Abstract

The UK incidence of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is 9 per 100,000 population, and biliary tract cancer occurs at a rate of 1–2 per 100,000. The incidence of both cancers is increasing annually and these tumours continue to be diagnosed late and at an advanced stage, limiting options for curative treatment. Population-based screening programmes do not exist for these cancers, and diagnosis currently is dependent on symptom recognition, but often symptoms are not present until the disease is advanced. Recently, a number of promising blood and urine biomarkers have been described for pancreaticobiliary malignancy and are summarised in this review. Novel endoscopic techniques such as single-operator cholangioscopy and confocal endomicroscopy have been used in some centres to enhance standard endoscopic diagnostic techniques and are also evaluated in this review.

Keywords: Pancreaticobiliary malignancy, Endoscopic retrograde, cholangiopancreatography, CA 19-9, pancreatic, biliary

Introduction

In the UK, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the 10 th commonest cancer and has an incidence of 9 per 100,000 population 1, and biliary tract cancer (BTC) (including intra- and extra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder cancer) has an incidence of 1–2 cases per 100,000 population 2. Long-term survival is poor; 5-year survival is less than 4% for both tumours 3, 4. Often these tumours are diagnosed late, when patients have advanced disease and curative surgical resection is no longer possible.

Globally the highest incidence of PDAC is seen in Northern Europe and North America 5, where the rates are 3 to 4 times higher than in tropical countries 6. Overall incidence is increasing 5, and as most tumours are sporadic, this rising incidence is attributed to differences in lifestyles and exposure to environmental risk factors 7, such as smoking 8– 15, diabetes mellitus, chronic pancreatitis 1, 15, 16 and obesity 17.

In BTC, the variations in incidence seen globally are even more pronounced; and the highest incidence is in northeastern Thailand (96 per 100,000 men) 18, which has a population with high levels of chronic typhoid and infestation of liver fluke ( Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverinni) 18. Other BTC risk factors seen in all populations include older age 18, primary sclerosing cholangitis 19, intraductal stones and rare biliary cystic diseases 20. Inflammatory bowel disease, chronic viral hepatitis, cirrhosis, smoking, diabetes, obesity and excess alcohol consumption may also increase the risk of BTC 20– 22.

Despite improved diagnostic techniques, detecting pancreaticobiliary malignancy remains a significant clinical challenge. A common presentation of these tumours is a biliary stricture with or without a mass lesion. The differential of an indeterminate biliary stricture is broad, and often the associated symptoms and radiological findings overlap between benign and malignant conditions, often making differentiation—particularly between cancer, primary sclerosing cholangitis and IgG4-related disease—impossible without further investigations, typically by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) 23– 25. However, biliary brush cytology is also an imperfect test, although specificity is high (96–100%), sensitivity for malignancy remains low (9–57%) and in early disease when tumours are small, sensitivities are even lower 26, 27. Therefore, patients frequently require multiple procedures to obtain a final diagnosis 28– 30.

So there has been growing interest in the development of simple tests to streamline the diagnosis to pancreaticobiliary malignancy and guide appropriate and timely therapy for patients. Identifying better diagnostic tools for PDAC and BTC would also make screening and surveillance possible, particularly in high-risk populations 4, 8, 31. This would enable the detection of tumours at an earlier stage when curative resection is possible, leading to substantial improvements in survival 32. This review provides an overview of the latest innovations in diagnostic biomarkers and endoscopic techniques for pancreaticobiliary malignancy.

Methods

We performed a systematic review of the literature by using PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library. The search was limited to studies published in the English language between January 2013 and March 2017. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were decided by a consensus of the authors and included “pancreatic cancer” or “cholangiocarcinoma” and “biomarker”. The search was restricted to title, abstract and keywords. Articles that described outcomes for fewer than five patients were excluded. Case reports, abstracts and reviews were excluded. All references were screened for potentially relevant studies not identified in the initial literature search.

The following variables were extracted for each report when available: number of malignant and benign cases, sensitivity, specificity and area under the curve (AUC). One hundred ten articles were included in the final review.

Biomarkers

1. Serum biomarkers and blood tests

Carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 is the most widely used tumour marker in pancreaticobiliary malignancy. Overall sensitivity (78–89%) and specificity (67–87%) are low, and in around 7% of the population who lack the Lewis (a) antigen, CA19-9 will remain negative 33. In small tumours, sensitivity decreases further. The marker can also be elevated in a number of other malignant diseases (for example, gastric adenocarcinoma) and benign diseases, particularly those causing jaundice (for example, primary biliary cirrhosis, cholestasis and cholangitis), and in smokers 34. In addition, variation has been reported among commercially available assays, which may impact on interpretation 35. Therefore, to improve the sensitivity of the marker in current clinical practice, it is always interpreted in the context of cross-sectional imaging findings 33.

Other commercially available tumour markers that have a role in diagnosing pancreaticobiliary cancer include carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA125. CEA is a glycosyl phosphatidyl inositol cell surface-anchored glycoprotein that is involved in cell adhesion. When elevated, it is highly suggestive of colorectal cancer, but it is also increased in about a third of patients with BTC 36– 38. CA125 is a protein encoded by the MUC16 gene and is a large membrane-associated glycoprotein with a single transmembrane domain. When elevated, it is suggestive of ovarian cancer, but it is also increased in about 40–50% of patients with pancreaticobiliary malignancy, particularly when there is peritoneal involvement 38.

Owing to the limitations of existing biomarkers, over the last few years several studies have evaluated various combinations of biomarkers to supplement or ultimately replace existing biomarkers. Biomarker panels using combinations of markers, often including CA19-9, have been particularly successful in detecting small tumours and early disease. Validation studies have also shown that these markers can differentiate PDAC from relevant benign conditions and in some cases detect tumours up to 1 year prior to diagnosis with a specificity of 95% and a sensitivity of 68% 7 ( Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1. Serum protein biomarkers for biliary tract cancer, 2013–2017.

| Author (year) | Biomarker/

Combination (serum) |

Biliary tract

cancer, number |

Benign lesion/

cholangitis, number |

Healthy

volunteers, number |

Sensitivity | Specificity | Area

under the curve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single biomarkers | |||||||

| Han et al. (2013) 84 | HDGF | 83 | - | 51 | 66% | 88% | 0.81 |

| Ruzzenente et al. (2014) 85 | MUC5AC | 49 | 23 | 16 | - | - | 0.91 |

| Voigtlander et al. (2014) 86 | Angpt-2 | 56 | 111 | - | 74% | 94% | 0.85 |

| Lumachi et al. (2014) 87 | CA 19-9 | 24 | 25 | - | 74% | 82% | - |

| Wang et al. (2014) 88 | CA 19-9 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 72% | 96% | - |

| Lumachi et al. (2014) 87 | CEA | 24 | 25 | - | 52% | 55% | - |

| Wang et al. (2014) 88 | CEA | 78 | 78 | 78 | 11% | 97% | - |

| Wang et al. (2014) 88 | CA 125 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 45% | 96% | - |

| Lumachi et al. (2014) 87 | CYFRA 21-1 | 24 | 25 | - | 76% | 79% | - |

| Liu et al. (2015) 89 | VEGF-C | 31 | 10 | 10 | 71% | 80% | 0.79 |

| Liu et al. (2015) 89 | VEGF-D | 31 | 10 | 10 | 74% | 85% | 0.84 |

| Huang et al. (2015) 90 | CYFRA 21-1 | 134 | 52 | - | 75% | 85% | - |

| Lumachi et al. (2014) 87 | MMP7 | 24 | 25 | - | 78% | 77% | - |

| Nigam et al. (2014) 91 | Survivin | 39 (gallbladder

cancer) |

30 | 25 | 81% | 80% | - |

| Rucksaken et al. (2014) 92 | HSP70 | 31

|

12 | 23 | 94%

|

74%

|

0.92

|

| Rucksaken et al. (2014) 92 | ENO1 | 31 | - | 23 | 81% | 78% | 0.86 |

| Rucksaken et al. (2014) 92 | RNH1 | 31 | - | 23 | 94% | 67% | 0.84 |

| Wang et al. (2014) 88 | CA242 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 64% | 99% | - |

| Ince et al. (2014) 93 | VEGFR3 | 96 | 129 | - | 48% | 82% | 0.62 |

| Ince et al. (2014) 93 | TAC | 96 | 129 | - | 61% | 60% | 0.60 |

| Rucksaken et al. (2017) 94 | ORM2 | 70 | 46 | 20 | 92% | 74% | - |

| Rose et al. (2016) 95 | CEACAM6 | 41 | 42 | - | 87.5% | 69% | 0.74 |

| Jiao et al. (2014) 96 | Nucleosides | 202 (gallbladder

cancer) |

203 | 205 | 91% | 96% | - |

| Biomarker combinations | |||||||

| Lumachi et al. (2014) 87 | CEA + CA19-9 +

CYFRA 21-1 + MMP7 |

24 | 25 | - | 92% | 96% | |

Table 2. Serum protein biomarkers for pancreatic cancer, 2012–2017.

