Abstract

A dysfunction in the blood–brain barrier (BBB) is associated with many neurological and metabolic disorders. Although sex steroid hormones have been shown to impact vascular tone, endothelial function, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses, there are still no data on the role of testosterone in the regulation of BBB structure and function. In this context, we investigated the effects of gonadal testosterone depletion on the integrity of capillary BBB and the surrounding parenchyma in male mice. Our results show increased BBB permeability for different tracers and endogenous immunoglobulins in chronically testosterone-depleted male mice. These results were associated with disorganization of tight junction structures shown by electron tomography and a lower amount of tight junction proteins such as claudin-5 and ZO-1. BBB leakage was also accompanied by activation of astrocytes and microglia, and up-regulation of inflammatory molecules such as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF). Supplementation of castrated male mice with testosterone restored BBB selective permeability, tight junction integrity, and almost completely abrogated the inflammatory features. The present demonstration that testosterone transiently impacts cerebrovascular physiology in adult male mice should help gain new insights into neurological and metabolic diseases linked to hypogonadism in men of all ages.

Keywords: Blood–brain barrier, inflammation, mouse, testosterone, tight junction

Introduction

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is a physical and metabolic diffusion barrier, which is essential for the maintenance of homeostasis and normal central nervous system (CNS) function. The BBB is present throughout the brain, except in the circumventricular organs that regulate the autonomic nervous system.1 It acts as a selective and highly regulated interface between the circulatory system, and thus the immune system, and the brain parenchyma. The main BBB characteristic is its highly selective permeability, especially due to intercellular endothelial tight junctions (TJs), which control the passage of molecules between the brain parenchyma and the blood through the paracellular pathway (for reviews see Gumbiner2). This function protects the brain against potentially toxic xenobiotics, but also constitutes a major limitation to therapeutic treatment of the CNS.

The BBB represents a complex cellular system, not only consisting of brain endothelial cells with sparse transport vesicles sealed by TJs but also of pericytes, perivascular microglia, astrocytes end-feet, and basal lamina. While this particular cerebral endothelial cell layer forms the barrier proper, the interaction of all cells constituting the neurovascular unit is necessary for the induction and maintenance of specialized BBB functions. This interface is increasingly recognized as a dynamic system, capable of responding to local changes and requirements. Furthermore, it can be regulated via a number of mechanisms and cell types, not only in physiological but also in pathological conditions. A defect of BBB impermeability is a consequence of some acute disorders, such as stroke and traumatic brain injury, and is present in some chronic neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's dementia and Parkinson's disease.3,4 In other cases, BBB disruption may be a precipitating event, such as in multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, obesity, or diabetes.5,6

Population-based epidemiological studies showed that high levels of androgens increase the incidence of cerebrovascular disease in young adult men.7 The natural decline in physiological levels of circulating androgens also contributes to increased incidence and worsened outcome with aging.8 Deleterious and protective effects were also described for testosterone in rodent models of cerebral ischemia.9

Sex steroid hormone, beyond reproduction, is implicated in multiple brain functions including the BBB regulation and neuroprotection. At the cellular level, sex steroid hormones have been found to alter vascular tone, endothelial function, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses in rat cerebral vessels, irrespective of the sex, and in cultured endothelial cells (see for review, Krause et al.10). Earliest studies demonstrated the effects of estrogens on cerebral circulation in females, and their protective effects on endothelial function and peripheral vascular health in females (for review see, Pelligrino and Galea11). However, numerous studies describing these effects of estrogens in stroke prevention offer conflicting results in human and animal studies alike. Analysis of the literature suggests complex dose-dependent effects according to the experimental methods used (see for review, Strom et al.12). Evidences show that progesterone is also a strong neuroprotective compound in various models of brain injury and disease (see for review, Liu et al.13). More recent data show that combined administration of estrogen and progesterone in adult male rat soon after transient focal hypoxia leads to long-term neuroprotective effects.14 The prevalence of inflammatory cerebrovascular disease shows a distinct male predominance, with numerous studies demonstrating that women are relatively protected. In this context, the effects of testosterone on brain microvasculature, at both the cellular and molecular level, remains to be studied in detail. It has been shown that physiological levels of testosterone and its metabolite dihydrotestosterone (DHT) reduce infarct damage after middle cerebral artery occlusion in castrated mice,15 but, to our knowledge, no data are available yet in the literature about the role of testosterone on BBB structure and function in physiological conditions. Understanding BBB physiology is critical to gain new insights into neurological and metabolic diseases involving BBB dysfunction and for the development of drugs that can cross the BBB.

In the present study, we investigated the effects of gonadal testosterone on BBB function and integrity. To address this question, we analyzed a mouse model of testosterone chronic depletion using complementary approaches. We report that chronic depletion of testosterone for five weeks in young male mice led to BBB leakage as demonstrated by increased permeability to different tracers and ultrastructural studies using electron tomography. This involved altered expression of endothelial TJ components. BBB leakage was associated with glial activation and inflammatory processes. Interestingly, testosterone supplementation after five weeks of depletion could restore the majority of observed alterations.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

The experiments have been reported in compliance with the Animal Research: Reporting in Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

All studies were performed in agreement with the National Institute of Health guidelines for the care and use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Guide) and French and European legal requirements (Decree 2010/63/UE). Experiments were performed accordingly, to minimize animal number and discomfort and were approved by the “Comité d'éthique en expérimentation animale” Charles Darwin N°5 (project number 01490-01).

Study design

The present study aimed to analyze the role of testosterone on the integrity of the capillary BBB and surrounding parenchyma in male mice under physiological conditions. In particular, we investigated the effects of circulating testosterone depletion on BBB permeability and characterized its impact on TJ structure and protein levels, and distribution, and on their cellular partners. Analyses were processed using five-week castrated mice compared with intact age-matched male mice. To our knowledge, no study describes the role of testosterone on BBB structure and function. Since it is difficult to study all parts of the brain, we chose to focus on a highly sensitive brain area with respect to gonadal testosterone in the male, the medial preoptic area (MPOA). To evaluate whether the effects of testosterone depletion were permanent or reversible, five-week castrated males were supplemented with testosterone for 30 days and then compared to their intact littermates.

Animals

Littermate males of C57BL/6j strain from the breeding of laboratory, were housed in conventional facility after weaning under a controlled photoperiod (12:12h light dark cycle—lights on at 7 a.m.), maintained at 22 ℃ and fed a standard diet with free access to food and water. After surgery, mice were single-housed in order to avoid any effect of social stress.

Gonadectomy and testosterone supplementation

Half of adult male mice in each litter (eight weeks old, 20–25 g) were castrated under general anesthesia using a ketamine 100 mg/kg /xylazine 10 mg/kg mixture as previously described.16 The surgery lasted about 5–10 minutes per animal. As ketamine has been shown to increase cerebral blood flow and intracranial pressure,17 mice were given five weeks to recover from surgery and anesthesia. In addition, this ensures depletion of endogenous testosterone prior to any experiment. For testosterone supplementation, castrated mice were subcutaneously implanted five weeks later with SILASTIC® implants filled with 10 mg of testosterone as previously described,15 single-housed and analyzed four weeks later. To avoid any effect of social stress due to variations in testosterone levels, all studied males were single-housed.

