Abstract

Background

Despite the increasing prevalence of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in humans, there remains no evidence-based therapies for HFpEF. Endothelin-1 (ET-1) antagonists are a possibility because elevated ET-1 levels are associated with adverse cardiovascular effects, such as arterial and pulmonary vasoconstriction, impaired left ventricular (LV) relaxation, and stimulation of LV hypertrophy. LV hypertrophy is a common phenotype in HFpEF, particularly when associated with hypertension.

Methods and Results

In the present study, we found that ET-1 levels were significantly elevated in patients with chronic stable HFpEF. We then sought to investigate the effects of chronic macitentan, a dual ET-A/ET-B receptor antagonist, on cardiac structure and function in a murine model of HFpEF induced by chronic aldosterone infusion. Macitentan caused LV hypertrophy regression independent of blood pressure changes in HFpEF. Although macitentan did not modulate diastolic dysfunction in HFpEF, it significantly reduced wall thickness and relative wall thickness after 2 weeks of therapy. In vitro studies showed that macitentan decreased the aldosterone-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. These changes were mediated by a reduction in the expression of cardiac myocyte enhancer factor 2a. Moreover, macitentan improved adverse cardiac remodeling, by reducing the stiffer cardiac collagen I and titin n2b expression in the left ventricle of mice with HFpEF.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that dual ET-A/ET-B receptor inhibition improves HFpEF by abrogating adverse cardiac remodeling via antihypertrophic mechanisms and by reducing stiffness. Additional studies are needed to explore the role of dual ET-1 receptor antagonists in patients with HFpEF.

Keywords: endothelin-1, endothelin receptor antagonists, heart failure, diastolic, hypertrophy, left ventricular, myocytes, cardiac

Heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a clinical syndrome and a disease characterized by signs and symptoms of HF, a preserved left ventricular (LV) EF (≥50%) and, is often, accompanied by abnormalities in diastolic function.1 Despite similarities in presenting symptoms, fundamental differences exist between HFpEF and HF with reduced EF (HFrEF), the most significant of which is the lack of approved evidence-based therapies for HFpEF. Furthermore, the prevalence of HFpEF continues to increase, relative to HFrEF.2

Inadequately treated hypertension leads to adverse cardiac remodeling, diastolic dysfunction and the development of HF, particularly HFpEF. Hypertension is the most important risk factor for HFpEF, with a high prevalence seen in large controlled trials, epidemiological studies, and HF registries.3 The prevalence of hypertension in addition to other comorbidities commonly seen in HFpEF, such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, and atrial fibrillation, is projected to also increase.4 Yet therapies directed only at comorbidities remain inadequate in preventing and treating HFpEF. Therefore, there is a pressing need to identify new pathogenic mechanisms in HFpEF that might provide new pathways for which to target drug therapies.

Mechanisms purported to play a role in HFpEF include vascular dysfunction,2 alterations in extracellular matrix composition,5 and modification of the intrinsic contractile properties of cardiomyocytes.6 Moreover, maladaptive LV hypertrophy (LVH) and diastolic dysfunction (DD), both frequently seen in HFpEF, although not mutually exclusive, may also provide mechanistic insights. An improvement in DD is not necessarily associated with a reduction of LVH7 and conversely a reduction in LVH may not result in an improvement of DD. Differences in the molecular signals that modulate maladaptive LVH may explain the disparate responses to the approved evidence-based therapies in HFrEF and HFpEF. Thus, elucidating the mechanisms of maladaptive LVH regression could provide insights into developing new targets for treatment.

One such possibility is endothelin-1 (ET-1) antagonists. Although ET-1 levels are elevated and predict mortality in patients with HFrEF, ET-1 antagonists have not demonstrated beneficial outcomes in humans with HFrEF.8 ET-1, as well as both its receptors ET-A and ET-B, are synthesized and secreted by cardiac myocytes and other cells of the heart.9 ET-1 synthesis in cardiac myocytes is increased during the hypertrophic response.10 Likewise, the contribution of ET-1 to abnormalities in endothelial function, vascular compliance, pulmonary hypertension, impaired diastolic relaxation and myocardial fibrosis, implicates ET-1 in the pathophysiology of HFpEF. Therefore, ET-1 inhibition could have therapeutic applications in HFpEF.

The present study demonstrates that circulating levels of ET-1 are increased in patients with chronic, stable HFpEF. Therefore, we hypothesized that ET-1 blockade modulates structural, functional, and molecular alterations in HFpEF. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of macitentan, a dual ET-A/ET-B receptor antagonist, in a murine model of HFpEF and to investigate the mechanisms implicated in those effects.

Methods

Detailed methods are available in the Data Supplement.

Human Population

Chronic, stable patients with HFpEF (n=30) were enrolled from an outpatient HF Clinic at Boston Medical Center. Patients with HFpEF were included if they were previously admitted with a HFpEF exacerbation to the HF service within the previous year and had a LVEF >50% as measured by echocardiogram within 6 months before enrollment. Healthy, control subjects without HF or known cardiac disease were also enrolled (n=10). Controls had normal blood pressure (BP) and were not taking cardiovascular medications. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the collection of clinical samples. The study was approved by the Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board and conducted according to Declaration of Helsinki principles. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are included in the Data Supplement.

Serum ET-1 Measurements

Total circulating levels of ET-1 were measured in serum samples by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D systems, Inc, Minneapolis, MN). Standards, controls, and samples were run in triplicate and averaged. The protein concentrations were calculated using a standard curve generated with recombinant standards provided by the manufacturer.

Animal Study

The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Boston University School of Medicine approved all study procedures related to the handling and surgery of the mice.

