Abstract

Objectives To provide direct estimates of risk of cancer after protracted low doses of ionising radiation and to strengthen the scientific basis of radiation protection standards for environmental, occupational, and medical diagnostic exposures.

Design Multinational retrospective cohort study of cancer mortality.

Setting Cohorts of workers in the nuclear industry in 15 countries.

Participants 407 391 workers individually monitored for external radiation with a total follow-up of 5.2 million person years.

Main outcome measurements Estimates of excess relative risks per sievert (Sv) of radiation dose for mortality from cancers other than leukaemia and from leukaemia excluding chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, the main causes of death considered by radiation protection authorities.

Results The excess relative risk for cancers other than leukaemia was 0.97 per Sv, 95% confidence interval 0.14 to 1.97. Analyses of causes of death related or unrelated to smoking indicate that, although confounding by smoking may be present, it is unlikely to explain all of this increased risk. The excess relative risk for leukaemia excluding chronic lymphocytic leukaemia was 1.93 per Sv (< 0 to 8.47). On the basis of these estimates, 1-2% of deaths from cancer among workers in this cohort may be attributable to radiation.

Conclusions These estimates, from the largest study of nuclear workers ever conducted, are higher than, but statistically compatible with, the risk estimates used for current radiation protection standards. The results suggest that there is a small excess risk of cancer, even at the low doses and dose rates typically received by nuclear workers in this study.

Introduction

Ionising radiation is one of the most studied and ubiquitous carcinogens in our environment. The main basis for radiation protection recommendations is the study of survivors of the Japanese atomic bomb (A bomb), a population exposed primarily at high dose rates.1-3 The primary public health concern, however, is the protection of people from relatively low dose, protracted or fractionated exposures such as those received by the public in the general environment, by patients through repeated diagnostic procedures,4 and by radiation workers.

The effects of low dose chronic exposure to external radiation have been directly estimated in several cohorts of workers in the nuclear industry,3 but the sample size has limited the precision of these estimates. Analyses of combined cohorts have improved precision.5-7 Estimates from these analyses, however, are compatible with a range of possibilities, from a reduction of risk at low doses to risks higher than those underlying current radiation protection recommendations.

The 15 country study, an international collaborative study of cancer risk among radiation workers in the nuclear industry, was carried out to further improve the precision of direct estimates of risk after protracted low dose exposures and to strengthen the scientific basis of radiation protection.1 We present risk estimates for mortality from all cancers, excluding leukaemia, and from leukaemia excluding chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and compare them with estimates derived from data on survivors of the A bomb. We have used the term nuclear industry to refer to facilities engaged in production of nuclear power, manufacture of nuclear weapons, enrichment and processing of nuclear fuel, production of radioisotopes, or reactor or weapons research. Uranium mining is not included.

Methods

This multinational retrospective cohort study used a common protocol in 15 countries and collected information on nearly 600 000 workers. Study cohorts were defined from employment or dosimetric records of participating facilities or, where available, from centralised national dose registries. The a priori eligibility criteria for inclusion of cohorts8 were essentially complete and non-selective follow-up for mortality; availability of individual annual recorded estimates of dose for all monitored workers; and availability of information on historical monitoring policies and practices. We included all workers who had been monitored for external photon (x and γ) radiation exposure through the use of personal dosimeters. Details of country specific methods are described elsewhere.9

Ascertainment of vital status and cause of death

We established vital status through linkage with national or regional death registries. In a few countries where this was not possible, appropriate records of local authorities were used. Completeness of follow-up ranged from 87% to nearly 100%. Vital statistics registries provided cause of death, which was known for over 90% of workers who died.