| Author (year) | Biomarker/

Combination (serum) |

PDAC, number | Benign

controls, number |

Healthy

volunteers, number |

Sensitivity | Specificity | Area

under the curve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single biomarkers | |||||||

| Sogawa et al. (2016) 97 | C4BPA | 52 | 20 | 40 | 67% | 95% | 0.860 |

| Rychlikova et al. (2016) 98 | Osteopontin | 64 | 71 | 48 | - | - | - |

| Lin et al. (2016) 99 | APOA-I | 78 | - | 36 | 96% | 72.2% | 0.880 |

| Lin et al. (2016) 99 | TF | 78 | - | 36 | 75% | 72.8% | 0.760 |

| Guo et al. (2016) 100 | Dysbindin | 250 | 80 | 150 | 81.9% | 84.7% | 0.849 |

| Han et al. (2015) 101 | Dickkopf-1 | 140 | - | 92 | 89.3% | 79.3% | 0.919 |

| Qu et al. (2015) 102 | DCLK1 | 74 | 74 | - | - | - | 0.740 |

| Dong et al. (2015) 103 | Survivin | 80 | - | 80 | - | - | - |

| Gebauer et al. (2014) 104 | EpCAM | 66 | 43 | 104 | 66.7% | 77.5% | - |

| Wang et al. (2014) 105 | MIC-1 | 807 | 165 | 500 | 65.8% | 96.4% | 0.935 |

| Kendrick et al. (2014) 106 | IGFBP2 | 84 | 40 | 84 | 22% | 95% | 0.655 |

| Kendrick et al. (2014) 106 | MSLN | 84 | 40 | 84 | 17% | 95% | 0.668 |

| Kang et al. (2014) 107 | COL6A3 | 44 | 46 | 30 | - | - | 0.975 |

| Willumsen et al. (2013) 108 | C1M | 15 | - | 33 | - | - | 0.830 |

| Willumsen et al. (2013) 108 | C3M | 15 | - | 33 | - | - | 0.880 |

| Willumsen et al. (2013) 108 | C4M | 15 | - | 33 | - | - | 0.940 |

| Willumsen et al. (2013) 108 | C4M12a1 | 15 | - | 33 | - | - | 0.890 |

| Falco et al. (2013) 109 | BAG3 | 52 | - | 44 | 75% | 75% | 0.770 |

| Falco et al. (2013) 109 | BAG3 | 52 | 17 (chronic

pancreatitis) |

- | 81% | 77% | 0.810 |

| Chen et al. (2013) 110 | TTR | 40 | - | 40 | 91% | 47% | 0.730 |

| Gold et al. (2013) 111 | PAM4 | 298 | - | 79 | 76% | 96% | - |

| Gold et al. (2013) 111 | PAM4 | 298 | 120 | - | - | - | 0.890 |

| Poruk et al. (2013) 112 | OPN | 86 | 48 | 86 | - | - | 0.720 |

| Poruk et al. (2013) 112 | TIMP-1 | 86 | 48 | 86 | - | - | 0.770 |

| Lee et al. (2014) 113 | CA 19-9 | 41 | 12 | 44 | 80.4% | 70% | 0.833 |

| Lee et al. (2014) 113 | Human

complement factor B (CFB) |

41 | 12 | 44 | 73.1% | 97.9% | 0.958 |

| Mixed cohorts | |||||||

| Ince et al. (2014) 93 | CEA | 96 (41 PDAC +25 BTC) | 129 | - | 42.7% | 89.9% | 0.713 |

| Ince et al. (2014) 93 | CA19-9 | 96 (41 PDAC +25 BTC) | 129 | - | 49% | 84.5% | 0.701 |

| Ince et al. (2014) 93 | VEGFR3 | 96 (41 PDAC +25 BTC) | 129 | - | 48.4% | 82.9% | 0.622 |

| Ince et al. (2014) 93 | Total antioxidant

capacity |

96 (41 PDAC +25 BTC) | 129 | - | 61.1% | 60.5% | 0.602 |

| Abdel-Razik et al. (2016) 114 | IGF-1 | 47 (25 PDAC + 18 BTC) | 62 | - | 62% | 51% | 0.605 |

| Abdel-Razik et al. (2016) 114 | VEGF | 47 (25 PDAC + 18 BTC) | 62 | - | 58.3% | 57.3% | 0.544 |

| Biomarker combinations | |||||||

| Chen et al. (2013) 110 | TTR + CA19-9 | 40 | - | 40 | 81% | 85% | 0.910 |

| Lee et al. (2014) 113 | CA19-9 + CFB | 41 | 12 | 44 | 90.1% | 97.2% | 0.986 |

| Sogawa et al. (2016) 97 | C4BPA + CA19-9 | 52 | 20 | 40 | 86% | 80% | 0.930 |

| Makawita et al. (2013) 115 | CA19-9 + REG1B | 100 | - | 92 | - | - | 0.880 |

| Makawita et al. (2013) 115 | CA19-9 + SYCN

+ REG1B |

100 | - | 92 | - | - | 0.870 |

| Willumsen et al. (2013) 108 | C1M + C3M +

C4M + C4M12a1 |

15 | - | 33 | - | - | 0.990 |

| Shaw et al. (2014) 116 | IL10 + IL6 +

PDGF + Ca19-9 |

84 | 45 (benign) | - | 93% | 58% | 0.840

|

| Shaw et al. (2014) 116 | IL8 + IL6 +

IL-10 + Ca19-9 |

84 | 32 (chronic

pancreatitis) |

- | 75% | 91% | 0.880

|

| Shaw et al. (2014) 116 | IL8 + IL1b +

Ca 19-9 |

127 | - | 45 | 94% | 100% | 0.857 |

| Brand et al. (2011) 117 | Ca-19 + CEA +

TIMP-1 |

173 | 70 | 120 | 71% | 89% | - |

| Capello et al. (2017) 118 | TIMP1 + LRG1

+ Ca19-9 |

73 | - | 60 | 0.849% | 0.633% | 0.949 |

| Capello et al. (2017) 118 | TIMP1 + LRG1

+ Ca19-9 |

73 | 74 | - | 0.452% | 0.541% | 0.890 |

| Chan et al. (2014) 119 | Ca19-9 + Ca125

+ LAMC2 |

139 | 65 | 10 | 82% | 74%% | 0.870 |

| Makawita et al. (2013) 115 | CA19-9 + REG1B | 82 | 41 | 92 | - | - | 0.875 |

| Makawita et al. (2013) 115 | CA19-9 + SYNC

+ REG1B |

82 | 41 | 92 | - | - | 0.873 |

| Makawita et al. (2013) 115 | CA19-9 + AGR2

+ REG1B |

82 | 41 | 92 | - | - | 0.869 |

BTC, biliary tract cancer; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

In pancreaticobiliary malignancy and PDAC in particular, metastatic disease occurs at a very early stage in tumour development. This is demonstrated by the fact that patients who underwent resection of small primary tumours (<2 cm) with no clinical evidence of metastatic disease had a 5-year survival after pancreatectomy of less than 18% owing to recurrent metastatic disease 39. Tumour development is driven by a series of cumulative genetic abnormalities; therefore, genetic and epigenetic changes have been explored as diagnostic targets in circulating tumour cells, cell-free DNA (cfDNA) and non-coding RNA ( Table 3– Table 5). Owing to the position and composition of pancreaticobiliary tumours, tissue samples are frequently acellular, making diagnostics challenging. Recently, the utility of next-generation sequencing was explored as a technique that allows the detection of low-abundance mutations and abnormalities in small amounts of material 40. Changes in the metabalome are also being explored as a potential diagnostic tool in pancreaticobiliary malignancy 41.

