Abstract

Zinc and copper are essential trace elements. Dyshomeostasis in these two metals has been observed in Alzheimer’s disease, which causes profound cognitive impairment. Insulin therapy has been shown to enhance cognitive performance; however, recent data suggest that this effect may be at least in part due to the inclusion of zinc in the insulin formulation used. Zinc plays a key role in regulation of neuronal glutamate signaling, suggesting a possible link between zinc and memory processes. Consistent with this, zinc deficiency causes cognitive impairments in children. The effect of zinc supplementation on short- and long-term recognition memory, and on spatial working memory, was explored in young and adult male Sprague Dawley rats. After behavioral testing, hippocampal and plasma zinc and copper were measured. Age increased hippocampal zinc and copper, as well as plasma copper, and decreased plasma zinc. An interaction between age and treatment affecting plasma copper was also found, with zinc supplementation reversing elevated plasma copper concentration in adult rats. Zinc supplementation enhanced cognitive performance across tasks. These data support zinc as a plausible therapeutic intervention to ameliorate cognitive impairment in disorders characterized by alterations in zinc and copper, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: Zinc, copper, memory, hippocampus

1. Introduction

Zinc regulates many cellular processes, acting as a co-factor for more than 300 enzymes [1–8]. With only 2–4g of zinc within the adult human body, concentration of zinc is tightly regulated [9]. Within the brain, zinc is concentrated in the limbic system[2, 6, 10], predominantly in the hippocampus and amygdala [2, 11–13]; the hippocampus is the only brain area in which zinc increases markedly during development [14]. Zinc deficiency impairs cognitive and motor function in children [15, 16] and damages the blood brain barrier [17], but less is known about the relationship between zinc and adult memory. Disturbances in zinc homeostasis have been associated with aging [18], Type II Diabetes (T2D)[9, 19–22], and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)[23–35], and this zinc dysregulation may contribute to the cognitive dysfunction seen in these disease states [36].

Zinc is co-secreted with glutamate. Zinc-containing glutamatergic neurons are dense in the mossy fibre layer of the hippocampus [1, 5, 37, 38]: a zinc-deficient diet causes reduced neurogenesis and increased neuronal apoptosis within the hippocampus [39–42]. Vesicular zinc has recently been shown to be critical for hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) with both presynaptic and postsynaptic actions [43]. After secretion, zinc modulates postsynaptic excitability at NMDA [44–47], dopamine [48], and GABA receptors [49, 50]; zinc also modulates the Erk1/2 mitogen-activated-protein kinase (MAPK) pathway[51, 52], brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)[10, 53, 54] and glucose metabolism [55, 56]. An additional zinc-dependent enzyme recently identified as a potential modulator of hippocampal learning and memory is insulin-regulated aminopeptidase (IRAP) [57–60].

Since it was shown that zinc is a component of insulin crystals [61], a relationship between zinc and insulin signaling, a pathway known to impact learning and memory [62–64], has been proposed. More specifically, zinc causes tyrosine phosphorylation of the β subunit of the insulin receptor, increases phosphorylation of Akt serine residues and therefore activation of Akt, and induces an increase in glucose transport into cells via GLUT4 translocation [9, 65–67].

Despite these several known effects of hippocampal zinc, zinc’s role in adult cognitive impairment has not been extensively explored. Reduced zinc signaling produced by knock-out of the ZnT3 zinc transporter (responsible for packaging of vesicular zinc) produces cognitive impairment in 6 month-old mice, accompanied by marked glutamatergic dysfunction and a decrease in total dendritic spines per neuron [26] but this cognitive impairment was, interestingly, absent in young (6–10 week old) ZnT3 KO mice, suggesting that zinc regulation may be especially important in adult or aged brains.

