ABSTRACT

Age-related health decline has been attributed to the accumulation of senescent cells recognized in vivo by p16(Ink4a) expression. The pharmacological elimination of p16(Ink4a)-positive cells from the tissues of mice was shown to extend a healthy lifespan. Here, we describe a population of mesenchymal cells isolated from mice that are highly p16(INK4a)-positive are proficient in proliferation but lack other properties of cellular senescence. These data, along with earlier reports on p16(Ink4a)-positive macrophages, indicate that p16(Ink4a)-positive and senescent cell populations only partially intersect, therefore, extending the list of potential cellular targets for anti- aging therapies.

KEYWORDS: p16(Ink4a), senescence, biomarkers, senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-βGal), healthspan

Introduction

Despite the lack of specificity associated with senescence-associated biomarkers, several studies have conventionally linked the expression of p16(Ink4a) (encoded by the Ink4a/Arf locus, also known as Cdkn2a) and senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-βGal) activity to cellular senescence.1 Senescence is a phenotypic tumor-suppressor phenomenon that prevents a cell from replicating in the presence of unresolved constitutive DNA damage.2,3 Supporting the claim that the accumulation of senescent cells over a lifetime is detrimental to the organism, the pharmacological elimination of p16(Ink4a)-positive cells (as monitored and validated by loss of SA-βGal activity in various tissues and organs) has been shown to result in improved physiological performance consistent with rejuvenation, i.e. a reduction in biological age, using wild-type and genetically engineered mice predisposed to accelerated aging.4-6

Although p16(Ink4a)-positive cells naturally accumulate with age,4,6-8 we recently demonstrated that p16(Ink4a)/SA-βGal-positive cells may be elicited in young mice via the intraperitoneal injection of alginate-embedded human neonatal dermal fibroblasts (NDFs).9 The implantation of these 0.5-mm alginate capsules provokes a robust host-mediated immune response that leads to the accumulation of immunocytes (including myeloid cells, neutrophils and macrophages) within the peritoneal cavity and the subsequent accumulation of immune cells along the capsule surface.9,10 Recent studies using this alginate capsule model suggest macrophages (termed Senescence-Associated Macrophages or SAMs) are an abundant source of p16(Ink4a)-positivity in vivo, as measured via an endogenous promoter-driven luciferase cassette in p16Ink4a/Luc mice (Fig. 1A). Importantly, clearance of macrophages using liposomal clodronate (a bisphosphonate drug used to specifically target and clear macrophages) results in substantial loss of luciferase expression from chronically aged p16Ink4a/Luc mice, as well as the elimination of SA-βGal activity from inguinal and visceral fat,9 suggesting macrophages (and not necessarily senescent cells) are a major source of p16(Ink4a) positivity in aged mice. Intriguingly, the treatment of cells along the capsule surface (referred to as capsule-bound cells or CBCs) with liposomal clodronate was ineffective in completely eliminating p16(Ink4a) expression, suggesting that in addition to macrophages, other types of cells might also be responsible for luciferase signal.9 Therefore, in this study, we sought to perform a more precise accounting of these capsule-bound cells responsible for p16(Ink4a) expression.

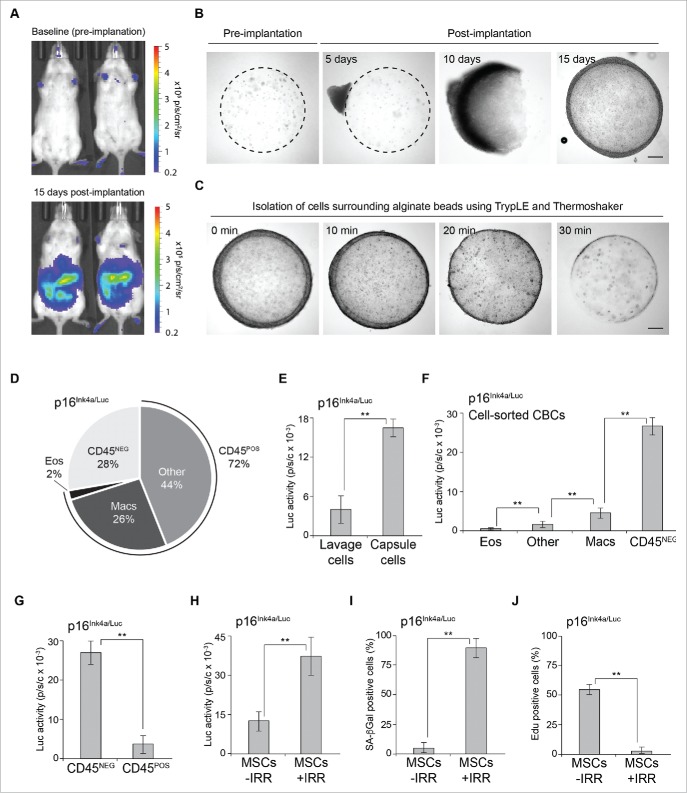

Figure 1.

