Amyloidoses represent a group of human degenerative diseases characterized by the deposition of aggregates of abnormally folded proteins in single or multi-organs. Whereas neurologic amyloidoses, such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease, have received the greatest recognition, there also exists a number of systemic amyloidoses that affect a number of target organs, including the heart.

Cardiac amyloidosis is primarily associated with the systemic production and release of a number of amyloidogenic proteins, notably immunoglobulin light chain proteins (also known as amyloid light chain or AL) or transthyretin proteins (TTR). Whereas AL proteins are typically always the result of a clonal plasma cell dyscrasia, TTR amyloidosis may result from mutations in the TTR protein, as in familial amyloidotic cardiomyopathy, or even from wild type protein in the elderly (known as senile systemic amyloidosis or ATTRwt).1, 2 Cardiac deposition of amyloidogenic proteins often results in an aggressive form of heart disease with resulting cardiac failure that is largely resistant to many common heart failure therapies. Though once thought to be a rare disease, cardiac amyloidosis is more recently acknowledged to be much more common. For instance, AL amyloidosis, the most frequent cause of systemic amyloidosis in the developed world, has an incidence similar to that of Hodgkin's lymphoma or chronic myelogenous leukemia, and was widely under-diagnosed due to its ambiguous presentation and rapid mortality. Similarly, autopsy studies have identified significant cardiac deposition of wild type TTR deposition in over 25% of individuals greater than 80 years of age.3 Physician education, along with now widely accessible assays for diagnosis and monitoring (such as the Freelite® serum free LC assay) as well as improved cardiac imaging have contributed to the increase in diagnosis. In addition to ultrasound echocardiography and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) by cardiac MRI,4 newer imaging modalities with 99mTc-pyrophosphate4, 5 and florbetapir6 have improved detection, monitoring of disease progression, and treatment response in cardiac amyloidosis. With these imaging modalities becoming more widely accessible, it is likely the identification of cardiac amyloidosis will only continue to increase. It is also likely that these non-invasive imaging methods will now be utilized to even screen people at elevated risk factors for developing cardiac amyloidoses, including patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and “smoldering” multiple myeloma at risk for AL amyloidosis, as well as asymptomatic gene carriers7 and African Americans who carry the TTR V122I mutation,8 who are at risk for TTR amyloidosis. Even in diseases thought to be localized, such as Alzheimer's disease, APP (Amyloid beta precursor protein)-derived Aβ protein has been found in the heart.9 With over 10% of the population over the age of 65 years currently suffering from Alzheimer's disease and only expected to increase, the potential rise in cardiac amyloidosis and secondary cardiac morbidity may also rise markedly.

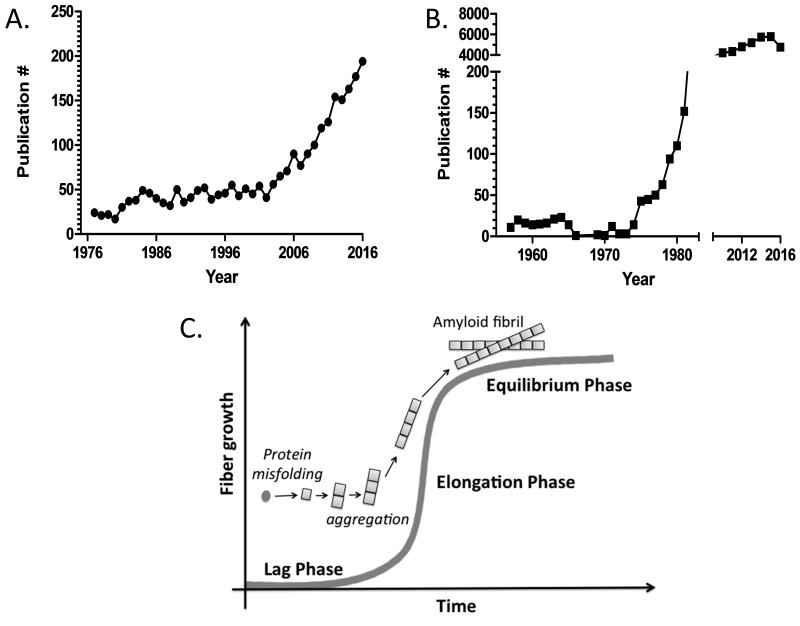

Given the projected rise in cardiac amyloidoses, in addition to improving diagnosis and monitoring through imaging, there is a great need to develop targeted therapies. Such therapies must not only antagonize the amyloid fibrils which cause physical damage to the heart, but also the pre-fibrillar misfolded proteins which are proteotoxic and the deleterious signaling pathways are triggered by these misfolded proteins. Development of such therapies will require greater understanding of the basic mechanisms of cardiac amyloidosis. Fortunately, greater research efforts are already underway. There has been a steady increase in publications with the keywords “heart” and “amyloidosis” over the past ten years (Figure1A). Compared to the study of “Alzheimer's Disease” (Figure1B), cardiac amyloidosis appears to mirror the early 1980's - when increased recognition of the disease burden spurred greater research efforts. Interestingly, the number of publications in amyloid research seems to follow the kinetics of amyloid fibril formation with a “lag phase” now giving rise to a “growth/elongation phase”, and eventually a “equilibrium phase” (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