Animal Model of HFpEF

This murine model of HFpEF recapitulates the following aspects of human HFpEF: pulmonary congestion, preserved LVEF, DD, LVH, moderate hypertension, and exercise intolerance.7,11,12 Importantly, aldosterone levels are not supratherapeutic and compares well to acute human HF.11,12 Eight-week-old C57BL/6J male mice (Jackson Laboratories) were anesthetized with 80 to 100 mg/kg ketamine and 5 to 10 mg/kg xylazine intraperitoneally. All mice (20–25 g) underwent uninephrectomy and then received either a continuous infusion of saline (Sham) or d-aldosterone (0.30 μg/h; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; HFpEF) for 4 weeks via osmotic minipumps (Alzet, Durect Corp., Cupertino, CA). All mice were maintained on 1.0% sodium chloride drinking water. Two weeks post surgery, mice were randomized to receive either normal chow or chow-containing macitentan, a dual ET-A/ET-B receptor antagonist (MACI; 30 mg/kg per day; Figure I in the Data Supplement).

Chronic aldosterone for 4 weeks duration weeks induced the HFpEF phenotype.7,13 Mice were then euthanized at the end of 4 weeks. The 4 groups studied were as follows: (1) Sham: normal chow; (2) HFpEF: normal chow; (3) Sham-MACI: chow-containing MACI; and (4) HFpEF-MACI: chow-containing MACI (n=10–16 per group).

In a dose–response protocol, mice (n=3–6 per group) were fed chow with 2 different macitentan doses (10 and 30 mg/kg per day) 2 weeks after surgery, once hypertension was apparent.7,13 The dose of 30 mg/kg per day was selected as there were changes in cardiac hypertrophy that were independent of changes in body weight and systolic BP (Table I in the Data Supplement).

Physiological Measurements

Systolic and diastolic BP and heart rate were measured weekly using a noninvasive tail-cuff BP analyzer (BP-2000 Blood Pressure Analysis System; Visitech Systems, Inc., Apex, NC). Transthoracic echocardiography was performed at the end of 4 weeks to assess structure and diastolic function. See Data Supplement for further details. Mice were euthanized after these measurements. The ratio of wet:dry lung weight was determined as an indicator of pulmonary congestion.

In Vitro Studies

Isolation and Treatment of Adult Rat Cardiac Myocytes

Primary cultures of isolated adult rat ventricular cardiac myocytes (ARVM) were prepared as previously described.14,15 ARVM (90%–95% purity) were harvested from adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (≈200–220 g) and plated in a nonconfluent manner on laminin-coated (1 μg/cm2; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) plastic culture dishes (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) at a density of 30 to 50 cells/mm2. Cardiac myocytes were maintained at 37°C before treatment in Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (Invitrogen) containing 2 mg/mL BSA, 2 mmol/L L-carnitine, 5 mmol/L creatinine, 5 mmol/L taurine (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 10 g/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen).

ARVM were pretreated with or without macitentan (MACI; 10 μmol/L) for 30 minutes and were then stimulated with 1 μmol/L d-aldosterone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; n=6 experiments for all conditions).

Statistical Analysis

Normality of distributions was verified by D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test. Differences between 2 groups were analyzed by 2-tailed unpaired Student t tests or Mann–Whitney U test as parametric and nonparametric tests, respectively. Specific differences among at least 3 groups were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA and the Newman–Keuls post hoc test for normal distribution, and Kruskall–Wallis test followed by Dunn test for non-normal distribution variables. Spearman test was used to determine the correlation between ET-1 levels and echocardiographic measurements of PA pressures in patients with HFpEF. Pearson test was used to determine the correlation between titin N2B and collagen 1 mRNA expression in the experimental model. P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results

ET-1 Serum Levels Were Elevated in Humans With Chronic, Stable HFpEF

Patients were recruited from an ambulatory HF clinic and had chronic, stable HFpEF (Table II in the Data Supplement). Mean New York Heart Association functional class was 2.1±0.7 at the time of enrollment. The HFpEF cohort was predominantly black (66%), women (62%), and mean age was 64±7 years. Comorbidities included hypertension (87%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (62%), and obesity (90%) and mean body mass index was 38.75±8.2 kg/m2. Mean LVEF and LV mass were 63.9±6.3% and 200.2±54.4 g (normal <162 g), respectively. DD was present in 72% of patients with HFpEF and is comparable to other community HFpEF cohorts.16 Additional evidence of cardiac remodeling was seen with increased relative wall thickness (0.52±0.19) and left atrial volume index (37.8±4.2 mL/m2). Mean circulating levels of brain natriuretic peptide were also elevated (254±287 pg/mL).

Circulating Levels of ET-1

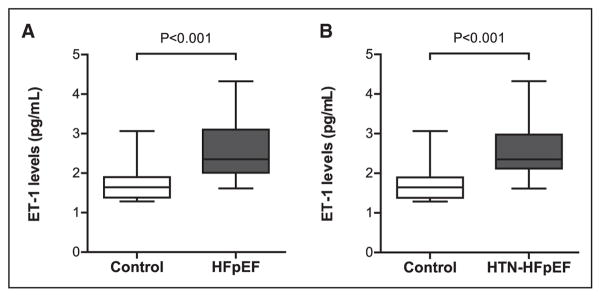

As shown in Figure 1, HFpEF patients had higher serum levels of ET-1 than controls (2.61±0.81 versus 1.74±0.52 pg/mL; P<0.001). Elevated pulmonary artery systolic pressure is often seen in HFpEF17 and was evident in this cohort of HFpEF patients. Pulmonary artery systolic pressure was 41.6±10.8 mm Hg (range, 24–59 mm Hg) and showed a positive correlation with the ET-1 levels (R=0.627; P<0.01; 95% confidence interval, 2.744–13.34). A subgroup of patients from this cohort with only hypertension-associated HFpEF (n=26) was selected to more closely resemble the hypertension-induced HFpEF murine model. These hypertension-associated HFpEF patients also demonstrated elevated ET-1 levels (2.62±0.79 pg/mL) versus controls (1.74±0.52 pg/mL; P<0.001; Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Serum endothelin (ET)-1 levels in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). A, ET-1 levels are increased in patients with chronic, stable HFpEF (n=30) vs controls (n=10), and (B) in a subcohort (n=26) of only those patients with hypertension-associated HFpEF (HTN-HFpEF).

