Abstract

Background

In this study, we sought to investigate the 2‐year prognostic impact of B‐type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels at discharge, following transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Methods and Results

We enrolled 1094 consecutive patients who underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement between 2013 and 2016. Study patients were stratified into 2 groups according to survival classification and regression tree analysis (high versus low BNP groups). We evaluated the impact of high BNP on 2‐year mortality compared with that of low BNP using a multivariable Cox model, and assessed whether this stratification would improve predictive accuracy for determining 2‐year mortality by assessing time‐dependent net reclassification improvement and integrated discrimination improvement. The median age of patients was 85 years (quartile 82–88), and 29.2% of the study population were men. The median Society of Thoracic Surgeons score was 6.8 (4.7–9.5), and BNP at discharge was 186 (93–378) pg/mL. All‐cause mortality following discharge was 7.9% (95% CI, 5.8–9.9%) at 1 year and 15.4% (95% CI, 11.6–19.0%) at 2 years. The survival classification and regression tree analysis revealed that the discriminating BNP level to discern 2‐year mortality was 202 pg/mL, and that elevated BNP had a statistically significant impact on outcomes, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.28 (1.36–3.82, P=0.002). The time‐dependent net reclassification improvement (P=0.047) and integrated discrimination improvement (P=0.029) analysis revealed that the incorporation of BNP stratification with other clinical variables significantly improved predictive accuracy for 2‐year mortality.

Conclusions

Elevation of BNP at discharge is associated with 2‐year mortality after transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Keywords: aortic stenosis, brain natriuretic peptide, mortality, rehospitalization, transcatheter aortic valve implantation

Subject Categories: Aortic Valve Replacement/Transcather Aortic Valve Implantation, Biomarkers, Valvular Heart Disease, Heart Failure, Mortality/Survival

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Elevation of brain natriuretic peptide at discharge is associated with 2‐year all‐cause mortality and hospitalization for heart failure after transcatheter aortic valve replacement, and significantly improves predictive accuracy for 2‐year all‐cause mortality.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Patients with brain natriuretic peptide >202 pg/mL at discharge should be carefully monitored to help avoid the need for hospitalization for heart failure and/or decrease the potential for mortality.

Introduction

Severe aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common cause of left ventricular outflow impairment. It is associated with high cardiovascular mortality, since its inhibition of outflow results in the reduction of stroke volume and results in concomitant acute decompensated heart failure (HF).1, 2 For decades, surgical aortic valve replacement has been one of the best treatments and is correlated with the significant prolongation of life expectancy in patients with severe AS.2 In contrast, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has also recently been recognized as a viable therapeutic option in patients with high surgical risk, with the satisfactory midterm clinical outcome expanding the indication of TAVR to include patients at intermediate risk as candidates.3, 4, 5 B‐type natriuretic peptide (BNP) is a hormone released mainly by the cardiac monocytes of the left ventricle in response to pressure and volume overload.6 The utility of BNP to stratify long‐term mortality and/or cardiovascular risks has been established in patients with chronic HF, and some reports have even shown that BNP is a predictor of postoperative survival in patients with severe AS who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement.7, 8, 9, 10 Although previous reports have also evaluated the association between BNP levels and prognosis in patients with AS who had undergone TAVR, these reports demonstrated some limitations. For example, several studies were performed with only a small number of patients evaluated.11, 12, 13 Other limitations include the fact that only short‐term prognoses, such as 30‐day mortality, were assessed, or that most studies evaluated BNP on admission, prior to performance of the TAVR procedure.13, 14, 15 Since TAVR results in a rapid release of the left ventricle from pressure overload, and BNP levels decrease immediately after the procedure as a result of their ≈20‐minute half‐life, we speculated that BNP at discharge should be used for risk stratification of long‐term prognosis in patients who underwent TAVR.16 Lastly, only a few BNP studies focused on hospitalization caused by HF, following TAVR, although BNP is well‐known as an established biomarker of HF.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Hence, a study on the long‐term prognostic impact of BNP levels at discharge that includes a large number of patients after TAVR is warranted. The objective of the present study is to investigate the impact of BNP levels at discharge on 2‐year all‐cause mortality and hospitalization for HF, and to provide risk stratification in patients with severe AS who underwent TAVR via enrollment of the largest study population to date (n=1094) from the multicenter prospective registry of TAVR.

