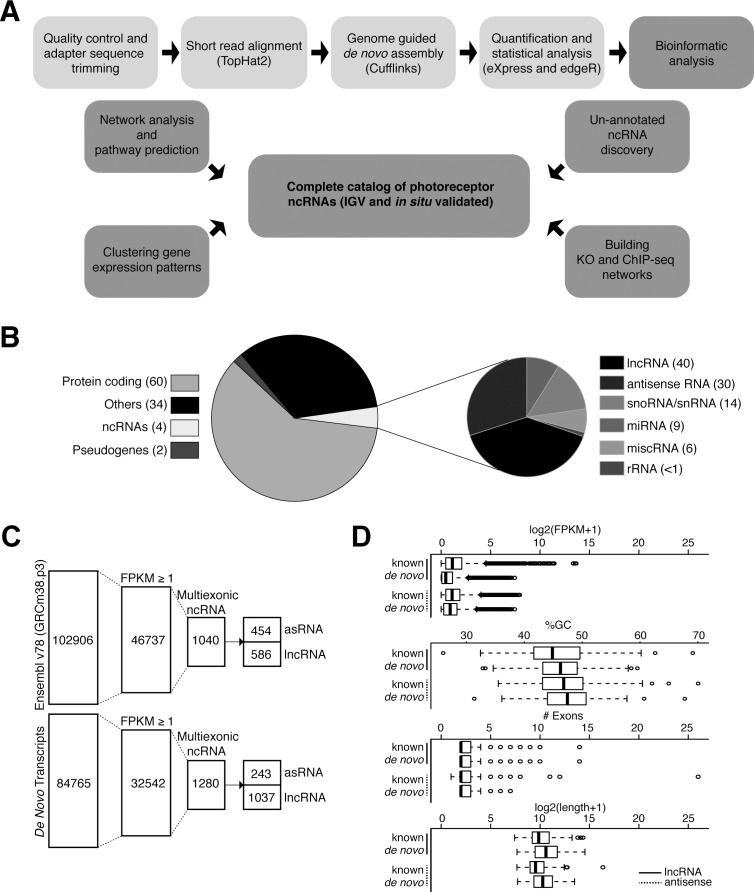

Taking advantage of Nrlp-GFP mice where GFP expression is under the control of Nrl promoter,46 we purified photoreceptors from wild type (WT, rods) and Nrl−/− (S-cone like, Nrlp-GFP;Nrl−/−) mouse retina and generated temporal RNA-seq profiles at 6 distinct stages of differentiation (from postnatal day [P] 2–P28)45 (Supplementary Table S1). We implemented a pipeline to identify lncRNAs (Fig. 1A) and initially quantified different types of transcribed sequences based on Ensembl v78 classification (i.e., protein-coding, miRNA, pseudogene, and so forth; Fig. 1B). In addition to identifying known ncRNAs based on Ensembl annotation, we performed a genome-guided de novo transcriptome assembly to discern previously unannotated lncRNAs. To minimize false-positives, we eliminated single exon transcripts and only selected those showing ≥1 fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) in all samples of at least one time point. To focus on the noncoding genes, we eliminated from analysis any transcripts containing open reading frames (ORFs) of >50 amino acids, or peptides with significant similarity to domains in the Pfam database. After these filtering steps, we identified 1623 lncRNA transcripts (586 known and 1037 previously unannotated) and 697 asRNAs (454 known and 243 previously unannotated) in rods (WT) as well as S-cone like photoreceptors (Nrl−/−; Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Workflow of the study and data overview. (A) Analysis pipeline for identifying photoreceptor ncRNAs. (B) Stratification of Ensembl transcriptome database (release 78) by transcript subtypes. The smaller pie chart shows six major ncRNA classes in Ensembl annotation. The numbers within parentheses indicate their corresponding percentages. (C) Filtering parameters for transcriptome analysis using Ensembl annotation (www.ensembl.org/index.html) and de-novo assembly, to identify lncRNAs and asRNAs expressed in WT rods and S-cone like Nrl−/− photoreceptors. The numbers within each column represent the total number of transcripts that meet filtering criteria. (D) Box plot visualization for comparison of known and novel noncoding genes for expression level (FPKM), %GC, number of exons, and gene length.

We then examined gene structure and expression characteristics of transcripts identified by de novo assembly and compared these to their annotated counterparts to assess the similarity between the two types of genes (Fig. 1D). The unannotated transcripts showed similar attributes as the known genes; however, previously unannotated transcripts displayed lower expression levels and tended to be longer despite having roughly similar number of exons and GC content.

