Abstract

Paget's disease of bone (PDB) is marked by the focal activity of abnormal osteoclasts (OCLs)with excess bone resorption. We previously detected measles virus nucleocapsid protein (MVNP) transcripts in OCLs from patients with PDB. Also, MVNP stimulates pagetic OCL formation in vitro and in vivo. However, the mechanism by which MVNP induces excess OCLs/bone resorption activity in PDB is unclear. Microarray analysis identified MVNP induction of NFAM1 (NFAT activating protein with ITAM motif 1) expression. Therefore, we hypothesize that MVNP induction of NFAM1 enhances OCL differentiation and bone resorption in PDB.MVNP transduced normal human PBMC showed an increased NFAM1 mRNA expression without RANKL treatment. Further, bone marrow cells from patients with PDB demonstrated elevated levels of NFAM1 mRNA expression. Interestingly, shRNA suppression of NFAM1 inhibits MVNP induced OCL differentiation and bone resorption activity in mouse bone marrow cultures. Live cell widefield fluorescence microscopy analysis revealed that MVNP induced intracellular Ca2+ oscillations and levels were significantly reduced in NFAM1 suppressed preosteoclasts. Further, western blot analysis demonstrates that shRNA against NFAM1 inhibits MVNP stimulated PLCγ, calcineurin, and Syk activation in preosteoclast cells. Furthermore, NFAM1 expression controls NFATc1, a critical transcription factor expression and nuclear translocation in MVNP transuded preosteoclast cells. Thus, our results suggest that MVNP modulation of the NFAM1 signaling axis plays an essential role in pagetic OCL formation and bone resorption activity.

Keywords: Paget's disease of bone, Osteoclast, Bone resorption, MVNP, NFAM1

1. Introduction

Paget's disease of bone (PDB) is a chronic focal skeletal disease that affects 2 to 3% of the elderly population over the age of 55 years. The primary pathologic abnormality in PDB resides in bone-resorbing osteoclast (OCL) cells. The disease frequently involves deformity and enlargement of single or multiple bones such as skull, clavicles, long bones and vertebral bodies [1]. Patients with PDB have symptoms including bone pain, fractures, neurological complications due to spinal cord compression, deafness and dental abnormalities [2]. It has been reported that approximately 1% PDB patients have an incidence of osteosarcoma [3,4]. PDB has a variable geographic distribution, with an increased incidence in Caucasians of European origin, but it also occurs in African-Americans and Asian descent. PDB has an equal incidence in males and females at 40% rate in a familial manner. Genetic linkage analysis further indicated the disease is an autosomal dominant trait with genetic heterogeneity [5]. Recurrent mutations in p62 (SQSTM1) have been identified in 5 to 10% of total patients with PDB [6]. Also, declining prevalence of the disease strongly suggested environmental factors such as measles virus (MV) play an important role in the pathogenesis of PDB.

PDB has been described as a slow paramyxoviral infection process, suggesting a viral etiology for the disease. We previously identified the expression of transcripts encoding the MV nucleocapsid protein (MVNP) in freshly isolated bone marrow cells obtained from the pagetic patients [7].We further demonstrated that OCL precursors, the granulocyte macrophage colony-forming unit (CFU-GM), as well as mature OCLs from patients with PDB, expressed MVNP transcripts. We also detected expression of MVNP transcripts in peripheral blood-derived monocytes from these patients indicating that MV infection occurs in early OCL lineage cells [8]. Further, MVNP transduced OCLs demonstrated pagetic phenotype with hypersensitivity to both RANK ligand (RANKL) and vitamin D3 [9].

PDB is characterized by the increased number of abnormal osteoclasts containing abundant numbers of nuclei [10]. Enhanced levels of osteotropic cytokines such as IL-6, RANKL, M-CSF and endothelin-1 have been associated with PDB [11]. RANKL is a member of the TNF family that is produced by osteoblasts/osteocytes and stromal cells in the bone microenvironment. Receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) is expressed on committed OCL precursors. RANKL in combination with M-CSF induces differentiation of OCL precursors to form multinucleated mature OCLs [12]. Co-stimulatory factors, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)-bearing adapter proteins such as FcRγ and DAP12 are crucial for OCL development [13]. Syk tyrosine kinase functions as an adaptor molecule for ITAM signaling of FcRγ and DAP12 [14]. DAP12 is associated with immune receptors such as triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells–2 (TREM2),myeloid DAP12-associating lectin-1 (MDL-1) and signal regulatory protein β1 (SIRPβ1) [15]. We recently showed that MVNP modulates SIRPβ1 to enhance OCL differentiation and bone resorption activity associated with PDB [16]. NFAM1 (NFAT activating protein with ITAM motif 1) also known as CNAIP, is a ~ 30 kDa transmembrane glycoprotein that contains extracellular Ig domain and intracellular ITAM bearing region and involved in B cell development [17]. Also, PBMC in pulmonary embolism has been shown to express elevated levels of NFAM1 [18]. However, NFAM1 implications in the pathobiology of PDB on OCL differentiation is unknown. In this study, we identified MVNP up-regulation of NFAM1 expression, which plays a critical role in pagetic OCL differentiation/bone resorption activity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and antibodies

Cell culture and DNA transfection reagents were purchased from Invitrogen, Inc. (Carlsbad, CA). Recombinant murine RANKL and MCSF were obtained from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). Anti-NFATc1, anti-PLCɣ, anti-p-Syk, anti-Syk, anti-calcineurin and peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-NFAM1 antibody was purchased from Bioss Antibodies Inc (Woburn, MA). Secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorophores (AlexaFluor-488 and AlexaFluor-568) were obtained from Invitrogen, Inc., and DRAQ5 was from Axxora Platform, San Diego, CA (Biostatus Ltd.'s distributors). SuperSignal enhanced chemiluminescence reagent was obtained from Amersham Bioscience (Piscataway, NJ), and PVDF membranes were purchased from Millipore (Bedford, MA). Fura-2, AM and probenecid were purchased from Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA. Histochemical kit for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity, Ficoll-Paque, and DNAse I was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

2.2. MVNP retroviral expression

We have previously developed a retroviral plasmid construct pLXSN-MVNP and established PT67 amphotropic packaging cell line stably producing MVNP recombinant retrovirus at high titer (1 × 106 virus particles/mL). Similarly, a control retrovirus producer cell line was established by transfecting the cells with the empty vector (EV). Normal human peripheral blood/mouse bone marrow monocytes were transduced with EV or MVNP retroviral supernatants (20%) from the producer cell lines with polybrene (4 µg/mL) for 48 h. Total cells were collected after transduction for further studies [19].