Methods

Study Population

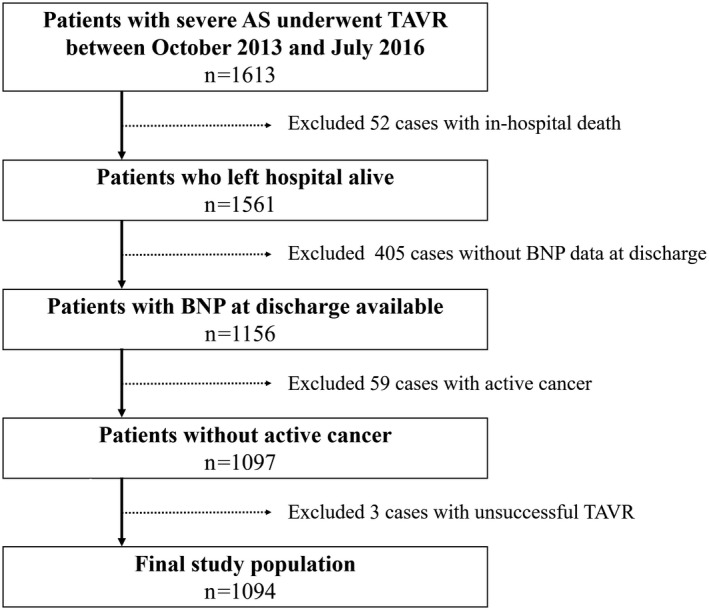

We analyzed data from 1094 patients who were enrolled in the OCEAN‐TAVI (Optimized Transcatheter Valvular Intervention–Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation) registry, who were discharged alive with procedural success and had a record of BNP at discharge without active cancer present between October 2013 and July 2016 (Figure 1). The OCEAN‐TAVI is a prospective, multicenter, observational registry of symptomatic patients with severe AS who undergo TAVR using the Edwards Sapien XT/3 Transcatheter Heart Valve (Edwards Lifesciences) or the Medtronic CoreValve Revalving System (Medtronic, Inc) at 14 collaborating hospitals located in Japan. This trial was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry, as accepted by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (UMIN‐ID;000020423). Inclusion criteria were: (1) the presence of symptoms; (2) the presence of degenerative AS; (3) a mean gradient of >40 mm Hg or a jet velocity of >4.0 m/s; and/or (4) an aortic valve area <1.0 cm2 (or an effective orifice area index <0.6 cm2/m2). Indication for TAVR was determined based on the clinical consensus of a heart team comprised of cardiac surgeons, interventional cardiologists, anesthesiologists, and imaging specialists. Exclusion criteria were: (1) presence of a noncalcified aortic valve; (2) failed surgical bioprosthesis implantation; (3) presence of severe aortic regurgitation; and/or (4) the current use of dialysis. The study protocol was developed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of each participating hospital. All patients gave written informed consent prior to participating in this study. The authors had full access to the data and were responsible for its integrity. All authors read and agreed to the article as written.

Figure 1.

Patient selection flow. AS indicates aortic stenosis; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Blood Sampling and BNP Measurement

Blood samples were drawn from the antecubital or other accessible veins such as the dorsal hand vein and collected in chilled EDTA test tubes at the time of hospital discharge following performance of TAVR. BNP levels were measured from an EDTA blood sample using a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (ARCHITECT BNP assay, Abbot Laboratories Diagnostics Division; ADOVIA Centaur BNP assay, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc), ELISA (E‐test TOSOH II BNP, Tosoh Bioscience) or chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (AIA‐packCL BNP, Tosoh Bioscience; PATHFAST®BNP, LSI Medience Corporation; Lumipulse Prestol II, FUJIREBIO Inc). Each sample was measured at each institutional laboratory that it was taken in and was not measured at a core laboratory.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

All data shown in the tables and figures were collected from the OCEAN‐TAVI multicenter prospective registry database. We set the primary end point as 2‐year all‐cause mortality after hospital discharge, since many previous studies also set the mortality as their primary end point.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 The secondary end point for this study was set as 2‐year hospitalization for HF, where the necessity of hospitalization was determined based on the attending physician's discretion without any prespecified criteria. Continuous variables were summarized using medians and interquartile range (quartiles 1–3), and categorical variables were summarized by means of counts and percentages. To provide a simple risk stratification model, we first classified our study patients into 2 groups according to survival classification and regression tree (CART) analysis for 2‐year mortality.18, 19 We performed survival CART analysis using the ctree function of the party package using 2‐year all‐cause mortality as an outcome measure with BNP levels at discharge as an independent variable. The purpose was to identify the cutoff value of BNP for the risk stratification of 2‐year all‐cause mortality. After the survival CART analysis revealed the cutoff BNP value at discharge, we divided the study population into 2 groups based on this result to discern 2‐year all‐cause mortality. Thus, patients with BNP levels lower than or equal to the cutoff value were defined as the “low BNP group,” whereas those with BNP levels greater than the cutoff value were defined as the “high BNP group.” We evaluated the impact of high BNP on end points as compared with that of low BNP using univariable and multivariable Cox regression models with a cross‐product term between BNP groups and sex for the assessment of sex difference with a P for interaction, including the following variables as possible confounders: Clinical Frailty Scale; Society of Thoracic Surgeons surgical mortality risk score; apical approach; postprocedural transthoracic echocardiographic indices, such as left ventricular ejection fraction; effective orifice area; mean aortic valve pressure gradient; the presence of moderate to severe aortic regurgitation; the presence of postprocedural acute kidney injury; and institution as a stratum. These confounders were determined clinically, considering the number of end points and multicollinearity. For example, information such as age, sex, and atrial fibrillation information were included in the analysis since they are used in the calculation of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons score. We also employed Akaike information criteria in order to select the best predictive Cox model for use. The incidence of each end point was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, with its 95% CI, and the difference between the BNP groups was evaluated using log‐rank test. Differences in continuous and categorical variables between BNP groups were compared using the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test or the chi‐square test, respectively. Furthermore, we assessed whether the BNP stratification information would improve predictive accuracy for each end point by assessing time‐dependent net reclassification improvement (NRI) and time‐dependent integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) using the above‐mentioned covariates as a basic model with or without BNP group information. Statistical analyses were performed using R software packages (version 3.1.1; R Development Core Team). The significance level of a statistical hypothesis testing was set at 0.05 and the alternative hypothesis was 2‐sided.

