Abstract

Introduction:

Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (LPRD) referes to an inflammatory reaction of the mucous membrane of pharynx, larynx and other associated respiratory organs, caused by a reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus. LPRD is considered to be a relatively new clinical entity with a vast number of clinical manifestations which are treated through different fields of medicine, often without a proper diagnosis. In gastroenterology it is still considered to be a manifestation of GERD, which stands for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Patients suffering from LPRD communicate firstly with their primary physicians, and since further treatment might ask for a multidisciplinary approach, it is important to have a unified approach among experts when treating these patients.

Goal:

This paper is written with the intention to assess the frequency of symptoms of LPR in family medicine, possible diagnostics and adequate treatment in primary health care.

Materials and methods:

This is a prospective, descriptive cohort study. Authors used „The Reflux Symptom Index” (RSI) questionnaire. Examinees were all patients who reported to their family medicine office in Gracanica for the first time with new symptoms during a period of one year. Patients with positive results for LPR (over 13 points) were treated in accordance with the suggested algorithm and were monitored during the next year.

Results:

Out of 2123 examinees who showed symptoms of LPR, 390 tested positive according to the questionnaire. This group of examinees were treated in accordance with all suggested protocols and algorithms. 82% showed signs of improvement as a response to basic treatment provided by their physicians.

Conclusion:

Almost every fifth patient who reports to their family medicine physician shows symptoms of LPR. On primary health care levels it is possible to establish some form of prevention, diagnostics and therapy for LPR in accordance with suggested algorithms. Only a small number of patients requires procedures which fall under other clinical fields.

Keywords: LPR, GERD, family medicine, diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm

1. INTRODUCTION

Stomach content reflux into the esophagus with pathohistological changes of the mucous membrane of the esophagus and it’s clinical manifestations is defined as Gastroedophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). Diagnostic and therapeutic procedures for GERD are precisely defined (1, 2). Stomach content reflux outside of the esophagus and into respiratory organs is most commonly manifested as laryngeal symptoms such as coughing, hoarseness, dysphagia, globus and sore throat, but there can be signs of nose, sinus and lung infections. Epidemiological studies have shown that the prevalence of this syndrome is extremely high, that it has certain characteristics of an outbreak and that it is one of the most common causes of patient visits to their family medicine physicians, but also to laryngologists, gastroenterologists, pediatricians, pulmonologists and psychiatrists (1, 2, 3, 4). Today it has been proven that gastroesophageal reflux is not the only cause of LPR. LPR is a multifactorial syndrome with a vast clinical representation, during the disease and with complications, so it requires a multidisciplinary approach. Based on newly discovered facts about the specific ethiopatogenesis of the disease, LPR is considered a new clinical entity (4, 5, 6). GERD is caused by the lower esophageal sphincter dysfunction and the dysfunction of the stomach emptying mechanism. Esophageal mucosa has protective mechanisms against aggressive factors of the stomach content (mucosal barrier) and it remains intact when a physiological reflux occurs, which normally happens at night. Laryngeal and pharyngeal mucosa do not possess these protective mechanisms and acidopeptic activity of the stomach content quickly leads to mucosal lesions. Laryngeal and pharyngeal reflux occurs most commonly during the day as a result of the upper esophageal sphincter dysfunction. However, acidity of the stomach content is not the only cause of LPR. Pepsin with its proteolytic effects can be the determining factor. Other possible etiological factors are pancreatic proteolytic enzymes, bile salts and bacteria (1, 6, 7). Extraesophageal manifestations of stomach content reflux have only recently started being seen as important based on the assumption of their important role in causing respiratory tract diseases. In clinical practice, LPR is mostly not recognized because it is a “silent reflux” and diagnostic and therapeutical protocols are inadequate, so proper treatment is usually delayed. Laryngeal symptoms are most common, so patients are treated by otolaryngologists. Otolaryngologists have developed a diagnostic Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) based on the importance of certain disease symptoms and Reflux Finding Score (RFS) based on frequency of pathological changes determined by laryngoscopy (9). Considering the high prevalence of the disease and uncharacteristic clinical image, most patients report to their family medicine physicians (7, 8, 11). For family medicine physicians LPR represents an important medical problem and a challenge in fast diagnostics, proper treatment and proper selection of patients who require additional multidisciplinary diagnostic procedures. Knowledge of etiopathogenesis of the disease and its clinical manifestations can help physicians in creating a proper program for prevention, early diagnosis and adequate therapy for LPRD. Untreated LPR can be one of the etiological causes of laryngeal cancer. The development of the disease can be benign or malignant and life threatening, and all of its forms can considerably affect life quality in patients. Laryngeal pathological changes can be discovered with laryngoscopy, and some even with detailed esophagoscopy. These changes are described as edema, hyperemia or erythema of the vocal chords and laryngeal edges, ventricular obliteration, granulation, presence of dense endolaryngeal secretion and hypertrophy of the posterior commissure (2, 9). Proper diagnosis of LPRD represents a challenge for family medicine physicians. A large number of clinical studies confirmed low specificity and sensitivity of diagnostic tests such as laryngoscopy, esophagogastroscopy, proximal pH monitoring (hypopharyngeal and oropharyngeal). Evaluation of symptoms using the Reflux Symptom Index is considered to be the basic diagnostic procedure. A newer method of determining pepsins in spit - peptest, can confirm LPR diagnosis because its sensitivity and specificity is 87% (10). This test is a fast non-invasive method and could have a wide variety of uses in primary health care. LPR therapy is complex and requires modification of patient’s lifestyle and habits. Body weight reduction and physical activity, quitting cigarettes and alcohol use are one of the first steps in lowering the intesity of symptoms in patients (11). Nutritional interventions with proper food choices and bowel movement regulation lead to lowering dyspeptic difficulties, but also lower the number of reflux episodes. Emptying of the bowels causes lower intra-abdominal pressure, which leads to lower possibility of stomach content reflux into the esophagus, larynx and pharynx. Obesity, or more accurately high BMI, is an independent factor in stomach reflux occurrence because of its specific effect mechanism on the gastroesophageal juncture (11).