Adequacy of dosimetric records

We reconstructed each worker's dosimetric history using recorded doses from individual facilities or national dose registries. A study of errors in recorded doses evaluated the comparability of dose estimates across facilities and time and identified and quantified sources of bias and uncertainties.9 Doses from higher energy photons (100-3000 keV), which constituted most of the dose in most cohorts, were judged to have been measured in a comparable way over time and across facilities.9,10 The adequacy of practices and technology to measure and record dose from other radiation types (neutrons, internal exposures), however, varied substantially, particularly in earlier years. We therefore excluded workers with potential for substantial doses (≥ 10% of their whole body dose) from these radiation types.

Main study population

The main study population was defined as workers who had been employed in one or more facilities for at least one year (113 711 workers excluded), who had been monitored for external radiation exposure (38 521 workers excluded), and whose doses resulted predominantly from higher energy photon radiation (39 730 workers with internal contamination and 19 041 with neutron exposures excluded).

Dosimetric errors and derivation of organ doses

The major sources of errors in higher energy photon doses were dosimetry technology, exposure conditions, and calibration practices. Errors from these sources were quantified and bias factors specific to the doses to each organ of interest calculated for each model of dosimeter used and by type of facility (nuclear power plants and mixed activities facilities).11,12 Organ doses were derived by dividing recorded doses by the appropriate organ dose bias factor. We used doses to the colon and active bone marrow for analyses of mortality from all cancers excluding leukaemia and from leukaemia, respectively. All doses are expressed as dose equivalents in sieverts (Sv).

Statistical methods

Analyses were based on a linear relative risk Poisson regression model, in which the relative risk is of the form 1+βZ, where Z is the cumulative dose equivalent in Sv and β is the excess relative risk per Sv; 95% likelihood based confidence intervals were calculated. We used 11 a priori categories of dose (< 5, 5- < 10, 10- < 20, 20- < 50, 50- < 100, 100- < 150, 150- < 200, 200- < 300, 300- < 400, 400- < 500, ≥ 500 mSv). Analyses used only underlying cause of death. Estimates of excess relative risk were stratified for sex, age, and calendar period (both in five year categories), facility, duration of employment (< 10 years, ≥ 10 years), and socioeconomic status. In the analyses of all cancers we excluded cohorts for which socioeconomic information was unavailable or incomplete (Japan, Idaho National Engineering Laboratory (INEL), Ontario Hydro Canada), but we included them in analyses of leukaemia as the potential for confounding by socioeconomic status was thought to be less for leukaemia. To allow for a latent period between exposure and death, doses were lagged by two years for leukaemia and 10 years for other cancers, as in other studies of nuclear workers5-7 and assessments of radiation risk.1,2 Sensitivity analyses were conducted with a range of different lags. Attributable risks were estimated by multiplying the excess relative risks by the average dose in the cohort.

We have focused on the main causes of death for which radiation protection committees have provided risk estimates: all cancers excluding leukaemia and leukaemia excluding chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia is excluded because it is thought to be less readily inducible by ionising radiation than other leukaemias.3 We have also presented risk estimates for solid cancers (that is, excluding lymphatic and haematopoietic malignancies) to compare with recent data for A bomb survivors13 and for all cancers excluding leukaemia, lung, and pleural cancers (which have the greatest potential for confounding by smoking, internally incorporated radionuclides, and other occupational carcinogens). We investigated confounding by smoking by separately analysing solid cancers related or unrelated to smoking and two groupings of smoking related outcomes other than cancer (all non-malignant respiratory diseases and chronic obstructive bronchitis and emphysema).

Analysis of data from survivors of A bomb

We analysed mortality data from the A bomb survivors for solid cancer to 199713 and leukaemia to 199014 using similar methods to provide risk estimates for comparison. Analyses were stratified for attained age, city, and calendar time and restricted to men aged 20-60 at exposure, the group most comparable to the workers.

