Abstract

Background:

About half of the cases of infertility in couples have been attributed to male factor. Despite the claim in folklore medicine that trona (a sesquicarbonate or hydrated carbonate of sodium) causes fetal loss, its effect on male reproductive function has not been investigated.

Aim:

This study sought to provide scientific evidence on the effect of trona on sperm characteristics, male reproductive hormones and organs, and lipid peroxidation.

Materials and Methods:

Forty male Wistar rats of comparable weights were used for the study. Rats were randomized into four different groups. The control received 1 mL of distilled water orally, whereas those in groups 1, 2, and 3 (test groups) received orally, same volume of trona preparation corresponding to 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg body weight, respectively, for 28 days. Body weight was monitored throughout the study period, and at the end of the experiment, testicular morphometry, sperm characteristic, reproductive hormones, and malondialdehyde (MDA), an index of lipid peroxidation, were determined.

Results:

Sperm count, motility, progressibility, and percentage of normal sperm were significantly decreased in the trona-treated rats (P < 0.05). The percentage of abnormal sperm, luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, and MDA were significantly increased in the treated rats (P < 0.05). Body weight, testicular morphometry, and testosterone level were comparable across all groups (P > 0.05).

Conclusion:

The study showed that trona has a dose-dependent deleterious effect on sperm characteristic. The antispermatogenic effect of trona was associated with lipid peroxidation but not testosterone.

KEYWORDS: Infertility, lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress, sperm, testosterone, trona

INTRODUCTION

Infertility is a major health challenge with social implications among couples of child-bearing age, especially in the tropics where adoption has not fully gained ground. Unlike the common belief in this area that infertility is attributable to female factor, it has been documented that 50% of primary infertility is due to male factor.[1,2] The common causes of male infertility include but are not limited to genetic disorders, endocrine abnormalities, immunological disorders and sperm antibodies, disorders of testes, obstruction of the reproductive tract, some systemic disorders, and inflammatory conditions.[3] Some drugs and chemicals have also been documented to cause deleterious effects on male reproductive function.[3,4]

Trona, a sesquicarbonate or hydrated carbonate of sodium,[5] is believed to have some effect on the reproductive function. Trona is commonly used as food preservative, food flavor, as a drawing effect in some local soups, and food tenderizer.[6] It is popularly called kaun or Kanwa. It has also been reported to play beneficial roles in the management of cough, toothache, stomach pains, and constipation.[6]

Trona is locally used for fertility control among women. Its reproductive potential has been associated with its contractile effect on the uterus.[7] Despite its common use in fertility control among women, there is no scientific documentation to evaluate its effect on male reproduction. This study thus evaluates the effect of trona on male reproductive function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Laboratory animals

Forty healthy male Wistar rats of comparable weights and ages (10 weeks ±2) were obtained from the Animal House Department of the institution. The rats were housed in clean, stainless steel cages placed in well-ventilated room conditions (temperature: 28–31°C, 12 h light–dark cycle, humidity of 45–50%). They fed on pellets and water ad libitum. The animals were allowed to acclimatize for 2 weeks. This study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the institution, which is a modified form of National Institute of Health on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animal.[8]

Rats were randomized into four different groups. The control received 1 mL of distilled water orally, whereas those in groups 1, 2, and 3 (test groups) received orally same volume of trona preparation corresponding to 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg body weight, respectively, for 28 days. Body weight was monitored throughout the study period, and at the end of the experiment, testicular morphometry, sperm characteristic, reproductive hormones, and malondialdehyde (MDA), an index of lipid peroxidation, were determined.

Preparation of trona solution

Trona was grounded with mortar and pestle, and sieved. Sample specimens was taken to the laboratory of Food Science and Engineering of the institution for extraction using lime and stored in a bottle under room temperature until used. An amount of 200 g of trona was dissolved in 1 L of lime to give a concentration of 200 mg/mL. The solution was reconstituted to give the required doses of 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg body weight. The method of preparation and doses used in the study are as documented in a previous study.[9]

Hormones assay

Standard-assay kits for hormonal assay were used to determine the testosterone, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels. The hormones were assayed in the serum of the animals following the procedure outlined in the manufacturers’ instruction manual as described for testosterone, and LH, and FSH.

Determination of body weight and testicular morphometry

The body weights of the experimental animals were determined and recorded every week throughout the experimental period. After the experimental period, animals were sacrificed and the testes were harvested to determine the testicular weight, length, and width.

