Abstract

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a major risk factor for the development of chronic kidney disease. Nuclear factor‐κB is a nuclear transcription factor activated post‐ischemia, responsible for the transcription of proinflammatory proteins. The role of nuclear factor‐κB in the renal fibrosis post‐AKI is unknown.

Methods and Results

We used a rat model of AKI caused by unilateral nephrectomy plus contralateral ischemia (30 minutes) and reperfusion injury (up to 28 days) to show impairment of renal function (peak: 24 hours), activation of nuclear factor‐κB (peak: 48 hours), and fibrosis (28 days). In humans, AKI is diagnosed by a rise in serum creatinine. We have discovered that the IκB kinase inhibitor IKK16 (even when given at peak serum creatinine) still improved functional and structural recovery and reduced myofibroblast formation, macrophage infiltration, transforming growth factor‐β expression, and Smad2/3 phosphorylation. AKI resulted in fibrosis within 28 days (Sirius red staining, expression of fibronectin), which was abolished by IKK16. To confirm the efficacy of IKK16 in a more severe model of fibrosis, animals were subject to 14 days of unilateral ureteral obstruction, resulting in tubulointerstitial fibrosis, myofibroblast formation, and macrophage infiltration, all of which were attenuated by IKK16.

Conclusions

Inhibition of IκB kinase at peak creatinine improves functional recovery, reduces further injury, and prevents fibrosis.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, fibrosis, ischemia, IκB kinase

Subject Categories: Nephrology and Kidney, Animal Models of Human Disease, Basic Science Research, Cell Signalling/Signal Transduction, Pathophysiology

Introduction

It is now widely recognized that acute kidney injury (AKI) is a major risk factor for chronic kidney disease (CKD), even in patients who regain full renal function post‐AKI.1 Patients with severe AKI (especially dialysis‐requiring AKI) have a higher probability of developing CKD than those with less severe AKI2 and an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality and proteinuria.3 Up to 8% of hospitalized patients present with AKI, of which 60% will never regain full renal function.4 Progression of AKI to CKD occurs in both patients1 and animal5, 6 models of AKI. After AKI, prolonged inflammation and maladaptive or incomplete regenerative processes encourage fibrosis and ultimately CKD.7 In patients, AKI is diagnosed by a rise in creatinine, which occurs 24 to 72 hours after AKI. In animals, interventions aimed at reducing AKI are frequently given either before or immediately after AKI, which limits the translation of these findings to cases of AKI associated with transplantation and coronary artery bypass graft surgery.8 This study was designed to develop an intervention that can be given after AKI at a time point when a significant rise in creatinine has occurred, which is able to improve recovery and prevent the development of fibrosis.

Nuclear factor‐κB (NF‐κB) is a nuclear transcription factor activated by cytokines and chemokines after AKI, resulting in the transcription of various inflammatory mediators.9, 10 Activation of NF‐κB is dependent on the activation of IκB kinase (IKK), a 3‐subunit protein (comprising α, β, and γ subunits). AKI causes activation of IKKβ,11 resulting in formation of an activated IKK complex with IKKα and IKKγ, causing IκBα phosphorylation (at Ser32/36) and consequently nuclear translocation of NF‐κB and gene transcription.12 Pretreatment of animals with small interfering RNA against IKKβ 48 hours prior to renal ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) has been shown to reduce renal dysfunction and injury.11 Mice expressing the human NF‐κB superrepressor IκBαΔN in renal proximal, distal, and collecting duct epithelial cells have shown improved renal function and attenuated inflammatory cells infiltration after renal IRI.13

Compound IKK16 [N‐(4‐Pyrrolidin‐1‐yl‐piperidin‐1‐yl‐)‐[4‐(4‐benzo [b]thiophen‐2‐yl‐pyrimidin‐2‐ylamino)‐phenyl] carboxamide hydrochloride] is a selective inhibitor of IKK. IKK16 targets the IKK inhibitor motifs (2‐anilino‐pyrimidines and 2,4‐disubstituted quinazolines). IKK16 is a potent IKK inhibitor in the low nanomolar range, with IC50 values of 40, 70, and 200 nmol/L for IKKβ, IKK complex, and IKKα inhibition, respectively.14

In this study, we report that administration of IKK16 at 24 hours after AKI (ie, when the peak in the rise in creatinine had already occurred) improves functional recovery (at 48 hours) and attenuates fibrosis at 28 days after AKI.

Methods

The animal protocols followed in this study were approved by the local Animal Use and Care Committee in accordance with the derivatives of both the Home Office Guidance on the Operation of Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 published by Her Majesty's Stationary Office and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Research Council.

Acute Kidney Injury

Surgical procedure and quantification of organ injury/dysfunction

This study was carried out on 74 male Wistar rats (Charles River Ltd, Margate, UK) weighing between 240 and 290 g and receiving a standard diet and water ad libitum. Animals were anesthetized using a ketamine (150 mg/kg) and xylazine (15 mg/kg) mixture IP (1.5 mL/kg). The hair was shaved and the skin cleaned with 70% alcohol (v/v). The animals were then placed on a homeothermic blanket set at 37°C. Animals received 0.1 mg/kg SC buprenorphine (0.1 mL/kg) prior to commencement of surgery. A midline laparotomy was then performed. The right renal pedicle (consisting of the renal artery, vein, and nerve) was isolated and tied off using a sterile 4‐0 silk‐braided suture (Pearsalls Ltd, Taunton, UK). The right kidney was then surgically removed. The left renal pedicle was isolated and clamped using a nontraumatic microvascular clamp at time 0. After 30 minutes of unilateral renal ischemia, the clamp was removed to allow reperfusion. For reperfusion, the kidneys were observed for a further 5 minutes to ensure reflow, following which 8 mL/kg saline at 37°C was injected into the abdomen and all incisions were sutured in 2 layers (Ethicon Prolene 4‐0). Animals were then allowed to recover on the homeothermic blanket and placed into cages upon recovery. Twenty‐four hours prior to the end of the experiment, the rats were placed in metabolic cages for the collection of urine and the subsequent determination of both estimated creatinine clearance and fractional excretion of sodium. At the end of the experiment, blood was taken by cardiac puncture into nonheparinized syringes and immediately decanted into 1.3‐mL serum gel tubes (Sarstedt, Germany). The blood was centrifuged at 9900g for 5 minutes to separate serum. All biochemical markers in serum and urine were measured in a blinded fashion by a commercial veterinary testing laboratory (IDEXX Ltd, West Sussex, UK). The left kidney was removed following removal of the heart. Half of the left kidney was snap‐frozen and stored at −80°C, and the other half was stored in 10% neutral buffered formalin.

Experimental design (acute time course)

Rats were randomly allocated into the following groups: (1) pre‐ischemia (n=4); (2) 24 hours reperfusion (n=4); (3) 48 hours reperfusion (n=8); and (4) 72 hours reperfusion (n=4).

Experimental design (late intervention)

Rats were randomly allocated into the following groups: (1) sham+vehicle (n=11); (2) IRI+vehicle (n=11); (3) IRI+IKK16 0.1 mg/kg (n=5); (4) IRI+IKK16 0.3 mg/kg (n=7); and (5) IRI+IKK16 1 mg/kg (n=9). Rats were administered vehicle (10% dimethyl sulfoxide) or N‐(4‐Pyrrolidin‐1‐yl‐piperidin‐1‐yl)‐[4‐(4‐benzo[b]thiophen‐2‐yl‐pyrimidin‐2‐ylamino)phenyl] carboxamide hydrochloride (IKK16) (a specific inhibitor of IKK) 24 hours after the onset of reperfusion via the tail vein at a volume of 1 mL/kg. IKK16 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (R&D systems Europe, Abingdon, UK), and the optimal dose obtained from previous IC50 values14 and a dose response (data not shown).

