Abstract

Autophagy is an intracellular, catabolic process that maintains cellular health. We examined the response of pharmacologic modulation of autophagy in an HPV mouse model of anal carcinogenesis. K14E6/E7 mice were treated with the topical carcinogen DMBA weekly and assessed for tumors over 20 weeks. Concurrently, they were given either chloroquine or BEZ235, to inhibit or induce autophagy, respectively. Time to tumor onset was examined. Immunofluorescence (IF) was performed for LC3β and p62 to examine autophagy. All DMBA treated K14E6/E7 mice developed anal cancer, contrary to zero of the no DMBA treated mice. Chloroquine plus DMBA resulted in a significant decrease in the time to tumor onset compared to K14E6/E7 treated with DMBA. Only 40% BEZ235 plus DMBA treated mice developed anal cancer. Autophagic induction with DMBA and BEZ235, and autophagic inhibition with chloroquine were confirmed via IF. Anal carcinogenesis can be inhibited or induced via pharmacologic modulation of autophagy.

Keywords: Anal cancer, HPV, Autophagy, Anal dysplasia, Chemoprevention, BEZ235

1. Introduction

There are a limited number of durable and effective prevention strategies for anal cancer. Because more than 95% of anal cancer cases are associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, strong advocacy for HPV vaccination is an appropriate response to prevent long-term consequences such as anal cancer development (Moscicki et al., 2012). However, due to poor vaccination rates (21–37%), even if every patient today were to receive the complete HPV vaccination series (Surviladze et al., 2013), significant decreases in the incidence of anal cancer from vaccination alone will not be observed for over two decades. As a result of poor vaccination and the efficacy of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART), anal cancer incidence and mortality continue to increase despite HPV vaccination. Thus, there is a need to explore other prevention options (SEER Cancer Database, 2016).

Autophagy is an evolutionarily well-conserved, intracellular, catabolic process where damaged or dysfunctional proteins, nucleic acids, and organelles are selectively isolated in a double membrane vesicle called an autophagosome. Autophagic protein LC3β is normally found diffusely throughout the cytoplasm on immunofluorescence. During autophagic induction, LC3β becomes granular or punctate in appearance, due to its incorporation into the membrane of the autophagosome at the time of autophagosome formation. The autophagosome then fuses with the lysosome to form an autophagolysosome, allowing for the degradation of the autophagosome and its contents (Glick et al., 2010). The byproducts of autophagic degradation can then be used for the production of new proteins and energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). The cargo protein p62 targets proteins and organelles for autophagic degradation, and is itself degraded solely via the autophagic pathway. Therefore, when visualized microscopically, the proteins LC3β and p62 can be utilized to examine autophagic induction (punctate LC3β) and autophagic function (p62 degradation) (Barth et al., 2010).

The pathogenesis of HPV-associated anal carcinogenesis is an area of active investigation (Thomas et al., 2011). It has been demonstrated in other HPV-associated cancers, including cervical cancer, that high-risk serotypes of HPV (HPV-16 and 18) inhibit the host autophagic pathway (Li et al., 2015). The inhibition of autophagy by HPV is an adaptive response to prevent viral clearance. To further confirm the role of high-risk HPV infection on autophagy, it has been demonstrated that HPV-16 early gene depletion in cervical cells results in the induction of autophagy, thus supporting the argument that HPV-associated gene expression inhibits autophagy (Hanning et al., 2013). Finally, it has also been demonstrated that HPV-16 activates the mTOR pathway, resulting in autophagic inhibition (Spangle and Munger, 2010). Our group recently demonstrated that there is evidence of autophagic dysfunction early in HPV anal carcinogensis (Carchman et al., 2016).

Emerging data on autophagy in cancer provide evidence for a dual role of autophagy in anal cancer development and growth. On the one hand, autophagy enables tumor cells to tolerate and survive the stress of the tumor microenvironment (hypoxia, high energy requirements, etc.) and toxic therapies (chemotherapy). On the other hand, autophagy is important for minimizing genomic damage that can promote tumorigenesis (White and DiPaola, 2009). In this study, we examined the role of pharmacologic modulation of autophagy and its effect on anal cancer development. We utilized the drug BEZ235, a dual inhibitor of PI3K and mTOR, that produces autophagic induction (Mukherjee et al., 2012). To inhibit autophagy, we utilized chloroquine, which prevents the fusion of the autophagosome with the lysosome (Kimura et al., 2013). Given the role of HPV infection on autophagy in cervical tissue (Wang et al., 2014), we hypothesized that pharmacologic induction or inhibition of the autophagy pathway will have a similar effect, and prevent/delay or accelerate, respectively, anal carcinogenesis in our HPV mouse model of anal carcinogenesis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

