Abstract

After implantation of a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device (LVAD), left atrial pressure (LAP) monitoring allows for the precise management of intravascular volume, inotropic therapy, and pump speed. In this case series of 4 LVAD recipients, we report the first clinical use of this wireless pressure sensor for the long-term monitoring of LAP during LVAD support. A wireless microelectromechanical system pressure sensor (Titan, ISS Inc., Ypsilanti, MI) was placed in the left atrium in four patients at the time of LVAD implantation. Titan sensor LAP was measured in all four patients on the intensive care unit and in three patients at home. Ramped speed tests were performed using LAP and echocardiography in three patients. The left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (cm), flow (L/min), power consumption (W), and blood pressure (mm Hg) were measured at each step. Measurements were performed over 36, 84, 137, and 180 days, respectively. The three discharged patients had equipment at home and were able to perform daily recordings. There were significant correlations between sensor pressure and pump speed, LV and LA size and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, respectively (r = 0.92–0.99, p < 0.05). There was no device failure, and there were no adverse consequences of its use.

Keywords: mechanical circulatory support, LVAD, left atrial pressure, MEMS

Severe heart failure is a progressive syndrome that sometimes requires mechanical circulatory support as a bridge to transplantation (BTT) or as a destination therapy. Current research is directed toward better monitoring of the physiologic interaction between the device and the cardiovascular system to reduce serious events.

The continuous-flow left ventricular assist device (LVAD) alters hemodynamics by continuously unloading the left ventricle, which results in an attenuated or absent arterial pulse pressure and shorter opening time or complete closure of the aortic valve. Excessive unloading of the left ventricle because of high LVAD pump speed or hypovolemia may result in a negative pressure within the left ventricle, causing ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, and a serious decrease in cardiac output. Careful management of intravascular volume, inotropic therapy, and pump speed are important throughout LVAD support if one is to avoid this serious complication.1–8

Early postoperative invasive monitoring with pulmonary artery and systemic arterial catheters is routine, and intermittent echocardiographic studies are performed during ambulatory support. Continuous direct left atrial pressure (LAP) monitoring allows for the precise assessment of left heart pressure and guides therapy to optimize the balance between pump preload and pump speed. In ambulatory patients, the ability to measure LAP permits rapid and accurate ramped speed testing for determining optimal pump speed settings.9

The Titan LAP monitoring system (ISS Inc., Ypsilanti, MI) is an implantable microelectromechanical system (MEMS) pressure sensor that has wireless communication with an external monitor for on-line LAP monitoring. The system is capable of remote monitoring of LAP over the Internet, giving physicians the ability to rapidly assess potentially dangerous hemodynamic conditions. We report our initial clinical experience using the Titan sensor system and discuss the potential clinical use of this device.

