Abstract

A dynamic treatment regime is a sequence of decision rules, each of which recommends treatment based on features of patient medical history such as past treatments and outcomes. Existing methods for estimating optimal dynamic treatment regimes from data optimize the mean of a response variable. However, the mean may not always be the most appropriate summary of performance. We derive estimators of decision rules for optimizing probabilities and quantiles computed with respect to the response distribution for two-stage, binary treatment settings. This enables estimation of dynamic treatment regimes that optimize the cumulative distribution function of the response at a prespecified point or a prespecified quantile of the response distribution such as the median. The proposed methods perform favorably in simulation experiments. We illustrate our approach with data from a sequentially randomized trial where the primary outcome is remission of depression symptoms.

Keywords: Dynamic Treatment Regime, Personalized Medicine, Sequential Decision Making, Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial

1. Introduction

A dynamic treatment regime operationalizes clinical decision making as a series of decision rules that dictate treatment over time. These rules account for accrued patient medical history, including past treatments and outcomes. Each rule maps current patient characteristics to a recommended treatment, hence personalizing treatment. Typically, a dynamic treatment regime is estimated from data with the goal of optimizing the expected value of a clinical outcome, and the resulting regime is referred to as the estimated optimal regime.

Direct-search, also known as policy-search or value-search, is one approach to estimating an optimal dynamic treatment regime. Direct search estimators require a pre-specified class of dynamic treatment regimes and an estimator of the marginal mean outcome under any regime in the pre-specified class. The maximizer of the estimated marginal mean outcome over the class of regimes is taken as the estimator of the optimal dynamic treatment regime. Marginal structural models (MSMs) are one type of direct-search estimators (Robins, 2000; van der Laan et al., 2005; van der Laan, 2006; van der Laan and Petersen, 2007; Bembom and van der Laan, 2008; Robins et al., 2008; Orellana et al., 2010; Petersen et al., 2014). MSMs are best-suited to problems with a small class of potential regimes. MSMs may also be advantageous in practice because optimizing over a small class of pre-specified regimes provides a simpler, and often more interpretable, regime than other approaches. Another class of direct-search estimators casts the marginal mean outcome as a weighted missclassification rate and applies either discrete-optimization or classification algorithms to optimize a plugin estimator of the marginal mean outcome (Zhao et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012b,a, 2013; Zhao et al., 2015).

Regression-based or indirect estimators comprise a second class of estimators of an optimal dynamic treatment regime. Regression-based estimators require a model for some portion of the conditional distribution of the outcome given treatments and covariate information. Examples of regression-based estimators include Q-learning (Watkins, 1989; Watkins and Dayan, 1992; Murphy, 2005a), regularized Q-learning (Moodie and Richardson, 2010; Chakraborty et al., 2010; Song et al., 2015; Goldberg et al., 2013), Interactive Q-learning (Laber et al., 2014a), g-estimation in structural nested mean models (Robins, 2004), A-learning (Murphy, 2003), and regret-regression (Henderson et al., 2010). Nonparametric regression-based approaches often target the globally optimal regime rather than restricting attention to a small, pre-specified class. They can be also be useful in exploratory contexts to discover new treatment strategies for further evaluation in later trials.

Direct-search and regression-based estimators have been extended to handle survival outcomes (Goldberg and Kosorok, 2012; Huang and Ning, 2012; Huang et al., 2014), high-dimensional data (McKeague and Qian, 2013), missing data (Shortreed et al., 2014), multiple outcomes (Laber et al., 2014b; Linn et al., 2015), and restrictions on treatment resource (Luedtke and van der Laan, 2015).

Despite many estimation methods, none are designed to handle functionals of the response distribution other than the mean, such as quantiles. The median response is often of interest in studies where the outcome follows a skewed distribution, such as the total time a women spends in second stage labor (Zhang et al., 2012c). Using the potential outcomes framework (Rubin, 1974; Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1983), Zhang et al. (2012c) develop methods for estimating quantiles of the potential outcomes from observational data. However, they focus on comparing treatments at a single intervention time point rather than estimation of an optimal dynamic treatment regime. Structural nested distribution models (SNDMs) estimated using g-estimation facilitate estimation of point treatment effects on the cumulative distribution function of the outcome (Robins, 2000; Vansteelandt et al., 2014). Thus far, SNDMs have not been extended to estimate a regime that maximizes a quantile.

Q-learning and its variants are often useful when targeting an optimal regime because they provide relatively interpretable decision rules that are based on (typically linear) regression models. However, the Q-learning algorithm is an approximate dynamic programming procedure that requires modeling nonsmooth, nonmonotone transformations of data. This leads to nonregular estimators for parameters that index the optimal regime and complicates the search for models that fit the data well since many standard regression modeling diagnostics are invalid (Robins, 2004; Chakraborty et al., 2010; Laber et al., 2014c; Song et al., 2015). In addition, Q-learning with linear models does not target the globally optimal rule when the true conditional means are nonlinear. Interactive Q-learning (IQ-learning), developed for the two-stage binary treatment setting, requires modeling only smooth, monotone transformations of the data, thereby reducing problems of model misspecification and nonregular inference (Laber et al., 2014a). We extend the IQ-learning framework to optimize function-als of the outcome distribution other than the expected value. In particular, we optimize threshold-exceedance probabilities and quantiles of the response distribution. Furthermore, because this extension of IQ-learning provides an estimator of a threshold-exceedance probability or quantile of the response distribution under any postulated dynamic treatment regime, it can be used to construct direct-search estimators.

Threshold-exceedance probabilities are relevant in clinical applications where the primary objective is remission or a specific target for symptom reduction. For example, consider a population of obese patients enrolled in a study to determine the effects of several treatment options for weight loss. The treatments of interest may include combinations of drugs, exercise programs, counseling, and meal plans (Berkowitz et al., 2010). Our method can be used to maximize the probability that patients achieve a weight below some prespecified, patient-specific threshold at the conclusion of the study. Optimization of threshold-exceedance probabilities can be framed as a special case optimizing the mean of a binary outcome, for which several methods exist, including the classification-based Outcome Weighted Learning (Zhang et al., 2012b; Zhao et al., 2015). However, our approach is particularly useful for setting up the more challenging problem of quantile optimization.

With adjustments to our method of maximizing probabilities, we derive optimal decision rules for maximizing quantiles of the response distribution. Both frameworks can be used to study the entire distribution of the outcome under an optimal dynamic treatment regime; thus, investigators can examine how the optimal regime changes as the target probability or quantile is varied. In addition, the quantile framework provides an analog of quantile regression in the dynamic treatment regime setting for constructing robust estimators; for example, it enables optimization of the median response.

2. Generalized Interactive Q-Learning

We first characterize the optimal regime for a probability and quantile using potential outcomes (Rubin, 1974) and two treatment time-points. We assume that the observed data, , comprise n independent, identically distributed, time-ordered trajectories; one per patient. Let (X1, A1, X2, A2, Y) denote a generic observation where: X1 ∈ ℝp1 is baseline covariate information collected prior to the first treatment; A1 ∈ {−1, 1} is the first treatment; X2 ∈ ℝp2 is interim covariate information collected during the course of the first treatment but prior the second treatment; A2 ∈ {−1, 1} is the second treatment; and Y ∈ ℝ is an outcome measured at the conclusion of stage two, coded so that larger is better. Define H1 = X1 and so that Ht is the information available to a decision maker at time t. A regime, π = (π1, π2), is a pair of decision rules where πt : dom(Ht) ↦ dom(At), such that a patient presenting with Ht = ht at time t is recommended treatment πt(ht).