Recent research [68, 69] suggests a possible link between zinc and a second essential micronutrient, copper, in the development and/or progression of Alzheimer’s disease [30, 33, 70–76]. Copper can be toxic when in excess by contributing to oxidative stress [77]. Given this possible link, we measured both brain and plasma copper following zinc administration. Our overall hypothesis was that zinc supplementation might enhance hippocampally-mediated cognitive function, possibly via modulation of copper levels; and that this effect would be seen more clearly in adult rats than in young rats.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

Male Sprague Dawley rats (N=40; Charles River, Wilmington, MA), either 8-weeks-old (young group) or 24 weeks old (adult group), were pair-housed on a 12:12 h light:dark schedule with food and water available ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the University at Albany Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All rats were allowed to acclimate for at least one week prior to treatment. Animals were handled routinely from the time of their arrival by the experimenters to minimize any effects of handling stress on experimental measurements.

2.2 Zinc supplementation

Animals were randomly assigned to either regular drinking water or zinc-supplemented drinking water (75 mg/L elemental zinc) for two-weeks prior to behavioral testing. Animals remained on their assigned treatments during the behavioral testing schedule, totaling three weeks of treatment at the time of brain and blood collection.

2.3 Behavioral testing

Open Field

Animals first completed an Open Field (OF) task. OF testing involved placing the animal into an open arena for 5 minutes. Time spent in the center zone and outer zone of the arena is recorded, with increased time in the center zone indicating lower anxiety. This task also served as a habituation trial for subsequent novel object recognition testing. The OF apparatus was cleaned with 70% ethanol in-between trials, ensuring no carry-over effects of scent influenced subsequent testing.

Novel Object Recognition

Thirty minutes after performing OF, animals performed Novel Object Recognition (NOR) to assess short- and long-term recognition memory. NOR testing involved placing the animals back into the open arena used in OF testing for three more 5-minute trials. During the first trial, two identical objects were placed in the center zone and total time exploring both objects was recorded. Thirty minutes later, one of the identical objects was replaced with a novel object and the animals were returned to the behavioral apparatus. Time spent exploring the novel object as a percentage of total exploration time was calculated as 30-minute novel object recognition. Twenty-four hours later, the animals were returned to the behavioral apparatus a second time, and a different novel object again replaced one of the identical objects seen during acquisition; a 24-hour novel object recognition score was calculated in the same way. Higher scores are interpreted as indicating increased recognition memory. The objects used during NOR testing included a pair of water-filled 500 mL conical bottles, an opaque white teacup, and laboratory goggles. The OF apparatus and objects were cleaned with 70% ethanol in-between trials, ensuring no carry-over effects of scent influenced subsequent testing.

Spontaneous Alternation

Forty-eight hours after completing NOR, animals were tested on the 4-arm Spontaneous Alternation (SA) spatial working memory task [62, 78, 79]. This task is known to be sensitive to alterations in hippocampal metabolism and insulin signaling [63, 80–84]. Animals were placed in a 4-arm plus-shaped maze in which the animals utilized spatial cues to guide behavior. Alternation was calculated as the percentage successful alternations (entering each arm at least once in 5 attempts) of total possible alternations (number of arm entries minus four). Higher alternation scores indicate increased spatial working memory. The SA apparatus was cleaned with 70% ethanol in-between trials, ensuring no carry-over effects of scent influenced subsequent testing.

2.4 Atomic Absorption Analysis

Trunk blood and hippocampal tissue were collected at the time of sacrifice. Blood was immediately spun down and separated for plasma while hippocampi were removed and immediately homogenized and fixed in protease and phosphatase inhibitor buffers to prepare the tissue for atomic absorption (AA; Aurora Biomed Trace AI 1200) analyses. Plasma and homogenate were diluted with HPLC grade water to reduce background absorption. Zinc and cooper concentrations were quantified using associated software relative to respective standard curves.

2.5 Statistical Analyses

A 2 × 2 (age × treatment) ANOVA assessed the effects of age (8-weeks vs. 24-weeks) and treatment (control vs. zinc-supplemented), and the interaction of age and treatment, on open field, novel object recognition at 30-minute and 24-hour latency, and spontaneous alternation. A separate 2 × 2 (age × treatment) ANOVA assessed effects on plasma zinc, hippocampal zinc, plasma copper, and hippocampal copper. Significant main effects and interactions were further examined using post-hoc pairwise comparisons.