K14E6/E7 mice were generated as previously described (Stelzer et al., 2010). These mice express the HPV-16 oncoproteins E6 and E7 in their epithelium (K14 epithelial promoter). When treated with 7,12 dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA), these mice develop progressive anal dysplasia to invasive squamous cell carcinomas, similar to that seen in humans. Mice without HPV-associated oncoproteins (FVB/N background) treated with DMBA do not develop anal cancer over a 20-week time period, demonstrating the importance of these oncoproteins in anal carcinogenesis (Stelzer et al., 2010). All mice were maintained in an American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-approved Wisconsin Institute for Medical Research (WIMR) Animal Care Facility. The experiments were performed in accordance with approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol M02635.

2.2. 7,12 dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA) induced anal carcinogenesis

Weekly topical application of 0.12μmole of DMBA (60% acetone/40% dimethylsulfoxide, DMSO) to the anus of K14E6/E7 mice was performed as previously published (Stelzer et al., 2010). Mice were monitored weekly for tumor appearance and growth. Animals were sacrificed at 20 weeks post initiation of DMBA treatment. Control mice were age-matched K14E6/E7 mice not treated with DMBA.

2.3. Pharmacologic modulation of autophagy

BEZ235 (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA) was given to 50 K14E6/E7 mice (1 mg a day of 10 mg/mL BEZ235 in 0.0005% antifoam, 0.0025% Tween 80, 1.0% hydroxyethylcellulose) via oral gavage, five days per week (Monday–Friday) for 20 weeks. Chloroquine phosphate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was diluted in phosphate buffered solution (1X PBS) and filtered prior to administration to 50 K14E6/E7 mice. Each mouse was given 3.5 mg/kg via intraperitoneal injection (IP) five days per week (Monday–Friday) for 20 weeks. Fifty mice were treated with each drug (50 mice with chloroquine and 50 mice with BEZ235), with 25 mice from each group also being treated with DMBA while the remaining 25 mice were not treated with DMBA. Pharmacologic controls were K14E6/E7 mice that received neither chloroquine nor BEZ235, with and without DMBA treatments.

2.4. Histological analysis

Anal tissue was collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, and then placed in 70% ethanol. After fixation, the tissues were processed, embedded in paraffin, and serially sectioned at 5 μm thickness. Every seventh section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) and evaluated by a gastrointestinal fellowship trained, board-certified surgical pathologist for evidence of dysplasia (low-grade versus high-grade), high-grade dysplasia with superficial invasion, or invasive carcinoma. Histologic grade at time of death or 20 weeks was scored in the following manner: 0 for normal, 1 for low-grade dysplasia, 2 for high-grade dysplasia, 3 for invasive carcinoma (all grades). None of the mice in this study had high-grade dysplasia with superficial invasion.

2.5. Immunofluorescence for autophagic proteins

Paraffin sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, subjected to antigen retrieval with 10 mM sodium citrate buffer pH 6.0 and heat, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, and blocked with 5% milk/5% donkey serum in phosphate buffered saline (1× PBS) per standard protocols (Barth et al., 2010). To examine autophagy, the sections were stained with monoclonal rabbit antibody against LC3β (1:50 in 5% milk/5% donkey serum in PBS; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) or monoclonal mouse antibody for p62 (1:200 in 5% milk/5% donkey serum in PBS; Abcam, Cambrige, UK) overnight at 4 °C. Sections were then washed and stained with donkey anti-rabbit Fluor 488 (for LC3β) and donkey anti-mouse Fluor 594 (for p62) (1:500 in 5% milk/5% donkey serum in PBS; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for one hour in the dark at room temperature. Slides were then counter stained with the nuclear stain DAPI. Slides were imaged using the Ziess Axio Imager M2 imaging system. Images at 100×, 200×, 400× and 630× magnification were obtained for each sample. Each 200× image was imported into Image J version 2.0.0 (Fiji distribution) and underwent the follow processing. Images were split in the three channels (488, 594 and DAPI). All images were thresholded using the default dark background. The areas of interest were manually selected and then RawIntDen measured for the region of interest to measure the intensity of the fluorescent signal. The RawIntDent was then normalized for the area of the region selected (RawIntDen/Area).

2.6. Statistical analysis

In order to detect at least a two-fold difference, alpha < 0.05, and beta error of 80% between the treated and untreated groups, 25 mice per group, were studied. Fisher’s two-sided exact t-test was used to determine differences between treatment groups in tumor incidence at 20 weeks. A Kaplan Meier analysis was used to determine differences between time to tumor onset. The comparisons between treatment groups of average histologic grade and expression of LC3β and p62 were made using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc testing. SPSS version 23 (IBM, Armonk, North Castle, NY) was utilized to perform each of these analyses. Statistical significance was defined as P≤0.05.