Let be the potential second-stage history under treatment a1 and Y*(a1, a2) the potential outcome under treatment sequence (a1, a2). Define the set of all potential outcomes . Throughout we assume: (C1) consistency, so that Y = Y*(A1, A2); (C2) sequential ignorability (Robins, 2004), i.e., At ╨ W | Ht for t = 1, 2; and (C3) positivity, so that there exists ε > 0 for which ε < pr(At = at|Ht) < 1 – ε with probability one for all at, t = 1, 2. Assumptions (C2)-(C3) hold by design when data are collected using a sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART, Lavori and Dawson, 2000, 2004; Murphy, 2005b). In observational studies, these assumptions are not testable. We assume that data are collected using a two-stage, binary treatment SMART. This set-up facilitates a focused discussion of the proposed methods and is also useful in practice, as data in many sequentially randomized trials have this structure (Projects Using SMART, 2012; Laber, 2013). However, the following argument demonstrates that the proposed methodology can be extended to observational data and studies with more than two treatments.

For any π define to be the potential outcome under π. Define the function R(y; x1, a1, x2, a2) = pr(Y > y|X1 = x1, A1 = a1, X2 = x2, A2 = a2) for any y ∈ ℝ. Assuming (C1)-(C3) and y ∈ ℝ, the survival function of Y*(π) can be expressed in terms of the underlying generative model as

for any π (Robins, 1986). This result shows that pr{Y*(π) > y} is maximized by the regime , where and . This result can also be used to characterize the regime that optimizes a quantile. For any regime π, pr{Y*(πy) ≤ y} ≤ pr{Y*(π) ≤ y} implies inf{y : pr{Y*(πy) ≤ y} ≥ τ} ≥ inf{y : pr{Y*(π) ≤ y} ≥ τ}. In fact the left-hand side is the optimal τth quantile; denote it by . An optimal regime with respect to the τth quantile is thus any regime that, when used to assign treatments in the population, results in a τth quantile that attains . The following result is proved in the supplemental material.

Theorem 2.1. Let ε > 0 and τ ∈ (0, 1) be arbitrary but fixed. Assume (C1)-(C3) and that the map y ↦ R(y; x1, a1, x2, a2) from ℝ into (0, 1) is continuous and strictly increasing in a neighborhood of τ for all x1, a1, x2, and a2. Then, .

Theorem 2.1 states that the regime induces a τth quantile of the potential outcome distribution that attains the optimal τth quantile. Without the strictly increasing assumption, may not be optimal. However, it can be shown that there exists a value ỹ ∈ ℝ such that the regime πỹ attains a τth quantile that is arbitrarily close to . Details are given in Section 3.

2.1 Threshold Interactive Q-learning

The estimators presented in this section serve as useful building blocks for developing the estimators in the next section which focus on quantile optimization. Here, we derive and estimate the optimal set of decision rules for maximizing a threshold-exceedance probability. Let prπ(Y > λ), equivalently prπ1, π2(Y > λ), denote the probability that the outcome Y is greater than a predefined threshold λ under treatment assignment dictated by the regime π = (π1, π2). Threshold Interactive Q-learning (TIQ-learning) maximizes prπ{Y > λ(Ht) | H1} for all H1 with respect to π, where λ(Ht) is a threshold that depends on Ht, t = 1, 2. Here, we assume λ(Ht) ≡ λ; patient-specific thresholds are discussed in the supplemental material.

As prπ(Y > λ) = Eπ(𝟙Y>λ), many approaches exist for estimating an optimal regime that maximizes the value function of the binary outcome 𝟙Y>λ; one example is discrete Q-learning (Chakraborty and Moodie, 2013). We show analytically in Remark 2.4, and empirically in Section 4, that discrete Q-learning using the logit link is equivalent to Q-learning with outcome Y and is therefore insensitive to the threshold λ. Nonparametric methods such as OWL (Zhao et al., 2012) double-robust direct search (Zhang et al., 2012b,a, 2013), and boosting (Kang et al., 2014) are less restrictive than model-based approaches for optimizing binary outcomes, but the following exposition facilitates later developments for optimizing quantiles.

Our estimators are derived under the following set-up. Because A2 is binary, there exist functions m and c such that E(Y | A2, H2) = m(H2) + A2c(H2). We assume that Y = E(Y | A2, H2) + ε, where E(ε) = 0, Var(ε) = σ2, and ε is independent of (A2, H2). In the supplemental material we describe extensions to: (i) heteroskedastic error structures, where Y = E(Y | A2, H2) + σ(H2, A2)ε for unknown function σ; and (ii) non-additive error structures such as the multiplicative error model, Y = ε[m(H2) + A2c(H2)], provided ε > 0 with probability one and pr{m(H2) + A2c(H2) = 0} = 0.

Define FH1(·) to be the distribution of H1; FH2|H1, A1(· | h1, a1) to be the conditional distribution of H2 given H1 = h1 and A1 = a1; Fε(·) to be the distribution of ε; and . Let , then

| (1) |

is the expected value of Jπ1, π2(H1, H2, y).

Let , where sgn(x) = 𝟙x≥0 – 𝟙x<0. Then, and for all implies

| (2) |

where the right-hand side of (2) is . Let G(·, · | h1, a1) denote the joint conditional distribution of m(H2) and c(H2) given H1 = h1 and A1 = a1, then , where

| (3) |

The λ-optimal regime satisfies for all π. That is, the distribution of Y induced by regime has at least as much mass above λ as the distribution of Y induced by any other regime. It follows from the lower bound on prπ1, π2(Y ≤ y) displayed in (2) that for all h2, independent of λ and . Henceforth, we denote by . The relationship

| (4) |

shows that the λ-optimal first-stage rule is . Inequality (4) holds because I{λ, Fε(·), G(·, · | H1, a1)} is minimized over a1 for all H1. It will be useful later on to write where

| (5) |

Below, we describe the general form of the TIQ-learning algorithm that can be used to estimate the λ-optimal regime. The exact algorithm depends on the choice of estimators for m(H2), c(H2), Fε(·) and G(·, · | h1, a1). For example, one might posit parametric models, m(H2; β2,0) and c(H2; β2,1), for m(H2) and c(H2) and estimate the parameters in the model Y = m(H2; β2,0) + c(H2; β2,1) + ε using least squares. Alternatively, these terms could be estimated nonparametrically. We discuss possible estimators for Fε(·) and G(·, ·| h1, a1) in Sections 3.1 and 3.2. In practice, the choice of estimators should be informed by the observed data. Finally, we emphasize that if the binary threshold outcome is the terminal focus, rather than quantile optimization, a different approach (e.g., nonparametric or direct search) may be warranted. The following algorithm provides a foundation for the quantile optimization algorithm in the next section. Define d̂(h1, λ) = I{λ, F̂ε(·), Ĝ(·, · | h1, −1)} – I{λ, F̂ε(·), Ĝ(·, · | h1, 1)}.