CD45NEG cells isolated from alginate capsules are highly p16-luciferase positive. (A) Representative bioluminescent in vivo imaging of 20-week old p16Ink4a/Luc mice pre-implantation (top panel) and post-implantation (lower panel) of alginate-embedded NDFs. The scale depicts relative luminescent signal intensity of minimum and maximum thresholds, displayed in terms of radiance. (B) Representative brightfield images of alginate capsules containing embedded irradiation-induced senescent NDFs before implantation (left panel) and post-implantation at the indicated time points. Bar, 0.1mm. (C) Representative brightfield images of alginate beads containing embedded with NDFs (as in A) subjected to TrypLE and shaking on a Thermoshaker for 10, 20 and 30 minutes at 37°C. Bar, 0.1mm. (D) Cell composition analysis of isolated capsule-bound cells (CBCs) from p16Ink4a/Luc mice by flow cytometry on live cells immunostained for surface markers. The percent contribution to major cell types is depicted: eosinophils (Eos), macrophages (Mac) and remaining cell populations, including B lymphocytes (Other) and CD45NEG cells. Analysis depicts a representative experiment. (E) Cell lysates from whole lavage or CBCs (isolated as in A) were normalized to cell number and assayed for luciferase activity. Values were and normalized to cell number. Standard deviations were calculated from triplicates, and an unpaired Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. ** indicates p-value of <0.001. (F) Cell sorted populations from p16Ink4a/Luc mice were assayed for luciferase activity. Values were normalized to cell number. Standard deviations were calculated from triplicates, and an unpaired Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. ** indicates p-value of <0.001. (G) CD45NEG and CD45POS cell sorted populations from p16Ink4a/Luc mice were assayed for luciferase activity. Values were normalized to cell number. Standard deviations were calculated from triplicates, and an unpaired Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. ** indicates p-value of <0.001. (H) Adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) isolated from p16Ink4a/Luc mice were assayed for luciferase activity following 10-days post treatment with IRR (20 Gy) or in the absence of IRR treatment, respectively. Values were normalized to cell number. Standard deviations were calculated from triplicates, and an unpaired Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. ** indicates p-value of <0.001. (I) Quantification of the percentage of SA-βGal-positive MSCs treated with or without IRR (as in A). Standard deviations were calculated from triplicates, and an unpaired Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. ** indicates p-value of <0.001. (J) Quantification of the percentage of EdU-positive MSCs treated with or without IRR (as in A). Standard deviations were calculated from triplicates, and an unpaired Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. ** indicates p-value of <0.001.

Results and discussion

Previous attempts to isolate the dense layer of CBCs relied on an EDTA-based dissociation buffer coupled with a tissue homogenizer, compromising cellular viability and loss of sample purity.9,10 Consequently, we developed a protocol that allowed for the isolation of viable capsule-bound cells while congruently avoiding contamination from the alginate-embedded NDFs. To that end, we implanted alginate beads containing NDFs intraperitoneally in C57BL/6J mice and allowed them to remain in the IP cavity for up to 15-days (Fig. 1A and B). Extraction of these alginate beads from the peritoneum showed nucleation by day 5 and gradual envelopment of capsules between days 10–15 (Fig. 1B). Next, we resuspended extracted beads with TrypLE, a recombinant form of trypsin that is gentle on cells and preserves the integrity of cell-surface proteins,11 and tubes were placed in a Thermoshaker set to 37°C and shaken at 1400 RPM for 30 minutes.

Efficiency of capsule undressing was monitored by brightfield microscopy and/or fluorescence microscopy from beads isolated from C57BL/6J mice (wild-type or transgenic mice constitutively expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP), respectively) (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1A). Isolation of CBCs via this method yielded approximately 5-times as many cells from the capsule surface and recovered >90% of cells from beads, compared with using TrypLE alone or shaking with complete cell culture media, respectively, while leaving the alginate capsule intact (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1D-G). Importantly, the viability of the cells recovered via this TrypLE shake-based method was >95% (Fig. S1E), and immunostaining of live cells demonstrated CBCs retained cell surface markers for subsequent cell-sorting procedures (Fig. S1H).