LPR treatment and management is supposed to reduce the acidity or stomach contents and neutralize acidopeptidic activity in larynx, pharynx and esophagus. High dosages of PPI (proton pump inhibitors) have shown the best effects in reducing reflux in the course of 24 hours. Alkaline water and alginates show a positive additional effect in lowering acidopeptidic activity in the larynx and pharynx. Patients are supposed to have long-term treatment during the course of 6 months because of high sensitivity of the mucosal membrane in the stomach and pharynx. Difficult cases with a proven hiatal hernia can be considered for surgical treatment as well (6).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

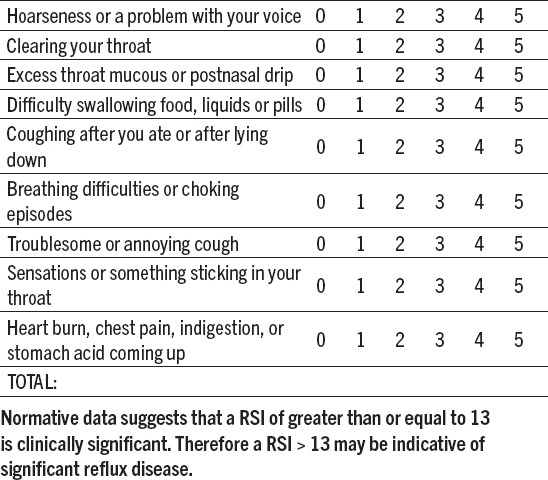

This paper is a prospective descriptive study with an analisis of subjective difficulties following a specialized questionnaire about the presence of LPR. The questionnaire evaluates 9 subjective difficulties which are characteristic for the clinical image of LPR, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

RSI questionnaire by Belafsky (9)

Questionnary for Reflux Symptom Index

Name: ____________________________________ Date: ___/___/____

Within the last month, how did the following problems affect you? (0-5 rating scale with O= No problem and 5 = Severe)

This study was conducted during a period of one year (from October 1st, 2015 to September 39th, 2016.) in the Polyclinic “Medicus A”, Gracanica, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Examinees were all patients who reported to their family medicine surgery in Gračanica for the first time with new symptoms during a period of one year. Patients with positive results for LPR (over 13 points) were treated in accordance with the suggested algorithm and were monitored during the next year.