Cell Type Specific Expression of lncRNAs

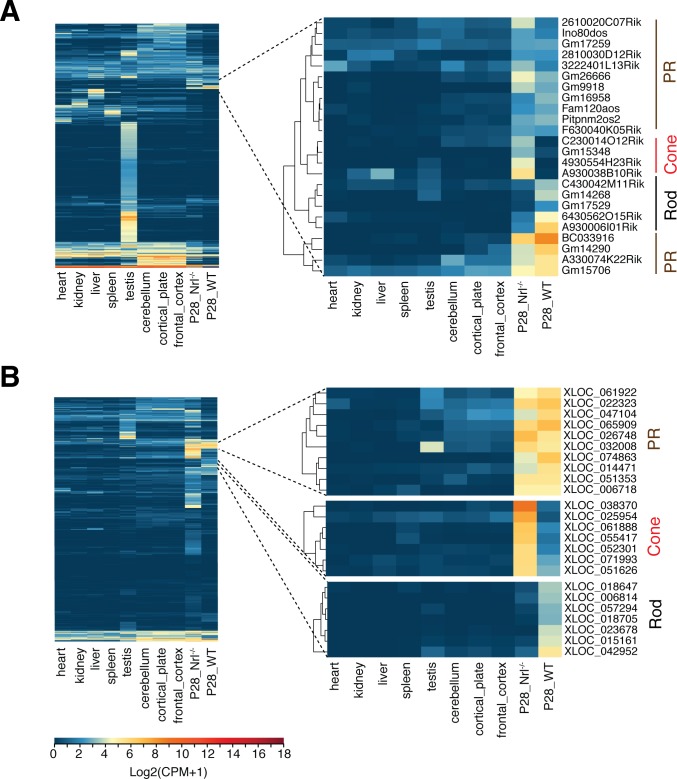

We compared RNA-seq data from mature (P28) photoreceptors with the data from three neuronal and five nonneuronal tissues (downloaded from ENCODE)61,62 using our pipeline and identified a subset of previously annotated lncRNAs demonstrating photoreceptor-specific expression (Fig. 2A). Annotated lncRNAs showing photoreceptor specific expression included A930038B10Rik (part of a “Cone” cluster) and A930006I01Rik (part of a “Rod” cluster). Evaluation of lncRNAs, identified by de novo assembly, against the same 8 tissues uncovered several transcribed sequences with high expression in rods and/or S-cone like photoreceptors (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Tissue-specific expression of lncRNAs. Hierarchal clustering of RNA-seq data for (A) known lncRNAs and (B) unannotated lncRNAs, from mature rod and S-cone like photoreceptors (at P28) with eight adult tissues. Cell-specific expression clusters for rod and S-cone–like photoreceptors (marked as “Cone”), and both photoreceptor types (PR) are shown on the right.

Phase Shift in Global lncRNA Profile From P6 to P10

Hierarchical clustering of lncRNAs expressed in developing rods and S-cone–like photoreceptors revealed a major shift from P6 to P10 in previously annotated (Fig. 3A) and de novo–identified (Fig. 3B) transcripts. The correlation plot of developmental time points demonstrated lncRNA expression dynamics similar to the coding transcriptome, where we had observed a dramatic upregulation of rod–specific genes and downregulation of cone genes from P6 to P10 in WT rods and this shift was not detected in the absence of Nrl.45

Figure 3.

Dynamics of lncRNA expression during photoreceptor development. Cluster analyses of time series profiles highlight a transcriptome wide shift in expression between P6 and P10 for (A) known and (B) unannotated lncRNAs. This shift also is apparent in time point–based correlation matrix. Clusters with highly expressed genes in late stages (P10–P28) are shown on the right for rod and S-cone–like photoreceptors.

Clustering analysis of lncRNA expression data showed distinct patterns, which correlated to cellular identity and developmental stage. Therefore, we could classify lncRNAs for their specificity and potential relevance in rod morphogenesis and functional maturation. We identified previously annotated (Fig. 3A, right) and unannotated (Fig. 3B, right) lncRNAs that showed high expression in early (P2–P10) or late developmental (P10–P28) stages of rods and S-cone–like photoreceptors. For example, XLOC_041510, XLOC_006814, and XLOC_023678 are three previously unannotated rod-specific lncRNAs, whereas XLOC_061888, XLOC_025919, and XLOC_055417 represent lncRNAs showing high expression in late developmental stages of S-cone–like photoreceptors. The expression of another lncRNA, XLOC_032008, was detected in rods as well as S-cone–like photoreceptors.