(A) The number of publications using the keywords “heart” and “amyloidosis”. There has been a clear trend of increased publication in cardiac amyloidosis since the mid 2000s with suggestion of exponential growth of research in this area. (B) The number of publications using the keyword “Alzheimer's Disease” in PubMed increased dramatically in the late 1970s, reaching the current plateau of approximately 6,000 papers per year. Notably, the National Institute on Aging was established in 1974 and began funding Alzheimer's Disease Centers at medical institutions across the country in 1984. This exponential increase of research publications in Alzheimer's Disease resembles. (C) The established kinetics of amyloid fibril formation showing a “lag/ nucleation phase”, “elongation/growth phase”, and “equilibrium phase”.

While the root etiology of amyloid diseases is well established, namely the production (or over production) of precursor proteins that misfold, aggregate and forms amyloid fibrils in distal tissues, there still many other basic questions that remain unanswered. On a protein level, the structure of the pre-fibrillar protein in the circulation and in different tissues has not been clearly defined for LC and TTR, or has the effect of post-translational modifications. On an organ level, we do not understand the variable organ tropism observed with patients with AL amyloidosis. For instance, patients with ATTRwt do not typically develop the debilitating neuropathy frequently present in many of the familial forms of ATTRm, though there is only a single amino acid difference in the mutant tetrameric protein. Moreover, the interaction between pre-fibrillar proteins and local tissue environments where amyloid deposit is poorly understood. On an organism level, the contribution of other host factors, such as inflammation, aging, genetics and sex (ATTRwt nearly exclusively affects men) remains to be addressed. One shortcoming that has slowed investigation of these basic science questions and the development of targeted therapeutics, has been the lack of appropriate animal models that recapitulates the primary cardiac phenotypes and other diverse disease pathology observed in humans. The history of animal models in the neurologic amyloid diseases, mainly Alzheimer's, has revealed that development of animal models is a long process with dozens of different models, each manifesting only a portion of the components (etiology, symptoms, behavior, physiology, pathology) of a multi-factorial disease.10 While models that replicate only a partial phenotype allow for focused study of specific factors and their contribution to particular phenotype, such models also give rise to false discovery and artifact. The lack of ideal models may be one potential explanation as to why many therapeutics are effective in preclinical animal studies only to fail in human trials. Many attempts have been made to generate appropriate animal models for AL amyloidosis from mouse to fish to worms.11-14 Most such models have been limited in achieving proper phenotype or pathology. Mouse models of TTR have been able to modestly recapitulate some phenotype with minimal pathology, or pathology without a cardiac phenotype.15 Solely overexpressing the amyloidogenic precursor protein has been insufficient in inducing the full spectrum of disease in any species. In the test tube, amyloid fibrils can be generated from precursor proteins in the absence of other factors, but non-physiologic conditions are necessary to cause fibril formation on a laboratory timescale (pH, ionic strength, heat, agitation all forms of in vitro “stress”). Much like with cancer, purveying thought believes in a multiple hit hypothesis for the pathogenesis of amyloidosis or a “perfect storm” of underlying factors. What are these other “hits”? One important but poorly understood hit is the contribution of natural aging. Many cardiac amyloidoses are aging associated diseases. In the case of TTR, circulating protein is present from birth but only causes significant amyloid aggregation and tissue injury decades later. Whether stress, injury or local tissue inflammation contribute to amyloidogenic aggregation and deposition remains unknown. The age-related changes including but are not limited to oxidative stress, local tissue inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic dysregulation, all of which may affect protein folding/misfolding and subsequent tissue amyloid deposition, and represent key topics for future research. In the absence of high fidelity animal models, there is a greater need for close collaboration and data sharing among major cardiac amyloid clinical centers nationally and internationally to promote human based research for revealing disease mechanisms, to develop novel and personalized treatment strategies, and to train the next generations of scientists, physicians and physician scientists.

As basic science and clinical research enters the growth phase of cardiac amyloidosis, it will be imperative that the response to the rising prevalence of disease is the wider adaptation of sensitive imaging modalities, earlier diagnosis, and development of targeted therapies. Due to the complexity of disease and diversity in phenotype, it is likely that effective therapy will necessitate precision-based approaches. Only through a more definitive understanding of disease mechanisms will such therapies become a reality and the disease will again return a rarity.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the immense contributions of the late Drs. Carl Apstein and David Seldin, including their inspiration, support and encouragement for so many in the pursuit of amyloid research. We would also like to acknowledge the support of the BWH Cardiac Amyloid Program and The Amyloidosis Center at Boston University School of Medicine.