ET-1 Antagonism Reduced Cardiac Hypertrophy in Mice With HFpEF

Diastolic Function and LV Structure in Macitentan-Treated Mice With HFpEF

We examined the impact of dual ET-A/ET-B receptor blockade with macitentan on LV structure and diastolic function in mice with HFpEF (Table). As expected, chronic aldosterone caused DD in HFpEF mice versus Sham. HFpEF mice had a higher peak E velocity to peak A velocity ratio (E/A) and an increase in the isovolumetric relaxation time. These parameters were unaffected by macitentan treatment (E/A in HFpEF versus HFpEF-MACI, 1.85±0.09 versus 1.74±0.16; P=NS). Moreover, early filling deceleration time was similar in all the groups and LVEF was preserved. As previously shown, LV end-systolic dimensions were significantly decreased in both groups of HFpEF mice versus respective Shams (1.15±0.13 versus 1.57±0.11 mm; in HFpEF) and (1.64±0.12 versus 1.81±0.15 mm; in HFpEF-MACI) but were not different between HFpEF and HFpEF-MACI. Both groups of HFpEF mice also had a trend to decreased LV end-diastolic dimensions but were not significantly different between respective Shams and treatment group. Total wall thickness, relative wall thickness, and posterior wall thickness were increased by 1.40-, 1.47-, and 1.31-fold, respectively, in HFpEF mice compared with Sham (P<0.001), but these parameters were significantly decreased with macitentan treatment (0.88-, 0.81-, and 0.85-fold, respectively, in HFpEF-MACI versus HFpEF; P<0.05). Noticeably, these changes were independent of alterations in body weight, BP, and heart rate (Table). As expected, at 4 weeks, mice with HFpEF had moderate hypertension (138.6±1.1 versus 118.8±2.8 mm Hg; P<0.05 versus Sham); however, systolic BP in HFpEF-MACI mice was no different from HFpEF alone (135.4±2.0 mm Hg). Fulton index, as an indicator of right ventricular hypertrophy, was no different between all groups (Table). Lung congestion was significantly decreased in HFpEF-MACI mice versus HFpEF alone (P<0.05, Table). There were no deaths during the 4 weeks of aldosterone infusion in Sham or HFpEF mice with/without treatment with macitentan.

Table.

Characteristics of Mice With HFpEF (4 Weeks After Chronic Aldosterone) and Sham (Saline) Untreated or Treated With MACI

| Sham | Sham-MACI | HFpEF | HFpEF-MACI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 24.8±0.49 | 25.3±0.36 | 24.8±0.62 | 25.2±0.36 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 120±4.4 | 121±3.8 | 137±4* | 132±3* |

| Heart rate, bpm | 654±14 | 660±10 | 643±10.5 | 625±6.7 |

| Wet/dry lung ratio | 4.3±0.03 | 4.5±0.07 | 4.84±0.12† | 4.60±0.04‡ |

| Diastolic function | ||||

| E/A | 1.56±0.09 | 1.56±0.04 | 1.85±0.09* | 1.74±0.16 |

| IVRT, ms | 16.20±0.95 | 17.05±0.91 | 22.80±1.5* | 21.25±1.38* |

| DT, ms | 20.28±1.59 | 22.58±0.83 | 20.00±1.62 | 20.78±0.75 |

| Left ventricle structure | ||||

| LVEDD, mm | 3.26±0.09 | 3.36±0.13 | 3.02±0.12 | 3.33±0.09 |

| LVESD, mm | 1.57±0.11 | 1.81±0.15 | 1.15±0.13* | 1.64±0.12‡ |

| LVEF, % | 82.96±2.23 | 78.97±2.93 | 89.78±2.34 | 82.27±2.28 |

| TWT, mm | 0.72±0.05 | 0.77±0.03 | 1.01±0.04§ | 0.89±0.02†‡ |

| PWT, mm | 0.77±0.03 | 0.73±0.03 | 1.01±0.06§ | 0.86±0.02†‡ |

| RWT | 0.44±0.02 | 0.45±0.02 | 0.65±0.04§ | 0.53±0.02†‡ |

| Right ventricle structure | ||||

| Fulton index | 0.17±0.02 | 0.21±0.02 | 0.18±0.01 | 0.19±0.01 |

Data are means±SEM. DT indicates early filling deceleration time; E/A, the ratio of peak E velocity to peak A velocity; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; IVRT, isovolumetric relaxation time; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF, LV ejection fraction; LVESD, LV end-systolic diameter; MACI, macitentan; PWT, posterior wall thickness; RWT, relative wall thickness; and TWT, total wall thickness.

P<0.05 vs respective Sham.

P<0.01 vs respective Sham.

P<0.05 vs HFpEF. n=8–16 mice per group.

P<0.001 vs respective Sham. n=8–16 mice per group.

