Abstract

Background

Single unit recording in behaving nonhuman primates is widely used to study the primate central nervous system. However, certain questions cannot be addressed without recording large numbers of neurons simultaneously. Multiple 96-electrode probes can be implanted at one time, but certain problems must be overcome to make this approach practical.

New Method

We describe a series of innovations and practical guidance for implanting and recording from 8 arrays of 96 electrodes (768 electrodes) in the frontal cortex of Macaca mulatta. The methods include an individualized 3D-printed connector mounting platform, sequencing of assembly and surgical steps to minimize surgery time, and interventions to protect electrical connections of the implant.

Results

The methodology is robust and was successful in our hands on the first attempt. On average, we were able to isolate hundreds (535.7 and 806.9 in two animals) of high quality units in each session during one month of recording.

Comparison with Existing Methods

To the best of our knowledge, this technique at least doubles the number of Blackrock arrays that have been successfully implanted in single animals. Although each technological component was pre-existing at the time we developed these methods, their amalgamation to solve the problem of high channel count recording is novel.

Conclusions

The implantation of large numbers of electrodes opens new research possibilities. Refinements could lead to even greater capacity.

Keywords: large-scale recording, high-density recording

1. Introduction

Ever since the pioneering work of Edward Evarts (Evarts, 1966), single unit neuronal recording from awake, behaving monkeys has provided fertile ground for associating brain regions with function. Based on methods worked out in the 1950s (Humphrey and Schmidt, 1990), single unit recordings have provided neuron-level markers of brain operation during sensory, motor and cognitive tasks throughout the ensuing 60 years. A perennial limitation has been collecting a sufficient sample (population) of different neurons to address the experimental question at hand. To achieve a sufficient sample, nearly all behavioral neurophysiology experiments rely on aggregating data across behavioral trials as well as across behavioral sessions.

Efforts to record simultaneously from multiple moveable microelectrodes in monkey began in the 1970s (Humphrey, 1970), as were chronically implanted microwire arrays (Chorover and DeLuca, 1972). A number of predecessors to current-day multielectrode solutions for monkeys were developed and first tested in the 1980s, including moveable quartz-glass coated electrodes (Reitbock and Werner, 1983), silicon-based multielectrode probes (Campbell et al., 1989, Drake et al., 1988) and stainless-steel housed linear electrode arrays (Barna et al., 1981). New electrode technologies are on the horizon (Patil and Thakor, 2016), while the future of high-density neuronal recording may also come from other emerging technologies (O'Shea et al., 2017, Seo et al., 2016).

Simultaneous recording of a neuronal population provides an number of benefits: 1) the opportunity to explore interarea relationships (e.g., functional connectivity, order of processing) (Zandvakili and Kohn, 2015, Zanos et al., 2011), 2) explore complex coding principles or associate events with mutual activity patterns (Abeles and Gerstein, 1988, Yu et al., 2014, Gawne and Richmond, 1993), 3) explore rare or single events (Hoffman and McNaughton, 2002), 4) real-time activities (e.g., control of a robotic arm through a brain-machine interface (BMI)) (Isaacs et al., 2000, Nicolelis, 2003, Nicolelis and Lebedev, 2009, Hochberg et al., 2006) and 5) improvement in the economy of collecting data (Kruger, 1983).

Commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) and semi-custom solutions provide methods to record hundreds of neurons simultaneously (MicroProbes for Life Science, Gaithersburg, MD; Blackrock Microsystems, Salt Lake City, UT; NeuroNexus, Ann Arbor, MI; Gray Matter Research, Bozeman, MT). Heroic custom solutions have demonstrated simultaneous recordings from over 500 electrodes (Schwarz et al., 2014, Hoffman and McNaughton, 2002). Our goal was to use COTS electrodes and minimum customization to increase the number of simultaneously recorded units to 768 while keeping the methods simple enough for ready reproduction by other laboratories.

2. Animal procedures

All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the ILAR Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Mental Health. Procedures adhered to applicable United States federal and local laws, regulations and standards, including the Animal Welfare Act (AWA 1990) and Regulations (PL 89-544; USDA 1985) and Public Health Service (PHS) Policy (PHS 2002).

Two male Macaca mulatta were used as subjects in this study, Monkey W (6.7 kg, age 4.5 y) and Monkey V (7.3 kg, age 5 y).

3. Electrodes

Each subject was implanted with eight 96-electrode arrays (Utah #7624, 10×10 array, 400 um pitch, iridium oxide tip, 1.5 mm depth, with 3 × Omnetics 36-pin 0.025″ connectors, Blackrock Microsystems, Salt Lake City, UT). Cables 4 cm long were used for posterior electrodes and 6 cm cables were used for the anterior sites. Electrodes were gas sterilized prior to surgery.