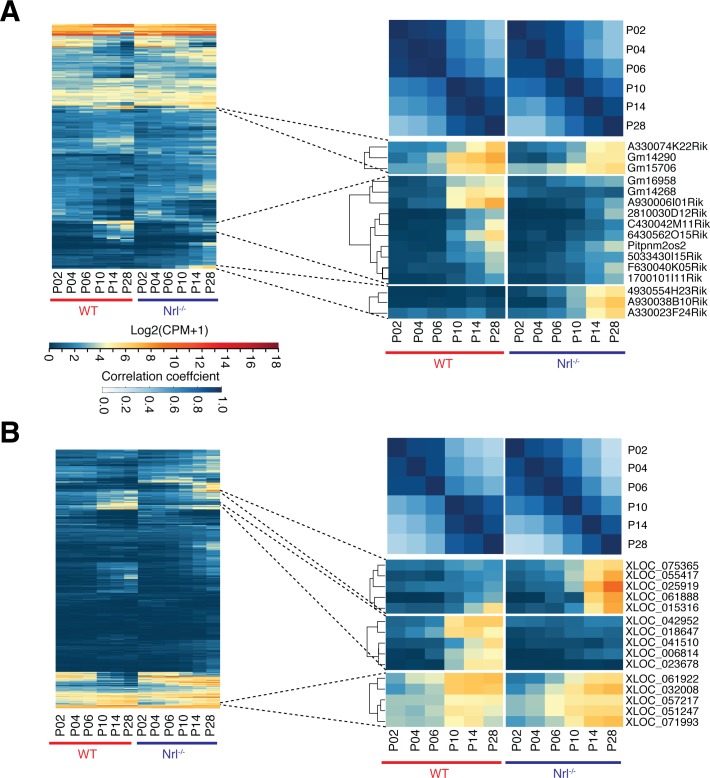

Photoreceptor-Enriched asRNAs

Transcriptome analysis identified 454 reported and 243 previously unannotated antisense (as) transcripts in developing photoreceptors; of these, Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV; available in the public domain at www.broadinstitute.org/igv)-based evaluation validated 232 and 96 lncRNAs, respectively. Most asRNAs were expressed at relatively low levels (log2FPKM <2) and exhibited a temporally restricted expression pattern (Figs. 4A, 4B); four of these (3 known and one unannotated) were validated by in situ hybridization (Supplementary Fig. S1). As in the case of lncRNAs, a sharp transition was observed in global asRNA expression between P6 and P10. Interestingly, among asRNAs exhibiting P6-to-P10 expression shift, a larger fraction showed higher expression in S-cone–like photoreceptors (Figs. 4A, 4B). Given that asRNAs may regulate the genes that they overlap with, we performed Pearson's correlation analysis of pairs of protein-coding transcripts and their corresponding asRNAs (known and unannotated). Since most mammalian genes have multiple transcripts, we investigated the correlation on a transcript level, yielding 1707 associations. We identified 174 asRNA-protein correlations (148 known and 26 unannotated respectively) with a positive (i.e., antisense and sense gene showing similar expression trends, P ≥ 0.75, P < 0.05) and 35 (30 known and 5 unannotated respectively) with a negative (i.e., antisense and sense gene showing opposite expression trends, P ≤ −0.75, P < 0.05) association. No such relationship was observed between 1498 (1188 known and 310 unannotated) asRNAs and their cognate sense RNAs (−0.75 < P < 0.75; Fig. 4C), suggesting a lack of direct functional nexus.

Figure 4.

asRNA in the developing photoreceptors. Expression profiles of (A) known asRNAs and (B) unannotated asRNAs. As in case of lncRNAs, a genome-wide shift of asRNA expression was detected between P6 and P10. Clustering analysis identified specific sets of asRNAs in early and late stages of development. (C) Frequency of correlation between asRNA and sense transcripts. Most pairs show low correlation scores (−0.75 < ρ < 0.75). (D) Unannotated asRNA XLOC_041669 correlates to isoform switching of Gpsm1. Schematic representation of gene and transcript structure of Gpsm1 and XLOC_041669 with histograms and read alignment for RNA-seq. The two exons of XLOC_041669 and the first exon of Gpsm1-003 transcript are marked by red and blue dashed boxes, respectfully (red indicates origin of reads on the negative and blue on the positive strand). Upregulation of XLOC_041669 (yellow) and transcript Gpsm1-003 (light blue) occurs between P6 and P10, in concurrence with down regulation of transcript Gpsm1-002 (purple).

Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the 143 genes overlapping with 152 known asRNAs revealed an enrichment of biological processes associated with eye morphogenesis and development (P < 0.01). Functional clustering showed transcriptional regulation being the most common feature (Supplementary Fig. S2). No statistically significant enrichment of a distinct biological process was apparent among 107 genes overlapping with the 96 unannotated asRNAs, but GO categories of nervous system development and transcriptional regulation were evident. Potential relevance of previously unannotated asRNAs to transcriptional regulation can be exemplified by XLOC_041669, which overlaps with G-protein signaling modulator 1 (Gpsm1) gene, which undergoes isoform switch during rod development (Fig. 4D). The long isoform Gpsm1-002 is dominant in early stages, whereas the short isoform Gpsm1-003 is highly expressed in later stages of rod maturation. The pattern of XLOC_041669 asRNA follows the expression of the short isoform showing upregulation after P6 (Fig. 4D). These studies suggest that asRNAs enriched in developing rods participate in modulating genes associated with signaling pathways, trafficking, and neural development.