Table 3. Genetic and epigenetic alterations in circulating tumour cells in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and biliary tract cancer, 2013–2017.

| Author (year) | Target | Biliary

tract cancer, number |

Pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma, number |

Benign

lesions, number |

Healthy

volunteers, number |

Detected | Sensitivity | Specificity | Area

under the curve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankeny et al. (2016) 120 | K-ras | - | 72 | 28 | - | - | 75% | 96.4% | 0.867 |

| Kulemann et al. (2016) 121 | K-ras | - | 21 | - | 10 | 80% (stage IIA/IIB)

91% (stage III/IV) |

- | - | - |

| Singh et al. (2015) 122 | ctDNA,

K-ras |

- | - | - | - | - | 65.3% | 61.5% | 0.6681 |

| Kinugasa et al. (2015) 123 | K-ras | - | 141 | 20 | 20 | - | 62.6% | - | - |

| Takai et al. (2015) 124 | K-ras | - | 259 | - | - | - | 29.2% | - | - |

| Sausen et al. (2015) 125 | ctDNA | - | 77 | - | - | - | 43% | - | - |

| Kulemann et al. (2015) 126 | CTC

K-ras |

- | 11 | - | 9 | 75% (stage IIb)

71% (stage III) |

- | - | - |

| Zhang et al. (2015) 127 | DAPI

+, CD45-,

CK +, CEP8 > 2 + |

- | 22

Validation cohort: 11 |

6

8 |

30

10 |

68.2% |

63.6% |

94.4% |

0.84 |

| Wu et al. (2014) 128 | K-ras | - | 36 | - | 25 | - | 0 | 0 | - |

| Bidard et al. (2013) 129 | CK,

CD45 |

- | 79 | - | - | 11% | - | - | - |

| Bobek et al. (2014) 130 | DAPI,

CK, CEA, Vimentin |

- | 24 | - | - | 66.7% | - | - | - |

| Rhim et al. (2014) 131 | DAPI, CD45,

CK, PDX-1 |

- | 11 | 21 | 19 | 78% | - | - | - |

| Iwanicki-Caron et al. (2013) 132 | CTC | - | 40 | - | - | - | 55.5% | 100% | - |

| Sheng et al. (2014) 133 | CTC | - | 18 | - | - | 94.4% | - | - | - |

| Catebacci et al. (2015) 134 | CTC (in portal venous

blood at EUS) |

2 | 14 | - | - | 100% (pulmonary vein blood)

22.2% (peripheral blood) |

- | - | - |

| Earl et al. (2015) 135 | CTC | - | 35 | - | - | 20% | - | - | - |

| Cauley et al. (2015) 136 | Circulating epithelial

cells |

- | 105 | 34 | 9 | 49% | - | - | - |

| Kamande et al. (2013) 137 | DAPI, CD45,

CK |

- | 12 | - | - | 100% | - | - | - |

Table 4. Genetic and epigenetic alterations in circulating cell-free DNA pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and biliary tract cancer, 2013–2017.

| Author (year) | Target | PDAC

or BTC |

Cancer,

number |

Benign

lesions, number |

Healthy

volunteers, number |

Detected | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Takai et al. (2016) 138 | K-ras | PDAC | 107 (non-

operable) |

- | - | 59% | - | - |

| Takai et al. (2015) 124 | cfDNA | PDAC | 48 | 29% | ||||

| Hadano et al. (2016) 139 | K-ras | PDAC | 105 | - | 20 | 31% | - | - |

| Zill et al. (2015) 140 | K-ras, TP53,

APC, FBXW7, SMAD4 |

PDAC | 26 | - | - | - | 92.3% | 100% |

| Earl et al. (2015) 135 | K-ras | PDAC | 31 | - | - | 26% | - | - |

| Kinusaga et al. (2015) 123 | G12V, G12D,

and G12R in codon 12 of K-ras gene |

PDAC | 141 | 20 | 20 | 62% | - | - |

| Sausen et al. (2015) 125 | cfDNA | PDAC | 77 | - | - | 43% | - | - |

| Wu et al. (2014) 128 | K-ras | PDAC | 24 | - | 25 | 72% | - | - |

BTC, biliary tract cancer; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Table 5. Epigenetics: circulating non-coding RNA and DNA methylation markers in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma/biliary tract cancer, 2013–2017.

| Author (year) | MicroRNA | Biliary

tract cancer, number |

Pancreatic

ductal adenocarcinoma, number |

Benign

lesions, number |

Healthy

volunteers, number |

Sensitivity | Specificity | Area

under the curve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circulating non-coding RNA | ||||||||

| Kishimoto et al. (2013) 141 | MiR-21 (↑) | 94

94 |

-

- |

-

23 |

50

- |

85%

72.3% |

100%

91.3% |

0.93

0.83 |

| Wang et al. (2013) 142 | miR-27a-3p + CA19-9(↑) | - | 129 | 103 | 60 | 85.3% | 81.6% | 0.886 |

| Kawaguchi et al. (2013) 143 | miR-221 (↑),

miR-375 (↓) |

- | 47 | - | 30 | - | - | 0.762 |

| Zhao et al. (2013) 144 | miR-192 (↑) | - | 70 | - | 40 | 76% | 55% | 0.63 |

| Carleson et al. (2013) 145 | MiR-375 (↑) | - | 48 | 47 | - | - | - | 0.72 |

| Que et al. (2013) 146 | miR-17-5p (↑)

miR-21 (↑), |

- | 22 | 12 | 8 | - | - | 0.887

0.897 |

| Schultz et al. (2014) 147 | Index I + CA19-9

Index II + CA19-9 |

- | 409 | 25 | 312 | 85%

85% |

88%

86% |

0.93

0.92 |

| Silakit et al. (2014) 148 | MiR-192 (↑) | 11 | - | - | 9 | 74% | 72% | 0.803 |

| Lin et al. (2015) 149 | MiR-492 (↑)

MiR-663a (↑) |

- | 49 | - | 27 | 75%

85% |

70%

80% |

0.787

0.870 |

| Chen et al. (2014) 150 | miR-182 (↑) | - | 109 | 38 | 50 | 64.1% | 82.6% | 0.775 |

| Wang et al. (2015) 151 | MiR-150 (↑) | 15 | - | - | 15 | 80% | 58% | 0.764 |

| Ganepola et al. (2015) 152 | miR-22 (↑),

miR-642b (↑) miR-885-5p (↑) |

- | 11 | - | 11 | 91% | 91% | 0.970 |

| Voigtlander

et al. (2015)

153

(serum) |

MiR-1281 (↑)

MiR-126 (↑) MiR-26a (↑) MiR-30b (↑) MiR-122 (↑) |

31 | - | 40 | - | 55%

68% 52% 52% 32% |

90%

93% 93% 88% 90% |

0.83

0.87 0.78 0.78 0.65 |

| Voigtlander

et al. (2015)

153

(bile) |

miR-412 (↑)

miR-640 (↑) miR-1537 (↑) miR-3189 (↑) |

31 | - | 53 | - | 50%

50% 67% 67% |

89%

92% 90% 89% |

0.81

0.81 0.78 0.80 |

| Abue et al. (2015) 154 | miR-21 (↑),

miR-483-3p (↑) |

- | 32 | 12 | 30 | - | - | 0.790

0.754 |

| Salter et al. (2015) 155 | miR-196a (↑),

miR-196b (↑) |

- | 19 | 10 | 10 | 100% | 90% | 0.99 |

| Kojima et al. (2015) 156 | miR-6075,

miR-4294, miR-6880-5p, miR-6799-5p, miR-125a-3p, miR-4530, miR-6836-3p, miR-4476 |

98 | 100 | 21 | 150 | 80.3% | 97.6% | 0.953 |

| Xu et al. (2015) 157 | miR-486-5p (↑)

miR-938 (↑) |

- | 156 | 142 | 65 | - | - | 0.861

0.693 |

| Madhaven et al. (2015) 158 | PaCIC + miRNA

serum-exosome marker panel |

- | - | - | - | 100% | 80% | - |

| Komatsu et al. (2015) 159 | miR-223 (↑) | - | 71 | - | 67 | 62% | 94.1% | 0.834 |

| Alemar et al. (2016) 160 | MiR-21 (↑)

MiR-34a (↑) |

- | 24 | - | 10 | - | - | 0.889

0.865 |

| Wu et al. (2016) 161 | MiR-150 (↓) | 30 | 30 | 28 | 50 | - | - | - |

| Bernuzzi et al. (2016) 162 | MiR-483-5p(↑)

MiR-194(↑) |

40 | 40 | 70 | 40 | - | - | 0.77

0.74 |

| Kim et al. (2016) 163 | mRNA – CDH3 (↑)

mRNA –IGF2BP3(↑) mRNA – HOXB7 (↑) mRNA – BIRC5 (↑) |

- | 21 | 14 | - | 57.1%

76.2% 71.4% 76.2% |

64.3%

100% 57.1% 64.3% |

0.776

0.476 0.898 0.818 |

| Duell et al. (2017) 164 | MiR-10a (↑)

MiR-10b (↑) MiR-21-5p (↑) MiR-30c (↑) MiR-155 (↑) MiR-212 (↑) |

- | 225 | - | 225 | - | - | 0.66

0.68 0.64 0.71 0.64 0.64 |

| DNA hypermethylation | ||||||||

| Branchi et al. (2016) 165 | SHOX2/ SEPT9 | 20 | - | - | 100 | 0.45% | 0.99% | 0.752 |

2. Bile and biliary brush biomarkers

Patients with an indeterminate stricture on cross-sectional imaging are typically referred for an ERCP and biliary brushing with or without endobilary biopsy to obtain tissue for diagnosis, with or without therapeutic stenting 28. Although these techniques do not compromise resection margins in potentially resectable cases, sensitivity remains low (9–57%) and patients frequently have to undergo multiple procedures to obtain a diagnosis 28– 30. Bile can be easily obtained at the time of ERCP and, owing to its proximity to the tumour, is a potentially important source of diagnostic biomarkers in these cancers ( Table 6). Unfortunately, owing to the invasiveness of ERCP, the role of these biomarkers is limited to diagnosis rather than screening or surveillance in these tumours.