BBB permeability assay

To assess the permeability of BBB, intact, castrated, and testosterone-supplemented mice (n = 3 per group) were injected with different molecular weight tracers: 4-kDa Evans Blue and 40-kDa horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Sigma Aldrich, France).

Evans Blue dye injection

A 2% Evans Blue solution (4 ml/kg) diluted in normal saline was i.p. injected in awake mice (n = 3 mice per group). Three hours after Evans blue injection, mice were transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline solution followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution diluted in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4. Brains were removed and 10 coronal sections (40 μm thick) included MPOA were obtained from each brain using a vibratome (Leica VT1000S). Sections were mounted on slides and co-stained to visualize blood vessels with anti-laminin primary antibody (1/100; Table 1) followed by 488-Alexa Fluor conjugated secondary antibody (1/1000, Invitrogen). To avoid spreading of Blue Evans dye and to promote optimal visualization of labeled fine structures, sections were quickly immersed in xylene and mounted on slides with hydrophobic mounting medium, by modification of the method previously described by Werner et al.,17 Then fluorescent staining was visualized under a confocal microscope.

Table 1.

List of primary antibodies.

| Antibody | Manufacturer | Catalog no. | Host | Application | Working dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFAP | Sigma Aldrich | G3893 | Mouse | WB/IHC | 1:500/1:400 |

| GFAP | DAKO | Z0334 | Rabbit | IHC | 1:500 |

| Laminin | Sigma Aldrich | L9393 | Rabbit | IHC | 1:100 |

| ZO 1 | Invitrogen | 61-7300 | Rabbit | WB/IHC | 1:500/1:250 |

| iNOS | Sigma | N9657 | Mouse | IHC | 1:1000 |

| iNOS | Santa Cruz | sc-7271 | Mouse | WB | 1:200 |

| GAPDH | Santa Cruz | sc-32233 | Mouse | WB | 1:10,000 |

| Claudin- 5 | Invitrogen | 34-1600 | Rabbit | WB/IHC | 1:500 |

| Occludin | Invitrogen | 40-4700 | Rabbit | WB | 1:500 |

| Iba-1 | Wako | 019-19741 | Rabbit | IHC | 1:1000 |

GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; WB: western blot; IHC: immunohistochemistry.

40-kDa HRP injection and transmission electron microscopy

10 µl of a 40-kDa HRP solution (10 mg/ml) was injected with a Hamilton syringe into the left ventricle of the heart of deeply anaesthetized mice (n = 3 mice per group). After 10 min of circulation, mice were transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline solution. Brains were removed and fixed in a 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution diluted in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer pH 7.4 overnight at 4 ℃. After washes in buffer, six coronal sections included MPOA (100-µm thickness) were processed from each brain in a standard 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma Aldrich) reaction. HRP activity was revealed by incubating the sections in 0.05 M Tris–HCl pH 7.6 buffer, containing 0.05% DAB and 0.006% H2O2 (Sigma Aldrich) for 15 min at room temperature (RT). The enzymatic reaction was stopped by transferring sections in 0.05 M Tris–HCl pH 7.6 buffer followed by several washes in phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Sections were then processed for transmission electron microscopy as described below.

HRP-labeled sections were post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) diluted in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 h, at RT and dehydrated through an alcohol ascending series and embedded in epoxy resin (Epoxy-Embedding Kit, Sigma Aldrich). MPOAs were selected and ultrathin sections (70 nm) were cut, collected on copper grids, stained with 2% uranyl acetate and Reynold's lead citrate, and then examined under a transmission electron microscope (80–120 kV 912 Omega ZEISS) equipped with a digital camera (Veleta Olympus).

Electron tomography and three-dimensional (3D) modelization

Electron tomography produces 3D reconstructions from sets of 2D projections acquired at different tilting angles in a transmission electron microscope.

Epon sections (200 nm thick) were cut (n = 3 per group, intact and castrated mice) using a Reichert Ultracut microtome (Leica Microsystems) and collected on formwar-coated copper/palladium grids (200 mesh) for analysis by electron tomography. Sections were randomly labeled on the two sides with protein A-gold 10 nm for use as fiducial markers during the subsequent alignment of the series of tilted images, and then contrasted with 2% uranyl acetate in water for 10 min and Reynold's lead citrate for 2 min.

Specimens were analyzed in a 200-kV transmission electron microscope Technai G2 Lab6 (FEI Company) equipped with a TemCam F-416 CMOS camera (TVISP GmbH) and a computerized goniometer. Once selected, images of capillary TJs were acquired at ×20.000 and tilted at 1 ° angular increment over a range of 120 ° (±60 °) about one orthogonal axis. Alignment of tilt series and tomogram computing were carried out by using the IMOD 4.7 program package. Manual contouring of the tomograms was performed by using the IMOD program. Finally, the contours were meshed and z scale was stretched with a factor of 1.6 to correct for resin shrinkage.

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry and Fluoro-Jade® C staining

Animals were deeply anaesthetized with a lethal dose of pentobarbital (25 mg/kg, i.p.) for the following procedures.

Tissue preparation

For TJ proteins (claudin-5, occludin and ZO-1), mice (n = 4 per group) were transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline solution and brains were quickly taken out, embedded in ice-cold Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) embedding medium (Tissue-Tek, Sakura, Villeneuve d'Ascq, France), frozen in isopentane (−50 ℃) and stored at −80 ℃ until sectioning. Eight serial frozen sections (20-µm thickness) included MPOA were cut and collected on slides, and were then fixed by immersion for 2 min at −20 ℃ in methanol/acetone (vol/vol). For the other proteins and Fluoro-Jade® C staining, animals (n = 5 per group) were transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline solution followed by 4% PFA solution diluted in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4. The brains were removed and post-fixed with the same fixation solution overnight at 4 ℃. After the post-fixation step, the brains were cryoprotected with a 20% sucrose solution for freezing in isopentane (−30 ℃) and then cut in 20 µm thickness sections using a cryostat.

Labeling procedure

Nonspecific sites were blocked by incubating slide-mounted sections in 0.1 M PBS pH 7.4, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.2% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. Then sections were incubated with one or more primary antibodies overnight at 4 ℃ diluted in the same PBS/BSA/Triton solution (Table 1). Immune complexes were revealed using secondary Alexa-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000; Invitrogen, France). Fluorescence was observed with a confocal microscope.

Fluoro-Jade® C staining of 20 µm-thick sections was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore, USA). Fluorescent staining was visualized under a confocal microscope.

Confocal microscopy

Simple and multiple fluorescent labeling were visualized with a SP5 upright Leica confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems) equipped with the Acousto-Optical Beam Splitter (AOBS) and using 20 × or 63 × oil immersion objectives. Alexa 488 was excited at 488 nm and observed from 495 to 580 nm; Alexa 555 was excited at 555 nm and observed from 599 to 680 nm. The gain and offset for each photomultiplier were adjusted to optimize detection events. Images (1024 × 1024 pixels, 16 bits) were acquired sequentially between stacks to eliminate cross-over fluorescence. The frequency was set up to 400 Hz and the pinhole was set to 1 Airy. Each optical section (0.5–1 μm) was frame-averaged four times to enhance the signal/noise ratio. Overlays and projection of the z-stack files were performed by using the Fiji software (NIH, USA). Presented pictures were the projection of 10–20 successive optical sections into one image.