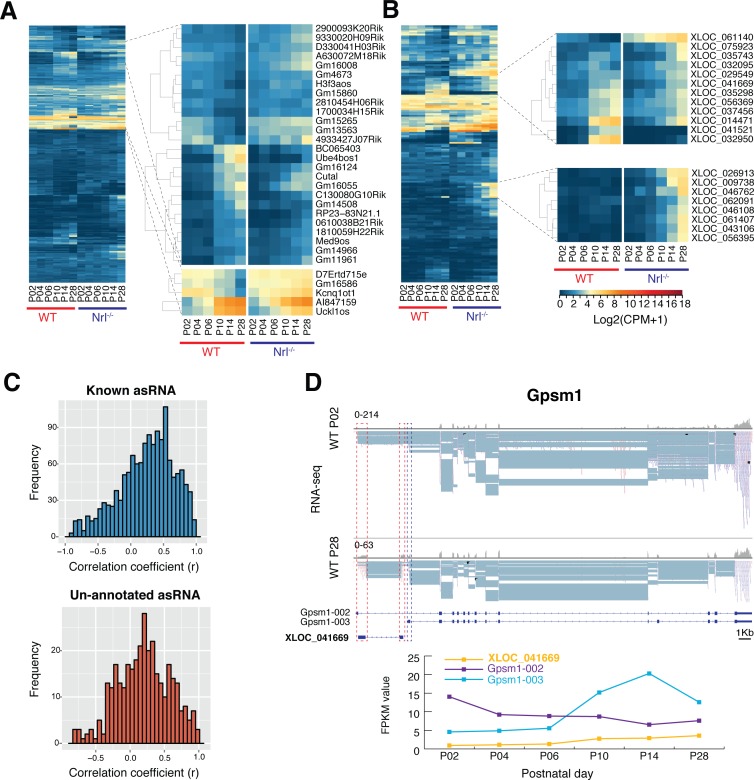

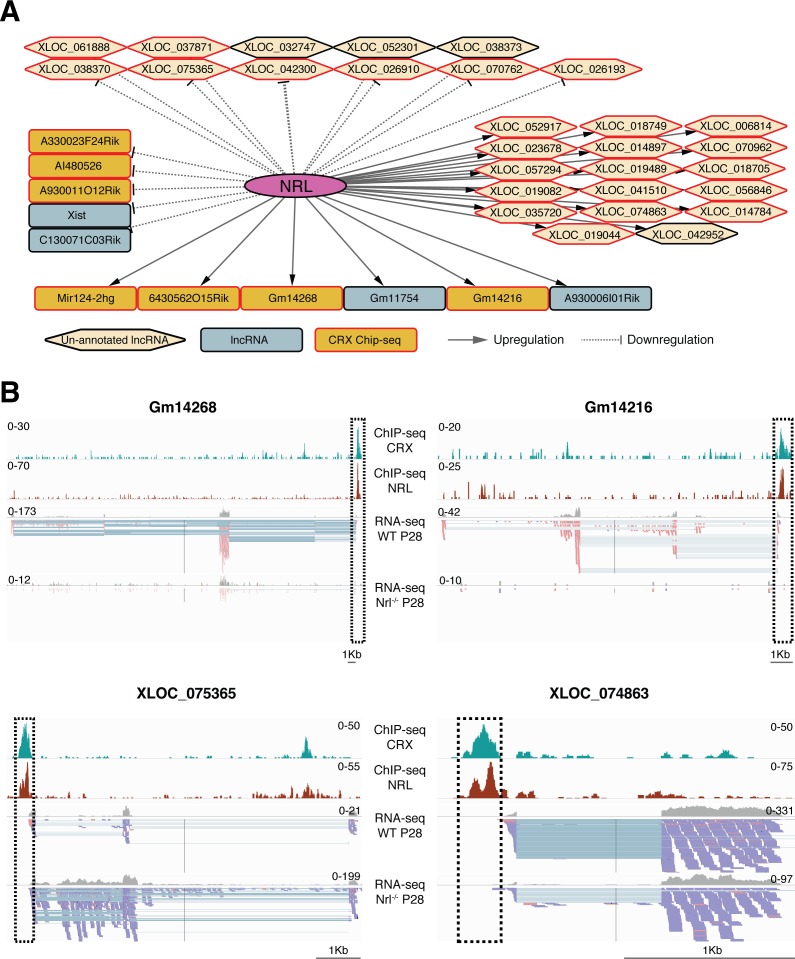

Regulation of Rod-Enriched lncRNAs by NRL

We hypothesized that NRL controls the expression of lncRNAs showing high enrichment in WT rods or S-cone–like Nrl−/− photoreceptors and that NRL-regulated genes are associated with rod development. Therefore, we examined lncRNAs that were differentially expressed in Nrl−/− photoreceptors (Supplementary Table S2) for significant NRL-chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) peaks43 to build a high confidence network of NRL-regulated genes. This strategy led to the identification of 119 lncRNA genes (39 known and 80 previously unannotated) that are putative direct targets of NRL (see Fig. 5A for top 50% genes). Expression of many lncRNAs was induced by NRL (e.g., Gm14268 and XLOC_074863) during rod development, whereas some of the target genes revealed high expression in S-cone-like Nrl−/− photoreceptors (e.g., A930011012Rik and XLOC_075365) suggesting transcriptional suppression by NRL (Figs. 5A, 5B). As CRX interacts with NRL and activates the expression of rod and cone genes, we evaluated differentially expressed photoreceptor lncRNAs for CRX ChIP-seq peaks in their genomic regions. Notably, approximately 70% of lncRNA genes within the NRL network also included significant CRX ChIP-seq peak in the putative promoter region, providing a strong support for their role in photoreceptors (Figs. 5A, 5B).

Figure 5.