Table 6. Bile and biliary brush biomarkers for pancreatic and biliary tract cancer.

| Author (year) | Biomarker | Pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma, number |

Biliary tract

cancer, number |

Benign

lesions, number |

Healthy

controls, number |

Bile or

biliary brush |

Sensitivity | Specificity | Area

under the curve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single biomarkers | |||||||||

| Dhar et al. (2013) 166 | M2-PK | - | 88 | 79 | 17 | Bile | 90.3% | 84.3% | - |

| Navaneethan

et al. (2015) 167 |

M2-PK | - | - | - | - | Bile | 52.9% | 94.1% | 0.77 |

| Keane (2017) 168 | MCM5 | 24 | 17 | 47 | Biliary

brush |

55.6% | 77.8% | 0.79 | |

| Danese

et al.

(2014) 169 |

MUC5AC | - | 20 | 20 | - | Serum

Bile |

- | - | 0.94

0.99 |

| Farina

et al.

(2014) 170 |

CEAM6 | 23 | 6 | 12 | - | Bile | 93% | 83% | 0.92 |

| Budzynska

et al.

(2013) 171 |

NGAL | 6 | 16 | 18 | - | Bile | 77% | 72% | 0.74 |

| Jiao et al. (2014) 96 | Nucleosides | 202

(gallbladder cancer) |

203 | 205 | Bile | 95.3% | 96.4% | - | |

| Ince et al. (2014) 93 | CE | 41 | 25 | 129 | - | Bile | 57.3% | 68.2% | 0.516 |

| Ince et al. (2014) 93 | CA 19-9 | 41 | 25 | 129 | - | Bile | 74.0% | 34.1% | 0.616 |

| Ince et al. (2014) 93 | VEGFR3 | 41 | 25 | 129 | - | Bile | 56.2% | 79.1% | 0.663 |

| Ince et al. (2014) 93 | Total antioxidant

capacity |

41 | 25 | 129 | - | Bile | 65.6% | 50.4% | 0.581 |

| Abdel-Razik

et al.

(2016) 114 |

IGF-1 | 25 | 18 | 62 | - | Bile | 91.4% | 89.5% | 0.943 |

| Abdel-Razik

et al.

(2016) 114 |

VEGF | 25 | 18 | 62 | - | Bile | 90.3% | 84.9% | 0.915 |

| Kim et al. (2016) 163 | mRNA – CDH3 (↑)

mRNA –IGF2BP3(↑) mRNA – HOXB7 (↑) mRNA – BIRC5 (↑) |

- | 21 | 14 | - | Biliary

brush |

57.1%

76.2% 71.4% 76.2% |

64.3%

100% 57.1% 64.3% |

0.776

0.476 0.898 0.818 |

3. Urinary biomarkers

Urine provides a very easy and acceptable source for biomarker analysis. In BTC, a 42-peptide panel (consisting mostly of fragments of interstitial collagens) correctly identified 35 of 42 BTC patients with a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 79% 42. In PDAC, the three-biomarker panel (LYVE-1, REG1A and TFF1) has been validated in a multi-centre cohort of 371 samples. When comparing PDAC stage I–IIA (resectable disease) with healthy urines, the panel achieved AUCs of 0.97 (95% confidence interval of 0.93–1.00). The performance of the urine biomarker panel in discriminating PDAC stage I–IIA was superior to the performance of serum CA19-9 ( P=0.006) 43 ( Table 7).

Table 7. Summary of urine protein biomarkers for pancreatic and biliary tract cancer, 2013–2017.

| Author (year) | Biomarker/

Combination (urine) |

Pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinoma, number |

Biliary tract

cancer, number |

Benign

cancer/ Chronic pancreatitis, number |

Healthy

volunteers, number |

Sensitivity | Specificity | Area

under the curve |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single biomarker | |||||||||

| Roy et al. (2014) 172 | MMP2 | 51 | - | - | 60 | 70% | 85% | - | |

| Roy et al. (2014) 172 | TIMP-1 | 51 | - | - | 60 | 90% | 70% | - | |

| Jiao et al. (2014) 96 | Nucleosides | - | 202

(gallbladder cancer) |

203 | 205 | 89.4% | 97.1% | - | |

| Metzger et al. (2013) 42 | Urine Proteomic

analysis |

- | 42 | 81 | - | 83% | 79% | 0.87 | |

| Biomarker combinations | |||||||||

| Radon et al. (2015) 43 | LYVE-1 +

REG1A + TFF1 |

192 | - | - | 87 | - | - | 0.89 | |

4. Symptoms and cancer decision support tools

Recently, pre-diagnostic symptom profiles have been investigated as an alternative way of detecting hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) cancers at an early stage 8, 9, 16, 44. It is now recognised that the onset of PDAC and BTC is heralded by a collection of gastrointestinal and constitutional symptoms 45. Although overlap occurs with other benign and malignant conditions, certain symptoms such as back pain, lethargy and new-onset diabetes have been identified as particularly suggestive of PDAC. Commonly performed blood tests such as liver function tests, glucose and haemoglobin also typically become abnormal in the months preceding diagnosis 46. Therefore, cancer decision support tools have been produced from combinations of symptoms and risk factors. In the UK, they have been introduced into general practices in 15 cancer networks to date 8, and their utility is currently being audited 47. Modification to existing tools to enhance their diagnostic accuracy can be expected in the future.

Endoscopy

1. Endoscopic ultrasonography

If there is a mass lesion on cross-sectional imaging, endoscopic ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) provides an alternative method for visualising and sampling the extra-hepatic biliary tree, pancreas, gallbladder or peri-hilar lymph nodes. EUS-FNA has a diagnostic accuracy for PDAC of between 65% and 96% 48, 49. In BTC, a single-centre study reported a sensitivity of 73%, which was significantly better in distal compared with proximal tumours (81% versus 59% respectively, P=0.04) 50. Recently, developed fine core biopsy needles appear to have improved diagnostic accuracy over traditional FNA needles, but randomised trials are awaited 49, 51, 52. Rapid onsite examination by a cytopathologist is used in some centres, particularly in North America, and has been shown to improve the yield of EUS-FNA in individual centres 53, 54 but this trend has not been borne out in recent randomised controlled trials 55.

To improve the diagnostic accuracy of EUS, it can also be combined with novel adjuncts such as contrast agents (SonoVue ®), transient elastography (TE) or confocal laser endomicroscopy (CLE). TE allows the measurement of the tissue firmness, which tends to be increased in malignant tissue. In a recent single-centre study from the UK, quantitative strain measurements were found to have high sensitivity but low specificity for the detection of PDAC 56. The technology to perform the techniques is available on most modern EUS machines and adds little time to the overall procedure time. The technique can be performed equally well by endosonographers with limited experience 57, 58 and is particularly advantageous in cases where the diagnosis remains uncertain after standard EUS has been performed 59. Contrast-enhanced EUS is performed with agents such as SonoVue ® and allows visualisation of the early arterial phase and late parenchymal phase enhancement of the pancreas. Pancreatic tumours are generally hypovascular compared with the surrounding parenchyma 60, 61. Dynamic contrast EUS is a relatively novel method that allows the non-invasive quantification of the tumour perfusion compared with the pancreatic parenchyma by using software that is now built into a number of EUS scanners. The use of this technology is evolving but is expected to be most applicable when predicting tumour response to chemotherapeutic agents, particularly new drugs against vascular angioneogenesis 62, 63.

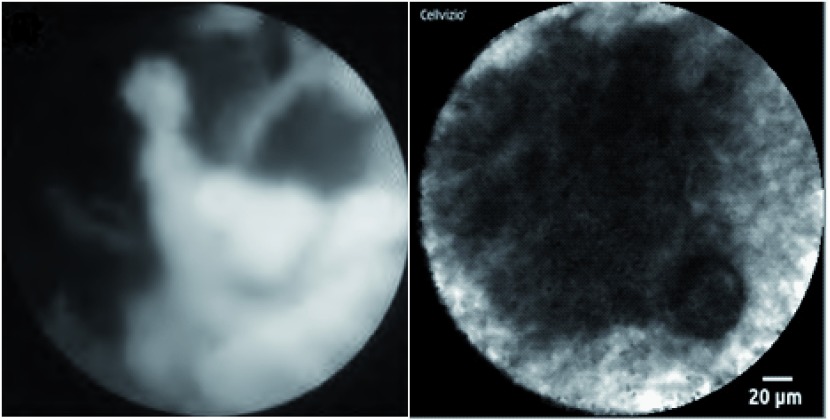

Recently, a needle-based confocal endomicroscope has also been developed which can be passed through a 19G FNA needle to assess indeterminate masses, cysts or lymph nodes. Malignancy in the hepatobilary tract is identified by the presence of irregular vessels, vascular leakage and large dark clumps ( Figure 1) 64. In a recent study of 25 patients with indeterminate pancreatic masses referred for EUS-FNA, needle-based CLE was shown to be a safe and feasible technique 65.