TIQ-learning algorithm

TIQ.1 Estimate m(H2) and c(H2), and denote the resulting estimates by m̂(H2) and ĉ(H2). Given h2, estimate using the plug-in estimator .

TIQ.2 Estimate Fε(·), the cumulative distribution function of ε, using the residuals êY = Y – m̂(H2) – A2ĉ(H2) from TIQ.1. Let F̂ε(·) denote this estimator.

TIQ.3 Estimate G(·, · | h1; a1), the joint conditional distribution of m(H2) and c(H2) given H1 = h1 and A1 = a1. Let Ĝ(·, · | h1, a1) denote this estimator.

TIQ.4 Given h1, estimate using the plug-in estimator .

The TIQ-learning algorithm involves modeling m(H2), c(H2), the distribution function Fε(·), and the bivariate conditional density G(·, · | h1, a1). This is more modeling than some mean-targeting algorithms. For example, Q-learning requires modeling m(H2), c(H2), and the conditional mean of m(H2) + |c(H2)| given H1, A1, while IQ-learning requires modeling m(H2), c(H2), the conditional mean of m(H2), and the conditional density of c(H2) (Laber et al., 2014a). We discuss models for the components of the TIQ-learning algorithm in Sections 3.1 and 3.2.

Remark 2.2. Standard trade-offs between parametric and nonparametric estimation apply to all terms in the TIQ-learning algorithm. In practice, the choice of estimators will likely depend on sample size and the scientific goals of the study. If the goal is to estimate a regime for immediate decision support in the clinic, then the marginal mean outcome of the estimated regime is of highest priority. Given sufficient data, it may be desirable to use nonparametric estimators in this context. However, if the goal is to inform future research and generate hypotheses for further investigation, then factors like parsimony, interpretability, and the ability to identify and test for factors associated with heterogeneous treatment response may be most important. In this context, parametric models may be preferred for components of the TIQ-learning algorithm, namely, the treatment interaction term c(H2), while more flexible models may be specified for the nuisance function m(H2). A parsimonious, parametric model for c(H2) trades a restriction on the class of possible regimes for potential gains in interpretability. Note that approaches such as OWL (Zhao et al., 2012) and the methods described in Luedtke and van der Laan (2015) do not require models for m(H2), while double robust approaches model this term only to increase efficiency and remain consistent for the optimal regime even when the model is misspecified.

Remark 2.3. Let denote the first-stage decision rule of an optimal regime for the mean of Y. Then, assuming the set-up of Section 2.1, it can be shown that

whereas . If Fε(·) is approximately linear where the conditional distribution of λ – m(H2) – |c(H2)| given H1 = h1 and A1 = a1 is concentrated, and will likely agree. Thus, the difference between the mean optimal and TIQ-learning optimal regimes can be compared empirically by computing arg mina1 ∫(−u – |v|)dĜ(u, v | h1i, a1), arg mina1 ∫ F̂ε(λ – u – |v|)dĜ(u, v | h1i, a1), for each first-stage patient history h1i, i = 1, …, n, and examining where these rules differ.

Remark 2.4. One approach to estimating an optimal decision rule for threshold-exceedance probabilities is discrete Q-learning (Chakraborty and Moodie, 2013). Suppose Y = m*(H2)+A2c*(H2) + ε, where ε has cumulative distribution function Fε(·). For the binary outcome 𝟙Y>λ, define the second-stage Q-function, Q2(H2, A2) = pr(𝟙Y>λ = 1 | H2, A2), and the first stage Q-function, Q1(H1, A1) = 𝔼[maxa2 Q2(H2, a2) | H1, A1]. If these functions were known, the optimal treatment assignments for the set of observed histories (H1 = h1, H2 = h2) would be {arg maxa1 Q1(h1, a1), arg maxa2 Q2(h2, a2)}. In practice, the Q-functions are unknown and the Q-learning algorithm proceeds by specifying models for them. Denote estimates of the Q-functions obtained from such models by Q̂2(H2, A2) and Q̂1(H1, A1). Then, the estimated optimal treatment assignments for (H1 = h1, H2 = h2) are {arg maxa1 Q̂1(h1, a1), arg maxa2 Q̂2(h2, a2)}. For binary outcomes, logistic regression is often a natural model choice for Q2. Subsequently, at the first stage one would specify a model for 𝔼[maxa2 Q̂2(H2, a2) | H1, A1], where the pseudo outcome maxa2 Q̂2(H2, a2) is bounded in [0, 1]. Rather than modeling this conditional expectation with linear regression, which may result in Q̂1 estimates outside the interval [0, 1], an alternative is to model 𝔼[maxa2 logit{Q̂2(H2, a2)} | H1, A1] using linear regression, since maxa2 logit{Q̂2(H2, a2)} takes values on the real line (Chakraborty and Moodie, 2013; Moodie et al., 2014). However, for our special case of discrete Q-learning with outcome 𝟙Y>λ, the logit link function is misspecified for pr(𝟙Y>λ = 1 | H2, A2). The correct link function for the second stage Q-function is . When the logit link is used rather than L(u), discrete Q-learning as described above and Q-learning for the continuous outcome Y perform similarly across all values of λ for the generative model for Y given above. We demonstrate this using simulation experiments in Section 4.

3. Quantile Interactive Q-Learning

Under some generative models, assigning treatment according to a mean-optimal regime leads to higher average outcomes at the expense of higher variability, negatively affecting patients with outcomes in the lower quantiles of the induced distribution of Y. We demonstrate this using simulated examples in Section 4. Define the τth quantile of the distribution of Y induced by regime π as qπ(τ) = inf{y : prπ1,π2(Y ≤ y) ≥ τ}. The goal of Quantile Interactive Q-learning (QIQ-learning) is to estimate a pair of decision rules, , that maximize qπ(τ) over π for a fixed, prespecified τ. QIQ-learning is similar to TIQ-learning, but the optimal first-stage rule is complicated by the inversion of the distribution function to obtain quantiles of Y under a given regime. When the variance of Y is independent of A2, the QIQ-learning second-stage optimal decision is , independent of τ and ; details are provided in Section 4 of the supplemental material. Denote by .

Next we characterize , which will motivate an algorithm for calculating it. Let d(h1, y) be as in (5), and define Γ(h1, y) ≜ sgn{d(h1, y)}. Then is the optimal first-stage decision rule of TIQ-learning at λ = y. We have introduced the new notation to emphasize the dependence on y. Next, define the optimal τth quantile

| (6) |

which we study further in the remainder of this section.

Lemma 7.7 of the supplemental material proves that , so that is defined for all τ ∈ (0, 1). For each y ∈ ℝ,

where I(·, ·, ·) is defined in (3). The last equality follows because Γ(H1, y) minimizes E (I [y, Fε(·), G{·, ·|H1, a1}]) with respect to a1. Hence, , and taking the infimum on both sides gives the upper bound

| (7) |

Thus, a first-stage decision rule π1 is optimal if it induces a τth quantile equal to the upper bound when treatments are subsequently assigned according to , i.e., if .

