Abstract

It is essential to assess environmental impact of transgene flow from genetically engineered crops to their wild or weedy relatives before commercialization. Measuring comparative trials of fitness in the transgene-flow-resulted hybrids plays the key role in the assessment, where the segregated isogenic hybrid lineages/subpopulations with or without a transgene of the same genomic background are involved. Here, we report substantial genomic differentiation between transgene-present and -absent lineages (F2-F3) divided by a glyphosate-resistance transgene from a crop-wild/weed hybrid population in rice. We further confirmed that such differentiation is attributed to increased frequencies of crop-parent alleles in transgenic hybrid lineages at multiple loci across the genome, as estimated by SSR (simple sequence repeat) markers. Such preferential transmission of parental alleles was also found in equally divided crop-wild/weed hybrid lineages with or without a particular neutral SSR identifier. We conclude that selecting either a transgene or neutral marker as an identifier to create hybrid lineages will result in different genomic background of the lineages due to non-random transmission of parental alleles. Non-random allele transmission may misrepresent the outcomes of fitness effects. We therefore propose seeking other means to evaluate fitness effects of transgenes for assessing environmental impact caused by crop-to-wild/weed gene flow.

Introduction

The undesired environmental impact caused by transgene flow from genetically engineered (GE) crops to their wild and weedy relatives has stimulated great biosafety concerns worldwide1–6. It is necessary then to assess the environmental impact prior to the commercialization of any GE crops. The common practice to assess such impact includes two key components: determining frequencies of (trans)gene flow and estimating fitness effects of a transgene acquired by wild/weedy relative populations5–7. Concerns centre on the possibility that transgenes with natural selective advantages or disadvantages may convey fitness benefits or costs to wild/weedy populations6, 8, 9, creating unwanted environmental and evolutionary consequences3, 7, 10–12. Transgenic fitness has been extensively estimated in many types of hybrid descendants derived from crosses between GE crop species and their wild relatives to predict the potential environmental impact of transgene flow, including oilseed rape13, 14, squashes1, 15, sunflowers10, 16, maize17, and rice18–20. Therefore, fitness becomes essential for assessing the environmental impact caused by transgene flow, after the frequency of gene flow is determined5.

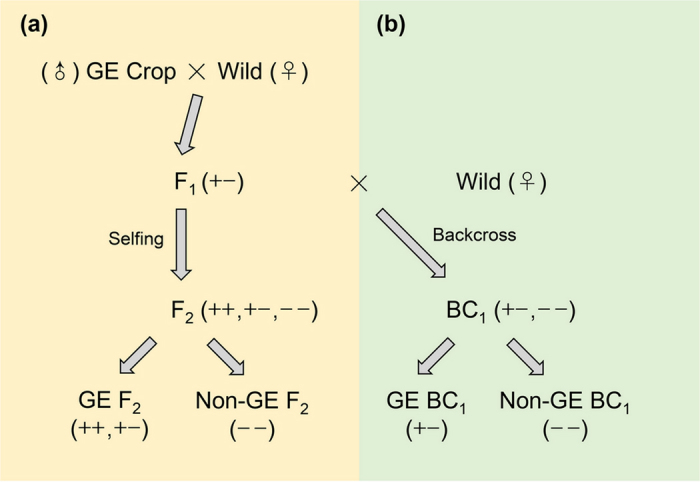

Usually, transgenic fitness is estimated in a common-garden experiment, where artificially produced ISOGENIC hybrid lineages (or subpopulations) with or without a transgene from a crop-wild/weed hybrid population (F2 or BC1) are included for comparison10, 17–22. Our literature survey from the Web of Science (http://apps.webofknowledge.com/) indicated that more than 70% of the recently published relevant research articles (2000–2017) included the isogenic hybrid lineages to estimate transgenic fitness (Supplementary Fig. 1). Therefore, simulating crop-wild or crop-weed transgene flow, hybrids between a GE crop and its wild/weedy relative species are produced and F2 or BC1 hybrid populations were derived through self-pollination of F1 hybrids (Fig. 1a) or backcrosses of F1 hybrids with their wild/weedy parents (Fig. 1b). The key point to assess fitness of a transgene is to divide a F2 or BC1 hybrid population into isogenic lineages/subpopulations with the target transgene (including transgene-homozygous and -heterozygous) or without a transgene, using the transgene as an identifier (Fig. 1a,b). The fitness of a transgene is estimated by comparing fitness-related traits between the transgene-present and -absent lineages in the common-garden experiments10, 17–22, under the assumption that transgene-present and -absent lineages only differ on average in the presence of the transgene. In other words, the genetic composition of the hybrid lineages/subpopulations with or without the transgene are considered to be genetically equivalent and effectively isogenic. Consequently, the detected differences between these lineages are only due to the presence or absence of the transgene(s)17–22. However, the assumption has never been properly tested.

Figure 1.

A schematic pedigree to illustrate the production of F2 (a) and BC1 (b) crop-wild or crop-weed hybrid lineages for estimating the fitness effect of a transgene. “GE crop” indicates a genetically engineered crop parent; “Wild” indicates a wild or weedy parent; “++ and +−” indicate transgene-homozygous and -hemizygous GE lineages, and “− −” indicates non-GE lineages.

