Abstract

BACKGROUND

In patients with metastatic breast cancer that is positive for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), progression-free survival was significantly improved after first-line therapy with pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel, as compared with placebo, trastuzumab, and docetaxel. Overall survival was significantly improved with pertuzumab in an interim analysis without the median being reached. We report final prespecified overall survival results with a median follow-up of 50 months.

METHODS

We randomly assigned patients with metastatic breast cancer who had not received previous chemotherapy or anti-HER2 therapy for their metastatic disease to receive the pertuzumab combination or the placebo combination. The secondary end points of overall survival, investigator-assessed progression-free survival, independently assessed duration of response, and safety are reported. Sensitivity analyses were adjusted for patients who crossed over from placebo to pertuzumab after the interim analysis.

RESULTS

The median overall survival was 56.5 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 49.3 to not reached) in the group receiving the pertuzumab combination, as compared with 40.8 months (95% CI, 35.8 to 48.3) in the group receiving the placebo combination (hazard ratio favoring the pertuzumab group, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.84; P<0.001), a difference of 15.7 months. This analysis was not adjusted for crossover to the pertuzumab group and is therefore conservative. Results of sensitivity analyses after adjustment for crossover were consistent. Median progression-free survival as assessed by investigators improved by 6.3 months in the pertuzumab group (hazard ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.58 to 0.80). Pertuzumab extended the median duration of response by 7.7 months, as independently assessed. Most adverse events occurred during the administration of docetaxel in the two groups, with long-term cardiac safety maintained.

CONCLUSIONS

In patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, the addition of per tuzumab to trastuzumab and docetaxel, as compared with the addition of placebo, significantly improved the median overall survival to 56.5 months and extended the results of previous analyses showing the efficacy of this drug combination. (Funded by F. Hoffmann–La Roche and Genentech; CLEOPATRA ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00567190.)

The overexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) in breast cancer results in more aggressive disease with a poor prognosis.1 The humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies pertuzumab and trastuzumab are more active in combination than alone because of more comprehensive signaling blockade.2,3 We investigated combination therapy with docetaxel for first-line treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer in the Clinical Evaluation of Pertuzumab and Trastuzumab (CLEOPATRA) trial. Analysis of the primary end point showed that patients who received pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel (pertuzumab group) had a significantly longer median progression-free survival, as assessed by independent reviewers, than did those who received placebo, trastuzumab, and docetaxel (control group) (hazard ratio favoring the pertuzumab group, 0.62).4 The second interim analysis of overall survival confirmed significantly longer survival in the pertuzumab group (hazard ratio, 0.66).5 Safety profiles (including cardiac) were similar and consistent across the two study groups and the analysis time points.4–6 Here we report follow-up data at a median of 50 months regarding overall survival, investigator-assessed progression-free survival and safety, and independently assessed duration of response.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND PATIENTS

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial,4,5 we enrolled patients who were at least 18 years of age with locally recurrent, unresectable, or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer that was centrally confirmed. Eligible patients had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 50% or more at baseline, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1, and had received no more than one hormonal treatment for metastatic disease. Adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without trastuzumab was allowed. Patients were excluded if they had central-nervous-system metastases, if the LVEF was less than 50% during or after previous trastuzumab therapy, or if they had received other anticancer therapy (with the exception of one previous hormonal regimen) or had a cumulative exposure of more than 360 mg of doxorubicin per square meter of body-surface area or its equivalent. All randomization and masking processes and assessments have been reported previously.4,5

After significant improvement in overall survival was reported with pertuzumab (Perjeta, F. Hoffmann–La Roche and Genentech),5 patients who were still receiving the placebo combination in whom disease had not progressed were invited to cross over to receive pertuzumab. Overall survival results presented here are from the intention-to-treat population; therefore, data from crossover patients were analyzed in the control group. Two sensitivity analyses of overall survival were conducted: one in which data from crossover patients were censored at the time of the first pertuzumab dose and one in which these patients were excluded from the results. Post-crossover safety data are reported separately.

The CLEOPATRA trial was performed in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Protocol approval was obtained from an independent ethics committee at each study site. All patients provided written informed consent.

