Short abstract

Recent NHS reforms give doctors increased responsibility for efficient and fair use of resources. Programme budgeting and marginal analysis is one way to ensure the views of all stakeholders are properly represented

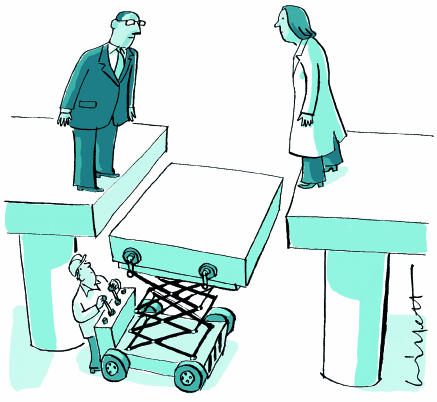

Tensions between doctors and managers and the differences between medical and managerial cultures have existed since the earliest provision of organised health care.1 In a resource allocation context, doctors are caricatured as taking the role of patient advocate while managers take the corporate, strategic view. Delivery of efficient (and in the case of the NHS, equitable) health care requires doctors to take responsibility for resources and to consider the needs of populations while managers need to become more outcome and patient centred. One economic approach, called programme budgeting and marginal analysis, has the potential to align the goals of doctors and managers and create common ground between them. We describe how the approach works and why it should be more widely used.

Economic principles

Programme budgeting and marginal analysis is an approach to commissioning and redesign of services that can accommodate both medical and managerial cultures and the widest constituency of professional, patient, and public values within a single decision making framework. It allows for the complexities of health care while adhering to the two key economic concepts of opportunity cost and the margin. When having to make choices within limited resources, certain opportunities will be taken up while others must be forgone. The benefits associated with forgone opportunities are opportunity costs. Thus, we need to know the costs and benefits of various healthcare activities, and this is best examined at the margin—that is, the benefit gained from an extra unit of resources or benefit lost from having one unit less. If the marginal benefit per pound spent from programme A is greater than that for B, resources should be taken from B and given to A.

Figure 1.

This process of reallocation should continue until the ratios of marginal benefit to marginal cost for the programmes are equal, maximising total patient benefit across the two programmes. The opportunity cost of funding one more hip replacement, for example, could be the benefit forgone by not using that resource to fund renal dialysis. Thus, the application of economics becomes about the balance of services, not introduction or elimination of services. Such marginal analysis is central in making the most of resources available.

Five questions

The approach starts by examining how resources are currently spent before focusing on benefits and costs of changes to the spending pattern.2 It can be used at micro levels (within programmes of care) or at a macro level (across services and programmes within a single health organisation). At its core, the approach can be operationalised by asking five questions about resource use (box 1).

The first two questions relate to programme budgeting, and the other three to marginal analysis. The underlying premise of programme budgeting is that we cannot know where we are going if we do not know where we are. All primary care trusts now have to collect programme budgeting information as part of the statutory accounts process. What they are not yet required to do is proceed with the marginal analysis.

An advisory panel is usually formed to examine the costs and benefits of proposed changes in services and use this information to improve benefit overall. The panel is charged with making recommendations in line with predefined criteria.

Box 1: Five questions about resource use

What are the total resources available?

On which services are these resources currently spent?

What services are candidates for receiving more or new resources (and what are the costs and potential benefits of putting resources into such growth areas)?

Can any existing services be provided as effectively, but with fewer resources, so releasing resources to fund items on the growth list?

If some growth areas still cannot be funded, are there any services which should receive fewer resources, or even be stopped, because greater benefit would be reached by funding the growth option as opposed to the existing service?

If the budget is fixed, opportunity cost is accounted for by recognising that the items for service growth can be funded only by taking resources from elsewhere. Resources can be obtained from elsewhere by being more technically efficient (changing practice to achieve the same health outcome at less cost) or more allocatively efficient (treating entirely different conditions to achieve a greater health outcome at the same cost). The analysis can be done at the margin by considering the amounts of different services provided. Although in reality quantitative data on marginal benefits are often lacking, it is the way of thinking underpinning the framework that is important.

