Abstract

The Arab cultural heritage was an era of invaluable preservation and development of numerous teachings, including biomedical sciences. The golden period of Arab medicine deserves special attention in the history of medicine and pharmacy, as it was the period of rapid translation of works from Greek and Persian cultures into Arabic. They preserved their culture, and science from decay, and then adopted them to continue building their science on theirs as a basis. After the fall of Arabian Caliphate, Arabian pharmacy, continued to persevere, and spread through Turkish Caliphate until its fall in the First World War. That way, Arabian pharmacy will be spread to new areas that had benefited from it, including the area of occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina. Because of the vast territorial scope of the Ottoman Empire, the focus of this paper is description of developing pharmacy in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the time of Ottoman reign.

Keywords: Arabian pharmacy, Ottoman Empire, Bosnia and Herzegovina

1. INTRODUCTION

Science in its entirety represents a continuity in understanding of scientific phenomena, made possible by earlier accomplishments by countless earlier civilizations (1-4). Since the beginning of man many civilizations pursued knowledge. For example Sumerian, Egyptian and Babylonian civilizations paved the way for Greek and Roman civilizations. After their downfall, all the scientific accomplishments were collected and preserved by Arab civilization in 8th century, who not only translated the writings, but also enhanced the findings, by review and with their own scientific findings. From the Arabs the knowledge was passed on to the western countries (1, 2). One of the reasons for the prosperity of the science is that Islam, as the dominate religion in Arabia, encouraged the scientists to research and improve, as it considered the knowledge being a path to the truth, and therefore towards God. With the Arabian conquest science spread to the conquered areas, such as Asia, and Mediterranean. In conquered countries Arabs encountered many different cultures and founded translation schools which translated all the recorded science into Arabic language. Among the first translated works were findings of great importance for the development of pharmacy. Some of those works are, for example a book about herbs, form Greek Theόphrastos, or the “De Materia Medica” from Dioscorides (Figure 1), which envelops the entirety of ancient pharmacy and drugs. By acquiring this literature, Arabs, would adopt the Greek medicine, and as such integrate it into their own (1).

Figure 1.

Dioskorides’s “De Materia Medica”, Arabian translation

2. GOLDEN AGE OF ARABIAN MEDICINE AND PHARMACY

One of the most significant periods in development of medicine in all was the golden age (1-4). Works created in this period stemmed not only from the Muslim authors, but also from all scientists in Arabic countries. The basis of Arabian medicine was by all means Greek, but it was enhanced by Islamic or Prophet’s medicine, and by a smaller margin with folk medicine. Driving factor in progress of medicine was Islam, with its belief that for every illness, God created a hidden cure. This led to the development of Pharmacognosia. Strong moral convictions present from the time that were result of Qur’an’s influence enticed the growth of professional ethics and the necessity of ritual washing gave birth to the principles of Hygiene. Medicine spread through the period between the fall of Roman Empire in 5th century until the beginning of Renaissance in 15th century. However, real progression of Arabian medicine and Pharmacology begins in 9th century and It corresponds to the golden age of Abbasid Caliphate in the east (749-1258). With the establishment of Abbasid Caliphate all important centers are transferred from Syria to Iraq. Baghdad becomes the capital and the center of culture and science. Other important city in that period were Damascus (former capital), Cairo, Granada and Cordoba in Spain. In these cities, there was a growing infrastructure of schools, libraries institutions and hospitals. Soon, many wise men from all over the caliphate flood to these cities in search of acquiring knowledge and orchestrating its further development.