Regulation of lncRNA expression by NRL. (A) NRL-centered lncRNA expression network. NRL targets represent lncRNAs that are differentially expressed in the RNA-seq data from WT rods vs Nrl−/− S-cone like photoreceptors and exhibit a significant NRL binding site within the putative promoter region. Only top 50% of network is represented here. (B) Schematic representation of the gene structure of two known (Gm14268 and Gm14216) and two unannotated lncRNA (XLOC_075365 and XLOC_074863) targets of NRL. The ChIP-seq peaks for NRL and CRX are shown by histograms (highlighted by dashed box) and overlap with the transcription start site (TSS) of the two genes, indicated in histograms for RNA-seq and individual sequence reads.

To validate ncRNA analysis, we performed in situ hybridization (ISH) experiments for 12 known and 12 previously unannotated lncRNAs (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. S3). All 24 lncRNAs showed differential expression between WT and Nrl−/− retina, consistent with their regulation by NRL; of these, 19 (79%) exhibited a specific or enriched expression in photoreceptors. The remaining five lncRNAs displayed a broader expression pattern in the retina, with somewhat higher expression in photoreceptors. Interestingly, 11 of the 12 de novo identified lncRNAs demonstrated specific expression in the photoreceptors (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Validation of lncRNA expression by ISH. White punctate dots represent the signal detected by the ISH probe, and blue shows DAPI staining of the nuclei. Scale bar: 50 μm. ONL, outer nuclear layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. A gene level expression plot is shown below every ISH image.

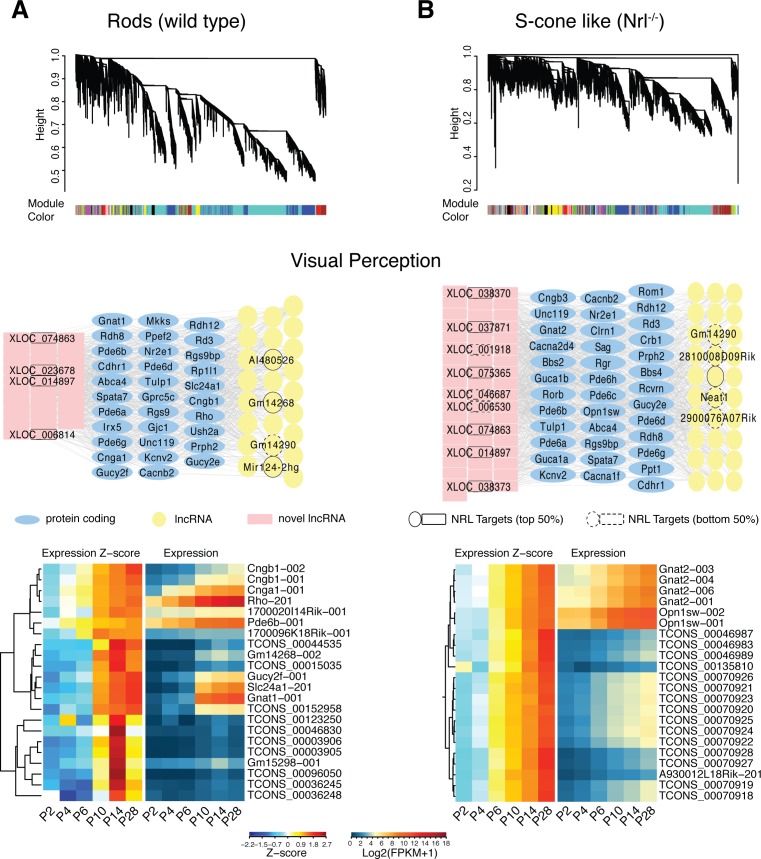

Clustering of lncRNAs With Photoreceptor-Expressed Protein-Coding Genes

We implemented the “guilt-by-association” approach63 to explore the relationship of expression patterns between ncRNAs and protein-coding genes. This approach assumes that coexpressed transcripts are more likely to be transcriptionally controlled by common regulators, and part of similar biological processes/pathways. We used weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) in R environment56 to identify lncRNAs having similar expression patterns as photoreceptor-expressed protein-coding genes (Fig. 7). Our analysis revealed 17 and 46 modules, respectively, in rod and S-cone–like photoreceptor datasets, with each module representing a group of highly connected transcripts. Individual modules were analyzed for GO term enrichment (Supplementary Fig. S4) on the protein-coding genes using DAVID (available in the public domain at https://david.ncifcrf.gov/). By focusing on modules enriched for GO terms associated with “visual perception” (Figs. 7A, 7B, middle), we identified 45 known and 74 previously unannotated lncRNAs, which highly correlate with 51 photoreceptor-enriched protein-coding genes.

Figure 7.

Construction of coexpression network modules and GO enrichment analysis. WGCNA clustering dendrogram is based on profiles of gene expression in (A) WT and (B) S-cone–like photoreceptors, which include 46 and 17 highly connected network modules, respectively. Each module is represented with a different color and includes protein-coding and noncoding genes. The network underneath the clustering dendrogram shows known and unannotated lncRNAs associated with the protein-coding genes having “visual perception” GO term. Known and unannotated lncRNAs that were identified as putative targets of NRL by ChIP-seq and differentiation expression analysis are annotated in the network. Top 50% of the targets nodes are shown with solid border and the lower 50% are with dashed border. Hierarchical Clustering of the standardized (z-score) expression profiles of genes in both networks identified a subset of lncRNAs that show early or late stage specific expression.

