Abstract

Objective

To describe the significance of aortic root distortion (AD) and/or aortic valve insufficiency (AI) during balloon angioplasty of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) performed to rule out coronary artery compression prior to transcatheter pulmonary valve (TPV) implantation.

Methods

AD/AI were assessed by retrospective review of all procedural aortographies performed to evaluate coronary anatomy prior to TPV implantation. AD/AI was also reviewed in all pre-post MPV implant echocardiograms to assess for progression.

Results

From 04/2007 to 3/2015, 118pts underwent catheterization with intent for TPV implant. Mean age and weight were 24.5 ± 12 years and 64.3 ± 20 kg respectively. Diagnoses were: TOF (53%), D-TGA/DORV (18%), s/p Ross (15%), and Truncus (9%). Types of RV-PA connections were: conduits (96), bioprosthetic valves (14), and other (7). Successful TPV implant occurred in 91pts (77%). RVOT balloon angioplasty was performed in 43/118pts (36%). Aortography was performed in 18/43pts with AD/AI noted in 6/18 (33%); two with D-TGA (1 s/p Lecompte, 1 s/p Rastelli), 2 with TOF, 1 Truncus and 1 s/p Ross. Procedure was aborted in the 2 who developed severe AD/AI. TPV was implanted in 3/4 pts with mild AD/AI. Review of pre-post TPV implantation echocardiograms in 83/91pts (91%) revealed no new/worsened AI in any pt.

Conclusion

AD/AI is relatively common on aortography during simultaneous RVOT balloon angioplasty. Lack of AI progression by echocardiography post-TPV implant suggests these may be benign findings in most cases. However, AD/AI should be carefully evaluated in certain anatomic subtypes with close RVOT/aortic alignments.

Keywords: Congenital heart disease, Transcatheter heart valve, Pulmonary heart disease, Coronary compression

INTRODUCTION

Since it was first approved in the US in 2010, transcatheter pulmonary valve (TPV) replacement with the Melody™ valve (Medtronic Corp., Minneapolis, MN) has become accepted as an important tool in the management of postoperative right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) obstruction and pulmonary valve regurgitation (1–6). A number of reports have emphasized the importance of determining the potential risk of coronary artery compression prior to implantation of a stent or TPV (7–10). Balloon angioplasty of the RVOT with simultaneous aortic and/or coronary artery angiography has been established as the most accurate maneuver to evaluate for risk of coronary artery compression. Although coronary artery compression can have catastrophic consequences (7,8), significant compression of other structures in close proximity to the RVOT, including the aortic root, sinuses of Valsalva or ascending aorta, can occur as well, and may also constitute important contraindications for TPV implantation. Significant distortion of the aortic root, aortic valve insufficiency (AI), and pulmonary artery (PA) to aorta fistulas following Melody™ TPV implant have been reported (11,12). However, data regarding the potential risks and clinical implications of aortic root distortion and/or AI during RVOT balloon sizing/dilation are limited. In this article, we report the characteristics, management and outcomes of patients who developed aortic root distortion and/or AI on aortic angiography during simultaneous RVOT balloon inflation to rule out coronary artery compression prior to Melody™ TPV implantation.

METHODS

Patients

We reviewed the medical records and catheterization data of all patients who underwent heart catheterization with the intention of implanting a Melody™ TPV at our institution from April 2007 through March 2015. Aortic root and/or selective coronary angiography was performed in all patients to characterize the coronary artery anatomy, and to define the relationship between the coronary arteries and the RVOT to assess the risk of coronary artery compression during Melody™ TPV implantation. Aortic and/or selective coronary angiography performed simultaneously with balloon inflation/sizing of the RVOT was performed in selected cases where a coronary artery and the RVOT were in close proximity or the coronary was otherwise felt to be at risk for compression. Type of angiography (selective coronary vs aortic angiography or both) and balloon size/lenght used for coronary compression testing was determined by the operator based on personal preference and individual patient anatomy.

Evaluation of aortic root distortion and AI

The subset of patients who underwent RVOT balloon inflation with simultaneous aortic angiography formed the current study group. In that cohort, angiograms were reviewed to assess for aortic root distortion and new or increased AI during balloon inflation, as well as after pre-stents and TPV implantation if applicable. Aortic root distortion was considered severe when an entire aortic sinus of Valsalva was flattened and mild if only part of it was compressed or distorted on any angiographic projection. The presence of new or worsening AI in association with root distortion was reported but not graded. The baseline anatomy, type of surgical repair, type of RVOT reconstruction, indication for TPV implantation and relationship between the sternum and the RVOT were compared between patients who did and did not develop aortic root distortion. Pre- and post-procedure echocardiograms of all patients who underwent TPV implantation were reviewed to assess for residual aortic root compression and new or worsened AI. The degree of AI on echocardiography was graded as none, trivial, mild, moderate or severe based on standard criteria. In those patients in whom a stent was implanted in the RVOT prior to the Melody™ TPV implantation procedure, the angiograms and echocardiograms of both procedures were reviewed.

Data analysis

The data were presented as mean ± SD or median and range as appropriate. Due to the small number of events, data were primarily presented in descriptive fashion. T- test analysis was used to compare normally distributed continuous variables between groups. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test.

RESULTS

Patients

During the study period, 118 patients underwent heart catheterization with the intention of implanting a Melody™ TPV at our institution. The mean age was 24.5 years (± 12) and the mean weight was 64.3 kg (± 20). Demographic and anatomic data are shown in Table 1. Most RVOT repairs included a conduit in 96 patients (81%) or prosthetic valve in 14 (12%), but a small cohort underwent direct connection of the RV to the pulmonary arteries (13–14). The median conduit diameter at the time of surgical implant was 22mm (16–27). In 6 patients, the size of the conduit was unknown. A Melody™ TPV was successfully implanted in 91 patients (77%). There were no intra-procedural deaths

Table 1.