Materials and Methods

Patients

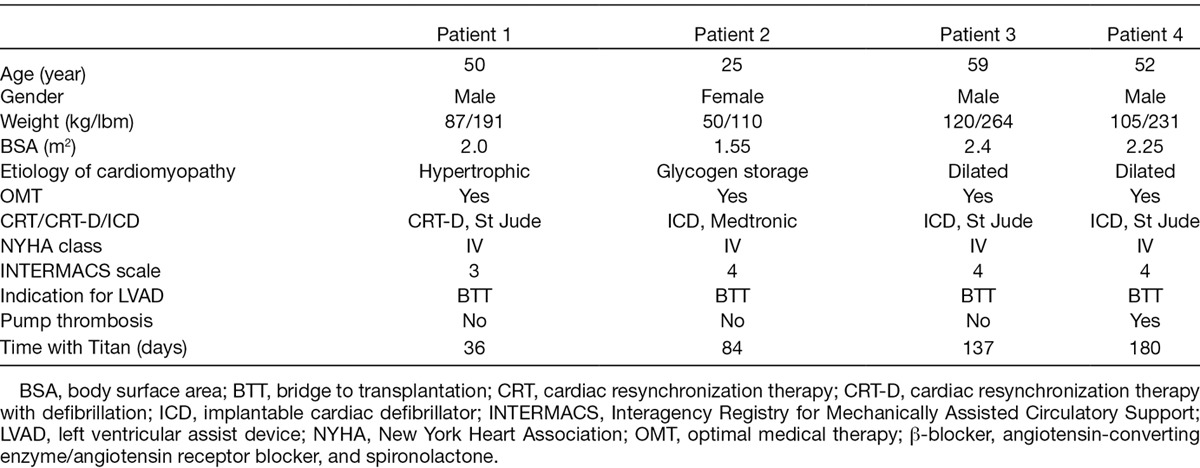

Four patients with severe heart failure, who were scheduled for the implantation of a HeartMate II LVAD (St. Jude, St. Paul, MN) as BTT, were invited to participate in a study evaluating the Titan system in LVAD patients. After study participation had been explained and study criteria met, patients gave their informed consent. The study was approved by The Swedish Medical Products Agency Dnr: 461:2012/518610 and the Regional Ethics Committee Dnr: 2013/50-31. All four patients were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV and Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) profiles 3 or 4, and had an implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD), one patient also had a cardiac resynchronization device (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of Patients in the Study

Device Description

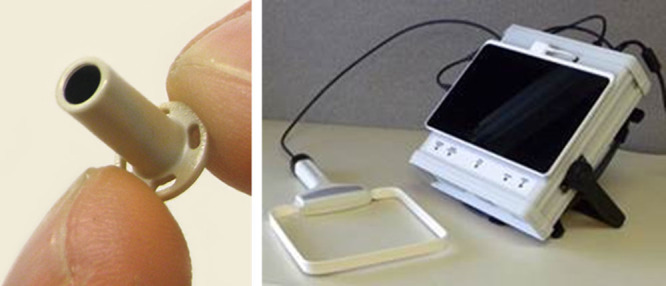

The Titan wireless implantable hemodynamic monitoring system comprises two major parts: an implantable telemetric sensor with no implanted power source or battery and an external companion readout electronics/user interface (Figure 1). Using radiofrequency (RF) magnetic telemetry, the reader transmits power to the sensing implant and communicates with it. The RF interface is achieved with very low power, which is many times smaller than the commercial RF scanners. The wireless communications includes detailed cardiac pressure waveforms and implant information such as implant powering information to perform advanced dynamic power transmission.

Figure 1.

Titan sensor with the sensing element at the distal end. The proximal end has four holes for fixation with sutures (left panel). The antenna and recording unit for home-monitoring using a tablet computer (right panel).

The miniature implant consists of a polyetheretherketone anchor and a cylindrical pressure-sensing probe placed inside the anchor. The probe contains a miniature MEMS pressure sensor along with custom electronics and a telemetry antenna. There are 4 different lengths, between 18 and 30 mm, and the implant can be secured in the correct position with sutures through four small holes at the flat top of the anchor. The signals are stored on the individual recording unit and at the same time transmitted to a central server in MI, USA. Remote control for trouble-shooting and patient service is possible because the data are immediately available to physicians over the Internet.

Surgical Procedure

The LA implant was introduced at the end of the operation (but before starting the HeartMate II LVAD) through the incision in the border between the LA and the right upper pulmonary vein used intraoperatively for blood drainage of the left heart. The proximal part of the sensor was secured with sutures to the epicardium through four holes around the circumference. An adequate position, free from the wall of the pulmonary vein or atrium, was confirmed with ultrasound. A reference LA standard fluid-filled catheter was inserted, and baseline measurements were acquired simultaneously with the sensor implant and reference catheter.

The time available for the use of the reference LA catheter was dependent on the patient’s hemodynamic condition. While in hospital, daily measurements were performed, and when discharged, the patient performed recordings at home; daily for 1 month and 2–3 times a week thereafter. The patient records signals are sent through Internet to the hospital. Once a day a heart failure nurse analyzes the recordings, and each time if an unexpected pressure curve or trend is noted, the patient is contacted by telephone. The nurse asks the patient about current medication or change in dose, fluid intake, and about any symptoms. On most occasions, the pressure changes can be explained once these questions are answered but if not, the patient is asked to come to the hospital for diagnostic tests. A cardiologist is always available for consultation. In addition to this systematic evaluation, patients are encouraged to take recordings if they feel something is wrong. On these occasions, they can contact the nurse directly after transmitting the signal.