Approximately three months prior to electrode implantation, animals were acclimated to a primate chair, underwent surgery to install a head holding apparatus described elsewhere (Costa et al., 2016) and were trained on a two-arm bandit task.

4. Connector mounting platform (CMP)

One of the challenges of high electrode counts is finding a connection system for amplifying and recording the single unit potentials. That connection system occupies surface area on the skull, which must be shared with the head-holding device. Further, we did not want the electrode connections to overlap with the bone flap access to the electrode implantation sites. Keeping this bone flap separate avoids forces on the bone during healing that might disturb the electrodes. The separate bone flap also promotes healing by obviating the need to reinforce the flap with acrylic or stainless steel. From earlier experience, we were confident about using an ad hoc arrangement of connectors for 2 or 3 arrays, but the prospect of positioning 4 or more connector circuit boards prompted the development of a connector mounting platform (CMP) (Figs 1, 2) that was compact, easy to install at time of surgery, did not interfere with the head holding system, did not overlap the implantation area and allowed daily connection of 24 preamplifiers (32-channels each). Our solution was to custom fit each monkey with a biocompatible 3D-printed plastic Connector Mounting Platform.

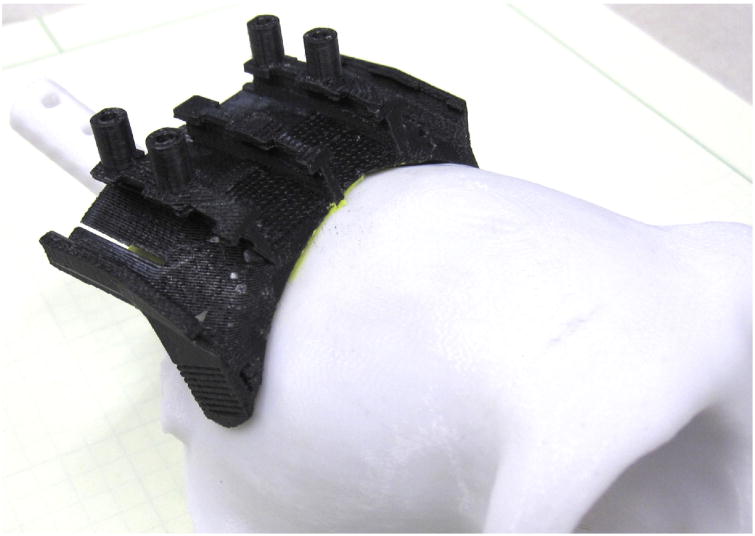

Fig 1.

Custom CMP fitted on 3D-printed model of skull. A CMP is printed in black to contrast with a white printed model of the skull to demonstrate customized fit. Modeling clay was used to hold the CMP for surgery planning.

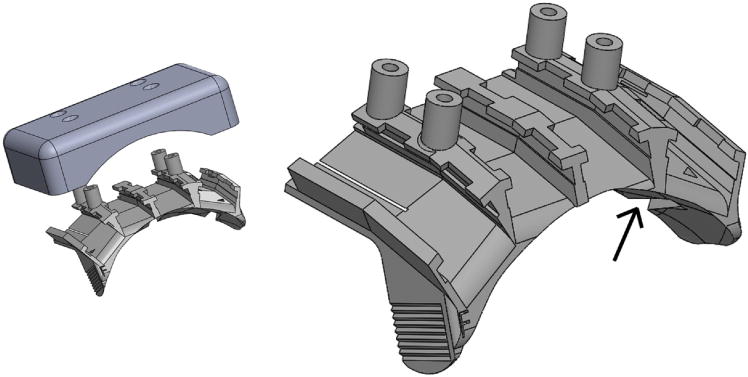

Fig 2.

Connector Mounting Platform (CMP). Left: The connector mounting platform and screw-on protective cap. Right: Close up of the platform. Arrow shows one of 4 void spaces that sits above a bone screw and is filled with bone cement. Overall width is about 6 cm.

The CMP used for the first surgery was developed over approximately 6 months and numerous revisions. The CMP went through several additional revisions following the first surgery. The methodological changes between surgeries included assembly of the array connectors onto the CMP prior to surgery, better protection of electrical connections during and after surgery, and a more robust cover for the CMP. CMP and related methods described here reflect advances made in the course of working with both subjects.