Results

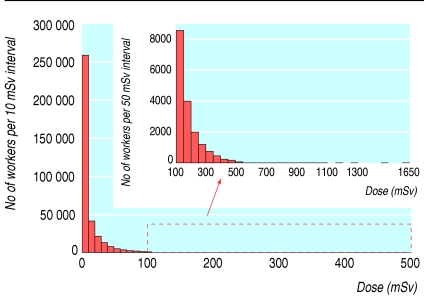

Overall, 598 068 workers were employed in at least one of 154 facilities. Most facilities were involved in nuclear power production; the rest specialised in different activities, including research, waste management, and production of fuel, isotopes, and weapons. The main study population comprised 407 391 workers (table 1). A total of 24 158 (5.9%) people were known to have died during the study period: 6519 from cancers other than leukaemia and 196 from leukaemia excluding chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. The total duration of follow-up was 5 192 710 person years and the total collective recorded dose was 7892 Sv. Most workers in the study were men (90%), and men received 98% of the collective dose. The overall average cumulative recorded dose was 19.4 mSv. The distribution of recorded doses was skewed (fig 1). Ninety per cent of workers received cumulative doses < 50 mSv and less than 0.1% received cumulative doses > 500 mSv.

Table 1.

Cohorts included in the 15 country study

|

Deaths

|

Average individual cumulative dose (mSv)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of facilities | First year of operations | Follow-up period | No of workers | Person years | All causes | All cancers excluding leukaemia | Leukaemia excluding CLL | Collective cumulative dose (Sv) | ||

| Australia | 1 | 1959 | 1972-98 | 877 | 12 110 | 56 | 17 | 0 | 5.4 | 6.1 |

| Belgium | 5 | 1953 | 1969-94 | 5 037 | 77 246 | 322 | 87 | 3 | 134.2 | 26.6 |

| Canada | 4 | 1944 | 1956-94 | 38 736 | 473 880 | 1 204 | 400 | 11 | 754.3 | 19.5 |

| Finland | 3 | 1960 | 1971-97 | 6 782 | 90 517 | 317 | 33 | 0 | 53.2 | 7.8 |

| France CEA-COGEMA | 9 | 1946 | 1968-94 | 14 796 | 224 370 | 645 | 218 | 7 | 55.6 | 3.8 |

| France EDF | 22 | 1956 | 1968-94 | 21 510 | 241 391 | 371 | 113 | 4 | 340.2 | 15.8 |

| Hungary | 1 | 1982 | 1985-98 | 3 322 | 40 557 | 104 | 39 | 1 | 17.0 | 5.1 |

| Japan | 33 * | 1957 | 1986-92 | 83 740 | 385 521 | 1 091 | 413 | 19 | 1526.7 | 18.2 |

| Korea (south) | 4 | 1977 | 1992-97 | 7 892 | 36 227 | 58 | 21 | 0 | 122.3 | 15.5 |

| Lithuania | 1 | 1984 | 1984-2000 | 4 429 | 38 458 | 102 | 24 | 1 | 180.2 | 40.7 |

| Slovak Republic | 1 | 1973 | 1973-93 | 1 590 | 15 997 | 35 | 10 | 0 | 29.9 | 18.8 |

| Spain | 10 | 1968 | 1970-96 | 3 633 | 46 358 | 68 | 25 | 0 | 92.7 | 25.5 |

| Sweden | 6 | 1954 | 1954-96 | 16 347 | 220 501 | 669 | 190 | 4 | 291.8 | 17.9 |

| Switzerland | 4 | 1957 | 1969-95 | 1 785 | 22 051 | 66 | 24 | 0 | 111.2 | 62.3 |

| UK | 32 | 1946 | 1955-92 | 87 322 | 1 370 101 | 7 983 | 2201 | 54 | 1810.1 | 20.7 |

| US Hanford | 1 | 1944 | 1944-86 | 29 332 | 678 833 | 5 564 | 1279 | 35 | 695.4 | 23.7 |

| US INEL | 1 | 1949 | 1960-96 | 25 570 | 505 236 | 3 491 | 886 | 26 | 254.6 | 10.0 |

| US NPP | 15 | 1960 | 1979-97 | 49 346 | 576 682 | 983 | 314 | 19 | 1336.0 | 27.1 |

| US ORNL | 1 | 1943 | 1943-84 | 5 345 | 136 673 | 1 029 | 225 | 12 | 81.1 | 15.2 |

| Total | 154 | — | — | 407 391 | 5 192 710 | 24 158 | 6519 | 196 | 7892.0 | 19.4 |