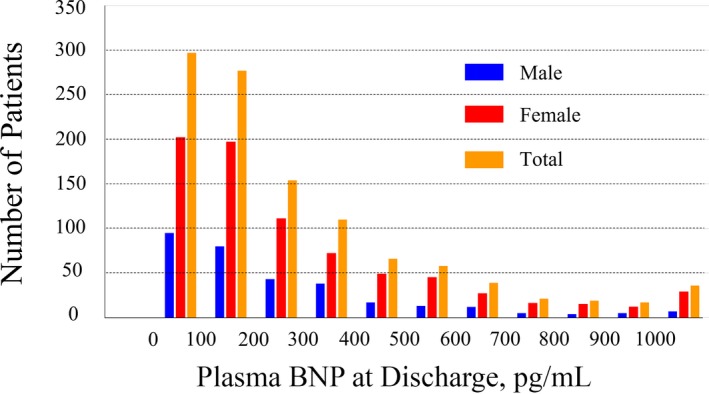

Results

The patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age of the study population was 85 years, and 29.2% of the patients who participated in this study were men. Almost all of the participants presented with New York Heart Association HF functional class II or higher. The median Canadian Study of Health and Aging's Clinical Frailty Scale value was 4. Evaluation of preoperative transthoracic echocardiograms showed that the median left ventricular ejection fraction was 62.0% and the median aortic valve area with Doppler method was 0.61 cm2 with a mean aortic valve pressure gradient of 48 mm Hg. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons was 6.8% and the logistic EURO score was 13.6% (Table 1). The median BNP level at discharge in the entire cohort was 186 pg/mL (quartile, 93–378) without a statistical difference between men and women (P=0.117), and the distribution is presented in Figure 2. BNP levels at discharge were 299 pg/mL (130–487 pg/mL) in patients who underwent the transapical approach versus 173 pg/mL (90–347 pg/mL) in patients who underwent the transfemoral approach (P<0.001). The median time from TAVR to BNP measurement was 8 days (6–14 days), and hospitalization length was 10 days (7–15 days).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Parameters | Missing | Total (N=1094) | Low BNP (n=576) | High BNP (n=518) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNP at discharge, pg/mL | 0 | ||||

| Total population | 186 (93–378) | 96 (60–140) | 399 (283–606) | <0.001 | |

| Men | 177 (87–343) | 92 (57–134) | 365 (291–568) | <0.001 | |

| Women | 188 (96–398) | 99 (60–144) | 411 (277–618) | <0.001 | |

| Time from TAVR to BNP, d | 0 | 8 (6–14) | 7 (6–12) | 9 (7–15) | <0.001 |

| Age, y | 0 | 85 (82–88) | 85 (81–87) | 86 (82–88) | <0.001 |

| Men | 0 | 319 (29.2) | 175 (30.4) | 144 (27.8) | 0.348 |

| BSA, m2 | 0 | 1.41 (1.30–1.52) | 1.43 (1.32–1.54) | 1.38 (1.28–1.50) | <0.001 |

| Atherosclerotic risks | |||||

| Hypertension | 0 | 854 (78.1) | 450 (78.1) | 404 (78.0) | 0.958 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0 | 482 (44.1) | 277 (48.1) | 205 (39.6) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 | 284 (26.0) | 139 (24.1) | 145 (28.0) | 0.146 |

| Current smoking | 0 | 26 (2.4) | 13 (2.3) | 13 (2.5) | 0.784 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 | 222 (20.3) | 80 (13.9) | 142 (27.4) | <0.001 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass graft | 0 | 76 (7.0) | 40 (6.9) | 36 (6.9) | 0.997 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 0 | 79 (7.2) | 37 (6.4) | 42 (8.1) | 0.283 |

| Previous ischemic stroke | 0 | 159 (14.5) | 80 (13.9) | 79 (15.3) | 0.523 |

| NYHA class | 0 | <0.001 | |||

| II | 482 (44.1) | 293 (50.9) | 189 (36.5) | ||

| III | 510 (46.6) | 243 (42.2) | 267 (51.5) | ||

| IV | 67 (6.1) | 20 (3.5) | 47 (9.1) | ||

| Clinical Frailty Scale | 0 | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–5) | <0.001 |

| Medical treatment on admission | |||||

| ACEI or ARB | 0 | 583 (53.3) | 317 (55.0) | 266 (51.4) | 0.223 |

| β‐Blocker | 0 | 346 (31.6) | 141 (24.5) | 205 (39.6) | <0.001 |

| Calcium blocker | 0 | 475 (43.4) | 255 (44.3) | 220 (42.5) | 0.549 |

| Diuretic | 0 | 588 (53.8) | 258 (44.8) | 330 (63.7) | <0.001 |

| Statin | 0 | 448 (41.0) | 253 (43.9) | 195 (37.6) | 0.035 |

| Laboratory data on admission | |||||

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 0 | 50.5 (37.8–63.5) | 54.8 (42.0–67.0) | 45.5 (33.6–59.0) | <0.001 |