Statistical outliers were defined as falling more than two standard deviations from the mean for behavioral and biological analyses. If an animal was determined an outlier during the acquisition phase of NOR, subsequent trials (30-minute and 24-hour latency) were also removed from analyses (N=5). If an animal was removed at any point during behavioral testing, it was also removed for biological analysis (N=7; N=1 removed from OF, N=5 from NOR, N=1 from SA). Samples that fell outside of the standard curve range during biological analysis and/or were more than two standard deviations from the mean were also removed (N=6). One 24-week-old animal was removed from the study prior to treatment due to health problems, resulting in a total of N=39 for behavioral and biological analyses prior to removal of statistical outliers and samples that fell outside of the standard curve. Group sizes for each analysis are as follows, Young Control: Open Field n=10, NOR n =8, SA n=10, Plasma Zinc n=8, Plasma Copper n=8, Brain Zinc n=8, Brain Copper n=8; Young Zinc: Open Field n=9, NOR n =10, SA n=10, Plasma Zinc n=7, Plasma Copper n=7, Brain Zinc n=7, Brain Copper n=7; Adult Control: Open Field n=10, NOR n =9, SA n=10, Plasma Zinc n=6, Plasma Copper n=6, Brain Zinc n=7, Brain Copper n=7; Adult Zinc: Open Field n=9, NOR n =7, SA n=8, Plasma Zinc n=6, Plasma Copper n=7, Brain Zinc n=7, Brain Copper n=7. Alpha was set at 0.05; data are shown as group means +/− SEM.

3. Results

3.1 Behavioral Results

Open Field

No effect of age or treatment on performance in the open field task was seen (all p > .05). Group mean times (+/− SEM) spent in the center zone were: Young Control 7.51 +/−2.03 seconds, Young Zinc 5.00 +/− 1.82 seconds, Adult Control 7.29 +/− 1.11 seconds, Adult Zinc 10.17 +/− 2.15 seconds (data not shown).

Novel Object Recognition

There was no effect of age or treatment, nor their interaction, on time spent exploring objects during acquisition (all p > .05; Figure 1A). Young Control: M = 55.13 seconds, S.E.M. = 7.13 seconds, Young Zinc: M = 49.76 seconds, S.E.M. = 6.00 seconds, Adult Control: M = 41.64 seconds, S.E.M. = 7.36 seconds, Adult Zinc: M =46.56 seconds, S.E.M. = 7.91 seconds.

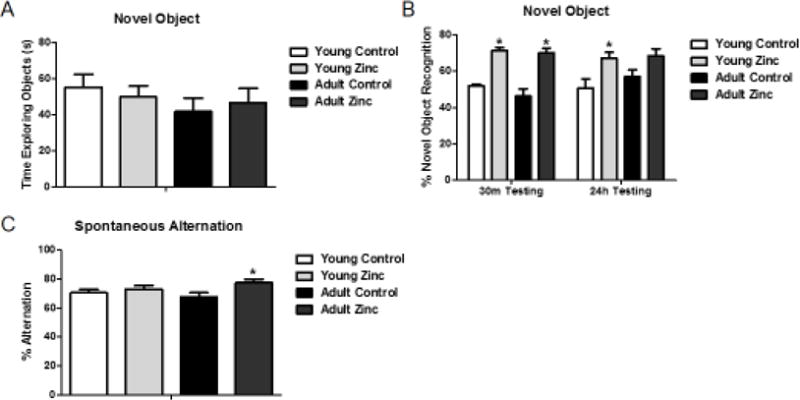

Figure 1. Cognitive performance.

(A) Time spent exploring objects during novel object recognition acquisition. No group differences were seen, nor were there overall effects of age or treatment. (B) Percent time spent with novel object during testing after a 30min or 24h delay. (C) Percent spontaneous alternation (SA) performance on the 4-arm SA task. Asterisks indicate significant pair-wise differences (p < .05) between control and zinc-treated conditions for that group. Data shown as mean +/− SEM.