STUDY OVERSIGHT

The study was designed by the senior academic authors and representatives of the sponsors, F. Hoffmann–La Roche and Genentech. Data were collected by the sponsors and analyzed in collaboration with the senior academic authors, who vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and analyses and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol. The protocol, including the statistical analysis plan, is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. All investigators participating in the study agreed to confidentiality regarding the data. The first author prepared the initial draft of the manuscript with assistance from a medical writer employed by Health Interactions and funded by F. Hoffmann–La Roche. All authors contributed to subsequent drafts and made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

STUDY PROCEDURES

Study drugs were administered intravenously every 3 weeks. Pertuzumab (at a dose of 840 mg) or placebo was given on day 1 of cycle 1, followed by 420 mg on day 1 of each subsequent cycle; trastuzumab (Herceptin, F. Hoffmann–La Roche and Genentech) at a dose of 8 mg per kilogram of body weight was administered on day 2 of cycle 1, followed by 6 mg per kilogram on day 1 of the remaining cycles. Pertuzumab or placebo and trastuzumab were administered until disease progression or the occurrence of unmanageable toxic effects; dose reductions were not allowed. Docetaxel was given at a dose of 75 mg per square meter on day 2 of cycle 1 and on day 1 of the remaining cycles; at least six cycles were recommended, but fewer cycles were allowed in case of disease progression or unmanageable toxic effects, and more cycles were allowed at the discretion of the investigator or patient. Docetaxel could be escalated to 100 mg per square meter if there were no unmanageable toxic effects and could be reduced by 25% in the case of myelosuppression, hepatic dysfunction, or other toxic effects. Growth-factor support could be added according to prescribing information and the guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.7 No concurrent hormonal therapy was allowed before disease progression.

STUDY END POINTS

Since independent review of progression-free survival and the objective response rate were stopped after the first analysis,4 we report updated data on the secondary end points of overall survival (time from randomization to death from any cause) and investigator-assessed progression-free survival, which was defined as the time from randomization to the first documented radio-graphic evidence of progressive disease, according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), version 1.0,8 or death from any cause within 18 weeks after the last investigator assessment of tumors. We also present the duration of response from the time of the data cutoff for the primary analysis.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data for patients who were alive or lost to follow-up were censored at the last date they were known to be alive or at the time of randomization plus 1 day, if no information was available after baseline. For the final analysis of overall survival, we determined that the study would have a power of 80% to detect a 33% improvement in the pertuzumab group (hazard ratio for death from any cause, 0.75) after the occurrence of 385 deaths. The statistical stopping boundary for each interim analysis was established with the use of the O’Brien–Fleming approach and was crossed at the second interim analysis; consequently, this final analysis is considered to be descriptive.

We used the log-rank test to compare overall survival between the two treatment groups, with stratification according to status with respect to adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy and geographic region. Kaplan–Meier analyses were used to estimate medians. A Cox proportional-hazards model was used to estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals with the same stratification factors.

Subgroup analyses were performed to ensure robustness of the treatment effect across pre-specified categories. All analyses were performed with the use of SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

STUDY POPULATION

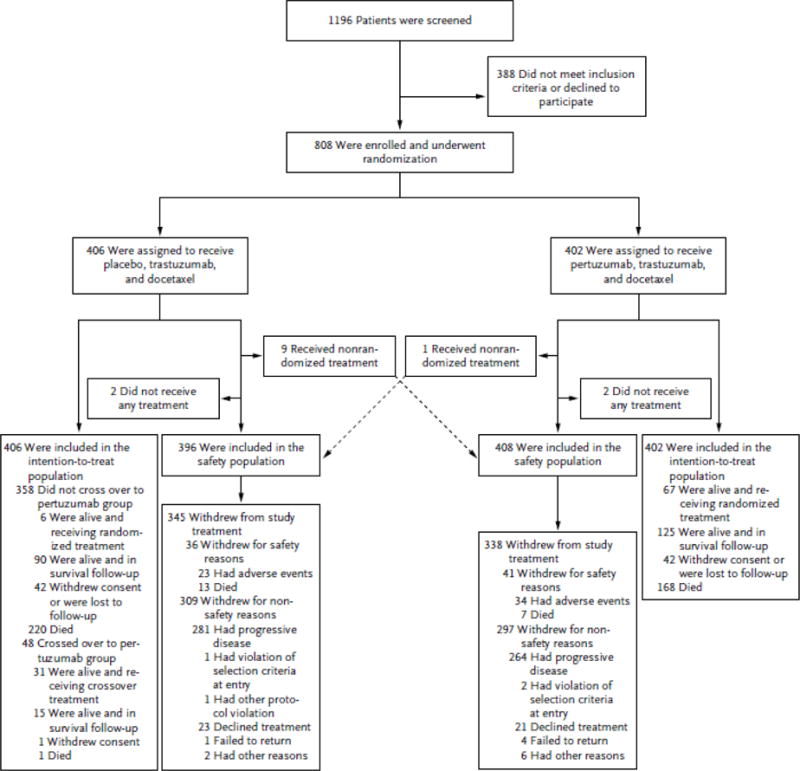

Patients were enrolled from February 12, 2008, through July 7, 2010. The cutoff for data collection for this analysis was February 11, 2014. (Enrollment and randomization are shown in Fig. 1.) Baseline characteristics were similar in the two study groups; 630 patients (88.0%) had visceral disease.4,5 A total of 389 patients had died at the time of this analysis. Median follow-up was 49.5 months (range, 0 to 70) in the pertuzumab group and 50.6 months (range, 0 to 69) in the control group. After the interim analysis of overall survival in May 2012, investigators were informed about study-group assignments. Between July and November 2012, a total of 48 of the 406 patients (11.8%) in the control group crossed over to receive pertuzumab.

