Abstract

Optimal social interactions can leave people feeling socially connected and at ease, which has clear implications for health and psychological well-being. Yet, not all social interactions leave people feelings at ease and connected. What explains this variability? We draw from the egosystem-ecosystem theory of social motivation (Crocker & Canevello, 2008) to suggest that compassionate goals to support others explain some of this variability. We explored the nature of this association across 4 studies and varying social contexts. Across studies, compassionate goals predicted greater feelings of ease and connection. Results also indicate that a cooperative mindset may be one mechanism underlying this association: Findings suggest a temporal sequence in which compassionate goals lead to cooperative mindsets, which then lead to feeling at ease and connected. Thus, these studies suggest that people’s compassionate goals lead to their sense of interpersonal ease and connection, which may ultimately have implications for their sense of belonging.

Keywords: Compassionate goals, social interactions, cooperative mindset, social connection

People are social animals (e.g., Epley & Schroeder, 2014; Tomasello, 2014). They form connections easily and are reluctant to sever existing social ties (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Feeling socially connected predicts psychological well-being (e.g., Kawachi & Berkman, 2001; Seeman, 2000; Thoits, 2011). For example, larger social networks and more close relationships are related to fewer symptoms of depression (e.g., Barnett & Gotlib, 1988; Seeman, 2000), better physical health, and delayed mortality (e.g., Cohen, 2004; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010; House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988; Jetten, Haslam, & Haslam, 2012; Seeman, 2000; Uchino, 2004). On the other hand, those who lack social ties or feel lonely or isolated have poor psychological well-being (e.g., Cacioppo, Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2006), experience poor physical health, and are at greater risk of early death (e.g., Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris, & Stephenson, 2015; Seeman, 2000; Steptoe, Owen, Kunz-Ebrecht, & Brydon, 2004).

Given the benefits of feeling connected to others and negative consequences that come with feeling isolated, it may seem that social situations are inherently beneficial because they provide opportunities for connecting with others: Even seemingly inconsequential social interactions can provide a sense of connection and belonging (Walton, Cohen, Cwir, & Spencer, 2012). However, social situations are sometimes uncomfortable and hinder feelings of ease and connection. For example, when people fear judgment, they show signs of unease and isolation during social interactions – they express less warmth and interest (Alden & Wallace, 1995), self-disclose less (Luster, Nelson, & Busby, 2013), say fewer words (Cheek & Buss, 1981; Pilkonis, 1977), and interpret interaction partners as more negative (Nikitin & Freund, 2015). These feelings of social discomfort are not limited to interactions with strangers; interactions with close others, including romantic partners, can also thwart feelings of connection and belonging. For example, those who fear social evaluation see romantic intimacy as risky and view their romantic relationships as less intimate (Porter & Chambless, 2014), which may contribute to lower levels of disclosure to partners and a tendency to express less empathy (Luster et al., 2013).

What explains the variability in people’s feelings of social ease and connection? We suggest that one answer may lie in interpersonal goals. The egosystem-ecosystem theory of social motivation (Crocker & Canevello, 2008, 2015) describes two motivational systems that energize behavior in interpersonal relationships. In this investigation we draw from their conception of ecosystem motivation, in which behaviors and intentions are driven by concern for the well-being of others in addition to the self. Specifically, we argue that compassionate goals, which stem from ecosystem motivation, lead people to feel at ease and connected in social interactions.

Ecosystem Motivation, Compassionate Goals, and Feeling at Ease and Connected During Interactions

According to the egosystem-ecosystem theory of social motivation, people who have an ecosystem motivational orientation care about the well-being of others, in addition to the self (Crocker & Canevello, 2012). They view the self as part of a larger interpersonal system of interconnected individuals whose actions have consequences for others and assume that their interests are aligned with the interests of others in their social worlds. The system and the individuals within it thrive when the needs of all individuals in the system are met. Ecosystem motivational orientation is characterized by having compassionate goals to support others; these goals have important implications for how people construe others in relation to the self and feeling at ease and connected during interactions. According to the theory, when people are in the ecosystem and have compassionate goals, they view their relationships as working in nonzero-sum ways, such that what is good for one person can be good for others in the system and vice versa (Crocker, Canevello, & Lewis, 2015) and their interactions with others should be characterized by feelings of ease and connection (Crocker & Canevello, 2012).

Empirical evidence provides some preliminary support for these hypotheses. When people have compassionate goals, they construe their relationships in nonzero-sum or win-win terms (Crocker & Canevello, 2008; Crocker, Canevello, & Lewis, 2015). Further, compassionate goals correlate with feeling at ease and connected during interactions with others (Crocker & Canevello, 2008). However, previous findings do not address several key predictions of the egosystem-ecosystem theory of social motivation. The present studies test these predictions.

First, it is unclear how compassionate goals might lead to this affective state. Egosystem-ecosystem theory predicts that compassionate goals shape feelings of ease and connection in social situations in part because when ecosystem motivation is activated, people feel aligned with others; they assume that their goals to be supportive and constructive and not harm others are compatible with others’ goals. Specifically, compassionate goals foster a mindset in which people feel collaborative and cooperative with others, which in turn fosters feelings of social ease and connection (i.e., feeling clear, connected, peaceful, and loving). Consequently, we predict that compassionate goals predict a collaborative mindset indicated by feeling cooperative in social interactions, which in turn predicts feeling at ease and connected (i.e., clear, connected, peaceful, and loving).

Second, existing findings do not address the temporal order of associations between compassionate goals, cooperative mindset, and feelings of social ease and connection. Egosystem-ecosystem theory predicts a temporal sequence in which compassionate goals predict increased cooperative mindset during interactions, which in turn predict increased feelings of ease and connection. Demonstrating this sequence would provide support for egosystem-ecosystem theory, pointing to compassionate goals as a starting point for people’s feelings of comfort regarding social situations. It is also possible that increased feelings of ease and connection may then reinforce compassionate goals, thus suggesting an upward spiral of compassionate goals and feelings of ease and connection.

Third, previous findings do not address whether compassionate goals specifically predict feelings of ease and connection, or more generally predict positive affect, of which feelings of ease and connection are simply a part. Egosystem-ecosystem theory suggests that compassionate goals specifically predict a particular form of positive affect—feelings of ease and connection—but this has not been directly tested in previous research. Perhaps people with compassionate goals experience general positive affect or several different types positive affect; there may be no special or unique association between compassionate goals and feelings of ease and connection in interactions. Demonstrating that compassionate goals are uniquely related to feelings of social ease and connection independent of other types of positive affect would suggest that compassionate goals are not simply due to feeling good, but instead specifically predict feelings that signal connection to and alignment with others.

In addition to testing these key predictions of the theory, it is also important to rule out other factors that may account for the association between compassionate goals and feelings of social ease and connection. Extraverts, who seek out social situations, tend to experience greater contentment and love (Shiota, Keltner, & John, 2006), whereas those higher in emotional instability tend to experience greater fear in social situations (e.g., Larsen & Ketelaar, 1991). Trait loneliness may spill over into interactions with relationship partners, contributing to these feelings. When people have low self-esteem, they may question their relational value (Leary, 2005) or doubt their partner’s regard for them (Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 2000), which may prompt them to feel less clear, peaceful, connected and loving. Relationship-specific insecurities may lead people to worry about their partner’s regard for them and whether their partner desires the same level of closeness as they would like and may lead people to feel less at ease or connected to partners (e.g., Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Murray & Derrick, 2005), whereas feeling secure in close relationships may foster clear and connected feelings. Conflicts such as arguments or disagreements may cause people to feel less at ease and connected when interacting with others if the conflicts prompt questions about how accommodating to be, or whether the costs of the relationship outweigh the benefits (e.g., Rusbult, Verette, Whitney, Slovik, & Lipkus, 1991). Given that many of these constructs are also related to compassionate goals (Canevello & Crocker, 2011; Canevello, Granillo, & Crocker, 2013; Crocker & Canevello, 2008), it is possible that one or more of these factors might account for associations between compassionate goals and feelings of ease and connection. The present studies test this possibility.