A main effect of treatment was found at both 30-min (F(1,29) = 68.258, p < .05), and 24-hour latencies F(1,29) = 11.275, p < .05 (Figure 1B) on percent novel object recognition. Pairwise post-hoc comparisons confirmed a significant increase in percent novel object recognition after zinc treatment at both 30-minute and 24-hour latencies in the young group, and at the 30-minute latency in the aged group (p = 0.066 for the 24-hour latency). There was no significant interaction between age and treatment.

Spontaneous Alternation

No main effect of age or treatment or interaction of age and treatment on percent spontaneous alternation was seen (Figure 1C), F(1,29) = .093, p > .05 and F(1,29) = 3.128, p > .05; however, although there was no significant effect of treatment (F(1,29) = 3.128, p = .087), a pairwise comparison revealed a significant effect of zinc in the adult cohort (p = .036) with zinc treatment improving percent spontaneous alternation.

3.2 Atomic Absorption Results

Zinc Concentration

There was a main effect of age on plasma and hippocampal zinc concentration (F(1,23) = 4.830, p < .05 and F(1,23) = 7.636, p < .05, respectively; Figure 2A). 24-week-old animals had decreased plasma zinc and increased hippocampal zinc, relative to 8-weeks-old, indicating an age-dependent effect on zinc status. There was no significant interaction between age and treatment. Surprisingly, there was no significant effect of zinc treatment on either plasma or hippocampal zinc levels.

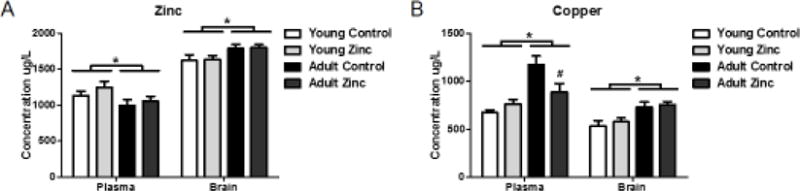

Figure 2. Zinc and copper measurements.

(A) Across treatment conditions, age decreased plasma zinc and increased hippocampal zinc. No effect of zinc treatment was seen on either measure. (B) Age increased both plasma and hippocampal copper. In addition, pair-wise comparison showed that zinc treatment attenuated the age-related increase in plasma copper. Asterisks indicate significant (p < .05) effects of age across treatment condition; # indicates significant effect of zinc treatment on plasma copper in the adult animals. Data shown as mean +/− SEM.

Copper Concentration

There was a main effect of age on plasma and hippocampal copper concentration (F(1, 23) = 19.037, p < .05 and F(1,23) = 20.827, p < 0.05, respectively; Figure 2B). 24-week-old animals had higher plasma and hippocampal copper levels. Interestingly, results also indicated a significant interaction between the two factors (F(1,23) = 7.817, p < .05), with zinc treatment reducing plasma, but not hippocampal, copper in the 24-week-old animals.

4. Discussion/Conclusion

We show that zinc supplementation enhanced both (i) short- and long-term recognition memory in young rats and short-term recognition memory in adult rats, and (ii) spatial working memory in adult rats. The role of zinc in mnemonic processing has been previously explored [85–88], but this is the first report we are aware of showing an effect of zinc supplementation to enhance memory above baseline.

We also saw increased plasma copper and hippocampal zinc and copper in our adult rats compared to the young animals. Surprisingly, our zinc supplementation did not affect hippocampal or plasma zinc concentrations. One possibility is that reversal of elevated plasma copper by zinc supplementation may contribute to cognitive enhancement, at least in the adult cohort, as excess copper is known to catalyze the formation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals, initiate oxidative damage, and interfere with important cellular events [89]. However, zinc also enhanced NOR in the young animals without affecting plasma copper, indicating that there must be additional or secondary effect(s) of zinc treatment beyond that of copper.

Interestingly, while zinc concentration in the brain increases with growth after birth and is maintained constant in the adult brain [90], turnover of zinc in the brain is very slow [91–93], which may help to explain why our two-week supplementation did not significantly alter brain zinc concentration. Consistent with our findings, it was recently shown that a 6-month oral zinc supplementation also had no effect on brain zinc, but did significantly reduce brain copper and amyloid burden in Tg2576 mice [69].