Experimental design (28 day time course and late intervention)

Rats were randomly allocated into the following groups: (1) sham+vehicle: n=8; (2) 1 day postreperfusion: n=4; (3) 2 days postreperfusion: n=4; (4) 7 days postreperfusion: n=4; (5) 14 days postreperfusion: n=4; (6) 28 days postreperfusion: n=7; (7) 1 mg/kg IKK16 24 hours postreperfusion+7 day reperfusion: n=7; and (8) 1 mg/kg IKK16 24 hours postreperfusion+28 day reperfusion: n=7. Rats were administered vehicle (10% dimethyl sulfoxide) or IKK16 24 hours after the onset of reperfusion via the tail vein at a volume of 1 mL/kg.

Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction

Surgical procedure and quantification of organ injury/dysfunction

This study was carried out on 25 male Wistar rats (Charles River Ltd, Margate, UK) weighing between 240 and 290 g and receiving a standard diet and water ad libitum. Animals were anesthetized using a ketamine (150 mg/kg) and xylazine (15 mg/kg) mixture intraperitoneally (1.5 mL/kg). The hair was shaved and the skin cleaned with 70% alcohol (v/v). The animals were then placed on a homoeothermic blanket set at 37°C. Animals received 0.1 mg/kg SC buprenorphine (0.1 mL/kg) prior to commencement of surgery. A midline laparotomy was then performed. The right renal ureter was isolated and tied off 0.5 cm from the renal pelvis using a sterile 5‐0 silk‐braided suture (Pearsalls Ltd, Taunton, UK) following which 8 mL/kg saline at 37°C was injected into the abdomen and all incisions were sutured in 2 layers (Ethicon Prolene 5‐0). Animals were then allowed to recover on the homeothermic blanket and placed into cages upon recovery. At the end of the experiment, both kidneys were removed following removal of the heart and was stored in 10% neutral buffered formalin. The nonligated ureteral kidney served as sham.

Experimental design (late intervention)

The rats were randomly allocated into the following groups: (1) contralateral sham (n=11) (contralateral kidneys belonging to groups 2 and 3); (2) unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO)+vehicle (n=9); and (3) UUO+IKK16 1 mg/kg (n=10). Rats were administered vehicle (10% dimethyl sulfoxide) or IKK16 through days 7 to 13 post‐ureteral obstruction subcutaneously at a volume of 1 mL/kg.

Histological Evaluation

The kidneys were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 hours before being dehydrated with 70% ethanol. Tissues were embedded in paraffin and sections were cut at 4 μm by a single technician in order to minimize variations in section thickness. The slides were deparaffinized with xylene, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and viewed with a NanoZoomer Digital Pathology Scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Japan). Ten random images were taken per slide and quantified for tubular dilatation by determining percentage background white space using ImageJ as a marker of renal injury.

Histochemical Sirius Red Staining

Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated through graded alcohols to distilled water. Sections were treated with phosphomolybdic acid (Polysciences, Warrington, PA), rinsed in distilled water, and stained with picrosirius red (Polysciences) for 60 minutes at room temperature. Sections were then immediately immersed in hydrochloride acid for 2 minutes before being dehydrated through graded alcohols and cleared. Ten images per section were taken with the NanoZoomer Digital Pathology Scanner, and quantification of Sirius red was performed using ImageJ analysis software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Immunohistochemistry

Sections cut at 4 μm were dewaxed and deparaffinized to PBS. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwaving (700 W) sections in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15 minutes. Once cooled, sections were incubated with 3% H2O2 for 20 minutes to inactivate endogenous peroxidises (Dako EnVision+ System‐HRP‐DAB, K4010) and subsequently treated with 10% normal goat serum (Dako, UK) to reduce nonspecific absorption. Sections were subsequently incubated at 37°C for 1 hour with the following primary antibodies: anti‐α‐smooth muscle actin antibody (1:400, cat#ab5694, Abcam, UK) or anti‐CD68 antibody ED1 (1:400; cat#MCA341R, AbD Serotec, UK), washed with PBS, and then incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes with labelled polymer‐HRP antibody (Dako EnVision+ System, HRP‐DAB). Sections were developed in DAB chromogen solution, and the reaction stopped by immersion of sections in water. Counterstaining was performed with Harris hematoxylin before sections were dehydrated and mounted in DPX mounting medium. Ten images per section were acquired with the NanoZoomer Digital Pathology Scanner in a double‐blinded manner. Quantification of staining was then performed using ImageJ analysis software.

Immunofluorescence

Sections cut at 4 μm were dewaxed and deparaffinized to PBS. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwaving (700 W) sections in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15 minutes. Once cooled, sections were incubated with 3% H2O2 for 20 minutes to inactivate endogenous peroxidises (Dako EnVision+ System, HRP‐DAB, K4010), and subsequently treated with 10% bovine serum albumin (Dako, UK). Sections were subsequently incubated at 4°C for 18 hours with the primary antibodies anti‐p65 (1:400, Cell Signaling, UK), washed with PBS, and then incubated at room temperature for 1 hour with a secondary antibody with preconjugated Alexa Fluor goat anti‐rabbit (Life Technologies, UK), washed with PBS, and mounted in DAPI containing mounting medium. Stained sections were visualized using Leica DM5500 B (Leica Microsystems, UK).

Western Blot Analysis

Western blots were carried out as previously described.15, 16 Three separate experiments of Western blot analysis were performed for each marker and tissues were done separately for each Western blot experiment. Briefly, previously snap‐frozen rat kidney samples were homogenized and centrifuged at 4000g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants were removed and centrifuged at 15 000g at 4°C for 40 minutes to obtain the cytosolic fraction. The pelleted nuclei were resuspended in extraction buffer. The suspensions were centrifuged at 15 000g for 20 minutes at 4°C. The resulting supernatants containing nuclear proteins were carefully removed, and protein content was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay following the manufacturer's directions. Proteins were separated by 8% SDS‐PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane, which was then incubated with a primary antibody mouse anti‐total IκBα (1:1000 cat#ab7217, Abcam, UK); mouse anti‐pIκBα Ser32/36 (1:1000 cat#ab12135, Abcam, UK); rabbit anti‐NF‐κB p65 (1:1000 cat#ab16502, Abcam, UK); rabbit anti–transforming growth factor‐β (TGF‐β) (1:1000, cat#ab66043); rabbit anti‐fibronectin (1:1000, cat#ab2413, Abcam, UK); rabbit anti‐pSmad2 Ser465/467/Smad3 Ser423/425 (1:1000, cat#D27F4, Cell Signaling Technologies, MA); and rabbit anti‐Smad2/3 (1:1000, cat#D7G7, Cell Signaling Technologies, MA). Blots were then incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (dilution 1:10 000) and developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system. The immunoreactive bands were visualized by autoradiography. The membranes were stripped and incubated with β‐actin monoclonal antibody (1:5000) or rabbit GAPDH antibody (1:1000, cat#D16H11, Cell Signaling Technologies, MA) and subsequently with an anti‐mouse antibody (1:10 000 cat#7076, Cell Signaling Technologies, MA) to assess gel‐loading homogeneity. Densitometric analysis of the bands was performed using Gel ProAnalyzer 4.5, 2000 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) and optical density analysis was expressed as a fold‐increase versus the sham group. In the sham group, the immunoreactive bands of the gel were respectively measured and normalized against the first immunoreactive band (standard sham sample) and the results of all the bands belonging to the same group were expressed as mean±SEM. This provides SEM for the sham group where a value of 1 is relative to the first immunoreactive band. Relative band intensity was assessed and normalized against parallel β‐actin expression.

Materials

Unless otherwise stated, all compounds used in this study were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich Company Ltd (Poole, Dorset, UK).