Egosystem-ecosystem theory suggests that people adopt a cooperative mindset and feel at ease and connected as a function of their own compassionate goals, independent of the goals of the person or people with whom they interact. However, the literature on emotion contagion suggests that people’s emotions tend mirror those of interaction partners (Hatfield, Cacioppo, & Rapson, 1994) and that people can “catch” others’ emotional states. Thus, it is possible that the cooperative mindset and feelings of ease and connection that people experience when they have compassionate goals in social situations are explained by their interaction partners’ goals, cooperative mindset, or feelings of ease and connection, rather than their own compassionate goals to support others. Accordingly, the present studies test whether people feel at ease and connected due to their partners’ goals, cooperative mindset, or feelings of ease and connection.

Finally, it is unclear whether compassionate goals predict cooperative mindsets and peaceful, clear and connected feelings in all situations, or whether these associations emerge only in specific relationship situations. Do compassionate goals predict feeling at ease and connected in the context of negative relationship events? Do compassionate goals elicit these feelings in actual interactions or might compassionate goals be related to feeling at ease and connected in imagined interactions? The generality of this association remains unknown.

We addressed each of these issues across four studies. In Study 1 we address whether compassionate goals are uniquely related to feeling at ease with and connected to others, even controlling for general positive affect or other specific types of positive affect. In Study 1, we also address alternative explanations for the associations between compassionate goals and feelings of ease and connection. In Studies 2–4, we test cooperative mindset as the mechanism linking compassionate goals and feelings of ease and connection. In Studies 3 and 4, we test the temporal sequence of these associations. In Study 4, we also address whether the hypothesized associations between compassionate goals, cooperative mindset and feelings of ease and connection are explained by emotion contagion, in which people mirror the emotions of interaction partners. Finally, across all studies, we examine these associations in varied social contexts in order to understand under what interpersonal conditions they hold.

STUDY 1

Study 1 had three goals. The first was to replicate the association between compassionate goals and feelings of social ease and connection observed in previous research. Second, we examined the specificity of this association, testing whether compassionate goals relate specifically to feelings of social ease and connection when controlling for general positive affect and other flavors of positive affect, including joy, self-assurance, and attentiveness. The third goal of Study 1 was to test whether this association could be explained by other constructs previously shown to be related to affect when interacting with others, including extraversion, emotional instability, loneliness, self-esteem, rejection sensitivity, anxious and avoidant attachment to romantic partners, and conflict in the relationship. We tested these associations in a study of individuals who were asked to record feedback about their partners’ strengths and weaknesses. This allowed us to determine whether compassionate goals were associated with at feeling of social ease and connection when participants merely imagined the presence of interaction partners. Thus, we eliminated any effects that partners might have on participants’ affective states during the study.

Method

Participants

One hundred sixty five college students (77% female) who were currently in romantic relationships volunteered for a laboratory study of relationships and health. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 34 years (M = 19.45, SD = 2.3). Eighty-two percent of participants reported their race as White/Caucasian, 12% were Asian, 7% were African American/Black, 1% were American Indian/Alaska Native, and 3% reported their race as “Other” (participants were able to indicate more than one racial category); 7% were Hispanic or Latina(o). Participants had been in their current relationships for between 18 days and 11.36 years (M = 1.53 years, SD = 1.42 years); 82% were exclusively dating their partners, 11% were nearly engaged, 4% were engaged, 2% were casually dating, 1% were married, and 2% did not report their involvement in their romantic relationships.

Procedure

Before coming to the lab, participants completed an online survey, which included measures of extraversion, emotional instability, loneliness, self-esteem, rejection sensitivity, demographic information, and other measures unrelated to the goals of the present study. They were then scheduled for individual lab sessions. When they arrived at the lab, participants reported their anxious and avoidant attachment to partners and conflict in their relationships. Then, they read the following instructions: “Everyone has strengths and weaknesses. We are interested in what you think your romantic partner’s strengths and weaknesses are AS A ROMANTIC PARTNER. Please think about his or her most important strengths and weaknesses—those that affect the quality of your relationship for better or worse, or those that affect how you personally feel about the relationship. These could be things that you have not discussed or rarely discuss with your partner. They could also be things that you have discussed before. Answer the following questions about your partner’s most important strengths and weaknesses as a relationship partner.” Participants then listed their partners’ strengths and weaknesses and rated each with respect to their importance (i.e., “How important are these strengths to you?”) whether they had discussed these qualities with partners (i.e., “How much have you discussed these strengths/weaknesses with your partner before?”) and the effects of these qualities on relationship quality (i.e., “How do these strengths/weaknesses affect the quality of your relationship with your partner?”). These items were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all important/never/no effect on my relationship) to 5 (extremely important/very frequently/strong positive effect on my relationship/strong negative effect on my relationship). Half of participants listed strengths and then weaknesses; half of participants listed weaknesses and then strengths. Again, additional measures unrelated to the present study were included. After they completed these questionnaires, they were taken to a room equipped with a video camera and given the following instructions: “… we asked you to identify your partner’s most important strengths and weaknesses. I’d like you to spend the next five minutes recording feedback while imagining you are talking to your partner. Although your partner is not here right now, please try to imagine that you were giving this feedback to your partner face-to-face. The feedback does not have to be given in any order; feel free to talk about only strengths or weaknesses or both.” After the feedback session, participants reported their compassionate goals while recording the feedback and their feelings of ease and connection and positive affect after the feedback session.

Primary Measures

Compassionate goals while giving feedback were measured using a scale derived from Crocker and Canevello (2008). Items began with the stem, “While giving the feedback, I wanted/tried to:” Seven items were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), and included: “Have compassion for my partner’s mistakes and weaknesses,” “Be supportive of my partner,” “Be constructive in my comments to my partner,” “Avoid being selfish or self-centered,” “Avoid saying anything that would be harmful to my partner,” “Be aware of the impact the feedback might have on my partner’s feelings,” and “Make a positive difference in my partner’s life” (α = .80).

Feeling at ease and connected was also measured after the feedback session. Items began with the stem “How did you feel while recording your feedback for your partner?” were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much), and included “clear,” “connected,” “peaceful,” and “loving” (α = .79).

Covariate Measures

Positive affect was measured after the feedback session using scales from the PANAS-X (Watson & Clark, 1994). Items began with the stem “How did you feel while recording your feedback for your partner?” and were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). General positive affect items included “alert,” “attentive,” “determined,” “enthusiastic,” “excited,” “proud,” and “strong” (α = .85). Joviality items included “happy,” “joyful,” “delighted,” “cheerful,” “excited,” “enthusiastic,” “lively,” and “energetic” (α = .95). Attentiveness items included “alert,” “attentive,” “concentrating,” and “determined” (α = .78). Self-assurance items included “proud,” “strong,” “confident,” “bold,” “daring,” and “fearless” (α = .84).

Extraversion and emotional instability were measured in the online pretest using subscales from the Big 5 Inventory (John & Srivastava, 1999). Items began with the stem “In the past two weeks, I have:” and were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Extraversion items included “Been talkative,” “Been reserved” (reversed), “Been full of energy,” “Generated a lot of enthusiasm,” “Tended to be quiet” (reversed), “Had an assertive personality,” “Been sometimes shy, inhibited” (reversed), and “Been outgoing, sociable” (α = .85). Items assessing emotional instability included “Been depressed, blue,” “Been relaxed, handled stress well” (reversed), “Been tense,” “Worried a lot,” “Been emotionally stable, not easily upset” (reversed), “Could have been moody,” “Remained calm in tense situations” (reversed), and “Gotten nervous easily” (α = .87).

Loneliness was measured in the online pretest using the short version of the UCLA loneliness scale (Russell, 1996). Three items began with the stem “Indicate how often you have felt each of the following in the past 2 weeks” and were rated on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (often). Items included “I felt as if nobody really understands me,” “I felt completely alone,” and “I felt isolated from others.” These items had adequate internal reliability in these data (α = .79).