| BNP, pg/mL | 4 | 260 (113–537) | 146 (74–294) | 447 (242–826) | <0.001 |

| TTE data before TAVR | |||||

| LV end‐diastolic diameter, mm | 1 | 44 (40–48) | 44 (40–47) | 44 (40–49) | 0.038 |

| LV end‐systolic diameter, mm | 3 | 28 (25–33) | 27 (24–31) | 29 (25–34) | <0.001 |

| LVEF, % | 0 | 62.0 (52.0–68.0) | 63.8 (55.0–68.3) | 60.0 (48.6–67.0) | <0.001 |

| Mean AVP gradient, mm Hg | 0 | 48 (38–61) | 49 (39–62) | 46 (37–60) | 0.038 |

| Peak AVP gradient, mm Hg | 2 | 82 (67–104) | 84 (67–105) | 81 (65–102) | 0.114 |

| AVA with Doppler, cm2 | 2 | 0.61 (0.50–0.72) | 0.63 (0.52–0.73) | 0.60 (0.49–0.71) | 0.001 |

| STS score | 0 | 6.8 (4.7–9.5) | 5.9 (4.3–8.4) | 7.7 (5.4–11.3) | <0.001 |

| Logistic Euro score | 0 | 13.6 (9.0–22.4) | 12.5 (8.4–19.8) | 15.5 (10.1–25.0) | <0.001 |

| Euro II score | 0 | 3.9 (2.3–6.2) | 3.4 (2.1–5.3) | 4.6 (2.8–7.5) | <0.001 |

Categorical variables are shown as numbers (percentages) and continuous variables are shown as medians (25–75 percentiles). ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; AVA, aortic valve area; AVP, aortic valve pressure; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; BSA, body surface area; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction by modified Simpson or Teichholz methods; NYHA, New York Heart Association; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeon; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography.

Figure 2.

Distribution of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) level at discharge after transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Table 2 shows the procedure‐related information. Most of the patients in this study received the SAPIEN XT valve (Edwards Lifesciences) with a median valve size of 23 mm. The percentage of patients who underwent the TAVR procedure with the transapical approach was 14.8%. Echocardiography revealed that the postprocedural mean aortic valve pressure gradient was 10.0 mm Hg and the effective orifice area was 1.60 cm2. Periprocedural complications including coronary occlusion, permanent pacemaker implantation, and acute kidney injury occurred in 0.9%, 8.3%, and 6.6% of the study's participants, respectively.

Table 2.

Procedural and Periprocedural Data

| Parameters | Missing | Total (N=1094) | Low BNP (n=576) | High BNP (n=518) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural data | |||||

| Apical approach | 0 | 162 (14.8) | 61 (10.6) | 101 (19.5) | <0.001 |

| Valve type | 0 | 0.264 | |||

| Edwards SAPIEN XT | 909 (83.1) | 485 (84.2) | 424 (81.9) | ||

| Edwards SAPIEN 3 | 97 (8.9) | 52 (9.0) | 45 (8.7) | ||

| Medtronic CoreValve | 88 (8.0) | 39 (6.8) | 49 (9.5) | ||

| Valve size, mm | 0 | 23 (23–26) | 23 (23–26) | 23 (23–26) | 0.763 |

| Fluoro time, min | 33 | 19 (15–25) | 19 (15–25) | 19 (15–25) | 0.811 |

| Procedure time, min | 0 | 78 (56–101) | 77 (54–98) | 81 (59–105) | 0.006 |

| Anesthesia time, min | 2 | 145 (112–173) | 143 (112–168) | 146 (112–178) | 0.158 |

| TTE data after TAVR | |||||

| LV end‐diastolic diameter, mm | 6 | 44 (40–48) | 43 (40–47) | 44 (41–49) | 0.002 |

| LV end‐systolic diameter, mm | 6 | 28 (25–32) | 27 (25–30) | 28 (25–33) | <0.001 |

| LVEF, % | 34 | 63.0 (54.8–68.3) | 64.0 (58.0–69.0) | 61.9 (51.0–67.5) | <0.001 |

| Mean AVP gradient, mm Hg | 9 | 10.0 (7.7–13.0) | 10.0 (8.0–13.0) | 10.0 (7.0–12.6) | 0.031 |

| Peak AVP gradient, mm Hg | 8 | 19.4 (15.0–24.9) | 19.8 (15.5–25.0) | 19.4 (14.4–24.3) | 0.088 |

| Effective orifice area, cm2 | 8 | 1.60 (1.38–1.90) | 1.69 (1.44–1.95) | 1.53 (1.30–1.85) | <0.001 |

| AR grade ≥moderate | 2 | 10 (0.9) | 4 (0.7) | 6 (1.2) | 0.421 |

| MR grade ≥moderate | 5 | 70 (6.4) | 24 (4.2) | 46 (8.9) | 0.001 |

| Periprocedural complications | |||||

| Coronary occlusion | 0 | 10 (0.9) | 5 (0.9) | 5 (1.0) | 0.866 |

| Permanent pacemaker implantation | 0 | 91 (8.3) | 37 (6.4) | 54 (10.4) | 0.017 |

| Acute kidney injury | 0 | 72 (6.6) | 25 (4.3) | 47 (9.1) | 0.002 |

AR indicates aortic regurgitation; AVP, aortic valve pressure; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction by modified Simpson or Teichholz methods; MR, mitral regurgitation; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography.