Statistical Analysis

All values described in the text and figures are expressed as mean±SEM for the number of observations. Each data point represents biochemical measurements obtained from up to 11 separate animals. Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism 6.0b (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data without repeated measurements were assessed by 1‐way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple‐comparison post‐hoc test. The area under the curve was calculated by plotting the values of serum creatinine at days 1, 2, 7, 14, 21, and 28 postreperfusion. Linear regressions were calculated by the least squares method and their significance were estimated by Fisher F test. A P value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Effect of Inhibition of IκB Kinase on Renal, Glomerular, and Tubular Function

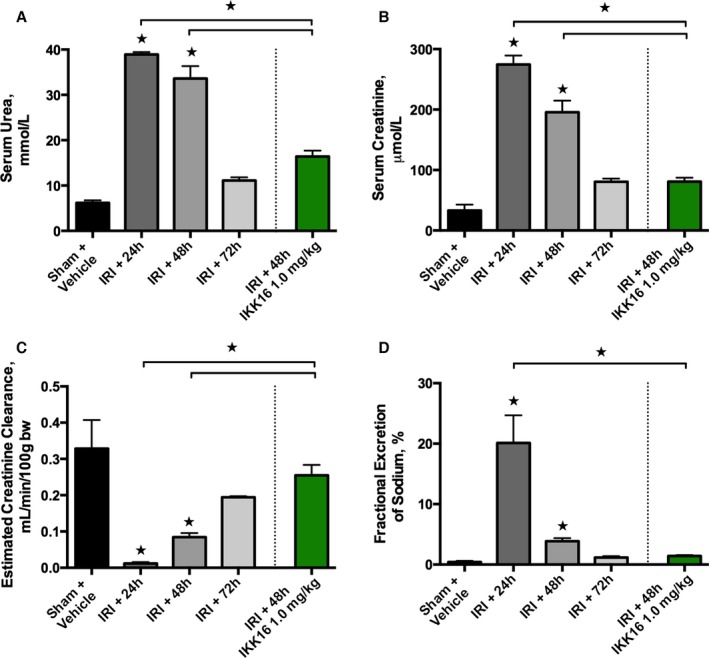

When compared with baseline (pre‐ischemia), rats with IRI/24 hours reperfusion developed significant renal (rises in serum urea and serum creatinine [SCr]) (both P<0.0001, Figure 1A and 1B), glomerular (fall in estimated creatinine clearance [eCCL]) (P<0.0001, Figure 1C), and tubular dysfunction (rise in fractional excretion of sodium) (P<0.0001, Figure 1D), along with increases in kidney injury molecule‐1 (P<0.05, Figure S1), followed by progressive recovery of renal, glomerular, and tubular function without intervention (Figure 1). When compared with sham‐operated rats, rats with IRI/48 hours reperfusion showed increases in serum urea (P<0.0001, Figure 1A), SCr (P<0.0001, Figure 1B), and kidney injury molecule‐1 (P<0.05, Figure S1), and a significant decrease in eCCL (P<0.001, Figure 1C), indicating the development of AKI. Having discovered that the peak renal dysfunction following 30 minutes of unilateral renal ischemia occurs at 24 hours of reperfusion and that maximal renal injury (Figure 2) and activation of IKK (Figure 3) occur between 24 and 48 hours of reperfusion, IKK16 was administered at 24 hours after the onset of reperfusion. Compared with rats subjected to IRI only, treatment of rats with IKK16 (1 mg/kg) at 24 hours into reperfusion resulted in a significant and substantial attenuation of serum urea (P<0.0001, Figure 1A), SCr (P<0.0001, Figure 1B), and eCCL (P<0.0001, Figure 1C) at 48 hours postreperfusion, while lower doses of IKK16 had no significant effect (Table S1).

Figure 1.

The effect of 30 minutes ischemia followed by different lengths of reperfusion (24, 48, or 72 hours) on glomerular and tubular function, and the effect of late administration of the IκB kinase inhibitor IKK16 (at 24 hours into reperfusion, followed by 48 hours of reperfusion). Serum urea (A), serum creatinine (B), and estimated creatinine clearance (C) were measured as indicators of glomerular function, and fractional excretion of sodium (D) as an indicator of tubular function (in different sets of animals for each time point). The peak of dysfunction occurs 24 hours after the onset of reperfusion. Sham+vehicle (10% dimethyl sulfoxide): n=4; ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI)+24 hours: n=4; IRI+48 hours (+vehicle): n=8; IRI+72 hours (+vehicle): n=4; and IRI+48 hours, IKK16 1 mg/kg (1 mL/kg IV) 24 hours into reperfusion (culled at 48 hours postreperfusion): n=9. Data are presented as mean±SEM for the number of observations. *P<0.05 vs sham+vehicle unless otherwise stated.

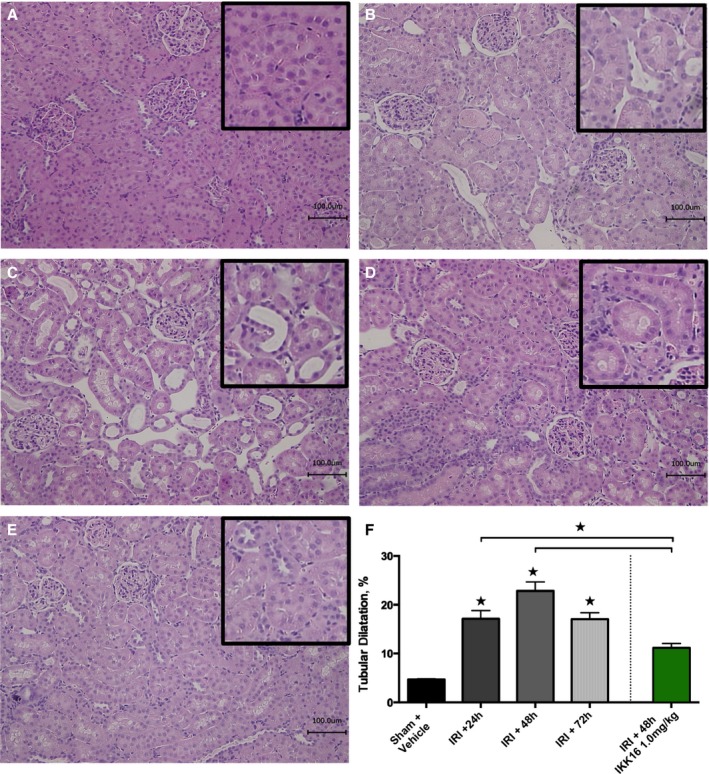

Figure 2.

The effect of 30 minutes ischemia followed by different lengths of reperfusion (24, 48, or 72 hours) on renal injury, and the effect of late administration of the IκB kinase inhibitor IKK16 24 hours into reperfusion. Representative histological hematoxylin‐eosin images (scale bar, 100 μm) of rat renal tissue were taken from groups without renal ischemia (sham+vehicle) (A) or from rats subjected to 30 minutes of renal ischemia followed by reperfusion for 24 hours (B), 48 hours (+vehicle) (C), and 72 hours (+vehicle) (D), and after 48 hours of reperfusion with treatment of IKK16 (1 mg/kg IV) 24 hours into reperfusion (E). Ten randomly selected fields from 3 individual kidneys (n=3) per group were selected and analyzed (total fields=30) for the determination of percentage background white space using ImageJ software, representing tubular dilatation (F). Data are presented as mean±SEM for the number of observations. *P<0.05 vs pre‐ischemia.

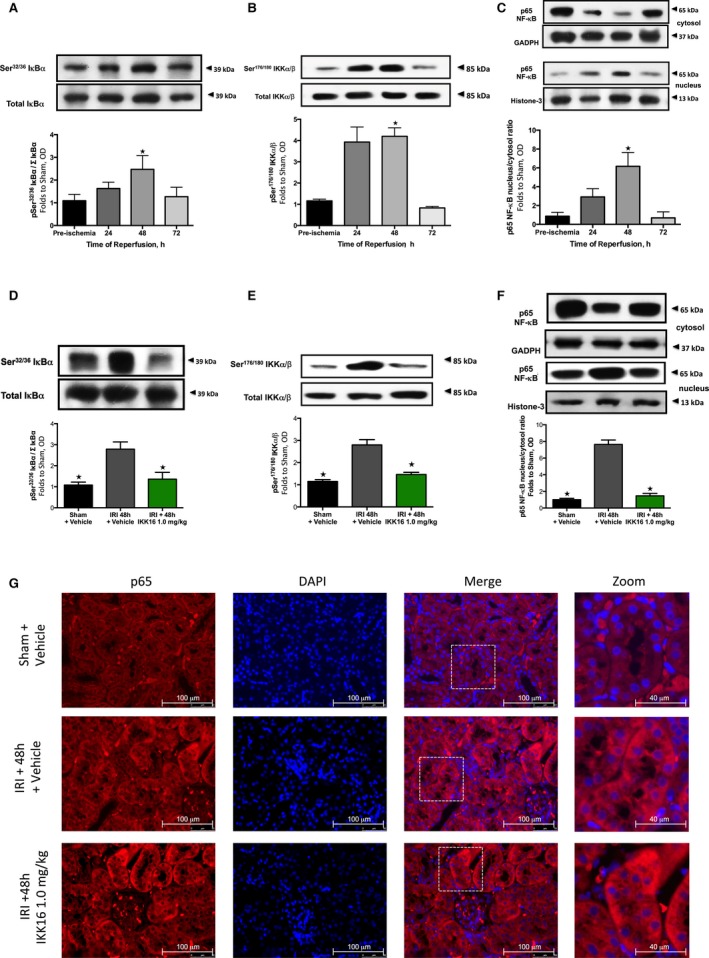

Figure 3.