Echocardiography and Ramped Speed Test

The sensor is visible on transesophageal echocardiography after implantation. After discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU), echocardiography was used for estimation of the filling pressure of the left ventricle and for optimizing the pump speed. An echocardiographic ramped speed test according to the Columbia protocol10 was performed in 3 patients. The speed was decreased to 8,000 rpm and then increased stepwise by 400 rpm up to a maximum of 12,000 rpm. The left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), LA dimension, blood flow, power consumption, blood pressure, aortic cusp closure, and mitral regurgitation were measured at each step. Titan LAP was measured in all 4 patients on the thoracic ICU and on the ward, and, in 3 patients, at home and at the time of the echocardiographic ramped speed test.

Results

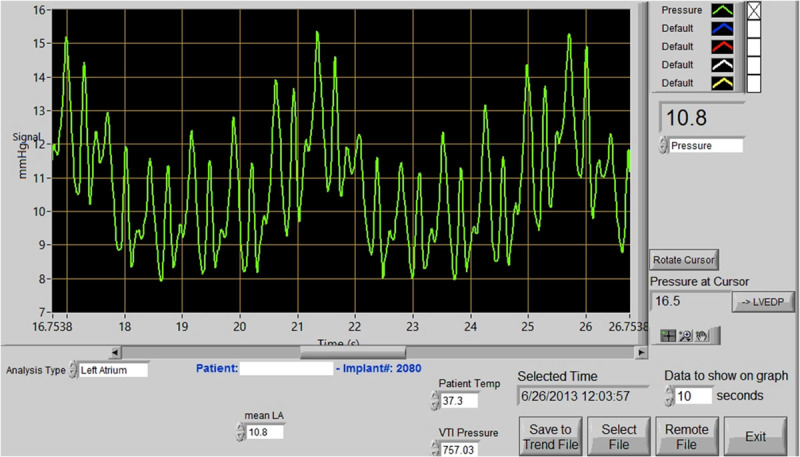

The time taken for the implantation of the Titan device was less than 15 minutes in all four patients. The sensor signal was presented as a pressure curve on a computer screen as shown in Figure 2. Repeated recordings were performed over 36, 84, 137, and 180 days, respectively (Table 1). The three discharged patients had equipment at home and were able to perform frequent recordings. The pressure curves were analyzed remotely by specially trained nurse at the hospital, who also communicated with the patient if unexpected pressure values were recorded.

Figure 2.

Titan system monitor screen showing a left atrial pressure curve and mean pressure value (right panel). The data are stored on a computer and sent through the Internet to a central server. In the left panel is an example of plot showing the daily trend of LAP measurements taken at home by the patient.

Patient 1

Patient 1 had a complicated postoperative course and died after 36 days on the ICU due to right heart failure and subsequent multiorgan failure. The patient was regarded not suitable for heart transplantation. The fluid-filled catheter in the left atrium was removed 4 days after surgery. The Titan sensor emitted a similar waveform signal as the standard fluid-filled catheter. Concomitant recordings with a fluid-filled LA catheter showed good correlation, differing by a maximum of 3 mm Hg, without the need for calibration of the sensor.