In our common garden experiment aimed to estimate fitness of an epsps (5-enolpyruvoylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase) transgene, we observed phenotypic differences between F3 transgenic and non-transgenic seedlings derived from the same crop-wild F1 hybrids (Fig. 2). The hybrids included two parents: an herbicide-resistant GE rice (Oryza sativa) line and a wild rice (O. rufipogon) accession, sharing the AA genome23, 24. We further noticed that the transgenic seedlings exhibited more traits from the cultivated parent (e.g., shorter and more erect plants without pigmentation at the base, see Fig. 2), whereas the non-transgenic seedlings showed more traits from the wild parent (e.g., taller and prostrating plants with purple pigmentation at the base, see Fig. 2). Apparently, transgenic lineages inherited more traits from the crop parent, while non-transgenic lineages inherited more traits from the wild parent.

Figure 2.

Phenotypic variation of seedlings in F3 transgene-present (orange arrow) and transgene-absent (yellow arrow) hybrid lineages derived from an artificial cross between an epsps (5-enolpyruvoylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase) transgenic rice line and wild rice (Oryza rufipogon).

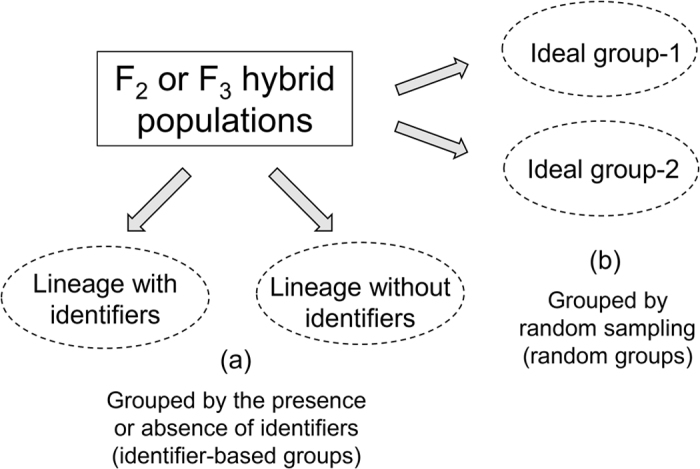

The phenotypic differences between transgenic and non-transgenic hybrid seedlings should not be observed under the assumption that the isogenic hybrid lineages only differ in the transgene but share on average the identical genomic background. It is known that genetic hitchhiking shapes the genome of hybrid populations under natural selection25, 26. Similarly, can the artificial selection for a specific gene (identifier) distort a part of the genome by hitchhiking towards one of the parents? To address this question, we produced F2-F3 crop-wild and crop-weed hybrid lineages with or without the epsps transgene and neutral microsatellite or SSR (simple sequence repeat) identifiers (Fig. 3) in a new experiment to test the following hypotheses. (1) Dividing hybrid lineages with or without a transgene by selecting transgenic identifier will result in a difference in their genomic background caused by non-random parent-allele transmission; (2) non-random transmission of parental alleles is not necessarily related to selection of the transgene identifier but to any random identifier; and (3) preferential allelic transmission from one parent is associated with the selection of an identifier from the specific parent. The proof of the hypotheses will facilitate our design of a better method to estimate transgenic fitness, which is important for risk assessment of transgene flow from a GE crop to its wild or weedy relative populations. In addition, the generated knowledge can also increase our understanding of the effect of selection on transmission of parental alleles into their hybrid descendants.

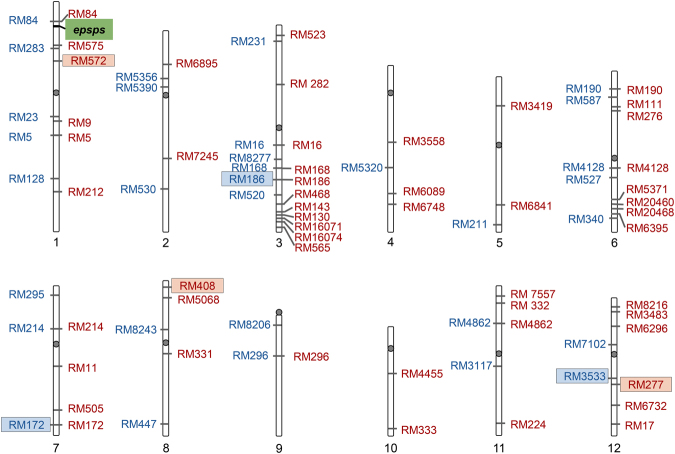

Figure 3.

A genomic linkage map illustrating the physical location of the epsps (5-enolpyruvoylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase) transgene on chromosome-1 (green box), the six neutral SSR (simple sequence repeat) identifiers (pink boxes for crop-wild and blue boxes for crop-weed hybrids), and 52 (red letters, for crop-wild hybrids) and 32 (blue letters, for crop-weed hybrids) SSR markers located across the 12 rice chromosomes.

