Abstract

Concerns regarding metal-on-metal (MoM) bearing couples in total hip arthroplasty are well documented in the literature with cobalt (Co) and chromium (Cr) toxicity causing a range of both local and systemic adverse reactions. We describe the case of a patient undergoing cardiac transplantation as a direct result of Co and Cr toxicity following a MoM hip replacement. Poor implant positioning led to catastrophic wear generating abundant wear particles leading to Co and Cr toxicity, metallosis, bony destruction, elevated metal ion levels, and adverse biological responses. Systemic symptoms continued for 3 years following cardiac transplantation with resolution only after revision hip arthroplasty. There was no realization in the initial cardiac assessment and subsequent transplant workup that the hip replacement was the likely cause of the cardiac failure, and the hip replacement was not recognized as the cause until years after the heart transplant. This case highlights the need for clinicians to be aware of systemic MoM complications as well as the importance of positioning when using these prostheses.

Keywords: Arthroplasty, Complications, Heart transplant, Cobalt, Chromium, Toxicity

Introduction

There are well-documented reports of cobalt (Co) toxicity and its effects on the body [1], [2]. Local accumulation can lead to local inflammatory responses, metallosis, and tissue lesions [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. Systemic damage may include the respiratory system, the endocrine system, the nervous system and the cardiovascular system (directly affecting myocardium) [2], [7], [8], [9], [10]. There has been a large case body relating to cardiomyopathy in people linked to consumption of chromium-laced beer back in the mid-twentieth century some of which were fatal [11], [12], [13], [14]. It has similar constitutional symptoms to many other metal toxicities [15].

Chromium (Cr) toxicity is primarily related to levels of the oxidative states IV and V. These are the primary forms released in prosthesis wear [16]. Cr toxicity is associated with a wide range of pathology particularly in relating to being proinflammatory and immunosuppressive. It affects B- and T-cell lymphocyte levels, DNA repair, iron and heme utilization, and renal function [17].

Metal-on-metal (MoM) implants are known to be sensitive to implant malposition potentially causing local and systemic reactions [2], [18], [19]. One study demonstrated that hips revised due to pseudo tumors had higher wear rates and another study, a direct correlation with MoM resurfacing and pseudo tumors [3], [4].

Case history

A 58-year-old woman from a rural center underwent a primary MoM resurfacing total hip replacement for osteoarthritis in 2003. Her immediate postoperative recovery was uneventful and she had satisfactory functional scores and was discharged. The acetabular component positioning was suboptimal (Fig. 1) and resulted in eccentric wear (Figs. 2 and 3), local metallosis (Fig. 4), and systemic Co and Cr toxicity.

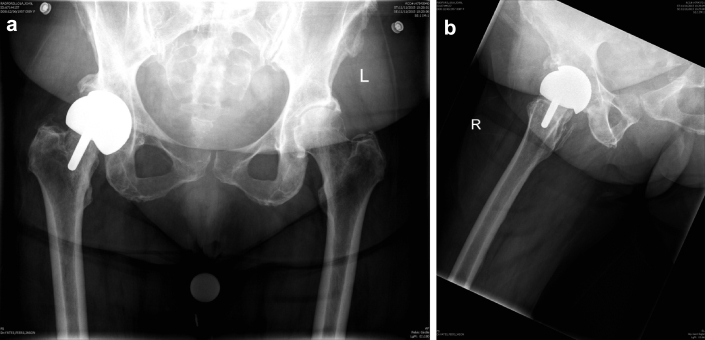

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior pelvis (a) and frog lateral (b) radiographs showing primary right hip resurfacing.

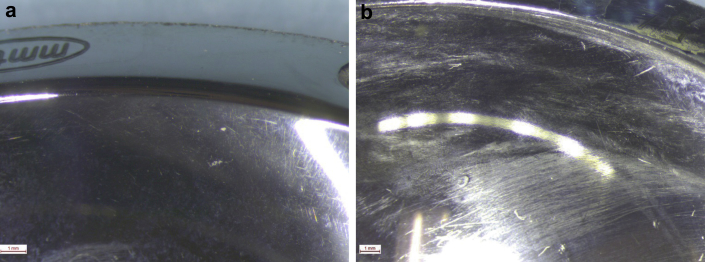

Figure 2.