Demographic and Diagnostic Data in Patients Catheterized for Intended Melody Valve Implant

| Total (n = 118) | CA Compression Testing With Aortic Angiogram | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Yes (n = 18) | No (n = 100) | |||

| Age (yrs) | 25 ± 12 | 19 ± 10 | 26 ± 12 | 0.024 |

| Weight (kg) | 64 ± 20 | 67 ± 26 | 64 ± 19 | 0.491 |

| Underlying cardiac diagnosis | 0.057 | |||

| TOF | 63 (53%) | 6 (33%) | 57 (57%) | |

| D-TGA/DORV | 21 (18%) | 6 (33%) | 15 (15%) | |

| Rastelli | 3 | 13 | ||

| Arterial switch | 2 | 0 | ||

| Damus-Kaye-Stansel | 0 | 1 | ||

| Other | 1 | 1 | ||

| AS prior Ross procedure | 17 (15%) | 3 (17%) | 14 (14%) | |

| Truncus arteriosus | 10 (9%) | 1 (6%) | 9 (9%) | |

| L-TGA | 4 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 4(4%) | |

| Pulmonary stenosis/atresia | 2 (2%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Other | 1 (1%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| RVOT anatomy | 0.165 | |||

| Conduit | 96 (81%) | 12 (67%) | 14 (14%) | |

| Bioprosthetic valve | 14 (12%) | 3 (17%) | 11 (11%) | |

| Other/unknown | 3 (3%) | 1 (6%) | 2 (2%) | |

| Direct RV-PA anastomosis | 3 (3%) | 2 (11%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Transannular patch (stenosis) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Unrepaired (TOF-absent valve) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

AS, aortic valve stenosis; CA, coronary artery; D/L-TGA, D/L-transposition of the great arteries; DORV, double outlet right ventricle; PA, pulmonary artery; TOF, tetralogy of fallot, Data are presented as mean ± SD or number (% of total).

Coronary Artery Evaluation

Baseline angiography to evaluate coronary artery anatomy and its relationship with the RVOT was performed in all patients. Aortic angiography only was performed in 54 patients (46%), aortic angiography followed selective coronary artery angiography in 47 (40%), and selective coronary artery angiography only in 17 (14%). RVOT balloon angioplasty with simultaneous angiography (i.e. coronary artery compression testing) was performed in 43 of 118 patients (36%) based on perceived coronary compression risk. In 18 of these 43 patients, coronary compression testing was performed with aortic angiography, whereas the rest had only selective coronary angiography. Among the 25 patients in whom only selective coronary angiography was performed, 19 were performed to assess the left coronary artery and 6 the right. A flow diagram of coronary artery evaluation is shown in Fig 1. There was no statistical difference in age, weight, cardiac diagnosis and type of RVOT repair between patients who underwent coronary compression testing and those who did not.. Among the patients who underwent coronary artery compression testing, those who underwent aortic angiography were younger than the coronary angiography only group (18.4 years vs 29.2 years, p=0.005), but other variables were similar. Details of the surgical procedures, anatomy, balloon size used for testing and balloon/RVOT ratio of the 18 patients who underwent coronary artery compression testing and comprise the study group, are summarized in Table 2.

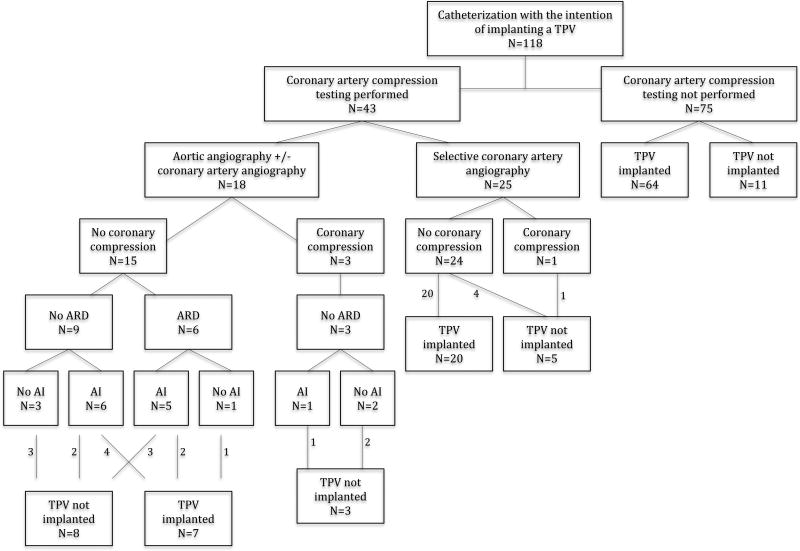

Figure 1.

Outcomes based on coronary artery evaluation

AI: aortic valve insufficiency, ARD: aortic root distortion, TPV: transcatheter pulmonary valve

TABLE 2.