Self-esteem was measured in the online pretest using a shortened version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). Five items began with the stem: “Over the past 2 weeks:” and were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items included “All in all, I was inclined to feel that I am a failure” (reversed), “I took a positive attitude with myself,” “On the whole, I was satisfied with myself,” “At times I thought I was no good at all” (reversed), and “I felt that I have a number of good qualities.” These items had good internal reliability in these data (α = .91).

Rejection sensitivity was measured in the online pretest using the measure from Downey and Feldman (1996). Participants read 18 scenarios in which rejection by others was possible and rated how concerned or anxious they would feel (1= very unconcerned; 5 = very concerned) and the likelihood of being rejected in each scenario (1= very unlikely; 5 = very likely). For each scenario, anxiety and likelihood ratings were multiplied and averaged. This scale had good internal reliability (α = .83).

Anxious and avoidant attachment were measured in the lab before the feedback session using a shortened version of the Brennan, Clark, and Shaver (1998) two-dimensional scale assessing insecure romantic attachment. We included the 9 highest-loading items from each subscale reported by Brennan and colleagues (Brennan et al., 1998) and participants indicated their level of agreement with each item on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). All items began with the phrase, “Over the past 2 weeks in my romantic relationship:” Sample items assessing relationship anxiety included “I worried a fair amount about losing my partner” and “I worried that my partner won’t care about me as much as I care about him/her” (α = .91); sample items assessing relationship avoidance included “Just when my partner started to get close to me I found myself pulling away” and “I wanted to get close to my partner, but I kept pulling back” (α = .87).

Relationship conflict was assessed in the lab before the feedback session with 8 items preceded by: “Please indicate the extent to which each of the following has occurred in the past two weeks,” with items rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Items included “You fought with your partner,” “You had a disagreement with your partner,” “You were upset with your partner,” “You and your partner had to iron-out differences,” “You became openly angry with your partner,” “You felt like screaming at your partner,” “You and your partner criticized each other,” and “You got so angry with your partner that you threw things” (α = .88).

Results

We began by testing the association between compassionate goals and feeling at ease and connected: results replicated previous findings suggesting that compassionate goals were positively related to feeling at ease and connected, b = .59, SE = .10, t(159) = 5.80, 95% CI [.39, .79], r = .42, p < .001. Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations for compassionate goals and feeling at ease and connected across all studies.

Table 1.

Zero-Order Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for All Study 1 Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Compassionate Goals | 3.77 (.68) | |||||||||||||

| 2. Feeling at Ease and Connected | .413 | 3.30 (.96) | ||||||||||||

| 3. General Positive Emotion | .353 | .813 | 2.57 (.88) | |||||||||||

| 4. Joviality | .262 | .713 | .933 | 2.30 (1.05) | ||||||||||

| 5. Attentiveness | .383 | .683 | .793 | .553 | 3.02 (.95) | |||||||||

| 6. Self-Assurance | .353 | .803 | .933 | .763 | .743 | 2.62 (.92) | ||||||||

| 7. Extraversion | .212 | .293 | .303 | .283 | .222 | .293 | 3.33 (.71) | |||||||

| 8. Emotional Instability | −.171 | −.242 | −.14 | −.201 | −.04 | −.08 | −.433 | 2.93 (.82) | ||||||

| 9. Loneliness | −.181 | −.272 | −.222 | −.232 | −.14 | −.181 | −.343 | .413 | 1.86 (.89) | |||||

| 10. Self-Esteem | .252 | .303 | .272 | .273 | .161 | .242 | .453 | −.583 | −.663 | 4.02 (.81) | ||||

| 11. Rejection Sensitivity | −.08 | −.161 | −.15 | −.10 | −.212 | −.15 | −.262 | .242 | .272 | −.313 | 6.48 (2.22) | |||

| 12. Anxious Attachment | −.02 | −.171 | −.13 | −.202 | .00 | −.07 | −.202 | .383 | .393 | −.433 | .393 | 2.17 (.89) | ||

| 13. Avoidant Attachment | −.201 | −.333 | −.222 | −.232 | −.10 | −.232 | −.171 | .222 | .333 | −.283 | .171 | .363 | 1.58 (.59) | |

| 14. Relationship Conflict | −.12 | −.181 | −.08 | −.14 | .05 | −.04 | −.02 | .293 | .353 | −.283 | .171 | .413 | .283 | 1.72 (.58) |

Note. N = 165. Rejection sensitivity scores ranged from 1.22 to 11.56 in this sample; all other measures were rated on scales from 1 (not at all/strongly disagree/never) to 5 (very much/strongly agree/very often).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Next, we tested whether compassionate goals are uniquely associated with feeling at ease and connected, independent of other specific types of positive affect or general positive affect. We examined these associations in two ways. First, we tested whether the association between compassionate goals and feeling at ease and connected remained significant when we controlled for general positive affect, joviality, self-assurance, and attentiveness. This association remained significant when we controlled for these variables (see Table 2), suggesting that the association between compassionate goals and feeling at ease and connected is not due to general positive affect or other specific types of positive affect.

Table 2.

Standardized Regression Coefficients for Compassionate Goals Predicting At Ease/ Connected Feelings in Study 1, Controlling for Other Positive Affect.

| DV: Feeling at ease and connected | Compassionate Goals | Covariate |

|---|---|---|

| Without a covariate | .45*** | |

| With a Covariate: | ||

| General Positive Emotion | .15** | .76*** |

| Joviality | .25*** | .64*** |

| Attentiveness | .19** | .61*** |

| Self-Assurance | .16** | .75*** |

Note:

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

In a second set of analyses, we examined whether feeling at ease and connected explained associations between compassionate goals and other positive affect. As shown in the first column of Table 3, compassionate goals were positively related to general positive affect, joviality, attentiveness, and self-assurance. The magnitude of these associations dropped dramatically to become nonsignificant when we included feeling at ease and connected as a covariate (see columns 2 and 3 of Table 3). Together, these findings suggest that compassionate goals are specifically related to affective states that signal a sense of ease with and connection to others.

Table 3.

Standardized Regression Coefficients for Compassionate Goals Predicting Positive Affect, Controlling for Feeling at Ease and Connected in Study 1.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Compassionate Goals | Compassionate Goals | Feeling at ease and connected | |

|

| |||

| DV: | β | β | β |

| General Positive Affect | .35*** | .01 | .81*** |

| Joy | .26** | −.05 | .73*** |

| Self-Assurance | .35*** | .02 | .79*** |

| Attentiveness | .38*** | .12 | .63*** |

Note:

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Next, we examined whether the association between compassionate goals and feeling at ease and connected could be explained by other constructs previously shown to be related to affect when interacting with others, including extraversion, emotional instability, loneliness, self-esteem, rejection sensitivity, anxious and avoidant attachment to romantic partners, and conflict in the relationship. The association between compassionate goals and feeling at ease and connected remained significant when we controlled for each of these measures in separate analyses (see Table 4), suggesting that these individual difference and qualities of the relationship do not account for the association between compassionate goals and feeling at ease and connected.

Table 4.

Standardized Regression Coefficients for Compassionate Goals Predicting Feeling at Ease and Connected in Study 1, Controlling for Alternative Explanations.

| DV: Feeling at ease and connected | Compassionate Goals | Covariate |

|---|---|---|

| Without a covariate | .42*** | |

| With a Covariate: | ||

| Extraversion | .37*** | .21** |

| Emotional Instability | .39*** | −.17* |

| Self-Esteem | .37*** | .21** |

| Rejection Sensitivity | .41*** | −.13 |

| Loneliness | .38*** | −.20** |

| Anxious Attachment | .41*** | −.16* |

| Avoidant Attachment | .37*** | −.25** |

| Relationship Conflict | .40*** | −.13 |

Note:

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05. Coefficients reported are betas.