3. Results

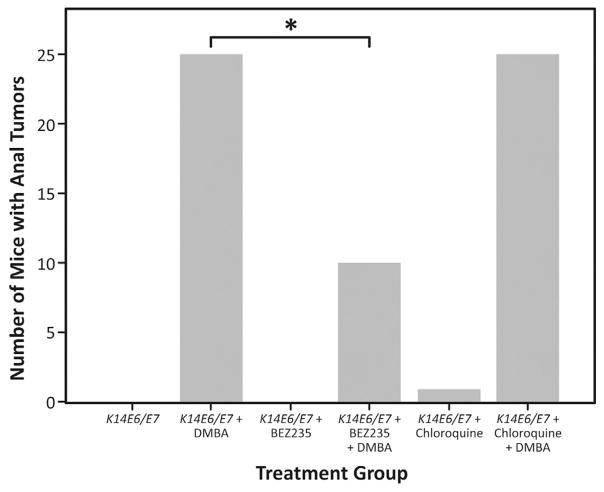

3.1. Tumor free survival and tumor onset

Two of the K14E6/E7 mice that received DMBA treatment alone showed signs of anal tumor development, starting at 15 weeks. All (100%) of DMBA-only K14E6/E7 mice (25 mice) had anal tumors by the end of the 20-week period. The 25 K14E6/E7 mice not receiving DMBA did not show any signs of anal tumorigenesis over the course of 20 weeks. When treated with BEZ235 and DMBA concurrently, 10 K14E6/E7 mice showed signs of anal tumor development over the 20-week DMBA time course. Fifteen (60%) of the mice did not develop any anal tumor by the end of the 20-week DMBA treatment period (Fig. 1, P=0.001). K14E6/E7 mice treated with both chloroquine and DMBA began developing tumors as early as 4 weeks. By 18 weeks, 100% of mice had anal tumors. It is worth noting that 60% of the mice receiving chloroquine and DMBA had died by 16 weeks of treatment due to tumor burden, whereas 100% of the mice being treated with DMBA and BEZ235 were still alive at this point. Please refer to Fig. 1 to review differences in tumor development between treatment groups.

Fig. 1. Tumor incidence in treatment groups.

100% of DMBA-only K14E6/E7 mice (25 mice) had anal tumors by the end of the 20-week period, while none of the no DMBA treated mice developed anal tumors. When treated with NVP-BEZ235 and DMBA concurrently, only 10 of the 25 K14E6/E7 mice showed signs of anal tumor development over the 20-week DMBA time course. Fifteen (60%) of the mice did not experience any anal tumor growth by the end of the 20-week DMBA treatment period (*P=0.001). There was no difference in the mice treated with chloroquine compared to the K14E6/E7 mice with and without DMBA.