We then examined whether lncRNAs in the “visual perception” module overlapped with those presumed to be under NRL regulation. Almost one-fourth of the NRL regulated lncRNAs also were identified by WGCNA and associated with “visual perception.” Notably, additional 24 lncRNAs had ChIP-seq peaks for CRX within their putative promoter region. As coexpressed genes likely function in similar pathways, we performed clustering on a “visual perception” network to identify associated lncRNAs (Fig. 7, bottom). Gm14268 and XLOC_081898 are included with rod phototransduction genes (e.g., Rho, Gnat1, and Cngb1), whereas XLOC_038373 and XLOC_025824 clustered with Gnat2 and Opn1sw, two cone-specific genes.

Discussion

Evolution of intricate organization of specific cell types and tissues in mammals is inconsistent with the number of protein-coding genes in the genome.10,64,65 Organismic complexity generally has been associated with refinements in regulatory landscape and expansion of coding transcript repertoire, resulting in structural and functional diversity. More recent studies have revealed another key shift during genome evolution—a large increase in ncRNAs.66 While a handfull of neuron-specific transcriptomes have been described,46,67–70 we report the dynamics of noncoding transcriptome in developing and mature photoreceptors, especially focusing on rod-enriched lncRNAs and asRNAs that are under the influence of rod differentiation factor NRL. Together with the recently described coding transcriptome,45 our studies should help in the construction of more comprehensive gene regulatory networks that guide rod photoreceptor development.

A better understanding of functional divergence among neuronal subtypes is contingent upon elucidation of detailed transcriptional maps. Gencode and other databases11,71 have meager representation of ncRNAs from specific neurons, and little information is available about their regulation and function. Our comprehensive noncoding transcriptome analysis of the developing photoreceptors (WT rod and Nrl−/− S-cone like photoreceptors) not only has revealed 586 currently annotated lncRNAs and 454 antisense RNAs, but also identified 1037 additional lncRNAs and 243 asRNAs by de novo assembly. Interestingly, a large percentage of previously unannotated transcripts originated from S-cone–like cells, further underscoring the need for single cell type analysis to identify lncRNAs expressed in “true” pure cone cells because of their importance in human vision. As demonstrated by in situ hybridization studies, most de novo transcripts exhibited a rather photoreceptor-specific pattern of expression in contrast with the currently annotated lncRNAs that seem to be more widely expressed in the retina. Combined with the absence or low expression in other tissues examined, we suggest that these lncRNAs were missed in previous analysis, due to their unique cellular context and low expression levels.

One key finding of our analysis is the dramatic shift in noncoding transcriptome profile between P6 and P10 during rod development. A similar shift in the coding transcriptome45 was interpreted to have relevance in morphogenesis of outer segment membrane discs and synapse formation, which are initiated at or after P6 during mouse photoreceptor development. This suggests that coding and noncoding transcriptomes are under similar regulatory constraints, whether intrinsic or extrinsic, during rod photoreceptor differentiation. Such a shift in transcriptome was not detected in the absence of NRL. Therefore, we propose a regulatory role of rod-expressed and rod-specific lncRNAs and asRNAs in fine-tuning the expression of coding transcripts and/or proteins involved in establishment of photoreceptor morphology and function. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that 6% of known lncRNA transcripts are putative direct targets of NRL and that over 50% of these are differentially expressed between WT and Nrl−/− photoreceptors. Approximately 10% of previously unannotated lncRNAs are direct targets of NRL and 23% are differentially expressed. Additional evidence is provided by repeated occurrence of CRX binding sites in the promoter regions of these ncRNA. Regulation by NRL and CRX is highly concordant with photoreceptor-specific genes.43,45 We believe that incorporation of ncRNAs in the NRL-centered regulatory network would augment systems-based understanding of photoreceptor development.24

Biological functions of the vast majority of ncRNAs are not understood at this stage; however, lncRNAs and asRNAs are broadly implicated in different modes of regulation, either by direct interaction with other RNA molecules or proteins, or by acting directly on the genome. By implementing bioinformatic tools, such as WGCNA, to stratify the expression data, we have been able to identify lncRNAs that might contribute to distinct biological pathways. “Visual perception” associated lncRNAs were clustered in modules containing genes that participate in phototransduction cascade, and such genes represent almost 25% of the NRL regulated noncoding transcriptome. Our studies have begun to establish the framework for dissecting the function of lncRNAs, especially during the development of rod photoreceptors and highlight the significance of examining global noncoding transcriptome in a cell type–specific manner. A comprehensive description of transcriptome landscape and associated gene regulatory network provides a reference map to investigate photoreceptor biology with potential implications for human retinal disease and therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert Fariss for advice and assistance. This study used the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at National Institutes of Health (available in the public domain at ttp://biowulf.nih.gov).

Supported by Intramural Research Program of the National Eye Institute (EY000450 and EY000546).