Figure 1. Enrollment and Outcomes.

All patients who underwent randomization were included in the intention-to-treat population, and patients who received at least one dose of a study drug were included in the safety analysis. Reasons for withdrawals are shown. Included in the safety population are nine patients in the control group who received pertuzumab and one patient in the pertuzumab group who received placebo, as indicated.

OVERALL SURVIVAL

Intention-To-Treat Population

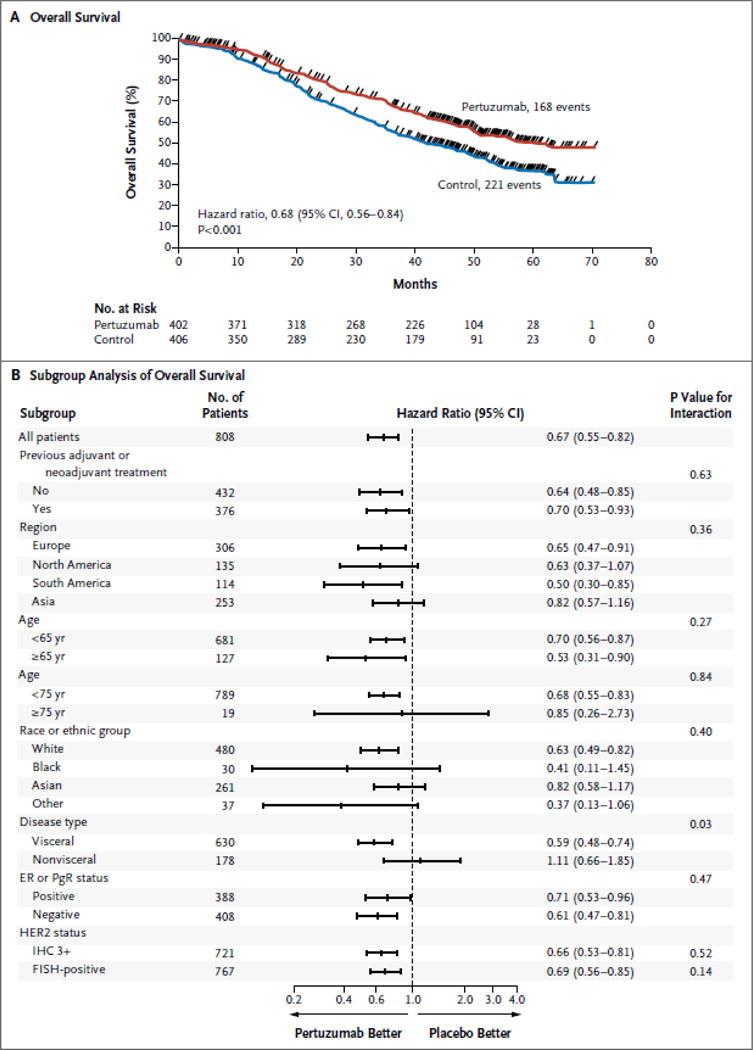

Deaths were reported in 168 of 402 patients (41.8%) in the pertuzumab group and in 221 of 406 patients (54.4%) in the control group (hazard ratio favoring the pertuzumab group, 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.56 to 0.84; P<0.001) (Fig. 2A). The median overall survival was 56.5 months (95% CI, 49.3 to not reached) in the pertuzumab group and 40.8 months (95% CI, 35.8 to 48.3) in the control group, a difference of 15.7 months. The estimated Kaplan–Meier overall survival rate was 94.4% (95% CI, 92.1 to 96.7) in the pertuzumab group and 89.0% (95% CI, 85.9 to 92.1) in the control group at 1 year; 80.5% (95% CI, 76.5 to 84.4) and 69.7% (95% CI, 65.0 to 74.3), respectively, at 2 years; 68.2% (95% CI, 63.4 to 72.9) and 54.3% (95% CI, 49.2 to 59.4), respectively, at 3 years; and 57.6% (95% CI, 52.4 to 62.7) and 45.4% (95% CI, 40.2 to 50.6), respectively, at 4 years. Exploratory analyses in predefined subgroups showed a consistent benefit with pertuzumab (Fig. 2B). The hazard ratio for death from any cause among patients who had previously been treated with trastuzumab (47 patients in the pertuzumab group and 41 patients in the control group) was 0.80 (95% CI, 0.44 to 1.47).