We now discuss conditions that guarantee existence of a π1 such that and derive its form. The quantile obtained under regime is

| (8) |

Thus, because it is a quantile and the bound in (7) applies, , and for all y. Our main results depend on the following lemma, which is proved in the supplemental material.

Lemma 3.1.

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

It follows from (B) that if and only if f(y) is left continuous at , and part (D) is a sufficient condition guaranteeing left-continuity of f(y) at . In this case, the optimal first-stage rule is , i.e., . The condition stated in (D) is commonly satisfied, e.g., when the density of ε has positive support on the entire real line. If f(y) is not left continuous at , and thus , in light of (10) we can always approach the optimal policy via a sequence of regimes of the form { }, where δn decreases to 0. If the underlying distributions of the histories and Y were known, the following algorithm produces an optimal regime.

Population-level algorithm to find

- If , is optimal as it attains the quantile .

- If , is optimal. Note that this rule can be written in closed form as , where we define and .

In practice, the generative model is not known, but the population-level algorithm suggests an estimator of . The following QIQ-learning algorithm can be used to estimate an optimal first-stage decision rule. The exact algorithm depends on the choice of estimators for Fε(·) and G(·, · | h1, a1); several options are presented in Sections 3.1 and 3.2, but the choice should be data-driven; see, e.g., Remark 2.2.

QIQ-learning algorithm

QIQ.1 Follow TIQ.1 – TIQ.3 of the TIQ-learning algorithm in Section 2.1.

- QIQ.2 With I(·, ·, ·) as in (3) and first-stage patient histories h1i, estimate using

- QIQ.3 Estimate using

- QIQ.4

- If , then is an estimated optimal first-stage decision rule because it attains the estimated optimal quantile, , when treatments are subsequently assigned according to at the second stage.

- If , then the first-stage rule , δ > 0, results in the estimated quantile , which satisfies . By choosing δ arbitrarily small, this estimated quantile will be arbitrarily close to the estimated optimal quantile .

To complete the TIQ- and QIQ-learning algorithms, we provide specific estimators Fε(·) and G(·, · | h1, a1) in the next two sections. We suggest estimators that are likely to be useful in practice, but our list is not exhaustive. An advantage of TIQ- and QIQ-learning is that they involve modeling only smooth transformations of the data; these are standard, well-studied modeling problems in the statistics literature.

3.1 Working models for Fε(·)

Both TIQ- and QIQ-learning require estimation of the distribution function of the second-stage error, ε. We suggest two estimators that are useful in practice. The choice between them can be guided by inspection of the residuals from the second-stage regression.

Normal Scale Model

The normal scale estimator for Fε(·) is , where Φ(·) denotes the standard normal distribution function and σ̂ε is the standard deviation of the second-stage residuals, , i = 1, …, n. If it is thought that σε depends on (H2, A2), flexibility can be gained by assuming a heteroskedastic variance model (Carroll and Ruppert, 1988), i.e., by assuming Fε(z) = Φ{z/σε(H2, A2)} for some unknown function σε(h2, a2). Given an estimator σ̂ε(h2, a2) of σε(h2, a2), an estimator of Fε(·) is . We discuss variance modeling techniques in the next section.

Nonparametric Model

For more flexibility, a non- or semi-parametric estimator for Fε(·) can be used. In the homogeneous variance case, a nonparametric estimator of Fε(·) is the empirical distribution of the residuals, . In the heterogeneous variance case, one can assume a non- or semi-parametric scale model Fε|H2,A2(z|H2 = h2, A2 = a2) = F0{z/σε(h2, a2)}, where F0(·) is an unspecified distribution function. Given an estimator σ̂ε(h2, a2) of σε(h2, a2), an estimator of Fε|H2,A2(z|H2 = h2, A2 = a2) is , where . Standard residual diagnostic techniques, e.g., a normal quantile-quantile plot, can be used to determine whether a normal assumption seems plausible for the observed data.

3.2 Working models for G(·, ·|h1, a1)

In addition to a model for Fε(·), TIQ- and QIQ-learning require models for the bivariate conditional density of m(H2) and c(H2) given H1 and A1. A useful strategy is to first model the conditional mean and variance functions of m(H2) and c(H2) and then estimate the joint distribution of their standardized residuals. Define these standardized residuals as

where μm(H1, A1) ≜ E{m(H2) | H1, A1} and . The mean and variance functions of c(H2) are defined similarly: μc(H1, A1) ≜ E{c(H2)|H1, A1}, and . In simulations, we use parametric mean and variance models for μm, , μc, and , and we estimate the joint distribution of em and ec using a Gaussian copula. Alternatively, the joint residual distribution could be modelled parametrically, e.g., with a multivariate normal model; or nonparametrically, e.g., using a bivariate kernel density estimator (Silverman, 1986, Ch. 4). The Gaussian copula is used in the simulations in Section 4, and results are provided using a bivariate kernel estimator in the supplemental material. Common exploratory analysis techniques can be used to interactively guide the choice of estimator for G(·, · | h1, a1). In simulated experiments described in the supplemental material, a bivariate kernel density estimator was competitive with a correctly specified Gaussian copula model with sample sizes as small as n = 100. Using parametric mean and variance modeling, the following steps would be substituted in Step TIQ.3 of the TIQ-learning algorithm.

Mean and Variance Modeling

3.1 Compute and the resulting estimator μm(H1, A1; θ̂m) of the mean function μm(H1, A1).

-

3.2 Use the estimated mean function from Step 3.1 to obtain

and subsequently the estimator of . One choice for σm(h1, a2; γm) is a log-linear model, which may include non-linear basis terms.

3.3 Repeat Steps 3.1 and 3.2 to obtain estimators μc(H1, A1; θ̂c) and σc(H1, A1; γ̂c).

-

3.4 Compute standardized residuals and , i = 1, …, n, as

Then, and , i = 1, …, n, can be used to estimate the joint distribution of the standardized residuals. Samples drawn from this distribution can be transformed back to samples from Ĝ(·, · | h1, a1) to estimate the integral I{y, F̂ε(·), Ĝ(·, · | h1, a1)} with a Monte Carlo average.

3.3 Theoretical results

The following assumptions are used to establish consistency of the threshold exceedance probability and quantile that result from applying the estimated TIQ- and QIQ-learning optimal regimes, respectively. For each h1, a1, and h2:

A1. the method used to estimate m(·) and c(·) results in estimators m̂(h2) and ĉ(h2) that converge in probability to m(h2) and c(h2), respectively;

A2. Fε(·) is continuous, F̂ε(·) is a cumulative distribution function, and F̂ε(y) converges in probability to Fε(y) uniformly in y;

A3. ∫|dĜ(u, v | h1, a1) – dG(u, v | h1, a1)| converges to zero in probability;

A4. converges to zero in probability.

