Summary

We show how integrin αVβ6 binds a macromolecular ligand, pro-TGF-β1, in an orientation biologically relevant for force-dependent release of TGF-β from latency. The conformation of the prodomain integrin-binding motif differs in presence and absence of integrin binding; differences extend well outside the interface and illustrate how integrins can remodel extracellular matrix. Remodeled residues outside the interface stabilize the integrin-bound conformation, adopt a conformation similar to earlier evolving family members, and show how macromolecular components outside the binding motif contribute to integrin recognition. Regions in and outside the highly interdigitated interface stabilize a specific integrin-pro-TGF-β orientation that defines the pathway through these macromolecules that actin cytoskeleton-generated tensile force takes when applied through the integrin β-subunit. Simulations of force-dependent activation of TGF-β demonstrate evolutionary specializations for force application through the TGF-β prodomain and through the β and not α-subunit of the integrin.

Introduction

The transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) family is present in all metazoans and has expanded to 33 members in mammals1. TGF-βs sensu stricto (mammals have 3) are pivotal in development, wound healing, immune response, and tumorigenesis 2. Pro-TGF-β1 monomers contain an N-terminal 249-residue prodomain separated by a pro-protein convertase cleavage site from a C-terminal 112-residue growth factor (GF) domain. During biosynthesis, pro-TGF-β dimerizes and disulfide links to latent TGF-β binding proteins (LTBPs) or glycoprotein-A repetitions predominant protein (GARP) in large latent complexes (LLC) 3.

Although TGF-β in LLC is stored in large amounts in many tissues, and most cells have TGF-β receptors, TGF-β signaling requires integrin-applied force to release TGF-β from the embrace of its prodomain 3. The pro-TGF-β1 crystal structure revealed that each prodomain has an arm domain and straitjacket that form a ring around TGF-β and keep it latent 4. Binding of integrins αVβ6 and αVβ8 to RGDLXX(I/L) motifs in the arm domains of pro-TGF-β1 and 3 5 is required for TGF-β activation in vivo 6; however, integrin binding alone is not sufficient for GF release 4,6. Cell biological experiments suggest that traction force exerted by integrin αVβ6 on pro-TGF-β1 is required for activation, because activation is abolished by truncation of the β6-subunit cytoplasmic domain that links to the actin cytoskeleton or by deletions of disulfide links within LLC or its links to the extracellular environment required for tensile force exertion across the prodomain 6. In a wider context, how integrins bind and transmit force to macromolecular ligands is important for understanding the assembly and remodeling of extracellular matrices, for example, assembly of fibronectin into the extracellular matrix requires integrin α5β1 and traction force 7.

We have no atomic structures that enable us to understand how integrins bind extracellular matrix macromolecules and transmit force to them. Structures show how small molecules and Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptides bind to integrins, including a pro-TGF-β3 peptide bound to integrin αVβ6 5,8–10. A single fibronectin domain was soaked into integrin αVβ3 crystals; however, a second domain bearing a synergy site important in macromolecule binding was lacking and the binding orientation was constrained by the pre-existing integrin crystal lattice 11. As the effect of force on domains or multi-domain assemblies is highly dependent on the direction of the force vector 12, physiological orientation between integrins and their macromolecular ligands is necessary to understand the biological consequences of force transmission. Here, a co-crystal structure of the integrin αVβ6 head bound to intact pro-TGF-β1 provides insights into interaction between integrins and their macromolecular ligands.

Results and Discussion

Pro-TGF-β1 in complex with integrin αVβ6 head

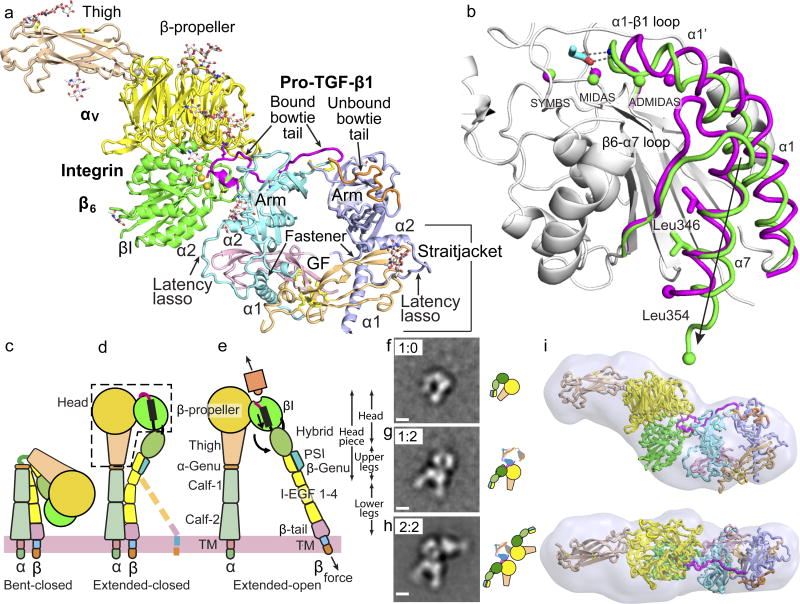

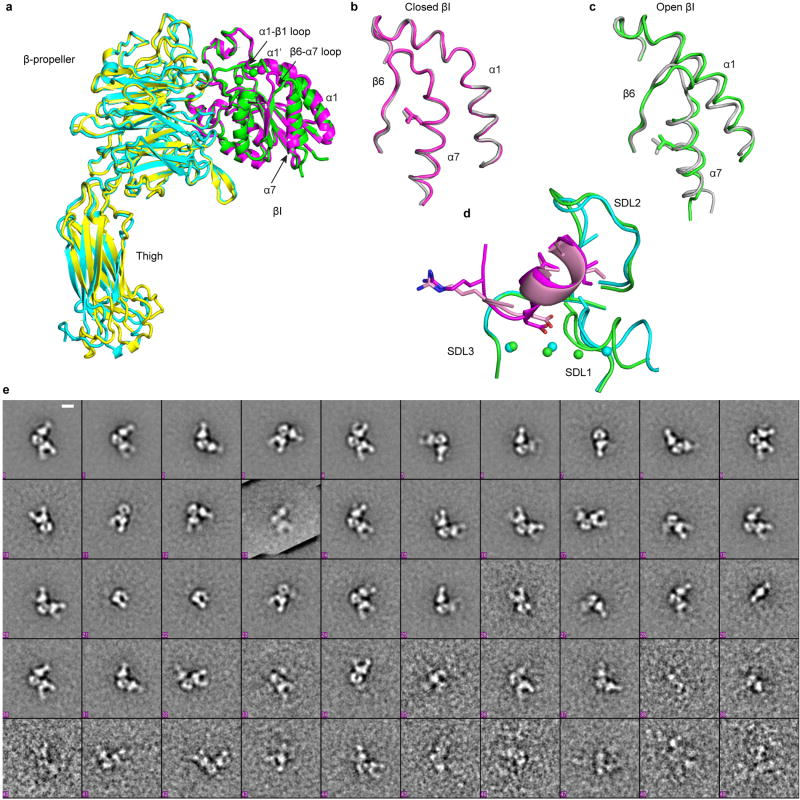

A three-domain αVβ6 head fragment containing the αV β-propeller and thigh domains and β6 βI domain yielded a 2.2 Å crystal structure (Table S1). Complexes containing one αVβ6 head bound to one of the monomers of the pro-TGF-β1 dimer (1:2) crystallized and diffracted to 3.5 Å (Fig. 1a). Remarkable conformational changes are observed for both the integrin and pro-TGF-β1 in the complex. Below, we describe 1) how ligand binding induces an open conformation of the αVβ6 βI domain, 2) the surprising amount of reshaping of pro-TGF-β1 induced by integrin binding, 3) the novel nature of the integrin-pro-TGF-β1 macromolecular interface, and 4) the molecular basis of force transmission.

Figure 1. The αVβ6:pro-TGF-β1 complex.

(a) Crystal structure of the 1:2 complex. Ribbon cartoon with domains in different colors, metal ions as gold spheres and bowtie tails in monomers colored magenta and orange. (b) Superimposition of αVβ6 βI domains with moving regions in magenta (closed) and green (open). Spheres show metal ions and equivalent Cα atoms at end of α7-helix. RGD Asp sidechain is shown in cyan with red oxygens and its hydrogen bonds and metal coordination to βI are dashed. (c–e) The three major integrin conformational states. (f–h) Negative-stain EM of a αVβ6 headpiece: proTGF-β1 2:2 complex preparation showing class averages representing the isolated αVβ6 headpiece (g), the 1:2 complex (h), and the 2:2 complex (i). Scale bar is 50 Å. All averages are in Extended Data Fig. S1. (i) SAXS ab initio reconstruction of αVβ6 head:pro-TGF-β1 1:2 complex shown as transparent surface with the fit complex crystal structure.