Of course, governments tend to add real resources to health organisation budgets each year. But the increased funds are unlikely to cover all proposed growth areas. Scarcity still exists, and the principles of programme budgeting and marginal analysis still apply. In effect, although sounding extreme, the whole budget is available for consideration for re-allocation.

Who decides and how?

Careful consideration must be given to the make up of the advisory panel and to the various stakeholder groups whose views and advice will be sought. The key is to obtain representation3-5 without rendering the process unmanageable.6 The composition of the panel will depend on the questions under consideration and the scope of the exercise, but it is likely to comprise a mix of clinical staff and managers and perhaps patients or members of the public. Information analysts and financial staff are also key resources to provide support.

Whenever possible, local knowledge should be supplemented with evidence from sources such as economic evaluations, effectiveness studies, needs assessments, national and local policy documents, and surveys of healthcare professionals and the public.5,6 In the end, however, it is the members of the advisory panel who decide whether to recommend that resources should be shifted. When evidence is lacking, group members may base recommendations on their expert opinion.7

It is also important to conduct a final round of consultations with a wider group of relevant stakeholders. This tests the validity of the recommendations and makes it more likely that they will be accepted. Box 2 outlines the formal stages of the process. A practical toolkit is now available describing these stages in more detail.8

Barriers to use

Although programme budgeting and marginal analysis is not without challenges,9 the framework has been used in over 60 health organisations in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United Kingdom. A systematic review showed that use was sustained in over half of the 80 cases where the approach has been implemented. Given this, it is hard to understand why greater use has not occurred, particularly in bodies like NHS primary care trusts. Perhaps its use has been discouraged by the poor uptake of results of traditional economic evaluations at the local level in the NHS.10 However, programme budgeting and marginal analysis is different from economic evaluation. Although based on the same principles, it uses these principles to create a management process into which results from standard economic evaluations and other evidence can be incorporated. Indeed, such a process could be seen as the missing piece in the jigsaw of reform, providing defensible mechanisms to help primary care trusts remain within budget while prioritising between national guidance and local needs.

The approach requires an acceptance of resource scarcity and the need to manage it. Another important barrier to its effective use may stem from reluctance by doctors to accept loss of funding if their services are judged to have lower marginal benefit. Financial incentives, whereby clinicians are empowered to reinvest a portion of resources released directly back into their services, have been shown to encourage participation.4

Box 2: Seven stages in setting priorities

Determine the aim and scope of the exercise

Compile a programme budget (map of current activity and expenditure)

Form marginal analysis advisory panel and stakeholder advisory groups

Determine locally relevant decision making criteria with input from decision makers and stakeholders (eg service providers, patients, public)

Advisory panel identifies options in terms of: Areas for service growth Areas for resource release through producing same level of output (or outcomes) but with fewer resources Areas for resource release through scaling back or stopping some services

Advisory panel makes recommendations in terms of: Funding growth areas with new resources Decisions to move resources released through increased productivity to areas of growth Trade-off decisions to move resources from one service to another if relative value is deemed greater

Validity checks with additional stakeholders and final decisions to inform budget planning process

Improving the doctor-manager relationship

A successful partnership between medicine and management is widely believed to require joint leadership and alignment of goals.11,12 To accomplish a convergence of cultures Ham suggests we need to “Harness the energies of clinicians and reformers in the quest for improvements in performance that benefit patients.”11 The programme budgeting and marginal analysis process has the potential to do this, providing a practical framework to facilitate joint working in several ways.