After training, each animal was scanned in a Siemens Force Scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Malvern, PA) computed tomography (CT) scanner (slice thickness=0.5 × 0.25 mm, 130 kV, rotation time=1.0 s, acquisition 192 × 0.6 mm, table pitch 0.8 mm). The scans were then edited with OsiriX (Pixmeo SARL, Bernex, Switzerland) to reduce the image to the surface of the skull along with the head holding device and associated bone fixation materials. This image was imported into 3D modeling software (Solidworks 2015, Dassault Systèmes, Waltham, MA) to fit the bottom of the CMP to the curvature and topography of the skull surface and the position of the head holding device (Fig 1). In addition, we collected a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) T1 image series for each monkey. The printed model of the skull and CMP, together with the MRI series were used in planning the placement of electrodes, bone flap, CMP and support screws for surgery.

Fig 2 shows mechanical drawings of the CMP and its cover. The platform has a series of printed circuit board guides (Figs 2, 3). Four sets of guides are positioned symmetrically relative to the midline. The guides accommodate the 8 circuit boards for the 8 electrode arrays. Circuit boards are roughly 12.5 mm wide and 14 mm long. Each set of guides holds 2 circuit boards, one anterior and the other posterior when the platform is mounted on the skull. The angles of the anterior and posterior circuit boards are offset from each other by 12.5 degrees (Fig 3). Gaps below each circuit board provide room for routing the electrode cable and ground/reference wires that emanate from the bottom of each circuit board.

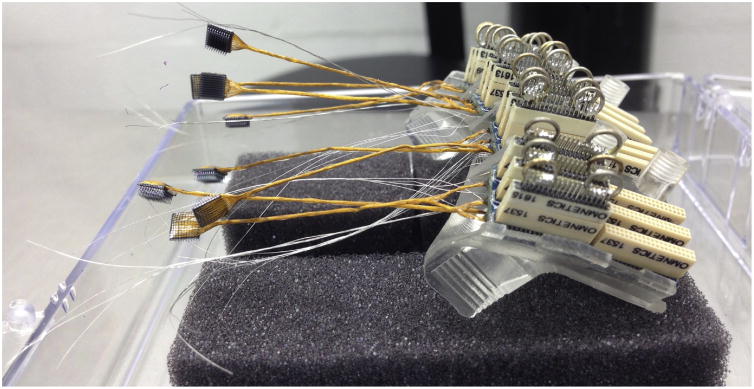

Fig 3.

Preparing the CMP for sterilization. The circuit boards for all 8 Blackrock electrode arrays are mounted on the CMP. Half of the connectors in the photograph have been fitted with mating Omnetics connectors to prevent contamination of the mating pins. The other half were also fitted before sterilization.

Cutouts (grooves) on the underside of the CMP are positioned where bone screws will be located (one cutout is identified with an arrow in Fig 2, right). Bone cement is used to fill this void and anchor the platform to the bone screws, as described in detail below. Serrated edges on either side of the platform provide an additional surface for securing the platform to screws with bone cement. Four #2 screws are used to fit the cover (Fig 2, left) firmly to the platform in between recording sessions.

The final version of the CMP was printed on a ProJet 6000 printer (3D Systems, San Francisco, CA) using VisiJet Clear plastic that was post-processed for biocompatibility using the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. The printer files for monkey V (cmp.stl and cmp_cover.stl) are available for download at ftp://helix.nih.gov/lsn/stl_files/. The CMP was assembled with the 8 arrays and sterilized before surgery (Fig 3). Pre-assembly greatly reduced surgery time. Prior to surgery, the arrays were reflected back and tethered to the protective cap mounting posts to keep them away from the surgical field until needed. We have also tested using polyethylene glycols (CARBOWAX P146-3, PEG 3350, Dow Chemical) to protect the electrodes prior to insertion. This wax can be selected for a low melting point and is easily dissolved off the electrodes at the time of surgery using warm saline. Dirt and debris accumulation in the Omnetics connectors on the circuit boards can be a major problem for recording. It is possible to clean each Omnetics connector contact using a surgical microscope, a tiny probe and suction, but this is an arduous and time-consuming task. After testing several methods of protecting the connections, we settled on using modified mating connectors (NSD-36-AA-GS 36 Position Dual Row Female Nano-Miniature .025″/.64mm Connector w/straight tails, part number A79023-001, Omnetics Connector Corp., Minneapolis, MN). The modification is to solder two rings of wire to the solder pins of each connecter to ease removal (Fig 3). Soldering must be done with a minimum of heat to avoid melting the insulation between pins.

5. Surgery

All animals were fasted for 24-hours prior to surgery and received a single dose of dexamethasone (4 mg, IM) and Cefazolin (25 mg/kg) to prevent infection. The monkeys were initially sedated with ketamine (10 mg/kg, IM) and surgical anesthesia achieved for the duration of the procedure with isoflurane (1-4% to effect). Vital signs (i.e., heart rate, respiration patterns, SpO2, blood pressure, and body temperature) were continuously monitored, and temperature maintained between 36 and 37.5 °C with a heating pad. Animals were hyperventilated to reduce expired carbon dioxide levels (25 ± 2 mmHg) to aid in reducing brain volume. Mannitol (30%; 30 cc IV for 20 min) was administered to further reduce brain volume & increase accessibility. The head of the animal was secured in a custom head holder that allows for easy movement in all directions. The monkeys' heads were shaved, cleaned and disinfected using 3 series of betadine and alcohol scrubs. Standard sterile surgical procedures were followed throughout.