The unbound and pro-TGF-β-bound αVβ6 heads crystallize with their βI domains closed and open, respectively (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. S1a). Movements of 3–6 Å in the βI domain transmit allostery from the β1-α1 loop and MIDAS metal ion that bind the RGD Asp sidechain of pro-TGF-β to the α7-helix, which pistons toward the hybrid domain (Fig. 1b and schematized in Fig. 1d,e). The only previous integrin with open crystal structures, αIIbβ3, shows very similar movements (Extended Data Fig. S1b,c) 8, suggesting that the key events in headpiece opening will be shared by most integrin β-subunits. When integrin αVβ6 headpiece or ectodomain fragments bind pro-TGF-β, headpiece opening is evidenced in EM by swing of the β-subunit hybrid domain away from the α-subunit (Fig. 1f–h, Extended Data Fig. S1e) 4. Because the βI domain is inserted in the hybrid domain, pistoning at one connection at the α7-helix (arrow, Fig. 1b) forces the hybrid domain to pivot at its second connection (Fig. 1d,e). Integrin headpiece opening, communicated by movements within the βI domain between its ligand binding site and its hybrid domain interface, increases affinity for ligand 8. Moreover, opening alters the orientation of the hybrid domain in the upper β-leg, and hence the direction in which force is transmitted when traction force is exerted on the β-subunit by the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 1d,e).

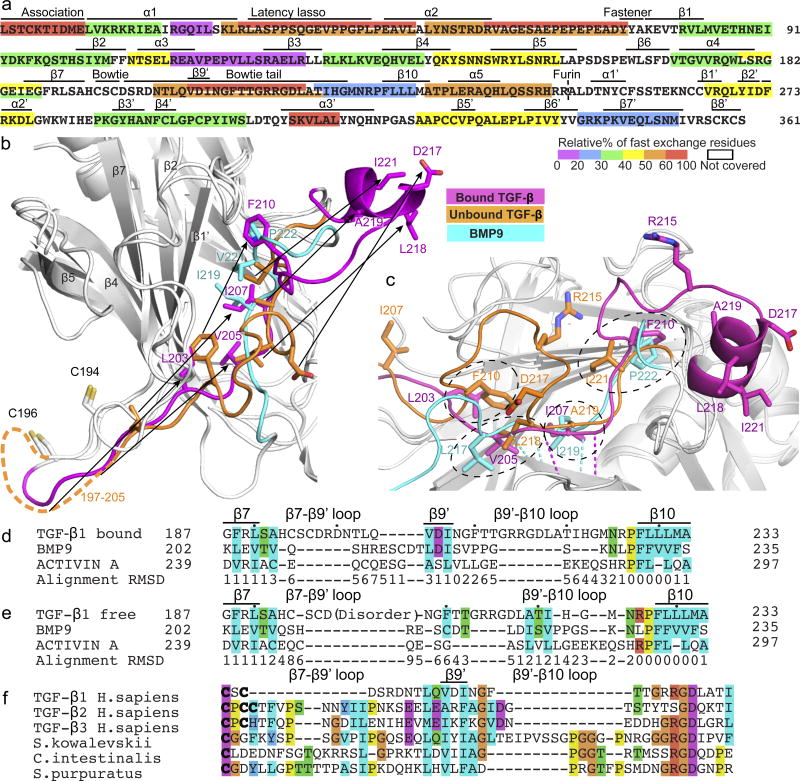

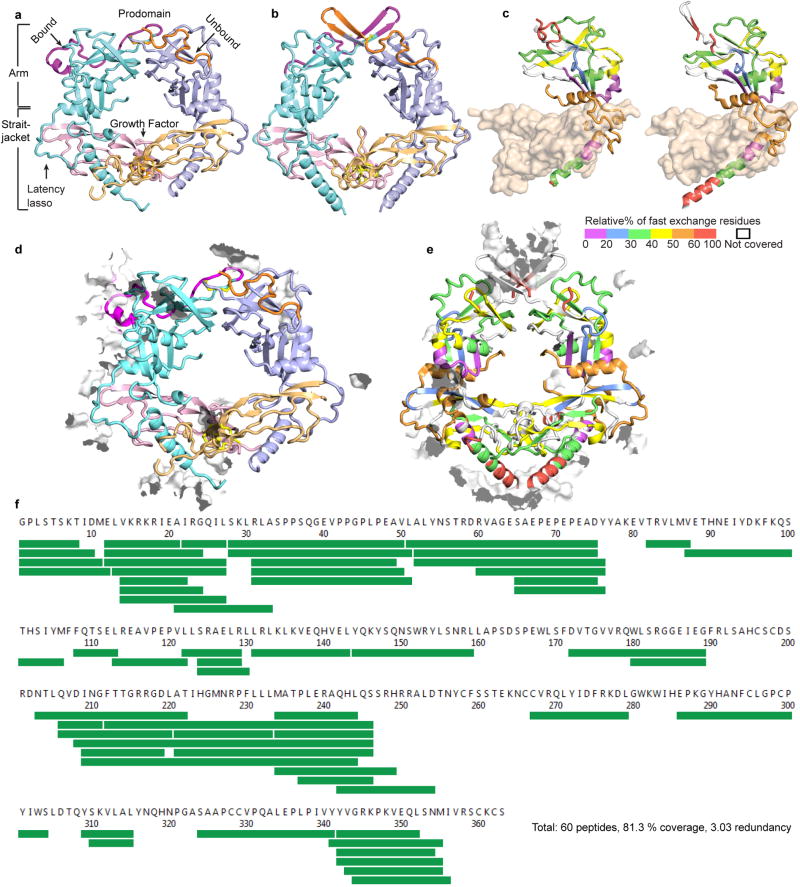

To complement current and previous crystal structures (Extended Data Fig. S2a, b) we measured backbone dynamics with hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX MS) (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. S2c, e–g) to gain insights into pro-TGF-β flexibility and force transmission. The arm domain of the prodomain shows little change among crystal structures (Extended Data Fig. S2a,b and S3a), correlating with slow backbone dynamics (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. S2f–g). Its jellyroll, β-barrel-like fold with large cross section and extensive β-sheet hydrogen bond network suit the arm domain to transmit force with little deformation 13. The bowtie tail follows bowtie knot cysteines that disulfide-link the two arm domains together (Fig. 1a and 2a–c). Bowtie tail residues 197–223 contain the integrin-binding motif and adopt markedly different backbone orientations in the integrin bound and unbound monomers (Extended Data Fig. S3a). In correlation, these residues exchange hydrogen for deuterium rapidly (Fig. 2a). In the straitjacket, the α1-helix has slow exchange where it passes between the two GF monomers and connects to the fastener, whereas the following latency lasso and α2-helix at the GF-arm domain interface have rapid HDX (Fig. 2a). Prodomain residues 1–9, the “association region” that contains Cys-4 that disulfide links to LTBP or GARP, also undergo rapid HDX and are disordered or differ between monomers (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. S2a, b and S3a). The association region must be able to adopt different conformations not only because LTBP and GARP partners differ completely in structure but also because Cys-4 in each monomer links to different cysteines in asymmetric 2:1 complexes of pro-TGF-β dimers with single partner molecules.

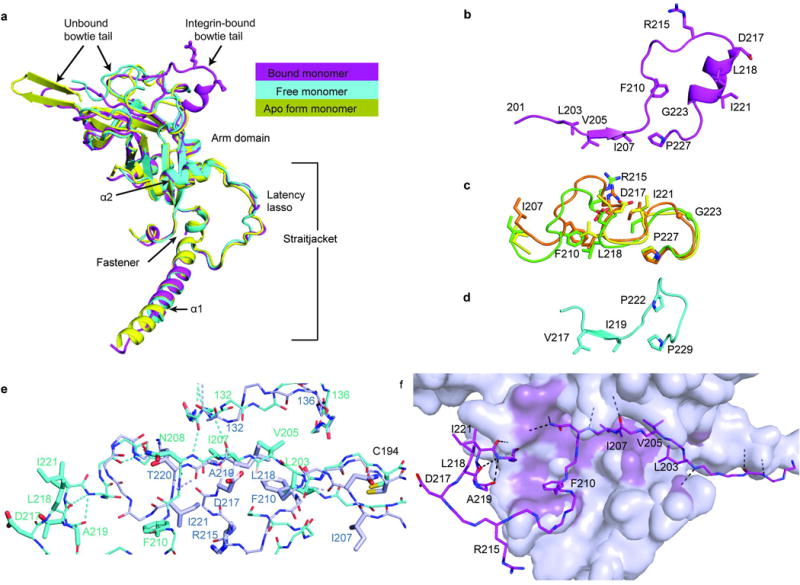

Figure 2. Reshaping of pro-TGF-β1 by integrin αVβ6 and evolution of TGF-β.

(a) HDX at 10 sec (see key) color-coded by % exchangeable residues in single or overlapping peptides. (b–c) Bowtie tails in pro-TGF-β1 monomers and corresponding residues in BMP9 14 after superposition on arm domains. In (c) β9-strand residue backbone hydrogen bonds are shown as color-coded dashes. (d–e) Structure-based sequence alignment 23 of arm domains of integrin-bound (d) and unbound (e) TGF-β1with BMP9 and activin 15 showing β7-β10 region. Black dots mark decadal residues. Cα atom difference from the average position is shown below the alignment in Å. (f) Alignment of TGF-β sequences from human and three representative deuterostomes.