(a and b) Acetabula-bearing surface demonstrating edge loading with wearing.

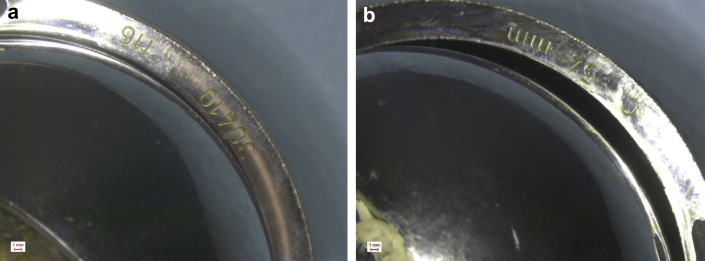

Figure 3.

(a and b) Localized edge loading resulting in loss of sphericity in both components.

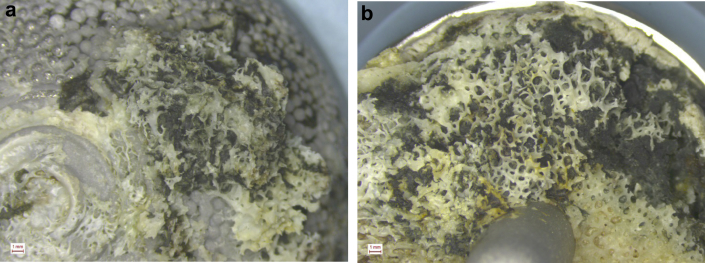

Figure 4.

Cup ingrowth (a) and under surface of head (b) showing stained bone and fibrous tissue.

Ten years later, the patient presented with heart failure symptoms due to nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy with severe biventricular dysfunction (New York Heart Association functional score of III). The etiology remained obscure with suspicion of amyloid fibrotic process on magnetic resonance imaging and a presumed idiopathic fibrosing cardiomyopathy with myocyte disarray on biopsy. Initial investigations in December 2012 demonstrated elevated serum Co 169 ppb (acceptable for MoM total hip arthroplasty <7 ppb) and Cr 31 ppb (acceptable for MoM total hip arthroplasty <7 ppb). Discussions regarding chelation therapy were made at this time, however, were not undertaken as she underwent urgent cardiac transplantation in February 2013 due to hemodynamic instability with multi-organ failure, particularly renal and hepatic.

The patient's cardiac symptoms stabilized following a stormy postoperative course complicated by acute renal failure and bilateral subclavian thromboses. Ongoing outpatient cardiology review was satisfactory with echocardiogram findings in March 2015 confirming normal left ventricular systolic function and mild to moderate right ventricular dysfunction with pulmonary artery systolic pressures of 27 mmHg.

In October 2015, she was referred by her cardiology team for orthopaedic opinion in regard to expedient surgical intervention to minimize and reverse presumed Co and Cr toxicity affecting her new heart. The decision was made for removal of acetabular and femoral Co and Cr components. This occurred in November 2015 with revision to DePuy Synthes modular system with ceramic head. Intraoperative findings were poor position of implant placement with tissue staining, metallosis, granuloma, and osteolysis with bearing failure. Her postoperative period was complicated by admission to intensive care unit for inotropic support and severe granulocyte colony-stimulating factor induced neutropenia.

Review at 6 months postrevision arthroplasty has been promising with echocardiogram in June 2016 demonstrating normal left ventricular size, wall thickness, and hyperdynamic systolic function and pulmonary pressures returning to normal. She is progressing well regarding her total hip replacement. Although she does describe some pain around the buttock area, this was more severe in nature a couple of months ago and has since improved. Her serum Co and Cr levels have returned to normal.

Discussion

This case demonstrates the cardiovascular side effects of Co and Cr toxicity. The patient developed progressive cardiac failure in the period preceding her primary MoM arthroplasty and with documented elevated serum Co and Cr levels. There are previous case reports of cardiac disease in the context of arthroplasty wear; however, a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology is lacking [20]. Co infiltration and accumulation in cardiac myocytes is thought to cause dilated cardiomyopathy. It can be difficult to identify, as the histologic progression is often undifferentiated fibrosis.