In the simulation experiments in Section 4 and data example in Section 5, we use linear working models for m(·) and c(·) that are estimated using least squares. Thus, A1 is satisfied under usual regularity conditions. When ε is continuous, assumption A2 can be satisfied by specifying F̂ε(·) as the empirical distribution function. If for each fixed h1 and a1, dG(·, · | h1, a1) is a density and dĜ(·, · | h1, a1) a pointwise consistent estimator, then A3 is satisfied (Glick, 1974). Theorems 3.2 and 3.3 are proved in the supplemental material.

Theorem 3.2. (Consistency of TIQ-learning) Assume A1–A3 and fix λ ∈ ℝ. Then, converges in probability to , where .

Theorem 3.3. (Consistency of QIQ-learning) Assume A1–A4. Then, converges in probability to for any fixed τ, where .

4. Simulation Experiments

We compare the performance of our estimators to binary Q-learning (Chakraborty and Moodie, 2013), Q-learning, and mean-optimal IQ-learning (Laber et al., 2014a) for a range of data generative models. Gains are achieved in terms of the proportion of the distribution of Y that exceeds the constant threshold λ and the τth quantile for several values of λ and τ. The data are generated using the model

where 1p is a p × 1 vector of 1s, Iq is the q × q identify matrix, and C ∈ [0,1] is a constant. The matrix Σ is a correlation matrix with off-diagonal ρ = 0.5. The 2 × 2 matrix BA1 equals

The remaining parameters are γ0 = (1, 0.5, 0)T, γ1 = (−1, −0.5, 0)T, β2,0 = (0.25, −1, 0.5)T, and β2,1 = (1, −0.5, −0.25)T, which were chosen to ensure that the mean-optimal treatment produced a more variable response for some patients.

4.1 TIQ-learning Simulation Results

Results are based on J = 1,000 generated data sets. For each, we estimate the TIQ-, IQ-, binary Q-learning, and Q-learning policies using a training set of size n = 250 and compare the results using a test set of size N = 10, 000. The normal scale model is used to estimate Fε(·), which is correctly specified for the generative model above. The Gaussian copula model discussed in Section 2.4 is also correctly specified and is used as the estimator for G(·, · | h1, a1). Results using a bivariate kernel estimator for G(·, · | h1, a1) are presented in the supplemental material.

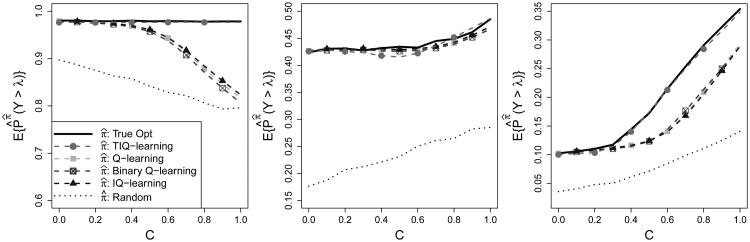

To study the performance of the TIQ-learning algorithm, we compare values of the cumulative distribution function of the final response when treatment is assigned according to the estimated TIQ-learning, IQ-learning, binary Q-learning, and Q-learning regimes. Define prπ̂j(Y > λ) to be the true probability that Y exceeds λ given treatments are assigned according to π̂j = (π̂1j, π̂2j), the regime estimated from the jth generated data set. For threshold values λ = −2, 2, 4, we estimate prπ(Y > λ) using , where pr̂π̂j(Y > λ) is an estimate of prπ̂j(Y > λ) obtained by calculating the proportion of test patients consistent with regime π̂j whose observed Y values are greater than λ. Thus, our estimate is an average over training data sets and test set observations. In terms of the proportion of distribution mass above λ, results for λ = −2 and 4 in Figure 1 show a clear advantage of TIQ-learning for higher values of C, the degree of heteroskedasticity in the second-stage covariates X2. As anticipated by Remark 2.3 in Section 2.1, all methods perform similarly when λ = 2.

Figure 1.

Left to Right: λ = −2, 2, 4. Solid black, true optimal threshold probabilities; dotted black, probabilites under randomization; dashed with circles/squares/crossed squares/triangles, probabilities under TIQ-, Q-, binary Q-, and Interactive Q-learning, respectively.

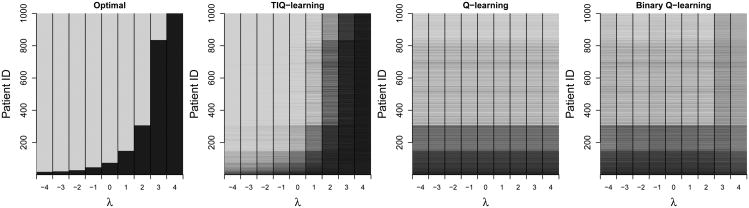

Figure 2 illustrates how the optimal first-stage treatment for a test set of 1,000 individuals changes as λ varies. Results are shown for C = 0.5. The true optimal treatments displayed in the left plot show a distinct shift from treating most of the population with A1 = 1 to A1 = −1 as λ increases from -4 to 4. The TIQ-learning estimated optimal treatments displayed in the middle plot are averaged over 100 Monte Carlo iterations and closely resemble the true policies on the left. Although the estimated Q-learning regime does not depend on λ, it is plotted for each λ value to aid visual comparison. The first-stage treatments recommended by Q-learning differ the most from the true optimal treatments when λ = 4, corroborating the results for C = 0.5 in Figure 1. The rightmost panel of Figure 2 are the results from binary Q-learning with the binary outcome defined as 𝟙Y>λ. While there appears to be a slight deviation in the results from mean-optimal Q-learning for λ values 3 and 4, overall the resulting policies are similar to mean-optimal Q-learning and do not recover the true optimal treatments on average.

Figure 2.

From left: True optimal first-stage treatments for 1,000 test set patients when λ = −4, −3, …, 4, coded light gray when and dark gray otherwise; TIQ-learning estimated optimal first-stage treatments; Q-learning estimated optimal first-stage treatments, plotted constant in λ to aid visual comparison; and binary Q-learning estimated optimal first-stage treatments for each λ.