Integrin binding stabilizes reshaping of a remarkable total of 27 residues in the bowtie tail that include not only the integrin binding motif, but residues that are well outside the binding site (Fig. 1a,, Extended Data Fig. S3a–d). Shape shifting occurs in a long hydrophobic groove at the end of the arm jellyroll domain distal from the GF (Fig. 2b,c, Extended Data Fig. S3e,f). In the unbound monomer, bowtie tail residues 203LQVDI207 are disordered and the hydrophobic sidechains of Phe-210, Leu-218, Ala-219, and Ile-221 bind in the groove. In the integrin-bound conformation, bowtie tail residues move long distances of up to 17 Å. Leu-203, Val-205, Ile-207, and Phe-210 replace Phe-210, Leu-218, Ala-219, and Ile-221 in the unbound state, respectively (Fig. 2b,c). Residues displaced from the hydrophobic groove contribute to the 218LATI221 amphipathic α-helix that binds in a hydrophobic pocket formed by the integrin β6-subunit βI domain. Among the residues that move into the hydrophobic groove in the integrin-bound conformation, Val-205 and Ile-207 take on a β-strand-like conformation and two mainchain hydrogen bonds link this region, which we term the β9’ bridge, to the β3-strand and hence integrate it into the arm domain β-barrel (Fig. 2c).

When the TGF-β, BMP9 14, and activin 15 arm domains are superimposed and the structurally equivalent residues are aligned, the integrin-bound state of pro-TGF-β1 better aligns structurally to the other arm domains than the unbound state, owing to the change in conformation at the β9’ bridge (Fig. 2d,e). The sequence that structurally aligns well with other family member β9′-strands in bound pro-TGF-β1, LQVDINGF, is highly conserved among human TGF-βs 1, 2, and 3 and in the single TGF-βs present in primitive deuterostomes 1 (Fig. 2f). These results suggest that TGF-β evolved from an ancestor with a conformation that resembles other family members and the integrin-bound state of TGF-β. Thus key specializations in TGF-β, the bowtie disulfides and integrin binding motifs, evolved as insertions in loops on each side of the β9’ bridge (Fig. 2f). The β7-β9’ loop elongated in TGF-β and contains one to three cysteines that form bowtie knot interchain disulfide(s) rather than intrachain disulfides as in BMP9 and activin (Fig. 2d,f). A long insertion in the β9’-β10 loop contributes the RGDLXXL/I motif (Fig. 2d,f). Both insertions contribute to TGF-β1 reshaping and hence to integrin binding, while insertion of the bowtie disulfides contributes to latency 6 and also enables transmission of integrin-applied force from one prodomain monomer to the other.

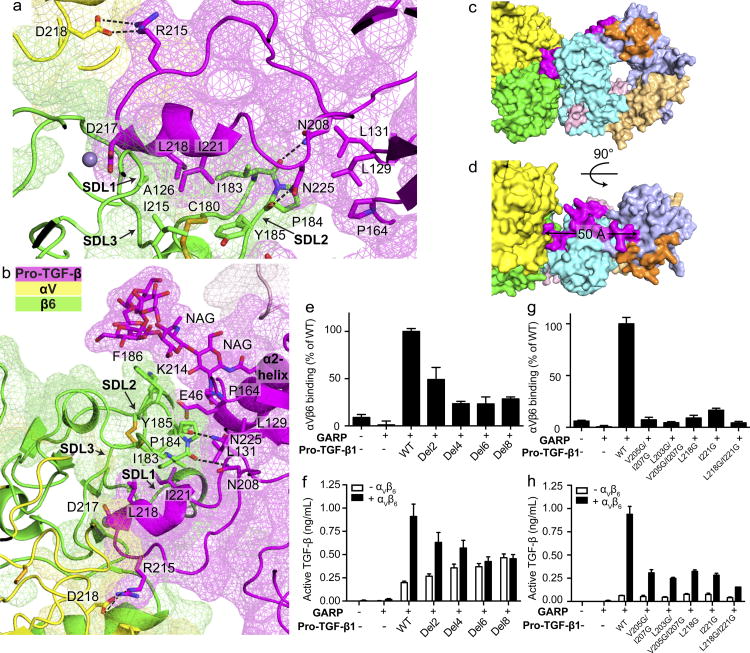

An unusual macromolecular interface

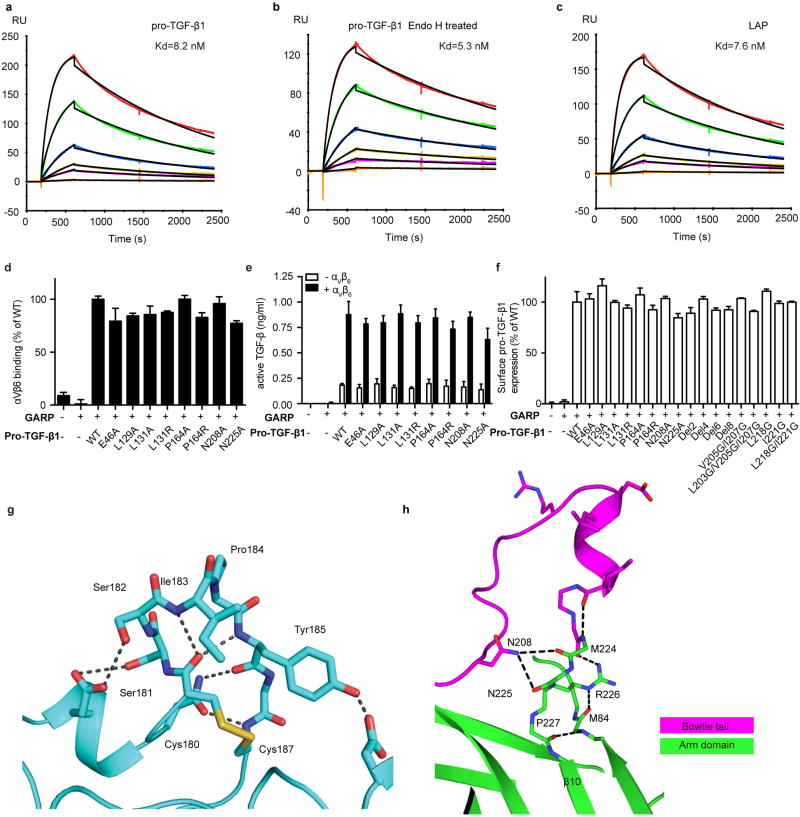

The macromolecular interface is largely formed by three specificity-determining loops (SDL1, 2, and 3) of the βI domain 5 and nearby portions of the αV β-propeller domain in contact with the protruding bowtie loop of pro-TGF-β1 (Fig. 3a,b); however, the interface extends further to include the βI domain α2-helix in contact with the prodomain latency lasso (Fig. 1a). The interface is typical neither of protein-protein or protein-peptide interfaces. The interfaces are much larger than previously visualized integrin complexes, 1090 Å2 on αVβ6 and 1210 Å2 on pro-TGF-β, and comparable in size to those between antibodies and protein antigens 16. However, in contrast to the relatively planar surface of most protein-protein complexes, the αVβ6 and pro-TGF-β1 interface is highly interdigitated (Fig. 1a, 3a,b). The RGDLATI motif of pro-TGF-β1 protrudes into a deep narrow pocket (~ 20 Å deep, ~15 × ~15 Å wide) formed at the interface between the αV β-propeller and β6 βI domains (Fig. 3a). The βI domain specificity determining loop 2 (SDL2) forms a complementary protrusion into a deep cleft (~ 20 Å deep, ~ 20 Å wide) on pro-TGF-β1 between the protruding DLATI α-helix and a glycan N-linked to the prodomain α2-helix (Fig. 3b). On the RGDLATI-facing side of SDL2, β6 Ile-183, Tyr-185 and the Cys-180/Cys-187 disulfide together with Ala-126 in SDL1 and Ile-215 in SDL-3 cradle Leu-218 and Ile-221 in the RGDLXXI motif. The opposite side of SDL2 together with SDL3 contacts the pro-TGF-β1 α2-helix and the first two N-acetylglucosamine residues of its N-linked glycan. At its tip, SDL2 forms backbone hydrogen bonds to the sidechains of Asn-208 and Asn-225 in the bowtie tail (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. Interaction between TGF-β1 and αVβ6.

(a–b) Slab views through the αVβ6:TGF-β1 interface showing surfaces of αV, β6, and TGF-β1 (mesh), ribbon cartoons, key N-glycan and protein sidechains (sticks), hydrogen bonds (black dashes) and MIDAS metal ion (sphere). (c–d) Surface representations of the 1:2 complex, color coded as in Fig. 1a. (e–h) Binding and activation of WT and mutant pro-TGF-β1 by αVβ6. (e and g) Binding of FITC-αVβ6 to pro-TGF-β1/GARP HEK293T co-transfectants as mean fluorescence intensity. (f and h) Activation of TGF-β1 by HEK293T cells co-transfected with pro-TGF-β1 and GARP, with or without αV and β6. Data in e–h are mean ±s.d. of 3 biological (transfection) replicates.

Small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) in solution demonstrates a molecular envelope into which the crystal structure fits well (Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. S5a). The highly constrained and interdigitating interface leads to a well-defined orientation between αVβ6 and pro-TGF-β1 that is supported by hydrogen bond networks. The β6 SDL2 backbone is supported by many backbone hydrogen bonds (Extended Data Fig. S4g). In TGF-β1, the specific orientation of the protruding RGDLATI motif is supported by a network of hydrogen bonds that tie it into the arm domain. The DLATI α-helix is followed by the β10-strand that is central in the arm domain, and the intervening four residues are all supported by mainchain or sidechain-mainchain hydrogen bonds (Extended Data Fig. S4h).