Sources of Funding: This was supported by National Institution of Health grants HL088533, HL112831, and HL128135, American Heart Association 16CSA28880004 and The Demarest Lloyd Jr. Foundation.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- APP

Amyloid beta precursor protein

- AL

Amyloid light chain

- LGE

Late Gadolinium Enhancement

- TTR

Transthyretin

Footnotes

Disclosure: None

References

- 1.Falk RH, Alexander KM, Liao R, Dorbala S. AL (Light-Chain) Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Review of Diagnosis and Therapy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016;68:1323–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connors LH, Sam F, Skinner M, Salinaro F, Sun F, Ruberg FL, Berk JL, Seldin DC. Heart Failure Resulting From Age-Related Cardiac Amyloid Disease Associated With Wild-Type Transthyretin: A Prospective, Observational Cohort Study. Circulation. 2016;133:282–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanskanen M, Peuralinna T, Polvikoski T, Notkola IL, Sulkava R, Hardy J, Singleton A, Kiuru-Enari S, Paetau A, Tienari PJ, Myllykangas L. Senile systemic amyloidosis affects 25% of the very aged and associates with genetic variation in alpha2-macroglobulin and tau: a population-based autopsy study. Annals of medicine. 2008;40:232–9. doi: 10.1080/07853890701842988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fontana M, Chung R, Hawkins PN, Moon JC. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance for amyloidosis. Heart failure reviews. 2015;20:133–44. doi: 10.1007/s10741-014-9470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castano A, Haq M, Narotsky DL, Goldsmith J, Weinberg RL, Morgenstern R, Pozniakoff T, Ruberg FL, Miller EJ, Berk JL, Dispenzieri A, Grogan M, Johnson G, Bokhari S, Maurer MS. Multicenter Study of Planar Technetium 99m Pyrophosphate Cardiac Imaging: Predicting Survival for Patients With ATTR Cardiac Amyloidosis. JAMA cardiology. 2016;1:880–889. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park MA, Padera RF, Belanger A, Dubey S, Hwang DH, Veeranna V, Falk RH, Di Carli MF, Dorbala S. 18F-Florbetapir Binds Specifically to Myocardial Light Chain and Transthyretin Amyloid Deposits: Autoradiography Study. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging. 2015:8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.002954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haq M, Pawar S, Berk JL, Miller EJ, Ruberg FL. Can 99m-Tc-Pyrophosphate Aid in Early Detection of Cardiac Involvement in Asymptomatic Variant TTR Amyloidosis? JACC Cardiovascular imaging. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quarta CC, Buxbaum JN, Shah AM, Falk RH, Claggett B, Kitzman DW, Mosley TH, Butler KR, Boerwinkle E, Solomon SD. The amyloidogenic V122I transthyretin variant in elderly black Americans. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;372:21–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Troncone L, Luciani M, Coggins M, Wilker EH, Ho CY, Codispoti KE, Frosch MP, Kayed R, Del Monte F. Abeta Amyloid Pathology Affects the Hearts of Patients With Alzheimer's Disease: Mind the Heart. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016;68:2395–2407. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drummond E, Wisniewski T. Alzheimer's disease: experimental models and reality. Acta neuropathologica. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1662-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diomede L, Rognoni P, Lavatelli F, Romeo M, del Favero E, Cantù L, Ghibaudi E, di Fonzo A, Corbelli A, Fiordaliso F, Palladini G, Valentini V, Perfetti V, Salmona M, Merlini G. A Caenorhabditis elegans–based assay recognizes immunoglobulin light chains causing heart amyloidosis. Blood. 2014;123:3543–3552. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-525634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mishra S, Guan J, Plovie E, Seldin DC, Connors LH, Merlini G, Falk RH, MacRae CA, Liao R. Human amyloidogenic light chain proteins result in cardiac dysfunction, cell death, and early mortality in zebrafish. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2013;305:H95–103. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00186.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon A, Weiss DT, Pepys MB. Induction in mice of human light-chain-associated amyloidosis. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:629–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward JE, Ren R, Toraldo G, Soohoo P, Guan J, O'Hara C, Jasuja R, Trinkaus-Randall V, Liao R, Connors LH, Seldin DC. Doxycycline reduces fibril formation in a transgenic mouse model of AL amyloidosis. Blood. 2011;118:6610–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-351643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teng MH, Yin JY, Vidal R, Ghiso J, Kumar A, Rabenou R, Shah A, Jacobson DR, Tagoe C, Gallo G, Buxbaum J. Amyloid and nonfibrillar deposits in mice transgenic for wild-type human transthyretin: a possible model for senile systemic amyloidosis. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2001;81:385–96. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]