2.1. SCHOOLS OF TRANSLATION

It is without a doubt that translating schools that were founded in big middle-age Arabian cities played an important role in collection of treasured biomedical sciences from previous civilizations. Doctors who would translate the works from Persian, Syrian, Indian, Hebrew and other languages to Arabic (1, 2). That was the first phase of development of Arabian science. One of the driving forces behind the interest in Hellenistic teachings was desire to give Islamic beliefs rational dimension along with the mystic, as to strengthen it. Hellenistic studies were accessible to Arabs because of various Christian sects, such as Nestorians and Jacobites, who were in several occasions banished from the Byzantine emperors who declared their teachings as heretic. Scientists from these sects would take their books and wisdom to the places they migrated into. When Arabs came to these lands, these scientists would openly present to them their concurrent findings and observations. Another way in which Arabs would acquire knowledge was through Alexandria. Alexandrian doctor Ahron, wrote “Compedium medicinae” which was translated to Arabic and possessed, beside the Greek medicine, a lot of medicines that were unbeknown to the likes of Dioscorides or Galen (1). In the city of Gondishapur, in the western Persia, long time before the founding of Baghdad, existed a large hospital and medical school. There, the works of Greeks would be translated into Aramaic and later on in Arabic language as well. Works of Greeks arrived there after the scientists were banished from Athenian academy. After rapid expansion of Abbasid dynasty, emerged a need for education of experts from various medical sciences. And so wise rulers of the dynasty summoned scientists from all over the world in Baghdad. Translation into Arabic reaches its peak during the reign of al-Ma’mun, who was the ruler that gave the biggest contribution to the development of the translation schools. At the end of the 8th century, Baghdad in the likeness of Gondishapur established translator school called “Bayti al-Hikma” or the “House of wisdom”, that will later on become Academy of sciences. The most important representative of this school was Hunayn ibn el-‘Ibadi (809-873) who translated the most the works of Dioscorides, Hippocrates, and Galen. He translated the aforementioned work “De Materia Medica” (Figure 1). Book was separated into five tomes which contained about 500 descriptions of drugs, of animal and plant origin, as well as their way of preparation, storage and administration. This was the first Pharmacopeia that would be supplemented by Arabs until it contained about 2000 substances. As such, the entire Arab controlled territory even since the 900th year disposed with the complete Greek science literature, excellently translated. In contrast these were way better books than what the Europeans had several centuries later as it was translated poorly from Arabic to Latin language (1).

2.2. CONTRIBUTION OF MEDICINE AND BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES TO DEVELOPMENT OF PHARMACY

Arabian medicine greatly contributed to the development of the pharmacy (1, 2). It is only logical that the doctors in their pursuit of treatment would discover and invent new medicine. They would write about the medicine in the booklets called “al-Mujarrabat”. Later on medicines were extracted from these booklets. Doctors wanted to use simple drugs for determining the exact effect of administered substance on the disease. However, some doctors have prescribed and combined drugs from their own formulated recipes. That gave birth to polypharmacy and combined recipes in practice. Early development of Pharmacy was in great deal inspired by usage of poisons and antidotes. This peaked interest of alchemists, who played the role of toxicologists. In the 9th century, alchemists were common sighting. Even though they failed to achieve some of their ideas, they were still invaluable for the development of pharmacy, since they used and perfected various chemical methods, techniques and laboratory equipment. Thanks to the fascination Arabs had towards chemistry, alchemy and drugs, we can say that pharmacy began its professional existence with Arabs. As such, Arabs became experts in creating many forms of medicine, ranging from tinctures, purgatives, sweetened and silver pills, distilled aromatic waters to solvents and etc (5-8) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Jabir b. Hayyan described distillation, by using alembic in 8th century

2.3. PHARMACY AS INDEPENDENT PROFESSION AND THE FIRST APOTHECARIES

Concerning history of pharmacy, the point in time when it became and independent profession is very important. Arabs are the first where we find the roots of pharmacy. They founded the first hospitals which included constant medical and hospital apothecary. Early distinction between the two begins as early as 7th century. Some of the main reasons for separation, were increased demand for the drugs from the growing population, unique intellectual curiosity and rapid translation of pharmaceutical papers. First apothecaries were opened by caliph al-Mensur in 754., in Baghdad. But since those apothecaries were in their beginnings, pharmacy as independent science is only accepted from the 9th century, when the pharmacists were completely aware of their profession’s principles. Thanks to the abundance of pharmacological information, pharmacy experts were welcomed. Profession and role of pharmacists first described al-Biruni, in his work “Saydanah fit-tibb”, and in a following way: “Professional which is specialized in gathering of all medicine, choosing only the best from simple and complex, in the preparation of good medicines, using the best and most precise methods and techniques that are recommended from healing experts.”. This description differs a little from the modern definition. He stressed that knowledge of how a medicine works is just as important as the knowledge of how to make it (9-18).