Details of Patients Who Underwent RVOT balloon Angioplasty and Simultaneous Aortic Angiography (n=18)

| Aortic Root Distortion | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt. No. |

Age (yrs)/ Weight (kg) |

Diagnosis | Previous Procedures |

Main Indication for TPV implant |

Balloon Diameter/ Length |

Balloon/ RVOT ratio |

Distortion Severity |

AI New/Worsen (during inflation) |

RVOT Directly Retrosternal |

RVOT prestented |

Valve Implanted/ Reason |

| 1 | 10/46.8 | D-TGA/VSD PS | Cylinder of autogenous aorta used as RVOT conduit Lecompte Maneuver | RVOT Obstruction | Atlas 16mm/2cm | N/A | Severe | Yes | Yes | N/A | No/Aortic distortion/AI |

| 2 | 26/83 | TOF/PA | Direct RV-PA anastomosis | Pulmonary Insufficiency | Z-med II 20mm/4cm | N/A | Mild | Yes | No | N/A | No/Unsuitable RVOT anatomy; protrusion of LPA stent into RVOT |

| 3 | 14/54.9 | D-TGA/VSD PS | Rastelli procedure 21mm aortic homograft | RVOT Obstruction | Atlas 20mm/2cm | 0.9 | Severe | Yes | Yes | N/A | No/Aortic distortion with AI |

| 4 | 35/114.2 | TOF | 25mm homograft (unknown type) | RVOT Obstruction | Z-med II 25mm/4cm | 1 | Mild | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | 7/36.5 | Aortic valve stenosis | Ross procedure 16mm homograft (unknown type) | RVOT Obstruction | Atlas 16mm/2cm | 1 | Mild | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 6 | 13/70.3 | Truncus | Direct RV-PA anastomosis | RVOT Obstruction | Atlas 18mm/2cm | N/A | Mild | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| No Distortion | |||||||||||

| 7 | 24/76.5 | DORV | Rastelli procedure 20mm homograft (unknown type) | RVOT Obstruction | Atlas 16mm/2cm | 0.8 | N/A | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | 23/64.6 | D-TGA/VSD | Rastelli procedure, Carpentier-Edwards bioprosthetic valve 25mm | Mixed | Atlas 22mm/2cm | 0.9 | N/A | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 9 | 38/97 | TOF | 25mm pulmonary homograft | Pulmonary Insufficiency | Z-med II 25mm/4cm | 1 | N/A | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | 17/64.4 | PA | Carpentier-Edwards bioprosthetic valve 23mm | Mixed | Z-med II 25mm/4cm | 1.1 | N/A | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | 9/20.9 | TOF/PA | Mitroflow bioprostethic valve 19mm | Mixed | Atlas 16mm/2cm | 0.9 | N/A | No | No | No | Yes |

| 12 | 17/106.5 | D-TGA | Arterial Switch/ Lecompte maneuver 22 mm homograft (unknown type) | RVOT Obstruction | Z-med II 18mm/3cm | 0.8 | N/A | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | 8/29 | DORV | Arterial Switch/Lecompte maneuver 18mm Contegra | RVOT Obstruction | Atlas 18mm/2cm | 1 | N/A | No | Yes | N/A | No/Coronary compression |

| 14 | 17/71.9 | TOF/PA | 19mm aortic homograft | RVOT Obstruction | Atlas 16mm/2cm | 0.9 | N/A | No | No | N/A | No/Coronary compression |

| 15 | 36/97.7 | TOF | 24mm pulmonary homograft | Mixed | Z-med II 20mm/4cm | 0.8 | N/A | Yes | No | N/A | No/Conduit tear |

| 16 | 9/39.7 | Aortic valve stenosis | Ross procedure 17mm pulmonary homograft | Mixed | Z-med II 25mm/3cm | 1.5 | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | No/Coronary compression |

| 17 | 22/70.3 | Aortic valve stenosis | Ross procedure 22mm aortic homograft | RVOT Obstruction | Atlas 16mm/2cm | 0.7 | N/A | Yes | No | N/A | No/Conduit tear/Covered stent |

| 18 | 9/67.8 | Aortic Atresia VSD | Rastelli 18mm pulmonary homograft | RVOT Obstruction | Vida 14mm/2cm | 0.8 | N/A | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

D-TGA= D-Transposition of the Great Arteries, VSD=Ventricular Septal Defect, PS=Pulmonary Valve Stenosis, TOF= Tetralogy of Fallot, RVOT=Right Ventricular Outflow Tract, AI=Aortic Valve Insufficiency, RV-PA= Right Ventricle-Pulmonary Artery, PA= Pulmonary Valve Atresia, Z-med II (B. Braun Interventional, Bethlehem, PA), Atlas/Vida (Bard Peripheral Vascular, Tempe, AZ)

Aortic Root Distortion and Aortic Insufficiency

Aortic root distortion during balloon inflation in the RVOT was noted in 6 of the 18 (33%) patients, and new or worsening AI was noted in 5 of the 6 patients with root distortion.

Aortic root distortion was considered severe in 2 patients (patients 1 and 3), and the procedure was aborted in both (Figures 2–4). Both patients had transposition of the great arteries with a ventricular septal defect and pulmonary stenosis, and had RVOT conduits that were located immediately retrosternal (Table 2).