Results

Differences in the genomic background between transgenic and non-transgenic hybrid lineages

We found considerable differences in the genomic background between the “isogenic” F2-F3 crop-wild/weed hybrid lineages with or without the epsps transgene. The diversity coefficient (F st) analyses indicated a certain level (F st = 0.02–0.05) of genomic differentiation between transgenic and non-transgenic crop-wild/weed hybrid lineages (Table 1). As a comparison, the F st values between the corresponding ideal groups were all less than 0.001 for both crop-wild/weed hybrid populations (Table 1), suggesting extremely low genomic differentiation. These results indicated that the division of transgenic and non-transgenic hybrid lineages using the transgene as an identifier would result in differences in their genomic background, probably due to the non-random transmission of parental alleles.

Table 1.

Diversity coefficient (F st) values (left) and numbers of non-neutral loci (right) between hybrid lineages with or without the epsps transgene (as an identifier, GE), with or without the crop-parent SSR markers (as identifiers, CM), and with or without the wild/weedy-parent SSR markers (WM), created from an F2/F3 crop-wild (W) or crop-weedy (WD) rice hybrid population.

| Hybrid population | GE lineages | CM lineages | WM lineages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM572 | RM408 | RM277 | RM572 | RM408 | RM277 | ||

| F2-W | 0.018/14 | 0.020/8 | 0.025/13 | 0.026/14 | 0.017/7 | 0.017/10 | 0.026/13 |

| F3-W | 0.013/16 | 0.026/15 | 0.024/15 | 0.030/13 | 0.026/14 | 0.024/10 | 0.027/13 |

| RM186 | RM172 | RM3533 | RM186 | RM172 | RM3533 | ||

| F2-WD | 0.051/15 | 0.043/16 | 0.091/9 | 0.060/8 | 0.037/9 | 0.077/11 | 0.077/11 |

| F3-WD | 0.045/11 | 0.046/9 | 0.104/12 | 0.052/16 | 0.045/5 | 0.129/11 | 0.053/9 |

F st values between the ideal groups are all <0.001. Numbers of non-neutral loci between the ideal groups are close to zero.

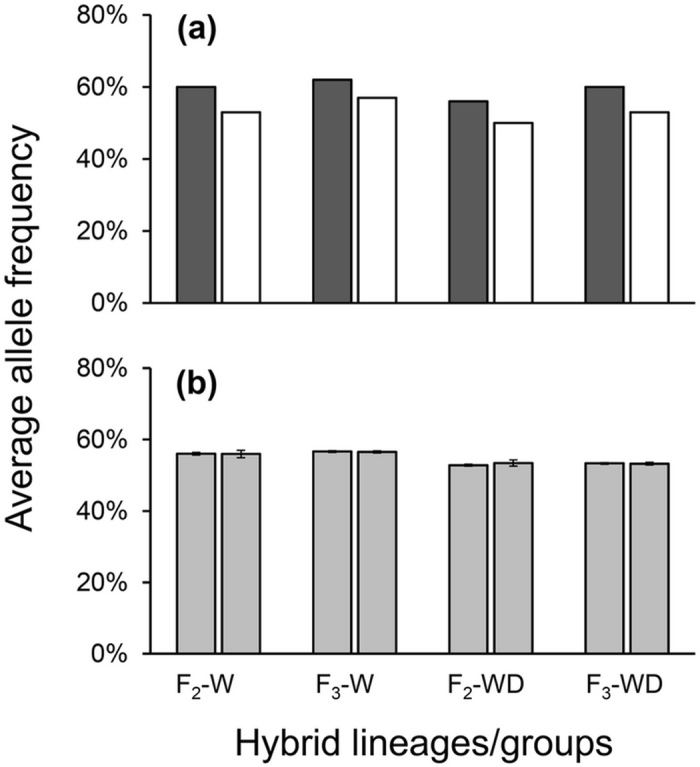

In addition, we also detected much higher frequencies of alleles derived from the epsps rice parent in the transgenic F2 and F3 hybrid lineages than in their corresponding non-transgenic lineages (Fig. 4a,b), suggesting the influences of sampling transgene as an identifier on transmission of parent alleles at multiple loci. The bootstrap percentile method (BPM) analyses of each SSR locus indicated significant differences in parent-allele frequencies at multiple SSR loci between transgenic and non-transgenic crop-wild (46–52% loci), as well as crop-weed (28–59% loci) hybrid lineages (Supplementary Tables 1, 2). The neutrality test also confirmed the significant deviation of parental alleles from the theoretical values at most of these loci for both crop-wild and crop-weed hybrid lineages (Supplementary Tables 3, 4). Altogether, these results suggested that the separation of transgenic and non-transgenic hybrid lineages by using a transgene as an identifier caused non-random transmission of parental alleles into the resulted hybrid lineages.

Figure 4.

Average frequencies of crop-parent alleles in hybrid lineages (a) and groups (b) separated from an F2 or F3 hybrid population containing an epsps transgene. “W” represents wild rice (Oryza rufipogon); “WD” represents weedy rice. Dark-gray and white columns in (a) indicate lineages with and without a transgene, respectively. Light-gray columns in (b) indicate randomly formed groups. Bars indicate standard deviation.