Semen analysis

Semen analysis was done as previously documented.[10] The testes were removed along with the epididymis. The caudal epididymis was separated from the testis and lacerated to collect semen onto the microscope slide.[11] Sperm characteristic was evaluated as described by Woode et al. using 2.9% sodium citrate as buffer and 10 mL phosphate buffer saline for sperm motility and count, respectively.[12] Briefly, sperm motility was examined under the microscope, and sperm count was carried out using the improved Neubauer Hemocytometer and calculated. Sperm morphology was done using two drops of Walls and Ewas stain, and air-dried and examined under the microscope. The normal sperm cells were counted and the percentage calculated.

Sperm viability was evaluated using the Eosin–Nigrosin stain technique. A amount of two drops of the stain was mixed with semen. A thick smear was prepared, air-dried, and examined under microscope. Live/viable sperm cells were unstained, whereas dead/nonviable sperm cells appeared stained. The live and dead sperm were counted and the percentage of each calculated.

Statistical analysis

The mean of six replicates ± standard error of mean was calculated for all values.[17] Comparison between the control and experimental groups were done using the student t test. Comparisons across all groups were done using analysis of variance. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. All analyses were done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences.

RESULTS

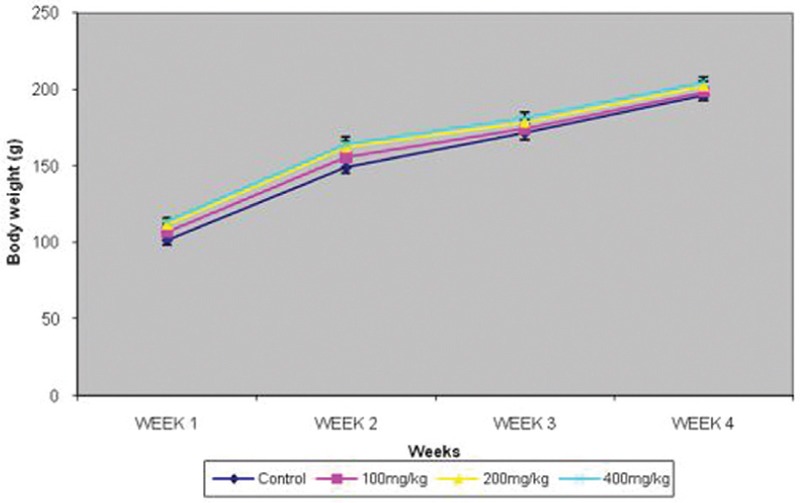

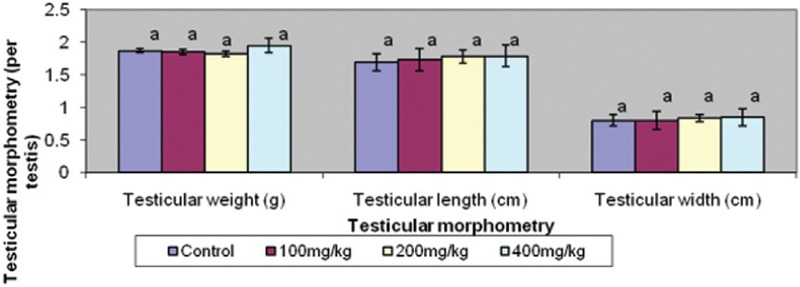

Body weight changes and testicular morphometry were comparable in all groups [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Effect of graded doses of trona on body weight. FNx01P<0.05 vs others

Figure 2.

Effect of graded doses of trona on testicular morphometry. Bars carrying same letters, a, as controls on each variable are statistically not different at P<0.05

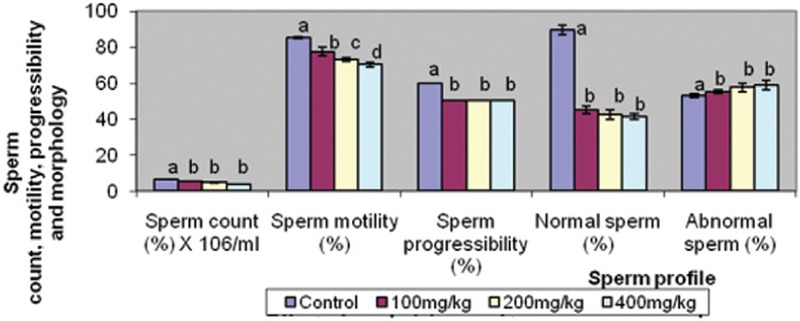

Figure 3 shows that the sperm count, sperm progressibility, and normal sperm were reduced in the treated groups when compared with the control; however, these indices were comparable in all the treated groups. On the other hand, abnormal sperm were increased in the treated groups. Sperm motility was decreased in the treated groups in a dose-dependent pattern.