Superficial tissues (skin, galea) were incised and retracted in distinct anatomical layers and the temporalis muscles detached and retracted to provide access to a large portion of the dorsal skull. All connective tissue was elevated and removed from the exposed bone, and a thin coat of Copalite Varnish (Temrex Corporation, Freeport, NY) was applied to the bone to create an infection barrier. The solvents in the Copalite Varnish have antimicrobial and antiviral properties and slow the growth of connective tissues under the CMP attachment. A printed copy of the CMP without the arrays attached was used to confirm fit and location on the skull. The placement of 4-6 titanium screws (T270.06T, Veterinary Orthopedic Implants) and the outline of a bone flap were marked on the skull as determined in surgical pre-planning. Each screw was then inserted followed by cutting of the bone flap using a diamond edged circular dental drill bit. A single bone flap extending 2-3 cm rostral-caudal and 7-8 cm laterally was removed. The bone flap crossed the midline providing access to prefrontal cortex of both hemispheres (Fig. 4). Four to six small holes (1.5 mm) were drilled along the caudal and laterally edges of the bone flap and adjacent skull to thread sutures for later closing. The edges of the skull and the bone flap were smoothed and the flap stored in sterile saline until replaced near the end of the surgery. To maximize exposure of the prefrontal cortex, the target of the array implants, the craniotomy was extended rostrally approximately 2-3 mm toward the orbital ridge with the aid of a rongeur. The bone edge was smoothed removing all rough or sharp edges and then sealed with bone wax. Once the opening was finalized we guided 3-0 vicryl suture through each of the pre-drilled holes in the skull, these would be used later to secure the bone flap back in place after closure of the dura. Two such sutures are visible in the lower part of Fig 4. During the rest of the procedure, prior to replacing the bone flap, the sutures were held out of the way using the wet sponges used to keep the skin moist throughout the surgery. Once the dura had been exposed it was routinely flushed with saline to keep it moist, which maintains its health and aids its closing after the array implantations are completed.

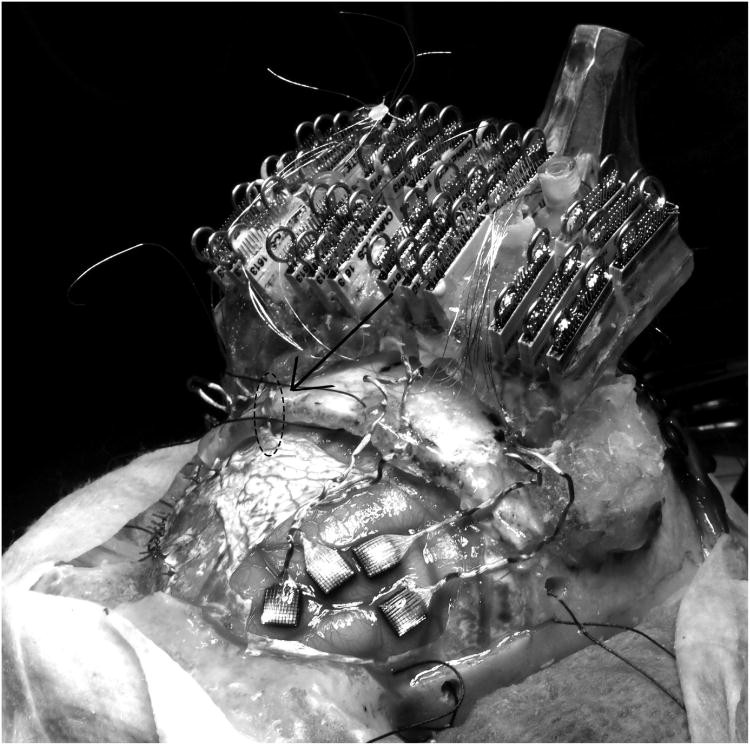

Fig 4.

Placement of electrodes. Four of the 8 electrodes are shown implanted in the prefrontal cortex of the left hemisphere prior to dura closure. Note that the right side electrodes are already implanted and the dura closed. Arrow and dashed oval identify a cable emerging from the closed dura on the left side. Cables on the right side are in their final positions just prior to dura closure.