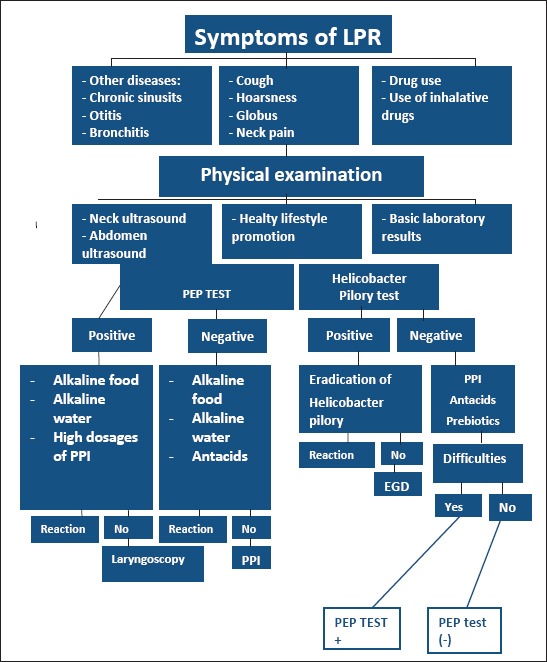

As the algorithm shows (Figure 1), additional searches have excluded other neck diseases, as well as other respiratory and digestive tract diseases. Patients with symptoms of LPR were first educated about healthy lifestyles and habits and the importance of regulating and monitoring the whole digestive system and then they were put on an epmpirical treatment with high dosages of protein pump inhibitors, alginates and alkaline water. Nutritional interventions were implemented as needed. Patients were monitored during the course of the next 6 months. Those who showed alarming symptoms and incomplete response to procedures and druges were reffered to additional searches and consultations (esophagoscopy, ORL consultations and laryngoscopy, peptest and consultations with pulmonologists).

Figure 1.

Optimal diagnostic and therapeutical approach to LPR in primary health care

3. RESULTS

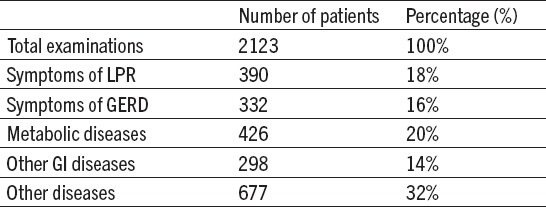

The Table 2 shows the frequency of symptoms of LPR in relation to others symptoms of different diseases. 390 patients showed symptoms of LPR, which is 18% of those who reported to their family medicine physicians. Patients with dominant difficulties or esophageal refluxs constite 16% of all patients, or 332 patients.

Table 2.

Frequency of LPR symptomes in a “Medicus A” polyclinic Gracanica during the course of 12 months

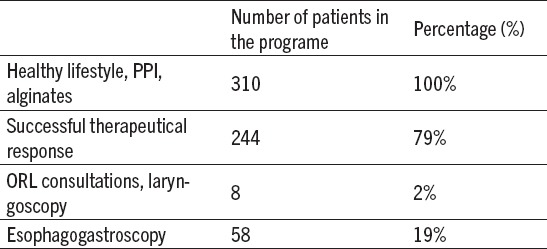

Table 3.

The clinical course after implementation a diagnostic-therapeutic program

During the 6 months course of this study which followed patients with symptoms of LPR those who followed the program showed significant improvement (79% of patients). 58 patients were reffered to further gastroenterological examinations and 8 to otorhinolaryngological examinations (Table 2).

Esophagogastroscopy determined laryngeal changes in 10 patients which could be consistent with LPRD.

Results of clinical monitoring of these patients indicate that there is a possibility of early discovery, adequate prevention and treatment of patients with symptoms of LPR on primary health care levels. Applied algorithm of necesarry diagnostic and therapeutical procedures for patients with symptoms of LPR according to Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) is shown in Figure 1. Use of this algorithm enables optimal treatment for most patients.

4. DISCUSSION

Clinical manifestations of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) are classified as esophageal and extraesophageal syndroms, according to the latest clinical guides (2). Stomach content reflux outside of the esophagus causes a number of pathological changes, but it especially affects respiratory organs and it is therefore considered as a separate disease known as Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease (LPRD). Symptoms of this disease are a common occurence in general population, so it is considered to be one of the most common reasons patients report to their family medicine physicians. This study presented that out of 2123 examinees 18% showed symptoms of LPRD and 16% showed symptoms of GERD. European epidemiological studies have also shown that there is a high prevalence of symptoms related to both of these diseases. Symptoms of LPR are unspecific and can be a characteristic of various diseases, which is also shown in the results of this study. Occurence of these symptoms is related to different lifestyles and habits, so it is clear that increase in obesity prevalence and reduced physical activity have led to an increase in number of patients with GERD and LPR symptomes, especially in western countries (3, 4).