2.4. LAW REGULATION

Early growth of pharmacy was not regulated by law, which would regulate work of doctors and pharmacists. Pharmacists were supposed to be forbidden to make medical diagnoses without doctors, and doctors should have been forbidden to create and distribute medicine. Doctors feared that their medicine would fall into the hands of charlatans who did not undergo necessary education. Still, for more famous or complex medicine they would refer patients to apothecaries. During the reign of al-Mu’tasim, it is noted that to the educated and moral pharmacists were issued permits for private businesses. During the reign of both Arabs and Turks, there were two types of pharmacists, the pharmacists and attars, who were makers of drugs, but were limited in some aspects of their work. With Islam came the hygiene and with it the development of public health, and sanitary controls. During the reign of Abbasids, there was supervising service that was called ihtisab or hisba. On the top of ihtisab was muhtesib or president. This service would regulate the creation and distribution of medicines as well as differentiate between real and false drugs, spices and food. Medicine that was prescribed for an illness, had to have regular form, consistency and dosage. An author recommended weekly control of apothecaries, drugs and herbalists.

2.5. DEVELOPMENT OF PHARMACEUTICAL LITERATURE

Intensive development of literature begins in 9th century. Scientists that wrote the works about history of pharmacy, have separated the works into basic categories. And as such, historian Sami K. Hamameh classified the works into following categories: Forms and compendiums offered collection of formulas and recipes that were systematically arranged. In 9th century Sabur b. Sahl made the first form in Arabic language and called it the big “Book of medicines” (“al-Aqrabadhin al-Kabir”) and it contained information on medicine and how to prepare them. Books of toxicology came to be after poisons became more popular as the means of personal and political weapons. These special manuals would describe the symptoms of poisoning as well as various and wondrous antidotes. Works on dietetics and drug therapy were mostly about the importance of regular combination of medicines. The concept was that the ill needed different diet, environment and way of life as compared to healthy persons. Pharmaceutical books as comprising pieces of encyclopedias, were often divided in two tomes. Plethora of encyclopedias started by al-Razi, and continued by Ali ibn Abas with even more systematic and concise work and interest in ethics of medical care. Ibn Sina, also, contributed to the pharmacy with his “Canon medicinae” - “Al Quanun fit-tibb” where he devoted two tomes to pharmacy in which he described 760 medicines (1, 2).

2.6. GREAT NAMES IN ARABIAN MEDICINE AND PHARMACY

During all this development a plethora of important scientists played a key role. Among these there are abundance of doctors, botanists, alchemists and philosophers and encyclopedists that collected all the medical experiences of previous epochs and civilizations, which proved to be foundation for research and development of modern medicine. Here we are listing the most significant scientist of their time. These authors will be furthermore described (4, 14, 23, 25, 26).

Yuhann ibn Masawayh (777-857), was better known in the west as Mesue the Older. He was Nestorian doctor and translator. His most famous translations were of hygiene, fevers and dietetics. He wrote about combining the drugs and diets, claiming that the successful doctor should treat patients with nothing more than a diet. He researched strengthening the resistance of the organism so it can fight with the illness on its own. He was leading the first private medical school in Baghdad, and his student was Hunayn bin Ishaq.

Hunayn bin Ishaq (809-873) in the west known as Johanitus was most important path setter for the first translator school in Baghdad. He personally corrected the translation of the Pharmacopeia. He wrote about 100 original works, including the work on complex medicine for ocular illness.