Interestingly, we detected more alleles from cultivated rice in transgenic crop-wild hybrid lineages than in their corresponding non-transgenic lineages at the loci that showed significant differences in parental allele frequencies (Fig. 4a). Allele frequencies of cultivated rice were 60–62% in transgenic and 53–57% in non-transgenic crop-wild lineages (Fig. 4a). Similar results were also found in transgenic crop-weed hybrid lineages (Fig. 4a). In contrast, the two corresponding ideal groups of crop-wild/weed hybrid descendants did not show significant differences in crop parent-allele frequencies (Fig. 4b). These results suggested preferential transmission of crop alleles into transgenic hybrid lineages (F2 and F3), likely associated with the sampling of the transgene as an identifier to create transgenic and non-transgenic hybrid lineages.

Non-random transmission of parental alleles into hybrid lineages with or without neutral identifiers

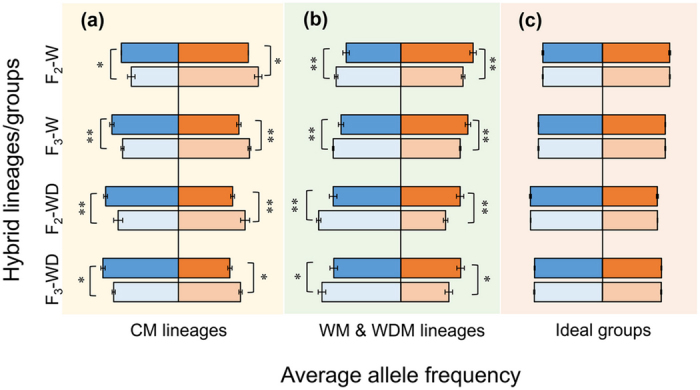

We found considerable differences in genomic background between crop-wild/weed hybrid lineages with or without the identifiers when neutral SSR markers (identifiers) were used to create lineages in transgene-free hybrid combinations. This finding suggested that the non-random transmission of parental alleles into hybrid lineages might not necessarily be related to the transgene, but related any random identifiers (Table 1, Fig. 5a–c, Supplementary Tables 3–6).

Figure 5.

Average frequencies of parental alleles in hybrid lineages (a,b) and ideal groups (c) separated from a transgene-free F2 or F3 crop-wild (W) /weed (WD) hybrid population. (a) CM lineages are grouped by sampling individuals with crop-parent markers; (b) WM or WDM lineages are grouped by sampling individuals with wild- or weedy-parent markers; (c) Ideal groups are formed randomly. Blue and light-blue columns indicate frequencies of crop-parent alleles in lineages with and without markers, respectively; orange and light-orange columns indicate frequencies of wild- or weedy-parent alleles in lineages with and without markers, respectively. Bars indicate standard deviation. *,**Significance at P < 0.05 or P < 0.01, based on the one-tail paired t test.

Comparatively high F st values were detected between the corresponding hybrid lineages with or without the three random selected identifiers, ranging from 0.02–0.03 for crop-wild lineages, and from 0.04–0.13 for crop-weed lineages (Table 1). In contrast, the F st values between the corresponding ideal groups were < 0.001. These results suggested considerable genomic differentiation between hybrid lineages with or without the neutral identifier. The BPM analyses showed 19–71% SSR loci of which the parent-allele frequencies were significantly different (P < 0.05) between the corresponding crop-wild/weed hybrid lineages (Supplementary Tables 5, 6). The neutrality test also confirmed the significant deviation of parental alleles from the theoretical values in crop-wild/weed hybrid lineages (Table 1, Supplementary Tables 3, 4).

Preferential transmission of parental alleles into hybrid lineages with selecting for a specific identifier

We found increased allelic frequencies of a parent in crop-wild and crop-weed hybrid lineages that were created by using a neutral identifier from this specific parent, suggesting that preferential allelic transmission from one parent was closely associated with the selection of an identifier located on the genome of this specific parent (Fig. 5a-c, Supplementary Tables 5–6).

Significantly higher (P < 0.05) average frequencies of crop alleles were detected in crop-wild hybrid lineages (45–53%) with the identifiers from the crop parent than in the hybrid lineages (37–44%) without the crop identifiers, based on the one-tail paired t test (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Table 5). Similar trends were also observed in crop-weed hybrid lineages (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Table 6). On the other hand, significantly higher average frequencies of wild alleles were detected in crop-wild hybrid lineages (53–57%) with the identifiers from the wild parent than in the lineages (47–49%) without the wild identifiers (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Table 5). Similar trends were also found in crop-weed hybrid lineages (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Table 6). However, no significant differences in allele frequencies were observed in the corresponding ideal groups of crop-wild/weed hybrid descendants (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