Future studies should include additional measurements of animal weight and water consumption before and during zinc supplementation to understand how possible changes in appetite and/or aversion toward zinc-treated water might produce secondary nutritional effects that could impact memory. These measurements would also aid in determining relative dosing of zinc over the course of a study. Additionally, administration of isotopically enriched zinc would elucidate the transport of zinc supplementation into the brain and determine whether age-related differences in transport exist.

In a prior study of zinc supplementation in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, treatment both improved cognitive performance and reduced serum copper [30], similar to our data. AD patients show increased serum and plasma copper relative to aged-matched controls [94, 95], and are zinc-deficient [68]. Patients with AD show high levels of both copper and zinc in cerebrospinal fluid and in amyloid plaques analyzed post-mortem [96, 97]. Taken together with the prior literature, our data in healthy animals suggest the possibility that zinc may be considered as a cognitive enhancer and possible therapeutic for the treatment of cognitive impairment seen in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Highlights.

-

-

Dyshomeostasis in trace metals such as zinc and copper impact cellular and cognitive processing.

-

-

Zinc supplementation enhances short- and long-term recognition and spatial working memory.

-

-

Hippocampal zinc and copper and plasma copper significantly increase with age.

-

-

Zinc supplementation reverses age-related elevations in plasma copper.

-

-

Zinc supplementation can be considered a plausible cognitive enhancing agent and/or therapeutic for cognitive dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this manuscript wish to thank Dr. Margot Vigeant (Department of Chemical Engineering) and Huan Luong (Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering) at Bucknell University for their expertise and the use of their laboratory space and atomic absorption spectroscopy. Support provided by Psi Chi and the University at Albany Benevolent Association to LAS, and by NIDDK R01 077106 to ECM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sandstead HH, Frederickson CJ, Penland JG. History of Zinc as related to brain function. Journal of Nutrition. 2000;130:496–502. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.496S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeda A. Movement of zinc and its functional significance in the brain. Brain Research Reviews. 2000;34:137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frederickson CJ, Koh JY, Bush AI. The neurobiology of zinc in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(6):449–62. doi: 10.1038/nrn1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sekler I, et al. Mechanism and regulation of cellular zinc transport. Mol Med. 2007;13(7–8):337–43. doi: 10.2119/2007-00037.Sekler. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakashima AS, Dyck RH. Zinc and cortical plasticity. Brain Res Rev. 2009;59(2):347–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sensi SL, et al. Zinc in the physiology and pathology of the CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(11):780–91. doi: 10.1038/nrn2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levenson CW, Morris D. Zinc and neurogenesis: making new neurons from development to adulthood. Adv Nutr. 2011;2(2):96–100. doi: 10.3945/an.110.000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sensi SL, et al. The neurophysiology and pathology of brain zinc. J Neurosci. 2011;31(45):16076–85. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3454-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansen J, Karges W, Rink L. Zinc and diabetes–clinical links and molecular mechanisms. J Nutr Biochem. 2009;20(6):399–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toth K. Zinc in neurotransmission. Annu Rev Nutr. 2011;31:139–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeda A, Tamano H. Insight into zinc signaling from dietary zinc deficiency. Brain Res Rev. 2009;62(1):33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeda A, et al. Increases in extracellular zinc in the amygdala in acquisition and recall of fear experience and their roles in response to fear. Neuroscience. 2010;168(3):715–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeda A. Zinc signaling in the hippocampus and its relation to pathogenesis of depression. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crawford IL, Connor JD. Zinc and Hippocampal Function. Orthomolecular Psychiatry. 1975;4(1):39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black MM. The evidence linking zinc deficiency with children’s cognitive and motor functioning. J Nutr. 2003;133(5 Suppl 1):1473S–6S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1473S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandstead HH. Subclinical zinc deficiency impairs human brain function. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2012;26(2–3):70–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noseworthy MD, Bray TM. Zinc deficiency exacerbates loss in blood-brain barrier integrity induced by hyperoxia measured by dynamic MRI. PSEBM. 2000;223:175–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haase H, Rink L. The immune system and the impact of zinc during aging. Immun Ageing. 2009;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinlaw WB, et al. Abnormal zinc metabolism in type II diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 1983;75(2):273–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salguiro MJ, et al. Zinc and diabetes mellitus - Is there a need of zinc supplementaiton in diabetes mellitus patients? Biological Trace Element Research. 