2.3. Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated as described [20]. All human samples were obtained following the IRB-approved protocol at the Medical University of South Carolina. Briefly, whole blood was mixed with an equal amount of α-MEM, layered over Ficoll-Paque and centrifuged (1500 ×g, 30 min) at room temperature. The cells at the interface were collected and washed twice with serum free media and used for further studies.

2.4. Lentiviral expression of NFAM1 shRNA

GIPZ lentiviral NFAM1 shRNAmir plasmid construct (Open Biosystems, Rockford, IL) or EV were transfected into the 293FT amphotropic packaging cell line using lipofectamine and stable cell lines were established by selecting for resistance to neomycin (500 µg/mL). The cell lines were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL each of streptomycin and penicillin, 4 mM L-glutamine, and high glucose (4.5 g/L). Transduction of NFAM1 shRNAmir recombinant lentivirus (1 × 106 virus particles/mL) into PBMC, mouse bone marrow non-adherent and RAW264.7 cells was performed as described [21].

2.5. Quantitative real–time RT-PCR

NFAM1 mRNA expression levels were measured by real-time RT-PCR analysis. Total RNA was isolated from bone marrow cells from normal and patients with PDB as well as normal human PBMC cells were transduced with EV or MVNP plasmid. Residual genomic DNA contamination was eliminated using DNAse I at room temperature for 15 min followed by 10 min at 65 °C with the addition of 25 mM EDTA. The reverse transcription reaction was performed in a 25 µl reaction volume containing total RNA (2 µg). The quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed using IQ SYBR Green Supermix in an iCycler (iCycler iQ Single-color real-time PCR detection system; Bio—Rad, Hercules, CA). The primer sequences used to amplify human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (hGAPDH) mRNA were 5′-CCT ACC CCC AAT GTA TCC GTT GTG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGA GGA ATG GGA GTT GCT GTT GAA-3′ (anti-sense); hNFAM1 mRNA 5′-CAA CAC AGC TAT CTC CTT CAG C-3′ (sense) and 5′-TTC TCT GTG CCC AGT CCA G-3′ (anti-sense). The primer sequence for mGAPDH mRNA were 5′-ACC ACA GTC CAT GCC ATC AC-3′ (sense) and 5′- TCC ACC ACC CTG TTG CTG TA- 3′ (anti-sense); mNFAM1 mRNA 5’ATG CCA GGC TAC CAG TTG AC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGC CAT GGA TAT CCG TAT GA-3′ (anti-sense). Thermal cycling parameters used were 94 °C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of amplifications at 95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 2 min and 72 °C for 10 min as the final extension step. Relative levels of mRNA expression were normalized in all the samples analyzed with respect to the levels of GAPDH amplification.

2.6. Western blot analysis

RAW 264.7 preosteoclast cells were transduced with EV, EV+NFAM1 shRNA, MVNP andMVNP+NFAM1 shRNA and stimulated with or without RANKL (100 ng/mL) for 48 h. Total cell lysates were prepared in a lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. The protein content of the samples was measured using the BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein (100µg) samples were then subjected to SDS–PAGE using 4–15% Tris–HCl gradient gels and transferred onto a PVDF membrane, immunoblotted with anti-NFATc1, anti-PLCɣ, anti-p-Syk, anti-Syk, anti-calcineurin and anti-NFAM1 antibodies. The bands were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system.

2.7. Osteoclast culture and bone resorption activity assay

Mouse (C57BL/6) bone marrow derived non-adherent cells from femurs were seeded in 96-well plates at 2 × 106 cells/mL concentration in 0.2mL ofα-MEM containing 10% FBS. Cells were transduced with EV, EV + NFAM1 shRNA, MVNP and MVNP + NFAM1 shRNA and cultured in the presence of RANKL (100 ng/mL), M-CSF (10 ng/mL). The cells were re-fed every alternative day by removing half of the medium and replacing with fresh medium with a 2× concentration of cytokines. At the end of seven days culture period, the cells were fixed with glutaraldehyde (2%) in PBS and stained for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) activity using a histochemical kit. TRAP-positive multinucleated cells (MNC) containing three or more nuclei were considered as mature osteoclast (OCL) and scored under a microscope. Bone resorption assay was performed by culturing these cells for 10 days on dentine slices in the presence of M-CSF (10 ng/mL) and RANKL (100 ng/mL). The cells were removed from the dentine slices using 1 M NaOH and the discs were stained with 1% toluidine blue for 5 min. The digital images of the dentine were taken using an Olympus microscope and the resorption area was quantified using a computerized image analysis (Adobe Photoshop and Scion MicroImaging version beta 4.2). The percentage of the resorbed area was calculated relative to the total dentine area. The animal procedures employed were performed as per the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved the protocol.

2.8. Intracellular Ca2+ measurements by live cell widefield microscopy

RAW 264.7 cells transfected with EV, MVNP and MVNP + NFAM1 shRNA were cultured on 30 mm clear glass bottom plate and were serum-starved for 1 h. Cells were then loaded with Fura-2, AM in a Ringer's solution with 1 mM probenecid (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min at 37 °C. Intracellular Ca2+ levels were analyzed by live cell widefield microscopy (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany) and fluorescence intensity was continuously recorded for 20 min after addition of RANKL (50 ng/mL) at 340 and 380 nm emission as we previously described [22].