Results from this study demonstrated evident genomic differentiation between transgenic and non-transgenic hybrid lineages divided by using the epsps transgene as an identifier, suggesting that the hybrid lineages/subpopulations created from a hybrid population using this method are not isogenic. This finding can well explain our previous observation about the phenotypical differences between transgenic and non-transgenic crop-wild hybrid seedlings (Fig. 2). Apparently, the selection of the transgenic identifier located on the genome of cultivated rice caused differences in the genomic background, as well as the phenotypes, between transgenic and non-transgenic hybrid lineages. Therefore, selecting a transgenic identifier from cultivated rice resulted in more traits from the crop parent that contained a transgene. In addition, different frequencies of parental alleles were found between transgenic hybrid lineages and their corresponding non-transgenic counterparts at multiple loci (Fig. 4), suggesting non-random transmission of parental alleles into hybrid lineages. The findings should be sound because a substantial amount of analytical data (Table 1, Fig. 4, Supplementary Tables 1–4) from F2-F3 hybrid descendants derived from artificial crosses between a GE epsps rice line and an accession of wild or weedy rice (O. sativa f. spontanea) was analyzed. In addition, we also included F2 and F3 hybrid descendants in this study to examine the consistency of the obtained results between independent generations. The obtained results support our first hypothesis that selecting a transgene as an identifier to produce “isogenic” hybrid lineages with or without a transgene can result in differences in their genomic background, although the influences of the transgene on genomic differentiation between hybrid lineages cannot be completely ruled out.

To circumvent the possible influences of the epsps transgene (Fig. 4) on genomic differentiation and non-random transmission of parental alleles, we used transgene-free crop-wild/weed hybrid lineages derived from crosses between a rice variety (Minghui-86) and a wild/weedy rice accession to determine the possible differences in the genomic background. Similar to the results obtained from transgenic hybrid lineages, we also detected significant differentiation in the genomic background of transgene-free hybrid lineages with or without the neutral identifiers used to separate hybrid descendants (F2-F3). The finding indicated that even without the involvement of a transgene, genomic differentiation still occurred between the identifier-present and -absent F2-F3 hybrid lineages separated by using the neutral identifiers. In addition, significant differences in frequencies of parental alleles were also found between the transgene-free hybrid lineages with or without the neutral identifiers at multiple loci. The differences in allele frequencies indicated that selecting a neutral identifier would also influence transmission of the parental alleles into hybrid lineages27–30. These findings based on a great amount of data (Table 1, Fig. 5, Supplementary Tables 3–6) support our second hypothesis that non-random transmission of parental alleles is not necessarily related to the selection of a transgenic identifier but most likely to any type of random identifiers.

The above findings indicate the strong influence of artificial sampling or selection of a target identifier, regardless of a transgene or other types of markers (e.g., neutral SSR markers), on genomic differentiation and non-random allelic transmission in the identifier-based lineages of hybrid descendants. In this study, the sampling of transgenic and non-transgenic hybrid lineages has played a critical role as a selection force, causing the preferential transmission of parental alleles that are genetically linked with the transgene into transgenic lineages, similar to the “hitchhiking effect” in evolution27–30. Remington et al.31 identified considerably altered genome-wide linkage disequilibrium patterns in maize by the artificial grouping of the maize lines into different subpopulations according to the regions of their origins from the total sample set31. This case study also indicates the strong influences of artificial selection on the allele assortment at multiple loci, supporting our findings of the non-random transmission of parental alleles in crop-wild/weed hybrid lineages. If this assumption holds true, the commonly used method to evaluate fitness of a transgene(s) by dividing F2/F3 or BC1 hybrid populations into transgenic and non-transgenic lineages10, 17–22 may create different genomic bases between the compared lineages for fitness evaluation. Therefore, the method may not be appropriate for the assessment of the environmental biosafety impact caused by transgene flow, even though it has been commonly applied to estimate fitness of a transgene(s) in different crop-wild and crop-weed hybrid combinations for decades10, 17–22. Thus, it is necessary to develop a more appropriate method for transgenic fitness evaluation, by considering differences in the genomic background between transgenic and non-transgenic hybrid lineages.

Interestingly, we also found preferential transmission of parental alleles into F2-F3 lineages in the transgene-free hybrid combinations, which was associated with the selection of a specific parental identifier. In other words, more alleles from a parent were detected at multiple loci in hybrid lineages having a neutral identifier from this specific parent, no matter it was used as a male or female parent. This result supports our third hypothesis about preferential allelic transmission from a parent, which is associated with the selection of an identifier from the specific parent. The preferential transmission of parental alleles at multiple loci is probably due to the positive selection or hitchhiking effect of these alleles that are genetically linked to the selected identifiers. The phenomena of association between the selected markers/genes and the genetically linked alleles in hybrid populations are widely reported in many plant species, such as rice and maize28, 32, 33. The observation demonstrates the critical role of artificial selection in increased frequencies of traits (genes) favored by human beings and other genetically linked alleles by the hitchhiking effect. In addition, model simulation also supported the presence of positive selection or “hitchhiking effect” between genetically linked alleles27, 34. The finding of preferential transmission of genetically linked alleles from a parent by selection may have its important implications in molecular marker-assisted selection in plant breeding, as indicated in the studies of tomatoes35, sour cherries36, rice37, and maize38. In addition, this finding has its significance in the studies of evolution under selection.