Disclosure: L. Zelinger, None; G. Karakülah, None; V. Chaitankar, None; J.-W. Kim, None; H.-J. Yang, None; M.J. Brooks, None; A. Swaroop, None

References

- 1. Djebali S, Davis CA, Merkel A,et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. 2012; 489: 101– 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Katayama S, Tomaru Y, Kasukawa T,et al. Antisense transcription in the mammalian transcriptome. Science. 2005; 309: 1564– 1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Consortium EP, Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA,et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007; 447: 799– 816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ponjavic J, Ponting CP, Lunter G. . Functionality or transcriptional noise? Evidence for selection within long noncoding RNAs. Genome Res. 2007; 17: 556– 565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ponting CP, Belgard TG. . Transcribed dark matter: meaning or myth? Hum Mol Genet. 2010; 19: R162– R168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tsoi LC, Iyer MK, Stuart PE,et al. Analysis of long non-coding RNAs highlights tissue-specific expression patterns and epigenetic profiles in normal and psoriatic skin. Genome Biol. 2015; 16: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gloss BS, Dinger ME. . The specificity of long noncoding RNA expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016; 1859: 16– 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Quinn JJ, Chang HY. . Unique features of long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2016; 17: 47– 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rinn JL, Chang HY. . Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012; 81: 145– 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harrow J, Frankish A, Gonzalez JM,et al. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project. Genome Res. 2012; 22: 1760– 1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Derrien T, Johnson R, Bussotti G,et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 2012; 22: 1775– 1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Briggs JA, Wolvetang EJ, Mattick JS, Rinn JL, Barry G. . Mechanisms of long non-coding rnas in mammalian nervous system development, plasticity, disease, and evolution. Neuron. 2015; 88: 861– 877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ramos AD, Andersen RE, Liu SJ,et al. The long noncoding RNA Pnky regulates neuronal differentiation of embryonic and postnatal neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2015; 16: 439– 447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang H, Iacoangeli A, Popp S,et al. Dendritic BC1 RNA: functional role in regulation of translation initiation. J Neurosci. 2002; 22: 10232– 10241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zalfa F, Giorgi M, Primerano B,et al. The fragile X syndrome protein FMRP associates with BC1 RNA and regulates the translation of specific mRNAs at synapses. Cell. 2003; 112: 317– 327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernard D, Prasanth KV, Tripathi V,et al. A long nuclear-retained non-coding RNA regulates synaptogenesis by modulating gene expression. EMBO J. 2010; 29: 3082– 3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhao X, Tang Z, Zhang H,et al. A long noncoding RNA contributes to neuropathic pain by silencing Kcna2 in primary afferent neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2013; 16: 1024– 1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu B, Zhou S, Hu W,et al. Altered long noncoding RNA expressions in dorsal root ganglion after rat sciatic nerve injury. Neurosci Lett. 2013; 534: 117– 122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yao C, Wang J, Zhang H,et al. Long non-coding RNA uc.217 regulates neurite outgrowth in dorsal root ganglion neurons following peripheral nerve injury. Eur J Neurosci. 2015; 42: 1718– 1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vance KW, Sansom SN, Lee S,et al. The long non-coding RNA Paupar regulates the expression of both local and distal genes. EMBO. 2014; 33: 296– 311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guttman M, Rinn JL. . Modular regulatory principles of large non-coding RNAs. Nature. 2012; 482: 339– 346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Geisler S, Coller J. . RNA in unexpected places: long non-coding RNA functions in diverse cellular contexts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013; 14: 699– 712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lin S, Zhang L, Luo W, Zhang X. . Characteristics of antisense transcript promoters and the regulation of their activity. Int J Mol Sci. 2015; 23: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang HJ, Ratnapriya R, Cogliati T, Kim JW, Swaroop A. . Vision from next generation sequencing: multi-dimensional genome-wide analysis for producing gene regulatory networks underlying retinal development, aging and disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2015; 46: 1– 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bhattacharjee S, Zhao YH, Dua P, Rogaev EI, Lukiw WJ. microRNA-34a-mediated down-regulation of the microglial-enriched triggering receptor and phagocytosis-Sensor TREM2 in age-related macular degeneration. PLoS One. 2016; 11: e0153292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Karali M, Persico M, Mutarelli M,et al. High-resolution analysis of the human retina miRNome reveals isomiR variations and novel microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44: 1525– 1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ohana R, Weiman-Kelman B, Raviv S,et al. MicroRNAs are essential for differentiation of the retinal pigmented epithelium and maturation of adjacent photoreceptors. Development. 2015; 142: 2487– 2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Young TL, Matsuda T, Cepko CL. . The noncoding RNA taurine upregulated gene 1 is required for differentiation of the murine retina. Curr Biol. 2005; 15: 501– 512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rapicavoli NA, Poth EM, Blackshaw S. . The long noncoding RNA RNCR2 directs mouse retinal cell specification. BMC Dev Biol. 2010; 10: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krol J, Krol I, Alvarez CP,et al. A network comprising short and long noncoding RNAs and RNA helicase controls mouse retina architecture. Nat Commun. 2015; 6: 7305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alfano G, Vitiello C, Caccioppoli C,et al. Natural antisense transcripts associated with genes involved in eye development. Hum Mol Genet. 2005; 14: 913– 923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saito R, Yamasaki T, Nagai Y,et al. CrxOS maintains the self-renewal capacity of murine embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009; 390: 1129– 1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meola N, Pizzo M, Alfano G, Surace EM, Banfi S. . The long noncoding RNA Vax2os1 controls the cell cycle progression of photoreceptor progenitors in the mouse retina. RNA. 2012; 18: 111– 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mustafi D, Kevany BM, Bai X,et al. Evolutionarily conserved long intergenic non-coding RNAs in the eye. Hum Mol Genet. 