To identify the cell population(s) that contribute to p16(Ink4a) expression and SA-βGal activity, we implanted alginate capsules containing NDFs in 20-week old C57BL/6J p16Ink4a/Luc mice, isolated CBCs (as described above) and subjected these cells to live-staining followed by fluorescence-activated cell-sorting (FACS), as previously performed.9 We validated the accuracy of our cell-sorting procedure via immunostaining with known immune cell markers (Fig. S2A-C). FACS analysis revealed 72% of cells to be of haematopoietic origin (> 70% CD45+; CD45POS), which were comprised of eosinophils (CD19− CD11b+ CD170+; 2%), macrophages (CD19− CD11b+ F4/80+; 26%) and a pool of remaining cells (44%) that included B lymphocytes (CD19+; 35%), neutrophils (CD11b+ Ly-6G+), T lymphocytes (CD11b−) and monocytes and NK cells (CD11b+ F4/80−) (Fig. 1D). Notably, approximately 28% of capsule-bound cells were CD45 negative (CD45−; CD45NEG) and presumably of mesenchymal origin (Fig. 1D).

Measurement of luciferase from intraperitoneal lavage and unsorted CBCs revealed the majority of p16-luciferase signal originated from capsule-bound cells (Fig. 1E). We confirmed this difference in expression via immunoblots of lavage and CBC protein lysates (isolated from wild-type C57BL/6J mice) using p16(Ink4a) antibodies (Fig. S3A). As previously observed,9 CD45POS sorted populations revealed a substantial enrichment of p16-lucifease in macrophages but not in other cell types (Fig. 1F). Unexpectedly, analysis of luciferase signal originating from CD45NEG cells appeared significantly higher (> 4-fold) than the macrophage population or the CD45POS population, suggesting an additional and major source of p16(Ink4a) expression from cells of mesenchymal origin (Fig. 1F and G). Again, we confirmed p16(Ink4a) expression in CD45NEG and CD45POS cells via immunoblots of cellular lysates generated from wild-type C57BL/6J mice (Fig. S3B). Notably, measurement of luciferase from adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells isolated from p16Ink4a/Luc mice and exposed to irradiation (IRR; 20 Gy) to induce senescence showed similar p16 levels coupled with markers of cellular senescence (Fig. 1H-J).

Monocytes are capable of differentiating into fibroblast-like cells called fibrocytes,12 thus, we sought to determine if capsule-bound CD45NEG cells were strictly of mesenchymal origin. To that end, myeloablation was induced by exposing 8-week old C57BL/6 mice to a lethal dose of total body irradiation (TBI) (11 Gy) followed by bone marrow transplantation (BMT) using syngeneic donors constitutively expressing GFP.13 We implanted alginate capsules containing NDFs in control 20-week old C57BL/6 animals and BMT-GFP mice (following a 12-week recovery after BMT), isolated CBCs and subjected these cells to live-staining followed by FACS (Fig. S4A-C). FACS analysis revealed >25% of capsule-bound cells from untreated mice were CD45NEG (as expected) whereas GFP+CD45NEG double-positive cells from BMT-GFP mice comprised<0.5% (Fig. S4D). Importantly, the percentage of CD45POS cells were comparable in each condition (Fig. S4D). Together, these data indicate that CD45NEG cells isolated from the capsule surface are indeed of mesenchymal origin.