Morphological and Molecular LV Myocardial Changes in HFpEF Mice After Treatment With Macitentan

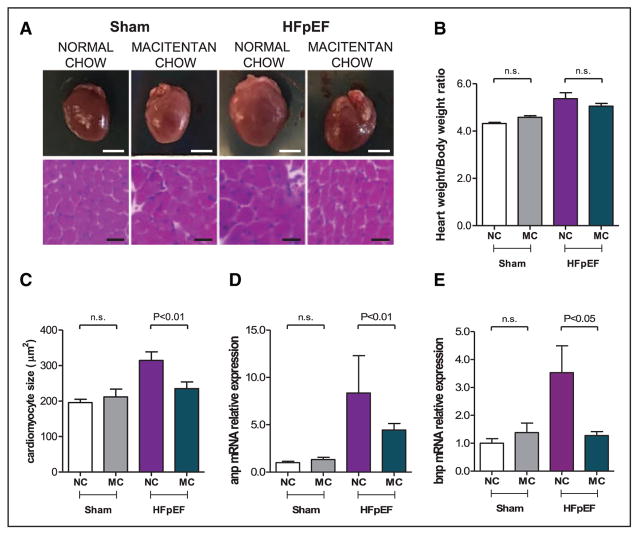

As previously described,13 HFpEF mice had cardiac hypertrophy, as measured by heart weight/body weight ratio (5.4±0.25 versus 4.3±0.05; P<0.001 versus Sham; Figure 2A and 2B). Cardiomyocytes were also increased in size (314±24 versus 196±9 μm2; P<0.01 versus Sham; Figure 2A and 2C), with increased LV mRNA expression of atrial and brain natriuretic peptides in HFpEF hearts versus Sham (P<0.05 for both; Figure 2C through 2E). Treatment with macitentan reduced cardiomyocyte size (235±19 μm2; P<0.01; Figure 2A and 2C) and decreased brain natriuretic peptide mRNA expression (P<0.05; Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Pharmacological inhibition of endothelin (ET)-1 reduced cardiac hypertrophy in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) mice. A, Representative macroscopic and microscopic (hematoxylin-eosin staining, ×20) images of the heart from sham and HFpEF mice fed a normal chow or treated with macitentan (30 mg/kg per day) for 2 weeks; scale bar is 25 mm and 25 μm, respectively. B, Heart weight:body weight ratio. C, Cardiomyocyte size and atrial natriuretic peptide (anp). D, Brain natriuretic peptide (bnp). E, Relative mRNA expression in the left ventricle of Sham and HFpEF mice fed a normal chow (NC) or chow mixed with macitentan (MC; 30 mg/kg per day) for 2 weeks. n=5 to 10 mice per group. Data shown as mean±SEM.

Mechanisms Implicated in the Antihypertrophic Effect of Macitentan

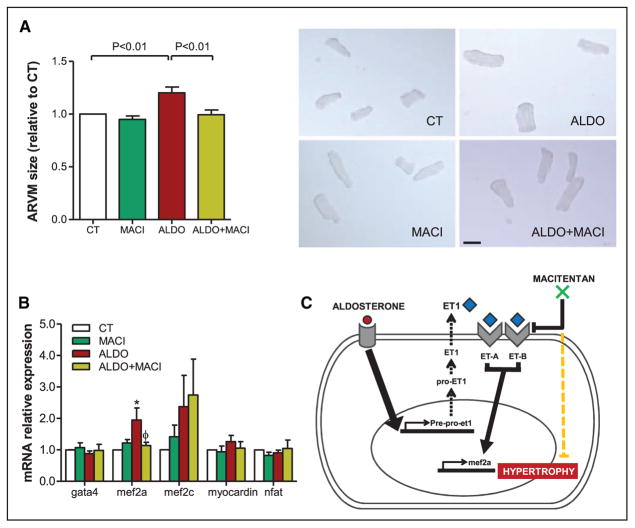

To investigate the mechanism of ET-1 receptor blockade in the observed antihypertrophic effects, we performed in vitro studies using ARVM stimulated with aldosterone (1 μmol/L) and pretreated with or without macitentan (10 μmol/L). Aldosterone stimulation induced prepro–ET-1 mRNA expression in cardiac myocytes, as previously described.18 Not unexpected, macitentan pretreatment did not affect prepro–ET-1 mRNA expression (Figure II in the Data Supplement). More importantly, as seen in vivo, pretreatment with macitentan reduced aldosterone-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by 28±1.0% (P<0.01 versus aldosterone alone; Figure 3A). To investigate the molecular underpinnings responsible of this effect, key signaling molecules involved in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy were measured, such as GATA binding protein 4 (gata4), myocardin, myocyte enhancer factor 2a (mef2a), and 2c (mef2c), and nuclear factor of activated T cells (nfat), in aldosterone-stimulated ARVM. The transcript encoding mef2a expression was increased by 1.95-fold in aldosterone-stimulated ARVM compared with control (P<0.05). Pretreatment with dual ET-A/ET-B receptor antagonist, macitentan, abrogated this mef2a expression (P<0.05). Neither aldosterone nor macitentan had an effect on gata4, myocardin, mef2c, or nfat expression (Figure 3B). Based on these in vitro findings, we conclude that aldosterone induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by activating ET-1 autocrine/paracrine signaling via mef2a. Thus, ET-1 receptor antagonism with macitentan decreased cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting mef2a (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Pretreatment with macitentan (MACI 10 μmol/L) prevented hypertrophy in cardiac myocytes via myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2). A, Adult rat ventricular cardiac myocyte (ARVM) relative size and representative microscopic images (×10). B, Relative mRNA expression of hypertrophic signaling pathway markers: gata4, mef2a, mef2c, myocardin, and nfat. Histogram bars represent the mean±SEM of n=4 to 6 experiments. C, Simplified diagram of the proposed mechanism of action of MACI on the regulation of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. ALDO indicates aldosterone (1 μmol/L); and CT, control.

