Abstract

With successful antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the US, HIV-positive adults now routinely survive into old age. However, increased life expectancy with HIV introduces the added complication of age-related cognitive decline. Aging with HIV has been associated with poorer cognitive outcomes compared to HIV-negative adults. While up to 50% of older HIV-positive adults will develop some degree of cognitive impairment over their lifetime, cognitive symptoms are often not consistently monitored, until those symptoms are significant enough to impair daily life. In this study we found that subjective memory complaint (SMC) ratings correlated with measurable memory performance impairments in HIV-positive adults, but not HIV-negative adults. As the HIV-positive population ages, structured subjective cognitive assessment may be beneficial to identify the early signs of cognitive impairment, and subsequently allow for earlier interventions to maintain cognitive performance as these adults continue to survive into old age.

Keywords: HIV-1, Aging, Memory, Cognition, Subjective Memory Impairment

Introduction

Nearly 50% of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-positive individuals in the US are now aged 50 or older (Vance, McGuinness, Musgrove, Orel, & Fazeli, 2011). Both older age and HIV increase the risk of cognitive dysfunction, though it's unclear whether or not the two interact (Ances, Ortega, Vaida, Heaps, & Paul, 2012; Becker, Lopez, Dew, & Aizenstein, 2004; Bhatia, Ryscavage, & Taiwo, 2011; Iudicello, Paul Woods, Deutsch, Grant, & Group, 2012; Manly et al., 2011; Morgan et al., 2012). Additionally, older age is associated with higher risk of depression and anxiety (Kohler, Thomas, Barnett, & O'Brien, 2010), which can further worsen cognition (Alexopoulos, Kiosses, Klimstra, Kalayam, & Bruce, 2002; Lockwood, Alexopoulos, & van Gorp, 2002; Wang et al., 2008). Identifying markers of cognitive vulnerability would allow intervention before symptoms significantly affect daily life.

Subjective memory complaints (SMCs) may have particular clinical value in adults undergoing pathological aging processes. SMCs were shown to correlate with informants' memory rating in adults diagnosed with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or dementia (Abner, Kryscio, Caban-Holt, & Schmitt, 2015; Buckley et al., 2015; Salem, Vogel, Ebstrup, Linneberg, & Waldemar, 2015), and to correlate with subjective mood (Yates, Clare, Woods, & Matthews, 2015). SMCs have also been associated with poorer verbal episodic memory performance (Gifford et al., 2015). However, previous studies in HIV have found stronger association between SMCs and mood (Au et al., 2008; van Gorp et al., 1991) rather than with cognitive performance.

We examined if SMC ratings correlated with objective memory performance in HIV-positive and -negative adults. We hypothesized that SMC ratings would correlate with objective impairments more significantly in HIV-positive adults than controls.

Methods

Participants

We enrolled 35 HIV-positive and 21 HIV-negative adults (n=56). Groups were similar with respect to race, sex, age, and education (Table 1). Participants endorsing current substance abuse (alcohol, cocaine, opiates) or HIV-positive participants not on Anti-Retroviral Therapy were excluded. Participants gave informed consent, approved by the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board and Human Research Protection Program.

Table 1.

Descriptive, Behavioral and Cognitive Results, HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Groups. Data presented as Mean (St. Dev).

| HIV-Positive | HIV-Negative | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N=35 | N=21 | p-value | |