Figure 2. Overall Survival.

Panel A shows Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival in the intention-to-treat population, stratified according to adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy and geographic region. The median overall survival among patients receiving pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel (pertuzumab group) was 56.5 months, 15.7 months longer than survival among patients receiving placebo, trastuzumab, and docetaxel (control group). The tick marks indicate censoring events. Panel B shows hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for overall survival in all prespecified subgroups according to baseline characteristics, without stratification. Race or ethnic group was determined by the investigator. “Other” includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and other populations. A grade of 3+ on immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis indicates positivity for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). For the assessment of HER2 status, prespecified subgroup analyses were restricted to patients whose tumors had an IHC score of 3+ or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) positive status, since these categories accounted for approximately 90% of patients. CI denotes confidence interval, ER estrogen receptor, and PgR progesterone receptor.

Sensitivity Analyses

The 48 patients without disease progression who opted to cross over from the control group to receive pertuzumab had all been receiving treatment for 2 years or longer. When their data were censored at the time of the first pertuzumab dose, the median overall survival was 56.5 months (95% CI, 49.3 to not reached) in the pertuzumab group and 39.6 months (95% CI, 35.0 to 45.1) in the control group (hazard ratio, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.78; P<0.001) (Fig. S1A in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org). When crossover patients were excluded, the median overall survival was 56.5 months (95% CI, 49.3 to not reached) in the pertuzumab group and 34.7 months (95% CI, 31.2 to 39.4) in the control group (hazard ratio for death from any cause, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.45 to 0.67; P<0.001) (Fig. S1B in the Supplementary Appendix).

INVESTIGATOR-ASSESSED PROGRESSION-FREE SURVIVAL

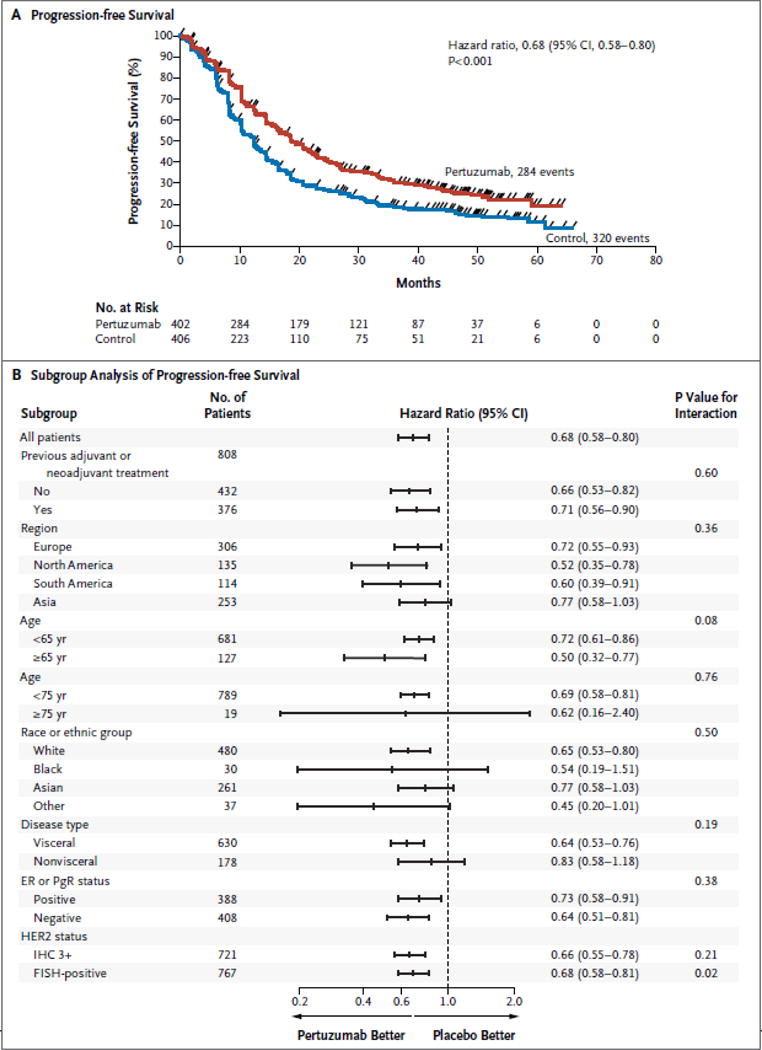

In the investigator-assessed intention-to-treat analysis, events occurred in 284 of 402 patients (70.6%) in the pertuzumab group and 320 of 406 patients (78.8%) in the control group (hazard ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.58 to 0.80; P<0.001) (Fig. 3A). The results of subgroup analyses were consistent (Fig. 3B). The medians were unchanged from the May 2012 interim analysis (18.7 months in the pertuzumab group and 12.4 months in the control group, an improvement of 6.3 months).5

Figure 3. Progression-free Survival.