2.9. Confocal microscopy

RAW 264.7 preosteoclast cells (1 × 103/well) were cultured on glass cover slips and transfected with EV, EV + NFAM1 shRNA, MVNP and MVNP+NFAM1 shRNA. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. The cells were blocked for 1 h with PBS containing 2% donkey serum. Immunostaining was performed using anti-p-Syk and anti-NFATc1 antibodies with Alexa 568-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG respectively to visualize by confocal microscopy. Nuclear staining was performed with DRAQ5.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Results presented as mean±SD for three independent experiments and compared by Student t-test. Values were considered significantly different at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. MVNP induces NFAT activating protein with ITAM motif 1 (NFAM1) expression

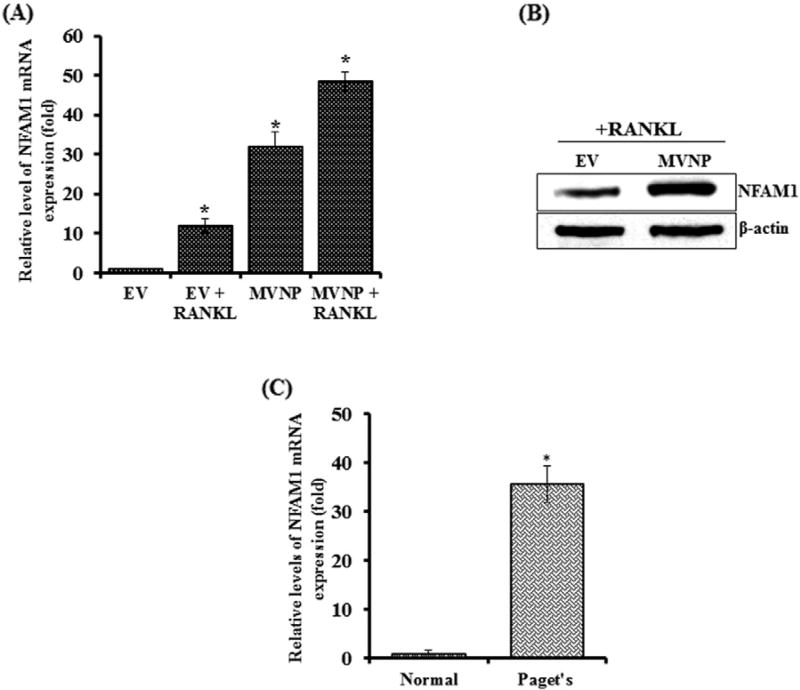

Previous studies have demonstrated that MVNP induces pagetic phenotype in OCLs (8). Recently we have determined MVNP regulated gene expression profiling during OCL differentiation by Agilent microarray analysis [16]. We thus identified high levels of NFAM1 expression in MVNP transduced preosteoclast cells compared with empty vector (EV) transduced cells. Further, normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells transduced with EV or MVNP expression construct were cultured with or without RANKL treatment for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 1A, NFAM1 mRNA expression markedly increased (32-fold) in MVNP-transduced preosteoclast cells without RANKL stimulation when compared to EV-transduced cells. RANKL treatment further enhanced (48.5-fold) NFAM1 expression in these cells. RANKL treatment to EV-transduced control cells demonstrated a 12-fold increase in NFAM1 mRNA expression. Also, western blot analysis of these cells demonstrates the increased levels of NFAM1 expression in MVNP transduced cells compared to EV treated with RANKL for 24 h (Fig. 1B). In addition, we tested whether the NFAM1 expression is elevated in bone marrow cells from patients with of PDB. Interestingly, real-time RT-PCR analysis of total RNA isolated from bone marrow cells obtained from all the PDB subjects (n = 8) analyzed revealed a significant (>20-fold) increase inNFAM1 expression compared to normal human bone marrow cells (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

MVNP enhances NFAM1mRNA expression. (A) Human peripheral blood monocytes (PBMC) were transduced with EV and MVNP expression plasmids. Cells were stimulated with M-CSF (10 ng/mL) and RANKL (100 ng/mL) for 48 h. Total RNA isolated was subjected to real-time RT-PCR analysis for NFAM1 mRNA expression. The relative level of mRNA expression was normalized by GAPDH amplification in these cells. (B) Human PBMC were transduced with EV or MVNP and stimulated with RANKL (100 ng/mL) for 48 h. Total cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis for NFAM1 expression using specific antibody. β-actin expression served as control. NFAM1 expression in PDB patients' bone marrow cells. (C) Total RNA isolated from normal and PDB patient's (n= 8) bone marrow cells were subjected to real-time RT-PCR analysis for NFAM1 expression. The relative level of mRNA expression was normalized by GAPDH amplification in these cells. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (P < 0.05).