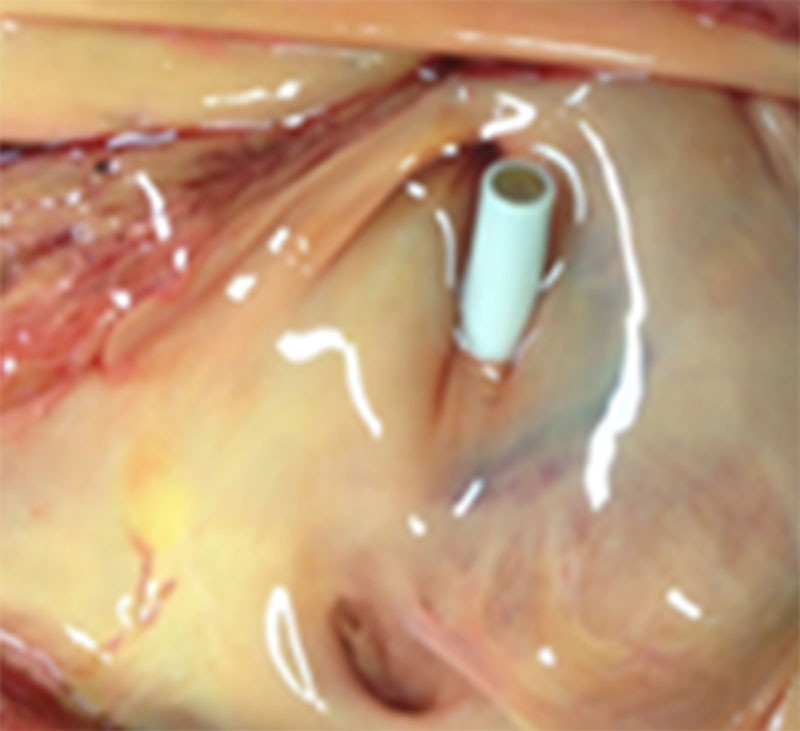

The patient deteriorated despite HeartMate II support, and filling pressures increased with time and organ failure developed. The LAP waveform varied, with periods of high v-wave values. The events coincided with increasing signs of mitral regurgitation on echocardiography. The v-wave values corresponded to the pump speed and decreased when pump speed was increased. At autopsy, the LA sensor implant was clean, and there was no reaction in the surrounding endocardium (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Titan left atrium implant at patient 1’s autopsy 36 days after the implantation of the LVAD and sensor. The sensor shows no sign of cell tissue overgrowth.

Patient 2

Patient 2 had an uneventful postoperative course and spent 7 days on the ICU. The fluid-filled catheter in the left atrium was removed the day after surgery. The Titan sensor LAP correlated with the fluid-filled catheter LAP during that time, and the difference between the fluid-filled catheter and the Titan sensor pressure was only 1 mm Hg during that first day. The patient was discharged from hospital 29 days after the operation. Ten weeks after implantation, an evaluation with an echocardiographic ramped speed test was performed. The patient was thereafter successfully transplanted after 84 days with HeartMate II support and with the Titan sensor.

Patient 3

Patient 3 had a complication-free postoperative course and spent 5 days on the ICU. The fluid-filled catheter in the left atrium was removed 2 days after surgery. The difference between the fluid-filled catheter and the Titan sensor pressure was 2 mm Hg during that period. The patient was discharged from hospital 25 days after the operation, and 6 weeks after implantation an evaluation with an echocardiographic ramped speed test was performed. The patient was successfully transplanted after 137 days with HeartMate II support and the Titan sensor.

Patient 4

Patient 4 had a normal postoperative course and spent 5 days on the ICU. The fluid-filled catheter in the left atrium was removed the day after surgery. The difference between the fluid-filled catheter and Titan sensor pressure was 3 mm Hg. The patient was discharged from hospital 14 days after the implantation of the HeartMate II LVAD and Titan sensor. Eight weeks after implantation, an echocardiographic ramped speed test was performed. The mean LAP at home was 15 mm Hg, but after eleven weeks, the daily recorded Titan signal revealed a sudden rise in LAP to 25 mm Hg. The special nurse reacted because of the sudden increase and informed the responsible cardiologist. Subsequent laboratory samples showed pathologic increases in lactate dehydrogenase and acoustic signs of pump malfunction supporting the clinical suspicion of pump thrombosis. He was reoperated for a pump exchange, and thrombosis in the pump housing was verified. The second HeartMate II functioned normally, and the patient was transplanted after 180 days of HeartMate II support and with the Titan sensor.