The patient's cardiac pathophysiology appeared to return post-transplant and was concurrent with a persistent Co and Cr serum elevation and that her function improved following the revision of her arthroplasty and reduction of her serum Co levels. We posit this is suggestive of reversible cardiovascular changes in relation to toxic metal levels and that it is possible, with a comprehensive initial assessment and with an awareness of implant-related toxicity, that the patient could have avoided cardiac transplant by having the required hip replacement revision given awareness and detection of early symptoms.

Summary

This case highlights the need for doctors to be aware of arthroplasty wear and metal toxicity particularly when there is a disease process of unclear etiology and in the importance of surgeon skill and positioning of articulating implants. Patients with MoM replacements should be carefully assessed for potential benefit from revision when presenting with pathophysiology attributable to metal ions.

Footnotes

No author associated with this paper has disclosed any potential or pertinent conflicts which may be perceived to have impending conflict with this work. For full disclosure statements refer to http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.artd.2017.01.005.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Voleti P.B., Baldwin K.D., Lee G.-C. Metal-on-metal vs conventional total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(10):1844. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amstutz H.C., Le Duff M.J., Campbell P.A., Wisk L.E., Takamura K.M. Complications after metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2011;42(2):207. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandit H., Glyn-Jones S., McLardy-Smith P. Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90-B(7):847. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwon Y.-M., Glyn-Jones S., Simpson D.J. Analysis of wear of retrieved metal-on-metal hip resurfacing implants revised due to pseudotumours. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92-B(3):356. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B3.23281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yanny S., Cahir J.G., Barker T. MRI of aseptic lymphocytic vasculitis–associated lesions in metal-on-metal hip replacements. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(6):1394. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khair M.M., Nam D., DiCarlo E., Su E. Aseptic lymphocyte dominated vasculitis-associated lesion resulting from trunnion corrosion in a cobalt-chrome unipolar hemiarthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(1):196.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simonsen L.O., Harbak H., Bennekou P. Cobalt metabolism and toxicology—a brief update. Sci Total Environ. 2012;432:210. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olivieri G., Hess C., Savaskan E. Melatonin protects SHSY5Y neuroblastoma cells from cobalt-induced oxidative stress, neurotoxicity and increased β-amyloid secretion. J Pineal Res. 2001;31(4):320. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2001.310406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhardwaj N., Perez J., Peden M. Optic neuropathy from cobalt toxicity in a patient who ingested cattle magnets. Neuro Ophthalmol. 2011;35(1):24. doi: 10.3109/01658107.2010.518334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devlin J.J., Pomerleau A.C., Brent J. Clinical features, testing, and management of patients with suspected prosthetic hip-associated cobalt toxicity: a systematic review of cases. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9(4):405. doi: 10.1007/s13181-013-0320-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figueredo V.M. Chemical cardiomyopathies: the negative effects of medications and nonprescribed drugs on the heart. Am J Med. 2011;124(6):480. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee W.K., Regan T.J. Alcoholic cardiomyopathy: is it dose-dependent? Congest Heart Fail. 2002;8(6):303. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2002.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Machado C., Appelbe A., Wood R. Arthroprosthetic cobaltism and cardiomyopathy. Heart Lung Circ. 2012;21(11):759. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zywiel M.G., Brandt J.-M., Overgaard C.B. Fatal cardiomyopathy after revision total hip replacement for fracture of a ceramic liner. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(1):31. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B1.30060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duruibe J., Oguwuegbu M., Egwurugwu J. Heavy metal pollution and human biotoxic effects. Int J Phys Sci. 2007;2:112. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merritt K., Brown S.A. Release of hexavalent chromium from corrosion of stainless steel and cobalt-chromium alloys. J Biomed Mater Res. 1995;29(5):627. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820290510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keegan G.M., Learmonth I.D., Case C.P. Orthopaedic metals and their potential toxicity in the arthroplasty patient. A review of current knowledge and future strategies. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(5):567. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B5.18903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langton D.J., Jameson S.S., Joyce T.J. Early failure of metal-on-metal bearings in hip resurfacing and large-diameter total hip replacement. A consequence of excess wear. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(1):38. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B1.22770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith A.J., Dieppe P., Vernon K., Porter M., Blom A.W. Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements: analysis of data from the National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1199. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60353-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradberry S.M., Wilkinson J.M., Ferner R.E. Systemic toxicity related to metal hip prostheses. Clin Toxicol. 2014;52(8):837. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.944977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.