CEA-COGEMA=Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique-Compagnie Générale des Matières Nucléaires; EDF=Electricité de France; NPP=nuclear power plants; INEL=Idaho National Engineering Laboratory; ORNL=Oak Ridge National Laboratory; CLL=chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.

No information available to allow separation of different facilities.

Fig 1.

Distribution of cumulative radiation doses among workers included in the analyses

For all cancers excluding leukaemia, the excess relative risk was 0.97 per Sv and was significantly different from zero (95% confidence interval 0.14 to 1.97) (table 2). This estimate corresponds to a relative risk of 1.10 for a radiation dose of 100 mSv. For solid cancers, the excess relative risk was 0.87 (0.03 to 1.88), higher than but statistically compatible with the estimate for A bomb survivors (0.32 per Sv). The excess relative risk for leukaemia excluding chronic lymphocytic leukaemia was 1.93 per Sv (< 0 to 8.47), which gives a relative risk of 1.19 for a dose of 100 mSv. This estimate is between the linear and linear quadratic extrapolations from data on A bomb survivors (table 2).

Table 2.

Estimates of excess relative risk per Sv (95% confidence interval) for all cancers excluding leukaemia, solid cancers, and leukaemia excluding chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, for nuclear workers and survivors of A bomb in Japan *

|

15 country study

|

Atomic bomb survivors (men exposed at age 20-60)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of cancers | Risk | No of cancers | Risk† | |

| All cancers excluding leukaemia | 5024 | 0.97 (0.14 to 1.97) | ||

| Solid cancers | 4770 | 0.87 (0.03 to 1.88) | 3246 | 0.32 ‡ (0.01 to 0.50) |

| Leukaemia excluding CLL: | ||||

| Linear model | 196 | 1.93 (<0 § to 8.47) | 83 | 3.15 ¶ (1.58 to 5.67) |

| Linear quadratic model | 1.54 ** (−1.14 to 5.33) | |||

CLL=chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.

Colon dose used for all cancers and solid cancer analyses, bone marrow dose for leukaemia.

Note that because analyses were restricted to men aged 20-60 at exposure the confidence intervals are much wider than those presented by other investigators13,14 and are based on the full cohort.

Analyses carried out at IARC with excess relative risk model that allows for age at exposure modification, adjusted for attained age, calendar period, and city. Estimate for men exposed at age 35.

Estimate on boundary of parameter space.

Analyses carried out at IARC with constant excess relative risk model, adjusted for attained age, calendar period, and city.

Analyses carried out at IARC—linear term of linear quadratic model—preferred model for describing leukaemia mortality in analyses of data on A bomb survivors.14

Table 3 assesses the possible confounding effect of smoking. Excess relative risks ranged between 0.59 per Sv (-0.29 to 1.70) for all cancers excluding leukaemia and lung and pleural cancer, and 0.91 per Sv (-0.11 to 2.21) for smoking related cancers.

Table 3.

Estimates of excess relative risk per Sv (95% confidence intervals) for specific causes of death

| Cause of death* | No of deaths | Risk |

|---|---|---|

| All cancers excluding leukaemia | 5024 | 0.97 (0.14 to 1.97) |

| All cancers excluding leukaemia, lung and pleural cancers | 3528 | 0.59 (−0.29 to 1.70) |

| Solid cancers | 4770 | 0.87 (0.03 to 1.88) |

| Smoking related solid cancers † | 2737 | 0.91 (−0.11 to 2.21) |

| Solid cancers unrelated to smoking | 2033 | 0.62 (−0.51 to 2.20) |

Colon dose used for all cancers excluding leukaemia; all cancers excluding leukaemia, lung and pleural cancers; solid cancers; and solid cancers unrelated to smoking. Lung dose used for smoking related solid cancers.