Finally, it was possible that participants’ feelings of ease and connection were related to the importance of the strengths and weaknesses that they listed, with more important strengths and less important weaknesses relating to a greater sense of ease and connection. It was also possible that those who reported greater ease and connection discussed partners’ strengths and not their weaknesses. Finally, participants’ feelings of ease and connection may have been related to perceiving that strengths had a greater effect on relationship quality and that weaknesses had a weaker effect on relationship quality. To examine whether these variables could explain associations between compassionate goals and feelings of ease and connection, we conducted 6 separate analyses, regressing feeling at ease and connected onto compassionate goals, controlling for the importance of the strengths and weaknesses listed by participants, how much participants had discussed the strengths and weaknesses with partners, and the estimated effects of these strengths and weaknesses on relationship quality. Across analyses, the association between compassionate goals and feeling at ease and connected remained unchanged when we accounted for these alternative explanations (.36 ≤ Beta ≤ .42).

Study 1 Discussion

This study replicates and extends previous research by demonstrating that compassionate goals are not simply associated with feeling good, instead, they are specifically associated with affective states that signal belonging. Compassionate goals relate to a specific type of positive affect: feeling at ease with and connected to others. Compassionate goals predicted feeling at ease and connected, beyond their association with general positive affect or other related specific types of positive affect (i.e., joviality, attentiveness, and self-assurance). Also, these goals are related to general positive affect and other related specific types of positive affect, but only through their association with feeling at ease and connected. Together these findings rule out the possibility that feelings of social ease and connection associated with compassionate goals simply reflect associations between compassionate goals and higher-order general positive affect. Instead, these findings pinpoint feeling of ease and connection as a unique affective state associated with compassionate goals. Compassionate goals lead people to feel at ease and connected to others in social contexts. These feelings of social ease and connection are distinct from other types of positive affect.

We also ruled out a number of alternative explanations for these associations. The study design (i.e., recording feedback for partners who were not present) allowed us to eliminate any influence that partners might have had on participants’ affective states. Links between compassionate goals and feelings of social ease and connection remained significant when we accounted for individual differences and relationship constructs previously shown to predict similar affect, including extraversion, emotional instability, self-esteem, rejection sensitivity, anxious and avoidant attachment, and relationship conflict. Further, these associations remained significant when we accounted for the importance of the strengths and weaknesses that participants listed, how much they had discussed these strengths and weaknesses with partners before, or the effects of these strengths and weaknesses on relationship quality

STUDY 2

In Study 2, we tested the process that might account for the association between compassionate goals and feelings of ease and connection. Specifically, we tested whether compassionate goals predict greater cooperative mindset, which in turn predicts greater feelings of ease and connection. We tested this model in the context of important relationship stressors in romantic relationships: after a partners’ transgression and after committing a transgression against a partner. We tested both of these contexts to explore whether our model holds both when participants were the victims (i.e., hurt by their partners) and when they were the perpetrator (i.e., hurt their partners). In this study, participants came to the lab with their partners, but couple members did not interact during the session, to control for partners’ influence on participants’ affective states. Further, following Study 1, we tested these associations controlling for self-esteem, and anxious and avoidant attachment.

Method

Participants

Sixty-two romantic couples, including one lesbian couple, completed a 1-hour lab session. Seventy-five percent of participants reported their race as White or European-American, 9% as Asian or Asian-American, 3% as Black or African-American, 3% Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, 7% selected other, and 4% did not report their race. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 53 years (M = 12.74.2 years, SD = 5.49 years). Six percent of couples were casually dating, 86% were exclusively dating, 2% were engaged, 5% were married, and 1% did not report their relationship status. Couples had been together for between 1 month and 33 years (M = 2.5 years; SD = 4.1 years).

Procedure

During lab sessions, members of each couple were seated in separate rooms to complete identical sets of questionnaires. First, participants reported their self-esteem and anxious and avoidant attachment and wrote about the last time their partners had hurt them. They then reported their compassionate goals toward their partner when they thought about that event and their cooperative mindset and feelings of ease and connection toward their partners since the event. After participants completed questions concerning their reactions to partners’ transgressions, they wrote a description of the hurtful event on a notecard. We gave these notecards to the other member of the couple and asked them to report their compassionate goals for their partners when they thought about that event and their cooperative mindset and feelings toward partners since the event. Thus, all participants provided separate reports of two events: they reported their compassionate goals, cooperative mindset, and affect related to the time when their partners had hurt them (i.e., when they were victims) and a second set of measures that referred to the time that their partners had reported being hurt by them (i.e., when they were perpetrators). Participants reported transgressions that had occurred an average of 4.3 months (SD = 8.4 months) before participating in the study (range = 1 day to 4 years). Participants rated these transgressions as moderately hurtful (i.e., M = 3.69, SD = 1.19 on a scale from 1(not at all) to 5 (extremely).

Measures

Compassionate goals for partners were measured using a measure derived from Crocker and Canevello (2008). Eight items began with the stem, “When you think about this event, how much does it make you want/try to do each of the following in your relationship,” and were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), and included: “Be supportive of my partner,” “Be aware of the impact my behavior might have on my partner’s feelings,” “Have compassion for my partner’s mistakes and weaknesses,” “Avoid being selfish or self-centered,” “Avoid neglecting my relationship with my partner,” “Avoid doing anything that would be harmful to my partner,” “Make a positive difference in my partner’s life,” and “Be constructive in my comments to my partner.” This measure had adequate internal reliability when participants thought about a time when they were victims (α = .85) and perpetrators (α = .84).

Cooperative mindset when interacting with partners was measured for both types of events. Participants rated “Since that event, when you interact with your partner, how much do you feel cooperative?” This item was rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Feeling at ease and connected when interacting with partners was also measured for both types of events. Again, items began with the stem “Since that event, when you interact with your partner, how much do you feel,” and were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Items were identical to those from Study 1. This measure had adequate internal reliability when participants thought about a time when they were victims (α = .76) and perpetrators (α = .70).

Self-esteem was measured using a shortened version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). Participants rated their agreement with five items on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items included “I feel that I’m a person of worth, at least on an equal basis with others,” “All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure” (reversed), “I feel I do not have much to be proud of” (reversed) “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself,” and “At times I think I am no good at all” (reversed).” These items had good internal reliability in these data (α = .86).

Anxious and avoidant attachment were measured using the scale described in Study 1 All items began with the phrase, “In my romantic relationship:” and were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Both scales had adequate reliability in this sample (both αs = .84).

Results

Overview of Analyses

We conducted analyses in two phases. Phase 1 tested our hypothesized path models when participants reflected on a time when their partners had hurt them. In Phase 2, we tested our hypothesized path models when participants reflected on a time when they had hurt their partners. In both phases, we tested whether these effects could be explained by self-esteem or anxious or avoidant attachment. Table 5 shows the intraclass correlations, means, and standard deviations for all Study 2 variables.

Table 5.

Intraclass Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for All Study 2 Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | Victim M (SD) | Perpetrator M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Compassionate Goals | .64*** | .48*** | .42*** | .17 | −.07 | −.31** | 4.04 (.65) | 4.34 (.58) |

| 2. Cooperative Mindset | .56*** | .63*** | .51*** | .31** | −.34*** | −.50*** | 4.20 (.77) | 4.24 (.83) |

| 3. Feeling at Ease and Connected | .59*** | .59*** | .82*** | .38*** | −.35*** | −.43*** | 4.12 (.65) | 4.13 (.68) |

| 4. Self-Esteem | .24** | .35*** | .38*** | −.39*** | −.23* | 4.10 (.79) | ||

| 5. Anxious Attachment | −.17 | −.25** | −.28** | −.39*** | .28** | 2.32 (.81) | ||

| 6. Avoidant Attachment | −.44*** | −.38*** | −.43*** | −.23* | .28** | 1.53 (.57) |

Note. N = 62 dyads. Correlations for victims appear below the diagonal; correlations for perpetrators appear above the diagonal; correlations between victim and perpetrator roles appear on the diagonal. All measures were rated on scales from 1 (not at all/strongly disagree) to 5 (extremely/very much/strongly agree). Self-esteem and anxious and avoidant attachment are identical across roles.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

We accounted for the nonindependence of individuals within dyads in all analyses using the MIXED command in SPSS (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Coefficients in all models were derived from fixed-effects models using restricted maximum-likelihood estimation. Predictors were grand mean centered. Path models were tested sequentially, with a separate regression equation for each path. For each path, we regressed the outcome on the predictor(s), controlling for all variables preceding that path in the model. For all associations, we report partial correlations, which were calculated using the method described by Rosenthal and Rosnow (1991).