ET-1 Antagonism Improves Molecular Markers of Cardiac Remodeling in HFpEF Mice

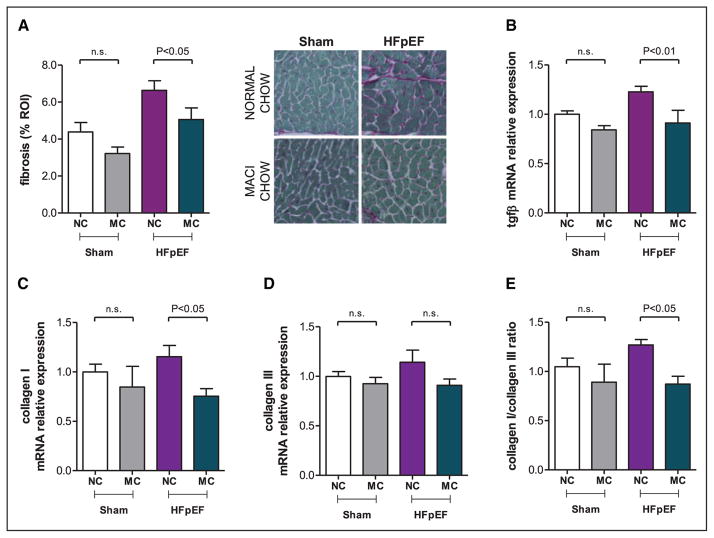

We next examined the effect of dual ET-A/ET-B receptor antagonism on HFpEF-induced cardiac fibrosis. Cardiac collagen content, increased in HFpEF mice compared with Sham (6.63±0.52 versus 4.39±0.51%; P<0.05) and decreased in HFpEF-MACI mice (5.06±0.62%; P<0.05; Figure 4A). This was associated with the following molecular changes. Transformimg growth factor-β and collagen type-I mRNA levels in the LV of HFpEF mice were significantly increased, and macitentan normalized the relative expression of both markers (P<0.05 for all; Figure 4B and 4C). There were no changes in collagen type-III expression (Figure 4D). Therefore in HFpEF, the stiffer collagen I was increased over the more compliant collagen III. The resultant collagen I:collagen III ratio was increased in HFpEF mice (P<0.05 versus Sham). Noticeably, macitentan decreased the stiffer collagen I without any effect on the more compliant collagen III (P<0.05 versus HFpEF; Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Pharmacological inhibition of endothelin (ET)-1 reduces cardiac fibrosis and stiffness in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) mice. Fibrosis quantification of pricosirius red staining and representative microscopic images (×20; A), and relative mRNA expression of tgfβ (B), collagen 1 (C) and collagen 3 (D), and collagen 1:collagen 3 ratio (E) in left ventricular tissue of Sham and HFpEF mice fed a normal chow (NC) or treated with macitentan (MC; 30 mg/kg per day) for 2 weeks. n=5 to 10 mice per group. Data shown as mean±SEM. MACI indicates macitentan; n.s., not significant; and ROI, regions of interest.

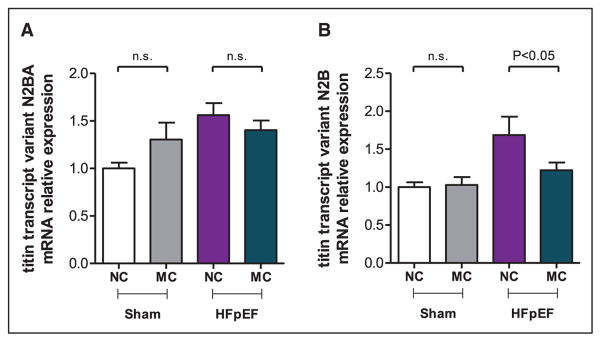

Titin, a large, multifunctional filament, traverses half of the cardiomyocyte sarcomere. Two titin isoforms exist, the more compliant (N2BA) and the stiffer isoform (N2B), and both play a pivotal role in diastolic stiffness and in HFpEF.5,6 Thus, we measured the expression of the titin transcript variants n2ba and n2b from the LV of HFpEF mice treated with or without macitentan. Both titin isoforms, n2ba and n2b, were significantly increased 1.56- and 1.68-fold, respectively, in HFpEF (P<0.05; versus Sham). Macitentan treatment only reduced the expression of the stiffer titin isoform, n2b, by 38±10% versus HFpEF (P<0.05, Figure 5A and 5B). Moreover, these changes in n2b expression showed a positive correlation with the changes observed in collagen I expression (R=0.648; P<0.001; Figure III in the Data Supplement).

Figure 5.

Effect of pharmacological inhibition of endothelin (ET)-1 in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) mice. Relative mRNA expression of titin transcription variant n2ba (A) and n2b (B) in the left ventricle of Sham and HFpEF mice fed a normal chow (NC) or treated with macitentan (MC; 30 mg/kg per day) for 2 weeks. n=5 to 10 mice per group. Data shown as mean±SEM. n.s. indicates not significant.

Discussion

ET-1 levels are elevated and predict mortality in HFrEF8; yet, human studies with ET-1 inhibition showed no clinical benefit. Recently, ET-1 levels were also shown to be elevated in HFpEF patients with diabetes mellitus19 and selective inhibition of the ET-A receptor with sitaxsentan in HFpEF improved only exercise tolerance with negligible effects on LV structure and impaired diastolic function.20 In the present study, ET-1 levels are elevated in patients with stable, chronic HFpEF. In addition, these patients demonstrated increased cardiac hypertrophy. Noticeably, circulating ET-1 levels were also elevated in a subgroup that included only patients with hypertension-associated HFpEF patients, thus supporting the relevance of the experimental findings in this specific HFpEF murine phenotype.