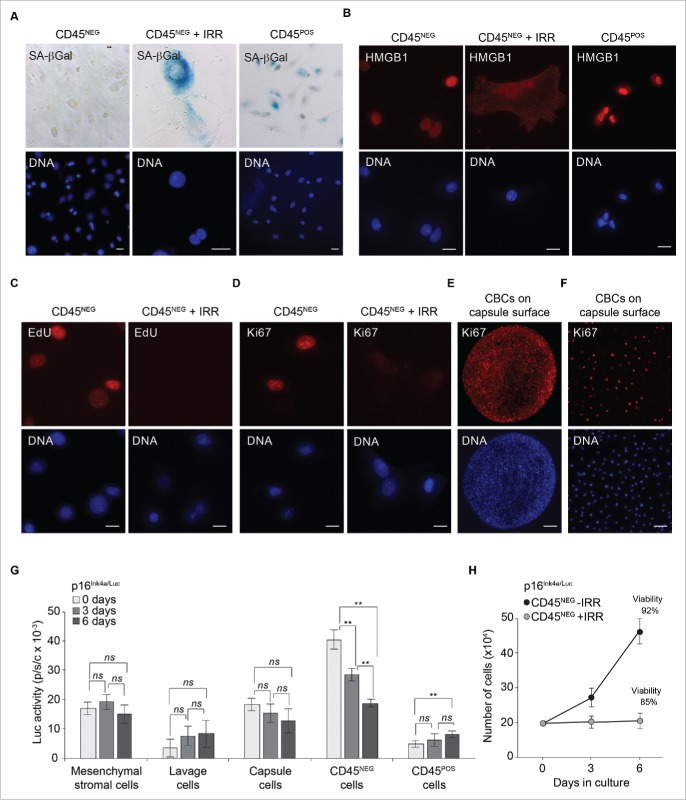

Given the elevated levels of p16(Ink4a) in CD45NEG cells, we sought to determine if these cells possessed markers characteristically associated with cellular senescence. To that end, we performed SA-βGal staining on cell-sorted populations and observed SA-βGal positivity in CD45POS cells (as expected in macrophages) but not in CD45NEG cells (Fig. 2A and Fig. S4A). Importantly, following senescence induced by IRR, CD45NEG cells stained positive for SA-βGal (Fig. 2A and Fig. S4A). Another frequently used senescence marker, High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) is a transcription factor and nuclear-resident protein shown to relocate to the cytosol and extracellular milieu in senescent cells.14 Immunostaining of CD45NEG cells (including CD45POS cells) revealed exclusive nuclear HMGB1 localization in the majority of cells compared with IRR-treated cells (Fig. 2B and Fig. S4B).

Figure 2.

CD45NEG do not display markers of cellular senescence. (A) Representative brightfield images of CD45NEG, CD45NEG cells after IRR (20 Gy) and CD45POS cells isolated from alginate capsules via FACS and stained for SA-βGal. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Immunostaining of CD45NEG cells, CD45NEG cells after IRR (20 Gy) and CD45POS cells with an anti-HMGB1 antibody (red). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Bar, 10 μm. (C) EdU-incorporation was determined by fluorescence detection of CD45NEG cells or CD45NEG cells treated with IRR (20 Gy). EdU was added to the medium (10 μM) and left 12 hours to allow its incorporation into newly synthesized DNA and detected by azide AlexaFluor 594 (red). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Bar, 10 μm. (D) Immunostaining of CD45NEG cells, CD45NEG cells treated with IRR and CD45POS cells isolated from alginate capsules (retrieved as in A) with an anti-Ki67 antibody (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Bar, 10 μm. (E) Immunostaining of capsule-bound cells (CBCs) on the surface of the alginate capsule with an anti-Ki67 antibody (red). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Bar, 0.1 mm. (F) Immunostaining of capsule-bound cells (CBCs) on the surface of the alginate capsule with an anti-Ki67 antibody (red). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Bar, 5 μm. (G) Over the course of 6-days, cell lysates from adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells, whole lavage, CBCs and cell-sorted CD45NEG and CD45NEG were normalized to cell number and assayed for luciferase activity. Values were and normalized to cell number. Standard deviations were calculated from triplicates, and an unpaired Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. ** indicates p-value of <0.001. ns indicates non-significant. (H) Growth curve of CD45NEG and CD45NEG cells treated with IRR (20 Gy) over the course of 6-days. Cellular viability was measured at the end of experiment (as indicated).

To determine if p16(Ink4a)-positive CD45NEG cells possessed the potential to proliferate, we used the thymidine analog 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) to measure DNA synthesis.15 EdU-incorporation over a 12-hour period demonstrated a robust proliferation index (> 50%) in CD45NEG cells compared with CD45POS cells and IRR-induced senescent cells (Fig. 2C and Fig. S4C). Next, we immunostained cells with an antibody against Ki67, a well-established marker of proliferation,16 and we observed approximately 75% of CD45NEG cells showed Ki67 positivity (Fig. 2D and Fig. S4D and E). To exclude that these proliferation indices were a manifestation of ex vivo cell culturing conditions, we immunostained cells residing on capsules following extraction from the peritoneal cavity with Ki67 and observed the presence of proliferating cells (Fig. 2E and 2F). Measurement of p16-expression from cultured CD45NEG cells revealed a gradual decrease in luciferase levels over the course of 6 days, reaching baseline levels comparable to proliferating adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (Fig. 2G). Correspondingly, we observed cell proliferation over the course of 6 d at low oxygen and observed CD45NEG cells were capable of population doubling, while CD45NEG cells treated with IRR were irreversibly growth arrested (Fig. 2H).

In summary, our study demonstrates that primary CD45NEG cells isolated from the surface of intraperitoneally-injected alginate beads are of mesenchymal origin and highly p16(Ink4a)-positive. We show these CD45NEG cells are proliferation competent in vivo and ex vivo, but remarkably do not display additional markers of senescence, including SA-βGal and cytosolic HMGB1 staining. As loss of SA-βGal activity is commonly used as the experimental readout for clearance of so-called “p16(Ink4a)-positive senescent cells,” the biological advantage of removing p16(Ink4a)-positive cells that are SA-βGal negative and therefore blind to detection (such as those identified in this study) is unknown. Furthermore, given that senescence phenotypes also appear in the absence of p16(Ink4a) expression following exposure to various DNA damaging agents,17-19 including after ionizing radiation, these data cast further doubt on the validity of using p16(Ink4a) as a bona fide senescence indicator and cellular target for anti-aging therapies.