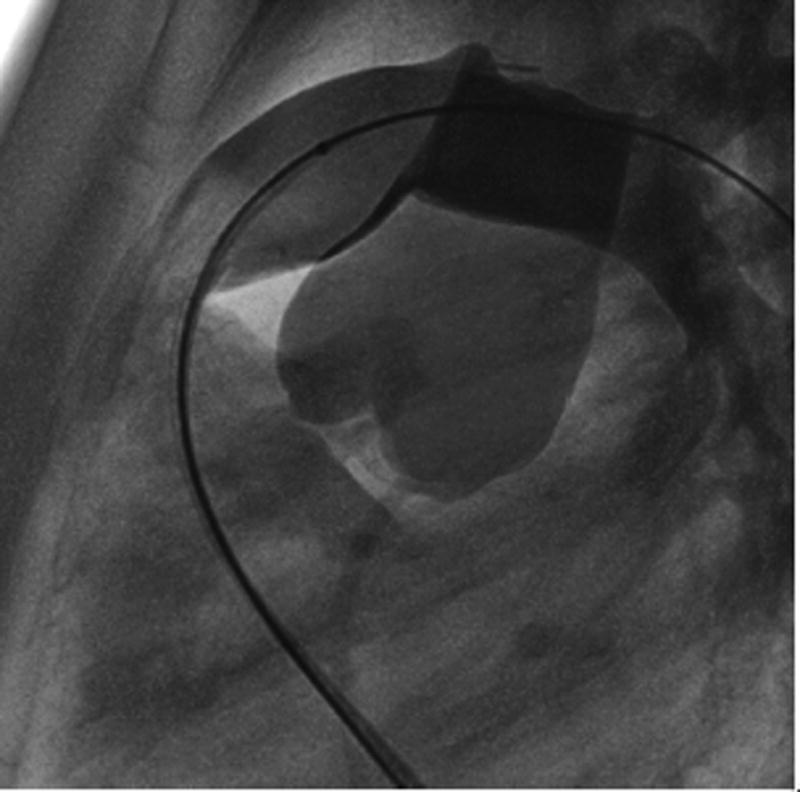

Figure 2.

Patient 1. Superimposed image of the RVOT and ascending aorta angiograms showing the close proximity between the two vessels.

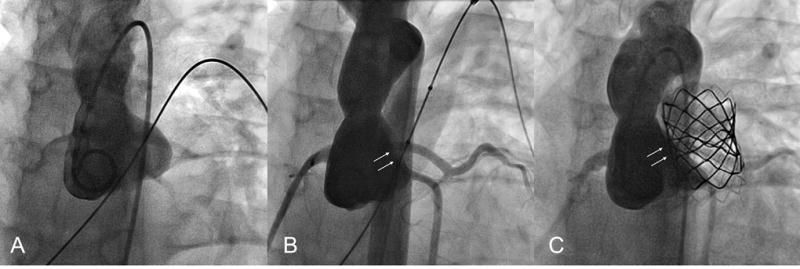

Figure 4.

Patient 2. A. Severe distortion of the aortic root during ascending aorta angiogram with simultaneous balloon inflation in the RVOT (balloon filled with very diluted contrast in order to visualize the coronary artery and rule out compression). B. Aortic angiogram shows no distortion after balloon deflation.

Patient 1 had a history of a complex surgical procedure that included creation of the RV-PA connection using a 12–13mm long segment of autogenous ascending aorta (15). Potential distortion of the aorta was suspected before coronary compression testing due to the position of the neo-pulmonary region immediately behind the sternum and directly in front of the ascending aorta from the Lecompte maneuver (Figure 2). In patient 3, severe aortic root distortion and AI was noted during routine coronary artery compression testing.

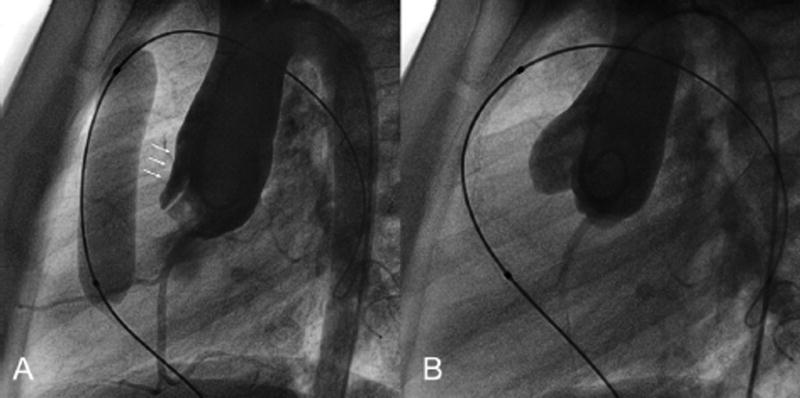

Aortic root distortion was deemed mild in the other 4 patients, who all had different underlying conditions and a variety of methods of RVOT reconstruction (Table 2). The RV-PA conduit was not directly retrosternal in any of the 4, and a Melody™ TPV was successfully implanted in 3 (patients 4,5,6). In patient 2, the procedure was aborted due to unsuitable RVOT anatomy secondary to protrusion of a stent previously implanted in the left pulmonary artery. No residual aortic root distortion was noted on post-implant angiography and/or echocardiography in patient 4 (Fig 5). No post-implant aortography was performed in patient 5 as distortion was not noticed at the time of the procedure,. However, post-procedural echocardiogram was unchanged. Post-implant angiography demonstrated mild residual root distortion in patient 6 (Fig 6), although no distortion was noted on the post-procedural echocardiogram.

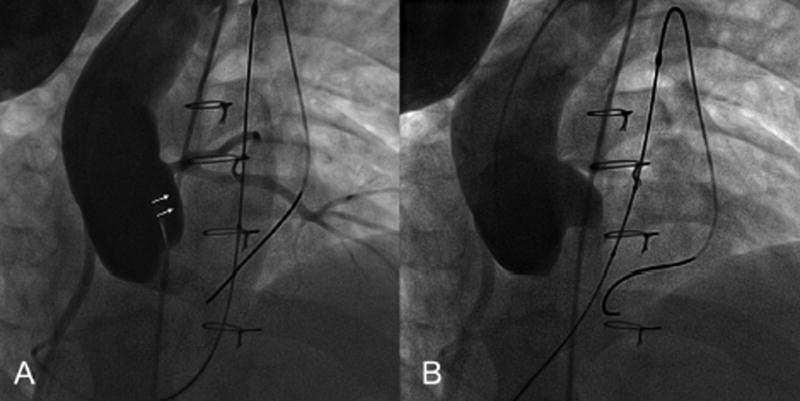

Figure 5.