In summary, we found that using either a transgene or a neutral SSR marker as an identifier to separate a crop-wild or crop-weed hybrid population into transgene-present and -absent lineages/subpopulations can cause non-random transmission of the parental alleles at multiple loci, resulting in differences in the genomic background of the two hybrid lineages used for transgenic fitness evaluation. Our finding suggests that the commonly used method for transgene fitness assessment involving so-called isogenic F2/F3 or BC1 hybrid lineages with or without a transgene may not be appropriate for comparison, because of the differences in the genomic background of the compared hybrid lineages. We therefore propose that other means to evaluate fitness effects of transgene flow or introgression should be sought and designed to assess the environmental impact caused by crop-to-wild/weedy transgene flow, because the presumption of genomic equivalence between lineages of a segregated F2/F3 hybrid population cannot be justified. In addition, our finding of preferential parent-allele transmission into hybrid lineages at multiple loci also provides useful insights for understanding the strong effect of artificial selection of a marker (identifier), regardless of a transgene or a neutral allele, on parent-allele transmission into hybrid lineages. The generated knowledge also has important implications for molecular marker-assisted selection in plant breeding and for evolutionary studies by means of selection.

Methods

Creation of F2-F3 crop-wild and crop-weed hybrid lineages/groups

An herbicide-resistant GE rice line (EP3), its non-transgenic rice parent (Minghui-86), and a wild (one biotype from China, Jiangxi) and weedy rice accession (one biotype from Nepal), all containing the AA genome, were used to produce crop-wild/weedy hybrids. EP3 contained a transgene overexpressing epsps produced through agrobacterium-mediated transformation from Minghui-8639. EP3 was bred to T5 generation with one copy of the homozygous transgene40. For hybridization, cultivated rice line/variety was used as the male parents (pollen donors) and wild/weedy rice as the female parents (pollen recipients). All field experiments were conducted in the designated Biosafety Assessment Centers of Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Fuzhou, China.

For transgenic and non-transgenic hybrid combinations, F2 and F3 crop-wild and crop-weed descendants were included for analyses. The transgenic hybrid descendants were derived from F1 hybrids (~100 plants) between EP3 and wild or weedy rice independently through self-pollination. To create hybrid lineages (or subpopulations) with or without a transgene, we used the epsps transgene as an identifier to separate GE and non-GE lineages from the F2 (400 individuals) or F3 (600 individuals) crop-wild and crop-weed hybrid populations (Fig. 6a, identifier-based lineages). The presence and absence of the epsps transgene in each plant was identified through PCR (polymerase chain reactions) analyses following the method of Wang et al.21.

Figure 6.

Hybrid lineages (a) and ideal groups (b) created from an experimental hybrid population (F2 or F3) for analyses. Identifier represents either a transgene or a neutral marker that are used to separate hybrid lineages.

The non-transgenic F2 and F3 hybrid descendants were derived F1 hybrids (~100 plants) between Minghui-86 and wild or weedy rice independently through self-pollination. To create hybrid lineages with or without an identifier, we used neutral SSR markers as identifiers to separated identifier-present and -absent hybrid lineages from F2 (400 individuals) or F3 (600 individuals) hybrid populations (Fig. 6a, identifier-based lineages). These neutral SSR identifiers showed a Mendelian segregation pattern in the F2 and F3 crop-wild/weed hybrid populations. For the three sets of crop-wild hybrid lineages, three neutral SSR identifiers (RM572, RM408 and RM277) were used for PCR analyses41, while for the three sets of crop-weed hybrid lineages, other three neutral SSR identifiers (RM186, RM172, and RM3533) were used.

In addition, we also created ideal groups (or subpopulations) (Fig. 6b, random groups) from the F2 and F3 crop-wild/weedy hybrid populations, as a reference to the identifier-based lineages. To create the ideal groups, we randomly drew individuals from the F2 (400 individuals) or F3 (600 individuals) hybrid populations for ten times to ensure minimal variation (with standard deviation < 0.01) in parent-allele frequencies between the two ideal groups (group-1 and -2) in each hybrid populations.

PCR amplification and data collection

Total genomic DNA of all F2 and F3 crop-wild/weed hybrid samples were extracted from leaf tissues followed the CTAB protocol of Murray & Thompson42. Fifty-two and 32 rice SSR markers that were randomly distributed on the rice genome with physical distances > 800, 000 bp (Fig. 3) and polymorphic between the cultivated rice and wild/weedy rice parents were included for analyses. SSR markers were selected from the Gramene Database (http://www.gramene.org), with information on their primer sequences (Supplementary Table 7). The forward primers were fluorescently labeled to visualize the PCR products by FAM (blue), ROX (red), or JOE (green)41, 43. PCR was carried out using a 2720 Thermal Cycler Set (Applied Biosystems) following the method of Jiang et al. (2012) and Yang et al. (2014)41, 43. PCR products were separated by capillary electrophoresis with fluorescence on an ABI 3130 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The electrophoretic outputs were scored as genotype data using the software GeneMapper version 4.0 (Applied Biosystems). Frequencies of parental alleles in hybrid lineages at each locus were calculated to estimate allele transmission.