Western blot protein analysis

Tissue preparation and protein extraction

Brains (n = 6 per group) were taken out and hypothalamus were quickly removed and placed on ice. Preparation of micro vessel-enriched fractions was performed by harvesting hypothalamic micro-vessels according to a method adapted from procedure described previously.18 Briefly, samples were homogenized in a pH 7.4 buffer containing 2.7 mM KCl, 137 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 6 H2O, 5 mM d-glucose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1 M 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), and 1% BSA. Homogenates were then centrifuged in an equal volume of 30% Ficoll for 15 min at 5800 g at 4 ℃, supernatants were aspirated, and pellets suspended in isolation buffer without BSA and passed through a 70-µm nylon filter. Filtrates were centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 g at 4 ℃, and then protein content was extracted from the pellets with RIPA buffer containing 50 mM Tris—base (pH 7.2), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.5% deoxycholate acid, 1% Triton X-100, and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich) and sonicated five times for 30 s.

Electrophoresis and immunoblotting

10–25 µg of proteins were subjected to electrophoresis on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis–Tris Gel (Invitrogen, France) or 7.5% and 10% polyacrylamide gels. The resolved proteins were electrotransfered onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, France). Membranes were blocked for 1 h, at RT with a solution of 5% nonfat milk–Tris-buffered saline (TBS, 20 mM Tris base, 137 mM NaCl, pH 7.6) with 0.1% Tween, and were incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with primary antibodies diluted in the same blocking solution (Table 1). Primary antibody binding to blots was detected by incubation with respective secondary HRP–conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse (1:5000; Jackson, France) for 1 h, at RT, and then, immune complexes were revealed by the SuperSignal™ West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate kit (Thermo Scientific, France). Signals were quantified by using FiJi software (NIH, USA) and normalized to the value obtained for the corresponding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) band.

Quantitative RT-PCR

To perform quantitative RT-PCR, castrated and intact mice (n = 5 per group) were used. Total RNA was extracted from hypothalamic micro vessel-enriched fractions using the RNeasy Plus Micro kit from Qiagen (Qiagen, France). RNA (250 ng per sample) was reverse transcribed using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany). Then, qPCR reactions were performed with primers previously described (a gift from S. Vyas)19,20 and SYBR Green Real-time PCR Master Mix (Thermofisher Scientific, France). Experiments were performed in triplicate for each sample to obtain an average cycle threshold (Ct) value. Transcript levels of each gene were normalized to the level of hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase 1 (HPRT), the endogenous reference gene chosen for its insignificant variation across experimental groups. Relative expression of each target gene was determined using the comparative Ct method.21

Statistical analysis

The two sample sizes corresponding to the intact and castrated group were equal. Normal distribution of the two groups was checked. The sample mean and standard deviation in each group, intact and castrated mice was determined, the standard deviation was approximately equal. Comparisons between intact and castrated mice of the two population means were performed using unpaired student's t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. In the text, data are expressed as a percentage difference between castrated and intact groups.

Results

For each experimental group, mice were healthy and no anomaly concerning the microbiological status was identified before sacrifice of the animals.

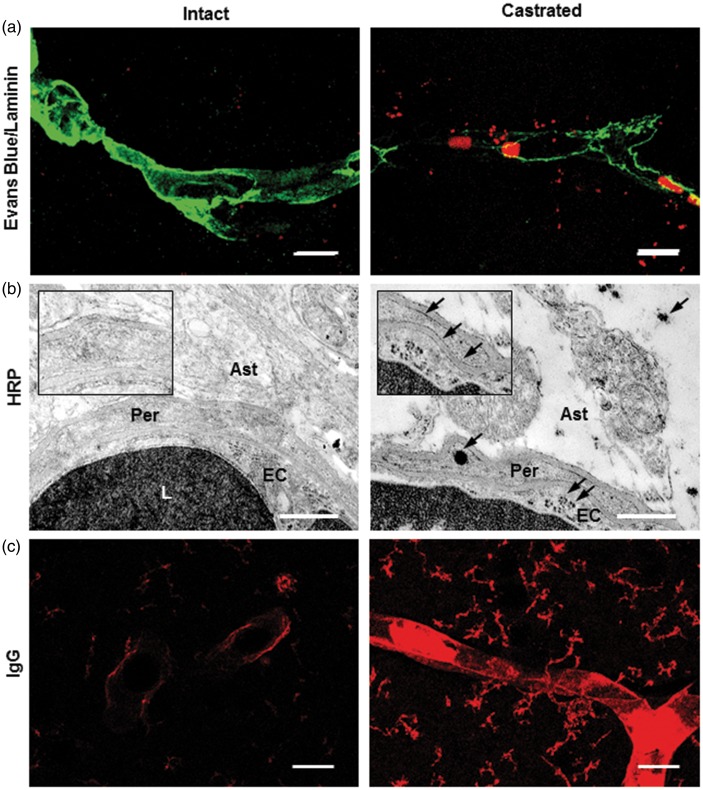

Depletion of gonadal testosterone-induced heightened permeability of BBB in the MPOA

BBB permeability was evaluated for different tracers such as Evans Blue dye, and Horse Radish Peroxidase (HRP) in intact and five-week castrated males. Confocal microscopy analysis suggested a slight extravasation of the Evans Blue dye outside perfused brain capillaries labeled by anti-laminin in castrated males. In contrast, it was almost absent in intact mice (Figure 1(a)). This qualitative observation was confirmed at the ultrastructural level, after administration of HRP. Some DAB precipitates were observed within the endothelial cell cytoplasm, reflecting the presence of exogenous–injected HRP enzyme. These were joined to the abluminal endothelial cell membrane, the basal lamina, and within perivascular astrocytic end-feet in castrated male mice (Figure 1(b)).

Figure 1.

Depletion of gonadal testosterone increased BBB permeability. (a) Representative images of Evans blue dye (red) in the MPOA of perfused intact (left panel) and castrated mice (right panel) where capillaries were labeled with anti-laminin (green; n = 3 per group). Scale bar: 10 µm. The fluorescent dye is slightly extravasated from capillaries. (b) Representative electron micrographs showing portion of capillaries located in the MPOA after parenteral injection of HRP solution in intact (left panel) and castrated mice (right panel). DAB precipitates are detected in the lumen of capillaries of both intact and castrated mice. In castrated males, they are also observed within the endothelial cell cytoplasm, joined to the abluminal endothelial cell membrane and the basal lamina, and within perivascular astrocytic end-feet (insert, arrows). Scale bar: 1 µm, n = 3 per group. (c) Representative images showing the presence of endogenous circulating IgG (red) in the MPOA of intact (left panel) and castrated mice (right panel). Scale bar: 40 µm, n = 5 per group. Ast: astrocyte end-foot; EC: endothelial cell; L: lumen; Per: pericytes.