The extensive neoepitope on pro-TGF-β1 created by integrin-induced reshaping includes bowtie tail residues 197–213 that lie outside the integrin footprint and extend 50 Å from the footprint to the bowtie disulfide (Fig. 3c, d). The concept that integrin-induced conformational change in ligands can propagate far outside the integrin binding site is of great interest, and may be relevant to integrin remodeling or assembly of the extracellular matrix 7.

Communication across the interface

Even though bowtie tail residues 197–213 lie outside the integrin-binding site, we predicted that they were required to permit residues 215–221 to move out of the groove in the arm domain and form the integrin binding site. Indeed, serial deletion of bowtie residues encompassing up to residues 199–206 progressively decreased αVβ6 binding to pro-TGF-β1 (Fig. 3e) and αVβ6–dependent TGF-β1 activation (Fig. 3f) while having no effect on pro-TGF-β1 expression (Extended Data Fig. S4f). Deletion of 6 or 8 bowtie tail residues greatly reduced binding and completely abolished activation. Since none of these residues contact αVβ6, their deletion demonstrates the requirement of the remarkable reshaping of pro-TGF-β1 for binding and integrin-dependent activation. Interestingly, bowtie tail deletions increased integrin-independent TGF-β1 activation (Fig. 3f), showing that the bowtie tail is also important for maintaining latency. This finding is consistent with a focus of inherited mutations near the bowtie knot and tail in Camurati-Engelmann disease associated with spontaneous TGF-β1 activation 4,17.

We also mutated bowtie tail residues L203, V205, and I207 that have no contact with the integrin and bury in the hydrophobic groove in the integrin-bound state. Mutations V205G/I207G and L203G/V205G/I207G strongly inhibited integrin binding to and activation of TGF-β (Fig. 3g,h). These residues stabilize the integrin-bound conformation of the arm domain in which residues V205-I207 form a β9′ bridge and compete binding of residues to the groove that reshape to form the integrin-binding amphipathic helix (Fig. 2b,c). The importance in binding and activation of residues that lie outside of the integrin binding site in stabilizing a particular conformation of the arm domain demonstrates the biological importance of the macromolecular complex defined here. Not only is the binding surface extensive and interdigitated, but regions of the arm domain distal from the ligand binding site contribute to stabilizing a particular integrin-binding conformation of the macromolecule.

Residues L218 and I221 form the hydrophobic face of the DLATI α-helix that projects into the interlocked binding site. Their mutation consistently reduced both integrin-dependent TGF-β activation and binding (Fig. 3g,h). In contrast, single amino acid substitutions provided no evidence for the importance of integrin contacts with other pro-TGF-β1 residues. Mutations of interacting pro-TGF-β1 residues Glu-46, Leu-129, Leu-131, Pro-164, Asn-208, or Asn-225 have no effect on integrin binding to or activation of TGF-β1 (Extended Data Fig. S4d, e). Furthermore, EndoH treatment to cleave the glycan N-linked to Asn-53 has little effect on affinity (Kd = 5.3 nM) compared to WT (Kd = 8.2 nM) (Extended Data Fig. S4a, b). The importance of the pro-TGF-β1 region covered by these mutations may be to provide overall shape complementarity for the integrin rather than specific interactions.

Together, structure, evolution, mutation, and dynamics provide a view of integrin recognition of a macromolecular extracellular matrix ligand that differs from any previously imagined. Crystal structures of uncomplexed porcine and human pro-TGF-β1 have bowtie tail structures similar to that of the uncomplexed monomer defined here (Extended Data Fig. S3c), and suggest that in the conformation that predominates biologically, the integrin-binding motif lies hidden in a hydrophobic groove of the arm domain. Conformational change facilitated by rapid dynamics (Fig. 2a) of this region must precede integrin binding. Integrin binding thus stabilizes conformational change not only in the integrin-binding motif but in pro-TGF-β1 regions far outside the interface, and sets the stage for subsequent force-dependent activation.

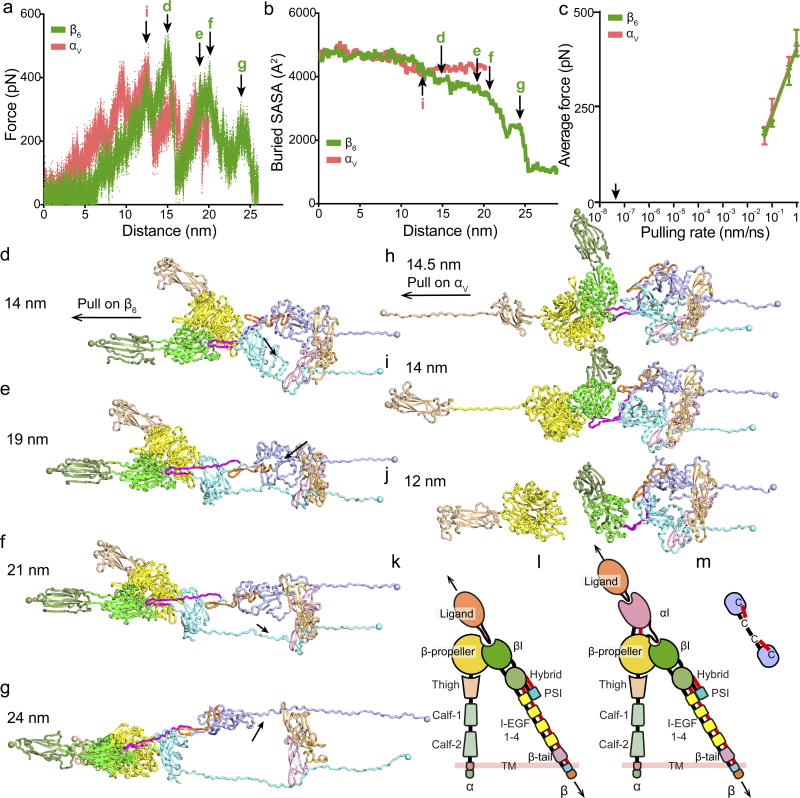

Pathway dependence of activation of TGF-β by force

The highly defined integrin-ligand orientation demonstrated by SAXS, supported by a network of hydrogen bonds that link the RGDLATI motif to the arm domain, define the orientation for force application in TGF-β activation. The force required for release of TGF-β from the αVβ6-pro-TGF-β1 complex is applied by actin cytoskeleton movement through adaptors to the β6-subunit cytoplasmic domain and resisted by LTBP held in the extracellular matrix 6. Since integrin legs and LTBP have flexible domain-domain interfaces, and will align with force, force in simulations was applied through head-proximal leg domains and resisted by the prodomain Cys-4 residues that link to LTBP (Fig. 4a–j). We model TGF-β activation by one integrin, because if two bind, they have opposite orientations (Fig. 1h). Retrograde actin flow stabilizes integrins in the open, high-affinity conformation; thus if two integrins bind, one will be more aligned with actin flow, and hence more stabilized in a high-affinity, pro-TGF-β-bound state than the other 8,18.

Figure 4. Simulation of force-dependent activation of pro-TGF-β1 by αVβ6.

(a–j) Using molecular dynamics, pulling at 0.05 to 1 nm/s on β6 hybrid or αV thigh domain C-terminal residues was resisted by Cys-4 residues in each prodomain. (a–b) Force (a) and buried solvent accessible surface area (SASA) between the GF and prodomains as a surrogate for release (b) for 1 representative of 3 simulations at 0.05nm/s. Arrows mark events shown in corresponding panels (d–j). (c) Average force at each pulling rate (mean±s.d. of 3 independent simulations). Arrow marks physiologic actin retrograde flow rate. (d–i) Snapshots from pulling on β6 (d–g) or αV (h–j) at indicated distances. Structures in ribbon cartoon are color-coded as in Fig. 1a. Spheres show residues used for force application or resistance. Arrows in d–g mark fastener or α2 helix unfolding. (h–j) 3 different simulation results of pulling on αV. (k–m) Schematics of domain-domain junctions in αI-less integrins such as αVβ6 (k), αI-containing integrins such as αLβ2 (l), and detail at integrin EGF domain junctions (m). Arrows show tensile force. Domain polypeptide connections and disulfide bonds to junctions are black and red, respectively.

Molecular dynamic simulations of pulling on the integrin β-leg at rates from 1 to 0.05 nm/ns, each with three independent replicates, gave essentially identical results. Early in simulations, the macromolecular interface rotated into alignment with the pulling direction, and the prodomain association region in each monomer unwound between Cys-4 and the position where the α1-helix intercalates between the two GF monomers (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Movie 1). This showed that force applied to one prodomain monomer was transmitted to the other so that both resisted force. Pulling on the β6-subunit was continued until the GF was largely released from the prodomain, as shown by decrease in GF solvent-accessible surface area burial (Fig. 4b) and disruption of all secondary structure in the straitjacket that surrounds the GF and enforces latency (Fig. 4g). The highest force peaks were associated with unsnapping the fastener and unwinding the α2-helix in each monomer, which are arrowed in Fig. 4a and depicted as structure snapshots in Fig. 4d–g. The fastener links the end of the α1-helix to the arm domain through backbone hydrogen and π-cation bonds, and encircles the β-finger in each GF domain (Fig. 1a) 4. The prodomain α2-helix interfaces both the arm domain and the GF and accommodates changes in orientation between them 14. The simulations suggest that these are the most force-resistant elements of the straitjacket, i.e., the highest energy barriers that must be surmounted for TGF-β activation, in agreement with findings that securing the fastener with a disulfide abolishes TGF-β activation 4 and that mutation of α2-helix residue Tyr-52 that interacts with the GF in heritable disease is associated with TGF-β activation 4,17. The force applied in simulations declined with pulling rate (Fig. 4c) and would be lower 19 at the physiological rate of actin retrograde flow (arrow, Fig. 4c).