Materials & methods

Animals

C57BL6/J mice with hemizygous p16(INK4a) knock-in of firefly luciferase (p16Ink4a/Luc) were obtained from Dr. Normal E. Sharpless.8 Wild-type C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), and C57BL/6-Tg(UBC-GFP) 30Scha/J mice (referred to as GFP mice) were bred and maintained at Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI). Animals were provided a commercial rodent diet (5% 7012 Teklad LM-485 Mouse/Rat Sterilized Diet, Harlan) and sterile drinking water ad libitum. All animals were confined to a limited access facility with environmentally-controlled housing conditions throughout the entire study and maintained at 18–26º C, 30–70% air humidity and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Animals were housed in micro-isolation cages under pathogen-free conditions, and if necessary, acclimatized in the housing conditions for at least 5 d before the start of the experiment. Animal usage in this experiment was approved under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the RPCI. Implantation of alginate bead cultures in 20-week old C57BL/6 animals was performed as described previously.9 Total body irradiation (TBI) of 8-week old C57BL/6 animals followed by bone marrow transplantation (BMT) was performed as described previously.20

Cell culture

Human NDFs were purchased from AllCells and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS serum, 100 units/mL of penicillin, 100 µg/mL of streptomycin, and 2 mM L-Glutamine. NDFs were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. To propagate NDF cells, cells were washed once with PBS and trypsin/EDTA was added to detach cells from the tissue-culture dish surface. To stop the Trypsin/EDTA reaction, culture medium was added and cells were resuspended. Resuspended cells were counted and the viability measured using the automated cell counter NC-3000 and Via1 cassettes (Chemometec) according to the manufacturer's protocol. To induce senescence by IRR, cells grown to confluence and serum-starved for 48 hours before being subjected to 10 Gy IRR, as previously reported.11 IRR-treated cells were plated and allowed to senesce for 2–3 wk, depending on experimental plans. Primary CD45NEG cells FACS sorted from capsule-bound cells (CBCs) were plated and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS serum, 100 units/mL of penicillin, 100 µg/mL of streptomycin, and 2 mM L-Glutamine. Primary CD45POS cells FACS sorted from CBCs were plated and maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FBS serum, 100 units/mL of penicillin, 100 µg/mL of streptomycin, and 2 mM L-Glutamine. All primary murine cells were cultured at 37°C in a low-oxygen incubator with 5% CO2. Prism 6 (GraphPad) and Excel (Microsoft) were used to process and graph data.

Generation of alginate capsules containing NDFs

Generation of alginate capsules containing senescent NDFs was performed as described previously.9 Briefly, ultra-pure low-viscosity (20–200 mPas) sodium alginate (PRONOVA UP LVG) powder was purchased from NovaMatrix (Sandvika, Norway) and dissolved in a 1% (w/v) mannitol solution to make a 3% (w/v) solution of sodium alginate. The final solution was filter-sterilized (0.2 μm) and stored at 4°C. A 100mM solution of strontium chloride (SrCl2) (Sigma) dissolved in sterile water was used for alginate gelation. NDF cells were mixed with the 3% alginate solution (0.9 mL), and after thorough mixing, immediately loaded into a 1-mL syringe for extrusion. The alginate encapsulation procedure was based on a gas-driven mono-jet device positioned 14-cm above the 100 mM SrCl2 gelling solution, which was continuously stirred via magnet stir bar (700 rpm). The suspension of NDF cells in alginate was sprayed into the gelling solution at an infusion rate of 0.7 mL/min and air flow rate of 7.5 L/min. Alginate-coated beads were incubated in the gelling solution for 5 minutes, followed by thorough washing in PBS and transferred to warm complete medium. Beads were incubated on a shaker for at least 24 hours in a tissue culture incubator before injection. Viability of senescent NDF cells embedded in alginate beads was verified by Calcein AM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) / propidium iodide (Sigma) staining of live/dead cells.