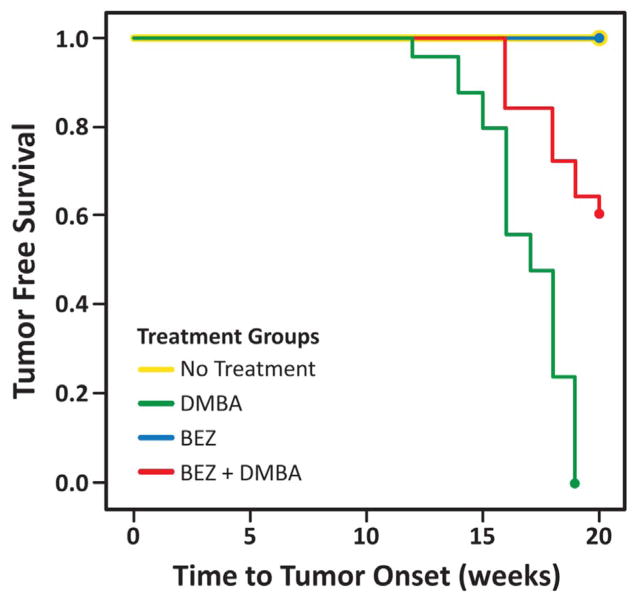

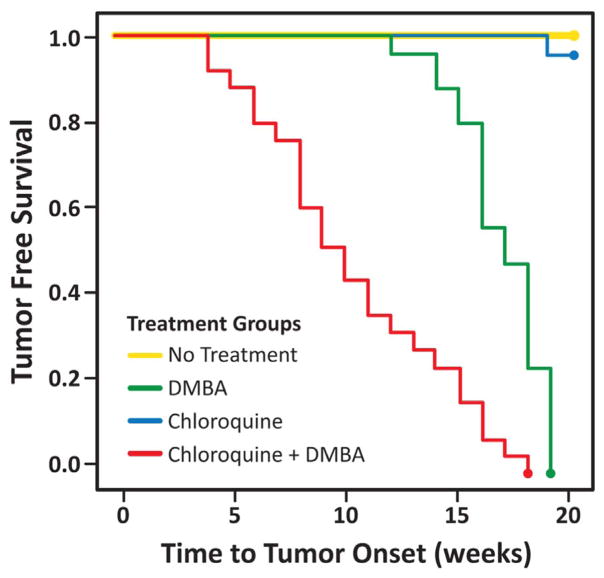

Tumor free survival (Fig. 2) was statistically significantly different between the K14E6/E7 mice that received DMBA alone (P < 0.0005) compared to mice that received DMBA and BEZ235. In contrast, all mice receiving chloroquine and DMBA developed anal tumors much sooner compared to the mice not receiving chloroquine (Fig. 3, P < 1e−7).

Fig. 2. Tumor free survival of mice treated with an autophagic inducer (BEZ235).

On average, K14E6/E7 mice receiving BEZ235 in the setting of DMBA (red had longer tumor free survival than those receiving DMBA alone (green, P < 0.0005). None of the mice in BEZ alone (blue) and no treatment control (yellow) groups developed tumors by 20 weeks. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 3. Tumor free survival of mice treated with an autophagic inhibitor (chloroquine).

On average, K14E6/E7 mice receiving chloroquine in the setting of DMBA (red had significantly shorter tumor free survival than those receiving DMBA alone (green, P < 1e−7). One of the mice in chloroquine alone group (blue) and none of the no treatment control (yellow) group mice developed tumors by 20 weeks. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

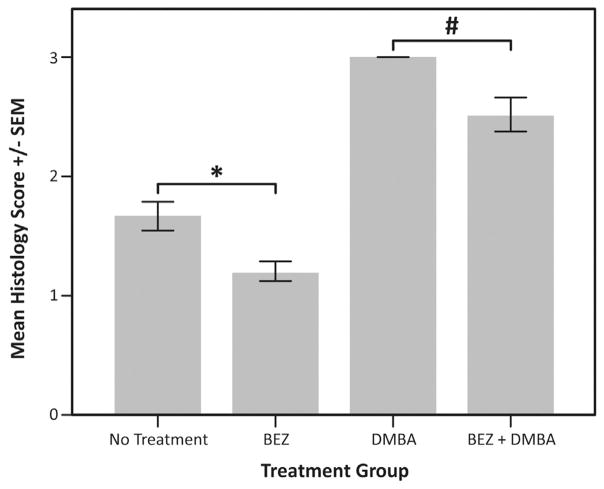

3.2. Histological analysis

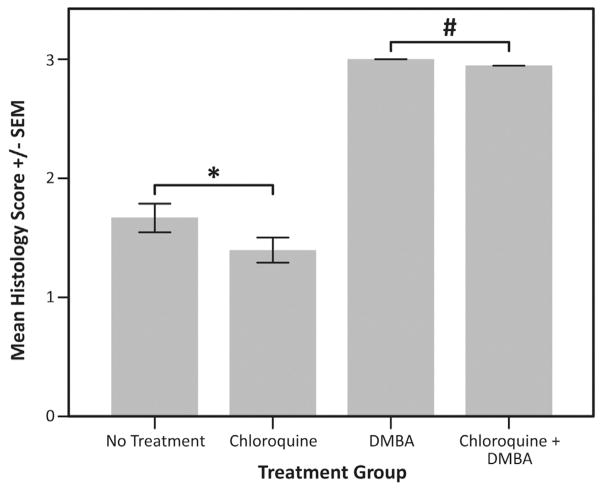

The average histological classification for each treatment group is presented in Figs. 4 and 5. There was a statistically significant difference in histological classification between the K14E6/E7 mice that received DMBA with or without NVP-BEZ235 (Fig. 4, P=0.005). Additonally, there was a statistical difference between those mice receiving BEZ235 versus the untreated controls (Fig. 4, P=0.008), suggesting that autophagic stimulation has as impact on the development of anal dysplasia in this model. There was no statistical difference between K14E6/E7 mice with DMBA, with and without chloroquine, due to the fact that all of these mice developed anal tumors (Fig. 5, P=1.0). As expected with the inhibition of autophagy, no difference was seen between untreated controls and those receiving chloroquine alone (Fig. 5, P=0.07). Representative H & E images for each treatment group are depicted in Fig. 6.

Fig. 4. Average histologic score in mice treated with an autophagic inducer (BEZ235).