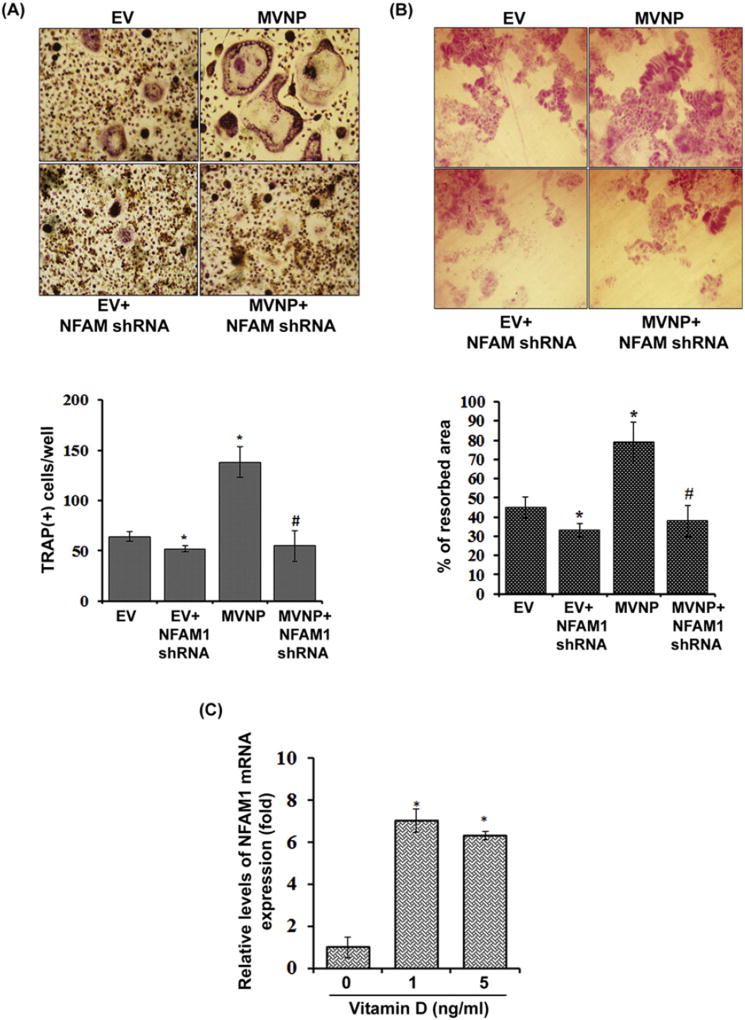

3.2. Inhibition ofNFAM1 suppresses MVNP stimulated osteoclast formation/bone resorption

We next determined the participation of NFAM1 in MVNP stimulated osteoclast (OCL) formation. Mouse bone marrow-derived non-adherent cells were transduced with EV or MVNP alone in the presence and absence of shRNA against NFAM1. The cells were then stimulated with RANKL (100 ng/mL) and M-CSF (10 ng/mL) for 5 days to induce OCL differentiation as described in methods. The differentiated cells were stained for TRAP activity and multinucleated OCL with more than three nuclei formed in these cultures was considered as mature OCL and scored under light-microscope. Consistently, MVNP significantly increased OCL formation compared to EV transduced cells. Further, shRNA inhibition of NFAM1 expression in the presence of MVNP significantly decreased OCL formation compared to MVNP alone transduced cells (Fig.2A). The mouse bone marrow-derived non-adherent cells transduced EV with NFAM1 shRNA showed a slight decrease in OCL formation compared to EV alone transduced culture. Similarly, MVNP stimulated OCL bone resorption activity was significantly decreased in the presence of shRNA against NFAM1 compared to MVNP transduced cells. Further, EV with NFAM1 shRNA transduced cultures shows a mild decrease in bone resorption activity compared with EV (Fig.2B). shRNA suppression of NFAM1 mRNA was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR (data not shown). Previously, it has been demonstrated that OCL precursors in PDB are hypersensitive to vitamin D3 [23]. Therefore, the preosteoclast cells were treated with different concentration of vitamin D3 (0–5 ng/mL) for 24 h. As shown in Fig.2C, total RNA isolated from these cells demonstrated a significant increase in the NFAM1 mRNA expression compared to untreated cells. Collectively, these results indicate that MVNP upregulation of NFAM1 plays an important role in enhancing OCL formation and bone resorption activity in PDB.

Fig. 2.

NFAM1 shRNA inhibits MVNP stimulated osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption activity. (A) Mouse bone marrow derived non-adherent cells (1.5 × 106/mL) were transduced with EV, EV + NFAM1 shRNA, MVNP and MVNP + NFAM1 shRNA and stimulated with RANKL (100 ng/mL) and M-CSF (10 ng/mL) for 7 days. TRAP-positive multinucleated OCLs formed in these cultures were scored. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (P < 0.05). (B) Mouse bone marrow derived non-adherent cells (1.5 × 106/mL) transduced with EV/MVNP with and without NFAM1 shRNA were cultured on dentine slices in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for 10 days. The percentage of the resorbed area was calculated relative to the total dentine area. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (P < 0.05). *Compared to EV transduced culture; #Compared to MVNP transduced culture. (C) Vitamin D3 stimulation of NFAM1 expression in preosteoclast cells. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with different concentration (0–5 ng/mL) of vitamin D3 [1,25 (OH)2D] for 24 h. Total RNA isolated from these cells were subjected to real-time RT-PCR analysis for NFAM1 expression. The relative level of mRNA expression was normalized by GAPDH amplification. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (P < 0.05). *Compared to unstimulated cells.

3.3. NFAM1 regulates RANKL induction of intracellular Ca2+ levels in MVNP transduced preosteoclast cells

RANKL stimulation of intracellular Ca2+ levels plays a major role in OCL differentiation [24,25]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the MVNP induction of NFAM1 expression may play a role in the regulation of the intracellular calcium levels in preosteoclast cells. A homogenous population of RAW 264.7 preosteoclast cells transduced with MVNP in the presence and absence of NFAM1 shRNA was loaded with Fura-2, AM (Fig.3A) and fluorescence (Ca2+ levels)were continuously recorded for 20 min upon RANKL stimulation by live cell widefield microscopy. As shown in Fig. 3B, RANKL stimulation increased the intracellular Ca2+ levels in the presence of MVNP compared to EV-transduced preosteoclast cells. In contrast, there was no change in intracellular Ca2+ levels and oscillations in cells transduced with MVNP and NFAM1 shRNA. Average calcium changes at a particular time point (15 min) in preosteoclast cells before and after RANKL treatment revealed that MVNP significantly elevated the intracellular calcium level, but, NFAM1 shRNA markedly diminished RANKL induced calcium levels in MVNP transduced preosteoclast cells (Fig.3C).

Fig. 3.