Ramped Speed Test in Patients 2, 3, and 4

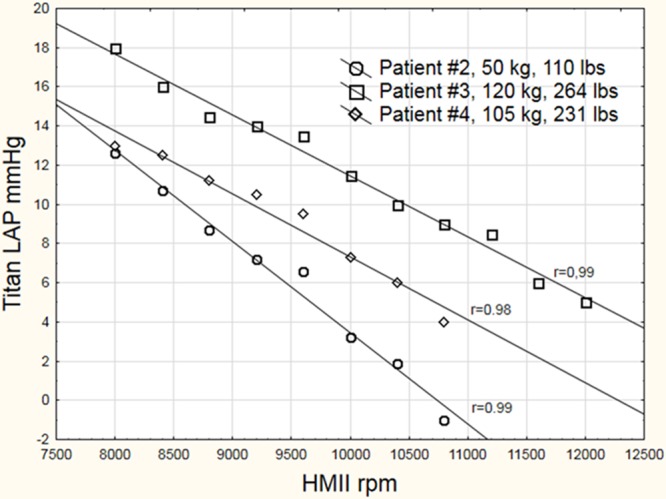

In all 3 patients, blood tests and clinical and echocardiographic findings revealed no sign of pump thrombosis, and the pump monitor parameters reacted normally according to the ramped speed test protocol. The test was performed in the supine position, and the pump setting was increased from 8,000 rpm in 400 rpm intervals to a maximum of 12,000 rpm. The test was stopped when the LV was totally unloaded with low LVEDD or when the mitral cusps were wide open risking suction of the LV wall against the pump cannula. The Titan sensor pressure values were measured concomitantly and plotted against pump speed (Figure 4). There were significant correlations (r = 0.92–0.99, p < 0.05) between Titan sensor pressure, pump speed, LVEDD, and LA diameter.

Figure 4.

LAP during an echocardiographic ramped speed test in 3 patients. The trend of decreasing LAP when pump speed was increased can be seen. A value of zero indicates that pump speed is too high. The individual correlations between pump speed and LAP measured by the Titan sensor were significant (r = 0.92–0.99, p < 0.05). LAP, left atrial pressure.

The aortic cusps closed and mitral regurgitation disappeared at a LA pressure of 8 mm Hg and at LA dimension of 3 cm in all patients. Systemic blood pressure increased by median of 5 mm Hg during the ramped speed test. Optimal pump speed was considered when the aortic cusps opened at every third–sixth heartbeat.

Discussion

This is the first report on the human application of this wireless pressure sensor in patients undergoing LVAD support. The wireless, battery-free operation allows the Titan device to potentially function for long periods of time with no maintenance or need for battery replacement after initial implantation. During the echocardiographic ramped speed test, we observed significant correlation with rpm and LV size. Each patient’s ramped speed test showed optimal pump speed at an LAP of 8 mm Hg, where the aortic cusps closed and mitral regurgitation diminished. This indicates that sensor LAP may be helpful in attaining optimal pump speed and may be helpful in identifying problems related to sudden increases in LAP. Sensor LAP measurement on a daily basis could provide us with a new tool for monitoring pump function. Theoretically, if sensor information could be transmitted to the pump controller, this would be an attractive way of fine-tuning pump settings. Our initial experience has shown us the feasibility of accurately monitoring LAP in ambulatory patients at home.

Since 2003, before initiating these clinical studies, more than 60 animal studies in 4 different large animal models had been conducted with favorable results regarding biocompatibility, thrombogenicity, and functionality.11,12 We tested the device for possible electromagnetic interference in our animal laboratory before considering human application. We found no sign of interference with the HeartMate II LVAD or other clinically used devices, such as pacemakers, ICDs, and mechanical valves.

The Titan sensor has been tested in all heart chambers and in the aortic and pulmonary arteries. No thromboembolic complications were observed in the long-term (2–4 months) animal studies. The sensor has been compared with measurements from Millar catheters, showing overlapping pressure waves and very similar pressure values without the need for calibration of the sensor. A few sensors showed drift in the initial animal experiments, and the problem was found to be deficiency in the sealing of the MEMS inside the sensor. The manufacturing process was improved before human application. No drift was seen in the current study. In this series, all patients were on regular LVAD anticoagulation therapy. In an ongoing clinical study, the device has been tested for almost 3 years (with a total observation time in all patients of >6,000 days of recordings) in patients after open chest surgery and transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) most of them receiving postoperative aspirin or coumadin. Nine patients have not been treated with anticoagulants, and so far, there has been no sign of any thromboembolic event. About positioning of the device, in the ongoing clinical study on 25 patients, the device was positioned in the left atrium (20) or left ventricle (5), and the 4 patients with LVAD all had their device in the left atrium.