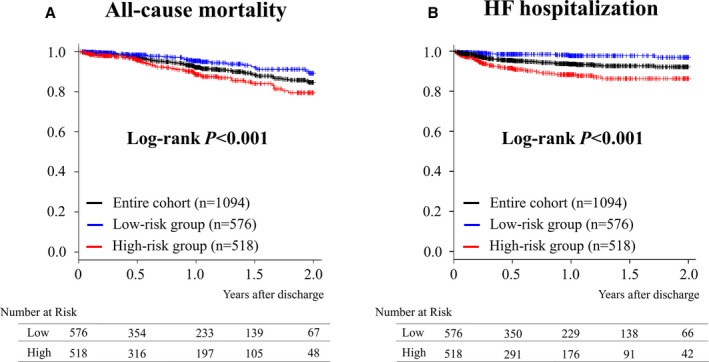

During the 2‐year follow‐up period, there were 75 mortality events and 59 hospitalization events attributable to HF. Figure 3 shows the Kaplan–Meier estimates of each end point following discharge. All‐cause mortality was 7.9% (95% CI, 5.8–9.9%) at 1 year and 15.4% (95 CI%, 11.6–19.0%) at 2 years, and hospitalization rates for HF were 6.6% (4.9–8.4%) at 1 year and 8.0% (95% CI, 5.8–10.2%) at 2 years. The survival CART analysis revealed that the discriminating BNP level at discharge to discern 2‐year mortality was 202 pg/mL, and, therefore, we divided the study population into 2 BNP groups based on this result. Patients in the low BNP group were defined as having a BNP ≤202 pg/mL at discharge and patients in the high BNP group were defined as having a BNP >202 pg/mL at discharge.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of each end point. Kaplan–Meier estimates of (A) all‐cause mortality after hospital discharge, and (B) hospitalization for heart failure (HF).

Regarding comparisons between the low and high BNP groups, there were a number of significant differences in patient characteristics and procedure‐related indices (Tables 1 and 2). The high BNP group had a higher proportion of factors associated with increased procedural risks, such as increased age, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, and higher Society of Thoracic Surgeons and logistic Euro scores, than the low BNP group. In addition, the Kaplan–Meier estimates revealed that 2‐year all‐cause mortality and hospitalization rates for HF were higher in the high BNP group than in the low BNP group with log‐rank P<0.001 in each end point (Figure 3), ie, all‐cause mortality was 11.4% (95% CI, 7.8–14.9%) versus 4.6% (2.3–6.8%) at 1 year and 20.5% (95% CI, 14.3–26.2%) versus 10.7% (95% CI, 6.1–15.2%) at 2 years, and hospitalization rates for HF were 11.6% (95% CI, 8.3–14.8%) versus 2.2% (95% CI, 0.7–3.6%) at 1 year and 13.6% (95% CI, 9.6–17.4%) versus 3.0% (95% CI, 0.8–5.1%) at 2 years in the high BNP and low BNP groups, respectively. Table 3 shows that high BNP had statistically significant impacts on outcomes with an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.28 (95% CI, 1.36–3.82; P=0.002) for all‐cause mortality, and an adjusted hazard ratio of 4.88 (95% CI, 2.32–10.27; P<0.001) for hospitalizations attributable to HF in a standard multivariable model with a statistically significant difference between men and women for all‐cause mortality (P=0.0495). In addition, the time‐dependent NRI and IDI analyses revealed that incorporation of BNP group information with other clinical variables significantly improved predictive accuracy for 2‐year all‐cause mortality, with a resultant time‐dependent NRI of 0.415 (95% CI, 0.006–0.724; P=0.047) and IDI of 0.027 (95% CI, 0.002–0.075; P=0.029). In contrast, those for hospitalization for HF revealed that the time‐dependent NRI was 0.824 (95% CI, 0.390–1.110; P=0.008) and IDI was 0.035 (95% CI, −0.008 to 0.089; P=0.089).

Table 3.