Sabur bin Sahl (died 869) was the author of the first Arabian formula collection. Collection contained methods and techniques on drug composition, their pharmacological effects and dosage. Originality of the work stems from fact that he arranged the medicine by the forms and it was written to be a guide to the pharmacists.

Ali ibn Sahl at-Taberi (808- 861) wrote “Compendium of medicine” - “Firdaws ul-Hikma” which contains 25 chapters that speak of properties of the drugs.

Ali ibn ‘Abbas al-Majusi (925-994) is considered to be one of the biggest doctors of the 10th century. He wrote the medical encyclopedia “Kamil as-Sina’ah at Tibbiyyah” that was translated in latin as “Liber regius”.

Abu-l-Kasim al-Zahrawi (936-1013) was a practitioner, a doctor, a pharmacist and surgeon from the Islamic Spain. He is the author of a book whose translation of 28th chapter “Liber servitoris” used as a cherished guidebook of Medical chemistry in Europe.

Abu ar-Rayhan al-Biruni (975-1048) was of Persian origin. He wrote a lot of works of historiographic and encyclopedic type. He wrote a text on pharmacy and Materia medica called “as-Saydanah fit-tibb”. He gave the definition to the pharmacy and set its role in the society and science, claiming that knowledge of how the medicine works is more important of its plain preparation.

Ibn Jazlah (died 1100) wrote of poisons and antidotes, and in compendium “al-Minhayal-Bayan” he talks about simple and combined medicine and diets that are in use with the certain illnesses. He claimed to be bridging the holes left by his predecessors.

Ibn at-Tilmidh (1073-1165) founded in Baghdad one of the most famous medical schools. He wrote the books about medicine and therapeutics. He wrote “al-Aqrabadhin”, pharmaceutical text on preparation and prescription. Text later on became a basis for pharmaceutical practitioners.

Rabi Moses b. Maimon (1135-1024) was known as Maimonoides. He wrote a manual on poisons and manual on herbs with synonyms for drug names.

Ibn al-Baitar (1197-1248) was a known botanist, herbalist and author of most extensive and most popular works on “Materia medica”. He wrote the work “Choice of regular medicines”.

Kohen al-Attar was a Jewish doctor and pharmacist. In the year 1259 he wrote most significant pharmaceutical codex of his time called “Manual for apothecary laboratories” that is used even today by the drug experts in the East. In it are contained the duties of the pharmacist, recipes, guides for measurement during drug creation, skills of procurement and storage of drugs, as well as guides to distinction of false drugs and many others.

Further in this text we are going to talk about several encyclopedists. Abu Bakr al-Razi, Ibn Sina and Ibn al-Nafis and about their work with focus on their contribution to the pharmacy.

Abu Bakr al-Razi (865-925) was also known as “Arabian Galen” and was considered to be one of the most brilliant geniuses of middle age (Figure 3). He was and alchemist, chemist, doctor, physicist, philosopher and scholar. His contribution to medicine can only be compared to the likes of Ibn Sina. His famous works are “Kitab al-Hawi”, “Kitab al-Mensuri”, “Kitab al Muluki” and “Kitab al-Judari”. First mentioned work received its recognition as “Continens liber” when it was translated to Latin. It is his latest and greatest work that encompasses all the medical findings to that age. Kitab al-Mensuri is considered to have had four out of ten parts devoted to drugs and diets, and it contains the test results on animals and humans. He wrote the first book in Arabian world on house treatment that was dedicated to a broader population.

Figure 3.

Abu Bakr al-Razi (865.925.)