Patient 4. A. Mild distortion of aortic cusp during simultaneous aortic angiography and RVOT balloon dilation. B. Post stent implantation aortic angiography shows no residual distortion. Note the similar area of indentation of the balloon and the stent.

Figure 6.

Patient 6. A. Baseline aortic angiogram. B. Mild distortion of the aortic cusp without AI during RVOT balloon dilation. C. Mild residual distortion and no AI after PV implantation. This patient had a residual aortic-pulmonary fistula (not shown).

There was no new/worsening residual AI in any of the 3 patients who received a TPV after observing mild aortic root distortion on compression testing. One other notable intervention-related adverse event occurred in patient 6, who had truncus arteriosus originally repaired with a direct RV-PA connection and developed a small aortopulmonary fistula after RVOT angioplasty, pre-stenting, and TPV replacement. Given the location of the fistula at the level of the pulmonary artery bifurcation and a possible increase in size on serial echocardiograms, the patient was not considered a good candidate for covered stent implantation or device closure and was referred for surgical closure of the fistula and RVOT reconstruction.

Twelve patients did not develop aortic root distortion on aortic angiography during balloon dilation (Table 2). However, 7 of them had new or worsening AI during the maneuver. The RV-PA connection consisted of a conduit in 9 and a prosthetic valve in 3. The RV-PA conduit was immediately retrosternal in 4 of these patients, including 2 with a history of arterial switch operation, 1 with an RV-PA conduit and Lecompte maneuver, and 1 who had undergone a Ross operation. Melody™ TPV was not implanted in 5 of these 12 patients due to risk of coronary compression in 3, conduit tear not suitable for covered stent in 1, and risk of dislodging a covered stent implanted during cardiac arrest with the Melody™ TPV delivery sheath in 1 patient who experienced a significant tear during progressive balloon conduit dilation (patient 17).

Among the subset of patients who underwent aortography during coronary compression testing, there were no statistical associations between aortic root distortion and/or AI and baseline anatomy, surgical procedure, type of RVOT repair, indication for TPV implantation, or relationship of the RVOT with the sternum.

Pre- and post- TPV implantation echocardiograms were available for review and adequate in 83 of the 91 implanted patients (91%). On pre-TPV implant echocardiogram, 46 of these 83 patients (55%) had no/trivial AI, 30 (36%) mild and 7 (9%) moderate AI. No leaflet distortion, aortic root compression, or new/worsened AI was detected on post-procedural echocardiogram in any patient, including the patient with mild residual distortion on angiography (patient 6). On long-term follow up, no patient in the entire cohort (R1) required further assessment or intervention related to new aortic root distortion or progressive AI.

DISCUSSION

TPV Replacement and Coronary Artery Compression Testing

TPV implantation has become a valuable therapeutic option for patients with RVOT dysfunction of previously placed RV-PA conduits or bioprosthetic pulmonary valves (1–6). Balloon inflation in the RVOT with simultaneous coronary angiography is a common maneuver for assessing the risk of coronary artery compression with TPV implantation. In recent multicenter series, coronary artery compression during RVOT test angioplasty was reported in around 5% of patients referred for TPV implantation (7–10). In our study, patients who underwent aortic angiography during coronary artery compression testing were younger than those who only had selective coronary artery angiography. The reasons for this finding are likely multifactorial. Stents and Melody™ TPV are usually implanted on relatively large balloons, which may have raised concern about likelihood of coronary artery compression in younger patients with smaller aortic/pulmonary artery roots and prompted operators to perform additional imaging in order to better define coronary artery anatomy and the relationship with surrounding structures. Coronary compression testing can be performed with selective coronary or ascending aortic angiography. Ascending aortic angiography during RVOT balloon inflation has proven useful when compression of the most proximal segment of a coronary artery is suspected. Selective coronary artery angiography in these patients may mask ostial compression, as the tip of the engaging catheter can effectively stent open the proximal segment of the coronary artery or be distal to the compressed region. Aortic angiography is also useful to determine the anatomic relationship between the RVOT and the aortic root/proximal ascending aorta, as changes in the RVOT geometry by TPV implantation can potentially compress or distort the aortic root. The distance between the RV-PA conduit and aorta alone can be misleading when trying to determine the risk of compression/distortion, insofar as scar tissue or residual material from prior surgeries may be located between the RV-PA conduit and the aorta, which can be displaced as a whole and compress structures that were considered remote based on angiography without RVOT balloon inflation.

Aortic Root Compression and Aortic Insufficiency

Reports of aortic root compression following TPV implantation are scarce. Aortic distortion following TPV implantation was observed in a patient with a history of Ross operation during the early IDE US Melody™ study, but the long-term outcome of this finding was not reported (16). More recently, Peer et al reported an 11 year-old patient with a prior Ross-Konno operation who required emergency surgery a few days after Melody™ TPV implantation due to significant distortion of the aortic root, including the ostium of the left main coronary artery, and progressive AI (11). Although coronary compression testing was performed prior to Melody™ TPV implantation in that patient, the simultaneous imaging utilized was selective coronary artery angiography rather than an aortogram. It is unknown if the patient developed aortic root distortion during balloon inflation, which could have warned the operators about the potential risk of residual distortion after TPV implantation.