4.2 QIQ-learning Simulations

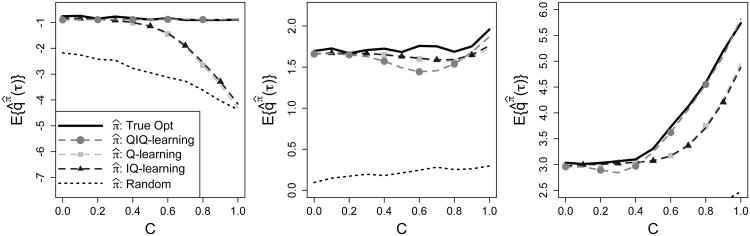

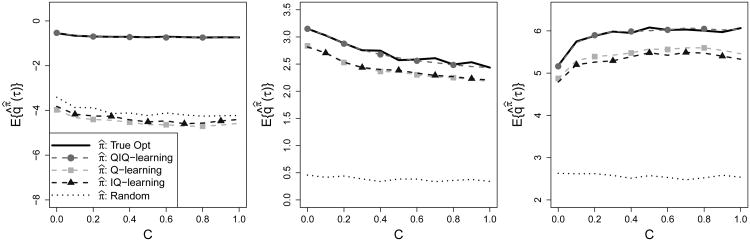

To study the performance of the QIQ-learning algorithm, we compare quantiles of Y when the population is treated according to the regimes estimated by QIQ-learning, IQ-learning, and Q-learning. A smaller test set of size N = 5,000 was used in this section to reduce computation time. Define qπ̂j (τ) to be the true τth quantile of the distribution of Y given treatments are assigned according to π̂j = (π̂1j, π̂2j), the regime estimated from the jth generated data set. For τ = 0.1, 0.5, 0.75, we estimate qπ(τ) using , where q̂π̂j(τ) is an estimate of qπ̂j(τ) obtained by calculating the τth quantile of the subgroup of test patients consistent with regime π̂j. The generative model and all other parameter settings used here are the same as those in the previous section. For our generative model, the condition of Lemma 3.1 is satisfied, so the true optimal regime is attained asymptotically. The results in Figure 3 indicate that the lowest quantile, τ = 0.1, suffers under the Q-learning regime as heterogeneity in the second-stage histories increases, measured by the scaling constant C. In contrast, quantiles of the QIQ-learning estimated regimes for τ = 0.1 remain constant across the entire range of C. When τ = 0.5, all methods perform similarly; for some C, IQ- and Q-learning outperform QIQ-learning. This is not surprising because all models used to generate the data were symmetric. Thus, maximizing the mean of Y gives similar results to maximizing the median.

Figure 3.

Left to Right: τ = 0.1, 0.5, 0.75. Solid black, true optimal quantiles; dotten black, quantiles under randomization; dashed with circles/squares/triangles, quantiles under QIQ-, Q-, and IQ-learning, respectively.

Next we study QIQ-learning when the first stage errors are skewed. The generative model and parameter settings used here are the same as those used previously except that

where C ∈ [0, 1] is a constant that reflects the degree of skewness in the first-stage errors, ξ. Smaller values of C correspond to heavier skew.

Results are averaged over J = 100 generated data sets; for each, we estimate the QIQ-, IQ-, and Q-learning policies and compare the results using a test set of size N = 10, 000. The training sample size for each iteration is n = 500. The normal scale model is used to estimate Fε(·), which is correctly specified. A bivariate kernel density estimator is used to estimate G(·, · | h1, a1). As before, we compare quantiles of the final response when treatment is assigned according to the estimated QIQ-learning, IQ-learning, and Q-learning regimes, and the results are given in Figure 4. QIQ-learning demonstrates an advantage over the mean-optimal methods for all three quantiles and almost uniformly across the degree of skewness of the first-stage errors.

Figure 4.

Left to Right: τ = 0.1,0.5,0.75. Solid black, true optimal threshold probabilities; dotted black, probabilites under randomization; dashed with circles/squares/triangles, probabilities under TIQ-, Q-, and Interactive Q-learning, respectively. Training set size of n = 500.

5. Star*D Analysis

The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial (Fava et al., 2003; Rush et al., 2004) is a four-stage Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (Lavori and Dawson, 2004; Murphy, 2005a) studying personalized treatment strategies for patients with major depressive disorder. Depression is measured by the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS) score, a one-number summary score that takes integer values 0 to 27. Lower scores indicate fewer depression symptoms. Remission is defined as QIDS ≤ 5. Previous attempts to estimate optimal dynamic treatment regimes from this data have used the criteria, “maximize end-of-stage-two QIDS,” (see, for example, Schulte et al., 2012; Laber et al., 2014a) a surrogate for the primary aim of helping patients achieve remission. We illustrate TIQ-learning by estimating an optimal regime that maximizes the probability of remission for each patient, directly corresponding to the primary clinical goal.

The first stage, which we will henceforth refer to as baseline, was non-randomized with each patient receiving Citalopram, a drug in the class of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs). We use a subset of the STAR*D data from the first two randomized stages, and refer to the original trial levels 2 and 3 as “stage one” and “stage two.” Before each randomization, patients specified a preference to “switch” or “augment” their current treatment strategy and were then randomized to one of multiple options within their preferred category. In addition, patients who achieved remission in any stage exited the study. To keep our illustration of TIQ-learning concise, we restrict our analysis to the subset of patients who who preferred the “switch” strategy at both stages. We note that this subgroup is not identifiable at baseline because patient preferences depend on the assigned treatment and subsequent response at each stage. Our motivation for this restriction is to mimic a two-stage SMART where treatments are randomized at both stages, thus simplifying our illustration. At stage one, our binary treatment variable is “SSRI,” which includes only Sertraline, versus “non-SSRI,” which includes both Bupropion and Venlafaxine. At stage two we compare Mirtazapine and Nortriptyline which are both non-SSRIs. In the patient subgroup considered in our analysis, treatments were randomized at both stages.

All measured QIDS scores are recoded as 27– QIDS so that higher scores correspond to fewer depression symptoms. After recoding, remission corresponds to QIDS > 21. Thus, TIQ-learning with λ = 21 maximizes the probability of remission for all patients. In general, QIDS was recorded during clinic visits at weeks 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12 in each stage, although some patients with inadequate response moved on to the next stage before completing all visits. We summarize longitudinal QIDS trajectories from the baseline stage and stage one by averaging over the total number of QIDS observations in the given stage. Variables used in our analysis are listed in Table 1. We describe all models used in the analysis below.

Table 1.

Variables used in the STAR*D analysis.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| qids0 | mean QIDS during the baseline stage. |

| slope0 | pre-randomization QIDS improvement; the difference between the final and initial baseline-stage QIDS scores, divided by time spent in the baseline stage. |

| qids1 | mean stage-one QIDS. |

| slope1 | first-stage QIDS improvement; the difference between the final and initial first-stage QIDS scores, divided by time spent in the first randomized stage. |

| A1 | First-stage treatment; 1=“SSRI” and -1=“non-SSRI.” |

| A2 | Second-stage treatment; 1=“NTP” for Nortriptyline and -1=“MIRT” for Mirtazapine. |

| Y | 27 minus final QIDS score, measured at the end of stage two. |

At the second stage, we assume the linear working model , where H2,0 = H2,1 = (1, qids1, slope1, A1)T, E(ε) = 0, var(ε) = σ2, and ε is independent of H2 and A2. We fit this model using least squares. A normal qq-plot of the residuals from the previous regression step indicates slight deviation from normality, so we use the non-parametric estimator of Fε(·) given in Section 2.4. Next, we estimate the conditional mean and variance functions of and following steps described in Section 2.4. For the mean functions, we take with X1 = (qids0, slope0)1 and use working models of the form . Exploratory analyses reveal little evidence of heteroskedasticity at the first-stage. Thus, we opt to estimate a constant residual variance for both terms following the mean modeling steps. After the mean and variance modeling steps, we use a Gaussian copula to estimate the joint conditional distribution of the standardized residuals of {m(H2), c(H2)} given H1 and A1, resulting in our estimate of G(·, · | h1, a1) which we denote by Ĝ(·, · | h1, a1).