Chronic treatment with macitentan, a dual ET-A/ET-B receptor antagonist, reduced cardiac hypertrophy in experimental HFpEF. These novel findings were independent of changes in BP. Chronic macitentan therapy (1) reduced wall thickness and decreased heart weight in HFpEF and (2) reduced cardiomyocyte size and transcript expression of myocardial brain natriuretic peptide. In vitro findings showed that this reduction in cardiac hypertrophy is associated with an inhibition of mef2a expression. Macitentan also decreased LV collagen content and the expression of the titin transcript variant n2b in mice with HFpEF. These data indicate that modulation of cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling by a dual ET-A/ET-B receptor antagonist may thus have a beneficial effect on the HFpEF phenotype.

The finding that selective inhibition of the ET-A receptor with sitaxsentan in HFpEF did not modify LV structure or improve impaired diastolic function20 was unexpected given that contractile dysfunction and the prohypertrophic effects of ET-1 are believed to be mediated principally through the ET-A receptor.21 Our findings suggest that blockade of both ET-A and ET-B receptors likely provides a more beneficial effect in HFpEF at a functional, structural, and cellular levels.

As previously reported, chronic aldosterone infusion caused HFpEF and moderate hypertension in mice, with LVH, pulmonary congestion and echocardiographic evidence of DD while maintaining a preserved EF.7,13 This model displays impaired hemodynamics, which is seen in the HFpEF phenotype with impaired LV relaxation, increased LV end-diastolic pressure, and increased τ.22 Treatment with a dual ET-A/ET-B receptor antagonist for 2 weeks caused regression of LVH but had no effect on DD in HFpEF mice and importantly, in the doses used, did not reduce hypertension indicating that the reduction in LVH was independent of changes in BP. Moreover, the effect of macitentan on LVH is consistent with previous studies, which showed that ET-1 system blockade protected against the development of cardiac hypertrophy without changes in BP.23

Under conditions such as ischemia, hypoxia, or HF, the heart undergoes pathological remodeling and LVH, associated with fibrosis and impaired contractile performance, leading to maladaptive hypertrophy and potentially HF. Supporting this notion, ET-1 production/secretion is stimuli responsive and contributes to both normal adaptive physiological and pathophysiological responses. On the one hand, physiological ET-1 production results in stretch-induced enhancement of contractility,24 whereas persistent ET-1 production results in maladaptive hypertrophy.25

Cardiomyocytes stimulated with aldosterone increased the expression of prepro–ET-1 mRNA, which was unaffected by pretreatment with macitentan. However, macitentan prevented cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, indicating that, at least partially, dual ET-A/ET-B receptor antagonism inhibited aldosterone-induced hypertrophy. Thus, it is likely that there is cross talk between ET-1 and aldosterone because the activation/inhibition of one system seems to modify levels of the other. This is also supported by clinical evidence, showing that hyperal-dosteronism is associated with increased ET-1 production26 and treatment in patients with HF with a dual ET-1 receptor antagonist decreased circulating aldosterone concentrations.27

Reprograming of the gene expression profile is responsible for many of the phenotypic changes observed in hypertrophied cardiomyocytes, and it is perceived to be critical for disease-associated impairment of cardiac myocyte function.28 Thus, we sought to investigate the potential mechanisms implicated in the reduction of hypertrophy by macitentan in cardiomyocytes. In our study, aldosterone stimulation of cardiomyocytes increased mef2a expression, which in turn was inhibited by pretreatment with macitentan. This suggests that mef2a plays a pivotal role in aldosterone-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Interestingly there were no changes in gata4, myocardin, mef2c, or nfat expression.

Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in HFpEF is often accompanied by increased fibrosis in the myocardium that leads to alterations in myocardial stiffness. The extracellular matrix, namely the collagen network, and cardiomyocytes, in which titin plays a key regulatory role, regulate myocardial stiffness.5 Collagen I (the stiffer isoform) and cross-linked collagen affect collagen solubility and content, extracellular matrix deposition, and thus myocardial stiffness.29 In cardiomyocytes, titin operates as a bidirectional spring that gives stability to the other myofilaments and is able to modulate cardiomyocyte-based stiffness, by switching isoforms, and undergoes post-translational modification by phosphorylation and oxidation.30 In this study, collagen synthesis and extracellular matrix deposition were increased in HFpEF hearts. This was also accompanied by changes in the expression of the titin variant isoforms n2ba and n2b. Macitentan treatment reduced cardiac collagen I and extracellular matrix deposition in mice with HFpEF. This is consistent with previous findings where elevated levels of ET-1 caused fibroblasts to proliferate and increase the secretion of extracellular matrix proteins.31 In human fibroblasts, dual ET-1 receptor blockade prevented the induction by tgfβ transcripts involved in tissue remodeling.31,32 Similarly, our results showed a reduction of tgfβ expression in the LV of HFpEF mice treated with macitentan, indicating that the modulation of fibrosis is through a tgfβ-depending mechanism. Moreover, although both titin isoforms were increased in the LV of HFpEF mice, only the variant isoform n2b (the stiffer isoform) was diminished in HFpEF mice treated with macitentan. Collagen content and titin isoforms have been shown to inversely proportional to preserve relative stiffness contributions, with lower sarcomere length (titin) present at higher length (collagen).33 In our study, collagen I mRNA expression and titin variant isoform n2b showed a positive correlation. Thus, given the generally coordinated expression of the stiffer titin isoform with fibrosis, it is likely that changes in remodeling and stiffness after macitentan treatment were temporally associated. However, the mechanisms leading to the observed changes were not investigated, limiting the interpretation of these results.