Those cancers identified as having sufficient evidence for being caused by smoking in recent IARC monograph15: cancers of lung, oral cavity, nasopharynx, oropharynx, and hypopharynx, nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, larynx, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, liver, kidney (body and pelvis), ureter, urinary bladder, and uterine cervix. Category of cancers unrelated to smoking comprised all other solid cancers.

The increased risk for smoking related cancers was mainly due to an increased risk of lung cancer (1.86 per Sv, 0.26 to 4.01). Other smoking related cancers showed little evidence of an increased risk (0.21 per Sv, < 0 to 2.01). Risk estimates for mortality from non-malignant respiratory diseases and from chronic obstructive bronchitis and emphysema were raised but not significantly different from zero (excess relative risk per Sv 1.16, -0.53 to 3.84, and 2.12, -0.57 to 7.46, respectively).

Discussion

Results from our study show that an excess risk of cancer exists, albeit small, even at the low doses and dose rates typically received by nuclear workers in this study. The 15 country study allowed the compilation of the largest body of direct evidence to date concerning the effects of low dose chronic exposure to ionising radiation. Our risk estimates mainly reflect risks in men, as there were few exposed women in the cohort.

Dosimetric measurement errors

Reliable estimates of dose were systematically available only for external exposure to higher energy photons so our results are restricted to workers exposed mainly to these radiation types. A detailed study of historical practices and technology allowed us to identify and quantify the major sources of errors. Analyses were based on organ dose estimates, which we adjusted to account for the main sources of systematic errors.

All cancer excluding leukaemia

We found a significantly increased risk for all cancers (excluding leukaemia). The central risk estimate was higher than the linear extrapolation from the A bomb survivors. It is unlikely that this could be due to ascertainment bias, with physicians being more likely to list cancer as the underlying cause of death for workers with higher exposures, as the excess relative risk for all non-cancer mortality was weakly positive (0.20, -0.26 to 0.72).

We could not adjust directly for possible confounding by variables such as smoking, diet, and occupational exposures as information was not available. Some of these factors—particularly smoking16 and diet—are strongly related to socioeconomic status and adjustment for this will have partially controlled for their effects. Factors such as smoking can confound the association between radiation dose and risk only if they are related both to risk of cancer and to dose. Some cohort studies have found an association between radiation dose and smoking,17,18 while others have not.19-21

Although the estimated risk for mortality from lung cancer was particularly high, mortality from smoking related cancers other than lung cancer showed little evidence of a relation with dose. Indeed, the central risk estimate for cancers unrelated to smoking was higher than that for smoking related cancers other than lung caner, indicating that confounding by smoking is unlikely to explain all of the relation found between all cancer risk and radiation dose. On the other hand, the non-significantly increased risks for mortality from non-malignant smoking related diseases indicate a possible effect of smoking. The risk estimates for mortality from all groups of cancers related and unrelated to smoking, however, are consistently two to three times higher than, but statistically compatible with, the risk estimate for solid cancers from the A bomb analyses (table 3). Taken together, these findings indicate that a confounding effect by smoking may be partly, but not entirely, responsible for the estimated increased risk for mortality from all cancers other than leukaemia.

The findings for all cancers excluding leukaemia were not greatly influenced by data from any one country: formal tests for heterogeneity provided no evidence for differences in risk between countries, cohorts, or groups of facilities (P > 0.20). Figure 2 shows the excess relative risk per Sv in the larger cohorts (> 100 cancer deaths); the risk estimate for Canada is the largest. Analyses excluding one cohort or country at a time produced excess relative risks per Sv ranging from 0.58 (excluding Canada) to 1.25 (excluding the UK), all consistently higher than, but compatible with, the estimate from A bomb analyses. Only when we excluded Canada was the excess relative risk no longer significantly different from zero (0.58, -0.22 to 1.55).