The estimated first-stage optimal rule is . At stage two, is the estimated optimal treatment. Based on Remark 1 in Section 2.1, we compare the estimated first-stage treatment recommendations to those recommended by the mean-optimal rule, arg mina1 ∫(−u – |v|)dĜ(u, v | h1, a1), for each observed h1 in the data. Only one patient out of 132 is recommended differently. In addition, the difference in raw values of ∫F̂ε(21 – u – |v|)dĜ(u, v | h1, a1) for a1 = 1, −1 as well as ∫(−u – |v|)dĜ(u, v | h1, a1) for a1 = 1, −1 are the smallest for this particular patient. Thus, the treatment discrepancy is most likely due to a near-zero treatment effect for this patient.

We compare TIQ-learning to the Q-learning analysis of Schulte et al. (2012) and binary Q-learning (Chakraborty and Moodie, 2013). Comparing the results to Q-learning, which maximizes the expected value of Y, supports the claim that TIQ-learning and mean optimization are equivalent for this subset of the STAR*D data. The first step of Q-learning is to model the conditional expectation of Y given H2 and A2 which is the same as the first step of TIQ-learning. Thus, we use the same model and estimated decision rule at stage two given in Step 1 of the TIQ-learning algorithm. Next, we model the conditional expectation of , where Ỹ is the predicted future optimal outcome at stage one. We specify the working model , where and X1 = (qids0, slope0)T. We fit the model using least squares. Then, the Q-learning estimated optimal first-stage rule is . Q-learning recommends treatment differently at the first stage for only one of the 132 patients in the data. In addition, the estimated value of the TIQ- and Q-learning regimes are nearly the same and are displayed in Table 2. Binary Q-learning recommends treatment differently than TIQ-learning for 18 patients at the first stage, and the estimated value of the binary Q-learning regime is slightly lower than TIQ- and Q-learning. Also included in Table 2 are value estimates for four non-dynamic regimes that treat everyone according to the decision rules π1(h1) = a1 and π2(h2) = a2 for a1 ∈ {−1, 1} and a2 ∈ {−1, 1}. We estimate these values using the Augmented Inverse Probability Weighted Estimator given in Zhang et al. (2013).

Table 2.

Estimated value of dynamic and non-dynamic regimes using the Adaptive Inverse Probability Weighted Estimator.

| Estimated Value | |

|---|---|

| TIQ-learning | 0.24 |

| Q-learning | 0.23 |

| Binary Q-learning | 0.19 |

| (1, 1) | 0.13 |

| (-1, 1) | 0.24 |

| (1, -1) | 0.07 |

| (-1, -1) | 0.12 |

In summary, it appears that TIQ-learning and Q-learning perform similarly for this subset of the STAR*D data. This may be due to the lack of heteroskedasticity at the first stage. Thus, maximizing the end-of-stage-two QIDS using mean-optimal techniques seems appropriate and, in practice, equivalent to maximizing remission probabilities for each patient with TIQ-learning.

6. Discussion

We have proposed modeling frameworks for estimating optimal dynamic treatment regimes in settings where a non-mean distributional summary is the intended outcome to optimize. Threshold Interactive Q-learning (TIQ-learning) estimates a regime that maximizes the mass of the response distribution that exceeds a constant or patient-dependent threshold. Although TIQ-learning is just a special case of optimizing regimes based on binary responses, it is a helpful precursor for the development of Quantile Interactive Q-learning (QIQ-learning), which maximizes a prespecified quantile of the response distribution. If the focus is simply on optimizing a dynamic treatment regime for a binary threshold outcome, rather than quantile optimization, recent nonparametric techniques tailored to the binary outcome setting may be preferred to avoid problems due to model misspecification (Zhao et al., 2012, 2015). For example, it is possible to prespecify a class of regimes and directly optimize within that class by utilizing the value function,

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to estimate an optimal treatment regime that targets a quantile. Despite generalizations presented in the supplementary material, some researchers might be wary of the assumptions needed for consistency of the estimated optimal regime or the requisite modeling of the main effect function. An interesting future direction would be to develop a flexible framework for QIQ-learning that depends only on models for the treatment contrast function and not on the main effect term. In addition, it has been shown that Q-learning, A-learning, and g-estimation lead to identical estimators in certain cases but that Q-learning is less efficient (Chakraborty et al., 2010; Schulte et al., 2012). It is possible a g-estimation approach exists for maximizing quantiles based on structural nested distribution models (Robins, 2000; Vansteelandt et al., 2014).

Our proposed methods are designed for the two-stage setting, this is an important development given that many completed and ongoing SMART studies have this structure (Projects Using SMART, 2012; Laber, 2013). Here we considered binary treatments at both stages. In principle, the proposed methods can be extended to settings with more than two treatments at each stage by modeling additional treatment contrasts. Formalization of this idea merits further research.

7. Supplementary Materials

Online supplementary materials include discussions of modeling adjustments for heteroskedastic second-stage errors and patient-specific thresholds, a proof of Lemma 3.1 and toy example illustrating where this lemma does not apply, additional simulation results, and proofs of the theorems in Section 3.3.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Eric Laber acknowledges support from NIH grant P01 CA142538 and DNR grant PR-W-F14AF00171. Leonard Stefanski acknowledges support from NIH grants R01 CA085848 and P01 CA142538 and NSF grant DMS-0906421.

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials: Online supplementary materials include discussions of modeling adjustments for heteroskedastic second-stage errors and patient-specific thresholds, a proof of Lemma 3.1 and toy example illustrating where this lemma does not apply, additional simulation results, and proofs of the theorems in Section 3.3.

References

- Bembom O, van der Laan MJ. Analyzing sequentially randomized trials based on causal effect models for realistic individualized treatment rules. Statistics in medicine. 2008;27(19):3689–3716. doi: 10.1002/sim.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz RI, Wadden TA, Gehrman CA, Bishop-Gilyard CT, Moore RH, Womble LG, Cronquist JL, Trumpikas NL, Katz LEL, Xanthopoulos MS. Meal Replacements in the Treatment of Adolescent Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obesity. 2010;19(6):1193–1199. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RJ, Ruppert D. Transformation and Weighting in Regression. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty B, Moodie EE. Statistical Methods for Dynamic Treatment Regimes: Reinforcement Learning, Causal Inference, and Personalized Medicine. Vol. 76. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty B, Murphy SA, Strecher VJ. Inference for Non-Regular Parameters in Optimal Dynamic Treatment Regimes. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2010;19(3):317–343. doi: 10.1177/0962280209105013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Sackeim HA, Quitkin FM, Wisniewski SR, Lavori PW, Rosenbaum JF, Kupfer DJ STAR*D Investigators Group. Background and Rationale for the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) Study. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2003;26(2):457–94. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick N. Consistency Conditions for Probability Estimators and Integrals of Density Estimators. Utilitas Mathematica. 1974;6:61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg Y, Kosorok MR. Q-learning with Censored Data. Annals of statistics. 2012;40(1):529. doi: 10.1214/12-AOS968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg Y, Song R, Kosorok MR. Adaptive Q-learning. From Probability to Statistics and Back: High-Dimensional Models and Processes – A Festschrift in Honor of Jon A Wellner. 2013:150–62. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson R, Ansell P, Alshibani D. Regret-regression for Optimal Dynamic Treatment Regimes. Biometrics. 2010;66(4):1192–1201. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2009.01368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Ning J. Analysis of multi-stage treatments for recurrent diseases. Statistics in medicine. 2012;31(24):2805–2821. doi: 10.1002/sim.5456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Ning J, Wahed AS. Optimization of individualized dynamic treatment regimes for recurrent diseases. Statistics in medicine. 2014;33(14):2363–2378. doi: 10.1002/sim.6104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang C, Janes H, Huang Y. Combining biomarkers to optimize patient treatment recommendations. Biometrics. 2014;70(3):695–707. doi: 10.1111/biom.12191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laber EB. Example SMARTs. 2013 http://www4.stat.ncsu.edu/laber/smart.html.