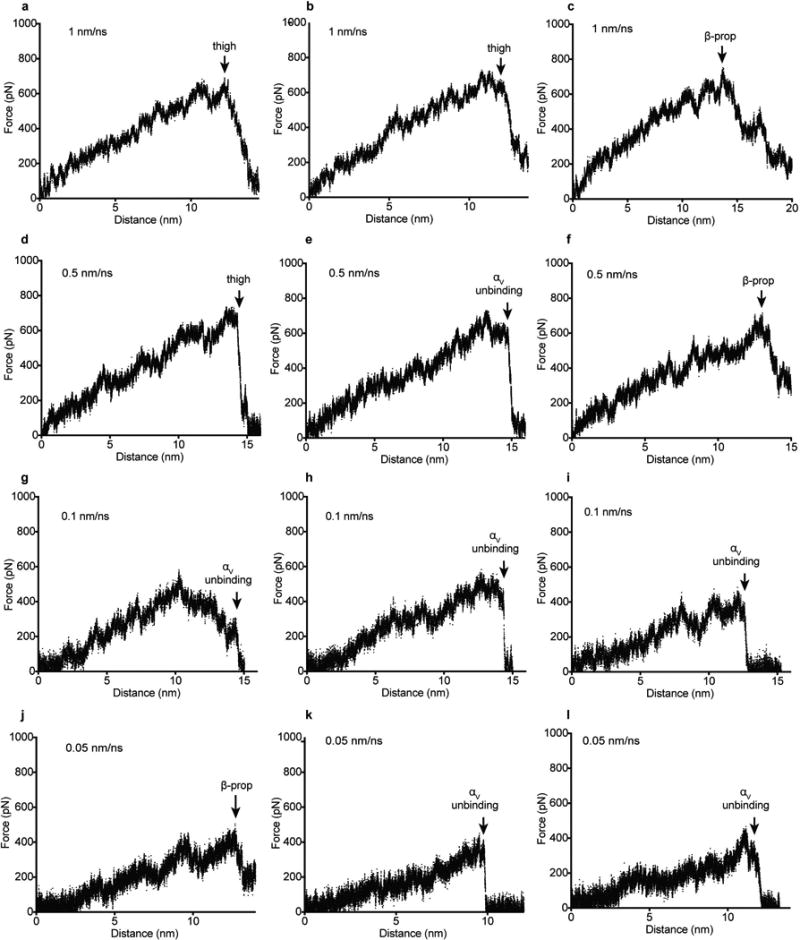

To better define macromolecular features important in the physiological pathway of integrin activation by force transmission from the β6-leg, we compared a non-physiologic direction of application of force from the αV-leg through the head-proximal thigh domain. Pulling on αV caused the macromolecular interface to rotate differently (Fig. 4h–j) than in pulling on β6 (Fig. 4d–g). Although the prodomain α1-helices unwound at their C-terminal ends, little change occurred elsewhere in the prodomain including the straitjacket (Fig. 4h–j). All 12 αV simulations had to be terminated following catastrophic failure in the αV-subunit that precluded TGF-β activation. Either the thigh domain unfolded (Fig. 4h), the β-propeller domain unfolded (Fig. 4i), or the β-propeller domain separated from both pro-TGF-β1 and the β6-subunit (Fig. 4j).

The comparisons between pulling on the integrin α and β-subunits reveal macromolecular specializations in both the integrin and pro-TGF-β for force exertion in a specific, physiologic direction. Despite reaching similar levels as in β6 pulling, force in αV pulling was completely ineffective in inducing straitjacket removal (Fig. 4a, c, Extended Data Fig. S6 and S7). This might relate to the different orientation of the RGD motif between the β9′ and β10-strands after integrin alignment by force, which places more stress on β9′ and the bowtie tail at the R end of RGD in αV pulling and more stress on β10 at the D end of RGD in β6 pulling. The unbinding of αV and not β6 from pro-TGF-β during pulling is consistent with the greater importance of the RGD Asp than Arg in integrin binding 20,21.

The selective unfolding of αV compared to β6 by pulling force reveals a feature of integrin domains that, while inherent in their known structure, has not previously been pointed out as an evolutionary specialization of domains in force transmission pathways. In the cross-section for force transmission in tandem-domain proteins, force density is highest at the connection between tandem domains, where there is typically a connection through a single polypeptide chain. In the force-sensitive regions on each side of these junctions, all domains in integrin β-subunits are double-strength, because they have either two polypeptide connections or a single polypeptide connection reinforced with a disulfide bond (Fig. 4k,l). The βI domain is inserted in the hybrid domain, to which it has two polypeptide connections. The hybrid and EGF domains each have disulfide bonds at their connecting ends, with only one residue in between (Fig. 4m). This explains why integrin EGF domains have a specialization for bearing force that sets them apart from classical EGF domains: an extra disulfide between their first and fifth Cys residues (C1 and C5); only one residue intervenes between C8 in one integrin EGF domain and C1 in the next.

In contrast, the connections between the integrin α-subunit domains have a single polypeptide connection and lack securing disulfides (Fig. 4k). The ligand-binding αI domain, present in a subset of integrin α-subunits, relays force and activation to the βI domain 18,22. In an exception that proves the rule, the αI domain has two polypeptide connections and a disulfide reinforcement (Fig. 4l). The presence of double connections at all domain termini in the force-bearing β-subunit pathway (13/13) and not in the non-force-bearing α-subunit pathway (0/7) in integrins is statistically significant (distribution by chance alone, p <10−5), and strongly suggests that this is a specialization of integrins driven by evolution.

In summary, we have described how an integrin reshapes a macromolecular, extracellular matrix ligand. The binding orientation and the structures of the integrin and its ligand appear to have evolved to support specific pathways for tensile force transmission through each macromolecule to enable cytoskeletal force applied to integrin αVβ6 through its β-subunit to activate TGF-β1.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

The human pro-TGF-β1 construct contains an N-terminal 8-His tag, followed by a SBP tag and a 3C protease site. A C4S mutation, an R249A furin cleavage site mutation and N-glycosylation site mutations N107Q and N147Q were introduced to facilitate protein expression, secretion and crystallization. Pro-TGF-β1 was expressed in CHO Lec 3.2.8.1 cells utilizing the pEF-puro vector, purified in three steps as described in 1 and yielded 1 mg purified protein per liter culture supernatant. The same protein was used in EM, SAXS, HDX, and surface plasmon resonance.

Soluble αVβ6 headpiece was prepared as in 2. The αVβ6 head uses the same αV construct as in the αVβ6 headpiece and the β6 βI domain (residues 108–352) with I270C mutation followed by a 6X His tag. Proteins expressed in HEK293S Gnt I− cells with Ex-Cell 293 serum free media (Sigma) were purified using Ni-NTA affinity column (Qiagen). Protein was cleaved with 3C protease at 4 °C overnight and passed through Ni-NTA resin and further purified using an ion exchange gradient from 50 mM NaCl to 1M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 (Q fast-flow Sepharose, GE healthcare) and gel filtration (Superdex 200, GE healthcare). Cell lines were originally from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and not authenticated or tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Crystal structures

Crystals of αVβ6 head (1 µl, 5mg/ml in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2) were formed in hanging drops at 20 °C with 1 µl of 5% PEG 3000, 25% PEG 200, 0.1 M MES pH 6.0. Crystals of αVβ6 head/pro-TGF-β1 (3 mg/ml, 1:2 stoichiometry, separated from 2:2 complex and uncomplexed material by gel filtration in the same buffer as the head except with 1 mM MnCl2 instead of MgCl2) were similarly formed with 9% PEG 8000, 0.1 M imidazole pH 8.0. Crystals were cryo-protected by well solution containing 30% glycerol. Data collection at the wavelength of 1.0332 Å and structure determination were as in 2 with truncated αVβ6 headpiece2 and porcine pro-TGF-β11 as search models for molecular replacement.

In the αVβ6 head model, 96.1%, 3.9%, and 0% of residues have backbone dihedral angles in the favored, allowed, and outlier regions of the Ramachandran plot, respectively as reported by MolProbity. The MolProbity percentile scores are both 99 for clash and geometry. In the αVβ6 head/pro-TGF-β1 complex model, 90.0%, 8.8%, and 0.4% of residues have backbone dihedral angles in the favored, allowed, and outlier regions of the Ramachandran plot, respectively as reported by MolProbity. The MolProbity percentile scores are 97 and 100 for clash and geometry, respectively.