Isolation of capsule-bound cells (CBCs)

Collection of alginate capsules was performed as described previously.9 Briefly, the wall of the abdomen was opened, and capsules were then flushed from the peritoneal cavity with saline containing 2% heat-inactivated FBS in a 50mL conical tube. To isolate CBCs, capsules were allowed to pellet by gravity and then washed twice in PBS before resuspension in TrypLE Express (ThermoFisher Scientific). 1.5 mL of TrypLE Express was used for every 200 mL of packed capsule volume, and this suspension was placed in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. Capsules/TrypLE mix was shaken on a Thermoshaker (Eppendorf) at 1400 RPM at 37°C for 30 minutes. After shaking, capsules were allowed to pellet by gravity, and the supernatant was collected, placed in a 15mL conical tube with complete media (to neutralize TrypLE) and centrifuged at 500 x g for 5 minutes. Cells were resuspended in appropriate medium, strained (40 μm cell strainer), counted and the viability measured using the automated cell counter NC-3000 and Via1 cassettes (Chemometec) according to the manufacturer's protocol. To induce senescence in CD45NEG cells by irradiation (IRR), cells subjected to 20 Gy IRR.

FACS and cell-sorting

Cell-sorting procedure was performed as described previously.9 Before staining, mouse peritoneal lavage cells were treated with BD Pharm Lyse lysing buffer (diluted to 1X in sterile, double-distilled water) for red blood cell lysis, then washed and resuspended in flow cytometry staining buffer (eBioscience; San Diego, CA). After blocking with anti–CD16/CD32 antibodies (clone 93, eBioscience) for 10 minutes the cells were stained with the following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to surface receptors in an 8-color staining combination: FITC-labeled anti-Ly-6G (1A8, Miltenyi Biotec); V500-labeled CD11b (M1/70, BD Horizon), and antibodies from eBioscience: PE-labeled anti-CD335 (29A1.4); PE/Cy5.5-labeled anti-CD19 (eBio1D3); PerCp-eFluor710-labeled anti-CD170 (1RNM44N); APC-labeled anti-CD45.2 (104); APC-eFuor780 labeled F4/80 (BMB); eFluor450-labeled anti-Ly-6C (HK1.4). After a 30-minute incubation on ice, cells were washed with staining buffer and resuspended in the same buffer. To distinguish dead cells, impermeable DNA stain Bobo3 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon) was added to the cell suspension (20 nM final concentration) 3 minutes before acquisition. All sorting and analysis experiments were performed on RPCI FACS facility using custom instruments from BD Immunocytometry systems (FACSAria I or LSRII, respectively) and BD FACS Diva Software (BD Biosciences). Data were collected for >10 × 106 cells and analyzed with FCS Express 4 (De Novo Software; Glendale, CA). To distinguish autofluorescent cells from cells expressing low levels of individual surface markers (in case of CD11b, Ly-6G, F4/80 and CD335 markers), we established upper thresholds for autofluorescence by staining samples with fluorescence-minus-one control stain sets in which a reagent for a channel of interest is omitted. Compensation was performed using single-color controls prepared with OneComp beads (eBioscience), or single-stained cell suspensions and calculated either with FACS Diva Software (in case of sorting) or with FCS Express (for composition analysis). Excel (Microsoft) was used to process and graph data.

Microscopy

To detect cell-surface antigens following isolation from capsules, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and incubated for 30 min in blocking solution (2% heat-inactivated goat serum in PBS). Following incubation with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution, cells were washed in PBS 3 times and stained for DNA (Hoechst 33342 Solution). Cells were then placed on poly-L-lysine coated slides, allowed to attach and fixed with addition of 4% formaldehyde. For intracellular immunostaining, cells were fixed with 2–4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, washed 3 times with PBS and then incubated for 15 min in blocking solution (5% normal donkey serum, 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS). This was followed by incubation with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution, 3 washes with PBS and incubation with secondary antibodies (if required) in blocking solution. Stained cells were mounted with ProLong Gold anti-fade reagent (Life Technologies). To immunostain capsule-bound cells, capsules were fixed with 2–4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, washed 3 times with PBS and then incubated for 15 min in blocking solution (5% normal donkey serum, 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS). This was followed by incubation with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution, 3 washes with PBS and incubation with secondary antibodies (if required) in blocking solution. Primary antibodies used in this study: anti-CD45 (BioLegend, 109813), anti-CD11b (Bio-Rad MCA74A647), anti-F4/80 (BioLegend, 123140), anti-Ki67 (BD PharMingen, 558617), anti-HMGB1 (Sigma, H9664). Percentage of senescent cells was determined by SA-β-Gal assay, as described previously.11 DNA synthesis was studied by EdU- incorporation following detection with azide AlexaFluor 594 (Invitrogen) according to published procedure.21