Phase 1: Participants as Victims

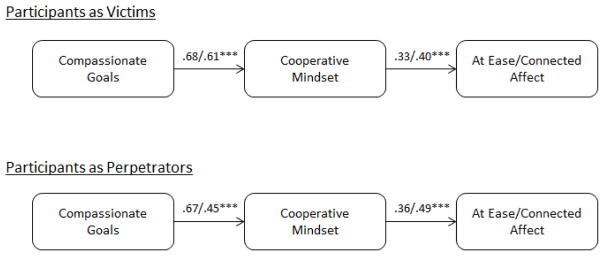

First, we tested our hypothesized path model when participants reflected on a time when their partners had hurt them. As shown in the top half of Figure 1, results supported our hypothesis: Compassionate goals predicted greater cooperative mindset, b = .68, SE = .08, t(109.12) = 8.00, 95% CI [.51, .84], pr = .61, p < .001, which in turn predicted greater ease with and connection to partners, b = .33, SE = .07, t(120.05) = 4.75, 95% CI [.19, .46], pr = .40, p < .001. Consistent with mediation, the indirect effect was significant (effect = .22, Sobel’s z = 4.08, p < .001.

Figure 1.

Unstandardized and standardized (i.e., partial correlations) path coefficients for models testing how participants’ compassionate goals for romantic partners predict their cooperative mindset toward romantic partners, which in turn led to at ease/ connected feelings toward romantic partners in Study 2. Path coefficients are estimated from separate multilevel models. *** p < .001.

We tested this path model three more times, each separately controlling for self-esteem, and anxious and avoidant attachment. Self-esteem was related to greater (b = .21, SE = .07, t(101.34) = 2.89, 95% CI [.07, .36], pr = .28, p = .005) and avoidant attachment was related to lower cooperative mindset (b = −.24, SE = .11, t(104.66) = −2.18, 95% CI [−.46, −.02], pr = −.21, p = .032); anxious attachment was unrelated to cooperative mindset (b = −.11, SE = .07, t(111.36) = −1.63, 95% CI [−.26, .03], pr = −.15, p = .105), however, in each analysis the association between compassionate goals and cooperative mindset remained significant (.61 ≥ bs ≤ .70, .52 ≥ prs ≤ .60, ps < .001). Additionally, self-esteem was related to greater (b = .14, SE = .06, t(88.16) = 2.51, 95% CI [.03, .25], pr = .24, p = .014) and anxious and avoidant attachment were related to lower ease with and connection to partners (anxious: b = −.14, SE = .05, t(101.81) = −2.53, 95% CI [−.24, −.03], pr = −.24, p = .013; avoidant: b = −.18, SE = .09, t(107.38) = −2.09, 95% CI [−.35, −.01], pr = −.20, p = .039), however the association between cooperative mindset and feeing at ease and connected to partners remained significant (.29 ≥ bs ≤ .31, .36 ≥ prs ≤ .38, ps < .001).

Phase 2: Participants as Perpetrators

Next, we tested our hypothesized path model when participants reflected on a time when they had hurt their partners. As shown in the bottom half of Figure 1, results supported our hypothesis: Compassionate goals predicted greater cooperative mindset, b = .67 SE = .11, t(106.12) = 6.25, 95% CI [.46, .89], pr = .45, p < .001, which in turn predicted greater feelings of ease with and connection to partners, b = .36 SE = .07, t(96.62) = 5.48, 95% CI [.23, .49], pr = .49, p < .001. Consistent with mediation, the indirect effect was significant (effect = .24, Sobel’s z = 4.12, p < .001).

We tested this path model again, controlling for self-esteem, and anxious and avoidant attachment separately in three sets of analyses. Self-esteem was related to greater (b = .21, SE = .08, t(104.10) = 2.49, 95% CI [.04, .38], pr = .24, p = .014) and anxious and avoidant attachment were related to lower cooperative mindset (anxious: b = −.29, SE = .08, t(114.87) = −3.61, 95% CI [−.44, −.13], pr = −.32, p < .001; avoidant: b = −.55, SE = .11, t(96.88) = −5.17, 95% CI [−.77, −.34], pr = −.46, p < .001). However, in each analysis the association between compassionate goals and cooperative mindset remained significant (.49 ≥ bs ≤ .65, .42 ≥ prs ≤ .49 ps < .001). Additionally, self-esteem was related to greater (b = .18, SE = .06, t(81.61) = 3.06, 95% CI [.06, .30], pr = .32, p = .003) and anxious attachment was related to lower ease with and connection to partners (b = −.18, SE = .05, t(92.73) = −3.35, 95% CI [−.29, −.07], pr = −.33, p = .001); avoidant attachment was unrelated to feelings of ease and connection to partners (b = −.15, SE = .09, t(102.82) = −1.66, 95% CI [−.33, .03], pr = −.16, p = .100). However, the association between cooperative mindset and feeing at ease and connected to partners remained significant (.30 ≥ bs ≤ .31, .39 ≥ prs ≤ .44, ps < .001).

Study 2 Discussion

Results from Study 2 provide support for our hypothesized process model: those with greater compassionate goals had more cooperative mindsets when they interacted with partners, which was associated with feeling more feeling at ease and connected when they interacted with partners. Compassionate goals directly predicted feeling at ease and connected. As in Study 1, these findings are consistent with egosystem/ecosystem theory’s assertion that feelings of ease with and connection to others follow from compassionate goals. Further, Study 2 findings suggest that cooperative mindset accounts for this association and that associations between compassionate goals and cooperative mindset and between cooperative mindset and feeling at ease and connected are not due to self-esteem or insecure attachment. Thus, these results support egosystem/ecosystem theory’s prediction that compassionate goals predict cooperative mindsets. The cooperative mindset associated with compassionate goals predicts feeling at ease with and connected to others.

Study 2 findings demonstrate that this process occurs in context of important romantic stressors, providing particularly compelling support for the emotional consequences of compassionate goals. These findings suggest that, even in the context of potentially damaging relational events, when people have compassionate goals, they can maintain or repair feelings of ease with and connection to partners. Thus, compassionate goals may be beneficial in close relationships precisely when they seem least likely to occur but are most needed.

These findings do not address the temporal sequence in which compassionate goals lead to cooperative mindsets, which in turn leads to feeling at ease with and connected to others. Also, Study 2 was conducted in a very specific social context –associations were examined in the context of personally significant relationships (i.e., romantic partners) over relatively impactful events. It is unclear whether these findings would replicate in the context of routine daily social interactions with others who are less personally relevant. We addressed these issues in Study 3.

STUDY 3

In Study 3 we tested the processes by which compassionate goals lead to feeling at ease and connected in everyday interactions with college roommates in a longitudinal daily diary study. This design allowed us to test the plausibility of the temporal sequence in which compassionate goals lead to increased cooperative mindset, which leads to increased feeling of ease and connection with roommates. It also allowed us to test whether increased feelings of ease and connection with roommates, in turn, reinforced later compassionate goals. In Study 3, we were able to determine whether Study 2 findings extend to more mundane, everyday interactions with arguably less close, less important others. Further, as in Study 1, we tested these associations controlling for self-esteem, conflict with roommates, loneliness, extraversion, emotional instability, and anxiety and avoidance in the roommate relationship.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Study 3 reports previously unpublished findings from the Roommate Goals Study (Canevello & Crocker, 2010, Study 2; Crocker & Canevello, 2008, Study 2). Sixty-five same-sex first-semester freshmen roommate dyads (71% female, 29% male) participated. Roommates completed surveys about the roommate relationship daily for 21 days; see Crocker and Canevello (2008) for a detailed description of the sample and procedures.