The effect of 30 minutes ischemia followed by different lengths of reperfusion (24, 48, or 72 hours) and the effect of late administration on the nuclear factor κB (NF‐κB) pathway. Activation of IκBα was measured as phosphorylation of Ser32/36 on IκBα during the course of reperfusion (A) and with the administration of the IκB kinase inhibitor IKK16 at 24 hours postreperfusion (D). The activation of IκBα results in the activation of IKK, measured as the phosphorylation of IKKα/β at Ser176/180 during the course of reperfusion (B) and with the administration of IKK16 at 24 hours postreperfusion (E). Activation of IKK results in nuclear translocation of the p65 subunit of NF‐κB (shown in C and G) and the effect on the nuclear translocation of the p65 subunit of NF‐κB with the administration of IKK16 24 hours postreperfusion (F and G). (Representative images displayed in G), p65 images ×60 magnification (scale bar 100 μm) and zoom ×60 magnification plus ×2.5 digital zoom (scale bar 40 μm). (A, B, and C) Sham+vehicle: n=4; ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI)+24 hours: n=4; IRI+48 hours (+vehicle): n=4; and IRI+72 hours (+vehicle): n=4. (C, D, and E) Sham+vehicle: n=4; IRI+vehicle: n=5; and IRI+IKK16 1 mg/kg: n=5. Data are presented as mean±SEM for the number of observations. P<0.05 vs sham (A+B+C), *P<0.05 vs IRI+vehicle (D+E+F). OD indicates optical density.

When compared with sham‐vehicle, rats that underwent IRI/48 hours reperfusion developed tubular dilatation (P<0.0001, Figure 2C and 2F), a hallmark of AKI pathology,17, 18 as did rats subjected to IRI/72 hours reperfusion (P<0.0004, Figure 2D). The administration of IKK16 at peak creatinine (1 mg/kg; at 24 hours after the onset of reperfusion) significantly reduced signs of histological injury when compared with control‐vehicle rats subjected to IRI/48 hours (P<0.0007, Figure 2E and 2F).

Kidneys from rats with IRI/48 hours reperfusion exhibited significant phosphorylation of Ser32/36 on IκBα (P=0.0033, Figure 3A) and, hence, phosphorylation (Ser176/180 of IKKα/β) and activation of the IKK complex (P=0.0075, Figure 3B), as well as nuclear translocation of the NF‐κB subunit p65 (P<0.0001, Figure 3C). Interestingly, administration of IKK16 significantly attenuated the increase in the phosphorylation of IκBα on Ser32/36 (P=0.0154, Figure 3D), phosphorylation (Ser176/180 of IKKα/β) and activation of IKK (P=0.0006, Figure 3E), and the subsequent nuclear translocation of the p65 NF‐κB subunit (P<0.0001, Figure 3F and 3G) caused by unilateral IRI. Thus, IKK16 attenuated the activation of NF‐κB that occurred between 24 and 48 hours of reperfusion.

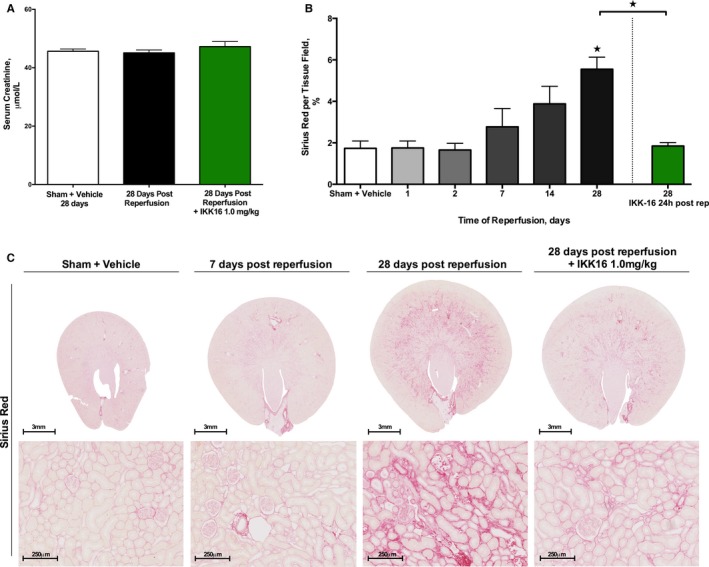

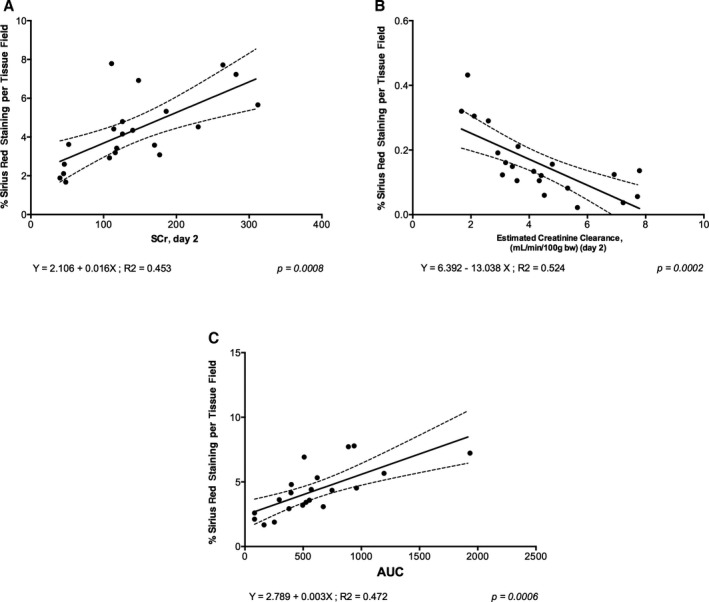

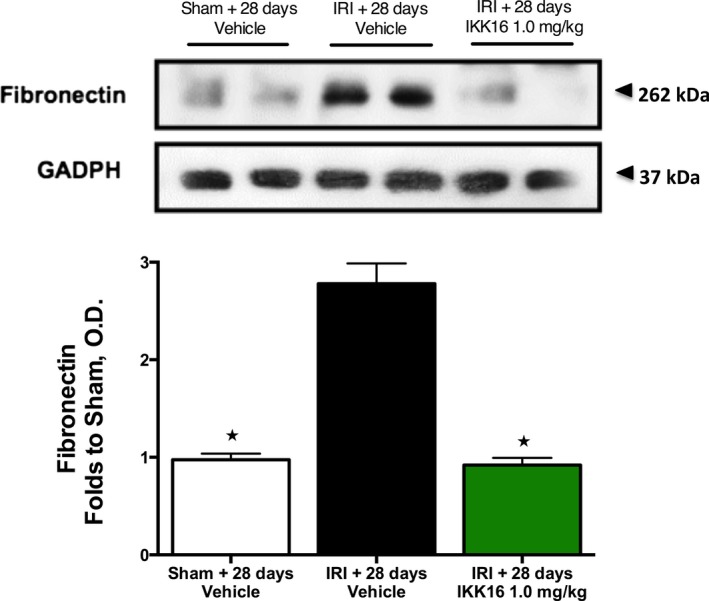

IκB Kinase Inhibition Inhibits Fibrosis (Day 28)

At 28 days postreperfusion, animals treated with either vehicle or IKK16 showed no renal dysfunction (rise in SCr, P=0.4520 [Figure 4A] or kidney injury molecule‐1, P=0.11 [Figure S1]) when compared with sham‐operated rats. Kidneys from rats with IRI/28 day reperfusion exhibited significant increases in Sirius red staining and, hence, fibrosis (P=0.0396, Figure 4B and 4C). IKK16 significantly attenuated the increase in Sirius red staining for collagen I and III and, therefore, fibrosis (P=0.0264, Figure 4B and 4C). Regression analysis revealed a significant linear relationship between renal dysfunction and fibrosis, Sirius red staining at day 28 versus SCr on day 2 (P=0.0008, Figure 5A), Sirius red staining at day 28 versus eCCL on day 2 (P=0.0002, Figure 5B), and Sirius red staining at 28 days versus area under the curve of SCr from days 1 to 28 (P=0.0006, Figure 5C), indicating that the degree of renal dysfunction on day 2 predicts the severity of fibrosis on day 28.

Figure 4.

The effect of late administration of the IκB kinase inhibitor IKK16 (24 hours postreperfusion) on the development of fibrosis (as measured by Sirius red for collagen I and III) after a 28‐day reperfusion period. A, Serum creatinine values in sham+vehicle (nephrectomy only, 28 days recovery): n=4; 28 days postreperfusion (control): n=9; and 1 mg/kg IKK16 24 hours postreperfusion+28 day reperfusion: n=8. B, The time course of development of fibrosis in rats after 30 minutes ischemia followed by different lengths of reperfusion (images for these data shown in C): top row shows cross section of representative groups (scale bar, 3 mm) and bottom row shows representative images at ×80 magnification (scale bar, 250 μm). Sham+vehicle: n=4; 1 day postreperfusion: n=4; 2 days postreperfusion: n=4; 7 days postreperfusion: n=4; 14 days postreperfusion: n=4; 28 days postreperfusion: n=8; and 1 mg/kg IKK16 24 hours postreperfusion+28 day reperfusion: n=7. Due to the concentration of the fibrosis in the corticomedullary junction, whole tissue cross sections (as seen in the top row of C) were analyzed and the percentage staining for Sirius red per tissue field calculated by ImageJ software. These values were then normalized to surface area percentage. Data are presented as mean±SEM for the number of observations. *P<0.05 vs sham+vehicle.

Figure 5.

Correlation data to show (A) serum creatinine (SCr) at day 2 vs Sirius red percentage per tissue field (indicative of fibrosis) at day 28, (B) the estimated creatinine clearance at day 2 vs Sirius red percentage per tissue field (indicative of fibrosis) at day 28, and (C) area under the curve (AUC) of SCr concentration (from day 1 to day 28) vs Sirius red percentage per tissue field (indicative of fibrosis) at day 28. All animal data (sham+vehicle, ischemia reperfusion injury [IRI]+vehicle, and IRI+IKK16 24 hours postreperfusion) are included in these graphs. AUC was calculated after plotting the values of SCr at day 1, 2, 7, 14, 21, and 28 postreperfusion. Linear regressions were calculated by the least squares method and their significance were estimated by Fisher F test. P<0.05 was considered to be significant.

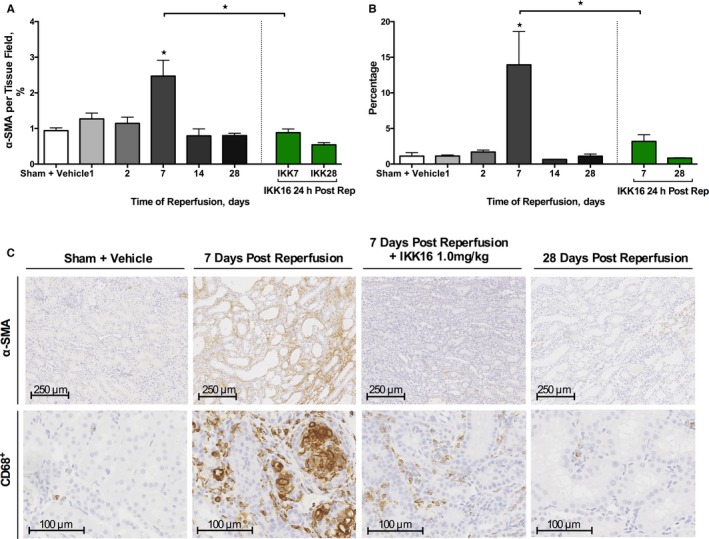

Effect of IKK16 on α‐Smooth Muscle Actin and CD68+ Staining, Transforming Growth Factor‐β, and Smad2/3 Phosphorylation (Ischemia Reperfusion Injury/7 Days)

Kidneys from rats with IRI/7 days reperfusion exhibited significant increases in α‐smooth muscle actin staining (myofibroblast formation, P<0.0001 [Figure 6A and 6C]) and CD68+ staining (macrophage infiltration, P=0.0001 [Figure 6B and 6C]), both of which were abolished by IKK16 (Figure 6A and 6C). Kidneys from rats with IRI/7 days reperfusion also exhibited significant increases in TGF‐β (P=0.0001, Figure 7A) and Smad2/3 phosphorylation (P<0.0001, Figure 7B), both of which were abolished by IKK16 (P<0.0001 and P=0.0014, respectively [Figure 7A and 7B]).

Figure 6.

The effect of the late administration of the IκB kinase inhibitor IKK16 (24 hours postreperfusion) on the expression of α‐smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA) for α‐SMA–positive myofibroblasts (A) and CD68+ for CD68+‐positive myofibroblasts (B) after a 28‐day reperfusion period. (Representative images displayed in C), α‐SMA images ×80 magnification (scale bar, 250 μm), CD68+ images ×200 magnification (scale bar, 100 μm). Ten randomly selected fields from each kidney were selected and analyzed for the determination of percentage stained rat kidney tissue using ImageJ software. Sham+vehicle: n=8 (80 total fields), 1 day postreperfusion: n=4 (40 total fields); 2 days postreperfusion: n=4 (40 total fields); 7 days postreperfusion: n=4 (40 total fields); 14 days postreperfusion: n=4 (40 total fields); 28 days postreperfusion: n=7 (70 total fields); 1 mg/kg IKK16 24 hours postreperfusion+7 day reperfusion: n=7 (70 total fields); and 1 mg/kg IKK16 24 hours postreperfusion+28 day reperfusion: n=7 (70 total fields). Data are presented as mean±SEM for the number of observations. *P<0.05 vs sham+vehicle, unless otherwise stated.

Figure 7.

The effect of late administration of the IκB kinase inhibitor IKK16 (24 hours postreperfusion) on the expression of transforming growth factor‐β (TGF‐β) (A), and the expression of both phosphorylated and total Smad2/3 (B) at 7 days postreperfusion. TGF‐β causes downstream Smad2/3 phosphorylation via binding to type I/II TGF‐β receptors. Sham 7 days+vehicle: n=4: ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI)+7 days vehicle: n=5: IRI+7 days and IKK16 1.0 mg/kg: n=5. Data are presented as mean±SEM for the number of observations. # P<0.05 vs sham, *P<0.05. OD indicates optical density.

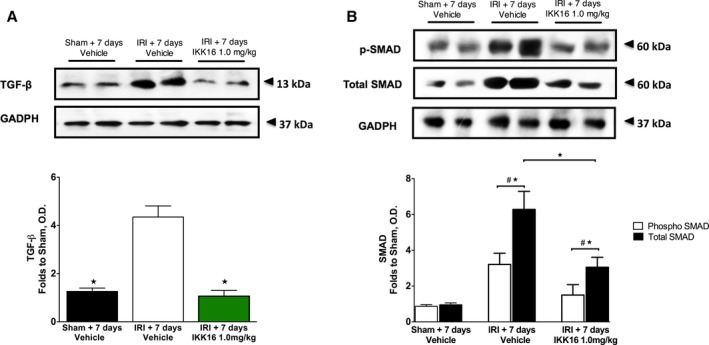

Effect of Late Inhibition of IκB Kinase on Fibronectin in the Rat Kidney at 28 Days Postreperfusion

We measured fibronectin (an extracellular matrix component) at 28 days post‐IRI in order to substantiate our histological finding that a significant degree of fibrosis had occurred at this time point. Using Western blot analysis, we confirm that 30 minutes of unilateral renal ischemia and 28 days of reperfusion resulted in a significant increase in the expression of fibronectin (P<0.0001, Figure 8). Administration of IKK16 prevented the expression of fibronectin (P<0.0001, Figure 8) caused by unilateral IRI and 28 days of reperfusion.

Figure 8.

The effect of late administration of the IκB kinase inhibitor IKK16 (24 hours postreperfusion) on the expression of fibronectin at 28 days postreperfusion. Fibronectin is a component of the extracellular matrix. Sham 28 days+vehicle: n=4: ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI)+28 days vehicle: n=5: IRI+28 days and IKK16 1.0 mg/kg: n=5. Data are presented as mean±SEM for the number of observations. *P<0.05. OD indicates optical density.

Effect of Inhibition of IκB Kinase in a Rat Model of Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction

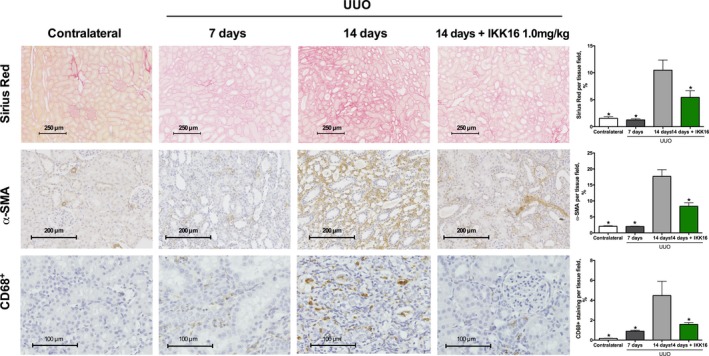

UUO resulted in tubulointerstitial fibrosis within 14 days as determined by increased staining for Sirius red (for collagen I and III) (P<0.0001, Figure 9) and α‐smooth muscle actin (for myofibroblast formation) (P<0.0001, Figure 9). When compared with rats treated with vehicle, rats treated with IKK16 (1 mg/kg SC) on days 7 to 13 following UUO resulted in a significant reduction in both Sirius red (P<0.0001, Figure 9) and α‐smooth muscle actin staining (P=0.0161, Figure 9) and, therefore, a reduction in tubulointerstitial fibrosis at day 14, indicating that activation of the IKK complex drives the development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Furthermore, compared with contralateral kidneys, kidneys of rats that had been subjected to UUO for 14 days demonstrated a significant increase in CD68+ staining, indicating macrophage accumulation (P=0.0007, Figure 9). The treatment of rats with IKK16 (1 mg/kg SC) on days 7 to 13 following UUO resulted in a significant reduction in CD68+ staining, and therefore a reduced macrophage accumulation in the renal tissue (P=0.0343, Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The effect of late administration of the IκB kinase inhibitor IKK16 (days 7–13 post‐unilateral ureteral obstruction [UUO]) on collagen deposition as stained by Sirius red (top row) (scale bar, 250 μm), myofibroblast formation as stained by α‐smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA) (middle row) (scale bar, 200 μm), and macrophage accumulation as measured for CD68+ (scale bar, 100 μm). Ten randomly selected fields from each kidney were selected and analyzed for the determination of percentage stained rat kidney tissue using ImageJ software. Contralateral kidneys (as control): n=11 (110 total fields); 7 days post‐UUO: n=6 (60 total fields); 14 days post‐UUO: n=9 (90 total fields); and 14 days post‐UUO+IKK16 1.0 mg/kg: n=10 (100 total fields). Data are presented as mean±SEM for the number of observations. *P<0.05 vs vehicle.

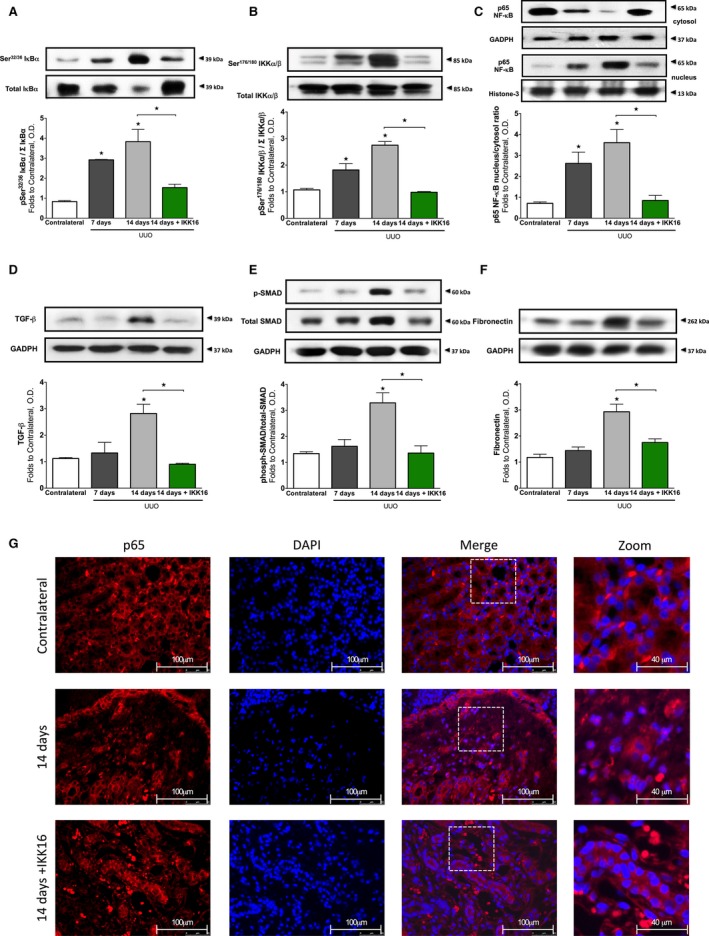

UUO (14 days) was associated with significant phosphorylation of Ser32/36 on IκBα (P<0.0001, Figure 10A) and, hence, phosphorylation (Ser176/180 of IKKα/β) and activation of the IKK complex (P<0.0001, Figure 10B), as well as nuclear translocation of the NF‐κB subunit p65 (P<0.0001, Figure 10C and 10G). Administration of IKK16 on days 7 to 13 of UUO significantly attenuated the increase in the phosphorylation of IκBα on Ser32/36 (P=0.0011, Figure 10A), phosphorylation (Ser176/180 of IKKα/β) and activation of IKK (P<0.0001, Figure 10B), and the subsequent nuclear translocation of the p65 NF‐κB subunit (P=0.0006, Figure 10C and 10G) caused by UUO. Moreover, rats subjected to 14 days of UUO (+vehicle) exhibited a significant increase in TGF‐β (P<0.0001, Figure 10D), phosphorylation of Smad2/3 (P<0.0001, Figure 10E), and fibronectin (P<0.0001, Figure 10F) in the renal tissue. The inhibition of IKK administered on days 7 to 13 after UUO attenuated increases in TGF‐β (P<0.0001, Figure 10D), phosphorylation of Smad2/3 (P=0.0001, Figure 10E), and fibronectin (P=0.0021, Figure 10F) in the renal tissue.

Figure 10.

The effect of unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) at 7 and 14 days, and the effect of late administration of the IκB kinase inhibitor IKK16 (1.0 mg/kg SC days 7 to 13 post‐UUO) on the nuclear factor‐κB (NF‐κB) pathway, fibrotic markers, and extracellular matrix components. Activation of IκBα was measured as phosphorylation of Ser32/36 on IκBα (A), the activation of IκBα results in the activation of IKK, measured as the phosphorylation of IKKα/β at Ser176/180 (B), which results in nuclear translocation of the p65 subunit of NF‐κB (shown in C and G). UUO causes a severe tubulointersitial fibrosis, driven by transforming growth factor‐β (TGF‐β) (D) and downstream Smad2/3 activation (E), resulting in the overproduction of extracellular matrix components such as fibronectin (F). (Representative images displayed in G), p65 images ×60 magnification (scale bar, 50 μm) and zoom ×60 magnification plus ×2.5 digital zoom (scale bar 40 μm). (A, B, and C) Contralateral: n=8; 7 days post‐UUO: n=3; 14 days post‐UUO+10% dimethyl sulfoxide vehicle days 7 to 13: n=6; and 14 days post‐UUO+1.0 mg/kg IKK16: n=5. (C, D, and E) Contralateral: n=8; 7 days post‐UUO: n=4; 14 days post‐UUO+10% dimethyl sulfoxide vehicle days 7 to 13: n=5; and 14 days post‐UUO+1.0 mg/kg IKK16: n=5. Data are presented as mean±SEM for the number of observations. *P<0.05 vs contralateral (unless otherwise stated). OD indicates optical density.

Discussion

There is now good evidence that the severity of AKI correlates with the progression of AKI to CKD: the more severe and prolonged the initial ischemic insult, the higher the probability of developing CKD later in life.2 Thus, the quick amelioration of the IRI‐dependent changes in biochemical markers following AKI by new therapies may reduce the probability of developing CKD. AKI is diagnosed by a rise in SCr, which occurs 24 to 72 hours after AKI. In severe cases of AKI, early renal replacement therapies are recommended to maintain fluid balance and solute clearance until recovery of renal function,19, 20 but there are no effective drugs that can be given at the diagnosis of AKI in order to improve recovery, limit injury, and prevent fibrosis.21

We report here on a model of AKI in rats (unilateral 30 minutes ischemia with contralateral nephrectomy), which results in a peak rise in SCr within 24 hours. Administration of IKK16, a specific inhibitor of IKK, at 24 hours inhibited the activation of NF‐κB (peak at 48 hours after AKI), aided the recovery of renal glomerular (SCr, urea, and eCCL) and tubular function (fractional excretion of sodium), prevented further injury (histology), and reduced renal fibrosis (Sirius red staining) at 28 days. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an intervention that can be given at peak creatinine to improve functional recovery and prevent the fibrosis associated with AKI.

What, then, is the mechanism(s) by which inhibition of IKK prevents fibrosis? We report here that inhibition of IKK (at 24 hours after AKI) prevents fibrosis, indicating that the transient activation of IKK early after AKI drives the fibrotic process in the kidney. We also report that the fibrosis at 28 days after AKI is preceded by a transient rise in tissue macrophages (CD68+ staining), which was maximal at day 7 after AKI. Similarly, Ysebaert et al (2000) reported a reversible increase in macrophages, which peaked at 5 days after AKI.18 Inhibition of IKK abolished the accumulation of macrophages at day 7 after AKI. In CKD patients, macrophage numbers closely correlate with glomerular scarring and interstitial fibrosis.17 AKI results in a shift of macrophage polarization in the kidney from M1 (F4/80+ and CD301−) to M2 (F4/80− and CD301+); the latter of which produce high levels of TGF‐β.22 We report here that AKI results in a rise in TGF‐β (at 7 days after AKI), which was abolished in rats treated with the IKK inhibitor. As TGF‐β drives fibrosis, we speculate that prevention by IKK16 of the formation of TGF‐β importantly contributes to the observed prevention of fibrosis by IKK inhibition.

How does prevention of TGF‐β formation by IKK16 reduce fibrosis? TGF‐β increases the activity of NADPH oxidase, which, in turn, drives the generation of myofibroblasts within the kidney.23 When activated with TGF‐β, the following cells can generate myofibroblasts: resident fibroblasts, pericytes,24 endothelial cells,25 epithelial cells26 and bone marrow–derived cells.27 We have confirmed with α‐smooth muscle actin staining that myofibroblasts are present 7 days after IRI in the kidney. We have discovered that inhibition of IKK at 24 hours after IRI abolishes the formation of myofibroblasts seen in vehicle‐treated animals at 7 days after IRI. The finding that inhibition of IKK attenuates myofibroblast formation and collagen I production caused by TGF‐β in dermal fibroblasts in vitro28 supports the view that activation of IKK is a key driver of the phenotypic change caused by TGF‐β in fibroblasts and potentially other cells.

The binding of TGF‐β to its receptor results in the phosphorylation and activation of the signaling molecules Smad2/3, which, in turn, results in the expression of target genes including the genes of fibronectin and collagen I and III. We report here that unilateral renal ischemia results in activation of Smad2/3 (measured as phospho‐Smad2/3 by Western blot analysis) at 7 days after the insult. Like the formation of TGF‐β, the activation of Smad2/3 was abolished in kidneys of rats treated with IKK16 at 24 hours after IRI. Interestingly, the formation of TGF‐β (which became significant at 7 days after the insult) was sustained for 28 days and associated with the expression of fibronectin and collagen I and III. Most notably, early inhibition of IKK (with a single injection of IKK16 at 24 hours after the insult) abolished the expression of TGF‐β, fibronectin, and collagen I and III caused by IRI within 28 days.

Taken together, these findings support the conclusions that the administration of IKK at 24 hours after renal ischemia abolishes both myofibroblast formation and TGF‐β formation. Prevention of the expression of TGF‐β by inhibition of IKK abolishes the TGF‐β–dependent activation of Smad2/3 as well as the expression of the Smad2/3‐dependet target genes fibronectin and collagen I and III. These data indicate that the activation of IKK is an early and pivotal step in the initiation of renal fibrosis following ischemia‐reperfusion. This raises the question of whether the activation of IKK also plays a pivotal role in models of renal fibrosis caused by other stimuli. UUO causes severe inflammation and subsequent fibrosis. In order to confirm that the activation of IKK is essential in the pathophysiology of the fibrosis development caused by UUO, we have treated rats from day 7 to day 13 after ureteral obstruction. We report that UUO resulted in the sustained activation of NF‐κB (measured as IκBα phosphorylation, IKK phosphorylation, and nuclear translocation of p65 at day 14 after UUO) as well as a significant renal fibrosis. Administration of IKK16 abolished the activation of NF‐κB and reduced the fibrosis caused by UUO. Development of fibrosis caused by UUO was also associated with the formation of TGF‐β, the TGF‐β–dependent activation of Smad2/3, and the formation of fibronectin. All of these events were abolished by IKK16, confirming in a second model of renal fibrosis that the formation of TGF‐β, the TGF‐β–dependent activation of Smad2/3, and the formation of fibronectin are IKK‐dependent phenomena.

There is evidence that activation of IKK/NF‐κB plays a key role in the development of fibrosis on other organs. Indeed, the formation of lung fibrosis caused by bleomycin in the mouse is associated with the activation of NF‐κB in fibroblasts,29 and inhibition of IKKβ significantly reduced the pulmonary fibrosis caused by bleomycin.30 In addition, inhibition of IKK has been shown to limit myofibroblast formation and fibrosis in a mouse model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.31 Activation of IKK (knock‐in model) also results in cardiac fibrosis and heart failure32 suggesting that activation of IKK may play a pivotal role as driver of the fibrotic process.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates, for the first time, that the administration of an IKK inhibitor at a time when peak creatinine levels had already occurred is still able to: (1) improve recovery of renal glomerular and tubular function, (2) prevent further injury, and (3) prevent fibrosis at 28 days after the AKI insult. This study also shows that the activation of IKK is an early and pivotal step in the development of renal fibrosis caused by either ischemia‐reperfusion (AKI) or ureteral obstruction.

Author Contributions

Thiemermann, Johnson, Patel, and Yaqoob designed research; Johnson, Purvis, Chiazza, Chen, Sordi, Merezhko, and Collino performed research; Johnson, Purvis, Patel, Chen, Hache, and Collino analyzed data; and Johnson, Purvis, Chen, and Thiemermann wrote the paper.

Sources of Funding

Johnson is funded by the British Pharmacological Society with the AJ Clarke Studentship. This work is funded by the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007‐2013) under REA grant agreement No. 608765, the William Harvey Research Foundation, and the University of Turin (Ricerca Locale ex‐60%). Purvis is funded by the British Heart Foundation (FS/13/58/30648). This work contributes to the Organ Protection research theme of the Barts Centre for Trauma Sciences, supported by the Barts and The London Charity (Award 753/1722).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. The Dose Response of IKK16 (at 24 Hours Into Reperfusion) in a Rat Model of 30 Minutes of Renal Ischaemia Followed by 48 Hours of Reperfusion (IRI) on Markers of Renal, Glomerular, and Tubular Function

Figure S1. The effect of late administration of the IκB kinase inhibitor IKK16 (24 hours postreperfusion) on serum kidney injury molecule‐1 (KIM‐1).

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005092 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005092.)28673900

References

- 1. Hsu CY. Yes, AKI truly leads to CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:967–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chawla LS, Amdur RL, Amodeo S, Kimmel PL, Palant CE. The severity of acute kidney injury predicts progression to chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1361–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ishani A, Nelson D, Clothier B, Schult T, Nugent S, Greer N, Slinin Y, Ensrud KE. The magnitude of acute serum creatinine increase after cardiac surgery and the risk of chronic kidney disease, progression of kidney disease, and death. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uchino S. The epidemiology of acute renal failure in the world. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006;12:538–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Basile DP, Donohoe D, Roethe K, Osborn JL. Renal ischemic injury results in permanent damage to peritubular capillaries and influences long‐term function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F887–F899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clements ME, Chaber CJ, Ledbetter SR, Zuk A. Increased cellular senescence and vascular rarefaction exacerbate the progression of kidney fibrosis in aged mice following transient ischemic injury. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee SB, Kalluri R. Mechanistic connection between inflammation and fibrosis. Kidney Int Suppl. 2010;(119):S22–S26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ryden L, Sartipy U, Evans M, Holzmann MJ. Acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting and long‐term risk of end‐stage renal disease. Circulation. 2014;130:2005–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Patel NS, Kerr‐Peterson HL, Brines M, Collino M, Rogazzo M, Fantozzi R, Wood EG, Johnson FL, Yaqoob MM, Cerami A, Thiemermann C. Delayed administration of pyroglutamate helix B surface peptide (pHBSP), a novel nonerythropoietic analog of erythropoietin, attenuates acute kidney injury. Mol Med. 2012;18:719–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sanz AB, Sanchez‐Nino MD, Ramos AM, Moreno JA, Santamaria B, Ruiz‐Ortega M, Egido J, Ortiz A. NF‐kappaB in renal inflammation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1254–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wan X, Fan L, Hu B, Yang J, Li X, Chen X, Cao C. Small interfering RNA targeting IKKbeta prevents renal ischemia‐reperfusion injury in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F857–F863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schmid JA, Birbach A. IkappaB kinase beta (IKKbeta/IKK2/IKBKB)—a key molecule in signaling to the transcription factor NF‐kappaB. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19:157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marko L, Vigolo E, Hinze C, Park JK, Roel G, Balogh A, Choi M, Wubken A, Cording J, Blasig IE, Luft FC, Scheidereit C, Schmidt‐Ott KM, Schmidt‐Ullrich R, Muller DN. Tubular epithelial NF‐kappaB activity regulates ischemic AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:2658–2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Waelchli R, Bollbuck B, Bruns C, Buhl T, Eder J, Feifel R, Hersperger R, Janser P, Revesz L, Zerwes HG, Schlapbach A. Design and preparation of 2‐benzamido‐pyrimidines as inhibitors of IKK. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen J, Kieswich JE, Chiazza F, Moyes AJ, Gobbetti T, Purvis GS, Salvatori DC, Patel NS, Perretti M, Hobbs AJ, Collino M, Yaqoob MM, Thiemermann C. IkappaB kinase inhibitor attenuates sepsis‐induced cardiac dysfunction in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:94–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Collino M, Aragno M, Mastrocola R, Gallicchio M, Rosa AC, Dianzani C, Danni O, Thiemermann C, Fantozzi R. Modulation of the oxidative stress and inflammatory response by PPAR‐gamma agonists in the hippocampus of rats exposed to cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;530:70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eardley KS, Zehnder D, Quinkler M, Lepenies J, Bates RL, Savage CO, Howie AJ, Adu D, Cockwell P. The relationship between albuminuria, MCP‐1/CCL2, and interstitial macrophages in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1189–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ysebaert DK, De Greef KE, Vercauteren SR, Ghielli M, Verpooten GA, Eyskens EJ, De Broe ME. Identification and kinetics of leukocytes after severe ischaemia/reperfusion renal injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:1562–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Macedo E, Mehta RL. Early vs late start of dialysis: it's all about timing. Crit Care. 2010;14:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shiao CC, Wu VC, Li WY, Lin YF, Hu FC, Young GH, Kuo CC, Kao TW, Huang DM, Chen YM, Tsai PR, Lin SL, Chou NK, Lin TH, Yeh YC, Wang CH, Chou A, Ko WJ, Wu KD; National Taiwan University Surgical Intensive Care Unit‐Associated Renal Failure Study Group . Late initiation of renal replacement therapy is associated with worse outcomes in acute kidney injury after major abdominal surgery. Crit Care. 2009;13:R171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heung M, Chawla LS. Predicting progression to chronic kidney disease after recovery from acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21:628–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shen B, Liu X, Fan Y, Qiu J. Macrophages regulate renal fibrosis through modulating TGFbeta superfamily signaling. Inflammation. 2014;37:2076–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bondi CD, Manickam N, Lee DY, Block K, Gorin Y, Abboud HE, Barnes JL. NAD(P)H oxidase mediates TGF‐beta1‐induced activation of kidney myofibroblasts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:93–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu CF, Chiang WC, Lai CF, Chang FC, Chen YT, Chou YH, Wu TH, Linn GR, Ling H, Wu KD, Tsai TJ, Chen YM, Duffield JS, Lin SL. Transforming growth factor beta‐1 stimulates profibrotic epithelial signaling to activate pericyte‐myofibroblast transition in obstructive kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:118–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Piera‐Velazquez S, Li Z, Jimenez SA. Role of endothelial‐mesenchymal transition (EndoMT) in the pathogenesis of fibrotic disorders. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:1074–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lan HY. Tubular epithelial‐myofibroblast transdifferentiation mechanisms in proximal tubule cells. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2003;12:25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. LeBleu VS, Taduri G, O'Connell J, Teng Y, Cooke VG, Woda C, Sugimoto H, Kalluri R. Origin and function of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1047–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mia MM, Bank RA. The IkappaB kinase inhibitor ACHP strongly attenuates TGFbeta1‐induced myofibroblast formation and collagen synthesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2015;19:2780–2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sun X, Chen E, Dong R, Chen W, Hu Y. Nuclear factor (NF)‐kappaB p65 regulates differentiation of human and mouse lung fibroblasts mediated by TGF‐beta. Life Sci. 2015;122:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Inayama M, Nishioka Y, Azuma M, Muto S, Aono Y, Makino H, Tani K, Uehara H, Izumi K, Itai A, Sone S. A novel IkappaB kinase‐beta inhibitor ameliorates bleomycin‐induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1016–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wei J, Shi M, Wu WQ, Xu H, Wang T, Wang N, Ma JL, Wang YG. IkappaB kinase‐beta inhibitor attenuates hepatic fibrosis in mice. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:5203–5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maier HJ, Schips TG, Wietelmann A, Kruger M, Brunner C, Sauter M, Klingel K, Bottger T, Braun T, Wirth T. Cardiomyocyte‐specific IkappaB kinase (IKK)/NF‐kappaB activation induces reversible inflammatory cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11794–11799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. The Dose Response of IKK16 (at 24 Hours Into Reperfusion) in a Rat Model of 30 Minutes of Renal Ischaemia Followed by 48 Hours of Reperfusion (IRI) on Markers of Renal, Glomerular, and Tubular Function

Figure S1. The effect of late administration of the IκB kinase inhibitor IKK16 (24 hours postreperfusion) on serum kidney injury molecule‐1 (KIM‐1).