Fig 2.

Excess relative risks per Sv for all cancer excluding leukaemia in cohorts with more than 100 deaths (NPP=nuclear power plants, ORNL=Oak Ridge National Laboratory)

Sensitivity analyses of different lag periods showed that both the risk estimates and their uncertainties increased with increasing lag. The excess relative risk per Sv ranges from 0.76 (0.07 to 1.59) with a lag of five years to 1.68 (0.22 to 3.48) with a lag of 20 years. The estimates are all statistically compatible with the linear extrapolation from the A bomb survivors.

Leukaemia excluding chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

Although our estimate of risk of leukaemia is not significantly different from zero, it is similar to estimates from previous large scale studies of nuclear workers.5,7 Furthermore, it is intermediate between estimates obtained by fitting a linear and a linear quadratic dose-response model to data on men exposed to the A bomb at age 20-60. The excess relative risk per Sv shows only a small increase with increasing lag periods, from 1.93 (< 0 to 8.47) with a lag of two years to 2.53 (< 0 to 10.45) with a lag of 10 years.

The preferred model for the A bomb data includes an effect of time since exposure.14 Patterns of risk of cancer after low dose protracted exposures are, however, not necessarily the same as those observed in A bomb studies. Indeed, the data for nuclear workers did not show evidence of a time since exposure effect (not shown).

Our results are not independent of previous combined analyses.5,7 Analyses excluding workers from these earlier cohorts, however, yielded similar conclusions.

Implications for radiation protection

The general practice in radiation protection is to estimate risks for protracted exposures to low doses by extrapolating from situations of acute exposure to high doses. For this, a linear dose response model with no threshold is assumed and risk estimates are divided by two to allow for the assumed reduced carcinogenicity of exposures received at low dose rates.2 For leukaemia, this is similar to using the linear term of a linear quadratic model. The central risk estimate for leukaemia from this study (and from previous studies of nuclear workers) would support this practice. The confidence interval is wide, however, and findings are also compatible with no reduction, as well as with greater reductions of risk at low doses.

For mortality from all cancers excluding leukaemia, the central risk estimates are two to three times higher than the linear extrapolation from the A bomb survivors. The confidence intervals are wide, however, and findings are statistically compatible with the current bases for radiation protection standards.

Current recommendations form the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) are to limit occupationaldoses to 100 mSv over five years (not to exceed 50 mSv in any one year) and doses to the public to 1 mSv per year.2 Our estimates suggest that a cumulative exposure of 100 mSv would lead to a 9.7% (1.4 to 19.7%) increased mortality from all cancers excluding leukaemia and a 5.9% (-2.9 to 17.0%) increased mortality from all cancers excluding leukaemia, lung, and pleura compared with background rates. The corresponding figure is 19% (< 0 to 84.7%) for mortality from leukaemia excluding chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Less than 5% of workers in this study received cumulative doses of the order of 100 mSv over their entire career, however, and most of these doses were received in the early years of the nuclear industry, when protection standards were less stringent than today. Overall, on the basis of our central risk estimates, we estimate that 1-2% of deaths from cancer (including leukaemia) among workers in this cohort may be attributable to radiation.

What is already known on this topic

Current radiation protection standards are based mainly on data from the survivors of the atomic bomb in Japan

The estimation of risks after low dose protracted or fractionated exposures to ionising radiation is controversial

What this study adds

A small excess risk of cancer exists, even at the low doses typically received by nuclear industry workers in this study

Conclusions

We have provided radiation risk estimates from the largest study of nuclear industry workers conducted so far. These estimates are higher than, but statistically compatible with, the current bases for radiation protection standards. The confidence intervals range from values lower than those derived by linear extrapolation from data from A bomb survivors up to values that exceed this extrapolation by a factor of six for cancers other than leukaemia and nearly three for leukaemia. These results suggest that an excess risk of cancer exists, albeit small, even at the low doses and dose rates typically received by nuclear workers in this study.