NFAM1mediates RANKL induced intracellular Ca2+ levels in MVNP transduced preosteoclast cells. RAW 264.7 cells transduced with EV,MVNP and MVNP+NFAM1 shRNA were cultured on 30 mm clear glass bottom plate and were serum-starved for 1 h. Calcium (Ca2+) levels were analyzed by live cell widefield microscopy and fluorescence was continuously recorded for 20 min after addition of RANKL (50 ng/mL) at 340 and 380 nm emission. (A) Immunofluorescence image of RAW 264.7 cells loaded with Fura-2 for 30 min (in green). (B) Representative time-lapse changes (20 min) in calcium level (Δ340/380 ratio) after RANKL treatment given at baseline (Time 0). (C) Changes in Ca2+ level from baseline in each group, after RANKL treatment (20 min). Each bar represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (*P < 0.05).

3.4. NFAM1 controls Syk activation, PLCγ and calcineurin expression in preosteoclast cells

It has been reported that NFAM1 induced ITAM phosphorylation, recruitment of ZAP-70/Syk, calcineurin and activation of NFATc1 [17,26]. We, therefore examined the role of NFAM1 in the regulation of these signaling molecules in MVNP transduced preosteoclast cells. Total cell lysate obtained from preosteoclast cells transduced with EV, MVNP with or without NFAM1 shRNA were subjected to western blot analysis for phospho-Syk expression. As shown in Fig. 4A, MVNP consistently elevated phospho-Syk expression in preosteoclast cells without RANKL stimulation. We further identified that shRNA suppression of NFAM1 markedly decreased MVNP induced p-Syk expression. In addition, EV with NFAM1 shRNA transduced cells showed a decrease in p-Syk expression in the presence and absence of RANKL stimulation when compared to EV. However, there was no change observed in the levels of total Syk expression in these cells. To further confirm, mouse bone marrow derived non-adherent cells were transduced with EV or MVNP and stimulated with RANKL for 60 min. Western blot analysis of total cell lysates revealed that RANKL significantly stimulates p-Syk expression in MVNP transduced cells compared to EV transduced cells (Fig. 4B). Confocal microscopy analysis further demonstrated that p-Syk is localized in cytoplasm and suppression of NFAM1 inhibits p-Syk expression in MVNP transduced preosteoclast cells (Fig. 4C). Since it has reported that Syk interacts with PLC-γ [27],we next examined the expression of PLCγ in these cells. Western blot analysis of total protein isolated from MVNP transduced preosteoclast cells showed increased levels of PLCγ expression without RANKL stimulation. Further, shRNA suppression of NFAM1 significantly decreased both MVNP and RANKL induced PLCγ expression (Fig. 4D). Similarly, RANKL increased the PLCγ expression in MVNP transduced mouse bone marrow derived non-adherent cells compared to EV transduced control cells (Fig. 4E). Also, western blot analysis of total cell lysate obtained from preosteoclast cells transduced with EV, MVNP and MVNP+NFAM1 shRNA revealed that MVNP alone elevated the calcineurin expression; however, inhibition of NFAM1 suppresses MVNP induced calcineurin expression (Fig. 4F). Collectively, these results identified that NFAM1 is involved in activation of Syk, stimulation of PLCγ and calcineurin expression during MVNP induction of OCL differentiation.

Fig. 4.

NFAM1modulation of signaling molecules in MVNP transduced preosteoclast cells. (A) RAW246.7 cells were transduced with EV, EV + NFAM1 shRNA, MVNP or MVNP + NFAM1 shRNA and stimulated with M-CSF (10 ng/mL) and RANKL (100 ng/mL) for 60 min. Total-cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis for p-Syk and Syk. The band intensity was quantified by NIH ImageJ. The relative band intensity was normalized to Syk expression and compared with EV. (B)Mouse bone marrow derived non-adherent cells transduced with EV or MVNP and stimulated with RANKL (100 ng/mL) for 60min. Total-cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis for p-Syk expression using specific antibody. Syk expression served as control. (C) Confocal microscopy analysis for p-Syk expression in RAW cells. Cells were transduced EV, EV + NFAM1 shRNA,MVNP, MVNP + NFAM1 shRNA and stimulated with M-CSF (10 ng/mL) and RANKL (100 ng/mL) for 60 min. Immunostaining for p-Syk as detected by Alexa 568–conjugated anti-rabbit antibody. Nuclear staining was performed with DRAQ5. EV, MVNP and MVNP + NFAM1 shRNA transduced preosteoclast cells stimulated with M-CSF (10 ng/mL) and RANKL (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. Total-cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis for (D) PLCγ and (F) calcineurin expression. The relative band intensity was normalized to β-actin expression and compared with EV. (E) Mouse bone marrow derived non-adherent cells transduced with EV or MVNP and stimulated with RANKL (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. Total-cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis for using an antibody against PLCγ. β-actin expression served as control.