Panel A shows Kaplan–Meier estimates of investigator-assessed progression-free survival in the intention-to-treat population, stratified according to adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy and geographic region. The median progression-free survival was 18.7 months in the pertuzumab group as compared with 12.4 months in the control group, an improvement of 6.3 months. The tick marks indicate censoring events. Panel B shows hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for investigator-assessed progression-free survival in all prespecified subgroups according to baseline characteristics, without stratification.

DURATION OF RESPONSE

The duration of response was independently assessed in patients with a confirmed partial or complete response at the time of the primary analysis (275 patients in the pertuzumab group and 233 in the control group). Median durations of response were 20.2 months in the pertuzumab group (95% CI, 16.0 to 24.0) and 12.5 months in the control group (95% CI, 10.0 to 15.0).

BREAST-CANCER THERAPIES AFTER DISCONTINUATION OF STUDY TREATMENT

Among the 704 patients in the intention-to-treat population who received breast-cancer therapies after the discontinuation of the study treatment, the proportions of patients who received various drugs was balanced in the two study groups (Table 1). A total of 72.9% patients in the pertuzumab group and 71.5% in the control group received HER2-targeted therapy.

Table 1.

Breast-Cancer Treatments Received by Patients Who Discontinued Study Treatment.*

| Treatment | Control Group (N = 369) |

Pertuzumab Group (N = 335) |

|---|---|---|

| no. of patients (%) | ||

| Any treatment received after discontinuing study treatment | 291 (78.9) | 258 (77.0) |

|

| ||

| HER2-targeted treatment | 208 (71.5) | 188 (72.9) |

|

| ||

| Trastuzumab | 121 (41.6) | 117 (45.3) |

|

| ||

| Pertuzumab | 4 (1.4) | 2 (0.8) |

|

| ||

| Lapatinib | 142 (48.8) | 124 (48.1) |

|

| ||

| Trastuzumab emtansine | 34 (11.7) | 32 (12.4) |

|

| ||

| Capecitabine | 170 (58.4) | 142 (55.0) |

|

| ||

| Vinorelbine | 88 (30.2) | 67 (26.0) |

|

| ||

| Doxorubicin | 56 (19.2) | 41 (15.9) |

|

| ||

| Cyclophosphamide | 49 (16.8) | 41 (15.9) |

|

| ||

| Taxanes | 56 (19.2) | 39 (15.1) |

|

| ||

| Hormonal treatments | 56 (19.2) | 69 (26.7) |

Percentages are based on the numbers of patients in the intention-to-treat population who received any treatment after the discontinuation of study drugs. Patients who discontinued treatment include 4 patients who were not treated and 17 patients who crossed over to receive pertuzumab and subsequently withdrew from crossover treatment.

TREATMENT EXPOSURE

The median number of study-treatment cycles received by patients in the safety population was 24 in the pertuzumab group (range, 1 to 96; 197 patients received more than the median number) and 15 in the control group (range, 1 to 67). Patients who crossed over to the pertuzumab group received a median of 22.5 cycles of pertuzumab (range, 1 to 28), which was similar to the median number of cycles received by patients in the pertuzumab safety population. Docetaxel exposure did not change between data cutoffs (median, 8 cycles in each group).

SIDE-EFFECT PROFILE AND CARDIAC SAFETY

All Patients

Rates of adverse events remained consistent with those in the primary analysis, with headache, upper respiratory tract infection, and muscle spasm reported as new adverse events with a difference of at least 5 percentage points between groups. Most events were grade 1 or 2 and occurred during docetaxel administration and declined after discontinuation. A list of the most common adverse events of all grades that occurred at a frequency of 25% or more or showed a difference of at least 5 percentage points between study groups overall is provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix. Table 2 shows the rates of the same most common adverse events after the discontinuation of docetaxel.

Table 2.