Small angle x-ray scattering

αVβ6 head/pro-TGF-β1 complex (1:2 stoichiometry) was purified by gel-filtration as described above. Samples at 0.4 and 3 mg/ml concentrations were passed through a 0.22 µm pore Ultrafree-MC Centrifugal Filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA) before measurement. Measurements at Brookhaven National Laboratories Beamline X9 used a high sensitivity 300K Pilatus detector at 3.4 m distance. 20 s exposures in triplicate were collected while the protein sample was passed through a flow capillary. All datasets from both concentrations were merged and I(0) and the pair distance distribution function P(r) were calculated from the merged scattering intensities I(q) using the software PRIMUS 3. Ab initio modeling, averaging and surface map conversion were as in 4.

Negative-stain electron microscopy

Purified proTGF-β1 and αVβ6 headpiece (2:2 molar ratio) were subjected to Superdex S200 chromatography in HBS (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, MgCl2) and the peak fraction was subjected to negative-stain electron microscopy as described 1.

Surface plasma resonance

Surface plasmon resonance studies were performed using a Biacore 3000 instrument (GE Healthcare). Pro-TGF-β1, LAP1, and Endo H-treated pro-TGFβ-1 were amine immobilized on a CM5 chip. Purified αVβ6 headpiece was injected at 20 µl/min in HBS. The surface was regenerated with a pulse of 25 mM HCl at the end of each cycle. Kinetics were analyzed with Biacore evaluation software version 4.0.1 (GE Healthcare).

Pro-TGF-β1 mutagenesis

Wild-type human pro-TGF-β1 was inserted into a pcDNA3.1 (-) expression vector. Mutations and serial truncation mutations were generated using QuikChange (Stratagene). All mutations were verified by DNA sequencing.

Pro-TGF-β1 cell surface binding by FACS

Assays were as described 2. Wild-type or mutant pro-TGF-β1 in pcDNA3.1 (-) vector and GARP in pLEXm vector were transiently co-transfected into 293T cells using lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). Specific binding of 50 nM FITC-αVβ6 to pro-TGF-β1-GARP on transfectants was expressed as binding in 1 mM Mg2+/ Ca2 minus binding in 10 mM EDTA. Cell surface expression of pro-TGF-β1-GARP was determined by flow cytometry using TW7-28G11 anti-TGF-β1 antibody (Cat. #146704, Biolegend, San Diego, CA) and FITC conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (F-2761, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). HEK293T cell line from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) was not authenticated or tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Pro-TGF-β1 activation

Assays are done similarly as previously described 2. Pro-TGF-β1/GARP co-transfected 293T cells were co-cultured with human αVβ6 or mock 293T transfectants and transformed mink lung cells (TMLC) kindly provided by D. Rifkin transfected with a TGF-β1-sensitive luciferase reporter 5. Cells were lysed after 24 hours of incubation and the luciferase activity induced by TGF-β1 was measured using the luciferase assay system (Promega). A standard curve was calculated with serial diluted purified mature TGF-β1 protein (eBiosciences). TMLC line was verified to be TGF-β-sensitive and was not tested for mycoplasma contamination.

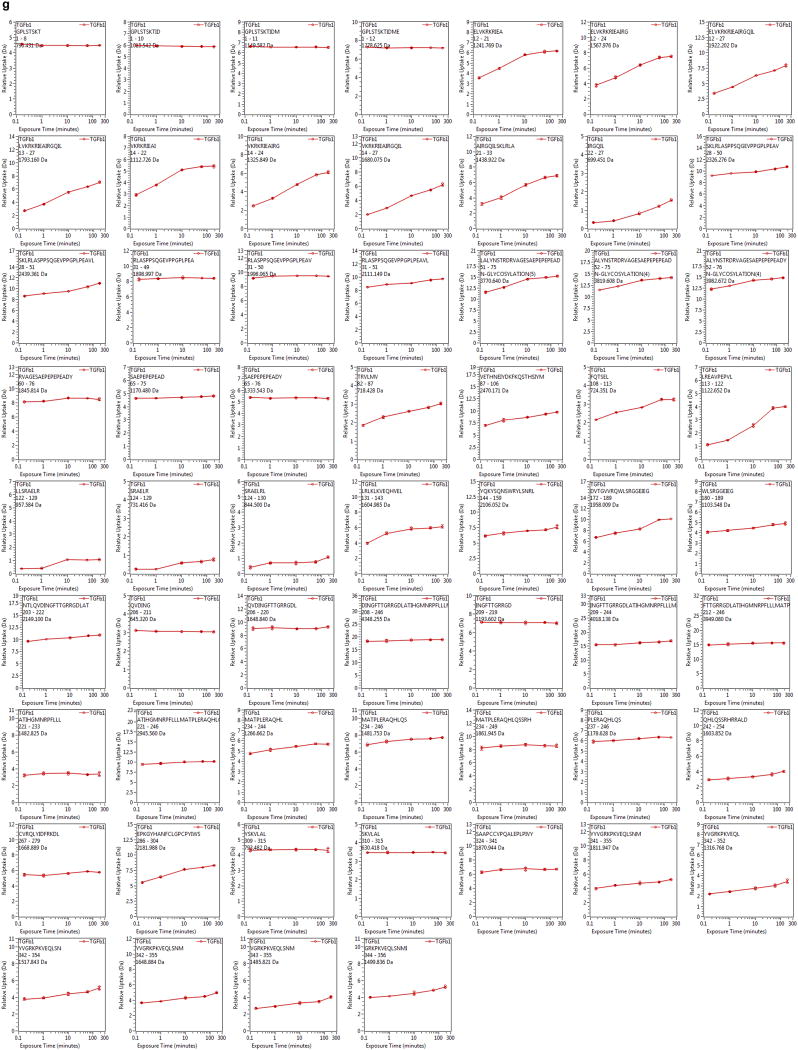

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange

Hydrogen deuterium exchange experiments were performed as described 6. 62 pmol of pro-TGF-β1 were diluted 15-fold into 20mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 99% D2O (pH 8.0) at room temperature. At deuterium exchange time points from 10 sec to 180 min, an aliquot was quenched by adjusting the pH to 2.5 with an equal volume of 150 mM potassium phosphate, 0.5 M tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP-HCl), H2O. Samples were digested with pepsin and analyzed as described 6. The average amount of back-exchange was 18% to 25%, based on analysis of highly deuterated peptide standards. All comparison experiments were done under identical experimental conditions such that deuterium levels were not corrected for back-exchange and are therefore reported as relative 7. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The error of measuring the mass of each peptide was ± 0.12 Da. Pro-TGF-β1 sequence coverage was 81.6% corresponding to 60 peptic peptides (Extended Data Fig. S3c, d).

Force-probe MD simulations

The β6 hybrid domain 2 was added to the open αVβ6 head in the 2:1 complex by superimposing on the open αIIbβ3 headpiece 8 and modeling residues at the junction. To minimize the simulation box, thigh or hybrid domains were removed in β6 and αV pulling, respectively. The protein was solvated in a ~ 50×11×9 nm rectangular box containing ~ 600,000 atoms with simple point charge (SPC) water. Simulations with Gromacs 5.1.2 used OPLS-AA as described 9. Harmonic springs (500 kJ mol−1 nm−1) were attached to β6 residue Cys432 or αV residue Thr596 and moved away from the two prodomain Cys4 residues at 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, or 1 nm/ns for ~30 nm. Cys4 residues were positionally restrained with spring constants of 1000 kJ mol−1 nm−1. Three repeats at each pulling rate differed in random initial velocities. Simulations were performed using Bridges at Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center. Average force was calculated from the beginning of pulling until the completion of the last major event arrowed in Extended Data Fig. S6 and S7. Solvent accessible surface areas were calculated with the get_area command of Pymol.

Data availability

Structural coordinates were deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes 5FFG and 5FFO for the αVβ6 head and αVβ6 head/pro-TGF-β1 1:2 complex, respectively. X-ray diffraction images were deposited in the SBGrid Data Bank with Digital Object Identifier http://dx.doi.org/10.15785/SBGRID/391 (the αVβ6 head) and http://dx.doi.org/10.15785/SBGRID/392 (αVβ6 head/pro-TGF-β1 1:2 complex).

Extended Data

Figure S1. Crystal structure comparisons.

(a) Superimposition of αVβ6 headpiece (4UM9, chains A and B) 5 in closed conformation (αV yellow, β6 magenta) and head in open conformation in complex with pro-TGF-β1 (αV cyan, β6 green). (b and c) Superimposed β3 and β6 βI domains, showing only moving regions in magenta or green (β6) and white (β3). (d) Comparison of the macromolecular pro-TGF-β1 complex and soaked-in pro-TGF-β3 peptide complex showing integrin-binding loops (magenta and pink, respectively) and βI domain loops and metal ions (green and cyan, respectively). The conformation of the 215RGDLATI221 motif in intact pro-TGF-β1 when co-crystallized with αVβ6 is similar to that of the 241RGDLGRL247 motif in a pro-TGF-β3 peptide soaked into αVβ6 crystals5.

(e) The complete set of EM class averages (5,546 particles) from a gel filtration peak of the 2:2 pro-TGF-β1/αVβ6 complex. While most class averages show 2:2 complexes, 1:2 complexes and isolated αVβ6 are also present, presumably due to dissociation of 2:2 complexes. Scale bar in the first class average is 50 Å.

Figure S2. Contacts in crystals of pro-TGF-β1 and HDX.