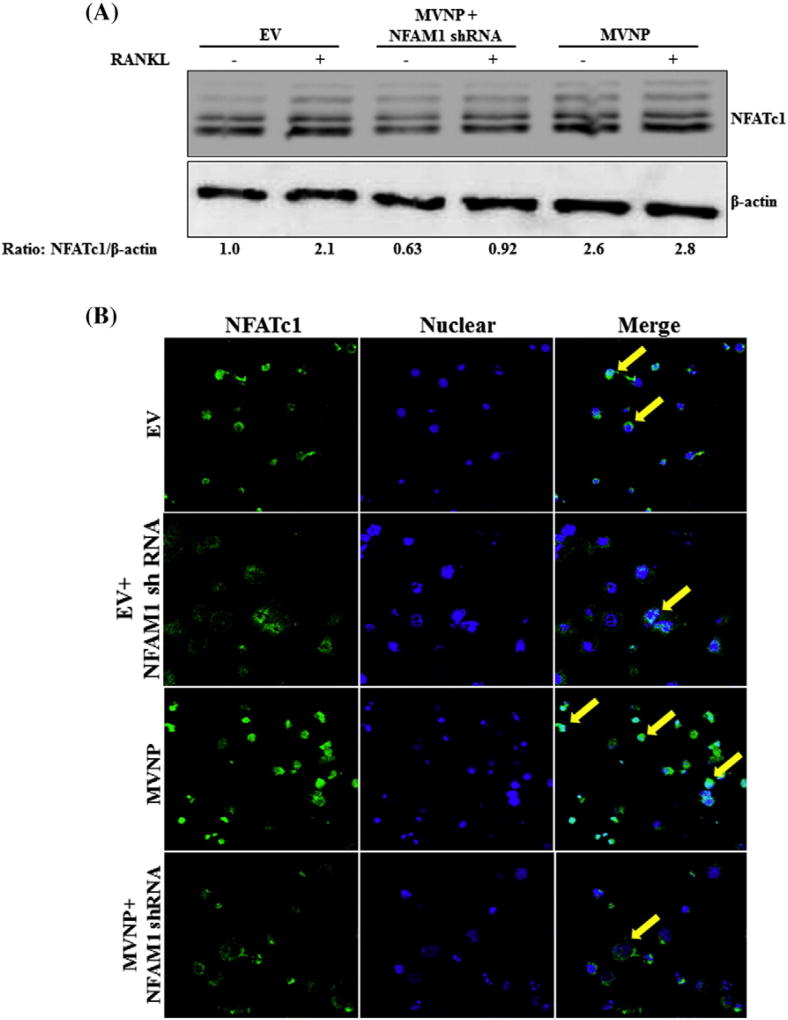

3.5. NFAM1 induced NFATc1 expression and nuclear translocation during OCL differentiation

NFAM1 has been shown to activate the calcineurin/NFAT-signaling pathway [26]. Therefore, we examined the NFATc1 expression, a critical transcription factor for OCL differentiation/function in the presence and absence of NFAM1 in preosteoclast cells. EV or MVNP in the presence and absence of NFAM1 shRNA transduced RAW 264.7 cells were stimulated with RANKL. Total cell lysate collected from these cells were subjected to western blot analysis for NFATc1 expression. As shown in Fig. 5A, we identified shRNA suppression of NFAM1 expression in preosteoclast cells demonstrated a significant decrease in MVNP stimulated NFATc1 expression. We next examined the potential of NFAM1 to induce nuclear translocation of NFATc1 in preosteoclast cells. RAW 264.7 cells transduced with MVNP in the presence and absence of NFAM1 shRNA were stimulated with RANKL for 24 h and immunestained with the anti-NFATc1 antibody. Confocal microscopy analysis revealed that MVNP increased the nuclear localization of NFATc1 compared to control in RANKL stimulated preosteoclast cells. Further, shRNA inhibition of NFAM1 suppressed the RANKL stimulated nuclear translocation of NFATc1 in MVNP and EV transduced cells (Fig.5B). These results suggest that NFAM1 signaling plays an important role in activation of NFATc1 and induces osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption activity in PDB.

Fig. 5.

NFAM1 shRNA suppresses MVNP induced NFATc1 expression and nuclear localization. (A) RAW 246.7 cells were transduced with EV, MVNP and MVNP + NFAM1 shRNA and stimulated with M-CSF (10 ng/mL), RANKL (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. Total-cell lysates were subjected to western blot analysis for NFATc1 expression. β-actin expression served as control. (B) Confocal microscopy analysis of NFATc1 localization in RAW 264.7 cells transduced with EV or MVNP in the presence and absence of NFAM1 shRNA and stimulated with RANKL (100 ng/mL). Immunostaining for NFATc1 shown at 24 h as detected by Alexa 488–conjugated anti-mouse antibody. Nuclear staining was performed with DRAQ5.

4. Discussion

MVNP has been implicated in the pathogenesis of PDB [28]. Earlier, we showed that patients with PDB contain elevated levels of FGF-2 and chemokine CXCL5, which modulate osteoclastogenesis through induction of RANKL expression in osteoblast cells [19,29]. Since the pagetic OCL contain MVNP and shown directly induces osteoclastogenesis, it is important to unravel the underlying molecular mechanisms to determine the pathogenesis of PDB. This study identified that bone marrow cells from patients with PDB contain elevated levels of NFAM1 expression compared to normal subjects. In addition, MVNP expression up-regulates NFAM1 levels in normal preosteoclast cells. This study also demonstrates that NFAM1 inhibition markedly suppressed MVNP induced OCL differentiation and bone resorption activity. Thus, NFAM1 expression plays an important role in pagetic OCL development. However, our findings that RANKL modestly increased NFAM1 expression suggest that it may also have a role in normal bone homeostasis. Furthermore, NFAM1 induction could directly or indirectly influence other molecules such as c-Src or proton pump during OCL differentiation. Evidently, several costimulatory factors associated with immune signaling have shown to play an essential role in OCL differentiation [30]. NFAM1 containing ITAM bearing region, it is more likely the MVNP expression could modulate immune signaling during OCL differentiation. Molecules associated with ITAM signaling play a role in OCL formation and involved in localized inflammatory bone loss [30]. Siglec-15, which regulates immune system has been shown to modulate RANKL signaling in association with DAP12 essential for OCL development/ activity [31]. Therefore, MVNP expression levels in PDB contributes to upregulation of NFAM1 which could be an important mechanism to stimulate pagetic OCL differentiation and bone resorption activity compared to normal. It has been reported thatMVNP stimulates signaling molecules essential for OCL formation such as RANK, TRAF and NFATc1 [32]. TBK1 has also been shown to mediate the effects of MVNP on IL-6 gene expression contributing to the pagetic OCL formation [33]. Further, our data that MVNP increased PLCɣ, p-Syk expression and induced calcium influx suggests that signaling pathways associated with these molecules may be involved in MVNP and RANKL induction of NFAM1 expression. Thus, it is possible that upregulation of NFAM1gene expression could play an important role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Genetic linkage analysis indicated that mutations in the p62 gene associated with PDB do not completely account for the pathogenesis of the disease [34]. However, MVNP upregulation of several cytokines, signaling molecules, and transcription factors enhance OCL differentiation. MVNP interactions with genetic factors may increase the severity of the disease through modulation of NFAM1 expression in PDB. Osteoclast precursors from patients with PDB are hypersensitive to both RANKL and vitamin D [35]. Our data that vitamin D3 stimulates NFAM1 expression suggests that MVNP induction ofNFAM1 may have a functional role in hypersensitivity of OCL precursors in PDB.