Limitations

The reduction in lung congestion suggests an improvement in DD. However, only E/A, deceleration time, and isovolumetric relaxation time were measured and were no different between HFpEF and HFpEF-MACI. e′ velocity or E/e′ ratio was not determined in this study. It is also possible that if therapy with macitentan was given for a longer duration, the reduction in LVH might precede changes in DD. However, other studies have shown that LVH reduction is not always accompanied by improvement in parameters of DD,34 and conversely, improvement in DD parameters is not consistently accompanied by LVH regression.7 The underlying pathogenic mechanism(s) that may link LVH to DD and HFpEF are not completely understood and is unlikely to be simply temporally related and will require further study.

Control subjects in this study were matched by age and gender and not comorbidities because of the small sample size. However, serum ET-1 levels were elevated both in the group of chronic stable HFpEF patients (similar to other HFpEF cohorts19,35), as well as in the subgroup that had specifically hypertension-associated HFpEF.

In conclusion, given the lack of therapies that continues to plague patients with HFpEF, understanding the mechanisms primarily responsible for this clinical syndrome is important. Our findings indicate that dual ET-A/ET-B receptor blockade modulates morphological and cellular changes associated with cardiac hypertrophy and the giant myocyte protein, titin, in HFpEF. Additional studies are warranted to determine whether regression of cardiac hypertrophy and improvement in cardiac stiffness observed in a murine model of HFpEF is likely to be beneficial in humans with HFpEF.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

Despite the increasing prevalence of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and the escalating burden on healthcare costs, therapy for HFpEF has been plagued by continued negative/neutral clinical trials. Therefore, discerning the mechanistic underpinnings, which play a role in the pathogenesis of HFpEF, is a priority. The present study provides new insights into the mechanisms of cardiac hypertrophy and adverse cardiac remodeling in HFpEF and suggests a therapeutic target for pathological cardiac hypertrophy in HFpEF. In this study, circulating levels of endothelin-1 (ET-1) were elevated in patients with HFpEF. In a murine model of HFpEF, which features most of the characteristics of human HFpEF, dual ET-A/ET-B receptor inhibition modulated cardiac hypertrophy and adverse cardiac remodeling, independent of changes in blood pressure. In concert with these structural alterations, there was a reduction in cardiomyocyte size and decreased brain natriuretic peptide expression in the heart, potentially via the regulation of mef2a. ET-A/ET-B receptor blockade also decreased collagen content and the expression of the stiffer titin transcript variant, n2b, in the left ventricle. Given the lack of therapy to reduce morbidity or mortality in patients with HFpEF, these data provide novel insights. Additional studies are warranted to determine whether combined ET-A/ET-B receptor blockade will have a favorable outcome in clinical HFpEF particularly since ET-inhibition has had no role in patients with HF with reduced EF.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by an investigator-initiated grant from Actelion awarded to Dr Sam.

Footnotes

The Data Supplement is available at http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003381/-/DC1.

Disclosures

Dr Iglarz is an employee of Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Allschwil, Switzerland. The other authors report no conflicts.