After the bone flap was removed, the CMP with the 8 arrays was joined to the bone using bone cement (Ortho-jet powder and liquid, Lang Dental Manufacturing Co., Wheeling, IL) and the embedded screws. At this stage we used sufficient cement to ensure the CMP would not move during surgery (an important consideration for these arrays, generally), but more cement was added after closure to fully secure its placement. While attaching the CMP to the skull, the electrodes, dangling on their cables, were protected by carefully grouping the four cables together and pulling them out of the way.

A U-shaped dural flap was made over one hemisphere and reflected across the midline. Target sites for the four arrays were identified and four of the electrodes were roughly aligned to their individual target placement sites. The sequence for inserting the arrays was from caudal to rostral and medial to lateral to minimize the interference of array cables not yet inserted with the array being inserted. Fixing the cable to the edge of the bone and keeping the portion of the cable within the bone defect as short as possible was found to be advantageous whenever implanting more than one array. Minimizing cable within the defect minimizes the amount of cable manipulation necessary for the whole group of electrodes (Fig 4). This direct cable path was achieved by first creating a slot in the bone using a drill with a small bur. The slot allowed for the cable to pass close to dura. The bone was carefully dried and the cable secured in the slot using a UV light cured resin (Triad Gel, Dentsply International, York, PA). When placing the cable in the slot care was taken to orient the electrodes of the array towards the cortex to help minimize having to manipulate the cable. The cable is then “kinked”, “twisted”, and “bent” using plastic tipped forceps so that the electrodes of the array sat flat on the desired target of the cortex. The Blackrock Pneumatic Inserter (Blackrock Microsystems, Salt Lake City, UT) was used to push the array into the cortex. The procedure was repeated until all four arrays were seated in the prefrontal cortex, three above the principal sulcus and one below. Care was taken not to disturb an array previously inserted into the cortex. The dura was then closed using 5-0 vicryl suture. The dural opening was intended to be large enough so none of the sutures was directly above an array. Sutures were spaced approximately 2 mm apart with the cables fitting easily between knots. The insulation on the ground/reference wires was removed with a scalpel and the wires from two arrays were carefully twisted together and then placed under the dura by slipping the wires between the individual sutures directed away from the arrays. This was repeated until all four sets of wires were inserted. Once complete, the dura in the opposite hemisphere was opened and the remaining four arrays were placed following the same procedure.

The bone flap was replaced and secured using the 3-0 vicryl sutures already in position as described earlier. No additional brackets or cement was used to fasten the flap to the skull. Once the flap was in place additional bone cement was added around the CMP. The minimum amount of cement was used to ensure the CMP was secured to the skull. The edges of the cement were rounded and smoothed and the distance from the edge of the cement to the seam of the bone flap maximized. This is important as it is most often the case that the skin around the acrylic used here will retract to the edge of the cement before attaching to the bone. If the seam is not a sufficient distance from the cement, it is possible the seam will be exposed which may lead to skin necrosis along the edge of the flap. The excess cables of the array were tucked into the space under the connector boards on the CMP and covered with cement. The remaining length of cable leading to the implanted electrodes was covered with the UV light cured resin. Care must be taken to maximize the space between cables and to minimize the resin needed to protect the cable as it rests on the bone. This maximizes bone exposure between the cables and improves bone-to-bone contact between the bone flap and the intact skull, promoting bone growth to the reattached flap. The skin was closed in anatomical layers using a 3-0 vicryl suture for the facia and a 3-0 ethilon suture for the outer skin.

Surgery required 8 hr for the first animal. In that surgery the arrays were not pre-assembled on the CMP. Pre-assembly of the CMP saved about 90 minutes during the second surgery. The surgeon was very experienced with implantation of the arrays before this project, which helped keep the overall surgery time to a minimum.

The monkeys were placed in a recovery cage where they recovered in an oxygen, humidity and heat controlled environment while being monitored. Standard post-operative treatment included analgesics (e.g., buprenorphine (0.02-0.05 mg / kg, IM q 6-12 hr.), or ketoprofen (1–2 mg / kg BID × 3 days) followed by ibuprofen (100 mg PO BID × 4 days) and antibiotics. Dexamethasone (4 mg, IM, BID) was provided for 5-7 days before being weaned off. Recovery in each case was uneventful with animals eating and drinking and showing normal behavior the day following the surgery. After three days they were returned to their home cages.