MVNP induces NFAM1, which activates calcineurin-NFATc1 pathway during OCL differentiation. Suppression of NFAM1 inhibits MVNP induced p-Syk, calcineurin and NFATc1 expression as well as intracellular calcium level. These results are indicating that the MVNP induction of NFAM1 can elevate the RANKL stimulated calcium signaling in preosteoclast cells and thus control enhanced OCL formation in PDB. Also, it has been reported that calcium signaling of ITAM-harboring adaptors is essential for OCL formation [36]. Further, inhibition of PLA2 expressed highly in pagetic OCLs reduces osteoclastogenesis in vitro [37]. PLCɣ2 shown to influence Src activation through integrin complex to modulate OCL activity [38]. Furthermore, costimulatory signals mediated by ITAM and PLCγ induce Ca2+ oscillations and activation of NFATc1 [39]. This study demonstrated that NFAM1 signaling enhances OCL development and bone resorption activity by increasing PLCγ, calcium influx and activating the calcineurin-NFATc1 pathway in MVNP positive preosteoclast cells. These results suggest that MVNP modulation of the NFAM1 signaling axis plays a critical role in pagetic OCL formation and bone resorption activity. It has been reported that RBP-J transcription factor suppresses key osteoclastogenic signaling factors NFATc1, ITAM-mediated expression and calcium-CaMKK pathway [40]. Therefore, MVNP/NFAM1 may inhibit negative regulators to enhance OCL differentiation and bone resorption in PDB. Furthermore, elevated levels of NFAM1 expression associated with pulmonary embolism may implicate an increased OCL activity and fracture risk [18,41]. Thus, our results suggest that MVNP modulation of the NFAM1 signaling axis may play a critical role in enhanced pagetic OCL differentiation and bone resorption activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH Grant award 1R56AG052511-01 to SVR; K08 DK106465 to TS and by the C06 RR015455 from the Extramural Research Facilities Program of the National Center for Research Resources. We thank Dr. Devadoss J. Samuvel for assistance with confocal microscopy.