- Laber EB, Linn KA, Stefanski LA. Interactive model building for q-learning. Biometrika. 2014a:asu043. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asu043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laber EB, Lizotte DJ, Ferguson B. Set-valued dynamic treatment regimes for competing outcomes. Biometrics. 2014b;70(1):53–61. doi: 10.1111/biom.12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laber EB, Lizotte DJ, Qian M, Pelham WE, Murphy SA. Dynamic treatment regimes: Technical challenges and applications. Electronic journal of statistics. 2014c;8(1):1225. doi: 10.1214/14-ejs920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavori PW, Dawson R. A Design for Testing Clinical Strategies: Biased Adaptive Within-Subject Randomization. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 2000;163(1):29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lavori PW, Dawson R. Dynamic Treatment Regimes: Practical Design Considerations. Clinical Trials. 2004;1(1):9–20. doi: 10.1191/1740774s04cn002oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn K, Laber E, Stefanski L. Adaptive Treatment Strategies in Practice: Planning Trials and Analyzing Data for Personalized Medicine. CRC Press; 2015. Constrained estimation for competing outcomes; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Luedtke AR, van der Laan MJ. Optimal dynamic treatments in resource-limited settings. 2015 doi: 10.1515/ijb-2015-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeague IW, Qian M. Evaluation of Treatment Policies Based on Functional Predictors. Statistica Sinica. 2013 doi: 10.5705/ss.2012.196. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moodie EE, Dean N, Sun YR. Q-learning: Flexible learning about useful utilities. Statistics in Biosciences. 2014;6(2):223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Moodie EEM, Richardson TS. Estimating Optimal Dynamic Regimes: Correcting Bias Under the Null. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 2010;37(1):126–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9469.2009.00661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA. Optimal Dynamic Treatment Regimes. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 2003;65(2):331–355. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA. A Generalization Error for Q-learning. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2005a;6(7):1073–1097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA. An Experimental Design for the Development of Adaptive Treatment Strategies. Statistics in Medicine. 2005b;24(10):1455–1481. doi: 10.1002/sim.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orellana L, Rotnitzky A, Robins JM. Dynamic Regime Marginal Structural Mean Models for Estimation of Optimal Dynamic Treatment Regimes, Part I: Main Content. The International Journal of Biostatistics. 2010;6(2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M, Schwab J, Gruber S, Blaser N, Schomaker M, van der Laan M. Targeted maximum likelihood estimation for dynamic and static longitudinal marginal structural working models. Journal of Causal Inference. 2014;2(2):147–185. doi: 10.1515/jci-2013-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Projects Using SMART. The Methodology Center at Pennsylvania State University. 2012 http://methodology.psu.edu/ra/adap-inter/projects.

- Robins J. A new approach to causal inference in mortality studies with a sustained exposure periodapplication to control of the healthy worker survivor effect. Mathematical Modelling. 1986;7(9):1393–1512. [Google Scholar]

- Robins J, Orellana L, Rotnitzky A. Estimation and extrapolation of optimal treatment and testing strategies. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27(23):4678–4721. doi: 10.1002/sim.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM. Statistical models in epidemiology, the environment, and clinical trials. Springer; 2000. Marginal structural models versus structural nested models as tools for causal inference; pp. 95–133. [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM. Proceedings of the Second Seattle Symposium in Biostatistics. Springer; New York: 2004. Optimal Structural Nested Models for Optimal Sequential Decisions; pp. 189–326. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Estimating Causal Effects of Treatments in Randomized and Nonrandomized Studies. Journal of educational Psychology. 1974;66(5):688. [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Lavori PW, Trivedi MH, Sackeim HA, Thase ME, Nierenberg AA, Quitkin FM, Kashner T, Kupfer DJ, Rosenbaum JF, Alpert J, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Lebowitz BD, Ritz L, Niederehe G STAR*D Investigators Group. Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D): Rationale and Design. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2004;25(1):119–142. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte PJ, Tsiatis AA, Laber EB, Davidian M. Q- and A-learning Methods for Estimating Optimal Dynamic Treatment Regimes. arXiv:1202.4177 [stat.ME] 2012 doi: 10.1214/13-STS450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortreed SM, Laber E, Stroup TS, Pineau J, Murphy SA. A Multiple Imputation Strategy for Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trials. Statistics in Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1002/sim.6223. to appear. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman B. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Song R, Wang W, Zeng D, Kosorok MR. Penalized Q-Learning for Dynamic Treatment Regimes. Statistica Sinica. 2015;25:901–920. doi: 10.5705/ss.2012.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan MJ. Causal effect models for intention to treat and realistic individualized treatment rules. 2006 doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan MJ, Petersen ML. Causal effect models for realistic individualized treatment and intention to treat rules. The International Journal of Biostatistics. 2007;3(1) doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan MJ, Petersen ML, Joffe MM. History-adjusted marginal structural models and statically-optimal dynamic treatment regimens. The International Journal of Biostatistics. 2005;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- Vansteelandt S, Joffe M, et al. Structural nested models and g-estimation: The partially realized promise. Statistical Science. 2014;29(4):707–731. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins CJCH. PhD Thesis. University of Cambridge; England: 1989. Learning from Delayed Rewards. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins CJCH, Dayan P. Q-Learning. Machine Learning. 1992;8:279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Tsiatis AA, Davidian M, Zhang M, Laber E. Estimating Optimal Treatment Regimes from a Classification Perspective. Stat. 2012a;1(1):103–114. doi: 10.1002/sta.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Tsiatis AA, Laber EB, Davidian M. A Robust Method for Estimating Optimal Treatment Regimes. Biometrics. 2012b;68(4):1010–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2012.01763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Tsiatis AA, Laber EB, Davidian M. Robust Estimation of Optimal Dynamic Treatment Regimes for Sequential Treatment Decisions. Biometrika. 2013 doi: 10.1093/biomet/ast014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Chen Z, Troendle JF, Zhang J. Causal Inference on Quantiles with an Obstetric Application. Biometrics. 2012c;68(3):697–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Zeng D, Rush AJ, Kosorok MR. Estimating Individualized Treatment Rules Using Outcome Weighted Learning. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2012;107(499):1106–1118. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2012.695674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YQ, Zeng D, Laber EB, Kosorok MR. New statistical learning methods for estimating optimal dynamic treatment regimes. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2015;0(0):00–00. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2014.937488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.