| Gender (% Male) | 57.1 | 47.6 | 0.584 |

| Race (%White) | 42.9 | 61.9 | 0.270 |

| Years of Education | 14.0 | 15.61 | 0.083 |

| Age | 49.1 (11.5) | 46.6 (13.5) | 0.459 |

| Minimum-Maximum Age | 26-76 | 23-69 | - |

| CD4 Nadir | 395.6 (209.6) | - | - |

| CD4 Current | 754.3 (494.8) | - | - |

| MFQ Score | 275.1 (87.6) | 286.4 (54.9) | 0.600 |

| BDI Score | 18.6 (11.0) | 13.7 (8.1) | 0.081 |

| BAI Score | 18.2 (13.3) | 12.9 (144) | 0.165 |

| Detection Accuracy | 1.38 (0.25) | 1.48 (0.11) | 0.087 |

| Identification Accuracy | 1.30 (0.25) | 1.37 (0.14) | 0.344 |

| One-Card Learning Accuracy | 0.88 (0.07) | 0.98 (0.09) | **< 0.001 |

| Groton Maze Duration (s) | 11456 (6416) | 56.92 (22.52) | **< 0.001 |

| Groton Maze (moves per second) | 0.34 (0.18) | 0.56 (0.20) | **< 0.001 |

| SRT-Total Recall | 49.18 (16.44) | 75.00 (28.06) | **< 0.001 |

| SRT-Total Recall (Delay) | 5.61 (3.37) | 9.52 (5.06) | *0.002 |

| SRT-Total Consistency | 7.00 (0.79) | 7.38 (0.81) | 0.098 |

| SRT-First 4 Recall | 20.96 (6.03) | 31.52 (12.08) | **< 0.001 |

| SRT-Last 4 Recall | 28.21 (11.09) | 43.47 (15.50) | **< 0.001 |

| SRT-First 4 Consistency | 10.47 (1.73) | 7.35 (3.69) | **< 0.001 |

| SRT-Last4 Consistency | 440 (1.93) | 7.40 (3.23) | **< 0.001 |

: significant at p<0.05 level

: significant at p<0.001 level

Memory and Mood Measures

The Memory Functioning Questionnaire (MFQ) is a 64-item subjective survey of current memory problems, rated from 1-7. (Gilewski & Zelinski, 1988). The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) are 21-item self-report questionnaires, measuring incidence and severity of current depressive/anxiety symptoms, rated from 0-3 (Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961). For the MFQ, BDI and BAI, participants answered regarding the previous 30 days, including their study day.

Cognitive Tasks

Tasks were chosen for reliability in accurately assessing episodic and working memory, executive functioning and attention. The Selective Reminding Task (SRT) measures episodic verbal memory (Buschke, 1973). Participants are read a list of sixteen (16) words and asked to recall as many as possible. Participants completed eight (8) immediate recall trials. Before each trial, experimenter re-reads only the words that the participant failed to recall. Recall and Recall Consistency (words recalled in two (2) sequential trials without reinforcement) were recorded. Participants completed a Delayed Recall trial after approximately 25 minutes.

Participants completed four (4) CogState tasks (Fredrickson et al., 2010) previously used in HIV-positive adults (Boivin et al., 2010; Cysique, Maruff, Darby, & Brew, 2006; Thiyagarajan et al., 2010; Winston et al., 2012): Groton Maze (executive functioning), Detection (psychomotor functioning), Identification (visual attention), and One-Card Learning (working memory).

Data Analysis

Group means were calculated for age, BDI/ BAI Scores, MFQ Score, and cognitive performance measures, and compared using independent samples t-tests. In the HIV-positive group, mean CD4+ T-cell nadir and current CD4+ counts were obtained from medical records (Ellis et al., 2011). For the SRT, Total Recall and Recall Consistency were calculated for the full 8-trial task (SRT-T), as well as for first four (SRT-F) and last four (SRT-L) trials.

“Accuracy” on the CogState tasks was defined as an arcsine transformation of the proportion of correct to incorrect responses. Pearson Correlations (2-tailed) were calculated between MFQ score, age, BDI/BAI score, SRT-T, SRT-F and SRT-L performance measures, CogState accuracy measures; and in the HIV-positive group, CD4+ nadir. Multiple regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the relationship of MFQ and BDI scores to Total Recall on the SRT-T.

Results

Group means and standard deviations for the descriptive, behavioral, and cognitive data can be found in Table 1. There were no significant group differences in age or education. Mean BDI, BAI, and MFQ scores were not significantly different between groups.

HIV-negative participants had significantly higher Total Recall on the SRT-T compared to HIV-positive participants (t=4.270, p< 0.001), while SRT-T Recall Consistency was not significantly different between groups. HIV-negative participants also showed significantly higher Delayed Recall compared to HIV-positive participants (t= 3.330, p= 0.002).