We are grateful to Richard Doll, Jacques Estève, and Bruce Armstrong who helped to start this study; to the late Len Salmon who inspired the study of errors in doses; to past members of the dosimetry and epidemiology subcommittees (William Murray, Robert Rinsky) and of the international study group (the late E Gubéran, Y Hosoda, T Iwasaki, G Kendall, M Murata, T Rytomaa); to everyone in the participating countries who worked in the collection and validation of the data used in the study; and to the representatives and staff of the nuclear facilities included in the study for their open collaboration. This report uses data obtained from the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. RERF is a private, non-profit foundation funded by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and the US Department of Energy through the National Academy of Sciences. The conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the scientific judgment of RERF or its funding agencies.

Contributors: ECa designed and coordinated the international study, took part in data analysis, interpretation, and writing of the paper, and is guarantor. MV took part in data analysis, interpretation, and writing of the paper for the international study. As members of the epidemiology subcommittee MB, EG, MH, CHi, GH, JKa, CM, MS-B, and TY contributed to the conception and design, the development of the analytical strategy, and the analysis and interpretation of the data of the international study. They also contributed to the collection and validation of data in their own countries. As members of the dosimetry subcommittee FB, GC, JJF, CHa, BH, MMarshall, IT-C, and DU developed the protocol for the study of errors in doses, collected data on dosimetry practices, and participated in the review and analysis of dosimetry questionnaires and in the identification and quantification of errors in photon dose estimates. The study of errors in doses was the topic of IT-C's PhD dissertation and postdoctoral fellowship, and she was involved in all of the steps of data acquisition, validation, and analysis and in the planning and conducting of the dosimetry experiments and the derivation of the dosimetric bias conversion factors. The other members of the international study group (YOA, PA, AA, JMB, JBS, AB, PD, ADS, ME, HE, GE, LMG, GG, RH, KH, HH, AK, JKu, HM, AMa, IT, MU) took part in the design of the common protocol and were responsible for implementation of the core protocol and the collection and validation of data in their countries. FR-A, AR, MT-L, and KV coordinated data collection or otherwise contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data at the national level in their countries. EA, ECo, AMo, and HT were responsible for management of the international database and for data validation and analysis at IARC. MMartuzzi and DBR assisted in validation of the data at the international level, implementation of the protocol at the national level, and provided assistance to national collaborators through contacts and site visits. MSP assisted in the validation and analysis of the international dataset. All authors critically reviewed earlier drafts for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the paper.

Funding: European Union (contracts F13P-CT930066, F14P-CT96-0062, FIGH-CT1999-20001); US Centers for Disease Control (Co-operative agreement U50/CCU011778); Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission; Japanese Institute for Radiation Epidemiology, Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation; Nuclear Research Center (SCKCEN), Belgium; Health Canada and Statistics Canada; La Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer, France; La Compagnie Générale des Matière Nucléaire, France; Electricité de France; Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan; Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) in Korea; Spanish Nuclear Safety Council; US Department of Energy. These sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation. IT-C received funding from the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC, France); MSP and DBR were the recipients, respectively, of an IARC postdoctoral fellowship and of an ORAU fellowship during their stay at IARC.

Competing interests: C Hacker, B Heinmiller, H Hyvonen, M Marshall, A Rogel, J Bernar Solano, M Eklöf, and K Holan are (or have been in the past five years) employees of the nuclear industry or have links to the nuclear industry in their country. They were appointed to the international study group and or the dosimetry subcommittee as experts because of their critical knowledge and experience in historical radiation protection practices and dosimetry. None of them had influence on decisions concerning analysis of the results.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the IARC ethical review committee and by the relevant ethical committees of the participating countries.

References

- 1.BEIR V. Committee on the Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation. The effects on populations of exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, 1990.