Abu Ali al Hosain Ibn Abdullah Ibn Hasan Ibn Ali Ibn Sina (980-1037) almost explicitly called Avicenna in the west, has been declared for greatest philosopher and doctor (Figure 4 and 5). He wrote over 300 works on medicine and its sister sciences. Medical experiences of Hippocrates and Galen he enhanced with his own clinical observations and experiments. He did not consider medicine to be one of the tougher sciences, since he mastered it by the age of 16. His main work about medicine is “Al-Quanun fit-tibb”, that was in 13th century, translated into Latin language, and all up until 17th century was considered main literature on all European medical universities. Encyclopedia was comprised of five tomes, of which second and fifth hold most significance regarding pharmacy as they contained all up to date discoveries. He wrote about 760 drugs, and he set principles for testing of efficacy of all the medicine. He created an approach in medicine, nowadays regarded to as holistic, which included physical, and psychic factors, diets and drugs.

Figure 4.

Ibn Sina (980.-1037.)

Figure 5.

First page of the Latin translation of Canon Medicinae: Liber Canoni

Alaudin ibn al-Nafis (1210-1288) was a great doctor of the thirteenth century. His most significant books are “Mu’giz al-Qanun” and “Sharh al-Qanun” His first work is an excerpt from the Sina’s Canon and its most important part regarding pharmacy is the second one, since it discussed the simple and complex drugs. He classifies them regarding their potency, and defines their effects in addition to the effects that result when mixing two substances.

2.7. INFLUENCE OF ARABIC ON EUROPEAN MEDICINE AND PHARMACY

Due to constant barbaric invasions Europe suffered before the beginning of middle age, that led to destruction of European ancient libraries and therefore its knowledge regarding medicine and pharmacy, Europeans forgot most of previously gathered knowledge. Since the Arabs collected all that knowledge, they enlightened Europeans with their recorded information on medicine and pharmacy. Up until 17th century Western European medicine stemmed from translated Arabic works. This so called Arabism began with Constantine of Africa, who led the school in Salerno. They translated a lot of Greek works but also original Arabian papers as well. Of the translated Sina’s Canon, a lot of courses were based in universities of Europe. The translation activities were most pronounced in Spain in 12th and 13th century. Sina’s Canon was translated by Cremon in Toledo, and as soon as Latin copy emerged, it had great glory. Soon many schools in Europe accepted the Canon as default book for medical studies and practice. Besides Canon other encyclopedias played an important role in development of pharmacy. Common practice among Arabs was creating combined medicine that would have multiple effects. Such was “teriac”, ancient antidote, made by Greeks and perfected by Galen. The West was fascinated by the marvelous effects of these drugs and has traded them at astronomical prices. Distinction of medicine and pharmacy that Arabs made was of great influence to the Europe, because after Sicily was relinquished, the knowledge spread to the rest of the Europe (1, 2, 4, 19).

3. FALL OF THE ARABIAN AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF TURKISH REIGN

After the fall of Arabian Caliphate, and seeing how it was succeeded by Turkish Empire at the end of 13th century, it is only logical that they would inherit the Arabian culture. And as such it is logical that Bosnia and Herzegovina would inherit a mix of both cultures and that medicine as well as pharmacy there would be heavily influenced by those preceding cultures. A thesis by Ibn Khaldun states that science in its entirety can only prosper on stable ground. And as such, Arabs promoted economy, trade and prosperity. But with the fall of the Arabian Caliphate and ensuing chaos, development of science came to a halt. Even after Turkish occupation of the territory, the science did not bloom as in the age of golden Arabian medicine. Reasons for this were many, from the vulnerability of the acquired territory to foreign invasion, to the fact that domestic population would often start rebellions. This was often followed by catastrophes such as droughts, famines, epidemics, and trade embargos. As such it is understandable that science was losing its creativity and vitality. After 16th century, Turks became more open to the western ideas, and with the influx of western people in the Turkish Empire, came the diseases that Turks did not know how to treat. They had to rely on western medicine to treat unknown diseases. All of the aforementioned vulnerabilities had led to attempts to pass various reforms, but the reforms were not seriously implemented until the beginning of the 19th century. The health system is being reformed to reflect that one in the west. The goal was to make the medicine more modern and precise. Despite the resistances that reforms encountered, in the Ottoman ruled countries, a stable ground was made for the development of the modern medicine. Same thing happened in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the practice of medicine and pharmacy started to reflect more eminent and prominent parts of the empire. The coming of Austro-Hungary in Bosnia and Herzegovina brought new reforms, which led to the opening of new modern pharmacies, education of first professional health staff as well as restricting the work of attars (3, 19, 24, 25).