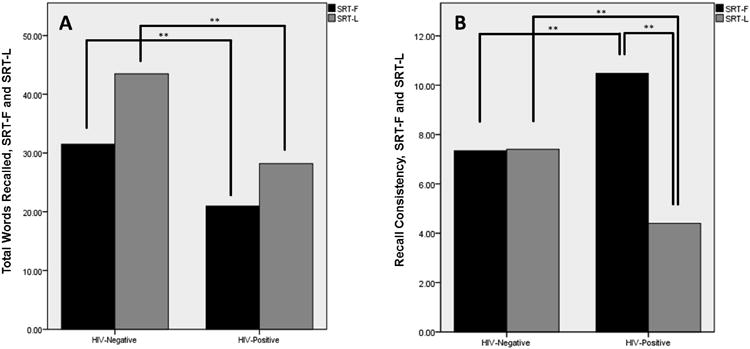

When SRT immediate performance was split between the first four (SRT-F) and last four (SRT-L) trials, Recall and Recall Consistency were significantly different between groups on the first four (SRT-F Recall t=4.026, p< 0.001; SRT-F Consistency t= -4.21, p< 0.001) and last four (SRT-L Recall t=4.218, p< 0.001; SRT-L Consistency t=4.275, p< 0.001) trials, shown in Figure 1. Paired t-tests revealed that differences in Recall Consistency between SRT-F and SRT-L were significantly different in the HIV-positive group (t= 10.340, p< 0.001), but not in the HIV-negative group.

Figure 1.

SRT-F and SRT-L Recall and Recall Consistency, by Serostatus Groups. (**: significant at p < 0.001 level). There were significant differences between Recall in the first four (SRT-F) and last four (SRT-L) trials in both serostatus groups. Recall Consistency between SRT-F and SRT-L was significantly different in the HIV-positive, but not HIV-negative group.

HIV-positive participants showed significantly lower accuracy on the One Card Learning (OCL) Task than HIV-negative participants (t= 4.07, p< 0.001). The HIV-positive group completed the Groton Maze (GML) significantly slower than the HIV-negative group (t= -3.848, p< 0.001), with significantly fewer moves per second (t= 4.182, p< 0.001). No other CogState measures were significantly different between groups.

MFQ score was significantly correlated with BDI and BAI ratings in both the HIV-negative (MFQ × BDI corr= -0.618, p=0.003; MFQ × BAI corr= -0.466, p<0.001) and HIV-positive (MFQ × BDI corr = -0.579, p=0.03; MFQ × BAI corr = -0.630, p<0.001) groups. MFQ score was significantly correlated with SRT-T Recall in both the HIV-negative (MFQ × SRT-T corr= 0.499, p= 0.021) and HIV-positive (MFQ × SRT-T corr= 0.432, p= 0.012) groups. Delayed Recall performance was significantly correlated with MFQ score in the HIV-positive (MFQ × SRT-T Delay corr= 0.548, p= 0.002), but not the HIV-negative group.

There were no significant correlations between mood ratings or MFQ and age, in either group. Age was significantly correlated with SRT-T Recall and Delayed Recall in the HIV-negative group (age × SRT-T corr= -0.492, p=0.024; age × SRT-T Delay corr= -0.546, p= 0.010), but not the HIV-positive group. There were no sex differences in MFQ scores in either group, or correlations between current or nadir CD4+ count and any cognitive measures.

MFQ score was significantly correlated with OCL accuracy in the HIV-positive group (MFQ × OCL corr = 0.414, p = 0.025) but not in the HIV-negative group. No other measures of the CogState were significantly different between serostatus groups, or correlated with SMCs.

Despite statistically insignificant differences in BDI score between groups, regression analysis showed that in a model including MFQ and BDI scores, BDI explained a significant portion of performance variance on the SRT-T Recall in the HIV-negative group (F(2,18)=6.36, Sig = 0.008, BDI beta = -0.516, MFQ beta = 0.180), whereas in the HIV-positive group, MFQ explained a significant portion of variance in SRT-T Recall (F(2,30)=3.45, Sig = 0.045, BDI beta = 0.23, MFQ beta = 0.446).