Primary Measures

Participants completed daily measures of compassionate goals, cooperative mindset, and feeling at ease and connected in their roommate relationships. Participants reported demographic information at the beginning of the study.

Compassionate goals for roommate relationships were assessed using the measure described in Study 2. Items began with the stem, “Today in my relationship with my roommate, I wanted/tried to:” All items referred to the roommate relationship and were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). This scale had high internal consistency each day of the study (compassionate goals: .91 < α < .97, Mα = .95).

Cooperative mindset when interacting with roommates was measured daily with the item “When you interacted with your roommate TODAY, to what extent did you feel cooperative.” This item was rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely).

Feeling at ease and connected when interacting with roommates was measured beginning with the stem: “When you interacted with your roommate TODAY, to what extent did you feel.” Items were identical to those used in Studies 1 and 2 and were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). This scale had adequate internal consistency each day of the study (.79 < α < .90, Mα = .86).

Covariates

Participants completed daily measures of self-esteem, conflict with roommates, and loneliness and pretest measures of extraversion, emotional instability, and roommate relationship anxiety and avoidance.

Self-esteem was measured daily using 4 items from the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). Participants rated their agreement with 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Items began with the stem “Today, to what extent did you feel” and included “that you are a person of worth,” “that you are a failure” (reversed), “satisfied with yourself,” and “that you are no good at all” (reversed).” These items had good internal reliability for each day of the study (.83 < α < .93, Mα = .90).

Anxiety and avoidance in the roommate relationship were measured at pretest using the scale described in Study 1. Items began with the stem: “In my relationship with my roommate:” and were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Items referred to the roommate relationship, for example, “I worry that my roommate won’t care about me as much as I care about him/her” and “Just when my roommate starts to get close to me I found myself pulling away.” Both of these scales demonstrated good internal reliability (anxious: α = .84; avoidant: α = .85).

Relationship conflict was assessed daily with a single item: “Did you have a disagreement or argument with your roommate today.” Responses were coded such that 1 = yes and 0 = no.

Loneliness was measured daily with a single item: “To what extent did you feel lonely today?” rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Extraversion and emotional instability were measured at pretest using the measure described in Study 1. Items began with the stem “I see myself as someone who:” and were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Both scales demonstrated good reliability in this sample (extraversion: α = .89; emotional instability: α = .86).

Results

Overview of analyses

We tested the plausibility of a temporal sequence in which compassionate goals predict increased cooperative mindset, which leads to increased feelings of ease with and connection to roommates in two ways. First, we tested this model within days, which allowed us to examine the relatively immediate impact of compassionate goals on cooperative mindset and subsequent at ease and connected feelings. We also tested whether these associations could be due to same-day reports of self-esteem, conflict with roommates, and loneliness. Second, using lagged analyses, we tested a model in which Day 1 compassionate goals predicted change in cooperative mindset from Days 1 to 2, which predicted change in feelings of ease with and connection to roommates from Days 1 to 3, which in turn predicted change in compassionate goals from Days 1 to 4 across four sequential days. Lagged-day analyses allowed us to determine whether compassionate goals have longer-lasting consequences for changes in cooperative mindsets and subsequent changes in at ease and connected feelings and future compassionate goals. In lagged-day analyses, we tested whether these associations could be due to daily reports of self-esteem, conflict with roommates, and loneliness, or with trait extraversion, emotional instability, or roommate relationship anxiety or avoidance.1

General analytic strategy

In these data, individuals were nested within dyads and dyads were crossed with days. We controlled for the nonindependence of individuals within dyads in all analyses using the MIXED command in SPSS (Kenny et al., 2006), and because individuals within dyads were indistinguishable, we specified compound symmetry so that intercept variances between dyad members were equal. Coefficients were derived from random-coefficients models using restricted maximum-likelihood estimation, and models included fixed and random effects for the intercept and each predictor. Path models were tested as described in Study 2. Means and standard deviations for study variables are shown in Table 1. Unstandardized and unstandardized (i.e., partial correlations) path coefficients from Study 3 path analyses are illustrated in Figure 2. Partial correlations were calculated using the method described by Rosenthal and Rosnow (1991).

Figure 2.

Unstandardized and standardized (i.e., partial correlations) path coefficients for models testing how participants’ compassionate goals for roommates predict their cooperative mindset toward roommates, which in turn led to feeing at ease/connected feelings toward roommates in Study 3. Path coefficients are estimated from separate multilevel models.*** p < .001.

Within-Day Analyses

First, we examined our hypothesized models within days, testing whether daily compassionate goals predicted cooperative mindset that same day, which then predicted feelings of ease with and connection to roommates that day. We person-centered all predictors so that scores represent differences from each individual’s own average across the 21 days (e.g., Enders & Tofighi, 2007; Kreft & de Leeuw, 1998; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). This design allowed us to remove the effects of individual differences in compassionate goals and cooperative mindset and examine within-person effects.

Path analyses supported our hypotheses within days (see the top of Figure 2). On days when students’ reported increased compassionate goals relative to their own average, they reported more cooperative mindsets that same day, b = .48, SE = .08, t(157.40) = 6.14, 95% CI [.32, .63], pr = .44, p < .001; on days when they reported more cooperative mindsets compared to their own averages, they also reported feelings more at ease with and connection to roommates that same day, b = .38, SE = .06, t(203.93) = 6.63, 95% CI [.27, .50], pr = .42, p < .001, controlling for their goals. Consistent with mediation, the indirect effect was significant (effect = .18, Sobel’s z = 4.50, p < .001).

We tested this path model again, controlling for self-esteem, loneliness, and roommate conflict separate analyses. All covariates were person-centered. Across analyses, only daily fluctuations in self-esteem predicted greater cooperative mindset that same day (b = .16, SE = .08, t(256.34) = 2.11, 95% CI [.01, .31], pr = .13, p = .036); neither loneliness nor roommate conflict were related to cooperative mindset (loneliness: b = .−.08, SE = .07, t(223.63) = −1.15, 95% CI [−.23, .06], pr = .08, p = .253; roommate conflict: b = .18, SE = .21, t(639.85) = .83, 95% CI [−.24, .60], pr = .03, p = .405). In each analysis, the association between daily compassionate goals and greater cooperative mindset remained significant (.47 ≥ bs ≤ .52, .40 ≥ prs ≤ .42, ps < .001). Additionally, daily self-esteem positively predicted ease with and connection to roommates that same day (b = .14, SE = .06, t(326.95) = 2.42, 95% CI [.03, .26], pr = .13, p = .016) and daily loneliness marginally predicted less ease and connection to roommates (b = −.11, SE = .06, t(294.56) = −1.85, 95% CI [−.22, .01], pr = .11, p = .066); daily roommate conflict was unrelated to feelings of ease and connection to roommates (b = .24, SE = .14, t(613.44) = 1.64, 95% CI [−.05, .52], pr = .06, p = .101). However the association between daily increases in cooperative mindset and feeing at ease and connected to roommates remained significant (.35 ≥ bs ≤ .39, .38 ≥ prs ≤ .42, ps < .001).

Lagged-Day Analyses

Next, we tested the lagged-day associations among compassionate goals, cooperative mindsets, and feelings of ease with and connection to roommates. These analyses allowed us to determine whether compassionate goals can have lasting consequences for cooperative mindsets and subsequent feelings of ease with and connection to roommates and, in turn, future compassionate goals across 4 days. Further, examination of the temporal sequence of effects across days does not demonstrate causality but can shed light on the plausibility or implausibility of causal pathways (Kenny, 1975; Rogosa, 1980; West, Biesanz, & Pitts, 2000). Evidence that Day 1 compassionate goals predict Day 2 cooperative mindset, controlling for Day 1 cooperative mindset (i.e., testing whether compassionate goals one day predict residual change in cooperative mindset the following day), would be consistent with the hypothesis that compassionate goals cause cooperative mindsets. No association would rule out a causal effect over this time period. Thus, lagged analyses test the temporal associations for each hypothesized pathway in our models, which speaks to the plausibility of causal associations.