6. Recording arrangement

Recordings were carried out using the Grapevine System (Ripple, Salt Lake City, UT), consisting of two Neural Interface Processors (NIPs), 24 32-channel Nano head stages (Fig 5), and two each Analog and Digital Front End units. These make up two, independent, 384-channel data acquisition systems. Each system was hosted on a Dell OptiPlex XE2 computer (i7-4770S processor, 16 GB RAM) running Microsoft Windows 7 Professional 64-bit. A separate Ethernet card (Intel EXPI9301CT) was used for communications with the NIP. We used the open source MonkeyLogic behavioral control software (http://www.brown.edu/Research/monkeylogic/) to send event codes to both acquisition systems in parallel through the 16-bit digital inputs. The two systems were synchronized by the simultaneous recording of event codes, which are time-stamped and stored in each data stream at the digital sample rate of the hardware (30 kHz). Eye tracking data, recorded with a MCU02 ViewPoint Eye Tracker with the Analog Output option (Arrington Research, Scottsdale, AZ), was sent in parallel to the Analog Front Ends of both systems. Newer software for the NIP now permits two NIPs to link via an Ethernet connection. The Ethernet connection obviates the need for having two Analog and Digital Front Ends and frees up a NIP input for 128 additional electrode channels. We have not tried the Ethernet connection.

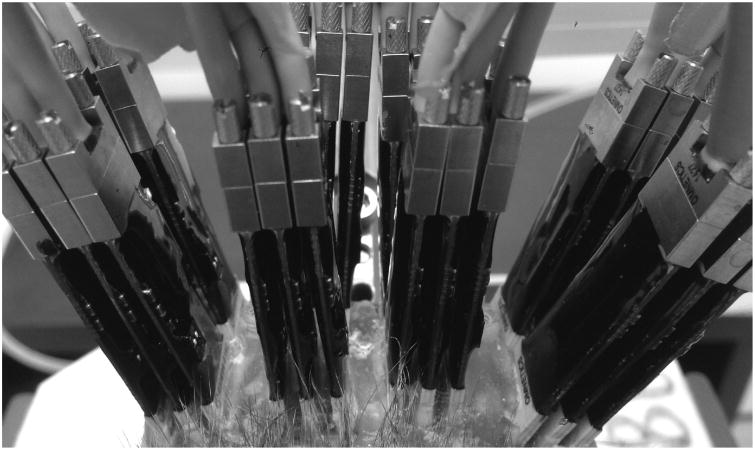

Fig 5.

24 32-channel Nano head stages during recording. Each Nano head stage mates with an Omnetics connector on the Connector Mounting Platform. The design of the CMP tilts each group of head stages to provide spacing for convenient insertion and removal.

Nano head stages, which are connected in groups of 4 to the Front End Cables of the Grapevine System, are stored safely and conveniently using custom printed holders (Fig 6.) Six holders are attached side-by-side to an acrylic panel on the wall in the recording room. A printer file for the holder is available for download at ftp://helix.nih.gov/lsn/stl_files/nano_holder.stl.

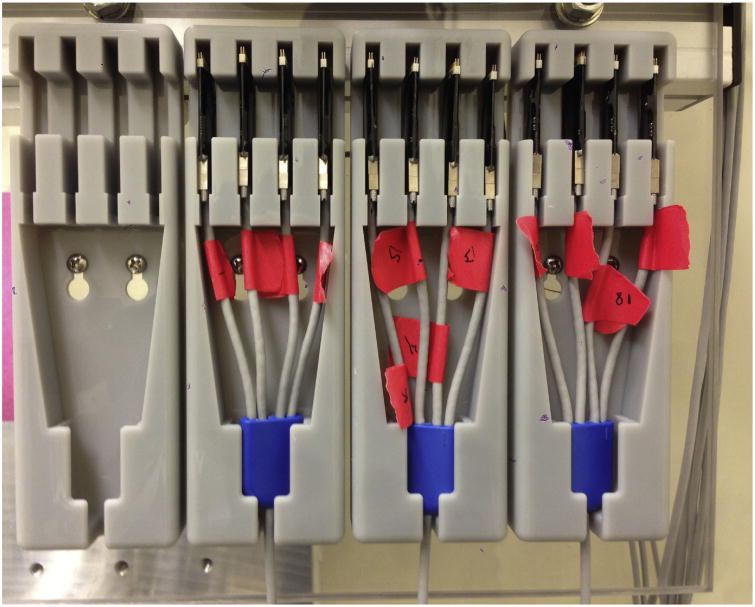

Fig 6.

Printed Nano holder. Four Nanos insert gently into the top 4 slots of each holder. The ferrule of the Front End Cable inserts gently into the lower slot as the main cable passes through the bottom of the holder.

7. Spike sorting and data collection

Signals from each group (left and right hemisphere) of 384 electrodes were displayed on wide-screen computer monitors in a 13 × 15 format using the on-line Grapevine software (Fig 7). Two operators, one at each computer, sorted spikes prior to each recording session in some sessions. Sorting required 60-90 minutes. Trigger thresholds for an electrode channel were set automatically to 5.5 times the median of the raw signal on that channel. On-line sorting was carried out by the operators by creating and adjusting time-amplitude windows. Spike waveforms (“snippets”) were saved and re-sorted off line using Offline Sorter (Plexon, Inc., Dallas, TX). The minimum ISI for single units was chosen to be 2.0 ms. When the waveforms from an isolation presented with >2% of ISIs below that threshold, the waveforms collected were labeled as multiunit activity and not included in this report.