Figure 1. Novel diagnostic adjuncts to ERCP and EUS.

( a) Cholangioscopic view of a malignant hilar stricture with visualisation of the ulcerated, friable biliary mucosa via the Spyglass cholangioscope system (Boston Scientific Corp, Massachusetts, USA). ( b) Confocal endomicroscopic image of pancreatic cancer, showing characteristic black clumps. Image was obtained using the Cellvizio AQ-Flex® probe which was introduced to the tumour via 19G FNA needle at the time of EUS.

2. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

ERCP is typically undertaken when imaging demonstrates an indeterminate biliary stricture and tissue acquisition is required for cytological or histological assessment. Biliary brush cytology and endobiliary biopsy have a sensitivity for malignancy of 9–57% 29, 30, 66, 67. Most HPB tumours exhibit chromosomal aneuploidy 68; therefore, in some centres, fluorescence in situ hybridisation and digital image analysis are used to assess for the presence of DNA abnormalities in brush cytology 30, 69. Although these techniques have been adopted by only a few centres, the presence of polysomy is highly suggestive of BTC 30, 69.

Poor diagnostic accuracy in biliary brush and endobiliary samples has been attributed to their being non-targeted samples obtained with only fluoroscopic guidance 70. The single-operator cholangioscopy system (SpyGlass, Boston Scientific Corporation, Natick, MA, USA) introduced in 2006 and now superseded by the SpyGlass DS system enables intrabiliary biopsies under direct vision via small disposable forceps ( Figure 1). In a recent systematic review, the sensitivity and specificity of cholangioscopy-guided biopsies in the diagnosis of malignant biliary strictures were 60.1% and 98.0%, respectively 71. Higher sensitivities are observed for intrinsic biliary malignancy compared with extrinsic compressing tumours 72. Several techniques have been employed to augment the visualised mucosa during cholangioscopy, including chromendoscopy with methylene blue 73– 75, narrow-band imaging 76, 77 and autofluorescence 78.

During ERCP, a “CholangioFlex” confocal probe (Mauna Kea Technologies, Paris, France) can be placed down the working channel of a cholangioscope or duodenoscope to obtain real-time CLE images, which are akin to standard histology ( Figure 1). If the images obtained from a point on the biliary mucosa contain dark areas, this is highly suggestive of malignancy 79, 80. The diagnostic accuracy of probe-based CLE was recently validated in a prospective multi-centre international study with 112 patients (71 with malignant lesions). Tissue sampling alone had a sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy of 56%, 100% and 72%, respectively. In comparison, ERCP with probe-based CLE had a sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy of 89%, 71% and 82%, respectively. Diagnostic accuracy increased to 88% when probe-based CLE and tissue sampling results were combined 81. CLE is also feasible in the pancreatic duct during pancreaticoscopy but, owing to concerns over pancreatitis, is rarely used. In a case report by Meining et al., the presence of a main duct-intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia was confirmed by clear views of typical finger-like projections 82. Intraductal ultrasound in small studies has also been shown to have a diagnostic accuracy of up to 90% 83.

Conclusions

Currently, the most widely used tumour marker in pancreaticobiliary malignancy is CA19-9. However, its use is limited by its elevation in a number of other benign and malignant conditions. Furthermore, it is not produced in approximately 7% of the population who are Lewis antigen–negative and is often undetectable when tumours are small. Over the last few years, a number of very promising biomarker panels have been identified which can detect tumours at an early stage when curative intervention could be possible. These markers are subject to ongoing validation studies but appear likely to be implemented into screening programmes, particularly for high-risk groups, in the near future. Novel endoscopic techniques such as per-oral cholangioscopy and confocal endomicroscopy can enhance the diagnostic accuracy of standard techniques and are increasingly available in large-volume centres worldwide.

Abbreviations

AUC, area under the curve; BTC, biliary tract cancer; CA, carbohydrate antigen; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CLE, confocal laser endomicroscopy; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; HPB, hepato-pancreato-biliary; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; TE, transient elastography.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

Peter Vilmann, Gastro Unit, Department of Surgery, Herlev Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Herlev, Denmark

Pia Helene Klausen, Gastro Unit, Department of Surgery, Herlev Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Herlev, Denmark

Vangelis Kalaitzakis, Gastro Unit, Department of Surgery, Herlev Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Herlev, Denmark

Pietro Fusaroli, Gastroenterology Unit, Department of Medical and Surgical Science, Hospital of Imola, University of Bologna, Imola, BO, Italy

Funding Statement

SPP is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant P01CA8420. Part of the work was undertaken at University College London Hospitals/University College London, which received a portion of funding from the Department of Health’s National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; referees: 2 approved]