4. PHARMACY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA

Since the Bosnia was for a long time a province of Ottoman Empire, the medical practice in it greatly reflected the state in more developed regions of the Empire, coupled with the knowledge that Jews, banished from the Spain brought (3). However, since the Empire faced many problems during that time, they neglected to teach broader range of people the teachings of medicine, and as such the Arabian medicine was not really accessible to the population, still it had undisputed influence on the medicine in Bosnia and Herzegovina at that time.

4.1. SOCIAL POLITICAL STANDINGS IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA DURING TURKISH REIGN

Ottomans rule the Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1463.-1878. During Ottoman reign, even with newly arrived Islam, majority of population did not go through drastic changes, and so, the country retained its Slavic personality (3). Even with the foreign rule, the domestic nobility was still in power, and as such Herzeg-Bosna held a special position in Ottoman Empire. Greatest reforms were performed by GaziHusrev-bey and SherifTopal Osman-pasha. Both founded first hospitals in Bosnia and Herzegovina (24). Organized healthcare starts with patient treating in Hadži-Sinan’s dervish house in 1768 (3, 19) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Hadži-Sinan’s dervish house from 1768.

4.2. WATER CULT

Maintaining hygiene as regulated by Islam, led to suppression of contagious disease, earning title of cleanest religion Islam promotes regular washing and bathing as well as maintenance of the environment. Every mosque had an external water tap, and with it the water supply. Public bathrooms were also there, allowing access to clean water. In these facilities, one could get a sauna, massage, and a full body wash (3, 24) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

GaziHusrev-bey’shamam

4.3. “NAHJETUR-RUTB” IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA

“Nahjetur-Rutb” was the law of sanitary safety that dates from 1234. It sets the hygienic standards, as well as regulations for medicine preparation and drug authentication. Its 18th chapter is devoted to attars, regulating their work as well (20-22).

4.4. FOLK MEDICINE, LJEKARUŠAS AND SUPERSTITION

Since the population was exposed to various illnesses, almost any branch of medicine had its own specialists. Their medicine was mostly based on superstition, and there was no regulated medical care (3, 9, 10, 19, 24). However, during 400 years of Ottoman reign, some professions proved to be more skilled. For example, Djerrahs, or wounders, were hired as the military doctors in ottoman army (3). Hapars, were barbers who made salves. Most important however were attars who made medicines from oils and herb. During that time existed books “Ljekaruše” that contained a lot of folk medicine, but also some of the more refined Sina’s medicine (Figure 8). They were copied by the folk and were the main source of folk medicine. Official literature, however was written in Turkish and Arabic and therefore was available only to the highest members of the society. Even though “Ljekaruša”s had useful knowledge, they were also filled with superstition. They were using amulets, fetishes, and scrolls, as well as parchments of Qur’an, which was contrary to Islamic principles (14, 15, 23, 25, 26).

Figure 8.

“Ljekaruša” from Monastery in Kraljeva Sutjeska

4.5. ATTARS

Attars were drug specialists that operated in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 16th century (19-22). They can be held responsible for development of the folk medicine. Their arrival coincides with arrival of sefard Jews. Their knowledge stemmed from the Arabian medicine. Attars were mostly situated in bigger cities. Attar practices are being soon picked up by the local Muslims, and they soon out numbered the Jews. They supplemented their attaric knowledge from the official literature, and they formed unions, while Jews continued working independently. Their stores held a variety of merchandise, from plants to oils and potions. Attars were so significant that even with the prohibition of their work, they still had more profit that official pharmacy, founded during that time.