We used a residual change strategy to test change by regressing Day N + 1 dependent variable on relevant Day N predictors, controlling for the Day N dependent variable. When change in a variable was a predictor, we entered the Day N and Day N + 1 predictors into the model and interpreted the Day N + 1 variable. We tested a path model in which Day 1 compassionate goals predict change in cooperative mindsets from Day 1 to Day 2, which predict change in feelings of ease with and connection to roommates from Day 1 to Day 3, which, in turn, predict change in compassionate goals from Day 1 to Day 4. For each path, we regressed the criterion on predictor(s), controlling for all variables preceding that path in the model. Lagged analyses were conducted on all possible 4-day sequences within the 21 days.

Path analyses support our hypotheses (see the bottom of Figure 2). Day 1 compassionate goals predicted increased cooperative mindsets toward roommates from Days 1 to 2, b = .20, SE = .04, t(143.67) = 4.72, 95% CI [.11, .28], pr = .37, p < .001, which predicted increased feelings of ease with and connection to roommates from Days 1 to 3, b = .22, SE = .03, t(164.77) = 8.62, 95% CI [.17, .28], pr = .56, p < .001. Increased feelings of ease with and connection to roommates from Days 1 to 3, in turn, predicted increased compassionate goals from Days 1 to 4, b = .18, SE = .03, t(276.70) = 5.62, 95% CI [.12, .24], pr = .32, p < .001.

We tested this lagged-day path model again, controlling for pretest extraversion, emotional stability, and roommate relationship anxiety and attachment in four sets of analyses. We also retested our hypothesized path model controlling for Day 1 self-esteem, loneliness, and conflict in test of the link between Day 1 compassionate goals and change in cooperative mindset from Days 1 to 2. We controlled for change in self-esteem, loneliness, and conflict from Days 1 to 2 in tests of the link between change in cooperative mindset from Days 1 to 2 and change in feeling at ease and connected from Days 1 to 3. We did this by including both Day 1 and Day 2 variables as covariates. Similarly, we controlled for change in self-esteem, loneliness, and conflict from Days 1 to 3 in tests of the link between change in feeling at ease and connected from Days 1 to 3 and change in compassionate goals from Days 1 to 4. We did this by including both Day 1 and Day 3 variables as covariates.

Across analyses, no covariates were related to change in cooperative mindset from Days 1 to 2 (pretest extraversion: b = −.05, SE = .03, t(502.90) = −1.68, 95% CI [−.12, .01], pr = −.07, p = .094; pretest emotional stability: b = .01, SE = .03, t(770.50) = .29, 95% CI [−.05, .07], pr = .01, p = .775; pretest relationship anxiety: b = −.00, SE = .02, t(751.90) = −.07, 95% CI [−.05, .05], pr = −.00, p = .945; pretest relationship avoidance: b = −.03, SE = .03, t(598.22) = −.25, 95% CI [−.09, .02], pr = −.05, p = .246; Day 1 self-esteem: b = −.00, SE = .04, t(158.73) = −.07, 95% CI [−.08, .08], pr = −.00, p = .942; Day 1 loneliness: b = −.02, SE = .04, t(138.81) = −.44, 95% CI [−.09, .06], pr = −.04, p = .660; Day 1 relationship conflict: b = −.31, SE = .18, t(1635.42) = −1.72, 95% CI [−.66, .04], pr = −.04, p = .086). In each analysis, the association between Day 1 compassionate goals and increased cooperative mindset from Days 1 to 2 remained significant (.19 ≥ bs ≤ .20, .34 ≥ prs ≤ .37, ps < .001).

Across analyses, relationship anxiety and change in self-esteem from Days 1 to 2 were marginally related to increased ease with and connection to roommates from Days 1 to 3 (relationship anxiety: b = .03, SE = .02, t(906.96) = 1.83, 95% CI [−.00, .07], pr = .06, p = .067; change in self-esteem: b = .06, SE = .03, t(376.91) = 1.84, 95% CI [−.00, .13], pr = .09, p = .067) but no other covariate was related to change in feeling at ease and connected with roommates from Days 1 to 3 (pretest extraversion: b = −.01, SE = .02, t(598.62) = −.43, 95% CI [−.06, .04], pr = −.02, p = .670; pretest emotional stability: b = .04, SE = .02, t(918.75) = 1.67, 95% CI [−.01, .08], pr = .05, p = .096; pretest relationship avoidance: b = −.02, SE = .02, t(721.62) = −1.01, 95% CI [−.06, .02], pr = −.04, p = .311; change in loneliness from Days 1 to 2: b = −.01, SE = .03, t(307.95) = −.47, 95% CI [−.08, .05], pr = −.03, p = .639; change in relationship conflict from Days 1 to 2: b = −.09, SE = .14, t(1615.69) = −.62, 95% CI [−.37, .19], pr = −.02, p = .537). Importantly, the association between change in cooperative mindset from Days 1 to 2 and increased feeling at ease and connected to roommates from Days 1 to 3 remained significant (.21 ≥ bs ≤ .23, .51 ≥ prs ≤ .56, ps < .001).

Of the covariates tested, only relationship avoidance predicted change in compassionate goals from Days 1 to 4 (b = −.05, SE = .02, t(788.24) = −2.15, 95% CI [−.09, −.00], pr = −.08, p = .032;) but no other covariates predicted change in compassionate goals from Days 1 to 4 (pretest extraversion: b = .05, SE = .03, t(576.20) = 1.75, 95% CI [−.01, .10], pr = .07, p = .081; pretest emotional stability: b = −.03, SE = .02, t(863.51) = −1.18, 95% CI [−.07, .02], pr = −.04, p = .238; pretest relationship anxiety: b = −.02, SE = .02, t(862.54) = −1.29, 95% CI [−.06, .01], pr = −.04, p = .197; change in self-esteem from Days 1 to 3: b = −.01, SE = .04, t(408.97) = −.33, 95% CI [−.08, .06], pr = −.02, p = .745; change in loneliness from Days 1 to 3: b = .04, SE = .03, t(344.35) = 1.30, 95% CI [−.02, .10], pr = .07, p = .196; change in relationship conflict from Days 1 to 3: b = −.03, SE = .15, t(1893.11) = −.22, 95% CI [−.33, .26], pr = −.01, p = .823). Importantly, the association between change in feeling at ease and connected to roommates from Days 1 to 3 and increased compassionate goals from Days 1 to 4 remained significant (.18 ≥ bs ≤ .21, all prs = .32, ps < .001).

Study 3 Discussion

Study 3 findings provide support for a temporal sequence in which compassionate goals predict cooperative mindsets when interacting with others, which in turn predict feeling at ease and connected in these interactions. Feeling at ease and connected in social interactions then reinforced future compassionate goals. This process occurs relatively quickly. Results from within-day analyses suggested that on days when students had higher compassionate goals they had more cooperative mindsets; on days when students had more cooperative mindsets when interacting with roommates, they also had felt more at ease and connected during those interactions. As in previous studies, compassionate goals directly predicted feeling at ease and connected and this association was partially accounted for by cooperative mindset. Further, these associations were not due to individual differences in compassionate goals or cooperative mindset. Because these analyses involve within-person changes, they allow us to test our hypotheses while removing the potential influence of individual differences.

These effects also persisted across four days, suggesting that people’s compassionate goals not only set the stage for affect when interacting with others that same day, they also have lasting consequences for affect when interacting with roommates and for own compassionate goals several days later. Importantly, these lagged-day findings test change over time, consistent with the possibility that compassionate goals cause cooperative mindset, which in turn cause feeling at ease and connected when interacting with roommates, which then caused increased compassionate goals. Further, Study 3 findings from lagged analyses suggest that these associations are not due to self-esteem, conflict with roommates, or loneliness on relevant days or changes in these constructs on relevant days; these associations are also not explained by trait extraversion, emotional instability or relationship anxiety or avoidance.