(a and b) The pro-TGF-β1 moiety of the 2:1 complex (a) and isolated porcine pro-TGF-β1 (b) in identical orientations. Ribbon cartoons are colored as in Fig. 1a. (c) Unbound prodomain monomer from the complex structure (left) and prodomain monomer from isolated TGF-β1 (right) shown as ribbon cartoons with growth factor dimers in identical orientations. Ribbon cartoons are colored according to the relative % of HDX at 10 sec shown in the key, using peptides shown in Fig. 2a. (d–e), Crystal lattice environments of integrin-bound human pro-TGF-β1 (d) and uncomplexed porcine pro-TGF-β1 (e). Portions of other molecules in the crystal that pack within 4 Å, including the bound integrin, are shown as white surfaces. Coloring in (d) is as in Fig. 2a and coloring in (e) is as in (c) according to fast exchange rate as shown in the key. (f) HDX MS pepsin peptide coverage map of human pro-TGF-β1. (g) Deuterium incorporation kinetics for all peptic peptides followed with HDX MS.

Figure S3. Pro-TGF-β structure comparisons.

(a) Superimposition of bound and free pro-TGF-β1 prodomain monomers from the complex with αVβ6 and from an unbound (apo) porcine pro-TGF-β1 dimer 4. (b–d) The bowtie tail regions in pro-TGF-β1 crystal structures and the corresponding region of pro-BMP9, shown in identical orientations and vertically aligned after superposition on the arm domain. (b) Integrin-bound human pro-TGF-β1 monomer. (c) Bowtie tail regions in unbound monomers from the complex (orange), free human pro-TGF-β1 (B.Z., X.D., and T.A.S., unpublished, green), and free porcine pro-TGF-β1 4 (yellow). Arg-215 and Asp-217 of the RGD motif in the unbound form are exposed to solvent but are not sufficiently accessible for integrin binding. (d) BMP9 14. (e) Integrin induced bowtie tail reshaping. Bowtie tails in the integrin-bound (cyan) and free (light blue) monomers are shown as backbone in thin stick with sidechains participating in hydrogen bonds or interacting with the integrin or arm domain hydrophobic pocket shown as thick sticks. The sidechains of residues N208 and T220 form hydrogen bonds to backbone in equivalent positions at a turn. Hydrogen bonds in the integrin-binding region and b9’-bridge region are shown in same color as sticks. The backbone shifts at residues 132–136 that line the bowtie groove. (f) The integrin-bound bowtie tail is stabilized in a hydrophobic cleft of the arm domain. Bowtie tail backbone and sidechains of key residues are shown as magenta sticks, and the remainder of the arm domain is show as a silver surface with regions in close contact with the bowtie colored violet-purple. Hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashed lines.

Altogether, the HDX and analysis of crystal lattice contacts in Extended Data Fig. S2 together with comparisons of monomer structures in Extended Data Fig. S3a–c provide insights into the flexibility of the bow tie tail and association regions. In absence of integrin binding, the bow tail is dynamic. The structure of its C-terminal region is similar in the uncomplexed monomer here and a previous uncomplexed, porcine pro-TGF-β1 dimer (apo form) 4. However, its N-terminal portion is either unstructured or dependent on crystal lattice contacts. The N-terminal association region is similarly either unstructured or adopts a structure that is dependent on crystal lattice contacts.

Figure S4. Binding, activation, and structural details.

(a–c) Surface plasmon resonance measurements of integrin αVβ6 headpiece binding to surface immobilized furin-mutant pro-TGF-β1 (a), Endo H treated furin-mutant pro-TGF-β1 (b), and the untreated prodomain expressed in absence of the GF (latency-associated peptide, LAP) (c). Curves are colored red, 100 nM; dark green, 50 nM; blue, 20 nM; yellow, 10 nM; magenta, 5 nM; orange, 1 nM. The global fit to the 1:1 binding model is in black. Kd and chi-square values from fits are shown. (d) Binding in presence of Mg2+ of FITC-αVβ6 to WT or mutant pro-TGF-β1/GARP HEK293T co-transfectants as specific mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) (% of WT). The mutated residues lie on the arm domain outside the RGDLATI motif. (e) Activation of TGF-β1 by HEK293T cells co-tranfected with pro-TGF-β1 and GARP, with or without αV and β6, assayed with luciferase reporter cells, and standardized with purified TGF-β1. The mutated residues lie on the arm domain outside the RGDLATI motif. (f) Expression of WT and mutant pro-TGF-β1/GARP complexes on 293T transfectants determined by immunofluorescence flow cytometry with TW7-28G11 antibody. Values represent the mean of 3 individual tests and the error bars represent the s. d.. (g) Hydrogen bonds within SDL2 in the β6 βI domain. (h) The hydrogen bond network in the 4 residues, M224-P227, that link the bowtie tail to the β10 strand in the integrin-bound pro-TGF-β1 arm domain.

Binding of integrin αVβ6 to pro-TGF-β1 does not liberate the GF4. The experiments in Extended Data Fig. S4 panels a–c address the question of whether integrin binding loosens the prodomain’s grip on the GF. Destabilization of the binding energy for the GF would require an identical stabilization of integrin binding to the isolated prodomain compared to the pro-complex; however, this is ruled out by the equivalent dissociation constants for integrin αVβ6 binding to the prodomain (7.6 nM, panel c) and pro-complex (8.2 nM, panel a). Thus, in the absence of force, there is no propagation of conformational change from the integrin binding site to the prodomain:GF interface that lowers affinity for ligand.

The β6 SDL2 backbone is supported by many backbone hydrogen bonds (panel g), correlating with the finding that in the open β6 conformation determined here, SDL2 is essentially identical in backbone to the previous closed conformation bound to the TGF-β3 peptide 5. In contrast, SDL2 in β2 moves, even in intermediate headpiece opening 22.

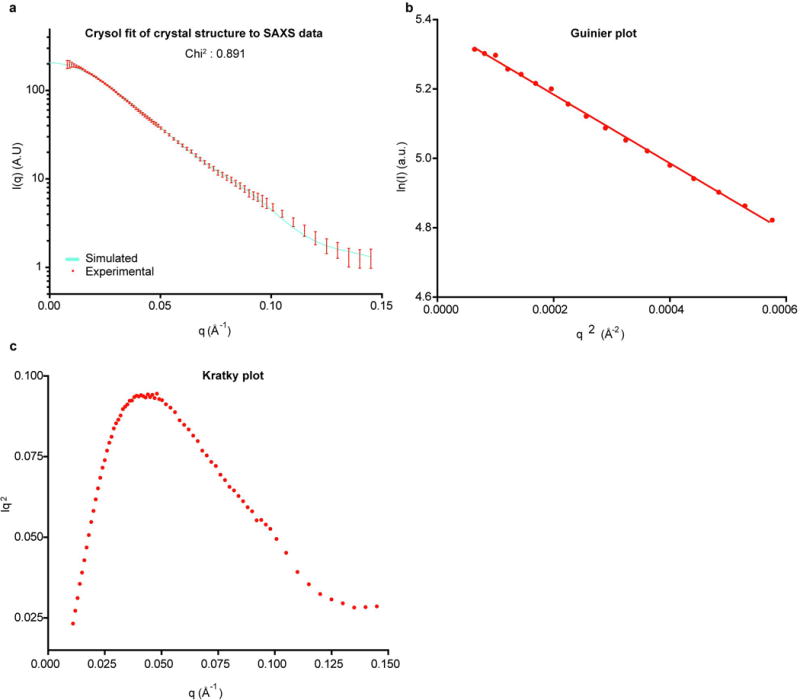

Figure S5. Validation of solution scattering of the 2:1 αVβ6/pro-TGF-β1 complex.

Data are merged from samples at 0.4 and 3 mg/ml. (a) Experimental SAXS scattering of the 2:1 complex in solution (red, with s.d. bars) versus the theoretical SAXS scattering curve calculated with CRYSOL 30 from the crystal structure of the 2:1 complex (cyan). (b) Guinier analysis of the merged data shows a linear fit in the low q region. (c) The Kratky plot exhibits a typical bell-shaped peak.

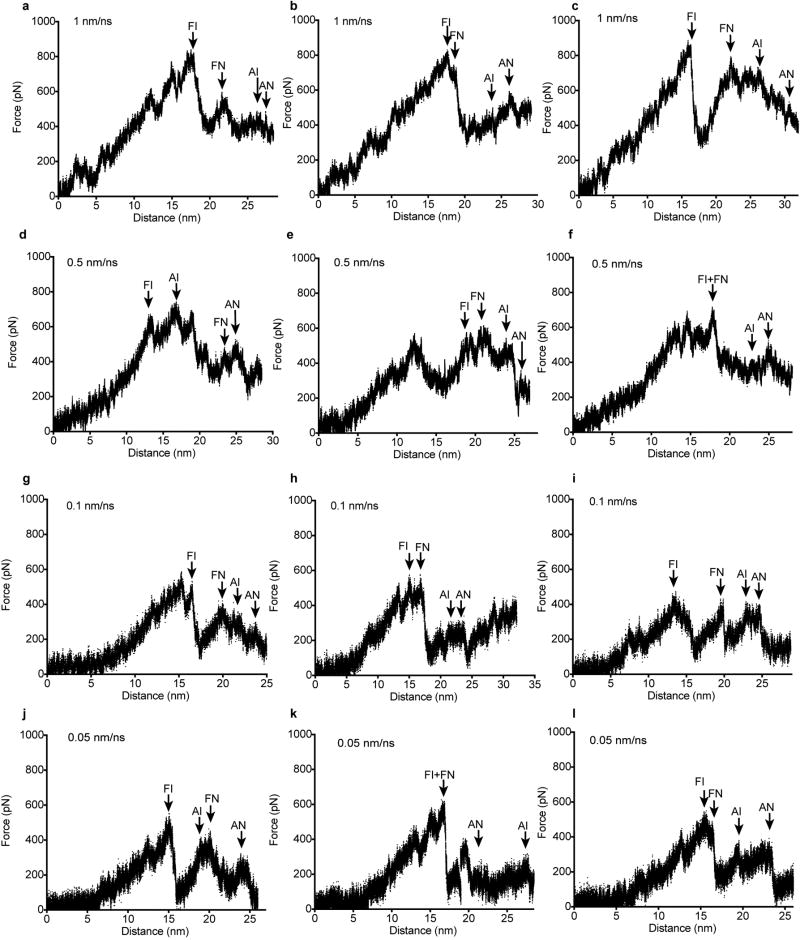

Figure S6. Force spectroscopy in β6 pulling simulations.