BBB integrity was also considered using immuno-labeling of endogenous circulating IgG. Circulating IgG were observed (Figure 1(c)) in the capillary wall and cerebral parenchyma of perfused-castrated mice, whereas a very low labeling was detected in perfused-intact mice (+860%, 11.70 ± 1.86 mean gray value/µm2 in castrated mice vs. 1.36 ± 0.17 mean gray value/µm2 in intact mice, p ≤ 0.05).

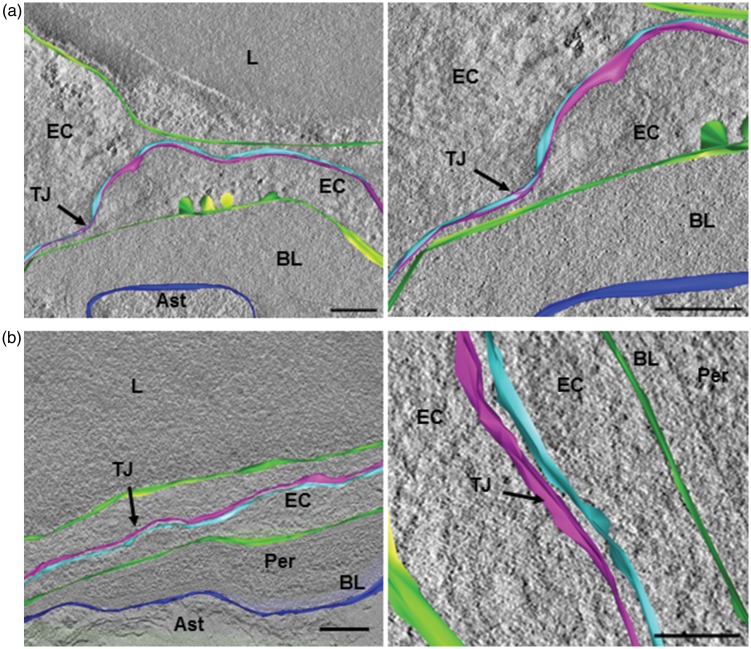

Castration induced-BBB leakage affects endothelial TJs

The relationship between structure and function of TJ was first assessed using 3D-ultrastructural analysis. Ultrastructural details of capillary endothelial TJs were examined by electron tomography with a 3D-reconstruction from electron microscopy projection images of resin-embedded thin sections (200 nm) of the hypothalamic MPOA. At the nanoscale, tomographic volumes from consecutive serial sections were stacked slice by slice. Such reconstruction allowed visualization of the morphological arrangements of capillary inter-endothelial TJs, as a TJ opening could be the cause of para-cellular transport of components. In intact male mice, TJs exhibited a series of discrete sites of apparent fusion, involving the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane (Figure 2(a) and SI movie S1). In contrast, in castrated mice, these closely associated membrane areas were never observed and large intercellular spaces were clearly highlighted (Figure 2(b) and SI movie S2).

Figure 2.

Depletion of gonadal testosterone affected endothelial tight junction morphology. (a, b) Three-dimensional model following electron tomographic reconstruction of capillary inter-endothelial tight junction. (a) Endothelial tight junction in cerebral capillaries of intact male mice, involving two adjacent plasma membranes (light blue and pink in the right panel). A series of discrete sites of apparent fusion involving the outer leaflet of the plasma membranes were observed (left panel and Movie S1). (b) Endothelial tight junction in cerebral capillaries of castrated male mice, involving two adjacent plasma membranes (light blue and pink in the right panel). Large intercellular spaces are observed (left panel and Movie S2). The luminal and abluminal membranes of the endothelial cell are in green. The limiting membrane of astrocyte end-foot contacting basal lamina surrounding capillary is in dark blue. Scale bar: 150 nm, n = 3 per group.

Ast: astrocyte end-foot; BL: basal lamina; EC: endothelial cell; L: lumen; TJ: tight junction; Per: pericyte.

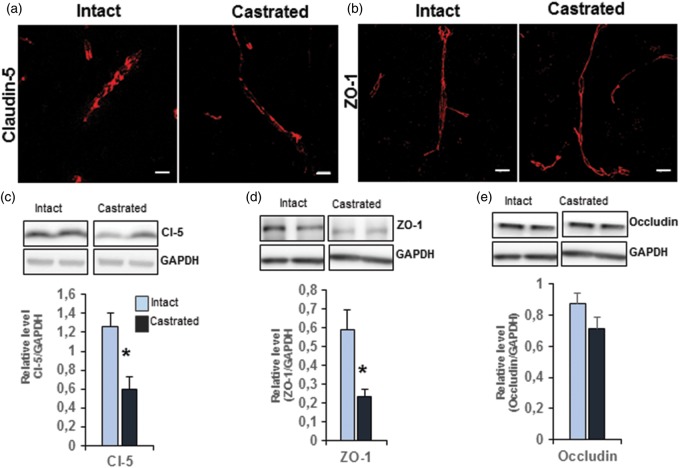

Tightly apposed–adjacent endothelial membranes comprise a complex of transmembrane proteins claudin-5 and occludin, which are associated with peripheral membrane proteins such as ZO-1. Immunofluorescence analysis showed no significant difference in the distribution of immuno-labeling for claudin-5 and ZO-1 in castrated males compared with age-matched intact mice (Figure 3(a,b)). We thus assessed the protein levels of these main TJ proteins by Western blot performed on microvessel-enriched fractions. Significantly less claudin-5 (−52.7% vs. intact, p ≤ 0.05) and ZO-1 (−59.7% vs. intact, p ≤ 0.05) were observed in capillaries of the MPOA of castrated mice compared to those of age-matched intact mice (Figure 3(c,d)). In contrast, no difference in the amount of occludin was detected between the two groups (Figure 3(e)).

Figure 3.

Depletion of gonadal testosterone affected endothelial tight junction proteins. (a) Representative images of capillaries located in the MPOA of intact mice (left panel) and castrated mice (right panel), labeled with anti-claudin-5 (red). Scale bar: 10 µm, n = 4 per group. (b) Representative images of capillaries located in the MPOA of control (left panel) and castrated mice (right panel), labeled with anti-ZO-1 (red). Scale bar: 10 µm, n = 4 per group. (c–e) Western blot analysis of tight junction proteins performed on microvessel-enriched fractions from castrated mice compared with age-matched intact mice, claudin-5 (c), ZO-1 (d), and occludin (e). Data were normalized to GAPDH level. Values represent means ± SEM of four to five mice per group. *p ≤ 0.05 by Student's t-test compared to the control group.