Fig 7.

Spikes for each group of 384 electrodes are sorted on a separate computer using the Ripple Grapevine software.

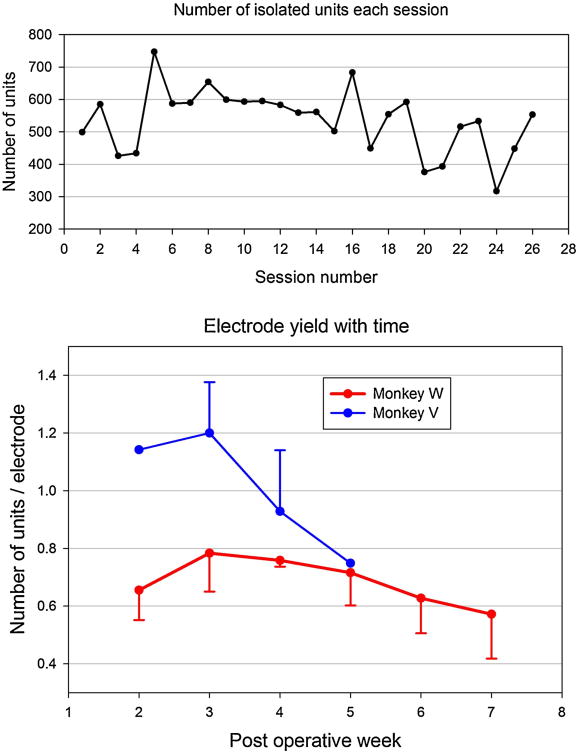

For the first subject (monkey W), on average, 0.70 ± 0.13 units/electrode were isolated from each electrode, based on the 26 recording sessions (535.7 units/session) where all arrays were utilized (Fig 8, top). That average was consistently higher for the second subject (monkey V, 1.05 ± 0.23 units/electrode, 806.9 units/session) (Fig 8, bottom). There is an apparent drop-off in yield (units/electrode) after the 3rd post-operative week that is especially evident in monkey V. Over all sessions, 14,747 units were collected over 37 calendar days (398.6 units/day) in monkey W and 5,648 units were collected over 22 days (256.7 units/day) in monkey V. To examine longer-term changes in yield, monkey W was tested for 23 days (8 recording sessions) starting 16 weeks after surgery. On average, the yield dropped to 0.06 ± 0.01 units/per electrode.

Fig 8.

Numbers of isolated neurons across recording sessions. Top: Number of isolated units each session for monkey W. Bottom: Average number of units/electrode each post-operative week for both monkeys. Each week includes from 3 to 6 sessions. No recordings were attempted during the first week.

8. Discussion

The described method requires access to MRI, CT and bio-compatible plastic printing, substantial surgical training and experience, and access to high-capacity single-unit recording apparatus. Given these, the method we describe provides a manageable roadmap of how to reliably implant hundreds of electrodes and record simultaneously from a large population of single-units. The primary contributions of this work are a method to minimize cranial surface area required for electrode connectors, a method to reduce surgery time and a detailed description for surgical planning and electrode implantation. These advantages should be applicable when using 3 or more electrode arrays at a time. Although not discussed, the same electrode methods are amenable to local field potential recording and electrical stimulation.

The limitations of this method will be apparent to experienced nonhuman primate electrophysiologists. The Blackrock array electrodes are designed for cortical surface recordings and are not mobile. Thus, this method cannot be used to explore deep structures or permit relocating the electrodes during the experiment, features of some other published high electrode count systems (Schwarz et al., 2014, Hoffman and McNaughton, 2002). The present design relies on a special platform (CMP) to consolidate the connector circuit boards. Major changes to the CMP might be required to target a different region of the cortex and the CMP approach may not be helpful when cortical targets are not clustered in one restricted region. Finally, the need for a CMP may be obviated by future developments. Electrodes utilizing higher density connectors, integrated multiplexors or wireless transmission could relieve the need to tightly conserve head-mounted real estate. Until then, customized printed platforms are likely to play an important role in high density recording options for nonhuman primate research.

Highlights.