(a–l) Force on the harmonic spring at the pulling end was measured every picometer in independent simulations at the indicated pulling rates. The four major events in straitjacket removal are arrowed in each simulation with two-letter codes. The first letter is F for fastener unsnapping and A for α2 helix unfolding. The second letter is I for the integrin-bound monomer and N for the non-bound monomer.

Figure S7. Force spectroscopy in αV pulling simulations.

(a–l) Force on the harmonic spring at the pulling end was measured every picometer in independent simulations at the indicated pulling rates. Pulling failed in each simulation (arrows) owing to thigh domain unfolding (thigh), β-propeller domain unfolding (β-prop) and separation of the αV β-propeller domain from pro-TGF-β1 and the β6 βI domain (αV unbinding).

Supplementary Material

Movies 1–4. Representative simulations. Each simulation shows the beginning structure (rocking), the simulation (no rocking), and concludes with the final structure (rocking). αV and β6 simulations omitted the hybrid and thigh domains, respectively; these domains are added to movies to aid visualization of integrin orientation. (Movie 1) β6 pulling (Extended Data Fig. S6J). (Movies 2–4) αV pulling that terminated with thigh domain unfolding (Movie 2, Extended Data Fig. S7d), β-propeller unfolding (Movie 3, Extended Data Fig. S7j), and αV unbinding (Movie 4, Extended Data Fig. S7l).

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grant R01AR067288, Charles A. King Trust Postdoctoral Research Fellowship Program, Bank of America, N.A., Co-Trustee, and research collaboration with the Waters Corporation. For crystallography, SAXS, and simulations we thank GM/CA-CAT beamline 23-ID at the Advanced Photon Source, beamline X9A at National Synchotron Light Source, and the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center, respectively.

Abbreviations

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-β

- RGD

Arg-Gly-Asp

- MIDAS

Metal ion-dependent adhesion site

- ADMIDAS

adjacent to MIDAS

- SDL

specificity-determining loop

- LTBPs

latent TGF-β binding proteins

- GARP

glycoprotein-A repetitions predominant protein

- LLC

large latent complexes

- LAP

latency associated peptide

- GF

growth factor

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- FITC

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- EM

Electronic microscopy

- SAXS

Small angle X-ray scattering

- HDX MS

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry

Footnotes

Author Contribution T.A.S., X.D., and B.Z. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. B.Z. and X.D. carried out the biochemical studies and crystallization. X.D. performed data collection and structure determination. X.D. and B.Z. performed MD simulation and analysis. B.Z. and A.K. performed the SAXS studies. X.D. and J.Z. performed the EM studies. B.Z., R.E.I., and J.R.E. performed the HDX-MS studies. C.L. participated in the experiment design and data analysis.

References

- 1.Robertson IB, Rifkin DB. Unchaining the beast; insights from structural and evolutionary studies on TGFβ secretion, sequestration, and activation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24:355–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu MY, Hill CS. TGF-β superfamily signaling in embryonic development and homeostasis. Dev. Cell. 2009;16:329–343. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinck AP, Mueller TD, Springer TA. Structural Biology and Evolution of the TGF-β Family. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi M, et al. Latent TGF-β structure and activation. Nature. 2011;474:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature10152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong X, Hudson NE, Lu C, Springer TA. Structural determinants of integrin β-subunit specificity for latent TGF-β. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:1091–1096. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson IB, Rifkin DB. Regulation of the Bioavailability of TGF-β and TGF-β-Related Proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016;8 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwarzbauer JE, DeSimone DW. Fibronectins, their fibrillogenesis, and in vivo functions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3:1–19. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Springer TA, Dustin ML. Integrin inside-out signaling and the immunological synapse. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2012;24:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagae M, et al. Crystal structure of α5β1 integrin ectodomain: Atomic details of the fibronectin receptor. J. Cell Biol. 2012;197:131–140. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong J, et al. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin αVβ3 in complex with an Arg-Gly-Asp ligand. Science. 2002;296:151–155. doi: 10.1126/science.1069040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Agthoven J, et al. Structural basis for pure antagonism of integrin αVβ3 by a high-affinity form of fibronectin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:383–388. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Radford SE, Brockwell DJ. Force-induced remodelling of proteins and their complexes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2015;30C:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke J, Williams PM. In: Protein Folding Handbook Vol. Part 1. Buchner J, Kiefhaber T, editors. Wiley-VCH; 2005. pp. 1111–1142. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mi L-Z, et al. Structure of bone morphogenetic protein 9 procomplex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:3710–3715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501303112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Fischer G, Hyvönen M. Structure and activation of pro-activin A. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sundberg EJ, Mariuzza RA. Molecular recognition in antibody-antigen complexes. Adv. Protein Chem. 2002;61:119–160. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)61004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssens K, et al. Camurati-Engelmann disease: review of the clinical, radiological, and molecular data of 24 families and implications for diagnosis and treatment. J. Med. Genet. 2006;43:1–11. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.033522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nordenfelt P, Elliott HL, Springer TA. Coordinated integrin activation by actin-dependent force during T-cell migration. Nature communications. 2016 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans E, Ritchie K. Strength of a weak bond connecting flexible polymer chains. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2439–2447. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77399-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu J, Zhu J, Springer TA. Complete integrin headpiece opening in eight steps. J. Cell Biol. 2013;201:1053–1068. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201212037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin FY, Zhu J, Eng E, Hudson NE, Springer TA. β-subunit binding is sufficient for ligands to open the integrin αIIbβ3 headpiece. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:4537–4546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.705624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sen M, Yuki K, Springer TA. An internal ligand-bound, metastable state of a leukocyte integrin, αXβ2. J. Cell Biol. 2013;203:629–642. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201308083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang S, Ma J, Peng J, Xu J. Protein structure alignment beyond spatial proximity. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1448. doi: 10.1038/srep01448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konarev PV, Volkov VV, Skolova AV, Koch MH, Svergun DI. PRIMUS: a Windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 2003;36:1277–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eng E, Smagghe B, Walz T, Springer TA. Intact αIIbβ3 extends after activation measured by solution X-ray scattering and electron microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:35218–35226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.275107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abe M, et al. An assay for transforming growth factor-beta using cells transfected with a plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promoter-luciferase construct. Anal. Biochem. 1994;216:276–284. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iacob REB-AGM, Makowski L, Engen JR, Berkowitz SA, Houde D. Investigating monoclonal antibody aggregation using a combination of H/DX-MS and other biophysical measurements. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013;102:4315–4329. doi: 10.1002/jps.23754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wales TE, Engen JR. Hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry for the analysis of protein dynamics. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2006;25:158–170. doi: 10.1002/mas.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou M, et al. A novel calcium-binding site of von Willebrand factor A2 domain regulates its cleavage by ADAMTS13. Blood. 2011;117:4623–4631. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-321596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Svergun DI, Barberato C, Koch MHJ. CRYSOL - a Program to Evaluate X-ray Solution Scattering of Biological Macromolecules from Atomic Coordinates. J. Appl. Cryst. 1995;28:768–773. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movies 1–4. Representative simulations. Each simulation shows the beginning structure (rocking), the simulation (no rocking), and concludes with the final structure (rocking). αV and β6 simulations omitted the hybrid and thigh domains, respectively; these domains are added to movies to aid visualization of integrin orientation. (Movie 1) β6 pulling (Extended Data Fig. S6J). (Movies 2–4) αV pulling that terminated with thigh domain unfolding (Movie 2, Extended Data Fig. S7d), β-propeller unfolding (Movie 3, Extended Data Fig. S7j), and αV unbinding (Movie 4, Extended Data Fig. S7l).

Data Availability Statement

Structural coordinates were deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes 5FFG and 5FFO for the αVβ6 head and αVβ6 head/pro-TGF-β1 1:2 complex, respectively. X-ray diffraction images were deposited in the SBGrid Data Bank with Digital Object Identifier http://dx.doi.org/10.15785/SBGRID/391 (the αVβ6 head) and http://dx.doi.org/10.15785/SBGRID/392 (αVβ6 head/pro-TGF-β1 1:2 complex).