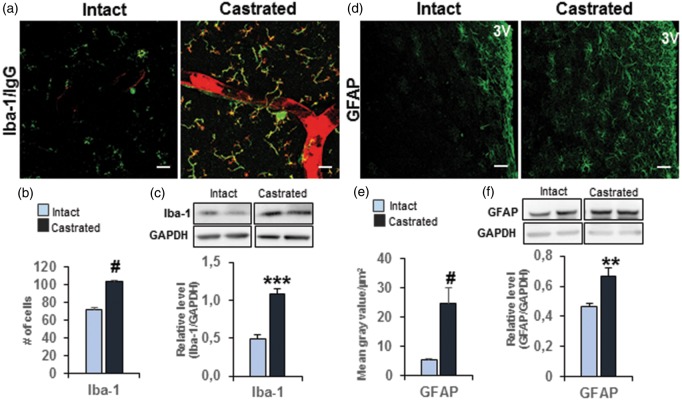

Castration-induced glial activation

As extravasated circulating IgG appeared to be associated with cells of the parenchyma, we focused on the identification of these cellular targets in the MPOA. Our results show that all extravasated IgG in castrated mice was co-labeled with Iba-1, a specific marker of microglial cells (Figure 4(a)). Interestingly, the number of these Iba-1-immunopositive cells was significantly higher in the MPOA of castrated mice than in age-matched intact mice (+43.8% vs. intact, p ≤ 0.0001; Figure 4(b)). In agreement with this result, Western blot analysis performed on microvessel-enriched fractions revealed a significant increase in the amount of Iba-1 protein in castrated males (+119.8 % vs. intact, p ≤ 0.001; Figure 4(c)). This activation was accompanied by a significant enhancement of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunofluorescence density in the MPOA (+362% vs. intact males, p ≤ 0.0001) (Figure 4(d,e)). Western blot analysis performed on microvessel-enriched fractions also showed a higher level of GFAP in castrated mice (+44.6% vs. intact males, p ≤ 0.01) than in age-matched intact litter-mates (Figure 4(f)).

Figure 4.

Depletion of gonadal testosterone–induced glial activation. (a) Representative images of co-immuno-detection of circulating IgG (red) and Iba-1 (green) in the MPOA of intact (left panel) and castrated mice (right panel). Scale bar = 40 µm, n = 5 per group. (b) Quantitative analysis of Iba-1-positive cells represented as the total number of labeled cells out of the eight serial sections for each brain examined. #p ≤ 0.0001 compared to the intact group (n = four to five mice per group). (c) Western blot analysis performed on microvessel-enriched fractions showing Iba-1 protein amounts in castrated mice compared with age-matched intact mice. Data were normalized to GAPDH level. Values represent means ± SEM of four to five mice per group. ***p ≤ 0.001 compared to the intact group. (d) Representative images of GFAP labeling (green) in the MPOA of intact (left panel) and castrated mice (right panel). Scale bar = 50 µm, n = 3 mice per group. 3V: third ventricle. (e) Quantitative analysis of GFAP labeling in the MPOA of castrated mice compared with intact mice. Values represent means gray values per µm2 ± SEM #p ≤ 0.0001 compared to the intact group (n = 3 mice per group). (f) Western blot analysis performed on microvessel-enriched fractions showing level of GFAP amount in castrated mice compared with age-matched intact mice. Data were normalized to GAPDH level. Values represent means ± SEM **p ≤ 0.01 compared to the intact group (n = 6 mice per group).

Castration-induced inflammatory molecules

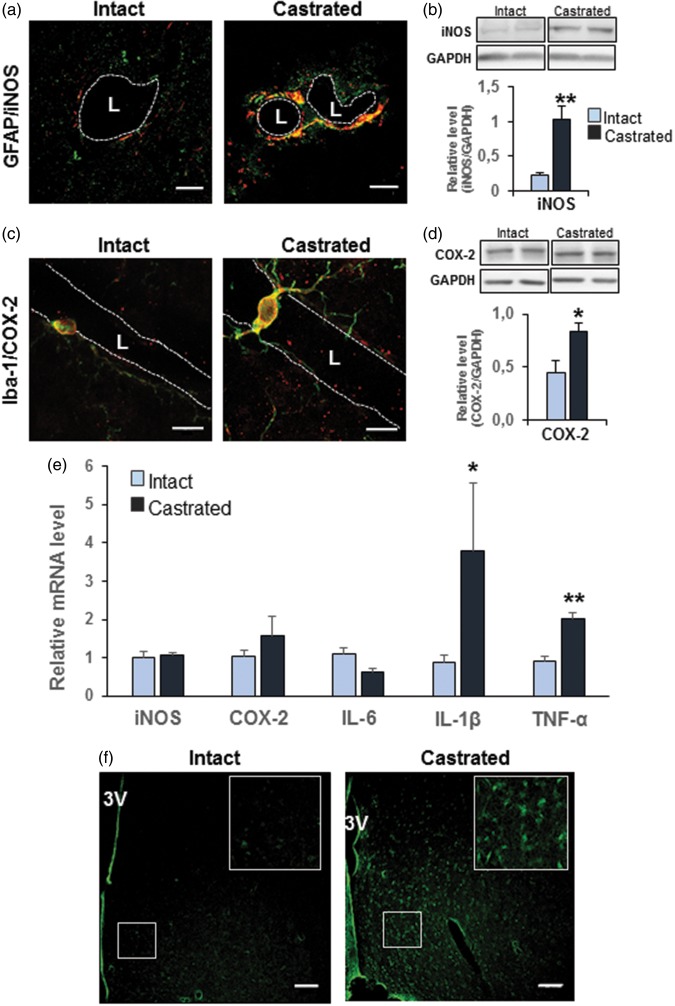

Since microglial and astrocyte activation occurred in the MPOA of castrated males, we asked whether it was associated with an up-regulation of inflammatory molecules, such as COX-2 and iNOS.

Immunofluorescent analysis showed that an intense signal for iNOS colocalized with GFAP labeling surrounding capillaries of castrated mice corresponding to perivascular astrocyte end-feet (Figure 5(a)). This signal was absent in intact control mice. Western blot analysis performed on microvessel-enriched fractions showed a significant increase in the iNOS protein level (+360.4% vs. intact male, p ≤ 0.01; Figure 5(b)). COX-2 protein was immuno-detected in Iba 1-immunopositive microglial cells in the MPOA, and the labeling appeared more intense in cells surrounding capillaries (Figure 5(c)). Western blot analysis performed on capillary-enriched homogenate fractions revealed a significant increase in the COX-2 protein level (+86.4% vs. intact male, p ≤ 0.05) (Figure 5(d)).

Figure 5.

Depletion of gonadal testosterone induced inflammatory molecules. (a) Representative images of co-immuno-detection of iNOS (red) and GFAP (green) performed in three independent experiments per group in the MPOA of intact (left panel) and castrated mice (right panel). iNOS labeling colocalized with GFAP labeling (yellow) surrounding capillaries of castrated mice corresponding to perivascular astrocytes end-feet. Scale bar = 10 µm, n = 3 per group. (b) Western blot analysis performed on microvessel-enriched fractions showing iNOS amount in castrated mice compared with age-matched intact mice. Data were normalized to GAPDH level. Values represent means ± SEM **p ≤ 0.01 compared to the intact group (n = four to five mice per group). (c) Representative images of co-immuno-detection of COX-2 (red) and Iba-1 (green) in the MPOA of intact (left panel) and castrated mice (right panel). COX-2 and Iba-1 were co-localized (yellow), and the labeling appeared more intense in cells surrounding capillaries. Scale bar = 10 µm, n = 3 per group. (d) Western blot analysis performed on microvessel-enriched fractions showing COX-2 amount in castrated mice compared with age-matched intact mice. Data were normalized for GAPDH level. Values represent means ± SEM *p ≤ 0.05 compared to the intact group (n = four to five mice per group). (e) Quantitative analysis by qRT-PCR of transcript levels of iNOS, COX-2, Il-6, IL-1β, and TNF in capillary-enriched fractions of five weeks castrated mice compared with their controls. Data were normalized to HPRT levels. *p ≤ 0.05 and **p ≤ 0.01 compared to the intact group (n = four mice per group). (f) Representative labeling of MPOA sections with Fluoro-Jade® C in intact (left panel) and castrated mice (right panel). Scale bar: 80 µm, n = 2 per group.