Adverse Events after the Discontinuation of Docetaxel in the Safety Population.*

| Adverse Event | Control Group (N = 261) |

Pertuzumab Group (N = 306) |

|---|---|---|

| Most common events of any grade — no. of patients (%)† | ||

| Alopecia | 6 (2.3) | 5 (1.6) |

| Diarrhea‡ | 37 (14.2) | 86 (28.1) |

| Neutropenia | 13 (5.0) | 10 (3.3) |

| Nausea | 30 (11.5) | 39 (12.7) |

| Fatigue | 25 (9.6) | 41 (13.4) |

| Rash‡ | 21 (8.0) | 56 (18.3) |

| Asthenia | 23 (8.8) | 41 (13.4) |

| Decreased appetite | 14 (5.4) | 22 (7.2) |

| Peripheral edema | 32 (12.3) | 28 (9.2) |

| Vomiting | 17 (6.5) | 30 (9.8) |

| Myalgia | 19 (7.3) | 25 (8.2) |

| Mucosal inflammation | 4 (1.5) | 11 (3.6) |

| Headache | 32 (12.3) | 52 (17.0) |

| Constipation | 18 (6.9) | 17 (5.6) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection‡ | 32 (12.3) | 56 (18.3) |

| Pruritus‡ | 15 (5.7) | 42 (13.7) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 0 |

| Dry skin | 10 (3.8) | 10 (3.3) |

| Muscle spasm‡ | 6 (2.3) | 24 (7.8) |

Data are for patients who received at least one dose of a study drug after completing docetaxel treatment. Data for overall adverse events are provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix.

The most common events are those that occurred with a frequency of 25% or more overall (including during the docetaxel treatment period) or that differed by 5 percentage points or more in frequency between the two groups overall.

The frequency of this event was at least 5 percentage points greater in the pertuzumab group, as compared with the control group.

The rate of left ventricular dysfunction, as defined by the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0, and the New York Heart Association,6 was somewhat lower in the pertuzumab group than in the control group (6.6% [27 of 408 patients] vs. 8.6% [34 of 396 patients]). There was one new event of symptomatic left ventricular dysfunction in the pertuzumab group after 40 months, an event that resolved after 3 months with both antibodies discontinued. Reductions in the LVEF of 10% or more from baseline to an absolute value of less than 50% occurred in 24 of 394 patients (6.1%) in the pertuzumab group and 28 of 378 patients (7.4%) in the control group. Declines were reversed in 21 of 24 patients (87.5%) in the pertuzumab group and 22 of 28 patients (78.6%) in the control group.

Most deaths were due to disease progression (in 150 of 408 patients [36.8%] in the pertuzumab group and 196 of 396 patients [49.5%] in the control group). Other causes of death were febrile neutropenia or infection (in 7 of 408 patients [1.7%] in the pertuzumab group and 6 of 396 patients [1.5%] in the control group) and causes that were classified as “other” or “unknown” (in 12 of 408 patients [2.9%] in the pertuzumab group and 15 of 396 patients [3.8%] in the control group).

Crossover Population

No new safety signals were identified among patients in the control group who crossed over to receive pertuzumab. Most events were of grade 1 or 2. Of the 221 events in the crossover group, 7 were grade 3 events, and 2 were grade 4 events (diarrhea and dehydration in the same patient). There was one death from an unknown cause. No symptomatic left ventricular dysfunction was reported after crossover. Two patients had asymptomatic reductions in the LVEF.

DISCUSSION

First-line therapy with pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel significantly improved overall survival among patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, as compared with placebo, trastuzumab, and docetaxel. Since this was an intention-to-treat analysis, patients in the control group who crossed over to receive pertuzumab were included in the control group, a factor that added to the strength of the findings. The between-group separation in the Kaplan–Meier curves occurred early and was maintained over time. Findings in subgroup analyses were consistent with the final results and the results of previous analyses.

We were able to estimate the treatment effect on the basis of a median overall survival of 56.5 months in the pertuzumab group, a duration that is exceptionally long in this population of patients. In previous prospective studies of first-line therapy with trastuzumab plus chemotherapy in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, the median overall survival has ranged from 25.1 months to 38.1 months.9–13 The progression-free survival benefit was also maintained over time in our study.4,5

The majority of adverse events occurred during docetaxel treatment. Long-term cardiac safety was maintained, since treatment with pertuzumab did not increase cardiac toxicity (including asymptomatic and symptomatic left ventricular dysfunction), as compared with placebo. Symptoms developed at a later time with pertuzumab and quality of life did not differ from that in the control group during the chemotherapy period in the pertuzumab group.14

Preclinical data showed that combining pertuzumab and trastuzumab resulted in greater activity than that with either antibody alone owing to more comprehensive signaling blockade, since the antibodies bind to different HER2 epitopes.2,3 The BO17929 study initially showed that the combination of pertuzumab plus trastuzumab was active in patients with advanced breast cancer following progression15 and subsequently showed that it was the combination, rather than pertuzumab alone, that was responsible for the activity.16 The efficacy of combination therapy was also shown among patients receiving neo-adjuvant therapy, with the use of pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel resulting in higher rates of complete response on pathological analysis, as compared with trastuzumab plus docetaxel, pertuzumab plus docetaxel, or pertuzumab plus trastuzumab.17 These data supported the use of neoadjuvant pertuzumab with trastuzumab and docetaxel in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer, an indication that was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration.18