2001;81:215–228. doi: 10.1385/BTER:81:3:215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chausmer AB. Zinc, insulin and diabetes. J Am Coll Nutr. 1998;17(2):109–15. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1998.10718735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miao X, et al. Zinc homeostasis in the metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Frontiers in Medicine. 2013;7(1):31–52. doi: 10.1007/s11684-013-0251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovell MA. A potential role for alterations of zinc and zinc transport proteins in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16(3):471–83. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuajungco MP, Faget KY. Zinc takes the center stage: its paradoxical role in alzheimer’s disease. Brain Research Reviews. 2003;41:44–56. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardoso SM, et al. Protective effect of zinc on amyloid-B 25–35 and 1–40 mediated toxicity. Neurotoxicity Research. 2005;7(4):273–282. doi: 10.1007/BF03033885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adlard PA, et al. Cognitive loss in zinc transporter-3 knock-out mice: a phenocopy for the synaptic and memory deficits of Alzheimer’s disease? J Neurosci. 2010;30(5):1631–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5255-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyubartseva G, et al. Alterations of zinc transporter proteins ZnT-1, ZnT-4 and ZnT-6 in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease brain. Brain Pathol. 2010;20(2):343–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watt NT, Whitehouse IJ, Hooper NM. The role of zinc in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;2011:971021. doi: 10.4061/2011/971021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corona C, et al. New therapeutic targets in Alzheimer’s disease: brain deregulation of calcium and zinc. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e176. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brewer GJ. Copper excess, zinc deficiency, and cognition loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Biofactors Special Issue: Biofactor and Cognitive Function. 2012;38(2):107–113. doi: 10.1002/biof.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kenche VB, Barnham KJ. Alzheimer’s disease & metals: therapeutic opportunities. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163(2):211–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Craddock TJA, et al. The Zinc Dyshomeostasis Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crouch PJ, Barnham KJ. Therapeutic Redistribution of Metal Ions To Treat Alzheimer’s Disease. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2012;45(9):1604–1611. doi: 10.1021/ar300074t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bush AI. The Metal Theory of Alzheimer’s Disease. The Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2013;33(Supplement 1):S277–S281. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hancock SM, Finkelstein DI, Adlard PA. Glia and zinc in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease: a mechanism for cognitive decline? Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:137. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeda A, Tamano H. Cognitive decline due to excess synaptic Zn(2+) signaling in the hippocampus. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:26. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haug FM. Electron microscopical localization of the zinc in hippocampal mossy fibre synapses by a modified sulfide silver procedure. Histochemie. 1967;8(4):355–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00401978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sato SM, Frazier JM, Goldberg AM. The distribution and binding of zinc in the hippocampus. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1984;4(6):1662–1670. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-06-01662.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao HL, et al. Zinc deficiency reduces neurogenesis accompanied by neuronal apoptosis through caspase-dependent and -independent signaling pathways. Neurotox Res. 2009;16(4):416–25. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandstead HH. Causes of Iron and Zinc Deficiences and Their Effects on Brain. The Journal of Nutrition. 2000;130:347S–349S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.347S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corniola RS, et al. Zinc deficiency impairs neuronal precursor cell proliferation and induces apoptosis via p53-mediated mechanisms. Brain Res. 2008;1237:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu X, et al. Effects of maternal mild zinc deficiency and zinc supplementation in offspring on spatial memory and hippocampal neuronal ultrastructural changes. Nutrition. 2013;29(2):457–61. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan E, et al. Vesicular zinc promotes presynaptic and inhibits postsynaptic long-term potentiation of mossy fiber-CA3 synapse. Neuron. 2011;71(6):1116–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paoletti P, Ascher P, Neyton J. High-Affinity Zinc Inhibition of NMDA NR1–NR2A Receptors. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17(15):5711–5725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05711.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erreger K, Traynelis SF. Allosteric interaction between zinc and glutamate binding domains on NR2A causes desensitization of NMDA receptors. J Physiol. 2005;569(Pt 2):381–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rachline J, et al. The micromolar zinc-binding domain on the NMDA receptor subunit NR2B. J Neurosci. 