L: Lumen; 3V: third ventricle.

To check whether these protein modifications were due to a potential regulation at the transcriptional level, we quantified transcript levels of iNOS and COX-2 and its regulator IL-1β. We also assessed other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF, which can induce inflammation in the CNS. Quantification by qRT-PCR showed a significant increase of the transcript levels of IL-1β (+338.7%, p ≤ 0.05) and TNF (+119.4%, p ≤ 0.01), but not for IL-6, in capillary-enriched fractions of castrated mice compared with their controls (Figure 5(e)). However, no significant changes were detected for iNOS and COX-2 mRNAs (Figure 5(e)) while their respective protein level was increased. This suggests either an early transcriptional regulation, which preceded protein increase and was no more detectable at the time of analysis, or a postranscriptional regulation occurring at the protein level.

Furthermore, we investigated whether these high expression levels of IL-1β and TNF were associated with neuronal cytotoxicity. Cellular degeneration was assessed using the Fluoro-Jade® C fluorescent marker, which is commonly described as a useful specific tool to identify degenerating neurons, activated astrocytes, and microglia during a chronic neuronal degenerating process.22 Our results show a significant increase of Fluoro-Jade-labeling (+673%, 55.68 ± 10.9 mean gray value/µm2 in castrated mice vs. 7.2 ± 1.19 mean gray value/µm2 in intact mice, p ≤ 0.0001) in the MPOA of castrated mice (Figure 5(f)).

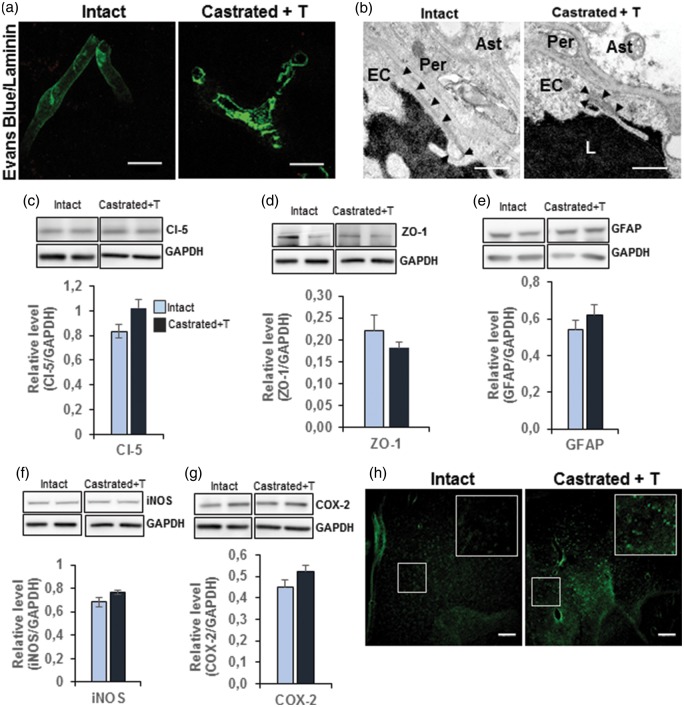

Supplementation of castrated mice with testosterone restored the integrity of BBB and annihilated inflammation

To find out whether the observed alterations induced by castration were permanent or reversible, five-week castrated males were supplemented with testosterone. Thirty days later, the mice were analyzed with age-matched intact mice for BBB permeability, TJ integrity, and glial activation. As shown in Figure 6(a), no extravasation of fluorescent Evans Blue dye was detectable, either within the capillary wall or outside in the surrounding parenchyma in castrated males supplemented with testosterone. Similarly, exogenous–injected HRP enzyme visualized by its DAB precipitate remained confined to the micro-vessel lumen, endothelial cell cytoplasm, and surrounding parenchyma lacking DAB precipitates in testosterone-supplemented castrated mice compared with intact male mice (Figure 6(b)). Concerning the TJ structure, Western blot analysis performed on microvessel-enriched fractions revealed no significant difference in the amounts of claudin-5 and ZO-1 proteins between four-week testosterone-supplemented and intact males (Figure 6(c,d)). Glial activation was assessed by measurement of the amount of GFAP protein. This showed no significant difference of levels in the capillary-enriched fraction (Figure 6(e)), whereas a significant decrease of Iba-1 immuno-positive cells was observed in the MPOA of testosterone-supplemented castrated mice compared to intact mice (−12.2%, 63.23 ± 1.89 vs. 72.02 ± 1.85, p ≤ 0.01). No significant differences were observed for the amounts of iNOS and COX-2 proteins in microvessel-enriched fractions (Figure 6(f,g)). However, Fluoro-Jade-fluorescence density was still significantly higher in the MPOA of testosterone-supplemented castrated mice compared to that in intact mice (+174.6%, 19.77 ± 2.7 vs. 7.2 ± 1.19, p ≤ 0.0001) (Figure 6(h)). Nevertheless, this increase was lower than that found between castrated and intact animals.

Figure 6.

Testosterone supplementation restored BBB permeability and TJ integrity and annihilated inflammation. (a) Representative images of three independent experiments per group showing the absence of Evans blue dye extravasation (red) from capillaries labeled with anti-laminin (green) perfused intact (left panel) and testosterone-supplemented mice (right panel). Scale bar: 10 µm, n = 3 per group. (b) Representative electron micrographs showing a portion of capillaries located in the MPOA after parenteral injection of HRP in intact (left panel) and testosterone-supplemented mice (right panel). DAB precipitates are detected only in the lumen of capillaries of both intact and testosterone-supplemented mice. Scale bar: 1 µm, n = 3 per group. (c–g) Western blot analysis of protein amounts performed on microvessel-enriched fractions from castrated mice compared with testosterone-supplemented mice, claudin-5 (c), ZO-1 (d), GFAP (e), iNOS (f), and COX-2 (g). Data were normalized for GAPDH levels. Values represent means ± SEM of four to six mice per group. There were no significant differences in these protein amounts. (h) Representative images of MPOA sections labeled with Fluoro-Jade® C in intact (left panel) and testosterone-supplemented mice (right panel). Scale bar: 80 µm.

Ast: astrocyte end-feet; EC: endothelial cell; L: lumen; Per: pericyte; arrowheads: tight junction.

Discussion

Our results highlight a potential physiological regulation of BBB integrity in adult male mice by testosterone. We show that the depletion of gonadal testosterone increases permeability of BBB. This was assessed by using different approaches to overcome misleading data obtained by a single approach.16 First, the injection of Evans blue dye suggested BBB leakage in chronically depleted male mice. Second, administration of HRP combined to ultrastructural analysis using a transmission electron microscope demonstrated the presence of extravasated DAB precipitates within endothelial cells and the surrounding brain capillaries. Finally, immuno-detection of endogenous circulating IgG in the brain parenchyma of castrated mice confirmed the permissiveness of BBB to circulating molecules in testosterone-depleted mice.