Figure 3.

Effect of graded doses of trona on semen analysis. Bars carrying same letters, a, as controls on each variable are statistically not different at P<0.05

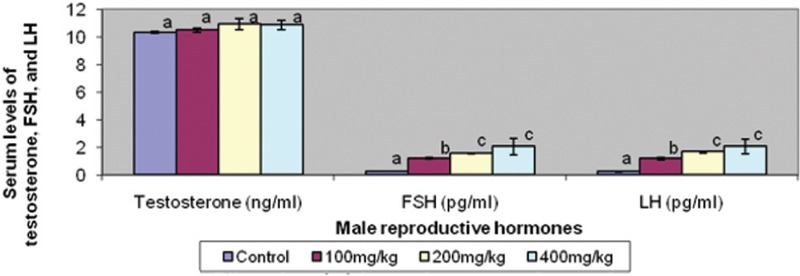

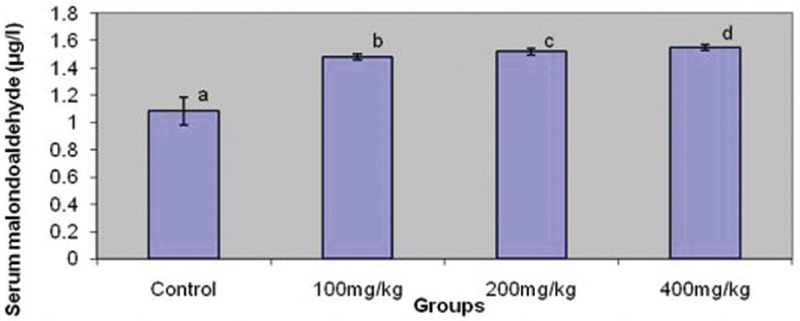

Serum testosterone level was similar in the treated groups and control. However, serum FSH and LH levels were raised in a dose-dependent pattern in the treated groups [Figure 4]. Similarly, serum MDA was raised in the same pattern across the treated groups [Figure 5].

Figure 4.

Effect of graded doses of trona on male reproductive hormones. Bars carrying same letters, a, as controls on each variable are statistically not different at P<0.05

Figure 5.

Effect ofgraded dosesof tronaonmalondialdehyde(MDA). Bars carrying same letters, a, as control are statistically not different at P<0.05

DISCUSSION

Despite the social implications of infertility which is a major problem among couples, it remains a neglected reproductive health issues. This is probably due to its nonlethal effect. Anecdotal evidence also shows that when concerns are raised about infertility, male factor which accounts for half of the causes is yet neglected. This could be associated with male chauvinism. Many environmental and biochemical factors are involved in male and female reproduction.[13] Factors that play a role in fertility control certainly cause infertility in couples who require conception. The effect of trona, which is commonly used for fertility control in women, on male reproduction, has not been scientifically documented. A better understanding of the effects and associated mechanism of trona on male reproduction would be necessary to improve infertility management.

Findings from this study clearly showed that trona did not have any deleterious effect on testicular morphometry and body weight. However, it led to a significant reduction in sperm count, motility, progressibility, and percentage of the normal sperm. These changes were comparable in all treated groups except sperm motility which reduced dose-dependently.

The endocrine system is an integral part of the normal functioning of the reproductive system. This involves the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis.[14] The hypothalamus produces LH-releasing hormone which stimulates the production of gonadotropins, LH, and FSH from the pituitary gland.[14,15] In males, LH stimulates the interstitial cells of the leydig to produce testosterone, whereas FSH stimulates sperm maturation in the epididymis.[14,15,16] In a normal functioning system, a low testosterone would cause a rise in gonadotropins.[15] Astonishingly, serum levels of FSH and LH increased with trona treatment, but testosterone remained comparable with the control group. However, MDA, an index of lipid peroxidation, rised with trona treatment. This infers that antifertility effect of trona is not associated with testosterone level but with lipid peroxidation.