We recorded simultaneously from 768 electrodes in the cortex of nonhuman primates

In two animals we averaged 536 and 807 units/session in the first month of recording

Plastic printing provided a custom mounting platform for connecting to 8 Utah arrays

Surgical preparation and procedures minimized surgery difficulty and time

Simple, but important steps are essential to protect connector contacts

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Dennis Johnson of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center Radiology Department and Dr. John Ostuni of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke for their valuable assistance imaging and preparing 3D models for printing. We thank Dr. Rossella Falcone for her aid with unit count data. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health (ZIA MH002928-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abeles M, Gerstein GL. Detecting spatiotemporal firing patterns among simultaneously recorded single neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1988;60:909–24. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.3.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barna JS, Arezzo JC, Vaughan HG., JR A new multielectrode array for the simultaneous recording of field potentials and unit activity. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1981;52:494–6. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(81)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell PK, Normann RA, Horch KW, Stensaas SS. A chronic intracortical electrode array: preliminary results. J Biomed Mater Res. 1989;23:245–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorover SL, Deluca AM. A sweet new multiple electrode for chronic single unit recording in moving animals. Physiol Behav. 1972;9:671–4. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(72)90030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa VD, Dal Monte O, Lucas DR, Murray EA, Averbeck BB. Amygdala and Ventral Striatum Make Distinct Contributions to Reinforcement Learning. Neuron. 2016;92:505–517. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake KL, Wise KD, Farraye J, Anderson DJ, Bement SL. Performance of planar multisite microprobes in recording extracellular single-unit intracortical activity. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1988;35:719–32. doi: 10.1109/10.7273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evarts EV. Pyramidal tract activity associated with a conditioned hand movement in the monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1966;29:1011–27. doi: 10.1152/jn.1966.29.6.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawne TJ, Richmond BJ. How independent are the messages carried by adjacent inferior temporal cortical neurons? J Neurosci. 1993;13:2758–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-02758.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg LR, Serruya MD, Friehs GM, Mukand JA, Saleh M, Caplan AH, Branner A, Chen D, Penn RD, Donoghue JP. Neuronal ensemble control of prosthetic devices by a human with tetraplegia. Nature. 2006;442:164–71. doi: 10.1038/nature04970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman KL, Mcnaughton BL. Coordinated reactivation of distributed memory traces in primate neocortex. Science. 2002;297:2070–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1073538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey DR. A chronically implantable multiple micro-electrode system with independent control of electrode positions. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1970;29:616–20. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(70)90105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey DR, Schmidt EM. Extracellular single-unit recording methods. In: Boulton AA, Baker GB, Vanderwolf CH, editors. Neurophysiological Techniques: II Applications to Neural Systems. Clifton, NJ: Humana; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs RE, Weber DJ, Schwartz AB. Work toward real-time control of a cortical neural prothesis. IEEE Trans Rehabil Eng. 2000;8:196–8. doi: 10.1109/86.847814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger J. Simultaneous individual recordings from many cerebral neurons: techniques and results. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1983;98:177–233. doi: 10.1007/BFb0033868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolelis MA. Brain-machine interfaces to restore motor function and probe neural circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:417–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolelis MA, Lebedev MA. Principles of neural ensemble physiology underlying the operation of brain-machine interfaces. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:530–40. doi: 10.1038/nrn2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'shea DJ, Trautmann E, Chandrasekaran C, Stavisky S, Kao JC, Sahani M, Ryu S, Deisseroth K, Shenoy KV. The need for calcium imaging in nonhuman primates: New motor neuroscience and brain-machine interfaces. Exp Neurol. 2017;287:437–451. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil AC, Thakor NV. Implantable neurotechnologies: a review of micro- and nanoelectrodes for neural recording. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2016;54:23–44. doi: 10.1007/s11517-015-1430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitbock HJ, Werner G. Multi-electrode recording system for the study of patio-temporal activity patterns of neurons in the central nervous system. Experientia. 1983;39:339–41. doi: 10.1007/BF01955338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz DA, Lebedev MA, Hanson TL, Dimitrov DF, Lehew G, Meloy J, Rajangam S, Subramanian V, Ifft PJ, Li Z, Ramakrishnan A, Tate A, Zhuang KZ, Nicolelis MA. Chronic, wireless recordings of large-scale brain activity in freely moving rhesus monkeys. Nat Methods. 2014;11:670–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo D, Neely RM, Shen K, Singhal U, Alon E, Rabaey JM, Carmena JM, Maharbiz MM. Wireless Recording in the Peripheral Nervous System with Ultrasonic Neural Dust. Neuron. 2016;91:529–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Klaus A, Yang H, Plenz D. Scale-invariant neuronal avalanche dynamics and the cutoff in size distributions. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandvakili A, Kohn A. Coordinated Neuronal Activity Enhances Corticocortical Communication. Neuron. 2015;87:827–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanos TP, Mineault PJ, Monteon JA, Pack CC. Functional connectivity during surround suppression in macaque area V4. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2011;2011:3342–5. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2011.6090906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]