Safe standarnd diagnostic procedures which could precisely determine all forms of LPR have still not been established (1, 3). Evaluation of clinical symptoms is considered to be crucial in determining the correct diagnosis, as well as a therapeutical test with protone pump inhibitors and alginates which is easily applied in primary health care (12, 13). Belafsky, an American physician, has systematised 9 most common occurences in the form of a Reflux Symptom Index (RSI). Based on the number of this index a physician can either confirm or rule out existence of LPR. (Score of 13 or higher.) (9) The same principle is used in this study. Pathological findings using laryngoscopy have also been systematised in a questionnaire by the same author known as Reflux Finding Score (RFS), which can also help in determining the existence of LPR. Only a small number of participants in this study has been referred to laryngoscopy. Measuring of esophageal and pharyngeal pH is an addition in diagnosing LPR, but it is difficult to perform on primary health care levels. To prove the existence of hiatal hernia and esophagel reflux disease the patient needs to undergo esophagogastroscopy.

The test which confirms the presence of pepsins in spit (peptest) is important as it can be applied in primary health care. Gastric pepsinogen is activated only in acidic enviroment, so the presence of pepsin in spit indicates that there is a reflux of acidic stomach content into the respiratory tract. This test is simple, non-invasive and could be the determining factor in final diagnosis of LPR (10).

Patients who took part in this study and showed symptoms of LPR were first treated with nonpharmacological ways: dietary recommendations for weight reduction, stool regulations, reducing alcohol usage and quitting smoking. Diagnostic-therapeutical test with protone pump inhibitors in high dosages and with longterm usage, alginates and alkaline food and water contributed to successful treatment of these patients. Other authors have gotten similar results (1, 3, 8, 11). However, there have been studies which had contrary results in regards to the usage of protone pumps inhibitors in treating LPRD.

5. CONCLUSION

Almost every fifth patient who reports to their family medicine physician shows symptoms of LPR. On primary health care levels it is possible to establish some form of prevention, diagnostics and therapy for LPR in accordance with suggested algorithms. Only a small number of patients requires procedures which fall under other clinical fields.

Footnotes

• Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capagnolo AM, Priston J, Heidrichthoen R, Medeiros T, Assuncao RA. Laryngopharyngeal Reflux: Diagnosis, Treatmen and Latest research. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014 Apr;18(2):184–91. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1352504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sidhwa F, Moore A, Alligood E, Fisichella PM. Diagnosis and Treatment of the Extraesophageal Manifestations of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Ann Surg. 2017 Jan;265(1):63–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–17. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koufman JA. Laryngopharyngeal reflux 2002: A new paradigm of airway disease. ENT Ear Nose Throat J. 2004;(Suppl) article 1 0209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saritas Yuksel E, Vaezi MF. New developments in extraesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;8:590–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barry DW, Vaezi MF. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: more questions than answers. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77:327–34. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.77a.09121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abou-Ismail A, Vaezi MF. Evaluation of patients with suspected laryngopharyngeal reflux: a practical approach. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13:213–8. doi: 10.1007/s11894-011-0184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Amin MR, Koufman JA. Symptoms and findings of laryngopharyngeal reflux. ENT Ear Nose Throat J. 2004;(Suppl) article 3 0209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saritas Yuksel E, Hong SK, Strugala V, et al. Rapid salivary pepsin test: blinded assessment of test performance in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1312–6. doi: 10.1002/lary.23252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinucci I, de Bortoli N, Savarino E, Nacci A, Romeo SO, Bellini M, Savarino V, Fattori B, Marchi S. Optimal treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2013 Nov;4(6):287–301. doi: 10.1177/2040622313503485. doi:10.1177/2040622313503485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gikas A, Triantafillidis JK. The role of primary care physicians in early diagnosis and treatment of chronic gastrointestinal diseases. Int J Gen Med. 2014;13(7):159–73. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S58888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salihefendic N, Zildzic M, Cabric E. A New Approach to the Management of Uninvestigated Dyspepsia in Primary Care. Med Arh. 2015 Apr;69(2):133–4. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2015.69.133-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]