Discussion

The HIV-positive participants in this study had significantly lower scores on verbal episodic memory (SRT) and recognition working memory (OCL) tasks compared to HIV-negative participants. Previous studies have linked episodic memory failures in HIV to the loss of fronto-striatal white matter and hippocampal volume (Castelo, Sherman, Courtney, Melrose, & Stern, 2006; Pfefferbaum et al., 2014), impairing memory storage and retrieval, which may be the underlying mechanisms in this HIV-positive group. On the SRT, differences in Recall Consistency between early and late trials of the task may reflect impairment in transferring encoded information from short- to long-term storage.

Prior studies have shown strong correlations between SMCs and mood ratings (van Gorp et al., 1991). However in this study, SMC scores accounted for a greater portion of SRT performance variance. This may indicate that in HIV-positive adults, SMCs may be a more salient marker of actual cognitive deficits than in HIV-negatives, and may deserve closer monitoring. A unique property of this sample was similar depression ratings between groups. Because of the higher proportion of mood disorders in HIV-positive adults, it may be more clinically relevant to compare HIV-positive populations to controls with higher mood ratings, to examine the effects of serostatus alone.

Our results support the use of SMCs as a marker to identify memory impairments in adults experiencing pathological aging processes, versus “normal” age-related cognitive changes. This is an important distinction, since studies of cognitively normal adults have found little to no correlation between SMCs and performance (Abner et al., 2015; Dalla Barba, La Corte, & Dubois, 2015; Fritsch, McClendon, Wallendal, Hyde, & Larsen, 2014; Howieson et al., 2015; Hulur, Hertzog, Pearman, Ram, & Gerstorf, 2014). Our positive results may also be due to the more thorough SMC measure used versus other common SMC instruments. The MFQ's more detailed query of memory may more accurately portray deficits in memory function.

Our design was insufficient to explore biochemical factors of HIV infection and treatment that may affect cognition and mood. Relative CNS penetrance of different ARTs (Decloedt, Rosenkranz, Maartens, & Joska, 2015; Skinner, Adewale, DeBlock, Gill, & Power, 2009), ART neurotoxicity (Akay et al., 2014; Underwood, Robertson, & Winston, 2015), mood disorders (Dal-Bo et al., 2015; Silveira et al., 2012), substance abuse history (Byrd et al., 2011) and length and severity of HIV infection (Heaton et al., 2015) can all negatively affect cognitive performance in aging HIV-positive adults, and fluctuate over time (Dawes et al., 2008). Accounting for these differences in disease and treatment are necessary to further specify individual risk factors for cognitive changes.