References

- 1. CRUK: Pancreatic cancer statistics.2013. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khan SA, Toledano MB, Taylor-Robinson SD: Epidemiology, risk factors, and pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2008;10(2):77–82. 10.1080/13651820801992641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. CRUK: Cancer Research UK Cancer Stats Incidence 2008.2011. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coupland VH, Kocher HM, Berry DP, et al. : Incidence and survival for hepatic, pancreatic and biliary cancers in England between 1998 and 2007. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(4):e207–14. 10.1016/j.canep.2012.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, et al. : SEER Cancer Statistics. Review, 1975–2007. National Cancer Institute Bethesda, MD based on November 2009 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2010.2010. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 6. Curado MP, Edwards B, Shin HR, et al.: Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. IARC Scientific Publications No 160,2007;9 Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, et al. : Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer--analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(2):78–85. 10.1056/NEJM200007133430201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C: Identifying patients with suspected pancreatic cancer in primary care: derivation and validation of an algorithm. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(594):e38–45. 10.3399/bjgp12X616355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stapley S, Peters TJ, Neal RD, et al. : The risk of pancreatic cancer in symptomatic patients in primary care: a large case-control study using electronic records. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(12):1940–4. 10.1038/bjc.2012.190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Silverman DT, Dunn JA, Hoover RN, et al. : Cigarette smoking and pancreas cancer: a case-control study based on direct interviews. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86(20):1510–6. 10.1093/jnci/86.20.1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fuchs CS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, et al. : A prospective study of cigarette smoking and the risk of pancreatic cancer. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(19):2255–60. 10.1001/archinte.1996.00440180119015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muscat JE, Stellman SD, Hoffmann D, et al. : Smoking and pancreatic cancer in men and women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6(1):15–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bonelli L, Aste H, Bovo P, et al. : Exocrine pancreatic cancer, cigarette smoking, and diabetes mellitus: a case-control study in northern Italy. Pancreas. 2003;27(2):143–9. 10.1097/00006676-200308000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larsson SC, Permert J, Håkansson N, et al. : Overall obesity, abdominal adiposity, diabetes and cigarette smoking in relation to the risk of pancreatic cancer in two Swedish population-based cohorts. Br J Cancer. 2005;93(11):1310–5. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hassan MM, Bondy ML, Wolff RA, et al. : Risk factors for pancreatic cancer: case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(12):2696–707. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01510.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gullo L, Tomassetti P, Migliori M, et al. : Do early symptoms of pancreatic cancer exist that can allow an earlier diagnosis? Pancreas. 2001;22(2):210–3. 10.1097/00006676-200103000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferlay JS, Bray F, Forman D, et al. : GLOBOCAN 2008 v2.0. Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. accessed on 03/08/2013.2008. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shaib Y, El-Serag HB: The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24(2):115–25. 10.1055/s-2004-828889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Claessen MM, Vleggaar FP, Tytgat KM, et al. : High lifetime risk of cancer in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2009;50(1):158–64. 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tyson GL, El-Serag HB: Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):173–84. 10.1002/hep.24351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chapman RW: Risk factors for biliary tract carcinogenesis. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(Suppl 4):308–11. 10.1093/annonc/10.suppl_4.S308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Groen PC, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF, et al. : Biliary tract cancers. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(18):1368–78. 10.1056/NEJM199910283411807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saluja SS, Sharma R, Pal S, et al. : Differentiation between benign and malignant hilar obstructions using laboratory and radiological investigations: a prospective study. HPB (Oxford). 2007;9(5):373–82. 10.1080/13651820701504207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fernández-Esparrach G, Ginès A, Sánchez M, et al. : Comparison of endoscopic ultrasonography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in the diagnosis of pancreatobiliary diseases: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(8):1632–9. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sai JK, Suyama M, Kubokawa Y, et al. : Early detection of extrahepatic bile-duct carcinomas in the nonicteric stage by using MRCP followed by EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70(1):29–36. 10.1016/j.gie.2008.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee JY: [Multidetector-row CT of malignant biliary obstruction]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;48(4):247–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kalaitzakis E, Levy M, Kamisawa T, et al. : Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography does not reliably distinguish IgG4-associated cholangitis from primary sclerosing cholangitis or cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(9):800–803.e2. 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. De Bellis M, Sherman S, Fogel EL, et al. : Tissue sampling at ERCP in suspected malignant biliary strictures (Part 1). Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(4):552–61. 10.1016/S0016-5107(02)70442-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harewood GC, Baron TH, Stadheim LM, et al. : Prospective, blinded assessment of factors influencing the accuracy of biliary cytology interpretation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(8):1464–9. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30845.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moreno Luna LE, Kipp B, Halling KC, et al. : Advanced cytologic techniques for the detection of malignant pancreatobiliary strictures. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(4):1064–72. 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 31. Klein AP, Lindström S, Mendelsohn JB, et al. : An absolute risk model to identify individuals at elevated risk for pancreatic cancer in the general population. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e72311. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ariyama J, Suyama M, Ogawa K, et al. : [Screening of pancreatic neoplasms and the diagnostic rate of small pancreatic neoplasms]. Nihon Rinsho. 1986;44(8):1729–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Locker GY, Hamilton S, Harris J, et al. : ASCO 2006 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in gastrointestinal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):5313–27. 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bonney GK, Craven RA, Prasad R, et al. : Circulating markers of biliary malignancy: opportunities in proteomics? Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(2):149–58. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70027-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hotakainen K, Tanner P, Alfthan H, et al. : Comparison of three immunoassays for CA 19-9. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;400(1–2):123–7. 10.1016/j.cca.2008.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Abi-Rached B, Neugut AI: Diagnostic and management issues in gallbladder carcinoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 1995;9(1):19–24; discussion 24, 27, 30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lazaridis KN, Gores GJ: Primary sclerosing cholangitis and cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26(1):42–51. 10.1055/s-2006-933562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Khan SA, Davidson BR, Goldin RD, et al. : Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: an update. Gut. 2012;61(12):1657–69. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Agarwal B, Correa AM, Ho L: Survival in pancreatic carcinoma based on tumor size. Pancreas. 2008;36(1):e15–20. 10.1097/mpa.0b013e31814de421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Malgerud L, Lindberg J, Wirta V, et al. : Bioinformatory-assisted analysis of next-generation sequencing data for precision medicine in pancreatic cancer. Mol Oncol. 2017. 10.1002/1878-0261.12108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 41. Lindahl A, Heuchel R, Forshed J, et al. : Discrimination of pancreatic cancer and pancreatitis by LC-MS metabolomics. Metabolomics. 2017;13(5):61. 10.1007/s11306-017-1199-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 42. Metzger J, Negm AA, Plentz RR, et al. : Urine proteomic analysis differentiates cholangiocarcinoma from primary sclerosing cholangitis and other benign biliary disorders. Gut. 2013;62(1):122–30. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 43. Radon TP, Massat NJ, Jones R, et al. : Identification of a Three-Biomarker Panel in Urine for Early Detection of Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(15):3512–21. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Holly EA, Chaliha I, Bracci PM, et al. : Signs and symptoms of pancreatic cancer: a population-based case-control study in the San Francisco Bay area. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(6):510–7. 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00171-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Keane MG, Bramis K, Pereira SP, et al. : Systematic review of novel ablative methods in locally advanced pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(9):2267–78. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i9.2267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Keane MG, Horsfall L, Rait G, et al. : A case-control study comparing the incidence of early symptoms in pancreatic and biliary tract cancer. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11):e005720. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Macmillan: Early diagnosis programme.2014; (accessed 15th May 2014). Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dumonceau JM, Polkowski M, Larghi A, et al. : Indications, results, and clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling in gastroenterology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2011;43(10):897–912. 10.1055/s-0030-1256754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jenssen C, Hocke M, Fusaroli P, et al. : EFSUMB Guidelines on Interventional Ultrasound (INVUS), Part IV - EUS-guided interventions: General Aspects and EUS-guided Sampling (Short Version). Ultraschall Med. 2016;37(2):157–69. 10.1055/s-0035-1553788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 50. Mohamadnejad M, DeWitt JM, Sherman S, et al. : Role of EUS for preoperative evaluation of cholangiocarcinoma: a large single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(1):71–8. 10.1016/j.gie.2010.08.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 51. Fuccio L, Hassan C, Laterza L, et al. : The role of K- ras gene mutation analysis in EUS-guided FNA cytology specimens for the differential diagnosis of pancreatic solid masses: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78(4):596–608. 10.1016/j.gie.2013.04.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang J, Wu X, Yin P, et al. : Comparing endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) versus fine needle biopsy (FNB) in the diagnosis of solid lesions: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:198. 10.1186/s13063-016-1316-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 53. Klapman JB, Logrono R, Dye CE, et al. : Clinical impact of on-site cytopathology interpretation on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(6):1289–94. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07472.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. van Riet PA, Cahen DL, Poley JW, et al. : Mapping international practice patterns in EUS-guided tissue sampling: outcome of a global survey. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4(3):E360–70. 10.1055/s-0042-101023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wani S, Mullady D, Early DS, et al. : The clinical impact of immediate on-site cytopathology evaluation during endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of pancreatic masses: a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(10):1429–39. 10.1038/ajg.2015.262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dawwas MF, Taha H, Leeds JS, et al. : Diagnostic accuracy of quantitative EUS elastography for discriminating malignant from benign solid pancreatic masses: a prospective, single-center study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76(5):953–61. 10.1016/j.gie.2012.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Soares JB, Iglesias-Garcia J, Goncalves B, et al. : Interobserver agreement of EUS elastography in the evaluation of solid pancreatic lesions. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4(3):244–9. 