Firefly luciferase assay

Measurement of luciferase activity was performed as described previously.9 Briefly, luciferase activity was accessed using Bright-Glo™ Luciferase Assay System (Promega; Madison, WI) according to manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications. Briefly, cell lysates (as described previously) or cell suspensions in D-PBS were added to a 96-well white plate (OptiPlate-96, Perkin Elmer), followed by the addition of an equal volume of 2x reconstituted Bright-Glo™ Assay Reagent. Acquisition of the luminescent signal was performed on the Infinite® M1000 PRO microplate reader (Tecan; Männedorf, Switzerland). The mean maximum signal from technical replicates was used to estimate the luciferase activity for each sample. Background readings were measured after incubation of equal volumes of 2X luciferase reagent with either D-PBS or lysis buffer (as appropriate). Background signal was subtracted from sample signal, and normalized either by cell number or protein content per reaction. The ratio of background signal to sample signal (signal-to-noise ratio) was calculated for each sample. Sample signals less than 2-fold above background were considered to not be reliably detectable. To estimate detection threshold for a given sample, the background signal was normalized to cell number or protein amount in the reaction. Prism 6 (GraphPad) and Excel (Microsoft) were used to process and graph data.

Bioluminescent imaging

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with a 200 µl solution of 15 mg/mL D-luciferin potassium salt (Syd Labs; Boston, MA) in D-PBS without calcium and magnesium. At 10-minutes post-injection, isoflurane-anesthetized mice were placed into the IVIS Spectrum in vivo bioluminescent imaging system (PerkinElmer; Waltham, MA) for detection of luciferase activity (60-second exposure). Bioluminescence in p16LUC mice was quantified as total flux (p/s) of luminescent signal from the abdomen using via Living Image® software.

Western blotting

Cellular lysates were generated from cells harvested with TrypLE Express. To remove traces of TrypLE Express and media, cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS and pelleted at 500 × g for 5 min. Cell pellets were directly resuspended in 100 μL per 1 × 106 cells in 2X sample buffer [75 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 2.5% β-mercaptoethanol] and DNA was sheered using a 27 gauge needle. Immunoblotting was performed as described previously.11 Samples were resuspended in sample buffer and were loaded on a Mini-Protean TGX 4–12% Gradient SDS/PAGE gel (Bio-Rad) and electrophoresed at 100 V. The proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes in transfer buffer [25 mM Tris, 0.192 M glycine, and 20% (vol/vol) methanol] using Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (Bio-Rad). After blocking for 30 min at room temperature with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk in TBS-T, membranes were incubated in TBS-T for 1 hour at room temperature with the following primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti-p16(Ink4a) antibody (ProteinTech, 10883–1-AP), mouse monoclonal anti-p16(Ink4a) antibody (Cell Applications, CP10342) and GAPDH (Cell Signaling, D16H11). A goat anti-mouse IgA+IgG+IgM(H+L) HRP-conjugated antibody (KPL) and a goat anti-rabbit IgA+IgG (H+L) HRP-conjugated antibody (ThermoFisher Scientific) were used as secondary antibodies for detection. Following incubation with secondary antibodies, blots were washed thoroughly with TBS-T, incubated with SuperSignal West Dura chemiluminescent peroxidase substrate (Thermo Scientific), and exposed using FluorChem E System: Protein Simple.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

O.B.C. and A.V.G. are co-founders and shareholders of Everon Biosciences.

Acknowledgement

We thank Norman Sharpless for his gift of p16Ink4a/Luc mice.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant from Everon Biosciences to A.V.G.

Author contributions

DF and AVG jointly designed the study. DF and AVG authored the manuscript. DF, BH, ES and ASG developed analytical tools, performed experiments and analyzed data. VB and SV generated alginate capsules. LPV and MG performed animal husbandry and collected alginate bead and peritoneal lavage samples. OBC provided data interpretation analysis and critical revision of the manuscript.