4.6. FIRST EDUCATED HEALTH EXPERTS IN MEDICINE AND PHARMACY

Some people would travel far from Bosnia to receive an education from famous universities and then upon return would return to heal the population. Some were even from outside the Empire, but they treated only the nobles. They did however played an important role in the suppression of epidemics. Also, since leading cause of death, besides the epidemics were artificial abortions, doctors and pharmacists had to swear an oath not to perform these procedures (3, 9, 10, 11, 12, 19). Earliest records of a pharmacy date to the 16th century. In 1515. A pharmacy was founded and it is considered to be the beginning of attar’s work. First official library opened in 1852 but it was closed soon after. Same happened in 1854. After Austro-Hungarian occupation, new pharmacies are being opened (18-22). In 17th century there were three types of pharmacies. Attar shops, travelling doctor’s pharmacies, and a public pharmacy that was held by educated doctors and pharmacists from Europe and Istanbul (Figures 9 and 10). Most important libraries were Vilajet pharmacy and Gazi Husrev-bey hasthana (House of the ill) (19-22).

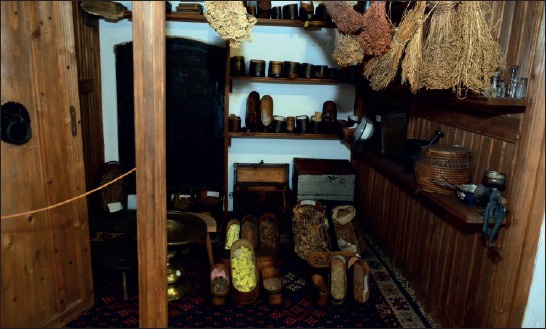

Figure 9.

Attar store in Sarajevo (owned byPapo family, 350 years ago)

Figure 10.

Jewish museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, preserved inventory of the attar’s store of the Papo family.

4.7. FUTURE RESEARCH AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Little is known of medicine in medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina prior to the Ottoman reign. First collections are originating from the Persia, Arabia and Turkey.

All the collections from the past are now located in three main locations: Gazi Husrev-bey library in Sarajevo, Institute for Public health FBIH, and author libraries. Since the Sina’s work was undisputed literature for centuries, same was in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Some of the standings of Sina are applicable even today and are called “Avicennic medicine”.

In Gazi Husrev-bey’s library there is a copy of Canon of medicinae. There are two more copies, one in the property of muderris Hadji-Ismail ef. Mašić and other, Latin edition in Arabic language from 1583.

5. CONCLUSION

Arabian civilization played an important role in maintaining continuity of scientific progress. In the critical moments for humanity, when world culture was being destroyed, they managed to preserve it. Arabs respected the value of science, even if it originated from other cultures, and they embraced it, rather than destroy it. After the fall of Arabia, Turks took over Arab territories, and even though they shared the same driving force behind science progress, the Islam, progress was slow during the Turkish reign because of all the hardships the Empire endured. However, Arabian culture left an inerasable impression on the world of science, saving it and launching it into the Golden age, away from the meek darkness where it once was.