It has been well documented that lipid peroxidation play a role in infertility either by causing testicular damage, impairing spermatogenesis, or causing direct damage to the sperm cells.[10,15,16,17] Although trona did not cause a significant damage on testicular morphometry, its deleterious effect on sperm characteristics might be explained by the trona-induced lipid peroxidation. This is in consonance with previous documentation that lipid peroxidation causes oxidative injury to the fatty acid-rich testicular membrane.[10,15,16,17,18] Lipid peroxidation has also been reported to cause germ cell death.[15,16] This finding also complements the report of Ajiboye et al. that documented that trona exhibited its toxic effect by depleting the antioxidant systems and increasing the risk of generated oxidants attack.[9]

Alawa et al. reported the isolated chemical constituents of trona as high amounts of sodium and calcium ions and low iron, potassium, magnesium, zinc, manganese, carbonates, sulphate, bicarbonates, and chloride ions.[7] The potential of trona to cause lipid peroxidation and consequent poor sperm quality might be attributed to its chemical constituents.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that trona has a dose-dependent deleterious effect on sperm characteristic. The antispermatogenic effect of trona was associated with lipid peroxidation but not testosterone.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yales CA, Thomas C, Kovacs GT, De Krester DM. Androgen, male factor, infertilityand IVF. In: Wood C, Trouson A, editors. Clinical In Vitro Fertilization. USA: Springer-Verlag; 1989. pp. 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeşilli C, Mungan G, Seçkiner I, Akduman B, Açikgöz S, Altan K. Effect of varicocelectomy on sperm creatine kinase, HspA2 chaperone protein (creatine kinase-M type), LDH, LDH-X, and lipid peroxidation product levels in infertile men with varicocele. Urology. 2005;66:610–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badoe EA, Archampong EQ, da Rocha-Afodu JT. Principles and Practice of Surgery, including the pathology in the tropics. 3rd ed. Ghana: Ghana Publishing Corporation; Male infertility; pp. 898–907. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonde JP. Male fertility. In: Comhaire FM, editor. Chapman and Hall Medicals. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1996. pp. 266–84. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sodipo OA. How safe is the consumption of trona? Am J Public Health. 1993;83:118. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.8.1181-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makanjuola AA, Beetlestone J. G. Some chemical and mineralogical notes on ‘kaun’. J Min Geol. 1975;10:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alawa CBI, Adamu AM, Ehoche OW, Lamidi OS, Oni OO. Performance of Bunaji Bulls fed maize stover supplemented with urea and local mineral lick (Kanwa) J Agric Environ. 2000;1:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 8.NIH Publication No. 83-127. Washington, DC, USA: National Research Council; 1985. National Institute of Health (NIH). Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ajiboye TO, Komolafe YO, Yakubu MT, Ogunbode SM. Effects of trona on the redox status of cellular system of male rats. Toxicol Ind Health. 2015;31:179–87. doi: 10.1177/0748233712469654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ajayi AF, Akhigbe RE. Antifertility activity of Cryptolepis sanguinolenta leaf ethanolic extract in male rats. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2012;5:43–7. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.97799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa LG, Hodgson E, Lawrence DA, Reed DJ. Current Protocol in Toxicology. United States: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woode E, Alhassan A, Chrissie S. Abaidoo. Effect of ethanolic fruit extract of Xylopia aethiopica on reproductive function of male rats. Int J Pharm Biomed Res. 2011;2:161–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosher WD, Pratt WF. Fecundity and infertility in the United States: incidence and trends. J Fertil Steril. 1991;56:192–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajayi AF, Akhigbe RE, Ajayi LO. Hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis in thyroid dysfunction. West Indian Med J. 2013;62:835–8. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2013.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emanuele M, Emanuele N. Alcohol and the male reproductive system. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:282–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ige SF, Akhigbe RE. The role of Allium cepa on aluminium-induced reproductive dysfunction in experimental male rat models. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2012;5:200–5. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.101022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ige SF, Olaleye SB, Akhigbe RE, Akanbi TA, Oyekunle OA, Udoh US. Testicular toxicity and sperm quality following cadmium exposure in rats: ameliorative potentials of Allium cepa. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2012;5:37–42. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.97798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sies H. Oxidative stress: oxidants and antioxidants. Exp Physiol. 1997;82:291–5. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]