References

- 1.Albagha OM. Genetics of Paget's disease of bone. Bonekey Rep. 2015;4:756. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2015.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vallet M, Ralston SH. Biology and treatment of Paget's disease of bone. J. Cell. Biochem. 2016;117(2):289–299. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamdy RC. Clinical features and pharmacologic treatment of Paget's disease. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 1995;24(2):421–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoki M, Tanahashi S, Mizuta K, Kato H. Treatment for progressive hearing loss due to Paget's disease of bone - a case report and literature review. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2015;11(3):267–270. doi: 10.5152/iao.2015.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leach RJ, Singer FR, Roodman GD. The genetics of Paget's disease of the bone. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86(1):24–28. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daroszewska A, van't Hof RJ, Rojas JA, Layfield R, Landao-Basonga E, Rose L, Rose K, Ralston SH. A point mutation in the ubiquitin-associated domain of SQSMT1 is sufficient to cause a Paget's disease-like disorder in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20(14):2734–2744. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedrichs WE, Reddy SV, Bruder JM, Cundy T, Cornish J, Singer FR, Roodman GD. Sequence analysis of measles virus nucleocapsid transcripts in patients with Paget's disease. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2002;17(1):145–151. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy SV, Singer FR, Roodman GD. Bone marrow mononuclear cells from patients with Paget's disease contain measles virus nucleocapsid messenger ribonucleic acid that has mutations in a specific region of the sequence. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995;80(7):2108–2111. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.7.7608263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurihara N, Reddy SV, Menaa C, Anderson D, Roodman GD. Osteoclasts expressing the measles virus nucleocapsid gene display a pagetic phenotype. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105(5):607–614. doi: 10.1172/JCI8489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy SV, Menaa C, Singer FR, Demulder A, Roodman GD. Cell biology of Paget's disease. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1999;14(Suppl. 2):3–8. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650140203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarquini R, Perfetto F, Tarquini B. Endothelin-1 and Paget's bone disease: is there a link? Calcif. Tissue Int. 1998;63(2):118–120. doi: 10.1007/s002239900500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asagiri M, Takayanagi H. The molecular understanding of osteoclast differentiation. Bone. 2007;40(2):251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou W, Zhu T, Craft CS, Broekelmann TJ, Mecham RP, Teitelbaum SL. Cytoskeletal dysfunction dominates in DAP12-deficient osteoclasts. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 17):2955–2963. doi: 10.1242/jcs.069872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mocsai A, Humphrey MB, Van Ziffle JA, Hu Y, Burghardt A, Spusta SC, Majumdar S, Lanier LL, Lowell CA, Nakamura MC. The immunomodulatory adapter proteins DAP12 and fc receptor gamma-chain (FcRgamma) regulate development of functional osteoclasts through the Syk tyrosine kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101(16):6158–6163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401602101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng Q, Malhotra S, Torchia JA, Kerr WG, Coggeshall KM, Humphrey MB. TREM2- and DAP12-dependent activation of PI3K requires DAP10 and is inhibited by SHIP1. Sci. Signal. 2010;3(122):ra38. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sundaram K, Sambandam Y, Shanmugarajan S, Rao DS, Reddy SV. Measles virus nucleocapsid protein modulates the Signal Regulatory Protein-β1 (SIRPβ1) to enhance osteoclast differentiation in Paget's disease of bone. Bone reports. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2016.06.002. (e-pub) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bonr.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Ohtsuka M, Arase H, Takeuchi A, Yamasaki S, Shiina R, Suenaga T, Sakurai D, Yokosuka T, Arase N, Iwashima M, Kitamura T, Moriya H, Saito T. NFAM1, an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif-bearing molecule that regulates B cell development and signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101(21):8126–8131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401119101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lv W, Duan Q, Wang L, Gong Z, Yang F, Song Y. Expression of B-cell-associated genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015;11(3):2299–2305. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sundaram K, Senn J, Yuvaraj S, Rao DS, Reddy SV. FGF-2 stimulation of RANK ligand expression in Paget's disease of bone. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009;23(9):1445–1454. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Susa M, Luong-Nguyen NH, Cappellen D, Zamurovic N, Gamse R. Human primary osteoclasts: in vitro generation and applications as pharmacological and clinical assay. J. Transl. Med. 2004;2(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shanmugarajan S, Haycraft CJ, Reddy SV, Ries WL. NIP45 negatively regulates RANK ligand induced osteoclast differentiation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012;113(4):1274–1281. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambandam Y, Blanchard JJ, Daughtridge G, Kolb RJ, Shanmugarajan S, Pandruvada SN, Bateman TA, Reddy SV. Microarray profile of gene expression during osteoclast differentiation in modelled microgravity. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010;111(5):1179–1187. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teramachi J, Zhou H, Subler MA, Kitagawa Y, Galson DL, Dempster DW, Windle JJ, Kurihara N, Roodman GD. Increased IL-6 expression in osteoclasts is necessary but not sufficient for the development of Paget's disease of bone. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014;29(6):1456–1465. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takayanagi H, Kim S, Koga T, Nishina H, Isshiki M, Yoshida H, Saiura A, Isobe M, Yokochi T, Inoue J, Wagner EF, Mak TW, Kodama T, Taniguchi T. Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Dev. Cell. 2002;3(6):889–901. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soysa NS, Alles N, Aoki K, Ohya K. Osteoclast formation and differentiation: An overview. J. Med. Dent. Sci. 2012;59(3):65–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang J, Hu G, Wang SW, Li Y, Martin R, Li K, Yao Z. Calcineurin/nuclear factors of activated T cells (NFAT)-activating and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)-containing protein (CNAIP), a novel ITAM-containing protein that activates the calcineurin/NFAT-signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(19):16797–16801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Law CL, Chandran KA, Sidorenko SP, Clark EA. Phospholipase C-gamma1 interacts with conserved phosphotyrosyl residues in the linker region of Syk and is a substrate for Syk. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16(4):1305–1315. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teramachi J, Nagata Y, Mohammad K, Inagaki Y, Ohata Y, Guise T, Michou L, Brown JP, Windle JJ, Kurihara N, Roodman GD. Measles virus nucleocapsid protein increases osteoblast differentiation in Paget's disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126(3):1012–1022. doi: 10.1172/JCI82012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sundaram K, Rao DS, Ries WL, Reddy SV. CXCL5 stimulation of RANK ligand expression in Paget's disease of bone. Lab. Investig. 2013;93(4):472–479. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crotti TN, Dharmapatni AA, Alias E, Haynes DR. Osteoimmunology: Major and costimulatory pathway expression associated with chronic inflammatory induced bone loss. J. Immunol. Res. 2015;2015:281287. doi: 10.1155/2015/281287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kameda Y, Takahata M, Komatsu M, Mikuni S, Hatakeyama S, Shimizu T, Angata T, Kinjo M, Minami A, Iwasaki N. Siglec-15 regulates osteoclast differentiation by modulating RANKL-induced phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and Erk pathways in association with signaling adaptor DAP12. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013;28(12):2463–2475. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shanmugarajan S, Youssef RF, Pati P, Ries WL, Rao DS, Reddy SV. Osteoclast inhibitory peptide-1 (OIP-1) inhibits measles virus nucleocapsid protein stimulated osteoclast formation/activity. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008;104(4):1500–1508. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun Q, Sammut B, Wang FM, Kurihara N, Windle JJ, Roodman GD, Galson DL. TBK1 mediates critical effects of measles virus nucleocapsid protein (MVNP) on pagetic osteoclast formation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014;29(1):90–102. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merchant A, Smielewska M, Patel N, Akunowicz JD, Saria EA, Delaney JD, Leach RJ, Seton M, Hansen MF. Somatic mutations in SQSTM1 detected in affected tissues from patients with sporadic Paget's disease of bone. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2009;24(3):484–494. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.081105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menaa C, Barsony J, Reddy SV, Cornish J, Cundy T, Roodman GD. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 hypersensitivity of osteoclast precursors from patients with Paget's disease. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2000;15(2):228–236. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takayanagi H. Inflammatory bone destruction and osteoimmunology. J. Periodontal Res. 2005;40(4):287–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2005.00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allard-Chamard H, Haroun S, de Brum-Fernandes AJ. Secreted phospholipase A2 type II is present in Paget's disease of bone and modulates osteoclastogenesis, apoptosis and bone resorption of human osteoclasts independently of its catalytic activity in vitro. Prostaglandins. Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids. 2014;90(2–3):39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Epple H, Cremasco V, Zhang K, Mao D, Longmore GD, Faccio R. Phospholipase Cgamma2 modulates integrin signaling in the osteoclast by affecting the localization and activation of Src kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28(11):3610–3622. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00259-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koga T, Inui M, Inoue K, Kim S, Suematsu A, Kobayashi E, Iwata T, Ohnishi H, Matozaki T, Kodama T, Taniguchi T, Takayanagi H, Takai T. Costimulatory signals mediated by the ITAM motif cooperate with RANKL for bone homeostasis. Nature. 2004;428(6984):758–763. doi: 10.1038/nature02444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li S, Miller CH, Giannopoulou E, Hu X, Ivashkiv LB, Zhao B. RBP-J imposes a requirement for ITAM-mediated costimulation of osteoclastogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124(11):5057–5073. doi: 10.1172/JCI71882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barrett JA, Baron JA, Beach ML. Mortality and pulmonary embolism after fracture in the elderly. Osteoporos. Int. 2003;14(11):889–894. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1494-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]