Impact of BNP Stratification on Outcomes

| End Point | Univariable | Multivariable | AIC‐Based Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| All‐cause mortality | 2.34 (1.45–3.78) | <0.001 | 2.28 (1.36–3.82) | 0.002 | 2.26 (1.39–3.70) | 0.001 |

| Men | 4.77 (2.04–11.12) | <0.001 | 4.71 (1.82–12.21) | 0.001 | 5.04 (2.08–12.21) | <0.001 |

| Women | 1.61 (0.89–2.93) | 0.117 | 1.82 (0.96–3.45) | 0.066 | 1.57 (0.85–2.91) | 0.150 |

| Interaction | 0.0495 | Interaction | 0.046 | |||

| Hospitalization for HF | 5.75 (2.91–11.36) | <0.001 | 4.88 (2.32–10.27) | <0.001 | 4.57 (2.26–9.22) | <0.001 |

| Men | 8.96 (2.65–30.35) | <0.001 | 7.91 (1.70–36.83) | 0.008 | 5.23 (1.45–18.90) | 0.012 |

| Women | 4.69 (2.06–10.68) | <0.001 | 3.68 (1.54–8.75) | 0.003 | 4.14 (1.78–9.64) | 0.001 |

| Interaction | 0.399 | Interaction | 0.726 | |||

In the multivariable model, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of high brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) as compared with that of low BNP was calculated by adjusting the following variables with a cross‐product term between BNP groups and sex for the assessment of sex difference with a P for interaction: Clinical Frailty Scale, Society of Thoracic Surgeon (STS) score, apical approach, left ventricular ejection fraction, effective orifice area (EOA), mean aortic valve pressure gradient (AVPG), moderate to severe aortic regurgitation, acute kidney injury after transcatheter aortic valve replacement, and institution as a stratum. The Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) model selected Clinical Frailty Scale as a covariate for all‐cause mortality, and selected STS score, EOA, and mean AVPG as covariates for hospitalization for heart failure (HF).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the impact of BNP levels at discharge on 2‐year all‐cause mortality and hospitalization for HF, while providing risk stratification cutoff values of BNP after TAVR via enrollment of the largest relevant study population to date (n=1094) from the multicenter prospective OCEAN‐TAVI registry. We demonstrated that the best risk stratification BNP level at discharge was 202 pg/mL, and that elevated BNP levels (ie, in the high BNP group) were significantly associated with an increase in 2‐year all‐cause mortality and hospitalization rates for HF. In addition, time‐dependent NRI and IDI analyses revealed that the incorporation of BNP group information with other clinical variables significantly improved predictive accuracy for 2‐year all‐cause mortality. Since no previous studies have evaluated the direct relationship between BNP at discharge and patient prognosis following TAVR, our study could provide physicians with new insights into this field.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 20, 21

Long‐Term Mortality After TAVR

Thus far, it is evident that BNP is a useful risk stratification marker in patients with HF, as well as in patients with severe AS.7, 8, 9, 10, 20, 21 However, potential relationships between BNP levels and patient prognoses following TAVR were evaluated primarily based on BNP on admission in previous studies, and it should be noted that few of these focused on long‐term prognosis.12, 13, 14 For example, Koskinas et al12 reported that the highest tertile group of BNP on admission was associated with higher 2‐year all‐cause mortality compared with the 2 lower tertile groups in their single‐center study that included 340 patients. In contrast, O'Neill et al22 suggested that BNP on admission was in fact not associated with 1‐year mortality, based on data from 933 patients enrolled in the PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve) trial. Therefore, we performed this study to evaluate the long‐term prognostic impact of BNP levels at discharge in patients who have undergone TAVR by enrolling the largest number of relevant study participants to date, using multicenter prospective OCEAN registry data. We revealed that elevated BNP levels at discharge were independently associated with higher 2‐year all‐cause mortality and that the incorporation of BNP group information with other clinical variables significantly improved predictive accuracy for determining 2‐year all‐cause mortality. Considering our results and the short half‐life of BNP, we speculated that BNP at discharge would be more favorable for risk stratification of long‐term prognosis than that on admission in patients who had undergone TAVR because the TAVR procedure releases the left ventricle from pressure overload immediately after the valve replacement.

Hospitalization for HF After TAVR

In the present study, elevated BNP was also independently associated with 2‐year hospitalization for HF following TAVR. Furthermore, the hazard ratio for hospitalization for HF was much higher than that of all‐cause mortality (4.88 versus 2.28). Although evidence has shown that BNP is useful in the diagnosis, management, and risk stratification of HF and that rehospitalization as a result of symptoms of AS, such as HF, is one of the most important outcomes to evaluate in TAVR cohorts, most previous studies regarding BNP in patients who underwent TAVR procedures did not focus on hospitalization for HF.5, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 23 As such, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to examine the association between BNP at discharge and hospitalization for HF following TAVR using a large cohort. Even though our results are intuitively understandable, this confirmation supported by clinical data may provide physicians with additional valuable information in this field.

Sex Difference

In this study, the proportion of male participants was relatively low (≈30%) compared with studies in Western countries.3, 4, 5, 24 Although several previous reports have reported higher BNP levels in women than in men among the general population,25, 26 there was no statistical difference in BNP levels between men and women at discharge in our cohort. This sex disparity should be taken into consideration when interpreting our data. Interestingly, the impact of BNP levels on all‐cause mortality among men in our study was statistically greater than that among women, with a P value for interaction of 0.0495. This is consistent with the findings of a previous report in patients with acute decompensated HF in which BNP at discharge predicted cardiovascular events in men but not women.27