In this study we report six patients in whom aortic root distortion and/or AI was noted on aortic angiography during simultaneous balloon dilation of the RVOT. Although it is not known how often balloon dilation of the RVOT results in aortic root distortion, some degree of root distortion and/or AI was noted in 6 of 18 (33%) patients, which suggests that it may be a relatively common phenomenon. Based on the lack of residual aortic root distortion and new or worsening AI on the post-implant echocardiograms of most patients and the fact that no patient in our study population required any type of intervention to address residual aortic root “dysfunction” following Melody™ TPV implantation, this is likely a benign finding in most cases. However, there is a subset of patients that may be at risk of developing significant residual aortic root distortion and/or AI with serious hemodynamic compromise following Melody™ TPV implantation, as demonstrated by the case reported by Peer et al (11). Since no Melody™ TPV was implanted in the 2 patients in this series with severe aortic root distortion, it is unknown whether advanced degrees of root distortion on compression testing will correspond with similar findings after TPV implant. Aortic angiography during RVOT balloon occlusion was performed in only 18 of 118 patients, therefore it is likely (although unknown) that some other patients would have developed significant aortic root distortion and/or AI during balloon sizing had this maneuver been performed. However, none of these patients had residual root distortion or worsening AI on post-implant echocardiography.

Anatomic and Physiologic Factors that May Predispose to Aortic Root Distortion

Compression of the aorta during RVOT balloon inflation is likely due to a combination of hemodynamic, anatomic, and technical factors. During this maneuver, aortic pressure usually drops considerably due to decreased left ventricular filling unless there is a significant right to left shunting at the atrial or ventricular level. Therefore, even a balloon inflated at low pressure may shift the RVOT and surrounding structures resulting in distortion of an artificially low-pressure aorta. However, other factors are likely involved, as hypotension during RVOT balloon inflation is common and distortion is not seen in most patients.

Post-surgical spatial alignments and proximity of the RV-PA connection with the ascending aorta are variable, often unusual, and may predispose to compression of the aortic root. Close proximity between RVOT, proximal pulmonary artery branches and the aorta is well recognized after the Ross operation, reconstructed ascending aorta or procedures that include the Lecompte maneuver. The resulting narrow aortopulmonary relationship has been associated with a higher risk for fracture of stents implanted in the main or proximal branch pulmonary arteries of these patients (16,17). In the present study, 3 of the 17 patients with a history of Ross operation underwent aortic angiography during RVOT balloon dilation, only 1 of whom developed mild distortion and received a Melody™ valve. Of the remaining 14 patients, a Melody™ TPV was implanted in 12 without complications

Three patients in our cohort had a history of surgical repair that included the Lecompte maneuver, and all of them underwent coronary artery compression testing. One patient developed severe aortic root distortion and AI (patient 1) and the other two had no distortion, but a valve was not implanted in one of them (patient 13) due to the risk of coronary compression. Pre-post implant MRI showed no change on the degree of AI on patient 12. Of note, echocardiography could not be performed in this patient due to poor acoustic windows.

Indications for Melody™ TPV implantation include dysfunctional RVOT conduits or prosthetic pulmonary valves. However, as worldwide experience has grown, off label implantation has been attempted in patients with native RVOT dysfunction, transannular patch repair, or direct RV-PA anastomosis. Balloon sizing of the RVOT in these patients to establish a “landing zone” area for Melody™ TPV implantation often requires the use of large diameter balloons due to the distensibility of many of these RV-PA connections. In small patients or those with a close aortic/RVOT spatial relationship, implantation of stents/TPV mounted on “large” diameter balloons in order to assure proper “anchoring” may result in significant overexpansion of the RVOT which may increase the risk of developing aortic root distortion (18). This may have been the case of patient 6, who had a history of direct RV-PA anastomosis with patch roofing of the RVOT resulting in part of the RVOT wall being in direct contact (shared) with the aortic wall. In addition to the mild residual root distortion, this patient developed an aortic-pulmonary fistula at the most distal aspect of the TPV. The development of aortic-pulmonary communications following transcatheter interventions in the area of previous suture lines/surgical procedures in patients with an intimate relationship between the aorta and conduit/RVOT has been reported (12)

Immediate retrosternal location of the RVOT could potentially increase the risk of aortic root distortion and/or AI as there is only room for posterior expansion of the conduit during balloon dilation/stent implantation. This is a relatively common finding following cardiac surgery, and was shown in a prior study to be a risk factor for Melody™ valve stent fracture (14). Although a retrosternal conduit was present in the 2 patients who developed severe aortic root distortion and AI during RVOT balloon dilation, it was also present in 4 of the 12 patients who did not. None of the 3 patients with a prosthetic PV developed aortic root distortion (patients 8–10–11). This finding is consistent with a very low incidence of coronary artery compression in patients with prosthetic PV compared to those with a RV-PA conduit (7)

The spatial relationship between the RVOT and ascending aorta may change overtime due to different reasons, including somatic growth, as well as progressive aortic root dilatation as it occurs in patients with Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) and following arterial switch and Ross operations (19–21). Thus, patients with a progressively dilated aorta may be at higher risk of developing aortic root distortion with TPV implantation as the ratio of the shared area between the aortic and pulmonary roots may be different from the time of surgery. Somatic growth may also significantly modify the anatomic relationship between the two ventricular outflow tracts particularly in patients in whom an “adult-size” conduit has been implanted at a very young age and who present with a stenotic conduit several years later (22).