Despite the clinically meaningful survival results in our study, important questions remain to be addressed in this field. First, most deaths in the study were due to breast cancer; therefore, better treatments are still needed. This is particularly important in patients with early disease, such as those in the ongoing Adjuvant Pertuzumab and Herceptin in Initial Therapy of Breast Cancer (APHINITY) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01358877). Second, it is not clear whether hormonal therapy plus pertuzumab and trastuzumab is more effective than hormonal therapy plus trastuzumab alone in patients with hormone receptor–positive disease. Third, there is no biomarker in addition to HER2 that predicts which patients with HER2-positive disease would benefit most from the combination of pertuzumab and trastuzumab.19–21 The presence of mutated PIK3CA may indicate an adverse prognosis for patients with metastatic disease but did not have a predictive value in our study.21 Whether other chemotherapeutic agents could improve on the safety profile is a fourth area for investigation. A phase 2 study assessing progression-free survival at 6 months with pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and paclitaxel showed few grade 3 or 4 adverse events and no cardiac events.22 Finally, the question of when, if ever, therapy with pertuzumab plus trastuzumab for metastatic breast cancer should be stopped remains unanswered. With trastuzumab, continuing therapy after progression and adding a different chemotherapeutic agent resulted in prolonged progression-free survival,23 and lapatinib added to trastuzumab was superior to lapatinib monotherapy with respect to progression-free and overall survival.24 The current recommendation is to discontinue pertuzumab after progression, but clinical trials are warranted to determine the most effective duration of therapy.

This analysis has several limitations. First, patients who crossed over to receive pertuzumab were included in the control group, which in the intention-to-treat analysis favored the control group. Even so, the treatment effect favored pertuzumab in sensitivity analyses that excluded the crossover group (hazard ratio, 0.55) and that censored data at the time of the first pertuzumab dose (hazard ratio, 0.63), since data for patients with a good therapeutic response, who had continued to receive study treatment for a long time, were censored or excluded from the control group but not from the pertuzumab group. However, these analyses support the results of the intention-to-treat analysis.

Second, although the subgroups were predefined, the analyses were exploratory and not powered for a statistical result. Small numbers of patients and data with wide confidence intervals limited interpretation of data among patients in the subgroup with nonvisceral disease, for example. The hazard ratio for progression-free survival in this subgroup was 0.96 in the primary analysis,4 with an updated hazard ratio of 0.83. A relatively small proportion of patients in this subgroup died (58 of 178 patients [32.6%] overall), and survival was long, with a median that was not reached in the pertuzumab group and that was 61.5 months in the control group (data not shown). This study included a large proportion of patients with visceral disease. The subgroup of patients who received adjuvant or neoadjuvant trastuzumab was also small, probably because trastuzumab was not widely available for this indication during the recruitment for this trial. However, the hazard ratios for progression-free and overall survival were similar (0.75 and 0.80, respectively), suggesting a treatment benefit in favor of pertuzumab. One retrospective study has shown better outcomes with trastuzumab in patients with metastatic breast cancer who had received no previous adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy with the drug,25 whereas a controlled cohort study showed no difference.26 Further research is therefore needed.

In conclusion, in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, the addition of pertuzumab to trastuzumab and docetaxel, as compared with the addition of placebo, significantly increased the median overall survival to 56.5 months, an improvement of 15.7 months over survival in the control group, and extended the results of previous analyses showing the efficacy of this drug combination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by F. Hoffmann–La Roche and Genentech.

We thank Daniel Clyde of Health Interactions for providing writing assistance.

Appendix

The authors’ affiliations are as follows: the Washington Cancer Institute, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC (S.M.S.); Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Memorial Hospital, New York (J.B.); the Department of Oncology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul (S.-B.K.), and the Center for Breast Cancer, National Cancer Center, Goyang (J.R.) — both in South Korea; the N.N. Petrov Research Institute of Oncology, St. Petersburg, Russia (V.S.); Centre René Gauducheau, Saint-Herblain (Nantes) (M.C.), and Centre Antoine Lacassagne, Nice (J.-M.F.) — both in France; 12 de Octubre University Hospital, Medical Oncology Department, Madrid (E. Ciruelos), and Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Barcelona (J.C.) — both in Spain; the National Center for Tumor Diseases, University Hospital, Heidelberg, Germany (A.S.); Roche Products, Welwyn, United Kingdom (S.H., E. Clark, G.R.); and Genentech, South San Francisco, CA (M.C.B.).