Measurement of sensor pressure is a quick and easy procedure to perform, both for postoperative monitoring in the clinical setting and for recording signals at home by the patient after initial training. The Titan sensor pressure waveforms and values correlated with those of a standard fluid-filled catheter. The v-wave values corresponded to the pump speed and decreased when pump speed was increased implying that sensor waveforms reflected variations in mitral regurgitation in the postoperative course. The technique is easy to use for remote monitoring of the LAP, and we have obtained viable results for years in patients included in the ongoing randomized clinical study.

Limitations

Development of the wireless implantable hemodynamic monitor remains in its early stages, and more clinical trials are warranted to ensure benefit to patient outcome before such devices can be incorporated into standard management. The number of patients in this pilot study was small, but it did reveal the potential of this device as an adjunct to surgical treatment. Another limitation is the short follow-up time in three of the patients because of the relatively short-waiting time for heart transplantation.

Larger studies in the future will hopefully confirm the potential of this technology to substantially improve patient care and survival.

Conclusions

The Titan wireless intracardiac sensor gave pressure values and waveforms similar to those of the standard fluid-filled catheter, without the need for calibration of the implant. Significant correlations with pump speed and LV size during echocardiographic ramped speed tests indicate that sensor LAP values may be helpful in regulating optimal pump speed in the future. LVAD patients can have a wireless device safely implanted, that not only measures pressure inside the heart but also provides feedback allowing automatic adjustment of pump speed and unloading of the heart under different physical conditions.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclosure.

The study was supported by grants from the County Council of Ostergotland and Linkoping University Foundations, Sweden. The Titan system used in the study was provided by ISS Inc., Ypsilanti, MI.

References

- 1.Pagani FD, Miller LW, Russell SD, et al. ; HeartMate II Investigators: Extended mechanical circulatory support with a continuous-flow rotary left ventricular assist device. J Am Coll Cardiol 200954: 312–321.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slaughter MS, Pagani FD, McGee EC, et al. ; HeartWare Bridge to Transplant ADVANCE Trial Investigators: HeartWare ventricular assist system for bridge to transplant: combined results of the bridge to transplant and continued access protocol trial. J Heart Lung Transplant 201332: 675–683.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano CA, et al. ; HeartMate II Investigators: Advanced heart failure treated with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med 2009361: 2241–2251.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamdar F, Boyle A, Liao K, Colvin-adams M, Joyce L, John R. Effects of centrifugal, axial, and pulsatile left ventricular assist device support on end-organ function in heart failure patients. J Heart Lung Transplant 200928: 352–359.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radovancevic B, Vrtovec B, de Kort E, Radovancevic R, Gregoric ID, Frazier OH. End-organ function in patients on long-term circulatory support with continuous- or pulsatile-flow assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant 200726: 815–818.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grady KL, Magasi S, Hahn EA, Buono S, McGee EC, Jr, Yancy C. Health-related quality of life in mechanical circulatory support: development of a new conceptual model and items for self-administration. J Heart Lung Transplant 201534: 1292–1304.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maciver J, Ross HJ. Quality of life and left ventricular assist device support. Circulation 2012126: 866–874.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes K, Leet AS, Bradley SJ, Holland AE. Effects of exercise training on exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with a left ventricular assist device: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Heart Lung Transplant 201231: 729–734.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pratt AK, Shah NS, Boyce SW. Left ventricular assist device management in the ICU. Crit Care Med 201442: 158–168.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uriel N, Morrison KA, Garan AR, et al. Development of a novel echocardiography ramp test for speed optimization and diagnosis of device thrombosis in continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices: the Columbia ramp study. J Am Coll Cardiol 201260: 1764–1775.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Najafi N, Ludomirsky A. Initial animal studies of a wireless, batteryless, MEMS implant for cardiovascular applications. Biomed Microdevices 20046: 61–65.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammond RL, Hanna K, Morgan C, et al. A wireless and battery-less miniature intracardiac pressure sensor: early implantation studies. ASAIO J 201258: 83–87.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]