References

- [1].Sharpless NE, Sherr CJ. Forging a signature of in vivo senescence. Nat Rev Cancer 2015; 15:397-408; PMID:26105537; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc3960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Childs BG, Baker DJ, Kirkland JL, Campisi J, van Deursen JM. Senescence and apoptosis: Dueling or complementary cell fates? EMBO Rep 2014; 15:1139-53; PMID:25312810; https://doi.org/ 10.15252/embr.201439245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res 1961; 25:585-621; PMID:13905658; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Childs BG, van de Sluis B, Kirkland JL, van Deursen JM. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature 2011; 479:232-6; PMID:22048312; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Baker DJ, Childs BG, Durik M, Wijers ME, Sieben CJ, Zhong J, Saltness RA, Jeganathan KB, Verzosa GC, Pezeshki A, et al.. Naturally occurring p16(Ink4a)-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature 2016; 530:184-9; PMID:26840489; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature16932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chang J, Wang Y, Shao L, Laberge RM, Demaria M, Campisi J, Janakiraman K, Sharpless NE, Ding S, Feng W, et al.. Clearance of senescent cells by ABT263 rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Nat Med 2016; 22:78-83; PMID:26657143; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.4010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Krishnamurthy J, Ramsey MR, Ligon KL, Torrice C, Koh A, Bonner-Weir S, Sharpless NE. p16INK4a induces an age-dependent decline in islet regenerative potential. Nature 2006; 443:453-7; PMID:16957737; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature05092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Burd CE, Sorrentino JA, Clark KS, Darr DB, Krishnamurthy J, Deal AM, Bardeesy N, Castrillon DH, Beach DH, Sharpless NE. Monitoring tumorigenesis and senescence in vivo with a p16(INK4a)-luciferase model. Cell 2013; 152:340-51; PMID:23332765; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hall BM, Balan V, Gleiberman AS, Strom E, Krasnov P, Virtuoso LP, Rydkina E, Vujcic S, Balan K, Gitlin I, et al.. Aging of mice is associated with p16(Ink4a)- and beta-galactosidase-positive macrophage accumulation that can be induced in young mice by senescent cells. Aging (Albany NY) 2016; 8:1294-315; PMID:27391570; https://doi.org/ 10.18632/aging.100991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Veiseh O, Doloff JC, Ma M, Vegas AJ, Tam HH, Bader AR, Li J, Langan E, Wyckoff J, Loo WS, et al.. Size- and shape-dependent foreign body immune response to materials implanted in rodents and non-human primates. Nat Mater 2015; 14:643-51; PMID:25985456; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nmat4290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Frescas D, Roux CM, Aygun-Sunar S, Gleiberman AS, Krasnov P, Kurnasov OV, Strom E, Virtuoso LP, Wrobel M, Osterman AL, et al.. Senescent cells expose and secrete an oxidized form of membrane-bound vimentin as revealed by a natural polyreactive antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017; 114:E1668-77; PMID:28193858; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1614661114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pilling D, Fan T, Huang D, Kaul B, Gomer RH. Identification of markers that distinguish monocyte-derived fibrocytes from monocytes, macrophages, and fibroblasts. PLoS One 2009; 4:e7475; PMID:19834619; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0007475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Duran-Struuck R, Dysko RC. Principles of bone marrow transplantation (BMT): Providing optimal veterinary and husbandry care to irradiated mice in BMT studies. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 2009; 48:11-22; PMID:19245745 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Davalos AR, Kawahara M, Malhotra GK, Schaum N, Huang J, Ved U, Beausejour CM, Coppe JP, Rodier F, Campisi J. p53-dependent release of Alarmin HMGB1 is a central mediator of senescent phenotypes. J Cell Biol 2013; 201:613-29; PMID:23649808; https://doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201206006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Whitfield ML, George LK, Grant GD, Perou CM. Common markers of proliferation. Nat Rev Cancer 2006; 6:99-106; PMID:16491069; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc1802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Starborg M, Gell K, Brundell E, Hoog C. The murine Ki-67 cell proliferation antigen accumulates in the nucleolar and heterochromatic regions of interphase cells and at the periphery of the mitotic chromosomes in a process essential for cell cycle progression. J Cell Sci 1996; 109(Pt 1):143-53; PMID:8834799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Carbonneau CL, Despars G, Rojas-Sutterlin S, Fortin A, Le O, Hoang T, Beausejour CM. Ionizing radiation-induced expression of INK4a/ARF in murine bone marrow-derived stromal cell populations interferes with bone marrow homeostasis. Blood 2012; 119:717-26; PMID:22101896; https://doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2011-06-361626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Le ON, Rodier F, Fontaine F, Coppe JP, Campisi J, DeGregori J, Laverdiere C, Kokta V, Haddad E, Beausejour CM. Ionizing radiation-induced long-term expression of senescence markers in mice is independent of p53 and immune status. Aging Cell 2010; 9:398-409; PMID:20331441; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00567.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Robles SJ, Adami GR. Agents that cause DNA double strand breaks lead to p16INK4a enrichment and the premature senescence of normal fibroblasts. Oncogene 1998; 16:1113-23; PMID:9528853; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1201862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang Y, Schulte BA, LaRue AC, Ogawa M, Zhou D. Total body irradiation selectively induces murine hematopoietic stem cell senescence. Blood 2006; 107:358-66; PMID:16150936; https://doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Salic A, Mitchison TJ. A chemical method for fast and sensitive detection of DNA synthesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:2415-20; PMID:18272492; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0712168105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.