Data analysis

The diversity coefficient (F st) between hybrid lineages/groups was analyzed using the software GenAlEx version 6.5 to estimate their genetic differentiation44. The bootstrap percentile method (BPM)45, 46 was used to determine differences in frequencies of parental alleles at each SSR loci between crop-wild/weed hybrid lineages/groups, at the significant level of P < 0.05. The sampling size for bootstrap of each hybrid lineage/group was determined by its sample size45, 46, with re-sampling replicates for 10,000, using the Microsoft Excel 2013 Visual Basic for Applications47. The one-tail paired t test was applied to determine differences in average frequencies of parental alleles between hybrid lineages with or without the crop or wild/weedy identifiers for the loci with significant differences in parental allele frequencies based on the BPM analyses. The neutrality test was conducted to test the deviation of alleles from the theoretical values at each locus in corresponding hybrid lineages/groups through 1,000 simulations using the program PopGene Version 1.3148, at the significant level of P < 0.05.

Data availability

Files with data are available on Data Dryad.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (#31330014) and the National Program of Development of Transgenic New Species of China (2017ZX08011–006). F. Wang and J. Su kindly provided epsps transgenic rice line (EP3).

Author Contributions

Z.W. conducted the experiment and wrote the paper. L.W. and Z.W. conducted the experiment and analyzed data. B.-R.L. conceived and designed the experiment, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-10596-4

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Spencer LJ, Snow AA. Fecundity of transgenic wild-crop hybrids of Cucurbita pepo (Cucurbitaceae): implications for crop-to-wild gene flow. Heredity. 2001;86:694–702. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart CN, Halfhill MD, Warwick SI. Transgene introgression from genetically modified crops to their wild relatives. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003;4:806–817. doi: 10.1038/nrg1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hails RS, Morley K. Genes invading new populations: a risk assessment perspective. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005;20:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu B-R, Snow AA. Gene flow from genetically modified rice and its environmental consequences. BioScience. 2005;55:669–678. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[0669:GFFGMR]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu B-R, Yang C. Gene flow from genetically modified rice to its wild relatives: Assessing potential ecological consequences. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009;27:1083–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellstrand NC, et al. Introgression of crop alleles into wild or weedy populations. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2013;44:325–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110512-135840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andow DA, Zwahlen C. Assessing environmental risks of transgenic plants. Ecol. Let. 2006;9:196–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snow AA, Andersen B, Jørgensen RB. Costs of transgenic herbicide resistance introgressed from Brassica napus into weedy B. rapa. Mol. Ecol. 1999;8:605–615. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00596.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia H, Chen L, Feng W, Lu B-R. Yield benefit and underlying cost of insect-resistance transgenic rice: Implication in breeding and deploying transgenic crops. Field Crop. Res. 2010;118:215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2010.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke JM, Rieseberg LH. Fitness effects of transgenic disease resistance in sunflowers. Science. 2003;300:1250–1250. doi: 10.1126/science.1084960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenczewski E, Ronfort J, Chèvre AM. Crop-to-wild gene flow, introgression and possible fitness effects of transgenes. Environ. Biosafety Res. 2003;2:9–24. doi: 10.1051/ebr:2003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu B-R, Yang X, Ellstrand NC. Fitness correlates of crop transgene flow into weedy populations: a case study of weedy rice in China and other examples. Evol. Appl. 2016;9:857–870. doi: 10.1111/eva.12377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darmency H, Lefol E, Fleury A. Spontaneous hybridizations between oilseed rape and wild radish. Mol. Ecol. 1998;7:1467–1473. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00464.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halfhill MD, et al. Growth, productivity, and competitiveness of introgressed weedy Brassica rapa hybrids selected for the presence of Bt cryIAc and gfp transgenes. Mol. Ecol. 2005;14:3177–3189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchs M, Chirco EM, Mcferson JR, Gonsalves D. Comparative fitness of a wild squash species and three generations of hybrids between wild×virus-resistant transgenic squash. Environ. Biosafety Res. 2004;3:17–28. doi: 10.1051/ebr:2004004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snow AA, et al. A Bt transgene reduces herbivory and enhances fecundity in wild sunflowers. Ecol. Appl. 2003;13:279–286. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2003)013[0279:ABTRHA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guadagnuolo R, Clegg J, Ellstrand NC. Relative fitness of transgenic vs. non-transgenic maize x teosinte hybrids: a field evaluation. Ecol. Appl. 2006;16:1967–1974. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[1967:RFOTVN]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang X, et al. Transgenes for insect resistance reduce herbivory and enhance fecundity in advanced generations of crop-weed hybrids of rice. Evol. Appl. 2011;4:672–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2011.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, et al. Limited ecological risk of insect-resistance transgene flow from cultivated rice to its wild ancestor based on life-cycle fitness assessment. Sci. Bull. 2016;61:1440–1450. doi: 10.1007/s11434-016-1152-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia H, et al. Ambient insect pressure and recipient genotypes determine fecundity of transgenic crop‐weed rice hybrid progeny: Implications for environmental biosafety assessment. Evol. Appl. 2016;9:847–856. doi: 10.1111/eva.12369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang W, et al. A novel 5-enolpyruvoylshikimate-3-phosphate (EPSP) synthase transgene for glyphosate resistance stimulates growth and fecundity in weedy rice (Oryza sativa) without herbicide. New Phy. 2014;202:679–688. doi: 10.1111/nph.12428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang X, et al. Efficacy of insect-resistance Bt/CpTI transgenes in F5–F7 generations of rice crop–weed hybrid progeny: implications for assessing ecological impact of transgene flow. Sci. Bull. 2015;60:1563–1571. doi: 10.1007/s11434-015-0885-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu B-R, Naredo ME, Juliao A, Jackson MT. Hybridization of AA genome rice species from Asia and Australia. II. Meiotic analysis of Oryza meridionalis and its hybrids. Genet. Resours. Crop Ev. 1997;44:25–31. doi: 10.1023/A:1008699705881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu B-R, Naredo MEA, Juliao, Jackson. MT. Taxonomic status of Oryza glumaepatula Steud. a diploid wild rice species from the New World. III. Assessment of genomic affinity among rice taxa from South America, Asia and Australia. Genet. Resours. Crop Ev. 1998;45:215–223. doi: 10.1023/A:1008686517357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim Y, Stephan W. Joint effects of genetic hitchhiking and background selection on neutral variation. Genetics. 2000;155:1415–1427. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.3.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nuzhdin SV, Harshman LG, Zhou M, Harmon K. Genome-enabled hitchhiking mapping identifies QTLs for stress resistance in natural. Drosophila. Heredity. 2007;99:313–321. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6801003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan NL, Hudson RR, Langley CH. “The hitchhiking effect” revisited. Genetics. 1989;123:887–899. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olsen KM, et al. Selection under domestication: Evidence for a sweep in the rice Waxy genomic region. Genetics. 2006;173:975–983. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.056473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baack EJ, Sapir Y, Chapman MA, Burke JM, Rieseberg LH. Selection on domestication traits and quantitative trait loci in crop-wild sunflower hybrids. Mol. Ecol. 2008;17:666–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hooftman DAP, et al. Locus-dependent selection in crop-wild hybrids of lettuce under field conditions and its implication for GM crop development. Evo. Appl. 2011;4:648–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2011.00188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Remington DL, et al. Structure of linkage disequilibrium and phenotypic associations in the maize genome. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:11479–11484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201394398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark RM, Linton E, Messing J, Doebley JF. Pattern of diversity in the genomic region near the maize domestication gene tb1. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:700–707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237049100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palaisa K, Morgante M, Tingey S, Rafalski A. Long-range patterns of diversity and linkage disequilibrium surrounding the maize Y1 gene are indicative of an asymmetric selective sweep. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:9885–9890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307839101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stephan W, Song YS, Langley CH. The hitchhiking effect on linkage disequilibrium between linked neutral loci. Genetics. 2006;172:2647–2663. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.050179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fulton TM, et al. QTL analysis of an advanced backcross of Lycopersicon peruvianum to the cultivated tomato and comparisons with QTLs found in other wild species. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1997;95:881–894. doi: 10.1007/s001220050639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang D, Karle R, Iezzoni AF. QTL analysis of flower and fruit traits in sour cherry. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000;100:535–544. doi: 10.1007/s001220050070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guan YS, et al. Simultaneously improving yield under drought stress and non-stress conditions: a case study of rice (Oryza sativa L.) J. Exp. Bot. 2010;61:4145–4156. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamasaki M, Wright SI, McMullen MD. Genomic screening for artificial selection during domestication and improvement in maize. Ann. Bot-London. 2007;100:967–973. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu JW, Feng DJ, Li XG, Chang TJ, Zhu Z. Cloning of genomic DNA of rice 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase gene and chromosomal localization of the gene. Sci. Sin. 2002;45:251–259. doi: 10.1360/02yc9028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su, J., Chen, G. M., Tian, D. G., Zhu, Z. & Wang, F. A gene encodes 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate mutagenized by error-prone PCR conferred rice with high glyphosate-tolerance. Mol. Plant Breed. 6, 830–836 (2008).