REFERENCES

- 1.Masic I, et al. Srednjevjekovna arapska medicina. Sarajevo: Avicena; 2010. p. 276. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masic I, Skrbo A, Mulic I, Zunic L. Farmacija u islamu. Sarajevo: Avicena; 2010. p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masic I. Korijeni medicine i zdravstva u Bosni i Hercegovini. Sarajevo: Avicena; 2004. p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masic I. Arapska medicina. Sarajevo: Avicena; 1994. p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shefer-Mossensohn M. Ottoman medicine: healing and medical institutions 1500-1700. Albany: State University of New York Press; 2009. pp. 22–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamarneh S. The rise of professional pharmacy in islam. [Accessed: 08. 09. 2016];Med Hist. 1962 6(1):59–66. doi: 10.1017/s0025727300026855. Retreived: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1034673/?page=1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajar R. The air of history part III: The golden age in Arab islamic medicine an introduction. [Accessed: 08. 09. 2016];Heart views. 2013 14(1):43–46. doi: 10.4103/1995-705X.107125. Retreived: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3621228/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kremers and Urdangs’History of pharmacy: The Arabs and the European middle ages. 4th ed. Madison, Wisconsin: American institute of the history of pharmacy; pp. 23–17. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Djuricic A, Elazar S. Pregled istorije farmacije Bosne i Hercegovine. Sarajevo. 1958 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadzovic S, Masic I. Attari i njihov doprinos razvoju farmacije u BiH. Sarajevo: Avicena; 1999. p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadzovic S. Farmacija i veliki doprinos arapske islamske znanosti njenomrazvitku. Med Arh. 1997;51(1-2):47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tschanz D.W. A short history of islamic pharmacy. JISHIM. 2003. [Accessed: 08. 09. 2016]. Retreived: http://www.ishim.net/ishimj/3/03.pdf .

- 13.Masic I, Ridjanovic Z, Kujundzic E. Ibn Sina - Avicena - Zivot i djelo. Sarajevo: Avicena; 1995. p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masic I. Klasici Arapsko-islamske medicine. Sarajevo: Avicena; 1995. p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masic I. Thousand year anniversary of the historical book “Kitab al-Qanun fit-tibb”- the Canon of medicine, written by Abdulah ibn Sina. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2012;17(11):993–1000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parojcic D, Stupar D, Stupar M. Profesionalni odnos farmaceuta i lekara od 13. do 20. 2. Vol. 29. veka: Etički i stučni aspekt. Timočki medicinski glasnik; 2004. [Accessed: 08. 09. 2016]. Retreived: http://www.tmg.org.rs/v290211.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Hassan AY. Factors behind the decline of islamic science after the sixteenth century. [Accessed: 13.08.2016]. Retreived: http://www.history-science-technology.com/articles/articles%208.html .

- 18.Majeed A. How islam changed medicine. BMJ. 2005;331(7531):1486–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masic I. Zdravstvo u Bosni i Hercegovini tokom osmanskog perioda. Sarajevo: Avicena; 1995. p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gusic S. Uređenje attarske djelatnosti u osmanskom periodu u Bosni i Hercegovini. In: Hadzovic S, Masic I, editors. isaradnici. Attari i njihov doprinos razvoju farmacije u BiH. Sarajevo: Avicena; 1999. pp. 23–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devetak Z. Ljekaruse iz osmanskog perioda. In: Hadzovic S, Masic I, editors. i sar. Attari i njihov doprinos razvoju farmacije u BiH. Vol. 1999. Sarajevo: Avicena; pp. 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latal-Danon Lj. Jevrejska komponenta u attarskoj djelatnosti. In: Hadzovic S, Masic I, editors. i sar. Attari i njihov doprinos razvoju farmacije u BiH. Sarajevo: Avicena; 1999. pp. 35–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muminagic S, Masic I. The classics of Arabic medicine. Med Arh. 2010;64(4):254–6. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2010.64.253-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masic I. Zemaljska bolnica u Sarajevu. Sarajevo 1994: Avicena; 1994. p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masic I. Historija zdravstvene i socijalne kulture u BiH. Sarajevo: Avicena; 1993. p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masic I, Dilic M, Solakovic E, Rustempasic N, Ridjanovic Z. Why historians of medicine called ibn al-nafis second Avicenna? Med Arh. 2007;62(4):244–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masic I. On occasion of 800th anniversary of birth of ibn al_nafis - discoverer of cardiac and pulmonary circulation. Med Arh. 2010;64(5):309–13. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2010.64.309-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masic I. i sar. Doprinos islamske tradicije razvitku medicinske znanosti. Sarajevo: Avicena; 1999. p. 212. [Google Scholar]