Technical factors such as balloon length, balloon shoulder length, and wire position may play a role in the occurrence of aortic root distortion and/or AI during balloon angiography of RVOT in some patients, but this is difficult to prove. Use of short balloons with short shoulders in order to avoid extensive straightening-related distortion that may confound the interpretation of the angiographic findings is preferred in many circumstances. Unfortunately, large diameter balloons are usually long, therefore this can be difficult to achieve in patients with large diameter RVOT. It could be argued that distortion of the aorta may be exacerbated by inadvertently pulling the stiff wire to maintain balloon position during inflation. In order to test this, we have occasionally repeated the aortogram while gently pushing forward the wire and the balloon as a whole once it was noticed that the balloon was “wedged” in the RVOT. In our limited experience, no difference on the degree of aortic root distortion and/or AI has been noted in any patient.

Potential Implications of Aortic Root Distortion

We arbitrarily defined “mild” or “severe” distortion of the aortic root as the angiographic partial or total flattening of the aortic cusp sinus respectively. Some aortic valve movement and function remains present during the cardiac cycle in mild distortion whereas the leaflet becomes a non-functional collapsed structure in severe distortion. Grading the severity of the distortion may not be easy in some cases as there are multiple interacting factors, including operator subjectivity. The presence and significance of AI is also difficult to assess. In the presence of aortic root distortion, AI is likely due to the lack of proper valve leaflet coaptation and should be a warning sign as it may indicate significant deformation of the aortic root/valve. However, AI was also seen in patients without root distortion. Catheter induced AI is common in these patients as the pigtail is purposely placed at or just above the aortic valve in order to better visualize the coronary arteries. Inflation of a balloon in the RVOT briefly interrupts pulmonary outflow and left-heart inflow, resulting in a reduction in stroke volume and systemic arterial blood pressure. Thus, aortography simultaneous with RVOT balloon inflation does not reflect a normal physiologic state or aortic valve dynamics, and some degree of AI may be related to the high-pressure contrast injection in the presence of decreased left ventricular filling and systolic pressure. Presence of AI without aortic root distortion during coronary compression testing should be considered of no clinical significance.

We have intuitively considered high-risk patients those with a known close relationship between the aorta and the RVOT, such as patients who have undergone a Ross operation or Lecompte maneuver, who have a particularly dilated aortic root or close aorta-RVOT relationship, or when the conduit is positioned immediately behind the sternum. These anatomic features can generally be recognized on baseline angiography or pre-catheterization MRI or CT. Although these patients may carry a higher risk, others may have a similar risk given the wide variety of post-surgical aortic/RVOT alignments. Based on the available data and the low incidence of residual aortic root distortion and/or AI, a recommendation as to which patient should undergo further screening cannot be made at this point and should be decided on a case-by-case basis.

LIMITATIONs OF THE STUDY

There are several limitations to this study. This is a retrospective case series from a single congenital cardiovascular center and selection of subjects was based on operator judgment at the time of intervention. Given this potential selection bias, findings of the study may not be extrapolated to the untested population. In addition, the numbers of patients that underwent coronary artery compression testing or who developed aortic root distortion are small, limiting the statistical power and, therefore, our ability to reach conclusions. The mechanism of aortic root distortion and/or AI during coronary compression testing is multifactorial, hence, the importance of its presence when considering TPV implantation remains unclear.

CONCLUSION

In TPV replacement candidates, aortic root distortion and/or AI are relatively common on aortic angiography during coronary compression testing with simultaneous balloon angioplasty of the RVOT. The significance of severe aortic root distortion and/or AI during balloon dilation is not clear, but indicates a group of patients that may be at risk of developing residual root distortion and/or AI after TPV implantation. Mild root distortion or AI during balloon inflation was generally not associated with persistent compression or AI after TPV implant, and thus appears to be a benign finding without long-term implications. Although no risk factors for aortic root distortion were found in the small cohort, patients known to have a close RVOT/aortic root relationship or proximity, as is common following a Ross operation or Lecompte maneuver, may be at higher risk compared to other RVOT/aortic alignments. RVOT balloon angioplasty with simultaneous ascending aorta angiogram should be considered prior to implantation of a TPV in the RVOT position. Longer-term follow-up will be necessary to determine if procedural aortic root distortion and/or AI are associated with these or other root complications over time.

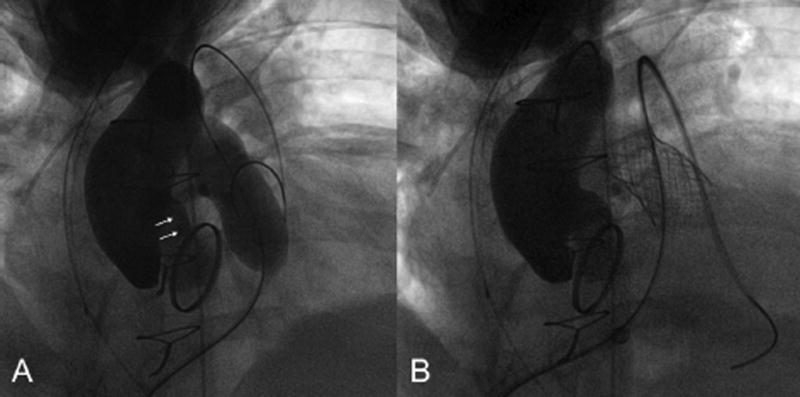

Figure 3.

Patient 1. A. Ascending aorta angiogram during balloon sizing of the RVOT shows distortion of the anterior sinus of Valsalva resulting in aortic valve insufficiency. B. Ascending aorta angiogram immediately after balloon deflation shows no sinus distortion or aortic valve insufficiency.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Anderson receives salary support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/National Institutes of Health (KL2 TR000081).