Notably, Study 3 findings demonstrated that these associations hold in newly developing relationships between college roommates over time. Thus, these associations are not unique to romantic relationships – they also occur in less close, typically less important relationships.

STUDY 4

Studies 1–3 provide support for the idea that compassionate goals predict feeling more at ease and connected with others across a variety of contexts, but did not address whether our model holds during actual social interactions. Study 4 addressed this issue by testing whether this process occurred in romantic couples who discussed one partner’s transgression against the other. The stress of such an interaction might attenuate the associations between compassionate goals and cooperative mindset. Further, cooperative mindset may not predict feeling at ease and connected in these potentially difficult conversations. Alternatively, having compassionate goals during these interactions might override the stress of the situation, allowing people to adopt a cooperative mindset, leading to greater feeling at ease and connected even in the midst of a difficult conversation. The design of Study 4 also allowed us to examine whether romantic partners contributed to participants’ cooperative mindsets or feeling at ease and connected following a difficult conversation. Specifically, it was possible that romantic partners’ cooperative mindsets or feeling at ease and connected could be transmitted to and mirrored by participants (i.e., actors). Following from Study 1, we also tested whether self-esteem, anxious and avoidant attachment, loneliness, or relationship conflict could account for our hypothesized pathways. Finally, the design of Study 4 allowed us to test the possibility that the cooperative mindset and feelings of ease and connection that people experience in social interactions are the result of emotion contagion (i.e., “catching” interaction partners’ affect) and do not necessarily follow from their own compassionate goals.

Method

Participants

Sixty-two romantic couples, including four lesbian and one gay couple, completed a 2-hour lab session. A majority of participants (60.5%) reported their race as White or European-American, 22.6% as Black or African-American, 7.3% Asian or Asian-American, 1.6% American Indian or Alaska Native, and 8.1% selected “other.” Participants ranged in age from 18 to 49 years (M = 21.64 years, SD = 3.95 years). Most couples (85%) reported that they were in a committed relationship, 5% were engaged, 5% were married, 1% were casually dating, and 4% reported their relationship status as “other.” Couples had been together for an average of 2.5 years (SD = 1.9 years, range: 8.5 months to 16 years).

Procedure

First, both members of each couple completed measures of self-esteem, anxious and avoidant attachment, loneliness in the relationship, and relationship conflict. They then provided a written description of the last time their partners had hurt them and rated their hurt feelings related to the event on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Participants rated their cooperative mindset and feelings of ease and connection when interacting with partners since that event. We choose each couple’s most hurtful event (as rated by participants) and couples discussed the event for 10 minutes. Participants reported being greatly hurt by events that were discussed (M = 4.08, SD = 1.03). After the discussion, both members of each couple reported their compassionate goals during the discussion and their current cooperative mindset and feeling of ease and connection.

Primary Measures

Compassionate goals for partners were measured using a scale identical to that used in Study 1. Items began with the stem, “During the discussion, how much did you want/try to.” The scale had adequate internal reliability in this sample (α = .86).

Cooperative mindset when interacting with partners was measured before and after the discussion with an item identical to those from Studies 2 and 3. Participants reported their cooperative mindset when interacting with partners since the time of the event by rating: “Since that event, when you interact with your partner, how much do you feel cooperative?” They reported their cooperative mindset after the discussion by rating “Right now, how much do you feel cooperative?” Both items were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Feeling at ease and connected when interacting with partners was measured using items identical to those from Studies 1–3. When participants reported their feelings of ease and connection when interacting with partners since the time of the event, items began with the stem: “Since that event, when you interact with your partner, how much do you feel:” When they rated their feelings of ease and connection after the discussion, items began with the stem “Right now, how much do you feel.” All items were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). These items had adequate internal reliability when referring to the time since the event (α = .81) and after the discussion (α = .86).

Covariates

All covariates were measured at the beginning of the lab session.

Self-esteem was assessed using the measure described in Study 2 (α = .87).

Anxious and avoidant attachment were measured using the scale described in Study 1. All items began with the phrase, “In my romantic relationship:” and were rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Both scales had good reliability in this sample (anxious: α = .85; avoidant: α = .90).

Loneliness was measured using a modified version of the loneliness scale described in Study 1. Three items were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely/very much). Items included “I feel as if my partner doesn’t really understand me,” “I feel completely alone in my relationship,” and “I feel isolated in my relationship.” These items had adequate internal reliability in these data (α = .72).

Relationship conflict was assessed using 6 items preceded by: “How much do you typically do each of the following?” with items rated on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Items included “You and your partner fight,” “You are upset with your partner,” “You have a disagreement with your partner,” “You feel like screaming at your partner,” “You and your partner criticize each other,” and “You and your partner have to iron-out differences,” (α = .88).

Results

We conducted Study 4 analyses in two phases. In Phase 1, we tested our hypothesized model in which participants’ compassionate goals during the discussion predicted change in their cooperative mindset toward partners from before to after the discussion, which predicted change in feelings of ease with and connection to partners from before to after the discussion. In Phase 2, we examined whether partners’ affective states (i.e., emotion contagion) accounted for each association in our path model. Specifically, we tested whether partners’ cooperative mindset accounted for the link between actors’ compassionate goals and increased cooperative mindset. We also tested whether partners feeling at ease and connected accounted for the link between actors’ increased cooperative mindset and increased feelings of ease and connection. In Phase 2 analyses, we also tested our path model, separately controlling for self-esteem, anxious and avoidant attachment, loneliness, and relationship conflict in 5 sets of mixed models. Because the structure of the data was identical to that of Study 2, we followed a parallel analytic strategy in Study 4 analyses. Additionally, we used a residual change strategy to test changes from before to after the discussion.

Phase 1: Testing our Hypothesized Model

As shown in Figure 3, results supported our hypothesis: participants’ compassionate goals during the discussion predicted their increased cooperative mindset after the discussion, b = .70, SE = .11, t(96.72) = 6.27, 95% CI [.48, .92], pr = .53, p < .001, which in turn led to their increased feelings of ease with and connection to partners, b = .32, SE = .06, t(103.52) = 4.92, 95% CI [.19, .45], pr = .44, p < .001. The indirect effect was significant (effect = .31, Sobel’s z = 4.47, p < .001), consistent with mediation.

Figure 3.

Unstandardized and standardized (i.e., partial correlations) path coefficients for models testing how participants’ compassionate goals during the discussion predicted their increased cooperative mindset from before to after the discussion, which in turn led to increased feelings of ease and connection after discussing a relationship transgression in Study 4. Path coefficients are estimated from separate multilevel models. *** p < .001,** p < .01, * p < .05.

Phase 2: Partner Effects and Covariates

We also tested whether each association in our path model could be accounted for by partners’ cooperative mindset or feeling at ease and connected. The data were structured so that, in analyses that included both couple members, each person was both an actor and a partner. First, we examined whether change in partners’ cooperative mindset predicted change in actors’ cooperative mindset, controlling for actors’ compassionate goals. Change in partners’ cooperative mindset was not uniquely related to change in actors’ cooperative mindset, b= .02, SE = .08, t(101.19) = .27, 95% CI [−.14, .19], pr = .03, p = .788, and the association between actors’ compassionate goals and change in their cooperative mindset remained stable, b= .69, SE = .12, t(98.26) = 65.93, 95% CI [.46, .93], pr = .51, p < .001. Next, we examined whether change in partners’ feeling at ease and connected predicted change in actors’ at ease/connected affect, controlling for change in actors’ cooperative mindset and actors’ compassionate goals. Partners’ increased feeling at ease and connected was uniquely related to actors’ increased feeling at ease and connected, b= .28, SE = .09, t(98.70) = .3.28, 95% CI [.11, .45], pr = .31, p = .001. However, the association between change in actors’ cooperative mindset and feeling at ease and connected remained unchanged, b= .29, SE = .06, t(94.42) = 4.607, 95% CI [.17, .42], pr = .42, p < .001. Thus, changes in actors’ cooperative mindset and feelings of ease and connection were not due to changes in partners’ parallel affective states.