At the time of death or 20 weeks, H & E stained tissue from each mouse was graded histologically. The following scoring method was applied: normal histology =0, low-grade dysplasia =1, high-grade dysplasia =2, squamous cell carcinoma (any grade) =3. The average score for mice in each treatment group was then compared using a one-way ANOVA. Those mice receiving DMBA with BEZ235 (average score ± SD, 2.5 ± 0.7) or without BEZ235 (3 ± 0) were significantly different (#P=0.005). Additionally, untreated mice (1.7 ± 0.6) and those receiving BEZ235 (1.2 ± 0.4) alone were significantly different (*P=0.008).

Fig. 5. Average histologic score in mice treated with an autophagic inhibitor (chloroquine).

At the time of death or 20 weeks, H & E stained tissue from each mouse was graded histologically. The following scoring method was applied: normal histology =0, low-grade dysplasia =1, high-grade dysplasia =2, squamous cell carcinoma (any grade) =3. The average score for mice in each treatment group was then compared using a one-way ANOVA. Those mice receiving DMBA with chloroquine (average score ± SD, 3 ± 0) or without chloroquine (3 ± 0) were not significantly different (#P=1.0). Additionally, untreated mice (1.7 ± 0.6) and those receiving chloroquine (1.4 ± 0.5) alone were not significantly different (*P=0.07).

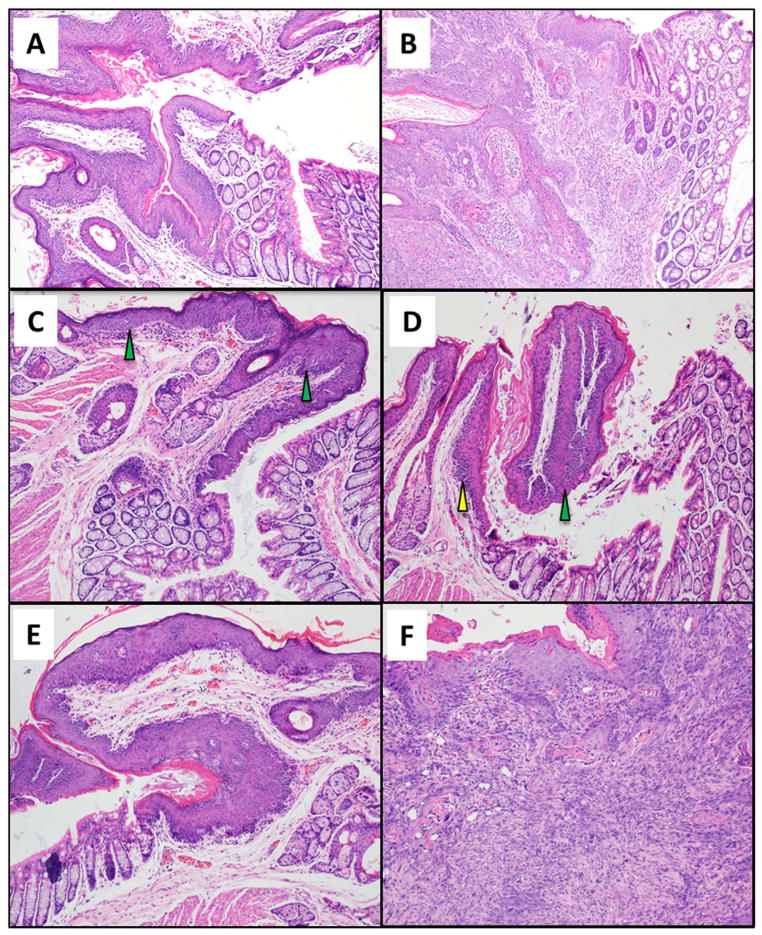

Fig. 6. Histological analysis of the anal transition zone for various treatment groups.

Anal histology based on the findings identified by a trained pathologist. Anal tissue was examined at 20 weeks for each of the treatment groups. Magnification of each image is 200x. (A) K14E6/E7- low-grade dysplasia; (B) K14E6/E7 with DMBA - Grade 1 squamous cell carcinoma; (C) K14E6/E7 with BEZ235 - low-grade dysplasia with focal high-grade dysplasia; (D) K14E6/E7 with BEZ235 and DMBA - high-grade dysplasia; (E) K14E6/E7 with chloroquine - high-grade dysplasia; and (F) K14E6/E7 with chloroquine and DMBA - grade 3 squamous cell carcinoma.