References

- 1.Zahn EM, Hellenbrand WE, Lock JE, McElhinney DB. Implantation of the Melody transcatheter pulmonary valve in patients with a dysfunctional right ventricular outflow tract conduit early results from the U.S. Clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1722–1729. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McElhinney DB, Hellenbrand WE, Zahn EM, Jones TK, Cheatham JP, Lock JE, Vincent JA. Short and medium-term outcomes after transcatheter pulmonary valve placement in the expanded multicenter US Melody valve trial. Circulation. 2010;122:507–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.921692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lurz P, Coats L, Khambadkone S, Nordmeyer J, Boudjemline Y, Schievano S, Muthurangu V, Lee TY, Parenzan G, Derrick G, Cullen S, Walker F, Tsang V, Deanfield J, Taylor AM, Bonhoeffer P. Percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation: Impact of evolving technology and learning curve on clinical outcome. Circulation. 2008;117:1964–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.735779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordmeyer J, Lurz P, Tsang VT, Coats L, Walker F, Taylor AM, Khambadkone S, de Leval MR, Bonhoeffer P. Effective transcatheter valve implantation after pulmonary homograft failure: A new perspective on the Ross operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:84–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.08.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khambadkone S, Coats L, Taylor A, Boudjemline Y, Derrick G, Tsang V, Cooper J, Muthurangu V, Hegde SR, Razavi RS, Pellerin D, Deanfield J, Bonhoeffer P. Percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation in humans results in 59 consecutive patients. Circulation. 2005;112:1189–1197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.523266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eicken A, Ewert P, Hager A, Peters B, Fratz S, Kuehne T, Busch R, Hess J, Berger F. Percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation: Two-centre experience with more than 100 patients. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1260–5. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morray BH, McElhinney DB, Cheatham JP, Zahn EM, Berman DP, Sullivan PM, Lock JE, Jones TK. Risk of coronary artery compression among patients referred for transcatheter pulmonary valve implantation: a multicenter experience. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013 Oct 1;6(5):535–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.113.000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mauri L, Frigiola A, Butera G. Emergency surgery for extrinsic coronary compression after percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation. Cardiol Young. 2013 Jun;23(3):463–5. doi: 10.1017/S1047951112001187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kostolny M, Tsang V, Nordmeyer J, Van Doorn C, Frigiola A, Khambadkone S, de Leval MR, Bonhoeffer P. Rescue surgery following percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:607–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biermann D, Schönebeck J, Rebel M, Weil J, Dodge-Khatami A. Left coronary artery occlusion after percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:e7–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peer SM, Sinha P. Percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation after Ross-Konno aortoventriculoplasty: a cautionary word. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014 Jun;147(6):e74–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres A, Sanders SP, Vincent JA, El-Said HG, Leahy RA, Padera RF, McElhinney DB. Iatrogenic aortopulmonary communications after transcatheter interventions on the right ventricular outflow tract or pulmonary artery: Pathophysiologic, diagnostic, and management considerations. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Feb 11; doi: 10.1002/ccd.25897. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbero-Marcial M, Riso A, Atik E, Jatene A. A technique for correction of truncus arteriosus types I and II without extracardiac conduits. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990 Feb;99(2):364–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen JM, Glickstein JS, Davies RR, Mercando ML, Hellenbrand WE, Mosca RS, Quaegebeur JM. The effect of repair technique on postoperative right-sided obstruction in patients with truncus arteriosus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005 Mar;129(3):559–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lecompte Y. Réparation à l'Etage Ventriculaire - The REV procedure: Technique and clinical results. Cardiol Young. 1991 Jan;1(1):63–70. doi: 10.1017/S104795110000010X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McElhinney DB, Cheatham JP, Jones TK, Lock JE, Vincent JA, Zahn EM, Hellenbrand WE. Stent fracture, valve dysfunction, and right ventricular outflow tract reintervention after transcatheter pulmonary valve implantation: patient-related and procedural risk factors in the US Melody Valve Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011 Dec 1;4(6):602–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.965616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McElhinney DB, Marshall AC, Schievano S. Fracture of cardiovascular stents in patients with congenital heart disease: theoretical and empirical considerations. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013 Oct 1;6(5):575–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.113.000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boshoff DE, Cools BL, Heying R, Troost E, Kefer J, Budts W, Gewillig M. Off-label use of percutaneous pulmonary valved stents in the right ventricular outflow tract: time to rewrite the label? Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013 May;81(6):987–95. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.David TE, Omran A, Ivanov J, Armstrong S, de Sa MP, Sonnenberg B, Webb B. Dilation of the pulmonary autograft after the Ross procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:210–20. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(00)70175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marino BS, Wernovsky G, McElhinney DB, Jawad A, Kreb DL, Mantel SF, van der Woerd WL, Robbers-Visser D, Novello R, Gaynor JW, Spray TL, Cohen MS. Neo-aortic valvar function after the arterial switch. Cardiol Young. 2006;16:481–9. doi: 10.1017/S1047951106000953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chong WY, Wong WH, Chiu CS, Cheung YF. Aortic root dilation and aortic elastic properties in children after repair of tetralogy of Fallot. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:905–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.09.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacques F, Kotani Y, Deva DP, Moller T, Oechslin E, Horlick E, Osten M, Crean A, Benson LN, Wintersperger BJ, Caldarone CA. Left main coronary artery compression long term after repair of conotruncal lesions: the bow string conduit. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012 Jul;94(1):283–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]