To determine whether this increased permeability of BBB involved altered structure of TJs at the endothelial cell level, we used electron tomography and 3D-modelisation for the first time. This powerful technology allows 3D-reconstructions from sets of 2D-projections and then the analysis of ultrastructural details that would be difficult to observe with 2D-conventional electron microscopy. Three-dimensional electron microscopy analysis showed disorganized endothelial TJ, which exhibit opening areas.

The analysis of the protein levels of the two main transmembrane proteins required for formation and maintenance of BBB showed a significant reduction of claudin-5, but not of occludin in mice castrated for five weeks. Claudin-5 and occludin are linked to the actin cytoskeleton by sub-membrane accessory scaffolding proteins, including the zonula occludens ZO-1 (see for review, Abbott et al.23). The amount of ZO-1 was also reduced in mice castrated for five weeks. At the functional level, claudin-5, specifically expressed in brain endothelial cells, has been identified as a primary regulator of TJ paracellular permeability to small molecules in physiological conditions.24 Interestingly, down-regulation of claudin-5 expression has been correlated with a breakdown of BBB in an experimental pathological situation.25 Loss or dissociation of ZO-1 from the junctional complexes was also associated with increased barrier permeability.26 Taken together, these observations strongly suggest that despite the unaffected amount of occludin protein, the reduced levels of claudin-5 and ZO-1 proteins must be sufficient to explain the disorganized and increased permeability of BBB in castrated male mice. We cannot exclude, however, changes in the phosphorylation state of occludin in castrated mice, since TJ formation has been shown to be regulated by serine/threonine phosphorylation of occludin.27

These data show here, for the first time, that testosterone modulates levels of claudin-5 and ZO-1 proteins in male mice BBB. In agreement with these observations, a recent in vitro study reported that a pro-androgen sulfated steroid stimulates expression of claudin-5 protein and TJ formation in Sertoli cells.28 Selective ablation of the androgen receptor (AR) in mouse Sertoli cells of the blood–testis barrier–induced abnormal distribution of ZO-1 protein in seminiferous tubules, leading to a delayed and defective blood–testis barrier formation.29 Our findings, together with these observations, indicate that the regulation of TJs by testosterone is not specific to the testis, but extends to the MPOA. Preliminary data suggest that the effects of testosterone depletion can be extended to other androgen-sensitive brain area, although this still needs to be studied in details. Observations illustrated in (SI, Figure S3) show increased extravasation of endogenous IgG and activation of microglial cells in the cortex of castrated mice.

Whether or not it involves the cerebral AR still needs to be determined. In the CNS, gonadal testosterone acts either directly through the AR or indirectly after metabolization into estradiol, which then activates estrogen receptors (ERs). Therefore, AR- as well as ER-signaling pathways could be involved in testosterone-induced regulation of the formation and/or maintenance of TJs in males. Two studies using rat models of injured male brains showed reduced BBB impairment or microvessel growth after estrogen treatment,30 while an in vitro study reported an involvement of the AR in BBB regulation.31

Testosterone depletion in male mice also induced astroglial and microglial activation, as well as an up-regulation of inflammatory molecules such as COX-2, iNOS, IL-1β, and TNF. It is indeed well-established that glial activation is often associated with an up-regulation of various pro-inflammatory molecules including IL-1β, TNF, and iNOS.32 Interestingly, BBB impairment together with increased neuro-inflammation have also been reported in healthy aged female mice where extravasation of circulating IgG into parenchyma was associated with significantly elevated neurovascular inflammation (increased expression of GFAP, COX-2, and TNF).33 Furthermore, accumulating evidence suggests that BBB function is compromised during inflammation.34 Since astrocytes and microglial cells are targets of sex steroids (see for review, Johann and Beyer35), it is possible that in the absence of physiological levels of testosterone, glial cells become activated and promote neuro-inflammatory processes, which then impact on BBB integrity. Alternatively, it seems that BBB breakdown leads to neuro-inflammatory diseases (see for reviews, Zlokovic36,37).

Regardless of the sequence of events induced by testosterone depletion, BBB failure and neuro-inflammation observed in castrated males were accompanied by a significant increase of Fluoro-Jade-fluorescence density, a known marker for neuronal degeneration.38 In agreement with these observations, the castration of young adult male mice–induced Parkinson disease pathologies involving iNOS.39 In this study, the authors proposed a link between circulating levels of testosterone, neurodegenerative diseases, and neuro-inflammation. Furthermore, BBB failure and neuro-inflammation were also associated with other neurological diseases such as Alzheimer's disease,5,40 vascular dementia, and multiple sclerosis.36,37 Here again, dysfunction of BBB may be the cause or consequence of degenerative processes (see for review, Carvey et al.34).

It was of great interest that the supplementation of testosterone to castrated mice restored the impermeability of BBB and the integrity of the capillary endothelial TJ, and suppressed inflammatory features. However, Fluoro-Jade-labeling persisted although it seemed in a lesser amount. This could be due to the fact that during the five weeks of depletion, some cells have advanced so far in neurodegenerative processes that testosterone was not able to reverse this. Alternatively, four weeks of testosterone supplementation might be insufficient to drive this reversibility. Further experiments will explore whether longer periods of testosterone supplementation could blunt this process or not.

Except for the neurodegenerative cells, these results highlight the activating and transitory effects of circulating testosterone on these cerebrovascular functions. We propose that, as for estrogens in females, physiological levels of testosterone have a protective effect in male mice. This is of particular interest since aging in males is associated with hypogonadism, which seems to contribute to the increased incidence of cerebrovascular disease.9 Whether testosterone-effects act by genomic and/or non-genomic modes still needs to be defined. To our knowledge, this is the first in vivo study that explores the reversible effect of a steroid hormone on cerebrovascular functions. These data open new perspectives for the use of testosterone or analogs as physiological modulators of BBB permeability in therapeutic treatments.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that the depletion of gonadal testosterone for five weeks is deleterious for normal brain function since it leads to BBB dysfunction concomitantly with an inflammatory process in the preoptic area of male mice. Supplementation of testosterone was sufficient to restore these deficits, except for cellular degeneration, which persisted although at a lower level after four weeks of treatment. This highlights the transitory activating role of testosterone on BBB physiology and neuro-inflammation. Understanding in this physiological model how testosterone operates to impact these processes is of great relevance. Indeed, as other brain regions are also highly sensitive to androgens such as the cortex and hippocampus, this could provide new insights into neurological and metabolic diseases, which are linked to the hormonal status, and help to improve the outcome of hormone replacement in hypogonadic men of different ages.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ilse Hurbain (Institut Curie Centre de Recherche, UMR CNRS 144, Paris, France) for advice, skill, and expertise for electron tomography acquisitions and 3D-modelisation, and the BioImaging Cell and Tissue Core Facility of the Institut Curie (PICT-IBiSA), a member of the French National Research Infrastructure France-BioImaging (ANR-10-INSB-04). We thank Dr. Sheela Vyas (Neuroscience Paris-Seine, IBPS, Paris, France) and her PhD student, Anne-Claire Le Compagnion, for their assistance with qRT-PCR analysis. We thank the rodent facility of the Institut de Biologie Paris-Seine (IBPS, Paris, France) for taking care of the animals and the IBPS Imaging facility (electron microscopy and photon microscopy).