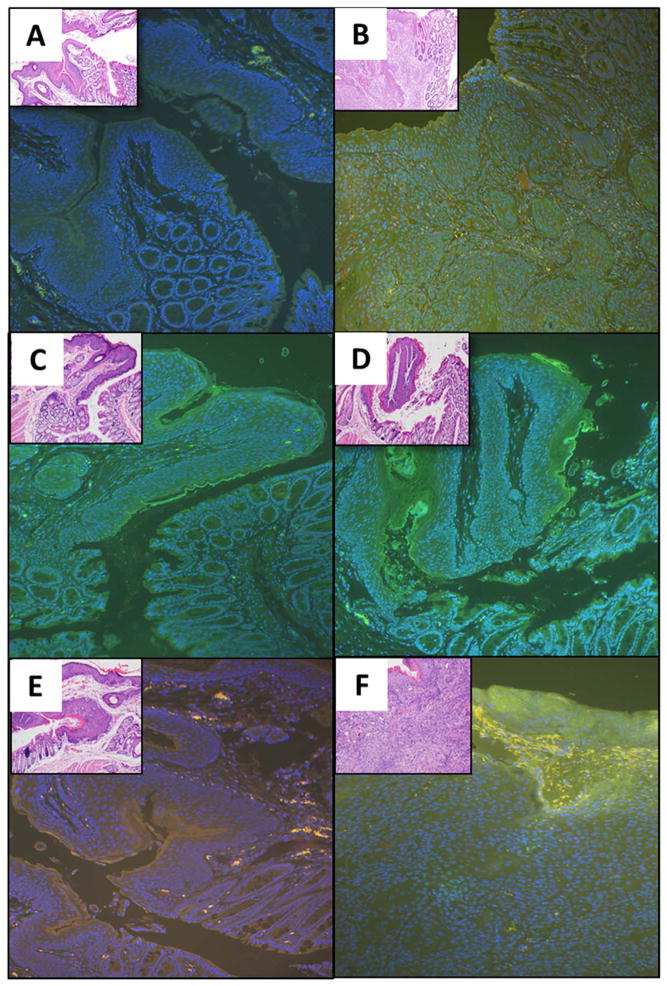

3.3. Immunofluorescence

Representative immunofluorescent images taken from the anal transition zone for each of the treatment groups (same samples as were used for the histological analysis above) are shown in Fig. 7. Panel (A) demonstrates the anal tissue of a control mouse (K14E6/E7) that received neither DMBA nor either of the pharmacologic treatments to modulate autophagy. Panel (B) is a K14E6/E7 mouse treated with DMBA for 20 weeks. There was evidence of autophagic induction with a significant increase in punctate LC3β expression (green). Panel (C) is a K14E6/E7 mouse treated with BEZ235 alone for 20 weeks. There is evidence of autophagic induction with an increase in LC3β (green) expression compared to the control mice (panel A). Panel (D) demonstrates the anus of a K14E6/E7 mouse treated with both DMBA and BEZ235 for 20 weeks. There is no evidence of tumor and there is continued increase in autophagy as measured by LC3β expression (green). Panel (E) is a K14E6/E7 mouse treated with chloroquine alone for 20 weeks. There is evidence of autophagic inhibition as seen by an accumulation and co-localization of LC3β (green) and p62 (red), resulting in orange coloration. Panel (F) is a mouse treated with both chloroquine and DMBA for 20 weeks. This mouse had gross tumor development. On immunofluorescence there is significant autophagic flux as measured by increased LC3β and no accumulation of p62.

Fig. 7. Immunofluorescence for autophagic proteins following pharmacologic modulation of autophagy (magnification 200x).

Immunofluorescence was performed for autophagic protein LC3β (green) and autophagy-specific substrate p62 (red). DAPI (blue) was utilized as a nuclear counterstain. Anal tissue was examined at 20 weeks for each of the treatment groups: (A) K14E6/E7 (low-grade dysplasia); (B) K14E6/E7 with DMBA (Grade 1 squamous cell carcinoma); (C) K14E6/E7 with BEZ235 (high-grade dysplasia); (D) K14E6/E7 with BEZ235 and DMBA (low-grade dysplasia with focal high-grade dysplasia); (E) K14E6/E7 with chloroquine (high-grade dysplasia); and (F) K14E6/E7 with chloroquine and DMBA (Grade 3 squamous cell carcinoma). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