Conclusions

This study showed that memory performance was significantly different between HIV-negative and -positive adults, and that in HIV-positive adults, SMCs correlated with episodic and working memory performance. Differences in SMCs and memory performance were not explained solely by depressive symptoms. This data indicate that measuring SMCs may have clinical value, to monitor cognitive changes in HIV-positive adults. Adding structured SMC measures to routine assessments may help identify those who should be more closely monitored for HAND symptoms, leading to earlier, more effective interventions for adults aging with HIV.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, under CTSA Award No. UL1TR000445. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by the National Institutes of Health, under The National Aging Institute grant #1R01 AG047992-01A1 (P. N.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abner EL, Kryscio RJ, Caban-Holt AM, Schmitt FA. Baseline subjective memory complaints associate with increased risk of incident dementia: the PREADVISE trial. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2015;2(1):11–16. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akay C, Cooper M, Odeleye A, Jensen BK, White MG, Vassoler F, et al. Jordan-Sciutto KL. Antiretroviral drugs induce oxidative stress and neuronal damage in the central nervous system. J Neurovirol. 2014;20(1):39–53. doi: 10.1007/s13365-013-0227-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos GS, Kiosses DN, Klimstra S, Kalayam B, Bruce ML. Clinical presentation of the “depression-executive dysfunction syndrome” of late life. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;10:98–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ances BM, Ortega M, Vaida F, Heaps J, Paul R. Independent Effects of HIV, Aging, and HAART on Brain Volumetric Measures. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(5):469–477. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318249db17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au A, Cheng C, Chan I, Leung P, Li P, Heaton RK. Subjective memory complaints, mood, and memory deficits among HIV/AIDS patients in Hong Kong. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2008;30(3):338–348. doi: 10.1080/13803390701416189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JT, Lopez OL, Dew MA, Aizenstein HJ. Prevalence of cognitive disorders differs as a function of age in HIV virus infection. AIDS. 2004;18(1):S11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia R, Ryscavage P, Taiwo B. Accelerated aging and human immunodeficiency virus infection: Emerging challenges of growing older in the era of successful antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol. 2011:247–255. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0073-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin MJ, Busman RA, Parikh SM, Bangirana P, Page CF, Opoka RO, Giordani B. A pilot study of the neuropsychological benefits of computerized cognitive rehabilitation in Ugandan children with HIV. Neuropsychology. 2010;24(5):667–673. doi: 10.1037/a0019312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley R, Saling M, Ellis K, Rowe C, Maruff P, Macaulay LS, et al. Ames D. Self and informant memory concerns align in healthy memory complainers and in early stages of mild cognitive impairment but separate with increasing cognitive impairment. Age Ageing. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschke Herman. Selective reminding for analysis of memory and learning. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1973;12(5):543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd DA, Fellows RP, Morgello S, Franklin D, Heaton RK, Deutsch R, et al. Group, Charter. Neurocognitive impact of substance use in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(2):154–162. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318229ba41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelo JM, Sherman SJ, Courtney MG, Melrose RJ, Stern CE. Altered hippocampal-prefrontal activation in HIV patients during episodic memory encoding. Neurology. 2006;66(11):1688–1695. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000218305.09183.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cysique LA, Maruff P, Darby D, Brew BJ. The assessment of cognitive function in advanced HIV-1 infection and AIDS dementia complex using a new computerised cognitive test battery. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;21(2):185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal-Bo MJ, Manoel AL, Filho AO, Silva BQ, Cardoso YS, Cortez J, et al. Silva RM. Depressive Symptoms and Associated Factors among People Living with HIV/AIDS. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14(2):136–140. doi: 10.1177/2325957413494829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Barba G, La Corte V, Dubois B. For a Cognitive Model of Subjective Memory Awareness. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(1):S57–61. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes S, Suarez P, Casey CY, Cherner M, Marcotte TD, Letendre S, et al. Group, Hnrc. Variable patterns of neuropsychological performance in HIV-1 infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2008;30(6):613–626. doi: 10.1080/13803390701565225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decloedt EH, Rosenkranz B, Maartens G, Joska J. Central nervous system penetration of antiretroviral drugs: pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and pharmacogenomic considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2015;54(6):581–598. doi: 10.1007/s40262-015-0257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Badiee J, Vaida F, Letendre S, Heaton RK, Clifford D, et al. Grant I. CD4 nadir is a predictor of HIV neurocognitive impairment in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2011;25(14):1747–1751. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834a40cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson J, Maruff P, Woodward M, Moore L, Fredrickson A, Sach J, Darby D. Evaluation of the usability of a brief computerized cognitive screening test in older people for epidemiological studies. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;34(2):65–75. doi: 10.1159/000264823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch T, McClendon MJ, Wallendal MS, Hyde TF, Larsen JD. Prevalence and Cognitive Bases of Subjective Memory Complaints in Older Adults: Evidence from a Community Sample. J Neurodegener Dis. 2014;2014:176843. doi: 10.1155/2014/176843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford KA, Liu D, Damon SM, Chapman WG, th, Romano RR, Iii, Samuels LR, et al. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging, Initiative. Subjective memory complaint only relates to verbal episodic memory performance in mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44(1):309–318. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilewski MJ, Zelinski EM. Memory Functioning Questionnaire (MFQ) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24(4):665–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Jr, Deutsch R, Letendre S, Ellis RJ, Casaletto K, et al. Group, Charter. Neurocognitive change in the era of HIV combination antiretroviral therapy: the longitudinal CHARTER study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(3):473–480. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howieson DB, Mattek N, Dodge HH, Erten-Lyons D, Zitzelberger T, Kaye JA. Memory Complaints in Older Adults: Prognostic Value and Stability in Reporting over Time. SAGE Open Med. 2015;3 doi: 10.1177/2050312115574796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulur G, Hertzog C, Pearman A, Ram N, Gerstorf D. Longitudinal associations of subjective memory with memory performance and depressive symptoms: between-person and within-person perspectives. Psychol Aging. 2014;29(4):814–827. doi: 10.1037/a0037619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iudicello JE, Paul Woods S, Deutsch R, Grant I Group, HNRP. Combined effects of aging and HIV infection on semantic verbal fluency: A view of the cortical hypothesis through the lens of clustering and switching. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012 doi: 10.1080/13803395.2011.651103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler S, Thomas AJ, Barnett NA, O'Brien JT. The pattern and course of cognitive impairment in late-life depression. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(4):591–602. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood KA, Alexopoulos GS, van Gorp WG. Executive dysfunction in geriatric depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1119–1126. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Smith C, Crystal HA, Richardson J, Golub ET, Greenblatt R, et al. Young M. Relationship of ethnicity, age, education, and reading level to speed and executive function among HIV+ and HIV- women: the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Neurocognitive Substudy. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2011;33(8):853–863. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.547662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EE, Iudicello JE, Weber E, Duarte NA, Riggs PK, Delano-Wood L, et al. Group, H.I.V. Neurobehavioral Research Program. Synergistic effects of HIV infection and older age on daily functioning. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(3):341–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826bfc53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Rogosa DA, Rosenbloom MJ, Chu W, Sassoon SA, Kemper CA, et al. Sullivan EV. Accelerated aging of selective brain structures in human immunodeficiency virus infection: a controlled, longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(7):1755–1768. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem LC, Vogel A, Ebstrup J, Linneberg A, Waldemar G. Subjective cognitive complaints included in diagnostic evaluation of dementia helps accurate diagnosis in a mixed memory clinic cohort. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1002/gps.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira MP, Guttier MC, Pinheiro CA, Pereira TV, Cruzeiro AL, Moreira LB. Depressive symptoms in HIV-infected patients treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2012;34(2):162–167. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462012000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner S, Adewale AJ, DeBlock L, Gill MJ, Power C. Neurocognitive screening tools in HIV/AIDS: comparative performance among patients exposed to antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2009;10(4):246–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiyagarajan A, Garvey LJ, Pflugrad H, Maruff P, Scullard G, Main J, et al. Winston A. Cerebral function tests reveal differences in HIV-infected subjects with and without chronic HCV co-infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16(10):1579–1584. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood J, Robertson KR, Winston A. Could antiretroviral neurotoxicity play a role in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment in treated HIV disease? AIDS. 2015;29(3):253–261. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gorp WG, Satz P, Hinkin C, Selnes O, Miller EN, McArthur J, et al. Paz D. Metacognition in HIV-1 seropositive asymptomatic individuals: self-ratings versus objective neuropsychological performance. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1991;13(5):812–819. doi: 10.1080/01688639108401091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance DE, McGuinness T, Musgrove K, Orel NA, Fazeli PL. Successful aging and the epidemiology of HIV. Clin Interv Aging. 2011;6:181–192. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S14726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Krishnan KR, Steffens DC, Potter GG, Dolcos F, McCarthy G. Depressive state- and disease-related alterations in neural responses to affective and executive challenges in geriatric depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):863–871. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07101590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston A, Puls R, Kerr SJ, Duncombe C, Li PC, Gill JM, et al. Altair Study, Group. Dynamics of cognitive change in HIV-infected individuals commencing three different initial antiretroviral regimens: a randomized, controlled study. HIV Med. 2012;13(4):245–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates JA, Clare L, Woods RT, Matthews FE. Subjective Memory Complaints are Involved in the Relationship between Mood and Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(1):S115–123. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]