- 41.Yang C, Wang Z, Yang X, Lu B-R. Segregation distortion affected by transgenes in early generations of rice crop-weed hybrid progeny: Implications for assessing potential evolutionary impacts from transgene flow into wild relatives. J. Syst. Evol. 2014;52:466–476. doi: 10.1111/jse.12078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray MG, Thompson WF. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:4321–4326. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang ZX, Xia HB, Basso B, Lu B-R. Introgression from cultivated rice influences genetic differentiation of weedy rice populations at a local spatial scale. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012;124:309–322. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1706-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peakall R, Smouse PE. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research-an update. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2537–2539. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Efron B. Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Ann. Stat. 1979;7:1–26. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176344552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hall, P. & Martin, M. A. A note on the accuracy of bootstrap percentile method confidence intervals for a quantile. Stat. Probabil. Lett. 8, 197–200 (1989).

- 47.Jacobson, R. Microsoft Excel 2000/Visual Basic for Applications Fundamentals. Microsoft Press (1999).

- 48.Yeh, F. C., Yang, R. C. & Boyle, T. POPGENE version 1.31. Microsoft Window-based freeware for population genetic analysis. https://sites.ualberta.ca/~fyeh/popgene.html/ (Accessed on 2017, 02, 09).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Files with data are available on Data Dryad.