Clinical Implication

Patients who undergo the TAVR procedure may present with multiple risk factors that can affect their clinical outcome. Therefore, it is helpful for physicians to have access to a simple risk stratification model to assist them with better managing their patients. BNP has been widely used for this purpose in many situations, such as in patients with HF.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Based on this viewpoint, we performed survival CART analysis and revealed that patients in the high BNP group, defined as patients with BNP >202 pg/mL at discharge, should be carefully monitored to help avoid the need for hospitalization for HF and/or decrease the potential for mortality.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the BNP values collected were measured at individual OCEAN‐TAVI registry institutions using different methods rather than at a single core laboratory. For example, it has been reported that ADOVIA Centaur from Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc has relatively poor comparability with other assays (Table 4).28 However, 5 of 6 assays employed the same reagent (Shionogi & Co, Ltd), suggesting high comparability between assays (Table 4). In addition, multivariable Cox regression was performed, including each institution as a stratum, to consider the differences among BNP assays. Second, the decision to hospitalize patients based on the theory that their HF was worsening is an individual judgment made by each attending physician without adherence to any prespecified criterion, especially because this study was a prospective observational registry. Third, the proportion of men was relatively low in the OCEAN‐TAVI registry as compared with studies in Western countries.3, 4, 5, 24 Last, a direct comparison of the impacts of BNP on admission and at discharge was beyond the scope of this study and should potentially be evaluated as a next and different scientific objective.

Table 4.

Summary of Correlations Among BNP Assays

| Patients (Hospital), No. | Company | Method | Reagent | Sample | r | Formula | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 417 (6) | Abbot | CLIA | Shionogi | 176 | 0.980 | 1.00X+1.08 | Shionogi (CLEIA) |

| 47 (2) | Siemens | CLIA | NA | NA | 0.9 | 0.74X−0.6 | NA |

| 219 (1) | Tosoh | ELISA | Shionogi | 193 | 0.995 | 0.967X−1.291 | Shionogi (RIA) |

| 94 (1) | Tosoh | CLEIA | Shionogi | 193 | 0.995 | 0.967X−1.291 | Shionogi (RIA) |

| 183 (2) | FUJIREBIO | CLEIA | Shionogi | 55 | 0.99 | 0.94X−3.41 | Shionogi (CLEIA) |

| 134 (2) | LSI | CLEIA | Shionogi | 81 | 0.988 | 1.05X+0.58 | Shionogi (CLEIA) |

Chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CLIA) measurement kits included ARCHITECT BNP assay (Abbot Laboratories Diagnostics Division) and ADOVIA Centaur BNP assay (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc). ELISA measurement kits included E‐test TOSOH II BNP (Tosoh Bioscience). Chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (CLEIA) measurement kits included AIA‐packCL BNP (Tosoh Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan), PATHFAST®BNP (LSI Medience Corporation), and Lumipulse Prestol II (FUJIREBIO Inc). BNP indicates B‐type natriuretic peptide; NA, not available; r, correlation; RIA, radioimmunoassay (Shionogi, Shionogi & Co, Ltd).

Conclusions

Elevation of BNP at discharge is associated with 2‐year all‐cause mortality and hospitalization for HF after TAVR.

Disclosures

Hayashida, Shirai, Tabata, Araki, Takagi, and Tada are clinical proctors for Edwards Lifesciences. Yamamoto, Watanabe, and Naganuma are clinical proctors for both Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. All other authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose in connection with the submitted article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the Japan Society of Clinical Research for their dedicated support.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006112 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006112.)28710182