2013; 22: 2992– 3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lamb TD. . Evolution of phototransduction, vertebrate photoreceptors and retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2013; 36: 52– 119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Swaroop A, Kim D, Forrest D. . Transcriptional regulation of photoreceptor development and homeostasis in the mammalian retina. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010; 11: 563– 576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cepko C. . Intrinsically different retinal progenitor cells produce specific types of progeny. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014; 15: 615– 627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brzezinski JA, Reh TA. . Photoreceptor cell fate specification in vertebrates. Development. 2015; 142: 3263– 3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mears AJ, Kondo M, Swain PK,et al. Nrl is required for rod photoreceptor development. Nat Genet. 2001; 29: 447– 452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Oh EC, Khan N, Novelli E, Khanna H, Strettoi E, Swaroop A. . Transformation of cone precursors to functional rod photoreceptors by bZIP transcription factor NRL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007; 104: 1679– 1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim JW, Yang HJ, Oel AP,et al. Recruitment of Rod photoreceptors from short-wavelength-sensitive cones during the evolution of nocturnal vision in mammals. Dev Cell. 2016; 37: 520– 532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Corbo JC, Lawrence KA, Karlstetter M,et al. CRX ChIP-seq reveals the cis-regulatory architecture of mouse photoreceptors. Genome Res. 2010; 20: 1512– 1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hao H, Kim DS, Klocke B,et al. Transcriptional regulation of rod photoreceptor homeostasis revealed by in vivo NRL targetome analysis. PLoS Genet. 2012; 8: e1002649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hennig AK, Peng GH, Chen S. . Regulation of photoreceptor gene expression by Crx-associated transcription factor network. Brain Res. 2008; 1192: 114– 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim JW, Yang, HJ, Brooks, MJ,et al. NRL-regulated transcriptome dynamics of developing rod photoreceptors. Cell Rep. 2016; 17: 2460– 2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Akimoto M, Cheng H, Zhu D,et al. Targeting of GFP to newborn rods by Nrl promoter and temporal expression profiling of flow-sorted photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006; 103: 3890– 3895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Brooks MJ, Rajasimha HK, Swaroop A. . Retinal transcriptome profiling by directional next-generation sequencing using 100 ng of total RNA. Methods Mol Biol. 2012; 884: 319– 334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. . TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013; 14: R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G,et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010; 28: 511– 515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J,et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42: D222– 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Langmead B, Salzberg SL. . Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012; 9: 357– 359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D,et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43: e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010; 26: 139– 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Robinson MD, Oshlack A. . A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010; 11: R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Soneson C, Love MI, Robinson MD. . Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Res. 2015; 4: 1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Langfelder P, Horvath S. . WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008; 9: 559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009; 4: 44– 57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ciofani M, Madar A, Galan C,et al. A validated regulatory network for Th17 cell specification. Cell. 2012; 151: 289– 303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ouyang Z, Zhou Q, Wong WH. . ChIP-Seq of transcription factors predicts absolute and differential gene expression in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009; 106: 21521– 21526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Marbach D, Costello JC, Kuffner R,et al. Wisdom of crowds for robust gene network inference. Nat Methods. 2012; 9: 796– 804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Consortium EP. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012; 489: 57– 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pervouchine DD, Djebali S, Breschi A,et al. Enhanced transcriptome maps from multiple mouse tissues reveal evolutionary constraint in gene expression. Nat Commun. 2015; 6: 5903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Stuart JM, Segal E, Koller D, Kim SK. . A gene-coexpression network for global discovery of conserved genetic modules. Science. 2003; 302: 249– 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Prachumwat A, Li WH. . Gene number expansion and contraction in vertebrate genomes with respect to invertebrate genomes. Genome Res. 2008; 18: 221– 232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Shabalina SA, Ogurtsov AY, Spiridonov NA, Koonin EV. . Evolution at protein ends: major contribution of alternative transcription initiation and termination to the transcriptome and proteome diversity in mammals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42: 7132– 7144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Necsulea A, Soumillon M, Warnefors M,et al. The evolution of lncRNA repertoires and expression patterns in tetrapods. Nature. 2014; 505: 635– 640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Siegert S, Cabuy E, Scherf BG,et al. Transcriptional code and disease map for adult retinal cell types. Nat Neurosci. 2012; 15: 487– 495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA,et al. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2014; 34: 11929– 11947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R,et al. Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell. 2015; 161: 1202– 1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Telley L, Govindan S, Prados J,et al. Sequential transcriptional waves direct the differentiation of newborn neurons in the mouse neocortex. Science. 2016; 351: 1443– 1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhao Y, Yuan J, Chen RS. . NONCODEv4: annotation of noncoding RNAs with emphasis on long noncoding RNAs. Methods Mol Biol. 2016; 1402: 243– 254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.