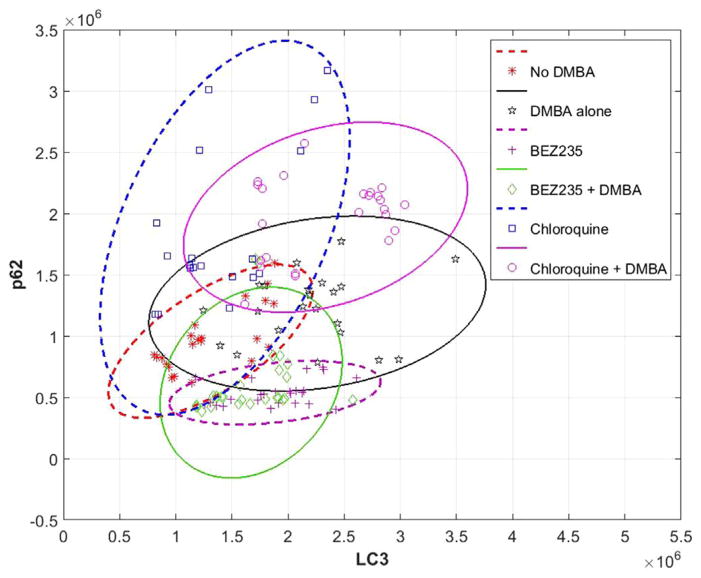

Dual immunoflourescent staining and high magnification imaging (20×) was performed to identify autophagic induction with the formation of punctate LC3β and autophagic function with p62 levels. All mouse samples were analyzed by FIJI software and each mouse is plotted in Fig. 8 with LC3β immunoflourescent intensity on the x-axis and p62 immunoflourescent intensity on the y-axis. One-way ANOVA analysis demonstrated a significant increase in LC3β in K14E6/E7 mice treated with DMBA versus no DMBA treated mice (P < 0.001). There was also significant increase in LC3β in mice treated with BEZ235 alone compared to no DMBA treated mice (P < 0.001). These increases in LC3β intensity represent induction of autophagy. There was no change LC3β intensity in mice treated with chloroquine alone compared to DMBA treated mice (P=0.92).

Fig. 8. LC3β and p62 immunofluorescence levels in K14E6/E7 mice for various treatment groups as determined by FIJI analysis.

Dual immunoflourescent (LC3β and p62) staining and high magnification imaging (20x) was performed. LC3β immunoflourescent intensity, indicating autophagic induction, is displayed on the x-axis and p62 immunoflourescent intensity, indicating autophagic function, on the y-axis. Ellipses represent the 95% confidence interval for each treatment group in the corresponding color. Solid lines indicate those groups that also received DMBA. One-way ANOVA analysis demonstrated a significant increase in LC3β in K14E6/E7 mice treated with DMBA versus no DMBA treated mice (P < 0.001). There was also a significant increase in LC3β in mice treated with BEZ235 alone compared to no DMBA treated mice (P < 0.001). In those mice treated with chloroquine, there was no change in LC3β in mice treated with chloroquine alone compared to no DMBA treated mice (P=0.92). In terms of p62 levels there was a statistically significant decrease in mice treated with BEZ235 with and without DMBA, compared to DMBA and no DMBA alone treated mice, and mice treated with DMBA and no DMBA with chloroquine (P=0.011 for BEZ235 with DMBA versus no DMBA; P < 0.001 for all other comparisons). There was also a statistically significant increase in p62 in chloroquine treated mice (with and without DMBA) compared to K14E6/E7 mice without DMBA, and with and without BEZ235 (P < 0.001 for all comparisons).

In terms of p62 levels, there was a statistically significant decrease in mice treated with BEZ235 with and without DMBA compared to DMBA and no DMBA alone treated mice, and mice treated with DMBA and no DMBA mice with chloroquine (P=0.011 for BEZ235 with DMBA versus no DMBA; P < 0.001 for all other comparisons). These decreases in p62 levels provide evidence for increased autophagic function in BEZ235 treated mice, compared to mice with and without chloroquine. There was also a statistically significant increase in p62 in chloroquine treated mice (with and without DMBA) compared to K14E6/E7 mice without DMBA and with and without BEZ235 (P < 0.001 for all comparisons). This increase in p62 levels indicates evidence of decreased autophagic degradative function in the setting of chloroquine treatment.

4. Discussion

Autophagy is an essential intracellular catabolic process that maintains cellular health, especially in times of stress such as infection. HPV produces oncoproteins that inhibit autophagy, thus providing a mechanism for viral infection, persistence, and replication (Griffin et al., 2013; Surviladze et al., 2013). Through separate pathways, both oncoproteins E6 and E7 have been demonstrated to inhibit autophagy (Hanning et al., 2013; Spangle and Munger, 2010), causing an accumulation of dysfunctional proteins and organelles that can result in genomic and cellular damage, and creating an environment that promotes cancer development.

This study utilizes modulation of autophagy, via pharmacologic means, to examine impact on tumorigenesis. Via immunofluorescence, we demonstrated appropriate autophagic induction or inhibition by BEZ235 or chloroquine, respectively. The data presented here provide corroborative evidence that autophagic inhibition is important in anal cancer carcinogenesis, and that with pharmacologic induction or inhibition of autophagy one can delay or promote anal carcinogenesis, respectively. This may provide an additional strategy for anal cancer prevention, along with vaccination.