- 2.International Commission on Radiological Protection ICRP. Recommendations of the international commission on radiological protection. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1991. (ICRP publication 60.)

- 3.United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR). Sources and effects of ionizing radiation. New York: United Nations, 2000.

- 4.Berrington de González A, Darby S. Risk of cancer from diagnostic X-rays: estimates for the UK and 14 other countries. Lancet 2004;363: 345-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.IARC Study Group on Cancer Risk among Nuclear Industry Workers. Direct estimates of cancer mortality due to low doses of ionising radiation: an international study. Lancet 1994;344: 1039-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardis E, Gilbert ES, Carpenter L, Howe G, Kato I, Armstrong BK, et al. Effects of low doses and low dose rates of external ionizing radiation: cancer mortality among nuclear industry workers in three countries. Radiat Res 1995;142: 117-32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muirhead CR, Goodill AA, Haylock RGE, Vokes J, Little MP, Jackson DA, et al. Occupational radiation exposure and mortality: second analysis of the national registry for radiation workers. J Radiol Prot 1999;19: 3-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardis E, Estève J. International collaborative study of cancer risk among nuclear industry workers. I—Report of the feasibility study. II—Protocol report 92/001. Lyons: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1992.

- 9.Cardis E, Martuzzi M, Amoros E. International collaborative study of cancer risk among nuclear industry workers. III—Procedures document, rev 1. Lyons: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1997. (97/002.)

- 10.Fix JJ, Salmon L, Cowper G, Cardis E. A retrospective evaluation of the dosimetry employed in an international combined epidemiological study. Radiat Protect Dosimetry 1997;74: 39-53. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thierry-Chef I, Pernicka F, Marshall M, Cardis E, Andreo P. Study of a selection of 10 historical types of dosemeter: variation of the response to Hp(10) with photon energy and geometry of exposure. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2002;102: 101-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thierry-Chef I, Cardis E, Ciampi A, Delacroix D, Marshall M, Amoros E, et al. A method to assess predominant energies of exposure in a nuclear research centre—Saclay (France). Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2001;94: 215-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preston DL, Shimizu Y, Pierce DA, Suyama A, Mabuchi K. Studies of mortality of atomic bomb survivors. Report 13: Solid cancer and noncancer disease mortality: 1950-1997. Radiat Res 2003;160: 381-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierce DA, Shimizu Y, Preston DL, Vaeth M, Mabuchi K. Studies of the mortality of atomic bomb survivors. Report 12, Part I. Cancer: 1950-1990. Radiat Res 1996;146: 1-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Vol 83. Tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. Lyons: IARC, 2004. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Lee DJ, LeBlanc W, Fleming LE, Gomez-Marin O, Pitman T. Trends in US smoking rates in occupational groups: the national health interview survey 1987-1994. J Occup Environ Med 2004;46: 538-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gribbin MA, Weeks JL, Howe GR. Cancer mortality (1956-1985) amongst male employees of Atomic Energy of Canada Limited with respect to occupational exposure to external low linear energy transfer ionizing radiation. Radiat Res 1993;133: 375-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murata M, Miyake T, Inoue Y, Ohshima S, Kudo S, Yoshimura T, et al. Life-style and other characteristics of radiation workers at nuclear facilities in Japan: base-line data of a questionnaire survey. J Epidemiol 2002;12: 310-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson G, Gilbert ES, Buchanan JA, Stevens RG. A case-cohort study of lung cancer ionizing radiation, and tobacco smoking among males at the Hanford sites. Health Phys 1990;58: 3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carpenter L, Fraser P, Booth M, Higgins C, Beral V. Smoking habits and radiation exposure. J Radiol Protection 1989;9: 286-7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auvinen A, Pukkala E, Hyvönen H, Hakama M, Rytömaa T. Cancer incidence among Finnish nuclear reactor workers. J Occup Environ Med 2002;44: 634-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]