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the University Pierre and Marie Curie, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM)

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author contributions

A.A. and V.G.M. conceived and designed the project. A.A. performed castration of male mice, BBB permeability assay, immunochemistry, Western blot, and qRT-PCR analysis. V.G.M. performed electron microscopy and electron tomography studies. A.A. and V.G.M. wrote the manuscript with significant input from S.M.K.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this paper is available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/0271678X16683961.

References

- 1.Ballabh P, Braun A, Nedergaard M. The blood-brain barrier: an overview: structure, regulation, and clinical implications. Neurobiol Dis 2004; 16: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gumbiner BM. Breaking through the tight junction barrier. J Cell Biol 1993; 123: 1631–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wardlaw JM, Doubal F, Armitage P, et al. Lacunar stroke is associated with diffuse blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Ann Neurol 2009; 65: 194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zipser BD, Johanson CE, Gonzalez L, et al. Microvascular injury and blood-brain barrier leakage in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2007; 28: 977–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maysami S, Haley MJ, Gorenkova N, et al. Prolonged diet-induced obesity in mice modifies the inflammatory response and leads to worse outcome after stroke. J Neuroinflam 2015; 12: 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Vliet EA, da Costa Araújo S, Redeker S, et al. Blood-brain barrier leakage may lead to progression of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain J Neurol 2007; 130: 521–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Rudd AG, Wolfe CDA. Age and ethnic disparities in incidence of stroke over time: the South London Stroke Register. Stroke J Cereb Circ 2013; 44: 3298–3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeap BB, Hyde Z, Almeida OP, et al. Lower testosterone levels predict incident stroke and transient ischemic attack in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94: 2353–2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uchida M, Palmateer JM, Herson PS, et al. Dose-dependent effects of androgens on outcome after focal cerebral ischemia in adult male mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab Off J Int Soc Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2009; 29: 1454–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krause DN, Duckles SP, Gonzales RJ. Local oestrogenic/androgenic balance in the cerebral vasculature. Acta Physiol Oxf Engl 2011; 203: 181–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelligrino DA, Galea E. Estrogen and cerebrovascular physiology and pathophysiology. Jpn J Pharmacol 2001; 86: 137–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strom JO, Theodorsson A, Theodorsson E. Dose-related neuroprotective versus neurodamaging effects of estrogens in rat cerebral ischemia: a systematic analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2009; 29: 1359–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu M, Kelley MH, Herson PS, et al. Neuroprotection of sex steroids. Minerva Endocrinol 2010; 35: 127–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ulbrich C, Zendedel A, Habib P, et al. Long-term cerebral cortex protection and behavioral stabilization by gonadal steroid hormones after transient focal hypoxia. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2012; 131: 10–16. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uchida M, Palmateer JM, Herson PS, et al. Dose-dependent effects of androgens on outcome after focal cerebral ischemia in adult male mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2009; 29: 1454–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raskin K, Marie-Luce C, Picot M, et al. Characterization of the spinal nucleus of the bulbocavernosus neuromuscular system in male mice lacking androgen receptor in the nervous system. Endocrinology 2012; 153: 3376–3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werner C, Reeker W, Engelhard K, et al. Ketamine racemate and S-(+)-ketamine. Cerebrovascular effects and neuroprotection following focal ischemia. Anaesthesist 1997; 46: S55–S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandoval KE, Witt KA. Age and 17β-estradiol effects on blood-brain barrier tight junction and estrogen receptor proteins in ovariectomized rats. Microvasc Res 2011; 81: 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carrillo-de Sauvage MÁ, Maatouk L, Arnoux I, et al. Potent and multiple regulatory actions of microglial glucocorticoid receptors during CNS inflammation. Cell Death Differ 2013; 20: 1546–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ros-Bernal F, Hunot S, Herrero MT, et al. Microglial glucocorticoid receptors play a pivotal role in regulating dopaminergic neurodegeneration in parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108: 6632–6637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 2001; 29: e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Damjanac M, Rioux Bilan A, Barrier L, et al. Fluoro-Jade B staining as useful tool to identify activated microglia and astrocytes in a mouse transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 2007; 1128: 40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abbott NJ, Patabendige AAK, Dolman DEM, et al. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis 2010; 37: 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piontek J, Winkler L, Wolburg H, et al. Formation of tight junction: determinants of homophilic interaction between classic claudins. FASEB J Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol 2008; 22: 146–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Argaw AT, Gurfein BT, Zhang Y, et al. VEGF-mediated disruption of endothelial CLN-5 promotes blood-brain barrier breakdown. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 1977–1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi YK, Kim K-W. Blood-neural barrier: its diversity and coordinated cell-to-cell communication. BMB Rep 2008; 41: 345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakakibara A, Furuse M, Saitou M, et al. Possible involvement of phosphorylation of occludin in tight junction formation. J Cell Biol 1997; 137: 1393–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papadopoulos D, Dietze R, Shihan M, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate stimulates expression of blood-testis-barrier proteins claudin-3 and -5 and tight junction formation via a Gnα11-coupled receptor in sertoli cells. PloS One 2016; 11: e0150143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willems A, Batlouni SR, Esnal A, et al. Selective ablation of the androgen receptor in mouse sertoli cells affects sertoli cell maturation, barrier formation and cytoskeletal development. PloS One 2010; 5: e14168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samantaray S, Das A, Matzelle DC, et al. Administration of low dose-estrogen attenuates persistent inflammation, promotes angiogenesis and improves locomotor function following chronic spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurochem 2016; 137: 604–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohtsuki S, Tomi M, Hata T, et al. Dominant expression of androgen receptors and their functional regulation of organic anion transporter 3 in rat brain capillary endothelial cells; comparison of gene expression between the blood-brain and -retinal barriers. J Cell Physiol 2005; 204: 896–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghoshal A, Das S, Ghosh S, et al. Proinflammatory mediators released by activated microglia induces neuronal death in Japanese encephalitis. Glia 2007; 55: 483–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elahy M, Jackaman C, Mamo JC, et al. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction developed during normal aging is associated with inflammation and loss of tight junctions but not with leukocyte recruitment. Immun Ageing A 2015; 12: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carvey PM, Hendey B, Monahan AJ. The blood-brain barrier in neurodegenerative disease: a rhetorical perspective. J Neurochem 2009; 111: 291–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johann S, Beyer C. Neuroprotection by gonadal steroid hormones in acute brain damage requires cooperation with astroglia and microglia. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2013; 137: 71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron 2008; 57: 178–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease and other disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011; 12: 723–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu C-K, Thal L, Pizzo D, et al. Apoptotic signals within the basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Exp Neurol 2005; 195: 484–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khasnavis S, Ghosh A, Roy A, et al. Castration induces Parkinson disease pathologies in young male mice via inducible nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem 2013; 288: 20843–20855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deane R, Zlokovic BV. Role of the blood-brain barrier in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2007; 4: 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.