References

- 1. Maganti K, Rigolin VH, Sarano ME, Bonow RO. Valvular heart disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:483–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP III, Guyton RA, O'Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM III, Thomas JD; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines . 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:e57–e185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Williams M, Dewey T, Kapadia S, Babaliaros V, Thourani VH, Corso P, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D, Pocock SJ; PARTNER Trial Investigators . Transcatheter versus surgical aortic‐valve replacement in high‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2187–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Brown DL, Block PC, Guyton RA, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Douglas PS, Petersen JL, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D, Pocock S; PARTNER Trial Investigators . Transcatheter aortic‐valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, Makkar RR, Svensson LG, Kodali SK, Thourani VH, Tuzcu EM, Miller DC, Herrmann HC, Doshi D, Cohen DJ, Pichard AD, Kapadia S, Dewey T, Babaliaros V, Szeto WY, Williams MR, Kereiakes D, Zajarias A, Greason KL, Whisenant BK, Hodson RW, Moses JW, Trento A, Brown DL, Fearon WF, Pibarot P, Hahn RT, Jaber WA, Anderson WN, Alu MC, Webb JG; PARTNER 2 Investigators . Transcatheter or surgical aortic‐valve replacement in intermediate‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1609–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daniels LB, Maisel AS. Natriuretic peptides. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2357–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anand IS, Fisher LD, Chiang YT, Latini R, Masson S, Maggioni AP, Glazer RD, Tognoni G, Cohn JN; Val‐HeFT Investigators . Changes in brain natriuretic peptide and norepinephrine over time and mortality and morbidity in the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val‐HeFT). Circulation. 2003;107:1278–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dickstein K, Larsen AI, Bonarjee V, Thoresen M, Aarsland T, Hall C. Plasma proatrial natriuretic factor is predictive of clinical status in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:679–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Doust JA, Pietrzak E, Dobson A, Glasziou P. How well does B‐type natriuretic peptide predict death and cardiac events in patients with heart failure: systematic review. BMJ. 2005;330:625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bergler‐Klein J, Klaar U, Heger M, Rosenhek R, Mundigler G, Gabriel H, Binder T, Pacher R, Maurer G, Baumgartner H. Natriuretic peptides predict symptom‐free survival and postoperative outcome in severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2004;109:2302–2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gotzmann M, Czauderna A, Aweimer A, Hehnen T, Bösche L, Lind A, Kloppe A, Mügge A, Ewers A. B‐type natriuretic peptide is a strong independent predictor of long‐term outcome after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Heart Valve Dis. 2014;23:537–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koskinas KC, O'Sullivan CJ, Heg D, Praz F, Stortecky S, Pilgrim T, Buellesfeld L, Jüni P, Windecker S, Wenaweser P. Effect of B‐type natriuretic peptides on long‐term outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1560–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kefer J, Beauloye C, Astarci P, Renkin J, Glineur D, Dekleermaeker A, Vanoverschelde JL. Usefulness of B‐type natriuretic peptide to predict outcome of patients treated by transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1782–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Sullivan CJ, Stortecky S, Heg D, Jüni P, Windecker S, Wenaweser P. Impact of B‐type natriuretic peptide on short‐term clinical outcomes following transcatheter aortic valve implantation. EuroIntervention. 2015;10:e1–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abramowitz Y, Chakravarty T, Jilaihawi H, Lee C, Cox J, Sharma RP, Mangat G, Cheng W, Makkar RR. Impact of preprocedural B‐type natriuretic peptide levels on the outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1904–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mair J. Biochemistry of B‐type natriuretic peptide—where are we now? Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46:1507–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hannan EL, Samadashvili Z, Jordan D, Sundt TM III, Stamato NJ, Lahey SJ, Gold JP, Wechsler A, Ashraf MH, Ruiz C, Wilson S, Smith CR. Thirty‐day readmissions after transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis in New York State. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:e002744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hara M, Sakata Y, Nakatani D, Suna S, Nishino M, Sato H, Kitamura T, Nanto S, Hamasaki T, Hori M, Komuro I; OACIS Investigators . Subclinical elevation of high‐sensitive troponin T levels at the convalescent stage is associated with increased 5‐year mortality after ST‐elevation myocardial infarction. J Cardiol. 2016;67:314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fonarow GC, Adams KF Jr, Abraham WT, Yancy CW, Boscardin WJ; ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee, Study Group, and Investigators . Risk stratification for in‐hospital mortality in acutely decompensated heart failure: classification and regression tree analysis. JAMA. 2005;293:572–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Parikh V, Kim C, Siegel RJ, Arsanjani R, Rader F. Natriuretic peptides for risk stratification of patients with valvular aortic stenosis. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clavel MA, Malouf J, Michelena HI, Suri RM, Jaffe AS, Mahoney DW, Enriquez‐Sarano M. B‐type natriuretic peptide clinical activation in aortic stenosis: impact on long‐term survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2016–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Neill BP, Guerrero M, Thourani VH, Kodali S, Heldman A, Williams M, Xu K, Pichard A, Mack M, Babaliaros V, Herrmann HC, Webb J, Douglas PS, Leon MB, O'Neill WW. Prognostic value of serial B‐type natriuretic peptide measurement in transcatheter aortic valve replacement (from the PARTNER Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:1265–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shapiro BP, Chen HH, Burnett JC Jr, Redfield MM. Use of plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration to aid in the diagnosis of heart failure. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shimura T, Yamamoto M, Kano S, Kagase A, Kodama A, Koyama Y, Tsuchikane E, Suzuki T, Otsuka T, Kohsaka S, Tada N, Yamanaka F, Naganuma T, Araki M, Shirai S, Watanabe Y, Hayashida K; on the behalf of OCEAN‐TAVR investigators . Impact of the Clinical Frailty Scale on outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Circulation. 2017;135:2013–2024. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Redfield MM, Rodeheffer RJ, Jacobsen SJ, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Burnett JC Jr. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration: impact of age and gender. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:976–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luchner A, Behrens G, Stritzke J, Markus M, Stark K, Peters A, Meisinger C, Leitzmann M, Hense HW, Schunkert H, Heid IM. Long‐term pattern of brain natriuretic peptide and N‐terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide and its determinants in the general population: contribution of age, gender, and cardiac and extra‐cardiac factors. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:859–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nakada Y, Kawakami R, Nakano T, Takitsume A, Nakagawa H, Ueda T, Nishida T, Onoue K, Soeda T, Okayama S, Takeda Y, Watanabe M, Kawata H, Okura H, Saito Y. Sex differences in clinical characteristics and long‐term outcome in acute decompensated heart failure patients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;310:H813–H820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Collin‐Chavagnac D, Dehoux M, Schellenberg F, Cauliez B, Maupas‐Schwalm F, Lefevre G; Société Française de Biologie Clinique Cardiac Markers Working Group . Head‐to‐head comparison of 10 natriuretic peptide assays. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015;53:1825–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]