10.4103/2303-9027.163016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fusaroli P, Kypraios D, Mancino MG, et al. : Interobserver agreement in contrast harmonic endoscopic ultrasound. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27(6):1063–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Iglesias-Garcia J, Lindkvist B, Lariño-Noia J, et al. : Differential diagnosis of solid pancreatic masses: contrast-enhanced harmonic (CEH-EUS), quantitative-elastography (QE-EUS), or both? United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5(2):236–46. 10.1177/2050640616640635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 60. Dietrich CF: Contrast-enhanced low mechanical index endoscopic ultrasound (CELMI-EUS). Endoscopy. 2009;41(Suppl 2):E43–4. 10.1055/s-0028-1119491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Dietrich CF, Braden B, Hocke M, et al. : Improved characterisation of solitary solid pancreatic tumours using contrast enhanced transabdominal ultrasound. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134(6):635–43. 10.1007/s00432-007-0326-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dietrich CF, Dong Y, Froehlich E, et al. : Dynamic contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound: A quantification method. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6(1):12–20. 10.4103/2303-9027.193595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 63. Fusaroli P, Kypreos D, Alma Petrini CA, et al. : Scientific publications in endoscopic ultrasonography: changing trends in the third millennium. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(5):400–4. 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181fbde42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Giovannini M, Thomas B, Erwan B, et al. : Endoscopic ultrasound elastography for evaluation of lymph nodes and pancreatic masses: a multicenter study. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(13):1587–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Karstensen J, Cartana T, Pia K, et al. : Endoscopic ultrasound-guided needle confocal laser endomicroscopy in pancreatic masses. Endosc Ultrasound. 2014;3(Suppl 1):S2–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. de Bellis M, Sherman S, Fogel EL, et al. : Tissue sampling at ERCP in suspected malignant biliary strictures (Part 2). Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(5):720–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Baron TH, Harewood GC, Rumalla A, et al. : A prospective comparison of digital image analysis and routine cytology for the identification of malignancy in biliary tract strictures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(3):214–9. 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00006-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bergquist A, Tribukait B, Glaumann H, et al. : Can DNA cytometry be used for evaluation of malignancy and premalignancy in bile duct strictures in primary sclerosing cholangitis? J Hepatol. 2000;33(6):873–7. 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80117-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bangarulingam SY, Bjornsson E, Enders F, et al. : Long-term outcomes of positive fluorescence in situ hybridization tests in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):174–80. 10.1002/hep.23277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 70. Tischendorf JJ, Krüger M, Trautwein C, et al. : Cholangioscopic characterization of dominant bile duct stenoses in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Endoscopy. 2006;38(7):665–9. 10.1055/s-2006-925257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Navaneethan U, Hasan MK, Lourdusamy V, et al. : Single-operator cholangioscopy and targeted biopsies in the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary strictures: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(4):608–14.e2. 10.1016/j.gie.2015.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chen YK, Parsi MA, Binmoeller KF, et al. : Single-operator cholangioscopy in patients requiring evaluation of bile duct disease or therapy of biliary stones (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(4):805–14. 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Larghi A, Waxman I: Endoscopic direct cholangioscopy by using an ultra-slim upper endoscope: a feasibility study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(6):853–7. 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 74. Hoffman A, Kiesslich R, Bittinger F, et al. : Methylene blue-aided cholangioscopy in patients with biliary strictures: feasibility and outcome analysis. Endoscopy. 2008;40(7):563–71. 10.1055/s-2007-995688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hoffman A, Kiesslich R, Moench C, et al. : Methylene blue-aided cholangioscopy unravels the endoscopic features of ischemic-type biliary lesions after liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(5):1052–8. 10.1016/j.gie.2007.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, et al. : Peroral cholangioscopic diagnosis of biliary-tract diseases by using narrow-band imaging (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(4):730–6. 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lu X, Itoi T, Kubota K: Cholangioscopy by using narrow-band imaging and transpapillary radiotherapy for mucin-producing bile duct tumor. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(6):e34–5. 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Itoi T, Neuhaus H, Chen YK: Diagnostic value of image-enhanced video cholangiopancreatoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009;19(4):557–66. 10.1016/j.giec.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Meining A, Frimberger E, Becker V, et al. : Detection of cholangiocarcinoma in vivo using miniprobe-based confocal fluorescence microscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(9):1057–60. 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Giovannini M, Bories E, Monges G, et al. : Results of a phase I-II study on intraductal confocal microscopy (IDCM) in patients with common bile duct (CBD) stenosis. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(7):2247–53. 10.1007/s00464-010-1542-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Slivka A, Gan I, Jamidar P, et al. : Validation of the diagnostic accuracy of probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy for the characterization of indeterminate biliary strictures: results of a prospective multicenter international study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(2):282–90. 10.1016/j.gie.2014.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Meining A, Phillip V, Gaa J, et al. : Pancreaticoscopy with miniprobe-based confocal laser-scanning microscopy of an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(6):1178–80. 10.1016/j.gie.2008.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Menzel J, Poremba C, Dietl KH, et al. : Preoperative diagnosis of bile duct strictures--comparison of intraductal ultrasonography with conventional endosonography. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(1):77–82. 10.1080/003655200750024579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 84. Han Y, Zhang W, Liu Y: Identification of hepatoma-derived growth factor as a potential prognostic and diagnostic marker for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2013;37(10):2419–27. 10.1007/s00268-013-2132-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ruzzenente A, Iacono C, Conci S, et al. : A novel serum marker for biliary tract cancer: diagnostic and prognostic values of quantitative evaluation of serum mucin 5AC (MUC5AC). Surgery. 2014;155(4):633–9. 10.1016/j.surg.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Voigtländer T, David S, Thamm K, et al. : Angiopoietin-2 and biliary diseases: elevated serum, but not bile levels are associated with cholangiocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97046. 10.1371/journal.pone.0097046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Lumachi F, Lo Re G, Tozzoli R, et al. : Measurement of serum carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, cytokeratin-19 fragment and matrix metalloproteinase-7 for detecting cholangiocarcinoma: a preliminary case-control study. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(11):6663–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Wang YF, Feng FL, Zhao XH, et al. : Combined detection tumor markers for diagnosis and prognosis of gallbladder cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(14):4085–92. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.4085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Liu MC, Jiang L, Hong HJ, et al. : Serum vascular endothelial growth factors C and D as forecast tools for patients with gallbladder carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(8):6305–12. 10.1007/s13277-015-3316-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Huang L, Chen W, Liang P, et al. : Serum CYFRA 21-1 in Biliary Tract Cancers: A Reliable Biomarker for Gallbladder Carcinoma and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(5):1273–83. 10.1007/s10620-014-3472-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Nigam J, Chandra A, Kazmi HR, et al. : Expression of serum survivin protein in diagnosis and prognosis of gallbladder cancer: a comparative study. Med Oncol. 2014;31(9):167. 10.1007/s12032-014-0167-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Rucksaken R, Pairojkul C, Pinlaor P, et al. : Plasma autoantibodies against heat shock protein 70, enolase 1 and ribonuclease/angiogenin inhibitor 1 as potential biomarkers for cholangiocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e103259. 10.1371/journal.pone.0103259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Ince AT, Yildiz K, Baysal B, et al. : Roles of serum and biliary CEA, CA19-9, VEGFR3, and TAC in differentiating between malignant and benign biliary obstructions. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014;25(2):162–9. 10.5152/tjg.2014.6056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rucksaken R, Charoensuk L, Pinlaor P, et al. : Plasma orosomucoid 2 as a potential risk marker of cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2017;18(1):27–34. 10.3233/CBM-160670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 95. Rose JB, Correa-Gallego C, Li Y, et al. : The Role of Biliary Carcinoembryonic Antigen-Related Cellular Adhesion Molecule 6 (CEACAM6) as a Biomarker in Cholangiocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150195. 10.1371/journal.pone.0150195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 96. Jiao X, Mo Y, Wu Y, et al. : Upregulated plasma and urinary levels of nucleosides as biological markers in the diagnosis of primary gallbladder cancer. J Sep Sci. 2014;37(21):3033–44. 10.1002/jssc.201400638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Sogawa K, Takano S, Iida F, et al. : Identification of a novel serum biomarker for pancreatic cancer, C4b-binding protein α-chain (C4BPA) by quantitative proteomic analysis using tandem mass tags. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(8):949–56. 10.1038/bjc.2016.295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 98. Rychlíková J, Vecka M, Jáchymová M: Osteopontin as a discriminating marker for pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. Cancer Biomark. 2016;17(1):55–65. 10.3233/CBM-160617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lin C, Wu WC, Zhao GC, et al. : ITRAQ-based quantitative proteomics reveals apolipoprotein A-I and transferrin as potential serum markers in CA19-9 negative pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(31):e4527. 10.1097/MD.0000000000004527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 100. Guo X, Lv X, Fang C, et al. : Dysbindin as a novel biomarker for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma identified by proteomic profiling. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(8):1821–9. 10.1002/ijc.30227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 101. Han SX, Zhou X, Sui X, et al. : Serum dickkopf-1 is a novel serological biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6(23):19907–17. 10.18632/oncotarget.4529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Qu D, Johnson J, Chandrakesan P, et al. : Doublecortin-like kinase 1 is elevated serologically in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and widely expressed on circulating tumor cells. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0118933. 10.1371/journal.pone.0118933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Dong H, Qian D, Wang Y, et al. : Survivin expression and serum levels in pancreatic cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:189. 10.1186/s12957-015-0605-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Gebauer F, Struck L, Tachezy M, et al. : Serum EpCAM expression in pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(9):4741–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Wang X, Li Y, Tian H, et al. : Macrophage inhibitory cytokine 1 (MIC-1/GDF15) as a novel diagnostic serum biomarker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:578. 10.1186/1471-2407-14-578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Kendrick ZW, Firpo MA, Repko RC, et al. : Serum IGFBP2 and MSLN as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for pancreatic cancer. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16(7):670–6. 10.1111/hpb.12199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Kang CY, Wang J, Axell-House D, et al. : Clinical significance of serum COL6A3 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(1):7–15. 10.1007/s11605-013-2326-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Willumsen N, Bager CL, Leeming DJ, et al. : Extracellular matrix specific protein fingerprints measured in serum can separate pancreatic cancer patients from healthy controls. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:554. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Falco A, Rosati A, Festa M, et al. : BAG3 is a novel serum biomarker for pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(7):1178–80. 10.1038/ajg.2013.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Chen J, Chen LJ, Xia YL, et al. : Identification and verification of transthyretin as a potential biomarker for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139(7):1117–27. 10.1007/s00432-013-1422-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Gold DV, Gaedcke J, Ghadimi BM, et al. : PAM4 enzyme immunoassay alone and in combination with CA 19-9 for the detection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2013;119(3):522–8. 10.1002/cncr.27762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Poruk KE, Firpo MA, Scaife CL, et al. : Serum osteopontin and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2013;42(2):193–7. 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31825e354d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Lee MJ, Na K, Jeong SK, et al. : Identification of human complement factor B as a novel biomarker candidate for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(11):4878–88. 10.1021/pr5002719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Abdel-Razik A, ElMahdy Y, Hanafy EE, et al. : Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Malignant and Benign Biliary Obstructions. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351(3):259–64. 10.1016/j.amjms.2015.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 115. Makawita S, Dimitromanolakis A, Soosaipillai A, et al. : Validation of four candidate pancreatic cancer serological biomarkers that improve the performance of CA19.9. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:404. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Shaw VE, Lane B, Jenkinson C, et al. : Serum cytokine biomarker panels for discriminating pancreatic cancer from benign pancreatic disease. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:114. 10.1186/1476-4598-13-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Brand RE, Nolen BM, Zeh HJ, et al. : Serum biomarker panels for the detection of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(4):805–16. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Capello M, Bantis LE, Scelo G, et al. : Sequential Validation of Blood-Based Protein Biomarker Candidates for Early-Stage Pancreatic Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(4):djw266. 10.1093/jnci/djw266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 119. Chan A, Prassas I, Dimitromanolakis A, et al. : Validation of biomarkers that complement CA19.9 in detecting early pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(22):5787–95. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Ankeny JS, Court CM, Hou S, et al. : Circulating tumour cells as a biomarker for diagnosis and staging in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(12):1367–75. 10.1038/bjc.2016.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 121. Kulemann B, Liss AS, Warshaw AL, et al. : KRAS mutations in pancreatic circulating tumor cells: a pilot study. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(6):7547–54. 10.1007/s13277-015-4589-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 122. Singh N, Gupta S, Pandey RM, et al. : High levels of cell-free circulating nucleic acids in pancreatic cancer are associated with vascular encasement, metastasis and poor survival. Cancer Invest. 2015;33(3):78–85. 10.3109/07357907.2014.1001894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Kinugasa H, Nouso K, Miyahara K, et al. : Detection of K-ras gene mutation by liquid biopsy in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(13):2271–80. 10.1002/cncr.29364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Takai E, Totoki Y, Nakamura H, et al. : Clinical utility of circulating tumor DNA for molecular assessment in pancreatic cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5: 18425. 10.1038/srep18425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Sausen M, Phallen J, Adleff V, et al. : Clinical implications of genomic alterations in the tumour and circulation of pancreatic cancer patients. Nat Commun. 2015;6: 7686. 10.1038/ncomms8686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Kulemann B, Pitman MB, Liss AS, et al. : Circulating tumor cells found in patients with localized and advanced pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2015;44(4):547–50. 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Zhang Y, Wang F, Ning N, et al. : Patterns of circulating tumor cells identified by CEP8, CK and CD45 in pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):1228–33. 10.1002/ijc.29070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Wu J, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, et al. : Co-amplification at lower denaturation-temperature PCR combined with unlabled-probe high-resolution melting to detect KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations in plasma-circulating DNA of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cases. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(24):10647–52. 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.24.10647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Bidard FC, Huguet F, Louvet C, et al. : Circulating tumor cells in locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: the ancillary CirCe 07 study to the LAP 07 trial. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(8):2057–61. 10.1093/annonc/mdt176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Bobek V, Gurlich R, Eliasova P, et al. : Circulating tumor cells in pancreatic cancer patients: enrichment and cultivation. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(45):17163–70. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Rhim AD, Thege FI, Santana SM, et al. : Detection of circulating pancreas epithelial cells in patients with pancreatic cystic lesions. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(3):647–51. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 132. Iwanicki-Caron I, Basile P, Toure E, et al. : Usefulness of circulating tumor cell detection in pancreatic adenocarcinoma diagnosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(1):152–5. 10.1038/ajg.2012.367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Sheng W, Ogunwobi OO, Chen T, et al. : Capture, release and culture of circulating tumor cells from pancreatic cancer patients using an enhanced mixing chip. Lab Chip. 2014;14(1):89–98. 10.1039/c3lc51017d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Catenacci DV, Chapman CG, Xu P, et al. : Acquisition of Portal Venous Circulating Tumor Cells From Patients With Pancreaticobiliary Cancers by Endoscopic Ultrasound. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1794–1803.e4. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Earl J, Garcia-Nieto S, Martinez-Avila JC, et al. : Circulating tumor cells (Ctc) and kras mutant circulating free Dna (cfdna) detection in peripheral blood as biomarkers in patients diagnosed with exocrine pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:797. 10.1186/s12885-015-1779-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Cauley CE, Pitman MB, Zhou J, et al. : Circulating Epithelial Cells in Patients with Pancreatic Lesions: Clinical and Pathologic Findings. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(3):699–707. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Kamande JW, Hupert ML, Witek MA, et al. : Modular microsystem for the isolation, enumeration, and phenotyping of circulating tumor cells in patients with pancreatic cancer. Anal Chem. 2013;85(19):9092–100. 10.1021/ac401720k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Takai E, Totoki Y, Nakamura H, et al. : Clinical Utility of Circulating Tumor DNA for Molecular Assessment and Precision Medicine in Pancreatic Cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;924:13–7. 10.1007/978-3-319-42044-8_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 139. Hadano N, Murakami Y, Uemura K, et al. : Prognostic value of circulating tumour DNA in patients undergoing curative resection for pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(1):59–65. 10.1038/bjc.2016.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 140. Zill OA, Greene C, Sebisanovic D, et al. : Cell-Free DNA Next-Generation Sequencing in Pancreatobiliary Carcinomas. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(10):1040–8. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Kishimoto T, Eguchi H, Nagano H, et al. : Plasma miR-21 is a novel diagnostic biomarker for biliary tract cancer. Cancer Sci. 2013;104(12):1626–31. 10.1111/cas.12300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Wang WS, Liu LX, Li GP, et al. : Combined serum CA19-9 and miR-27a-3p in peripheral blood mononuclear cells to diagnose pancreatic cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2013;6(4):331–8. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Kawaguchi T, Komatsu S, Ichikawa D, et al. : Clinical impact of circulating miR-221 in plasma of patients with pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(2):361–9. 10.1038/bjc.2012.546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Zhao C, Zhang J, Zhang S, et al. : Diagnostic and biological significance of microRNA-192 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2013;30(1):276–84. 10.3892/or.2013.2420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Carlsen AL, Joergensen MT, Knudsen S, et al. : Cell-free plasma microRNA in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and disease controls. Pancreas. 2013;42(7):1107–13. 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318296bb34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Que R, Ding G, Chen J, et al. : Analysis of serum exosomal microRNAs and clinicopathologic features of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:219. 10.1186/1477-7819-11-219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Schultz NA, Dehlendorff C, Jensen BV, et al. : MicroRNA biomarkers in whole blood for detection of pancreatic cancer. JAMA. 2014;311(4):392–404. 10.1001/jama.2013.284664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 148. Silakit R, Loilome W, Yongvanit P, et al. : Circulating miR-192 in liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma patients: a prospective prognostic indicator. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21(12):864–72. 10.1002/jhbp.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Lin M, Chen W, Huang J, et al. : Aberrant expression of microRNAs in serum may identify individuals with pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7(12):5226–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Chen Q, Yang L, Xiao Y, et al. : Circulating microRNA-182 in plasma and its potential diagnostic and prognostic value for pancreatic cancer. Med Oncol. 2014;31(11):225. 10.1007/s12032-014-0225-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Wang S, Yin J, Li T, et al. : Upregulated circulating miR-150 is associated with the risk of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2015;33(2):819–25. 10.3892/or.2014.3641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Ganepola GA, Rutledge JR, Suman P, et al. : Novel blood-based microRNA biomarker panel for early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;6(1):22–33. 10.4251/wjgo.v6.i1.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Voigtländer T, Gupta SK, Thum S, et al. : MicroRNAs in Serum and Bile of Patients with Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis and/or Cholangiocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139305. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 154. Abue M, Yokoyama M, Shibuya R, et al. : Circulating miR-483-3p and miR-21 is highly expressed in plasma of pancreatic cancer. Int J Oncol. 2015;46(2):539–47. 10.3892/ijo.2014.2743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Slater EP, Strauch K, Rospleszcz S, et al. : MicroRNA-196a and -196b as Potential Biomarkers for the Early Detection of Familial Pancreatic Cancer. Transl Oncol. 2014;7(4):464–71. 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Kojima M, Sudo H, Kawauchi J, et al. : MicroRNA markers for the diagnosis of pancreatic and biliary-tract cancers. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0118220. 10.1371/journal.pone.0118220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Xu J, Cao Z, Liu W, et al. : Plasma miRNAs Effectively Distinguish Patients With Pancreatic Cancer From Controls: A Multicenter Study. Ann Surg. 2016;263(6):1173–9. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 158. Madhavan B, Yue S, Galli U, et al. : Combined evaluation of a panel of protein and miRNA serum-exosome biomarkers for pancreatic cancer diagnosis increases sensitivity and specificity. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(11):2616–27. 10.1002/ijc.29324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Komatsu S, Ichikawa D, Miyamae M, et al. : Malignant potential in pancreatic neoplasm; new insights provided by circulating miR-223 in plasma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15(6):773–85. 10.1517/14712598.2015.1029914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Alemar B, Izetti P, Gregório C, et al. : miRNA-21 and miRNA-34a Are Potential Minimally Invasive Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2016;45(1):84–92. 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 161. Wu X, Xia M, Chen D, et al. : Profiling of downregulated blood-circulating miR-150-5p as a novel tumor marker for cholangiocarcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(11):15019–29. 10.1007/s13277-016-5313-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation