Abstract

Background

There are well‐documented geographical differences in cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality for non‐Hispanic whites. However, it remains unknown whether similar geographical variation in CVD mortality exists for Asian American subgroups. This study aims to examine geographical differences in CVD mortality among Asian American subgroups living in the United States and whether they are consistent with geographical differences observed among non‐Hispanic whites.

Methods and Results

Using US death records from 2003 to 2011 (n=3 897 040 CVD deaths), age‐adjusted CVD mortality rates per 100 000 population and age‐adjusted mortality rate ratios were calculated for the 6 largest Asian American subgroups (Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese) and compared with non‐Hispanic whites. There were consistently lower mortality rates for all Asian American subgroups compared with non‐Hispanic whites across divisions for CVD mortality and ischemic heart disease mortality. However, cerebrovascular disease mortality demonstrated substantial geographical differences by Asian American subgroup. There were a number of regional divisions where certain Asian American subgroups (Filipino and Japanese men, Korean and Vietnamese men and women) possessed no mortality advantage compared with non‐Hispanic whites. The most striking geographical variation was with Filipino men (age‐adjusted mortality rate ratio=1.18; 95% CI, 1.14–1.24) and Japanese men (age‐adjusted mortality rate ratio=1.05; 95% CI: 1.00–1.11) in the Pacific division who had significantly higher cerebrovascular mortality than non‐Hispanic whites.

Conclusions

There was substantial geographical variation in Asian American subgroup mortality for cerebrovascular disease when compared with non‐Hispanic whites. It deserves increased attention to prioritize prevention and treatment in the Pacific division where approximately 80% of Filipinos CVD deaths and 90% of Japanese CVD deaths occur in the United States.

Keywords: epidemiology, geographical disparities, mortality rate, race and ethnicity

Subject Categories: Epidemiology, Cardiovascular Disease, Race and Ethnicity

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Whereas lower mortality rates were observed among Asian American subgroups compared with non‐Hispanic whites across divisions for cardiovascular disease mortality and ischemic heart disease mortality, there were a number of regional divisions where certain Asian American possessed no mortality advantage in cerebrovascular disease mortality.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Etiological research to better understand geographically related causes of cardiovascular disease and how these contributing factors may differentially impact cerebrovascular disease across Asian American subgroups may help clinicians incorporate culturally competent approaches and provide better care to Asian American patients.

Introduction

Although mortality rates from cardiovascular disease (CVD) have decreased over the past decade in the United States, it continues to contribute to one fourth of all deaths.1 Recent literature has shown that the burden of CVD in the United States differs geographically, with the southeast having particularly high mortality rates.2 This pattern is consistent across sex and age strata and has been observed in both non‐Hispanic white (NHW) and non‐Hispanic black populations.2 However, little is known about the US geographical disparities of CVD among Asian American subgroups. Asian Americans are one of the fastest growing racial/ethnic groups in the United States, increasing from a population of 11.9 to 18.2 million in the past decade.3, 4 Asian Americans have been traditionally known as the “model minority” and have been thought to have better health outcomes than other racial/ethnic minority groups and non‐Hispanic whites.5 However, recent studies have suggested that certain Asian American subgroups, such as Japanese, Filipinos, and Asian Indians, have elevated risks for CVD‐specific mortality and morbidity.6, 7 It remains unclear whether the geographical patterns identified in non‐Hispanic whites and blacks exist among Asian Americans.

In addition, further study is needed to better understand geographical variations within Asian American subgroups. Asian Americans are a diverse population with different immigration histories, lifestyle and dietary patterns, and cultures—all of which could contribute to regional differences in CVD mortality for Asian American subgroups because of differential migration patterns to parts of the United States, and also potentially because of the effects of those areas on CVD mortality. In terms of the first group of processes that pertain to selection, migration to different parts of the United States may have happened at different times for different Asian American subgroups, and these population differences may be associated with better or worse health. In addition, individuals from a particular country may also have differentially located themselves in the United States by attributes that may be intricately linked to health, such as socioeconomic position. Other factors associated with differential migration may also play a role in observed geographical differences in health. Examples include differences in migration associated with different levels of ties with the country of origin, different types of economic activity in the new environment, or different infrastructure of the place of settlement that was differentially beneficial for migrating individuals.8 Alternatively, the second broad explanation is that the impact of the physical and social environment by region may have differential effects on Asian American subgroups as compared with non‐Hispanic whites. This may be true, for example, because ethnic enclaves may insulate individuals of Asian American subgroups from deleterious or beneficial social environments.

Our goal with this study is to better understand geographical variation of CVD mortality among the 6 largest Asian American subgroups by the 9 US Census divisions. Our results will provide a basis for developing testable hypotheses for understanding the impacts of regional US environments and migration patterns on CVD mortality among Asian American subgroups. Our findings also may have important clinical implications for identifying Asian American subgroups in different regions of the country that may be at a relatively increased risk of CVD.

Methods

The institutional review board of Stanford University (Stanford, CA) approved this study and provided a waiver for use of these publicly available mortality and US Census data. CVD mortality among the 6 largest Asian American subgroups and non‐Hispanic whites were examined using the Multiple Cause of Death mortality database from the National Center for Health Statistics, 2003–2011. It contains underlying cause of death (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes), race/ethnicity, sex, age of death, and places of birth, death, and residence as well as other decedent characteristics. Race and ethnicity are reported by the funeral director who collected the information from an informant or on the basis of observation. Before 2003, the US Standard Certificate of Death listed only 3 specific Asian American subgroups (Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese), but the 2003 revision added Asian Indian, Korean, and Vietnamese. Adoption of the 2003 standard has varied by states; our study includes only states and years that reported on all 6 groups. Given that state‐specific mortality rates can be unstable because of small numbers within Asian American subgroups, Census division (9 groups of states: New England, Middle Atlantic, East North Central, West North Central, South Atlantic, East South Central, West South Central, Mountain, and Pacific)9 was used as the geographical unit for analysis in order to reach reliable estimates of mortality rates in each Asian American subgroup.10 Reported state of residence of the decedent was used to assign the death to a Census division.9

Ascertainment of CVD Mortality

CVD mortality was captured using the underlying cause listed on the death certificate. Deaths were attributed to CVD if the following International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes were listed as the primary cause of death: (I00–I09, I10, I11, I12, I13, I15, I20–I51.9, I60–I69, I70, and I71–I78). Ischemic heart disease (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, I20–I25) and cerebrovascular disease (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, I60–I69) were also examined to test variation in mortality patterns by CVD cause subtype. The East South Central division was excluded from primary analyses because of unstable estimation in Asian American subgroups. Sparse data in this division are primarily because of the lack of adoption of the 2003 standard by the states in this division as well as small Asian American populations.

Mortality Measures

For the 6 Asian American subgroups and non‐Hispanic whites, sex‐specific age‐adjusted mortality rates (AMRs) of CVD and CVD subtypes per 100 000 population were calculated in each Census division. Denominator data for Asian American subgroup as well as sex‐ and age‐specific population counts by Census division were extracted from the 2000 and 2010 US Census. All statistical and graphical analyses were performed in R software (version 3.1.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).11 Age‐adjusted mortality rates were estimated using the epitools package for R12 and reported through direct standardization to the US standard population in year 2000 using the following age categories: 25 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 59, 60 to 74, and 75+.

In addition to age‐adjusted mortality rates, sex‐specific age‐adjusted CVD mortality rate ratios (AMRRs) were calculated to compare the adjusted rates in each Asian American subgroup with non‐Hispanic whites in the same Census division. An AMRR larger than 1 indicates that the specific race/ethnic‐sex group has higher CVD or CVD subtype mortality rates than non‐Hispanic whites in that division.

Maps

CVD age‐adjusted mortality rate ratio was mapped using the maps package for R13 to visualize quantitative differences among the 6 Asian American subgroups compared with non‐Hispanic whites and across the 9 Census divisions. Eight‐level color ramps were used to divide the division‐specific AMRR based on the mortality rate ratio distribution.

Results

A total of 3 897 040 death records with CVD as the primary cause of death were included in this study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cardiovascular Deaths by Census Division, 2003–2011

| Non‐Hispanic White | Asian Indian | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New.England | 136 815 | 114 | 130 | 79 | 30 | 43 | 46 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 597 825 | 4143 | 6999 | 1780 | 306 | 1648 | 221 |

| E.N.Central | 807 585 | 1655 | 1046 | 1151 | 521 | 640 | 249 |

| W.N.Central | 359 311 | 212 | 198 | 197 | 133 | 102 | 251 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 581 031 | 1127 | 806 | 1205 | 296 | 316 | 383 |

| E.S.Central | 23 329 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| W.S.Central | 445 711 | 1184 | 812 | 653 | 291 | 402 | 1243 |

| Mountain | 130 347 | 104 | 259 | 556 | 440 | 105 | 105 |

| Pacific | 711 360 | 3514 | 18 328 | 21 737 | 17 792 | 5432 | 4710 |

| Total | 3 793 314 | 12 060 | 28 581 | 27 365 | 19 814 | 8693 | 7213 |

This only includes deaths for states and years reporting deaths in all 6 primary Asian American groups. For the analysis in the East South Central Division that includes all years but only non‐Hispanic white, Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese, the total numbers of cardiovascular deaths are: 428 829 for non‐Hispanic white, 133 for Chinese, 126 for Filipino, and 66 for Japanese.

Age‐Adjusted CVD Mortality Rate

Age‐adjusted CVD mortality rates and 95% CIs, by sex and racial/ethnic group, are presented in Table 2 and by CVD subtype (ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease) in Tables 3 and 4. For Asian Indians, Japanese, Koreans, and Vietnamese, there were nearly 2‐fold higher total CVD mortality rates when comparing the highest versus lowest divisions. For Asian American subgroups, age‐adjusted CVD mortality rates by sex were highest in Filipino men in the Pacific division (382; 95% CI, 375–390 per 100 000) and Indian women in the West South Central division (238; 95% CI, 216–262 per 100 000 population), and lowest in Korean men (79; 95% CI, 66–95 per 100 000 population) and women (73; 95% CI, 62–86 per 100 000 population) in the South Atlantic division.

Table 2.

CVD AMR Per 100 000 Population by Sex and Race/Ethnicity, 2003–2011

| NHW | Asian Indian | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | |

| Male | ||||||||||||||

| New.England | 403 | 400 to 406 | 146 | 108 to 195 | 154 | 117 to 199 | 208 | 146 to 289 | 99 | 34 to 229 | 141 | 74 to 246 | 165 | 98 to 263 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 487 | 485 to 489 | 301 | 287 to 315 | 244 | 236 to 252 | 268 | 248 to 289 | 152 | 121 to 189 | 235 | 217 to 255 | 184 | 149 to 225 |

| E.N.Central | 463 | 462 to 465 | 240 | 222 to 259 | 172 | 157 to 188 | 227 | 207 to 249 | 244 | 213 to 280 | 190 | 166 to 218 | 185 | 150 to 227 |

| W.N.Central | 428 | 426 to 430 | 179 | 143 to 222 | 129 | 102 to 161 | 271 | 215 to 337 | 188 | 131 to 261 | 164 | 105 to 246 | 167 | 136 to 203 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 421 | 419 to 422 | 214 | 196 to 233 | 182 | 164 to 201 | 258 | 236 to 281 | 146 | 109 to 194 | 79 | 66 to 95 | 102 | 87 to 119 |

| W.S.Central | 488 | 486 to 491 | 257 | 235 to 282 | 179 | 162 to 197 | 264 | 233 to 298 | 265 | 201 to 344 | 199 | 161 to 242 | 203 | 186 to 221 |

| Mountain | 390 | 387 to 393 | 222 | 165 to 293 | 210 | 176 to 249 | 277 | 243 to 314 | 335 | 290 to 386 | 264 | 189 to 360 | 188 | 136 to 254 |

| Pacific | 459 | 457 to 460 | 276 | 263 to 289 | 243 | 238 to 248 | 382 | 375 to 390 | 350 | 343 to 358 | 230 | 220 to 240 | 206 | 197 to 214 |

| Female | ||||||||||||||

| New.England | 314 | 312 to 316 | 109 | 77 to 150 | 150 | 116 to 193 | 130 | 88 to 186 | 107 | 69 to 163 | 205 | 132 to 306 | 132 | 77 to 214 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 386 | 385 to 388 | 234 | 222 to 246 | 203 | 196 to 210 | 182 | 170 to 195 | 149 | 129 to 170 | 225 | 210 to 240 | 133 | 105 to 167 |

| E.N.Central | 358 | 357 to 359 | 221 | 204 to 239 | 169 | 154 to 184 | 160 | 146 to 174 | 151 | 134 to 169 | 211 | 190 to 234 | 170 | 138 to 208 |

| W.N.Central | 334 | 333 to 336 | 197 | 157 to 244 | 150 | 122 to 182 | 166 | 133 to 206 | 144 | 117 to 178 | 170 | 128 to 221 | 151 | 122 to 184 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 312 | 310 to 313 | 157 | 142 to 174 | 148 | 133 to 164 | 173 | 159 to 188 | 127 | 112 to 145 | 73 | 62 to 86 | 92 | 77 to 108 |

| W.S.Central | 385 | 383 to 386 | 238 | 216 to 262 | 143 | 129 to 159 | 161 | 143 to 181 | 169 | 147 to 194 | 222 | 194 to 254 | 188 | 172 to 205 |

| Mountain | 305 | 301 to 307 | 180 | 125 to 252 | 158 | 129 to 191 | 165 | 144 to 189 | 183 | 159 to 210 | 155 | 114 to 207 | 156 | 111 to 214 |

| Pacific | 359 | 358 to 360 | 214 | 202 to 226 | 196 | 192 to 200 | 233 | 228 to 237 | 208 | 203 to 212 | 213 | 205 to 221 | 182 | 175 to 190 |

AMR indicates age‐adjusted mortality rates; CVD, cardiovascular disease; NHW, non‐Hispanic white.

Table 3.

Ischemic Heart Disease AMR Per 100 000 Population by Sex and Race/Ethnicity, 2003–2011

| Ischemic Heart Disease | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHW | Asian Indian | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese | ||||||||

| AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | |

| Male | ||||||||||||||

| New.England | 221 | 219 to 224 | 95 | 65 to 137 | 72 | 48 to 106 | 123 | 77 to 190 | 44 | 8 to 148 | 63 | 21 to 146 | 70 | 30 to 142 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 317 | 315 to 318 | 215 | 204 to 227 | 164 | 158 to 171 | 167 | 151 to 184 | 88 | 64 to 117 | 155 | 140 to 171 | 97 | 72 to 129 |

| E.N.Central | 262 | 261 to 263 | 139 | 126 to 154 | 81 | 70 to 92 | 114 | 100 to 130 | 138 | 114 to 165 | 96 | 79 to 117 | 75 | 54 to 103 |

| W.N.Central | 232 | 230 to 233 | 96 | 71 to 129 | 56 | 39 to 78 | 141 | 103 to 191 | 110 | 68 to 169 | 93 | 51 to 159 | 62 | 44 to 85 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 235 | 234 to 236 | 112 | 100 to 126 | 78 | 67 to 91 | 137 | 121 to 154 | 78 | 52 to 114 | 36 | 27 to 47 | 45 | 35 to 57 |

| W.S.Central | 278 | 277 to 280 | 151 | 134 to 170 | 74 | 63 to 86 | 130 | 109 to 154 | 143 | 98 to 203 | 89 | 66 to 118 | 85 | 75 to 97 |

| Mountain | 206 | 204 to 208 | 131 | 90 to 188 | 96 | 73 to 123 | 113 | 92 to 138 | 161 | 131 to 197 | 110 | 65 to 178 | 60 | 33 to 102 |

| Pacific | 264 | 263 to 265 | 180 | 170 to 191 | 123 | 120 to 127 | 201 | 196 to 206 | 178 | 173 to 183 | 122 | 115 to 129 | 104 | 98 to 110 |

| Female | ||||||||||||||

| New.England | 141 | 139 to 142 | 54 | 32 to 84 | 52 | 33 to 80 | 51 | 26 to 92 | 35 | 15 to 73 | 73 | 32 to 144 | 60 | 25 to 122 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 228 | 227 to 230 | 150 | 140 to 160 | 126 | 121 to 132 | 101 | 92 to 111 | 79 | 65 to 95 | 138 | 126 to 150 | 69 | 49 to 95 |

| E.N.Central | 161 | 160 to 162 | 99 | 88 to 112 | 69 | 60 to 79 | 68 | 60 to 78 | 65 | 54 to 78 | 99 | 85 to 116 | 87 | 64 to 116 |

| W.N.Central | 138 | 137 to 139 | 77 | 53 to 109 | 29 | 18 to 45 | 38 | 23 to 60 | 61 | 43 to 85 | 64 | 39 to 98 | 37 | 24 to 56 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 140 | 139 to 141 | 70 | 60 to 82 | 60 | 51 to 71 | 69 | 60 to 79 | 57 | 46 to 70 | 25 | 18 to 33 | 31 | 23 to 42 |

| W.S.Central | 174 | 173 to 175 | 114 | 99 to 131 | 47 | 39 to 56 | 60 | 49 to 73 | 72 | 58 to 89 | 108 | 88 to 131 | 63 | 53 to 73 |

| Mountain | 115 | 114 to 117 | 105 | 63 to 164 | 41 | 27 to 59 | 55 | 43 to 70 | 57 | 44 to 74 | 36 | 19 to 64 | 68 | 39 to 111 |

| Pacific | 168 | 167 to 169 | 114 | 106 to 123 | 82 | 79 to 85 | 105 | 102 to 109 | 82 | 80 to 85 | 99 | 94 to 104 | 83 | 78 to 88 |

AMR indicates age‐adjusted mortality rates; NHW, non‐Hispanic white.

Table 4.

Cerebrovascular Disease AMR Per 100 000 Population by Sex and Race/Ethnicity, 2003–2011

| Cerebrovascular Disease | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHW | Asian Indian | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese | ||||||||

| AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | AMR | 95% CI | |

| Male | ||||||||||||||

| New.England | 52 | 51 to 53 | 18 | 7 to 41 | 32 | 17 to 56 | 50 | 22 to 100 | 43 | 5 to 155 | 25 | 4 to 88 | 42 | 12 to 109 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 49 | 48 to 50 | 35 | 31 to 40 | 30 | 28 to 33 | 41 | 33 to 49 | 29 | 17 to 48 | 34 | 28 to 42 | 46 | 30 to 70 |

| E.N.Central | 64 | 63 to 65 | 43 | 35 to 51 | 44 | 37 to 53 | 52 | 42 to 63 | 41 | 29 to 57 | 46 | 34 to 60 | 46 | 29 to 69 |

| W.N.Central | 65 | 64 to 66 | 27 | 14 to 46 | 35 | 22 to 53 | 57 | 33 to 93 | 25 | 8 to 60 | 22 | 6 to 63 | 53 | 36 to 75 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 56 | 55 to 57 | 38 | 31 to 47 | 46 | 37 to 56 | 47 | 38 to 57 | 15 | 5 to 37 | 22 | 15 to 30 | 29 | 21 to 39 |

| W.S.Central | 69 | 68 to 70 | 43 | 33 to 54 | 57 | 48 to 68 | 61 | 47 to 79 | 56 | 29 to 99 | 54 | 36 to 80 | 64 | 55 to 75 |

| Mountain | 54 | 53 to 56 | 47 | 22 to 90 | 45 | 30 to 64 | 51 | 38 to 69 | 69 | 49 to 95 | 43 | 17 to 93 | 43 | 21 to 79 |

| Pacific | 66 | 65 to 67 | 44 | 39 to 50 | 59 | 57 to 62 | 78 | 75 to 81 | 70 | 66 to 73 | 53 | 48 to 58 | 57 | 52 to 62 |

| Female | ||||||||||||||

| New.England | 58 | 57 to 59 | 17 | 6 to 38 | 50 | 31 to 76 | 37 | 17 to 73 | 17 | 5 to 50 | 51 | 20 to 111 | 28 | 7 to 76 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 51 | 50 to 52 | 32 | 28 to 37 | 34 | 31 to 37 | 35 | 30 to 41 | 29 | 21 to 39 | 39 | 33 to 46 | 34 | 21 to 53 |

| E.N.Central | 70 | 69 to 71 | 53 | 45 to 62 | 49 | 41 to 57 | 44 | 37 to 51 | 45 | 36 to 56 | 61 | 50 to 74 | 51 | 34 to 73 |

| W.N.Central | 72 | 71 to 73 | 49 | 31 to 75 | 64 | 47 to 86 | 78 | 56 to 105 | 45 | 30 to 66 | 66 | 41 to 101 | 60 | 43 to 82 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 61 | 60 to 62 | 32 | 25 to 40 | 37 | 30 to 46 | 50 | 43 to 59 | 36 | 28 to 47 | 25 | 19 to 33 | 28 | 21 to 37 |

| W.S.Central | 80 | 79 to 81 | 56 | 46 to 69 | 40 | 32 to 48 | 49 | 40 to 61 | 46 | 35 to 60 | 59 | 45 to 76 | 59 | 51 to 69 |

| Mountain | 65 | 63 to 66 | 24 | 8 to 58 | 40 | 27 to 59 | 50 | 39 to 64 | 49 | 38 to 66 | 55 | 32 to 90 | 49 | 26 to 86 |

| Pacific | 73 | 72 to 74 | 47 | 42 to 53 | 55 | 53 to 57 | 59 | 57 to 62 | 55 | 53 to 58 | 55 | 51 to 59 | 58 | 54 to 62 |

AMR indicates age‐adjusted mortality rates; NHW, non‐Hispanic white.

As relative comparisons, there was greater variability across division for ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, with close to double or greater differences in mortality rates by division within all Asian American subgroups. For ischemic heart disease, the highest AMRs were observed in Asian Indian men (215; 95% CI, 204–227 per 100 000 population) and women (150; 95% CI, 140–160 per 100 000 population) in the Mid‐Atlantic division and lowest in Korean men (36; 95% CI, 27–47 per 100 000 population) and women in the South Atlantic (25; 95% CI, 18–33 per 100 000 population). For cerebrovascular disease, Filipino men in Pacific (78; 95% CI, 75–81 per 100 000) and Filipino women in the Western North Central division (78; 95% CI, 56–105 per 100 000) had the highest AMRs whereas Japanese men in the South Atlantic (15; 95% CI, 5–37 per 100 000 population) and Japanese women (17; 95% CI, 5–50 per 100 000 population) and Asian Indian women (17; 95% CI, 6–38 per 100 000 population) in New England had the lowest AMRs across the 6 Asian American subgroups.

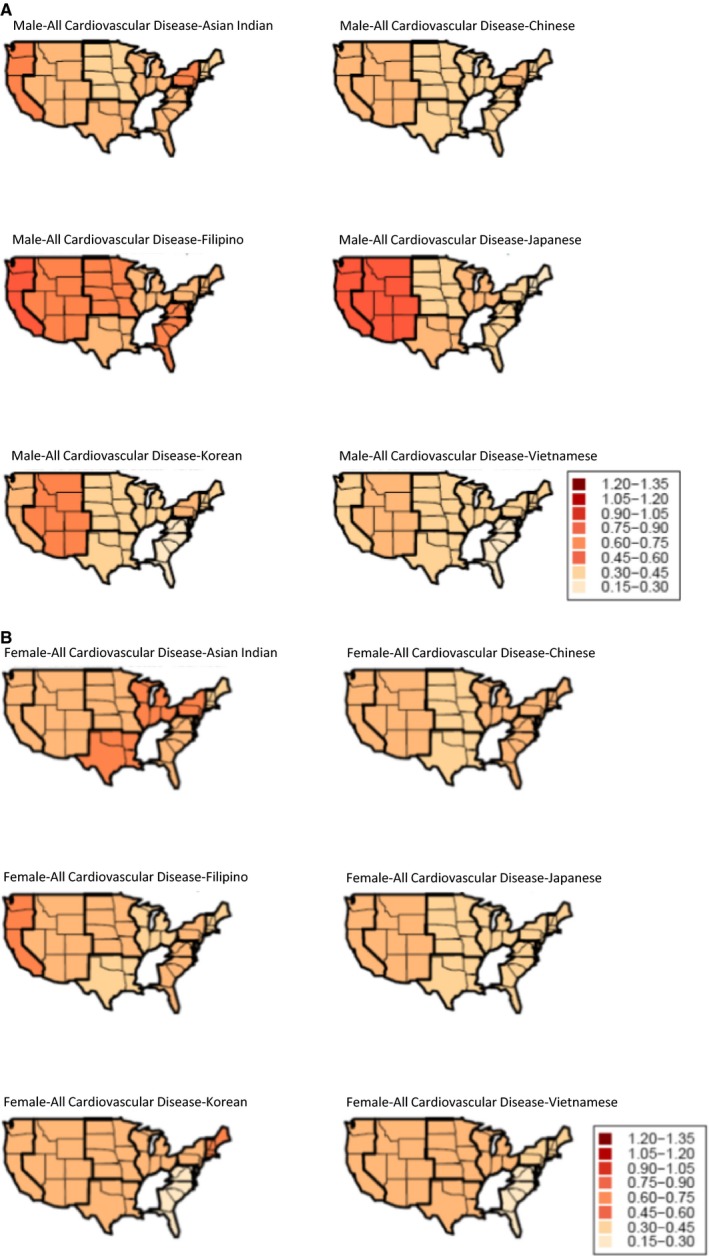

Age‐Adjusted CVD Mortality Rate Ratio

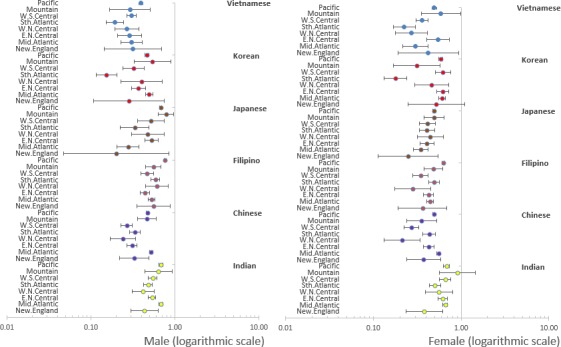

AMRRs were calculated to better compare the age‐adjusted CVD mortality rates in Asian American subgroups with non‐Hispanic whites as the reference group in each Census division. The reason for this focus of our analysis and presentation of data is to determine whether the geographical variation among Asian American subgroups differed from those of non‐Hispanic whites. We present the AMRs in 2 ways: first, in the map in Figure 1 and forest plot in Figures 2 and 3 and, second, in Tables 5, 6 through 7 that include estimated 95% CIs that allow an assessment of the stability of the mortality ratios. Asian American subgroups had lower age‐standardized mortality rates for total CVD (Figure 1 and Table 5) and specifically for ischemic heart disease (Figure 2 and Table 6) in both men and women than their non‐Hispanic white counterparts in the same division (AMRR<1). For almost all divisions and groups, the 95% CIs did not include one, consistent with the hypothesis that rates of CVD and ischemic heart disease across all divisions are lower for all 6 Asian American subgroups (Tables 5 and 6). The only exceptions to this were for ischemic disease mortality for Asian Indian women in the Mountain division (0.91; 95% CI, 0.56–1.46) and for Korean women living in New England (0.52; 95% CI, 0.25–1.10).

Figure 1.

A, Age‐adjusted CVD mortality rate ratios/AMRR for Asian subgroups using non‐Hispanic whites as a reference group, males, 2003–2011. B, Age‐adjusted CVD mortality rate ratios/AMRR for Asian subgroups using non‐Hispanic whites as reference group, females, 2003–2011. AMRR indicates age‐adjusted CVD mortality rate ratios; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Figure 2.

Age‐adjusted ischemic mortality rate ratios/AMRR for Asian subgroups using non‐Hispanic whites as a reference group, by sex. Sth.Atlantic indicates South Atlantic; W.N.Central, West North Central States; W.S.Central, West South Central. AMRR indicates age‐adjusted CVD mortality rate ratios.

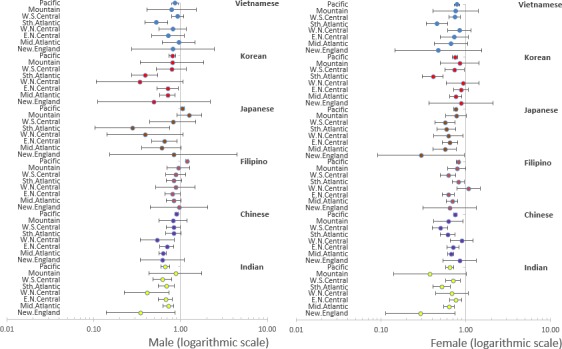

Figure 3.

Age‐adjusted cerebrovascular disease mortality rate ratios/AMRR for Asian subgroups using non‐Hispanic whites as a reference group, by sex. Sth.Atlantic indicates South Atlantic; W.N.Central, West North Central States; W.S.Central, West South Central. AMRR indicates age‐adjusted CVD mortality rate ratios.

Table 5.

Age‐Adjusted CVD Mortality Rate Ratios (AMRR) for Asian Subgroups Using NHW as a Reference Group With 95% CI, 2003–2011

| Asian Indian | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | |

| Male | ||||||||||||

| New.England | 0.36 | 0.27 to 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.29 to 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.37 to 0.73 | 0.25 | 0.09 to 0.63 | 0.35 | 0.19 to 0.64 | 0.41 | 0.25 to 0.67 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 0.62 | 0.59 to 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.48 to 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.51 to 0.59 | 0.31 | 0.25 to 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.45 to 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.31 to 0.46 |

| E.N.Central | 0.52 | 0.48 to 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.34 to 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.45 to 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.46 to 0.60 | 0.41 | 0.36 to 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.32 to 0.49 |

| W.N.Central | 0.42 | 0.34 to 0.52 | 0.30 | 0.24 to 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.51 to 0.79 | 0.44 | 0.31 to 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.25 to 0.59 | 0.39 | 0.32 to 0.48 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 0.51 | 0.47 to 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.39 to 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.56 to 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.26 to 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.16 to 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.21 to 0.28 |

| W.S.Central | 0.53 | 0.48 to 0.58 | 0.37 | 0.33 to 0.40 | 0.54 | 0.48 to 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.42 to 0.71 | 0.41 | 0.33 to 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.38 to 0.45 |

| Mountain | 0.57 | 0.43 to 0.76 | 0.54 | 0.45 to 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.62 to 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.74 to 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.49 to 0.93 | 0.48 | 0.35 to 0.66 |

| Pacific | 0.60 | 0.57 to 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.52 to 0.54 | 0.83 | 0.82 to 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.75 to 0.78 | 0.50 | 0.48 to 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.43 to 0.47 |

| Female | ||||||||||||

| New.England | 0.35 | 0.25 to 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.37 to 0.62 | 0.41 | 0.28 to 0.60 | 0.34 | 0.22 to 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.43 to 1.00 | 0.42 | 0.25 to 0.70 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 0.60 | 0.57 to 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.51 to 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.44 to 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.34 to 0.44 | 0.58 | 0.54 to 0.62 | 0.35 | 0.27 to 0.43 |

| E.N.Central | 0.62 | 0.57 to 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.43 to 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.41 to 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.37 to 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.53 to 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.39 to 0.58 |

| W.N.Central | 0.59 | 0.47 to 0.74 | 0.45 | 0.37 to 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.40 to 0.62 | 0.43 | 0.35 to 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.39 to 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.37 to 0.55 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 0.51 | 0.46 to 0.56 | 0.48 | 0.43 to 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.51 to 0.60 | 0.41 | 0.36 to 0.47 | 0.23 | 0.20 to 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.25 to 0.35 |

| W.S.Central | 0.62 | 0.56 to 0.68 | 0.37 | 0.33 to 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.37 to 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.38 to 0.50 | 0.58 | 0.50 to 0.66 | 0.49 | 0.45 to 0.53 |

| Mountain | 0.59 | 0.42 to 0.84 | 0.52 | 0.43 to 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.47 to 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.52 to 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.38 to 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.37 to 0.71 |

| Pacific | 0.60 | 0.56 to 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.54 to 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.64 to 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.57 to 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.57 to 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.49 to 0.53 |

CVD indicates cardiovascular disease; NHW, non‐Hispanic whites.

Table 6.

Age‐Adjusted Ischemic Heart Disease Mortality Rate Ratios (AMRR) for Asian Subgroups Using NHW as a Reference Group With 95% CI, 2003–2011

| Asian Indian | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | |

| Male | ||||||||||||

| New.England | 0.43 | 0.30 to 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.22 to 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.35 to 0.88 | 0.20 | 0.05 to 0.85 | 0.28 | 0.11 to 0.75 | 0.31 | 0.14 to 0.69 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 0.68 | 0.64 to 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.50 to 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.48 to 0.58 | 0.28 | 0.20 to 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.44 to 0.54 | 0.31 | 0.23 to 0.41 |

| E.N.Central | 0.53 | 0.48 to 0.59 | 0.31 | 0.27 to 0.35 | 0.44 | 0.38 to 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.44 to 0.63 | 0.37 | 0.30 to 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.21 to 0.40 |

| W.N.Central | 0.42 | 0.31 to 0.56 | 0.24 | 0.17 to 0.34 | 0.61 | 0.45 to 0.83 | 0.48 | 0.30 to 0.75 | 0.40 | 0.23 to 0.71 | 0.27 | 0.19 to 0.37 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 0.48 | 0.42 to 0.54 | 0.33 | 0.29 to 0.39 | 0.58 | 0.52 to 0.66 | 0.33 | 0.22 to 0.49 | 0.15 | 0.12 to 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.15 to 0.24 |

| W.S.Central | 0.54 | 0.48 to 0.61 | 0.27 | 0.23 to 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.39 to 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.36 to 0.74 | 0.32 | 0.24 to 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.27 to 0.35 |

| Mountain | 0.64 | 0.44 to 0.92 | 0.46 | 0.36 to 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.45 to 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.63 to 0.96 | 0.54 | 0.32 to 0.89 | 0.29 | 0.17 to 0.51 |

| Pacific | 0.68 | 0.64 to 0.72 | 0.47 | 0.45 to 0.48 | 0.76 | 0.74 to 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.65 to 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.44 to 0.49 | 0.39 | 0.37 to 0.42 |

| Female | ||||||||||||

| New.England | 0.38 | 0.24 to 0.61 | 0.37 | 0.24 to 0.58 | 0.36 | 0.19 to 0.69 | 0.25 | 0.11 to 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.25 to 1.10 | 0.42 | 0.19 to 0.93 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 0.66 | 0.61 to 0.70 | 0.55 | 0.53 to 0.58 | 0.44 | 0.40 to 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.28 to 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.55 to 0.66 | 0.30 | 0.22 to 0.42 |

| E.N.Central | 0.62 | 0.55 to 0.70 | 0.43 | 0.37 to 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.37 to 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.34 to 0.49 | 0.62 | 0.53 to 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.40 to 0.73 |

| W.N.Central | 0.56 | 0.39 to 0.80 | 0.21 | 0.13 to 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.17 to 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.32 to 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.29 to 0.73 | 0.27 | 0.18 to 0.42 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 0.50 | 0.43 to 0.59 | 0.43 | 0.37 to 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.43 to 0.56 | 0.41 | 0.33 to 0.50 | 0.18 | 0.13 to 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.17 to 0.30 |

| W.S.Central | 0.66 | 0.57 to 0.75 | 0.27 | 0.22 to 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.28 to 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.33 to 0.51 | 0.62 | 0.51 to 0.76 | 0.36 | 0.31 to 0.42 |

| Mountain | 0.91 | 0.56 to 1.46 | 0.35 | 0.24 to 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.38 to 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.38 to 0.63 | 0.31 | 0.17 to 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.35 to 0.99 |

| Pacific | 0.68 | 0.63 to 0.73 | 0.49 | 0.47 to 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.61 to 0.65 | 0.49 | 0.47 to 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.56 to 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.46 to 0.53 |

NHW indicates non‐Hispanic whites.

Table 7.

Age‐Adjusted Cerebrovascular Disease Mortality Rate Ratios (AMRR) for Asian Subgroups Using NHW as a Reference Group With 95% CI, 2003–2011

| Asian Indian | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | AMRR | 95% CI | |

| Male | ||||||||||||

| New.England | 0.34 | 0.14 to 0.86 | 0.62 | 0.34 to 1.11 | 0.96 | 0.45 to 2.06 | 0.82 | 0.15 to 4.50 | 0.49 | 0.11 to 2.19 | 0.82 | 0.27 to 2.46 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 0.72 | 0.63 to 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.57 to 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.69 to 1.01 | 0.60 | 0.36 to 1.01 | 0.70 | 0.57 to 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.62 to 1.47 |

| E.N.Central | 0.67 | 0.55 to 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.58 to 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.66 to 0.99 | 0.65 | 0.46 to 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.54 to 0.95 | 0.72 | 0.47 to 1.11 |

| W.N.Central | 0.41 | 0.23 to 0.74 | 0.54 | 0.34 to 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.52 to 1.47 | 0.39 | 0.14 to 1.06 | 0.34 | 0.11 to 1.07 | 0.81 | 0.57 to 1.17 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 0.68 | 0.55 to 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.67 to 1.01 | 0.84 | 0.68 to 1.03 | 0.28 | 0.10 to 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.27 to 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.39 to 0.71 |

| W.S.Central | 0.61 | 0.48 to 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.69 to 0.99 | 0.88 | 0.68 to 1.15 | 0.81 | 0.44 to 1.50 | 0.78 | 0.52 to 1.17 | 0.93 | 0.79 to 1.08 |

| Mountain | 0.87 | 0.43 to 1.75 | 0.82 | 0.57 to 1.19 | 0.94 | 0.70 to 1.28 | 1.26 | 0.91 to 1.75 | 0.8 | 0.34 to 1.85 | 0.78 | 0.41 to 1.51 |

| Pacific | 0.67 | 0.59 to 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.86 to 0.93 | 1.18 | 1.14 to 1.24 | 1.05 | 1.00 to 1.11 | 0.8 | 0.73 to 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.79 to 0.93 |

| Female | ||||||||||||

| New.England | 0.29 | 0.11 to 0.74 | 0.85 | 0.54 to 1.34 | 0.64 | 0.31 to 1.33 | 0.30 | 0.09 to 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.37 to 2.08 | 0.47 | 0.15 to 1.53 |

| Mid.Atlantic | 0.63 | 0.55 to 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.61 to 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.59 to 0.80 | 0.57 | 0.41 to 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.65 to 0.89 | 0.67 | 0.43 to 1.05 |

| E.N.Central | 0.76 | 0.64 to 0.89 | 0.70 | 0.60 to 0.83 | 0.63 | 0.53 to 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.52 to 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.72 to 1.06 | 0.73 | 0.50 to 1.06 |

| W.N.Central | 0.68 | 0.44 to 1.07 | 0.89 | 0.66 to 1.21 | 1.08 | 0.78 to 1.48 | 0.62 | 0.42 to 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.59 to 1.44 | 0.84 | 0.61 to 1.15 |

| Sth.Atlantic | 0.52 | 0.41 to 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.50 to 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.70 to 0.96 | 0.59 | 0.45 to 0.76 | 0.41 | 0.31 to 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.34 to 0.61 |

| W.S.Central | 0.70 | 0.57 to 0.86 | 0.50 | 0.40 to 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.50 to 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.43 to 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.56 to 0.96 | 0.74 | 0.63 to 0.86 |

| Mountain | 0.38 | 0.14 to 1.01 | 0.62 | 0.42 to 0.93 | 0.78 | 0.61 to 0.99 | 0.77 | 0.58 to 1.01 | 0.85 | 0.50 to 1.44 | 0.76 | 0.41 to 1.40 |

| Pacific | 0.64 | 0.57 to 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.72 to 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.78 to 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.72 to 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.70 to 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.73 to 0.85 |

NHW indicates non‐Hispanic whites.

The most heterogeneity was observed for cerebrovascular disease (Figure 3 and Table 7). For Filipino men there was 1 division with lower mortality of cerebrovascular disease, for Japanese men there were 2 divisions with lower mortality, for Korean men and women there were 4 divisions with lower mortality each, and for Vietnamese men and women there were 2 and 3 divisions with lower mortality, respectively. Higher cerebrovascular disease mortality rates relative to non‐Hispanic whites were observed in Filipino men (AMRR=1.18; 95% CI, 1.14–1.24) and Japanese men (AMRR=1.05; 95% CI, 1.00–1.11) in the Pacific division.

CVD Cause Subtype Analysis of the East South Central Division

There was insufficient data on all 6 Asian American subgroups in the East South Central division attributed to late adoption of the 2003 standard in states in this division. For this subgroup analysis of the East South Central division, part of the well‐known “stroke belt,” we used data on subgroups with categories present before the 2003 revision of the US death certificate (Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, and non‐Hispanic white decedents). Consistent with the literature, non‐Hispanic whites had particularly high CVD mortality in this division. The AMRs for CVD overall (men, 534 per 100 000 population; women, 413 per 100 000 population) and cerebrovascular disease (men, 73 per 100 000 population; women, 81 per 100 000 population) were highest in the East South Central division as compared with all of the Census divisions (Table 8). However, this pattern was not found for Chinese, Filipino, or Japanese subgroups.

Table 8.

Age‐Adjusted CVD Mortality Rates Per 100 000 Population in the East South Central Division by Sex and Race/Ethnicity, 2003–2011

| NHW | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVD | Ischemic | Cerebro | CVD | Ischemic | Cerebro | CVD | Ischemic | Cerebro | CVD | Ischemic | Cerebro | |

| Male | 534 | 286 | 73 | 182 | 74 | 44 | 304 | 156 | 61 | 141 | 98 | 0 |

| Female | 413 | 175 | 81 | 168 | 48 | 54 | 167 | 62 | 39 | 90 | 36 | 22 |

CVD indicates cardiovascular disease; NHW, non‐Hispanic white.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to investigate geographical patterns of CVD mortality among Asian American subgroups in the United States. Although our study cannot specifically test the relative contribution of the processes leading to regional differences in CVD mortality among Asian American subgroups, our description of these differences is a first step toward understanding the importance of environmental context and migration patterns for influencing CVD mortality in these populations. Our analysis showed that the geographical variation in CVD mortality among Asian American subgroups and across CVD subtypes was largely similar to non‐Hispanic whites. This suggests that differential migration to particular parts of the country by different Asian American subgroups is not likely to be the primary explanation for geographical differences in cardiovascular health for Asian American subgroups. However, this was not universal. For some Asian American subgroups, we found different geographical patterns. The Pacific division was consistently identified as having the highest AMRs of CVD and CVD subtypes among most Asian American subgroups, followed by the Mid‐Atlantic division. Approximately 80% of Filipino CVD deaths and 90% of Japanese CVD deaths occur in the Pacific division. Geographical clustering of CVD mortality among Asians in this division may provide direct evidence of culturally related environmental factors in this specific geographical area or in differential patterns of migration. It is also noteworthy that we observed heterogeneity in CVD mortality rates across the 6 largest Asian American subgroups. Currently, Asian American subgroups have often been aggregated together in national statistics, and this study helps to confirm the importance of using disaggregated data. Although Asians are often thought to be healthier than other minority groups and non‐Hispanic whites, special attention should be paid to Asian American subgroups with established higher CVD risk, such as Asian Indians, Japanese, and Filipinos.6

Another interesting finding was that Asian American subgroups may have similar or even greater disease burden from cerebrovascular disease compared with non‐Hispanic whites, depending on the census division of residence. In particular, Filipino men and women and Japanese men had higher age‐adjusted mortality rates of cerebrovascular disease compared with their non‐Hispanic white counterparts in the Pacific, West North Central, and Mountain divisions, respectively. Compared with non‐Hispanic whites, Filipino men in the Pacific division had 18% higher risk and Japanese men had 5% higher risk in the Pacific division of dying from cerebrovascular disease after standardizing rates for differences in age distribution. Previous studies have demonstrated that hypertension prevalence was higher in Filipino, Japanese, and Vietnamese populations in the United States,14 but the geographical variation in relative CVD mortality across racial/ethnic groups has not been previously reported. Further research is needed regarding hypertension treatment and management of cerebrovascular disease among these Asian American subgroups, which may need to account for geographical variation.

Underlying causes of the observed variation across racial/ethnic groups and geographical divisions remain unknown and could not be tested in our analysis. Potential contributing factors include genetic predispositions, environmental interactions, cultural practice/lifestyle, and immigration history, with all of these explanations attributed to either selective migration or the effects of place. Work on geographical differences for genetic risk of CVD has found to have very little variation for non‐Hispanic whites, making this explanation seem unlikely, but this has not been examined among Asian Americans.15 The Ni‐Hon‐San study investigated CVD rates and risk factors among Japanese men living in 3 cities: Hiroshima, Japan, Honolulu, Hawaii, and San Francisco, California. It showed that coronary heart disease and stroke mortality rates were highest among California participants, followed by Hawaii, and lowest among participants living in Japan.16 It provides important evidence that populations with a common ethnic background had different CVD outcomes potentially attributed to exposure to different geographical and cultural environments. Similar to this study, we also found variations of CVD mortality rates across Census divisions within Asian American subgroups. Additionally, we found geographical variation in CVD among Asian American subgroups when compared with non‐Hispanic whites from the same geographical area. In particular, a greater CVD burden was observed in the Pacific and Mountain divisions, whereas comparable or lower burden was found in the traditional stroke belt. This suggests that environmental factors may impact Asian Americans differentially and adds to the existing body of literature that demonstrates the interaction and influence that built environments play on health outcomes for all racial/ethnic groups. To address these questions, future studies should test whether county‐level social, economic, health services, environmental, and demographic factors explain survival differences in CVD between Asian American subgroups and as compared with non‐Hispanic whites.

There are several considerations when interpreting these findings. First, we used information from the national death records to identify deaths caused by CVD, which is subject to misclassification. Although this is the best available information, we should be aware of the challenge of determining the underlying causes of death, in particular for different CVD subgroups. A previous study indicates potential errors and inaccuracy of race/ethnicity information on death certificates.17 This could lead to an over‐ or underestimate of CVD mortality rates among the racial/ethnic subgroups. Second, our analysis is limited to the Census divisions because of insufficient information at any smaller geographical unit. Thus, we were not able to further explore more granular‐level geographical variations within the Census divisions (eg, county level). It is possible that there are additional geographical variations uncaptured by the geographical unit of the Census division. Furthermore, the observed differences in CVD mortality were not adjusted for several important baseline characteristics, including comorbidities and socioeconomic status because of limited data availability. Finally, information about Asian American subgroups in the East South Central division, where CVD is especially prevalent among non‐Hispanic white and black populations, was unavailable because of sparse data as a result of late adoption of the 2003 standard of death certificate in the states in this division, and there are relatively fewer Asian Americans overall in this region.

Conclusion

In this analysis, we characterized geographical variation in CVD mortality in Asian American subgroups and provided critical documentation of the geographical burden of CVD in the United States. An important strength of this study is the full national mortality data disaggregated by Asian American subgroups, Census division, and CVD subtype, providing an opportunity to detect the potential impact of geographical factors on CVD mortality among these understudied Asian American subgroup populations. Geographical patterns for CVD overall and ischemic heart disease were mostly similar for Asian American subgroups compared with non‐Hispanic whites, but there were substantial differences for cerebrovascular disease. In particular, there were higher mortality rates for Filipino men and Japanese men in the Pacific division, the division of the country with the largest population of these groups. These findings lead to new directions for etiological research for geographically related causes of CVD and, in this case, how these contributing factors may be differentially impacting cerebrovascular disease in certain Asian American subgroups. It can also help prioritize resources of prevention and treatment to areas of the country where they are most needed.

Sources of Funding

The research activities of the authors were supported by a grant from NIH/NIMHD (R01 MD 007012).

Disclosures

None.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005597 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005597.)28701306

References

- 1. Underlying cause of death 1999–2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html. Accessed May 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Atlas of heart disease and stroke. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Available at: http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/resources/atlas/en/. Accessed May 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. The Asian population: 2000. Census 2000 brief. Available at: https://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/c2kbr01-16.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2006.

- 4. Health of Asian or Pacific Islander Population. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asian-health.htm. Accessed July 3, 2017.

- 5. Yi SS, Kwon SC, Sacks R, Trinh‐Shevrin C. Commentary: persistence and health‐related consequences of the model minority stereotype for Asian Americans. Ethn Dis. 2016;26:133–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jose PO, Frank AT, Kapphahn KI, Goldstein BA, Eggleston K, Hastings KG, Cullen MR, Palaniappan LP. Cardiovascular disease mortality in Asian Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2486–2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holland AT, Wong EC, Lauderdale DS, Palaniappan LP. Spectrum of cardiovascular diseases in Asian‐American racial/ethnic subgroups. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:608–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clarke CG, Peach C, Vertovec S. South Asians Overseas: Migration and Ethnicity. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 9. 2010 geographic terms and concepts—census divisions and census regions. US Census Bureau Geography; Available at: https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_census_divreg.html. Accessed May 1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Research Council Committee on National S . Vital Statistics: Summary of a Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2009. Copyright 2009 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. [Google Scholar]

- 11. R 3.1.1 is released. R‐statistics blog. Available at: http://www.r-statistics.com/2014/07/r-3-1-1-is-released-and-how-to-quickly-update-it-on-windows-os/. Accessed May 1, 2016.

- 12. Tomas J, Aragon MPF, Wollschlaeger D. Cran—package epitools: R package for epidemiologic data and graphics. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/epitools/index.html. Accessed May 1, 2016.

- 13. Becker RA, Wilks AR, Brownrigg R, Minka TP, Deckmyn A. Cran—package maps. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/maps/index.html. Accessed May 1, 2016.

- 14. Zhao B, Jose PO, Pu J, Chung S, Ancheta IB, Fortmann SP, Palaniappan LP. Racial/ethnic differences in hypertension prevalence, treatment, and control for outpatients in northern California 2010–2012. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:631–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rehkopf DH, Domingue BW, Cullen MR. The geographic distribution of genetic risk as compared to social risk for chronic diseases in the United States. Biodemography Soc Biol. 2016;62:126–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Benfante R. Studies of cardiovascular disease and cause‐specific mortality trends in Japanese‐American men living in Hawaii and risk factor comparisons with other Japanese populations in the Pacific region: a review. Hum Biol. 1992;64:791–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wexelman BA, Eden E, Rose KM. Survey of New York City resident physicians on cause‐of‐death reporting, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]