This study provides the first strong evidence to date that autophagic modulation can promote or inhibit anal cancer. Previous work regarding HPV-associated carcinogenesis and the role of autophagy in carcinogenesis has been focused on cervical and endometrial carcinomas. Our group recently published a study using the same mouse model, showing that dysregulation of autophagy occurs early in the carcinogenic process (Carchman et al., 2016).

Our preliminary evidence shows that autophagic induction results in the delay of anal carcinogenesis. In addition to HPV vaccination, this may serve as another effective strategy for anal cancer prevention, especially in our high-risk patients (transplant, HIV, and immunocompromised patients, etc.) (Chin-Hong, 2016; Wang et al., 2017). Additional studies are required, utilizing more targeted drugs and/or genetic modulation of key autophagic proteins, in order to further elucidate the role of autophagy in anal carcinogenesis, and the role of autophagic modulation on anal cancer development.

Acknowledgments

Grant support

This work is supported by The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (grant number- PRJ96MZ), The Central Surgical Association (grant number - AAA1353), and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32CA090217.

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Paul Lambert for his generous support and for providing the mice utilized in these experiments. We would also like to acknowledge the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center (UWCCC) Experimental Pathology Laboratory for paraffin-embedding and serial section of pathological specimens. This work is supported by The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (grant number- PRJ96MZ), The Central Surgical Association (grant number-AAA1353), and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32CA090217. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health..

Footnotes

Disclaimers or disclosures

No.

References

- Barth S, Glick D, Macleod KF. Autophagy: assays and artifacts. J Pathol. 2010;221:117–124. doi: 10.1002/path.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carchman EH, Matkowskyj KA, Meske L, Lambert PF. Dysregulation of autophagy contributes to anal carcinogenesis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin-Hong PV. Human Papillomavirus in kidney transplant recipients. Semin Nephrol. 2016;36:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol. 2010;221:3–12. doi: 10.1002/path.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin LM, Cicchini L, Pyeon D. Human papillomavirus infection is inhibited by host autophagy in primary human keratinocytes. Virology. 2013;437:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanning JE, Saini HK, Murray MJ, Caffarel MM, van Dongen S, Ward D, Barker EM, Scarpini CG, Groves IJ, Stanley MA, Enright AJ, Pett MR, Coleman N. Depletion of HPV16 early genes induces autophagy and senescence in a cervical carcinogenesis model, regardless of viral physical state. J Pathol. 2013;231:354–366. doi: 10.1002/path.4244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Takabatake Y, Takahashi A, Isaka Y. Chloroquine in cancer therapy: a double-edged sword of autophagy. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Gong Z, Zhang L, Zhao C, Zhao X, Gu X, Chen H. Autophagy knocked down by high-risk HPV infection and uterine cervical carcinogenesis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:10304–10314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscicki AB, Wheeler CM, Romanowski B, Hedrick J, Gall S, Ferris D, Poncelet S, Zahaf T, Moris P, Geeraerts B, Descamps D, Schuind A. Immune responses elicited by a fourth dose of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in previously vaccinated adult women. Vaccine. 2012;31:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee B, Tomimatsu N, Amancherla K, Camacho CV, Pichamoorthy N, Burma S. The dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 is a potent inhibitor of ATM- and DNA-PKCs-mediated DNA damage responses. Neoplasia. 2012;14:34–43. doi: 10.1593/neo.111512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEER Cancer Statistics Factsheets: Anal cancer. Bethesda, MD: SEER Cancer Database, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Spangle JM, Munger K. The human papillomavirus type 16 E6 oncoprotein activates mTORC1 signaling and increases protein synthesis. J Virol. 2010;84:9398–9407. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00974-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelzer MK, Pitot HC, Liem A, Schweizer J, Mahoney C, Lambert PF. A mouse model for human anal cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2010;3:1534–1541. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surviladze Z, Sterk RT, DeHaro SA, Ozbun MA. Cellular entry of human papillomavirus type 16 involves activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mTOR pathway and inhibition of autophagy. J Virol. 2013;87:2508–2517. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02319-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MK, Pitot HC, Liem A, Lambert PF. Dominant role of HPV16 E7 in anal carcinogenesis. Virology. 2011;421:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CJ, Sparano J, Palefsky JM. Human Immunodeficiency Virus/AIDS, Human Papillomavirus, and Anal Cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2017;26:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Yang GF, Huang YH, Huang QW, Gao J, Zhao XD, Huang LM, Chen HL. Reduced expression of autophagy markers correlates with high-risk human papillomavirus infection in human cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:1492–1498. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E, DiPaola RS. The double-edged sword of autophagy modulation in cancer. Clin Cancer Res: Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2009;15:5308–5316. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]