References

- 1.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gomez-Sanchez MA, Jaarsma T, Køber L, Lip GY, Maggioni AP, Parkhomenko A, Pieske BM, Popescu BA, Rønnevik PK, Rutten FH, Schwitter J, Seferovic P, Stepinska J, Trindade PT, Voors AA, Zannad F, Zeiher A ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–1847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borlaug BA, Paulus WJ. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:670–679. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:1810–1852. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Writing Group Members; Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Ikonomidis JS, Stroud RE, Nietert PJ, Bradshaw AD, Slater R, Palmer BM, Van Buren P, Meyer M, Redfield MM, Bull DA, Granzier HL, LeWinter MM. Myocardial stiffness in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: contributions of collagen and titin. Circulation. 2015;131:1247–1259. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamdani N, Paulus WJ. Myocardial titin and collagen in cardiac diastolic dysfunction: partners in crime. Circulation. 2013;128:5–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson RM, De Silva DS, Sato K, Izumiya Y, Sam F. Effects of fixed-dose isosorbide dinitrate/hydralazine on diastolic function and exercise capacity in hypertension-induced diastolic heart failure. Hypertension. 2009;54:583–590. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.134932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMurray JJ, Ray SG, Abdullah I, Dargie HJ, Morton JJ. Plasma endothelin in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1992;85:1374–1379. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.4.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohan DE, Rossi NF, Inscho EW, Pollock DM. Regulation of blood pressure and salt homeostasis by endothelin. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1–77. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00060.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yorikane R, Sakai S, Miyauchi T, Sakurai T, Sugishita Y, Goto K. Increased production of endothelin-1 in the hypertrophied rat heart due to pressure overload. FEBS Lett. 1993;332:31–34. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80476-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sam F, Duhaney TA, Sato K, Wilson RM, Ohashi K, Sono-Romanelli S, Higuchi A, De Silva DS, Qin F, Walsh K, Ouchi N. Adiponectin deficiency, diastolic dysfunction, and diastolic heart failure. Endocrinology. 2010;151:322–331. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka K, Wilson RM, Essick EE, Duffen JL, Scherer PE, Ouchi N, Sam F. Effects of adiponectin on calcium-handling proteins in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:976–985. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valero-Muñoz M, Li S, Wilson RM, Hulsmans M, Aprahamian T, Fuster JJ, Nahrendorf M, Scherer PE, Sam F. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction induces beiging in adipose tissue. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:e002724. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rude MK, Duhaney TA, Kuster GM, Judge S, Heo J, Colucci WS, Siwik DA, Sam F. Aldosterone stimulates matrix metalloproteinases and reactive oxygen species in adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes. Hypertension. 2005;46:555–561. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000176236.55322.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Essick EE, Ouchi N, Wilson RM, Ohashi K, Ghobrial J, Shibata R, Pimentel DR, Sam F. Adiponectin mediates cardioprotection in oxidative stress-induced cardiac myocyte remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H984–H993. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00428.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA, Rosen B, Hay I, Ferruci L, Morell CH, Lakatta EG, Najjar SS, Kass DA. Cardiovascular features of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction versus nonfailing hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy in the urban Baltimore community: the role of atrial remodeling/dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melenovsky V, Hwang SJ, Lin G, Redfield MM, Borlaug BA. Right heart dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3452–3462. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doi T, Sakoda T, Akagami T, Naka T, Mori Y, Tsujino T, Masuyama T, Ohyanagi M. Aldosterone induces interleukin-18 through endothelin-1, angiotensin II, Rho/Rho-kinase, and PPARs in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1279–H1287. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00148.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindman BR, Dávila-Román VG, Mann DL, McNulty S, Semigran MJ, Lewis GD, de las Fuentes L, Joseph SM, Vader J, Hernandez AF, Redfield MM. Cardiovascular phenotype in HFpEF patients with or without diabetes: a RELAX trial ancillary study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:541–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zile MR, Bourge RC, Redfield MM, Zhou D, Baicu CF, Little WC. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sitaxsentan to improve impaired exercise tolerance in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulder P, Richard V, Bouchart F, Derumeaux G, Münter K, Thuillez C. Selective ETA receptor blockade prevents left ventricular remodeling and deterioration of cardiac function in experimental heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;39:600–608. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia AG, Wilson RM, Heo J, Murthy NR, Baid S, Ouchi N, Sam F. Interferon-γ ablation exacerbates myocardial hypertrophy in diastolic heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H587–H596. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00298.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothermund L, Vetter R, Dieterich M, Kossmehl P, Gögebakan O, Yagil C, Yagil Y, Kreutz R. Endothelin-A receptor blockade prevents left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction in salt-sensitive experimental hypertension. Circulation. 2002;106:2305–2308. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038703.78148.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pikkarainen S, Tokola H, Kerkelä R, Ilves M, Mäkinen M, Orzechowski HD, Paul M, Vuolteenaho O, Ruskoaho H. Inverse regulation of prepro-endothelin-1 and endothelin-converting enzyme-1beta genes in cardiac cells by mechanical load. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1639–R1645. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00559.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamazaki T, Komuro I, Kudoh S, Zou Y, Shiojima I, Hiroi Y, Mizuno T, Maemura K, Kurihara H, Aikawa R, Takano H, Yazaki Y. Endothelin-1 is involved in mechanical stress-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3221–3228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Letizia C, De Toma G, Cerci S, Scuro L, De Ciocchis A, D’Ambrosio C, Massa R, Cavallaro A, Scavo D. Plasma endothelin-1 levels in patients with aldosterone-producing adenoma and pheochromocytoma. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1996;18:921–931. doi: 10.3109/10641969609097908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sütsch G, Bertel O, Rickenbacher P, Clozel M, Yandle TG, Nicholls MG, Kiowski W. Regulation of aldosterone secretion in patients with chronic congestive heart failure by endothelins. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:973–976. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00912-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drawnel FM, Archer CR, Roderick HL. The role of the paracrine/autocrine mediator endothelin-1 in regulation of cardiac contractility and growth. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:296–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collier P, Watson CJ, van Es MH, Phelan D, McGorrian C, Tolan M, Ledwidge MT, McDonald KM, Baugh JA. Getting to the heart of cardiac remodeling; how collagen subtypes may contribute to phenotype. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linke WA, Hamdani N. Gigantic business: titin properties and function through thick and thin. Circ Res. 2014;114:1052–1068. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.301286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu SW, Howat SL, Renzoni EA, Holmes A, Pearson JD, Dashwood MR, Bou-Gharios G, Denton CP, du Bois RM, Black CM, Leask A, Abraham DJ. Endothelin-1 induces expression of matrix-associated genes in lung fibroblasts through MEK/ERK. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23098–23103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi-Wen X, Chen Y, Denton CP, Eastwood M, Renzoni EA, Bou-Gharios G, Pearson JD, Dashwood M, du Bois RM, Black CM, Leask A, Abraham DJ. Endothelin-1 promotes myofibroblast induction through the ETA receptor via a rac/phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathway and is essential for the enhanced contractile phenotype of fibrotic fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2707–2719. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Y, Cazorla O, Labeit D, Labeit S, Granzier H. Changes in titin and collagen underlie diastolic stiffness diversity of cardiac muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:2151–2162. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barron AJ, Hughes AD, Sharp A, Baksi AJ, Surendran P, Jabbour RJ, Stanton A, Poulter N, Fitzgerald D, Sever P, O’Brien E, Thom S, Mayet J ASCOT Investigators. Long-term antihypertensive treatment fails to improve E/e′ despite regression of left ventricular mass: an Anglo-Scandinavian cardiac outcomes trial substudy. Hypertension. 2014;63:252–258. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zakeri R, Borlaug BA, McNulty SE, Mohammed SF, Lewis GD, Semigran MJ, Deswal A, LeWinter M, Hernandez AF, Braunwald E, Redfield MM. Impact of atrial fibrillation on exercise capacity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a RELAX trial ancillary study. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:123–130. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.