2005;25(2):308–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3967-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Erreger K, Traynelis SF. Zinc inhibition of rat NR1/NR2A N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Physiol. 2008;586(3):763–78. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner TY, Soliman MRI. Effects of zinc on spatial reference memory and brain dopamine (D1) receptor binding kinetics in rats. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacological & Biological Psychiatry. 2000;24:1203–1217. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(00)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qian J, Noebels JL. Visualization of transmitter release with zinc fluorescence detection at the mouse hippocampal mossy fibre synapse. J Physiol. 2005;566(Pt 3):747–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang EP. Metal ions and synaptic transmission: Think zinc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13386–13387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sindreu C, Palmiter RD, Storm DR. Zinc transporter ZnT-3 regulates presynaptic Erk1/2 signaling and hippocampus-dependent memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(8):3366–3370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019166108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nuttall JR, Oteiza PI. Zinc and the ERK kinases in the developing brain. Neurotox Res. 2012;21(1):128–41. doi: 10.1007/s12640-011-9291-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sindreu C, Storm DR. Modulation of neuronal signal transduction and memory formation by synaptic zinc. Front Behav Neurosci. 2011;5:68. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Corona C, et al. Dietary zinc supplementation of 3xTg-AD mice increases BDNF levels and prevents cognitive deficits as well as mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e91. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vardatsikos G, Pandey NR, Srivastava AK. Insulino-mimetic and anti-diabetic effects of zinc. J Inorg Biochem. 2013;120:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Capdor J, et al. Zinc and glycemic control: a meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled supplementation trials in humans. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2013;27(2):137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Albiston AL, et al. Alzheimer’s, Angiotensin IV and an Aminopeptidase. Biological Pharmacology Bullentin. 2004;27(6):765–767. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chai SY, et al. Development of cognitive enhancers based on inhibition of insulin-regulated aminopeptidase. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9(Suppl 2):S14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-S2-S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andersson H, Hallberg M. Discovery of inhibitors of insulin-regulated aminopeptidase as cognitive enhancers. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:789671. doi: 10.1155/2012/789671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Albiston AL, et al. Identification and development of specific inhibitors for insulin-regulated aminopeptidase as a new class of cognitive enhancers. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(1):37–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott DA. Crystalline insulin. Biochem J. 1934;28(4):1592–1602. doi: 10.1042/bj0281592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McNay EC, Fries TM, Gold PE. Decreases in rat extracellular hippocampal glucose concentration associated with cognitive demand during a spatial task. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(6):2881–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050583697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McNay EC, et al. Hippocampal memory processes are modulated by insulin and high-fat-induced insulin resistance. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2010;93(4):546–53. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stern SA, Chen DY, Alberini CM. The effect of insulin and insulin-like growth factors on hippocampus- and amygdala-dependent long-term memory formation. Learn Mem. 2014;21(10):556–63. doi: 10.1101/lm.029348.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tang XH, Shay NF. Zinc has an insulin-like effect on glucose transport mediated by phosphoinositol-3-kinase and Akt in 3T3-L1 fibroblasts and adipocytes. Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131:1414–1420. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.5.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haase H, Maret W. Intracellular zinc fluctuations modulate protein tyrosine phosphatase activity in insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling. Experimental Cell Research. 2003;291(2):289–298. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu Y, et al. Zinc stimulates glucose consumption by modulating the insulin signaling pathway in L6 myotubes: essential roles of Akt-GLUT4, GSK3beta and mTOR-S6K1. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;34:126–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brewer GJ. Alzheimer’s disease causation by copper toxicity and treatment with zinc. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:92. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harris CJ, et al. Oral zinc reduces amyloid burden in Tg2576 mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(1):179–92. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adlard PA, Bush AI. Metal chaperones: a holistic approach to the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:15. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bonda DJ, et al. Role of metal dyshomeostasis in Alzheimer’s disease. Metallomics. 2011;3(3):267–70. doi: 10.1039/c0mt00074d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Strozyk D, et al. Zinc and copper modulate Alzheimer Abeta levels in human cerebrospinal fluid. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(7):1069–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sparks DL, Schreurs BG. Trace amounts of copper in water induce beta-amyloid plaques and learning deficits in a rabbit model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):11065–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832769100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ceccom J, et al. Copper chelator induced efficient episodic memory recovery in a non-transgenic Alzheimer’s mouse model. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Quinn JF, et al. A copper-lowering strategy attenuates amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21(3):903–14. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Donnelly PS, Xiao Z, Wedd AG. Copper and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11(2):128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.01.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Davies KM, et al. Localization of copper and copper transporters in the human brain. Metallomics. 2013;5(1):43–51. doi: 10.1039/c2mt20151h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stefani MR, Gold PE. Intra-septal injections of glucose and glibenclamide attenuate galanin-induced spontaneous alternation performance deficits in the rat. Brain Res. 1998;813(1):50–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00876-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dember WN, Fowler H. Spontaneous alternation behavior. Psychol Bull. 1958;55(6):412–28. doi: 10.1037/h0045446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Johnson CT, et al. Damage to hippocampus and hippocampal connections: effects on DRL and spontaneous alternation. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1977;91(3):508–22. doi: 10.1037/h0077346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhao WQ, et al. Insulin and the insulin receptor in experimental models of learning and memory. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;490(1–3):71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parent MB, et al. Intraseptal infusions of muscimol impair spontaneous alternation performance: infusions of glucose into the hippocampus, but not the medial septum, reverse the deficit. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1997;68(1):75–85. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1997.3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McNay EC, Sandusky LA, Pearson-Leary J. Hippocampal insulin microinjection and in vivo microdialysis during spatial memory testing. J Vis Exp. 2013;71:e4451. doi: 10.3791/4451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pearson-Leary J, McNay EC. Intrahippocampal administration of amyloid-beta(1–42) oligomers acutely impairs spatial working memory, insulin signaling, and hippocampal metabolism. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30(2):413–22. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-112192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Takeda A, et al. Intracellular Zn signaling in the dentate gyrus is required for object recognition memory. Hippocampus. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hipo.22322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Takeda A, et al. Intracellular Zn(2+) signaling in cognition. J Neurosci Res. 2014;92(7):819–24. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Takeda A. Significance of Zn signaling in cognition: Insight from synaptic Zn dyshomeostasis. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mott DD, Dingledine R. Unraveling the role of zinc in memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(8):3103–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100323108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gaetke L. Copper toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidant nutrients. Toxicology. 2003;189(1–2):147–163. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Markesbery WR, et al. Brain trace element concentrations in aging. Neurobiol Aging. 1984;5(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(84)90081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kasarskis EJ. Zinc metabolism in normal and zinc-deficient rat brain. Exp Neurol. 1984;85(1):114–27. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(84)90166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Takeda A, et al. Brain uptake of trace metals, zinc and manganese, in rats. Brain Res. 1994;640(1–2):341–4. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91891-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Takeda A, Sawashita J, Okada S. Biological half-lives of zinc and manganese in rat brain. Brain Res. 1995;695(1):53–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00916-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bucossi S, et al. Copper in Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of serum,plasma, and cerebrospinal fluid studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24(1):175–85. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ventriglia M, et al. Copper in Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of serum, plasma, and cerebrospinal fluid studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30(4):981–4. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kozlowski H, et al. Copper, zinc and iron in neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and prion diseases) Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 2012;256(19–20):2129–2141. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lovell MA, et al. Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer’s disease senile plaques. Journal of Neurological Sciences. 1998;158:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]