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Ross JS, Slodkowska EA, Symmans WF, Pusztai L, Ravdin PM, Hortobagyi GN. The HER-2 receptor and breast cancer: ten years of targeted anti-HER-2 therapy and personalized medicine. Oncologist. 2009;14:320–68. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nahta R, Hung MC, Esteva FJ. The HER-2-targeting antibodies trastuzumab and pertuzumab synergistically inhibit the survival of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2343–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheuer W, Friess T, Burtscher H, Bossenmaier B, Endl J, Hasmann M. Strongly enhanced antitumor activity of trastuzumab and pertuzumab combination treatment on HER2-positive human xenograft tumor models. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9330–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baselga J, Cortés J, Kim SB, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:109–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swain SM, Kim SB, Cortés J, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (CLEOPATRA study): overall survival results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:461–71. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70130-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swain SM, Ewer MS, Cortés J, et al. Cardiac tolerability of pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer in CLEOPATRA: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. Oncologist. 2013;18:257–64. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith TJ, Khatcheressian J, Lyman GH, et al. 2006 Update of recommendations for the use of white blood cell growth factors: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3187–205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marty M, Cognetti F, Maraninchi D, et al. Randomized phase II trial of the efficacy and safety of trastuzumab com bined with docetaxel in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer administered as first-line treatment: the M77001 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4265–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersson M, Lidbrink E, Bjerre K, et al. Phase III randomized study comparing docetaxel plus trastuzumab with vinorelbine plus trastuzumab as first-line therapy of metastatic or locally advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: the HERNATA study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:264–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.8213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valero V, Forbes J, Pegram MD, et al. Multicenter phase III randomized trial comparing docetaxel and trastuzumab with docetaxel, carboplatin, and trastuzumab as first-line chemotherapy for patients with HER2-gene-amplified metastatic breast cancer (BCIRG 007 study): two highly active therapeutic regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:149–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.6450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baselga J, Manikhas A, Cortés J, et al. Phase III trial of nonpegylated liposomal doxorubicin in combination with trastuzumab and paclitaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:592–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cortés J, Baselga J, Im YH, et al. Health-related quality-of-life assessment in CLEOPATRA, a phase III study combining pertuzumab with trastuzumab and docetaxel in metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2630–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baselga J, Gelmon KA, Verma S, et al. Phase II trial of pertuzumab and trastuzumab in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer that progressed during prior trastuzumab therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1138–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cortés J, Fumoleau P, Bianchi GV, et al. Pertuzumab monotherapy after trastuzumab-based treatment and subsequent reintroduction of trastuzumab: activity and tolerability in patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1594–600. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.4207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gianni L, Pienkowski T, Im YH, et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (Neo-Sphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:25–32. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amiri-Kordestani L, Wedam S, Zhang L, et al. First FDA approval of neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer: pertuzumab for the treatment of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5359–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneeweiss A, Chia S, Hegg R, et al. Evaluating the predictive value of biomarkers for efficacy outcomes in response to pertuzumab- and trastuzumab-based therapy: an exploratory analysis of the TRYPHAENA study. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:R73. doi: 10.1186/bcr3690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gianni L, Bianchini G, Kiermaier A, et al. Neoadjuvant pertuzumab (P) and trastuzumab (H): biomarker analyses of a 4-arm randomized Phase II study (‘Neo-Sphere’) in patients (pts) with HER2-positive breast cancer (BC). Presented at the 34th annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, TX. December 6–10, 2011; abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baselga J, Cortés J, Im S-A, et al. Bio-marker analyses in CLEOPATRA: a phase III, placebo-controlled study of pertuzumab in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive, first-line metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3753–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.5384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dang C, Iyengar N, Datko F, et al. Phase II study of paclitaxel given once per week along with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Dec 29; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.1745. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Minckwitz G, du Bois A, Schmidt M, et al. Trastuzumab beyond progression in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive advanced breast cancer: a German Breast Group 26/Breast International Group 03-05 study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1999–2006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blackwell KL, Burstein HJ, Storniolo AM, et al. Overall survival benefit with lapatinib in combination with trastuzumab for patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer: final results from the EGF104900 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2585–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murthy RK, Varma A, Mishra P, et al. Effect of adjuvant/neoadjuvant trastuzumab on clinical outcomes in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:1932–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Negri E, Zambelli A, Franchi M, et al. Effectiveness of trastuzumab in first-line HER2+ metastatic breast cancer after failure in adjuvant setting: a controlled cohort study. Oncologist. 2014;19:1209–15. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.