The approach requires and values equally the contributions of doctors and managers. For example, different models of medical practice1 each play a legitimate part at different stages in the process. A reflective model, drawing on tacit knowledge borne of individual clinical experience, is invaluable in formulating the criteria for assessing candidates for increased and decreased funding, to identify these candidates, and to assess subjectively the benefits gained or lost from proposed shifts in resource allocation. At the same time, doctors bring essential critical appraisal skills to the evaluation of investment and disinvestment options and for integration of clinical evidence from systematic reviews. Managers, in addition to providing more obvious organisational, operational, financial, and strategic management skills, can ensure success at critical stages of the process through cooperation, negotiation, delegation, teamwork, and persuasion.12 Managers will also ensure that the local and national policies exert an appropriate level of influence on final priorities. Consideration of policies is no less important than clinical evidence if the process is to lead to real change in delivery of services.

Other advantages of programme budgeting and marginal analysis include transparency and inclusivity. Contextual information, evidence, and subjective judgment are explicitly presented, evaluated, and recorded. This makes it more difficult for any professional group to defend (or reject) a stance simply through obfuscation or unsubstantiated assertion. It is also likely to minimise legal intrusion into public policy making.13 In addition, the perspectives of doctors and managers are both mediated and illuminated by a range of other viewpoints garnered from patient, public, and professional groups.

Perhaps the most important benefits for the doctor-manager relationship would come through interdisciplinary education. Joint participation at each stage of the process has the potential to lead to a shared understanding of each other's cultures. The net result may be a shared appreciation of opportunity cost, the need to focus on resources and health outcomes and to balance clinical autonomy with financial responsibility. Sustainable publicly funded healthcare systems depend on a mature recognition of the need to manage scarcity. Programme budgeting and marginal analysis can help achieve this precisely because it bridges clinical and strategic decision making.

Summary points

Programme budgeting and marginal analysis has the potential to align the goals of doctors and managers

It is an economic approach to priority setting that adheres to the two key economic concepts of opportunity cost and the margin

The method requires and values equally the contributions of doctors and managers

Contextual information, evidence, and subjective judgment are explicitly presented, evaluated, and recorded

The approach fosters a shared appreciation of the need to focus on resources and health outcomes and the need to balance clinical autonomy with financial responsibility

Contributors and sources: CD is an experienced health economist with a long research interest in priority setting. DR and CM have extensive experience implementing programme budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA) as health services researchers. Both CD and CM have recently completed a major review of PBMA studies over the last 25 years. This article is a synthesis of their personal experiences, the results of the review, and the preliminary findings of a PhD study by AB.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Davies HT, Harrison S. Trends in doctor-manager relationships. BMJ 2003;326: 646-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donaldson C, Farrar S. Needs assessment: developing an economic approach. Health Policy 1993;25: 95-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen D. Marginal analysis in practice: an alternative to needs assessment for contracting health care. BMJ 1994;309: 781-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lockett T, Rafferty J, Richards J. The strengths and limitations of programme budgeting. In: Lockett T, ed. Priority setting in action. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1995.

- 5.Ruta DA, Donaldson C, Gilray I. Economics, public health and health care purchasing: the Tayside experience of programme budgeting and marginal analysis. J Health Services Res Policy 1996;1: 185-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig N, Parkin D, Gerard K. Clearing the fog on the Tyne: programme budgeting in Newcastle and North Tyneside Health Authority. Health Policy 1995;33: 107-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peacock S. Program budgeting and marginal analysis: options for health sector reform. Melbourne: Centre for Health Program Evaluation, Monash University, 1997.

- 8.Donaldson C, Mitton C. Priority setting toolkit: a guide to the use of economics in health care decision making. London: BMJ Books, 2004.

- 9.Mitton C, Peacock S, Donaldson C, Bate A. Using PBMA in health care priority setting: description, challenges and experience. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2003;2: 121-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonald R. Using health economics in health services: rationing rationally? Buckingham: Open University Press, 2002.

- 11.Ham C. Improving the performance of health services: the role of clinical leadership. Lancet 2003;361: 1978-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crosson FJ. Improving the doctor-manager relationship. Kaiser Permanente: a propensity for partnership. BMJ 2003;326: 654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greschner D, Lewis S. Autonomy and evidence-based decision-making: Medicare in the courts. Canadian Bar Rev 2003;82: 501-33. [Google Scholar]